Archive for the 'Directors: Tarantino' Category

THE HATEFUL EIGHT: The boys behind the booth

DB here:

By now everybody knows that Tarantino’s forthcoming The Hateful Eight was shot on film in the Ultra Panavision 70 format. This anamorphic widescreen process yields a projected aspect ratio of 2.76–in a word, humongous. An early version of it, MGM Camera 65, was employed on Ben-Hur (1959), but Panavision quickly developed a new generation of cameras and renamed the process. It wasn’t heavily used; supposedly Khartoum (1966) was the last film shot in the format.

The process by which Tarantino, ace cinematographer Robert Richardson, and the enthusiastic boffins at Panavision revived Ultra Panavision 70 is detailed in the current American Cinematographer (alas, not yet online). The production is an extraordinary tale. But what about exhibition? Luckily, the widescreen fans among us can glean a lot about that from veteran projectionist Paul Rayton’s interview with Chapin Cutler, co-owner of Boston Light & Sound. It was the task of Chapin and his team to find over 100 projectors, refurbish them, test them, and set them up in theatres all over America.

Chapin is a legendary figure in movie exhibition. Trained as a projectionist during his college years, he and Larry Shaw have made BL&S one of the very top companies for installation and maintenance of theatre projection equipment. He has supervised theatrical setups at festivals (Sundance, Telluride, TCM), industry gatherings (CinemaCon), and at some of the world’s top-notch theatres.

He’s more than a professional’s professional: He loves film and prides himself on delivering a powerhouse show. He was a natural choice for a movie geek like Tarantino to arrange the roadshow screenings of The Hateful Eight.

Chapin has discussed the nearly military precision necessary to fulfill Tarantino’s mandate in The New York Times and The Boston Globe. You should read these pieces for essential background. When Chapin added some new information courtesy of the listserv of the Art House Convergence, I jumped at the chance to include you in the audience. I know that many of our readers are keen to devour whatever they can learn about this film, one of the year’s major American releases.

So here are Chapin’s notes on how you prepare and ship out 100+ 70mm film prints.

For those of you that are interested in these things, attached is a picture of our “platter farm” in Valencia CA. This is where all the prints are being made up.

The space before, in Academy ratio.

The space after, in sort of Ultra Panavision.

We are getting the prints as 1000 ft. loads, so we have to assemble 20 rolls to make a print up.

About 90 of the prints will be made up for platter operation and shipped totally assembled. The prints are being ultrasonically welded so that it is one continuous piece of film; no splices. The remaining prints are going out for reel to reel houses.

On the right of the frame above you can see part of one of the shipping cases. It is 5 ft. x 5 ft. by 1 ft. thick. When loaded, it weighs about 400 lbs. On the platter next to it, there is a partially disassembled platter reel. With the reel full, out of the box, the film and reel weigh about 250 lbs. Four people can easily lift it onto a platter deck.

We have a dedicated team of four folks working 7 days a week to get this done.

All this makes you appreciate the effort behind the scenes that makes this remarkable enterprise work. (So far, there have been a couple of problematic press screenings, but a dozen or so other shows–notably last night’s SAG screening at the Egyptian–have gone off perfectly.) Whatever you think of Tarantino as a filmmaker (I like him), he deserves credit for exposing a new generation to the volcanic fun of a roadshow presentation. And we should thank Chapin, the guru with the bandit mustache, as well.

Photo credits: Chas. Phillips.

The Hateful Eight.

The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks

Pulp Fiction (1994).

Trigger warning: This blog is about Quentin Tarantino, Walt Disney, and Henry James. Those who find violent analogies disturbing should avoid what follows.

DB here:

Every narrative film is made out of parts. Normally they just whisk by us, but sometimes our attention is called to them as parts. Occasionally, we sense that the whole movie is made out of large-scale chunks.

Take Pulp Fiction (1994). It consists of scenes grouped into larger blocks, some marked by fade-ins and outs and others with titles, like chapters in a book. The diner opening is set off as a unit before the credits. The ensuing visit of Jules and Vincent to the apartment of the welshing punks is ended in a fade-out. We then get a section tagged “Vincent Vega and Marsellus Wallace’s Wife.” After that portion fades out, there follows a sequence introducing the young Butch as a boy, presented with his father’s gold watch. Then Butch, now grown up, heads out to the boxing match. Another fade, and we get a title, “The Gold Watch.”

That could be seen as simply a belated chapter head for the entire Butch section, boyhood and prizefighting career. Or it could mark the start of another, much longer block: the aftermath of the fight and Butch’s flight from Marcellus Wallace. Either way, the sense of a film composed of large-scale parts is very strong. As the film goes along, we realize that each block tends to concentrate on certain characters and provide distinct, sometimes overlapping, stretches of time.

For many viewers, I suspect, Pulp Fiction was their introduction to strategies of block construction in movies. Those of us studying film history had seen it in various guises before, but seldom so cleverly and explicitly worked out as in Tarantino’s film. And I’m not sure even film historians realized how much Tarantino owed to earlier traditions.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I suggested that some of the experimental trends in 1990s-2000s cinema were indebted to Hollywood in the 1940s. This is especially evident in the neo-noir films of those years, like The Underneath (1995), The Usual Suspects (1995), and Memento (2001). Now that I’m writing a book on that earlier period, I realize that studying the 1990s films, has led me to think about something that I hadn’t noticed—how interested 1940s filmmakers were in building movies out of blocks.

Turns out that the 1940s was a kind of golden age of block construction. And Tarantino serves especially well to illustrate how that strategy can be put to use in modern times. In fact, his work is a fairly comprehensive layout of the creative possibilities of the format.

Building blocks

Some basic options for block construction were laid out fairly early in the silent era. The most famous instance was Griffith’s Intolerance (1916), which sampled four historical periods, each harboring its own distinct story. He then crosscut the four epochs, building to four “simultaneous” climaxes at the end of the film. Griffith managed to secure an unprecedented level of suspense by alternating portions of his blocks.

Griffith also wanted to prove a conceptual point, that intolerance reappeared at different times in different guises. He understood one of the major attractions of block construction: It asks us to compare and contrast.

Griffith also wanted to prove a conceptual point, that intolerance reappeared at different times in different guises. He understood one of the major attractions of block construction: It asks us to compare and contrast.

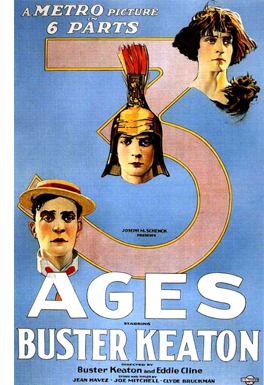

Directors who wanted to achieve the same comparison among different historical periods took the more obvious option and laid each separate story out, one after the other. We see the result in Dreyer’s Leaves from Satan’s Book (1920), Lang’s Der müde Tod (Destiny, 1921), and The Three Ages (1923), Buster Keaton’s parody of Intolerance. So this construction by integral blocks of time, laid end to end, was useful for comparing several self-contained stories.

Can you get the same sort of effect when sections of the same story are separated out in blocks? Yes, you can. The classic example would be parallel flashbacks. In Citizen Kane, an ongoing present, the reporter Thompson’s investigation, brackets long flashbacks that serve as parallel architectural parts—trips to the past, showing Kane as seen by others. We’re coaxed to compare Kane’s actions at different points in his life, as well as the various sides of him seen by his associates.

Here, as sometimes happens, the blocks are marked off not only by time period but by varying viewpoints. The alternation between the present and long stretches of the past, focused around one character and then another, characterizes many 1940s flashback films, such as The Killers (1947) and A Letter to Three Wives (1949).

Tarantino made alternating block construction the basic principle behind Reservoir Dogs (1992), which shuttles between the aftermath of a botched robbery and the planning that led up to it. One model he has acknowledged is Kubrick’s The Killing (1955), which itself transposed into cinema the overlapping point-of-view blocks that were present in Lionel White’s source novel Clean Break.

Elsewhere on the blog I’ve talked about how flashbacks can be nested inside one another, like Russian dolls. Examples from the 1940s include Passage to Marseille (1944) and The Locket (1946), and these lengthy sections surely count as blocks. Here the blocks serve less to compare dramatic situations than to fill in backstory. The blocks are lumps of exposition. In addition, blocks also can usefully delay events, creating suspense and padding the plot to its proper length. (Form often follows format.)

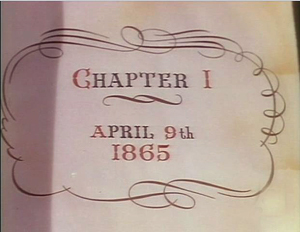

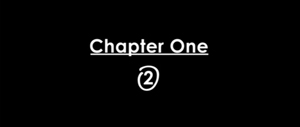

Tarantino embedded flashbacks within flashbacks in Kill Bill Vol. 1 (2003) for just these purposes. Let’s assume that the early sequence (Chapter One) showing the Bride attacking and killing Vernita, her second victim, is a benchmark for the narrative present. That ends with her reading her list of targets. Chapter Two, which follows, initiates a flashback going back several years. In the course of that, the Bride escapes from the hospital and sets out to kill O-Ren, who’s her first victim. And in the course of that long flashback, framed by the Bride lying in the Pussy Mobile, we get a nested one, dubbed “Chapter Three: The Origin of O-Ren.” That eight-minute anime fills in the life story of the queen of the Tokyo underworld before we return to the Bride’s quest for her.

The anime sequence is closed off by a return to the Bride recovering in the Pussy Mobile.

The flashback-within-a-flashback supplies exposition, creates a parallel to what we’ve seen at the film’s start (Vernita’s little daughter discovering the Bride’s murder of her mother), and sharpens our curiosity about the Bride’s trip to Japan. We stay in that Japan-related flashback for the rest of Vol. 1. The plot won’t take us back to the present, after the Bride’s killing of Vernita, until the black-and-white beginning of Vol. 2.

A trickier Chinese-boxes structure appears in Reservoir Dogs. The present-time situation is the gathering of the surviving hoods in the warehouse. There are flashbacks to the planning stages of the holdup, each attached to one man’s viewpoint and tagged with his alias.

In the flashback attributed to Mr. Orange, the police mole, we start with him identifying himself to the tortured cop in the warehouse. We move to the past, when Mr. Orange meets a contact in a diner and explains that the gang took him in. That leads to a nested flashback showing him at his audition.

To gain the gang’s trust, Mr. Orange tells a heavily rehearsed fake anecdote about evading the cops during a drug swap. And even that gets an embedding: the false anecdote is presented visually, as a scene in a men’s toilet.

Then we come out of the nested flashbacks in proper order: back to the meeting with the gang, then to the diner, and several scenes later, back to the present situation in the warehouse.

A lying flashback is embedded in a flashback that’s itself embedded within a flashback. The whole shebang becomes a complex block labeled “Mr. Orange.”

Most flashback films use the trips to the past to revisit characters known to us in the present. But some films use the flashback option to tell independent stories. Forever and a Day (1943) is a biography of a house, supplying a history of the house from its origins to its sufferings during the Nazi bombing of London. An even clearer example is Tales of Manhattan (1943). It traces how a coat of tails is passed down the social pecking order, from an elegant actor to a sharecropping community. No characters tie the episodes together, only the coat and some thematic motifs. Again, the blocks encourage us to contrast how different social classes use the tailcoat.

I don’t find Tarantino picking up this circulating-object idea, but it has been reused in Twenty Bucks (1993), American Gun (2006), and other films. Somewhat in the same spirit, though, is Tarantino’s Death Proof, the second feature in Grindhouse (2007). The first half of the original theatrical release concerns four young women who are targeted by Stuntman Mike, a free-range master of vehicular homicide. All the women are killed, but in the second half Mike meets his match in a quartet of car-crazy film staffers, one of whom is a stuntwoman while another is an expert driver. Mike is like the coat of tails in Tales of Manhattan: the only link between the film’s episodes.

Flashbacks can, of course, be much briefer, and when they are they don’t usually have the heft of blocks. But when a scene is replayed as a flashback, both the replay and the original scene can stand out. The flashback replay of the murder of Monty in Mildred Pierce (1945) gains a certain solidity, since it reveals things that were suppressed (and fudged) in the first go-round. (Go here for the entry and the analytical video discussing these scenes.) Another example is the conflicting testimony that includes a lying flashback in Crossfire (1947).

Pushing beyond his predecessors, Tarantino tries a more elaborate replay in Jackie Brown (1997). He presents the shopping-mall money exchange three times, from different characters’ attached viewpoints. The side-by-side replays make the whole money drop stand out as a block, as does the chapter title (“Money Exchange: For Real This Time”) and the length (over twenty minutes). A practice session for the exchange forms a parallel block, with its own introductory title (“Money Exchange: Trial Run”).

Episodic memories

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

If flashbacks, played once or many times, provide the most common sorts of blocks, big or small, there are other possibilities. You can, for instance, build your plot out of chronological but independent blocks within the same locale and time frame. Three Strangers (1946) is a straightforward example.

A woman invites two men into her apartment and suggests they share the price of a sweepstakes ticket. They will then reunite on the day the ticket falls due to see if they’ve won. After the men agree, the plot follows all three separately, with long blocks devoted to each. Their stories don’t intersect. There is a little bit of crosscutting among them, but the characters don’t reunite until the climax.

The advantage of this diverging-reconverging construction is that you can tell several stories, each with its own dramatic arc, within a larger frame that brings them all to a decisive conclusion. If you pull it off, it can deepen characterization (we spend more time with the protagonists) and perhaps mark you as a virtuoso. A flashy example is Mystery Train (1989), which provides the moment of the story lines’ convergence as a sound rather than a face-to-face encounter.

The risk of this format is that some separate stories may seem less interesting than the others. An ordinary film moves along quickly enough that we can wait out tiresome characters or situations, but in this construction we’re stuck for a while. This cost-benefit analysis may be one reason that most Hollywood plots try to integrate their story lines fairly tightly. That way you can keep the audience aware that each scene has consequences for everything that follows.

Tarantino uses the parallel block device in Inglourious Basterds (2009). Here two main story strands—Shosanna’s efforts to elude Colonel Landa and the mission of Aldo Raine’s combat team—develop independently in lengthy scenes. There’s some alternation, but the plot lines don’t converge until the movie theatre conflagration. Interestingly, both Three Strangers and Inglourious Basterds fill out their dimensions by including minor subplots (the adventure of Archie Hicox developing its own interest in Basterds).

The simplest version of block construction lets one distinct story episode follow another. The most common case is the Hollywood musical, which contains numbers, either as stage performances or as sung-and-danced scenes. Each number tends to have an internal coherence and sharp boundaries that make it a detachable unit. (So detachable that it can stand on its own in documentaries like That’s Entertainment! of 1974 and its sequels.)

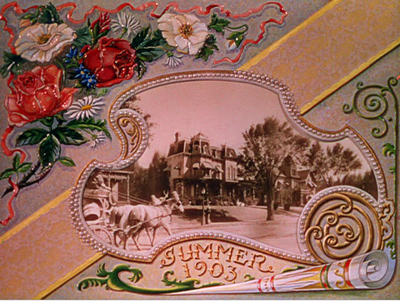

One musical that includes larger-scale segments—quite big blocks,, actually–is Meet Me in St. Louis (1944). The plot consumes about a year in the life of a family, and it opens with a candy-box title card specifying “Summer 1903.” It’s followed by two more seasonal chapters, identifying autumn and winter of the year, before we get “Spring”—a title with no date, suggesting a kind of eternal renewal that will solve the characters’ problems. Within each of these blocks, events typical of each season, including Halloween and Christmas, reinforce the sense of these as varied sections.

This sort of explicit chaptering in the 1930s-1940s is usually reserved for films framed by opening pages of a book, as in Salome, Where She Danced (1945).

Often, as in Salome, the book frame is dropped from the rest of the movie, although it might reappear to provide closure.

New forms of self-conscious chaptering became prominent in later years, as with the quotations announcing sections in Hannah and Her Sisters (1985). Most of Tarantino’s films use chapter titles to some extent, with the Kill Bill movies providing the most elaborate examples. Those films are presented as two “volumes” containing ten distinct “chapters.” Some are bulked out by flashbacks, some aren’t, but all these chapters become prominent through sheer length. Chapter Nine, which settles the fates of both Budd and Elle Driver, runs almost half an hour, and the final chapter lasts over forty minutes.

Moreover, the chapters, as in Pulp Fiction, aren’t arranged in 1-2-3 order, so we’re invited not only to compare parts but figure out their chronology. The very first chapter teases us with this problem.

The circled 2 is explained when we understand that Vernita is the second target on the Bride’s list.

Still other forms of big-chunk construction came into prominence in the 1940s. Think for instance of what were called “episodic” films, movies that inserted separate stories, often thematically connected, into a general framing structure. For example, the team that gave us Tales of Manhattan also produced Flesh and Fantasy (1943). The situation is of two men discussing superstition in a library. One takes down a book of stories and we see, enacted, three tales of the fantastic. At the end we return to the library.

This cinematic anthology was sometimes called an omnibus film, and it proved very popular around the world; examples are Dead of Night (UK, 1945) and the many Italian and French collections (e.g., The Seven Deadly Sins, 1952; Spirits of the Dead, 1968). It persisted for decades in the US (New York Stories, 1989; Night on Earth, 1992) and internationally (Paris, je t’aime, 2006). Tarantino’s contribution to the genre was Four Rooms (1995). The framing situation is that of a hotel, and three other directors contributed episodes showing what happens to various guests.

Walt Disney exploited block construction in all these ways during the 1940s. He filled out a live-action film with embedded stories (Song of the South, 1946) and interspersed cartoons with travelogue footage (Saludos Amigos, 1942). The all-animated Three Caballeros (1944; above) assembled several South American tales by means of a frame story showing Donald Duck getting gifts from below the border and dancing with his amigos. (This is a brilliant movie, as I suggest in this ancient but ageless post.)

By contrast, Make Mine Music (1946) and Melody Time (1948) give their animated musical numbers only minimal framing.

Most famous of the Disney anthologies, of course, is Fantasia (1941). Here a program of classical pieces is illustrated in cartoon sequences. The frame is provided by Leopold Stokowski at the podium and Deems Taylor, a famous music popularizer, supplying radio-style commentary in the breaks. Strange though it sounds, Tarantino (along with Robert Rodriguez) does something similar when he gives us two exploitation features, Planet Terror and Death Proof, surrounded by trailers and ads. Just as Disney posits a mock trip to the concert hall, Tarantino reimagines a night at a drive-in or an inner-city movie house.

What about Django Unchained (2012)? I think Tarantino has done something clever here. At what seems to be the climax, Dr. Schultz is killed and Django, after a fierce gunfight, is recaptured and sold to slave traders. The drama seems to be finished. But then the movie starts over, and a twenty-five-minute stretch of new action shows Django escaping the traders and returning to Candyland to wreak his revenge. Tarantino has tacked on a second, lengthy ending; block structure yields a calculated anticlimax.

Modern, middlebrow, mysterious

I guess what I’m always trying to do is use the structures that I see in novels and apply them to cinema.

Quentin Tarantino, 1993

Where did the 1940s impulse toward block construction come from? In classical Hollywood cinema, I see two primary literary sources: modernism and its offshoots in “mild modernism” (what Dwight Macdonald called “midcult”); and mystery fiction.

Fictional tales had long been broken into segments, and chapter divisions are of course very old. Assembling tales out of blocks likewise has antecedents as far back as ancient Egypt, Homer, and the Bible. Epistolary and found-manuscript fiction gravitated naturally to block arrangement. Dickens gave Little Dorrit (1855-1857) a balanced two-part layout, and he built Bleak House (1852-1853) on alternating segments in two narrative voices.

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers reflected on such problems of carpentry. Here is Henry James on carefully dividing The Wings of the Dove into discrete sections. (The italics are his.)

By the end of the nineteenth century, writers reflected on such problems of carpentry. Here is Henry James on carefully dividing The Wings of the Dove into discrete sections. (The italics are his.)

There was the ‘fun’ . . . [of treating the actions as] sufficiently solid blocks of wrought material, squared to the sharp edge, as to have weight and mass and carrying power; to make for construction, that is, to conduce to effect and to provide for beauty.

Likewise, The Awkward Age (1899) was conceived as a situation to be illuminated by different characters, or “lamps,” each participating in a single social occasion. Consequently the contents as a series of chapters (or “books”) with character titles (not unlike what Tarantino did in Reservoir Dogs): “Lady Julia,” “Little Aggie,” “Mr. Longdon,” and so on.

This sort of explicit geometry was sometimes taken up by modernist writers. Faulkner breaks The Sound and the Fury (1929) into large parts determined by place, time, and character narrators. John Dos Passos intercuts chunks of different sorts of texts (news stories, “camera-eye” views) to create the trilogy USA (1930-1036). Other modernists avoided tagging sections but made sure to give each one a blocklike singularity, as Joyce famously does with the chapters of Ulysses. Each one is keyed to a section of Homer’s Odyssey, a time of day, a symbol, and so on, and treated in a different literary technique.

Middlebrow writers, who tried to make modernism more user-friendly, seized on block construction. A prime example is Thornton Wilder’s Bridge of San Luis Rey (1927), which traces three parallel stories of people who died on the bridge when it collapsed. Less famous is Rex Stout’s fascinating How Like a God (1929), which alternates two sorts of blocks: one in italics, past tense, third-person narration, and labeled with letters of the alphabet; a second in roman type, present tense, second person (“You…”), and given a numerical order. The labels and fonts help us figure out the chronology of the story (and grasp the thoughts of the main character). Kenneth Fearing’s mildly modernist novel The Hospital (1938) borrowed from Dos Passos in shifting viewpoints among many characters, even objects, and his Clark Gifford’s Body (1942) anticipates Pulp Fiction in drastically shuffling discrete blocks out of story order.

At a more popular level, mystery fiction developed its own strategies for block construction. As a genre, mystery and detective stories are dedicated to formal play with narrative options. (Hence their interest for us narratologists.) Mysteries are frankly artificial, even gamelike, and so seek out ways to trick us.

The love of artifice often yields embedded stories, as in A Study in Scarlet (1887), and plays with point of view (famously, Christie’s Murder of Roger Ackroyd, 1926). While Dickens and James were testing block construction in the “serious” novel, Wilkie Collins was developing the “casebook” format: a collection of documents—letters, testimony, discovered manuscripts—that served as a series of blocks. Dracula (1897) also helped popularize the format. It was revived in Dorothy L. Sayers and Robert Eustace’s The Documents in the Case (1930) and Perceval Wilde’s Design for Murder (1941). And just as Stout had made typography and chapter headings formal devices, so did mystery writers use them to build suspense and their readers (e.g., Anita Boutell, Death Has a Past, 1939).

We tend to take such trickery as typical of the sleuth-and-puzzle detective tradition, but not of the hard-boiled detective tales and suspense thrillers we associate with the 1930s and 1940s. Yet writers in those traditions sometimes shift a story forward and backward in big blocks, as with Don Tracy’s Criss Cross (1934, source of the 1949 film). Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) exploited the casebook format, which was partly transposed into the film version. Kenneth Fearing, trying his hand at mystery fiction, shifted first-person narration among several characters (including a dead one) in Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946). Bill S. Ballinger’s Portrait in Smoke (1950) paralleled a first-person account of an investigation with third-person chapters that trace what happened in the past.

We tend to take such trickery as typical of the sleuth-and-puzzle detective tradition, but not of the hard-boiled detective tales and suspense thrillers we associate with the 1930s and 1940s. Yet writers in those traditions sometimes shift a story forward and backward in big blocks, as with Don Tracy’s Criss Cross (1934, source of the 1949 film). Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) exploited the casebook format, which was partly transposed into the film version. Kenneth Fearing, trying his hand at mystery fiction, shifted first-person narration among several characters (including a dead one) in Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946). Bill S. Ballinger’s Portrait in Smoke (1950) paralleled a first-person account of an investigation with third-person chapters that trace what happened in the past.

Trends in high, middlebrow, and “low” literature like crime stories had a large impact on 1940s cinema. Just as important, this formal play with narrative conventions, including block construction, continued for decades, right up to the present. Most pertinent to Tarantino is the trend toward rigorous construction we find in crime fiction from the 1960s onward.

My own favorite example is Richard Stark (aka Donald Westlake), who conceives nearly all his novels in a rigid four-part format. Tarantino seems to prefer Elmore Leonard and Charles Willeford. He isn’t given as much credit for his bibliophilia as his cinephilia, but it’s evident that he has thought a fair amount about how to bring literary techniques into cinema.

Novels go back and forth all the time. You read a story about a guy who’s doing something or in some situation and, all of a sudden, chapter five comes and it takes Henry, one of the guys, and it shows you seven years ago, where he was seven years ago and how he came to be and then like, boom, the next chapter, boom, you’re back in the flow of the action.

For example, in Rum Punch, the source novel for Jackie Brown, Leonard’s chapter-breaks usually shift our attachment from one character to another, and the new chapter may insert backstory at the start. Leaving Jackie Brown’s deal with the Feds hanging, Chapter 14 starts with Melanie sunbathing and thinking about her past. A chunk of exposition, like a film flashback, explains how she became “the tan blond California girl.” Tarantino was unusually sensitive to fiction writers’ switches in time and viewpoint, and he clearly admired the opportunities opened up by solid chapter-length blocks.

I’m not suggesting that Tarantino spends his weekends perusing Henry James or Thornton Wilder. It’s just that techniques similar to theirs have pervaded popular literature. Indeed, they were already at play in one popular genre that has always used literary artifice to shape our experience. To this day, as in King’s 11/22/63, mysteries and thrillers use block construction to promote suspense, play with alternative possibilities, make us reevaluate story situations, and engage us in a game of self-conscious form.

Sometimes current developments put the past in a new perspective. The emergence of “minimal music” (Glass, Reich, La Monte Young) suddenly showed Satie’s ideas about repetition to be more fertile than most of us had thought. Similarly, Tarantino’s work forced me to think about contemporary storytelling strategies, but it also asked me to consider more distant sources of those trends.

Studying film history is valuable for its own sake; it’s just damn interesting. Needing further justification, sometimes historians go on to say, especially to students: We study history to better understand the present. That’s surely true, but so is this: We study the present to better understand history.

Henry James’ discussion of block construction is in “Preface to The Wings of the Dove” in The Art of the Novel: Critical Prefaces (New York: Scribners, 1934), 296. Tarantino’s comments about novels and films come from Graham Fuller, “Answers First, Questions Later,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerald Peary (University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 53; Jeff Dawson, Quentin Tarantino: The Cinema of Cool (Applause, 1995), 69.

A useful discussion of how chapter divisions relate to plot is Philip Stevick, “The Theory of Fictional Chapters,” in The Theory of the Novel, ed. Stevick (The Free Press, 1967), 171-184. You can sample it here.

Neo-noir encouraged many filmmakers to explore block construction. Three quick examples: Soderbergh in Out of Sight (1998; from a Leonard book), Christopher Nolan in Following (1998), and Shane Black in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005, which split up into chapters corresponding to one popular screenplay formula). Nolan proved keenly interested in this compositional approach; see our ebook, Christopher Nolan: A Labyrinth of Linkages. More recently, Wes Anderson’s films deploy some tricky versions of block construction.

Block construction is also apparent in comic books, and Tarantino is clearly an aficionado of those traditions too. That influence should be taken into account for a fuller analysis of his narrative techniques. Also, too: The influence of Godard, especially in the “tardy” title insertions coming after the segment has started (e.g., one way to take “The Gold Watch”).

The expanded, stand-alone feature version of Death Proof displays block construction in filling out the “missing reel” portion of the first story and creating a new block, a ten-minute scene of the second “girl posse” at a convenience store. The scene starts with Stuntman Mike before shifting to the young women. It makes Mike even more a connecting link between the film’s two episodes, while Mike’s stalking and spying fulfills Tarantino’s claim that Death Proof is a slasher movie.

Embedded stories or flashbacks exemplify what researchers call “ring construction.” Bill Benzon has explored this in many critical analyses, as here with the 1954 Godzilla/Gojira.

For more on Inglourious Basterds, see our entry here and as revised in Minding Movies. We analyze the money-drop sequence in Jackie Brown in Chapter 7 of Film Art: An Introduction. Kristin discusses the titles and segmentation of Hannah and Her Sisters in Chapter 11 of Storytelling in the New Hollywood.

Thanks to participants in the 2014 conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image for their comments on some of the ideas presented here. Thanks also to Matthew Bernstein, biographer of Walter Wanger, for in-depth discussion of Salome, Where She Danced.

Grindhouse (2007).

(50) Days of summer (movies), Part 2

DB here:

How I spent part of my summer vacation: notes on three more films.

Gangbusters

Two major directors–one an emblem of goofy bravado, the other emerging as a contemporary master–gave us movies this summer, and both let me down. I have cautiously championed Tony Scott’s recent work because at least he’s willing to go all the way, however misguided the direction. From Spy Games on, he has stuck to the credo that too much is never enough. His technique is swaggering and undisciplined, mannered to the nth degree. Yet I find his fevered visuals more genuinely arresting than the safe noodlings of most of today’s mainstream cinema. Man on Fire and Déja Vu reheat their genre leftovers into something spicy, if not nourishing, while Domino, the cinematic equivalent of hophead graffiti, wraps its sleazy characters in a visual design apparently inspired by the glowing interior of a peepshow booth.

So it’s with a chagrin that I report that The Taking of Pelham 123 is utterly square. The violence isn’t reveled in, the color scheme isn’t garish, the story has a florid villain played by scenery-masticating Travolta, and Denzel Washington has never seemed more passive and drab. In Scott’s DVD commentaries, he insists that art-school training led him to approach cinema with a painterly eye. But this project has the feel of a commissioned magazine illustration, not the delirious wall-size outrage that he could make if given his head.

I’ve respected Michael Mann since I saw Thief on its initial run. Heat seems to me on the whole his best work, though I admire many qualities of Manhunter, The Last of the Mohicans, The Insider, and Collateral. Ali and Miami Vice seem to me lesser achievements, and with Public Enemies he has gone somewhere I can’t follow.

I found it a surprisingly flat exercise, skimming over familiar territory–the charming bandit vs. the square-jawed cop, the struggle of the freebooter vs. the mob, the cynical politics of law enforcement vs. the authentic impulses of the outlaw. The plot is unusually straightforward for Mann, and the last shot, which ought to be a corker, is wasted. Too many scenes are nakedly expository, relying on fussy period detail to carry them. At the same time, more basic exposition seemed to me botched at the outset. In the opening scene, shouldn’t we get a clearer sense of what Dillinger’s sidekicks look and act like? A classically constructed film would dwell on them, characterize them, give them bits of behavior that develop in the course of the film. Mann treats them as part of the scenery setting off his handsome hero. Later, when one of Dillinger’s hired pistoleros goes kill-crazy, shouldn’t we have been set up to see him as a possible risk?

Typically Mann romanticizes, even sentimentalizes, his hard cases in that tough-guy way we know from fiction. But I couldn’t discern any vivid attitude toward his parallel protagonists Dillinger and Purvis. After Heat, where crook and cop both show a willingness to abandon women who want them, it’s probably significant that Dillinger is characterized by his fidelity to Billie. Yet while she’s in jail he’s back to an insouciant night on the town with his familiar floozies. In all, I can’t figure out why Mann made this movie about these people, or why we should care.

Collateral was already veering toward a certain obviousness of construction, when Vincent talks initially about how in impersonal L. A. a dead guy can ride the subway without anyone noticing. In Public Enemies the final line returns to the film’s most underscored motif in a distressingly on-the-nose way. Similarly, one thing I admire about Heat is that it acts as if no other gangster movie has ever been made. Its scenes offer plenty of opportunities for cute citations of old crime movies, especially when Vincent (a different Vincent) catches his wife’s lover watching TV. Instead, Mann treats the material as cut off from cinema, and this saves him from the coyness of so much genre work today.

Is he then a realist? His interviews and DVD commentaries indicate that he thinks of himself this way. Yet he strikes me instead as a genre purist. Each film is sui generis because it aims to recover the authentic dramatic core of the policier, the social comment film, or the wilderness adventure. But in Public Enemies, Dillinger’s visit to the movie house to watch Manhattan Melodrama (1934), even though the event is historically accurate, hits the parallel chords hard. Dillinger, who’s about to be cut down in a few moments, smiles in fascination when Gable says: “Die the way you lived–all of a sudden.” In such scenes, Mann seems to me to have retreated into being a more ordinary filmmaker. The worst thing I can say about Public Enemies is that it risks becoming academic.

Mann’s claims to realism are partly his efforts to deny being a self-conscious stylist. For many of his admirers, me included, his pictorial sense is a large part of what makes his work distinctive. There’s plenty of controversy about the look of Public Enemies, and I have to come down on the side of the nay-sayers. I saw it twice, once in 2K digital projection in a superb multiplex in Europe. My second viewing was on 35mm, in a reliable Madison, Wisconsin venue. The digital version too often teemed with artifacts, blown-out bright areas, and disconcerting shifts in tonal values within scenes. The next two images are successive shots in the HD trailer, and I haven’t adjusted them. The disparities between them reflect the sort of mismatches that struck me in the digital screening.

On film, the faces lost the edge enhancement and the mushy textures I saw in the digital version, and the tommygun fire was less tinged with yellow, pink, and orange. On the whole, I thought that the images benefited from the mercies of emulsion.

The chance to take high-definition video all the way, especially in low-light situations, seems to have invigorated Mann creatively, but it may have distracted him from basic craft. Investing wholly in a new look, he belabors even the simplest action through staccato cutting; getting people in and out of cars should not take such effort. Action scenes occasionally succumb to the jittery camera. I consider the climactic bank robbery in Heat somewhat awkwardly staged (though the dazzling sound work there compensates somewhat), and similar short-cuts can be found in the Wisconsin shootout here.

If you find my tone tentative, you’re right. I didn’t care for The Insider on first viewing; it took me a second visit to grasp what I now take as its virtues. That’s why I saw Public Enemies twice. I expect as well that Mann’s eloquent defenders, such as Matt Zoller Seitz, who has done a passionate series of shorts on Mann, will find fault with my evaluation. For the film’s admirers, what I find sketchily indicated they could see as daringly elliptical; what I see as inconsistent they might consider calculatedly ambiguous. The incompatibilities of color and light could be part of Mann’s experimentation too. I see his oeuvre as largely updating cinematic classicism, while others tend to see it as a daring leap beyond it. Maybe I’ll come around eventually. For now, I have to consider Public Enemies the biggest disappointment of my fifty days.

A welcome basterdization

It’s a measure of the changes wrought by the Internets that Inglourious Basterds has in about a month amassed a daunting volume of serious commentary. Without benefit of DVD (let’s be charitable and assume no BitTorrenting), dozens of online writers have dug deep into this movie. As if to demonstrate the virtues of crowdsourcing, this flurry of critical discussion has shown that most professional movie reviewers have tired ideas, know little about film history, and are constrained by the physical format and looming deadlines of print publication. At this point, I’m very glad I’m not writing a book on Tarantino; the sort of secondary sources that normally take years to accrete have piled up in a few weeks, and the pile can only grow bigger, faster.

So what is there left for me to say? A little, though I can’t be sure every point isn’t made somewhere else. In any case, surely you’ve seen it, so I don’t have to warn you about spoilers, do I?

Since I thought Death Proof offered merely proof of the director’s creative death, I went to Inglourious Basterds with low expectations. I came out thinking that it was the most audacious and ambitious American movie I saw in my fifty days of summer viewing.

To deal with the current controversy immediately: I didn’t think its counter-history was intrinsically offensive or immoral, since I remembered those what-if-Germany-had-won counterfactuals in Deighton’s novel SS-GB and Brownlow’s film It Happened Here (1966). Did those express defeatism or an inability to counter the Nazi threat? So why not have a band of vindictive Jews seeking to match the Nazis in ruthlessness (except that their targets, so far as we see, are only soldiers and collaborationists)? We call it fiction.

You can quarrel about whether a revenge plot should carry some signals of the cost to the avenger, but I’m sufficiently convinced that tit-for-tat is embedded in human nature and will always be perceived, however recklessly, as virtuous. In any case, the movie’s emblem of revenge, the powerful image of Shosanna laughing mockingly as she goes up in flames along with the audience, carries the strategic ambiguity of a lot of cunning popular art. It’s at once a glorying in payback, a Jeanne d’Arc martyrdom, and a reminder of the fate of Jews elsewhere at that moment. It doesn’t permit a single easy reading.

Granted, there are some low-jinks, like the misspelled title and heroine’s name; are these jokes on Tarantino’s notorious spelling malfunctions? Yet the movie seemed to me Tarantino’s most mature (to use a term of praise that he hates) since Jackie Brown. I say that not because his other work is juvenile, which it’s not (except for Death Proof). I call Inglourious Basterds mature because it exploits his strengths in fresh but recognizable ways.

First, strengths of structure. Tarantino’s conception of storytelling owes at least as much to popular literature, particularly policiers, as it does to current conventions of screenwriting.

Take his penchant for repeating scenes from different viewpoints. In Elmore Leonard’s novel Get Shorty, Chapter 2 ends with Harry, seeing Chili at his desk, exclaiming, “Jesus Christ!” Chapter 3 consists of the first stretch of their conversation. Chapter 4 starts with Karen approaching Harry’s office and hearing him say, “Jesus Christ!” This overlapping-scene strategy, sketched in Reservoir Dogs, gets elaborated in Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown.

Likewise, thrillers and crime novels commonly play on showing how distant lines of action unexpectedly intersect. In Peter Abrahams’ Hard Rain the agent who becomes the hero tells the story of two coal miners, Bazak and Vaclav, who meet after tunneling from two ends of the field. Needless to say, Hard Rain’s own plot enacts the same pattern. Charles Willeford’s chance-driven, parallel-action novel Sideswipe could be a model for the structure of Pulp Fiction. So it should be no surprise that Inglourious Basterds, labeling its long sequences “chapters,” should rely on the stepwise convergence of Shosanna’s plotline and the Basterds’ guerrilla operations, with the UK Operation Kino serving as the first sign of a merger.

So the film is built on large-scale alternation of the principal forces: Shosanna (Chapter 1), the Basterds (2), Shosanna again (3), the Basterds again (4), and finally the two strands knotting at the screening of National Pride (5). Landa also knits the two strands together, of course, starting when he investigates the tavern shootout at the end of (4). In Chapter 5 the alternation gets carried by classic crosscutting. We shift to and fro among Shosanna’s plot, the capture of Raine and Utivich, the conflagration in the auditorium, and the deal struck between Landa and the US command. Yet right to the end both Shosanna and the Basterds have no awareness of each other’s plan: only we grasp the double dose of Jewish vengeance. More than in most films, but typical for Tarantino, we’re aware of the plot’s abstract architecture.

Then there are strengths of texture—the moment-by-moment unfolding of the action. Again pulp fiction offers some models.

In Get Shorty, Leonard develops the scene I mentioned above in an extraordinary way. Chili, Harry, and Karen talk through the night about Chili’s purpose and about the ways of the movie industry. Their conversation runs for a remarkable seven chapters and sixty pages, interrupted only by a brief flashback. When I met Leonard at a book-signing event, I asked him why he took up a fifth of the novel with a single scene. He said that he hadn’t realized it consumed so much space, because it was “fun to write.”

Tarantino can lay bare his chapter-block architecture because his scenes are devoted to this sort of prolongation. You may remember the bursts of violence, but what he fashions most lovingly is buildup. Here the spirit of Leone hovers over our director. In each entry of the Dollars trilogy, you can see the rituals of the Western getting more and more stretched out, filled with microscopic gestures and eye-flicks. Eastwood’s lips stick slightly together and must peel apart when he speaks: This becomes a major event. I’m a primary-document witness to the fact that 1969 cinephiles were stunned by the long opening scene of Once Upon a Time in the West, which after painstakingly establishing the tics of several characters ends by eliminating them. Later, John Woo gained fame by dwelling on Homeric preparations for combat and endlessly extended bouts of gunplay. From these masters Tarantino evidently learned the power of the slow crescendo and the sustained aria.

Leone and Woo’s amped-up passages rely chiefly on imagery and music. Tarantino is no slouch in either department, but he relies, like his beloved pulp writers, on talk. As everyone has noticed, the conversations in Basterds go on a very long time. In an era when scenes are supposed to run two to three minutes on average, Tarantino has only a couple this brief. The introduction at LaPadite’s farm runs over eighteen minutes, by my count, and the more complicated Chapter 2, with intercut flashbacks and flash-forwards, runs about the same length. Thereafter scenes last anywhere between four and twenty-four minutes, and Chapter 5’s crosscut climax consumes a stunning thirty-seven minutes. All but the last depend completely on dialogue. Leonard would probably consider them to have been fun to write.

Talk in Tarantino comes in two main varieties: banter and intimidation. At the coffee shop the Reservoir Dogs squabble and soliloquize; later exchanges will be conducted at gunpoint. En route to the preppies’ apartment, Jules and Vincent chat casually; when they arrive, the talk turns threatening. If Death Proof lets banter dominate, Inglourious Basterds goes to the other extreme. Here talk is a struggle between the powerful and the powerless.

As Jim Emerson points out, nearly every scene is an interrogation. This entails that someone in authority (Landa, Aldo, Hitler, the Germans who question Archie’s accent in the tavern, Zoller) is trying to pry information out of someone else. Intimidation through interrogation gives every scene an urgent shape. Now Tarantino’s digressions (three daughters, rats and squirrels, a card game, the correct pronunciation of Italian) don’t read as self-indulgence, but rather as feints in a confidence game. Here Tarantino’s tendency to write endless scenes, something he confesses in his recent Creative Screenwriting interview on the film, is fully harnessed to more classic, albeit unusually extended, scene structure.

To keep us focused on the lines and the actors delivering them, Tarantino has adopted a classical approach to style. He shoots with a single camera, so every composition is calculated. “I’m not Mr. Coverage,” he remarked in 1994, “. . . . I shoot one thing specifically and that’s all I get.” He foreswears handheld grab-and-go. In Basterds he locks his camera down, or puts it on a dolly or crane. Cinematographer Robert Richardson says that there is only one Steadicam shot in the film.

We don’t usually call Tarantino tactful, but his technique can be surprisingly discreet. He has the confidence to let key dialogue play offscreen: in the café when Landa arrives at Goebbels’ lunch, we stay fastened on Shosanna, a good old Hitchcockian ploy that ratchets up the tenson. Although Tarantino cuts rapidly throughout each chapter (on average every 5.6 seconds), he repeats setups quite a bit. This permits a simple change of angle or scale to mark a beat or shift the drama to a new level.

He can bury details on the fringes of the shot, as when the cut to the tight close-up of LaPadite shows him tossing his match into an ashtray sitting beside Landa’s cap, which bears the insignia of a skull and crossbones. It’s out of focus and on the edge of the screen, but the glimpse of it increases our fear that LaPadite is indeed harboring a Jewish family. As in Jackie Brown, another film that extends its scenes through detailing of performance, lighting, and setting, there seems no doubt that Tarantino, for all his PoMo reputation, appreciates some traditional Hollywood virtues.

He can inflect them, however. Richardson finds that Tarantino has an unusual approach to the anamorphic format.

I naturally move [the framing of characters] to one side or the other, especially when shooting anamorphic, whereas Quentin enjoys dead-center framing. For singles in particular, we’re just cutting dead-center framing from one side to the other, with the actors looking just past the barrel of the lens.

I noticed this tendency most in the reverse angles. Tarantino’s two-shots tend to be simple and symmetrical, shooting the characters in profile, as in the image surmounting this entry. But in over-the-shoulder shots, about half the frame is unoccupied—as if Tarantino were compensating, like his 1970s mentors, for an eventual TV pan-and-scan version of the scene.

Or take the cliché of arcing the camera around a group of chatting people, picking up one after the other. Tarantino didn’t invent this, but the opening scene of Reservoir Dogs probably helped popularize it. In Chapter 5 he uses the technique in the lobby of the Le Gamaar cinema, only to break its momentum by having the camera trail Landa when he breaks out of the circle and retreats, in a paroxysm of giggles, after Bridget says she broke her leg while mountain climbing.

There are many other intriguing touches, like the mixed typography of the opening credits, all of which seem to use fonts derived from 1970s paperback novels. Or the reference to The Saint in New York, perhaps less important for its plot parallels than for the fact that author Leslie Charteris’ later Saint novel, Prelude to War (1938), was banned in Germany and Italy for its attacks on fascism (even warning about the camps). So is reading a Saint novel a covert act of defiance on Shosanna’s part? Later, she applies make-up in fierce strokes, like an American Indian, reminding us that Raine’s Basterds model their tactics on the Apache.

There are many other intriguing touches, like the mixed typography of the opening credits, all of which seem to use fonts derived from 1970s paperback novels. Or the reference to The Saint in New York, perhaps less important for its plot parallels than for the fact that author Leslie Charteris’ later Saint novel, Prelude to War (1938), was banned in Germany and Italy for its attacks on fascism (even warning about the camps). So is reading a Saint novel a covert act of defiance on Shosanna’s part? Later, she applies make-up in fierce strokes, like an American Indian, reminding us that Raine’s Basterds model their tactics on the Apache.

Perhaps most striking is the dairy motif, from the glass of milk in Chapter 1 to Landa’s ordering a glass for Shosanna in Chapter 3. Is this a hint that he suspects her of being the girl who fled the massacre? Or is it a test he offers to any French national he meets? In the restaurant scene, the extreme close-ups of the crème fraiche may underscore the possibility that Landa is looking for signs that she won’t eat dairy products not prepared according to Orthodox dietary rules. Few filmmakers today would trust audiences to imagine this possibility on their own; instead we’d get an explanation to an underling. (“So here’s a quick way to find out if we have a Jew ….”)

Another nest of details involves the film-within-the-film, Nation’s Pride. Many online critics have noticed that it provides the sort of film that Basterds refuses to be: We never see our squad in the sort of Merrill’s Marauders skirmishes we probably expected going in. What I find intriguing about the movie, purportedly directed by Eli Roth, is that despite some anachronisms it exemplifies the sort of confrontational cinema we find in the silent Soviet pictures. Surprisingly, this was a tradition that Goebbels admired. Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, he claimed, “was so well made that it could make a Bolshevist out of anyone without a firm philosophical footing.” So in Nation’s Pride Roth and Tarantino have provided a Nazified homage to Eisenstein: a baby carriage rolls away from a mother, a soldier suffers an assault to the eye reminiscent of the wounding of the schoolteacher on the Odessa Steps, and even Soviet-style axial cut-ins are used for kinetic impact.

This pastiche of agitprop culminates in the sort of to-camera address we find in Dovzhenko. Zoller shouts, “Who wants to send a message to Germany?” But this is followed by Shosanna’s spliced-in close-up addressing the audience in her theatre.

She makes her own confrontational cinema.

Several years ago the film theorist Noël Carroll speculated that the Movie Brats of the 1970s sought to create a shared culture of media savvy that would replace the traditional culture based on religion, classical mythology, and official history. For the baby boomers, knowledge of the Christian Bible and iconography of American history would be replaced by deep familiarity with movies, pop music, and TV. This secular sacred would bind the audience in a new set of traditions. On this path, Scorsese, Spielberg, and Lucas didn’t go as far as Tarantino has. In his films every situation or character name or line of dialogue feels like a citation, a link in a web of pop-culture associations. (Aldo Raine = Aldo Ray = Bruce Willis, whom Tarantino once compared to Aldo Ray.) The only other filmmaker I know who has achieved this supersaturated cross-referencing is Godard, another exponent of the vivid-moments model (though he uses it to create a more fragmentary whole). Tarantino is the most visible evidence of what Carroll called “The future of allusion.”

But it’s too limiting to see Tarantino’s films as merely anthologies of references. I think he wants more.

Many viewers seem to assume that Tarantino’s film is somewhat cold. The Basterds are grotesques, parodies of men on a mission; Shosanna, though in a sympathetic position, must maintain a frosty demeanor. Even revenge, so central to films that Tarantino admires, is served frigid here, a purely formal postulate, like the urge for vengeance animating classic kung-fu films.

There is cinema that asks you to empathize with its characters. Then there is cinema that aims to thrill you with a cascade of vivid moments. There is How Green Was My Valley (1941) and Citizen Kane (1941). I think that Tarantino’s films mostly tilt to the vivid-moment pole, seeking to win us through their immediate verve, the way film noir and the musical and the action movie often do. The young man arrested by great bits from blaxploitation and biker movies sees cinema not as merely piling up cinephiliac references—though that’s surely part of it—but as a flow of tingle-inducing gestures, turns of phrase, shot changes, musical entrances. There can be pure pleasure in having time to see how actors move, or savor their lines, or simply fill up physical space by being centered in the anamorphic frame. Our fascination with Landa comes, I suspect, from the spectacle of a man who is utterly enjoying himself every second.

We might be tempted to claim that this effort to create what Jim Emerson calls “movie-movie moments” actually breaks the film’s overall unity. But Tarantino keeps nearly everything in check by the architectural clarity of his plot. The carving of the swastika on Landa’s brow sets you squirming, but it reveals itself as the culmination of a process we have seen piecemeal up to now. It’s the last in a string of firecracker bursts that have kept the film humming along.

So I’m not convinced that Inglourious Basterds lacks emotion. The emotions Tarantino aims for will arise not from character “identification” but from the overall structure and texture of the work. We are to be stirred, enraptured, astonished by a procession of splendors big and small. It’s the tradition (again) of Eisenstein, particularly in the Ivan films, but also of Leone and, in another register, Greenaway. Formal virtuosity isn’t necessarily soulless; it can yield aesthetic rapture.

The most sophisticated analyses and interpretations I’ve found online are led off by the indefatigable Jim Emerson (start here to track his many entries on the subject), along with his knowedgeable readers, who furnished a book’s worth of commentary and critique. Jim provides links to many other writers’ work (here, for example), not all of which I’ve been able to absorb. For exhaustive, not to say exhausting, coverage of things Tarantino, visit The Archives.

On Tarantino’s time-shuffling and its relation to crime fiction, see my Way Hollywood Tells It, 90-91. In Chapter 7 of Film Art Kristin and I provide an analysis of the replayed scene in Jackie Brown. Tarantino’s comments on writing the Basterds script are in Jeff Goldsmith’s article, “Glorious,” in Creative Screenwriting 16, 4 (July/ August 2009), 20-29. His comments on coverage come from Gavin Smith, “When You Know You’re in Good Hands,” in Quentin Tarantino Interviews, ed. Gerry Peary (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1998), 102. In the same interview he has illuminating comments on the role of the axis of action. Robert Richardson discusses filming Basterds in Benjamin Bergery, “A Nazi’s Worst Nightmare,” American Cinematographer 90, 9 (September 2009); the quotation here is from p. 47. This feature is available online here.

Goebbels’ remark on Battleship Potemkin is quoted in Klaus Kreimeier, The UFA Story: A History of Germany’s Greatest Film Company, trans. Robert and Rita Kimber (New York: Hill and Wang, 1996), 207. For background on Goebbels’ agenda for German cinema, summed up by Lt. Archie Hicox, see Eric Rentschler, The Ministry of Illusion: Nazi Cinema and Its Afterlife (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996). I talk about axial cutting in Eisenstein and other Soviet directors at various points in The Cinema of Eisenstein.

Noël Carroll’s comments about popular entertainment as a secular alternative to shared religious culture are in his essay, “The Future of Allusion: Hollywood in the Seventies (and Beyond),” in Interpreting the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 244, 261-63. On the idea of an emotionally arousing cinema that doesn’t rely on attachment to character psychology, see my Cinema of Eisenstein.

PS 20 Sept 2009: Curt Purcell, at The Groovy Age of Horror, finds a similar plot architecture emerging in the comic-book series Blackest Night.

Title wave

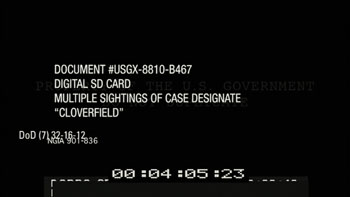

The very first drafts of the outline always had Cloverfield on them. . . . Cloverfield was what I always wanted to call the movie. . . . It’s a terrible title . . . if you’re trying to sell something, who the hell’s gonna go see that?. . . But it’s cool. There’s a reason. I could state the reason, but it’s very clear it is meant to be obtuse. I believe that the film answers why it is called Cloverfield, I believe that it’s in the film, I believe that you can make that argument. It says exactly what I want it to say. But it’s very clear that we don’t want to explain it.

Screenwriter Drew Goddard, at Creative Screenwriting podcast

DB here:

Don’t think about a movie title too long. Even a familiar one can turn strange before your eyes.

This was brought home to me long ago when I showed Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan in a course. Before the film started, a student asked me, “Who is it?” I didn’t understand. “I mean, who is her fan?” It never occurred to me to take the title this way, but actually in the movie Lady W does attract a big fan.

Titles can be explicit, but they’re often metaphorical, associative, and oblique. Sometimes they’re downright obscure. But as Drew Goddard says, they can be cool.

Don’t Worry, We’ll Think of a Title (1966)

The least provocative titles are based on the protagonist’s name: Brubaker, Anthony Adverse, Erin Brockovich, Norma Rae, Speed Racer. One step removed is the title that describes the protagonist’s job or role: Gladiator, Hitman, The Cable Guy, Bob le flambeur, perhaps also The Godfather. Then there are the titles, like The Last Action Hero or Prince of Players or Little Caesar, that characterize the protagonist more figuratively.

If the movie has a pair of protagonists, the title can reflect that, as in David and Bathsheba, Pete’n’Tilly, and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. When the title elevates a secondary figure, as in Melvin and Howard or Harry and Tonto, it has the effect of making us consider the relationship between the two as central to the action. When there are several main characters, we can get a title characterizing the group, not just Bob & Carol & Ted & Alice but The Professionals and The Breakfast Club.

Things get a little more curious when the title focuses on a character other than the protagonist(s). Rebecca identifies a dead character, but her aura haunts the (unnamed) heroine. Both versions of The Man Who Knew Too Much refer, at least literally, to a minor figure. Why is The Wizard of Oz not called Dorothy Goes to Oz? Why does Mizoguchi’s great Sansho the Bailiff take its title from the name of the villain? It’s not as if Mizoguchi was trying to do an Ian Fleming (Dr. No, Goldfinger).

Perhaps Wizard and Sansho bear their titles because they’re adapted from literary sources that had those titles. But that just pushes the problem back a step: Why do the originals have these titles? And in asking why, I’m not asking for information about what went on in an author’s mind or a story conference. The why question here is about purpose and function. What does the title do in relation to the film’s plot or theme?

For instance, you can argue that the title of The Wizard of Oz works to highlight the seductive world of Oz, so different from Kansas, with the Wizard himself being a figure with one foot in fantasy and one in reality (since the Wizard is actually a prairie mountebank). Similarly, I’m inclined to say that Sansho the Bailiff’s title reminds us of the socially sanctioned cruelty at its center. Zushio and Anju, the fugitive brother and sister, may each escape in a different way, but Sansho’s world remains; it is our world.

Some titles are simply place names, like Casablanca, Macao, Philadelphia, or New York, New York. Others specify dates: 1860, 1900, 1941, 1984. In both strategies, the title often evokes symbolic associations or parallels with the here and now.

The title can refer to the core situation, as with Back to School or Being John Malkovich, or to a key scene, as in Sophie’s Choice and Gunfight at the OK Corral. This can get abstract and metaphorical. Housekeeping features a very offbeat approach to housekeeping. The Birth of a Nation characterizes America reborn after the Civil War. Being There describes more or less all that the cipher-like hero does. The title can even predict the action, as in The Great Escape, A Man Escaped, and Killing of a Chinese Bookie. In these instances we have anomalous suspense: Why and how will an announced action be carried out?

Reaching for the Moon (1917/ 1930/ 1933)

More rarely, the title can refer to the film’s central formal device. Through Different Eyes and Vantage Point announce that they will play with subjective point of view. The Blair Witch Project justifies its title by posing as a dossier of found student footage. The Prestige warns us that a magic trick’s surprise payoff might well be matched by one at the end of this movie. Kristin and I have long assumed that the title of Tati’s Play Time refers not only to the anarchic relaxation unleashed in the Royal Garden restaurant but also to the movie’s own perceptual strategy of making us see amusement in banal incidents.

Hitchcock, the tireless formalist, provided titles that give away his game. Rear Window announces a stationary viewpoint and a limited field of action. More fancifully, you could take Rope as announcing the film’s sinuous long takes. Family Plot is nicely equivocal, referring at once to a communal grave, a conspiracy among kin, and of course the movie’s own mysterious plot of knotty kin relations.

Then there are the generic characterizing titles, usually single-word titles like Notorious or Spellbound or Pushover or Identity or Slacker or Speed or even, probably most generic of all, Conflict (borne by at least five films, from 1916 to 1955). Here again, though, we can find puzzles.

We know why Homicidal is called Homicidal, but what purpose is served by calling a movie Psycho? Again, the source book provides the title, but Robert Bloch’s novel is narrated in the first person and the title gives us a big clue about the sort of mind we’re in. Hitchcock’s film presents the story more objectively, and it begins with Marion Crane’s theft. Those critics who see the film as blurring the boundaries between sanity and insanity would say that Marion, who impulsively commits a crime, and Norman are points on a continuum. People we take to be normal have irrational impulses, a point reinforced by Norman’s line, “We all go a little mad sometimes. Haven’t you?” After their conversation about private traps, Marion seems to recognize herself in his question.

Same old song (1997)

Many titles are citations or quotations, and they usually highlight a thematic element. Both Yankee Doodle Dandy and Born on the Fourth of July are drawn from the same song: both offer portraits of patriotism, but in very different keys. Pennies from Heaven is highly, perhaps heavily, ironic, something you can’t say about Meet Me in St. Louis.

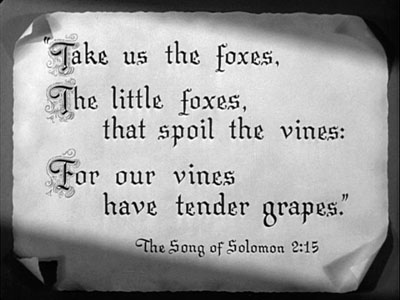

Not all citations are as transparent as these. The Little Foxes explains its title in a prologue, seen above. The Bible verse is then linked to the story we’ll see.

We’re ready to understand the family as creating a milieu that could easily corrupt the tender vine, Xan.

A catch phrase can work too, such as The Sweet Hereafter or It Takes a Thief or It’s a Wonderful Life. You Can’t Take It With You emphasizes pursuing fun rather than riches. Phffft suggests that a couple has split, but how would you explain that outside the U. S.? (The French title is, perhaps surprisingly, Phffft.)

Some catchphrase titles suggest the sort of multiple meanings we saw in Family Plot and Play Time. All That Jazz packs a lot into three words: most basically, a flurry of trivial stuff (pushing our hero into overdrive), but also music and the heights of emotion (being jazzed). You Only Live Once at first suggests seizing the moment, but by the end of the film you begin to think it implies: “Who could bear to live twice?” I especially like The Best Years of Our Lives, which also changes its significance across the film. The bulk of the movie asks: The returning servicemen have given their prime years for us, but how do we reward them? By the end of the movie, the title seems to be suggesting that their best years, of healing and self-understanding and integration into families, lie ahead of them.

I’ve known students, especially from outside the U. S., to have trouble with His Girl Friday. It’s a two-tiered reference. First is Robinson Crusoe’s “man Friday,” his aboriginal servant. But in American slang, a girl Friday is the boss’s closest female assistant, an all-around tough worker and troubleshooter. That’s what Hildy is to Walter Burns, until she decides to marry Bruce and move to Albany. She reverts to her girl Friday role in the course of the film, as the title has predicted she would.

We don’t always know when a quotation is at work. I have always found Some Came Running obscure. The phrase isn’t used in the film, or in the text of the James Jones source novel. But the novel’s epigraph takes a passage from Mark 10: 17:

And when he was gone forth into the way, there came one running, and kneeled to him, and asked him, Good Master, what shall I do that I may inherit eternal life?

This is the passage where Jesus asks the rich man to give all that he has to the poor, apparently as unlikely an event then as now. The problem is that in the Biblical passage, only one came running. The reader has to imagine several characters in the novel as “running” to ask how they will get into heaven. But the citation seems to me a mismatch, since the characters of novel and film aren’t all rich. In any case, without the epigraph tacked to the movie, its significance gets lost. This doesn’t stop me from liking the title, though.

One of my favorite instances of the obscure catchphrase-title is Ozu’s I Was Born, But . . . To decipher it you have to know that during the Depression, Japanese college graduates often couldn’t find work, and the sentence “I graduated, but . . . ,” trailing off, suggesting “. . . I’m unemployed,” was a topical one at the time. Ozu in fact made a film with that title. But then he decided to have fun with it, making a college comedy called I Flunked, But . . . Then came an even sillier extension: When he makes a film about boys, it becomes I Was Born, But . . . [I still have problems…]. Our parallel, I suppose, is the move from Honey, I Shrunk the Kids to Honey, I Blew Up the Kid.

Which reminds me: Titles have a strange habit of speaking for the character. We have I Was a Teenage Werewolf, I Dood It, I Love Melvin, Me and the Colonel, My Favorite Brunette, My Cousin Vinny, Blackmail Is My Life, and so on. This convention points up the difference between literature and film. A book with one of these titles would lead us to expect first-person narration, and it would be strange if it didn’t. A movie with such a title might provide voice-over commentary from the protagonist, as How Green Was My Valley and I Walked with a Zombie do, but more likely it won’t.

For Your Eyes Only (1981)

Many titles seem enigmatic when you first hear them. They create curiosity and build up an urge to check out the film. In most cases, the mystery gets cleared up in the course of the movie. Erik Gunneson’s Milk Punch does this through a bit of action, but more commonly the title is clarified in a line of dialogue or a motif. You have to wait for the very end of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? or Rio Bravo to get a reference to the title. A good embedded title shifts its meanings, as Best Years does. One scene of Silence of the Lambs explains the title’s relevance to Clarice’s character and shows what drives her to pursue Buffalo Bill. By the end of the film it points toward a moment when her inner pain will start to fade. And the title may reverberate beyond that moment, pointing to larger themes of injured innocence in a world of slaughter.

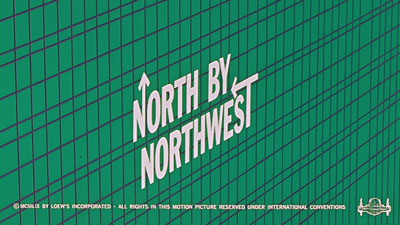

Sometimes the title is more oblique. Take North by Northwest. Many critics believe that it refers to Hamlet’s confession that “I am but mad North-northwest: When the wind is southerly, I know a hawk from a handsaw.” Roger Thornhill, caught off balance by the espionage game he’s plunged into, could be said to have lost his bearings. But I’ve always thought that the compass-point title logo and the cross-hatched latitude/ longitude array that launch the movie prepare us for travel, in a roughly westerly, then northwesterly direction (New York-Chicago-South Dakota). And when Roger is sent from Chicago to Rapid City, he travels by airliner: He flies north, by Northwest. A Hitchcock joke?

We occasionally encounter a title that isn’t explained in the course of the action, so we are invited to ponder its implications. 8 ½ is a famous example; insiders know Fellini treated it as an opus number (seven features + two shorts + this new feature = 8 ½). American Graffiti can refer to the transitory events of the single night the film shows—the kids have scrawled their dramas on the town in one long summer blast. But I think you can also read the title as referring to the pop tunes that engulf and comment on the action. Americans write their graffiti on the airwaves.

In recent times Hong Kong films have tried to make their English-language titles more comprehensible, but in the golden years there were some delirious ones. We had Banana Cop, Wheels on Meals, Why Wild Girls, Gun Is Law, Tiger on Beat, Devil Fetus, Burning Sensation, Boys?, Kung-Fu vs. Acrobatic, Evil Black Magic, Ghost Punting, Takes Two to Mingle, Vampire’s Breakfast. . . Even Chungking Express and Ashes of Time aren’t straightforward. A real problem in studying Hong Kong films seriously is to explain to people that a movie called Police Story or Naked Killer can be pretty interesting. And if the titles don’t perturb them, the subtitles will.

But most of the Hong Kong titles are inadvertently puzzling, sort of accidental surrealism. Of course Surrealist filmmakers have given us many willfully meaningless titles, such as Emak Bakia and The Andalusian Dog. Arguably Brazil and even A Hard Day’s Night are in this vein (although I think that both of these can be explained in roundabout ways).

Today’s American films seem drawn to recherché titles. I heard Jonathan Caouette remark that he chose the title Tarnation for reasons he couldn’t specify; it just seemed to fit. One catchphrase, “the elephant in the room,” has founded two movies, but in such an abbreviated form—Elephant—that you might not recognize the link. I never thought I’d find synecdoche on a movie credit, since few Americans know how to pronounce it, let alone know what it means. But trust Charlie Kaufman to give it a try. (He also inadvertently stole a pun I’ve been using in film theory courses since the seventies.) But at least I think I get the title’s point, given the protagonist’s obsession to build a miniature city. Other titles are flat-out baffling.

Take Reservoir Dogs. Tarantino says “it’s more of a mood title, it just sums up the movie, don’t ask me why.” (1) I like the title. I just don’t understand why it works so well. Do certain dogs guard reservoirs, as some guard junkyards? Are these guys as vicious as dogs, as dirty as dogs, or doggy in the sense of losers, or what? In other words, why does it seem more fitting than, say, Sump-Pump Ferrets?

Despite the logo showing faces spilling out of a blossom, Magnolia doesn’t explain its title unless you dig around outside the film. During the rain of frogs, the traffic collisions take place on Magnolia Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley. So in a way, Magnolia is one point of convergence for several of the story lines that crisscross the plot. But that’s pretty thin motivation.

What about Syriana? Before I went to the film, I had heard that the title referred to an imaginary, prototypical Middle Eastern territory used in Pentagon war games and computer simulations. But Stephen Gaghan, in another Creative Screenwriting podcast, supplies details:

It was a real term. I heard it for real in a very conservative think-tank, where they said, “We’re going to redraw the map in the Middle East, we’re going to make a new country out of Syria, Iraq, and Iran—the borders of ancient Persia, less Pakistan. We’re going to call it Syriana.” I’m like, “Excuse me? Would you repeat that?” So I shot it, I had William Hurt explaining it. But I didn’t think it helped at the end of the day. We’re not going to make a new country in the Middle East right now.

As he saw the collapse of America’s invasion of Iraq, Gaghan came to believe that explaining the title would date the movie.

I wanted to go for a title that couldn’t be pegged to right now. You notice there’s no reference to Iraq in the movie, there’s just the most passing reference to 9/11, which was an improv thing we did, and there’s no Israel. I wanted the more permanent sense of what it is inside of men, particularly men in the west, that makes them believe that they can remake any region to suit their own purposes. . . . I wanted it to be specific to the film, not to the time. So that if you think about the tone of the film, when you think about what happened in the movie, it would only be Syriana, and Syriana could not skid into some other reference point.