Archive for the 'Directors: Tarr' Category

Vancouver visions

Drizzle every day can’t dampen audiences’ enthusiasm.

DB again:

More dispatches from the Vancouver International Film Festival.

“Be pleased, then, you living one, in your delightfully warmed bed, before Lethe’s ice-cold wave will lick your escaping foot.” As a tram destination, Lethe makes a brief appearance in the Swedish film You, the Living, Roy Andersson’s latest comedy of trivial miseries. The line from Goethe is apt. After ninety minutes of drab apartments and Balthus-like figures, all bathed in sickly greenish light, you’re ready to stay in bed forever.

As in Songs from the Second Floor, Andersson gives us a loose network narrative, with barely characterized figures threading their way through urban locales. Long-shot, single-take scenes turn clinics and dining rooms into monumentally desolate spaces. Humans, either bulbous or emaciated, trudge through torrential rain and peer out from distant windows. The bodies may be distorted and careworn, but the spaces are even more so. We get a sort of dystopian Tati, in which gags, near-gags, and anti-gags are swallowed up in the cavities we call home and workplace. A carpet store stretches off into the distance, and a cloakroom seems like a basketball court.

In You, the Living, Andersson’s characters recount their dreams, and these open onto areas only a step beyond our world in their lumpish crowds and eerie vacancy. Judges at a trial are served beer as they condemn the accused. Spectators at an electrocution snack on popcorn from supersized buckets. How can I not like a filmmaker so committed to moving his actors around diagonal spaces, even if the frame is either sparse or uniformly packed, and though he does treat his people like sacks of coal? Don’t look for hope here, only a sardonic eye attracted by banality and pointlessness, images made all the bleaker by an occasional song.

I’m drawn to directors who create a powerful visual and auditory world more or less out of phase with reality as we usually see it (in life and in movies). Andersson is one such director; Jiang Wen is another, whose audacious The Sun Also Rises is one of my favorites of the festival so far. Not doing so well with Mainland Chinese audiences, according to the International Herald Tribune, it hasn’t warmed up a lot of Western critics either. Amazingly, it was declined for competition at Cannes.

It seems impossible to discuss The Sun Also Rises without using the word “magic,” as in magic realism, but I saw it as more of a fairy tale or fable. Set in the Cultural Revolution, it tells two stories in the first two sections. A young boy’s mother goes a little mad on a labor farm; in another village, a teacher is compromised by the passionate love of a nurse and an accusation of sexual misconduct. The two stories intersect in a third section, which leads to a jubilant, if disconcerting, final stretch.

At the center of each plot stands a vivacious, passionate woman who unleashes a cascade of unhappy events. Yet the tone of the film is cheerful, almost giddy, thanks not only to Joe Hisaishi’s buoyant score (he may now be the Nino Rota of Asian cinema) but to Jiang’s fresh, assured technique. The movie starts with tight close-ups—the fish-design shoes the mother wants, her feet and hands, her son’s hands at the abacus—edited at a cracking pace. Staccato movements in and out of the frame give the whole passage a visual snap that launches the movie. Characters lunge through the shots, running this way and that without catching breath, and Jiang’s camera follows them without pausing for the sort of stately scene-setting that audiences may expect. Likewise, the second story opens with hands at play and work, the teacher stroking his guitar strings and a bevy of woman kneading bread dough.

At the center of each plot stands a vivacious, passionate woman who unleashes a cascade of unhappy events. Yet the tone of the film is cheerful, almost giddy, thanks not only to Joe Hisaishi’s buoyant score (he may now be the Nino Rota of Asian cinema) but to Jiang’s fresh, assured technique. The movie starts with tight close-ups—the fish-design shoes the mother wants, her feet and hands, her son’s hands at the abacus—edited at a cracking pace. Staccato movements in and out of the frame give the whole passage a visual snap that launches the movie. Characters lunge through the shots, running this way and that without catching breath, and Jiang’s camera follows them without pausing for the sort of stately scene-setting that audiences may expect. Likewise, the second story opens with hands at play and work, the teacher stroking his guitar strings and a bevy of woman kneading bread dough.

The exuberance of the characters and the style contrasts with the usual presentation of this cruel era of PRC history. Jiang finds real pleasure in Cultural Revolution kitsch, and he links a snapshot of the missing father to an iconic image from The Red Detachment of Women. It’s another knot joining the two plot strands; in the second section, villagers watch a screening of that film. Jiang makes the event a real festivity, with couples courting, the teacher humming along with the tunes, and an old lady feeding fish in a pond. Jiang dares to suggest that the force-fed popular culture of Maoism, so scoffed at now, gave genuine enjoyment

The fairy-tale atmosphere is conjured up by little mysteries, such as a talking bird and the possibility of taking dictation on an abacus, and bigger ones about fatherhood, a stone hut in the forest, and a shadowy figure named Alyosha, whose identity is more or less revealed in the film’s final long sequence. Variety‘s Derek Elley found The Sun Also Rises both rushed and dawdling, but you could say that about 8 ½ too. Like Fellini’s film, Jiang’s shows a filmmaker at the top of his powers inviting us to savor the exhilarating attractions of imagination.

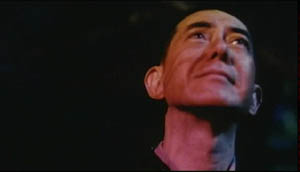

Another world, another vision. The camera frames a rope descending into black water and tilts slowly, really slowly, up to reveal the ship’s prow and the deck, swathed in darkness. Two silhouettes are visible, and one says, “Don’t follow me too soon.” Soon we’re following the transfer of a small suitcase, the disembarking of passengers making their way to a train. This nearly thirteen-minute shot (!) gives way to another long take, in which we see, in the distance, a murder on the quay.

Béla Tarr has called The Man from London a film noir, and he explained that to me by saying, “Not an American film noir. They were done by bad directors. More like the original French film noirs.” Indeed, the opening shot, with its mists and murky waterfront, suggests Quai des brumes. But here the plot action is slight, presented at a distance, and opaque in its motives; 10 % story, we might say, but 90 % atmosphere. The camera coasts across the waterfront town with the same grave deliberation we see in Damnation, Sátántangó, and Werckmeister Harmonies, swallowing up the Simenon situation in Tarr’s fluid way of seeing, a scanning of ever-shifting surfaces and vistas.

With fewer than thirty shots across about 133 minutes, The Man from London is another exercise in long-take virtuosity, but I thought I noticed some fresh departures. For one thing, there are few characters and relatively few locales, and situations are brought out with unusual explicitness (for Tarr). Instead, it seemed to me that Tarr was exploring new possibilities in one of his pet techniques, the over-the-shoulder long shot I mentioned in an earlier entry.

The opening shot, at first an apparently objective survey of the moored ship, turns out to be a view from the tower manned by Maloin. In shooting the wharf, the camera is forever oscillating, within a single shot, between what we can see outside, at a distance, from a high angle, and glimpses of Maloin at his post, his head or shoulder sliding into the foreground. Imagine Rear Window without the reverse shots of Jimmy Stewart watching.

In earlier films, Tarr tended to be quite clear when his foreground character was noticing something in the distance; his chief interest lay in suppressing the character’s reaction. What we get here can be seen as a refinement of the opening shot of Damnation, with its awesome landscape gradually reframed by Karrer looking out his window, or of passages of the doctor at his window in Sótántangó. Several of the tower scenes in The Man from London, are elaborations of that image scheme, but with more ambiguity. The camera, slipping from long-shot background and close-up foreground, coasts along without telling us whether Maloin has seen exactly what we’ve seen. The result is a suspenseful uncertainty not only about what’s happening in the noir plot but also about what Maloin knows.

There are many other points of interest in the new film, and after one viewing I can’t claim to have a grip on them. But I do think critics have overlooked its sheer visual beauty and Tarr’s efforts to turn his style toward a fluid pictorial suspense.

Altogether less flamboyant than any of these was Suo Masayuki’s I Just Didn’t Do It (Japan), which I’d been looking forward to since my February entry. It’s definitely a change of pace for a director known for comedies that satirize youth culture and middle-aged boredom. A young man is accused of groping a schoolgirl on a crowded traincar. The police advise him to confess and pay a fine, but he insists on his innocence. This decision drops him into a judicial mill that grinds slow and altogether too fine.

The script carpentry seems to me excellent. The presentation of each phase of the boy’s case could have been dry, but Suo makes each step hinge on a detail of fact or inference, so small questions keep popping up—including questions about whether the boy really might have done it. The finale, which recalls Kurosawa’s Ikiru in its methodical summing up of everything we have seen, becomes grueling, but in a salutary way. In Japan, the film is a trailblazing critique of the criminal justice system, where most people arrested confess in order to avoid the almost inevitable guilty verdict in a trial. Eliminating a jury, barring defense counsel’s discovery of prosecution evidence, and capriciously replacing one judge by another midway through a case, the system encourages cynical submission.

Suo avoids stylistic pyrotechnics. He plays down his signature mugshot framings (the publicity still above is an exception) and has recourse to handheld camerawork simply to distinguish the train scenes from the rest of the film. Still, his shooting displays a quiet agility. The high point is probably the testimony of the schoolgirl, her identity protected by screens set up around her. Suo finds a remarkable variety of camera setups here, each well-judged to impart a particular piece of information. (In its resourceful changes of viewpoint, the sequence reminded me of Mizoguchi’s courtroom scenes in Taki no Shiraito and Victory of Women.) The title suggests a strident social-problem film, but Suo’s calm plainness of handling yields a quality rare in the genre: tact.

Many more films to report on, including Johnnie To’s latest, but I must rush off to—what else?—another movie. I’ll try for a wrapup on Thursday, while I’m on that highway in the sky.

The critics line up: Bérénice Reynaud, Shelly Kraicer, Chuck Stephens, and Tony Rayns.

The sarcastic laments of Béla Tarr

Werckmeister Harmonies.

DB here:

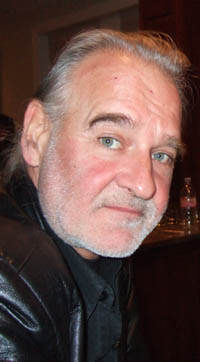

Last weekend, Facets MultiMedia in Chicago held a tribute to Béla Tarr. Milos Stehlik and his colleagues have been long-time champions of Tarr’s work, holding retrospectives and releasing nearly all his features on DVD (with Sátántangó soon to come). Tarr arrived on Saturday, but an emergency sent him back to Hungary sooner than he expected. So instead of discussing his work with a panel, he could only introduce the screening of Werckmeister Harmonies before running off to the airport.

The panel went ahead, with Jonathan Rosenbaum, Scott Foundas, and me chatting with Susan Doll of Facets. It wasn’t as pungent a session as it would have been with Tarr there, but I thought it was still pretty interesting. Jonathan, Scott, and Susan had thoughtful comments, and the questions from the audience were exceptionally good. The whole session was recorded for an online broadcast at some point, so you might want to watch out for that. And I have earlier blog entries on Sátántangó here and here.

In preparation for the panel I spent last week reconsidering Tarr’s work, so I offer a few notions about his films and how we might place them in the history of cinematic form and style. Some of these remarks build on things I said at the session.

Up close and personal

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

Some directors accommodate critics, accepting or at least tolerating writers’ efforts to probe the work. Not Tarr. Ask about his plots and characters, and he claims that he doesn’t tell stories. Point out what seem allegorical or symbolic touches, and he protests that he doesn’t make allegories and he hates symbols. Mention contemporary cinema, and the reply is abrupt: “For me, when I see something at the cinema it is always full of shit.” And if you tell him that his early films seem quite different from his more recent ones, he vehemently disagrees.

As Scott pointed out in our panel, though, it can be plausible to apply the concept of “period” to filmmakers’ work as we do to painters’ careers. Lars von Trier has been fairly explicit that after mastering a polished style for his work up through Zentropa/ Europa he wanted to try something new, and with The Kingdom he shifted toward a looser, on-the-fly style that pointed toward Dogme 95. Any viewer can be forgiven for thinking that Tarr has moved in the opposite direction of von Trier, from a pseudo-documentary approach toward something much more grave and majestic.

The first three theatrical features focus on the urban working class and their struggles to improve their lot. In Family Nest (1979), a family who can’t afford a flat of their own squeezes in with the husband’s parents. The tight quarters, the ceaseless complaints of the father-in-law, and the husband’s inertia force his wife and child to flee to the streets. The Outsider (1981) follows a young violinist as he drifts among jobs and into a passive marriage before being called up for military service. The family in The Prefab People (1982) has a flat and a decent job, but the wife finds the husband indifferent to her boring routines, and he looks for an escape in a job in another town. The concentration on ordinary people’s lives and the search for drama in the everyday dissatisfactions of city life put the films in the neorealist line of succession.

Stylistically, the films are stripped down in ways that also owe debts to modern traditions. Shot mostly handheld, adjusting the framing to the actors’ performances, they belong to a strain of films from the 1960s on that sought to suggest the immediacy of cinéma-vérité documentary. Unlike many such films, however, Tarr’s buy into a long-take aesthetic. Perhaps surprisingly, these movies’ shots run abnormally long: an average shot length of 32 seconds for Family Nest, 33.5 for The Outsider, 47 seconds for Prefab People. By comparison, Hollywood films of these years were consistently running between 4 and 8 seconds per shot, and comparatively few European and Asian films rely on shots as lengthy as Tarr’s.

Most scenes in these three films are dialogues, and the camera holds intently, if shakily, on faces. This concentration is enhanced by the general absence of establishing shots. A scene opens more or less in the middle of a conversation, and we get a character already challenging another. The visual pattern is that of shot/ reverse-shot, and in most scenes the first face is counterposed to a second one by either a cut or a pan. Shooting on location in cramped rooms, Tarr makes his framings tight; in Family Nest, the jammed frames give us and the characters almost no breathing space.

By relying on more or less isolated faces in close-ups, Tarr can absorb us in the intimate drama while sometimes catching us off guard. For instance, when we get a single character without an establishing shot, there is often a momentary uncertainty about where we are, or when the action is taking place. We also can’t be sure of who’s present besides the speaker, so the close view of him or her leaves us hanging: To whom is s/he talking? We’re pushed to pay close attention to what the character is saying, looking for any clues to the dramatic context. Tarr’s tactic also delays the reaction of the listener; he may withhold sight of the conversational partner until s/he speaks. The effect, heightened by the lengthy takes, is to turn many of these scenes into monologues, in which a character pours out his or her reaction to a situation, and we’re forced to take that in more or less pure form.

By the end of Family Nest, Tarr is shooting entire scenes concentrated on a single face, and because we don’t know if there is anyone else present, we have to take the talk as virtually a soliloquy.

It’s as if Tarr invoked the stylistic schema of shot/ reverse shot and simply postponed or suppressed the reverse shot, leaving only an inexpressive shoulder in the foreground, if that. I’ve discussed the delayed reverse-shot as a convention of European cinema in an earlier blog, and Tarr makes ingenious use of it.

Tarr builds these films out of conversational blocks, punctuated by undramatic routines. The result is that often major plot actions take place offscreen, or rather in between the dialogues. Exposition that other filmmakers would give us up front is long delayed, with bits of information sprinkled through the entire film. In Family Nest, the father claims that he’s seen Iren having an affair with another man. We can’t be sure he’s lying because we haven’t strayed enough out of the household to judge her activities. In The Outsider, one scene ends with the drifter Andras telling Kata, a woman he has recently met, that he has a child by another woman. The scene ends with him smiling in indifference, leaving his sentence unfinished. In the next scene, a band strikes up a tune: Andras and Kata are celebrating their marriage.

Most filmmakers would show us more of the courtship and a scene of proposal, but Tarr moves directly to the next block, suggesting Andras’ laid-back heedlessness. Agreeing to get married is no big deal. Further, by skipping over the most obviously dramatic incidents, Tarr’s storytelling joins that tradition of ellipsis celebrated by André Bazin in his essays on neorealism. No longer does the filmmaker have to show us every link in the causal chain, and no longer are some scenes peaks and others valleys. By deleting the obviously dramatic moments, the filmmaker forces us to concentrate on more mundane preambles and consequences.

This block construction yields an unusually objective narration. These films lack voice-overs, subjective flashbacks, dreams, and other tactics of psychological penetration. We have to watch the people from the outside, appraising them by what they say and do. It is a behavioral cinema. True, Prefab People opens with a flashback: The husband is packing to leave his wife, and the plot moves back to an anniversary dinner that ends badly. But the flashback to the earlier phase of the marriage isn’t framed as the wife’s memory. When the plot’s chronology brings us back to the moment of the husband’s departure, the replay of the opening allows us to watch the characters with more knowledge of what is driving them apart. Unsurprisingly if you know Tarr’s earlier films, that replay is followed by a long monologue showing the wife expressing her sorrow at his departure, without any visual cues about who, if anyone, is listening.

Then, without preparation, we see the couple back together, shopping in an appliance store. How did they reconcile? Have their attitudes changed, or are they simply reconciled to their old life? Like Antonioni and many other modern filmmakers, Tarr doesn’t tell us such things. He simply ends his film on a long take of husband and wife riding expressionless in the back of a truck, as much pieces of cargo as the washing machine beside them.

After the Fall

The second-phase films do look and feel rather different. Almanac of Fall (1984), a story of duplicity and spite among people sponging off a well-to-do older woman, offers a wholly elegant mise-en-scene. Characters are often framed from far back, surroundings take on much more importance, the framing is stable—often with windows, doors, and furnishings impeding our view of the action—and the camera moves smoothly, often in arcs around stationary figures. The takes are even longer, averaging just under a minute. The rococo lighting (patches of color seem to follow actors around) and atmosphere of strained upper-class narcissism seem like quite a break from the working-class films. If I had to find an analogy to Almanac of Fall, it would be Fassbinder’s Chinese Roulette (1976), with its camera arabesques and slightly decadent ostentation.

The overripe shots of Almanac of Fall signaled a shift toward a self-consciously formal cinema, but then Tarr stripped his settings and cinematography down. From Damnation (1988) onward, his films feature ruined exteriors, shabby interiors, elaborate chiaroscuro, rhythmic camera movement, and very long takes. (Damnation has an ASL of 2 minutes; Sátántangó, 2 minutes 33 seconds; Werckmeister Harmonies, 3 minutes 48 seconds).

Tarr insisted in conversation with me that there isn’t a sharp break between early and late styles. For one thing, his video piece Macbeth (1982) consists of only two shots across 63 minutes. It was made before The Prefab People, so his shift toward the ambulatory long take was already in the works. Moreover, The Outsider ends with a strained restaurant encounter captured in a virtuoso handheld shot running nearly seven minutes. A nightclub scene in The Prefab People likewise features some sidewinding long takes around a dance floor that wouldn’t be out of place, at least in their repetitive geometry, in Damnation.

If we’re inclined to look for other continuities, we can find them. In the films from Damnation onward, the deferred reverse shot has been put at the service of attached point of view, so that often when Tarr’s protagonists peer around a corner or out of a window, instead of optical pov cutting we have an over-the-shoulder view that conceals their facial reaction. One scene in Damnation starts as a typically Tarrian scrutiny of texture, with the wrinkling wall echoing Karrer’s topcoat. But then the camera arcs and refocuses, showing what Karrer is watching but not how he responds.

The blocklike construction of scenes in the early films carries on in the later work, but now Tarr minimizes the cuts within a scene, so that it becomes an even more massive hunk of space and time. Tarr refuses as well to use crosscutting, which would show us various characters pursuing their activities at roughly the same time—another strategy that keeps us fastened to one relentlessly unfolding chain of actions and, usually, one character’s range of knowledge. The avoidance of crosscutting will have major structural implications in Sátántangó, which overlaps characters’ individual points of view by replaying certain events and stretches of time.

The long-held facial shots of the early films don’t create a natural arc; the shot will go on as long as the character wants to talk. Similarly, many long takes in the later films don’t present a beginning-middle-end structure. We simply follow a character walking toward or away from us, pushing into a stretch of time whose end isn’t signaled in any way. This becomes especially clear in those extended long shots in which a character walks away toward the horizon and the camera stays put. Traditionally, that signals an end to the scene, but Tarr holds the image, forcing us to watch the character shrink in the distance, until you think that you’ll be waiting forever. Likewise, the diabolical dance shots of Sátántangó, built on a wheezing accordion melody that seems to loop endlessly, are exhausting because no visual rhetoric, such as a track in or out, signals how and when they might conclude. Early and late, Tarr won’t hold out the promise of a visual climax to the shot, as Angelopoulos does; time need not have a stop.

Nonetheless, I do agree with my fellow panelists that the later films have a significantly different look and feel, and it’s on them that Tarr’s place in world film history will chiefly rest. As I indicated at the end of Figures Traced in Light, he stands out as a distinctive creator in a contemporary tradition of ensemble staging. Like Tarkovsky, he shifts our attention from human action toward the touch and smells of the physical world. Like Antonioni and Angelopoulos, he employs “dead time” and landscapes to create a palpable sense of duration and distance. Like Sokurov in Whispering Pages (1993), he takes us into an eerie, Dostoevskian realm where characters are cruel, possessed, mesmerized, humiliated, and prey to false prophets.

Ties to tradition

Tarr, however, maintains that his work, early or late, owes little to cinema. He claims not to have been influenced by other directors, and he asserts that he gets his ideas from life, not from films. When pressed, he admits that he knew the films of Miklós Jancsó “and I liked them very much. But I think what he does is absolutely different from what we do.”

It’s not uncommon for strong creators to reject the idea of influence, and many feel that they may sap their originality if they’re exposed to other work. Still, nothing comes from nothing. Any artwork is linked to others through an expanding network of affinity and obligation. Often influence is like influenza; you catch it unawares, despite your efforts to ward it off. And sometimes artists on their own find strategies that other artists have already or simultaneously hit upon.

Whether or not Tarr consciously joined a tradition, his practices do link him to several trends. Tarr has rejected the idea, floated by Jonathan, that his early films are indebted to Cassavetes, but there seems little doubt that by 1979, when Family Nest was released, it contributed to the fictional-vérité tradition, regardless of his intent. Likewise, his late films’ reliance on long takes is part of a broader tendency in European cinema after World War II. The neorealists taught us that you could make a film about a character walking through a city (The Bicycle Thieves, Germany Year Zero), and other directors, such as Resnais in the second half of Hiroshima mon Amour, developed this device. With Antonioni, Dwight Macdonald noted, “the talkies became the walkies.” Jancsó took Antonioni further (acknowledging the influence) in the endless striding and circling figures of The Round-Up, Silence and Cry, and The Red and the White. So even if there wasn’t any direct influence, Antonioni and Jancsó paved the way for Tarr; they made such walkathons as Sátántangó and Werckmeister thinkable as legitimate cinema.

Still more broadly, as Hollywood cinema has become faster-paced, accelerating its action and cutting, art cinema in Asia and Europe has tended toward ever slower rhythms. Visit any festival today, as Scott mentioned in our panel, and you’ll see plenty of films with long takes and fairly static staging. I criticize this fashion a bit in Figures, but it’s undeniably a major option on today’s menu. It’s even been picked up in contemporary American indies, with Gus Van Sant’s work from Elephant on offering prominent examples. He, of course, has been crucially influenced by Tarr, but Hou, Tsai Ming-liang, Sokurov, and other directors haven’t. We seem to have a case of stylistic convergence, with Tarr choosing to explore the long take at the same time others were doing so.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

Within recent Hungarian cinema, it would be fruitful to examine Tarr’s relation to his contemporaries. Janós Szasz’s Woyzeck (1994) takes place in a wasteland not unlike those of Damnation and Sátántangó. Even closer to Tarr is the work of György Fehér. I’ve seen only Passion (1998; right) and one scene from Twilight (1990). Here again we get very long takes with a supple camera, grungy settings, and down-at-heel characters wandering in rain and mist or dancing as if possessed by demons. Fehér has worked with Tarr as producer, dialogue writer, and “consultant.” We could also explore Tarr and Fehér’s affinities with Benedek Flieghauf, the younger director of The Forest (2003) and Dealer (2004). Fleghauf builds these films around extensive long takes, and the remarkable Forest carries the idea of the suppressed reverse-shot to an eerie extreme, as characters study mysterious offscreen objects that may never be shown us.

More generally, and more speculatively, we could look to a wider movement in late and post-Soviet art toward mournfulness and lamentation in response to cultural collapse. Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia is one instance, but Larissa Shepitko’s The Ascent (1976) and Elem Klimov’s Come and See (1985) point in this direction too. Vitaly Kanevsky’s Freeze, Die, Come to Life! (1989) offers a rusting, dilapidated world not far from Tarr’s. In the 1970s and 1980s, composers like Arvo Pärt, Henryk Górecki, Giya Kancheli, Vyacheslav Artyomov, and Valentin Silvestrov created austere, threnodic music that sometimes evokes spirituality but just as often suggests a bleak end to everything. The very titles—Symphony of Sorrowful Songs (Górecki), Symphony of Elegies (Artyomov), Postludium (Silvestrov)—evoke something more than the death rattle of Communism. The pieces can be heard as meditations on the ruins of modern history, asking what humankind has accomplished and what can come next. Tarr’s severe parables, grotesque and sarcastic in the manner of Kafka, don’t exude the religiosity we can find in some of this music or filmmaking, but, at least for me, they share the impulse to lament humans’ inability to transcend their brutish ways. “I just think about the quality of human life,” he remarks, “and when I say ‘shit’ I think I’m very close to it.”

I have more ideas about Tarr, especially on Sátántangó and Werckmeister, but I have to stop somewhere. I hope to see his new film The Man from London when I go to the Vancouver International Film Festival next week, and of course I’ll report on it here.

The best piece of writing I know on Tarr’s cinema is András Bálint Kovács’ “The World According to Tarr,” in the catalogue Béla Tarr (Budapest: Filmunio, 2001).

Béla mesmerizes Lola, Chicago 15 September 2007.

Thanks to Milos Stehlik, Susan Doll, Charles Coleman, and Megan Rafferty of Facets, to Béla Tarr for generous conversation, and to András Kovács for enlightening discussions over the years.

PS 20 September: The reports of Tarr’s earlier visit to Minneapolis are emerging; here’s a good link.

Two more to TANGO

The passionate Tarrians (Tarrophiles?) Gabrielle Claes and Jonathan Rosenbaum have written me after my note on SATANTANGO. Gabrielle points out that the film won the L’age d’or prize, an award given during the Belgian Cinemathèque’s annual Cinedécouvertes festival. In the spirit of Bunuel’s classic, the award is given to films that challenge and disturb accepted notions of cinema. The festival, held the first two weeks of every July, is wonderful as a whole, too. It was here that I saw my first films by Kitano, Kiarostami, Hou, and many other directors I’ve come to love.

Jonathan points out that his essay on Satantango, which I mentioned was published in his book Essential Cinema, is also available online from the Chicago Reader site. This piece contains a lot of ideas and information, including background on the source novel.

TANGO marathon

David here:

How often do you get four chances to see a seven-hour-plus movie? In the late 1990s I went to two film festivals that were showing Béla Tarr’s Sátántangó (1994), and I missed it both times. Not that I don’t like long, slow movies, or that I wasn’t curious about a movie so many critics were praising, but at both events I needed to see other films, like old Hong Kong classics, that were scheduled opposite Sátántangó.

My third chance to see it was a variant of this situation. I was in Brussels at the Cinémathèque Royale watching Mizoguchi Kenji movies in preparation for what became Chapter 3 of Figures Traced in Light. I had the rarest Mizo of all, Aienkyo (The Straits of Love and Hate, 1937) on an editing table for a single day, and I knew that I would be watching it very slowly. (Normally a five-reel film takes me five to six hours.) But on the same day the archive was running Sátántangó.

What to do? I compromised and watched the first installment of Tarr’s film.

The first shot, now famous, was a stunner. Cows wander through the churned mud of a village square, amble slowly to the camera and then drift to the left, the camera sliding along with them. Eventually they shamble into the distance. All the while, hollow, bell-like chords throb on. Great cow ensemble performance and a dawdling, slightly ominous introduction to a strange world: I was ready.

What followed was nearly as impressive, with a deliberate pacing and attention to detail that overwhelmed the minimal story action. Light sifted through lace curtains, and grimy people in moth-eaten sweaters talked about a mysterious deal. In a remarkable sequence, running many minutes, the obese village doctor noted down his neighbors’ comings and goings. One shot had me gaping: the camera moves from studying a mangy dog through the window, then slips down to the doctor’s sketch pad and then follows him around the cramped bedroom with perfect fluency before returning to the window and revealing, in the distance, the repetition of an early action outdoors.

I had to leave.

I spent the rest of the day and a good part of the night in front of Aienkyo. Mizoguchi’s film hasn’t survived well, and the source material was as rainy with scratches as some scenes of Sátántangó are drenched in showers.

No regrets; the Mizoguchi was superb. But still….

Other chances came up: My friend András Bálint Kovács had sent me two VHS tapes of Sátántangó, and I bought a no-name DVD that turned out to be pulled from the same VHS source. But the lustrous black and white of the print I saw in Brussels made me feel vaguely dirty about watching the rest of the movie on video dubs.

Intrepid projectionist Jared Lewis before screening the 26 reels of Sátántangó.

Photo by Tom Yoshikami So it was yesterday that I finally had my fourth chance to see Sátántangó, and Kristin and I grabbed it. Tom Yoshikami, our fine UW Cinematheque programmer, had wanted to bring it for years, but deals had fallen through until last spring, when a small Tarr package began to tour.

It would be presumptuous to talk with assurance about the film after only one pass (okay, 1-1/3 passes). I hope to read and think about it more. There’s a lot for me to assimilate, both in print and on the Internet. So far, I’ve benefited from Jonathan Rosenbaum’s influential discussion (and his early review reprinted in Essential Cinema, apparently not available online), Peter Hanes’ enlightening career survey of Tarr, some helpful Vancouver program notes, a thoughtful discussion at moviemartyr.com, and the anthology Béla Tarr (published by Filmunio Hungary in 2001 and already hard to find*).

A DVD from Facets is scheduled for release next month, and doubtless this will trigger many critical studies. In the meantime, here are some tentative comments and questions.

1. Although the villagers in Sátántangó are united within a common project (apparently) involving the sale of cattle, other characters only tangentially connected–the doctor, a little daughter of a local prostitute–are given a lot of screen time. So the film becomes a “network narrative,” in which various characters separated by various degrees thread their way through the tale. Oblique as it is, the film obeys the conventions of this form, often set in a town or neighborhood in which people know one another. Later the characters migrate elsewhere, but the script maintains the sense of tenuous connections among the characters, like the motif of the spiderweb that circulates through the second installment.

2. The overall structure of the film, split into twelve parts, apparently derives from Laszlo Krasznahorkai’s novel, as yet untranslated into English. Each section adheres roughly to one or two characters’ range of knowledge, and as a result several events during the first couple of days of the action get replayed, fitted together as we come to understand them somewhat more fully. (The exposition is pretty stingy, nonetheless.)

It’s interesting that the film was completed in 1994, the same year as network stories became prominent with Short Cuts, Chungking Express, and 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, and that the replay-retrofitting tactic is seen as well in another 1994 release, Pulp Fiction.

3. The film’s pacing, very consistent in its solemnity, is accentuated by a soundtrack that is maniacally repetitive. The nondiegetic underscoring consists of drifts and whiffs of themes floating in the manner of ambient music, but more teeth-grinding is the clanging of a bell clapper in the third installment. Even cheerful music, like the accordion melodies played in the shabby tavern, rasp your nerves by being mindlessly reiterated. The endless dance in the pub, a spectacle of unimaginative drunken mirth, starts out amusing, becomes disturbing, and ends by being annoying. Maybe this is how they dance in hell.

As a minimalist film, Sátántangó seems to exploit what Minimalist composers like Philip Glass and Steve Reich have found: by pushing repetition to a limit, you can negate the sense of momentum and suggest that the action is hovering in a kind of pulsating stasis.

4. Did I say minimalism? The film consists, by my on-the-fly count, of 172 shots (including the chapter titles), across 434 minutes (not counting the final credits). That creates an Average Shot Length of about two and a half minutes. Quite a comparison with contemporary American cinema! Still, people who’ve actually seen the film probably expect the average to be much longer. (Angelopoulos’ The Hunters averages well over three minutes per shot.) Some shots of course run for many minutes, but others are fairly brief.

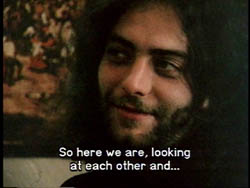

What sheer numbers don’t capture is the surprise of a relatively fast-cut scene coming quite early. In the second chapter, “Rise from the Dead,” Iremias and Petrina are interrogated by the Captain. This sequence of more or less orthodox shot/ reverse-shot comes as almost startling after several oblique, elliptical long-take sequences. The tight facial framings as the Captain enunciates his doctrine of freedom and order emphasize a central thematic issue. At the same time, Iremias’s deceptive air of innocence prepares us for the charisma he’ll project in relentless close-up as he delivers his quiet harangue over the dead body. He is, after all, named Jeremiah.

5. Tarr’s long takes, like the one in the doctor’s study which so captivated me years ago, are often virtuoso. What’s striking, though, is that the effects are achieved more through camera movement than through staging. Whereas Mizoguchi, Hou, Angelopoulos, Sokurov, and some others often move their actors around before a static camera, Tarr usually plants his people in one spot and lets the camera spiral around and over them. The camera probes a static space rather than records a shifting one.

True, the characters may advance or retreat from us, but I didn’t notice any of the delicate crossing of character trajectories, or the almost unnoticeable blocking and revealing of figures, that we get in the masters of ensemble staging. The most obvious movement comes when the characters set off down those endless roads or across the bleak plain, and then if the camera doesn’t hang reticently back (signaling the end of a shot or scene) it will retreat from their advance or follow patiently behind as the wind and rain lash them.

These shots are surprisingly open-ended. They could go on forever. They don’t anticipate a process of development and completion, as other directors’ long takes do, and they don’t climax in the sort of visual epiphanies beloved of Angelopoulos and Tsai Ming-liang. These directors like to build the take in stages, paying it off with a monumental spectacle (Angelopoulos) or a pictorial joke (Tsai). Tarr just charges ahead, without hinting how, when, or if, the shot will end.

Miklós Jancsó put the intricate choreography of actors and camera on Hungary’s film agenda, and his films, some consisting of fewer than thirty shots, become dizzying displays of panning, tracking, and zooming. Tarr, like many successors in any tradition, may be accepting certain premises of his elders (here the long take) but refusing others. He avoids Jancsó’s “maximalist” spectacle and turns toward something more spare, discomfiting, and attuned toward details.

6. One of the great accomplishments of the film is its tactility. Not only do you feel the blasting wind and constant drizzle, but you get to scrutinize the human face with an intensity that recalls La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Persona. If it did nothing else, Sátántangó restores the specific gravity of faces to a cinema that often forgets the weight of mottled skin, graying stubble, matted hair, and baggy eyelids.

And not just faces. Light streams through bottles and dingy glasses, reveals the smudges on an appliance switch, and traces the texture of torn sweaters and cracked buttons. Flies sweep into the shot and crawl over lapels. Objects reclaim their right to exist, refusing to cooperate with characters. When the conductor tries to lift a box onto his cart, it resists his first push and he tips it awkwardly into place. I’m reminded of film theorist André Bazin’s remark that Italian neorealism discovered a storytelling form that restored the concreteness and uniqueness of things in the phenomenal world, their obstinate refusal to fit willful human impulse.

One of Tarr’s most memorable shots coasts slowly along the body of the doctor, fallen to the floor in a stupor. We move from his face to his bloated middle, held in place by a shabby sweater, and then to his legs, finishing on the heels of his boots. As the shot ends we see a straw embedded in a clot of mud. No other boots in the world look like these.

The respect for trembling surfaces recalls not only Dreyer but Tarkovsky, supreme filmmaker of water and moist earth, and the Sokurov of The Second Circle and Whispering Pages. I’m reminded, more unexpectedly, of Aki Kaurismaki, who grants his paunchy, greasy-haired losers the integrity of living in tangible, unidealized bodies. At moments, the film’s grimly comic baring of human greed and gullibility recalls Kaurismaki, although he retains a certain optimism that I don’t find in Tarr.

7. The historian in me wants to know where this comes from. Few commentators mention that Tarr is part of a broader trend that includes György Fehér, who evidently makes rather similar films. His Passion (1998), screened for the 2001 session of the Society for the Cognitive Study of the Moving Image, is rather similar stylistically. It sets the situation of The Postman Always Rings Twice in a milieu as grubby and melancholy as that of Sátántangó, and its long-held takes (45 shots in about two hours) are less elegant, and carry some of the clumsiness of Feher’s overcoated, big-booted characters. At the same conference, Laszlo Tarnay of the University of Pecs also showed us a clip from Twilight (1990), which was to me even more impressive. Fehér was a producer on Sátántangó and worked with Tarr on other projects.

More broadly, it may be that Tarr, Feher, Alexei Guerman, and other post-Communist filmmakers have founded a new tradition of bleak, fine-grained realism that blends with challenging formal artifice in both image and sound.

8. There is so much to enjoy here that I hesitate to venture a qualm. I’m not yet convinced that the film needs to be so long! Some of the scenes, especially that showing the officers rewriting Iremias’s informing letter, seemed on my first look to be prolonged for the sake of filling out the pace. I’m also not sure that we need to see everybody walk into the remote distance. Moreover, I think the film (like, again, the work of Bergman, Sokurov, Tarkovsky, and so on) sometimes wobbles toward pretentiousness.

But these are very preliminary notes from a screening that was on the whole an exuberant experience. Not at all grueling!

Kristin and I went home, where I watched Inter-Pol 009, a 1967 Hong Kong James Bond imitation in lush color, with fast-cut gunplay.

It’s all cinema.

PS: Tarr has apparently resumed shooting an English-language feature with Tilda Swinton, The Man from London.

*But try the publisher: MONTAZS, Harsfa Útca 40, 1074 BUDAPEST; Tel: +36 1 461 0844; Fax: +36 1 461 0845.