Archive for the 'Directors: Ozon' Category

The trim, tight movie: Three variants at Vancouver

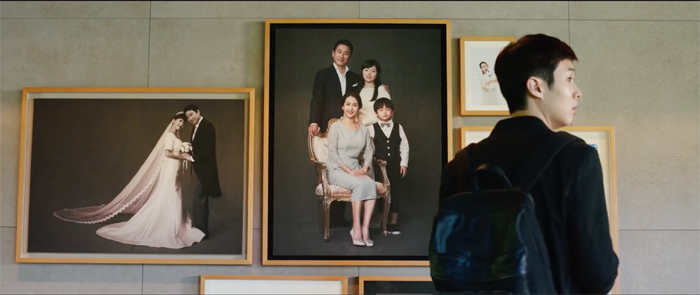

Parasite (2019).

DB here:

As a student of storytelling, I recognize that we can enjoy loose, episodic plots. But I also admire the shrewd craft of constructing a movie that develops a situation in precise, logical, yet surprising ways. Things may be resolved neatly, or not, but the satisfaction comes from the way that characters pursuing goals create conflicts, overcome obstacles, and change (or not) in the course of the action. American studio cinema developed its own version of this in what Kristin and I have called “classical Hollywood” plotting. Other countries have borrowed that model, adapting it to new needs but still keeping the storytelling trim and tight.

Three films on display at this year’s Vancouver International Film Festival illustrate some options. All have won acclaim at other festivals and constitute A-productions in their local industries. I enjoyed all of them, and I liked learning how broad principles of narrative construction can be treated in significantly different ways.

Storming the basilica

François Ozon’s By the Grace of God, a prizewinner at Berlin this year, turns Spotlight (2015) inside out. The American film follows the investigation of a news team bringing priestly pedophilia to light; it’s a detective story, with the victims serving as witnesses to the crime. By the Grace of God concentrates on the victims’ search for justice, and finds an unusual structure to give each one due weight.

The film is based on a real case in Lyon. The film starts with businessman Alexandre Guérin accusing Father Preynat of abusing him as a child. Surprisingly, Preynat admits he did the deed, so there’s no mystery to be solved. With the statute of limitations expired, the Church authorities decline to punish Preynat. He’s kept in service, and his duties still associate him with children. The only thing that worries Cardinal Barbarin is that Preynat didn’t apologize when Alexandre confronted him.

A pious Catholic, Alexandre trusts that if he appeals high enough in the Church hierarchy (even up to the Pope), some action will be taken. He is rudely awakened to the cynical willingness of Barbarin to stall and cast a smokescreen over the case. Alexandre decides to file a legal complaint and to find other victims to join him.

At this point, Ozon’s script takes an intriguing turn. The plot drops Alexandre and introduces us to another victim, François Debord, who is a fairly militant atheist. Investigating Alexandre’s charges, the police call on François’s parents. He told them of the abuse at the time, but they pressured him to stay quiet. Now he embarks on a crusade to find other victims to speak out. For some of them, the statute of limitations may not have expired.

Alexandre becomes a minor player in this stretch of the film, meeting François occasionally to plan strategy, but François is the motor of the action. His zeal leads him to yet another victim, Emmanuel Thomassin. We now follow him and learn how his life has been damaged quite severely by Preynat’s abuse.

Eventually the three men find more victims willing to go public, and by cooperating they confront the Church’s coverup.

With three sections each lasting 45-50 minutes, Ozon has mounted a block-construction plot (although without explicit chaptering). He has compared it to a relay race, with the story impulse passed like a baton from one character to another. And each phase of the action raises the stakes: growing proof of the Church’s malfeasance, a broader survey of the consequences of the crimes.

Ozon has also said that he tried to distinguish each of his three protagonists’ sections stylistically. Alexandre’s phase of action has highly economical narration, using the exchange of letters and emails (read in voice-over) to move the action swiftly, forcing us to keep up at every moment. When the action shifts to the flamboyant, web-savvy François, the emphasis falls on building online support for an organization. Emmanuel’s painful story is treated with more intimacy and empathy; the other men have overcome their childhood traumas and have buoyant families, but Emmanuel is adrift.

By the Grace of God has the carpentered solidity of Ozon’s Frantz (2016). If we can say that the French “Tradition of Quality” of the 1940s and 1950s persists today, it’s surely here in this taut, elegant piece of storytelling.

City on fire

Stylistically, Les Misérables doesn’t look as sleek and controlled as Ozon’s film. It’s shot in the free-camera style that’s now common throughout the world: handheld shots, fast cutting, tight framing on faces, lots of panning to follow the action. When cops brace three women on the street we get a rapid-fire exchange in the manner of Homicide: Life on the Streets.

Although we’re basically on one side of the confrontation, the cutting is somewhat freer than in classic continuity, as the above shot of Stéphane indicates. To emphasize the quasi-sexual gesture of Chris checking the young woman’s fingers for the smell of pot, the editing jumps the line before returning to the main setup.

Les Misérables, directed by Ladj Ly, is not quite as pure an example of the free-camera approach as Young Ahmed, (also shown at VIFF) because it affords a greater degree of “camera ubiquity.” It crosscuts among lines of action, and it relies on reaction shots that the Dardennes avoid. Still, the purpose is to immerse us, smashmouth fashion, in each scene’s conflict.

And there’s plenty of conflict. Stéphane Ruiz has joined a team of tough cops patrolling an impoverished Parisian suburb teeming with immigrants. To keep things under control Chris, the team leader, has formed alliances with drug gangs and the boss of the territory. Gwada, a Muslim cop, backs Chris loyally.

The main action, which consumes around 24 hours, shows Stéphane trying to bring a measure of humanity to the confrontations between his unit and the local residents. A petty crime escalates into a burst of police brutality, captured on video by a boy’s drone. The second half of the film puts the cops in conflict with one another and an increasingly outraged community ready to take on both the police and the gang leaders.

Ly has made short films and web videos, and while growing up in the banlieue projects he documented police actions.

For five years I filmed everything that went on in my neighborhood, particularly the cops. The minute they’d turn up, I’d grab my camera and film them, until the day I filmed a real police blunder.

Ly filmed the 2005 riots as well (365 Days in Montfermell), as part of the filmmaking collective Kourtrajmé. Les Misérables is called that partly because this is the district where Hugo wrote his masterpiece. “I wanted to show the incredible diversity of these neighborhoods. I still live there: it’s my life and I love filming there. It’s my set!” In 2018 Ly established a filmmaking school in Montfermell.

Although Ly comes from the world of documentary, he has a shrewd sense of fictional plotting. A prologue shows little Issa among thousands of Parisians celebrating France’s World Cup victory (above). It’s an image of diversity within national unity, but also a bit of narrative priming that makes us sympathetic to the boy. The rising tension of the action, from a childish prank through increasingly horrific scenes (one in a lion’s cage had me trembling) to a final cataclysm, is carefully constructed out of a series of misunderstandings, brutal decisions, overreactions, and desperate survival maneuvers.

There’s solid motivation and foreshadowing. The drone is established early as the all-seeing eye of the projects, steered by the withdrawn boy Buzz. Stéphane has reluctantly transferred to the Parisian police from the provinces because he wants to be near his son, in the custody of his ex-wife. This information prepares us for his sympathetic gestures toward the children of the projects. And just before the climax, Ly’s script gives us a pressurized nighttime pause, a sequence that cuts among all the adults we’ve seen trying to adjust to the day’s turmoil. Next day all hell will break loose.

Les Misérables shared the Jury Prize at Cannes last May with another VIFF entry, Bacunau. (Comments on this coming soon.) In the US it will be distributed, who knows how, by Amazon.

Class struggles

Viewers of Memories of Murder (2003), The Host (2006), and Mother (2009; also here) know that Bong Joon-ho has a fine hand with mystery, suspense, and abrupt plot twists. His skill is on full display in Parasite, Palme d’or winner in Cannes and already considered one of the most striking films of 2019.

As suits the Age of Inequality, the action centers on two families. The Kims live in a crammed basement and struggle to get by. When the son Ki-woo gets a job tutoring the daughter of the rich Park family, he schemes to insert all his family members into the household. (This recalls the stratagems of the play and film Kind Lady.) The Kims’ adroit manipulation of the Parks, especially the insecure helicopter mom, provides mordant comedy. But in a long central scene, the Kims’ scam starts to unravel. They’re shocked to discover what actually goes on in the splendid mansion they’ve taken over.

Bong’s skill in shooting, staging, and composition seems effortless. Neither as academic as Ozon or as nervous as Ly, his deliberate style makes every sequence build to a neat point. The contrast between the Park house, perched high on a hill, and the Kims’ basement apartment, is echoed in vertical camera movements that carry us up and down through locales. (Here, in more instances than one, the poor live underground.) Parasite‘s opening camera setup, a view of the street through the Kims’ window, recurs at various points to mark stages of the action. Here nighttime violence erupts in the street outside.

The Kims’ barred view contrasts with the spacious picture window at the Park mansion. Fussy as ever, Bong places a comparable shot of the Kim window at the very end.

Bong plants significant motifs through the film. He forgets nothing. Cub scouts, Morse code, peach allergies, and the smell of poverty pay off in comedy while supplying thematic resonance. The parallels between the married couples are enhanced by the introduction of another husband and wife who have launched their own desperate scheme. The climax, an orgy of rich folks’ complacency, brings all together in a shocking but not ultimately surprising confrontation.

I had almost called this entry “The well-made movie,” indicating not only my praise for the films but also their kinship with the dramatic tradition of the “well-made play” (pièce bien faite). That was one powerful set of principles for plot-building. If you construe that form narrowly (as the Wikipedia entry does), these films don’t completely fit it. I think that Ibsen, Shaw, and those who followed owe more to that form than is generally admitted.

In any case, the impulse toward tight construction, full motivation of characters’ actions (usually guided by a goal), and a rising arc of conflict leading to a decisive climax–these design features, so manifest in the well-made play, have carried over to the cinema since the rise of the feature film in the 1910s.

Today’s films have a look and feel that seem of our moment, but their underlying “engineering” principles are surprisingly indebted to a long-running tradition. Those principles can be deployed, revised, and reversed in a great many ways–as these three films show.

We thank Alan Franey, PoChu Auyeung, Jenny Lee Craig, Mikaela Joy Asfour, and their colleagues at VIFF for all their kind assistance. Thanks as well to Bob Davis, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Tom Charity for invigorating conversations about movies.

For more on the general principles of “classical” construction, see this entry on The Wolf of Wall Street. In our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema Kristin traces some literary and dramatic sources of the format.

On the “free-camera” shooting style, see our blog entry on Toni Erdmann (viewed at VIFF back in 2016). We discuss the emergence of the technique in Chapter 25 of the fourth edition of Film History: An Introduction.

By the Grace of God (2019).