Archive for the 'Directors: Varda' Category

An update about our blog

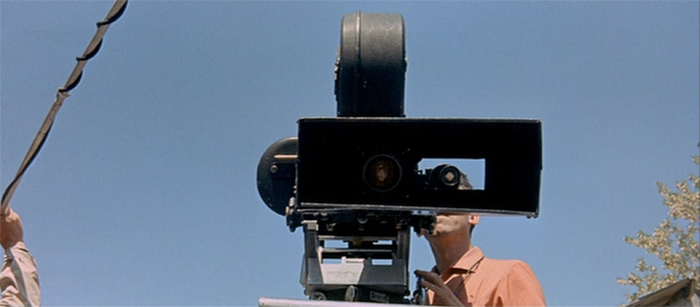

Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

DB here:

After fifteen years of fairly steady blogging, we suspended putting up new entries in early October. We were reluctant to go into explanations of a fluid situation, but now things are stable enough for us to set out what happened.

I had surgery for oral cancer in July and August, followed by brief hospital stays. My doctors, all excellent, have said and continue to say that my prognosis for recovery is good. After a hiatus of rest at home, when I posted two blogs, I went in for radiation treatments and chemotherapy. This process took six weeks and has left me very tired, while also dealing with side effects of the treatments and medications.

Since then, I simply have lacked the energy and concentration to write anything new. I try to find time for clerical cleanup work on my book manuscript, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. The plan is to submit it for production in March at Columbia University Press.

But Kristin, who has been devotedly taking care of me, and I now have a routine that should permit at least occasional blogging. She will of course provide her annual list of Best Films of the Year for 90 Years Ago, and she has some other ideas. I hope as well to offer something, though naps and streaming always seem to obtrude.

In some ways, there are a couple of substitutes for my blogging–both courtesy of Criterion. One is my video essay on Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Throw Down, “Hidden in Plain Sight.” A look at the movie’s characteristic narrative and stylistic strategies, it’s available on both the Channel and the blu-ray release. I’m grateful to Curtis Tsui, the producer, for asking me to do it; I now appreciate the film a lot more. The other bonus materials are extremely informative as well. If you haven’t seen Throw Down, what are you waiting for?

Before I went into surgery, I recorded two linked installments of our “Observations on Film Art” series. Both concern Godard’s use of aspect ratios. The first, on Vivre sa Vie, is available here. The second, on Le Mépris/Contempt, is here. I try to show how Godard exploits the differences between 4:3 proportions and the anamorphic widescreen format. (In a way, they balance the exploration of Godard’s late-career use of aspect ratios, seen in this blog entry.)

Kristin and Jeff Smith weren’t idle during our hiatus. The Channel released her analysis of the road motif in Pather Panchali and Jeff’s study of Agnès Varda’s editing in Le Bonheur. More installments are planned, of course. We appreciate our loyal viewers who have stuck with us through 45 episodes!

During my confinement, the books have kept arriving on our doorstep, and many deserve notice. I’d be remiss, though, if I didn’t call your attention to a couple of my favorites. One is J. J. Murphy’s monograph on The Florida Project. This in-depth exploration of Sean Baker’s creative process and the contributions of many collaborators is timely, given the release of Red Rocket. Besides, how many authors get the director they wrote about to do PR for them?

The other book is a magnificent contribution to our understanding of cinema: James E. Cutting’s The Movies on Our Minds: The Evolution of Cinematic Engagement. It offers a history of popular films from the standpoint of psychological engagement of the spectator. It shows “how they are structured, and how that structure has been crafted by a century’s worth of filmmakers to affect our minds.” Using Big Data (hundreds of films) and fine-grained analysis of cuts, lighting, and other techniques, James brings in evidence from empirical psychology to show that filmmakers are, as we’ve long known, “practical psychologists.” Beautifully designed with color illustrations, written in a conversational style, it’s destined to be a classic. I hope to blog about James’ book more at length when stamina returns.

It’s been heartening to see that we still get many pageloads every day; some of our efforts seem to endure. In addition, my colleagues here and elsewhere have been wonderfully kind in offering their support during these days. There are still months to go, but Kristin and I remain confident.

Contempt (Le Mépris, 1963).

The Mona mysteries: Varda’s VAGABOND on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

The Criterion Channel has just posted the latest in our Observations on Film Art series. In this installment I try to analyze Vagabond‘s shrewd and unsettling use of some traditional plot patterns: the road movie, the mystery investigation, and the network narrative. I argue that the orchestration of these patterns encourages us to think about our life choices.

You can watch the film here, and watch the video essay here.

Vagabond is a film I’ve admired since it came out in 1985, and by now it’s something of a classic. Its the original title, Sans toit ni loi (roughly, “Homeless and Lawless”) follows Varda’s habit of rhyming or punning titles: L’Opéra-mouffe, Daguerreotypes, Mur murs , Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse, Visages et villages. The mixture of playfulness and serious themes (homelessness, women’s rights, the struggles of the poor, the importance of ordinary people) makes her work unique. She respects both the problems of our lives and the possibility of finding something to affirm–if only our efforts to help one another. I was reminded of all these qualities by her last film, Varda par Agnès; seeing Vagabond again reminds me how much we miss her.

Several of our entries have been devoted to Varda; see the set here. In my view, Vagabond is her masterpiece, but she’s made many fine films, and a lot of them are available for streaming from Criterion.

Our entire Observations series is here. Thanks as ever to the Criterion team, especially Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and John Magary, who did a bang-up editing job. Thanks as well to Erik Gunneson here at UW–Madison. And thanks to colleague Kelley Conway for help with my scenario for this installment.

I discuss Vagabond as an example of ambivalent narration in the Afterword to “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” in Poetics of Cinema, 166-169.

Vagabond (1985).

A hundred years ago, and less, at Cinema Ritrovato ’19

DB here:

Hundreds of films, thousands of passholders, sweltering heat (105 degrees Fahrenheit on Thursday). Dazzling tributes to Fox films, Youssef Chahine, Eduardo De Filippo, Henry King, Felix Feist, silent star Musidora, sound star Jean Gabin, and other themes. Many filmmakers from Africa, South Korea, and Europe, as well as master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Yes, Cinema Ritrovato is on steroids this year.

And as we always say: There are so many tough, indeed impossible, choices. Kristin has been faithfully following the African series, while I’ve hopped between restored and rediscovered Hollywood classics and the films from 1919. Today I’ll report a bit on the latter, with an addendum on a major filmmaker’s ave atque vale.

1919 bounty

Song of the Scarlet Flower (1919). Production still.

By the end of the 1910s, the feature-length format had become well-established, and a bevy of directors in Europe and America were launching their careers. Abel Gance, Victor Sjöström, Mauritz Stiller, John Ford, Raoul Walsh, Cecil B. DeMille, Lois Weber, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, Mary Pickford, and many other figures had already made impressive work. 1919 brought us some outstanding titles. There was von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands, Griffith’s Broken Blossoms and True Heart Susie, Lubitsch’s Madame DuBarry, along with the lesser-known Victory of Maurice Tourneur, the first part of Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar, and the overbearing, delirious Nerven of Robert Reinert.

Bologna showed none of these. Its massive 1919 lineup featured some classics in restorations, notably Capellani’s The Red Lantern (starring Nazimova), Dreyer’s debut The President, and Stiller’s Herr Arne’s Treasure. As a sidebar there was the 1919 Italian serial I Topi Grigi, a fun sub-Feuillade exercise in crooks and chases with some nifty shots. And there were a great many fragments and short films from that year, including a Hungarian entry by Mihály (Michael) Kertész (Curtiz).

Less known than Stiller’s official classics is The Song of the Scarlet Flower, a wonderful open-air drama about a young farmer’s wanderings and his heart-rending romances with three women. In a new digital version, it emerged as one of the most sheerly beautiful films I saw at Bologna. The central action sequence, in which the hero dares to ride a log through rapids to the very edge of a waterfall, gained even greater tension thanks to the swelling orchestral score by Armas Järnefelt–the only original score to be preserved for a Swedish silent.

1919, German style

Der Mädchenhirt (The Pimp, 1919). Production still.

Then there were two remarkable German films unknown to me, both by directors better known for later work. Der Mädchenhirt (The Pimp) was by Karl Grune, most famous for The Street (Die Strasse, 1923). The plot follows a shiftless young man who casually becomes a pimp and pulls women into prostitution. Introducing the film, Karl Wratschko pointed out that many Weimar films warned of sexual misbehavior, and certainly the young hero of this film gets ample punishment for his sins.

Stylistically, Der Mädchenhirt was typical of much European cinema of the late ‘teens, when the tableau style, which promoted intricate staging with few analytical cuts, was losing force. Grune mostly handles action in ensemble shots broken up by axial cuts to closer views. If German filmmakers weren’t quite as editing-prone as other European directors, that may be because they didn’t have access to American models. Not until January 1920 were Hollywood films of the war years imported into Germany.

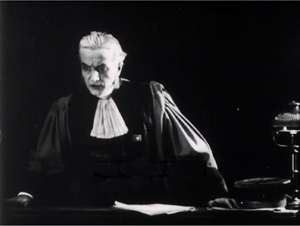

Another film carried this moderate continuity style to an intriguing extreme. Tötet nicht mehr! (Kill No More!) framed a plea against capital punishment within a family drama. Sebald, the son of a by-the-book prosecutor, falls in love with the daughter of a former prisoner. When Sebald is cast out by his father, the couple take up a theatrical career playing Pierrot and Colombine. But then Sebald blocks the theatre director from seducing his wife, so the director blackballs them and they can’t get work in other shows. Visiting the director, Sebald quarrels with the man and kills him. He’s arrested, tried, and sentenced to death.

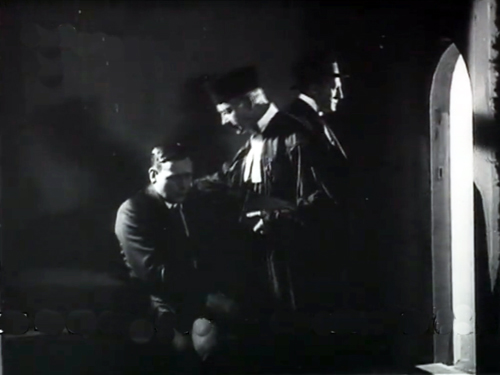

Tötet nicht mehr! displays some remarkable visual qualities. Cross-lighting in the climactic prison scenes sculpts Sebald, the priest, and the lawyer Landt in a bold variety of ways.

Director Lupu Pick (Sylvester, 1924) uses this dramatic lighting to enhance the tableau-plus-axial-cut approach. The police are examining the crime scene and questioning Sebald. A depth composition gives us the corpse in the lower foreground, the detectives in the middle ground, and way in the back, the barely-visible face of Sebald perched between the shoulders of the two central men.

One detective walks to the distant background to question Sebald. Anybody else would have staged this bit of action in the better-lit zone on the left, where a detective talks with his colleagues. Instead, far back, a single pencil-line of light picks out the edge of Sebald’s face and body.

An axial cut-in presents a tight two-shot of the cop and Sebald–again, made stark and tense by the lighting.

The plot of Tötet nicht mehr! is a generational one, starting with the tragedies befalling the woman’s father. These scenes introduce the sympathetic lawyer Landt, who tries to help the family throughout its troubles. Landt becomes the vehicle of the film’s message against capital punishment, which gets full airing in the boy’s trial.

In the films of the 1910s, courtroom scenes tend to be more heavily and freely edited than others. This is largely because of the need to cut among judges, jury, witnesses testifying, lawyers pontificating, and the onlookers. Pick exploits the situation with dozens of shots of participants. We also get optical point-of-view shots showing Sebald awaiting the jury’s verdict by staring at the doorknob of the jury room. There’s even a “lying flashback,” which dramatizes the prosecutor’s inaccurate reconstruction of the quarrel that led to the crime.

Most impressive, I think, is the pictorial progression in Landt’s impassioned plea to the jury to let Sebald escape execution. Among many reaction shots and reestablishing framings, Landt is rendered in increasingly close shots as he addresses the judges and the jury–and us.

The textural lighting and the ruthless elimination of the background reminded me of the trial scene of André Antoine’s Le Coupable of 1917, run at an earlier installment of Ritrovato.

There were plenty of other 1919 films on display, several of which I have yet to see. But this should give you an indication of the service that Cinema Ritrovato continues to render to the cause of understanding film history.

Not so long ago

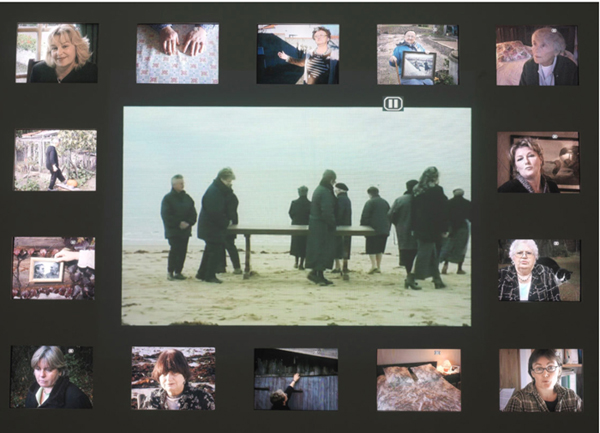

The Widows of Noirmoutier (2006).

Film history close to our time was the subject of Varda par Agnès, the filmmaker’s last statement on her career. Prepared during her final years of life and produced by her daughter Rosalie Varda, it’s a poignant and revealing account of what mattered to her in her work. It showed Varda’s wry, playful humor and her commitment to treating social issues in intimate human terms. It’s a body of cinema that grows ever more important each year.

Varda par Agnès also showed her characteristic sensitivity to overall form. It’s framed by bits of her talking to audiences in master classes, so she becomes the narrator. Some stretches are chronological, going film by film, but just as often the links are associational. The women of Black Panthers (1968) remind her of the abortion activists of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977). That’s about the friendship of two women, which suggests by contrast a film about a woman alone, Vagabond (1985). The beach of Vagabond summons up the plenitude of Le Bonheur (1965). And so on.

This might seem rambling, but it’s not. Varda explains that she often conceives her films with a strict structure–the strung-together tracking shots of Vagabond, the tight time frame and spatial coordinates of Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962). Varda par Agnès splits about halfway through, flashing back to Varda’s early still photography and adroitly linking that to her emergence as a “visual artist.”

She began mounting expositions like L’Îl et Elle, which housed cinema cabins (big transparent cubes made of ribbons of 35mm film) and Widows of Noirmoutier. Around a central image of collective grief, small screens show women sharing the everyday details of life without a partner. In just this clip, it’s almost unbearably touching. Apart from the resonance with Varda’s devotion to Jacques Demy, I was reminded of Chekhov’s line: “If you’re afraid of loneliness, don’t get married.”

We’ve been so busy with films, and queueing for films, that we’ve had little time to blog about our visit. Later entries will have to come after we’ve left Cinema Ritrovato.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Marianne Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

The complete score for Song of the Scarlet Flower is available on CD and streaming.

For Varda’s last visit to Cinema Ritrovato, go here. We discuss Varda’s career and Kelley Conway’s in-depth study of it here. See also Kelley on Varda at Cannes. A forthcoming installment of our Criterion Channel series is devoted to Vagabond.

For more on the stylistics of 1910s films, see the category Tableau Staging. I discuss The President in the Danish Film Institute essay, “The Dreyer Generation.”

The Criterion Collection’s magnificent Bergman collection wins Best Boxed Set at the annual DVD awards, Cinema Ritrovato 2019. Congratulations to producer Abbey Lustgarten and all her colleagues!

Ritrovato 2017: Many faces, many places

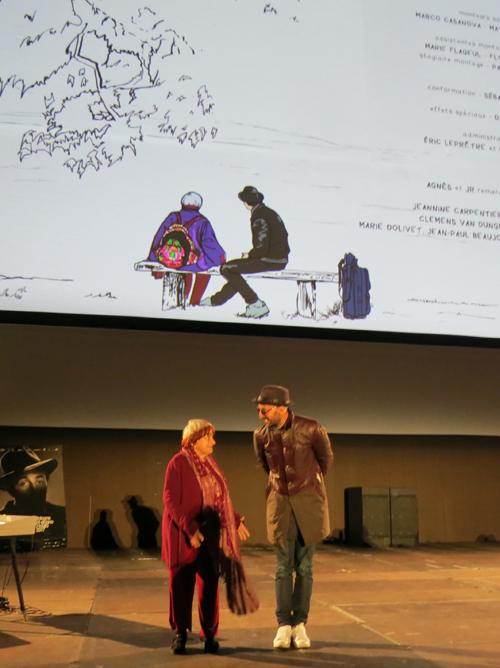

Agnès Varda and JR, Il Cinema Ritrovato, 1 July. Photo: DB.

DB here:

This final post from Il Cinema Ritrovato is no less a miscellany than the others. With over 500 films screened, Kristin and I invariably missed things that others raved about. Still, we saw enough powerful cinema to make us want to flag some key items for you.

Silents, please

Kristin has already mentioned one of the most startling items we saw, Le Coupable (1917) by André Antoine. I’m still processing the audacity of this film. The prosecutor in a murder trial abruptly claims the defendant as his son. We then get the familiar flashback format, shifting from the courtroom to the events leading up to the crime and the arrest. But the shifts between present and past are so quick, and the bits we see of the trial are given in such intense, stark singles, that they gain an astonishingly modern pulse.

Add in marvelous use of locations, real alleys and corridors and cafes, and you have a very impressive movie.

Once more, 1917 proves to be dynamite.

From the same year came Furcht (Fear), by Robert Wiene. Count Grevin wanders anxiously through his castle for about sixteen minutes of screen time before we realize, thanks to a flashback, that he’s haunted by his theft of a precious Indian statue, stolen from a temple. Soon a priest materializes, either on the castle grounds or in Grevin’s imagination, to declare that he has only seven years to enjoy life before vengeance strikes. Which it does, of course. Conrad Veidt plays the priest with the smoldering glare, and ambitious superimpositions show how committed German cinema was to special effects. Dr. Caligari was three years off.

Not that other years should be slighted. Le Collier de la danseuse (The Dancer’s Necklace, 1912) was an agreeably preposterous crime movie. (The thief has a jacket with fake hands dangling from the sleeves, just the thing for escaping handcuffs.) The film boasted the low, almost Ozuesque, camera height typical of other Pathé productions of the year.

Not that other years should be slighted. Le Collier de la danseuse (The Dancer’s Necklace, 1912) was an agreeably preposterous crime movie. (The thief has a jacket with fake hands dangling from the sleeves, just the thing for escaping handcuffs.) The film boasted the low, almost Ozuesque, camera height typical of other Pathé productions of the year.

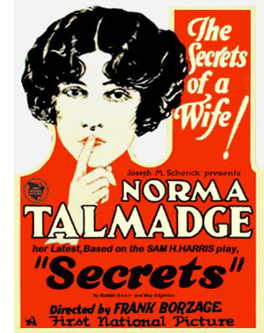

Borzage’s Secrets (1924) traces a marriage through three large flashbacks, with the first emphasizing romantic comedy, the second suspense, and the third family melodrama. Norma Talmadge, who savored a split-personality role in De Luxe Annie (1918), gets to play a woman at three ages here. The central section, devoted to a Griffithian siege on a lonely frontier cabin, showed Borzage’s ability to whip up enormous excitement, with an unexpectedly sad twist. The whole movie has over 11oo shots, indicating just how committed American filmmakers had become to fine-grained scene breakdowns.

All in all, the silent films on display this year were as revelatory as ever.

Cinematic geometries

The Abe Clan (1938).

For some years Ritrovato has included a Japanese sidebar curated by Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström. This year the theme was socially critical jidai-geki, or historical films. Some of them were fairly familiar to Western cinephiles because copies were circulated by the Japan Film Library Council from the 1970s onward. Examples include The Abe Clan (1938) and Fallen Blossoms (1938), both very good films. Along with these, the Bologna series gave the Yamanaka Sadao classic Humanity and Paper Balloons (1937) another well-deserved airing.

Some of these are fairly intimate dramas, others use a lot of spectacle. The image from Abe Clan above is fairly typical of the monumental turn some jidai-geki took in the late 1930s. Several of the films starred members of the left-wing Zenshinza kabuki troupe, perhaps best known to aficionados from Mizoguchi’s staggering Genroku Chushingura (1941-1942).

Three of the other films showed the range of this genre during Japan’s “dark valley,” its turn to authoritarian rule and imperial warfare. The Rise of Bandits (1937), by Takizawa Eisuke, was a rousing but melancholy Robin Hood tale. A lord’s honest son tries to save a shipment of gold from marauders, but he’s framed by his duplicitous brother. So he becomes the outlaws’ leader, at the cost of his wife’s life and his father’s trust. Some superb action sequences, including a fiery final assault on the castle, alternate with semicomic scenes among the bandits, with the hero’s cynical sidekick twisting not-too-bright thugs around his finger.

Hagiwara Ryo’s The Night Before (1939, production still above) was based on a Yamanaka script, and like Humanity and Paper Balloons, it braids together several characters’ fates. As rival samurai factions struggle during the Meiji restoration, ordinary people–an artist, a family running an inn, a young man wanting to make his name as a warrior, a bitter and disenchanted samurai–try to get by. One of the innkeeper’s daughters is attracted to the youth, another daughter who works as a geisha eyes the artist, and the old man seems to escape into endless games of shogi with a neighbor. The film has a panic-stricken climax, in which the factions collide in darkness along the riverside and innocents get swept up in the violence. As with many films in the series, the critique of mindless militarism isn’t far below the surface.

The Man Who Disappeared Yesterday (1941), by the great Masahiro Makino, is a murder mystery. An unpleasant landlord is the victim, and there are plenty of suspects. The scattered clues didn’t seem to me to play entirely fair, but the investigation is largely a pretext to explore adjacent households and obfuscate what turns out to be complicated post-murder maneuvers. At the climax, all the suspects are seated in a single line to hear the magistrate’s solution, just as if they were in Nero Wolfe’s office.

Makino’s style accentuates the spatial layout through a remarkable ten zoom-ins that yank us to one or another suspect as the explanation is given, sometimes with flashbacks. Camera zooms (as opposed to optical-printer ones, as in Citizen Kane) are rare in any national cinema of this period, and Makino uses them almost in the spirit of Hong Sangsoo, more to perk up our attention than to enlarge anything for closer scrutiny. (Admittedly, the last one rivets us on the guilty party.) The same geometrical impulse encloses the tale: an opening crane shot down, a closing one upward. As often in Japanese cinema, The Man Who Disappeared Yesterday marks and repeats film techniques to give a decorative flourish to the story.

Technique also comes to the fore, of course, in Divine (1935), a French production directed by Max Ophüls. The attraction isn’t just the dizzying camera movements, swimming through a tangle of backstage paraphernalia and crawling up stairways. Max is more than a master of the tracking shot. In one witty passage, framing and cutting coordinate to stretch the distance between a couple who can’t tear themselves away from each other. (In my last frame, the milkman’s head slides almost out of frame.)

The plot centers on a country girl who becomes a follies performer and is framed as a drug dealer by a Lothario and a lesbian. This contraption seems more or less a pretext for Ophüls to indulge his endless fascination with women striking poses for men while asserting their own demands. The abrupt and unexplained happy ending is the logical wrapup for a film less concerned with a plausible plot than a display of Woman in all her dazzling divinity. There. How’s that for a Sarris sentence?

Bigger than life

Although there were some repeats on Sunday, the final big event of the festival was the screening, to some 3000 people on the Piazza Maggiore, of the new film by Agnès Varda and JR. Kelley Conway reviewed its Cannes premiere for us earlier, and now that we’ve seen it, we like it a lot.

Varda has the ability to take a whimsical, borderline-cutesy idea and turn it into something poignant, as in Daguerreotypes and Opéra-mouffe. (Nursery-rhyming titles, like Mur Murs and Sans toit ni loi, encapsulate her attitude.) Her latest, an associational documentary along the lines of The Gleaners and I, depends on the premise of traveling through France and making enormous photographic portraits of ordinary people. These are then mounted on buildings in their home town–hence the title Visages Villages.

The result is both intimate and monumental. A postal clerk or a woman truck driver take on the billboard proportions of politicians and pop stars. Without any sense of slumming, Varda and JR can memorialize a woman living in a building about to be demolished, and can spare time for a haggard hermit who has dropped out of the system. It’s as powerful a populism as any you’ll see, but done with humor, genuine curiosity, and respect for the integrity of each subject. A playful approach to art can yield serious emotional effect.

As Visages Villages goes on, it turns introspective. Varda recalls episodes from her life and tries to incorporate one of her photos, a casual shot of Guy Bourdin, into a skewed tipsy WWII bunker rusting on a beach. She recalls young days with Godard and Karina, so that now when Godard dodges a meeting, she becomes rueful (“The rat!”). This lady gleaner is always gathering fragments, and we’re lucky she shares them with us.

Again Bologna gave excellent, overwhelming value. The surprises never stopped. Dropping into a film I hadn’t seen in three decades, Rancho Notorious, I not only had fun but realized once more Lang’s diabolical genius. A peculiar insert of a boot slipped into a stirrup puzzled me, but after an hour I got it. (Forgive me, Fritzie, for I knew not what I did.) Long may this festival flourish.

Thanks as ever to the vast and dedicated staff of Il Cinema Ritrovato, particularly Guy Borlée, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Mariann Lewinsky.

I discuss the trend toward monumental jidai-geki in chapters 12 and 15 of Poetics of Cinema. More detailed analysis can be found in Darrell William Davis’s book Picturing Japaneseness: Monumental Style, National Identity, Japanese Cinema.

Visages Villages (aka Faces, Places) is distributed by the Cohen Media Group.

Agnés Varda and JR. Photo: DB.