Archive for the 'Directors: Mizoguchi Kenji' Category

Kurosawa’s early spring

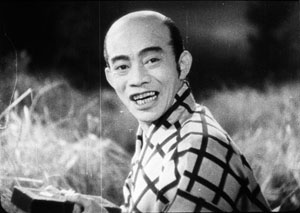

The Most Beautiful (1944).

For Donald Richie

DB here:

Cinephile communities aren’t free of peer pressure. Sometimes you must choose or be thought a waffler. In postwar France, the debate within the Cahiers du cinéma camp often came down to big dualities. Ford or Wyler? German Lang or American Lang? British Hitchcock or American Hitchcock? In the America of the 1960s and 1970s, we had our own forced choices, most notably Chaplin or Keaton?

This maneuver assumed that a simple pair of alternatives could profile your entire range of tastes. If you liked Chaplin, you probably favored sentiment, extroverted performance, and direction that was straightforward (“theatrical,” even crude). If you liked Keaton, you favored athleticism, the subordination of figure to landscape, cool detachment, and geometrically elegant compositions. One director risked bathos, the other coldness. The question wasn’t framed neutrally. My generation prided itself on having “discovered” the enigmatic Keaton, in the process demoting that self-congratulatory Tramp. Keaton never begged for our love.

Of course it was unfair. The forced duality ignored other important figures—Harold Lloyd most notably—and it asked for an unnatural rectitude of taste. Surely, a sensible soul would say, one can admire both, or all. But we weren’t sensible souls. Drawing up lists, defining in-groups and out-groups, expressing disdain for those who could not see: it was all a game cinephiles played, and it put personal taste squarely at the center of film conversation.

In the 1950s another big duality slipped into Paris-influenced film talk. Virtually nobody knew about Ozu, Shimizu, Gosho, Naruse, Shimazu, Yamanaka, et al., so two filmmakers had to stand in for the whole of Japanese cinema. Mizoguchi or Kurosawa?

A problematic auteur

For Cahiers the choice was clear. Mizoguchi was master of subtly shaping drama through the body’s relation to space, thanks to quiet depth compositions and modulations of the long take. In Japan, land of exquisite nuance, the dream of infinitely expressive mise-en-scene seemed to have come true.

There seemed to be nothing nuanced about Kurosawa, whose brash technique, overripe performances, and propulsive stories seemed disconcertingly “Western.” Sold, like Satyajit Ray, as a humanist from an exotic culture, he played into critics’ eternal admiration for significance. This director wanted to make profound statements about the bomb (I Live in Fear), the relativity of truth (Rashomon), the impersonality of modern society (Ikiru), and the complacency of power (High and Low, The Bad Sleep Well). Even his swordplay movies seemed moralizing, with the last line of Seven Samurai (“The victory belongs to these peasants. Not to us.”) summoning up a cheer for the little people. Kurosawa could thus be assigned to Sarris’s category of Strained Seriousness. “He’s the Japanese Huston,” said a friend at the time.

But there was no overlooking his cinematic gusto. He made “movie movies.” He flaunted deep-focus compositions, cunningly choppy editing, sinuous tracking shots (through forests, no less), dappled lighting, and abrupt addresses to the viewer, by a voice-over narrator or even a character in the story. He exploited long lenses and multiple-camera shooting at a period when such techniques were very rare, and he may have been the first director to use slow-motion for action scenes. Bergman, Fellini, and other international festival filmmakers of the 1950s didn’t display such delight in telling a story visually. If you liked this side of his work, you overlooked the weak philosophy. On the other hand, if you found the style too aggressive, it could seem mere calculation on the part of a man with something Important to say.

The case for the defense was made harder by the fact that he was a controversial figure at home as well. Japanese critics I met over the years expressed puzzlement about Western admiration for the director’s style. I was once on a panel in which an esteemed critic blamed Kurosawa for influencing Western directors like Leone and Peckinpah. His violence and showy slow-motion had helped turn modern cinema into a blunt spectacle. No wonder Lucas, Spielberg, Coppola, and Walter Hill have loved this macho filmmaker.

Today passions seem to have cooled, but I should confess that my own tastes remain rooted in my salad days (1960s-1970s). I could live happily on a desert island with only the films of Ozu and Mizoguchi. I’d argue forever that Japanese cinema of the 1920s through the 1960s is rivaled for sheer excellence only by the parallel output of the US and France. (For more on this matter, see my blog entry on Shimizu.) On Kurosawa, however, my feelings are mixed. I still find most of his official classics overbearing, and the last films seem to me flabby exercises. But there are remarkable moments in every movie. Overall, I’ve responded best to his swordplay adventures; Seven Samurai was the first film that showed me the power of the Asian action aesthetic. I think as well that his earliest work up through No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), along with the later High and Low and Red Beard, are extraordinary films. And, like Hitchcock and Welles, he is wonderfully teachable.

We don’t live on desert islands, and gradually we’re gaining easy access to the range of Japanese filmmaking of its great era. We can start to see beyond the fortified battlements set up by generations of critics. With so many points of entry into Japanese cinema, mighty opposites lose their starkness; polarities dissolve into the long tail. Nevertheless, personal tastes take you only so far, and objectively Kurosawa still looms large. Whatever your preferences, it’s important to study his place in film history and film art.

Gauging that place involves thinking outside some traditional conceptions of how films work. Like most ambitious Japanese directors, Kurosawa provides bursts of cinematic swagger. This six-shot passage from Rashomon revels in its own strangeness.

Here traditional over-the-shoulder shots submit to a brazen geometry. Out of an ABC film-school technique Kurosawa creates a cascade of visual rhymes and staccato swiveled glances. Yes, an ingenious critic could thematize this bravura passage. (“The symmetries put the central characters, each of whom asserts a different version of what happened, on the same visual and moral plane.”) Instead I’m inclined to think that the shots constitute a little thrust of “pure cinema,” a brusque cadenza that keeps our eyes, if not our hearts or minds, locked to the screen. From this angle, Kurosawa claims some attention as an inventor of, or at least tinkerer with, the disjunctive possibilities of film form.

His centenary arrives in 2010, and the occasion is celebrated by Criterion with a set of twenty-five DVDs. Most of these titles have already been available singly, and the discs lack all the bonus features we have come to admire from the company. Yet the crimson and jet-black box, the discreet rainbow array of slip cases, and the subtly varied design of the menus add up to a good object, like the latest iPod—something you want even if it means re-buying things you already have. There’s also a handsome picture book with notes by Stephen Prince on each film.

To viewers who need the assurance of cultural importance, this behemoth announces: You must know Kurosawa to be filmically literate. And that’s more or less true. Just as important, the inclusion of four rarities from his early years gives the collection a claim on every film enthusiast’s attention. One hopes that those titles will eventually appear separately, perhaps in an Eclipse edition. [See 15 May 2010 update at the end.] For now these copies of the wartime features are far better than the imports I’ve seen.

The Big Box makes it tempting to mount a career retrospective on this site, but that’s far beyond my capacity. Future blog entries may talk more of this complicated filmmaker, but for now I’ll confine my remarks to these early works. They offer plenty for us to enjoy.

Audacious propaganda

Although Kurosawa was only seven years younger than Ozu, he belongs to a distinctly different generation. Ozu directed his first film in 1927, at the ripe age of twenty-four. He grew up with the silent cinema and made masterful films in the early 1930s, during the long twilight of Japanese silent filmmaking. Kurosawa became an assistant director in the late 1930s. Although he evidently directed large stretches of Yamamoto Kajiro’s Horse (1941), he didn’t sign a feature as director until he was thirty-three. His closest contemporary, and a director whom some Japanese critics consider his superior, is Kinoshita Keisuke. Kinoshita was born in 1912 and his first feature, The Blossoming Port, was released in the same year as Kurosawa’s debut.

Kurosawa and Kinoshita began their careers making wartime propaganda. Their task was to display Japanese self-sacrifice and spiritual purity in stories of both the past and the present. In the Sanshiro Sugata films (1943, 1945), Kurosawa presents judo as an integral part of Japanese tradition and a path to enlightenment. Much of the external conflict is devoted to uniting martial arts (ju-jitsu, karate) under the rubric of the less aggressive but more powerful judo, and to showing how it can defeat American-style boxing. But the internal dimension is also important. Judo is a means of tempering character and accepting one’s proper place. Humble, unflagging devotion to one’s vocation becomes heroic.

The same quality can be found in The Most Beautiful (1944), a story of teenage girls working in a factory manufacturing lenses for binoculars and gunsights. Vignettes from the girls’ lives dramatize the need for cooperation and sacrifice, even as wartime demands for output threaten the girls’ health.

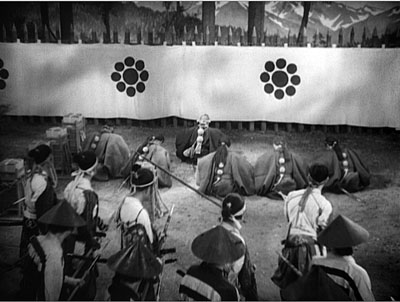

A more detached conception of the Japanese spirit underlies The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail (1945). This adaptation of a plot from Noh and Kabuki theatre shows officers escorting a general through enemy territory. Disguised as monks, the bodyguards are forced to bluff their way through a checkpoint. The situation is one of hieratic suspense, made more tonally complex by Kurosawa’s addition of the movie comedian Enoken. Enoken plays a dimwitted porter reacting to the charade played out by his betters. By dramatizing one of the most famous episodes in Japanese literature, Kurosawa was reasserting the tradition of devotion to duty and honor. The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail was released the same month that the atomic bomb fell on Hiroshima.

During earlier decades, Japanese cinema had created a complex tradition. In part, it conducted a sustained dialogue with Western cinema. Tokyo had access to a wide range of Hollywood movies, and directors studied American technique closely. Just as Ozu would not be Ozu without his early fondness for Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd, Mizoguchi learned a good deal from von Sternberg. Between 1938 and 1942, alongside German imports Tokyo theatres screened Fury, Only Angels Have Wings, The Sea Hawk, The Awful Truth, Angels with Dirty Faces, Boys Town, Young Tom Edison, Only Angels Have Wings, and many French titles. In 1942, with Hollywood films now banned, one could still see René Clair’s Le Million and À Nous la liberté—films that had been circulating in Japan since the early 1930s and could have served as models of flashy sound technique. It’s misleading to talk of Ozu as “purely Japanese” and Kurosawa as “Western”: All Japanese directors of the 1920s and 1930s were deeply acquainted with Western cinema, and American cinema in particular furnished a foundation for most local filmmaking.

Yet there are crucial differences. Japanese cinema welcomed extremes of stylistic experimentation that would have been rare in Western cinema. The 1920s swordplay films (chambara) pioneered rapid editing, handheld camerawork, and abstract pictorial design. (I supply some examples here.) Directors working in the contemporary-life mode (the gendai-geki) experimented similarly, often achieving remarkable visual effects and bold stylization. Mizoguchi and Ozu have become our emblems of this creative rigor and richness, but they are the peaks of what was a collective approach to filmic expression. Not every film was an experiment—indeed, most behave like Hollywood or European productions—but many ordinary movies, signed by unheralded directors, exhibit flashes of unpredictable imagination. This was the tradition of permanent innovation that directors of the Kurosawa-Kinoshita generation inherited.

As the war dragged on, however, Japanese studio productions lost much of their audacity. Production fell from over 400 films in 1939 to fewer than 100 in 1943. Censorship may have made filmmakers cautious about style as well as subject and theme. Most of the fifty-plus films I’ve been able to see from the period 1940-1945 are quite conservative aesthetically. Several of these seem to me quite good, but they rely on fairly standard Hollywood technique sprinkled with touches that had become markers of Japanese cinema (sustaining scenes in rather distant shots, using cuts rather than dissolves to shift scenes, and so on). Swordplay films become more severe and monumental. Even Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura (1941-42) and Ozu’s There Was a Father (1942), superb as they are, are more elevated in tone than the directors’ earlier works.

Against this backdrop, Kurosawa’s films stand out; they are the most extroverted works I know in this period. Their innovations remain vivid; Sanshiro Sugata, for one, with its hierarchy of competitors, its rivalry among schools, and its visceral technique, may have invented the modern martial arts film. But we should also realize that these early films build upon the traditions already firmly established in Japanese cinema.

Playing with the passing moment

Consider transitions. Kurosawa is famous for his elaborate links between sequences, from the hard-edged wipes to swift imagistic associations. But we should recall that transitional passages offer moments of flashy style in American and European cinema of the 1920s and 1930s, and indeed right up to this day. (For examples, go here and here.) In the same year as Sanshiro, Kinoshita gave us this moment in Blossoming Port. A con artist is trying to bilk money from a town. He bows, leaving an empty frame.

Without a discernible cut, heads pop into the empty frame, rocking to and fro.

Another cut reveals that the people we see are in a boat tossing on the waves, and the conman’s partner is enjoying an outing with the locals. Kurosawa’s scene-changes—sites of what Stephen Prince has called “formal excess”—can be seen as prolonged, imaginative reworkings of this tricky-transition convention.

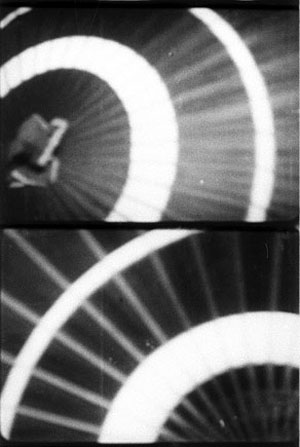

Japanese filmmakers were more willing to play with the expressive and “decorative” side of filmmaking than most of their Western peers. Directors created not only flashy transitions but moments of stylistic playfulness within scenes. Sometimes this just adds to the overall tone of comedy, as in this pretty passage in Heiroku’s Dream Story, another 1943 release. The hero, played by Enoken, is squatting and talking to a charming girl (Takamine Hideko). She twirls her parasol between them, and we get a straight-on cut that creates a moment of abstraction as the parasol glides across the frame in contrary directions. (The vertical pair of frames shows the cut.)

This decorative symmetry would be rare in Hollywood outside a Busby Berkeley number, but it enlivens the characters’ exchange in a way similar to the more dramatic Rashomon sequence. To borrow a phrase that Kepler applied to nature’s way with snowflakes, a filmmaker may seek to ornament a scene by “playing with the passing moment.”

Likewise, in The Blossoming Port, as an older woman recalls a romance of her youth, the natural sound fades out and the back-projection behind the carriage shifts from the seaside to urban imagery of the period she’s remembering.

The frank artifice of this shot shows that Japanese filmmakers were eager to let us enjoy the forms with which they were working.

A similar explicitness about style can be seen in one of Kurosawa’s signature devices, the axial cut. This technique shifts the framings toward or away from the subject along the lens axis. If the shots are short enough, we sense a bump at the abrupt change of shot scale.

Kurosawa often uses this cutting to stress a momentary gesture or to prolong a moment of stasis. But it can structure a simple dialogue scene as well. In Sanshiro Sugata, the hero’s first conversation with Sayo takes place as they descend a stair toward a gateway. Kurosawa uses axial cuts to keep up with them as they move away from us down the steps. Illustrated with stills, this technique looks like a forward camera movement, but in fact these images come from separate shots.

The crux of the scene is Sayo’s revelation that the man Sanshiro must fight is her father, and instead of big close-ups to underscore his reaction, Kurosawa simply lets his hero halt while Sayo continues down the steps. The steady pattern of cut-ins to the characters’ backs makes Sayo’s sudden turn to the camera more vivid, and Sanshiro’s reaction is underplayed by not giving us direct access to his face.

An earlier entry traces theaxial cut back to silent film, when its jolting possibilities were exploited in Soviet montage cinema. Japanese directors also used the device often. Yamanaka Sadao, one of the most-praised directors of the 1930s, used axial cuts prominently in an early dialogue scene of Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937). The cuts are accentuated by low-height compositions that maintain the steep perspective of the street.

The technique gains more punch in Japanese swordplay films. Here is a percussive instance from Faithful Servant Naosuke (1939), four short shots yanking us inward in a way that Kurosawa would make his own.

Tom Paulus reminds me that Capra films sometimes make use of this technique, as in this string of concentration cuts from Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939).

Interestingly, Mr. Smith ran on several Tokyo screens in October 1941; it may have been the last Hollywood feature to receive theatrical distribution before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

To say that Kurosawa adapts traditional devices doesn’t take away from his accomplishment. No artist starts from zero, and in commercial cinema, filmmakers commonly revise schemas already in circulation. So Kurosawa puts his own spin on the axial cut, not only by using it frequently, but also by varying it in the course of a film. Sanshiro Sugata 2 makes the axial shot-change a sort of internal norm, but then varies it: inward or outward, cuts or dissolves, how great a variation of scale? When Sanshiro leaves Sayo, the three phases of his departure are marked by simple repetition: each time he halts and looks back, she responds by bowing.

Like the Rashomon sequence, this shows Kurosawa’s fondness for permuting simple patterns. But there’s an expressive payoff too. The framings that make Sayo dwindle to a speck give the axial cuts the forlorn, lingering quality we usually associate with dissolves. In addition, for viewers who know Sanshiro 1, the scene calls to mind the staircase passage we’ve already seen. Their first extended encounter is paralleled by their last one.

Axial cuts are easier to handle when the subject is unmoving, or moving straight toward or away from the camera. What about other vectors of motion? In The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, as the general’s bodyguards file out of the compound, they pass a line of soldiers in the foreground. Kurosawa combines concentration cuts with lateral cutting, so our men stalk leftward through the frame once, then again, then again, each time both closer to us and further along the row of soldiers.

Kurosawa revises other traditional techniques. You can find moments of extended stasis in swordplay films of earlier decades, and the technique surely owes something to the prolonged mie poses in Kabuki. But Kurosawa’s early films turn long pauses into living freeze-frames. Instead of using an optical effect, he simply asks his actors not to move! One combat in Sanshiro shows the audience caught in absolute stillness, staring at the result of Sanshiro’s throw. In Sanshiro 2, our hero and the boxer stand like statues in the prizefight ring until the American collapses. And in The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, the groups gathered at the checkpoint are absolutely unmoving for nearly fifty seconds as Benkei leads them in prayer.

This shot’s tactful, reverential composition echoes a fairly standard image for showing loyal retainers; here’s an example from a 1910s version of Chushingura.

In sum, I think that for his “manly movies” Kurosawa sifted through the Japanese film tradition and pulled out the most vigorous techniques he could find, all the while recognizing that rapid pacing needs the foil of extreme immobility. He compiled a digest of many arresting visual schemas available to him, and then pushed them in fresh directions. He realized as well that he could apply this sharp-edged style to genres dealing with modern life.

A most stubborn young woman

Although we think of Kurosawa as a “masculine” director, two of his finest films center on women. The Most Beautiful and No Regrets for Our Youth can be thought of as propaganda, but this label shouldn’t put us off. Propaganda works partly because it taps deep-seated emotions, and I’d argue that the formulaic nature of a “social command” can allow filmmakers a chance at emotional and formal richness. Because the message can be taken for granted or read off the surface, an ambitious director can go to town—nuancing the presentation, complicating its implications, taking the clichéd message as an occasion for pushing formal experiment. (Which is one aspect of what the Soviet montage filmmakers did.)

The Most Beautiful, probably the best movie ever made about child labor, starts off as a doctrinaire effort. Before even the Toho logo fades in, a title declares: “Attack and Destroy the Enemy.” The first fifteen minutes are filled with pledges to help the war effort, work to meet an emergency quota, obey orders, display filial devotion, build noble character, and think constantly of how making flawless lenses saves soldiers’ lives. The rest of the movie focuses on the pain of doing all this. This story of patriotic affirmation is steeped in tears.

The film’s structure looks forward to the ensemble-based, threaded plotlines employed in Red Beard and Dodes’kaden. We follow various stories, if only briefly, as the teenage girls push themselves beyond the limits proposed by their overseers. The factory directors and the dormitory mother are barely characterized, so that the focus falls on the girls who have left their homes to serve their country. One looks out the window when a train passes; another walks sobbing across a garden made of heaps of earth from each girl’s native village. When one girl falls from a roof, she promises to keep working on crutches. Another hides the fact that she has a fever. In this movie, workers cry out “Mother!” in their sleep.

Sanshiro Sugata pulses with the exuberance of a young man’s body itching for constant movement. Kurosawa’s second film applies his muscular techniques to a static situation: Girls bent over machines. True, there are interludes of a marching and volleyball, the latter calling forth a standardized stretch of montage, but the director’s central task is to dynamize conversations. He finds a remarkable array of options. We get good old axial cutting, but there are also jump cuts (as if the action were too urgent to wait for dissolves), resourcefully simple staging (see this entry), abrupt close-ups, quick flashbacks, and judicious long takes jammed with actors.

Off on the right stand two tall girls frowning and looking down; their quarrel will burst out in a later scene.

The virtuosity here is quieter than in Sanshiro, largely because of the insistent threat of shame. A Hollywood film of the period might play up the triumphant achievement of the quota, but here this goal fades away. Instead, the plot is driven by a nearly desperate fear of failure. The men in charge offer bluff reassurance, but in a reprise of high-school nerves, the girls fret constantly about doing less than their mates. Their anxiety is translated into gesture-based performance—not through Western hysteria but through gestures of lowering the eyes, bowing the head, turning one’s back. The Most Beautiful has some of the greatest back-to-the-camera scenes in film history, and Kurosawa doesn’t hesitate to insert some of these moments in wide shots, creating a delicate emotional counterpoint. At one moment the girls are distracted by a passing airplane but their leader is sunk in thought; at another moment the girls challenge the leader while her accuser can’t face her.

The girls’ stories are woven around Watanabe, the section leader. Somewhat older than the others and nowhere near as spontaneous or joyous, she’s the emblem of unremitting self-sacrifice. If Sanshiro matures in the course of his films, learning the humbling responsibilities of becoming a supreme fighter, she comes to her more mundane task already grown up. Noël Burch has pointed out that Kurosawa’s protagonists are notably stubborn, and Watanabe offers a prime instance.

At the climax she has to search through thousands of lenses for a flawed one that she accidentally let through. Kurosawa forces us to watch her, exhausted from hours of work, hunched over her microscope and keeping awake by singing a patriotic song. One shot holds on her groggy efforts for over ninety seconds, so we register both the enormity of her task and her obstinate refusal to quit. This shot will be paralleled by the film’s final one, which lasts almost exactly as long, when she returns to her workbench. Now her concentration is broken, again and again, by quiet weeping. Kurosawa claims that when he made the film he knew Japan would lose the war.

The ending of The Most Beautiful calls to mind a moment in another Kinoshita film, again one released in the same year as Kurosawa’s. Army (1944) ends on a similarly ambivalent note, with a frantic mother pushing through a crowd cheering recruits marching off to war. Through cries of “Banzai!” she stumbles along to get a last glimpse of him, but soon her trembling figure is lost in the excitement. It isn’t exactly an exalted note on which to close a patriotic film.

A mother is central to Watanabe’s sacrifice in The Most Beautiful as well, and her plight reminds me of historian John Dower’s telling me that Japanese soldiers may have charged into battle shouting the name of the emperor, but many died murmuring, “Mother.”

Like other filmmakers, Kurosawa had to execute an about-face when the Americans came to occupy Japan. Along with Mizoguchi, Kinoshita, and most others, he began to make films that condemned the “feudal” forces that had led Japan to war and affirmed the need for liberalizing the society, not least with respect to women’s roles. Kurosawa’s contribution was No Regrets for Our Youth (1946), a survey of the 1930s and 1940s through the experience of a daughter of the middle class. At first she’s oblivious to the authoritarian threat and then, awakened to her social mission, she plunges into what we would now call the politics of everyday life. With the same verve that Kurosawa dramatized sacrifice for the motherland, he quickens a liberal fable of emerging political consciousness. Again, he finds ways of making propaganda deeply moving, while leaving his unique stamp on the project.

I hope to write about No Regrets and other Kurosawa titles in the future. But one implication should already be clear. Kurosawa remains on our agenda through his commitment to a mode of storytelling that pursues vigor without lapsing into the diffuse busyness of today’s spectacles. He stretches our senses through staccato action, yet he drills into other moments so implacably that we are forced to see deeper. He lifts certain Japanese and imported traditions to a new pitch, in the process often creating something indelible and enduring.

The point of departure for all things Kurosawa is Donald Richie’s Films of Akira Kurosawa, first published in 1965 and updated since. It was a trailblazing auteur study, written from deep knowledge of the films and many encounters with the director. Another indispensible source is Kurosawa’s Something Like an Autobiography (Knopf, 1982). Although it stops after the success of Rashomon, the book offers fascinating information about Kurosawa’s early life and first films. (“The Most Beautiful is not a major picture, but it is the one dearest to me.”) Information on the later films is collected in Bert Cardullo, Akira Kurosawa: Interviews (University Press of Mississippi, 2008). A biographical overview, with details on each film’s production, is provided in Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf (Faber, 2001).

For background on Japan’s wartime cinema, the central work is Peter B. High’s The Imperial Screen (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003). See also John Dower’s magnificent surveys of the war and the postwar period, War without Mercy (Pantheon, 1987) and Embracing Defeat (Norton, 2000).

Noël Burch argues that Kurosawa is best understood as working within a tradition of indigenous Japanese art; his pioneering To the Distant Observer (University of California Press, 1979) is available online here. Linking formal preoccupations to changing subjects and themes, Stephen Prince’s The Warrior’s Camera (Princeton University Press, 1999) argues that Kurosawa was forging heroic figures appropriate to developments in Japanese society. In Kurosawa: Film Studies and Japanese Cinema (Duke University Press, 2000), Mitsuhiro Yoshimoto puts the films in political contexts, while also considering how Kurosawa has been understood within the Western academy.

Critics have long recognized that Kurosawa’s formal inventiveness came with an impulse toward large statement. Brad Darrach reconciled the two tendencies in an overheated specimen of Timespeak:

Not since Sergei Eisenstein has a moviemaker set loose such a bedlam of elemental energies. He works with three cameras at once, makes telling use of telescopic lenses that drill deep into a scene, suck up all the action in sight and then spew it violently into the viewer’s face. But Kurosawa is far more than a master of movement. He is an ironist who knows how to pity. He is a moralist with a sense of humor. He is a realist who curses the darkness—and then lights a blowtorch.

This comes from “A Religion of Film,” a remarkable primer on the art cinema in its American spring. It was published in Time of 20 September 1963 and is available here. The same antinomy of stylist vs. moralist persists, with less complimentary results, in Tony Rayns’ obituary in Sight and Sound (October 1998), p. 3 and in Dave Kehr’s recent review of the Criterion boxed set.

I wrote about Kurosawa’s work in our textbook Film History: An Introduction (third edition, McGraw-Hill, 2009), pp. 234-235 and 388-390. My larger arguments about classic Japanese film can be found in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (online here) and in two articles in Poetics of Cinema (Routledge, 2008), “A Cinema of Flourishes: Decorative Style in 1920s and 1930s Japanese Film” and “Visual Style in Japanese Cinema, 1925-1945,” which analyzes some of the films I’ve considered here. I talk a little more about editing in Seven Samurai in this entry. In another I discuss how Kurosawa’s “humanism” fits into one 1950s ideological framework.

Yamanaka’s Humanity and Paper Balloons is available on DVD in the Eureka! series. For a cinematic homage to early Kurosawa, see Johnnie To’s Throw Down.

Thanks to Komatsu Hiroshi for supplying the date of Faithful Servant Naosuke. And as a PS, thanks to Luo Jin for pointing out a “slip of the finger”: the original post had Kurosawa older than Ozu!

PPS: 9 December: The Criterion site has just posted a reminiscence of Kurosawa by Donald Richie.

PPPS: 15 May 2010: Criterion has just announced that the four films discussed in this entry will be released as a separate collection on the Eclipse label.

Japan journey, part 2

DB here:

A seesaw trip in my last few days in Japan, with notes on watching some rare movies, visiting some superheroes, and watching some children cut down swaggering samurai.

Kansai wanderer

On Friday I traveled to Nagoya University with Yamanouchi Etsuko. She was my translator for a talk on Japanese film for my student, now professor, Fujiki Hideaki (above). Hideaki oversaw the translation of Film Art into Japanese and is the author of a new book on the growth of movie culture in Japan during the first decades of the century.

The talk seemed to go well, though my customary rapid-fire yammer sometimes left the fluent Etsuko breathless. Hideaki’s students and colleagues kept me on my toes with sharp questions. Then we all went out to a sumptuous dinner, where I had a chance to talk to many Nagoyans, including senior Japan expert Peter High, author of The Imperial Screen. Peter is now about to retire, as you can perhaps tell from his expression.

The talk seemed to go well, though my customary rapid-fire yammer sometimes left the fluent Etsuko breathless. Hideaki’s students and colleagues kept me on my toes with sharp questions. Then we all went out to a sumptuous dinner, where I had a chance to talk to many Nagoyans, including senior Japan expert Peter High, author of The Imperial Screen. Peter is now about to retire, as you can perhaps tell from his expression.

Because I lectured on what I call the “game of vision” in Japanese films, we had fun at dinner with composing shots that mimicked the peekaboo framings. Even relaxing, film wonks never turn off the movies running in our heads.

Next day I took a fairly impulsive trip to Kyoto. I tried to visit Mizoguchi’s grave, but had no luck finding it. After visiting it ten years ago, I shouldn’t have trusted my memory. Instead, I found Toei’s movie theme park, which provided me three hours of diversion.

Shochiku studios failed with its own theme park (go here for my reminiscence of it), partly because it had only Ozu and Tora-san as main attractions. But Toei has a bevy of swordplay heroes and….Power Rangers. An entire wing of the facility is dedicated to superheroes, life-size and some much larger.

I had no idea who these hardfaced bipeds were, but they sure looked pretty, with their nice snowmobiles and vaguely obscene gestures.

Elsewhere in the Toei park are streets evoking old Edo and Kyoto, as well as a kabuki theatre.

Mechanical ninja crawl around overhead, and samurai stroll the alleyways. You can watch a director pretending to shoot a TV show of swordplay in a studio set.

The most enjoyable moments came with a display of swordfight stunts carried out by three good-humored young samurai. They summoned from the audience a tiny boy, a somewhat older boy, and a tall little girl, and they gave them some elementary fighting skills. These skills consisted of stomping forward, crouching, and swinging the sword while letting out a blood-freezing shriek. The teachers made it look easy.

Then each kid was planted in front of the crowd and a swordsman rushed forward, with howling abandon. Miraculously, the kids’ fairly minimal defense tactics always defeated the men, who died in agony.

When one winner got obeisance from his enemies, he acted like the constantly scratching Mifune in Seven Samurai.

A new old Mizoguchi

Back to Tokyo and a round of shopping, eating, and moviegoing. I was staying with Komatsu Hiroshi, a friend of almost thirty years whom I first met at a conference on Dreyer in Verona. Hiroshi is a monumental figure in silent-cinema circles, and I’m planning a later blog entry profiling him.

With Hiroshi I saw two silent Makino Masahiro films at the national Film Center. For more on this series, see an earlier entry. Chronicle of 3 Generations (Gakkusei san daki, 1930) consisted of two installments of a short-comedy series produced by Makino. In the first, a modern girl throws over her boyfriend because he’s a bad baseball player. The second was reminiscent of Ozu’s Days of Youth in showing a college student trying to hide his slacker ways from his visiting father.

The second film, also part of a series, was directed by Makino. Street of Ronin (Roningai, 1929) was a bustling tale of a neighborhood of ne’er do wells. The benshi commentator must have been busy; there are over 260 intertitles in a film of about 72 minutes. I can’t tell you what happened in the plot, but the movie shows yet again that by the end of the 1920s Hollywood continuity style was in full vigor here. Makino uses a remarkable number of different setups in each scene.

At Hiroshi’s house he screened many rare items from his collection, mostly silent European, American, and Japanese films. One of the most striking Japanese titles was Magic in the Dark (Kurayami no Tejina, 1927), an experimental short with some of the stylization one finds in Kinugasa Teisuke’s Page of Madness (1926). The rain-drenched night scenes are like something out of Murnau.

The plot is didactic and uplifting, showing how a boy tempted by money pursues a righteous path. Magic in the Dark was directed by Suzuki Shigeoshi, whose most famous film is What Made Her Do It? (1930). That famous but currently incomplete feature, along with Magic in the Dark, will be released on the Kinokinuya DVD series that Hiroshi directs. Alas, no English subtitles. (See the PS below.)

The killer item was a newly discovered Mizoguchi film, one that doesn’t appear on official filmographies! Miss Okichi (Ojo Okichi, 1935) was residing in the Shochiku vaults, and a copy, in beautiful condition, was recently screened on Japanese television. Mizo codirected it with Takashima Tatsunosuke, a director whose work I don’t know, for Dai Ichi Eiga, the production company he formed with Nagata Masaichi. Dai Ichi Eiga, which later became Daiei, financed Mizo’s masterpieces Naniwa Elegy (1936) and Sisters of Gion (1936).

A bit like The Downfall of Osen (Orizuru Osen, 1935), this film centers on a woman who’s a cat’s paw for a gang involved in shady dealings. Okichi, played by Yamada Isuzu (whose bosom I nestle against in my earlier entry), is pulling scams for the sake of her lover. But she falls out with the gang and takes pity on one of the young men whom she victimizes.

I can’t comment on the film after only one viewing, and the fact that Mizoguchi is credited after Takashima suggests that he may have had little input. Still, it’s another tale of a woman who sacrifices herself for more or less unworthy men. Miss Okichi also has some typically Mizoguchian scenes that dwell on chiaroscuro melancholy. Much of the film takes place at night, and this strategy reinforces the somber atmosphere. There are some remarkably opaque long shots and one moment that includes Okichi turning toward the camera in a sort of plaintive challenge.

Given my admiration for Mizo, this capped a terrific ten days in Japan. Now on to Hong Kong, where I’ll blog at intervals on what happens at the Hong Kong Filmart market, the Asian Film Awards on Monday night, and the HK International Film Festival. I’ll be there, like Bernstein in Citizen Kane, before the beginning and after the end.

PS 24 July 2008: The Kinokuniya DVD of What Made Her Do It? has come out, and Joanne Bernardi reports that at least one version does have English subtitles…by her! Magic in the Dark is included on that disc. And despite information to the contrary, the DVD Joanne has is not Region 2 but all-region. Oddly, online listings of the DVD make no mention of these facts. Joanne does not yet know whether the subtitled all-region disc is the same as the one offered on amazon.jp and the Kinokuniya site, but it seems likely. More information as I get it, from Joanne or others.

Sleeves

DB here:

Earlier this month, when I was giving a lecture on Mizoguchi Kenji at our university museum, I showed two images from A Woman of Rumor (Uwasa no onna, 1954). It’s a little-known film of his, and it’s probably not up to his finest, but seeing the stills again on the big screen made me want to write about one scene. That scene displays aspects of Mizoguchi’s artistry that I touch on in one chapter of Figures Traced in Light and in the website supplement here.

This blog entry constitutes, I suppose, another supplement. After all, I couldn’t include in the book all the moments in Mizoguchi’s work that I find fascinating. But since comparison is a good way to get under a movie’s skin, my examination of a parallel scene from another movie may have more general interest. Even though Woman of Rumor doesn’t seem to be available on video, maybe looking at this pair of examples would inspire some readers to take an interest in one of the two or three greatest filmmakers who ever lived.

In the court of Regina

William Wyler and John Barrymore.

What a year 1941 was in the American cinema! We remember it for Citizen Kane but it also brought us How Green Was My Valley (a better film than Kane, I think), and items like Sergeant York (the biggest box-office hit), Dumbo, The Philadelphia Story, Suspicion, Ball of Fire, High Sierra, The Lady Eve, Meet John Doe, The Maltese Falcon, They Died with Their Boots On, and one of the most daring movies ever made in America, The Little Foxes.

An adaptation of Lillian Hellman’s play, The Little Foxes offers a study in unbridled capitalism. It shows how economic interests pit the South against the North and white against black. Psychologically, it analyzes a household gripped by the ruthless domination of the matriarch Regina (Bette Davis), the wiliest member of a family of grasping entrepreneurs. Regina has all but flattened her husband and is trying to make her daughter Alexandra oblivious to the family’s corruption.

The Little Foxes was also bold in its style—in its own way, as venturesome as Citizen Kane. It hasn’t been fully appreciated because Wyler is still thought of as a rather middlebrow talent, an overcautious director who toned down the flamboyance of Gregg Toland’s deep-space and deep-focus compositions.

Some day I hope to blog in defense of Wyler, middlebrow movies, and Midcult art in general. That would involve a detailed analysis of Little Foxes. (1) For now let’s just say that Wyler’s direction of the film won the admiration of no less than André Bazin. Bazin taught us to appreciate Wyler’s work, though with some prompting from Wyler and Toland (as I suggest here). Wyler was also appreciated by Mizoguchi, who, apparently grudgingly, told his screenwriter Yoda that he admired Wyler’s use of the “vertical frame.” (2) Later I’ll suggest one way of understanding that phrase. Mizoguchi met Wyler at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, when Ugetsu Monogatari was up against Wyler’s Roman Holiday for the Silver Lion.

One scene not discussed by Bazin or Mizoguchi, as far as I’m aware, has always gripped me. Regina’s brother Oscar has a wife, Birdie, who has turned into a passive alcoholic. Birdie has learned of plans to marry Xan off to Leo, her shallow son. Her will has been broken by Regina and Oscar, but she summons up the courage to blurt out to Xan that she mustn’t marry Leo, no matter how strongly the family insists. Xan, who has no inkling of how her family twists people to suit their ends, protests that no such thing could happen. But Oscar overhears Birdie warning Xan off.

Birdie and Oscar are about to leave at the end of the evening. Wyler begins with a standard two-shot, very slightly off-center. But as Birdie frantically warns Xan, Oscar’s sleeve and pant leg appear in the lower left of the frame, with the swagged curtain at the doorway hiding his face.

For us, this creates suspense. Only after Birdie has babbled out her warning do the two women notice he’s there. Xan, not knowing how Oscar abuses Birdie, heads off to bed.

As she climbs the staircase (very important in the film and the original play, this staircase) and heads off to her bedroom, Wyler’s camera arcs to reveal Oscar. Wyler now cuts to show, more or less from Birdie’s point of view, Xan going into her room.

Birdie watches anxiously, then turns to face Oscar, with a look of resigned apprehension.

Again suspense: Oscar won’t punish Birdie with Xan watching, but the girl’s departure puts Birdie in jeopardy. In addition, Wyler’s shot of her reaction anticipates the wrath she’ll face. (Patricia Collinge’s fluent performance is equal to the dynamics of Wyler’s visuals.) These cuts anchor our empathy; Wyler has been saving the close-up of Birdie for this moment.

We return to the master framing as Birdie heads toward Oscar, passing into a patch of shadow. As she does so, he raises his hand abruptly.

Wyler cuts to a two-shot. Oscar slaps Birdie so hard she seems to bounce against the left frame edge. She cries out and then tries to stifle her voice—a psychologically apt gesture for this woman who muffles her sorrows throughout the film.

Again, Wyler daringly sets a key action off-center. The brutal discontinuity of the cut, which crosses the axis of action and sharply changes shot scale, accentuates Oscar’s violence. It’s also rather elliptical; run the cut slowly, and you never see his hand strike her.

Xan hurries out of her room and comes to the banister, her face on the upper right balancing the placement of Birdie’s in the prior shot. In the next shot, we see, over her shoulder, Oscar stride out. Birdie follows meekly, assuring Xan that nothing’s wrong. The coda of the scene will emphasize Xan’s puzzled anxiety, a phase in her process of coming to understand the domineering fury that rules her family.

Low- and high-angle shots like this last pair recur throughout The Little Foxes, and I suspect that these are the sorts of thing Mizoguchi was invoking in mentioning Wyler’s “vertical” space. Wyler’s steep angles activate upper areas of the frame that many American directors hadn’t explored.

The act of overhearing a revealing conversation is a standard dramatic convention, but Wyler has refreshed and nuanced it. We know how it would be normally handled. We’d see either a shot showing Oscar stepping fully into the background, or a series of cuts showing first Birdie and Xan and then Oscar listening and watching. Wyler revises the standard schema, taking it for granted that we can pick up on a subtler cue than usual: just a bit of Oscar’s body intrudes.

As a result we have to be more alert. The information isn’t centered, but rather tucked into the lower left. And this option conceals Oscar’s face. Not that we’re doubting he’s angry, but delaying showing his anger builds up greater tension. Wyler, unlike today’s directors, knows when to build up to revealing things that we anticipate, making the final outburst more forceful when it comes. Further, the rest of the scene continues to deny us a clear view of Oscar’s anger, all of which gets squeezed into his gesture of slapping Birdie. It’s Birdie’s reaction that Wyler stresses, and Oscar’s contempt for her is conveyed simply by his bearing, his gesture, and his manner of stalking out of the foyer.

It’s not too much to talk about rigor here. The schemas dominating today’s filmmaking, the stylistic paradigm I call intensified continuity, would demand tight close-ups of everybody from the start. But providing them would make it harder for Wyler to raise the emotion when the startling slap comes. Maybe a contemporary director would render this spike in slo-mo, or with a wobbly handheld camera, but that tends to seem overbearing and pumped-up—as a lot of current stylistic pyrotechnics do. In any case, I’m betting that no American director today would use Oscar’s sleeve in the quietly ominous way Wyler does.

Mizoguchi’s game of vision

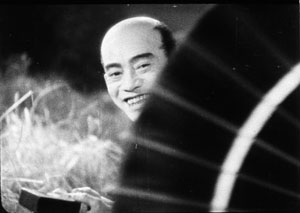

Mizoguchi Kenji, in glasses, during the making of Ugetsu.

Mizoguchi is renowned for his long takes, which are often sustained in distant views featuring considerable camera movement. In the Mizo chapter in Figures Traced in Light, I suggest that these stylistic choices spring from his effort to engage the viewer mesmerically—as he put it, “to work the viewer’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.” He asks us to downshift our attention to the finest details of the action, which he then modulates for expressive effect. I draw examples from various films across his career to show how he creates drama out of remarkably slight differences in character position, lighting, and other factors.

But what happens when he foreswears virtuoso camera movements and single-take scenes and breaks the drama up into several shots? Today, many ambitious directors seem to take pride in stretching out their takes, so cinephiles are sometimes inclined to see a cut as a loss of nerve and a concession to the audience. But I try to show in Figures that Mizoguchi sustains his concern for nuance when he creates an edited sequence. The modulation of fleeting details is to be found in his closer shots too.

In A Woman of Rumor, Hatsuko runs a teahouse that funnels customers to the geisha establishment behind it. She has tried to protect her daughter Yukiko from the shame of her profession. Hatsuko has also been cultivating a young doctor she hopes to marry, giving him money to set up a clinic. Now the doctor, Matoba, has become attracted to Yukiko. The scene I’m examining takes place during the performance of a noh drama. Hatsuko leaves the auditorium and finds Yukiko talking with Dr. Matoba.

As she passes around a screen, she hears Yukiko saying she wants to learn piano in Tokyo. Hatsuko looks left, and Mizoguchi cuts to an approximation of her optical point of view on the couple in the lounge.

So far, so conventional. Mizoguchi seems to follow the intercutting option for treating a scene of overheard conversation. But he goes further. Having laid out the action, Mizoguchi starts the lesson in just-noticeable-details . . . with a sleeve. He cuts to a reverse shot putting Matoba and Yukiko in the foreground. Hatsuko is still back there, though. We can see her kimono sleeve on the left, poking out from behind the screen.

A sharp-eyed viewer might also spot Hatsuko’s shadow on a wall, in the center of the shot, over Matoba’s shoulder. This blow-up shows both the sleeve and her silhouette.

Here, friends, is one reason we want to watch films in 35mm, and projected really big.

It’s now that Yukiko says that she may leave her mother, and Matoba replies, “Maybe I’ll go too.” This is devastating to Hatsuko. The two people whom she loves most seem to care nothing for her. Her shocked reaction is given in a medium-shot showing her shifting out from behind the screen, her face partially hidden.

Mizoguchi has picked one variant of the overheard-conversation schema: shot of speakers/ reaction shot of eavesdropper. But he’s done so in his own way, using the barely discernible kimono sleeve to signal Hatsuko’s presence in the full shot of the couple. Likewise, the shot of Hatsuko listening is far from the usual close-up. Like other Japanese directors, Mizoguchi was fond of this arresting single-eye image. He used it earlier in his career, as shown in the first frame at the top of this entry, from Hometown (Furusato, 1930). The second frame is the last shot of his last film, Street of Shame (Akasen chitai, 1956). Quite a shot to end your career on, I’d say.

Most Japanese directors use this single-eye framing as a one-off flourish, but not Mizoguchi. The device epitomizes his demand that we concentrate on a detail. Isolating half a face gives impact to the slightest shift in the eye and eyebrow. Moreover, the split face reappears as a pictorial motif later in the scene.

As Matoba says he’ll go back to Tokyo for his doctorate, Mizoguchi cuts back to the setup for the second shot. Hatsuko moves left to sit on a chair around the corner from the sofa. This prepares for another, more prolonged game of visibility.

Now we get a thirty-second take of the couple on the sofa. As the scene develops, it becomes evident that Matoba is seducing Yukiko. Hatsuko slips in and out of visibility, her actions responding to and even echoing Matoba’s pressure on the girl. First, as he talks with Yukiko, we see Hatsuko’s sleeve and shoulder, between the vase and his shoulder. But as he slips his arm around Yukiko, her elbow moves aside, in an echo of his gesture.

Then, when Matoba presses his attention (“We’ll help each other . . . Depend on me”), Hatsuko’s face pops into view as her fingers emerge to grip the edge of her chair. Mizoguchi then lets her face subside, again slicing it in half.

In effect, this shot replays and expands upon the tactic governing the earlier two shots. Again we get the just-noticeable presence of the sleeve, but now rhyming with the action in the foreground. And again we get the facial reaction, impeded by a vertical cutoff, but this time in the distant shot rather than in a closer view. It turns out that those first four shots were training us for this more intricate game of vision.

At the moment Hatsuko’s face is sliced in half, Mizoguchi cuts. Now he prolongs the close view as he had extended the full shot of the couple. In this thirty-second shot, we watch her reaction, played out in slight modulations—changes in her facial expression, changes in the aspect of her face that we see, and changing relations to the curling palm plant in the vase before her.

We get a new angle on Hatsuko, slightly high, as Matoba says, “I’ll tell her.” Hatsuko stands up abruptly and the camera tilts to follow her.

With the simple action of her rising up, Mizoguchi changes his composition sharply. Hatsuko’s position in the frame changes only a little bit, but the massive vase on the left gives way to the curling stalks on the right. Radically refreshing a shot through minimal means is one felicity of Mizoguchi’s art.

Then, as if the full import of Matoba’s betrayal dawns on her, Hatsuko lowers her head sadly. Again her eyes are split up, this time thanks to the twisting stalk. In a characteristic Mizoguchi gesture, she turns from the camera, as if ashamed to face us, but also summoning up reserves for the next emotional shift.

When she turns back, her face burns.

I take this to be the scene’s emotional climax. Mizoguchi could have given it to us much sooner, by having Hatsuko turn angry as she peeped out from behind the screen. Instead, his game of vision allowed him to build patiently toward this unimpeded shot of her reaction. It prepares us for the next stages of the drama, later scenes in which she will confront her patron and launch jealous accusations at Yukiko.

Now we hear the performance ending, and Hatsuko lifts her head. This phase of the scene ends when Mizoguchi cuts to audience members coming into the lounge and greeting her.

By 1954 Mizoguchi had surely seen The Little Foxes. Had he decided to redo Wyler’s virtuoso staging in his own manner?

Both directors work with similar ingredients: overheard conversation, depth shots, judicious close-ups, and partial views. But the narrational weightings differ. Wyler’s film aligns and allies us with the people talking, whereas A Woman of Rumor ties us to the listener. (3) Wyler’s eight shots take eighty-one seconds; Mizoguchi’s eight shots take about two minutes.

Wyler’s handling is brisk, tense, and remarkably nuanced within the Hollywood tradition. Mizoguchi gives us his scene more sedately, wringing just-noticeable differences out of unassertive performances and simple elements of setting. No slap here, just a drama of wounded pride, lost love, and jealousy played out in the face, back, and sleeve of Tanaka Kinuyo, shifting behind a floral arrangement. What Wyler gives us as one sharp effect, Mizoguchi turns into a delicate, prolonged game of vision.

Am I fussing over minutiae? No; Wyler and Mizoguchi did. We just have to follow where they lead. As I try to show in my essay on blinking in cinema (4), directors attend closely to things that might seem trivial. Our analysis needs to be as fine-grained as their craft and artistry.

Oh, yes: at Venice Ugetsu won the Silver Lion. Wyler had to be content with Roman Holiday’s three Academy Awards.

(1) I sketch some of the possibilities in On the History of Film Style (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997), 225-227.

(2) For more on Mizoguchi’s competition with Wyler, see Figures Traced in Light (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 134.

(3) I’m referring to Murray Smith’s deft analysis of what he calls alignment and allegiance in our relation to film characters. See Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), Chapters 5 and 6.

(4) “Who Blinked First?” in Poetics of Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2007), 327-335.

PS 3 December: Thanks to Michael Kerpan for a name correction, and for the information that Woman of Rumor was once available on a French DVD.

PPS 27 February 2008: Good news. Now Woman of Rumor is available on the wonderful Eureka! Masters of Cinema series, along with the superb Chikamatsu Monogatari. The discs come with voice-over commentary by Tony Rayns and essays by Keiko McDonald and Mark LeFanu.

Walk the talk

The Magnificent Ambersons.

“It’s only history,” Jack Valenti is reported to have said when allowing scholars access to MPAA files. (1) After studying Hollywood for over thirty years, I should be used to the ways in which trade journalists (and some critics) forget or ignore historical precedents in moviemaking. But I still get bug-eyed when I encounter something like the Variety piece on TV director Tommy Schlamme (Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip).

The subhead tells us that this DGA nominee is known for his “hallway shots.” That gets my interest.

I lose interest fast. The writer tells us that Schlamme

developed the “walk and talk” on Sports Night and then mastered it on The West Wing.

The shot—which features two or more actors moving from one location to another on the set, often from one office to another via a hallway—has become a Schlamme signature.

The first sentence could be read as saying that Schlamme invented the walk-and-talk. Since I spent a little time studying this technique in The Way Hollywood Tells It, my inner film historian cries out, Aarrgh. Long before Sports Night (aired 1998-2000) and The West Wing (1999-2006), movies were developing such bravura shots.

The oblique view

In the prototypical walk-and-talk, two or more characters advance, and the camera tracks along, keeping them centered as they move through the environment. Such shots are quite uncommon in the silent cinema, but they emerge in 1930s films from many countries.

They were truly “signature shots” for Max Ophuls and the lesser-known Erik Charell. In Charell’s captivating The Congress Dances (1931) Lillian Harvey sings while a carriage takes her through an entire town and into the country, all in flowing tracking shots. Call it a ride-and-sing.

If that’s not as pure an instance as you’d like, we can find nice ones during a street scene of The Thin Man (1934). A more somber example occurs in Mizoguchi Kenji’s Story of the Last Chrysanthemums (1939), with the camera in a river bed angled upward at the couple it follows.

Usually such traveling shots from the 1930s and 1940s are shot obliquely to the actors. That is, the performers are seen in a ¾ view, and they walk along a diagonal path with respect to the frame edges; the camera moves on a similar trajectory. Sound cameras were mounted on dollies that usually ran on tracks. Framing the actors head-on raised problems with this gear. Performers couldn’t walk smoothly if they were stepping within rails, and there was a risk that the rails in the distance might appear in the frame. It was simpler to set the camera at an oblique angle so that actors could walk unimpeded and the tracks wouldn’t be seen. Directors continued to use this framing into the 1950s, as in Welles’ Othello (1952) and Fuller’s Forty Guns (1957). Both are unusually long takes; in the second, poor Gene Barry seems to be panting to keep up with the other men.

Back off

Today’s walk-and-talk is more likely to be a head-on framing, with the camera retreating from the actors. (More rarely, it dogs them from behind.) With a retreating Steadicam, you don’t have to worry about glimpsing the ground or floor behind the actors, in the distance, since there are no track rails to be exposed. Again, though, we have some precedents, most famously the splendid camera movements, evidently executed with a crane, in the ball sequences of The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), when George and Lucy stroll through the party.

When location shooting became more common in the 1940s and 1950s, cameras could be supported on more versatile dollies that didn’t require track rails, and these reverse-tracking shots become a bit more common. Kubrick, highly influenced by Welles and Ophuls, captured his officers striding through the trenches of Paths of Glory (1957). Vincent LoBrutto’s information-packed book (2) tells us that Kubrick’s dolly rolled backward on the planks that the actors walked on (authentic details, as boards were indeed used in the muddy trenches). Godard’s long traveling through the office lobby in Breathless (1960) was shot from a wheelchair.

Such head-on (and tails-on) shots can be found in several films well into the 1970s, as in Arthur Hiller’s The Hospital (1970). In fact, hospitals, police stations, and other sprawling institutional spaces seem to invite this approach.

By the 1980s, these shots proliferate in American films largely because the Steadicam makes them easy. One famous example is De Palma’s Bonfire of the Vanities (1990), which follows the drunken Peter Fallow through a hotel as he picks up and drops off many other characters.

Today such shots are very common in both high- and low-budget films. Schlamme’s “signature” device seems to be in pretty wide circulation. At best it’s a convention, at worst a cliché.

They’re called actors; let them perform action

I argue in The Way Hollywood Tells It that walk-and-talk is one of two principal staging techniques of contemporary Hollywood. The other, usually called stand-and-deliver, plants the characters facing one another and simply cuts from one to the other. The scene is built primarily out of singles (shots of only one actor) or over-the-shoulder framings. Here’s a typically static dialogue scene from The Matrix Revolutions (2003).

Both stand-and-deliver and walk-and-talk began in the studio era, decades ago, but then there were other options as well. Directors cultivated smooth, unobtrusive blocking tactics that moved characters in ways that reflected the developing scene. The actors had to perform with their whole bodies, and bits of business motivated them to circulate through the setting and turn toward or away from the camera. One example given earlier on this blog is from Mildred Pierce; here’s another, from the program picture Homicide (1949).

Detective Michael Landers has a hunch that the purported suicide of a former sailor is really murder. He has to persuade Captain Mooney to let him pursue some leads out of his jurisdiction. Today this might be played out in a stand-and-deliver session, with both men seated and shot/ reverse-shot cutting carrying the scene. But the director Felix Jacoves decides to let his actors earn their money through ensemble staging, not merely line readings. Here are just three shots from the middle of the scene that illustrate my point.

Landers stands at Mooney’s desk and gets a refusal. As he turns away to the left, Mooney walks to the rear files to put the papers away.

As they’re retreating to the opposite ends of the screen, Landers’ partner Boylan, who’s been offscreen for this phase of the scene, strides into the center and pauses at the door. The result of this choreography is both a balanced three-point composition and a chance to let us observe Boylan’s skeptical reaction to Landers’ next plea.

The camera tracks in as Landers approaches Mooney. Boylan shifts closer as well. What seems somewhat stagy as we analyze it doesn’t look obtrusive on the screen, because we’re following Landers’ arguments and watching the older men’s reactions. The closer framing and the position of the men, now face to face rather than separated by a desk, raises the dramatic pressure. As Landers pauses, Mooney folds his arms—a simple piece of body language that lets us know he’s still resisting.

Now a cut to Mooney, in an OTS framing, stresses his continued resistance as he tells Landers off, and a reverse shot gives Landers’ angry reaction.

Interrupting the sustained take, the shot/ reverse shot cuts have gained more emphasis than if they were part of a string of OTS shots. Jacoves has saved his cuts and closer views for a moment that raises the stakes visually as well as dramatically.

I’m not claiming that this is a brilliant stretch of cinema. (But you have to like a plot in which the hero defeats the killer by denying him access to insulin.) It’s just that the sequence activates, in a way that directors once took for granted, aspects of film art that we don’t find too often nowadays. Once you didn’t have to choose between Steadicam logistics and static dialogue; there is a very wide middle ground if you’re willing to move actors around the set and give them some body language and prop work. No need for a walk-and-talk here.

Schema and revision

The Variety article explains that Schlamme utilizes his long walk-and-talks to save time and money. But directors in the studio era shot their fully elaborated scenes like that in Homicide to be economical as well. If actors know their lines and hit their marks, playing out pages of dialogue in a few sustained setups can be very efficient; the Homicide full shot consumes 45 seconds. I’d argue that most contemporary directors have never learned to stage scenes this way. It’s a lost skill set. I make the case in more detail in Figures Traced in Light and The Way Hollywood Tells It.

To some extent, however, another skill set has emerged. Some walk-and-talks in The West Wing and other programs have an extra feature that the Variety writer and I haven’t mentioned. Often character A and B are walking toward us down the corridor, then B drifts off and C catches up with A. A and C walk for a while, then A peels off and C picks up somebody else, and so on. This approach is suited to multiple-protagonist dramas. You can show the plotlines crossing and separating.

I’m no TV historian, but I think that this technique showed up on St. Elsewhere (1982-1988), and it’s definitely on display in ER (1994-). Hospitals again. I think we also find this mingling/ separating choreography in contemporary film, but I can’t recall many examples in earlier eras. You could argue that one of the shots in the Ambersons’ ballroom does this, though I don’t think it’s a pure instance. (The principle of overlapping character actions is at work in many Renoir films, most famously in the final party melee in Rules of the Game, but Renoir doesn’t employ what we’re calling a walk-and-talk.) Did movies pick up this intertwined walk-and-talk from TV or vice-versa? I don’t know. If you do, drop me a line!

In On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light, I argue that stylistic change in filmmaking often follows a logic of what art historian E. H. Gombrich calls schema and revision. (3) A pattern or practice becomes standardized, but then creators extend it to new situations or find new possibilities in it, and they modify it.

Camera movements have long been used to link characters. For instance, when Nick Charles circulates drinks in The Thin Man, Van Dyke tracks leftward to follow him from guest to guest.

So maybe in the 1980s and 1990s, when ensemble stories had to balance attention among several major characters, directors blended the multiple-interaction aspect of lateral camera movements with the schema of the advancing walk-and-talk. The result makes characters move in and out of each others’ orbits along a single trajectory. Whoever came up with this device, I’d speculate that it arose from the realization that the backing-up walk-and-talk could be repurposed for dramas following the fates of several protagonists.

It’s only history, but it matters if we want to understand stylistic continuity and change.

(1) Thanks to Richard Maltby for passing this along.

(2) Vincent LoBrutto, Stanley Kubrick: A Biography (New York: Fine, 1997), 141-142.

(3) E. H. Gombrich, Art and Illusion: A Study in the Psychology of Pictorial Representation (Princeton, N. J. Princeton University Press, 1960), especially Chapter III.