Archive for the 'Directors: Ozu Yasujiro' Category

Good morning from Ozuland

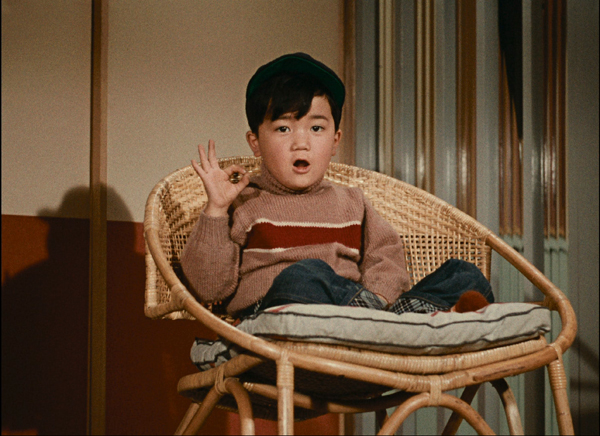

Ohayo (Good Morning, 1959).

DB here:

Ohayo (Good Morning, 1959) was the first Ozu film Criterion released on DVD, back in 2000. The DVD format, launched in 1997, really took off only after The Matrix disc was released in September 1999. So it’s not surprising to find the Ohayo edition quite sparse. No extras, no booklet, just a brief appreciation by Rick Prelinger (which can be read here). One note is charming: “To switch between the menus and the movie, use the menu key on your remote. Use the arrow keys to cycle through menu selections. Press enter/select to activate the selection.”

That early edition wasn’t bad, but now Criterion has given us a brand-new one. It’s derived from a 4K digital restoration and looks like a million bucks. Included with it is a pristine edition of I Was Born, But… (1932), Ozu’s first indisputable masterpiece (though I’d put Tokyo Chorus of 1931 very close), and what scraps remain of A Straightforward Boy (1929). So we have three of Ozu’s kid movies in one neat package, available in standard DVD or Blu-Ray.

That early edition wasn’t bad, but now Criterion has given us a brand-new one. It’s derived from a 4K digital restoration and looks like a million bucks. Included with it is a pristine edition of I Was Born, But… (1932), Ozu’s first indisputable masterpiece (though I’d put Tokyo Chorus of 1931 very close), and what scraps remain of A Straightforward Boy (1929). So we have three of Ozu’s kid movies in one neat package, available in standard DVD or Blu-Ray.

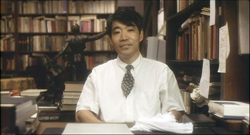

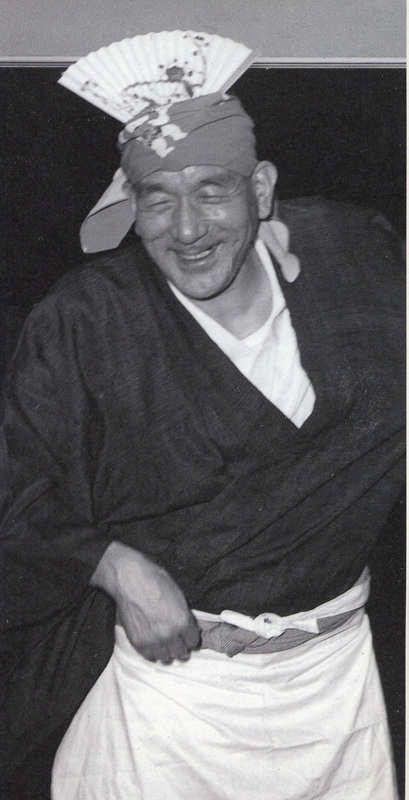

The disc includes a shrewd and funny video essay by Shadowplay‘s David Cairns about Ozu’s humor. I’m there too, in an illustrated interview called “Ozuland.” The title derives from my suggestion that like Bresson, Tati, Mizoguchi, and a few other ambitious directors, Ozu created his own distinct artistic realm. That realm touches recognizable real life at many points, but it has been purified–maybe decanted would be a better word–by means of cinematic form and style.

My enjoyable talk with Elizabeth Pauker ranged on a lot of topics across two hours. We talked about the film’s themes, chiefly the role of language in easing day-to-day human interaction. We discussed Ozu’s distinctive camera positions (yes, there are more than one), his compass-point cutting (360-degree space, 180-degree reverse shots), and his use of adjacent spaces and rhyming compositions. We talked about his narrative strategies too, particularly his oscillation between nuclear-family plots like I Was Born, But… and extended-family ones like Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family (1941, another masterpiece) and Tokyo Story (1953, ditto).

I emphasized both the film’s humor and its status as an unexpectedly experimental work; Ozu was setting himself new problems. How do you treat a neighborhood as an extended family? How do you shoot families living jammed together? How do you accentuate comic misunderstandings, and create gags through composition and color?

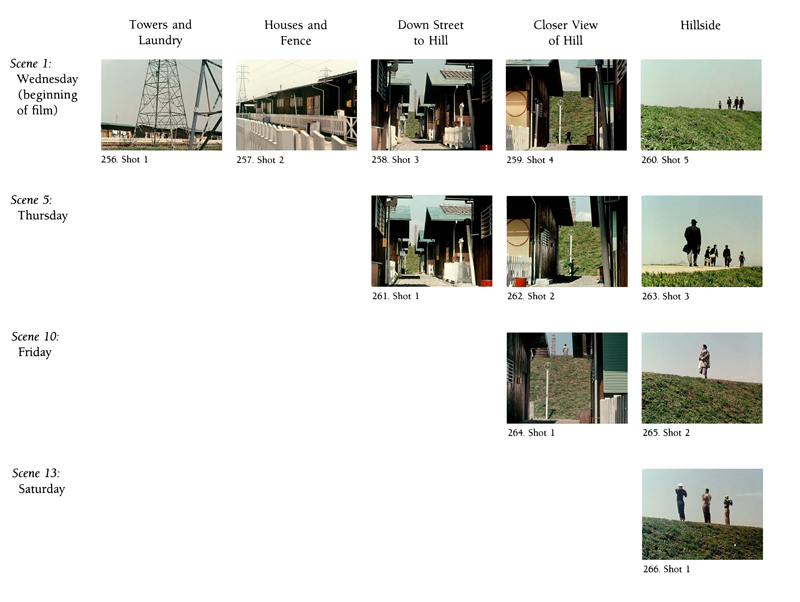

And how do you structure a film around a landscape, days of the week, and neighborhood routines? Ozu’s answer: Through echoic camera positions and compositions. Here’s an anatomy, showing the first four days’ scene openings.

Not all of our conversation could be included in the final cut, of course. For more on these and other matters, you can download my book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema. (The pattern shown above completes itself on p. 353.)

The title of that book resonates in a couple of ways. Most obviously it’s meant to show that a systematic approach to form, style, and theme (the stuff of a poetics of any artform) can illuminate what Ozu’s up to. The title also has personal meaning, because it was Ozu who taught me just how deeply cinematic patterning could penetrate the texture of a movie. Without sacrificing any emotional power, Ozu created films that are marvels of organization, from large-scale story construction to the smallest detail of image and sound.

I remember distinctly when I realized the grain of this work. One night back in the mid-’70s, Kristin, Ed Branigan, and I were watching Ohayo for the first time, on a 16mm New Yorker print. We came to a simple transitional passage and we all gasped. I dove back to the projector and ran the cut backward and forward again.

Apart from shifting us to a new space, as required by the plot, and apart from giving us two exquisite compositions, Ozu added a grace note: the red accent that appears in the same area of the two shots, linking shirt and lampshade. This discovery led Kristin and me to formulate the idea of the “graphic match,” a term for what happens when patterns of line or mass or color coincide from shot to shot.

Some directors, from Lubitsch to Brakhage, had employed graphic matches. Eisenstein had formulated the idea theoretically. But Ozu gave us a demo en passant, in the course of just “following his story.” His match isn’t necessary for the action, but like a rhyme in a narrative poem or a decorative trill in an operatic aria, it adds a sparkle to the moment.

By rewarding minute attention, Ozu made me realize that even ordinary movies teem with pictorial possibilities. There’s potentially so much going on within any shot or cut that scrutiny is often worth your time. True, studying Ozu makes most filmmakers look wasteful. They miss opportunities to enrich all the dimensions of cinema they present, to load every rift with ore.

But if we want to know how films work and work on us, we need to make the effort of looking closely. You’ll almost always find something interesting. When I consulted several books on 1910s directors like DeMille and Taylor, I found that nobody talked about things that popped out at me. As Yogi Berra said, “You can observe a lot by watching.”

Just how cunning was this guy? The more I looked, the more I began to hallucinate that he had made his movies just for me. When he returned to a scene’s master shot, I found that he had cunningly shifted the framing a little, or rearranged tiny elements of the set (often a beer bottle). He must have known I’d take frame enlargements (in that analog age) to check one image against another. I’d notice that in what seemed a perfectly orthodox reverse-angle sequence, things in the background had been slightly shifted to create a variant composition. That red lamp in Ohayo appears teasingly in the distance, out of focus, when other things are going on. Then you have the fact that people in these films like to keep their drinks at the same level of fill, no matter how big the glasses are or how close they are to the camera. Color seems to have inspired him to try these tricks, as in his first color film Equinox Flower (1958):

As with the shirt and the lampshade, there seemed to be Easter Eggs designed not just for my “critical method” but for me, the obsessive analyst. Why? Why would a grown man put these in his movies?

For fun. This tendency isn’t the punishing pursuit of structure at all costs we find in, say, Peter Greenaway. It’s the realization that you can play with patterning cinematic techniques, using them to accessorize your plot, the way musical motifs deepen the dialogue of an opera. And so what if nobody much notices? As I tell my skeptical students: If you thought of it, you’d do it too, just to get away with it.

Ohayo has another of my favorite examples. Throughout the film, the power lines near the neighborhood become a pictorial motif. At one point, the elderly Mrs.Haraguchi seems to be praying to a tower in the distance.

The film starts with a long shot of the neighborhood, its rooftops and fence and washlines in the distance, all dominated by a tower. The film ends with a shot of wash on a line, paying off the gag of the boy who constantly shits his underwear. But the angle of the shot constitutes a reverse angle of the very first shot, since the towers are now in the distance.

Given Ozu’s penchant for 180-degree shifts, and the rigorous patterning of his transitional spaces in the film, I stubbornly, maybe foolishly, maintain that he found this a neat way to give spatial closure to his movie, independent of the underpants gag in the foreground.

Ozu provided me bonus materials in his movies. Some are perhaps visible only to someone as persnickety as he was. And maybe they don’t matter. Ozu gives us so much to enjoy that to ask for more would be churlish. Yet he gives us that more without our asking. His films are generous to their characters and to us, but also to the art of cinema. His absurdly “restricted” approach opened onto vistas of possibility that promise more enjoyment than we have a right to expect.

He had an engineer’s mind, a painter’s eye, and a novelist’s human empathy. And he accomplished it all within one of the most flagrantly capitalistic film industries, which populated Ozuland with stars and stories. Taken all in all, I bet he’s the greatest filmmaker who ever lived.

Thanks to Elizabeth Pauker, who produced “Ozuland,” and as ever Peter Becker and Kim Hendrickson. They have done themselves and Criterion proud with this wonderful package.

The fussbudget in me can’t resist correcting something that comes up in the promotional materials and in some reviews. Ohayo wasn’t filmed in Technicolor. Ozu used what was called “Agfa-Shochikucolor.” I believe that’s just Agfa film with Shochiku adding its brand name, the way “Metrocolor” was MGM’s Eastmancolor. Why Agfa? Ozu explains: “Red turns out magnificently on Agfa film.”

I supplied a feature-length commentary for another Criterion trip to Ozuland, An Autumn Afternoon (1962). If you decide to download Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, be patient. It’s a big file. Lots of pictures.

Ohayo (Good Morning).

P.S. 30 May: An extract from my interview, focusing of course on farts, is on Criterion’s YouTube channel.

Action and essence: Kurosawa’s SANSHIRO SUGATA on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Our contributions to FilmStruck’s Criterion Channel continue. Last month brought Jeff Smith’s analysis of musical motifs in Foreign Correspondent and his celebration of the skill of Alfred Newman, supplemented by a blog entry here. This month it’s my turn, taking on Kurosawa’s Sanshiro Sugata (1943; all Japanese names hereafter in Western order, family name last). My presentation is here, if you are a FilmStruck subscriber. A bit of it is available to all at the Criterion site. Today’s entry fleshes that out with some contextual background.

If the streaming version of Observations on Film Art is a bit like a bonus material on a DVD, think of these blog entries as liner notes with clips. This format allows us to tackle the films from an angle not covered in our videos. We’re sorry that not all of our readers can access the Criterion Channel. But if these entries inspire you to go back to the films in whatever form you can find them, that would be all to the good.

Conquering the self

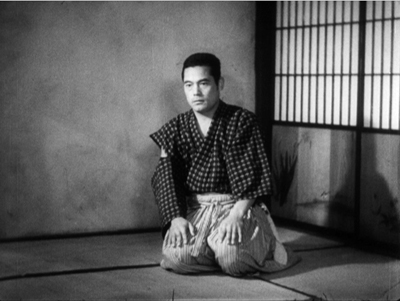

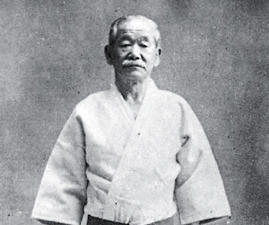

Sanshiro is a film à clef, using martial arts to promote a nationalistic cultural pride. The character of Sanshiro was based on Shiro Saigo (above), who was one of the first pupils of the founder of judo, Jigoro Kano. (In the film, Kano is called Yano, below.) Kano learned the traditional fighting technique called jujutsu (aka jujitsu). Like jujutsu, judo involves grappling, locking, and throwing, and it deploys the opponent’s force against him (or her). But Kano tried to refine the art, eliminating some of the harsher techniques, like biting and kicking, and aiming for maximum efficiency of energy.

By treating judo as a sport and encouraging sparring and public matches, Kano led judo to prominence. His pupils defeated jujutsu challengers. In 1885-1886 matches against Tokyo police champions, Kato’s star pupil Saigo proved judo’s prowess.

In the hands of Kano and Saigo, unarmed fighting techniques were turned to spiritual ends. Ju-jutsu, “flexible technique” was replaced by ju-do, “the path of flexibility”—a devotion to a way of life rather than mere mastery of grips and throws. This distinction is enacted in the film, when Sanshiro, having learned enough technique to bully people with abandon, must learn to master himself.

Judo’s emphasis on spiritual seeking fitted an ideology that emerged in the Meiji period (1868—1912). Japan’s elite was bent on incorporating Western technology and social institutions while maintaining, or rather constructing, a distinct national identity. Accordingly, jujutsu, whose origin lay in Chinese boxing, came into disfavor as part of “feudal” traditions. With young people becoming entranced by Western sports like boxing and wrestling, the government encouraged the development of judo as both modern and uniquely Japanese. As often happened, these “inherently Japanese” cultural forms were of recent invention.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

Kano became a public figure and oversaw the introduction of judo into the public school system in 1908. At the same time his pupil Saigo featured in popular culture as a hero of novels, often as the quasi-mythical Sanshiro Sugata. By then, judo was well established as recreation. And by 1943, when Kurosawa made his film, he was at pains to show judo as the progressive force replacing old-fashioned jujutsu.

There’s another dimension to the story. John Dower has pointed out that imperial wartime propaganda tended to emphasize not triumph over the enemy but the need to purify the self. Accordingly, judo’s victory in the social sphere parallels Sanshiro’s conquest of his anger and egotism.

In the film, Sanshiro comes to Tokyo in 1882, the year Kano actually founded his school. After training, both physical and spiritual, the young man proceeds to defeat the surly jujutsu master Monma. Bristling with youth and vigor, Sanshiro then comes to represent a rising generation capable of surpassing its elders. The next fight references Saigo’s most famous combat during the 1886 police tournament. He must defeat the kindly jujitsu master Murai. But he is attracted to Murai’s daughter Sayo, and so it pains him to trounce her father. But Murai acknowledges judo’s superiority and easily forgives Sanshiro. Judo, he says, awakens his senses.

Most intently, Sanshiro’s purity of spirit clashes with the foppish, Europeanized Higaki, who exploits judo for aggression and self-aggrandizement. Their big fight comes on a wind-swept hillside, perhaps a reference to Saigo’s signature technique yama-arashi (“mountain storm”). The polarity Japanese/ Western would become even stronger in the film’s sequel, Sanshiro Sugata II (1945), in which Sanshiro must fight an American boxer. But from fight to fight, Sanshiro gains greater and greater self-possession, so that in the climactic combat, he can spare time to stare at clouds and envision lotus blossoms.

The film’s plot reverses Saigo’s actual life course: He became a street brawler after he won his tournament victories. More basically, Sanshiro Sugata goes beyond its historical sources and political program, as ambitious films tend to do. Nationalistic messages appropriate to wartime are transformed, reworked—”cinematized”—through Kurosawa’s remarkably dynamic approach to film style.

A resumé film?

Sanshiro is a young man’s first film. Kurosawa started on it when he was thirty-two (within my magic-number deadline). In the Criterion Channel video, I treat the movie as an occasion for an ambitious director to display his versatility—a sort of resumé film, as we’d say nowadays, and maybe a little showoffish.

He was ready for the project. He had a busy several years as an assistant director and screenwriter at the fast-moving Toho studios. He worked on twenty-eight dramas and comedies between 1936 and 1942. When he read Sanshiro’s source novel upon publication, he urged Toho to buy it, and he plunged into his project with fervor.

Like other young directors in Japan, he was well aware of developments abroad. His autobiography records seeing many imported films, from Broken Blossoms (1919) and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Metropolis (1927) and The Blue Angel (1930). Interestingly, he claims to have seen Storm over Asia (1928), Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher (1928), Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928), and even films by Buñuel and Man Ray. His viewing included Hollywood fare by Ford, Lubitsch, Borzage, Wellman, Sternberg, and others. Indeed, he could have kept up with American cinema right up to Pearl Harbor; prints of Edison the Man (1940), Morocco (1930), and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939) seem to have been playing in Tokyo in late 1941. Then all American films were banned.

So he was a cinephile director, perhaps not quite as passionate as Ozu, but a young man who looked and learned. Like most Japanese directors, he had mastered Hollywood continuity staging and cutting. I’ve argued elsewhere that many of his contemporaries were bolder stylists than the Americans. Whether it’s a matter of long takes, camera movements, rapid cutting, or subtle transitions—the Japanese found their own striking innovations.

Ozu’s distinctive 360-degree staging space, low camera height, and play with graphic editing constitute an extreme example of Japanese pictorial invention, but he wasn’t alone. Take this passage from Naruse’s Street without End (1934). The heroine has left her husband’s hospital bed after denouncing him, his mother, and his sister for selfishness. Servants and family rush past her; he may be dying. She hesitates in the corridor. Should she return?

The pattern of cuts and frame entrances accentuates her uncertainty—taking a step, and halting—while the clashing directions in which she moves (right, left, right) have a Soviet-montage flavor. So do the blank frames at the start of every shot, since we have no idea of where we are in the corridor, or where she is, until she thrusts into the frame. And we don’t know whether she chooses to return or not; the geometrical cutting expresses her hesitation.

This geometrical approach to editing is one of the characteristics of Sanshiro I discuss in the video entry. You see it near the start, when alternating single shots of Yano, back to the river, are intercut with slow tracking shots across Monma and his truculent students. To push the pattern further, the tracking shots alternate—first in one direction, then another. Like two rhyming lines in poetry, each of these cinematic couplets brackets one futile attack on Yano after another. Later fight scenes will get more complicated, but display no less rigorous a patterning. And the purpose is always to add to the tension and excitement of the combat.

Another sort of pattern we find in Sanshiro is simpler, but Kurosawa works some nifty variations on it. It’s also somewhat geometrical, but it serves mostly to accentuate a moment of stillness. This is the axial cut, the shot change that moves in or back along the axis of the camera lens. The effect is of sudden enlargement or de-enlargement, a popping out toward the viewer or a sudden withdrawal. Like most directors, Kurosawa uses the axial cut to enlarge something–here, Sayo’s act of praying for her father at a temple.

When the axial cut is justified as a character’s viewpoint, it has the effect of signaling a sharp narrowing of attention. This happens here, when we realize in the voice-off remark (“How beautiful”) and a fourth shot that Yano and Sanshiro have come upon her. That exemplifies an axial cut that moves backward rather than inward.

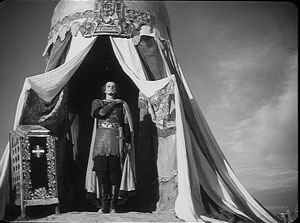

I discussed Kurosawa’s fondness for axial cuts years ago, but it’s interesting to see their origins here. They’re present from the earliest years of cinema, but Kurosawa, again like the Russians, used them expressively. Most uses in Hollywood consist of just two shots, a long shot and then a closer one on the camera axis. But the Soviets, perhaps starting with Eisenstein, multiplied the number of shots and made them fairly brief, so the effect is of a person or object punching out at the viewer. Eisenstein uses the device throughout his silent films, but in both Alexander Nevsky and the two parts of Ivan the Terrible, he develops the device in a very virtuoso manner. Here’s Ivan, standing above the battlefield.

Eisenstein adds to the popout effect by cheating Ivan’s position between shots, so he jumps forward out of his tent.

I’ve found some axial cuts in Japanese films before Kurosawa started directing. One of the most “Kurosawa-ish” comes in a minor 1939 Nikkatsu swordplay film called Faithful Servant Naosuke (Chuboku Naosuke). Again, the cut-ins emphasize a poised moment.

Even if Kurosawa didn’t invent the technique, he made it more prominent and percussive in Sanshiro. It makes the pauses within combat as staccato as the action of fighting. I spend some time in the video talking about how this all works in particular scenes.

Kurosawa’s next film, The Most Beautiful (1944), itself a real beaut, uses the technique quite differently, mainly for tension. His later films continue to explore its possibilities. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2 (1945) resorts to the device to express our hero’s lingering departure for the big duel. He trots toward us, and each time he pauses to look back, Sayo bows.

Today’s filmmaker would probably pull us back with a tracking or crane shot, but by relying on editing Kurosawa gives us his typical crisp geometrical patterning. The abrupt cuts underscore Sanjuro’s realization that he may not return from this life-or-death confrontation. Sanshiro Sugata Part 2, along with the first film and The Most Beautiful, is available from Criterion, as a disc and on FilmStruck streaming.

My streaming presentation discusses other cinematic strategies Kurosawa employs, but these remarks should give you a sense of just how energetically creative he’s being in his first film. It’s a very flashy item, and it looks far into the future. Decades of kung-fu films have been based on dueling dojos, rival fighting methods, and escalating challenges. In addition, Kurosawa’s technique, moving lightly under the weight of an official message, seems very modern.

Youthful, too. As he told Donald Richie, “I really make my films for people in their twenties.”

The information about the history of judo comes from Gabrielle and Roland Habersetzer, Encyclopédie des arts martiaux d’extrême orient (Amphora, 2000), 265-268, 300-301, 549, and 765. Kurosawa lists films he saw in his youth in Something Like an Autobiography, trans. Audie Bock (Knopf, 1982), 73-74. John Dower’s discussion of Japanese propaganda is in War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (Pantheon, 1987). The closing quotation comes from a 1962 conversation reprinted in Akira Kurosawa Interviews, ed. Bert Cardullo (University of Mississippi Press, 2008), 8. Thanks to Hiroshi Komatsu for information about Faithful Servant Naosuke.

Street without End is available in the Criterion Eclipse collection Silent Naruse. If you don’t have this set, get it pronto.

Informative books about Kurosawa and Sanshiro include Donald Richie, The Films of Akira Kurosawa third ed. (University of California Press, 1999); Stephen Prince, The Warrior’s Camera: The Cinema of Akira Kurosawa, rev. and exp. ed (Princeton University Press, 1991); and Stuart Galbraith IV, The Emperor and the Wolf: The Lives and Films of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune (Faber, 2001). Especially revealing about Kurosawa’s production methods in his later films is Teruyo Nogami, Waiting on the Weather: Making Movies with Akira Kurosawa, trans. Juliet Winters Carpenter (Stone Bridge Press, 2006). On the “spiritist” trend in government policy in the media of the period, see Peter B. High’s magisterial The Imperial Screen: Japanese Film Culture in the Fifteen Years’ War, 1931-1945 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2003), Chapter 6.

For more on axial cutting in Soviet and modern films, and The Simpsons, go here. I discuss Eisenstein’s axial cutting in The Cinema of Eisenstein, Chapters 2, 4, and 6. On Ozu’s characteristic staging, shooting, and editing system, see my Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available for download from the University of Michigan Library site. The full PDF takes a while to download, but you can get access quickly by clicking on “List of all pages.” I discuss other aspects of the tradition from which Kurosawa comes in Poetics of Cinema, Chapters 12 and 13. See also the Kurosawa, Ozu, Mizoguchi, and Shimizu entries on this site.

Kim Hendrickson, Criterion producer, and Grant Delin, DP, filming DB from a closet.

Cinematic storytelling: A podcast on narrative

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013).

DB here:

Michael Neelsen is a filmmaker and consultant based here in Madison. In a discussion on ReelFanatics Michael and I consider some ideas about cinematic storytelling. My allergies gave me some Clintonesque hoarseness, and there are some things I’d rephrase better if I were writing them down, but maybe you’ll find something of interest there.

A couple of blog entries are relevant to our conversation: one on The Wolf of Wall Street and another on American Hustle. The first of these links to a general analysis of film narrative originally published in Poetics of Cinema and available elsewhere on the site. Our discussion of suspense and surprise harks back to other entries too, in particular those about Hitchcock and the bomb under the table (here and here). In the podcast I mention the Godard film Adieu au langage as well because I was then working on this blog entry.

You can also visit Michael’s company site StoryFirst.

Thanks to Michael for an enjoyable discussion, and for sharing it via podcast.

Watch again! Look well! Look! (For Ozu)

Okada Mariko and Tsukasa Yoko with Ozu, on the set of Late Autumn (1960).

DB here:

Ozu was born on 12 December (in 1903) and died on 12 December (in 1963). He has been gone fifty years, yet his films are as fresh, inviting, funny, and moving as ever. As chance would have it, my book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema was published twenty-five years ago. Two events of the past few months have brought me back to him.

First, my biannual summer course in Antwerp, held under the auspices of the Flemish Film Foundation, was focused on him. As I’ve explained in earlier years (2011, 2009, 2007), at this Summer Movie Camp, across a week we immerse ourselves in films and wrap lectures around them. It was a joy to see a dozen of his films, mostly in good 35mm prints. Our sessions provided an occasion for me to rethink some things I said in the book, as well as to notice more about how these dazzling, apparently simple films work and work upon us. I learned as well from the comments and questions of many of the participants. The whole experience didn’t shift my opinion, stated on an earlier Ozu anniversary, that “no director has come closer to perfection.”

The second occasion: Two enterprising Ozuphiles have just published a collection of essays, Ozu à présent (Paris: G3j publishers). Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin have worked very hard for several years gathering pieces from filmmakers (Erice, Kurosawa Kyoshi) and critics like Hasumi, Frodon, Rosenbaum, and Jun Furita Hirose. Many other contributors have previously written on the director: Basile Doganis (Le Silence dans le cinéma d’Ozu), Benjamin Thomas (essays for Positif), and Clélia Zernik (Perception-cinéma). As for the editors, Diane has books on Sokurov and Kurosawa Kyoshi, while Mathias has written on Oliveira and art history generally. The entire collection is stimulating and beautifully produced.

The second occasion: Two enterprising Ozuphiles have just published a collection of essays, Ozu à présent (Paris: G3j publishers). Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin have worked very hard for several years gathering pieces from filmmakers (Erice, Kurosawa Kyoshi) and critics like Hasumi, Frodon, Rosenbaum, and Jun Furita Hirose. Many other contributors have previously written on the director: Basile Doganis (Le Silence dans le cinéma d’Ozu), Benjamin Thomas (essays for Positif), and Clélia Zernik (Perception-cinéma). As for the editors, Diane has books on Sokurov and Kurosawa Kyoshi, while Mathias has written on Oliveira and art history generally. The entire collection is stimulating and beautifully produced.

As the title indicates, it’s centrally about Ozu’s continuing influence on modern cinema. I was asked to contribute a preface, which Diane and Mathias have kindly allowed me to reproduce below in revised form. I’m now chiefly aware of what I neglected (no mention of Wenders’ Tokyo-Ga) and didn’t know about (for instance, Claire Denis’ admiration for Ozu). These and many other matters are taken up by the book’s contributors. But I think my piece may be of interest as a small update of my Ozu book.

In 1988, most of Ozu’s surviving films weren’t easy to access. Things have changed. And since I wrote the essay, virtually all the extant work has appeared on DVD, on cable television, and in the Criterion collection on Hulu Plus. As his films become more and more familiar, we can expect ever-greater acknowledgment of his centrality. Already, the 2012 Sight and Sound poll of critics put Tokyo Story just below Vertigo and Citizen Kane; the directors’ poll put it at the very top.

Why not watch an Ozu film today? Go beyond Tokyo Story, fine as it is, to Early Summer, Passing Fancy, Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family, An Autumn Afternoon, The Only Son, The Flavor of Green Tea over Rice, Ohayo, Diary of a Tenement Gentleman, What Did the Lady Forget?, Dragnet Girl, Where Now Are the Dreams of Youth?, I Was Born, But… and on and on.

Catching up with Ozu

Ozu is a major presence in today’s international film culture. When I began seeing his work in the early 1970s, about half a dozen Ozu movies were in circulation, and of those only Tokyo Story was known to nonspecialist cinephiles. As late as the 1980s, I had to travel to archives in Europe and the US to see his rarer films. Now even the most obscure early 1930s titles are issued on DVD, and the films have been widely distributed in touring packages. They are screened all over the world, a process lovingly recorded on Twitter. Ozu is better known to a broad public than Mizoguchi Kenji is—an ironic turn of affairs, given that in many countries Mizoguchi gained fame during the 1950s and 1960s, when Ozu was unknown.

Even more famous throughout the west was, of course, Kurosawa Akira. His influence on mainstream cinema has been robust and pervasive. If slow-motion violence has become a convention in American films since Bonnie and Clyde, that is directly traceable to the director of Seven Samurai. The use of very long lenses to cover a scene, common in American cinema of the 1960s and thereafter, owes a great deal to Kurosawa’s strategies in films like I Live in Fear and Red Beard. Editing on the camera axis for visceral impact, a Kurosawa signature technique, has bumped up the visual excitement in many American action pictures.

Ozu has not had such a direct influence. He is much less easy to assimilate. With few exceptions, his signature style has been far less imitated, and it has even been misunderstood. His effect on modern cinema, it seems to me, has been far more oblique, with directors paying him tribute in discreet, sometimes unexpected ways.

Brand Ozu

Ozu wing, Kamakura Cinema World, 1996.

Ozu was careful to mark his uniqueness. He designed his films to be sharply different from those of his contemporaries. His home base, the Shochiku studio, encouraged directors to develop personal styles, and he was allowed to make artistic choices that could only be considered eccentric. At first glance, Ozu’s films may seem to melt into a broader idea of “Japanese artistic culture,” but the more films we see by his colleagues, the more idiosyncratic his works look.

Having allowed Ozu to make such singular films, Shochiku has exacted a reciprocal obligation: his legacy now serves as a trademark for a film studio. For the world at large, Japanese cinema consists of Kurosawa and Toho studios’ Godzilla, Nikkatsu action, and anime. Shochiku had its tradition of modest, humane dramas of working-class and middle-class people, treated with that mixture of humor and tears known as the “Kamata flavor” (after the Tokyo suburb where the studio was located). That tradition was sustained by Ozu and his colleagues through the 1950s as a brand identity. The forty-eight Tora-san films (Otoko wa tsurai yo, “It’s Tough to Be a Man”) became what we’d call a frachise for Shochiku from 1969 through 1996.

But as media became globalized, and as merchandising became central to sustaining filmmaking, Shochiku’s product came to seem narrowly local. Accordingly, the firm turned its attention to its most famous employee. Shochiku’s familiar postwar logo, a view of Mount Fuji, had become for westerners part of Ozu’s iconography.

Now Shochiku tried to reclaim its trademark by reminding viewers that he belonged to a bigger family.

For the local market, Shochiku tried a bit of merchandising, such as phone cards with scenes from Ozu movies. More ambitiously, there was Shochiku Kamakura Cinema World, a theme park established in 1995 at a cost of $125 million. It held many attractions devoted to American cinema, and it even allowed customers to visit a movie in the making, but one wing was devoted to Shochiku’s legacy properties, including a replica of a street from the Tora-san series. There were as well Ozu memorabilia, including a three-dimensional tableau of an effigy Ozu directing a scene in Tokyo Story. The adjacent vitrine housed a reconstruction of his work area at home, complete with whisky bottle and bright red rice kettle.

Cinema World closed in 1998, a financial failure. But Shochiku persisted and declared in 2003 that it would host a worldwide celebration of Ozu’s hundredth anniversary. That celebration consisted of a new touring program of 35mm prints of his films, with ancillary ceremonies and festival activities, and several new DVD releases. Shochiku went further and commissioned Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Café Lumière, a film in homage to the great director. For festivals and arthouse cinemas, Hou’s tribute was aimed to recall Ozu’s greatness and, by association, Shochiku’s place in film history.

As directors have sought to retain the Kamata flavor in later decades, we find hints and traces of Ozu as well. A film like 119: Quiet Days of the Firemen (1994), in which middle-aged men in a small village fantasize about romance with a young researcher, might bring to mind the overactive imaginations of the grown-up schoolboys of Late Autumn (1960). Kore-eda Hirokazu’s Still Walking (Aruitemo aruitemo, 2008) is a family drama made in full awareness of the Ozu tradition. Not surprisingly, Yamada Yoji, impresario of Tora-san, has invoked the Shochiku tradition in several productions (notably Kabei: Our Mother, 2008, and Ototo, 2010). At the start of 2013 Yamada, at 81 years of age, released an updated remake of Tokyo Story.

Ozu comes to America

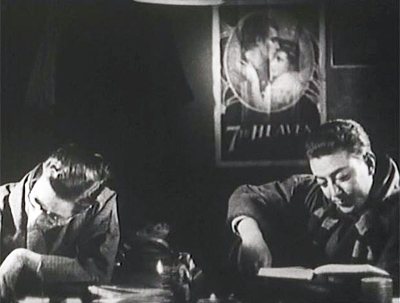

Days of Youth (1929).

Since at least the early 1920s, the Japanese cinema has responding to the American cinema. During the classic period, American films did not dominate the Japanese market, as they did in many other countries, but filmmakers were nevertheless acutely conscious of Hollywood. In particular, the founding of Shochiku in 1920, with a self-consciously modernizing orientation under Kido Shiro, created a ferment that changed Japanese cinema forever.

Like other Kamata/ Ofuna directors, Ozu relied crucially on American cinema. There are visual citations (the Seventh Heaven poster in Days of Youth), lines of dialogue about Gary Cooper and Katharine Hepburn, borrowed gags (from A Sailor-Made Man in Days of Youth), and even an extract from If I Had a Million in Woman of Tokyo. More deeply, his early films absorbed the analytical editing of 1920s Hollywood. He broke every scene into a stream of precise, slightly varied bits of information in the manner of Ernst Lubitsch and Harold Lloyd.

Ozu paid American cinema a deeper tribute. Having grasped that system of axis-of-action continuity that Hollywood had forged from the late 1910s, he created his own system as an alternative. Instead of a 180-degree organization of space, he proposed a 360-degree one. This allowed him to absorb the Americans’ innovations and yet give them a new force. Cuts would use eyelines, shoulders, and character orientation, but would often show characters looking in the same direction, their figures and faces matched pictorially from shot to shot.

A cut on movement could be made by crossing what American directors called “the line.”

Further, Ozu realized that the establishing shot, that depiction of the overall space of the action, could be prolonged and split into several shots. The result was a suite of changing spaces that could be unified by shape, texture, light, or even analogy (one window/ another window). These transitional sequences substitute for fades and dissolves, turning ordinary locales into something at once evocative and rigorous.

All of these transformations of Hollywood’s stylistic schemata are rendered more palpable by a single, simple choice that is more single-minded than anything to be found in Hollywood: The camera is typically placed lower than its subject. This constant framing choice acts as a sort of basso continuo for the melodic variations Ozu will work on two-dimensional composition and three-dimensional staging.

This entire stylistic machine might seem to be aimed wholly at working out its own intricate patterns, and indeed to some extent that is what happens. The aficionado can appreciate the refinements, the theme-and-variants structuring, created by Ozu’s cinematic narration. There’s playfulness as well; how funny, he seems to say, that editing and composition can play hide-go-seek with quilts and ketchup bottles. Just as important, all these techniques nudge us to arouse our attention—to the possibilities of cinema, but also to the shapes and surfaces of the world as they change. Alongside the characters’ drama is a realm at once stable and ceaselessly shifting; the characters and their drama are subject to the same forces of mutability. Ozu’s modest pyrotechnics activate the world his characters inhabit, subject them and their actions to the same suite of transformations, and have the larger purpose of reawakening us to our world.

Made in USA

As Ozu’s films became known in the west, citation-happy directors of the 1980s took notice. An example is the moment in Stranger Than Paradise (1984, above), when Eddie reads off the list of horses running in the second race: “Indian Giver, Face the Music, Inside Dope, Off the Wall, Cat Fight, Late Spring, Passing Fancy, and Tokyo Story.” After a pause, Eddie says to bet on Tokyo Story. We know from Jarmusch’s account of visiting Ozu’s grave that he was a passionate admirer, but his films seem to me to show his debts chiefly in their “minimalist” approach to their action.

More elaborately, Wayne Wang offers a self-conscious homage in Dim Sum (1985). This story of a widow, her brother-in-law, and her daughter transfers an Ozu situation to San Francisco and a Chinese-American community. Should the daughter marry and leave her mother alone? The uncle, who runs a declining bar, urges the girl to do so. The situation, he says, reminds him of “an old Japanese movie” in which a parent urges the child to start a family. As in Ozu, the generations are sometimes captured in “similar-position” (sojikei) compositions.

To the generational split of the Ozu prototype, Wang adds the cultural division between modern America, the daughter’s home, and Hong Kong, home not only to the mother but all the friends in her age group. The generational contrasts would be elaborated upon in Wang’s later Joy Luck Club (1993), which counterpoints the experience of four mothers and four daughters.

Well aware of the Ozu parallels in the plot, Wang elaborates them through some stylistic choices. The film starts with a static thirty-second shot of curtains blowing alongside a sewing machine. The mother comes into the frame, pours tea, takes pills, and starts the machine. The next sequence consists of isolated details—a birdcage, a table.

Only then do we get a placing shot of the street, but it serves here as a transition taking us out of the home (Ozu would probably have included part of the window frame), then to San Francisco Bay and then to a young woman seen from the rear sitting on shore.

No drama is forthcoming–no conversation, not even a voice-over suggesting the young woman’s thoughts. The lyrical capstone of the sequence comes with a nearly abstract shot of the water, perhaps the woman’s point of view, but unaccompanied by language or music.

Wang has given us an imagistic preview of details to be seen later. Not only will we come to recognize the young woman as the daughter Laureen, but we’ll see the household furnishings, street locations, and bridge views at various points in the film.

The rest of the film is not as disjunctive as this opening, and Wang soon settles into the sort of loose, leisurely plotting that characterized independent film of the period. But the objects and cityscapes we see don’t become dramatically significant; they are part of the ambience of the characters, somewhat in the Ozu manner. But neither do they take on the elaborate variations and minute adjustments we find in Ozu’s “hypersituated” objects and recurring locations. Still, of all American directors Wang has most willingly adapted Ozu’s aesthetic to his own personal concerns, while paying homage to a director who was just starting to be appreciated as both storyteller and stylist.

Otherwise, the balance-sheet seems to me virtually empty. Every young American filmmaker seems to have studied Kurosawa, but which of them knows Ozu—or, like Eddie, have bet only on Tokyo Story? Filmmakers elsewhere have been more generous and discerning.

Citation, pastiche, and parody

Hou Hsiao-hsien, no cinephile in his youth, came to admire Ozu later in life, and he used citation in a more thoroughgoing way than Jarmusch had in Stranger than Paradise. Liang Ching, the modern-day protagonist of Good Men, Good Women (1995), leads a sort of parallel life with a Taiwanese woman she’s playing in a film: Chiang Bi-yu, along with her husband, who joined the anti-Japanese resistance on the mainland in 1940. But the parallel is a contrast as well, since Liang is unhappy in her love relationships and seems to lack any sense of social commitment. Her drifting, rather lost style of living is counterpointed not only to the courageous and energetic Chiang but also, via a televised movie, to Ozu’s postwar world.

Early in the film, Liang is awakened by the beeping of her fax machine. As she droops at her kitchen table, her television monitor runs the bicycling sequence from Late Spring (1948).

These cheerful shots of Noriko and Hattori on an outing provide yet another contrast to Liang’s brooding torpor about the death of her lover Ah-wei. They also suggest another way to be a heroine, quietly strong and capable of both love and defiance. And the chaste outing we see in Late Spring contrasts sharply with the intense eroticism of the flashback that follows this morning scene, showing Liang and her lover caressing each other before a mirror. Unlike Ozu’s couple, they need a narcissistic magnification of their passion. If Good Men, Good Women’s overall plot condemns the Japanese for their army’s invasion of China, Hou from the start reminds the audience of another Japan, one that after the war became, at least in Ozu’s hands, a place of humane feeling. This is no one-off joke as in Jarmusch’s citations; the Late Spring extract deepens the thematic reverberations of Hou’s film as whole.

Likewise, instead of the sporadic invocations of Ozu’s style provided by Wayne Wang, the early films of Suo Masayuki show more engagement with the Ozu manner—particularly because they are turned to comic ends. Suo’s first feature, My Brother’s Wife: The Crazy Family (Hentai kazoku: Aniki no yomeson, 1984) was a curiosity: a softcore pornographic film shot in a distinctly Ozuian style. Only in Japan can an erotic film spare the energy to borrow so explicitly from a master of the cinema. While the newly married couple has thumping intercourse upstairs, the husband’s father, sister, and brother sit calmly downstairs, sighing or frowning slightly in response to the gymnastics overhead. One evening the father comes home from a drinking bout and the son, like the son in An Autumn Afternoon, warns him to cut back.

Suo gives us the father sitting alone in an Ozuesque shot, and as his head slumps, Suo cuts to the wife upstairs, rolling her head forward in a similar gesture.

True to the exhaustive geometry of pornography, the brother graduates to sadomasochism, the adolescent son becomes fixated on his sister-in-law, and the young daughter takes up work in a “soapland” parlor. Thus is the Ozu family drama turned upside down, with the father observing everything with a bemused, helpless smile. Suo, who had studied film under Hasumi Shiguéhiko, turned in a well-crafted film that was a virtual parody of the late Ozu style. Of course, by the time he started, Suo was able to study video releases and mimic the Ozu look shot by shot.

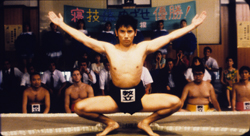

In Suo’s next films, parody turned into pastiche. Fancy Dance (Fanshi dansu, 1989) and Sumo Do, Sumo Don’t (Shiko funjatta, 1992) display a fanatically precise understanding of Ozu’s unique use of space. Suo adheres to the low camera height, builds scenes out of slightly overlapping zones, and avoids camera movement. He indulges in the master’s penchant for head-on shots that can be matched graphically across a cut, leaving us to notice the variations of color and texture within remarkably similar compositions.

Suo will even follow Ozu’s penchant for graphically matched movement across cuts. His sumo opponents spread their arms in a continuous movement as smooth as that displayed by Ozu’s drinking buddies.

Westerners often ignore Ozu’s penchant for social comedy in the Lubitsch vein, but Suo’s films happily explore this dimension. American and European filmmakers seem aware only of Ozu’s postwar films, but Suo the cinephile grasped that the 1930s college comedies offered fertile resources. Suo’s youth pictures show young people giving up modern popular culture in favor of Japanese traditions that are so old that they become fashionably retro. In Sumo Do..., a ragged college sumo team discovers that the sport turns them from slackers into adepts. In Fancy Dance, a talentless rocker, forced to live in the Buddhist monastery he has inherited, eventually learns that Zen can be cool.

Shall We Dance? (1996) modifies the Ozu look into something more generically Kamata-toned, but Suo still shows traces of the master’s rigor. For example, the first time that the camera moves is when the bored executive takes his first tentative lesson in ballroom dance. The film’s social critique is not as harsh as that in Ozu’s 1930s work, but it does dramatize the stifling limits put on both the salaryman and his family.

Just-noticeable differences

Five Dedicated to Ozu.

The two most famous Ozu homages, both from his anniversary year of 2003, are more puzzling. For neither Hou’s Café Lumière nor Abbas Kiarostami’s Five Dedicated to Ozu can be easily categorized as citation, assimilation, or pastiche. How have these two masters paid tribute to him?

Café Lumiere could easily be simply a Hou production that happened to be in Japan. It’s imbued with his characteristic narrative maneuvers, themes, and style. Even the cutaway long shots of trains, recalling some of Ozu’s urban iconography, would be perfectly at home in Hou’s work, which has made memorable use of trains (Summer at Grandfather’s, 1984; Dust in the Wind, 1987).

Likewise, Kiarostami’s Five Dedicated to Ozu might seem to take Ozu as a pretext for a foray into “pure cinema” in the manner of Shirin (2008) or the video installations Sleepers (2001) and Ten Minutes Older (2001). Unlike Hou, though, Kiarostami didn’t conceive his film as a tribute; only after having premiered it at Cannes was he invited to attach it to the fall 2003 Ozu centenary. As a result, he changed the title from the original one, Five. In explanation, Kiarostami claims that the protracted long shots in the first four episodes are akin to Ozu’s style:

His long shots are everlasting and respectful. The interactions between people happen in the long shots and this is the respect that I believe Ozu felt for his audience . . . In his mise-en-scène he respected the rights of the audience as an intelligent audience. His films were not usually very technical, which would make them appear nervous and melodramatic in the manner of today’s montage facilities.

Although Kiarostami’s statement isn’t perfectly clear in translation, he seems to suggest that Ozu favored lengthy and distant shots and avoided editing—a common misconception about the director. There is, in short, something of a mismatch between each of these directors’ “Ozu films” and the oeuvre of Ozu.

Café Lumière has recourse to one of Hou’s favorite maneuvers, casting rising pop-music stars in his films. Hitoto Yo, who had her first hit “Morai-Naki” in 2002, became his lead performer. This was a shrewd marketing move, as she is of both Japanese and Taiwanese ancestry and personifies the “fusion” aspect of Hou’s Shochiku project. Likewise, the male star Asano Tadanobu , an idol of Japanese cinema, has appeared in Thai, Russian, and even American films (e.g., Thor, 2011). Asano is also a pop musician and model. These strategic choices would, I think, have been appreciated by Ozu, who designed his scripts around Shochiku’s biggest stars and was not above “product placement” of favorite alcohol brands in his bar settings. Just as important, as with his Taiwanese films, Hou puts his young stars into a rigorously paced, controlled mise-en-scène—one owing little to Ozu technically, but a great deal to his model of incessant attention.

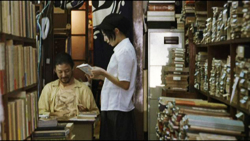

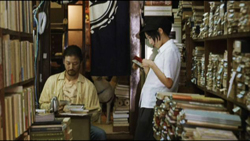

At one level Café Lumière is a family drama, a little reminiscent of Ozu’s Tokyo Twilight (1958). While visiting her parents, Yoko tells her mother she is pregnant and has no intention of marrying the child’s Taiwanese father. Her family must come to terms with this, and the situation is handled with even more subdued reactions than we would find in Ozu. At another level, the film is about a search for sound. Yoko meets the book dealer Hajime while she is researching a Tawainese-Japanese composer from the 1930s. For his part, Hajime has the hobby of recording the sound of Tokyo subways, trains, and trams. Ozu leaves it to the viewer to notice the subtle attenuation of his music and noise effects, while Hou announces and thematizes these components as part of his cross-cultural drama.

Hou, like Ozu, is a director of “just-noticeable differences,” the details that change slightly across a shot or scene. The first encounter that we see between Yoko and Hajime is a lengthy long-lens two-shot. Yoko pays for books that Hajime has kept for her, and as the couple move slightly, we can glimpse Hajime’s dog in the background, a bit of characterization for him. She moves aside to let us see it, then shifts back to allow us to concentrate on their dialogue.

This dynamic blocking and revealing of elements, characteristic of Hou’s staging, shapes the space as an unfolding spectacle, with new facets for us to discover. On the file cabinet on the right, splashes of light from the street outside come to fill the spot Yoko had occupied.

As the couple talk and listen to extracts of the composer’s piano music, illumination ripples over the shop interior, a reminder of the city turmoil that lies outside this cramped sanctuary, and Yoko leans back into the light.

The rest of the film will vary the locations to which we return—a coffee bar, Yoko’s apartment—with slight differences measuring the time that has passed. Likewise, the minimal, barely-started romance, crystallized in meetings over coffee, is nuanced by ever-changing patterns of light. We must watch the people, their gestures and slight displacements, as well as the space that they inhabit and the changing levels of illumination. We must attend to both the drama and its aura, both the café and the lumière.

Kiarostami calls Five Dedicated to Ozu “a real experimental film,” and he’s right: It could as easily have been called Five Dedicated to Warhol. Like American Structural Film, Five… asks us to sink into a fixed frame showing landscape views, and to concentrate on minutiae. A piece of wood, caught on the waves lapping to shore, breaks in two. One piece stays on the sand, while the other is carried out to sea. People stride or stroll along the sea front. Unidentifiable objects at the water’s edge shift uneasily and gradually become recognizable as dogs; but soon they dissolve into spindly black skeletons as the image brightens into dazzling abstraction. Ducks stroll through the shot, each one making a padding sound. Finally, the moon is reflected in a pond at night; the reflections quiver, broken by thunderclaps. For long periods the image is black and we must listen to birds, frogs, and some mysterious creatures.

“I think,” Kiarostami explains, “we should extract the values that are hidden in objects and expose them.” That sensitivity to just-noticeable differences that Hou achieves through the long take and intricate staging, Kiarostami achieves with the cooperation of nature. He is willing to trust to chance, a force that will collaborate with him and invent something he couldn’t conceive. Both filmmakers ask for a patience that most contemporary cinema cannot tolerate. In a general sense, Ozu becomes a model of a possible cinema—not through specific technical choices, as with Wang and Suo, but through an overall effect: a cinema delighting in the textures and weight of our world.

Still, something has been lost. To make us wait and watch today, the director must “gear us down” through long takes and stasis, through deferring, stretching, or purging narrative. Ozu, miraculously, solicits this heightened perception in less strenuous ways, through a cascade of cuts, rapid dialogue, and an engrossing story. The contemplative aspect of his cinema was simply another dimension of a work that incorporated dynamic storytelling. When cinema was newer, it seems, much was possible. Hou and Kiarostami, like Béla Tarr and a few others, have found in a slow pace and minimal drama today’s best analogues to the sharp-edged awareness of the world that came so spontaneously to Ozu in a more industrial mode of production. In a larger sense, though, Ozu and Hou would agree with what Kiarostami claims could be alternate titles for his film: Watch Again! Look Well! or simply Look!

Peter Bosma‘s report on last summer’s Film College can be read here. Thanks as well to Peter for a rare Ozu-related document. I’m grateful as well to Nicola Mazzanti, Gabrielle Claes, Stef Franck, and Bart Versteirt for making my stay in Antwerp so enjoyable, especially including the beer, moules, and frites. Earlier reports on the annual Summer Movie Camp can be read here and here and here.

Once more, thanks to Diane Arnaud and Mathias Lavin for having solicited the essay.

My quotations from Kiarostami come from the interview included in the Kimstim DVD of Five Dedicated to Ozu. On Hou’s staging principles, see Chapter 5 of my Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. I’ve discussed Hou’s staging on this site as well, here and here (with Ozu in the mix). Other entries on Ozu on the site can be found listed on the right. My book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema is available as a free pdf file, with color illustrations, from the University of Michigan. As ever, thanks to Markus Nornes for making the book available in this format.

Finally, some years ago Lorenzo J. Torres Hortelano, author of a book-length study of Late Spring, wrote to tell me that the Noh play performed in Late Spring is Kakitsubata, not the one I had claimed. I found that he was correct, but had no way to change the book’s mention of it. Seeing Late Spring again last summer, I was reminded of Prof. Torres Hortelano’s message and now want to call readers’ attention to my error in the book. Prof. Torres Hortelano is also the author of The Directory of World Cinema: Spain and World Cinema Locations: Madrid. I thank him for the correction.