Archive for the 'Directors: Soderbergh' Category

KIMI: She’s here

Kimi (2022).

DB here:

Just when I worried that the solitary-woman-in-peril cycle had ended, along comes Steven Soderbergh’s Kimi on HBO Plus. Following on the fine No Sudden Move from last year, his latest effort shows how an imaginative script (from Friend of the Blog David Koepp), elegant direction, an unpredictable score, and an engagingly eccentric central performance (from Zoë Kravitz) can revivify some classic conventions.

Some critics think that when parodies show up, the genre is on the downturn. The streaming release of The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window (2022) might suggest that the cycle based on The Girl on the Train (2016) and The Woman in the Window (2021) had run its course. But actually, parodies can show up at any point in the life cycle of a genre. The Great K & A Train Robbery (1925) didn’t kill off the western, and Spaceballs (1987) didn’t wipe out space opera. So it’s good to know that the presence of Woman in the House Across the Street etc. doesn’t make a straightforward but sophisticated entry like Kimi any the less sparkling.

It depends on what I’ve called the Eyewitness Plot, and I’ve tried in Revisiting Hollywood to show how that emerged from the flurry of creative activity we find in 1940s studio cinema. Here the protagonist sees what may be a crime and asks the authorities to intervene. There’s enough uncertainty about the incident itself, and about the reliability of the witness, to make the police doubt that there’s been a crime. So the protagonist has to investigate–while becoming a target of violence in turn. Rear Window (1954) is the standard example, but it has many predecessors in fiction, film, and radio, notably The Window (1949). A variant relies not on sight but sound: the protagonist hears something of criminal consequence. That alternative is played out in Sorry, Wrong Number (1948) and, later, The Conversation (1974) and Blow-Out (1981).

Koepp and Soderbergh, both connoisseurs of classic Hollywood, understand the power of locking us into the perceptions of the witness while at the same time keeping us aware of the larger context of the action. Rear Window is exceptionally strict in limiting us to what Jeff sees and hears, but even then there is a telltale moment when we’re given information that would seem to contradict his belief that his neighbor has murdered his wife. More common is a balanced narrration that ties us to what the protagonist knows but occasionally strays away to supply backstory and ancillary information–usually, just enough to foster suspense.

That’s enough setup. Major spoilers follow! If you haven’t seen Kimi yet, visit and return.

She looks and listens

Angela Childs lives in lockdown. Not just the pandemic but a traumatic sexual assault has made her afraid to leave her Seattle loft, and more basically resistant to emotional contact. She works from home for Amygdala, a company promoting an Alexa/Siri gadget called Kimi. Unlike the competitors, which rely on machine learning, Amygdala has an army of monitors that track actual user dialogues with Kimi in order to correct its errors. Angela is a monitor, and on one recording she hears, muffled by music and noise, what seems to be a murder. After cleaning up a dense recording and inducing a more experienced hacker to find the user’s entire log of Kimi conversations, Angela discovers a crucial one that seems to lead up to the crime.

Here the official reluctance to believe the witness takes the form of an Amygdala executive’s demand to listen to the recording. When Angela insists that the FBI be present for the playback, the corporation takes steps to silence her. The second large section of the film consists of a prolonged chase and, back in her loft, a final confrontation with the men who committed the crime.

The film’s opening establishes, as a sort of intrinsic norm, the alternation between the wider view of the crime’s circumstances and Angela’s limited perspective. The first scene sets up Bradley Hasling awaiting Amygdala’s IPO, but worried because he’s paying off someone for suppressing information about an unnamed woman.

With our curiosity aroused, the plot can afford to introduce us to Angela and her routines in a more leisurely way. Without the Hasling scene, this stretch would be mostly character portrayal, but it gains keener interest as we must wonder how Angela’s fate will intersect with his. Glimpses of Angela fussily making her bed, brushing her teeth, and exercising on her bike also serve to illustrate how she activates Kimi for music and for computer access.

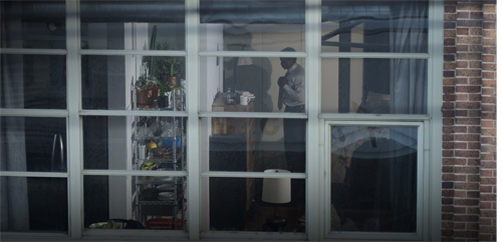

Just as important are the passages of optical POV that show her at her window scanning her street. She looks across at a family in the building opposite, and then looks up and to her left, where she sees the bearded man we’ll learn is called Kevin. He looks back at her.

She swivels her gaze to another window opposite and sees a closed curtain.

Later on the balcony she looks at the window and this time sees Terry, her casual lover, getting ready for work.

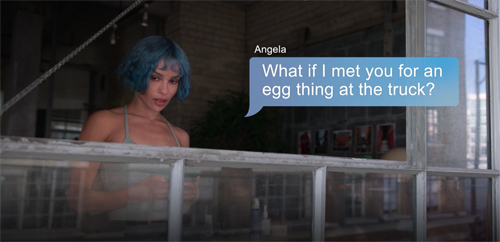

She texts him, and after an external, objective pan shot links the two buildings, she asks Terry if he wants to join her for a breakfast at the food truck down below.

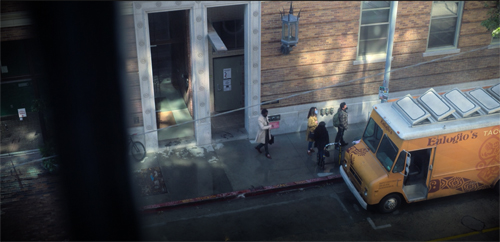

However, she’s afraid to leave the apartment, and her fractured activity is rendered in discordant POV angles. After a shot of her in the shower, we see Terry at the truck, from her usual station point. There’s no lead-in shot of her looking; is she watching from offscreen after the shower, or has the narration worked behind her back, while reminding us of her usual position?

Finally, when she collapses on the floor, unable to leave, we get the same high angle on Terry at the truck, texting her and looking up.

Cut back to her still on the floor. The narration is now operating independent of her vision, but with traces of her viewpoint lingering.

The passage is capped by a shot of her at the window looking down, followed by an optical POV of the food truck, sans Terry.

Another shot of her seals the sequence, but when she pulls away from the window, we get an extra, new angle on her: from outside and above. It’s a fair approximation of what Kevin’s viewpoint on her might be. Yet there’s no shot showing him watching.

The “unclaimed” POV shots that close this scene acknowledge that however much we’re tied to the protagonist’s perceptions, the narration won’t limit us to them–that there is wiggle room to supply extra information, and to imply that our heroine is watched by others. This fluctuating access will become important in the crosscutting that provides the film’s climax.

She flees and fights

The fusion of external viewpoints and subjective ones continues in different ways later. When Angela plays the recordings of the attack, Soderbergh gives us her mental imagery–first as blurred cutaways, then as superimpositions. She’s imagining the assault. Later we’ll learn she has been a rape victim herself.

We’ll later discover that the faces of the murderers are those of the thugs who will pursue her. Yet she hasn’t seen them yet, so she can’t plausibly be visualizing them in the scene.

This is an innovation, I think. In the Forties and since, if these visualized images were to accompany the playback, the faces of the killers would have been indiscernible. Soderbergh is willing to violate plausibility in order to gain economy (introducing us to the thugs) and to continue his initial strategy of rendering subjective experience while also adding information for us.

A milder version of the tactic will be used in the climax, after Angela is captured and lying semi-unconscious in the van. We see her awake and apparently listening to the thugs’ dialogue, while superimpositions suggest the passage of the van through the neighborhood.

Incidentally, these are good examples of the persistence of “Impressionist” cinema techniques from the silent era. Soderbergh had made use of them in Unsane (2018), another film about a woman in peril.

Apart from the prologue showing Hasling’s phone call, the film’s first stretch is confined to Angela’s loft. It’s a classic “bottle” situation, a premise that Koepp is fond of. (Cf. his script for Panic Room, 2002.) It’s Angela’s sympathy for the victim of the crime that propels her out of her bubble into the wider world. Here Zoë Kravitz’s performance takes on a new dimension.

In her loft she’s clipped and brusque, dominating everyone she talks to. Her vulnerability, though, is suggested by her obsessive hand sanitizing. Emphasized by her waving her hands to dry them, it becomes practically a nervous tic.

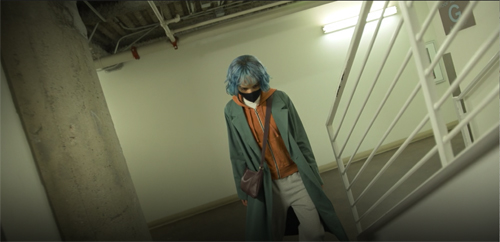

Once outside, she scoots along, arms jammed to her side, head buried in her hoodie, and body as stiff as Max Schreck’s. She tries to be as locked-in outdoors as she is indoors.

Soderberg compensates for her rigidity with camera technique that’s liberated from the confines of her loft. As Manohla Dargis points out in her review, now the film becomes a procession of canted angles and hurtling camera moves, swooping around her and trying to keep up.

Once back in the loft, however, the framing gets poised again and we’re subjected to a precise exercise in suspense. Close-ups and abrupt changes of angle provide exactly what we need to see at each instant.

And things planted quietly in the opening, particularly Angela’s knowledge of building construction, become crucial to her survival. Kimi proves to be a lifesaving sidekick, proving Hitchcock’s dictum concerning Jeff’s use of flashbulbs to save himself in Rear Window: you should use everything you’ve put into your scene.

One nice felicity: You might expect that Terry would turn out to be the “helper male” of so many women-in-peril plots (e.g., the Joseph Cotten character in Gaslight, 1944). Prototypically, this character rescues the protagonist and provides romantic interest for the future. Koepp’s screenplay shrewdly sets Terry up for this role when Angela looks outside during the gang’s siege and sees Terry’s apartment empty.

Later Terry is shown in a street-level, objective shot, walking to Angela’s building. This violation of the intrinsic POV norm suggests an impending rescue. But that prospect is canceled when he stops as if remembering something and turns back.

He does arrive, but too late to help. Terry’s expression as Angela calls 911 is a perfect capstone for the scene. The same wit flashes out of the epilogue, which suggests she’s broken out of her shell, but she still prudently uses sanitizer.

The domestic suspense thriller focused on a female protagonist remains a popular genre of novels. I devoted a chapter to it in my forthcoming book Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. There haven’t been many film adaptations of them since The Woman in the Window, but maybe the neo-Gothic The Girl Before (2021) will unleash more. In the meantime, I’m glad that Koepp and Soderbergh have found ways to give the conventions brisk new life.

David Koepp remarks: “You’re right about the lingering effect of 40s cinema, as you and I have discussed many times. I’d say Sorry, Wrong Number was the direct antecedent here. . . I mean, the party line in Sorry, Wrong Number is basically the Alexa of its time, no?” Interesting in this connection is that the lengthy survey of Angela’s loft in the epilogue shows Kimi no longer there.

Another grace note: KT wondered if the precariously balanced kombucha bottle is psychologically revealing. It turns out to be the consummation of a moment from an earlier Koepp film.

The bottle on the edge of the counter — that was me making good on a setup I did in Secret Window, fifteen years ago. Seriously. There’s a shot in there where Johnny’s character, in a state of high anxiety and agitation, sets a glass down on his kitchen counter hastily, and doesn’t notice it’s only half on the counter. We did seventeen or twenty takes to get exactly the right gravity-defying balance on the edge. It was a pretty literal visual metaphor — you know, he’s on edge.

Thing was, in post-production I realized I had put in a perfect setup, but never paid it off. Why not have the glass fall and smash twenty minutes later, when we’re least expecting it?? Wished I had, never did.

So I used it again in Kimi, but with the (to my mind) required payoff, and at a moment of high tension. So, Angela, in her argument with Terry, is highly agitated, and smacks the bottle down on the counter carelessly, not realizing how close it is to the edge. (The KT hypothesis proves correct!) Angela forgets about it. So do we. Ten minutes later, when we’re all keyed up about something else, SMASH!

Thanks to David for corresponding.

The Hitchcock remark is this: “Here we have a photographer who uses his camera equipment to pry into the back yard, and when he defends himself he also uses his professional equipment, the flashbulbs. I make it a rule to exploit elements that are connected with a character or location. I would feel that I’d been remiss if I hadn’t made maximum use of those elements” (Truffaut/Hitchcock, rev. ed. 1983, 219).

Kimi (2022).

Telling the big story: Network narratives at Venice 2019

The Laundromat (2019).

DB here:

Every now and then I wonder whether network narratives, to revert to the term I coined a while back, have faded from the scene. Although there are some examples earlier in film history, that storytelling model had a sustained burst after Altman popularized it in Nashville (1975). Other filmmakers took it up, especially in the 1990s (Before the Rain, Exotica, Go, Pulp Fiction, etc.) and the 2000s (Babel, Dog Days, Love Actually). I don’t seem to see so many nowadays, and the almost universal loathing greeting Life Itself (2018) might seem to indicate that a tale relying on remote connections and unexpected convergences had run its course.

Surprising, then, to see three items at Venice that rely to a degree on the network narrative format. Each is based on a nonfiction book aiming to reveal the dynamics of a large-scale process. In each film, process becomes a framework for personal stories and converging fates.

Wasps in the Caribbean

Olivier Assayas’s Wasp Network isn’t as far-reaching as the title implies. It concentrates on two couples and one individual caught up in 1990s spying. When René Gonzales, a pilot, defects to Florida, he seems to be seeking freedom and a new life working with Cuban exiles to destabilize Castro’s regime. Branded a traitor, he leaves behind a wife and daughter who must bear social opprobrium. Actually, he is a Cuban agent, part of the “Wasp Network” that will infiltrate the anti-Castro forces.

Another exile, Juan Pablo Roque, works with the Network, but he is also leading a double life–one quite different from René’s. Just as René’s sacrifice wrecks his relation with his family, the headstrong Juan Pablo jeopardizes his relation to his lover Ana Margarita. Both men are linked to Gerardo Hernandez, who coordinates the Network.

As in most spy stories, we’re led to discover double agents and surprise alliances, as well as the conventional emphasis on the personal cost of espionage. As the film goes along, that emphasis becomes stronger; scenes tracing the tactics of the anti-Castro forces (such as invading Cuban airspace to drop leaflets) give way to long confrontations between couples and the efforts of Rene’s wife Olga to unite with him in the US.

Because network plots need to fan out across many characters, filmmakers often break up the linearity of time. In Wasp Network, the reunion of the two major defectors, Juan Pablo and René, is followed by a passionate scene of Olga being defeated by Cuban bureaucracy. Abruptly the plot skips back four years to introduce Gerardo, and his career as a double agent is summarized. A montage, complete with a narrator’s voice-over, links the three men in the years 1990-1992. Then, back in the present, Gerardo meets with Olga to reveal that René is a patriot, not a traitor.

Visually, the film is surprisingly ordinary, I thought, sort of standard TV. If you like over-the-shoulder shot/reverse shot, there’s plenty here for you.

Assayas garnishes his reverse angles with alternating push-ins, a technique that has become a bit hackneyed since John McTiernan’s skillful use of it.

The film compels some interest by virtue of its origins. Based on the FBI case against the “Cuban Five” and the book The Last Soldiers of the Cold War, it employs vintage broadcast news coverage cut in for expository purposes. I had known almost nothing of this historical episode, and thanks to the cooperation of Cuban authorities Assayas benefits from showing a story we Americans seldom see. Still, by concentrating on only a few characters and having them played by Édgar Ramírez, Penélope Cruz, and Gael García Bernal, whose presence demands extensive scenes, the larger dynamic of the Wasp Network fades into the background. Despite its title, maybe it’s only a borderline case of a network narrative.

Coke ZeroZeroZero

ZeroZeroZero is also based on journalistic reportage, in this case Roberto Saviano’s book of the same title. (An earlier Saviano true-crime investigation is the source of the 2008 film Gomorrah, another network narrative.) The subtitle of his book–Look at Cocaine and All You See Is Powder. Look Through Cocaine and You See the World–suggests the vast ambition of his project. From the book Sky, CanalPlus, and Amazon Prime have developed an eight-part series to be broadcast and streamed in 2020.

Since I’m not the world’s biggest TV consumer, I wasn’t interested until I read the presskit, which promises something sweeping.

The series follows the journey of a cocaine shipment from the moment a powerful cartel of Italian criminals decides to buy it until the cargo is delivered and paid for. Through its characters’ stories, the series explains the mechanisms by which the illegal economy becomes part of the legal economy and how both are linked to a ruthless logic of power and control affecting people’s lives and relationships.

The prospect of following a coke-packed container as it passes through various hands appealed to me. I enjoy circulating-object plots like Winchester 73 and The Red Violin, as well as those 1920s Soviet Constructivist “biographies of things” (such as Ilya Ehrenberg’s Life of the Automobile).

ZeroZeroZero, though, isn’t quite that sort of thing. Judging by the first and second episodes, the only ones screened at Venice, this will be more conventional. The plot shifts among dramas within groups of stakeholders in the shipment. We see the power struggle in an Italian crime family, with a son aiming to usurp his grandfather. There’s another family drama in New Orleans, where a ruthless shipping-company owner insists, against his son’s and daughter’s resistance, on booking the cargo. In Mexico, a corrupt special forces sergeant works behind the scenes to assure that the shipment will not be disturbed.

The narration cuts among these storylines until, at the end of episode 2, the cargo embarks on the seas. Doubtless the remaining episodes will ramify into other story lines, but I’d expect at least the Italian and American ones to be on tap throughout–if only to maintain the interest of streamers’ European and US audiences.

The film was directed and co-written by Stefano Sollima, who has done several TV dramas as well as the feature film Sicario–Day of the Soldado. ZeroZeroZero certainly had a higher-gloss look than Wasp Network, with dramatic lighting and elaborate action scenes. One of these, a police attack on the big meeting of the stakeholders, is replayed from different character viewpoints in the two episodes. Like Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero amplifies its expanding network through time-shifting, and this attack is revealed to be a node, a point of convergence among the three main groups of characters. Given current TV’s fascination with scrambled time schemes, I’d expect other nodes and replays to emerge in the course of the series.

Capitals of capital

Eisenstein planned to make a film of Marx’s Capital. He would have used his montage editing methods to survey an economic system–without benefit of individualized protagonists. In The Laundromat Stephen Soderbergh has tried to do something akin to this, but like most filmmakers he’s obliged to personalize his drama (as he did in Traffic and Contagion). Soderbergh has compared the film to Dr. Strangelove, largely because of the need to make a devastating situation entertaining. But I think his film recalls Strangelove as well in its emphasis on villains who get caught up in the insanely complicated system they create.

Mossack Fonseca was a law firm in Panama that specialized in tax evasion. It registered over 300,000 companies, many of which were shell entities that enabled money laundering and fraud. The firm had subsidiaries in the Bahamas, Hong Kong, Switzerland, and other countries. In 2016, German investigative journalists published 11.5 million internal documents known as the Panama Papers, mostly centering on Mossack Fonseca. As the journalists explain:

Clients can buy an anonymous company for as little as USD 1,000. However, at this price it is just an empty shell. For an extra fee, Mossack Fonseca provides a sham director and, if desired, conceals the company’s true shareholder. The result is an offshore company whose true purpose and ownership structure is indecipherable from the outside.

Despite its vast scale, the firm represented at most ten percent of the global market of offshore finagling.

Tax havens and shell companies are more or less legal. What brought down the company was the breach of confidentiality. In addition, the possibility of fraud hovered over the big names revealed as beneficiaries. Politicians throughout Europe and China were named, as were filmmakers Jackie Chan and Pedro Almodóvar. International villains associated with Bashar al-Assad and Vladimir Putin moved money through Mossack Fonseca; a Russian cellist had holdings of $2 billion. After the leaks, the rich couldn’t trust Mossack Fonseca to keep their secrets.

Building on Jake Bernstein’s book Secrecy World, Soderbergh and screenwriter Scott Z. Burns have concocted a sweeping tale of how the rich are very, very, very different from you and me. But in scale, the network they’re surveying dwarfs the Wasps and the voyage of a coke shipment. How do you convey the vastness of an alternative financial system?

The film’s pop-Brechtian mode of presentation will earn comparisons to The Big Short, but here instead of one-off celebrity tutors (Margot Robbie, Anthony Bourdain) we get the chattering rogues themselves, Jürgen Mossack (Gary Oldman) and Ramón Fonseca (Antonio Banderas). Their to-camera accounts of “fairy tales that actually happened” settle into a block construction, five chapters “based on actual secrets.”

The first chapter title, “The Meek Are Screwed,” provides an emblematic case of how the little people are connected with this network of virtual money. Chief among those Meek is Ellen Martin (Meryl Streep), whose husband Joe is drowned when a tour boat capsizes.

Hoping to have her grief assuaged by an insurance settlement, she learns that one isn’t forthcoming because the boat company bought a worthless policy from a shell company. The film’s first two chapters follow her efforts to find someone responsible. She finally tracks down a fraudster named Boncamper, a Mossack Fonseca figurehead who has grown rich (and accumulated two families) simply by signing thousands of documents.

Having shown how the shell-company shuffle affects ordinary folks, the film moves on to the high and mighty. One chapter traces the backstory of the company, another shows how an extraordinarily rich family uses the system to one-up each other, and a final chapter depicts murder among the Chinese plutocracy. The fourth block, illustrating the lesson of “Bribery 101,” is especially juicy in showing a father using bearer bonds to force his daughter to keep silent about his extramarital affair. As Marx and Eisenstein would expect, economic relations seep into personal ones. Bribery is all in the family.

The Laundromat’s breezy, self-righteous impresarios cast a comic tone over everything. Even the murder doesn’t seem awful, considering the victim’s own corruption. Only at the end does indignation emerge in a twist. Ellen, almost forgotten for the last half-hour, reappears in a new guise and takes over the narration from the villains. An agitprop ending reminds us that the capital of money laundering may well be the US, where Nevada, Wyoming, and above all Delaware play a role comparable to the Caribbean. Soderbergh and Burns (who confess to having offshore stashes themselves) end by firmly snagging their American audience in the colossal spiderwebs of global capital.

Nearly every narrative involves a social network of some size, even if it’s only a family. The most thoroughgoing network plots provide us roughly equal attachments to many viewpoints. The film demotes individual protagonists, in favor of revealing x degrees of separation among several individuals. Wasp Network, ZeroZeroZero, and The Laundromat don’t have the complexity of the network narratives of earlier years, but they serve to remind us that the network schema can be tweaked to suit the needs of particular creative projects.

Thanks to Paolo Baratta and Alberto Barbera for another fine festival, and to Peter Cowie for his invitation to participate in the College Cinema program. We also appreciate the kind assistance of Michela Lazzarin and Jasna Zoranovich for helping us before and during our stay.

For more on network narratives, see Chapter 7, “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance,” in Poetics of Cinema. Jeff Smith considers Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood as a network narrative, and earlier entries (such as here and here) develop the idea as well.

To go beyond our Venice 2019 blogs, check out our Instagram page.

ZeroZeroZero (2020).

SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past

Safe Haven; Side Effects.

DB here:

Occasionally someone will ask me how I watch a movie. Here’s a stab at an answer. If the film presents a story, fictional or nonfictional, I try to get engaged by it, as most viewers do. I also try to watch for how the filmmaker shapes sounds and images. Such things are hard to analyze on the fly, but we can at least be shot-conscious. I suppose as well there’s a small part of me asking whether what I’m watching is good or bad. Another part takes notice of what many viewers spot today: the sorts of story roles allotted to women and members of minorities.

At the same time, one module in my head seems to be looking for historical precedents and parallels to what I’m seeing. The purpose isn’t to dismiss current movies with “Aw, this has been done long ago.” Instead, I think I’m looking for ways in which earlier forms and styles are accepted, recast, or rejected by the creative choices being made today.

For instance, as I was watching Safe Haven and Side Effects, I was thinking of the 1940s.

Not that other periods haven’t left their traces. Both movies depend on crosscutting, something that goes back to the 1910s, as does the goal-oriented protagonist. Both rely as well on analytical editing, with Soderbergh in his usual spare way minimizing establishing shots in favor of compact constructive editing. The wobbly handheld shots cropping up in both films hark back to the 1960s and filmmakers’ periodic revival of them. Four-part structure: check. Rule of three: check. And so on.

But what popped out at me was something that I’ve noticed before. Films of the last twenty years or so borrow a lot of storytelling strategies that originated in the 1940s and carried through into the early 1950s.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argued that 1990s Hollywood drew upon this heritage and in some ways pushed it farther. It isn’t just neo-noirs like Reservoir Dogs and Memento that owe a debt to the earlier period. Lots of films in many genres now casually use flashbacks, voice-overs, restricted points of view, multiple protagonists, network narratives, and replays of scenes from different perspectives—all strategies pioneered or consolidated in the 1940s. These techniques have become so accepted a part of mainstream moviemaking that we may forget that a comedy like The Hangover or a prestige drama like The Iron Lady presents fairly elaborate time schemes or tricks of character subjectivity.

We also tend to ignore the sheer eccentricity of the period. The 1940s introduced movies letting a house tell the story or embedding flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks. Characters dreamed things that came true, or realized that they were actually dead. Sometimes dead people narrated the story. All in all, things got pretty strange.

Part of that era’s legacy is the suspense thriller as we know it. I’ll be putting up a web essay on the development of the genre soon, but for now consider these two recent releases as heirs of that tradition. Of course there are big spoilers ahead.

Spooked

Like many 1940s thrillers, Safe Haven centers on a woman in peril. Most often the heroine is trapped in a house, and an unseen force or a ruthless husband is trying to kill or incapacitate her. The prototype is Gaslight (1944), where as often happens, the wife is rescued by a “helper male,” a romantic alternative to the husband. Variants of this plot include The Spiral Staircase (1946) and The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947). This sort of domestic thriller, sometimes called a Gothic, tends to fill household spaces and everyday routines with vague threats.

Instead of confining its protagonist, Safe Haven builds its plot around a woman who has left home behind. Fleeing an abusive marriage, Erin arrives in a North Carolina town and slowly enters a love affair with Alex, a widower who runs a convenience store. Meanwhile her husband Kevin tries to track her down. The fairly conventional budding romance, as Erin joins Alex and his kids in forming a new family, is threatened by the prospect of Kevin finding her and dragging her back home. As a policeman, Kevin has unusual forces at his disposal: a crucial turning point is his putting out an unauthorized wanted poster. Not only does this endanger Erin’s new identity, but when Alex sees the poster, he breaks off their affair.

On-the-run plots are usually the province of male-centered thrillers like The 39 Steps and North by Northwest. It isn’t unknown, though, to make the woman a moving target. One of my favorites is Double Jeopardy (1999), in which Ashley Judd plays a wife convicted of her husband’s murder. When she learns that he faked his death, she realizes that she can’t be tried again for killing him. Released on parole, she pursues him, while her tenacious parole officer pursues her. An older example is Woman in Hiding (1949), in which Ida Lupino plays a wife who is supposedly murdered by her husband. Actually, she eludes death and tries to flee him, but he, discovering she’s still alive, catches up with her on a hotel staircase.

In such thrillers, there are two common ways you can generate suspense. Both depend on range of knowledge, as Alfred Hitchcock pointed out in 1947.

The author may let both reader and character share the knowledge of the nature of the dangers which threaten. . . . Sometimes, however, the reader alone may realize that peril is in the offing, and watch the characters moving to meet it in blissful ignorance and disquieting unconcern.

That is, the narration can attach us to a character and limit our knowledge to what she knows. Examples of this are Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941), which quite strictly confine us to the heroine’s range of knowledge.

Safe Haven, like Woman in Hiding, takes the alternative option: omniscience, or what Hitchcock calls “sharing the knowledge of the dangers.” Crosscut scenes show Erin in Southport while Kevin follows her trail. Other crosscut scenes introduce us to Alex’s problems of raising his kids and grieving for his wife.

As Erin gradually settles into the community, we know that Kevin is closing in. He arrives during a town celebration, and the crosscutting becomes tighter. Thanks to Kevin, the store catches fire and endangers Alex’s daughter, while Kevin drunkenly wrestles with Erin at gunpoint.

Suspense and mystery go hand in hand, and suspense films have a habit of suppressing information about past events. Woman in Hiding begins with the wife’s car plunging into the river; later we get a flashback explaining what led up to the accident. Safe Haven begins with a black-haired woman hysterically running out of a house and taking refuge with a neighbor. What has led to this? The woman, now a blonde, then boards a bus, while we see a man with police credentials questioning witnesses and stopping other buses.

The plot is organized so that we don’t know for quite some time why Erin is being pursued by this exceptionally zealous detective. And some fragmentary flashbacks, mostly in the form of dreams (a favorite 40s device), hint that she has killed a man. Gradually, however, there are hints that this cop isn’t what he seems. Not until the end of the third part (circa 80:00) do we learn from a full flashback that the cop is her husband. Kevin is a crazed alcoholic who began to strangle Erin one evening; she stabbed him and fled her home. The teasing flashbacks, along with the suggestion that Kevin’s pursuit is an official inquiry rather than a private vendetta, misled us. What we saw at the start was Erin escaping from an abusive marriage.

A lower-key form of delayed and distributed exposition involves Alex and his kids. Instead of filling us in immediately on Alex’s life with his wife, we learn of their married life gradually. After Alex has fallen in love with Erin, he retreats to a room kept in memory of his dead wife. He riffles through letters she left behind, to be given to Josh and Lexie when they grow up. Later, Alex abandons Erin because of the wanted poster, and he retreats to his wife’s room, where he has a change of heart and goes to bring her into the home.

Why the change of heart? An unusual aspect of Safe House is the injection of, ah, otherworldly intervention. While living in her cabin, Erin meets a neighbor, Jo, who encourages her to get to know Alex. In the epilogue, Alex gives Erin one of the letters from his wife’s desk, labeled simply, “To Her.” It’s a sympathetic message expressing the wife’s support for the next woman to be wife and mother to her family. The picture inside is of Jo. Earlier, in the sacred space of Jo’s room, Alex seems to grasp that he has to reunite with Erin. At the climax, Erin, dreams that Jo is warning her that Kevin has caught up with her. As angel, ghost, or spirit—you choose—Jo has brought everyone together.

Reviewers, in this cynical age, scoffed at this device. I didn’t mind it because I liked its tie to tradition. Ghosts and angels have haunted American cinema from the start, but in the 1940s they played very prominent roles—not just in comedies like Topper Returns (1941) but in dramas. Beyond Tomorrow (1940), Our Town (1940), Happy Land (1943), A Guy Named Joe (1943), The Uninvited (1944), It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), and many other films unashamedly introduced supernatural beings as moral guides to the living. True, those films build their spooks into the premises of the plot early on, while Safe Haven saves its for a Big Reveal. But after The Sixth Sense (1999), this sort of twist shouldn’t seem too upsetting. (A second viewing reveals that Jo is unnaturally disturbed when it looks like Erin won’t bond with the family, and a few lines of dialogue take on new meanings when you know that Jo is dead.) Perhaps the gimmick seems wimpier when it’s invoked in a romantic thriller than in a masculine investigation plot.

Recommended dosage

Steven Soderbergh is one of our most exploratory directors, a filmmaker who tries different things without making a big deal about it. He’s also a cinephile who, like Cameron Crowe, admires and quietly adapts classic studio traditions. He turns out lots of movies, a habit reminiscent of the contract director of yore.

I was skeptical of his pastiche The Good German (2006), but I do admire his compact, unfussy direction, as I mentioned here. I’m a big fan of Out of Sight (1998), and I think his last batch of films, from Contagion (2011) through Haywire (2012) and Magic Mike (2012), shows him to be a director whose every project is solid and intriguing. It’s a pity he’s announced his retirement after the upcoming Liberace project.

I doubt that in Safe Haven Lasse Hallström was consciously channeling 1940s suspense thrillers, but it seems likely that Soderbergh was trying his hand at something deliberately Hitchcockian. (Reviewers needed no nudging to make the comparison.) Beyond comparisons with the Master of Suspense, Side Effects’s debt extends to two plot patterns of the 1940-early 1950s that Scott Z. Burns’s script ingeniously combines.

The first is what I call the Crazy Lady plot. The Snake Pit (1948) is probably the clearest example, but there are many others, including Bewitched (1945), Dark Mirror (1946), The Locket (1946), Shock (1946), Possessed (1947), and Whirlpool (1950). The plot pattern can be found in literary thrillers too, such as Margaret Millar’s The Iron Gates (1945) and John Franklin Bardin’s fine Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948). Hitchcock didn’t tackle a Crazy Lady plot until Marnie (1964), but in the 1940s he tried a Crazy Gentleman variation in Spellbound (1945).

In such films, the woman is the mystery. What is wrong with her? Why do her problems have such horrible consequences for her and others? Often the woman displays an abnormal division in her mind: the prospect of a split personality is never far off. The key factor is that her behavior is inconsistent. A rich woman shoplifts (Whirlpool), a sweet girl fatally stabs her fiancé (Bewitched). Accordingly, only a psychoanalyst can probe the sick woman’s behavior and track down the founding trauma, typically something that happened in childhood. A crucial convention is the scene in which the woman breaks through and realizes what ails her, as in this moment from Whirlpool. It’s typical of this plot that therapeutic dialogue is often paralleled by police questioning.

Side Effects gives the Crazy Lady’s mental problems a modern spin. Emily is suffering from depression, and her husband Martin’s recent release from prison hasn’t helped her recover. After ramming her car into a parking-garage wall, she’s cared for by Jonathan, a hospital psychiatrist also in private practice. He starts her on antidepressants, eventually giving her one recommended by Emily’s previous psychiatrist, Victoria. This seems to help, although it induces Emily to sleepwalk. While she’s apparently sleepwalking, she stabs Martin to death.

Now Jonathan is in a bind. If the drug Ablixa has been misprescribed, Jonathan is responsible for Martin’s death and Emily’s fate. Jonathan defends Emily and his testimony helps win a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. He continues to supervise her recovery while his career collapses. His patients abandon him, his partners cast him out of their business, and he’s dropped from a lucrative experiment. He’s also being investigated by his professional association.

In other words, Jonathan is now fulfilling a second 1940s plot pattern: The innocent man trapped by circumstance. He might be a murder suspect (Stranger on the Third Floor, 1940; Phantom Lady, 1944; The Big Clock, 1948) or an ordinary guy dropped into international intrigue (Journey into Fear, 1943; The Ministry of Fear, 1944). Side Effects combines this noirish convention with the Crazy Lady plot. It turns out that Emily and Victoria have conspired to set up Martin’s death. Emily actually hates her husband, and she’s learned enough from his insider-trading schemes to understand that a scandal could drive down Ablixa’s stock price. She and Victoria, who have become lovers, can make millions as a result of the murder.

Yet suspecting all this doesn’t help Jonathan. Emily can’t be tried again, and as Jonathan begins to grasp their scheme, Victoria draws the net tighter around him. She sends his wife faked photos suggesting that he and Emily have had an affair.

In 1947, novelist Mitchell Wilson pointed out an important convention of the thriller. He claimed that the defining feature of the genre was a fear felt by the protagonist that is communicated to the reader: the protagonist is in continual danger. But when the threat reaches its peak, the worm must turn.

The framework of the suspense story is the continual struggle of the frightened protagonist to fight back and save himself in spite of his pervading anxiety, and in this respect he is truly heroic. The action of the story does not consist in mere activity, but in the hero’s change of mood in response to changing circumstances.

Jonathan’s desperation leads him to concoct a scam of his own. Since Emily is in prison and can’t communicate with Victoria, he is able to play them off against one another. Holding a physician’s control over Emily, he can convince her to double-cross Victoria and unmask her. Then he double-crosses Emily and consigns her to the asylum while returning to his family.

Again, I’ve ironed out the ups and downs of the film in order to lay out the plot’s design. In the actual telling, we’re attached first to Emily and then more closely to Jonathan. The overall pattern resembles that of Whirlpool, which concentrates first on the way the wife’s kleptomania draws her to the sinister therapist Korvo, and then shifts to the investigation undertaken by the police and her husband, a psychoanalyst. (Whirlpool, like Side Effects, centers on dueling shrinks.)

Here the Crazy Lady premise is a masquerade, and Soderbergh “plays fair” with us about it. The 1940s films rely on mental subjectivity—voice-over inner monologues, exaggerated sound effects, hallucinations, dream imagery—in order to show that the protagonist is truly wacko. Side Effects presents Emily objectively, relying on somber color schemes, top lighting, and Rooney Mara’s morose demeanor to suggest a young woman struggling against depression.

From the outside we watch Emily’s glum visits to Martin in prison, their frustrated sex when he gets out, her impassive crashing of her car, her confiding in her boss, and her breakdown at a cocktail party. There are a few optical POV shots, but those are justified as Emily’s numb stare–although Soderbergh does sneak past us a POV shot that, because of distorting glass, might seem to be projecting Emily’s state of mind expressionistically. (See above.) Virtually everything we see suggests a woman losing control, so that when Emily perks up after going on Ablixa, we, like Jonathan and Martin, think she’s recovering.

Safe Haven leads us to jump to a conclusion—that the cop pursuing Erin is doing so legitimately—only to rescind that by filling out the teasing fragmentary flashbacks. Side Effects does something similar, but through simple ellipsis. The plot lets us think that Emily is genuinely depressed by skipping over things it could have shown, such as her fake vomiting or her dumping the prescription pills down the toilet. Only at the climax, when Jonathan wrings the truth from Emily, do we get subjective imagery. There are artificially sun-sprayed flashbacks of her days with Martin just before his arrest, as well as glimpses of her therapy with Victoria, followed by replays of the suicide attempts, now revealed as faked.

The 1940s popularized this sort of filling-in flashback, in which a replay shows items that were left out of an earlier presentation. The most famous example is the return to the opening of Mildred Pierce (1945). Now as then, we can’t completely trust a thriller’s narration. There are mysteries in the story, but there are also mysteries in the storytelling. No matter how much a thriller seems to tell us, key information is usually held back, and the suppression won’t always be signaled. To get Rumsfeldian: there are always known unknowns, but thrillers trade in unknown unknowns, data we didn’t realize were there.

There’s a lot more to say about these movies. For example, both trade on a premise common to the 1940s and American movies thereafter. Call it the Margaritaville Rule: There’s a woman to blame. Erin brings calamity to Southport and trauma to her would-be family, and Jonathan’s travails are the result of two scheming women, seconded by a hard-edged wife who won’t hear out his explanations.

Moreover, I hope it’s clear that I don’t think these two recent releases are merely cloning 1940s conventions. They incorporate subjects and themes of our time, like spousal abuse and the insidious power of Big Pharma. They exhibit some innovative plotting, such as the revelation of a guiding spirit in Safe Haven and the combination of Crazy Lady premises with the Cornered Innocent in Side Effects. And Soderbergh’s offers an exercise in crisp direction, from its conventional opening shot to its grimly symmetrical closing one.

My point is simple: However new our films may seem, whether they’re accomplished (Side Effects) or banal (Safe Haven), in important respects they’re continuing traditions that go back decades.

Why then, you may ask, do so many academics and journalists insist that classical cinematic storytelling is dead? Why do they so resolutely ignore the evidence of continuity between today’s films and those that went before? That’s a mystery I can’t solve.

Hitchcock’s remark about the range of knowledge and suspense comes from “Introduction: The Quality of Suspense,” Alfred Hitchcock’s Fireside Book of Suspense (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1947), viii. Mitchell Wilson’s remarks on fighting back are in “The Suspense Story,” The Writer 60, 1(January 1947), 16. His novel None So Blind (1945) became the Renoir film Woman on the Beach (1947).

The idea of the “helper male” in the Gothic is developed by Diane Waldman in “’At last I can tell it to someone!’: Feminine Point of View and Subjectivity in the Gothic Romance Film of the 1940s,” Cinema Journal 23,2 (Winter 1984), 29-40.

For more background on the 1940s thriller, see the web essay, “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense” and this blog entry. Another blog entry discusses replays in 1940s and 1950s American film. For more arguments about the debts of today’s films to studio Hollywood, see The Way Hollywood Tells It and other entries on this site. I analyze the duplicitous opening of Mildred Pierce, along with its revelatory replay, in this entry and its accompanying video.

Today’s entry neglects another important component of Side Effects: the music. For that, see Roger Ebert’s acute review. Expressive scores are, needless to say, central to 40s thrillers too.

Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website supplies a great deal of information about the mystery genre.

Side Effects.

P. S. 24 March 2013: Thanks to Gabe Klinger for correcting a dumb date mistake!

Nolan vs. Nolan

DB here:

Paul Thomas Anderson, the Wachowskis, David Fincher, Darren Aronofsky, and other directors who made breakthrough films at the end of the 1990s have managed to win either popular or critical success, and sometimes both. None, though, has had as meteoric a career as Christopher Nolan.

His films have earned $3.3 billion at the global box office, and the total is still swelling. On IMDB’s Top 250 list, as populist a measure as we can find, The Dark Knight (2008) is ranked number 8 with over 750,000 votes, while Inception (2010), at number 14, earned nearly 600,000. The Dark Knight Rises (2012), on release for less than a month, is already ranked at number 18. Remarkably, many critics have lined up as well, embracing both Nolan’s more offbeat productions, like Memento (2000) and The Prestige (2006), and his blockbusters. Nolan is now routinely considered one of the most accomplished living filmmakers.

Yet many critics fiercely dislike his work. They regard it as intellectually shallow, dramatically clumsy, and technically inept. As far as I can tell, no popular filmmaker’s work of recent years has received the sort of harsh, meticulous dissection Jim Emerson and A. D. Jameson have applied to Nolan’s films. (See the codicil for numerous links.) People who shrug at continuity errors and patchy plots in ordinary productions have dwelt on them in Nolan’s movies. The attack is probably a response to his elevated reputation. Having been raised so high, he has farther to fall.

I have only a welterweight dog in this fight, because I admire some of Nolan’s films, for reasons I hope to make clear later. Nolan is, I think all parties will agree, an innovative filmmaker. Some will argue that his innovations are feeble, but that’s beside my point here. His career offers us an occasion to think through some issues about creativity and innovation in popular cinema.

Four dimensions, at least

First, let’s ask: How can a filmmaker innovate? I see four primary ways.

You can innovate by tackling new subject matter. This is a common strategy of documentary cinema, which often shows us a slice of our world we haven’t seen or even known about before—from Spellbound to Vernon, Florida.

You can also innovate by developing new themes. The 1950s “liberal Westerns” substituted a brotherhood-of-man theme for the Manifest-Destiny theme that had driven earlier Western movies. The subject matter, the conquest of the West by white settlers and a national government, was given a different thematic coloring (which of course varied from film to film). Science fiction films were once dominated by conceptions of future technology as sleek and clean, but after Alien, we saw that the future might be just as dilapidated as the present.

Apart from subject or theme, you can innovate by trying out new formal strategies. This option is evident in fictional narrative cinema, where plot structure or narration can be treated in fresh ways. Many entries on this blog have charted possible formal innovations, such as having a house narrate the story action, or arranging the plot so as to create contradictory chains of events. Documentaries have experimented with a film’s overall form as well, of course, as The Thin Blue Line and Man with a Movie Camera. Stan Brakhage’s creation of “lyrical cinema” would be an example of formal innovation in avant-garde cinema.

Finally, you can innovate at the level of style—the patterning of film technique, the audiovisual texture of the movie. A clear example would be Godard’s jump cuts in A Bout de souffle, but new techniques of shooting, staging, framing, lighting, color design, and sound work would also count. In Cloverfield and Chronicle, the first-person camera technique is applied, in different ways, to a science-fiction tale. Often, technological changes trigger stylistic innovation, as with the Dolby ATMOS system now encouraging filmmakers to create sound effects that seem to be occurring above our heads.

I see other means of innovation—for instance, stunt casting, or new marketing strategies—but these four offer an initial point of departure. How then might we capture Nolan’s cinematic innovations?

Style without style

Well, on the whole they aren’t stylistic. Those who consider him a weak stylist can find evidence in Insomnia (2002), his first studio film. Spoilers ahead.

A Los Angeles detective and his partner come to an Alaskan town to investigate the murder of a teenage girl. While chasing a suspect in the fog, Dormer shoots his partner Hap and then lies about it, trying to pin the killing on the suspect. But the suspect, a famous author who did kill the girl, knows what really happened. He pressures Dormer to cover for both of them by framing the girl’s boyfriend. Meanwhile, Dormer is undergoing scrutiny by Ellie, a young officer who idolizes him but who must investigate Hap’s death. And throughout it all, Dormer becomes bleary and disoriented because, the twenty-four-hour daylight won’t let him sleep. (His name seems a screenwriter’s conceit, invoking dormir, to sleep.)

Nolan said at the time that what interested him in the script—already bought by Warners and offered to him after Memento—was the prospect of character subjectivity.

A big part of my interest in filmmaking is an interest in showing the audience a story through a character’s point of view. It’s interesting to try and do that and maintain a relatively natural look.

He wanted, as he says on the DVD commentary, to keep the audience in Dormer’s head. Having already done that to an extent in Memento, he saw it as a logical way of presenting Dormer’s slow crackup.

But how to go subjective? Nolan chose to break up scenes with fragmentary flashes of the crime and of clues—painted nails, a necklace. Early in the film, Dormer is studying Kay Connell’s corpse, and we get flashes of the murder and its grisly aftermath, the killer sprucing up the corpse.

At first it seems that Dormer intuits what happened by noticing clues on Kay’s body. But the film’s credits started with similar glimpses of the killing, as if from the killer’s point of view, and there’s an ambiguity about whether the interpolated images later are Dormer’s imaginative reconstruction, or reminders of the killer’s vision—establishing that uneasy link of cop and crook that is a staple of the crime film.

Similarly, abrupt cutting is used to introduce a cluster of images that gets clarified in the course of the film. At the start, we see blood seeping through threads, and then shots of hands carefully depositing blood on a fabric (above). Then we see shots of Dormer, awaking jerkily while flying in to the crime scene. Are these enigmatic images more extracts from the crime, or are they something else? We’ll learn in the course of the film that these are flashbacks to Dormer’s framing of another suspect back in Los Angeles. Once again, these images get anchored as more or less subjective, and they echo the killer’s patient tidying up.

Nolan’s reliance on rapid cutting in these passages is typical of his style generally. Insomia has over 3400 shots in its 111 minutes, making the average shot just under two seconds long. Rapid editing like this can suit bursts of mental imagery, but it’s hard to sustain in meat-and-potatoes dialogue scenes. Yet Nolan tries.

In lectures I’ve used the scene in which Dormer and Hap arrive at the Alaskan police station as an example of the over-busy tempo that can come along with a style based in “intensified continuity.” In a seventy-second scene, there are 39 shots, so the average is about 1.8 seconds—a pace typical of the film and of the intensified approach generally.

Apart from one exterior long-shot of the police station and four inserts of hands, the characters’ interplay is captured almost entirely in singles—that is, shots of only one actor. Out of the 34 shots of actors’ faces and upper bodies, 24 are singles. Most of these serve to pick up individual lines of dialogue or characters’ reactions to other lines. The singles are shot with telephoto lenses, a choice exemplifying what I called the tendency toward “bipolar” lens lengths in intensified continuity–that is, either very long lenses or fairly wide-angle ones.

Fast cutting like this need not break up traditional spatial orientation. In this scene, there are a couple of bumps in the eyeline-matching, but basically continuity principles are respected. As Nolan explains on the DVD commentary, he tried to anchor the axis of action, or 180-degree line, around Dormer/Pacino, so the eyelines were consistent with his position, and that’s usually the case here.

I can’t illustrate all the shots here, but despite its more or less cogent continuity, the scene seems to me choppy, uneconomical, and fairly perfunctory in its stylistic handling. Nolan makes no effort to move the actors around the set in a way that would underscore the dramatic development. Because of the rapid editing, characters’ lines and gestures are cut off or unprepared for. There is no effort to design each shot, à la Hitchcock, to fit the line or reaction of the actor. Most shots are excerpted from full takes, all from the same setup. The most obvious example is the setup that pans to show Dormer as he comes in, stops, and reacts to the conversation. Thirteen shots are taken from that setup (not necessarily the same full take, of course, as the last frame here shows).

In Nolan’s recent films, this avoidance of tightly designed compositions may be encouraged further because he’s shooting in both the 1.43 Imax ratio and the 2.40 anamorphic one. There remains a general tendency toward loose, roughly centered framings.

Somebody is sure to reply that the nervous editing is aiming to express Dormer’s anxiety about the investigation into his career. But that would be too broad an explanation. On the same grounds, every awkwardly-edited film could be said to be expressing dramatic tensions within or among the characters. Moreover, even when Dormer’s not present, the same choppy cutting is on display.

Consider the 23 shots showing Ellie greeting Dormer and Hap as they get off the plane. Again we have full production takes broken up into brief phases of action (it takes five shots to get Dormer out of the plane), with an almost arbitrarily succession of shot scales. When Ellie leaves her vehicle to go out on the pier, the action is presented in nine shots.

We can imagine a simpler presentation—perhaps after an establishing shot, we track with Ellie down along the dock (so we can see her smiling anticipation), then pan with her walking leftward into a framing that prepares for the plane hatch to open. Arguably, the need to show off production values—the vast natural landscape, the swooping plane descending—pressed Nolan to include some of the extra shots. They don’t do much dramatically, and the strange cut back to an extreme long-shot (to cover the change to a new angle on Ellie?) may negate whatever affinity with her that the closer shots aim to build up.

Swedish sleeplessness

Magic Mike.

Want an up-to-date comparison? Steven Soderbergh’s Magic Mike has a quiet, clean style that conveys each story point without fanfare. Soderbergh saves his singles for major moments and drops back for long-running master shots when character interaction counts. His cuts are just that; they trim fat. He doesn’t resort to those short-lived push-in camera movements that Nolan seems addicted to. He doesn’t waste time with filler shots of people going in and out of buildings, or aerial views of a cityscape. Soderbergh can provide an unfussy 70s-ish telephoto long take of Mike and Brooke walking along a pier and settling down at a picnic table in front of a Go-Kart track while her brother Adam materializes in the distance. In a single year, with Contagion, Haywire, and Magic Mike, Soderbergh has confirmed himself as our master of the intelligent midrange picture. To anyone who cares to watch, these movies give lessons in discreet, compact direction.

For a more pertinent contrast case, we can go back Insomnia’s source, the 1997 Norwegian film of the same name written and directed by Erik Skjoldbjaerg. Here a Swedish detective, vaguely under suspicion for an infraction of duty, comes to a town on the Arctic Circle for a murder investigation. The plot is roughly similar in its premise, but the working out is quite different, and I can’t do justice to it here. Let me mention just two points of contrast.

First, the cutting is less jagged. Skjoldbjaerg’s film comes in at ninety-seven minutes, about fifteen minutes shorter than Nolan’s, and its cutting rate is much slower, around 5.4 seconds. That means that many passages are built out of sustained shots, particularly ones showing the detective Jonas Engström walking or sitting in a brooding, self-contained silence. Also, this version finds ways to convey several bits of information concisely, in carefully designed shots. For a straightforward example: We see Engstrom’s eyes open, as he’s unable to sleep, and then he lifts his head. Rack focus to the clock behind him.

Nolan uses several shots to get across a comparable point.

As for subjectivity, Skoldbjaerg is just as keen to get us inside his detective’s head as Nolan is. At times he uses the sort of flash-cutting Nolan employs, so we get fragmentary reminders of the fog-clouded shooting. But Skoldbjaerg doesn’t tease us with unattributed inserts (Nolan’s flashbacks to Dormer’s framing of a suspect), and he never suggests, via images of the murder and its cleanup, that his detective can imagine the crime concretely. Instead, Skoldbjaerg often evokes his character’s unease through camera movements that upset our sense of his spatial location. The camera shows Engstrom striding into a room…and then swivels rightward to show him in his original location, as if he’s sneaked around behind our back.

Then Engstrom turns, and we hear a footstep. Cut to a shot showing that the sound is made by him, walking in another room.

I’m not going to suggest that Skoldbaerg innovates more radically than Nolan does, though most viewers probably are more startled by these devices than by Nolan’s. I think that the original Insomnia’s stylistic gamesmanship owes something to other precedents, going back to Dreyer’s Vampyr. What I find more interesting is that Nolan had available the prior example of these strategies from his Nordic source, and he still chose to go with the more conventional, cutting-based options.

The editing-driven, somewhat catch-as-catch-can approach to staging and shooting is clearly Nolan’s preference for many projects. He doesn’t prepare shot lists, and he storyboards only the big action sequences. As his DP Wally Pfister remarks, “What I do is not complicated.” Comparing their production method to documentary filming, he adds: “A lot of the spirit of it is: How fast can we shoot this?”

Throwing it against the wall

We can find this loose shooting and brusque editing in most of Nolan’s films, and so they don’t seem to me to display innovative, or particularly skilful, visual style. I’m going to assume that his strengths aren’t in the choice of subjects either, since genre considerations have kept him to superheroics and psychological crime and mystery. I think his chief areas of innovation lie in theme and form.

The thematic dimension is easy to see. There’s the issue of uncertain identity, which becomes explicit in Memento and the Batman films. The lost-woman motif, from Leonard’s wife in Memento to Rachel in the two late Batman movies, gives Nolan’s films the recurring theme of vengeance, as well as the romantic one of the man doomed to solitude and unhappiness, always grieving. If this almost obsessive circling around personal identity and the loss of wife or lover carries emotional conviction, it owes a good deal to the performances of Guy Pearce, Hugh Jackman, Christian Bale, and Leonardo DiCaprio, who put some flesh on Nolan’s somewhat schematic situations.

You can argue that these psychological themes aren’t especially original, especially in mystery-based plots, but the Batman films offer something fresher. The Dark Knight trilogy has attracted attention for its willingness to suggest real-world resonance in comic-book material. Umberto Eco once objected that Superman, who has the power to redirect rivers, prevent asteroid collisions, and expose political corruption, devotes too much of his time to thwarting bank robbers. Nolan and his colleagues have sought to answer Eco’s charge by imbuing the usual string of heists, fights, chases, explosions, kidnappings, ticking bombs, and pistols-to-the-head with sociopolitical gravitas. The Dark Knight invokes ideas about terrorism, torture, surveillance, and the need to keep the public in the dark about its heroes. Something similar has happened with The Dark Knight Rises, leaving commentators to puzzle out what it’s saying about financial manipulation, class inequities, and the 99 percent/ 1 percent debate.

Nolan and his collaborators are doubtless doing something ambitious in giving the superhero genre a new weightiness. Yet I found The Dark Knight Rises, like its predecessor, unable to bear the burden. It seemed to me at once pretentious and confused in a manner typical of Hollywood’s traditional handling of topical themes.

The confusion comes into focus when journalists, needing an angle on this week’s release, look for a coherent reflection of that elusive, probably imaginary zeitgeist. I think that most popular films don’t capture the spirit of the time, assuming such a thing exists, but simply opportunistically stitch together whatever lies to hand. Let me recycle what I wrote four years ago.

I remember walking out of Patton (1970) with a hippie friend who loved it. He claimed that it showed how vicious the military was, by portraying a hero as an egotistical nutcase. That wasn’t the reading offered by a veteran I once talked to, who considered the film a tribute to a great warrior.

It was then I began to suspect that Hollywood movies are usually strategically ambiguous about politics. You can read them in a lot of different ways, and that ambivalence is more or less deliberate.

A Hollywood film tends to pose sharp moral polarities and then fuzz or fudge or rush past settling them. For instance, take The Bourne Ultimatum: Yes, the espionage system is corrupt, but there is one honorable agent who will leak the information, and the press will expose it all, and the malefactors will be jailed. This tactic hasn’t had a great track record in real life.

The constitutive ambiguity of Hollywood movies helpfully disarms criticisms from interest groups (“Look at the positive points we put in”). It also gives the film an air of moral seriousness (“See, things aren’t simple; there are gray areas”). . . .

I’m not saying that films can’t carry an intentional message. Bryan Singer and Ian McKellen claim the X-Men series criticizes prejudice against gays and minorities. Nor am I saying that an ambivalent film comes from its makers delicately implanting counterbalancing clues. Sometimes they probably do that. More often, I think, filmmakers pluck out bits of cultural flotsam opportunistically, stirring it all together and offering it up to see if we like the taste. It’s in filmmakers’ interests to push a lot of our buttons without worrying whether what comes out is a coherent intellectual position. Patton grabbed people and got them talking, and that was enough to create a cultural event. Ditto The Dark Knight.

Since I wrote that, Nolan has confirmed my hunch. He says of the new Batman movie:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. . . . We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story.

Just to be clear, I don’t think the just-telling-a-story alibi is bulletproof. The cultural mix on display in a movie can still exclude certain ideological possibilities, or frame the materials in ways that slant how spectators take them up. My point is only that we ought not to expect popular movies, or indeed many movies, to offer crisp, transparent visions of politics or society. Thematic murkiness and confusion are the norm, and the movie’s inconsistencies may reflect nothing more than the makers’ adroit scavenging.

Subjectivity and crosscutting

Nolan’s innovations seem strongest in the realm of narrative form. He’s fascinated by unusual storytelling strategies. Those aren’t developed at full stretch in Insomnia or the Dark Knight trilogy, but other films put them on display.

One way to capture his formal ambitions, I think, is to see them as an effort to reconcile character subjectivity with large-scale crosscutting. Nolan has pointed out his keen interest in both strategies. But on the face of it, they’re opposed. Techniques of subjectivity plunge us into what one character perceives or feels or thinks. Crosscutting typically creates much more unrestricted field of view, shifting us from person to person, place to place. One is intensive, the other expansive; one is a local effect, the other becomes the basis of the film’s enveloping architecture.

The Batman trilogy has plenty of crosscutting, but as far as I can tell, subjectivity takes a back seat. Nolan’s first two films reconcile subjectivity and crosscutting in more unusual ways. Following takes a linear story, breaks it into four stretches, and then intercuts them. But instead of expanding our range of knowledge to many characters, nearly all the sections are confined to what happens to one protagonist, and they’re presented as his recounted memories in a Q & A situation.

Likewise, Memento confines us to a single protagonist and skips between his memories and immediate experiences. Again what might be a single, linear timeline is split, but then one series of incidents is presented as moving chronologically while another is presented in reverse order. Again, the competing time trajectories aren’t presented as large blocks but are fairly swiftly crosscut.

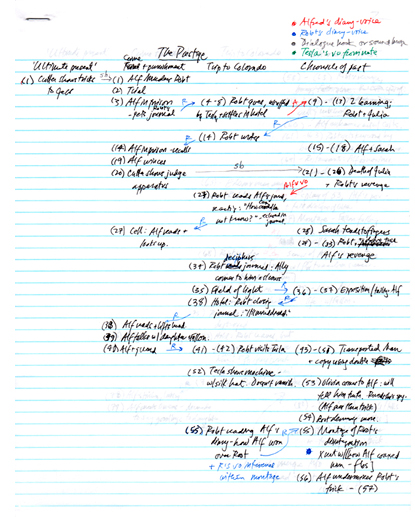

In The Prestige, dual protagonists, both with a secret, take over the story, but the presentation remains steeped in subjectivity. Now much of the action is filtered through each magician’s notebook of jottings and recollections, translated into voice-over commentary. One character may be reading another’s notebook in which the writer reports reading the first character’s notebook! And of course these tales-within-tales are intercut, with one man’s frame story alternating with the other’s past experience. You can work it all out diagrammatically, as I tried to do in my notes (on right).

In The Prestige, dual protagonists, both with a secret, take over the story, but the presentation remains steeped in subjectivity. Now much of the action is filtered through each magician’s notebook of jottings and recollections, translated into voice-over commentary. One character may be reading another’s notebook in which the writer reports reading the first character’s notebook! And of course these tales-within-tales are intercut, with one man’s frame story alternating with the other’s past experience. You can work it all out diagrammatically, as I tried to do in my notes (on right).

With Inception, subjectivity takes the shape of dreaming, and the crosscutting is now among layers of dreams. The embedding that we find in The Prestige is now carried to an extreme; in the long, climactic final sequence a group dream frames another dream which frames another, and so on, to five levels. Once again, these all get intercut (although Nolan wisely refrains from reminding us of the outermost frame too often, so that our eventual return to it can be sensed more strongly).

Kristin and I have written at length about these strategies in earlier entries (here and here). To recapitulate, Kristin found Inception‘s reliance on continuous exposition a worthwhile experiment, and I argued that the lucid-dreaming gimmick was simply a motivational strategy, a pretext for connecting multiple plotlines through embedding rather than parallel action. My point in the first essay is summed up here:

As ambitious artists compete to engineer clockwork narratives and puzzle films, Nolan raises the stakes by reviving a very old tradition, that of the embedded story. He motivates it through dreams and modernizes it with a blend of science fiction, fantasy, action pictures, and male masochism. Above all, the dream motivation allows him to crosscut four embedded stories, all built on classic Hollywood plot arcs. In the process he creates a virtuoso stretch of cinematic storytelling.

My later thoughts tried to survey the breadth of Nolan’s development of formal strategies. Here’s my conclusion:

From this perspective, Inception marks a step forward in Nolan’s exploration of telling a story by crosscutting different time frames. You can even measure the changes quantitatively. Following contains four timelines and intercuts (for the most part) three. Memento intercuts two timelines, but one moves backward. Like Following, The Prestige contains four timelines and intercuts three, but it opens the way toward intercutting embedded stories. The climax of Inception intercuts four embedded timelines, all of them framed by a fifth, the plane trip in the present. For reasons I mentioned in the previous post, it’s possible that Nolan has hit a recursive limit. Any more timelines and most viewers will get lost.

The Dark Knight Rises hasn’t dulled my respect for Nolan’s ambitions. Very few contemporary American filmmakers have pursued complex storytelling with such thoroughness and ingenuity.

Nolan has made his innovations accessible, I argued, by the way he has motivated them. First, he appeals to genre conventions. Following and Memento are neo-noirs, and we expect that mode to traffic in complex, perhaps nearly incomprehensible plotting and presentation. He has called Inception a heist film, and what many viewers objected to—its constant explanation of the rules of dream invasion—is not so far from the steady flow of information we get in a caper movie. In the heist genre, Nolan remarks, exposition is entertainment. Further, the separate dreams rely on familiar action-movie conventions: the car chase that ends with a plunge into space, the fight in a hotel corridor, the assault on a fortress, and so on.

But I should have mentioned another method of motivation–one that helps make the films comprehensible to a broad audience. In some cases the formal trickery is justified by the very subjectivity the film embraces. It’s one thing to tell a story in reverse chronology, as Pinter does in Betrayal; but Memento’s broken timeline gets extra motivation from the protagonist’s purported (not clinically realistic) anterograde memory loss. (We’ve already seen a lot of amnesia in film noirs.) Subjectivity is enhanced by the almost constant voice-over narration, reiterating not only Leonard’s thoughts but what he writes incessantly on his Polaroids and his flesh.

In The Prestige, each magician’s journal records not only his trade secrets but his awareness that his rival might be reading his words, so we ought to expect traps and false trails. And in Inception, the notion of plunging into a character’s mind becomes literalized as a dream state. Once we accept the conceit of controlled dreaming, we can buy all the spatial and temporal constraints the dream-master Cobb sets forth. As with Memento, Nolan creates a set of rules that allow him to crosscut many different time lines. In each film, the subject matter—memory failure, magicians’ enigmas, controlled dreaming—serves as an alibi for both subjectivity and broken timelines.

Synching story and style

Can you be a good writer without writing particularly well? I think so. James Fenimore Cooper, Theodore Dreiser, Sherwood Anderson, Sinclair Lewis, and other significant novelists had many virtues, but elegant prose was not among them. In popular fiction we treasure flawless wordsmiths like P. G. Wodehouse and Rex Stout and Patricia Highsmith, but we tolerate bland or clumsy style if a gripping plot and vivid characters keep us turning the pages. From Burroughs and Doyle to Stieg Larsson and Michael Crichton, we forgive a lot.

Similarly, Nolan’s work deserves attention even though some of it lacks elegance and cohesion at the shot-to-shot level. The stylistic faults I pointed to above and that echo other writers’ critiques are offset by his innovative approach to overarching form. And sometimes he does exercise a stylistic control that suits his broader ambitions. When he mobilizes visual technique to sharpen and nuance his architectural ambitions, we find a solid integration of texture and structure, fine grain and large pattern.

Here’s a one-off example. Nolan has remarked that he’s mostly not fond of slow-motion simply to accentuate a physical action, or to suggest some mental state like dream or memory. Inception motivates slow-motion by another of its arbitrary rules, the idea that at each level of dreaming time moves at a different rate. Here a stylistic cliché is transformed by its role in a larger structure, as Sean Weitner pointed out in a message to us.

Memento displays a more thoroughgoing recruitment of style to the purposes of guiding us through its labyrinth. The jigsaw joins of the plot require that the head and tail of each reverse-chronology segment be carefully shaped, because they will be reiterated in other segments. Within the scenes as well, Nolan displays a solid craftsmanship, with mostly tight shot connections and an absence of stylistic bumps.

He can even slow things down enough for a fifty-second two-shot that develops both drama and humor. Leonard has just shown Teddy the man bound and gagged in his closet, and Teddy wonders how they can get him out. In a nice little gag, Leonard produces a gun from below the frameline (we’ve seen him hide it in a drawer) and then reflects that it must be his prisoner’s piece. This sort of use of off-frame space to build and pay off audience expectations seems rare in Nolan’s scenes.

The moment is capped when Leonard adds, “I don’t think they let someone like me carry a gun,” as he darts out of the frame.

The straightforward stylistic treatment of Memento‘s more-or-less present-time scenes, both chronological and reversed, is counterbalanced by the rapid, impressionistic handheld work that characterizes Leonard’s flashbacks to his domestic life and his wife’s death (in color) and his flashbacks to the life of Sammy Jankis (in black-and-white). Nolan shrewdly segregates his techniques according to time zone.

If anything, The Prestige displays even more exactitude. Facing two protagonists and many flashbacks and replayed events, we could easily become lost. Here Nolan doesn’t use black-and-white to mark off a separate zone. Instead he relies more on us to keep all the strands straight, but he helps us with voice-overs and repeated and varied setups that quietly orient us to recurrent spaces and circumstances. Here Nolan’s preference for cutting together singles is subjected to a simple but crisp logic that relies on our memory to grasp the developing drama.