Archive for the 'Directors: Scorsese' Category

No coincidence, no story

Serendipity.

DB here:

I’ve been thinking about coincidences lately. Watching Hong Kong movies can do that to you.

Hong Kong vs. Hollywood?

Initial D; I Corrupt All Cops.

In Initial D (2005, Andrew Lau Wai-keung and Alan Mak Siu-fai, script by Felix Chong Man-keung), the protagonist Takumi is dazedly in love with the seductive schoolgirl Natsuki. Takumi’s pal Itsuki is out with another girl when he spots Natsuki riding out of a “love hotel” with an older man. Itsuki tells his pal. This leads to a major crisis, in which Takumi’s faith in Natsuki is shaken.

Then there’s I Corrupt All Cops (2009) from the indefatigable writer-director-producer-actor Wong Jing. (Many wish he were far more fatigable.) Unicorn, a corrupt, brutal police officer, has just been savagely beaten by gamblers who once were his allies. He staggers to a street stall and nearly collapses, spitting blood into his congee. Then he glimpses his girlfriend getting out of a rich man’s car. In the next scene, when he visits her apartment, he finds his boss, the even more corrupt cop Lak, in her bed. His realization that he can trust no one pushes him to join the police anti-corruption unit.

True, the coincidences play different roles in the two movies. In Initial D, there might be an innocent explanation for Natsuki’s visit to the hotel. Perhaps Takumi’s friend even mistook another girl for her. So we may be inclined to suspend our judgment and wait for more information about whether she’s actually being unfaithful. In I Corrupt All Cops, Unicorn’s suspicions about his girlfriend’s disloyalty are immediately confirmed; instead of suspense, we get surprise, in the form of the revelation of who her lover is.

But in each case, a major plot movement is triggered by sheer accident. Itsuki wasn’t spying on Natsugi’s assignation; he was trying to talk his date into the love hotel. Unicorn wasn’t suspicious of his girlfriend, he just happened to be across the street when she came home. Each coincidence is also a matter of timing: Had either man come a few minutes later to the location, he wouldn’t have learned the big secret. In retrospect, we are likely to think that the screenplays of Inital D and I Corrupt All Cops are using chance rather than causality to move their action forward.

Granted, Hong Kong films are generally weak in plot construction. Even the lauded films of Wong Kar-wai are built out of casual encounters and unpredictable turns of events. The old Chinese maxim “No coincidence, no story” might seem to give accidental revelations a high place in this cinema. But Hong Kong films aren’t outstanding offenders. When you start to look, you find that films in different traditions are no less committed to coincidence. After all, Rick in Casablanca notices the vast implausibility of what’s just happened: “Of all the gin joints in all the towns in all the world, she walks into mine.”

One precept of Hollywood screenwriting has been that coincidences are permissible when you’re setting up the narrative. Indeed, they’re often necessary: Circumstances have to come together in some way to launch an extended action. A sudden rainstom brings boy and girl together under the same awning, creating the cute meet, and things can build from there.

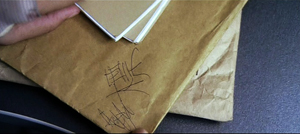

But, the Hollywood wisdom goes, don’t use a coincidence to develop or resolve the plot. Consider another Hong Kong film, Infernal Affairs (2006, directed by Lau and Mak, with script by Chong). Chan the undercover cop has come in from the cold. While officer Lau is out of his office, Chan is poking idly around Lau’s desk. There he finds the envelope on which Chan himself once scribbled a correction.

That envelope was in the hands of the gang that Chan joined. If Lau has that envelope, he must be the triad mole in the police force. This recognition triggers the film’s climax: Chan flees police headquarters and sets out to unmask Lau’s treachery.

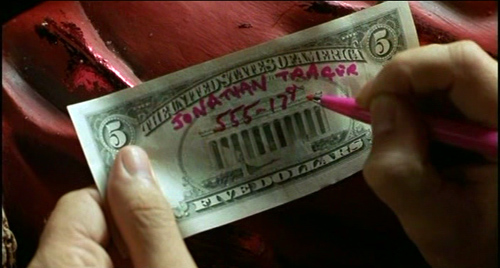

You would think that if Hollywood filmmakers were anxious to avoid such a timely accident, the Infernal Affairs remake known as The Departed (directed by Martin Scorsese, script by William Monahan) would find another way for Billy Costigan to discover that Colin Sullivan is the mole. But no. Billy notices the telltale envelope sticking out from a pile of papers on Sullivan’s desk.

The different ways the two films drive the discovery home to the audience merit a closer look than I can spare here. My point is that the handy coincidence of the police mole leaving this damning clue for his adversary to find is used without apology in the Hollywood movie. And like its counterpart, the scene sets off the movie’s climax. You could even argue that Infernal Affairs supports its revelation a little better. Billy accidentally glimpses the crucial envelope, but Chan is actively browsing Lau’s desk, perhaps because after years spent among triads he doesn’t trust anyone .

So you have to wonder. Maybe filmmakers in many traditions have accepted the Chinese maxim. Moreover, contrivance of this sort doesn’t seem to damage a film’s reputation. (Many critics considered The Departed one of the very best US films of 2006.) More generally, we seldom feel such coincidences to be arbitrary or forced. Maybe screenwriters and directors have found ways to mask the coincidental tenor of such scenes.

As with our earlier Inception entry, we’re in the realm of motivation.

The roots of coincidence

Most story actions result from characters’ choices, purposes, reactions, plans, and the like. These factors create patterns of cause and effect. Chan/Billy didn’t just mosey into Lau/ Colin’s office: He came in because he thought it was safe to break his cover. We accordingly worry for him because we know, as he doesn’t, that he’s far from safe.

Everyone seems agreed that a plot can’t replace all causal connections with a string of coincidences. If everything happens by convenient accident, then we can’t form any expectations about what will happen next. And without expectations, our cognitive and emotional engagement with the story is likely to be slight. Moreover, designing a story packed with coincidences isn’t that hard. Children do it all the time. But most artistic traditions thrive on their constraints. If anything at all can happen to advance or conclude your plot, you’re playing tennis without a net. The interesting challenge for a storyteller in traditional forms is to create a pattern of incidents that arouses our curiosity, builds up suspense, and presents surprises that turn out to be, in retrospect, cunningly prepared for—all the while playing on our emotions.

Yet, and again: No coincidence, no story. Sometimes, the plot’s forward momentum needs encounters and discoveries not planned by the characters. So how can these convenient accidents be made to serve narrative craft?

Well, what is a coincidence anyway? At the least, it’s a matter of converging incidents, as the name implies; but surely it involves more.

I wake up one morning and ask, “I wonder what my sisters are up to? I haven’t heard from them in a while.” Nothing important is happening in the family, no health crises or upcoming reunions. I just wonder how the girls are. So I reach for the phone, but before I can dial I get a call from Diane (the Texas sister). I say, “What a coincidence! I was just going to call you.”

This sort of thing happens. But not all the time. Not even most of the time. The thousands of things that flit through our day almost never match up so nicely. And we don’t notice it when they don’t match up, because we don’t expect them to. The non-coincidences of everyday life go unregistered because they’re so pervasive.

On those rare occasions when things do sync up, we notice. In The Evolution of God, Robert Wright puts it well:

It makes sense that human brains would naturally seize on strange, surprising things, since the predictable things have already been absorbed into the expectations that guide them through the world; news of the strange and surprising may signal that some amendment of our expectations is warranted.

We usually attribute such coincidences to chance. But humans aren’t very good at thinking about chance. If the coincidence seems meaningful, as many do, we’re always tempted to consider it the result of some secret force. Did I send out invisible thought-waves that Diane somehow picked up? Did fate, or God, make her call me? In general, when we notice patterns, we look for causes. The phone-call convergence is a pretty minimal pattern, but even there we might be tempted to find a cause.

I hang up on Diane and the phone rings immediately. It’s Darlene (the peripatetic sister). “I was just trying to call you, David, but the line was busy.” This is getting weird. The pattern heightens and may prompt a stronger impulse to search for causes. Do we three siblings mind-meld in some mysterious fashion? (If so, though, why do we need phones?) It’s just a coincidence, highly improbable but, out of all the times we three think about one another and make phone calls, not impossible.

I believe that narrative artists in all media are practical psychologists. They trigger and exploit and heighten our ordinary ways of making sense of the world. Philosophers and statisticians have sophisticated ways of thinking about chance, but they needed special training to get beyond our folk psychology. Artists take us as we are.

Stories can use coincidences because we accept them. They are the sorts of things that sometimes happen, and so, as Aristotle argued, they are fit subjects for plot-making.

The poet’s task is to speak not of events which have occurred, but of the kind of events which could occur, and are possible by the standards of probability or necessity (Poetics, Chapter 9).

Here Aristotle points to two sorts of possible events. There are events that we expect to happen as a necessary result of earlier events; this corresponds to some notion of causality. Then there are events that are merely probable—things that are likely to happen.

But how likely is my call from Diane and the followup from Darlene? Aren’t these examples of what Aristotle dismisses as “the arbitrary and fortuitous”? Not necessarily, because for Aristotle too the storyteller is a practical psychologist. Things that seem unlikely, he says, can be motivated by reference to people’s beliefs or to the fact that improbable things are likely to happen occasionally.

Irrationalities should be referred to “what people say,” or shown not to be irrational (since it is likely that some things should occur contrary to likelihood) (Poetics, Chapter 25).

In sum, how do you motivate a coincidence? Aristotle recommends two tactics, which I could use if I were writing a story featuring the felicitous phone calls. People say that members of a family have a special affinity that can cross time and space. And anyhow, stranger things have happened.

Narrative norms

SPL.

Aristotle suggests a third motivational tactic as well. He says that unlikely things may be resolved “by reference to the requirements of poetry.” Poetry here refers to any verbal artform, just as poet refers to the maker of literary works in general. So what are the “requirements” of storytelling?

Most minimally, a plot needs an inciting incident. If I were a fictional character, my lucky phone calls might kick off a plot in which my sisters and I, feeling a new and mysterious bond, set out on road trips to meet somewhere. The telephone contrivance would correspond to the Hollywood dictum that coincidences are permissible at the outset of the plot.

Many commentators on Aristotle take his mention of poetic “requirements” to involve more specific conventions, especially those of different genres. We’ve long known that certain kinds of art works permit things that would be forbidden in other kinds. A children’s movie is unlikely to show chainsaw dismemberings, unless Eli Roth has been given a producing deal at Pixar. This idea of genre fitness or decorum has implications for coincidences too.

Clearly, coincidences flourish in comedy. The innocent young man trapped in a lady’s boudoir will have to hide under the bed because her husband bursts in at an awkward moment. In the long chase sequence through old Hong Kong in Project A (1983), Jackie Chan keeps bumping into his superior officer. Sometimes Jackie is set back by the encounter, but once the officer inadvertently rescues him. David Lodge writes: “Audiences of comedy will accept an improbable coincidence for the sake of the fun it generates.” His novel Small World culminates in a pile-up of coincidences in which an airline check-in clerk happens to give the heroine a copy of The Faerie Queene at the precise moment she needs to check a literary reference.

This is all highly implausible, but it seemed to me that by this stage of the novel it was almost a case of the more coincidences the merrier, provided they did not defy common sense, and the idea of someone wanting information about a classic Renaissance poem getting it from an airline Information desk was so piquant that the audience would be ready to suspend their disbelief.

Melodrama is another genre that relies on coincidences, particularly those that bring bad luck. (Think of Rock Hudson’s cliff-edge fall in All that Heaven Allows.) Likewise, I think that the revelations of the incriminating envelopes in Infernal Affairs and The Departed are partly motivated by genre conventions. In undercover tales, the detectives have to be alert for any physical items that might betray them or offer clues. So the envelopes are something that the hypersensitive narc could plausibly fasten onto. (Why the envelopes are left lying around in the first place is another part of the story, which I’ll come to.) Similarly, Initial D is partly a teenage romance, and we know that such films require an obstacle to happiness; that’s what Itsuki’s accidental discovery provides.

There’s another “requirement” of poetic art that can motivate coincidence, and it cuts across different genres. In Wilson Yip Wai-sun’s SPL (2005), a brutal martial-arts fight in a nightclub ends with the gangland chief Wong Po hurling Inspector Ma through a window far above the street.

Down below in a waiting car are Wong Po’s wife and baby son, the only things in life he loves.

Care to have a guess where Ma lands?

This is a coincidence motivated by poetic justice: The brutal Wong Po has inadvertently killed his wife and child. Serves him right!

As we might expect, Aristotle anticipated poetic justice too. He remarked that there was a special sense of fitness when the statue of a murdered man toppled over on his killer.

Three dimensions of narrative

Casablanca.

In an essay in Poetics of Cinema I argued that we can think of any narrative as having three dimensions: the story world, the macrostructure of the plot, and the narration–the flow of information as it’s presented, moment by moment, in the film. Each of these dimensions can motivate coincidence, and each answers to what Aristotle calls “requirements” specific to narrative art.

Say you want two characters to meet without making a rendezvous. One way is to establish that each has a routine. Jack stops for coffee at Starbuck’s every morning on the way to work; so does Jill. Sooner or later, it’s plausible that they will run into each other. The appeal to routine is probably behind the unlucky coincidence in I Corrupt All Cops. After being beaten, Unicorn staggers to the food stall across from his girlfriend’s apartment house–evidently on his way to call on her.

Another sort of story-world motivation involves characterization. In Initial D, it’s not implausible that the randy Itsuki would be hanging around outside a love hotel. Given his personality, he’s more likely to see Takumi there than other, more upright characters would be. In Infernal Affairs, Lau is a cautious mole, but he has no reason to hide the telltale dossier because he thinks it would be meaningless to anyone else. (Lau can’t know that Chan is the one who scribbled the corrected spelling on the envelope.) Lau’s studied nonchalance lets him stack papers on his desk without concern that this one is particularly revelatory.

Coincidence can also be motivated by the overall plot structure. If you start your film by alternating scenes showing two characters living their lives separately, you make it easier for your audience to accept what might otherwise seem a chance meeting between them later. After all, if they aren’t going to have some interaction, why are they both in this story? Sleepless in Seattle provides a clear-cut instance, although here the conventions of the romantic comedy genre also insist that the couple will get together. (Vera Chytilová’s Something Different of 1963 shrewdly defeats the expectation aroused by this sort of alternating construction.)

Likewise, a flashback structure can motivate coincidences. If we’ve seen the outcome of an action, even implausible events leading up to it can seem more natural. At the start of The Big Clock (1945) we see a hunted man hiding in a vast clock mechanism that surmounts a skyscraper.

In a long flashback, we see what led up to Stroud’s plight. Fired from his magazine job, he meets up with a blonde woman who takes him bar-hopping. They wind up in her apartment, but she hurries him out just as his boss Janoth comes in. Stroud watches Janoth go into the woman’s apartment.

The encounter isn’t wholly accidental. We know, as Stroud does not, that the woman is Janoth’s mistress, and she knows Janoth is coming to visit her. Nonetheless, what happens next leads to Stroud’s being fingered for murder. Stroud has pretty bad luck, but the opening frame story of his flight retroactively motivates his presence at the crime scene; we wouldn’t have the clock scene unless it proceeded, as Aristotle might say, by necessity from something pretty serious. The order of presentation coaxes us to accept whatever led up to the opening situation.

The story world and the plot macrostructure can do only so much. Sometimes coincidences need more fine-grained motivation. Here’s where narration, the patterned flow of information, comes in. If a cowardly cowboy is just about to leave the saloon when the bullying gunfighter enters, it can seem less stage-managed if we show, beforehand, the gunfighter riding into town with his minions. It doesn’t make the encounter more plausible in the story world, but it prepares us to find it more plausible: the two paths seem to converge. Here crosscutting accomplishes on the small scale what alternating scenes can do for macrostructure.

An even simpler tactic is to have someone announce that what’s happening is extremely unlikely. Lodge points out the audacity of Henry James in The Ambassadors when he presents a major moment through a character who reflects, “It was too prodigious, a chance in a million. . . ” This is the equivalent of Rick’s comment about Ilsa dropping into his gin joint. A frank admission of a coincidence can pull you through.

It was meant to be

Many of these motivating factors can work together with a more sweeping one. Recall that we’re sometimes tempted to consider everyday coincidence the result, or sign, of forces larger than we can comprehend–God, karma, fate, the Sibling Affinity Frequency. A narrative can motivate its coincidences by suggesting that they are working out an elusive but powerful pattern. Somehow, coincidence is just the hand of destiny. The French film known in English as Happenstance (2000) provides an example, but so does Serendipity (2001).

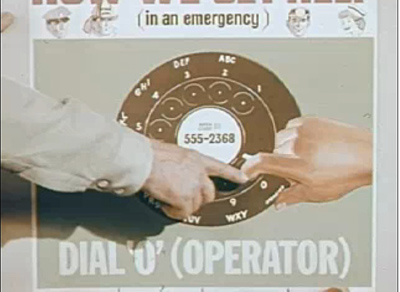

Jonathan and Sara meet cute in Manhattan, but mishaps separate them. They never learn each other’s identity. Years later, Sara is in San Francisco living with a musician, while Jonathan is about to get married. Vaguely dissatisfied and fretful, Sara returns to Manhattan to find Jonathan. Meanwhile, just before his marriage, he sets out to find her. Each one thinks that recapturing the love that flared up in one magical night would be worth one last effort.

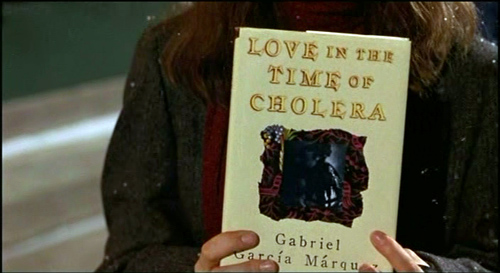

How do they find one another? Clues, plus coincidences. Jonathan starts to track Sara through a sales receipt for gloves she bought when they first bumped into each other. Sara returns to the Waldorf and visits “their” café in hope of finding some connection to Jonathan. But a lot of luck is involved too. Jonathan confirms Sara’s location thanks to her inscription in a used copy of Love in the Time of Cholera–a copy that his fiancée gives him, no less. By chance she bought Sara’s copy. Correspondingly, Sara finds the $5 bill Jonathan signed years before in her friend’s purse. Her friend got it as change at the café. The characters take purposive action, but they achieve their goals through coincidences.

These coincidences are simply outrageous. How can we motivate them? At the beginning of their magical night Sara announces that she believes that happy accidents are in fact controlled by fate. If she and Jonathan are meant to be together, things will arrange themselves the right way. She tells him this as they have coffee in her favorite café, Serendipity.

So Sara mounts some tests of their cosmic compatibility. She insists they leave the café separately: if they’re destined to remeet they will. Jonathan leaves his scarf behind, and she finds it, so they’re back together. She writes her contact information on a scrap of paper, but it blows away. “Fate’s telling us to back off,” Sara warns. Jonathan writes his phone number on the fiver, but she then pays for something with it, saying that if it returns to her, she’ll call him. In exchange, she’ll write her information in the Márquez novel and give it to a used bookshop; if he finds it, he can call her. Finally, at the Waldorf Astoria, each one is to get in a separate elevator car, pick a floor, and see if they’re in synch. It’s this test that leads him, through problems of timing, to lose her.

What motivates the cascade of coincidences, then, is the film’s starkly announced theme. In love, favorable coincidence is just serendipity; the film puts its operating procedure in Sarah’s mouth. To make your coincidences seem plausible, then, make your movie explicitly about how coincidences can be read as destiny.

But the theme doesn’t work on its own. Several of our other principles of motivation help out. For one thing we have Aristotle’s notion of common opinion: “What people say” about true love is that a couple is somehow meant for each other. In addition, of course, this is a romantic comedy, a kind of film that depends on separating and uniting lovers. We’d be very surprised, not to say disappointed, if these two didn’t wind up together. Genre helps motivate the way coincidences help out the couple.

Perhaps most interestingly, the “requirements of art” in Hollywood dramaturgy include a symmetrical play with motifs and character traits. Each lover is given a token—$5 bill, Márquez novel—and certain locales gain significance through repetition (Bloomingdale’s, the Waldorf, Serendipity, the skating rink). At the start of the film, Sara is the romantic, while Jonathan is more pragmatic. After a few years as a psychotherapist, however, she no longer trusts in fate. But by searching for her, Jonathan becomes a passionate believer in signs, reading everything around him as a possible trace of her presence. His pursuit of a love that defies likelihood moves his friend, the journalist Dean, to write a hypothetical obituary:

Even in certain defeat the courageous Trager secretly clung to the belief that life is not merely a series of meaningless accidents or coincidences. Uh-uh. But rather it’s a tapestry of events that culminate in an exquisite, sublime plan.

That plan is worked out through a traditional plot symmetry. Sara had found Jonathan’s scarf in the café at the start. At the climax, he discovers her jacket on a bench overlooking the ice rink where they shared their first date. (She had gone back there in a nostalgic mood earlier in the day.) Now, coming back for her jacket, she reunites with Jonathan. Hollywood’s use of tokens and props to develop the drama fits nicely with the theme of fate’s good offices. You could say that the vicissitudes of destiny are recruited to motivate some principles of classical plot construction.

Time out

You may dislike all the films I’m mentioning (Serendipity?! That’s a movie for wimps!). But my purpose here isn’t evaluative. I want to explore some principles that are used to make stories hang together, more or less. The same principles are present in what we sometimes call art films, from Bicycle Thieves to The Headless Woman. Coincidences abound in these movies, often motivated as the randomness of life, or n-degrees-of-separation, or mysterious larger forces that create correspondences (Paris nous appartient, the Three Colors trilogy of Kieslowski). Appeal to realism, to folk psychology, to genre, to thematic significance, and to formal unity can be found in virtually all narrative cinema. Here as elsewhere, I’m just trying to make such principles explicit and study how they work.

In thinking about those principles, I’m struck by one more way in which narratives need coincidences. What makes a story intriguing, or even worth paying attention to?

Here’s a story. I got up this morning, had breakfast with Kristin, went to school to take some frame enlargements from Hong Kong films, and dropped off the slides at a lab before coming home. Technically, it’s a story, but you yawned halfway through. To be engaging, stories need a remarkable situation or twist—a lover betrayed, a man pursued for a crime he didn’t commit, a cop discovering that his savior is his worst enemy, people who meet and fall in love and then lose one another.

We need, in short, something out of the ordinary. Coincidences, popping out from the bland backdrop of everyday life, can provide an uncommon event. At the start of a plot, they launch the action. At intervals, and with the proper motivation, they can be invoked if they liven things up. The effect may go back to the strangeness that Robert Wright suggests that we’re always on the lookout for.

Granted, the effect of motivation is to make coincidences seem less strange than they might otherwise seem. Most of these factors work to give the coincidences a sort of causal boost. Itsuki sees Natsuki because he’s at the love hotel, Chan/ Billy notices the envelope because he’s an alert cop, Jonathan and Sara get together again because they follow up clues and try really hard and anyhow an unseen hand (causally) shapes their fate, and so on. The coincidences are often covered by a causal alibi. That suggests that what’s most coincidental in these situations is timing.

Most movie coincidences run on tight schedules. A few moments later, Itsuki wouldn’t have seen Natsuki leave the love hotel; Unicorn wouldn’t have caught his wife with his boss; Chan/ Billy wouldn’t have found the telltale envelope; and so on. As the film unrolls, we want our extraordinary events tied to close shaves, barely missed messages, and revelations taking place under a ticking clock.

Every moment in filmic storytelling seems to bristle with possibilities of convergence and revelation. The sort of actions that make stories interesting are even more gripping if they take place under time pressure. Very often, if a key event had happened slightly earlier or later, there would have been no coincidence. And movies, unrolling at a pace to which we all submit, are well-suited to arouse our interest with turns of events that might, just barely, have been very different. Perhaps we accept the power of good or bad timing because, to recall Aristotle, “people often think” things like this: If I had missed that train, I would never have met my soul mate. . . .

Clearly, though, timing is a tale for another occasion.

My thanks to Ben Brewster for discussing these ideas with me and reminding me of the Chinese adage. That precept is briefly discussed in Kam-ming Wong, “‘No Coincidence, No Story’: The Esthetics of Serendipity in Chinese Fiction,” International Readings in Theory, History and Philosophy of Culture (St. Petersburg, Russia: EIDOS, 2003), Vol.16, 180-97.

My references to the Poetics come from Stephen Halliwell’s edition, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), pp. 40, 42, and 63. My extracts from David Lodge’s The Art of Fiction (New York: Viking, 1993) are from his section on coincidence, pp. 149-153.

Hilary P. Dannenberg’s book, Coincidence and Counterfactuality: Plotting Time and Space in Narrative Fiction (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2008) includes many intriguing ideas about coincidence. Her focus is the “coincidence plot” in which people realize they’re related to one another. Some of her arguments are presented in more compact form in her article, “A Poetics of Coincidence in Narrative Fiction,” Poetics Today 25: 3 (Fall 2004), pp. 399-436.

P.S. 31 September: In a study of The Pledge, film scholar Gary Bettinson has a valuable discussion of how coincidence can be motivated to resolve a plot. It’s available here.

Serendipity.

Now you see it, now you can’t

DB here:

We usually respond to films spontaneously, but afterward we can think about our responses and figure out why we reacted as we did. When we’re fooled by a mystery, for instance, we can re-watch the film and trace exactly how we were misled. Now that Shutter Island is out on DVD, fans will be dissecting its visual gimmicks. Even when a film isn’t a mystery, a lot of critical analysis involves what we might call a rational reconstruction of how the whole shebang works. Novice screenwriters crack open a movie like The Apartment or The Godfather to peer into the fine mesh of plot construction, to tease out all the setups and plants and twists that seem inevitable only after the fact.

This is film research, we might say, at the personal level. Not in the sense of your or my unique identity, but rather at the scale we see the world. We don’t see atoms or gravity. We evolved to sense and think about middle-sized social and physical phenomena, like places and objects and, especially, other humans. We’re aware of the world because we sense ourselves as individual agents, guided by intentions and desires and beliefs. We’re used to talking about films at this level. When we track action and character, note surroundings and time passing, or ask about the purposes of a plot device or theme, we are working at the level of personhood.

But life assigns us to other levels too. There is the subpersonal level. All kinds of things are happening to you now that you can’t be aware of. You can’t watch the cells in your retina detect this sentence, or the neurons in your brain firing to make sense of it, or the flow of signals to your hand urging the mouse to scroll onward. A huge amount of our mental activity takes place behind the scenes that flit through our consciousness. We can’t pay attention to the man behind the curtain—partly because there is nobody there.

There’s also the suprapersonal level, the level of collective behavior patterns. Now we’re talking about people as parts of large-scale forces, like groups and cultures and societies. Historians have traditionally worked at this level. For example, some researchers have traced how film audiences, en masse, have responded to movies.

More strikingly, many scientists now study “self-organization”—the emergence of patterns of order that don’t seem to be willed or intended by individuals or groups. We find impressive instances in nature: fish swim and birds flock in intricate patterns that no one fish or bird could imagine or dictate. Such self-organization is even more striking in human activities like traffic flow or online networks. Is there a sort of “physics of society”? No doubt people have intentions and quirks, but often we can bracket those out and see shapes in the data that no one could have designed. The classic instance is a power law. A remarkable example is Vilfredo Pareto’s discovery that income distribution in any society tends to settle out as 20 percent of the people controlling 80 percent of the wealth. Mark Buchanan sums up the suprapersonal viewpoint this way: “Think patterns, not people.”

We know we can study films at the personal level. How can we study films subpersonally and suprapersonally too?

Reverse-engineering a movie

Mon Oncle.

My answer comes after four days earlier this month at the annual convention of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. We met in Roanoke, Virigina, in a massive nineteenth-century hotel made over into a convention center. You know the place has things under control when every PowerPoint presentation works flawlessly.

What ideas unite the film scholars, psychologists, and philosophers who gathered here? Roughly, the members explore moving-image media through empirical methods. Empirical inquiry can include classic scientific method (hypothesis/ experiment) or methods of aesthetic, historical or quantitative analysis. Typically the goal is not interpretation of a particular film or TV show or videogame but rather understanding of some general aspects of these media. Not explication, we might say, but rather explanation. Further, most members of the Society are interested in ways that film can be illuminated by areas of modern psychological research, such as neuroscience, cognitive science, and evolutionary psychology.

Some of our philosophers would say that they pursue conceptual analysis rather than empirical inquiry. Still, they join our meetings because the sorts of concepts they want to analyze are the ones that the film folk and the psychologists deploy—concepts like artistic intention or the nature of genre. Many of our liveliest sessions have come from disputes between Filmies, Psychos, and Philosophes.

For more on what we do, I’ve offered some background in earlier entries on this site. I previewed the 2008 convention here and here. I previewed the 2009 convention here and here.

Previews, but not followups. The big problem covering these events is that they’re so busy I have no time to blog during them, and by the time they’re over I’m usually en route to Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. So I tended to make those entries introductions to the cognitive perspective, rather than surveys of who said what. This year, because our gathering was earlier than usual, I’m trying to sum up the event reasonably soon after it ended. We had simultaneous sessions, sometimes three at once, so I attended fewer than half of the talks. I’ll try to mention presentations that seem relevant, even if I didn’t hear them. Similarly, I heard some presentations (e.g., Lisa Broad on possible worlds) that were stimulating but don’t quite fit into my thesis here.

There were plenty of talks that developed arguments at the level I called personal. That is, they analyzed how films were designed to achieve certain effects. This calls for “reverse engineering”: starting from plausible viewer responses and then looking for creative choices made by the filmmakers that seemed to fulfill particular functions.

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Take as an example Carl Plantinga’s paper on how we strike up moral attitudes toward characters. He was interested in how we achieve what Murray Smith calls “allegiance”—a “pro-attitude” toward certain characters. Is it just a matter of wishing good things for them, or admiring their positive traits? Is it a matter of sympathy for their situation?

Carl argued that all these factors play a role, but they aren’t enough to assure our siding with a character. He argues that allegiance also involves moral judgments, or rather moral intuitions. Films exploit two facts about these moral intuitions: they must be summoned up quickly, without much thought, and they are often driven by emotion rather than ideas.

Oddly enough, our moral intuitions are not necessarily driven by moral standards! Carl drew on Anthony Appiah’s analysis of moral judgments as influenced by how a situation is framed, ordered, and primed—basic cognitive cues that influence responses. For example, Legends of the Fall sets up two brothers, one conventionally moral and the other not. Yet it’s the wild, violent Tristan who earns our sympathies, because he displays vitality, youth, beauty, sensitivity, and closeness to nature. The upshot is that we rationalize a moral judgment on non-moral grounds. Carl got several questions about his conception of morality and the possibility that our moral intuitions are tied to things we value, like beauty.

Malcolm Turvey offered a paper on gags in Jacques Tati. Pointing to prior work on how Tati’s gags are integrated into a shot’s composition (scattered so that we may miss them) and linked to one another (through overlap, Kristin has suggested), Malcolm went on to argue that the gags themselves don’t obey the conventions of classic comedy. They exhibit strategies of misinterpretation, blockage, ellipsis, fragmentation, and concealment that are highly original and unusually challenging. Malcolm is working on a book on “ludic modernism,” and he sees Tati as fitting into this tradition.

Malcolm’s precise and persuasive account was framed by a strong attack on the tendency of cognitive film theory to concentrate on ordinary, even undistinguished films and ignore problematic and avant-garde instances. He pointed to passages in Stephen Pinker’s writings that mock experimental art, and he urged cognitive film researchers to “call Pinker out” for his borderline Philistinism. He remarked that psychological researchers could learn as much from Tati’s work as from ordinary films…and maybe discover new things.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

A similar sort of rational reconstruction at the level of personal response was found in many other papers I heard. Jason Gendler dissected the misleading narration in The Blue Gardenia. Rory Kelly wondered why viewers tend to forget the water-utility plotline at the start of Chinatown. James Fiumara considered why modern startle effects are comparatively rare in classic horror films. Torben Grodal isolated a group of “disgust-driven phobic films” (Taxi Driver, Blade Runner, Se7en) that sink so deeply into disgust that melancholy drives out empathy. Lennard Hojberg studied circular camera movements that express the dizziness of love as based on embodied vision.

Some researchers used quantitative procedures to capture a film’s regularities. Monika Suckfuell (right) exposed some very complex patterns in a short film, Father and Daughter. These create a distinct emotional tone through what she calls “distance editing.” The patterns are combinations of thematic units like problem-solving or humor, and the recurring combinations arouse both comprehension and pleasure. In another quantitative study, Tseng Chiaoi and John Bateman sought to tie concrete uses of filmic elements with more abstract aspects of meaning. (Chiaoi and John had done a presentation on film-based discourse semantics at last year’s event.) Concentrating on characters’ action patterns, Chiaoi used computer software to trace their structures in television commercials and the war genre.

Squeezing the stimulus

Bopping after a session: Tseng Chiaoi and Paul Taberham.

The talks I’ve mentioned, along with several others, analyze processes that we can access by re-viewing films, studying their form and materials, and examining the genres and stylistic traditions to which they belong. But other talks concentrated on the subpersonal areas, the parts of our responses that we can’t access so easily.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

For instance, how do we mentally stitch together various shots to create a unified space for a scene’s action? Film scholar Todd Berliner and psychologist Dale Cohen presented an account of how we achieve an illusion of spatial continuity. Initially the brain grasps shots as if they were pieces of space selected by the viewer, and then it builds up a model of the whole space—say a porch in front of a house’s front door. When a character moves his arm a certain way toward an offscreen area, our model of porches and doors makes it most probable that he is pressing the doorbell.

In such ways we run “beyond the information given.” Filmmakers count on our doing that, so they give us feedback (say, the sound of a doorbell, or a shot of a door opening) that confirms our model of the space. Most mainstream films build in such redundancy. But the unity of these spaces is undermined by some contemporary exhibition technology. Todd and Dale suggested that the mental models we build of space exclude the movie theatre, so that surround sound and 3D become problematic.

They also got several good questions. How concretely specified are these model spaces? How do they develop in the course of a scene? Might our perception of continuity come down to a lack of perception of discontinuity—that is, maybe we operate on very simple default assumptions and don’t build up many models of the space.

Todd and Dale’s presentation was in the Helmholtz tradition; they even invoked “unconscious inference” as part of the story. Another tradition, represented by SCSMI founders Joseph and Barbara Anderson, invokes James J. Gibson’s ecological approach to perception, which argues that such modeling and inference-making isn’t really happening. Things are much more direct: Perception is data-driven, and needs top-down correction only in rare cases (like nighttime or fog).

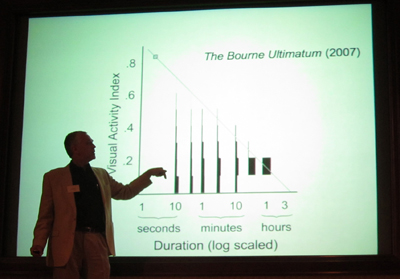

Other perceptual researchers try for a more parsimonious research strategy: How much information about the visual world can we squeeze out of the stimulus? This question was raised by Jordan DeLong, who has been exploring how we can identify emotional arousal through very “low-level” information. Using a corpus of 150 films (more on this later), he looked at shot lengths, the distribution of shot-lengths across a film, and a purely physical measure of visual activity (essentially the change from frame to frame) to see if they correlate with genres we associate with high levels of arousal, like action and adventure films. Jordan’s study is preliminary, but there is the possibility that certain purely physical features are reliable indices to levels of arousal—even if people don’t notice those features and are much more fastened on characters and their actions.

The current projects of Tim Smith’s research team exemplify the parsimonious strategy. Tim is a long-time participant in SCSMI, and his talks show how a research program can expand and enrich itself.

We know people look at certain areas of a shot. We also know that our attention is directed, driven by features of the stimulus. What features? We filmies would pick out shot composition, color, movement, lighting, shot scale, etc. We can access those middle-level variables through expert introspection and analysis. But can those features be further decomposed?

Tim thinks so. We can consider any of these technical qualities as made up of luminance, color channels, and other low-level physical aspects of vision. Through signal-detection methods, Tim seeks to pinpoint what the crucial variables are. The results of his work are soon to be published, and I don’t want to give the game away. I’ll just say that he has shown through eye-tracking that certain low-level features are more important than others in engaging viewers’ attention.

One implication of Tim’s findings is that what I’ve called “intensified continuity” seems to have an optimal grip on spectators. This technique, he remarked, “almost paralyzes the eyes,” yielding “an illusion of active vision with passive eyes.” More generally, his work seems to back up James Cutting’s remark that “There is no such thing as voluntary attention sustained for more than a few seconds at a time.” Most of our attention is at the mercy of the outside world, which means that filmmakers need to engage us at every moment—either with narrative, or with something else we’ll find arresting.

Dan Levin, Pia Tikka; in the background William Brown, Carl Plantinga, and Dirk Eitzen.

Dan Levin gave the keynote address at SCSMI two years ago, and he showed how we vastly overrate our ability to spot outrageous changes in the world or on the movie screen. (He’ll have a field day with the tricks in Shutter Island, such as the one surmounting this blog.) This time around Dan talked about Theory of Mind in the movies, the ways that films exploit our (species-specific?) inclination to attribute beliefs, desires, and goals to the creatures we see in the world, and in films. His paper scanned mandatory, bottom-up cues, middle-level activity (the sort of organization of visual space Todd and Dale discussed), and then “controlled cognition,” such as our narrative expectations. So for Dan it’s not all in the stimulus. Once we’ve picked out certain aspects of it, our Theory of Mind system locks on them.

What aspects? Chiefly, signals of intention and marked eye direction. When we think we’re watching an intentional agent, like a movie character, we tend to see the agent’s eye direction as giving us a clue to his or her aims. Using films he has made, Dan tests people for how eyeline-matched cuts are read, and he varies the cues to see how people construe them differently.

Interestingly, when he showed the same shots in a different order, about two-thirds of the subjects didn’t notice that the order was different. That is, whether the object of the glance or the person glancing came first, gaze deflection remained the primary cue to understanding the situation. This suggests to me that storytelling cinema doesn’t absolutely need the classic pattern of person looking/ person looked at/ person looking, but the extra shot makes sure we all understand (redundancy again).

A similar sort of top-down/ bottom-up theory was proposed by Dan Barratt, who gave it a more computational spin. Like Tim, he works on eye movements; like Todd and Dale he’s interested in how we construct space; like Dan, he seeks out intentional factors. It’s not all in the stimulus, but we won’t know how much until we keep squeezing.

Ripples in the flow of films

The Society broke new ground in what I called the “suprapersonal” realm, that of large-scale patterns of activity that aren’t explicitly coordinated by individuals or groups. Several researchers are probing this in relation to films. Films are, in effect, deposits of human behavior; they are artifacts resulting from choice. What if we find patterns of choice that we can’t plausibly trace to coordinated decision-making?

Chris Atherton raised the issue by considering how to study style statistically. Citing Barry Salt as a pioneer in the area, he focused on the work of the Cinemetrics group and offered suggestions on how to better collect data and track patterns at various levels of generality. More sharply, he posed the question of function. How can you measure that? One implication was that in a big body of films we can disclose order that can’t wholly be explained as the sum of individual choices. Those choices matter, but so do forces we have yet to determine, including historical processes. Chris’s reflections chimed nicely with those of our keynote speaker.

James E. Cutting is a distinguished perceptual psychologist at Cornell. He’s written a fine book on motion perception and has done a quantitative historical study of the creation of the canon of French Impressionist painting. He’s a former dancer and a sensitive appreciator of art and music (and film). He’s the ideal person to analyze ticklish aesthetic issues.

You may have run across him recently because his research on Hollywood films was picked up and trumpeted in the press. “Solved: The Mathematics of the Hollywood Blockbuster,” read one headline. Needless to say, James was doing something more subtle. You can read summaries here and here.

In his lively address, “Attention, Intensity, and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” James explained two of his areas of interest: the ebb and flow of change across a film, and how that change is tied to human pickup. James studies these topics with a big database: 150 movies from 1935 to 2005. He emphasizes widely seen films belonging to five genres and chosen from the highest-rated titles on IMDB. But there’s a micro- side too. He and his research team went through every film frame by frame coding each one along many dimensions.

Naturally, he takes on the vexed issue of Average Shot Length. You can read the ongoing discussions of this concept on Yuri Tsivian’s Cinemetrics site. What interests James is less ASL in itself than the ways in which comparable patterns of shot lengths cluster in certain parts of the film. A film’s ASL may be 8 seconds, but in some passages several shots might have similar lengths, say 12 seconds each. Moreover, those patterns may “ripple through the film,” recurring at certain intervals and different scales (shot clusters, scenes, or other chunks).

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

Not every film shows such patterns; film noirs seem random in their patterns of shot lengths. But many movies, especially those of the last fifty years do display these patterns—typically clusters of short shots for physical action, clusters of longer ones for conversations. This clustering tendency is on the increase, even outside the action genre.

The finding leads James to ask about the pacing of visual change, which raises the prospect of the sort of tension/ release dynamics we find in music. The patterns he finds don’t look arbitrary because they match the so-called 1/f or pink-noise pattern. This pattern has been detected in the natural world, in heartbeats, and in brain activity. It’s also been discovered in reaction times to tasks. In effect, the 1/f pattern captures not continual attentiveness but rather an alternation of intense concentration, moments of slower pickup, and moments of sheer mind-wandering. A nontechnical explanation of the 1/f pattern is here; a technical one is here.

As for intensity, James is seeking to measure visual activity in the shots. How much change, in effect, can there be from frame to frame? This can be captured by correlating each frame with its mates. James and his team find that from 1930 to 1950, there’s been a steady increase of frame-to-frame visual activity across all genres. The images became busier, with more movement. Today, he suggests, Hollywood is exploring ways to raise the frame-to-frame visual activity—not only through lots of movement of characters (the action film comes to mind) but also through “queasicam” handheld movements.

In combination with decreasing ASLs, Hollywood seems to be asking: How briefly can I show you this and still get the point across? So far, James suggests, films like Mission: Impossible III and The Bourne Ultimatum seem to be the busiest at the visual level. But animated films score about the same.

James has a caveat: The size of the screen matters. Even a big home-theatre screen doesn’t duplicate the breadth of a theatre screen, which activates not only our central vision but our peripheral vision too. That’s why bumpy shots that you can tolerate on a computer monitor may make you queasy at the multiplex. Interestingly, the Bourne films and Cloverfield, James suggests, were more popular on IMDB after the DVD versions came out. Perhaps people were better able to assimilate them on a smaller display.

At one level, James is interested in the subpersonal factors. He grants that you don’t notice cuts but can attend to them if you shift your focus from the story. But the widespread patterns he discloses aren’t easy to ascribe to deliberate planning. Nobody but an avant-gardist would decide to have shots of similar lengths at points 14 minutes or 25 minutes apart throughout the film. But James finds such correlations at levels beyond chance.

I can’t pretend to understand everything mathematical in James’ argument, but I think that his discoveries open up a new way to think about pacing in film. My first impulse is to think about historical causes, as Chris suggests: filmmakers learning from each other, converging on optimum choices. But I also like to entertain the possibility that this optimum carries a resonance even beyond the flux of history. Perhaps like fish and fowl, filmmakers are obeying and viewers are fulfilling, completely unawares, deep rhythms built into nature and numbers.

A tangled databank

Traditional humanists would decry a lot of what goes on at SCSMI meetings. The appeal to general explanations, the recourse to biology and evolution, the use of quantitative and experimental methods would all smack of “scientism.” But more and more, humanists are starting to turn away from the endless reinterpretation of canonical or non-canonical artworks. Many are also quietly defecting from the Big Theory that dominated the 80s and 90s. In film publishing, I’m told, editors have come to an informal moratorium on books on Deleuze. Possibly more people write them than read them.

Committed to a theory of permanent revolution in Theory, humanists are seeking new pastures. Some have discovered neuroscience, others evolutionary psychology. Franco Moretti has launched quantitative studies of the literary marketplace. For many converts, the reconciliation with science is just a bandwagon to hop onto, and they will jump off when a newer one trundles past. But other scholars have been committed from early on. The prospect of “consilience,” the compatibility between the sciences and the arts, is something the literary Darwinists like Brian Boyd, Jonathan Gottschall, Joseph Carroll, and like-minded souls were defending long before it became fashionable.

Film theory, as Joe Anderson is fond of pointing out, has a long and intense fascination with experimental psychology. Hugo Münsterberg, Rudolf Arnheim, and Sergei Eisenstein saw no conflict in studying film art with tools and findings derived from the sciences. That interest was lost in the 1960s, for a variety of reasons. But some of us have persisted. An explicitly “cognitive” perspective has been developing in film studies for the last twenty-five years, and SCSMI has nurtured this tradition since 1997. Our commitment is deep. We’re making headway. We’re not going to go away.

There is grandeur in this view of life, and cinema.

Our Society owes a great debt to Stephen Prince of the Virginia Tech School of Performing Arts and Cinema, who hosted this year’s convention. He also gave a splendid paper on the research traditions behind precinematic optical toys, as a way of thinking about modern CGI.

I found these books on suprapersonal patterns helpful: Mark Buchanan, The Social Atom: Why the Rich Get Richer, Cheats Get Caught and Your Neighbor Usually Looks Like You (London: Cyan, 2007); Steven Strogatz, Synch: The Emerging Science of Spontaneous Order (New York: Theia, 2003); Philip Ball, Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another (New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 2004).

Todd Berliner and Dale Cohen’s paper, “The Illusion of Continuity: Active Perception and the Classical Editing System,” is scheduled for publication in the Journal of Film and Video in 2011. Tim Smith’s paper is in press at Cognitive Computation as P. J. Mital, T. J. Smith, R. Hill, and J. M. Henderson, “Clustering of gaze during dynamic scene viewing is predicted by motion.” You can check Tim’s DIEM project for video demonstrations, and his blog, Continuity Boy.

The original article by James Cutting, Jordan DeLong, and Christine Nothelfer, “Attention and the Evolution of Hollywood Film,” appeared in the March issue of Psychological Science. Access is through subscription.

As for Shutter Island, thanks to Justin Daering for pointing out the double sleight-of-hand. More thoughts on the film and Scorsese’s expressionist/ impressionist tendencies are in our backfile.

1999 Conference of the Center [later Society] for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image; Valby, Denmark. Photo by Johannes Riis.

Scorsese, ‘pressionist

Shutter Island.

I was interested in the way she presented herself at that moment. Later on I figured out that as she gets up from the chair we should do it in three cuts, three separate close-ups, because I think he’ll never forget that moment the rest of his life. He’ll play it back many times. . . . It’s just his perception, his memory of what it’s going to be like. . . . We shot it very quickly, two takes each, one at 24 frames, one at 36, and one 48.

Martin Scorsese, on filming The Age of Innocence.

DB here:

Few directors think so carefully about how a film looks and sounds. Sensitive to technique in the work of classic filmmakers, Martin Scorsese has always tried to give each picture a vivid visual and auditory profile. Although he’s often praised for his realism (usually prefaced by the adjective “gritty”), Scorsese is often a subjectively oriented director. This quality goes beyond the justly celebrated performances of his actors. He is unafraid to use unusual cinematic techniques to thrust us boldly into the characters’ minds and emotions. In this effort he joins some great cinematic traditions. No surprise there: He has an immediate sense that film history hovers over every choice a director makes.

Spoilers loom out of the mist ahead.

Inside out, outside in

Raskolnikov.

Once American filmmakers developed a model of visual storytelling in the late 1910s, filmmakers elsewhere were surprisingly quick to push it in more subjective directions. There emerged something like an international division of techniques.

To convey inner experience, German directors of the 1910s and 1920s worked principally on aspects of mise-en-scene—performance, staging, setting, lighting, costume, make-up, and the like. The classic example is The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920), in which the cutting and camerawork are fairly conservative, but the setting and acting seek to convey a madman’s vision of the world.

Caligari “subjectivizes” the characters’ surroundings, a process signaled through warped perspectives and fantastically distorted settings.

This brand of visual contortion became the hallmark of what was called German Expressionist cinema. Scholars argue about exactly what films belong under that rubric, but Caligari, along with From Morn to Midnight (1920) and Raskolnikov (1923, above), are pretty uncontroversial examples of making the external world reflect the characters’ psychic turmoil.

At the same period, French directors were also experimenting with subjective cinema. But they tended to concentrate less on mise-en-scene and more on what the camera could do to suggest both optical and mental point of view. In the so-called “French Impressionist” school, we find framings, angles, distorting lenses, changes of focus, slow-motion, and other cinematographic techniques used to suggest characters’ mental states. Thus in Germaine Dulac’s Smiling Madam Beudet (1923), the downtrodden wife sees her husband as monstrous.

In El Dorado (1921) Marcel L’Herbier uses a gauzy filter to suggest that his heroine is distracted, before pulling it aside and letting her face come into focus.

A little later, leading Soviet filmmakers made editing, not mise-en-scene or camerawork, their most salient technique. They experimented with graphic and rhythmic montage, as well as cuts that sacrificed spatial and temporal continuity to eye-smiting impact.

Of course this three-way division of technical labor is too neat. You find some camera experimentation in German Expressionism, as with the fast motion in Nosferatu (1922). The French were using rapid cutting even before the Soviets, as Gance’s La Roue (1923) shows. And some Soviets, such as Eisenstein and the FEKS directors, explored unusual lighting and camera angles. It should be said, though, that these shared techniques often serve different purposes. Fast cutting in Impressionist films tends to suggest the heightened experience of the characters, rather than serving, as in the Soviet case, to dynamize a historical situation for the viewer. The quick cutting in the carnival ride in Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidèle (1923) simulates the chaotic burst of “impressions” felt by the characters, but the quick cutting in the street riot of Strike (1925) doesn’t mimic the characters’ states but aims to arouse shock and suspense in us.

In any case, my technical division remains only a first approximation toward understanding pretty complicated historical trends. The main point is that both the German Expressionist and the French Impressionist filmmakers of the 1920s were seeking to use particular film techniques to give the audience a deeper sense of the characters’ sensory experience and emotional states.

American cinema selectively adopted some of these tactics of lighting and set design. In a blog entry and a web essay, I’ve written about William Cameron Menzies as one importer of the German approach. You can see Expressionist touches in Fox’s Mr. Moto movies. Likewise, 1940s films particularly enjoyed mimicking Impressionist camera tricks to signal drunkenness, delirium, hallucination, and other altered states. Hitchcock’s Spellbound (1945) and Wilder’s Lost Weekend (1945) are famous examples. Typically such Expressionist and Impressionist touches were associated with crime, craziness, or genre stylization. Much of this flagrant irrealism went out of A-pictures in the 1950s, but it survived in horror and, interestingly, in the US avant-garde cinema of Deren, Markopoulos, and others.

One of Scorsese’s contributions to the 1970s, I think, was to revive and consolidate this legacy. While we were celebrating his films as victories for urban realism and neo-Method acting, many of the movies were also charged exercises in subjective cinema.

Making streets mean, and meaningful

Taxi Driver.

From Mean Streets (1973) everyone remembers the aura of street-punk camaraderie, the harsh turns of mood (usually triggered by Johnny Boy’s recklessness), and the vibrancy of the neighborhood, with its social hierarchy and rituals of bullying and bluff and negotiation. Alongside these tokens of realism we find breathless grace notes, as when Charlie glides through the club, a visual equivalent of his joy in being among pals and sexy women. (The shot was made by having Keitel ride the dolly instead of walking in front of it.)

This euphoria of this neo-Impressionist shot is counterbalanced later by the Rubber Biscuit song, with Charlie now thoroughly drunk and floating in grotesque frontal close-up before the floor rises up to kiss his head.

Charlie has come in to the club announcing himself as Jesus, a pious man to create order. Now this shot charts his fall from drunken exuberance into queasiness and mounting anxiety about Johnny Boy’s debt.

More generally, Tony’s club is given heavily unrealistic treatment through slow-motion and faked slow-motion, along with character movement synchronized with the music. If the camerawork mimics Charlie’s mental states in Impressionist fashion, the ruby-red club lighting suggests his erotic inflammation in a mildly Expressionist one.

Taxi Driver (1976) is Scorsese’s most famous venture into subjectivity. From the first shot of the cab heaving through wafting vapor—steam? smoke? sulfur fumes?—we cut to a man’s eyes, and then to dissolving views of the city through a rainy windshield.

From the start Scorsese announces one of his most basic strategies: a realistic motivation for expressionist effects. It’s only rain, but shooting it through the windshield and adding slow motion gives the streets an otherworldly shimmer. As the neon dribbles down the glass, and we see pedestrians moving through tinted clouds like hesitant ghosts, the man’s face becomes bathed in a red glow—vaguely motivated as reflected from the traffic light, but unrealistically saturated, as in the Mean Streets club.

We see the real New York, but filtered through the eyes of a man who considers it an open sewer. The plot will soon lock us into his consciousness more explicitly, through restricted point of view and voice-over diary extracts and crisp montages of the cruising cab. In addition, the motifs introduced here, particularly purifying water and blips of light, will become elaborated in the course of the movie. The general point, however, is that Scorsese has updated Impressionist and Expressionist tactics in order to reveal a man’s mind through images.

Qui tollis peccata mundi

Bringing Out the Dead.

In some films Scorsese plays things straighter, invoking subjectivity only briefly. There are the prizefights and the visions of Vicki in Raging Bull (1980), and the slipperier passages of fantasy in The King of Comedy (1982). But other films plunge us deeply into subjectivity, forcing the world through the filter of a driven character’s sensibility.

For thoroughgoing efforts in this direction we can look to Bringing Out the Dead (1999). In this movie about a paramedic haunted by spirits of those unfortunates he might have saved, Scorsese along with cinematographer Robert Richardson and production designer Dante Ferretti reinvoke the nightmarish qualities of Taxi Driver. The exhilaration Frank Pierce gets from saving lives is offset by his despair at gambling with death every night. The result is another exercise in neo-Impressionism and –Expressionism.

Once again rain and light, objectively out there in the urban world, become projections of the character’s tormented psyche, thanks to camera angle and framing. The windshield gives Frank’s face phantom tears.

Once again concrete shapes and colors, filtered through a moving vehicle, are distorted to suggest the protagonist’s anxieties.

To measure Frank’s descent into desperation, the camera even follows the ambulance upside down, or sideways.

Scorsese ventures into full-blown Expressionism as well. There are naturally dream sequences, but we also get the unforgettable image of the drug dealer Sy, impaled on a fence rail and reaching toward skyscrapers as fireworks (real fireworks?) consecrate his gesture. Later, hurtling through the city and moving closer to mental breakdown, Frank starts to see every woman on the street as Rosa, the woman he could not rescue. How the Germans would have loved having CGI available for such a hallucination.

Perhaps the subtlest touches are the patches of blown-out white. At first they seem a signal of death, gleaming off the bodies of Mary’s father and the young man found on the street.

In the final scene, Frank tells Mary of her father’s death (and sees her as Rosa). She invites him in and eventually he falls asleep in her arms. The final shot quietly shifts from a normal, rather dark texture, to one endowing his shirt with a blinding glow.

This change in lighting and exposure, unmotivated by any realistic source, suggests that Frank feels he has found a bit of peace, while also hinting that a spiritual radiance has entered this unhappy world through a tortured secular saint.

Shutter Island caters to the ‘pressionist side of Scorsese’s vision. It hovers between realism and subjectivity: parts of what we see are really happening in the fiction, while other parts are wholly in Teddy/ Edward’s mind. The difference is that here the balance tips strongly toward expressionism. Apart from the dream sequences, certain hallucinations are rendered in undistorted terms. So, for instance, scenes like the cave conversation with the second Rachel Solando are wholly Teddy’s mental projections. Other scenes oscillate between subjectivity and objectivity, as when Teddy is preparing to set fire to Cawley’s car and talks with his wife Dolores–although the next shot confirms she’s not really there.

I find all this less resourceful than the virtuosic ways in which Scorsese subjectivizes the neighborhoods of New York. The Gothic trappings of the hospital, the cagelike wards, and the rainswept island offer less opportunity for novel stylization than an urban landscape. Moreover, I think that the creaky gimmick ruling the plot of Shutter Island relies on farfetched explanations and leaves too many loose ends. If the storm didn’t really occur, as Dr. Cawley tells us, then did the storm-tossed dialogues with Chuck not occur either? Why are the doctors talking about the prospects of a (nonexistent) flood before Teddy even comes into the room? And could the inmates be relied upon to execute the physicians’ complex role-playing game? A second viewing left me in the dark about matters that a Shyamalan would have tidied up.

But I did have to admire the way in which Scorsese uses Teddy’s breakdown as an alibi for the mismatched cuts I’ve objected to before. (Some legerdemain with a water glass is particularly clever.) And the ending supplies one further twist that somewhat ennobles the whole loopy contraption.

Cranking it up

Crank 2: High Voltage.

You can argue that Scorsese’s talent was well suited to this project: We don’t notice the plot problems because his stylistic assurance carries us along smoothly. That assurance allows me to raise my final point.

I’ve argued elsewhere, in books and on this site, that Hollywood storytelling techniques have been overhauled in recent decades. Over the last forty years or so, filmmakers have amped up the “continuity style” forged in the 1910s. They have cut faster, sometimes averaging 2-3 seconds per shot across a film. They have relied more heavily on singles (shots of one character), and these singles are often fairly large close-ups. Directors have also embraced extremes in lens lengths—very long lenses (for that perspective-flattening effect) and very wide-angle ones (often yielding flagrant distortions). Filmmakers have also relied a great deal on camera movement, frequently tracking in or out or even circling around the characters as they speak. The basic premises of continuity cinema aren’t violated, but the result is more aggressive visuals. Hence my label “intensified continuity.”

I think that intensified continuity became the new baseline for popular filmmaking both in the US and overseas. Over this style, however, some filmmakers have laid lots of fancy filigree. Many flashy techniques fill our movies. We get slow-motion, fast-motion, reverse-motion, ramping, and freeze-frames. There are brutal jump cuts, ragged shifts between color and monochrome, deliberately awkward framings, abrupt overhead compositions, slippery focus, and jerky handheld shooting. On the soundtrack we get ominous rumblings, metallic crashes, and noisy transitions. The Bourne films and The Hurt Locker (2009) offer moderate examples, but edging toward the extreme you have Crank 2: High Voltage (2009). Here intensified continuity has itself been intensified to a height of frenzied artifice. “Over the top” doesn’t capture it. There is, it seems, no longer a top to go over.

This swaggering style takes classical space and time as its basis—we still have analytical cutting, over-the-shoulder shots, and the like—but it pushes beyond the modest demands of simply laying out dramatic elements for easy comprehension. The intensified approach, itself trying for punch, has been raised to a new level of shock and awe. This trend, I’d speculate, is an escalation of tendencies seen in 1970s-1980s filmmakers like Brian De Palma, Ken Russell, Nicholas Roeg, Ridley Scott, and Scorsese.

Scorsese’s stylistic élan proved enormously influential, I think; Mean Streets is virtually a compendium of the new techniques. But unlike some others, he explored the emerging style in order to probe characters’ feelings and moods. Many of today’s amped-up techniques come off as merely eye candy, or prods for visual arousal, or pieces of narrational subterfuge (as often in De Palma). Scorsese has sought to make these decorative techniques more operatic—perhaps in the tradition of Visconti, Michael Powell, and other filmmakers he admires. The images (and of course the music) swirl around the action, providing cadenzas that bring out feelings which his men often can’t articulate. Sometimes the stylistic accompaniment becomes bombastic, as I think Shutter Island largely is. Yet the finest of Scorsese’s pictures contribute to a rich tradition in which the cinema, normally committed to objective realism, makes palpable what goes on inside us.

Scorsese’s remarks on The Age of Innocence come from a Film Comment interview with Gavin Smith reprinted in Martin Scorsese Interviews, ed. Peter Brunette (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999), 200. For more on Expressionist and Impressionist silent cinema, see our Film History: An Introduction, Chapters 4 and 5. By the end of the 1920s, these tendencies and Soviet Montage were blending into a sort of international style, a development considered in Chapter 8.

Taxi Driver.

PS 24 April: Filmmaker Max Jacoby writes:

I just read your blog entry on Scorsese’s style. You point out the glowing light which appears in some scenes of Bringing out the Dead. That is actually a signature lighting effect of cinematographer Bob Richardson. He has used this before he came into contact with Scorsese. You can already see it in some of the Oliver Stone films that he shot, such as JFK. This glowing effect is achieved by combining an overexposed toplight (several stops over key) with a diffusion filter (such as a White Pro Mist) in front of the lens or a net behind the lens. You can actually see the pattern of the net in question on the close-up of Nic Cage that you picked; it clearly stands out from the out-of-focus highlights in the background.

The net is more than likely a Christian Dior Denier 10 stocking, made of silk. They are very sought after and hard to find nowadays, because Dior stopped making these some years ago and switched to nylon instead. Once that became known, you had plenty of cinematographers invading women’s underwear stores to buy up the last remaining stock!

Max’s point helpfully indicates how a director can give a DP’s preferred choice a particular function. It seems to me that Scorsese’s patterned usage of the glowing white patches creates a significant motif in the movie–especially when it dominates the last shot, always a crucial moment. Thanks to Max for this, and for a followup reference to Eric Rudolph’s article, “Urban Gothic” in American Cinematographer 80, 11 (November 1999), 30-41; available here. In it Richardson discusses the flaring whites I mention in the blog entry.

Back to THE DEPARTED

My first post on Scorsese’s Departed has started a passionate and pretty discerning discussion over on Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog, so I’ve joined in. You can read the thread, including my horrendously long comment, here.