Archive for the 'Directors: Morris' Category

Venice 2018: Assorted malefactors

Ying (Shadow).

DB here:

You don’t have to be an addict of crime fiction to notice that bad behavior–from lying and cheating to assault and murder–is a prime motivation in all genres of storytelling. A gripping plot often depends not on innocent mistakes but something worse: an assassination plot (Macbeth), a savage robbery (Crime and Punishment), wicked mind games (Les Liaisons dangereuses). Some of my favorite films from the latest Venice Film Festival feature scurrilous intrigue and a whole lot worse. Hell, in one movie the subject was happy to be compared to Satan, and that was a documentary.

Shadow warrior

After the extravagantly peculiar Great Wall, Zhang Yimou has come back with a more sober, somewhat arty wuxia drama. Leaning a bit on the premise of Kurosawa’s Kagemusha, Ying (Shadow) presents a king trying to reclaim territory with the aid of a crafty general. But he’s relying on a ringer; the real general languishes in a secret chamber recovering from a severe wound. Court intrigue–the general’s wife falls in love with her husband’s double, the king’s sister resents his manipulation of her–builds toward a massive military attack on the Jing stronghold. The sister, in rebuff to the enemy’s insult to her, enlists in the ranks as well.

It’s quite a show. For one thing, Zhang has reengineered the color-design principles of Hero. There each flashback episode was keyed to a different palette.

In Ying, the settings exist almost entirely in deep blacks and soft grays. For most of the film, only flesh and blood are given in their natural colors, and even then they are pastels.

For another thing, in contrast to the overcast skies of Hero and in perhaps another Kurosawa nod, here it’s almost always raining. This constant downpour extends the gray-black color palette of the palace to the massive landscapes.

Above all, the training of the young imposter in a technique of fighting with a metallic umbrella leads to some memorable combat sequences. Little do we realize in the initial practice sessions that the umbrella technique will expand on a grand scale. Pei’s troops invade a town using umbrellas as bobsleds, and they attack the enemy with umbrellas as scythes and buzzsaws. Despite the fact that digital rain doesn’t bounce off shoulders or trickle down the tracery of armor, the water-drenched attack at the climax of Ying yields the tingling sense of tactile spectacle that we’ve come to expect from the maker of Red Sorghum.

Cops and/as crooks

Dragged Across Concrete (production still).

In another but not wholly different genre, we have S. Craig Zahler’s Dragged Across Concrete. I was unfamiliar with his two earlier features, Bone Tomahawk and Brawl in Cell Block 99, though alert viewer Dave Kehr urged me to see the latter last year. (I tried, on streaming, but I gave up because the image was too small; Zahler’s eye is calibrated for the big screen.) Now, seeing this latest enterprise smashed across the Lido’s Darsena screen, I’m here to declare myself a fan.

It’s got a neat structure. There are two protagonists. We’re first introduced to Henry Johns, a discharged prisoner. He’s ready to reenter a life of crime to keep his disabled brother safe and rehabilitate his mom, who’s tricking to support her drug habit. After twenty minutes, he drops out of the plot and we pick up Brett Ridgeman, a cop whose menacing interrogation techniques, captured on cellphone video, result in a suspension. Pressed by money problems and his wife’s MS, Ridgeman decides to get “proper compensation” by ripping off a gang planning a heist. Of course Henry and Ridgeman’s trajectories intersect, while drawing in others: Henry’s sideman Biscuit, Ridgeman’s partner Anthony, and a woman working at the company that’s the target of the robbery.

At two and a half hours, Dragged Across Concrete might seem to be an overinflated genre movie, but it owes its leisurely pace, I think, to the tradition of crime novelists like Lionel White, George V. Higgins, Elmore Leonard, and George P. Pelicanos. In their work crime, duplicity, betrayal, and revenge are at the center of a web of human relations. Unrestricted narration follows outlaws, cops, and bystanders whose fates will be intertwined with acts of violence. You need a certain amount of time to give solidity to the lives of these stakeholders in criminal action.

The sweep of such plotting allows us to appreciate irony, especially when characters misjudge each other’s motives. In Zahler’s film, the split structure of the narration–setting up Henry before we see Ridgeman–pays off in several ways. Having access to the frustrations that push Henry back into crime allows us to judge Ridgeman’s occasional bursts of bigotry as both understandable (given the treatment of his daughter in the neighborhood) but no less hateful. At the climax, there’s a crisis of trust that depends on mutual ignorance. Both Henry and Ridgeman err because each man doesn’t know something crucial about the other.

The film’s length is also warranted by Zahler’s classical approach to composition and cutting. He knows how to exploit anamorphic widescreen, to let the camera stay still and watch action unfolding.

The film’s title summons up Sam Fuller sensationalism (and Zahler’s overheated prose in his novels isn’t far removed from Sam’s). But the film reminded me of Jean-Pierre Melville and Kitano Takeshi, partly for the laconic dialogue but also for the deliberate pacing. (The average shot length is 6.5 seconds, about twice what we find in most Hollywood movies today.) Lacking Tarantino’s self-congratulatory flamboyance, Dragged Across Concrete exemplifies the power of a dry but not unemotional approach to genre conventions.

The Forties, yet again

Charlie Says.

Police thrillers like Dragged Across Concrete became salient creative options in the 1940s, as I tried to suggest in my book about that era in Hollywood. Other 1940s options surfaced in two other crime-based movies I saw at Venice.

The first, rarer choice, was the chaptered film, the movie broken into blocks that are marked as distinct. Meet Me in St. Louis does it by season, Holiday Inn by, well, holidays. We’ve become used to chaptering since Pulp Fiction revived the scheme.

In The Ballad of Buster Scruggs, Joel and Ethan Coen literalize the technique by beginning with an old-fashioned book consisting of six chapters. The tales all center on the American West, and each one is introduced by a captioned color plate and ends with a glimpse of the closing passages of text.

This direct address to the audience is carried on in the first episode, “You seen ’em, you play ’em.” Here the gunslinger Buster Scruggs tries to charm us while singing “Cool Water.” The conceit is that a fancy-pants singing cowboy is planted in the grubby, dangerous west of actual history.

At first Buster dispatches fast-draw artists, but when he meets his match he’s lofted to heaven in a goofy cadenza that recalls stretches of The Big Lebowski.

Thereafter we get tales of bank robbery and lynching (with a shaggy-dog punch line), a bleak carnival sideshow, gold prospecting, a wagon train, and a mysterious stagecoach ride. All are rendered with the patented Coen panache. Such a pleasure to see a movie that is designed, from first frame to last, to give you time to see everything. The Coens’ love of the grotesque, their eagerness to satirize movie conventions while still honoring them, their parodic side (e.g., the opening Leone riffs), and their gift for gorgeous landscapes and catchy tunes–all are here.

Still, the wagon-train episode, much in the spirit of True Grit, shows that not everything is fodder for mischief. The highly formal, archaic dialogues and grave sincerity of the performances in this section are for me deeply moving. The chaptering device itself carries a certain warmth; we might be kids discovering a great-grandparent’s childhood reading.

Mary Harron’s Charlie Says uses a more common 1940s template, that of an inquiry that triggers flashbacks to the past. It’s also, as Harron notes, a woman-in-prison movie. Karlene Faith is a feminist and social activist who counsels three women on Death Row. They participated in the murders instigated by cult leader Charles Manson. As she gets to know them and they probe her own life, we’re shown increasingly brutal episodes of their absorption into Manson’s brood.

The task of Harron and screenwriter Guinevere Turner was to make the women sympathetic and comprehensible. The script might have offered mini-biographies showing how each one’s unfulfilled life led her to fall prey to Manson’s manipulation. Instead, they make one woman, Leslie nicknamed Lulu by Charlie, our primary focus, and through her they lead us gradually into the monstrous crimes.

The early flashbacks, attached to Leslie as she enters the fold, emphasize Manson’s rather mild, almost offhand seduction style. At first he comes across as a gentle, guitar-strumming hippie wooing his followers with a lifestyle challenge: Give up consumerism, learn to live simply, share the love. Certain signals–the men always eat first, Charlie has claim on all the women–are outweighed by Manson’s glowering conviction and the group’s hopes that his songs will earn a record contract.

The flashbacks trace a shift from communitarian idealism to “subversive” rock music (the coded message in the Beatles’ “Helter Skelter”) to whacked-out politics. (Manson promises a race war in which blacks will need a leader like him.) Men as well as women fall under Charlie’s patriarchal management style. By the end, murdering the piggies through home invasion comes to be the ultimate test of Manson family values.

The flashbacks, shot in a nervous style in sun-soaked terrain, contrast with the locked-down camera and drab prison surroundings of the present. The unpretentious production values are matched by a sober style that favors the performances, particularly those of Hannah Murray, Merritt Wever, and in the flashiest role Matt Smith as Manson. In all, it’s a very worthy, unsensational effort to understand how naive idealism can be recruited by lunatic evil.

Better to reign in Hell

American Dharma (production still).

Speaking of lunatic evil, Donald Trump has had many abettors and acolytes, but few are as clever and intellectually pretentious as Steve Bannon. Errol Morris’s interview film, American Dharma, premiered at Venice and was put to the blade in the press conference.

Reporters’ objections seemed to me twofold.

You were too easy on him. You didn’t pose enough hard questions and you cut away when he fell silent. Morris replied that this was an investigation, not a debate. He wanted to probe Bannon’s worldview, not “pin him to the wall, like a butterfly expert handling a specimen.” And Morris does push Bannon on several points, notably the contrast between his apocalyptic intentions (Trump is the “blunt-force candidate, an armor-piercing shell”) and his earnest claim to be fighting for those people who want a stable, steady life. For my part, I thought that Morris scored points whenever the garrulous Bannon didn’t reply or changed the subject.

In addition, Morris peppers Bannon’s discourse with montages of cutaways to internet news and commentary. Like the newspaper headlines of The Thin Blue Line and Tabloid, this swarm of Facebookings, Twitteries, and soundbites acts as both challenge to what’s been said and a reminder of how the media snatch up phrases and images and spew them back at us, complicating and sometimes obscuring our understanding. At the very least, we’re reminded that there is pushback to virtually every lie put forth by the Trump regime: the Resistance will be videoized.

Nothing new here. What did we learn from this? Well, said Morris, we learn that “at the heart of his beliefs is a deep self-deception.” Morris challenged Bannon to explain how, if he believes that Trumpism is a populism on behalf of the forgotten middle class, all his policies are aimed to strengthen the wealthy and weaken the ordinary citizen. Bannon got quiet. And though Bannon claims to be a rationalist, he soon enough rails against rationalism.

All of which makes him a guy who has given a tongue bath to the Blarney Stone. A Hollywood investor with ties to the videogame industry, Bannon strikes me as less a thought leader than a canny VC opportunist, spraying out memes like a scriptwriter in a pitch session. He even assures us solemnly: “The medium is the message.” In his cascade of clichés I saw the desperate self-confidence of a hip boomer who wants to be the brightest boy in the meeting.

Along these lines I thought I learned something else important. Bannon the vaunted intellectual gets his inspiration from pop culture. Most of what I’ve read about his ideas emphasize their philosophical pedigree–his readings in Eastern and Western religion, his defense of Julius Evola–but it turns out that Bannon is a geek like the rest of us.

When he draws life lessons from Paths of Glory and The Searchers, Morris punctures these absurd pretensions simply by literalizing them. This creep casts himself as Kirk Douglas or John Wayne? Like Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight, Bannon claims, he has prepared a carouser for rule before the pupil betrays the mentor. So Morris straight-facedly inserts Welles’ footage, and Bannon, no Fat Jack, is thereby shrunk. Likewise, Morris makes monumental fun of Bannon’s shallowness by building a duplicate of the Quonset hut of Twelve O’Clock High, Bannon’s favorite movie. In this set Bannon, not exactly Gregory Peck, is interrogated before Morris sets it ablaze.

When he draws life lessons from Paths of Glory and The Searchers, Morris punctures these absurd pretensions simply by literalizing them. This creep casts himself as Kirk Douglas or John Wayne? Like Falstaff in Chimes at Midnight, Bannon claims, he has prepared a carouser for rule before the pupil betrays the mentor. So Morris straight-facedly inserts Welles’ footage, and Bannon, no Fat Jack, is thereby shrunk. Likewise, Morris makes monumental fun of Bannon’s shallowness by building a duplicate of the Quonset hut of Twelve O’Clock High, Bannon’s favorite movie. In this set Bannon, not exactly Gregory Peck, is interrogated before Morris sets it ablaze.

I didn’t think that the journalists in the press conference gauged the ways in which Morris made Bannon seem naive. But I always forget that a hermeneutics of pop-culture justification, with The Simpsons and The Matrix fodder for philosophers trying to fill their courses, is taken for granted now. Bannon encountered Twelve O’Clock High when it was taught as a leadership model in, of all places, Harvard Business school. To my mind, Morris shows that the would-be highbrow’s search for allegories in mass culture is a caricature of serious thinking.

Another piece of news: Bannon admits to being a Miltonic rebel angel, one who would rather reign in Hell than serve in Heaven. Think about that. Morris got Bannon to embrace Satan. He asked, with justification: “How many interviewers have done that?” Errol Morris, boy detective, may have revealed the real puppeteer behind Trump’s coup d’état: the petty overachiever swollen with dreams of grandeur drawn from movies.

This is my last dispatch from a festival that became a high point of my cinephiliac life. Apart from seeing fine films in splendid circumstances, talks with Dave Kehr, Chris Vognar, Michael Philips, Glenn Kenny (some choice reviews here), Stephanie Zacharek, Mick LaSalle, Kim Hendrickson, Peter and Françoise Cowie, Alberto Barbera, Michel Ciment, Olaf Möller, and other friends have set me thinking ever since.

As ever, thanks to Paolo Baratta, Alberto Barbera, Peter Cowie, Michela Lazzarin, and all their colleagues for their warm welcome to this year’s Biennale.

For more Venice snapshots, see our Instagram page.

October 31, 2018: Netflix has announced that The Ballad of Buster Scruggs will be narrowly platformed starting November 8 and will premiere on its streaming service on November 16; also on the 16th it will show in selected theaters in the US and Europe, as well as Toronto.

Errol Morris, boy detective

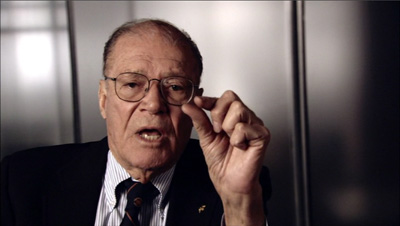

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara.

DB here:

Over a couple of sunny days in late October Errol Morris visited the University of Wisconsin—Madison. It was something of a homecoming. Morris took his BA in history here, and was inspired by two legendary teachers, Harvey Goldberg and George L. Mosse. (“The UW saved my life.”) After a few years in graduate schools (Princeton, Berkeley), he went into filmmaking, working with Werner Herzog on Stroszek while it was shooting in Wisconsin.

Morris’s first film, Gates of Heaven (1978), examined pets, their owners, and the cemeteries that cater to both. Vernon, Florida (1981) reinforced Morris’s reputation as an aficionado of the backwoods bizarre. His reputation widened with The Thin Blue Line (1988), a true-crime story that cast doubt on whether an innocent man had been imprisoned for a murder. I’d argue that this film, along with Roger and Me, played a crucial role in opening theatrical markets to documentary film. From then on, Morris has been acclaimed as one of our finest filmmakers, finally receiving an Academy Award for The Fog of War (2003), a study of Robert McNamara’s prosecution of the war in Vietnam.

Morris’s first film, Gates of Heaven (1978), examined pets, their owners, and the cemeteries that cater to both. Vernon, Florida (1981) reinforced Morris’s reputation as an aficionado of the backwoods bizarre. His reputation widened with The Thin Blue Line (1988), a true-crime story that cast doubt on whether an innocent man had been imprisoned for a murder. I’d argue that this film, along with Roger and Me, played a crucial role in opening theatrical markets to documentary film. From then on, Morris has been acclaimed as one of our finest filmmakers, finally receiving an Academy Award for The Fog of War (2003), a study of Robert McNamara’s prosecution of the war in Vietnam.

Morris’ visit was the culmination of months of screenings in several Madison venues. The big weekend was ushered in by a lecture by Carl Plantinga, one of our most distinguished scholars of documentary film. He’s a professor at Calvin College, and like Morris, he’s a Wisconsin graduate (my Ph. D. student, ahem). Dave Resha, who wrote a dissertation on Morris, and Bill Brown, our accomplished documentarist, were on hand to join our guest on a panel. Perky and boyish, Morris offered a public lecture at the Student Union. Next day, the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art hosted a screening of his new movie Tabloid and a Q & A.

Morris is an exuberant presence, onstage and off. I could fill this entry with one-liners and anecdotes.

My high-school guidance counselor told me, “You should go to Wisconsin. They take anybody.”

I sometimes think of myself as someone who should be beaten up a lot.

Just because he’s a victim doesn’t mean he isn’t an asshole.

The electric chair is a very scary thing.

My wife says I should give up Twitter and start writing for fortune cookies.

Fred Leuchter, electric-chair repairman and Holocaust denier, smokes constantly but won’t be filmed with a cigarette. He explains, “You have to understand, Errol. I’m a role model for children.”

I don’t think anybody knows how crazy they are. I include myself and the persons in this room.

Morris’s visit was so stimulating that it got me thinking afresh about his career. While many documentaries engage in fact-finding, Morris’s films recall for me the figure of the classic detective, the nosy fellow drawn to secrets high and low. Morris is a fan of film noir (he thinks that Detour is at least as good as Citizen Kane) and he worked for a time as an investigator. His only fictional film, The Dark Wind (1991), is adapted from a Tony Hillerman mystery. It’s useful to think of Morris’s documentaries as private investigations—not illustrating an argument but exploring the mysteries around a situation or a personality. Like any investigation, his may lead nowhere or create more puzzles than it solves. Morris shines his penlight in some dark places, finding not only clues but some embarrassing items in the drawer or the back of the closet. The truth often has a sordid side, but that can harbor its own pleasures.

The filmmaker and the murderer

The Fog of War: “Rational individuals came that close to total destruction of their societies.”

History is a crime scene, and you’re the detective. Film can be a tool to solve the mystery.

Errol Morris

Morris’s recent films on the Vietnam War and on the abuses at Abu Ghraib prison (S. O. P.: Standard Operating Procedure, 2008) are somber inquiries into the mechanics of power and bureaucracy. Balzac said that behind every great fortune lies a great crime; for Morris behind every war lies many such crimes. Early on McNamara admits that his misjudgments cost thousands of lives. Morris’s reconstructions of prisoner treatment at Abu Ghraib are chilling neo-noir, filmed in chiaroscuro and featuring agonizing slowed-down imagery, as when a shotgun is fired into a cell and shells tumble out of the chamber.

He’s particularly interested in the photos snapped by the Abu Ghraib guards, and they provoked him to his lengthy New York Times blog essays on the philosophy of photography. S.O.P. and his writings ask how reliable a photograph is, how we can so easily miss what’s before us, and how what’s really happening–the chain of command, the war crimes that aren’t photographed, even another witness–can be hidden by the images we make. He often invokes a soldier’s remark about the Abu Ghraib pictures: “When you see a picture, you never see what’s outside the frame.”

The philosophical quests in Morris’s work lay at the center of Carl Plantinga’s presentation, “Errol Morris and the Anosognosic’s Guide to Documentary Film.” Carl trained as a philosopher, and his lecture teased out many concerns that weave through Morris’s work. On his website, Morris has written about anosognosia, the condition of not knowing that you don’t know something. It’s the realm of Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns.” Anosognosia, Morris claims, is “a universal condition of the human race.”

Carl’s talk developed this idea along several lines. Morris, he suggested, is a critical realist who believes that reliable knowledge is in principle attainable, even though we seldom attain it. Accordingly, Carl suggested, the films expose the mistaken beliefs of his subjects, their “epistemic distortions” revealed in behavior and, especially, language.

But the pathway to truth can’t be the cinéma-vérité methods of straightforward recording, if only because simply turning on the camera won’t give us access to the “mental landscapes” his speakers inhabit. For Carl, Morris deals in tragicomedy—sometimes bleak, sometimes absurdist, sometimes tinged with “fellow feeling.” His films can seem denunciatory, but they pause for moments of sympathy: a trial lawyer quits practice when justice is outrageously miscarried, the grunts at Abu Ghraib are scapegoated.

Carl invoked a controversy that has played out in academic circles but that Morris obviously feels passionate about. It centers on The Thin Blue Line. That film, some scholars argued, was a “postmodern” documentary. The conflicting testimony, rambling digressions, and incompatible replays seemed to display a corrosive skepticism about what really happened on the night that Officer Robert Wood was shot on a lonely Texas highway. Morris had apparently made a film about the impossibility of finding truth. Perhaps Morris encouraged that interpretation by remarks like this:

I like the irrelevant, the tangential, the sidebar excursion to nowhere that suddenly becomes revelatory. That’s what all my movies are about. That and the idea that we’re in a position of certainty, truth, infallible knowledge, when actually we’re just a bunch of apes running around.

Since then, though, Morris has been at pains to insist that The Thin Blue Line doesn’t say that arriving at a truth is impossible, only that it’s damnably difficult. Unlike the preformatted rhetorical documentary, a Morris film starts out from an uncertain place and moves into unknown territory. We may not arrive at certain truth or infallible knowledge, but that doesn’t mean that we’re forever floating in a realm in which belief in ghosts is as valid as belief in atoms. Randall Adams did not shoot Officer Wood, and David Harris probably did. Approximate but reliable truths are likely as close as we’ll get, and even those are very hard won. This is one reason Carl calls Morris a “critical realist”: There is a real world and there are true things to be said about it, but there are never any guarantees that we’ll find them.

Hence, again, the figure of the detective. The P. I. searches for the truth. The result may be partial, or vague, or so thickly wrapped in falsehood that it seems a pitiful thing. The trail is cluttered with distractions. With The Thin Blue Line, Morris developed a story line, starting with Randall Adams’ arrival in Dallas and ending with David Harris’s chillingly casual suggestion, captured on tape, that he was the guilty party.

The interviews provided the spine of Morris’s tale. But he embellished the interviews with inserts of documents (newspapers, police records), reenactments, and other images, some of them apparently irrelevant to the case: road maps, a drive-in’s popcorn machine, clips from Boston Blackie movies. In the terms we propose in Film Art, he gave his narrative form doses of associational form.

One function of this vagrant material is to remind us what any private dick knows: You have to sift through a lot of detritus to get to the important facts. (This idea seems literalized in the floating feathers and clumps of dust that irradiate the cell block in S. O. P.) Sometimes the detritus buries the facts, and you miss out. But some inquiries make progress. “It’s not just about constructing stories,” Morris says, “but finding things out.”

Morris’s films aren’t necessarily full records of an investigation but rather soundings and probes. The movies assemble, in provocative form, promising leads, false trails, and clues that are striking but still inscrutable. Sometimes what’s out of the frame is crucial. The viewer of The Thin Blue Line is likely to think that Harris’s climactic half-confession is what won Adams’ reprieve. In fact the decisive material was footage not in the final movie, drawn from interviews with Emily Miller and Michael Randell, along with proof that evidence was suppressed at Adams’ trial. As Morris is fond of saying, “What freed him was not the movie but the investigation.”

The lure of the lurid

Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control.

What amazed me was the number of murderers who’d come from Plainfield and the surrounding areas, so I started interviewing them, too . . . . At the time I remember my mother asking me why I didn’t spend time with people my own age. I said, “But mom, the murderers are my own age.”

Errol Morris

Emphasizing Morris’s search for truths may make him seem a more genteel filmmaker than he actually is. Another side of his work is an unabashed sensationalism. When I said to him, “You’re preoccupied with the weirdness of things,” he corrected me: “No, the profound weirdness of things.” The world is just plain strange (that’s part of what makes truth hard to get to) and it’s strange all the way down.

Morris has an appetite for free-range surrealism. Vernon, Florida began as an inquiry into a town whose citizens displayed a penchant for hacking off their arms and legs. (Pitching a fictional version, Morris proposed the one-sheet tagline: “If they would do this to themselves, think of what they would do to you.”) He has been intrigued by spontaneous human combustion, people struck by lightning, the search for Einstein’s brain, the breeding of giant chickens, and the efforts of a Minnesota man to build his own interstate highway.

At the limit stand figures preoccupied with end-of-life concerns—that is, the ending of other people’s lives. Morris’s time in Wisconsin with Herzog led him to Ed Gein, our state’s most famous grave-robber and the prototype for Norman Bates. Pretending to be psychiatrists, Morris and Herzog interviewed a serial murderer in California. Later, after working as a P. I., Morris heard of “Dr. Death,” a psychiatrist who specialized in testifying to the sanity of convicts on Death Row. A perfect subject for a movie, Morris thought, and checking into Dr. Death’s record he found Randall Adams’ case.

Morris’s cheerfully morbid curiosity, which puts him in the company of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, Ed Regis, and, of course, Herzog, is channeled into subjects that a high schooler might choose for a book report. Baby-boomer men, brought up on the Hardy Boys and Popular Science, are perpetual kids. Anything to do with magic, mystery, snooping, and weird science holds us fascinated. I’d bet that Morris has a set of William Poundstone’s wondrous Big Secrets books. How did he miss tackling UFOs?

So Morris is a connoisseur of weird science and lethal battiness. But it’s all in a day’s work for a P. I. The detective is inevitably drawn to seaminess, curiosities, and compulsions. Things that shock or disgust or baffle us can be clues to something we’d rather not face. In Morris’s hands, material that would shriek at us from supermarket racks can turn grotesquely comic (the early films), ominous (Thin Blue Line, Mr. Death), or strangely poetic (A Brief History of Time; Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control).

Come to think of it, Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control would also be a good title for Tabloid. Joyce McKinney’s saga has enough spice for a full issue of Weekly World News: beauty contests, religious mania, kidnapping, bondage, flight from the law, cloned puppies, and Joan Collins. There are moments that demand blunderbuss typeface. I still want my Mormon! He was a doo-doo dipper! Booger gave me five black jellyrolls! And no reenactments now, just interviews enhanced by found footage, snapshots and headlines hurled into the frame. Once we’re dizzied from the bombardment of alluring phrases (Manacled Mormon Sex Slave!), we’re yanked into a circulation battle. The Mirror and the Express are deploying operatives to buy stories that will undercut each other.

Come to think of it, Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control would also be a good title for Tabloid. Joyce McKinney’s saga has enough spice for a full issue of Weekly World News: beauty contests, religious mania, kidnapping, bondage, flight from the law, cloned puppies, and Joan Collins. There are moments that demand blunderbuss typeface. I still want my Mormon! He was a doo-doo dipper! Booger gave me five black jellyrolls! And no reenactments now, just interviews enhanced by found footage, snapshots and headlines hurled into the frame. Once we’re dizzied from the bombardment of alluring phrases (Manacled Mormon Sex Slave!), we’re yanked into a circulation battle. The Mirror and the Express are deploying operatives to buy stories that will undercut each other.

At some point we’re engulfed, and the tabloids become an alternative reality of magical transformations. An innocent girl, radiant in her own home movie, becomes a felon, and then her real transgressions come to light. The tabs’ endless escalation of sordidness, with each week’s scandal trumped by the next, gives the movie its pounding rhythm, the tempo of the rotary presses pumping out—what else?—stories that bury truth under trivia.

Except that this time around, the trivia are all we have, and the obsessiveness of the young McKinney is matched by that of the reporters pursuing her. Captured in pitiless high-definition, the men’s seamed faces glow with self-satisfaction and the thrill of the hunt. True, they’re investigators like Morris, and one journalist elicits some actual conversation with our offscreen filmmaker. (They discuss the phrase “barking mad,” which Morris wishes Americans used more often.) After a while, though, we can add these Grub Streeters to Morris’s gallery of people who talk and talk without any sense of what they’re giving away.

The great mystery

The Thin Blue Line.

Even as [the writer] is worriedly striving to keep the subject talking, the subject is worriedly striving to keep the writer listening. The subject is Scheherazade. He lives in fear of being found uninteresting, and many of the strange things that subjects say to writers—things of almost suicidal rashness—they say out of their desperate need to keep the writer’s attention riveted.

Janet Malcolm

The detective, by vocation, asks questions. A detective-story plot consists largely of following the investigator pounding the path, interrogating witnesses, suspects, and experts. (With time out for occasional pistol ambushes, seductions, and whacks on the back of the head.) What people say and how they say it can lead you to truth, or to the profound weirdness that informs the human condition, or both.

Hence the very special conditions for a Morris interview. Complex lighting, and in the later films artificial backdrops, create the aura of a special occasion. Hair and make-up are attended to. Up to twenty crew members are at work. Looming in front is the Interrotron, that mad-scientist rig of mirrors that lets the interviewee look at Morris while also looking into the camera. In a later development, several cameras are trained on the speaker. In all, it’s not quite like being dragged to sit in the hot seat at Headquarters, but there is an almost ceremonial surrender of autonomy. All the subject can do is talk, and aim it directly at us.

Morris does not provide questions in advance. He starts by saying, “I don’t know where to start.” He doesn’t pounce on his subjects (he calls them his “characters”). He speaks as little as possible, regarding it as best to let the people gabble on. Thanks to videotape, they can talk uninterrupted for hours. We seldom hear his questions. He never comes on camera to make himself the protagonist or star (à la Moore), nor does he provide a stream of voice-over narration (à la Curtis). We have simply to look at these people and listen to what they say.

During his stay in Madison, Morris referred often to the case of Scott MacDonald, the convicted murderer whose case journalist Joe McGinnis turned into a bestseller. Of particular interest to Morris was Janet Malcolm’s book about the case, The Journalist and the Murderer. MacDonald sued McGinnis for seeming to support his case during the trial, then publishing a damning account declaring MacDonald guilty as charged. Analyzing MacDonald’s litigation, Malcolm reflects on the betrayal at the heart of journalistic inquiry. The subject interviewed wants the story told his or her way; the writer, at least the writer of conscience, can never fulfill that pledge. The naivete of the subject is always shattered when the story is published, for the writer had another agenda.

Malcolm’s book intersects Morris’s concerns at several points: a tabloid murder, a man perhaps wrongly convicted, a subject sueing the writer (as Randall Adams eventually sued Morris). In particular, I think that Morris is taken with the idea that interviewees have a kind of compulsion to keep talking. They want to explain themselves fully, of course, and to justify what they’ve done. But they also want to prove themselves worthy of someone else’s interest. Compulsive confessors, they want to be caught and are always startled when they are.

Morris’s ultimate interest, Carl Plantinga noted, lies in people’s “mindscapes,” their private construals of reality. Morris seemed to agree. The great mystery, he said, is “human personality, who we are.” That includes all the madness and dirt. The surprises that pop out, Interrotron or no Interrotron, remind us that we’ll never completely crack the case.

For much more on Morris, visit his website. He tweets here. His New York Times essays on photography are now evidently behind a paywall, but an all-out search will reveal some of them. Here is a pdf of what I think is the first one. A more recent cycle starts here. A book of Morris essays is planned for publication.

The best compendium of Morris’s evolving ideas is Livia Bloom’s collection Errol Morris Interviews (University of Mississippi Press, 2010). From this book, I’ve quoted Morris’s remarks in Chris Chang’s 1997 Film Comment article “Planet of the Apes,” p. 56, and in Paul Cronin’s wide-ranging “It Could All Be Wrong: An Unfinished Interview with Errol Morris,” p. 165. My quotation from Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer is from pp. 19-20.

Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film has recently come back into print, and I discuss it briefly in a recent entry.

I wrote an analysis of The Thin Blue Line in Film Art, ninth edition, pp. 425-431. We contrast Morris with Michael Moore and other documentarists in Film History: An Introduction, third edition, pp. 544-548.

The Wisconsin symposium, Elusive Truths: The Cinema of Errol Morris, was a model of campus cooperation. Thanks to the Wisconsin Union, and especially the dedicated students of the WUD Distinguished Lecture Series, the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, our Cinematheque, the University of Wisconsin Foundation, the UW Arts Institute, and other agencies, not least my home Department of Communication Arts. We owe a special debt to Professor Vance Kepley who orchestrated the event with aplomb. A full record of events, sponsoring bodies, and people to be grateful to can be found here.

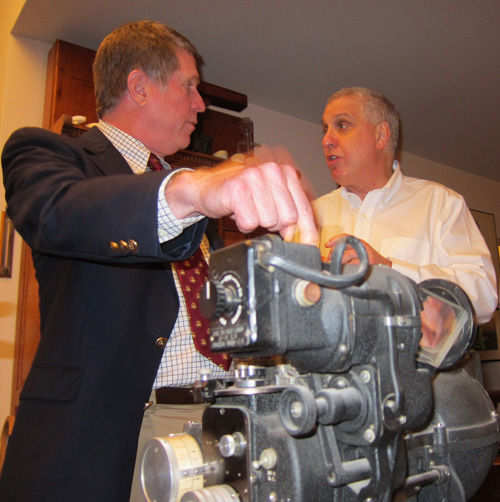

Vance Kepley and Errol Morris discuss the once-top-secret Norden bombsight.