Archive for the 'Directors: Stahl' Category

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

More Bologna bounty

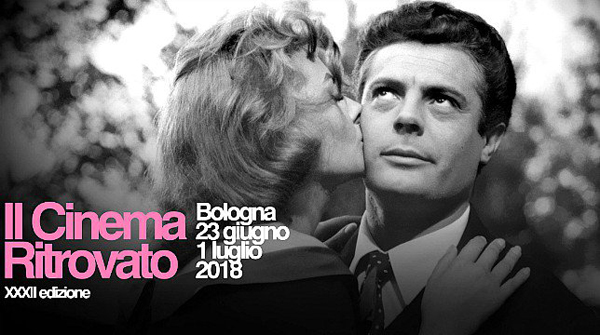

I think this has become my favorite Ritrovato key image.

DB here:

Cinema Ritrovato rolls on, leaving your obedient servant little time to blog. Herewith some quick impressions on a thin slice of all that’s going on. For a full schedule of this incredible event, go here.

IB or not IB

“Not all IB Tech prints are created equal,” explained Academy Film Archivist (and UW–Madison grad) Mike Pogorzelski. In his last of his annual Technicolor Reference Print shows, he pointed out that Technicolor sent its best-balanced prints to big-city venues and circulated them widely. As a result, they got worn out. The prints most likely to survive were less-than-perfect ones sent to the hinterlands or just kept as backups. Hence the need to preserve the Reference Prints selected by the filmmakers as defining the Technicolor timbre of each film.

With clips ranging from The Godfather and Let It Be to Sssss and Billy Jack, the sample gave a good sense of what Tech looked like a few years before the imbibition (IB) process was abandoned in 1974. Mike and Emily Carman introduced the extracts with informative commentary. I had always thought that Gordon Willis’s cinematography on the Godfather films and The Parallax View increased graininess, and this show seemed to confirm that sense.

Those naughty pre-Code pictures, again

The John Stahl and William Fox retrospectives brought some spicy material. Women of All Nations (1931), Raoul Walsh’s episodic sequel to What Price Glory?, had Quirt and Flagg on the verge of all-out cussing in nearly every scene. A monkey wriggling inside El Brendel’s trousers created moments of good dirty fun. Bachelor’s Affairs (tee-hee, 1932) had Adolph Menjou peering down a golddigger’s front and praising her virtues: “What a charming combination.” She asks if it’s showing. Likewise this repartee: “Were you out last night?” “Not completely.”

William Dieterle’s Germanic Six Hours to Live (1932) begins as a political thriller and devolves into a Twilight Zone fantasy. A representative of a small country passionately protests worldwide tariff legislation. To keep his vote from vetoing the action, spies target him for elimination. Soon enough, he’s throttled to death. But an enterprising scientist takes the opportunity to try out his resuscitation ray, which gives the hero a few more hours to make his mark.

John Seitz photographed the whole farrago in glowing imagery shot through with shafts of blackness, alternately soft-focus and crisply edged. Here’s the magic machine.

The film’s look is an example, I suppose, of what Andrew Sarris once called “Foxphorescence”–the signature of a studio that, from Murnau and Borzage to Ford and 1940s noirs, played host to dazzling pictorial effects.

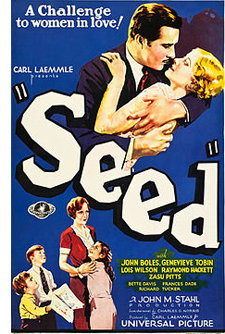

Not completely naughty, but certainly a film about sexual jealousy, was Seed (1931), one of the most anticipated films of the Stahl cycle. It lived up to its reputation as a masterly orchestration of sympathies. At the center is a love triangle based on two women’s roles: the mother and the businesswoman.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

Aspiring author Bart Carter has given up his novel, and he lives–he thinks–happily with his wife Peggy and five rambunctious kids. When his old flame Mildred returns to the publishing firm Bart works for, she encourages him to keep writing and to stray from the household Peggy has made for him.

As often happens in Hollywood, the plot works only if the man is a jerk, and the action will set up things to make the woman take the blame. Mildred may not have schemed to pull Bart away from the start, but the shift in our sympathy to Peggy is pretty decisive. The film’s patient pace and stringently objective presentation lets contrasting feelings get developed gradually. The kids, particularly the whining runt of the litter, are annoying and troublesome. Mildred is no obvious predator, Peggy is trying valiantly to accommodate Bart’s ambition, and he’s enjoying his vacation from fatherhood while still struggling, albeit weakly, to stay loyal to his family.

Stahl was one of the major long-take directors of 1930s Hollywood, and Seed is exemplary in this respect. (The average shot lasts about twenty seconds.) His back-to-basics two shots, facing off characters in profile, become the default setting; there are scarcely any reverse angles or eyeline matches. This apparently simple creative choice, anticipating Preminger’s method of the 1940s and 1950s, puts all characters on an equal footing. The framings force us to concentrate on their conversation, avoiding the customary cuts that punch up particular lines or reactions. A similar steady observation is at work in Stahl’s fine Imitation of Life (1934) and Magnificent Obsession (1936).

1918 and all that

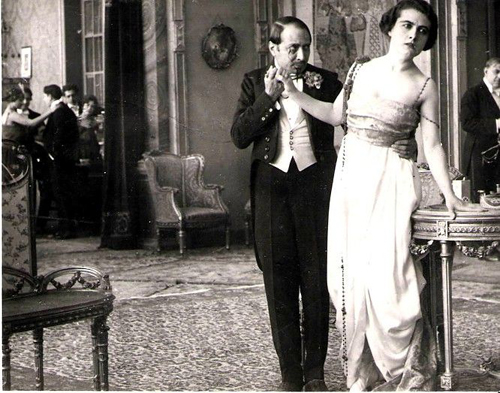

L’avarizia (1918). Production still.

Regular readers of this blog know that one area of my research is the stylistics of 1910s cinema in various countries. (Check the category tableau staging for a sample.) Naturally I dropped obsessively in on the 100-years-ago strands at this year’s Bologna. While there are more films to come, I found plenty to enjoy and think about in the first few days.

There was, for instance, Der Fall Rosentopf, a fragment of a farcical Lubitsch feature. Ernst plays his Sally character, now a detective investigating a flower-pot mystery. Lively enough, the surviving nineteen minutes from early scenes didn’t give me much sense of the whole.

Alongside it were two other comedies. Gräfin Küchenfee featured Henny Porten in a dual role, both countess and kitchenmaid. When the countess goes off to have fun, the maid assumes her identity. Eventually, the two women switch roles when the countess tries to evade police charges by pretending to be the maid. No less predictable in its comic situation was Puppchen, in which a young woman working in a fashion salon breaks a lifelike mannequin and must take its place. It may have been a model for Lubitsch’s Die Puppe (1919).

Stylistically, all these films were fairly staid, with little intricate staging, and they lacked analytical editing apart from axial cuts in and out. Their reliance on longish takes probably reflected the fact that US films, with their bold continuity editing, weren’t available in Germany until somewhat later.

One American film also rejected the emerging Hollywood style, in the name of naivete and fancy. That was Prunella by Maurice Tourneur. It doesn’t survive complete, and it’s been known for many years as a failed venture into artiness. The flat sets resemble children’s book illustrations, and the performance style is wilfully arch. I’ve never found Prunella very interesting, but it does offer further evidence that the 1910s harbored some eccentric and ambitious experiments.

Gustavo Serena’s L’Avarizia impressed me more. It too relies on frontal acting and axial cutting, but as a vehicle for the great diva Francesca Bertini it seemed to me completely engrossing.

As part of a series illustrating the Seven Deadly Sins, it offers a starkly symmetrical plot. Maria and Luigi love each other, but each is dominated by an old miser. Her aunt and his father each amass a fortune in secret while manipulating the young people. Through a series of conspiracies and misunderstandings, the lovers are flung apart. Maria, friendless and illiterate, sinks down, down into the bottom of society.

Each step of the way is given powerful expression by Bertini’s face, gestures, and bearing. She grabs her hair to yank her head back; she blows cigarette smoke in Luigi’s face to show her contempt for his abandonment of her. At one high point, when Luigi falsely accuses her of infidelity, she wrestles with him on a tabletop, giving no quarter. In a tavern fight she pulls a knife before falling to the floor, writhing feverishly in what appears to be her last moments on earth. This is silent opera, with the soaring melody carried by the body.

Up against the fourth wall

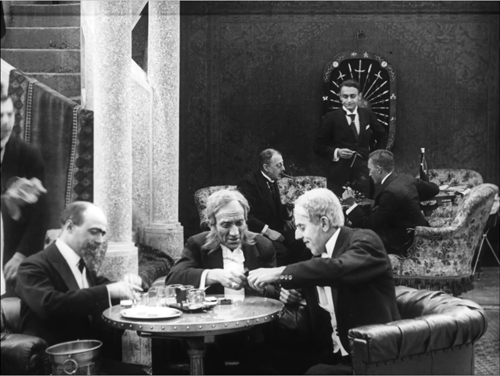

A meeting of the Antifeminist Club (The Oriental Language Teacher).

I wasn’t surprised to find a diva film full of sensuous appeals, but the big revelation of the 1918 cycle so far was the Czech comedy The Oriental Language Teacher (Učitel Orientálních Jazykû). It showed what you could do with a small cast, a few sets, and a cut-and-dried situation.

Sylva secretly falls in love with Algeri, who’s tutoring her in Turkish. After her father is being considered for a diplomatic post in Turkey, he decides to learn the language. He arrives during one of Sylva’s lessons, so she quickly disguises herself as an odalisque. Needless to say, Father is smitten with this exotic beauty. Add in his membership in the Antifeminist Club, led by a comic geezer who enjoys snapping clandestine photos of passing women, and insert deceptions involving a pianola roll, and you have some substantial complications.

Most striking from a pictorial standpoint were the very deep sets–modeled, stylistic historian Radomir Kokes tells me, on the Danish cinema of the period. The co-directors Olga Rautenkransovå and Jan S. Kolár present Sylva’s parlor in an unusual way. Most films of the period put foreground desks and tables at a diagonal bias. But here the father’s desk is thrust very close to us, perpendicular to the camera, and it runs the entire length of the frame.

Moreover, the father is centered at his desk, when the more normal placement would set him to left or right and clear a space in the other half of the frame for other characters. The depth, that is, is typically horizontal. Here, though, it’s also vertical. A character must descend the stair directly above the other, in a maniacally centered composition that’s mildly beguiling in itself.

The set depicting Algeri’s studio is a little more typical of the period, since his desk is placed off to one side, but every shot of this setup makes the foreground area curiously out of focus.

Given that the control of focus is precise in the parlor shots, the slightly fuzzy foreground of the studio set remains anomalous–an error, or a decision to differentiate the two spaces more sharply. In any case, here’s another example of how 1910s movies, from all corners of the world, can set you thinking about the possibilities of pictorial design.

More to come in the next entry, with a special focus on trial films.

Special thanks to Radomir Kokes for help with this entry. More generally, thanks to the Bologna leaders and staff for a tightly-run and ever-exciting event, along with the archivists who made these films available. In particular we owe a lot to Marianne Lewinsky, who curates the Cento Anni Fa series, and to Dave Kehr who, grinning, shares what he called on the first day MoMA’s “mildly obscure” treats. And Imogen Sara Smith gave an exceptionally lucid introduction to Seed.

For more on diva acting, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema, a book available here, and this entry by Lea on Bertini. Kristin wrote about Prunella and other mildly experimental Hollywood films in Jan-Christopher Horak’s Lovers of Cinema collection.

For more on-the-spot pictures, check our new Instagram page.

John Bailey, President of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, and Michael Pogorzelski.