Archive for the 'Directors: Varda' Category

Three women of Cannes: A guest entry by Kelley Conway

Visages Villages (2017).

DB here:

Kelley Conway, friend and colleague here at Madison, has just made her first trip to the Cannes festival. All her adventures won’t fit on one entry, so she focuses this report on encounters with three outstanding women in French film culture: Agnès Varda, Laetitia Dosch, and Nathalie Coste-Cerdan. Kelley is the author of several books and articles on French film. Her recent book is on Varda, which we reviewed here. She wrote for us earlier this year on La La Land, and last year on French films at Vancouver.

Sneakers or heels?

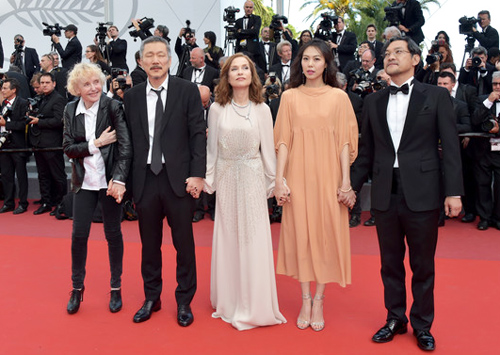

On the red carpet, Claire’s Camera creatives: Claire Denis, Hong Sangsoo, Isabelle Huppert, Kim Minheet, and Jeong Jinyoung.

The red carpet, replaced every day, is the epicenter. Standing on the edge, you’re mesmerized by the ritualized movement of humans across it. First, ordinary invitation-holders cross the carpet and move up the stairs and into the Grand Théâtre Lumière.

Once the mortals have taken their seats, the actors, directors, and L’Oréal models arrive. Women dressed in evening gowns pause and pose for the photographers while fans watch hungrily from beyond barriers and heavy security.

There are different styles of traversing the carpet. Dior-clad Rihanna took her time, striking vampy poses worthy of Theda Bara and apparently savoring every minute of the experience. No-nonsense legend Claire Denis moved briskly toward the stairs wearing a simple black pantsuit. Agnès Varda and JR, the photographer/muralist and co-director of Visages Villages, clowned it up.

Sometimes, in a gesture that is oddly moving, the director and actors who worked together on a film link arms, pose collectively, and stride the red carpet as one.

The videographers track the stars right into the theater. Once you get in and find a seat, you can follow other celebrities’ carpet progress thanks to a live feed. We watch them sit down and then we stand up, treating them to a standing ovation before and after the projection.

The videographers track the stars right into the theater. Once you get in and find a seat, you can follow other celebrities’ carpet progress thanks to a live feed. We watch them sit down and then we stand up, treating them to a standing ovation before and after the projection.

The whole thing seemed a little overwrought and absurd until I saw tears in eyes of Hong Sang-soo, Agnès Varda, and Laetitia Dosch, an actress you will soon adore. Cannes is a huge promotional machine and a herculean feat of event management, but flashes of humanity shine through.

Even bystanders are subject to a dress code. For afternoon screenings, I was allowed to wear my sneakers. For the evening screenings of the films in competition, heels are de rigueur for women. Men are allowed to retain their sneakers, but I set aside this injustice and contemplate other elements of the Cannes experience.

The mise-en-scène of women on the red carpet can make Cannes appear fatally retrograde; one must look to the screen and behind the scenes for evidence of the modern woman. Let’s take a look at three women (and there are many more, of course) who deserve a kind of scrutiny that exceeds the red carpet défilé: Agnès Varda, Laetitia Dosch, and Nathalie Coste-Cerdan. What have these women, a director, an actress, and an educational executive, contributed to Cannes?

The Director: Through the Eyes of Varda and JR in Visages Villages

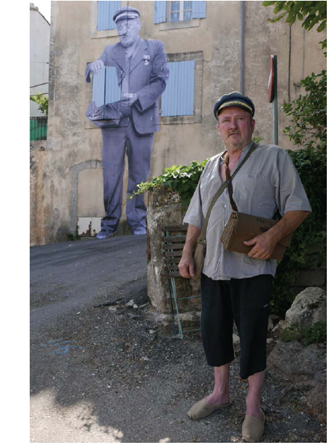

Visages Villages, which just won the Golden Eye Documentary prize at Cannes, is ostensibly a portrait of several small French villages. But it’s mainly a chronicle of a journey, an artistic collaboration, and a friendship between 30-something JR and 80-something Agnès Varda. JR is the hugely talented street artist and Instagram sensation, well known for his photographs and installations, notably his transformation of I.M. Pei’s glass pyramid at the Louvre in 2015.

As with Varda’s Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse and Les Plages d’Agnès, we accompany the filmmaker, this time with her new collaborator in their “photo truck,” as they travel through France, gleaning ideas and experiences. We meet retired coal miners, cheese makers, factory workers, a mail carrier, a waitress, and the stalwart wives of three dockers in Le Havre, and we watch Varda and JR create and display epic photographs of them. The resulting images render ordinary humans and their remote communities extraordinary.

As with Varda’s Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse and Les Plages d’Agnès, we accompany the filmmaker, this time with her new collaborator in their “photo truck,” as they travel through France, gleaning ideas and experiences. We meet retired coal miners, cheese makers, factory workers, a mail carrier, a waitress, and the stalwart wives of three dockers in Le Havre, and we watch Varda and JR create and display epic photographs of them. The resulting images render ordinary humans and their remote communities extraordinary.

As in her past work, Varda urges us to take a good look at people and places we have previously overlooked, exercising her extraordinary gift for making us care about strangers. But the film is not merely an empathetic social document on rural France. Visages Villages affirms the allure of art and art-making, or rather the “power of the imagination,” as Varda describes the focus of their film. We witness the various stages in the duo’s collaboration: planning, considerable horsing around, execution, and discussion of the outcome.

The film reminds me of Chronique d’un été (1961), which also sought to document the lives of ordinary people while chronicling a collaboration (between Jean Rouch, Edgar Morin and their friends). In Visages Villages the result of the collaboration is, typically, the creation of a monumental photograph of a person placed in an unlikely setting: the wall of a decaying building in an isolated village, a container at the port of Le Havre, a barn on a lonely farm. As Varda did with Mona in Vagabond, the lonely single mother of Documenteur, and the widows of Noirmoutier, Varda and JR imbue their subjects with dignity, while maintaining a respectful distance.

Visages Villages models a way of seeing and a way of being. JR and Varda laboriously plan and execute an installation consisting of a photo Agnès made in 1954 of the late photographer Guy Bourdin. JR and his crew construct a scaffold and paste the photo on the side of a massive bunker from W.W.II that had fallen from a cliff onto a Normandy beach.

We watch the whole thing come together beautifully via time lapse, only to learn that it was washed away by the tide within 24 hours. Instead of grieving the short life of the work of art, the pair move on, ready for their next adventure, which is how Varda has lived her whole life, fearlessly seeking new projects, curiosity and generosity intact.The human eyes and the spectre of Jean-Luc Godard are important motifs and Varda finds a way to merge them. A visit to Varda’s ophthalmologist, where she receives an injection to treat her macular degeneration, results in JR pasting a close-up of her eye on the cylindrical body of a gas truck.

JR propels Varda through the Louvre in a wheelchair, paying homage to Godard’s Bande à part and reminding us that looking at art has always been one of Varda’s passions. Near the end of the film, JR consoles Varda in Rolle after her old friend Godard callously stands her up, by finally offering her (but not us!) a glimpse of his eyes liberated from his habitual sunglasses.

In the hands of anyone else, this portrait of provincial people and an unlikely friendship might have resulted something thin and inconsequential. Instead, it’s a poetic window into the process of creation, an ode to the elevation of the ordinary, and a primer on the way to live.

The Actress: Jeune femme (aka Montparnasse Bienvenue, directed by Léonor Sérraille with Laetitia Dosch)

Two moments of stunning direct address bookend this beautifully acted, droll and moving film about a 31-year old woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The film opens with a scene of Paula (Laetitia Dosch) pounding furiously, first with her fists and then with her head, on the door of her unresponsive ex. While getting bandaged at a clinic, she rants extravagantly in direct address: “I was everything to him and now I’m nothing.” The final shot of the film reveals Paula staring directly at the camera again, this time calm and resolute, restored to a position of strength and hard-earned wisdom. Jeune femme is about a woman who comes to Paris to track down her ex, only to find a better version of herself.

I spoke with actress Laetitia Dosch about what it was like to create the role of Paula. Dosch worked in French boulevard theater and attended the prestigious two-year “Classe Libre” program of the acting school Cours Florent before enrolling at the Swiss National Conservatory, where she received a classical and avant-garde formation. Director Léonor Sérraille had recently won a screenwriting grant from the CNC and was looking for an actress to play the role of Paula when she saw footage of Dosch on YouTube. She wrote Dosch a letter and they soon began working together. Sérraille was busy during the day, but the two women found time to meet nearly every evening for six weeks. They discussed the character, explored Paris together, and saw films.

Dosch’s explosive performance in Jeune Femme, which is both highly verbal and often idiosyncratically physical, might lead one to assume that significant improvisation occurred during the shoot, but no. Sérraille’s script was meticulously written, even “écrit au millimetre,” Dosch said, which she appreciated, because it helped her “figure out how the character thinks.” The film charts the transformation of a slightly manic, spurned woman into a person who realizes she’s better off without her older, famous, photographer boyfriend, for whom she was a muse.

Dosch’s explosive performance in Jeune Femme, which is both highly verbal and often idiosyncratically physical, might lead one to assume that significant improvisation occurred during the shoot, but no. Sérraille’s script was meticulously written, even “écrit au millimetre,” Dosch said, which she appreciated, because it helped her “figure out how the character thinks.” The film charts the transformation of a slightly manic, spurned woman into a person who realizes she’s better off without her older, famous, photographer boyfriend, for whom she was a muse.

Our flawed protagonist leads a precarious existence. Essentially homeless at the beginning of the film, she benefits from the generosity of a lovely woman she meets on the subway by failing to correct the woman’s mistaken impression that Paula is her long-lost childhood friend from Lyon. She confiscates her ex-boyfriend’s cat and eventually abandons it at a vet clinic. But she cobbles together a life, babysitting a depressed little girl whose existence she brightens with cotton candy and aria singing; making repeated attempts to reconnect with her estranged mother; selling lingerie at a mall in Montparnasse, and making new friends, notably a single dad from Senegal with a degree in economics who works as a security guard at the mall. When circumstances force her to make some big decisions, she surprises us. As Dosch described her character, “This is the story of a muse who stopped being a muse, or rather became her own muse.”

It’s worth contemplating Jeune femme’s conditions of production. The crew was comprised mainly of women, most of whom graduated from France’s prestigious national film school, Fémis. The film was awarded an avance sur recettes by the CNC (Centre National du cinéma et de l’image animée), which afforded Sérraille the time to write the screenplay. Institutions such as Fémis and the CNC are the backbone of France’s celebrated cinema ecosystem. A portion of each film ticket sold goes to the CNC, which in turn, distributes the funds to nourish the entire system of film education, production, and exhibition.

Here, more than anywhere else in the world, state resources flow in the support of screenwriters, directors, and even exhibitors who make and show films that might not exist or thrive without aid. In 2016, for example, the French art et essai (art house) exhibition sector accounted for 22.4% of all film attendance in France and benefited from nearly 15 million euros in aid from the CNC. French films retain a relatively high local market share. They attract 35.8% of admissions, while 52.9 % go to American releases.

The Education Executive: Nathalie Coste-Cerdan

Fémis is an important part of the system. Nathalie Coste-Cerdan, until recently the Director of Canal +, is now the General Director of Fémis. Created as IDHEC in 1945, Fémis was restructured and renamed in 1986. The school, which graduates fifty students each year, is funded by the CNC and supervised by the French Ministry of Culture and Media and the Ministry of Higher Education. The current president of the school is Raoul Peck, who directed most recently I am Not Your Negro. Prestigious grads include Noémi Lvovsky, Arnaud Desplechin, François Ozon, Céline Sciamma, Marina de Van, and Rebecca Zlotowski.

Because the school is supported by the CNC, French students pay next to nothing (433 euros per year) for this four-year education. Foreigners must pay 10,670 euros per year, but this is still a bargain by American standards. Students must have a B.A. or M.A. before entering one of the six main programs at Fémis, which are directing, producing, screenwriting, sound, cinematography, and editing.

The school keeps adding programs. A new two-year program trains people who want to work in distribution and exhibition. Another new program, La Résidence, trains recent high school graduates in film production for one year and is aimed at enhancing diversity at the school. Yet another new program, also lasting one year, was created to train students in the writing of television series because “ambitious television series are not so common in France,” admitted Coste-Cerdan.

I attended a panel organized by the CNC at its beachfront headquarters at the Cannes Film Festival to hear about film education in France and elsewhere. Representatives from Fémis, Ciné-Fabrique in Lyon, and films schools in Poland and Argentina compared their schools’ structures, fees, curricular goals, and, especially, their efforts to support international exchanges. Coste-Cerdan asserted, “It’s impossible to be a national film school today without being international.” In line with this trend, Fémis accords 10% of its spots to foreign students, creates special programs for foreign students, and runs exchange programs with film schools in other countries.

Seeking to “encourage international co-productions, be on the cutting edge of the industry, and open students’ minds to other points of view,” the school sends each and every Fémis student abroad to study in a partner institution. Fémis students study screenwriting at Columbia University, documentary film at the Beijing Film Academy in China, or sound design at VGIK in Russia. Fémis sends students to, and accepts students from, CalArts, Tokyo University of the Arts, INSAS in Bruxelles, the Universidad del Cinea in Buenos Aires, and the Korean Academy of Film Arts in Seoul, among others.

One Fémis program, linked with the Filmakademie of Baden-Württemberg, offers a one-year course designed for aspiring producers. The training takes place in France, Germany, and England and includes sessions at the Cannes, Berlin, and Angers film festivals.

Fémis also offers yet another innovative tactic, a three-week program for European documentary filmmakers who wish to develop a documentary film based on archival material. Here, aspiring documentary makers get help with re-writing, the preparation of a dossier for financiers, tips for dealing with producers and broadcasters, and pitching skills.

The results have been encouraging. The “Gulf Summer University” at Fémis has had luck attracting nine students from the Gulf region for its 5-week training program. Recently, a young Chinese woman from the Beijing Film Academy came to Paris and made a “poetic, philosophical” documentary about the Chinese community in Belleville. Coste-Cerdan characterized the exchange programs as, among other things, an exercise in “soft power,” designed to export the ideals of French film system elsewhere and also to challenge French students by exposing them to other cultures.

Cannes is a mecca of glamour and an enforcer of hierarchies, of course, but it’s also a place where one can have a serious conversation about now to improve international film education. It’s a place where one can see comedies like Noah Baumbach’s The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), which is really good, by the way, but also films like Abbas Kiarostami’s gorgeous 24 Frames and Karim Moussaoui’s En attendant les hirondelles, a superb Algerian film. It’s also a place where one can see director John Cameron Mitchell, whose How to Talk to Girls played at Cannes this year to mixed reviews, serve as DJ and perform with a punk band at the “Queer Party.” It’s also a place where a taxi driver raved about the dialogue in the films of Michel Audiard and color design in Pedro Almodóvar.

I’d like to come back here some day, but I want to wear my sneakers on the red carpet, even at night.

Thanks to Agnès Varda, Laetitia Dosch, Françoise Pams, Pierre-Emmanuel Lecerf, and Nathalie Coste-Cerdan for their kind cooperation.

The 1162 French film theaters categorized as art et essai received, on average, 12,820 euros each in 2016. See “La Réforme de l’art et essai,” Le Courrier art et essai, n. 256, May 2017, 12.

Red carpet photos by Zimbio and Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images; Coste-Cerdan photo from Times Higher Education Supplement. Other photos by Kelley Conway.

P.S. 28 May 2017: Jeune Femme won the Caméra d’Or prize for best first film.

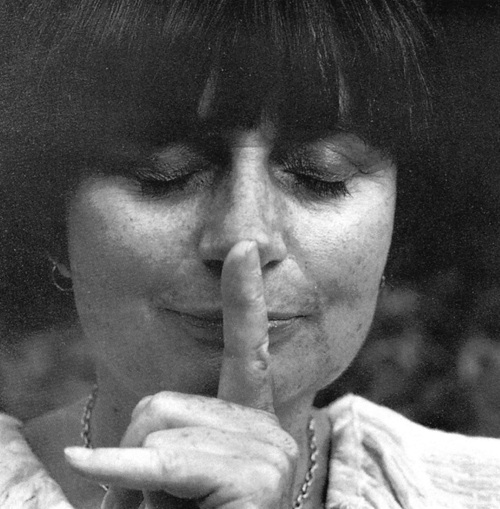

Still Agnès

Self-portrait by Agnès Varda.

DB here:

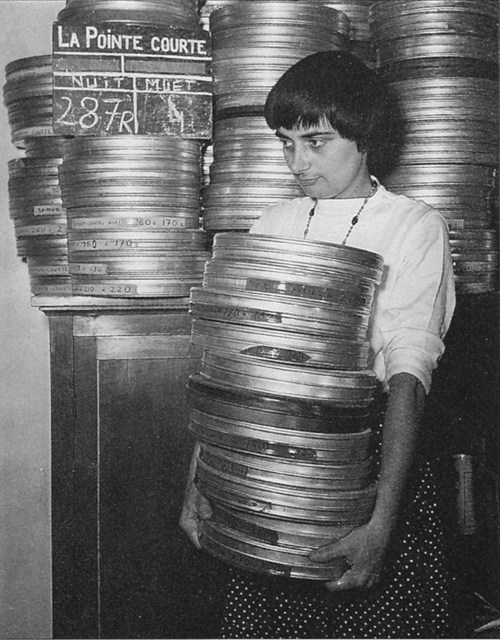

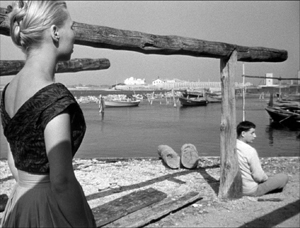

Sixty years ago, a twentysomething photographer released a film shot in an out-of-the-way French fishing village. Coming right after Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy and Fellini’s La Strada (both 1954), the result announced something new in cinema. Like those other works, it looked forward to the French Nouvelle Vague and the cinematic modernism of Antonioni, Bergman, and a host of other filmmakers.

But the status of Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte (1955) became apparent only with the most distant hindsight. It didn’t win big attention on the festival circuit, in the international market, or in the pages of highbrow film magazines. Denied a commercial release, La Pointe Courte circulated mostly in French ciné-clubs. In the early 1980s, when I saw it at the Brussels Cinematek, it was still a rarity.

Thirty years after La Pointe Courte, Varda’s career reached a new level. Vagabond (Sans toi ni loi, 1985), widely recognized as her masterpiece, remains one of the great achievements of that modern cinema she helped create. And she hasn’t exactly been idle since. There have been many films both long and short, including a biopic of her husband Jacques Demy in Jacquot de Nantes (1991) and the picaresque The Gleaners and I (2000); the fascinating autobiography Varda par Agnès (1994); and over the last decade a series of installations in museums around the world. She started as a photographer, became a cinéaste, and is now a plasticienne, a maker of painting and sculpture.

She is eighty-seven years old.

Agnès V., not B.

Our colleague Kelley Conway has just published an authoritative consideration of the work of this shrewd, unpredictable survivor. Reading Kelley’s book reminded me of that encounter with La Pointe Courte.

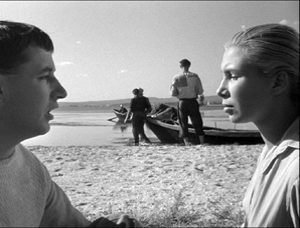

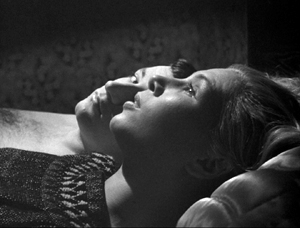

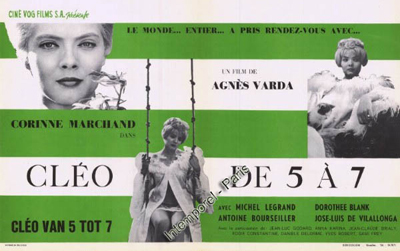

I had known Varda’s more famous works: Cléo from 5 to 7 (1961), screened at my college film society as the project of a New-Wave fellow-traveler; Le Bonheur (1965), which might be called Jules et Jim revisé et corrigé; One Sings the Other Doesn’t (1977), which got circulation among other feminist films of the period. These didn’t prepare me for La Pointe Courte’s daring mix of realism and minimalism. Varda wanted, she said, to make a film that was the equivalent of a difficult book, and for me she succeeded.

The film alternates sunny images of local life—fishing, net-mending, washing-up, a festival—with episodes in which a Parisian couple drift through the village, oddly detached from the life around them. The everyday scenes are shot in documentary style, but with a casual rigor suggesting Cartier-Bresson. Meanwhile, the couple talk in stylized compositions that could only remind me of L’Avventura.

No wonder Picasso was Varda’s favorite painter: she splits up the couple’s faces with cubistic zeal.

The disjunction between the actuality of a location and the abstraction of the couple’s anomie-riddled duet, often heard only as voice-over commentary, looks forward to Hiroshima mon amour. (No wonder: Resnais edited the film.) I barely understood the French, but the film gripped me. It was of great historical interest, and it had its own stubborn vivacity. When Kristin and I planned the first edition of Film History: An Introduction (1994) I made sure it got in. In that year, forty years after it was made, La Pointe Courte was released on VHS.

Things change. Varda is now regarded as a living treasure of world cinema, preserved in excellent Criterion DVD editions, available for streaming on Hulu, and wrapped up in a vast cube, Tout(e) Varda (20 features, 16 shorts). Whatever she does in the future, we can at least take a long-distance measure of her accomplishments.

The dream of many writers on a single director is to cover it all: appreciative study of the films, background on how the films came to be, assessment of their immediate impact and long-range influence. But this breadth of understanding is very hard to achieve. Where are the documents? How do you get the filmmaker to talk?

Kelley has done it. Her book combines film analysis, historical research, and information drawn from Varda’s archives. Kelley can tell us how the films came to be, what Varda wanted to accomplish, and how they were received. To top it off, there’s a new interview with Agnès herself.

Crossing landscapes

Les Demoiselles ont eu 25 ans (1993): Varda and Deneuve.

With a brisk practicality echoing that of her subject, Kelley has focused her lens tightly. You can’t quarrel with her choices: La Pointe Courte, the early short documentaries, Cléo, Vagabond, The Gleaners, two installations, and The Beaches of Agnès (2008). Her plan of attack is straightforward: scrutinize the film, then work backward to the conditions of production and forward to the film’s reception.The analyses are models of attention to story and style, images and sounds. Kelley pins down what intrigued me about the acting in La Pointe Courte, showing its debt to Brechtian distancing (a big influence on Varda). She goes on to connect the performances to the experiments in “flat” performance we find in Tati and Bresson at the same period. Kelley shows how many of Varda’s artistic strategies, such as whimsical puns and a love of digression, go back to her early documentaries.

In a sense, Varda has never ceased to be a documentarist, since all her films depend on a process of research, exploration, and a personal viewpoint characteristic of the roving photographer. The book includes fresh information on two of Varda’s major multimedia installations, obviously born of her interest in found materials, gags, and unexpected juxtapositions. For one, Varda covered the gallery floor with 1500 pounds of potatoes and played the role of “Lady Potato.” Another exhibition included a reference to the grave of her beloved cat Zgougou. As described by Kelley, these installations are less narcissistic than they might seem, because Varda’s work has always been personal, derived from her perceptions of her subject. Even The Gleaners, which is at one level a denunciation of a society built on waste and inequality, is refracted through the filmmaker’s sense of aging. And though Mona in Vagabond is ferociously solitary, we meet her through Varda’s welcoming voice-over: “It seems to me she came from the sea.”

In a sense, Varda has never ceased to be a documentarist, since all her films depend on a process of research, exploration, and a personal viewpoint characteristic of the roving photographer. The book includes fresh information on two of Varda’s major multimedia installations, obviously born of her interest in found materials, gags, and unexpected juxtapositions. For one, Varda covered the gallery floor with 1500 pounds of potatoes and played the role of “Lady Potato.” Another exhibition included a reference to the grave of her beloved cat Zgougou. As described by Kelley, these installations are less narcissistic than they might seem, because Varda’s work has always been personal, derived from her perceptions of her subject. Even The Gleaners, which is at one level a denunciation of a society built on waste and inequality, is refracted through the filmmaker’s sense of aging. And though Mona in Vagabond is ferociously solitary, we meet her through Varda’s welcoming voice-over: “It seems to me she came from the sea.”

Another legacy of documentary: Kelley points up how even the fiction films spring from an attention to the specifics of a locale. “Part of Varda’s journey is regularly exploring a chosen region at length, waiting for ideas, emotions, and images to emerge.” That region might be a single Parisian street (L’Opéra-Mouffe, 1958; Daguerréotypes, 1975) or the fourteenth arrondissement (Cleo from 5 to 7). Like La Pointe Courte, Cleo is the story of a walk, this time purportedly played out in actual duration as a beautiful pop singer awaits the results of a test for cancer. Mona, in Vagabond, is another wanderer, and the wintry bleakness of southern France is as central to the action as whatever psychology we can find in her or the people she meets. The Gleaners and I searches out people who stalk the landscape and live off what they can scavenge. With modern cinema from Bicycle Thieves onward, Dwight Macdonald once noted, “The talkies have become the walkies,” but Varda has always embedded her footloose protagonists in the particulars of place.

Varda’s personal archive has given Kelley the opportunity to document the director’s creative process. The scripts are sometimes scrapbooks, with texts and images jostling one another. (Kelley offers an example in a 2011 blog entry.) The arrival of digital tools reinforced and expanded Varda’s method of free assembly. Out of a database of images, Varda erected the scaffolding of The Beaches of Agnès before starting her screenplay. She wrote, shot, and edited the whole thing in a nonlinear fashion. During the final stages, two editors worked busily in separate rooms. “I went from one to the other. On one side was Sète and Los Angeles, in the other room was Belgium and Paris.”

As for exhibition, crucial to Varda’s early films was a distinctive French institution. Varda had created her company to make shorts, but when La Pointe Courte grew to 80 minutes, it could not be distributed under those auspices without new investment. As a result, it found its main audience in the network of ciné-clubs that had grown up after World War II. That network became activated to the maximum during the release of Cleo from 5 to 7. One of the side benefits of Kelley’s book is its explanation of the power that the ciné-club scene had achieved by the early 1960s.

Brandishing the slogan “Develop Film Taste, Introduce Masterpieces, Educate the Public,” an astonishing five hundred clubs with over two hundred thousand members showed thousands of films in the year that Cleo was released. Varda took advantage of this situation to promote her film, but Kelley goes beyond the simple marketing issue to point out that the clubs bolstered spectators’ appreciation of New Wave films. She draws on audience comments to show that the organizers guided audiences to talk about form, style, theme, and historical context. The clubs helped create the “demanding viewer” described by Alain Resnais: a viewer eager for challenging films that could bear comparison to advanced works in traditional arts.

Varda’s later films were absorbed into the mainstream commercial distribution/exhibition infrastructure, and Kelley is painstaking in plotting critical response to them. Near the book’s close, she traces how another institution shaped Varda’s work: the museum. Kelley shows how the emerging importance of installation art encouraged filmmakers like Varda and Chris Marker to create multimedia exhibits that were natural continuations of their poetic-essayistic documentaries. The installations seem to have encouraged Varda to take up the autobiographical compilation mode that yielded The Beaches of Agnès.

There is much more in Agnès Varda than I can summarize, but I hope I’ve piqued your interest. For any lover of Varda, Kelley’s book is a must, and even casual viewers will learn things that will drive them to the films. Reading it led me to think about how Varda’s lack of cinephile culture (she emphasizes that she knew nothing of film when she started) allowed her to respond to stories more directly than did the Bad Boys of the Cahiers, who saw everything through a mesh of hundreds of other movies. I was also prodded to think of her as quite an innovator in narrative. She has given us the parallel structure of La Pointe Courte, the fantastic science-fiction plot of Les Créatures, the isoceles love triangle of Le Bonheur, the dual-protagonist structure of One Sings, and the network narrative of Vagabond, with Mona as a circulating object a bit like Bresson’s Balthazar.

From the delightful interview with Lady Potato herself, I allow myself just one spoiler:

KC: You seem to start your projects with considerable preparation but you also have a flair for improvisation. Do you see it that way also?

AV: Yes and no. Or no and yes, depending.

An earlier entry discusses a Kelley talk on La Point Courte. I discuss some ambiguous narrative cues in Vagabond in my updated “Art Cinema” essay in Poetics of Cinema, 166-169.

This has been a good publishing year for our colleagues at Wisconsin–Madison. Lea Jacobs’ book on filmic rhythm came out last winter; go here for our observations.