Archive for the 'Directors: Spielberg' Category

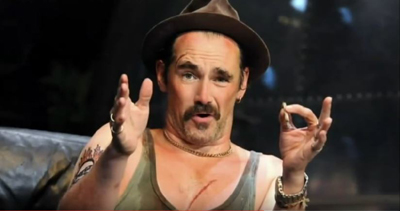

Mark Rylance, man of mystery

Kristin here:

I asked Rylance, a most certain Best Supporting Actor nominee, if success would spoil him now. He had a good retort: “I thought I was successful already!” Indeed, he sure is. But Hollywood will embrace him.

Will it? Well, it can try. It should try.

SPOILERS for Bridge of Spies ahead.

Another great veteran actor who came out of “nowhere”

Upon reading the reviews of Steven Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies published over the past few weeks, many American moviegoers may have been puzzled by the fact that one of the most highly praised elements of the film was the supporting performance of Mark Rylance. Indeed, the praise was often unusually enthusiastic, with Rylance already considered a favorite for a supporting actor Oscar nomination or even win. I suspect that the vast majority of Americans have never heard of Mark Rylance, three-time Tony winner, two-time Olivier-award winner, Emmy nominee, etc. He fits the cliché of the “overnight success” who has been around for a long time and was, as he says, “successful already.”

In Bridge of Spies, Tom Hanks plays the lead, real-life lawyer James Donovan. In the late 1950s, Donovan accepted the unpopular job of defending a Russian spy, Rudolph Abel (played by Rylance), when he came to trial. Later he agreed to negotiate with the Soviet government to swap Abel for downed American pilot and spy Francis Gary Powers. Bridge of Spies is not one of Spielberg’s most exciting or endearing films, but it’s very well made and as classical in its traits as a film can be. It sits nicely beside his other historical dramas, Lincoln and the excellent Munich. On the whole the film has been well-reviewed, with a 92% favorable rating from all critics on Rotten Tomatoes, increasing to 98% among top critics. Rylance is clearly a major reason for the excitement.

It’s Rylance who keeps Bridge of Spies standing. He gives a teeny, witty, fabulously non-emotive performance, every line musical and slightly ironic — the irony being his forthright refusal to deceive in a world founded on lies. (David Edelstein)

Because this is Hanks we’re dealing with, audiences know what to expect, though the revelation here is Rylance (an actor Spielberg also cast as his forthcoming BFG), who appears utterly transformed — to the few who recognize his typically charismatic screen presence — into a balding, Eeyore-like gray moth of a man. (Peter Debruge; the reference is to Spielberg’s The BFG, with Rylance in the lead as the Big Friendly Giant, based on the Roald Dahl children’s novel and now in post-production)

Rylance, one of the greatest of contemporary stage actors, has to date had only an intermittent screen career, but Bridge of Spies suggests that could be about to change. He brings fascination and very, very subtle comic touches to a man who has made every effort to appear as bland, even invisible, as possible. (Todd McCarthy)

Brilliantly played by British theater legend Mark Rylance — who nearly steals the show. (Lou Lumenick)

Meanwhile, Rylance, who’s still probably best known for his brilliant work on stage, is the film’s real breakout discovery. With his musical Northern English accent and bemused, ironic demeanor, he turns a story that could feel as musty as a yellowed stack of old newspapers snap to exuberant life. (Chris Nashawaty)

Mark Rylance, the great English actor, director, and playwright who for a decade was the artistic director of Shakespeare’s Globe theater, performs some mysterious act of alchemy in his role as the ineffable and unflappable Soviet spy. Almost without speaking a word, he communicates this character’s rich inner life, in which a near-Buddhist resignation to the whims of fate alternates with a feisty instinct for self-preservation. (Dana Stevens)

Part of the reason why the Germany sequences sag is that they don’t feature Abel, who is played by British actor Mark Rylance in what, with luck, will be a career-making performance. Many viewers may not have heard of Rylance, who recently played Thomas Cromwell in “Wolf Hall” on PBS. But his work in “Bridge of Spies” deserves to be widely recognized as an example of screen acting at its most subtle, poignant and exquisitely calibrated. (Ann Hornaday, who, like Friedman, does not acknowledge that Rylance already had made quite a career for himself)

I could go on, but for more see the reviews by Manohla Dargis, Richard Roeper, Kenneth Turan, and Michael Phillips.

I don’t, in fact, think that the German sequences sag. Basically the first half of the film covers the trial and sentencing of Abel, with brief scenes of Powers’ training for his spying missions flying over Soviet territory. Once Powers is shot down, Donovan goes to East Berlin for the negotiations, leaving Abel behind in prison.

The German sequences involve a marvelously authentic post-war East Berlin, designed by Adam Stockhausen, who won an Oscar for the production design of The Grand Budapest Hotel. (I wasn’t there in the early 1960s, of course, but I did visit East Berlin in 1992, when part of the wall was still up and the place had a very Soviet look, complete with giant busts of Marx and Engels.)

No, these scenes don’t sag, but there is definitely a niggling question in the back of one’s mind: When are we going to see Abel again? Rylance somehow makes this very ordinary-looking, quiet man the heart of some of the film’s best scenes.

Treading the boards

As Rylance pointed out in the quotation at the top of this entry, he already had an illustrious career going long before Wolf Hall and Bridge of Spies hit American screens. (The Wikipedia entry on Rylance  gives helpful biographical information as well as separate lists of his stage, film, and television performances and the nominations and awards resulting from each.) From 1995 to 2005, he was the first Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre, the replica of the original Elizabethan-period theatre in which many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered. He starred in a number of its Shakespeare productions, including some with authentic all-male casts and period costumes and staging.

gives helpful biographical information as well as separate lists of his stage, film, and television performances and the nominations and awards resulting from each.) From 1995 to 2005, he was the first Artistic Director of the Globe Theatre, the replica of the original Elizabethan-period theatre in which many of Shakespeare’s plays premiered. He starred in a number of its Shakespeare productions, including some with authentic all-male casts and period costumes and staging.

Rylance also won awards playing a variety of very different characters. In 1993 he won his first Olivier award (the top British acting honor) for playing Benedick in Much Ado about Nothing, and followed that up with a British Academy Television award for the TV film The Government Inspector (directed by Peter Kominsky, who later directed him in Wolf Hall, for which he was nominated for an Emmy). He did a comic star turn in a 2007 staging of Boeing-Boeing and was nominated for another Olivier; he won his first Tony when the production moved to Broadway. His second Olivier and second Tony came for his performance as Johnny Byron in Jerusalem, first in London and then on Broadway.

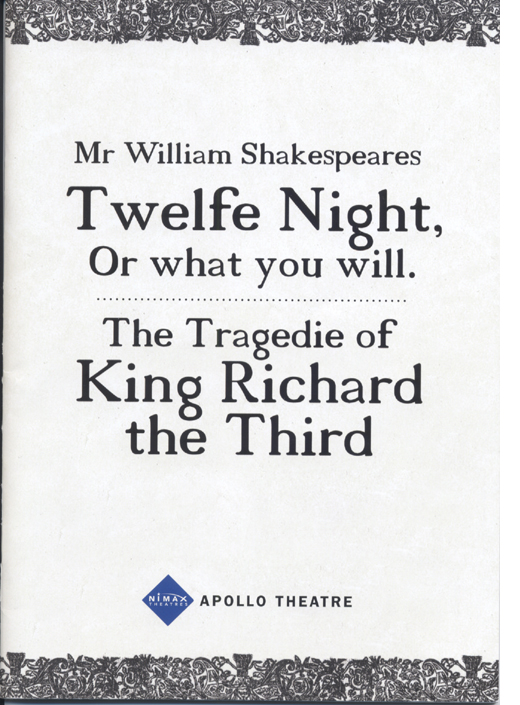

Perhaps Rylance’s greatest success, however, came with a pair of Shakespeare plays done in repertory, Twelfth Night, in which he played Olivia, and Richard III, with him in the title role. Rylance had played Olivia at the Globe in 2002, but from November, 2012 to February, 2013, both plays ran in alternation in the West End. Later they transferred to Broadway, where Rylance was nominated for a Tony as best actor as Richard III and won for best featured actor as Olivia. The plays were done as authentically as possible, with men playing all the roles and wearing costumes true to Shakespeare’s era.

Ben Brantley conveys some of the excitement of these productions and Rylance’s performances in his New York Times review:

In this imported production from Shakespeare’s Globe of London, deception is a source of radiant illumination for the audience, while the bewilderment of the characters onstage floods us with pure, tickling joy. I can’t remember being so ridiculously happy for the entirety of a Shakespeare performance since — let me think — August 2002.

That was the last time I saw the Globe’s “Twelfth Night” (in London), directed by Tim Carroll and starring the astonishing Mark Rylance, in a bar-raising performance as the Countess Olivia. And how thrilled I am that our wandering paths have crossed once more, rather like those of the separated twins at the play’s center.

This “Twelfth Night” — which opened on Sunday in repertory with a vibrant and shivery “Richard III” that allows Mr. Rylance to show he’s as brilliant in trousers as he is in a dress — makes you think, “This is how Shakespeare was meant to be done.”

Walter Kaiser makes similar remarks in The New York Review of Books (available to subscribers only; in print in the February 6, 2014 issue):

The production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night by the English theatrical company Shakespeare’s Globe, currently at the Belasco Theatre, brings this play to life in a way I have only very rarely seen equaled in a Shakespearean production. The performances are so uniformly skillful, the interpretation of the play so intelligent and imaginative, and the costumes and stage set so accurate and evocative that the entire experience is exhilarating. Audiences at the performances I’ve attended have been overcome with delight, clearly somewhat surprised by the affecting immediacy of the theatrical experience they have undergone, unaccustomed to a Shakespeare so readily comprehensible and so vividly alive. You may, if you’re lucky, see another Shakespearean production that’s as good as this one, but it’s unlikely you will ever see one that’s better. […]

Mark Rylance, who over the past decade or so has made the part his own, is undoubtedly one of the greatest Olivias of all time. Frequently, this part is played with a grave, graceful maturity that tends to mask, or at least minimize, the intensity of the emotional quandary Olivia finds herself in when, not wishing to receive any further expressions of love from Orsino, she discovers that she has fallen in love with the messenger who delivers them. Rylance, instead, beautifully exposes her perfervid confusion: overcome with emotion, he stammers (in confirmation of Viola’s observation that “she did speak in starts”), acts with impetuosity, and manifests, at times, an engaging exasperation with his inability to control his passion. His hands alone, in the informative subtlety of their gestures, betray the emotions Olivia wishes to conceal.

I was lucky enough to encounter this Twelfth Night, as well as Richard III, in late 2012 when I was in London for a few days. I’m partial to authentic performance styles in theatre and music, so the chance to see two Shakespeare productions with all-male casts was appealing. Little did I realize that I would be seeing two brilliant turns by an actor I had never seen before–or so I thought. In fact, he plays Ferdinand in Prospero’s Books, but nobody, especially in such a small, bland role, can get much attention when playing alongside John Gielgud as Prospero.

Spielberg discovered Rylance in the same way that I did. In a very informative article based on interviews with Rylance and Spielberg, Jack Cole reveals:

Spielberg was urged to see Rylance in “Twelfth Night” by Daniel Day-Lewis. He calls him “a shape-shifter, a man of a thousand faces and voices who can play any part.”

“Seldom has an actor been around for so many distinguished years on the stage and yet had not been fully discovered for the screen,” said Spielberg by email. “Mark understands that the camera records stillness better than in any other media. His transition from the stage to ‘Bridge of Spies’ was graceful and invisible.”

Cromwell and Abel and beyond

Those members of the American public who did know Rylance before Bridge of Spies had probably encountered him as Thomas Cromwell in the BBC series Wolf Hall, a Tudor-era costume drama which aired in six parts on PBS starting April 6, 2015. (David and I streamed it more recently, mainly to see Rylance.) It seems unfortunate that the two breakout roles that have brought the actor to such prominence this year both involve notably restrained performances.

Anthony Lane compared these performances in his New Yorker review of Bridge of Spies:

So what’s it all about? It’s not about the U-2 missions, and certainly not about Powers, who comes across as a lunk. Nor, despite the set pieces in court, is it about the majesty of the law. No, the core of this movie is a standoff every bit as keyed up, and as gripping, as anything on the muffled streets of Berlin. What we thrill to is Rylance versus Hanks: the British actor, lauded for his stage appearances, but barely known to cinema audiences, up against the consummate Hollywood pro. You can see them prowling, probing, and wondering what the next move will be—or, in Hanks’s case, wondering whether Rylance will move at all. Admirers of “Wolf Hall,” on PBS, will have noted him as Thomas Cromwell, standing like a statue in the shadows, and realized, to their discomfort, that they could not look away. He does the same thing here, as Abel; we watch him watching everybody else, as if life were an infinity of spies. “You don’t seem alarmed,” Donovan says when they first meet, and Abel replies with a gentle question: “Would it help?” The Coens turn that into a refrain that beats through the movie, growing wryer and funnier each time—right up to the fidgety finale, where Abel is the calmest man in sight.

Of course, Cromwell does move in Wolf Hall. He moves a lot. Few television series can have shown their protagonists walking from place to place so often and at such length. Rylance modeled his gait on that of a Hollywood star, according to the Cole piece cited above: “He’s explaining how Mitchum, whom he adores, inspired his steady, rigid gait in the international hit series ‘Wolf Hall.'”

More Rylance on Mitchum, from another interview:

I’ve watched lots of films preparing for this, and I was particularly struck by one of my favourite actors, Robert Mitchum, how his performances haven’t dated in the way that even perhaps more versatile actors, Brando and Dean and people of that era, have. I noticed how well he listens, how still he is, how present he seems. You’re drawn towards the screen – wondering what’s he thinking, what’s he going to do next. That’s always the best way to tell a story.

Kominsky describes adjusting his filming style for Wolf Hall to catch Rylance’s subtleties:

The one thing you might not be expecting is that he’s the most minute of film performers. Nothing is overblown. Nothing is writ too large. It’s very, very simple, very understated, his performance, and then you look into his eyes, and it’s all happening. Everything is going on in there, and of course, you’re drawn into closer and closer shots, just to try and capture the emotion that’s going on very slight below the surface, and that’s what I loved to film. (From George Pollen documentary, Sky’s Arts program, 19:00-19:47)

As David has pointed out, however, the eyes as such are not always particularly expressive. It’s the area of the face that contains the eyes that does the job. The eyebrows and forehead usually give the context that tells us what the eyes are expressing.

If we concentrate on the upper half of Rylance’s face, the considerable differences between his Cromwell and his Abel become apparent.

As Abel, he consistently does something rather remarkable: he raises his eyebrows, creating furrows in his forehead, without widening his eyes. That’s not an easy thing to do. The result is a perpetually curious or surprised expression, a sort of mask that Abel wears to suggest that he is naive, innocent, a little slow. In fact, as we discover whenever he speaks with Donovan, he’s well aware of everything going on around him and has considerable insight into it. But it’s the naivete that allows him to dupe the agents who search his hotel room into letting him clean the paint off his palette, thus allowing him to conceal a key bit of evidence.

The key moment during which Rylance drops this tactic happens during his “standing man” anecdote, about a man he knew who survived a severe beating by Soviet agents by simply getting up again each time he was struck to the ground; Donovan reminds him of that man, he says.

As Cromwell, Rylance’s main tactic using his face is to glance away at nothing in the course of a scene where he is conversing with someone or observing interactions among other characters. So much classical editing depends on our understanding of whom or what a character is looking at, but not here. In one scene, Ann Boleyn shows him a drawing she has found hidden in her bed, depicting her decapitated. She asks him to find out who put it there.

Apart from his eyes, Rylance remains uttlerly motionless through the shot in which she holds the drawing out to him. Initially he is looking at her face (that’s the side of her head out of focus in the foreground) and then glances down at the drawing as she holds it up from below the frame.

He then glances down briefly to a point just outside frame right–clearly not at Boleyn’s face or anything else relevant to the action.

He looks at her face again and finally at the drawing.

Nothing here betrays Cromwell’s emotions, since he is a man who has to keep his thoughts hidden from most of the people at court. But that extra shifting of the eyes momentarily to an inconsequential space shows us that he’s thinking. Maybe he has an idea as to who would have left the letter. Maybe he’s thinking of Ann’s sister’s warning to him in an earlier scene, telling him not to help Ann. We don’t know here, as we don’t in many other scenes where Rylance uses this same sort of eye movement.

Both Abel and Cromwell need to conceal their thoughts, but Abel does so through deception and Cromwell through concealment, both conveyed by subtle acting.

In the Pollen documentary, Rylance describes how he avoids putting too much into a performance (in this case referring to lecturing on stage acting to students):

If I was only allowed three words, I could distill all my complicated notes, and you can see how wordy I get if I get talking, to three words, which would be “You are enough.” What’s happening to you is you don’t feel you’re enough, and you’re putting more effort into it than you should. You’ll be in the center of yourself, your voice will be centered, your movements will be centered, and the audience will also believe you more, because they’ll also believe that you’re enough. (8:35-9:08)

In Bridge of Spies, the little gestures and bits of business that Rylance uses to draw our attention to Abel are minimal. He wipes his nose occasionally, apparently the victim of a persistent cold or allergy.

As Michael Phillips points out in his review, this cold creates a parallel to Donovan, who has his overcoat stolen in East Berlin and soon develops a cold of his own:

It’s brilliant, really. What’s the quickest way to establish the humanity of two leading characters in a Cold War drama? Give them both the sniffles. […]

Because he’s relatively new to multiplex audiences, Mark Rylance will likely walk off with the acting honors for “Bridge of Spies.” He looks nothing like the real Abel, but in a largely nonverbal, supremely poker-faced performance — even his stuffy nose is subtle — Rylance suggests a forlorn practitioner of deception who recognizes a lucky break when he sees it.

(Agent Hoffman has also caught a cold by the epilogue; an occupational hazard, apparently, and a subtle comic motif.)

There are other gestures: lengthy tapping of a cigarette on an ashtray and little sucking movements of the lips, suggesting ill-fitting dentures. (A bit more subtle scene-stealing than that practiced by Steve McQueen in The Magnificent Seven, as described by David.)

Yet Rylance is perfectly capable of comic, broad performances as well. His Olivier-and-Tony-winning turn in Jerusalem was as a raucous, drunken rascal.

He made Richard III a grotesquely deceitful clown.

His Olivia, though more restrained, can do a broad comic take, as when she first notices Malvolio sporting the detested cross-gartered yellow stockings (see bottom).

We can assume that his acting as the BFG will be miles away from his performance in Bridge of Spies.

Will Hollywood be able to embrace him?

Roger Friedman claims that Hollywood wants Rylance. Possibly, but Rylance is ambivalent about filmmaking and generally prefers the stage. Indeed, I wish I had a reason to be in London right now, since he is back in the theater, receiving more rave reviews as the depressed King Philippe in a limited run of Farinelli and the King, the much-praised first play by Rylance’s wife, Claire van Kampen.

The Cole piece sums up Rylance’s on-and-off relationship to film acting, which involves Rylance being willing to embrace it rather than it embracing him:

For Rylance, embracing movie acting has been a circuitous journey. As a young actor, he watched as his theater contemporaries — Daniel Day-Lewis, Gary Oldman, Kenneth Branagh — became famous on the big screen. Agents urged Rylance into TV and film so that he would be “a complete actor.”

“I just, time and again, was attracted by the theater where I was offered better opportunities,” says Rylance. “I auditioned for films and didn’t get them. I think I had some stuff to learn about film acting. I don’t think I was personally really ready for it. But I did come to resent it. I did eventually think: Why, why? You wouldn’t tell the great Tamasaburo or Ganjiro-san it’s not enough to be a Kabuki actor, you need to be a film actor.”

He rattles off some film experiences he’s enjoyed: the Quay brothers’ “Institute Benjamenta,” a A.S. Bryatt adaptation “Angels and Insects” and a handful of British TV films, like “The Government Inspector.”

“But I’ve made some bad films, too, that have not been enjoyable,” Rylance said on a recent New York afternoon on a day off from starring in van Kampen’s “Farinelli and the King” in London. “At a certain point after one of them I did a few years back, I said, ‘That’s it. I’m not interested in this anymore.’

“I thought: I need to be happy with who I am, where I am. That can be the kind of miners’ dust of being an actor,” he says. “For an actor, being dissatisfied with who you are can be the reason for becoming an actor, but it can become an illness.”

But once Rylance let go of being a movie star, film directors started calling.

“As I did that, wonderful film things started being offered to me,” he says. “Maybe that was partly the problem — that I was giving it too much forced value. Because I grew up in America, so I grew up with some theater. But mostly I saw three films a weekend in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.”

Yes, Rylance was a Wisconsin boy, in a sense. He was born in Kent in 1960, and his parents, both English teachers, moved to Connecticut in 1962 and then to Milwaukee in 1969. There his father taught at the University School of Milwaukee, where Rylance first studied acting. “He starred in most of the school’s plays,” as the Wikipedia entry cited above puts it. Returning to England, he studied at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Arts from 1978 to 1980. His time in the States suggests why his accent is not quite the normal English one that we expect from the great British actors. It is nice to think that Rylance was avidly attending films in Milwaukee during the same period when David and I were doing the same here in Madison.

Clips of some of Rylance’s stage roles are included in the George Pollen documentary linked above; others can be found by searching on YouTube. Fortunately the wondrous Twelfth Night was recorded and is available on DVD (here in the US and here in the UK). The rest of the cast is excellent, particularly Steven Fry as Malvolio and Paul Chahidi as Maria. The many cameras used in the filming capture the most salient action at every point and alternate details and long shots to give a sense of where the action is occurring. As the image below shows, it was filmed in the Globe, with the audience right up against the stage and quite obvious (in a good way) in many of the camera setups. In the scene below, a spectator gives a wolf-whistle as Malvolio struts about his his yellow stockings, which strikes me as a very groundling sort of thing to do. Having seen the performance from the front-row center of the balcony, I am glad to have a closer perspective.

[December 2: Rylance has won the New York Film Critics Circle award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[January 3, 2016: Rylance has won the National Society of Film Critics award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[February 15, 2016: Rylance has won the British Academy Film Award for Best Supporting Actor.]

[February 28, 2016: Rylance has won the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor. The story linked to here considered this an upset, as Sylvester Stallone had been widely predicted to win. But as I’ve shown here, a lot of us back in October knew better.]

[February 29, 2016: Rylance has been nominated for an Olivier Award for Farinelli and the King.]

[March 6, 2016: Pete Hammond of Deadline Hollywood has pointed out that Rylance won his Oscar without ever having participated in a single campaign event in the awards season. (He was given a day off from his current stage show in Brooklyn, Nice Fish, to go to Los Angeles to attend the Oscars ceremony.)]

[December 31, 2016: The Queen’s New Year’s Honours for 2017 include a knighthood for Rylance.]

Beyond praise 5: Still more supplements that really tell you something

Real-time performance-capture images for The Adventures of Tintin.

Kristin here:

The Extraordinary Voyage (2011, Serge Bromberg and Eric Lange)

I had expected to follow up my entry on Hugo when the DVD was released. I anticipated that its supplements would explore the flashy technical and artistic aspects in detail. But the lengthy first chapter proved to be largely the cast and crew presenting variations on how lucky they were to have worked with Martin Scorsese (and each other) and how much they learned from him.

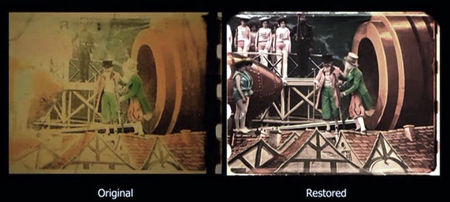

That wasn’t promising, and I turned instead to Georges Méliès himself. Flicker Alley, which has served the filmmaker so well in the past (see here), has recently released the restored color version of A Trip to the Moon in a Blu-ray/DVD combination set. It is accompanied by a 65-minute documentary on the Méliès, the film, and the restoration. It’s odd to call a 65-minute film that accompanies a fifteen-minute “feature” a supplement, but I recommend it anyway.

I suspect that The Extraordinary Voyage would be quite effective in easing students into very early silent cinema and intriguing them about an era that must seem hopelessly remote to them. It begins with a charming introduction to the context of the turn of the previous century and then moves quickly into the director’s young-adult life. When it comes to the famous incident in which Méliès’ camera jammed while he was filming, creating an inadvertent magical transformation, the filmmakers have an actual 1937 recording of Méliès himself describing the event. Presumably this was the original source of this oft-repeated anecdote. He specifies that it happened on the Place de l’Opéra and involved a bus turning into a hearse. I still wonder if it all happened so neatly, but hearing it directly from Méliès makes it a little more plausible. If it wasn’t true, it should have been.

The film includes as talking heads several filmmakers who admire Méliès’ work: Costa-Gavras, Jean-Pierre Jeunet, Michael Gondry, Tom Hanks, and Michel Hazanavicius. There is a good summary of the fascination with the moon in popular culture of the day,  including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

including works by Jules Verne, Jacques Offenbach, and H. G. Wells.

The documentary touches on issues relevant to early silent cinema in general. One of these is the frequent pirating of films, with Méliès starting an American branch of his Star Films in New York, under the direction of his brother Gaston, to help protect his intellectual property. A clip from the Segundo de Chomon version of the film, An Excursion to the Moon, is included.

At about 23 minutes in, a short overview of early movie music is given, followed by a helpful explanation of how the hand-coloring of Méliès’ films was handled by a local workshop run by women. At 30 minutes in there are several dazzling examples of hand-colored scenes (right).

After a quick summary of Méliès’ decline and death, the film moves to the restoration of the only known hand-colored copy of A Trip to the Moon, found in the film archive in Barcelona. Here the hero is Tom Burton, the Director of Technicolor Creative Services, who gives a brief indication of how computers have transformed restoration:

We have a palette of digital tools to work from that are a collection of maybe five or six of the main commercially available restoration platforms, but then we also bring into the mix all of the approaches that you would use if you were doing visual effects for a modern movie.

The comparison of visual effects with restoration is in some ways an apt one and might lead students to look upon early films in a new light.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (Blu-ray/DVD/Ultraviolet set, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

It’s probably a good idea to supply both Blu-ray and DVD discs in one package, but including the supplements only in Blu-ray is annoying and increasingly common. That’s the way the Girl with the Dragon Tattoo discs have been handled. Teachers without access to a Blu-ray player have fewer options when trying to use supplements in teaching. It also makes it much more difficult to make frame grabs from the supplements to, say, illustrate a blog entry on useful supplements.

I decided to check out the supplements for this film because the ones for Zodiac and The Social Network were so good. I figured David Fincher was particularly concerned about his films’ bonus materials. Unfortunately this set of supplements is quite uneven. The cast and crew seem to be obsessed with the character of the heroine and with the delights of shooting in Sweden. I confess that I stopped watching some of the chapters as the talking heads went on and on about these subjects. Some of the tracks also consisted of a lot of candid behind-the-scenes footage, which is all very well, but there was little structure to this and only occasional comments to explain what was going on.

Fortunately the “Post-Production” section is very informative and interesting. “In the Cutting Room” is fairly technical but makes some fascinating points. I particularly liked the description of how Fincher eliminates reframings and unsteady shots by using the extra image space allowed by newer capture media. (Earlier digital film frames allowed no extra image area outside what would show up on the screen; as the image below indicates, the final frame can be selected from a larger picture.) This desire for a stable image in an era where the “queasi-cam” so often rules points to one distinctive trait in Fincher’s style. It indicates a willingness to actually think through the framing of each individual shot and the purpose for choosing that framing. Steven Spielberg does the same thing. Many don’t.

Editor Angus Wall talks about this advantage of the extra size of the image and how Fincher uses it to stabilize unsteady images. It’s worth quoting at length, and it demonstrates the thoughtful commentary in this particular supplement:

I’ve never seen a movie that was sort of “re-operated” to the extent that this one was. Which I think has an effect on the viewing of the movie. David is really type-A in terms of making the shots very specific. They start in a certain way, they end in a certain way. And the framing, he’s very precise in terms of his composition. He doesn’t like a lot of what you see in 99% of movies, which is very subtle moves where the operator will actually reframe according to how the actor’s moving. David doesn’t like that. Even if there were a lot of those in this film, and before, some of those takes we would have thrown out, because we just wouldn’t have been able to stabilize them to the degree that he likes it. With this, because you have this full raster, this big area around the image, you can take those images and stabilize them, really lock them down. So the movie is really locked down in terms of camera operating. More than any other movie that I can think of.

The smooth glide as the car initially approaches the country house is one example of that utter stability, used to ominous effect in that particular scene.

There’s also some interesting discussion about how the two main characters don’t meet each other until well into the film and how that affected decisions about editing. Rather than frequently intercutting between Mikael Blomkvist and Lisbeth Salander, the filmmakers decided to create longer self-contained scenes involving each, thus switching back and forth less frequently. The idea was that the exposition set forth in each scene would be too difficult to absorb if it was chopped into smaller segments. Form, style, and function, neatly explained.

Fincher also points to an interesting underlying anxiety the spectator might feel because the narrative progress gives little sense of how much action is still to come:

You don’t know where you are in the narrative. You don’t know if you’re at the beginning of the third act or … I don’t think it’s bad, because we have a five-act movie. I think that’s what’s causing everybody’s anxieties, that it doesn’t feel like, OK, here’s where we are, we’re entering the third act now. Now it feels like, fuck, this movie could go on … indefinitely. That’s the part that’s bothering me. If we told them it was going on for another forty-five minutes, they wouldn’t have a problem. It’s the indefinite part.

Since I’ve written a book claiming that classical films usually don’t have three acts, I was intrigued by this statement. (See also my earlier blog entry here and David’s essay here.) I posit instead that classical films typically create acts that run about 25 to 30 minutes, and that the film’s length determines how many acts it has. Four acts is the most common throughout Hollywood’s history, but a 158-minute film would be likely to have five acts. (Has David Fincher read my book?!) His point about the audience feeling a bit lost in an unconventional narrative structure is a rare instance of a director talking about form in such an abstract way, and it seems quite valid for The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

It’s also rare to get a supplement on ADR (automated [or additional] dialogue replacement), but there’s a six-minute one in the “Post-Production” section. This consists of a behind-the-scenes session with Rooney Mara supplying not just dialogue but breathing, grunts, and other noises. It’s clearly a real session, not a staged one, though the actress does seem a bit self-conscious with the documentarian’s camera turned on her. Fincher’s and Mara’s banter between takes gives a sense of what I suspect really goes on during this phase of production.

There’s a brief supplement called “Main Titles,” which deals with the form and inspiration for the CGI under the titles. Fincher wanted to tell the story of the whole trilogy in two and a half minutes, “and it has to be spectacular.” Apart from the discussion of form, there’s a good look at unrendered CGI footage compared to the finished images.

Finally, an eight-minute “Visual Effects Montage” displays a variety of special effects in a clever way. There is a section at the beginning where we are shown the image without added effects, then the same image with the areas to be altered highlighted in various superimposed colors, and finally the finished images with the effects added. This is particularly good for showing the sorts of mundane effects that are used to enhance shots unnoticeably, adding cars’ headlight beams, reflections in glass, falling snow, and the like. There is a shot with a section of a building on location blotted out with a greenscreen and the final shot showing the use of alterations in the building:

Obviously here the fog was also added with CGI.

This montage goes very quickly. If you’re using it in a class, best to prepare ahead and be ready to pause and point out what’s going on in the many short shots used in the demonstrations.

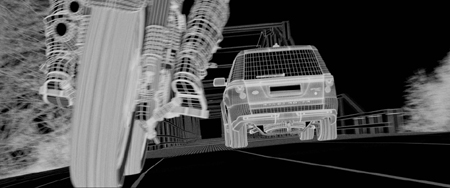

The second half of the effects montage moves to splashier scenes of the type the public associates with “special effects”: wire-frame vehicles for a chase (see image at the top of this section), head-replacement to add Mara’s head to her stunt-double’s body, and explosions.

Don’t bother with the “Stockholm Syndrome” section. Basically all we learn is that when a scene is shot on location, sheep can unexpectedly wander in and interfere.

The Adventures of Tintin (Blu-ray/DVD/Digital Copy combo, Paramount Pictures)

Again, the supplements for this release are available only in Blu-ray.

Steven Spielberg and Peter Jackson decided some years ago to collaborate on what was announced to be a three-film series adapted from Hergé’s Tintin comic books. The notion was that each of them would direct one film, with an as-yet-unspecified director doing the third. Spielberg’s initiatory film did not do as well at the domestic box-office as had been hoped, though it fared better in Europe and other non-North American markets, where the comics are highly popular. Jackson has announced that after he finishes both parts of The Hobbit, he will launch into the next Tintin film. (At least, that’s what he said originally. After yesterday’s announcement that there will be three Hobbit films, his start on the Tintin film will presumably be delayed.)

The supplements form a narrative of the film’s making, bookended by “Toasting Tintin” and “Toasting Tintin Part 2,” brief episodes set at the launch and wrap parties. The tale is pleasant and generally worth watching, though they are far from as entertaining and informative as the supplements that Michael Pellerin produced and directed for Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings and King Kong DVD sets. But this is Spielberg’s show, since he did the first film and indeed originated the project. At first he envisioned the film as live-action, with the dog Snowy the only major CGI character. Spielberg asked Jackson’s effects house Weta Digital to do some tests animating Snowy. To his (apparent) surprise, Jackson himself, as a fan of the comics since childhood, played Captain Haddock in the test. That fact was well known to fans, and the inclusion of the test footage (above) is no doubt a crowd-pleaser.

The decision to use cutting-edge performance-capture techniques led to the film being entirely animated.

“The World of Tintin” gives background on Hergé and deals briefly with the screenwriting process. This leads into “The Who’s Who of Tintin,” dealing with characters and acting, with some good material on performance capture near the end. The next section, “Tintin: Conceptual Design” has good material on the visual style of the characters and near the end includes some pre-viz material.

The outstanding supplement, however, is “Tintin: In the Volume,” nearly 18 minutes of footage concerning performance capture. Spielberg’s role as director was primarily concentrated into a remarkably short 31-day shoot with the actors. This was done in a state-of-the-art performance-capture facility called “The Volume” and located at Giant Studios. The Volume is a large space with about 160 cameras built into the ceiling and pointing down into the performance space. These capture the space from multiple angles. Additional cameras on the stage level follow the actors’ movements, which are inserted into the space. Moreover, hand-held monitors similar to portable gaming devices allow the filmmakers to see simple versions of the settings and the partially rendered characters while pointing the device at the actors in their performance-capture rigs.

There are also larger monitors that show the actors their own performances translated into the characters (top of entry). Whatever one thinks of the look of contemporary animation of this type, the technology has evolved to a remarkable level, and this supplement provides an excellent explanation of the practicalities of performance capture. We see the motion-capture suits being put on and the dots painted onto the actors’ skin. There is also information on how the set elements and props need to be transparent so that the cameras can capture the dots on the actors’ faces and costumes through them. The image at the bottom shows Jamie Bell as Tintin looking at a mock-up of the model ship. It’s made of little metal rods and rendered into a ship on the monitors.

“Snowy: From Beginning to End” is less cutesy than it sounds. It discussed the digital tool developed for modeling the dog’s fur. There’s also good stuff on how several dogs were recorded to provide different-sounding barks depending on the type of action in a scene.

The biggest tasks on the film came after the performance capture and editing. Weta Digital spent two years creating the final images. “Animating Tintin” is an excellent eleven-minute account of that process.

The sections “Tintin: The Score” and “Collecting Tintin” (on Weta Workshop’s designs for the collectible figures) are rather thin and could be skipped unless a teacher wants to show the whole set of supplements as a single “making-of” documentary.

It’s become apparent that many of the best supplements on Blu-ray and/or DVD releases are devoted to special effects, especially performance capture. The Adventures of Tintin does genuinely involve innovations in this technology, and the “In the Volume” chapter is very informative. Supplements are getting repetitive, though, and I would like to see the producers of such documentaries pay more attention to techniques and choices in other areas. Comparing final cuts of scenes with earlier cuts, or showing story conferences where real debates about scripts occur (as was done in the first Pirates of the Caribbean film’s supplements), or displaying how decisions about digital-intermediate grading are made–a bit of imagination could spice up the offerings. That and a realization that film fans are interested in just about any aspect of production (or distribution, for that matter). Supplements risk falling into conventional patterns, and that won’t make them the appealing bonus material that they used to be.

While I was gearing up to write this entry, we received Mark Parker and Deborah Parker’s book, The DVD and the Study of Film: The Attainable Text (Palgrave, 2011). Based on a great deal of research, including many interviews, the authors include a summary history of DVDs and supplements; there is a detailed chapter on The Criterion Collection, interviews with directors and scholars who have recorded commentary tracks, and a case study of Atom Egoyan.

Rebooked

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (Frank Tashlin, CinemaScope).

DB here:

Are blog readers book readers, let alone book buyers? I asked once before, but in a different tone of voice. Books are still being published, thick and fast, and everybody who cares about cinema should take a look at these.

In the frame

Ballet mécanique.

When the talk turns to the great film theorists of the heroic era, you hear a lot about Bazin and Eisenstein, less about Rudolf Arnheim. But the prodigiously learned Arnheim pioneered the study of art from the perspective of Gestalt psychology. Although he’s probably best known for his studies of painting in Art and Visual Perception, as a young man he was a film critic and in 1930 published a major theoretical book on cinema. First known in English as Film, then in its 1957 revision as Film as Art, this has long been considered a milestone. But Arnheim was famously skeptical of color and sound movies, and he had comparatively little to say about the many cinematic trends after 1930. (He died in 2007, aged 102.) While psychologists grew wary of Gestalt ideas, cinephiles embraced Bazin and academics moved toward semiotics and other large-scale theories. For some time Arnheim has seemed a graceful, erudite relic.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

A new anthology seems likely to change that view. Arnheim for Film and Media Studies, edited by Scott Higgins, reveals one of the earliest and most energetic and pluralistic thinkers about modern media. The fourteen authors probe Arnheim’s ideas about film, of course–showing unexpected connections to the Frankfurt School and to avant-gardists like Maya Deren. But there are as well essays on Arnheim’s thinking on photography, television, and radio, along with studies that examine how his ideas would apply to comic books and digital media. Other contributors provide conceptual reconstructions, analyzing his ideas on composition and stylistic history.

This is no esoteric exercise. The essays present probing arguments with patient lucidity. Encouragingly, most of the contributors are early in their careers. (I have a piece in the collection as well, an expanded version of a blog entry.) The anthology proves that a seminal thinker can always be reappraised. There’s always more to be understood.

In the Higgins collection Malcolm Turvey furnishes an essay on Arnheim’s relation to various strands of modernism. That vast movement is treated at greater length in Turvey’s new book, The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s. At the book’s core are close analyses of five exemplary films encapsulating various trends. Turvey studies Richter’s Rhythm 21 and abstract film, Léger and Murphy’s Ballet mécanique and cinéma pur, Clair’s Paris Qui Dort and Dada, Dalí and Buñuel’s Chien Andalou and Surrealism, and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera and the “city symphony” format. For each film Turvey provides informative historical background and, often, some controversial arguments. For example, he finds Léger to be surprisingly concerned with preserving classical standards of beauty. Indeed, one overall thrust of the book is to suggest that modernism was less a rejection of all that went before than a selective assimilation of valuable bits of tradition. (This applies as well to Eisenstein, I think, as I try to show in my book on his work.)

No less controversial is Turvey’s careful dissection of what has come to be known as “the modernity thesis.” This is the idea that urbanization, technological change, and other forces have fundamentally changed the way we perceive the world, perhaps even altered our basic sensory processes. Specifically, some argue, because the modern environment triggers a fragmentary, distracted experience, that experience is mimicked by certain types of film, or indeed by all films. Step by step Turvey argues that this is an implausible conclusion. This last chapter is sure to stir debate among the many scholars who argue for film’s essential tie to a modern mode of perception.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Harper Cosssar’s Letterboxed: The Evolution of Widescreen Cinema begins in the heyday of Arnheim and the silent avant-garde. Indeed, some of the early uses of widescreen, as in Gance’s Napoleon, are indebted to experimental film. But Cossar’s genealogy of widescreen also mentions horizontal masking in Griffith films like Broken Blossoms and lateral or stacked sets in Keaton comedies like The High Sign. More fundamentally, Cossar develops Charles Barr’s suggestion that the sort of viewing skills demanded by widescreen (at least in its most ambitious forms) were anticipated by directors who coaxed viewers to scan the 4:3 frame for a variety of information. The “widescreen aesthetic” was implicit in the old format, and technology eventually caught up to allow it full expression.

Cossar advances to more familiar ground, studying early widescreen practice in The Big Trail and moving to analyses of films by masters like Preminger, Ray, Sirk, and Tashlin. Although most chroniclers of the tradition stop in the early 1960s, Cossar presses on to consider the changes wrought by split-screen films like The Boston Strangler and The Thomas Crown Affair. The survey concludes with discussions of cropping techniques in digital animation (e.g., Pixar) and web videos, which often employ letterboxing as a compositional device. In all, Letterbox traces recurring technological problems and aesthetic solutions across a wide swath of film history.

Critics’ corner

Two of America’s senior film writers have revisited their earlier writings, with lively results. Dave Kehr’s collection When Movies Mattered samples his Chicago Reader period, from 1974 to 1986. Disguised as weekly reviews, Kehr’s pieces were nuanced essays on films both contemporary and classic.

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

Turn to any of them and you will find a relaxed intelligence and a deep familiarity with film history. By chance I open to his essay on Billy Wilder’s Fedora:

It resurrects the flashback structure of his 1950 Sunset Boulevard, but it goes further, placing flashbacks with flashbacks and complicating the time scheme in a manner reminiscent of such demented 40s films noirs as Michael Curtiz’s Passage to Marseille and John Brahm’s The Locket. . . But the jumble of tenses also clarifies the film’s design as a subjective stream of consciousness. The images come floating up, appearing in the order of memory.

How many of those reviewers whose flash-fried opinions count for so much on Rotten Tomatoes can summon up information about the construction of Passage to Marseille or The Locket? And how many could make the case that Wilder, in returning to the forms fashionable in his early career, would repurpose them for the sake of a reflection on death, resulting in “a film as deeply flawed as it is deeply felt”? Kehr’s work from this period is appreciative criticism at its best, and he never lets his knowledge block his immediate response. “I admire Fedora, but it also frightens me.” It’s time we admitted that Dave Kehr, working far from both LA and Manhattan, was writing some of the most intellectually substantial film criticism we have ever had.

Also hailing from the Midwest is Joseph McBride, a professor, critic, and biographer. Apart from his rumination on Welles, his books have focused on popular, even populist, directors like Capra (The Catastrophe of Success), Ford (Searching for John Ford), and Spielberg (Steven Spielberg: A Biography). The University Press of Mississippi and bringing first two volumes of this trilogy back into print, and it has just reissued the third in an updated edition.

Here Spielberg emerges as far more than a purveyor of popcorn movies. McBride sees him as a restless, wide-ranging artist, and the additions to the original book have enhanced his case. McBride offers persuasive accounts of Amistad and A.I., which he regards as major achievements. He goes on to argue that Spielberg’s unique power in the industry allowed him to face up to central political issues of the 2000s.

He made a series of films in various genres reflecting and examining the traumatic effects of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the repression of civil liberties in the United States during the George W. Bush/ Dick Cheney regime. . . . No other major American artist confronted the key events of the first decade of the century with such sustained and ambitious treatment (450).

McBride is no cheerleader. He can be as severe on Spielberg’s conduct as on his films, criticizing much of the DreamWorks product as dross and suggesting that Spielberg sometimes trims his sails in interviews. I’d contend that McBride underrates some of Spielberg’s work, notably Catch Me If You Can and The War of the Worlds. But McBride has perfected his own brand of critical biography, blending personal information (he reads the films as autobiographical), tendencies within the film industry and the broader culture, and critical assessment. All studies of Spielberg’s work must start with McBride’s monumental book. Ten years from now we can look forward to another update; surely his subject will have made a few more movies by then.

Foreign accents

8 1/2.

Today we regard Citizen Kane as a classic, if not the classic. But for several years after its 1941 release it wasn’t considered that great. It missed a place on the Sight and Sound ten-best critics’ polls for 1952; not until 1962 did it earn a spot (though at the top). Its rise in esteem was due to changes in film culture and, some have speculated, the fact that Kane was a regular on TV during the 1960s. Something similar happened with His Girl Friday, another stealth classic. I’ve traced what I know about its entry into the canon in an earlier blog entry.

What about the postwar classics like Open City and Bicycle Thieves and the works of Bergman and Fellini and Antonioni and Kurosawa and the New Wave? Surely some of the films’ fame comes from their intrinsic quality—many are remarkable movies—but would we regard them the same way if their reputation hadn’t spread so widely abroad, especially in America? Questions like this lead us to what film scholars have come to call canon formation: the ways artworks come to wide notice, receive critical acclaim, and eventually become taken for granted as classics.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Consider this. The Toronto International Film Festival’s recent list of 100 essential films includes thirty non-Hollywood titles from the 1946-1973 period, more than from any comparable span. Of the TIFF top twenty-five, twelve are from that era. You can argue that these years, during which several generations of viewers overlapped, set in place a system of taste that persists to this day.

Tino Balio’s Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens, 1946-1973 reveals a side of canon formation that’s too often overlooked. Balio is less concerned with analyzing films than Turvey, Cossar, Kehr, and McBride are. He is asking a business question: What led the U. S. film industry to accept and eventually embrace films so fundamentally different from the Hollywood product?

Several researchers have pointed to the roles played by influential critics, film festivals, and new periodicals like Film Comment and Film Culture. Intellectual and middlebrow magazines promoted the cosmopolitan appeal of the foreign imports. By 1963 Time could run a feverish cover story on “The Religion of Film” to coincide with the first New York Film Festival.

Balio duly notes the importance of such gatekeepers and agenda setters. But he goes back to the beginnings, with the small import market of the 1930s. Turning to the prime postwar phase, he broadens the cast of players to include the business people who risked buying, distributing, and publicizing movies that might seem hopelessly out of step with US audiences. He shows how small importers brought in Italian films at the end of the 1940s, and these attracted New York tastemakers, notably Times critic Bosley Crowther, who were keen on social realism. Within a few years ambitious entrepreneurs were marketing British comedies, Swedish psychodramas, Brigitte Bardot vehicles, and eventually the New Waves and Young Cinemas of the 1960s. As distributors fought censors and slipped films into East Side Manhattan venues, an audience came forward. The “foreign films”—often recut, sometimes dubbed, usually promoted for shock, sentiment, and sex—were positioned for the emerging tastes of young people in cities and college towns.

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Balio offers fascinating case studies of how the films were handled well or badly. Kurosawa, he notes, had no consistent distributor in the US, and so his films gained comparatively little traction. By contrast there was what one chapter calls “Ingmar Bergman: The Brand.”

Bryant Haliday and Cy Harvey of Janus Films. . . devised a successful campaign to craft an image of Bergman as auteur and to carefully control the timing of each release. . . . Janus released the films in an orderly fashion to prevent a glut on the market and to milk every last dollar out of the box office. No other auteur received such treatment.

The work paid off: Bergman made the cover of Time in 1960, and soon The Virgin Spring and Through a Glass Darkly won back-to-back Oscars for Best Foreign Language Film. Eventually, Bergman and other foreign auteurs attracted the big studios. Now that small distributors had shown that there was money in coterie movies, the major companies (having problems of their own) embraced imported cinema—first through distribution and eventually through financing. If you admire Godard’s The Married Woman, Band of Outsiders, and Masculine Feminine you owe a debt to Columbia Pictures, which underwrote them.

Work like Balio’s does more than bring the name Cy Harvey into film history. It reminds us to follow the money. If we do, we’ll see that not every “foreign film” stands radically apart from big bad Hollywood. More generally, The Foreign Film Renaissance on American Screens reminds us that even high-art cinema is produced, packaged, and circulated in an economic system. The distinction between commercial films and personal films, business versus art, is a wobbly one. Rembrandt painted on commission and Mozart was hired to write The Magic Flute. Sometimes good art is good business.

I couldn’t work this in anywhere else: The bulk of the essays in Arnheim for Film and Media Studies are by people associated with our department at Wisconsin. They do us proud, naturally. Incidentally, Joe McBride went to school at UW too, and Tino and I taught together here for over thirty years.

Dave Kehr maintains a blog and teeming forum here.

Hart Perez has made a documentary, Behind the Curtain: Joseph McBride on Writing Film History. An excerpt is here. McBride’s website has information about his many projects.

James E. Cutting provides an unusually precise account of canon creation in his 2006 book Impressionism and Its Canon, available for free download here. I’ve written an earlier blog entry discussing Jim’s research into film.

My mention of American generations is based on Elwood Carlson’s study The Lucky Few: Between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boom. Carlson examines the varying experiences and life chances of people who fought in World War II; people who came of age during the 1960s; and the less populated cohort that fell in between. Doing some pop sociology, I’d hypothesize that the art-film market’s growth relied on a convergence of all three, which were more disposed to art film than cohorts in earlier periods. For example, veterans who had served overseas and gone to college on the GI Bill were more familiar with non-US cultures than their parents and, I surmise, weren’t entirely put off by foreign films. When I first met Kristin’s mother, Jean Thompson, she already knew the work of Carl Dreyer, having seen Day of Wrath at an art cinema in Iowa City. She was in graduate school after World War II, on the G.I. Bill, as was her new husband, Roger, also in school on the G.I. Bill and managing that art cinema. They saw Children of Paradise and other wartime foreign films just getting their releases in the U.S., as well as post-war films like Bicycle Thieves.

The Lucky Few, also known as the Good Times generation, were born between the late twenties and the early 1940s. They were well placed to enjoy postwar prosperity and the period’s explosion of artistic expression. The Lucky Few cohort includes powerful film critics like John Simon (born 1925), Andrew Sarris (1928), Richard Roud (1929), Eugene Archer (1931), Susan Sontag and Richard Schickel (1933), and Molly Haskell (1939). Aged between twenty and thirty when the foreign-film wave struck, they were mighty susceptible to it. (Pauline Kael, though born in 1919, had a delayed career start, entering film journalism in the 1950s along with Sarris et al.) You might slip in David Thomson (born 1941), Jonathan Rosenbaum (1943), and Richard Corliss (1944).

The Baby Boomers jumped on the carousel in the 1960s, with results that are all too apparent. Dave Kehr and Joe McBride are Boomers, as are Kristin and I. Tino, for the record, is ageless.

Minority Report.

A hundred years, plus a few thousand more, in a day

Charlie Keil, Yuri Tsivian, Henry Jenkins, Kristin Thompson, and Janet Staiger. Photo by Joel Ninmann.

Last Saturday we held the symposium “Movies, Media, and Methods” in honor of Kristin’s arrival at age sixty. Four distinguished scholars, all professors from major universities, presented top-flight talks. As a bonus, Kristin gave The Film People a glimpse into her Egyptological work. I report on this very full day in the hope of giving a sense of how stimulating we found it.

Thanhouser was an American film company that flourished between 1909 and 1917. It has been overshadowed by Biograph because that firm put out more films and, not incidentally, employed D. W. Griffith. But Ned Thanhouser has been diligently gathering his family company’s output from archives around the world and releasing it in informative DVD editions. The most famous Thanhouser production is probably Cry of the Children (1912), a powerful attack on child labor. You could also try the thriller The Woman in White (1917), adapted from Wilkie Collins’ masterful novel. A study in sadism, and more subtle than The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Charlie Keil, an expert in 1910s US film from the University of Toronto, examined Thanhouser’s films with two questions in mind. Did the studio have a “distinctive personality” in its products? And does its output reflect the development of film style across the crucial transitional years of the early 1910s? Borrowing a method that Kristin had applied to Vitagraph films in an essay, Charlie took one film from 1911, one from 1912, and one from 1913. Charlie wasn’t ready to conclude that these specimens displayed a unique studio style, but it was clear that across just three years, big changes in storytelling were taking place.

The plot of Get Rich Quick (1911) involves a man who joins a business that is scamming innocent investors. The film uses only five locales and plays scenes in long takes. The Little Girl Next Door (1912) has a more complex plot, with two distinct lines of action that converge on a child’s drowning. It uses many more locales and an ellipsis of a year to trace the changes in a family’s fortunes. It also incorporates cut-in close views and point-of-view editing. The Elusive Diamond (1913) is less psychology-driven than The Little Girl Next Door, but its intrigue relies almost completely on dialogue titles and it includes many close-ups and variation of camera setups.

Three films and three years: A vivid cross-section of the rapid development of what soon became classical visual storytelling. Moving from 18 shots to 53 shots to 74 shots, the films became less dependent on staging and more dependent on editing. At the same time, Charlie didn’t fail to notice how the long takes in Get Rich Quick allow some felicities of performance, particularly the way that the wife’s handling of her apron charts her psychological states. She brushes it aside to show how poor they are, then she uses it as a giant hankie.

Like all good papers, Charlie’s left a lot to be discussed. People asked about how much pre-planning was done at Thanhouser, about the directors and screenwriters on staff, about the division of labor. We were left with a sense that here was another mostly unknown region that would reward further study.

Fernand Léger, Cubist Charlot (1923).

Yuri Tsivian of the University of Chicago carried us into the twenties with an in-depth examination of early Russian reactions to Charlie Chaplin. The paper held many surprises. Chaplin was popular in many countries from 1915 onward, and very soon after he was celebrated by European intellectuals. But Russia lagged behind; there’s no concrete evidence that any Chaplin films were shown there until 1922. Yet the Soviet avant-garde embraced him. How and why?

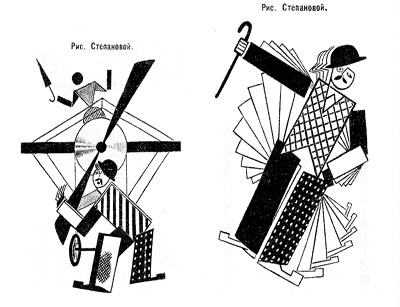

Instead of looking for a dual relationship—Chaplin directly influencing Russian artists—Yuri postulated a “triangular” relationship, in which Chaplin’s image was mediated through other European sources. For instance, Léger’s numerous images of a fragmented Chaplin led Futurists and Constructivists to declare Charlie “one of us.” They loved the idea of man as a machine executing precisely articulated movement, and what they heard of Chaplin’s pantomime and gags led them to praise him. Chaplin, said Lev Kuleshov, is “our first teacher” because he knows bio-mechanical premises better than anyone. According to the photographer and graphic designer Rodchenko Chaplin instructs viewers in how to walk or put on a hat in the most perfect manner.

So strong was this “virtual” image that artists could read Chaplin into the slapstick comedians they did see. Yuri showed that Varvara Stepanova’s striking rendition of Chaplin as an airplane propeller derived from a film he wasn’t in!

Perhaps she didn’t care: Nikolai Foregger suggested that Chaplin himself was unimportant, that the crucial fact was that he created a whole school of comedians within what Yuri called “a collaborative research community”—that is, Hollywood!

Yuri’s paper, in homage to the Russian Formalists, invoked the “law of fortuity” in art. This refers to the possibility that artistic borrowings, blendings, and crossovers are not determined by any broader social processes, as the Marxists were arguing, but are merely contingent. “Life interferes with art from below.” Accidents and unforeseen intersections, such as the Chaplin craze meeting the Constructivist movement, allow artists to seize on whatever is around them for new material. Yuri’s reference was to Kristin’s revival of Formalist methods in her “neoformalist” studies of Eisenstein, Tati, and other filmmakers.

Janet Staiger of the University of Texas at Austin collaborated with us on The Classical Hollywood Cinema, and she has for several years been the leading scholar of reception studies in film and television. In looking at the Indiana Jones series, her paper nodded to Kristin’s work on the Lord of the Rings franchise and her study of fans’ responses to the films.

“Nuking the fridge,” Janet explained, has become fan jargon for an outrageous plot twist. The phrase comes from a notorious moment in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), in which Professor Jones escapes an atomic blast by diving into a lead-lined refrigerator. The moment becomes a crux for clashing fan judgments: This is totally unrealistic vs. Realism doesn’t matter. Janet went on to show how these and other fan responses, entwined in IMDB commentary threads, utilized several different interpretive frames.

One was authorship. Like academics and journalists, fan are auteurists. They assign the director responsibility for major aspects of the film. But this doesn’t mean that they agree in how to use this frame. In the case of Crystal Skull, a certain Kid Mogul asked if Spielberg’s willingness to reinvigorate the franchise was purely mercenary: “Is it just about the money?” Others took a more career-survey approach, noting that after prestige pictures like Schindler’s List Spielberg recalibrated his popcorn movies, particularly by handling violence more gingerly.

Another frame was story-based “lit talk.” Fans disparaging the film found it clumsily plotted and lacking in character development. Several were quite sensitive to narrative coherence, one-off gags (such as nuking the fridge), and pacing. Those defending the film appealed to the emotional burst of the final chase scenes.

Janet’s third frame of reference was what she called “formula dissonance.” She sought to capture what seeing the film would be like for those who knew Indy’s story only through the TV series or video versions of the earlier installments in the franchise. She suggested that the formula was by 2008 quite abstracted and idealized for many fans. Their sense of the franchise was thus tested by the extraterrestrial twist that resolved the Crystal Skull plot. Does it reframe the whole series in a cosmic context, or is it a violation of the premises of the Indy universe?

Janet’s survey of these types of responses made me notice that the assumptions of academic film studies and of journalistic criticism overlap with fan conversation. Fans who liked the film tried to make everything fit by appeal to organic unity, technical proficiency, emotional intensity, and other familiar criteria. It made me suspect yet another reason why “amateur” and “professional” film criticism seem to be merging: Perhaps their conceptual frames of reference aren’t so far apart. But their tastes and their degrees of commitment surely are.

You might have expected Henry Jenkins of the Annenberg School at the University of Southern California to talk about fans too. After all, he practically invented the modern study of media fandom with his book Textual Poachers, and his work influenced Kristin’s study of fan promotion of The Lord of the Rings. Instead he turned to a survey of an artist’s oeuvre. He showed how Kim Deitch’s vast output of stories appropriate imagery from nineteenth and twentieth century mass media and present highly personal versions of the history of popular culture.

In a way, though, Henry’s talk involved fandom because Deitch is himself a prototypical fanman. He’s an obsessive collector, likely to turn his search for a rare toy or drawing into a Byzantine odyssey on the page. Fascinated by Hollywood scandal, he has constructed a phantasmagoric history of mass media through fictional characters (e.g., fake movie stars) who confront real people (e.g., Fatty Arbuckle). He’s particularly concerned about what he takes to be the warping of animated film by the influences of the mass market, epitomized by the Disney empire. The emblematic moment in Boulevard of Broken Dreams comes when Deitch’s Winsor McKay stand-in addresses torpid animators at a tribute dinner and denounces them for selling out.

Deitch’s most famous character is Waldo the cat, and Henry traced the powerful connotations of this emblematic figure. Waldo recalls Felix, the most heavily merchandised comics figure before Mickey, as well as the black cat as a figure of deception, witchcraft, and even African-American minstrelsy. Through Waldo, Deitch could hop across the history of film and comics, from McKay to Mighty Mouse and 1940s abstract films. In Alias the Cat!, Deitch finds in the 1910s everything that we associate with media today: serial narrative, stories shifting across different media platforms, an uncertain line between publicity and self-expression, and a mixing of news and sensational fiction.

Henry situated Deitch in a broader trend of comic artists trying to find a new history of their medium, one that dislodges superheroes from a central role. Deitch’s themes of old-fashioned craftsmanship, lovably antiquated technology, adult dread and degeneracy lurking behind children’s stories, and the commodity demands of comic art link him to contemporaries like Chris Ware and Art Spigelman.

Henry’s talk spurred a lot of discussion, including the question of whether we can treat an artist as offering a history that is comparable to academic research. Can Deitch’s hallucinatory vision of American media be a plausible basis for understanding what really happened? On the whole we don’t expect an artist to offer rigorous arguments. An artwork appropriates history for its own end. (Not all the Greek philosophers actually gathered together in the way Raphael depicts them in the School of Athens painting.) How cogent you find Deitch’s critique probably also depends on whether you share his disdain for Disney. His floppy-limbed denizens fuse headcomix grotesquerie with the 1930s animation that most prestige studios abandoned. As in Sally Cruikshank’s sprightly cartoon Quasi at the Quackadero, Deitch’s rubbery frames revive a style in which everything seems to throb and shimmy.

Kristin’s talk, “How I Spend My Winter Vacations: The Amarna Statuary Project and Techniques of Visual Analysis,” had two parts. In the second part, she reviewed her recent work in assembling statues out of tiny bits that had been dumped by archaeologists decades ago. You can read some of this story here. The side of her work most intriguing to students of film, I think, involves her attraction to Egyptian art in the first place.

Egyptian art is often thought of as unrealistic, but during his reign in the fourteenth century BCE the pharaoh Akhenaten introduced a peculiar sort of stylization into it. When he instituted a monotheistic religion centered on the sun god Ra (embodied in the Aten), he also demanded a new pictorial style. Thus the Aten is depicted as a disc shedding rays, a symbol of life and dominion. In addition, the royal family displays biggish hips and thighs, which fit the fecundity theme. More strikingly to our eye, Akhenaten’s family were represented as somewhat distorted, with long and narrow faces, hands, and feet. The ruler’s crown is elongated as well. Several aspects of the new style are present in Kristin’s favorite scene, a beautiful relief carving known as the Berlin family stela.

You can see the Aten’s rays ending in little hands holding ankh signs to the royal couple’s noses. But just as important is the human dimension of the scene, and two sorts of action displayed there: swiveled shoulders and pointing hands.

Unlike the flat, frontal portrayal we associate with Egyptian art, the family members are caught in twisting postures that bring one shoulder forward. Kristin explained:

Akhenaten is lifting his daughter, his foreground arm moving backward to hold her legs, the other moving forward to support her body as he kisses her. She reaches with her rear arm to chuck him affectionately under the chin, while her other arm moves backward in a pointing gesture. On the opposite site, Nefertiti’s foreground arm is held bent and backward to steady the youngest daughter of the three present, who is standing on her thigh and reaching up rather precariously to grab a golden decoration hanging from her mother’s crown. Nefertiti’s rear hand goes forward to steady the second daughter, who is also pointing, this time with her rear arm as she twists to look at her mother. These kinds of gestures can be found again and again in such scenes.

The twisting movement wasn’t unknown among images of workers and private individuals; Amarna artists, presumably encouraged by Akhenaten, applied the device to portraying the royal family.

Just as significant are the pointing gestures we find in the stela. Some scholars have interpreted them as protective gestures, which are found in other images. But Kristin points out:

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

In those cases, the protecting figures hold their arms straight, they stare in the direction of the thing to be protected (as one presumably would in reciting a spell), and there is something dangerous present. None of this applies in the scene in the stela.

After pondering this scene quite a lot, it occurred to me that it looked like a really early film, a short scene, perhaps 30 seconds long, that we were to interpret as a tiny narrative. The pointing gestures seemed comparable to pantomime, where one has to interpret movements in the absence of intertitles.