Archive for the 'Directors: von Sternberg' Category

The ten best films of … 1932

Shanghai Express.

Kristin here–

The year draws to a close, and the internet abounds with lists by professional critics, educated fans, and clueless people proffering opinions on the ten best films of 2022. David and I avoid this custom, but fifteen years ago I stumbled into a habit of listing the ten best films of ninety years ago. Such films have by now stood the test of time, and they have one enormous advantage: no one is speculating about many Oscar nominations each will get.

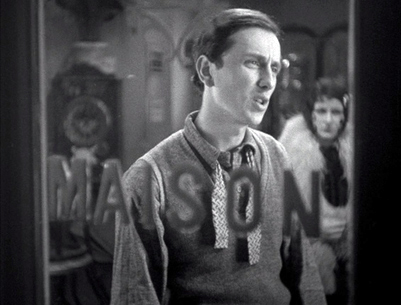

Back in the day, only two of the films on my list got nominated at all, and those two collected a total of three Oscars. (For a hint at one winner, see the image at the top. He will feature prominently in this year’s list.)

These ten films are of course my own choices, and for those who disagree, they are quite welcome to make their own lists.

As usual, my list is a mix of very familiar titles and some not so familiar ones. My hope is to call attention to unfamiliar films that are well worth a look. Actually this year nine of the films should be familiar to any serious film student or fan, but the tenth is a masterpiece that deserves to be rescued from obscurity.

Most historians seem to agree that 1932 was the year when Hollywood emerged from the difficult transition to sound and made polished movies that regained the fluidity of cinematography, staging, and editing that had been lost to some extent. In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, Janet Staiger, David, and I proposed that the transitional period lasted from 1928 to 1931.

The same was not internationally true, however. My list contains one silent film, since the Japanese industry went through a considerably longer transition. No wonder that half of this year’s list atypically consists of Hollywood movies.

Previous entries can be found here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928, 1929, 1930, and 1931.

As usual, I’ll try to point readers toward the best available Blu-rays or DVDs. Those who prefer streaming should be able to find these titles for themselves. David and I prefer discs, at least for important films. With the decline of access t0 35mm and 16mm prints, studying films closely has become more dependent on discs (which also still have better quality images than streaming). Eventually, with streaming the only option obtaining frame grabs of the sort that illustrate these entries, close film analysis will become extremely difficult.

Hooray for Hollywood!

Trouble in Paradise

Ernst Lubitsch is one of the best-loved of film directors, both within the film industry and among cinephiles. I was lucky enough to be invited to teach a one-month summer course at the University of Stockholm on any topic related to silent cinema. I jumped at the chance to follow up on a vaguely planned project on Lubitsch, specifically a comparison of his German and American silent films. The course became a book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, now out of print but available through open access.

Trouble in Paradise is widely considered his best film, though I would say that at least Lady Windermere’s Fan and The Shop around the Corner are equal to it and others are not far behind.

The witty script is a model of sophisticated humor, and the casting is perfect. Herbert Marshall for a change got to play the suave hero, a dazzlingly expert crook who teams up romantically with Miriam Hopkins, his match as a wily pickpocket. In this 82-minute film, their hilarious courtship in a Venice hotel runs for a remarkable 17 minutes as they top each other in stealing things from each other, with her returning his watch and his flaunting her garter:

It doesn’t seem a minute too long. Essence of Lubitsch.

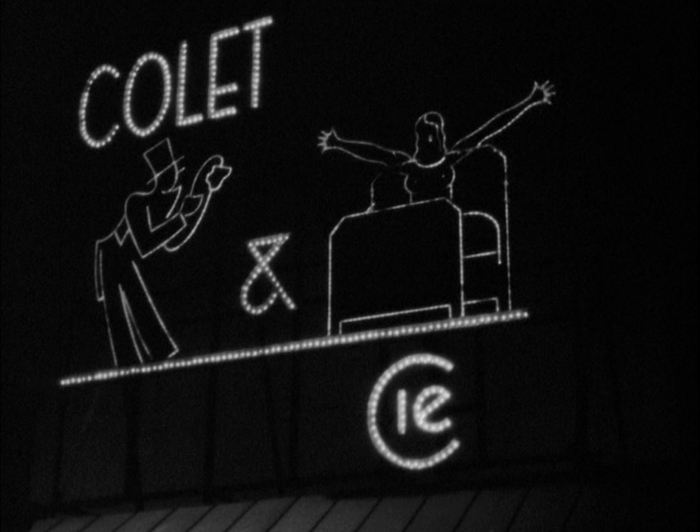

Kay Francis provides the potential trouble that threatens their idyllic life of thievery; she’s a beyond-wealthy owner of perfumery Colet & Cie. (see bottom)–so wealthy that she doesn’t really mind that her “secretary” may be a famous criminal worming his way into her confidence. Charles Ruggles and especially Edward Everett Horton provide hilarity as hopeless suitors wooing Madame Colet.

The comedy is played out in shining art-deco sets (above), lit with perfect three-point Hollywood lighting. As I demonstrate in my book, Lubitsch moved effortlessly from being the master of German silent film style to being the master of Hollywood style. It shows in every aspect of Trouble in Paradise.

The Criterion Collection DVD is still available.

Shanghai Express

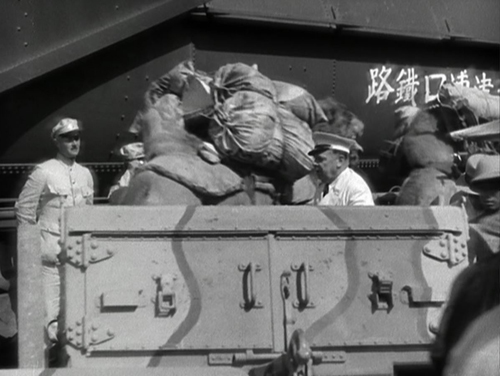

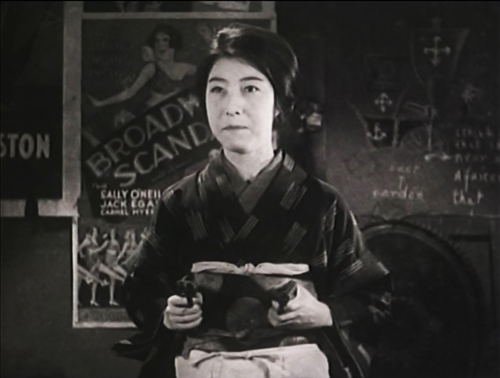

The Josef von Sternberg/Marlene Dietrich teaming. The Blue Angel, featured on my list in 1930. The pair famously made a series of Hollywood films together, all built around the glamor of Dietrich. For me, the best of the bunch is Shanghai Express. It has a stronger script than the others, being set on a train traveling from Beijing to Shanghai during the Chinese Civil War (which had started in 1927). The device of a group on a journey lends the film both unity and suspense. It’s basically a thriller with a romance included. There are more characters than in some of the other Dietrich films, the typical bunch of eccentrics for such journey-plots lending interest, humor, and pathos along the way. Dietrich’s character is strong and likeable. She pursues the man she loves, but on her own terms while he stands around cluelessly keeping his upper lip stiff.

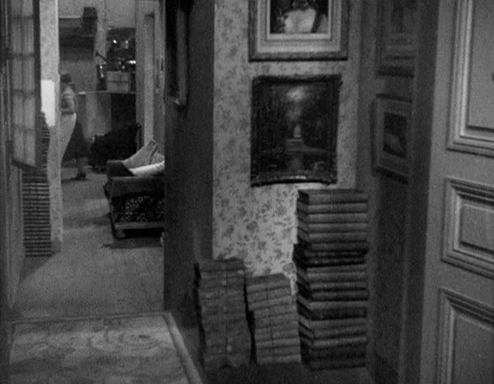

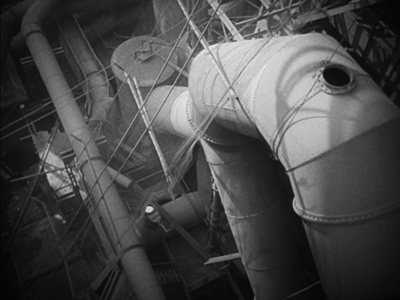

Then there are the incredible visuals. The set design is even more dense than usual for a von Sternberg film. The train windows, both exterior (top) and interior (above) are used brilliantly, and the rebel headquarters where the group is trapped for much of the second half has hanging gauze and stairways that create a complete contrast with the train scenes.

And the Oscar mentioned above went to … Lee Garmes, whose five films in 1932 also included Scarface (see below). Apart from his photography of the settings, he shows off with with other dazzling moments, including an extraordinary tracking shot following an official along the crowded platform for nearly the entire length of the train.

Needless to say, the glamor shots of Dietrich are among the most beautiful ever (Garmes also shot Morocco and Dishonored).

In general, the train station scenes are spectacular and give a remarkable sense of authenticity. Speaking of which, all the extras and minor characters seem to be played by Chinese, or at least Asian people. Anna May Wong has a prominent role as Hui Fei. Whether casting Warner Oland as the rebel leader Henry Chang would count today as “whitewashing” is up for debate. He was born in Sweden but claimed some Mongolian ancestry (so far unproven).

The Criterion Collection has the set of six Dietrich/von Sternberg films on Blu-ray and DVD. (My frames were pulled from an old TCM DVD pairing the film with Dishonored. TCM now offers Shanghai Express by itself on DVD or Blu-ray.)

A Farewell to Arms

The second Oscar-winner of the three mentioned above was Charles Lang, for his cinematography of A Farewell to Arms. (The film also won the third Oscar, for sound recording.)

Frank Borzage has been a staple of these ten-best lists, with Lazybones (1925), 7th Heaven (1927), and Lucky Star (1929). This may be his final appearance in these year-end lists, with growing competition internationally.

A Farewell to Arms adapts Hemingway’s novel of World War I. Gary Cooper plays Frederic, an ambulance medic who spends his spare time drinking and visiting brothels with his friend, Italian Dr. Rinaldi (Adophe Menjou). He meets Catherine, a nurse, at a party, and they fall immediately in love, succumbing to passion under the assumption that war’s uncertainties may not give them another chance. Becoming pregnant, Catherine departs for Switzerland to have the baby, but her letters to Frederic and his to her, are returned to sender. Frederic risks a firing squad by deserting and desperately trying to find her.

Like Trouble in Paradise and other 1932 films, A Farewell to Arms benefited from the fact that the self-censorship Hollywood studios instituted under the Production Code (aka the “Hays code”) in 1933 was not yet in force. The result is a grittier and more honest look at life in wartime than would be possible in later years. Apart from the quite restrained brothel scene (above), there is considerable emphasis on the forbidden unwed motherhood rife among the nurses Catherine works with.

The two stars make a convincing romantic couple of the kind Borzage had become famous for, and the cinematography is lovely. Lang, too, was an expert at creating glamorous images.

Amazon would very much like you to watch the film for free with ads or with a subscription to Paramount+ or with a free Fandor trial or by paying $2.99. Once you scroll past those enticements, you can find Kino Classics release of a Blu-ray or DVD in a remastered version by George Eastman House. It seems a bit overly dark to me, but maybe the original nitrate copy was, too.

Scarface

I have to admit that gangster films are not my favorites. Still, there are outstanding films in the genre, as the presence of von Sternberg’s Underworld on my 1927 list indicates. The early 1930s established the genre solidly, and Scarface stands out among the other classics examples of the time. I have not seen the two other such classics still commonly watched, Public Enemy or Little Caesar, for a very long time, but I recall not being very impressed.

Scarface marks Howard Hawks’s first appearance on one of my lists. It’s not up to his greatest films of the 1930s, Twentieth Century and Only Angels Have Wings (and some would say Bringing Up Baby).

One thing that makes Scarface stand out for me is its considerable use of humor, which seems unusual for a gangster film. Paul Muni, so dignified in his prestigious bio-pics of this same period, lets go and struts with aggressive arrogance, lets go in fits of rage, and makes Tony Camonte a figure of fun with his accent (“That’s putty nice”) and flaunted ignorance. When the woman he’s trying to impress and seduce remarks sarcastically that his clothes are gaudy, he delightedly takes it as a compliment.

The comic relief flirts with slapstick in the figure of Camonte’s “secretary,” who is illiterate, inept, and downright stupid. According to the AFI Catalog, his character name is Angelo, though Camonte addresses him as Dope. There’s a running gag of him being unable to get basic information from callers. At one point during a raging gunfight in a restaurant, he struggles to hear a caller’s name, unaware that a tank behind him has been pierced and is dousing him.

The film also has its visual pleasures. It was one of five films, along with Shanghai Express, that Lee Garmes lensed in 1932. The cinematography is appropriately less glamorous than in Shanghai Express, but it’s dark and occasionally beautiful, as in the hospital-invasion scene at the top of this section.

Many films of the early 1930s start off with an impressive moving-camera shot, presumably to show off before settling down into scenes with standard continuity cutting. Scarface has quite an impressive opening, with a plan sequence leading up to the first act of violence.

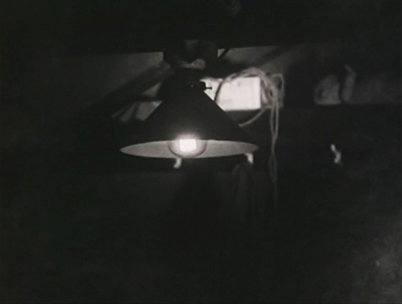

It begins with a low angle of a streetlight going out, and then tilts down and tracks rightward past a milk delivery cart and a sign that establishes the locale.

Continuing rightward, it reaches a tired janitor who removes a sign informing us that a stag party had been held there the night before. The camera tracks rights as he starts to clean up.

The camera follows through the wall and continues as he tackles the job in a room festooned with streamers–possibly an homage to the big party scene in Underworld. One artifact of the party that he finds is a brassiere that has lost its owner.

As he pauses, the camera leaves him to pan right and track in on a gang boss and two of his men talking about a potential danger from a rival gangster. He declares that he doesn’t want war and is satisfied with the money he’s making.

The men stand, and the boss promises an even bigger party in a week. Thus for a gangster, he seems a decent sort, not willing to stir up violence against those seeking to invade his territory.

The men leave, and the camera follows the boss across the room and into a phone booth. He starts to make a call.

The camera glides past him and away off to the right, where it picks up a menacing shadow in the next room.

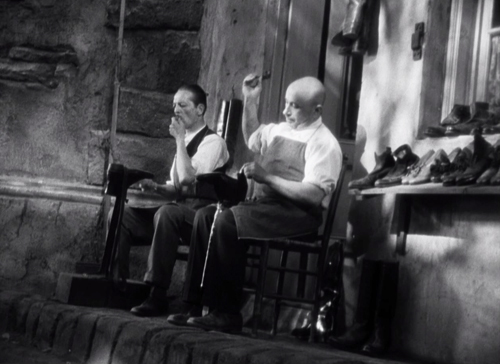

It follows the silhouette as the unknown man walks toward the corridor where the phone booth is. Silhouetted against a translucent window, he pulls a gun, fires it, polishes it with a handkerchief, and throws it on the floor. (This sort of offscreen or partially offscreen treatment allows the violence to be less explicit, a ploy that continues throughout the film.)

As the killer disappears, the camera tracks back to the left, revealing the boss’s body. The janitor enters, sees it, takes off his work clothes, and tosses them in the phone booth.

The scene ends with a pan left to follow the janitor as he hurriedly moves through the mess and leaves.

My frames were pulled from the Universal Cinema Classics DVD, a release which has since come out on Blu-ray. (Amazon still has the same edition on VHS!)

Love Me Tonight

So many of the early 1930s musicals were stagey. The review musicals were series of numbers without a connective narrative (convenient because they could be popular abroad without dubbing or subtitling) or backstage musicals where a “put on a show” premise also led to numbers on a stage. But with the growing freedom of the camera and editing, the musical could become something more.

Love Me Tonight feels like a wildly enthusiastic celebration of that new freedom. The story is a modern Ruritanian romance. A Parisian tailor, played by Maurice Chevalier, travels to a country chateau to collect money owed him by a client, who is a member of the aristocracy. While on his way, Maurice bumps into the debtor’s sister, Princess Jeanette, and falls in love with her without realizing who she is. Once at the chateau, he is mistaken for a Baron and proceeds to charm the Princess’ entire family and gain her love–until his lowly birth is discovered. Throughout, the dialogue is witty and the music and songs, by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart.

Much of the high spirits of the film arise from the fact that the songs are not sung by one or two people in a single locale. Instead, the music starts out in this limited way but passes along to other characters, spreading infectiously through a household or across a countryside. The process begins on a morning in Paris, as the city wakes up and goes to work. Gradually the rhythmic sounds of various activities build up to a symphony made of sound effects: a woman’s broom against a pavement or two cobblers’ hammers striking in counterpoint.

The first actual music when a man getting married that day picks up his formal outfit and Maurice sings about his work in “Isn’t It Romantic?” The groom goes out singing it, and it passes to a taxi-driver and then his fare–who happens to be a composer. Cut to a train, where he hums the music and writes it down (top of section), overheard by a group of soldiers; cut to a field where they march along singing it, and so on, until we reach the chateau and are introduced to the Princess, also bursting into “Isn’t It Romantic?”

Upon meeting Jeanette, Maurice woos her by singing “Mimi” to her. Here it’s a straightforward solo, though one that is filmed in an unusual fashion with Maurice singing and Jeanette reacting in shot/reverse shot directly into the camera.

Once at the chateau, Maurice apparently sings the infectious “Mimi” for the family and guests since there is a montage moving among them as they all cheerfully warble the song in their respective rooms. The same thing happens still later, when Maurice’s low birth is discovered; the song “The Son of a Gun Is Nothing but a Tailor,” similarly spreads throughout the building, including to the servants, who show a snobbery equal to that of their masters. Who can resist lyrics like those sung by a washerwoman?

Down upon my hand and knees/Washing out his BVDs/Is a job that hardly please me./If I had known I would have tore/The buttons off his panties for/The son of a gun is nothing but a tailor!

Overall one gets a sense that music and singing are irrepressible and ripple outward from the soloists to infect everyone within hearing distance.

Of course once Maurice has been thrown out, Jeanette decides to defy her family and races after his train on horseback. Mamoulian throws in some Soviet-style compositions as she heroically stands on the tracks and forces the train to stop.

Apart from its infectious style and music, Love Me Tonight has a wonderful cast, with Charles Butterworth as Jeanette’s wimpy but titled suitor, Charles Ruggles as the debtor son, Myna Loy as the man-hungry younger sister, and C. Aubrey Smith as the curmudgeonly father who becomes downright jolly under Maurice’s influence. Sheer entertainment.

Love Me Tonight is available from Kino Lorber on DVD or Blu-ray.

Hooray for the Rest of the World!

Vampyr

Two masters of cinema made vampire films a decade apart. I dealt with Murnau’s Nosferatu in the 1922 entry.

The two films could hardly be more different from each other. Murnau’s film was a plagiarized version of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, Dracula. He followed the original very loosely, cutting out most of the characters, including Van Helsing and hence the entire lengthy investigation process. Dreyer may well have known Murnau’s film, but it is hard to detect any influence or inspiration apart from the use of a book as exposition. The Universal version starring Bela Legosi was still in production when Dreyer finished shooting Vampyr. Instead, Dreyer drew even more loosely from the collection of horror-fantasy series short stories by Sheridan Le Fanu, published as In a Glass Darkly (1872).

Dreyer seems to have taken a few ideas from the stories, but does not use the narratives associated with those ideas. The notion of a female vampire is probably derived from one of the stories, “Carmilla,” though Le Fanu’s vampire is young and beautiful, while Dreyer’s is an elderly woman, Marguerite Chopin. The collection of stories is presented as having been case studies collected by a Dr. Hesselius, a researcher of the arcane. Allan Gray may be inspired by Hesselius, though he does no evident research and reacts in fear in most cases where he encounters anything strange and grotesque. Gray’s dream of being trapped in a coffin and carried off to be buried comes from “The Room in the Dragon Volant.”

On the whole, though, one of the most striking things about Vampyr is how little it adheres to the conventions of the vampire tale. It is not told as a collection of documents, as are Le Fanu’s stories (“Carmilla”is told in first person by Laura, the heroine and victim of the vampire) and Dracula (a collection of documentation by gathered by several characters). As in Nosferatu, a book is included to help present the “rules” of vampire stories, but the book is not written by Gray. It is given to him by the old Chatelain. The premises that vampires must travel in coffins full of dirt or will be killed if exposed to sunlight, so important in Nosferatu, are ignored here. Actually, the intention seems to be that Chopin is active mainly at night, but since the entire film was shot in murky daylight, it’s difficult to to tell night from day. Vampires also tend to be of noble birth, and we usually find out something about their family history. Chopin seems to be a local woman who somehow became a vampire.

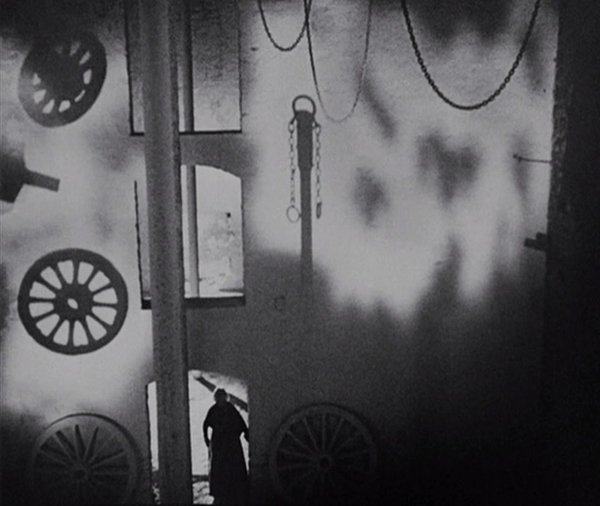

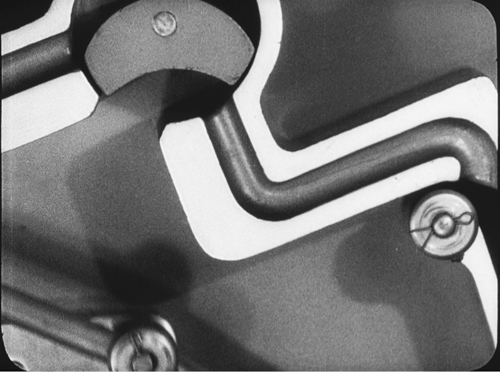

To create a creepy atmosphere, Dreyer has Gray wander about observing menacing, unnatural, or unexplained phenomena in the neighborhood of the village of Courtempierre. These are not phenomena conventional to vampire stories, so they seem as mysterious to us as to Gray. Much of what Gray observes is never explains. Gray sees numerous shadows and reflections of beings who are not visible. He follows the shadow of a peg-leg man until it finally rejoins the soldier who should be casting it. Most vampires live in crumbling Gothic castles, but Chopin seems to have made her headquarters in a dilapidated factory of some sort. (Dreyer chose a deserted plaster factory whose white walls would show off the shadows cast on them.) Her main minions, a sinister doctor and the one-legged military man apparently do whatever they do there, waiting to do her bidding. As the images above and on the right below show, Dreyer creates a mysterious air to the building through the circles and curves of large gears, wheels, and hanging chains.

Beyond such motifs, there are the actors’ unpredictable exits and entrances into the frame during camera movement and the eerie offscreen sounds that hint at something disturbing happening nearby. David has analyzed all this in detail in his book, The Films of Carl-Theodor Dreyer (out of print but available from second-hand book dealers).

For the ending, Dreyer draws upon the convention of a stake through the heart as the way to kill a vampire. It isn’t Gray that figures this out. A remarkably passive protagonist, he sits dreaming of being buried alive while the old servant, initially a minor character, reads the Chatelain’s book, gathers the needed equipment, and initiates the task of the staking of the vampire in her grave.

The 1998 restored version of the film is available from The Criterion Collection on DVD or Blu-ray, with a particularly good set of supplements. These include a visual essay by Danish expert Caspar Tybjerg that deals in more detail with the influences of previous vampire literature and films on Dreyer’s work; I have drawn upon it for some of the information above. Vampyr also streams on The Criterion Channel, accompanied by some of these supplements as well as a video essay by David, “Vampyr: The Genre Film as Experimental Film.”

Boudu Saved from Drowning

Jean Renoir entered this list in 1931 with La Chienne. Although a grim melodrama for the most part, the film provides put-upon accountant Maurice Legrand with a happy ending as he leaves home and becomes a jovial tramp.

Boudu, the self-centered, careless tramp at the center of this film, is presumably not Legrand, despite being played by the same actor, Michael Simon, and Boudu Saved from Drowning is not a sequel. It almost could be, but this time the genre is comedy.

The opening sets Boudu up as an unusual tramp. He is not begging, and when a little girl offers him a small bill, he asks what it is for. “To buy bread,” she replies. Soon Boudu does beg by opening a car door for a rich man, and when the man can’t find any money in his pockets to tip him, Boudu hands him the small bill “To buy bread” and walks away.

Unexpectedly, Boudu jumps into the river in a suicide attempt. Lestingois, a prosperous bookseller whose shop and apartment are across the street, witnesses this and rushes out to dive in and save Boudu. He succeeds, receiving praise from the onlookers as a bourgeois who would take this trouble for a mere tramp. Lestingois is fascinated and amused by this “perfect tramp” and takes him in, offering him dry clothes, food, and a sofa to sleep on for the night, much to the disgust of his wife.

Boudu’s antics delight Lestingois, who treats him somewhat like a pet dog (top of section). He also gives Boudu a lottery ticket, which predictably will become a vital plot device later on. The tramp, however, disrupts the routine of the household–in particular sleeping in a spot that prevents Lestingois from making his nightly visits to the maid Anne-Marie.

Boudu lingers on, seeing this cushy home as a good setup; he tries to fit in by shaving his bushy beard and trying to dress respectably. He is utterly uncouth, however, shining his shoes on the wife’s bedspread, and knocking things off shelves, and causing a flood by leaving water running in the kitchen. Lestingois ultimately gets fed up with him–but in the nick of time Boudu wins the lottery and the attitude of the household changes. Anne-Marie, who supposedly loves Lestingois, suddenly becomes engaged to him.

On the wedding day, however, as the happy couple are in a rowboat on the river, Boudu upsets the boat and floats away to resume his old life as a tramp.

Stylistically the film is distinctly Renoirian. He shot his exteriors in Paris streets and parks, seemingly concealing the camera in some cases. A telephoto lens captures Boudu wandering along the bookstalls on the banks of the Seine, with the other people presumably ignoring him as a real tramp.

In a modest way, Renoir used the sort of roving camera movement that he would later develop into a major feature his late-1930s masterpieces. One scene starts with Lestingois and his wife eating a meal along with Boudu, seen from a distance down a hallway. As Anne Marie finishes serving, she exits left, and the camera moves left into the next room, where she is glimpsed walking toward the kitchen. It continues moving and stops briefly as Anna Marie enters the kitchen and puts down her tray. As she comes forward to the kitchen window, the camera tracks closer to the foreground window and stops, still at a distance as she talks with an unseen neighbor.

Boudu Saved from Drowning is available on DVD from The Criterion Collection and streams on The Criterion Channel (along with some supplements).

Wooden Crosses

Raymond Bernard’s Wooden Crosses is this year’s masterpiece unknown to most modern viewers, and I cannot recommend it highly enough. I discovered the film through The Criterion Channel. David and I were relatively early in our “Observations on Film Art” series of supplements–early enough that the service was still called Filmstruck. In picking a film for a video essay, I thought it would be helpful to choose titles that were obscure but very much worth calling attention to.

One such film on the Criteron list was Wooden Crosses. I was dubious about it, since my only association with Bernard’s work was the 1924 historical epic, The Miracle of the Wolves, which I had seen back in my post-graduate days and found pretty turgid. Nevertheless, I gave Wooden Crosses a try and was bowled over by it. My video essay, “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses,” became number 16 and is available to subscribers.

In some ways Wooden Crosses is France’s great anti-war film of the early 1930s, following Hollywood’s All Quiet on the Western Front and Germany’s Westfront 1918, both of which were in my top ten for 1930. For me, it’s the best of the three.

The film begins with stock footage of Parisian crowds cheering the young men signing up to fight and marching off to war. Like The Big Parade, it introduces the war from well behind the lines, as new recruits arrive at a farmyard where the more experienced troops are billeted. The action takes place shortly after the Battle of the Marne in autumn of 1914; it was won by the French, but did not succeed in achieving ultimate victory. In Wooden Crosses, the experienced men scoff at the recruits for having arrived too late to experience any fighting.

Their optimistic assessment proves wrong, and the group is ordered to march to the front-line trenches. The result is an impressive sequence shot at night as the group goes through open areas, woods, and finally ends neck-deep in the trenches looking out across no man’s land in the darkness. As my video-essay title suggests, there is a considerable amount of night footage in the film. One point I make in that essay is that the epic footage in the film made an impression in Hollywood:

In 1935, the head of the newly merged 20th Century-Fox studio, Darryl Zanuck, bought the North American rights for Bernard’s film. He didn’t intend to release it theatrically. Instead, he realized that the spectacular battle footage was beyond anything that the studio could afford, and he wanted to reuse it.

The film it was to be used in was Howard Hawks’s The Road to Glory, released in 1936. Hawks, however, wasn’t just keen to use the battle footage. Like me, he seems to have admired the many night scenes. He said of Wooden Crosses that it had “Some fabulous film in it, marvelous scenes of great masses of people moving up to the front and through trenches—wonderful night stuff.”

The group of soldiers are quickly and marvelously characterized, notably by Charles Vanel as the group’s quiet, sensible Corporal and Gabriel Gabrio (Javert in Bernard’s Les Misérables) as the sarcastic, boastful Sulphart–a key source of comic relief in the film. Graduallynew volunteer Gilbert Demachy emerges as our main point-of-view character, though the others are kept prominent. There is a suspenseful series of scenes as they hear the sounds of German sappers tunneling below their dugout to lay mines. They are ordered to stay put, as there is plenty of time before the explosions, but as we discover, this is an example of a common motif in these films: the incompetence of the leadership.

One of the film’s most impressive aspects is the epic recreation of battle scenes. There’s no stock footage here, and there are shots over vast areas of no man’s land with explosions going off among the actors.

The climactic battle goes on and on–ten days, as repeated superimposed titles inform us–and conveys the relentlessness of the struggle that the group undergoes.

The battle ends in a long, tense scene, ironically set in a cemetery where many of the graves have been blasted open. These substitute for trenches as the men hunker down under German attack.

As with some of the other films on this year’s list, the cinematography of Wooden Crosses is extraordinary. It was shot by Jules Kruger, who had worked with major French Impressionist directors, notably Marcel L’Herbier on L’Argent and Abel Gance’s Napoléon, the latter of which no doubt gave him considerable experience with epic battle scenes. His most famous films after Wooden Crosses were La belle équipe and Pépé le Moko.

The Criterion Collection did a great service by releasing Wooden Crosses paired with Bernard’s Les Misérables in their Eclipse series. It also streams permanently on The Criterion Channel along with my video essay linked above. (New Year’s resolution: watch more Bernard films. I should give The Miracle of the Wolves another chance and set aside plenty of time to watch Les Misérables, a three-feature serial adaptation of the novel that clocks in at 281 minutes.)

I Was Born, But …

Yasujiro Ozu makes his third appearance in a row on these lists (see here and here for the first two). If I were to live to 102 and if I were still posting these lists, his last film would be on the 2052 list. That’s unlikely, but even so, he will probably be the director most represented on these lists as long as this series continues. I am still pondering whether to give him three spots on the 2023 list or just group his three masterpieces from that year as tied for a single spot.

I Was Born, But … was the first of Ozu’s silent films to become available in the West, and it is still probably the best known. So many of his early films are lost, but this may be the one where he achieved the perfect balance of humor and poignancy that characterizes so many of his best films.

Ozu is known for creating stories centered around the stages of life, often expressed as seasons in their titles, such as Late Spring‘s focusing on a daughter pushing the limits of marriageable age to care for her elderly father. His surviving early films often dealt with students or recent graduates struggling as “salarymen” in the job market of the Depression. In this film for the first time he shows the woes of the salaryman largely from the viewpoint of his children. Many of Ozu’s films are based on relations between parents and children young or grown. Those that dealt with young children were among his masterpieces: Passing Fancy, The Only Son, There Was a Father, Record of a Tenement Gentleman, and Ohayu.

The salaryman films deal with the difficulties of getting jobs, competing with colleagues, and surviving on meager wages. I Was Born, But … adds the problem of the subservience and even humiliation a salaryman sometimes undergoes and how it affects his family.

The story unfolds in parts that to some extent echo each other. Early in the film the two sons are bullied at school by the son of their father’s boss. They manage to defeat the bully and in a show of bravado boast that their father is the best in the world.

Later the family is invited to a gathering at the home of Yoshii’s boss, who shows some home movies of his employees showing off for the camera. These include Yoshii making faces and playing the fool, obviously at his boss’s insistence. The sons’ delight in seeing their father on the screen fades as they realize that their father has been humiliated and is not the great man they boasted about. Implicitly, Yoshii is being bullied as well but must submit in order to please his boss.

In an angry confrontation with their father, the sons accuse him of having proved himself not to be the man they had looked up to. The confrontation ends in their refusal to eat or speak to their parents. The parents admit to each other that their life is disappointing and not one they would wish for their children. The quarrel soon ends, with the boys accepting that their father is not the greatest.

As with That Night’s Wife (1930), Ozu is already using some of the techniques that would be part of his style for his entire career. For example, there is a transition between scenes that uses graphic values and objects in a series of images that do not behave like ordinary establishing shots.

I Was Born, But … is available in another DVD set in The Criterion Collection’s Eclipse series, “Silent Ozu: Three Family Comedies.” The other two are the charming Tokyo Chorus and the wonderful Passing Fancy (which will definitely appear on next year’s top ten). Along with a slew of other Ozu films, it also streams on The Channel. Many of you know David’s book, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema; it’s long out of print but available through open access on the Center for Japanese Studies Publications site (with the frames from the color films in color!).

Kuhle Wampe or Who Owns the World?

Slatan Dudow’s Kuhle Wampe, scripted by Bertolt Brecht, was a bold pro-Communist film made in the year before the Nazis swept into power.

Kuhle Wampe, named for the workers’ camp in which much of it is set, starts with the dire situation for the working class in Depression Germany. A typical family is singled out, with the son returning home after one of many fruitless searches for work (below). His parents blame him for his failure to find work in a society where unemployment is rampant. Their anger drives him to suicide. A neighbor woman remarks resignedly to the camera, “One fewer unemployed.”

The boy’s sister Anni becomes one of the main characters. Another is Fritz, her boyfriend, a leader in the labor protests in a local factory. When Anni becomes pregnant, the pair split up but eventually reunite when her family is evicted and moves into the tent city of the title, run by a Communist group (above). Communism is portrayed as a solution to the problems presented earlier. A lengthy sequence at a Communist youth sports festival emphasizes the happy life on offer by the Party. In the final scene, directed by Brecht himself, Anni and Fritz have an argument about the world’s financial dilemma with some middle-class passengers.

In 1933, Brecht fled the country, eventually ending up in Hollywood, and Dudow was expelled from Germany, only returning after the war to help found the Communist-run East German film industry.

As far as I can tell, the only DVDs or Blu-ray discs available in the US are imports and may not play on encoded machines. (It’s not even on YouTube!) For those with region-free players, the BFI’s release in either format seems to be best source.

Trouble in Paradise.

Dietrich before von Sternberg and von Sternberg before Dietrich

Thunderbolt (1929)

Kristin here–

In my entry on the ten best films of 1929, I suggested that that particular year, hovering as it did between silents and talkies, was relatively poorly represented on home video. Now Kino Lorber has released two films from that year that both entertain us and contribute to our knowledge of the late 1920s cinema.

In that entry I lamented the fact that Josef von Sternberg’s marvelous early talkie Thunderbolt had not had a proper DVD or Blu-ray released. I expressed hope that one of the home-video companies specializing in historically important classics would finally make it available. The Kino Lorber release finally allows historians and cinephiles access to this little-known masterpiece.

If Thunderbolt was a legendary film that called out for such a release, the 2012 Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung restoration of Kurt Bernhardt’s The Woman One Longs for reveals this previously forgotten film to be, if not a masterpiece, a very good film. It’s also completely typical of a trend of the late 1920s that I have termed the International Style.

Coincidentally, von Sternberg and Dietrich, so closely connected in our minds, link the two releases. Thunderbolt was the director’s last film before beginning his series with Dietrich, and The Woman One Longs for was Dietrich’s last (and first) starring roll before she worked with von Sternberg for the first time.

I’ll deal with it first, since I don’t want it to be overshadowed by Thunderbolt.

The Woman One Longs for

The standard story has Marlene Dietrich claiming that The Blue Angel was her first film. Seemingly she wanted to suggest that von Sternberg’s use of her in a series of star vehicles created her career. The image above, of her staring through a frosty train window, might easily be mistaken for a von Sternberg shot. In fact it’s from her previous film, The Woman One Longs for (Die Frau, das der man sich sehnt, aka The Three Lovers), directed by Bernhardt.

The Jewish director barely made his escape from the Nazis, working during the 1930s in France and then shifting to Hollywood. There, under the name Curtis Bernhardt, he made many films up to the 1960s, perhaps most notably the Joan Crawford psychological drama Possessed (1947) and the Rita Hayworth vehicle Miss Sadie Thompson (1953). That was an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s “Miss Thompson” (previously filmed by Raoul Walsh as Sadie Thompson, starring Gloria Swanson, in 1927 and by Lewis Milestone as Rain [a new title that had replaced the original name of the short story], starring Joan Crawford).

The plot of The Woman One Longs for is straightforward melodrama. The protagonist, Leblanc, is expected to rescue his family’s factory, tottering on the brink of bankruptcy, by marrying a wealthy heiress who loves him but who leaves him cold. He marries her, but on their honeymoon trip aboard a train to the south of France, he suddenly becomes fascinated by a mysterious beauty, played by Dietrich. She seemed to be under the sadistic control of Dr. Karoff. The latter is played by the great actor of the Expressionist theater, Fritz Kortner, familiar to most modern spectators as Dr. Schön, who keeps Lulu as his mistress in Pandora’s Box (also 1929). Leblanc becomes obsessed with saving Dietrich from her captor.

The plot is entertaining enough, but the real interest in the film, at least for David and me, is Bernhardt’s direction. It’s quite skillful, even flashy. Moreover, Bernhardt had clearly been seeing many of the major films of the 1920s from Germany, the USSR, and France. Like many other directors of the late 1920s, he blends them seamlessly into what I have called the “International Style.” (See Chapter 8 of Film History: An Introduction.)

The film starts in a setting done in a style familiar from many German films of the era, with a camera following a character through an atmospheric, faintly Expressionist street clearly built in a studio (below left). Even after the Expressionist movement ended in early 1927 with Metropolis, German films continued to use settings influenced by the style to represent old buildings or poor neighborhoods. Compare the opening shot of The Blue Angel (below right), the only Expressionistic setting in the whole film.

But Bernhardt has seen Soviet films as well. The early montage establishing the Leblance family’s factory uses the quick cutting, dramatic angles, and dissolves that such scenes have in so many Soviet and European films of the era (below left). A fight scene between Leblanc and Karoff uses fast editing, canted compositions, and camera reframing (below right).

Bernhardt has almost certainly seen L’Herbier’s L’Argent of 1928, with its streamlined sets (left) and low-angle framings shot with wide-angle lenses (right). Compare the latter with the low-camera-height shot of the Paris Bourse at the top of the L’Argent section in the 1928 entry linked immediately above.)

Bernhardt had also clearly seen Underworld, for the New Year’s party that forms the climactic scene of his film imitates von Sternberg’s party scene fairly obviously. The action centers around the two main male characters’ struggle over the heroine, with two count-downs raising the suspense: the beauty contest in Underworld and the approaching midnight signalling the new year in The Woman One Longs for. The hanging streamers that increasingly dominate the setting are, however, the giveaway for von Sternberg’s influence on Bernhardt (see bottom).

Speaking of influence, there is a moment in the party scene when the drunken Kaross pops a startled child’s balloon with a cigarette. Maybe this is a common trope in films, but the only other example I can think of is Bruno’s similar gesture of casual cruelty in Strangers on a Train.

The Woman One Longs for also contains a reference that we might today call an “Easter egg.” At the end, Karoff is arrested in the luxury hotel where the three main characters have been staying and where the New Year’s party take place. The manager insists that in order to avoid a scandal, the police must escort him out of the building via the “Hintertreppe” (backstairs). One of Kortner’s major roles had been the devious, obsessed postman in Leopold Jessner’s Hintertreppe (1921), one of the few other classics by which Kortner is known today.

Thunderbolt

I have already sung the praises of von Sternberg’s pre-Dietrich films on this blog. I find his naturalistic first feature, The Salvation Hunters (1925) heavy-handed, but with Underworld (1927) he abruptly hit his stride. To me it and The Docks of New York (1928) are his masterworks–those and Shanghai Express (1932), arguably the best of his Hollywood Dietrich films. The Last Command (1928) is excellent but not up to that level. I discussed these three when The Criterion Collection released them as a set in 2010. That set went out of print but is fortunately now available in Blu-ray. I put Underworld in my ten-best list for 1927 and The Docks of New York in the 1928 list. As I mentioned at the outset, Thunderbolt made the 1929 list.

There I briefly discussed the remarkable compositions and use of offscreen sound in the lengthy prison scenes of the title character on Death Row. Watching the new Blu-ray in preparing this entry, I was struck even more by the early scene in the Black Cat, a Black-run nightclub where we are introduced to Thunderbolt and his relationship to Ritzie, the heroine. As in the silents, von Sternberg’s habit of staging compositions with obstructing objects in the foreground is apparent. Note the entrance of Thunderbolt and Ritzie with a set element both framing and obstructing them (see top). Later a scene as two patrons of the club gossip about Thunderbolt partially blocks the faces, particularly of the one on the left.

The whole scene is marvelously enhanced, as I said in my 1929 entry, by the inclusion of Theresa Harris’ complete rendition of “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” It’s hard to think of another mainstream Hollywood film in which a Black cultural situation is used so naturally and with so much respect.

The Black Cat sequence ends with a police raid on the club. The cinematography at this point is pure film noir. (See image at the top of this section.)

As I said in the earlier entry, the one flaw in the film is the tepid central couple played by Richard Arlen and Fay Wray. Given the excellence of the Black Cat sequence and the lengthy prison scenes, that flaw is minor indeed.

The Woman One Longs for (1929)

A tantalizingly anonymous Josef von Sternberg film

Children of Divorce (1927)

Kristin here:

In 2008, David and I attended Il Cinema Ritrovato for the sixth time. The Hollywood director being featured that year was Josef von Sternberg. We saw some of the gorgeous prints on show, most notably (for me), a chance to re-watch the underrated Thunderbolt (1929), his first sound feature. To us the big auteur of the year, however, was Lev Kuleshov. Astonishingly, we only blogged from the festival once that year. It was a busy summer.

We and a great many other festival-goers lined up to see one of the rarer items on the program: Children of Divorce, credited to Frank Lloyd but with reportedly about half the footage re-shot anonymously by von Sternberg. We and a considerable number of those festival-goers did not get into the auditorium. For some reason this rare, legendary film was shown in the smallest venue, the Mastroianni, which was packed, with the two side aisles full of standees. (See the bottom image of our blog from the festival, as we caught a glimpse of those lucky enough to get in before retreating to find something else to watch or perhaps to wander around the always enticing Film Book Fair.)

Eight years later, in 2016, Flicker Alley released a Blu-ray/DVD combo of the Library of Congress’ 4K restoration of Children of Divorce. That two-disc set is out of print, but last month a MOD (manufacture-on-demand) version was made available. It is a single disc, Blu-ray only, and its main supplement is a pretty good one-hour documentary on Clara Bow produced in 1999 for TCM. (The original booklet is not included.) Somehow we missed the original release, but now I have a chance to catch up with this elusive film.

Naturally I wanted to find out if any information on which scenes of the film von Sternberg re-shot were available, I looked at various internet sources, including books in our library the reviews of the original 2016 Flicker Alley release and books. I found nothing on the subject, not even from film buffs speculating on the basis of style which scenes were his. I suppose one reason why so little discussion of von Sternberg’s contribution is that for many viewers and purchasers of the Flicker Alley discs, this a Clara Bow and Gary Cooper film. Those online reviews from 2016 focus on them rather than on the two very different directors of Children of Divorce. The third star, Esther Ralston is excellent as Jean, and in 1929 she would go on to play the title character in The Case of Lena Smith, Sternberg’s last silent film, which survives only in a fragment. Still, she doesn’t have the lingering reputation and devoted following that her co-stars still enjoy.

Spoilers ahead, including a revelation of the ending.

Von Sternberg’s account

In trying to discover von Sternberg’s contribution, we seem to be entirely dependent on von Sternberg’s sketchy recollections of his work on the film in his memoir, Fun in a Chinese Laundry (1965). Needless to say, one cannot take his account as the unvarnished truth, but it may contain some elements of that commodity.

According to von Sternberg, B. P. Schulberg, head of Paramount, asked him to watch a film that the studio considered unreleasable. Could von Sternberg could improve it by adding the sort of clever intertitles that he was then known for?

I looked at the film as he requested. Its title was Children of Divorce, and it had been made by a prominent director, Frank Lloyd, normally an effective director of commercial films. This one was a sad affair, containing theatricals by Gary Cooper and Clara Bow, the “It” girl of her day. I reported back to the executive who had backed this venture with a million dollars, and told him that no skill of mine could restore life to the film by injecting text into the mouths of the players. I suggested that half the film be remade.

That Lloyd should fall down so badly seems odd, given that he had been cranking out films at a rapid pace since 1915. These included films that would be considered star vehicles and adaptations of popular literature, such as the first version of The Sea Hawk in 1924. He would soon go on to win two early best-director Oscars, one for the Greta Garbo vehicle The Divine Woman (1928) and one for Cavalcade (1933), as well as being nominated for what is probably his best-known film, Mutiny on the Bounty (1935)–which won Best Picture despite not winning any other of its seven other nominated categories. Cavalcade often shows up on lists of the worst films ever to won the highest prize, but nevertheless, it seems odd that a director so respected within the industry that he won an Oscar for a film made the year following Children of Divorce‘s release should fall down so badly in creating the latter. We shall probably never know what cause this strange failure.

I must admit to never having seen a Frank Lloyd film, but von Sternberg’s assessment of him as an “effective director” seems lukewarm. It suggests that although Lloyd was a good, solid Hollywood practitioner, he had created an unwonted lemon.

In assessing the verity of von Sternberg’s account, we should pause over von Sternberg’s claim that Children of Divorce had had a million-dollar budget. That was well above the average cost of a film in those days. (Von Stroheim’s Foolish Wives, with its giant Monte-Carlo set, had gone over budget to become the first million-dollar film in 1922, and Universal head Carl Laemmle made the best of the situation by blazoning the extravagant budget in publicity for the film.) The original costs estimate sheet on Flicker Alley’s site, along with other documents from the film’s production, puts the total budget at $334,000–pre-re-shoots–a far more plausible sum. Possibly, writing in the wake of the scandal over the cost overruns leading to an estimated $44 million budge for Cleopatra (1963), he had to boost the paltry-sounding budget of a late-1920s feature at least to seven figures to show that he was doing an important favor for Schulberg.

In response to von Sternberg’s suggestion that half the film be remade, Schulberg (according to von Sternberg) said that he could not allot another five weeks to making changes in a project that still might flop. Von Sternberg writes, “I carelessly replied that I could remake half the film in three days and turn over a successful version to him.”

Schulberg asked, “What can I do about the sets? They’ve been torn down and the stages are full.”

Again according to von Sternberg, “I told him to have a tent erected for use as a stage and to dig out the sets from storage, and not to bother about anything else.” Schulberg agreed.

Von Sternberg’s entire account of the process of re-shooting the scenes runs as follows:

The tent went up and the transfusion began. A rainstorm came and lasted three days and three nights. We waded through the new scenes, now and then dodging a heavy burst of water that penetrated the canvas overhead. The crew that helped me and the poor actors that I mercilessly put through their new paces had to take a prolonged rest cure when I had finished with them. To match the scenes I wished to retain I had to use the style of the replaced director. The assignment was completed on time and, after removing the old scenes and replacing them with the new material, I showed the film to the flabbergasted executives.

This tells us discouragingly little. The weather and the cast’s exhaustion make for a dramatic tale but tell us nothing about the film itself. The only statement of interest is “To match the scenes I wished to retain I had to use the style of the replaced director.” Von Sternberg certainly knew the well-established norms of Hollywood filmmaking and if he deliberately set to blend his work into an existing film, his style could be difficult to detect. After all, we don’t know exactly what was wrong with the original version. Bad performances? Von Sternberg’s reference to “theatricals by Gary Cooper and Clara Bow” suggests that this may have been the case. Bad storytelling? Von Sternberg doesn’t mention whether he re-wrote any of the scenes he revised.

The new version premiered on April 2, 1927. Von Sternberg was not paid for his labors (he says), but he did prove himself as a director. Schulberg allowed him to direct an entire feature himself. Later that year, on August 20, his first silent masterpiece, Underworld, came out. This item in Variety of March, 1927, seems to confirm the basic claim of von Sternberg’s account. Several trade papers mentioned that Sternberg had re-shot some scenes, but none specifies which ones.

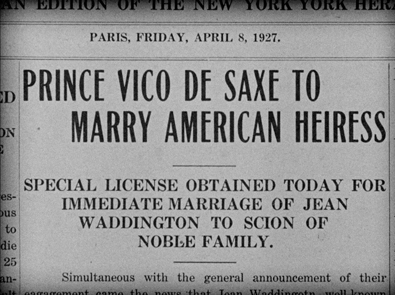

Briefly, Children of Divorce concerns two girls whose recently divorced parents have dumped them in a convenient French convent to be cared for. The parents return to the free life of single people, visiting their daughters infrequently. Kitty, a frightened, lonely girl, befriends the kindly Jean. Kitty introduces Jean to Teddy, an old neighbor of Kitty’s. Teddy and Jean hit it off and promise to marry as adults.

Kitty grows up and becomes Clara Bow. She is poor and must give up her love for the noble but impoverished Prince Ludovico (Einar Hansen) to pursue Teddy, now grown up to be Gary Cooper and very rich. His meeting with the grown-up Jean (Esther Ralston), herself now described as the richest woman in the USA, rekindles their love. Despite knowing this, Kitty uses the occasion of a drunken party to trick Teddy into marrying her, and they have a daughter.

Teddy wants to divorce Kitty and marry Jean, but insists that the daughter must not be as they were, a child of divorce. Kitty thinks this would free her to marry Ludo, but he informs her that his religion would not permit him to marry a divorced woman. She determines to hold onto Teddy. Jean decides to marry Ludo, thus quashing Teddy’s hopes of marrying her. Pure misery abounds–all the result, one way or another, of divorce.

What did von Sternberg do?

Naturally one would wish to know which scenes are Lloyd’s and which Sternberg’s. In her brief program notes for the film in the Bologna catalogue, Janet Bergstrom confidently comments, “You can’t miss the shadow language of his scenes.” Perhaps not, but there are actually very few Sternbergian shadowy shots in the film, and those are often brief touches. Here are the main examples. The second scene of the film shows the young Kitty (later to grow into Clara Bow) during her first night in the French convent where her newly divorced mother has dumped her (bottom). In another such atmospheric shot, Teddy reads Jean’s letter refusing to marry him if he divorces Kitty (top).

Other such shots occur occasionally. When Teddy and Kitty’s daughter totters winsomely down the stairs during a party, the elaborate railing casts a shadow over her. Jean’s first sight of her fixes her determination that for the sake of the child she will not agree to marry Teddy if he divorces Kitty.

These are the only shots that one could argue contained strongly Sternbergian shadows. The opening scene in the convent as Kitty’s mother leaves her has a shadow of an offscreen window on the wall at the center of the shot, but surely one could not be certain that an image directed by Lloyd could not have such a modest shadow simply to create the atmosphere of the setting.

Indeed, it seems like a typical shot from an A picture of the mid-1920s.

I do not think that one can determine which shots and scenes were redone by von Sternberg just by the lighting. “To match the scenes I wished to retain,” von Sternberg must have used the three-point lighting system that had been established as the norm during the second half of the 1910s. He did a very good job, and there are many scenes that look like they could have been shot by Lloyd or Sternberg, adhering to that same norm and of course using the same sets and costumes. Which of the two directors made this image, with its exemplary use of the three-point lighting system devised by Hollywood practitioners in the second half of the 1910s?

Von Sternberg’s reference to Lloyd as an “effective” director may sound like diplomatic, lukewarm praise, but he might have meant that any good Hollywood director with an experienced cinematographer could have produced such an image, with its perfect blend of key, fill, and back lighting.

Similarly, we might be tempted to identify this glamor shot of Ralston as directed by von Sternberg, but it seems a fairly conventional approach to filming a beautiful star in the late 1920s.

And here’s an impressive depth staging in the scene where Luco tells Kitty that he could never marry a divorced woman for religious reasons.

It is tempting to think that the stark juxtaposition of a sharply in-focus foreground cut off from the soft-focus background by the edge-lit fringes on the curtains is a von Sternbergian touch, but we cannot be certain that Lloyd and a good cinematographer could not create the same effect.

A possible, probable von Sternberg scene

The big climactic scene sure looks like a very skillful director made it. One is tempted to say that that director was von Sternberg.

The action brings to a head Kitty’s machinations. Having been rejected by Luco, she realizes that her refusal to let Teddy and Jean be together is making them miserable and is not the best thing for her daughter, either. She writes a suicide note addressed to Jean, hugs her daughter for the last time, and heads into her bedroom clutching a bottle of poison.

Here is a breakdown of the scene. It begins with Kitty reading a newspaper. We see her point-of-view, revealing that Luco is going to marry Jean. Luco has already rejected her, but this scene is the moment when she learns that he is to marry her friend. The newspaper shot is followed by a closer view of Kitty.

She looks up and to her right, her face grim. It is notable that Bow has been de-glamorized for this scene, with her eyebrows minimized and her hair swept back from her face in a matronly style quite different from her usual bouncy curls. The camera pulls in toward her until it is in extreme close-up.

The pull-in reveals a tear that has slid down from her right eye. It is worth pointing out that this is Clara Bow, noted for her flapper image, always lively and carefree. Clearly she could play drama and even melodrama. Perhaps this is an instance of von Sternberg’s famous ability to direct female performances.

The intense close view is interrupted by a cut to Kitty dropping the newspaper. A long shot follows as she stands and moves to sit down at the desk. A cut-in to a medium shot shows her thinking and beginning to write.

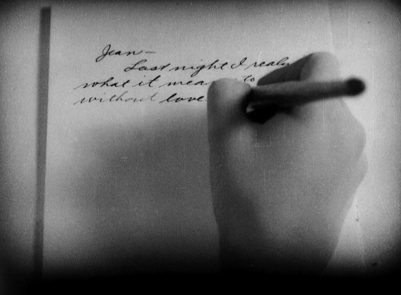

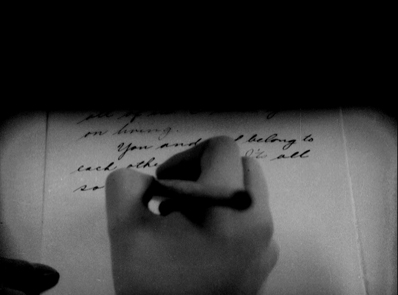

This leads to her point-of-view on what she writes. We learn only that it is a letter to Jean and that Kitty has had a realization. A return to the medium-shot framing shows her reacting to a knock at the offscreen door and saying, “Come in” as she hides the letter under the desk-blotter. An eyeline-match cut shows her daughter entering. A pan follows as she crosses to the desk and Kitty kneels to embrace her.

A cut-in shows Kitty emotionally embracing the girl. During the course of this, the girl’s hat falls off. In a return to the medium-long shot, Kitty carries the girl to her nurse. Another shot shows her returning to fetch the fallen hat and hugging it while displaying despair.

A more distant framing shows her putting the hat back on the child. The nurse’s cheery expression as she helps put the hat on contrasts greatly with Kitty’s unnoticed emotion. Once the others leave, Kitty returns to sit at the desk and pulls out the unfinished letter. Again we see her point-of-view as she completes the letter and we realize that it is an apology and suicide note, telling Jean to marry Teddy and raise the daughter that should have been hers. A return to the medium shot shows her putting the letter into an envelope.

A rather clumsy and unnecessary cut-in to a tighter shot of Kitty might suggest a blend of Lloyd and von Sternberg footage is occurring, but the lighting on the set, Kitty’s hair-do and costume are identical, so the footage is probably all from the same director. A return to the previous medium shot shows Kitty hesitating as she finishes addressing the envelope and presses a button to summon a servant. A cut back to a more distant shot shows her rising and starting rightward toward the door.

A cut to the doorway shows Kitty handing the envelope to a maid, who leaves. Kitty than moves away from the camera to reach for a small cabinet on a table. A cut-in with match-on-action shows her unlocking the cabinet and taking out an object barely recognizable as a small bottle.

A cut to the mirror above the cabinet shows Kitty looking at herself, with the image of her face going out of focus. A cut to a medium-long shot leads to the camera panning with Kitty as she moves to a door at the rear.

She opens the door and walks into the distance as the camera tracks slowly back.

That’s a pretty flashy scene, and it certainly seems more likely than not that von Sternberg directed it.

Once again Flicker Alley deserves credit for bringing us another important film from the silent era.

Thanks to our friends at Flicker Alley for facilitating this entry.

The ten best films of … 1930

The Blue Angel (1930)

Kristin here:

The end of this horrendous year is fast approaching, though we are still facing a long struggle to end the pandemic. On a happier note, it is also time for a little distraction in the form of my annual year-end round-up of the ten best films of ninety years ago. 1930 was also a grim year, with the Depression well established and nowhere close to its end. Herbert Hoover decided not to use federal governmental powers to help end the crisis (sound familiar?) and eventually was cashiered into a 32-year retirement, though he continued to oppose Roosevelt’s policies. At least we don’t face that long a stretch of down time with the current “president.”

I discovered that 1930 did not produce many masterpieces. There are some obvious titles on my final list, as always, but some of the films are good but not great. In any other year they would not have made the cut. (The contrast with 1927, for example, is pretty stark.) Presumably one major reason is that filmmakers were still struggling with the introduction of sound. Fritz Lang didn’t release a film that year, though he came roaring back with M in 1931, as assured a treatment of sound cinema as one could find during those early days. (For those of you who subscribe to The Criterion Channel, I contributed a video essay on sound in M to David’s, Jeff Smith’s, and my series, also called “Observations on Film Art.”) Eisenstein was off in Hollywood unsuccessfully trying to make a film for Paramount and about to fall in love with Mexico. With one notable exception, Hollywood’s important auteurs made no films or minor films or films that don’t survive.

This dearth of really great films will be short-lived. From 1932 on, I shall no doubt have the opposite problem. For now, here are my picks. All the films are worth seeing, though good copies or even any copies of some are hard to track down. (The idea that all films are available to stream online is as absurd as when, back in 2007 when I wrote “The Celestial Multiplex.”) Some of my illustrations in this entry are subpar, but 1930 does not seem to be a year that studios and home-video companies are mining for titles to restore. I hope this entry will give them a few ideas.

I try not to include more than one film by the same director in these entries, aiming for variety and coverage. This year’s most prolific great directors were Josef von Sternberg and Yasujiro Ozu, who together could have filled in half the ten slots, but I have stuck to my guideline. (When we reach 1932 and 1933, I may be tempted to make an exception for Ozu.)

Given that sound developed at a different pace in different countries, some of this year’s films are silent.

For previous 90-year-ago lists, see 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, 1928 and 1929.

Dovzhenko’s Earth

Some of the films on my top-ten list this year may raise eyebrows, but Earth is probably my least controversial choice. It remains one of the last classics of the Soviet Montage movement.

The policy of merging small farms into collective ones had begun in 1927 as part of the First Five-Year Plan. In 1929-30, the push increased, with the seizure of the assets of the more prosperous peasants who resisted collectivization, termed kulaks. Major films were made with the aim of villainizing the kulaks and emphasizing the backbreaking labor involved in traditional, non-mechanized farming. Eager young peasants were hailed as heroes, and tractors appeared as the means to greatly increase wheat yields–wheat which was often seized and sent to the cities to enable rapid industrialization.

Eisenstein had promoted collectivization with his Old and New in 1929, and Dovzhenko followed a year later with Earth. While Eisenstein’s approach had been sarcastic and comic, Dovzhenko pursued his poetic approach to cinema. The opening celebrates the fecundity of the earth and the cycles of nature. The famous opening juxtaposes a peasant girl’s face with a large sunflower. Semion, an aged peasant, is calmly, even cheerfully awaiting his imminent death, lying on a blanket and surrounded by heaps of apples.

A kulak family is soon introduced, angry at the idea that their possessions will be seized. The head of the family declares that he will kill his animals rather than turn them over, and he tries to attack his horse with an axe.

The arrival of the village’s new government-provided tractor marks a shift to an emphasis on the advantages of collective farming. As it approaches, the kulaks stand watching and mocking the idea of a machine taking over. In one shot, an elderly kulak stands framed against the sky, his wealth indicated by the presence of a hefty cow. The tractor temporarily halts, but it turns out that the radiator is dry. The simple solution is for the collective members to urinate into it.

Earth is a visually beautiful film, but like other Soviet classics I have complained about, there is no decent print of it available. The old Kino disc groups it with Pudovkin’s The End of St. Petersburg (the cropping of which I mentiooned in the 1927 entry) and Chess Fever. The copy of Earth is too dark and indistinct. To get some frames for illustrations, I watched the visually superior copy on YouTube, but there the images are cropped to a widescreen format. Just as bad, there are ads scattered through it, including one in the middle of Vasyl’s twilight dance in the road just before he is shot!

As before, I must end by pointing out that an archival restoration and a Blu-ray release are in order.

Ozu debuts on the list

Although after 1937 there are years when Ozu did not make a film, he will likely feature on these lists as long as I continue to post them. In 1930 he made six features and a short. Only three survive: Walk Cheerfully, I Flunked, But … , and That Night’s Wife. I’ve chosen the last, though Walk Cheerfully is a viable candidate as well. Sound was adopted slowly in Japan, and Ozu held out until 1936 before releasing his first talkie, The Only Son, which will doubtless feature on my list for that year.

The British Film Institute released That Night’s Wife in a boxed set called “The Gangster Films,” along with Walk Cheerfully and Dragnet Girl. Yes, Ozu made gangster films, including the wonderful Dragnet Girl, the film that might lead me to make my exception in the 1933 entry.

That Night’s Wife, though, is not really a gangster film. Shuji, the father of a daughter with a potentially fatal illness, is not a gang member but a decent working man who stages a hold-up to get money for her medicine. Ozu handles this hoary plot premise with his usual unconventional approach.

The opening, with its shots of dark, empty streets through which the police chase Shuji, is film noir ahead of its time. We soon are introduced to his worried wife, Mayumi, tending the little girl. She’s cute but has a distinctly bratty streak so common to Ozu children. This and fairly frequent moments of subtle humor help Ozu avoid a purely melodramatic presentation of the situation.

Once Shuji arrives at home, Mayumi gets him to confess what he has done. He intends to turn himself in after the daughter’s crisis passes, but a gruff detective who has posed as a cabby to find out where he lives, appears. Being told that the daughter will only survive if she lasts through the night, the Detective agrees to stay and settles in to guard his prisoner. Mayumi reveals her inner toughness and determination to defend her husband. At one point the Detective dozes off and she steals his gun and points it and her husband’s pistol at him, urging Shuji to escape (above). That shot, by the way, shows a motif typical of early Ozu films: having posters, often for American movies, visible on the walls behind the characters.

That Night’s Wife doesn’t display the fully mature Ozu style, but no one would mistake it for a film by another director. He has already mastered the perfect match on action, and he uses one in the early scene where Mayumi sits down as the doctor tends the daughter. Ozu cuts in with a move across the axis of action that places us 180 degrees on the other side of her.

Ozu is not using 360-degree space consistently yet, but he’s playing with the idea. Twice he has transitions that move through a series of adjacent spaces, one of his key devices and one that will last throughout his career. Here we move from the worried Mayumi to Shuji, trying to elude the police after the theft.

There’s a lyrical motif mutating from shot to shot: worried wife, interior lamp, interior plant against wood, outdoor light with leaves, stone building with the shadows of leaves, and stone building with the subject of Mayumi’s thoughts, cowering. But causally the four “extra” shots tell us little about where Shuji is in relation to the home he seeks to reach.

I took these frames from the BFI set, but in the US Criterion released the same three films in its Eclipse brand under the more accurate title “Silent Ozu – Three Crime Dramas.” (I Flunked, But … is in the BFI’s four-film set, “The Student Comedies.” Criterion hasn’t released a DVD of it, but it is streaming on the Channel.)

The Germans’ sound advantage

Unlike other countries, Germany developed its own sound system, owned by the Tobis-Klangfilm company. Tobis was initially able to use court injunctions to keep American films out of the German market. In 1930, this pressure led ERPI and RCA, owners of patents on the major US sound-on-film systems, to form a cartel in conjunction with Tobis, which had producing and distribution subsidiaries throughout Europe. Tobis-Klangfilm continued to dominate European sound recording and reproduction until the beginning of World War II.

Partly as a result of this technical advantage, several early 1930s German films became classics, though not all of them are known abroad.

One internationally famous classic is The Blue Angel. I’ve mentioned that von Sternberg was among the most prolific of major directors in 1930. I debated whether to put this or Morocco on the list. If cinematography were the main criterion, Morocco would have been the choice. Not surprisingly, Lee Garmes’s camerawork and lighting is spectacularly good.

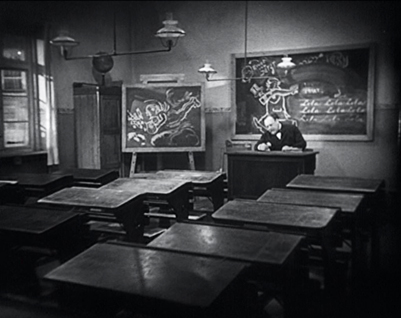

I initially saw The Blue Angel decades ago, in grad school. It was the usual hazy 16mm print of the American release version. Watching it again in the German version, remastered from a 35mm negative, was a revelation. Not that it will ever be one of my favorites. It has its problems. The motif of the clown, implied to be Lola’s degraded ex-lover, is heavy-handed. Emil Jannings’ lumbering performance as Prof. Rath is at odds with the casual realism of the other performances. The time-passing montage accomplished via a hair-curler ripping down a series of calendar pages creates a time gap of years passing and the characters–especially Lola–have changed radically. Her change from a kind attitude toward Rath to cruelty and indifference is logical, given his passive decline from professor to clown, but it is presented too abruptly. Still, in my opinion the film’s pluses outweigh its minuses.

The Blue Angel, seen in a good print, is wonderfully photographed as well (see top). It may not have Lee Garmes, but it has Günther Rittau (co-cinematographer with Hans Schneeberger). He had lensed Die Nibelungen, Metropolis, Heimkehr, and Asphalt. He brings a dark look to the film, as in these shots of Rath in dignified professor mode and later onstage in a caricature of his former self.

The camera movements are rare and unobtrusive. A visual motif set up early on shows the bustling classroom that Rath presides over, where despite the students’ dislike of him, they obey his strict commands. Later, in after Rath has visited The Blue Angel and met Lola, his blackboard is covered with caricatures and insults drawn there by the students to mock his obsession with Lola. A slow track back emphasizes the empty classroom as he sits at his desk, his authority over the students gone.

No doubt it’s a matter of taste, but I find Marlene Dietrich’s performance here more attractive than in Morocco–and it is, of course, central to the film’s appeal. Her amused playfulness with Rath, her quietly sarcastic attitude toward her sexuality being The Blue Angel’s main attraction, and her frequent bits of business with props unrelated to the story all differ considerably from her Hollywood performances. She has a natural glamor here that will disappear in her roles for von Sternberg in Hollywood.

After this film, von Sternberg made Dietrich a Hollywood symbol of glamor, but as a result she tends to be less spontaneous and active, with the camera and lighting lingering over her. Basically her glamor became more sultry. The result has its own appeal (and Shanghai Express is a good bet for a place on the 1932 list), but it is revealing to see her performing in a way that she only recaptured occasionally, if at all, in her subsequent films.

The frames were taken from the Kino on Video two-disc set, which has both the German and truncated American versions, as well as some supplements. It was subsequently released on Blu-ray, but I haven’t seen that version.

I always try to call attention to little-known films rather than sticking to the conventional classics for the whole list–and there aren’t a lot of such classics this year anyway. This time it’s a charming, imaginative musical romance, Die Drei von der Tankstelle, or “The Three from the Filling Station,” directed by Wilhelm Thiele and starring Lilian Harvey and Willy Fritsch. It was so popular that it outgrossed The Blue Angel in Germany.

Three carefree young men, who start off driving in a car and singing about friendship, arrive in their lavish shared home to discover that they are bankrupt. Low on gas, they are inspired to start their own filling station. They sing a nonsense song, “Kuckuck” (the German equivalent of “cuckoo”) as their belongings are hauled away, and they give this name to their art-deco filling station.

Lilian (the heroine’s name as well) shows up in search of gas for her roadster, and the three men fall in love with her. The rest of the film involves their competition over her. Naturally she chooses Willy (Fritsch’s character name). The two were often paired in later German films of the 1930s and became the ideal movie couple.

The film maintains its playful, often silly tone until the end. As Lilian and Willy are united before a closed theatrical curtain, she turns front and says, “People! The public!” There is an objection that this is not the way to end an operetta and the curtain opens to reveal the entire cast as well as additional dancers and singers performing a lively and somewhat chaotic grand-finale number.

I originally saw this film at the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique (now the Cinematek). As it does not circulate in the US on home-video, I have taken these low-quality frames from a homemade DVD, probably originally dubbed from an unsubtitled German VHS copy. It is available on a German DVD, since it is considered a perennial classic there. Unfortunately it has no subtitles. (The German manufacturers do not seem to have cottoned onto what their counterparts in other European nations–notably France–have: that if you include optional English subtitles, you can sell more copies.)

I hope, however, that eventually someone at the DVD/Blu-ray companies will discover this very entertaining film and make it more widely available.

A German director abroad

F. W. Murnau’s City Girl is another of those films I saw in a poor print decades ago and respect a great deal more after seeing it in a good version and knowing more about film than I did then. I wouldn’t put it in the same league as some of his earlier films, but for a 1930 list, it stands out.

Murnau was already on the way out at Fox when he was making the film. After his departure, the film was “finished,” including some dialogue scenes that were inserted. As with several other films of the era, such as Borzage’s Lucky Star and Duvivier’s Au Bonheur des Dames (see below), we are lucky in that only the silent version survives. The restored dialogue scenes in Fejos’s Lonesome show how ghastly these added interludes could be. (My apologies to the restorers. Obviously somebody had to do it.)