Archive for the 'Directors: Tsui Hark' Category

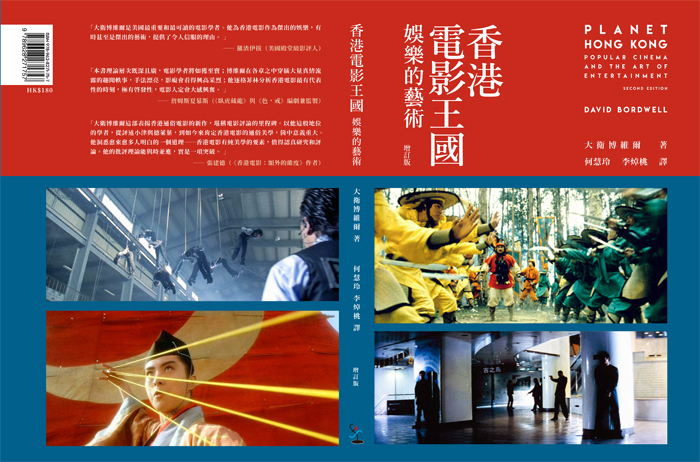

PLANET HONG KONG comes to . . . Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Film Critics Society has just published a Chinese long-form translation of the second edition of my Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It can be ordered from the HKFCS bookshop. Sample pages and further information can be found here. I’m grateful to Li Cheuk To, Alvin Tse, and their colleagues for preparing and checking the text and finding nice pictures.

That second English-language edition dates back to 2011–a distant past in terms of the rapid changes in world cinema. So for this translation, I wrote a postscript last year, and at the suggestion of Cheuk To I’m posting it here. The book is dedicated to Ho Waileng.

Revisiting Planet Hong Kong

Raymond Chow Man-Wai and Louis Cha Jin Yong both died in 2018. Journalists seeking a strong hook might take these unhappy departures as emblematic of changes in Hong Kong film culture—marking the “end of an era,” as we say. But Chow retired from the scene in 2007, and Cha finished revising his classics at about the same time. They stand, of course, as towering figures in Chinese cinema, but from my perspective today’s Hong Kong film is for the most part continuing processes that started quite far back. In other words, and much to my regret, the golden era ended some time ago.

I wrote the first edition of Planet Hong Kong in the late 1990s. As I explain in the book, I had been watching some Hong Kong films since the 1970s and got interested in the 1980s creative developments. By 1995, when I first visited the territory, those developments were already fading, though that wasn’t obvious to me. The local market was becoming unstable, regional tastes and investment sources were shifting, and the mainland economy was expanding. That age, undeniably golden, was ending.

When I interviewed local executives for the book, some said that they thought Hong Kong could become the “Hollywood of China.” Perhaps, they thought, all the experienced talents and financial and technical resources of the territory would be much sought after as China opened up its market.

By the time I came to revise the book in the early 2000s, such idealism had waned. As you’ll see in the pages that follow, it became obvious that Chinese authorities had shrewdly manipulated the market and the infrastructure to build up a powerful domestic industry. The rise of that industry, along with the waning of Hong Kong film, led to the biggest growth of a national film business ever seen in history. And those processes would assimilate Hong Kong creative talent on the mainland’s terms.

Now, as the 2010s come to an end, it seems that all the trends that I traced in the 2011 edition have continued, even accelerated. From 263.8 million viewers in 2010, mainland attendance has risen to over 1.6 billion in 2017. In 2010, the mainland claimed theatrical revenue of US$1.5 billion; in 2017 those were $8.27 billion. According to official figures, 970 feature films were produced in 2017. Although most of those were not released theatrically, it still remains a colossal achievement.

Over the same period, Hong Kong cinema continued in stasis. Production hovered between 42 and 64 annual releases. Theatrical admissions were likewise fairly flat, at an average of 25 million a year. Box-office revenues in 2010 came to US$179.4 million, and moved to $237.9 million in 2017. This is a substantial increase, but rising ticket prices (seen in every film culture) is likely one cause. Part of the rise, which occurred in the mid-2000s, is probably due to the emergence of 3D exhibition, which yields premium ticket pricing. And the greater part of that box office did not accrue to local films.

Certainly Hong Kong professionals at all levels were important resources for the growing mainland industry. Stars were and still are sought for major roles, and figures from decades ago, such as Chow Yun-fat, Tony Leung Chiu-wai, Shu Qi, and Andy Lau Tak-wah, can still draw audiences. Directors Tsui Hark, Jackie Chan, Stephen Chow Sing-chee, Peter Chan Ho-sun, Chang Pou-soi, Wong Jing, Johnnie To Kei-fung, and Stanley Tong Gwai-Lai found success in China, mostly with coproductions. The biggest coup of the era, Wolf Warrior 2 (2017; above) with its 154 million admissions, came from Wu Jing, a veteran actor and martial artist in Hong Kong films. Just as important, Edko, Emperor Motion Picture Group, and other local companies gained from producing movies for the mainland audience.

More broadly, the mainland box office was keeping Hong Kong film alive. A “local” film was likely to have mainland investment, and when it played there it had a good chance of making much more money than at home. SPL 2: A Time for Consequences (2015) took in less than US$2 million in Hong Kong but won over $90 million in China. Wong Jing’s From Vegas to Macau 2 of the same year captured $154 million there, as opposed to $3.6 million in Hong Kong. Through the 2010s, even a moderate success on the mainland could recoup far more money than it could in the tiny local market. To some extent the growing market to the north replaced the regional South Asian market that had sustained Hong Kong film in earlier decades. (How that market was lost is traced in Chapter 3.)

China cultivated homegrown directors as well, especially those who adapted conventions of Hong Kong and South Korean romantic drama and comedy to the local milieu. For any year, then, the top twenty films at the Chinese box office typically consisted of a mix. There would be imports (nearly all from Hollywood), domestic films by prestige directors (Zhang Yimou, Feng Xiaogang et al.), local genre films by younger hands, and two or three big box-office attractions steered by Hong Kong directors.

Coproductions that found mega-success in China didn’t register as strongly in Hong Kong. Tsui’s Flying Swords of Dragon Gate (2011), Jackie Chan’s CZ12 (2012), Peter Chan’s American Dreams in China (2013), Raman Hui’s Monster Hunt (2015), and Tsui’s Journey to the West: The Demons Strike Back (2017) all failed to crack the local top ten. Stephen Chow seems to have lost his hometown following: Journey to the West: Conquering the Demons (2013) failed to score big there, while The Mermaid (2016) did, but in seventh place, below Marvel superheroes and the local thriller Cold War 2.

Not that the territory’s audience was particularly loyal to locally-sourced product either. The waning attendance I noted in Chapter 10 persisted. For the period 2010 to 2018, no more than two local films won a place in any year’s top ten. For three of those years, none did. In 2018, Project Gutenberg ranked number 12, the only local film to appear among the top thirty contenders.

Granted, in most countries, especially small ones, domestic films don’t get big box-office returns. Hollywood films dominate, with only one or two local productions finding a place on the year’s top ten. Still, those of us who remember when Hong Kong films ruled the local market have to see the stagnation as saddening. Nonetheless, with China offering many more opportunities for investment and rewards, it’s remarkable that there remains a local industry at all—and one turning out four or five dozen features a year.

Those films have tended to follow the templates established decades ago: romantic comedies, domestic dramas, films of social comment, and urban action pictures. Filmmakers have updated those genres with digital production and mostly skillful use of modern technologies of color control, computer effects, and elaborate camera movements, including the use of drones for aerial shots. But anyone familiar with classic Hong Kong film will recognize the persistence of traditional plots and story premises. Golden Job (2018) brings back the rascals from the Young and Dangerous series to execute a heist, under circumstances that strain their brotherhood. Project Gutenberg (2018) revisits the Chow Yun-fat mythos with a counterfeiting story (shades of A Better Tomorrow) that allows him to wear white suits, brandish guns in both fists, and participate in a twisty plot that owes something to the 1990s narrative stratagems I discuss in Chapter 9.

The continuity should hardly be surprising, because a great many veteran creators are still active. Producer Raymond Wong Pak-ming, who co-founded Cinema City and went on to create Mandarin Films and Pegasus Motion Pictures, continues to release films. Yuen Woo-ping was a choreographer and director in the 1970s and achieved worldwide fame with The Matrix (1999) and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000); he recently directed Master Z: The Ip Man Legacy (2018). Ann Hui, Tsui Hark, and many other directors from the 1970s remain top figures in a film culture that offers many opportunities to venerated talents.

Although I’ve long admired Hong Kong films in many genres, readers of of Planet Hong Kong know that I believe that the action film—as wuxia pian, kung-fu movie, or cops-and-robbers thriller—was the area of its most long-lasting contribution. The tradition of powerful physical action, gracefully executed and forcefully staged and cut, was a genuine contribution to the history of film as an art form.

For that reason it’s a pleasure to report that the “ordinary” action pictures of the last decade have by and large maintained that tradition. Donnie Yen Ji-dan, an actor who chooses intelligent projects, endowed films like Kung Fu Jungle (2014), the Ip Man vehicles (2008-2019), and Chasing the Dragon (2017) with vivid, exciting sequences. He and other filmmakers seem to have abandoned the looser camerawork of the early 2000s and returned to precision shooting: fixed camera, instantly legible compositions, and a flow of movement across shots that can accelerate, slow, or halt, all in the service of impact on the viewer.

Still, in the hands of a skillful craftsman any technique can work. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s White Storm (2013), a full-bore male melodrama in the John Woo manner, mixes run-and-gun handheld style with a revival of the forceful compositions and crisp editing of the heroic-bloodshed days. Cheang Pou-soi’s Motorway (2012) invests a simple plot with excitement through nearly abstract shots of cars gliding through streets and alleys, augmented by stretches of ominous silence.

Similarly, I see the positive legacy of the Infernal Affairs series (2002-2003) in franchises like Overheard (2009-2014) and Cold War (2012, 2016). While not as tightly contained as the trilogy, these films benefit from plotting that is less episodic and more finely woven than we find in the policiers of the 1980s. They also judiciously insert florid action sequences, creating a sort of middle ground between the bureaucratic intrigue of Infernal Affairs and the more extroverted spectacle of something like Police Story (1985)—or, come to think of it, any of Jackie Chan’s Police Story titles.

There’s much to be said about Tsui Hark’s PRC adventure sagas as well, particularly in their use of 3D. (The Taking of Tiger Mountain, 2014 above, is a mind-bending use of that technology.) But for my purposes here I’d like to focus on two other major talents that I analyzed in the second edition. Both made outstanding contributions to the action picture in the years since the second edition was published.

Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (2013), despite being circulated in varying versions, remains for me a powerful achievement. It carries on Wong’s persistent experimentation with decentered narrative, following not only Master Ip Man but also his chief rival Razor and Gong Er, daughter of Ip’s one-time adversary. As I suggest in a blog entry this diffuse treatment of the major characters may bear the traces of a multiple-protagonist plot reminiscent of Days of Being Wild. In addition, through strategic flashbacks and shifts from character to character, this “chaptered” film evokes the interrupted and embedded story lines of other Wong films.

Stylistically, The Grandmaster makes fresh use of distended time and slow-motion imagery; these are conventions of the kung-fu genre as well as a signature of Wong’s work. More unusual is what I call in the blog entry the “mosaic” texture he builds up through close-ups that can be put in various places in one scene or another, or even one version or another. In general, I think that Wong alters the thematics of the martial-arts film by emphasizing Gong Er’s tragic dilemma: defeating the man who killed her father both sustains and erases her family’s legacy. And, as we might expect with Wong, the film strikingly parallels martial-arts prowess with impulses toward romantic love.

Another major film of 2013, Johnnie To Kei-Fung’s Drug War, is no less characteristic of its creator. (I analyze it in another blog entry.) A cat-and-mouse intrigue between crooks and cops, it depends heavily on our filling in gaps and reading characters’ minds. Police officer Zhang tries to penetrate a drug-smuggling outfit, and he devises a perfect To/Wai Ka-fai strategy: He sets up two meetings with two kingpins who don’t know each other. At each meeting Zhang impersonates the other guy. This game of shifting identities, of symmetry and doubling among roles, is a common narrative device of the Milkyway films, but in Drug War it’s given new urgency and a great deal of suspense. One economical shot brings the two unsuspecting gangsters together in the same frame as they leave and enter elevators.

At the same time, the informant Timmy is playing his own game—one that it may take a couple of viewings to decipher. As in The Mission (1999), many scenes of Drug War consist of men looking at each other, trying to divine hidden intentions—here, framed in the simplest possible shots, mere faces seen inside adjacent cars. Timmy’s eventual double-cross culminates in one of the cruelest shootouts to be found anywhere in To’s work; its bleakness recalls the end of Expect the Unexpected (1998). Throughout his career, To’s originality and craftsmanship in this rich genre have made him one of the great contemporary directors.

Wong completed only The Grandmaster in the years I’m considering, but To remained quite productive. Romancing in Thin Air (2011) and Don’t Go Breaking My Heart 2 (2013) returned to the mode of white-collar romance that Milkyway had made its own, while The Blind Detective (2013) combined that eccentric tone with an off-center cop premise recalling Mad Detective (2007). Life without Principle (2011; discussed in this entry) was a striking use of multiple-character plotting to make incisive points about the financial crisis.

Office (2015), an adaptation of Sylvia Chang’s popular play, was at once a flamboyant musical and an experiment in 3D. In Three (2016) To took up the challenge of a tightly circumscribed time and space, tracing the raid on a hospital ordered by a triad who’s there in police custody. Milkyway produced films by others, notably Motorway and Trivisa (2016), an opportunity for three first-time filmmakers to collaborate on a feature with three intersecting story lines. This last effort was in keeping with To’s dedication to creating programs and award competitions for newcomers to the industry. He remained one of Hong Kong’s most imaginative and tireless creators.

I should mention one more tendency, and it’s an encouraging one. Both editions of Planet Hong Kong pointed out that the Hong Kong people, contrary to the stereotype, actually cared a great deal about politics, especially after 1989. Recent years have seen a resurgence in films explicitly about activism in the territory. An early example is Matthew Tome’s documentary Lessons in Dissent (2014), a stirring account of struggles over educational policy and voting rights, featuring the most heroic 15-year-old I’ve ever seen. The 2014 Umbrella Revolution brought forth Evans Chan’s Raise the Umbrellas (2016) and Yellowing (2016; below) by Chan Tse Woon of Ying e chi There was also the ambitious speculative fiction Ten Years (2015), an ensemble of stories forecasting political repression in 2025. It’s very encouraging to see these efforts to insist on free speech and social criticism.

Finally, it’s worth pointing out how much classic Hong Kong film anticipated developments in Hollywood. The comic-book franchises that found new popularity with X-Men (2000) and Spider-Man (2002) and the Dark Knight trilogy (2005-2012) feature chivalric warriors with extraordinary fighting skills and weaponry. Like the knights-errant of wuxia fiction and film, these superheroes can leap high in the air and subdue villains with secret fighting techniques. Some, like Iron Man, have an equivalent of “palm power.”

Sometimes the American films have acknowledged their sources in Asian martial arts traditions, as when Batman trains as a ninja (Batman Begins, 2005) and Doctor Strange studies under a sifu in his 2016 film. The combat scenes, full of flips and somersaults, owe a great deal to the acrobatic traditions on display in Hong Kong cinema. If the result lacks the precision and visceral punch we find in classic Hong Kong films, it’s still worth noting that Westerners have learned that kung-fu, fights in mid-air, and elegant swordplay look cool on the screen. Hollywood should thank Hong Kong for helping invigorate the American action film.

A few words about what the original book tried to accomplish. At the most basic level, I wanted to understand Hong Kong cinema as an industry, an artistic tradition, and a cultural force. At the same time, I wanted to study it as an example of a popular cinema, one that developed strategies of storytelling and style and emotional appeal that were accessible to millions of people around the world. I wanted to analyze its unique contributions to the development of film art, so that meant I had to do some comparative work, situating Hong Kong film in relation to other traditions—most notably, that of Hollywood. At another level, I was interested in particular genres, especially the action film, and directors. As a result, parts of the book—mostly the “interludes”—are devoted to a particular filmmaker or group of filmmakers. And while I expected that many readers would already be Hong Kong film fans, I wanted to persuade skeptical readers that this national cinema was worth respect. This overall project I tried to amplify in the second edition you’re now reading.

Since the last edition, I have not followed Hong Kong cinema as intensively as I would have liked. Other projects have diverted me. But I have never lost my admiration for this cinema, this culture, and this citizenry. Watching Hong Kong films and visiting the territory have added a new dimension to my life.

From my first stay in 1995, when Li Cheuk-to introduced himself to me during the festival, through many visits over the decades, I have always treasured my friends there. So many people helped me in my research—people attached to the festival, to the archive, to the industry—that to list them all would add too much to this already overlong postscript. But they are mentioned throughout the book, and I hope they know how much I appreciate their generosity over the years. I’ll be happy if anything I’ve done here and elsewhere, in other writing and teaching, have helped film lovers better appreciate the astonishing contributions of Hong Kong film to world cinema artistry.

Among those valued friends was the kind and dedicated Ho Waileng. A tireless worker for the festival, she also translated the first version of Planet Hong Kong into Chinese. She remains in the hearts of everyone who knew her.

P.S. 10 August 2020: We in the US are now accustomed to being shocked but not surprised. I woke up to learn that Jimmy Lai, maverick mogul and publisher of Apple Daily, and many of his colleagues were arrested under the new “national security” law. It’s ironic that President Trump, who has reportedly sought to jail our journalists, moved quickly to place sanctions on Hong Kong earlier this year. The latest crackdown may be a response to the U.S. condemnation of the bill’s restrictions on free speech. (I discussed them here.) An arrest warrant is out for an American citizen living in the U.S. because he advocates democracy for Hong Kong. A coalition of Democratic and Republican senators and representatives have sponsored legislation to widen refugee status for Hong Kongers. Another irony: It’s called the Hong Kong Safe Harbor Act.

Ho Waileng at Angkor Wat, 2006. Photo by Li Cheuk To.

Little stabs at happiness 3: You know, for kids

Iron Monkey (1993).

DB here:

Another entry (apologies to Ken Jacobs) of little things that cheer up lockdown. Previous entries are here and here. This one, unlike a couple to come, is suitable for all ages.

Why do I get a thrill from watching an apparently frail little boy beat the bejeezus out of unkempt bullies? More to the point, why weren’t there movies like Iron Monkey (1993) when I was a tad?

It’s a wing of the Tsui Hark Wong Fei-hung reboot saga that began with Once Upon a Time in China (1991), putting Jet Li on the world map. This installment is directed by Yuen Wo Ping, master choreographer of Crouching Tiger and The Matrix and no mean director himself. It’s a prequel, showing us the young Fei-hung learning his craft from his apothecary father and the mysterious robinhoodish Iron Monkey.

Before the main course, here’s a snack.

This one minute of graceful movement is one minute more than you find in most of our movies today. Do something short, smart, and crisp, and the camera loves it.

To see Young Wong finding his groove, here’s the scene in which he practices some fancy evasion and defense against heavily armed but fatally dumb thugs.

The subtitles provide a whole other level of diversion.

The whole film, featuring Donnie Yen and other Hong Kong stalwarts, is good dirty fun. Versions are available on streaming, but you should avoid the sanitized Miramax release. There’s also a 1977 kung-fu film bearing this English-language title, but its plot is quite different.

Note: The boy Wong is played by a girl martial artist, Angie Tsang Sze-man, who went on to become a wushu champion.

For an update on the situation in Hong Kong, here is a story in the Washington Post.

I write about the art and craft of Hong Kong martial arts movies in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment. It explains, among other things, why the subtitles are so weird (p. 78).

P.S. 15 June 2020: Thanks to Radomir Kokes (Douglas) for correcting my misattribution of The Transporter to Yuen Wo Ping. It was of course directed by the great Corey Yuen Kwai.

Little stabs at happiness 2: Short and sweet, in a city on fire

Shanghai Blues (1984).

While US streets pulse with protests against racism and police violence and a fascistic presidential regime, it’s worth remembering that we aren’t alone. Hong Kong has been through this many times, and there the people’s struggle is growing ever more acute. The idea of “burning together” (laam chau) is starting to seem the only option when civil remedies are met by oppression. Hong Kong identity, a palpable force of history, is at stake. As one of my HK correspondents writes: “When it comes it comes. I am sure we won’t just stand here . . . . We will keep fighting for our rights.”

It’s hard to find consolation in these times, but again, with apologies to Ken Jacobs for swiping his title, I offer you a pause to let film art take over. It’s especially poignant in that film, one of Hong Kong’s great contributions to world culture, can seize and hold moments of rapture. All the more ironic that this film, Shanghai Blues, is about ordinary people fleeing the mainland for the British colony to the south.

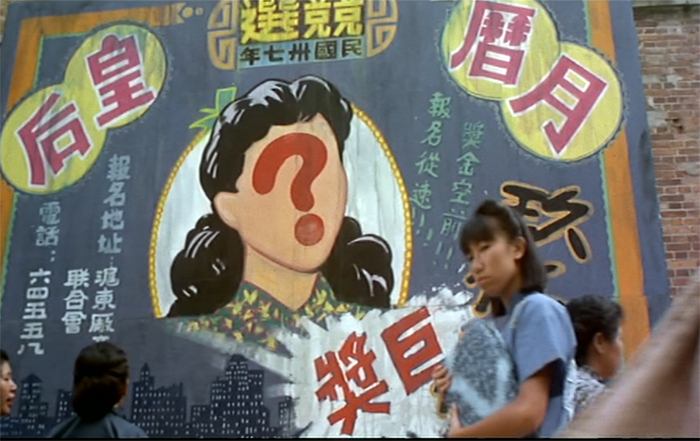

It’s as goofy a comedy as Tsui Hark ever made, but as usual with Tsui in his prime, it brims with energy. At the end of World War II, Doremi (Kenny Bee), an aspiring composer, is searching for the woman (Shu-shu, Sylvia Chang Ai-chia) he met and lost in a 1937 bombardment. But he’s living unwittingly in the same building she’s in. Meanwhile, a naive young woman (Sally Yeh Chia-wen) arrives from the country trying to make her way in the city. Over all hover two contests: a Calendar Queen prize, and a song competition.

Here’s the sequence that always makes me grin. Doremi comes out at night to play his composition. I really admire how Tsui synchronizes the rhythm of the visuals (especially Sally’s pop-up frame entrance) with the music.

Unfortunately, the film isn’t easily available. There’s a goodish French DVD, but no streaming source I know of. (My clips come from the laserdisc.) If you want more, and at the risk of a supreme spoiler, I offer you the climax, a reprise of the balcony moment that yields a happy ending and a bittersweet time loop.

This virtuoso scene is another example of Tsui’s skillful use of music, cutting, and composition. The movie may be set in Shanghai, but its shameless vivacity is pure Hong Kong.

Here are some resources if you want to help the people of Hong Kong. Thanks to Yvonne Teh for this link. Yvonne blogs, captivatingly, at Webs of Significance.

I write about Tsui, and Shanghai Blues, in Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment.

Shanghai Blues (1984).

PLANET HONG KONG: One more visit

Hong Kong, Central, April 2008.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third discusses principles of HK action cinema here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. That was followed by a tribute to western Hong Kong fans and then by a photo gallery of directors. Today’s installment is the last. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D, which will appear later this week.

Since the 1980s, the film festival circuit has become the only distribution system to rival Hollywood’s global reach. A big-name festival publicizes a film, some high-end critics at the festival write reviews, then once the film opens in a region or country, critics at large review it. As smaller festivals pick up films from the bigger ones, until eventually films make their way to small cities around the world. This process is parallel to the one that the studios orchestrate, though they have more centralized control. Video distribution, the circulation of DVD screeners, and Internet reviewing complicate this picture, but I don’t think they change the essential role of the festival network.

Just as film scholars have started to pay attention to fandom (see this post), they’ve started to ask research questions about festivals. As very few films from overseas find their way to U. S. screens, scholars keen on current cinema have realized that they need to visit festivals. It’s like scholars of painting traveling to exhibitions and gallery shows, or opera aficionados attending premieres at Bayreuth and La Scala. And film scholars of certain genres or periods have realized that they can do on-the-fly research by visiting historically oriented festivals like Pordenone and Bologna.

These days I see more of my colleagues at various festivals. In particular there’s the peripatetic Bérénice Reynaud, an early example of the multitasker (critic, programmer, professor, fan). On the same circuit I meet Virginia Wright Wexman, Peter Rist, Mike Walsh, Jim Udden, Gary Bettinson, and many other profs. So I’m starting to think that festivals are giving academic film studies a fresh charge of energy. Reciprocally, the events at Pordenone and Bologna, which began as cinephile events, have invited academic researchers to help program them and write for their publications. In sum, festivals are now a vigorous workspace for not just screenings and critical write-ups but discussions about ideas that would normally haunt the groves (or is it grooves?) of academe.

Saturation booking

Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. Hong Kong, 2000.

I had dropped in at screenings at the New York and London film festivals in the 1970s and 1980s, and I had steadily attended the summer Cinédécouvertes series in Brussels. But I had never “done” a festival intensively until I went to Hong Kong in the spring of 1995. There I saw films that still stay with me: Through the Olive Trees, Postman, In the Heat of the Sun, A Borrowed Life, Smoking/ No Smoking, Quiet Days of the Firemen, Taebek Mountains, 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, Whispering Pages, and Clean, Shaven. (My one big miss was Sátántangó; I had to wait years to catch up with that.) Who says the 1990s were a meager decade? Can any festival today come up with a menu like this?

I had gone, as I explain in the Preface to Planet Hong Kong, mainly to check on local cinema. The “Hong Kong Panorama” surveying 1994 releases yielded a bumper crop, including some titles I’d seen only on laserdisc (Chungking Express, Ashes of Time) and others that were revelations. Above all, there was a retrospective—an entire festival in itself, really—dedicated to early Chinese and Hong Kong cinema. They swept over me in a heaving wave: Love and Duty (1932), The Eight Hundred Heroes (1938), Boundless Future (1941), and many others, along with postwar Hong Kong classics like Where Is My Darling? (1947), Song of a Songstress (1948), The Kid (1950), with Bruce Lee, and on and on. The series was capped by stunning restored Technicolor prints of The Orphan (1960), also with Bruce, and General Kwan Seduced by Due Sim under Moonlight (1956). Some of these had circulated on poor VHS copies, but most were, and still are, unknown in the West.

I had picked the perfect year to come to the festival. Looking back at the notes I scribbled in the dark, I realize that over three weeks I got a crash course in Chinese film history. In any given day I was given more to think about, and certainly more to feel about, than I got from almost any academic conference.

For those of us interested in non-Hollywood cinema, festival programmers and critics are central gatekeepers. They scout the ridge and scan the horizon, and around the campfire they teach us film lore. They’ve built up fingertip knowledge about movies, moviemakers, distribution patterns, sales agents, theatre circuits—in sum, the workings of world film culture. The best of these gatekeepers are intellectuals, ready to search out something stimulating in even the most marginal film. They have honed their senses to detect qualities that could provoke an audience or yield a lively Q & A or a piquant catalogue entry or a solid review. Out of pure selfishness, I wish I could download the neural storage files of Alissa Simon, Richard Peña, Tony Rayns, Cameron Bailey, and their peers. Alas, there is no app for that.

In Hong Kong I met Li Cheuk-to, Jacob Wong, Freddie Wong, and many other programmers, along with Athena Tsui and Shu Kei. What made my experience that spring of 1995 so thrilling were their months of patient planning and sleepless nights behind the scenes—finding the prints, arranging for them, writing catalogue copy and, not least, assembling a massive reference work like Early Images of Hong Kong & China, one of the precious books the festival managed to turn out every year to document the local cinema.

Many programmers are also critics, and such was the case in Hong Kong. When I arrived, Cheuk-to and his colleagues had just formed the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, and I was invited to their first awards ceremony. They were mostly young, and after the awards were handed out I was invited out to dinner with several of them. It was then I realized that here was a local film culture in which criticism mattered. Hong Kong was small enough for critics to band together to debate their cinema. Soon another critics’ group was founded, and the debates spread. I started to understand that if one were to study a film culture, one would have to grasp the dynamics of taste among schools of critics and between critics and their audiences. I made an effort to describe this dynamic in the second chapter of Planet Hong Kong.

It’s not just that that book had its origins in that first visit. And it’s not just that the newest edition is the result of my attending the festival for the last fifteen years. More important, my ideas about film and about the world changed when I met critics, programmers, and other academics in Hong Kong. Immersion in one of the world’s most fascinating cities had something to do with it too.

Favorites, for now

As Tears Go By (1988).

In my first entry in this hurriedly posted series, I listed around 25 Hong Kong films that most aficionados consider of major importance—historical, artistic, cultural, or all three. In the days since, I’ve mentioned several other films that you can check into. Here, as an envoi to this yakathon, are a few more movies that I’ve repeatedly enjoyed, and that I’ve sometimes talked about in PHK 2. They’re grouped in very loose categories.

Lesser-known items from major directors. Once a Thief is a good example. Sandwiched between Woo’s official classics is this good-natured, somewhat silly action comedy about art thieves, romance, and parenthood. Lifeline is one of my favorite Johnnie To Kei-fung films—not as formally audacious as his later masterpieces, but containing one of cinema’s great action sequences involving a fire that seems as unstoppable as a waterfall, with the bonus of a throat-catching epilogue. Ann Hui On-wah’s Summer Snow, about a busy career woman who must treat her Alzheimer’s-affected father, glows with the intimate realism and understated sentiment that inform her more recent The Way We Are.

Everybody knows some works by Wong Kar-wai, but I think his later accomplishments have overshadowed his debut, As Tears Go By, a prototype of the arty gangster movie. Drenched in romanticism, it has one of the great music montages in Hong Kong film and a finale that you feel lifting from genre formula to pictorial poetry. With Johnnie To as well, even offbeat items like Throw Down are getting well-known, but I’d like to make a pitch for the New Year’s mahjong comedy Fat Choi Spirit. It has some of the 1980s nuttiness; the laughs start at the DVD menu.

Tsui Hark has produced so many films that have been fan favorites–Peking Opera Blues, Once Upon a Time in China, and Swordsman III: The East Is Red–that you can’t expect anything worthy to be overlooked. And yet not enough people have seen the bouncy Shanghai Blues, with moments of musical rapture, and The Chinese Feast, with all his faults and virtues bundled into a celebration of cooking and eating. There’s also The Blade, a convulsive revenge saga that seems to me one of the best movies made anywhere in the 1990s. After it’s over, you’re not sure what hit you.

Drama, comedy, dramedy. Any reader of PHK knows my fondness for the gender-bending romance Peter Chan Ho-sun’s He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, a lovely integration of musical, coming-of-age story, and satire of sex roles. But my favorite Michael Hui film, Chicken and Duck Talk didn’t feature in the first edition because I couldn’t get my hands on a print to illustrate it. Tracing the rivalry between a scruffy duck restaurant and a Japanese knockoff of Colonel Sanders, it yields many hilarious sequences, perhaps most notably Hui’s efforts to conceal a plague of rats from health inspectors.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

My associates sigh when I mention Wong Jing. What can I say? I find some of his films funny. Try Boys Are Easy, Tricky Master, and, probably my favorite, Whatever You Want. If you don’t like them, write my suggestion off as David in his Dotage. Speaking of silliness, I’m not over-fond of Stephen Chow, but All for the Winner, Flirting Scholar, From Beijing with Love, and A Chinese Odyssey are ingratiating enough. Square that I am, I like Shaolin Soccer too.

I’d add the medical melodrama C’est la Vie, Mon Cherie, the unpredictable cop stakeout movie Bullets over Summer, and the poignant Juliet in Love, about a triad’s attraction to a woman recovering from a mastectomy. Sylvia Chang Ai-chia’s quiet romantic dramas Tempting Heart and 20 30 40 are also rewarding. Patrick Tam Kar-ming’s films are still unjustly neglected, so anything might be considered obscure, but I was delighted when a passable DVD of My Heart Is that Eternal Rose was released. Here Tam lyricized the gangster movie; Wong Kar-wai took the next step.

For grotesque comedy, try You Shoot I Shoot, about a contract killer who adds value by having an aspiring director film the hits (complete with slo-mo) for the delectation of the client. Unclassifiable is The Inspector Wears Skirts II, a cop-training story that pits women recruits against dimwitted men. It includes a dance sequence displaying minimal skill and maximal cheerfulness.

Fight club: Of Chang Cheh’s vast output of martial-arts movies, I have a special affection for New One-Armed Swordsman, a spectacularly mounted action picture, and Crippled Avengers, in which “disabled” really does mean “differently abled.” For Lau Kar-leung, I especially admire Legendary Weapons of China, one of the strangest of his forays into the arcana of martial arts lore and Chinese history; Shaolin Challenges Ninja (aka Heroes of the East), a sort of Taming of the Shrew, but with throwing stars; and the harrowing Eight-Diagram Pole Fighter, something of a valedictory for the Shaolin tradition at Shaw Brothers. Both these directors made so many worthwhile films that you can spend a lot of agreeable time exploring their output.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

In the crime vein consider Kirk Wong’s hard-driving and pitiless Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop and Danny Lee’s Law with Two Phases (not a typo). Ringo Lam’s films are notably tougher and more tactile than those of his contemporaries; see his deromanticized classic City on Fire, the effort to out-Woo Woo that is Full Contact, and the lesser-known Full Alert. Eddie Fong Ling-Ching isn’t known for policiers, but Private Eye Blues was one of the films I enjoyed in the 1995 Panorama. His historical drama Kawashima Yoshiko is even more remarkable.

Connoisseurs know The Outlaw Brothers; one glimpse of the climax, in which a gunfight is interrupted by a hailstorm of poultry, usually convinces any viewer to take a closer look. I must add the below-the-radar ensembler Task Force, by John Woo protégé Patrick Leung Pak-kin. Gratifyingly untidy in skipping among the personal lives of a cop squad, it eventually focuses on the need to settle conflicts without violence—after, of course, supplying some snappy fight scenes of its own.

Post-handover take-outs. Most of the films I’ve mentioned are from the 1970s through the 1990s. But many worthy films have emerged in the 2000s. If they don’t always carry the effervescence of the earlier ones, many are solidly crafted. Some are discussed in Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and many more have received commentary on other websites (e.g., LoveHKFilm), so I’ll just mention a few that seem to me of more than transitory appeal.

Patrick Tam’s After This Our Exile is an unsentimental look at how an aggressive, heedless father must come to terms with his little boy. Needing You is a better-than-average office comedy, while Hooked on You is poignant in the gruff Hong Kong way, with a touching finale about the changes since 1997. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s action pictures usually deliver sturdy value in the old style. Try Connected, a remake of Cellular; New Police Story, with Jackie Chan as a cop coming to terms with age and failure in the face of nihilistic youth; and Invisible Target, which boasts an old-fashioned Hard Boiled demolition derby, with a police station ground zero this time. Horror fans already know how uneven HK films in that genre can be, but surely Fruit Chan Goh’s Dumplings is an admirably creepy achievement, and Soi Cheang Pou-soi did good work in the genre as well (Diamond Hill, Horror Hotline) before moving to the suspenseful Love Battlefield and the harsh action picture Dog Bite Dog.

Whew! After seven sword-like days, I’m running out of time, and I haven’t achieved a final victory. Want more dangerous encounters? Go to PHK or the Hong Kong Critics Society Award winnerss and start looking for your better tomorrow.

Sorry, I couldn’t resist.

Kristin and I discuss film festivals as an aspect of global film culture in Chapter 29 of Film History: An Introduction. For detailed research into the festival scene, see Richard Porton, ed., Dekalog 3: On Film Festivals and several publications from St. Andrews University. The most recent volume, edited by Dina Iordanova and Ruby Cheung, focuses on East Asian events.

P.S. Thanks to Yvonne Teh for a title correction, and Tim Youngs for a geographical one!

Photo: Joanna C. Lee, courtesy Ken Smith.