Archive for the 'Directors: von Sternberg' Category

The ten best films of … 1929

Lucky Star

Kristin here:

As 2019 fades away, it’s time once more to look back ninety years at some great classics. This series started somewhat by accident, when we wanted to celebrate the pivotal year 1917. That was when the stylistics of the Classical Hollywood filmmaking system, which had been slowly explored for several years, finally clicked into place and became the norm in the American studios.

After that, our series became a regular and surprisingly popular feature. The point is partly just to have some fun and partly to call attention to great films that have remained obscure and/or difficult to see.

For past entries, see: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, 1927, and 1928.

After the riches of the 1920s silent film, 1929 stands out as an anomalous year. The transition to sound was under way internationally, but different countries proceeded at different paces. The new technology often was not amenable to maintaining the freedom of cinematographic and editorial style achieved during the height of the silent cinema. There are arguably not as many indisputable masterpieces from this year as from previous ones–but there are some.

Oddly enough, truly major films from this year seem to have suffered a great deal from a lack of access, both in distribution of prints and release of good (or even any) copies on home-video formats. In part I want to draw attention to the shocking neglect of some great movies.

The list is dominated by Hollywood and especially the USSR, for opposite reasons. The American studios were well into sound production, and some of the top directors found tactics for using the new technique in imaginative ways.

In the USSR, on the other hand, silents reigned. Moreover, the great directors were not lured away to work in America, as so many European filmmakers were. (For example, Murnau’s career was nearly over, and he released no films in 1929.) Thanks to them, the golden age of silent cinema continued on.

A great year for the Soviet Montage movement

The General Line (aka Old and New, dir. Sergei Eisenstein)

The General Line is probably the least of Eisenstein’s four silent features. The earlier films were all set before or on the very day of the 1917 Soviet Revolution, and they all have a vigor and a sense of political fervor that The General Line can’t quite match. Instead, it’s about policy, specifically the portion of the First Five-Year Plan devoted to the collectivization of private farms. Eisenstein adopts an odd tactic for dramatizing the need for such a drastic overhaul of life in the countryside. He presents a single protagonist for the first time, Marfa, a poor peasant working her land alone and without a horse for the plowing.

She becomes convinced that the answer to her and her neighbors’ plight is to create a cooperative dairy for the village. But throughout, Marfa has few allies and encounters opposition from both the local wealthy Kulaks and the poor peasants, who are portrayed as ignorant, greedy, and even violent in their determination to retain full ownership of their farms and livestock. Marfa is too weak to succeed without the support of the local government agronomist and a few like-minded farmers. The task of collectivization seems too overwhelmingly difficult to ever succeed.

In retrospect, we know about the systematic exile and execution of the Kulak class and the famines that resulted from government tactics over the coming decade. It is unpleasant to see Eisenstein, however unwittingly, providing propaganda for Stalinist policies.

Still, Eisenstein is Eisenstein, and The General Line is as formally daring as his earlier work. Apart from dramatic angles and rapid, jarring cutting, he experiments with extreme contrasts of elements within the frame by using depth compositions. These exploit wide-angle lenses and create impressive deep-focus images. In the shot above, Marfa is dwarfed by a pampered bull in the near foreground, and in a third plane beyond her we see the grotesquely fat Kulak lolling in the sun on his porch.

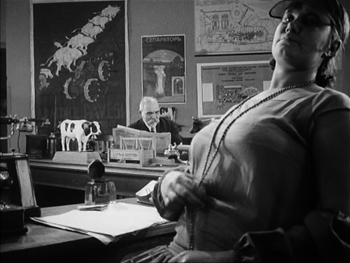

Other compositions create even greater contrasts. On the left, Eisenstein provides an image of bureaucratic indolence, official red-tape being a favorite (and apparently approved) satirical target for Soviet filmmakers. On the right frame, there’s a suggestion of the power of the collective’s new bull, who will sire a generation of calves.

Despite the grimness of the situation, Eisenstein manages to slip in an unusual amount of humor, and The General Line is quite entertaining.

The best DVD version I know of is the French one from Films sans frontiers, which is still available from Amazon France. The print in Flicker Alley’s “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film” is somewhat grayed out in comparison. Unfortunately this important set seems to be out of print. Flicker Alley rents The General Line online here.

New Babylon (dir. Grigori Kozintsev and Leonid Trauberg)

This masterpiece by Kozintsev and Trauberg is all too little known. Information on the internet tends to come more often from musicologists, since Dmitri Shostakovich wrote the original musical accompaniment, rather than from film scholars. Many viewers have heard recordings of the score but not seen the film itself.

Kozintsev and Trauberg were the leading members of the FEKS (“Factory of the Eccentric Actor”) filmmaking group, based in Leningrad rather than Moscow. As the name suggests, the practitioners aimed not at realism, but at the grotesque, the comic, and the appeal of popular rather than high art.

New Babylon deals with the Paris Commune of 1871, a brief period when workers took over the French government. It was seen as a forerunner of the Soviet Revolution.

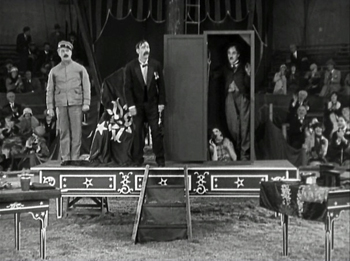

The title refers to a giant Parisian department store, which also seems to be in the business of putting on patriotic operettas about the current war with Germany. The store’s owner and patrons, as well as the performers in the operettas (see above) represent the bourgeoisie, while the workers who staff the store and create its products eventually rebel and run the doomed revolutionary government.

Again there is a heroine who represents the people, though she is unnamed, being known only as the shop assistant. She begins as a naive girl selling lacy clothing at the New Babylon and ends by becoming a militant revolutionary, standing atop a street barricade made up of the contents of the store–with the lace becoming bandages.

In keeping with its eccentric nature, the film mixes broad humor in the depiction of the bourgeoisie with grim tragedy as the defenders of the commune are shot in street fighting or tried and executed. The FEKS directors came from experimental theatre, but they also mastered the art of editing. New Babylon contains virtuoso sequences of crosscutting that sharpen the class struggle at the heart of the film.

New Babylon was restored in a joint venture by Dutch and German broadcasting channels and released, with the Shostakovich score, on DVD. There are Dutch and German versions, as Nieuw Babylon and Das neue Babylon respectively, which are out of print. We have the former. These retain the Russian intertitles, and, despite what the covers say, there are English and French optional subtitles as well as Dutch and German ones. (The booklet, however, is only in Dutch or German.) The quality is acceptable, but this film really needs a better restoration and Blu-ray release. It seems evident that the aspect ratio used in the current release crops the image to some extent.

Man with a Movie Camera (dir. Dziga Vertov)

I need say little about this film, since it has been widely seen, praised, and discussed. Back in the 1970s and 1980s, when many academic film scholars were obsessed with “self-reflexive,” or, less redundantly, “reflexive” films, Man with a Movie Camera was the great film. The result was, perhaps, that this admittedly very fine film was over-hyped. Nowadays it is as likely to be studied for the fact that Vertov’s wife, Elizaveta Svilova, created the very flashy Montage-style editing as it is for its reflexivity.

She is even seen doing so. At a number of points brief scenes of her examining, sorting, and splicing shots, which are subsequently seen in motion or in freeze-frames.

The film is a documentary, showing the filming, assemblage, and projection of a city symphony along the lines of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt, of two years earlier. Vertov’s version sort of a day in the life of Moscow (and glimpses of other cities), also beginning with the city waking up and going to work. Here, however, we see cinematographer Mikhail Kaufman (Vertov’s brother), with his camera and tripod traveling around the city, climbing factory smokestacks, filming from moving cars, and so on. Although many shots are straightforward documentary images, others use special effects, such as split-screen in the opening shot on the right below.

The film is available (as The Man with the Movie Camera) in Flicker Alley’s Blu-ray of Vertov’s main surviving silent and early-sound films.

Arsenal (dir. Aleksandr [or Ukrainian, Oleksandr] Dovzhenko)

Ukrainian director Dovzhenko came somewhat late to the Montage movement, contributing Arsenal in 1929 and Earth in 1930. When I was in graduate school, these were classics that everyone saw, mainly because 16mm prints were circulating. Now I wonder how many students and cinephiles see them. The standard print that has been released on DVD by a number of companies is quite poor: dark, low-contrast, cropped (though not as badly as the End of St. Petersburg version I complained about in our 1927 list).

Arsenal begins with the return of Ukrainian troops from World War I, with an emphasis on the decimation and impoverishment of the rural countryside with the loss and mutilation of many farmers. Only well into the film are we introduced to Timosha, the stalwart young representative of the proletariat who weaves through the film but does not really become a conventional protagonist.

Dovzhenko has come to be viewed as the poet of the Montage movement, and many of the scenes, especially early on, are more grimly lyrical than part of a straightforward causal chain of events. There is also a touch of what we would now call “magical realism,” as in two scenes where horses speak to their masters. Dovzhenko also employs a wide range of Montage techniques: canted shots (as above); very rapid, rhythmic cutting; jump cuts; compositions with very low horizon lines (below); and so on.

Given the importance of Arsenal, it is a shame that the old copies have not been replaced by high-quality, restored DVDs and Blu-rays. The images here are taken from the best release I know of, Image Entertainment’s old DVD. I’ve boosted the brightness and contrast, but the result is still not ideal, and the DVD is long out of print. (It’s worth seeking out, since it has a commentary track by our friend and colleague Vance Kepley.) The best version I have found is on YouTube, using the Film Museum Wien print. It’s not cropped and has a brighter, less contrasty image (on the right in the comparison above); the subtitles are in French.

Hollywood on the verge

I presume that some readers will expect to see the two official classics of early sound Hollywood, Ernst Lubitsch’s The Love Parade and Rouben Mamoulian’s Applause. Probably in the days of Arthur Knight’s The Liveliest Art (1957) these were some of the rare films from the period that could be seen. They also were by major directors. Looking at them again, though, I don’t feel that they’re up there with the films below.

The Love Parade has the problem of dire sexual politics, the point being that while wives are naturally subservient to their husbands, a man put in the same position is entitled to be upset. That’s what happens when a court official, played by Maurice Chevalier, marries the queen of the mythical kingdom of Sylvania, played by Jeanette Macdonald in her screen debut. Moreover, we’re expected to find humor in a comic subsidiary plot where the official’s valet does a courtship duet with a maid, slapping her around a bit and apparently sexually abusing her in some fashion offscreen. Beyond that, though, there is a gaping plot hole that undermines the whole thing. The official is portrayed as nothing but a serial seducer, and yet when Sylvania is in financial difficulties, overnight he comes up with a brilliant plan to solve everything. In addition, after seemingly obsessed with sexual matters, he becomes bored with his marital position as the queen’s boy toy.

Applause displays rather clumsy camera movements that gave it cinematic flair in an era of clunky camera booths. But it simply seems to me not a very good film otherwise. Thunderbolt effortlessly runs rings around it.

Thunderbolt (dir. Josef von Sternberg)

Decades ago, when I taught the basic survey film-history course at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, one could still rent Thunderbolt in 16mm. I showed it the week we studied the coming of sound. Returning to it now, I still think it’s the greatest early Hollywood talkie that I’ve seen. Here’s a film that came directly after von Sternberg’s string of silent masterpieces (not counting, unfortunately, the lost The Case of Lena Smith), and before one of his best-known works, The Blue Angel.

I’m baffled by the fact that it has never been available on DVD or Blu-ray. Fans share dreadful copies of the old VHS release or off-air recordings. Fortunately Turner Classic Movies aired it some years ago, and we have a watchable, if occasionally glitchy, homemade DVD.

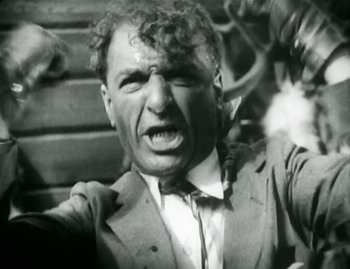

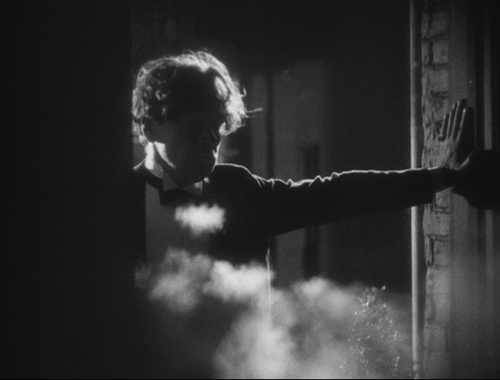

The plot bears a vague resemblance to that of Underworld. A tough crime boss, nicknamed Thunderbolt (again played by George Bancroft), learns that his mistress is secretly seeing a young man and plans to marry him. The resemblance stops there, however. In an attempt to invade the young man’s apartment and murder him, Thunderbolt is finally caught and sentenced to death. Much of the rest of the film takes place in perhaps the strangest death-row prison ever portrayed on film.

Von Sternberg treats sound as a gift, not an obstacle. He cuts from cell to cell, all beautifully lit and composed, while offscreen a seemingly endless supply of singers and instrumentalists perform everything from “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” from a black soloist to a group of singers rendering barbershop-quartet style renditions like “Sweet Adeline” to a classical group that seems to be passing through. Sometimes we see the source of the music, sometimes we don’t. The music doesn’t seem to have much to do with the dramatic action but perhaps reflects the eccentricities of the warden–Tully Marshall chewing the scenery even more than usual.

Speaking of music, the film also includes an early scene with Thunderbolt and his mistress visiting a Harlem nightclub. The prolific black actress Theresa Harris, in her first known role, sings “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” Now that’s using early sound well.

Thunderbolt isn’t quite up to the level of Underworld or Docks of New York. Fay Wray and Richard Arlen make a blander couple than Evelyn Brent and Clive Brook in the former film. Still, it’s a major work in von Sternberg’s career. Let’s hope one of the DVD/Blu-ray companies finally makes it available.

Lucky Star (dir. Frank Borzage)

I well remember the astonishment and delight of the audience at Le Giornate del Cinema Muto in 1990 when the previously lost Lucky Star was shown in that year’s Borzage retrospective. A print had recently been discovered at the Nederlands Filmmuseum (now the EYE Film Institute Nederlands).

Lucky Star was originally released in silent and part-talkie versions. The restored print was of the silent version, which was lucky indeed. Having seen how awkward and distracting the recently restored talking sequences in Paul Fejos’s Lonesome are, one can only cringe at the thought of similar scenes being inserted into Borzage’s lovely film.

Lucky Star again pairs Charles Farrell and Janet Gaynor, who had been firmly fixed as the ideal romantic couple by 7th Heaven and Street Angel.

There can be few, if any films of this period where the romantic leading man spends most of the narrative in a wheelchair. Tim has suffered a grievous injury fighting in World War I, and he and Mary, a young farm girl, fall in love. Mary’s mother insists that there’s no future with a disabled man and forces her to agree to marry a sleazy, bullying soldier. Such prejudice against a “cripple” is the main underlying theme of the film.

The development of the plot is surprisingly leisurely. The first half consists largely of Mary’s visits to Tim and his attempts to help her overcome some of the slovenliness and petty dishonesty stemming from her family’s extreme poverty. There is no real goal or conflict until the intrusion of the rival soldier about halfway through. The charm of the two characters and the actors playing them carry the action effortlessly.

As with 7th Heaven, the studio-built sets are remarkable, in this case representing entire houses set amid rolling woodlands. (See top.) The acting is splendid as well. Farrell in particular is quite convincing as a man who is paralyzed from the waist down. One remarkable shot lasting 2 minutes and 40 seconds has him struggling to leave his wheelchair and use crutches instead before finally falling into the foreground. The framing remains steady until a reframing downward at the end.

Lucky Star is one of the films included in the 2008 box, “Murnau, Borzage and Fox.” So far that invaluable set is still available. Otherwise one can find English and French DVDs of it as imports.

Hallelujah (dir. King Vidor)

For the first time, a mainstream director (Vidor was at the top of his game after enjoying a huge hit with The Big Parade in 1925) and MGM, one of the Majors of Hollywood, acknowledged that a gripping melodrama could be just as entertaining with an all-black cast as an all-white cast. That is, entertaining to those outside the deep South, where exhibitors refused to play the film, robbing it of its chance to become profitable.

Well established as a classic of both early sound cinema and African-American cinema, Hallelujah retains its entertaining quality. It is easy from a modern perspective to dismiss it as racist or dependent on stereotypes. But I think that put in the context of 1929, the film was as progressive as one could expect in the day.

Vidor had long cherished the project and gave up his salary to get a greenlight from MGM. The crew was racially mixed, including an assistant director, Harold Garrison, who was black. More importantly, the musical director, responsible for the many musical numbers, was Eva Jessye, the first widely successful black female choral conductor. A few years later she would participate in the premiere of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s Four Saints in Three Acts, and alongside George Gershwin, she was musical director for Porgy and Bess.

Vidor shot the exteriors in the Memphis area, hiring local black preachers to consult on the religious scenes, including the river baptism. He accepted changes from his cast when they found their dialogue not ringing true. In short, he struggled to be as authentic as he could.

The casting was done with particular care. Zeke was originally to be played by Paul Robeson, the most respected black performer of the day, but he was unavailable. Instead Daniel L. Haynes, a notable stage actor, got the part through having understudied Robeson in the original production of Showboat. Haynes gives Zeke a buoyant appeal that maintains sympathy for him despite his vulnerability to temptation. Nina Mae McKinney, also coming from a stage career, did the same for the seductress Chick.

Hallelujah does not have the technical polish of a film like Thunderbolt, to a considerable extent because Vidor chose to shoot so much of it on location. The tracking shots during the opening number, “Oh, Cotton,” are certainly impressive for a 1929 film. There is also some impressive night shooting during Zeke’s chase after the escaping Chick.

Hallelujah is available on DVD from the Warner Brothers Archive Collection. Unfortunately the company has chosen to put a boilerplate warning at the beginning that essentially brands Hallelujah as a racist film:

The films you are about to see are a product of their time. They may reflect some of the prejudices that were common in American society, especially when it came to the treatment of racial and ethnic minorities. These depictions were wrong then and they are wrong today. These films are being presented as they were originally created, because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming these prejudices never existed. While the following certainly does not represent Warner Bros.’ opinion in today’s society, these images certainly do accurately reflect a part of our history that cannot and should not be ignored.

I don’t think this description fits Hallelujah, but it certainly sets the viewer up to interpret the film as merely a regrettable document of a dark period of US history. Warner Bros. demeans the work of the filmmakers, including the African-American ones. The actors seem to have been proud of their accomplishment, as well they should be.

Sound and silence

Blackmail (dir. Alfred Hitchcock)

Long ago, when I first saw Blackmail, I thought it was a pretty mediocre, clumsy film. Luckily I have learned quite a bit about cinema since then and can appreciate Hitchcock’s clever use of sound–beyond just the famous “knife … knife … KNIFE” scene.

There’s the sequence where the blackmailer saunters into the tobacco store run by the heroine’s parents. He starts forcing her and her policeman boyfriend to pamper him with an expensive cigar and a good English breakfast. As he eats, he whistles “The Best Things in Life Are Free,” successfully annoying the boyfriend even further (above).

Earlier in this scene, Hitchcock presents a leisurely long take as the blackmailer performs an elaborate examination of said expensive cigar. His byplay generates suspense in us about whether he will get away with his tactic, as well as suspense in the father as to just when he is going to pay for that cigar.

The scene works well enough in the silent version of the film, but the little sound effects and muttered comments of the blackmailer make it a combination of tension and humor that wouldn’t come across without the sound. It also makes a nice contrast with the extended scene of the heroine in the artist’s studio. There the veiled threat of his seduction attempt and her naive reactions create a genuine suspense with no humor.

In contrast, there are passages of fast cutting that help avoid the stagey quality of much early sound cinema. The opening police raid and the later chase after the blackmailer through the British Museum’s Egyptian rooms (see bottom) both employ this tactic effectively.

By the way, I always thought that the giant pharaonic head in the shot where the blackmailer slides down a chain must have been a process shot, with a smaller head blow up for effect. Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray disc of the film, though, shows the label under the head well enough to reveal that it’s a cast of one of the giant heads of Rameses II from his temple at Abu Simbel (see bottom). Casts aren’t much in favor in most museums these days, so it’s no longer on display.

Pandora’s Box (dir. G. W. Pabst)

Fritz Lang, who has appeared quite regularly on these lists, released only The Woman in the Moon, his least interesting 1920s film, in 1929. Expressionism was over. In contrast, Pabst filled in with perhaps his most popular film, Pandora’s Box.

The film derives from a pair of Expressionist plays, Earth Spirit and Pandora’s Box, by Frank Wedekind. The first play had been filmed in 1923, as Erdgeist with Asta Nielsen as Lulu, and directed by Leopold Jessner in the Expressionist style. It survives but is among the most difficult Expressionist films to see. Pabst combined the second half of Earth Spirit and the entirety of Pandora’s Box for his version.

The play and film both depend on the central character being played by someone who can simultaneously Lulu’s conflicting traits: her vivacious joy in living, her strange mix of generosity and selfishness, her egalitarian attitude toward others, and her naive amorality. American star Louise Brooks was perfectly cast, as were the supporting roles, including veteran Expressionist actor Fritz Kortner as the wealthy publisher who is keeping Lulu as his mistress at the film’s beginning.

Although the source material would lend itself to Expressionist designs, Pabst went for a more modern, streamlined look, as in Lulu’s apartment (below) and the luxurious home of Dr. Schön.

Pandora’s Box was issued on DVD by The Criterion Collection but is now out of print. We can hope for a Blu-ray version.

Wild and tame surrealism

I’m dividing the tenth slot for two very different short films that were in their own ways experimental masterpieces that had a considerable lasting influence.

Un chien andalou (dir. Luis Buñuel)

Few if any trends in cinema have been so dominated by a single film. Surrealism was still a concentrated movement in the late 1920s, before it diffused out internationally to become a permanent option for experimental filmmaking. With Salvador Dalí as scriptwriter, Buñuel managed to create a loose narrative centered around displaying constant incongruous juxtapositions and inexplicable occurrences. It also aimed to offend, with the opening eye-slitting, the attempted rape, and the cavalier treatment of the clergy.

Un chien andalou, being short and in the public domain, is widely available online and on DVDs issued by small companies. I haven’t seen the BFI’s Blu-ray of L’Age d’or and Un chien andalou, but that would seem to be the best bet for quality.

The Skeleton Dance (dir. Walt Disney, animator Ub Iwerks)

The Skeleton Dance is a much tamer film than Un chien andalou, a humorous, entertaining treatment of the disturbing subject of death. (Nevertheless, it was reportedly banned in Denmark as being too macabre.) The subject was apparently suggested to Disney by composer Carl Stalling, whom the director approached to do music for two earlier Disney films. Stalling was interested in creating films based on musical themes, and The Skeleton Dance became the first of Disney’s “Silly Symphonies” series.

Stalling eventually moved on to Warner Bros.’s animation unit, where he composed the music for two series modeled on (and parodies of) the “Silly Symphonies”: the “Merry Melodies” and the “Looney Tunes.” Thus The Skeleton Dance helped inspire three of the great animated series of the 1930s and beyond.

The cartoon has only the loosest of plots, running (much as the “Night on Bald Mountain” episode in Fantasia would) through the eerie events of a night through to the calming effects of dawn. The opening features a frightened owl (below left) and a howling dog, but the main “characters” are four skeletons that leave their graves to dance and cavort. Iwerks showed off his virtuoso skill, with the complex figures of the skeletons moving in circles so that they crossed over each other, as in the circular dance in the image above. He also uses two basic techniques of animation, stretch and squash, to turn the rigid bones into lively, pliable figures (below right).

The Skeleton Dance is included in the “Walt Disney Treasures: Silly Symphonies” DVD set, now out of print.

Compilations of Carl Stalling’s brilliantly zany (and surrealistic) music for the “Merry Melodies” and “Looney Tunes” were released on CDs as “The Carl Stalling Project” Volume 1 and Volume 2. Remarkably and deservedly, these are still in print after many years. If you do not already own these, hasten to buy yourself a belated Christmas present.

Conclusion: Acknowledging two notable events

The year saw Buster Keaton, who has figured so prominently in these lists, make his final silent feature, Spite Marriage. A pleasant film, but one which does not reach the heights of his great comedies earlier in the decade. Second, the earliest surviving film of Yasujiro Ozu, Days of Youth, dates from 1929. Although not top-ten material, it already displays his unique style. Assuming we continue this annual list, it will not be long before Ozu begins appearing on it.

There’s an ongoing controversy over versions of New Babylon. Specialist Marek Pytel has noted that a number of scenes were cut from the film after its premiere, thus making the new version impossible to synchronize with Shostakovich’s score. The missing footage having been rediscovered, Pytel has constructed a new print and synced it with a piano version of the score. His website on the restoration of the original version is here. Ian McDonald has written an extensive series (in three parts, here, here, and here) analyzing in complex detail the evidence for and against Pytel’s claims. Among those is Pytel’s statement that Trauberg told him that the initial version is the one that he and Kozintsev would consider definitive, while at other times the director said that the edited version as released is the preferred one.

Pytel also has claimed that Kozintsev and Trauberg wanted the musical score to be recorded and added to the film; he argues that the film should be run at 24 fps and used that running time in the small number of live performances that have so far been the public’s only access to his version. The very low-resolution clip from Pytel’s version that he posted on Youtube, however, shows the action to be distinctly too fast at 24 fps. Perhaps Kozintsev and Trauberg would have accepted this faster action in exchange for a musical track, but it would have been quite distracting.

The standard version on the Dutch/German DVD seems to me to be running at the correct, slower speed, with the music reasonably well synced.

Whether or not the standard version is the preferred one, it has long been the one we have, and it is quite brilliant as it stands. Being episodic, it does not show signs of being incomplete, though obviously one would wish to see the extra footage in the Pytel version to be able to judge.

Our friend and colleague Ian Christie, noted historian of Russian and Soviet cinema, discusses the historical context of New Babylon in a short video essay.

Blackmail.

The ten best films of … 1928

La passion de Jeanne d’Arc

Kristin here:

Time for our twelfth annual alternative to the usual list of the ten best films of the current year. Instead, I offer a list from 90 years ago, in part for fun and in part to call attention to some lesser-known classics that are worth discovering. (See here for our lists from 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, 1926, and 1927.)

The year 1928 marked the triumphant conclusion of the silent cinema. Very few sound films were made that year, and those that were often included only music, perhaps sound effects, and occasionally some passages of dialogue. Sound was not innovated because the silent cinema was in aesthetic decline. Quite the contrary. It was initially an enhancement that film-industry people assumed would make films more lucrative. In most cases the “talkies” that followed over the next few years were inferior to their silent predecessors, in part due to the limitations of the new sound technology. Those who opposed the addition of sound could point to the films of 1928 as evidence that the young art form had already reached a peak of perfection that was being tarnished by the addition of recorded sound.

In compiling this year’s list, I came up with eight titles that seemed unquestionably to belong on it. There were another six on a list of possibilities for the final two slots. More than in past years, this year gave me a chance to go back and rewatch films I hadn’t seen in a long time, in some cases since graduate school in the 1970s. Some held up well, some not so much. In a few cases, restorations made since my first viewings revealed new strengths in films I remembered from poor prints.

As always, there are films that have been lost but which plausibly could have filled out the list, most notably Ernest Lubitsch’s The Patriot and F. W. Murnau’s 4 Devils.

First, the eight obvious choices, in no particular order apart from #1.

1. La passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

Not every year includes a film that is not only one of the tops of its year but of all cinematic history as well. Carl Theodor Dreyer’s final silent film is one such masterpiece.

Jeanne d’Arc seamlessly blended the stylistic traits of the great artistic film movements of the 1920s, German Expressionism, French Impressionism, and Soviet Montage and made something new and unique of them.

Expressionist designer Hermann Warm’s past credits had included two films that have featured in these lists, Robert Wiene’s Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Fritz Lang’s Die müde Tod. Warm collaborated with French theatrical designer Jean Hugo to create spare, white, off-kilter sets that focus our attention on the spiritual drama. Fast editing conveys subjectivity, as in the scenes where Jeanne is threatened with torture and where the citizens are suppressed when they riot after her execution. Rudolph Maté’s cinematography is startlingly dependent on close shots, particularly on the face of Jeanne, played by Renée Falconetti in one of the most intense and affecting performances in any film.

The steady progression of the action condenses days of trial testimony into one apparently continuous story. Between the sets and this inexorable march toward Jeanne’s martyrdom, there is a sense of both spatial and temporal disorientation that focuses our attention intensely on the central conflict.

Until 1981, prints of Jeanne d’Arc were indistinct and incomplete. A pristine print that restored the original visual quality and detail was found in Norway. (The film was among the early ones to be shot on panchromatic film stock without the actors’ using makeup. The result is a detail of texture in the faces that enhances the performances tremendously.) This print is the basis for the Criterion Collection’s edition of the film.

It’s a film that one can see over and over and still be overwhelmed at the originality and intensity of Dreyer’s vision. We saw it projected last November in Houghton, Michigan, with Richard Eichhorn’s recently composed accompaniment, “Voices of Light,” essentially an oratorio and film score rolled into one. We were somewhat trepidatious about whether the score would be distracting, but it proved very effective. Once again, I was reminded of how great this film is. (“Voices of Light” is an optional accompaniment on the Criterion edition linked above.)

2. October

If Jeanne d’Arc gains intensity through a nearly claustrophobic treatment of space, Sergei Eisenstein creates an epic tenth-anniversary celebration of the 1917 Revolution in his October (finished and released a year late).

Perhaps the most extreme example of Soviet Montage’s frequent avoidance of a single protagonist, October cuts among a wide variety of the people involved in the revolution. Workers pull down a statue of the Tsar. Lenin speaks at Finland Station. Kerensky and his officials luxuriate in their Winter Palace headquarters. Sailors wait on the Aurora battleship. Elderly citizens try to protect the specious February Revolution. Female soldiers are summoned to protect the Palace from the attacking Red forces. Looters steal bottles from the Tsar’s wine-cellar. The result is a sort of patchwork collage of the Revolutionary events leading up to the storming of the Winter Palace and the attack itself, with a slow build to an exultant climax as the Red forces triumph.

Eisenstein was given extraordinary access to the locales of the actual events, so that the vast halls of the Winter Palace and the trappings of royalty (Fabergé eggs and fancy crystal liquor bottles) give a sense of reality rare in fictional reenactments. (There was a time when October was plundered for “documentary” footage of events which had not been recorded by cameras at the time.) He used the settings to ridicule the anti-revolutionary forces, as when young cadets are summoned to help fight the Red forces and are dwarfed by the muscular colossi that line one area of the Palace’s exterior (above).

The film also represents Eisenstein’s experiments with “intellectual montage,” where he attempts to convey ideas strictly through juxtaposing series of images. In belittling the phrase “for God and country,” he tries to reduce the notion of “God” to absurdity by linking a long series of increasingly exotic depictions of deities from different religions.

Whether Soviet audiences of the late 1920s could make anything of such passages is impossible to know for sure, but one suspects that some of them would have been incomprehensible. Still, it is exciting to see an artist playing with such possibilities. Certainly the technique lived on, whether from the simple juxtaposition of cackling hens and gossiping women in Lang’s Fury or Jean-Luc Godard’s dense, often impenetrable strings of images, especially in his political films.

October exists in many versions. Beware the heavily cut versions under the title Ten Days That Shook the World. These images were taken from the 2008 release by the Soviet Ruscico company in its “Kino Academia” series.

3. Spione

Despite the widespread enthusiasm for Lang’s Metropolis, his other big films of the 1920s–Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Die Nibelungen (Siegfried and Kriemhilds Rache), and Spione–seem to me better. Metropolis is perhaps flashier in its design and conception and certainly very entertaining, but it’s also sprawling and implausible and essentially pretty silly.

Spione, on the other hand, has a tight, fast-paced narrative. It’s sort of Dr. Mabuse boiled down to one feature instead of two, and with the villainous Haghi (again played by Rudolf Klein-Rogge) as a banker secretly masterminding a spy ring rather than a gambling racket. There are no great “heart vs. hand” themes here–just a rattling good tale stylishly presented. Expressionism has disappeared in favor of a streamlined look (above), and Lang’s editing has sped up since Mabuse.

There’s not much point in detailing the plot here, since it would involve too many spoilers. Discover it for yourself if you haven’t already.

Spione circulated for years in the truncated American release version, which is how I first saw it. A 2004 Murnau Stiftung restoration of the complete version was a revelation, not only for its more complete narrative but for its superb visual quality. It’s a feast of shots that only Lang could have composed (above and bottom). These frames are from the Eureka! DVD, but the company has subsequently released it in dual format DVD and Blu-ray. Kino Classics has also released it in Blu-ray. The same company has put out a boxed-set of all Lang’s silent films (including Die Pest im Florenz, directed by Otto Rippert from Lang’s script). We were given this recently and haven’t had time to explore it, but it looks like a must for any fan of Lang.

4. L’Argent

Marcel L’Herbier makes his second and final appearance on this annual list with his epic adaptation of Emile Zola’s L’Argent, updated to contemporary Paris. (See the 1921 entry for El Dorado; I also wrote about the Flicker Alley releases of the restored versions of L’Inhumaine [1923] and Feu Mathias Pascal [1925].)

Inspired by Abel Gance’s even more epic Napoléon (1927), L’Herbier set out to make a film that would require a large budget. To obtain that, he made a deal for his own company, Cinégraphic, to co-produce with the mainstream studio, Cinéromans. The result contains brightly lit sets of big banks and expensive apartments, as well as shots made in the Paris Bourse over a three-day weekend (above). L’Argent also had an all-star cast. It included Brigitte Helm and Alfred Abel fresh off Metropolis, thanks to the German distributor, UFA. It also meant that Cinéromans tampered with the film, re-editing and shortening it.

Given L’Herbier’s reputation as an aesthete and an avant-garde filmmaker, L’Argent was dismissed by many at the time as a purely commercial endeavor. It remained unseen and hence virtually forgotten for decades. A screening at the New York Film Festival in 1968 surprised and impressed the spectators. The real recognition of the film as a major artwork came, however, in 1973, when critic and theorist Noël Burch published his monograph, Marcel L’Herbier (Paris: Seghers, 1973). In it he hailed L’Argent as a masterpiece, devoting the entire final chapter to an analysis of it. Burch also wrote the entry on L’Herbier for Cinema: A Critical Dictionary: The Major Film-makers ([New York: Viking Press, 1980], Vol. Two, pp. 621-28), edited by Richard Roud; again Burch devoted much of his text to L’Argent.

I have expressed my reservations about L’Herbier’s films in earlier entries, but for me L’Argent is the big exception: stylistically daring and narratively engaging. Perhaps adapting Zola led L’Herbier to make a more conventionally suspenseful film than usual. Referring to the French Impressionist movement in general, Burch wrote, “L’Argent undoubtedly marks the end of the period of experimentation, since it is itself the culmination of all these experiments–not just L’Herbier’s, but those of the first avant-garde and even, to a certain extent, of the entire Western cinema (with the exception of the Russians)” (Roud, pp. 624-25).

The story involves two powerful bankers who spar for control of one large bank’s standing on the stock market. One, the villainous Saccard, aims to send a famous aviator on a perilous flight across the Atlantic to promote his bank’s oil holders in Latin America–while seducing the aviator’s wife during his absence. The other, Gundermann, tries to thwart him by buying up shares of his rival’s bank and then selling them to cause a drop in the bank’s value.

In portraying all the complex machinations going on, L’Herbier adopts a restless camera, frequently moving among and around characters rather than following them. The most striking example comes early on, when an underling comes to visit Gundermann and waits in an odd, unfurnished room decorated with a map of the world. As he looks around, the camera circles him until a servant unexpectedly appears through a door and escorts him in.

The odd distortions in these shot exemplify another cinematographic technique that was in increasing use during the late 1920s: conspicuous wide-angle lenses. On the left below, Saccard is nearly dwarfed by one of his telephones, while on the right the scene of the aviator’s departure makes the plane’s wings jut into the foreground and extend far into the background.

There are some subjective moments, carrying forward the tradition of French Impressionism. Yet for the most part the restless camera, the distorting lenses, the odd angles (see the top image of this section), and the unusual crosscutting are not subjective, which makes this an atypical Impressionist film. Instead they suggest the unnatural, disconcerting world of capitalism, of money and those who struggle over it. Perhaps by minimizing character psychology and striving to represent more abstract concepts, L’Herbier briefly carried Impressionism to a more political–and dramatic–level.

In 2008, L’Argent was released on DVD by Eureka! in the UK as a “Special 80th Anniversary 2 x Disc Edition.” The source material was a beautiful fine-grain positive struck from the original negative, with something close to L’Herbier’s original intended cut. It includes Jean Dréville’s Autour de “L’argent,” a 40-minute making-of (surely one of the first of its type), recorded during the original production. The DVD is still in print and is, as far as I know, the only release of this restored version.

5. Steamboat Bill Jr.

This was the first Keaton film I ever saw, and I immediately became a fan. (The director is credited as Charles Reisner, but we all know that Keaton was primarily responsible for the direction of his films of this period.) It’s not as good as The General (what is?), but it beats out The Cameraman, Keaton’s other feature of this year, by a nose.

Keaton plays the dandified son of a gruff steamboat owner. He returns home from school and gets put into working clothes by his father, whose deteriorating steamboat is competing for tourists with a larger, newer boat. Naturally young Bill is in love with the daughter of the other steamboat’s owner. The action mainly consists of Bill, Sr. trying to prevent Bill, Jr. from clandestinely meeting his girlfriend.

There’s lots of humor along the way to the climax, in which a huge storm hits the town. It’s a classic sequence of Keaton pulling variant gags on the situation of being in a high wind (above) and surrounded by collapsing buildings and flying objects. Perhaps Keaton’s most famous, and dangerous, gag comes when he pauses in front of a house’s façade, which tears loose and falls straight down on him–with a window sparing him from being crushed.

Reportedly the top of the frame missed his head by six inches, but we know Keaton was a little crazy in how far he would go for a laugh.

Steamboat Bill, Jr. was the last film Keaton made with his own production company. The Cameraman was made at MGM, and though it is very good, thereafter his career slowly declined after his move to that studio. This will, alas, be the last Keaton film represented in this series.

6. The Circus

Coincidentally, The Circus was the first Chaplin film I ever saw. I happened to take my first film course at the point where Chaplin had re-released The Circus, accompanied by a new musical score he composed himself. (Skip, if you can, the added opening, with Chaplin singing a maudlin song over an excerpt from later in the film.) The re-release was 1969, though I must have seen it in 1970 at Iowa City’s art-house, the Iowa. (Also coincidentally, my father managed the Iowa when he was at the university there on the GI bill in the years immediately after World War II. He was dating my mother at that point, and there she saw Day of Wrath. Hence when David and I became a couple in the mid-1970s, she understood what the book he was currently working on was about. But I digress.)

The print I saw at the Iowa was pristine.

Up to that point, The Circus had been unavailable to most viewers, though I suspect bootleg prints circulated among collectors. It’s among the least known of Chaplin’s features, and it’s still hard to see. There’s a Park Circus DVD available in England, consisting of the re-release version equally in mint condition; that’s the one I’ve taken these illustrations from. More recently the film has been released as a Blu-ray/DVD combination. There is also an Artificial Eye Blu-ray available, which gets high marks from DVD Beaver. I haven’t seen this and don’t know whether it’s the re-release version or the original.

Chaplin plays his Little Tramp character, introduced wandering around the sideshow attractions near a circus. Mistaken for a pickpocket, he flees among the booths, occasioning a brilliantly staged triple scene in a hall of mirrors. When he first enters it, he is alone and struggles to figure out how to exit. A short time later, pursued by the pickpocket, the two stumble into the room, and a comic chase ensues (above). Finally, a cop is chasing Charlie, who tries to confuse him by luring him into the mirror maze. It’s a set of gags that builds, with the figures popping unexpectedly into the foreground when we had assumed that the real actors were in the depth of the shot. Each scene in the maze is handled in a single take from the same camera setup.

The flight from the cop leads the Tramp into a failing circus cursed with a group of highly unfunny clowns. Charlie inadvertently and unwittingly becomes a sensation for his antics, including his invasion of a magician’s act.

The cruel circus owner hires him, supposedly as a prop man, and the show becomes a huge success. Charlie falls for the maltreated daughter of the owner, who in turn becomes smitten by a handsome tightrope walker. Trying to impress the daughter, the Tramp goes on when the tightrope walker fails to show up one day. The result is a classic extended scene of Charlie on the high wire, executing a series of comic moments before the whole thing is topped off by a group of monkeys who escape and end up swarming over him as he struggles to keep his balance.

I hope now that The Circus is becoming more available, it can takes its place beside Chaplin’s other features.

[December 29: Thanks to Valerio Greco for alerting me that a restoration of the original version of The Circus is underway in Bologna, to be released by The Criterion Collection.]

7. The Docks of New York

I’ve already written about this, Josef von Sternberg’s final silent feature, in 2010 on the occasion of The Criterion Collection’s release of it alongside Underworld and The Last Command in an essential box-set. The six films von Sternberg made with Marlene Dietrich after she came to Hollywood generally get more attention than any of his silents. If I were allowed three of his films for a proverbial desert-island situation, I would take Underworld, The Docks of New York, and Shanghai Express.

Docks is a concentrated dose of the atmospheric cinematography the director is famous for, in this case employed to create the grungy settings of the film. In the opening, the oil and sweat on the stokers’ bodies (above) is palpable, and the fog, hanging nets and lanterns, and smoke of the dockside sets establish the sleezy, hopeless milieu that drives the heroine to attempt suicide.

Apart from the impressive visuals, the film gains much of its appeal from its two central performances. Betty Compson manages to gain our considerable sympathy for “the Girl” in a remarkably short time, and she has to–the film is only 75 minutes long and she spends her first onscreen appearances unconscious after her near-drowning. George Bancroft, known mostly for supporting roles in westerns, came into his own as the protagonists of three von Sternberg films–including Thunderbolt but not The Last Command. Here he again plays the big lug with a well-hidden heart of gold.

Unfortunately the von Sternberg silents set from The Criterion Collection is out of print. Track it down somewhere or hope for a Blu-ray release.

[December 29: Peter Becker of The Criterion Collection tells me that, although a Blu-ray release is not yet scheduled, there is a good possibility that it will happen.]

8. Storm over Asia

After Mother and The End of St. Petersburg, Storm over Asia (the original title translates as “The Heir of Genghis Khan”) is the last of Vsevolod Pudovkin’s three great silent features. Unlike the first two, it is set in Mongolia. The Soviet industry officials were concerned to portray the Revolution in the various other countries that along with Russia made up the Soviet Union.

The story takes place during the Civil War years that followed the Revolution. A young Mongolian peasant tries to sell a valuable fox fur at a trading post, but the British dealer cheats him. The peasant strikes him and is forced to flee into the mountains, where he joins the Red partisans fighting the British imperialists. (This does not follow historical fact, since the British occupied parts of Siberia and Tibet, but not Mongolia. In reality, for a brief period in 1921, White Russian forces drove out the Chinese from Mongolia. In response, the Red Army moved in, supporting the Mongols in their quest for independence.)

The British shoot the protagonist but discover on him a document that seems to identify him as the heir of Genghis Khan. So they set him up as a puppet ruler in order to control the local population. Eventually he rebels and leads a storm-like assault that defeats his oppressors.

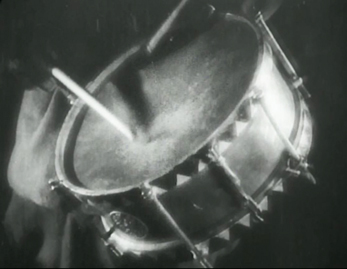

Storm over Asia uses many of the Soviet Montage devices that by 1928 were fairly conventional. For instance, there are many rapid, rhythmic alternations of shots. When the fur trader reacts angrily against the protagonist’s resistance to being cheated, brief shots of his angry call for troops to capture the young man alternate with shots of a drum being beaten. The final “storm” battle uses rapid montage as well. There is also the usual visual symbolism mocking the enemy, as exemplified by the empty officer’s uniform in the shot above.

Early Montage films tried to do away with a single central character in favor of a focus on the masses. October, for example, has no main hero. In Storm over Asia, though, the story arc is definitely crafted around the Mongol’s growth into a rebellious leader of his people. We will see Eisenstein opting for a central identification figure in Old and New (1929).

My illustrations were taken from the old Image release, apparently no longer available. The Blackhawk print has been released by Flicker Alley.

Those are the eight films I put on my “top” list. I thought of stopping there, but the number ten is sacred for such lists, plus part of the point here is to throw a spotlight on lesser-known films.

I gathered a second group of films that might claim the remaining two slots. These were mostly films that were already hallowed classics when I was in graduate school: King Vidor’s The Crowd, Jean Epstein’s La chute de la maison Usher, René Clair’s The Italian Straw Hat, and Victor Seastrom’s The Wind. Beyond that there were the more recently rediscovered and much admired film, Paul Fejos’ Lonesome and the still little-known The House on Trubnoya, by Boris Barnet.

Oddly, the three American films on this list have some distinct similarities. The Crowd and Lonesome are surprisingly parallel. Lonesome follows two lonely people in New York finding each other and falling in love in one hectic day. The Crowd starts with a somewhat similar situation–both even involve dates at Coney Island–but follows the couple through several years of happy times and misfortune during their marriage. The Wind is less realistic, dealing with a sensitive young woman who travels to the west and, plagued by the incessant wind and a real or imagined rape, slips into madness. All three strive to reject the conventional Hollywood romance. Unfortunately all three, however admirable for most of their plots, lead to abrupt, implausible happy endings.

I saw The Italian Straw Hat in my graduate-school days and found it remarkably unfunny, given its reputation. Returning to it now, I still find the first two-thirds largely devoid of humor. (The dance scenes during the wedding party seem interminable, with no little vignettes or gags among the characters at all.) The last portion picks up, but on the whole it’s hardly the model French farce it is held to be. Certainly Clair made a leap forward in skill and sophistication in his early sound films. (Les deux timides, also 1928, is no doubt a better film.)

The Italian Straw Hat probably owes its classic standing in part to the fact that the Museum of Modern Art acquired and circulated it early on. Curator and critic Iris Barry adored it and lauded it in a 1940 essay (reproduced in the booklet included in the Flicker Alley release.) I wonder how many others of the films considered classics have become so because they were among the few silents available in the decades before the 1960s, when film studies and archival curatorship began to be more comprehensive. Knowing the range of international films we know now, would these films have become quite so highly respected above others? I found myself reluctant simply to fill out my list with old standards. The choice was difficult.

Wanting to avoid carrying on the older canon at the expense of more recently rediscovered films for at least one of my films on this list, I always try to include a little-known but worthy film here. This year there is only one (if you don’t count L’Argent), and that is Barnet’s The House on Trubnoya.

The final slot goes to Epstein’s The Fall of the House of Usher. I have always considered this a somewhat tedious film, but the restoration of the film’s full length and improved visual quality in the Epstein box-set released in 2014 by La Cinémathèque Française makes it far more interesting and effective.

So here is the completion of my list.

9. The House on Trubnoya

Boris Barnet was a member of Lev Kuleshov’s school in the early years after the revolution. He played a major role in Kuleshov’s The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, and he began directing films on his own with the wonderful serial, Miss Mend. He made more films, and some others may show up in our coming lists. Right now, there’s The House on Trubnoya.

The House on Trubnoya is included in Flicker Alley’s major DVD set, “Landmarks of Early Soviet Film.” (I can’t believe that we didn’t feature this on our blog, but it includes eight major Soviet films of the silent era.) The copy on the back of the box describes Barnet’s film as “often described as one of the best Soviet silent comedies.” I’m not sure that’s a major distinction, though Kote Miqaberidze’s Georgian satire My Grandmother (1929; available on DVD and Fandor’s Amazon streaming site) is quite funny, as is Ivan Pyriev’s The State Functionary (aka The Civil Servant; not, as far as I know, available on home video). But The House on Trubnoya is my favorite among the comedies I’ve seen.

It’s a satire on middle-class citizens’ maltreatment of their servants, though it doesn’t become Soviet-style preachy until well into the story. The film begins by setting up the titular house (on a well-known street in Moscow). We see it via its staircase and landings in the morning, rendered in a vertical view that looks startlingly like an iPhone image (above). It also recalls the seven levels in the staircase elevator shot climbing upward to 7th Heaven, though who knows whether Barnet had seen that by the time he planned his film. The residents of the various apartments emerge to use the communal stairway as a junkyard and work area, dumping trash, splitting firewood, beating curtains, and generally abusing the rules of the building, as one conscientious young Party member points out.

We are introduced to a barber, whose lazy wife makes him do all the chores. Then suddenly we’re with a professional driver with his own car. Just as suddenly we’re watching a peasant girl chase her runaway duck through a maze of traffic and nearly get hit by a tram. As the driver brakes hastily and jumps out to see if she’s hurt, there’s a freeze-frame.

A narrating title declares, “”But wait, we forgot to tell you how the duck ended up in Moscow.” Reverse motion leads to another title, “A day earlier.” A flashback to the heroine’s comic departure from a train station in the middle of nowhere shows the very uncle whom she is going to Moscow to visit arriving at the station just after she has left. Finding herself lost in Moscow with her duck, the heroine gains employment as a put-upon maid serving the barber and living in the house on Trubnoya. Her political awakening and the rehabilitation of the House on Trubnoya form the rest of the plot.

The House on Trubnoya is, in short, an imaginative, clever, and funny Soviet Montage film. Barnet’s other films are worth exploring as well. Check out The Girl with the Hatbox from 1927; it didn’t make last year’s top items, but it was on the long list.

10. La Chute de la maison Usher

Jean Epstein, who was probably the finest of the French Impressionist directors, has figured in these ten best lists before, in 1923 for Cœur fidèle, in 1924 for the little-known L’affiche, and 1927 for his masterly La Glace à trois faces.

I have long considered La Chute de la maison Usher interesting for its use of German Expressionist-inspired sets, but the fuzzy, incomplete prints that for decades were the only available versions made it difficult to enjoy. The restored version on the complete DVD set of Epstein’s works, which I discussed here, makes it far more interesting.

Taking its slim plot from Poe, the film follows a visit by an elderly man to the isolated castle of his old friend, Roderick Usher. Usher is painting a portrait of his beloved wife, but it is soon made clear that each time he presses the brush to the canvas, a little of her life is drained away–though the local doctor is mystified by her decline.

The film retains some of the traits of Impressionism, as when Madeline’s reaction to the effects of her husband’s painting are rendered in a superimposition of negative and positive images of her face.

The film has a minimal plot, but its focus is largely on experimentation in creating an eerie atmosphere. Shots of books falling in slow motion from their shelves, of curtains blowing in a cold wind that seems perpetually to invade the house, of frogs copulating in a nearby pond, and of the Expressionist-derived decors contribute less to a linear plot than to a mood of undefined menace.

The castle’s exterior is represented by obvious cardboard models, which tends to undermine the effect created by the interiors. The cheapness of these models is particularly noticeable in the climactic scene of the destruction of the house. This is unfortunate, but one must give Epstein credit for having done so much with so little.

This will be Epstein’s final appearance in our “Ten Best” lists, but I would like to call attention to his other 1928 film, Finis Terrae, the first of what the Epstein box-set collects as his “Poémes Bretons.” These are less Impressionistic, though Finis Terrae has a few impressive subjective shots. They are more realistic and poetic, largely involving the sea.

As I wrote at the beginning, 1928 was part of the period when the American industry was on the cusp of making sound standard in its films. Other national cinemas followed at various paces. One film that did not quite make my top-ten list demonstrates what must have worried film theorists and critics–and no doubt some filmmakers.

The restored version of Lonesome includes some dialogue sequences in a film otherwise accompanied by recorded music. There is an enormous contrast between the silent and sound footage. The story is largely told visually, but the dialogue scenes, clearly done in a sound-proof studio, are delivered in a stilted fashion by the young actors who are otherwise so casual and lively. The prospect of whole films being made in that fashion clearly disturbed lovers of films like La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc and Steamboat Bill, Jr. Watching Lonesome gives a dramatic insight into this slice of cinema history–a period that fortunately lasted only a few years as the technology improved and as filmmakers increasingly managed to make sound films that were just as imaginative, artistic, and engrossing as their silent predecessors.

January 6, 2019: Thanks to Docks of New York fan Tony Lucia for a correction on that section.

Spione

Never too late silents

Underworld

Kristin here:

At last one of the gaping holes in the repertoire of classics on DVD has been filled. Tomorrow the Criterion Collection is releasing a three-disc set of Josef von Sternberg’s three final surviving silent films: Underworld (1927), The Last Command (1927), and The Docks of New York (1928).

Von Sternberg is most famous for his string of films starring Marlene Dietrich, from The Blue Angel in 1930 to The Devil Is a Woman (1935). To me, though, Underworld and The Docks of New York jointly form the summit of his career, with The Last Command a lesser masterpiece in between.

Each beautifully mastered print (slightly window-boxed to assure the correct ratio on a variety of TV sets) comes with two musical accompaniments. Robert Israel has done an original orchestral score for each, with the Alloy Orchestra playing alternatively for Underworld and The Last Command and Donald Sosin and Joanna Seaton for The Docks of New York.

David and I were lucky enough to see the first two films with the Alloy Orchestra live at Ebertfest 2008 and 2009. Afterward I asked the trio whether they would consider scoring Docks as well, and they said they were interested. Maybe someday.

I wrote the Ebertfest program notes for Underworld, and I’m reproducing that text here, with minor revisions.

Underworld

Certain years in the history of film stand out for having produced more than their fair share of masterpieces. 1927 was one such year. In the United States alone, there were Buster Keaton’s The General, Frank Borzage’s 7th Heaven, F. W. Murnau’s Sunrise, Harold Lloyd’s The Kid Brother, and Josef von Sternberg’s Underworld. On a slightly less exalted plane there were Ernst Lubitsch’s The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg and William Wellman’s Wings, the latter the winner of the first best-picture Oscar.

Such films demonstrate the utter mastery of visual storytelling that American filmmakers had gained over the past decade. Ironically, it was also the year of The Jazz Singer, the hit film that made it inevitable that sound would be used for more than recorded musical accompaniment. The constraints imposed by the crude early sound technology meant that most filmmakers would not regain the flexibility of the silent period for a few years. It’s no wonder that in the early years of the talkies, some filmmakers and theorists felt that sound had ruined an artform that had just come into its own.

Underworld was von Sternberg’s fourth film, and his second surviving one. His first feature, The Salvation Hunters (1925), was a slow-paced exercise in grim naturalism, utterly at odds with the style he later developed. We see that style already fully mature in Underworld.

The plot is relatively simple, dealing with a love triangle that develops between gangster “Bull” Weed, the reformed drunkard, “Rolls Royce,” whom he takes on as his right-hand man, and Bull’s girlfriend “Feathers.” (Rolls Royce, Feathers, and their photogenic hats at left.) Von Sternberg tells his story visually, stringing together close-ups that convey the action, close-ups not just of faces but of telling details or gestures that capture the essence of a scene. His editing makes not only for clarity and efficiency, but often for vividness and excitement as well. A contemporary reviewer rightly singled out the virtuoso scene of Bull stealing a bracelet for Feathers: “The jewelry-store hold-up is done in four flashes: a pistol shot smashes a clock set above shelves full of silver; a frightened clerk turns; a hand scrapes diamonds from their cases; a crowd is seen through the store’s plate-glass window … This kind of incisiveness, this giving of the part for the whole, when used imaginatively, not spottily or as a trick, is a method exactly suited to the screen, and one little used.” Exactly. Having seen this quick-cut scene only once, the reviewer missed some shots: there’s one of the clerk by the clock, a cut-in to show a bullet-hole appearing in the glass; back to the clerk as he turns; a close-up of the hand taking the bracelet; a close-up of the floor as an incriminating floor is dropped unnoticed; and a view of the crowd outside scattering. It’s a flashy scene, but von Sternberg’s build-up of conversation scenes from close views is just as confident.

The plot is relatively simple, dealing with a love triangle that develops between gangster “Bull” Weed, the reformed drunkard, “Rolls Royce,” whom he takes on as his right-hand man, and Bull’s girlfriend “Feathers.” (Rolls Royce, Feathers, and their photogenic hats at left.) Von Sternberg tells his story visually, stringing together close-ups that convey the action, close-ups not just of faces but of telling details or gestures that capture the essence of a scene. His editing makes not only for clarity and efficiency, but often for vividness and excitement as well. A contemporary reviewer rightly singled out the virtuoso scene of Bull stealing a bracelet for Feathers: “The jewelry-store hold-up is done in four flashes: a pistol shot smashes a clock set above shelves full of silver; a frightened clerk turns; a hand scrapes diamonds from their cases; a crowd is seen through the store’s plate-glass window … This kind of incisiveness, this giving of the part for the whole, when used imaginatively, not spottily or as a trick, is a method exactly suited to the screen, and one little used.” Exactly. Having seen this quick-cut scene only once, the reviewer missed some shots: there’s one of the clerk by the clock, a cut-in to show a bullet-hole appearing in the glass; back to the clerk as he turns; a close-up of the hand taking the bracelet; a close-up of the floor as an incriminating floor is dropped unnoticed; and a view of the crowd outside scattering. It’s a flashy scene, but von Sternberg’s build-up of conversation scenes from close views is just as confident.

Von Sternberg was obsessed by light, and he was as skilled as anyone who ever worked in Hollywood at “painting” his compositions with the arrangements of lamps, scrims, and reflectors on the set. Today he is remembered most for having used that skill in a series of films he made with Marlene Dietrich, starting with The Blue Angel (1930) and continuing in six more star vehicles made in Hollywood, including Morocco (1930) and Shanghai Express (1932). Dietrich would never again look as radiant once she and von Sternberg parted ways. But even before he discovered her, von Sternberg was applying his artistry to far less glamorous actors, in this case George Bancroft, whom the director cast in three silent films and his first talkie, the eccentric but wonderful Thunderbolt (1929).

Apart from being a beautifully made film, Underworld introduced the basic conventions of the gangster genre as we think of it today. There had been plenty of movies including gangsters before 1927, but they were typically the villains. Some films followed the police’s efforts to track down gangsters. Many centered on women unknowingly becoming engaged to a gangster or trying save a relative from blackmail or from becoming a gangster. A very common plot device was to have a heroine’s boyfriend falsely accused of a crime committed by gangsters. None of these films actually made a gangster into the protagonist. With “Bull” Weed, the notion of the “good-bad” man, the sympathetic criminal that William S. Hart had popularized in Westerns, came into the gangster genre. Part of the credit for helping to define the genre goes to the great Ben Hecht, whose original screenplay received Underworld’s only Oscar in the first year those awards were given. (Amazingly, it was not nominated in any other category, even cinematography.) Still, von Sternberg altered the script considerably, much to Hecht’s disgust, and it’s hard to gauge the relative contribution of either man. The later memorable characterization of gangster protagonists by Jimmy Cagney (Public Enemy, 1931, and others), Paul Muni (Scarface, 1932, the plot of which distinctly echoes that of Underworld), and Edward G. Robinson (Little Caesar, 1930) follow directly on from the model created by Underworld.

In a 1968 Swedish television interview (included as a supplement in the Criterion set), von Sternberg admits to having known nothing about gangsters. He gave, he says, “a poet’s idea of gangsterism.” Just one case in point, a close-up of a kitten and some lace curtains as a bullet shatters the glass:

The cracks around the bullet hole echo the patterns in the lace curtains, and the juxtaposition of the fluffy cat and diaphanous cloth emphasize the hardness of the glass and the bullet that pierced it.

The disc also contains a straightforward, informative supplement by Janet Bergstrom, who discusses how von Sternberg’s various failures in the mid-1920s led B. P. Schulberg initially to assign him only to co-direct Underworld. He would look after the visuals and someone else would handle the dramatic action. Fortunately that someone never got hired, and von Sternberg directed the whole thing. He turned out to be an adept director of actors as well, allowing Bancroft, Clive Brook, and Evelyn Brent to create considerable sympathy for three characters involved in a very simple plot.

This film was as much a star vehicle for the highly respected German actor Emil Jannings as it was another opportunity for von Sternberg to polish his style. He plays a Russian general in the Civil War that eventually ended with the Bolsheviks in control. A few years later the general is in exile in Los Angeles, eking out a living as a film extra. It was one of the films that brought Jannings the first Oscar for Best Actor. (Actors could be nominated for multiple films in those early days; Jannings’ other performance was in the lost Way of All Flesh.) Clearly von Sternberg was primarily intrigued by the irony of the central situation: the young revolutionary whom the general had earlier imprisoned (William Powell) is now the director of the film in which he is to play a bit part. The film’s visual style is far less distinctive than those of the other two films in the set.

The long central flashback takes place in Russia, and the historical interior sets for the general’s scenes are conventional Hollywood, big and brightly lit. There are a few atmospheric shots of revolutionary mobs running through the streets at night, but the look is no different from what would expect any such scene in a Hollywood film to look.

The films that had brought Jannings to stardom in the U.S. were The Last Laugh and Variety, and the story line in The Last Command is somewhat similar. A powerful, happy man is abruptly brought low, though here the fall into suffering is far greater. Jannings starts out as a close relative of Tsar Nicholas II and ends, complete with a nervous tic in his face, as an extra, passive in his despair and bullied by the other extras. Ultimately the ex-revolutionary film director has his revenge by forcing the old man to re-enact his old role as a general in a combat scene.

The lengthy final sequence where this revenge is accomplished is the most realistic depiction of studio filmmaking in the late silent period that I have ever seen. We see the two cameras, one for the domestic negative, one for the foreign one. Grips assemble platforms and push big arc spotlights around the set. Earlier, in the opening scene, the Jannings character endures the highly routinized process of obtaining various bits of costume and putting on his makeup.)

The lengthy final sequence where this revenge is accomplished is the most realistic depiction of studio filmmaking in the late silent period that I have ever seen. We see the two cameras, one for the domestic negative, one for the foreign one. Grips assemble platforms and push big arc spotlights around the set. Earlier, in the opening scene, the Jannings character endures the highly routinized process of obtaining various bits of costume and putting on his makeup.)

The film leaves little doubt as to where its sympathies lie in the political conflict at its center. Evelyn Brent plays another revolutionary. Captured by the imperial army, she becomes the general’s mistress to save herself from prison, but she eventually falls in love with him and enables him to escape a lynching by the Reds. By the end, even the bitter, contemptuous director has to admit that the nobly suffering extra was a great man. It’s interesting, by the way, to see Powell playing cold and bitter rather than his usual later urbane and witty persona, and the contrast shows what a fine actor he was.

Though a very worthwhile and skillfully made film, The Last Command ultimately falls short of being on a level with Underworld and The Docks of New York. For one thing, the characters are not nearly as sympathetic as in those two films. Brent and Powell play standard-issue grim revolutionaries, at least until Brent’s character succumbs to love. It’s not clear why they change their minds so radically about the general, given that he is mainly seen having protesting workers mown down, going through show inspections of the troops, and taking advantage of his power over the captive Brent to make her his mistress. Perhaps in an era when the fall of Czarist Russia was deplored and Hollywood saw many exiles looking for work, Jannings’ general could be seen as a tragic figure. To the modern eye, the portrayal of imperialist Russia makes the doomed government seem no better than what was to follow.

The Last Command survives in a somewhat soft print compared with the clarity of the two other films.

The Docks of New York

Even more than Underworld, The Docks of New York is a film where almost any shot could yield a dramatic frame enlargement. I’ve made some difficult choices and whittled it down to a few. Let’s just say that it involves a lot of smoke, as in the image immediately below, showing stokers in the engine room of a ship, and a lot of fog, as in the one below it, showing the protagonist’s sidekick looking for him once they’ve gone ashore. Von Sternberg’s well-known predilection for placing elements of the set in the foreground to enhance the composition comes through in both frames. For more fog see the image at the end of this entry.

The film’s story is even simpler than that of Underworld. A Stoker who spends his life at sea with occasional days ashore at various ports save the life of a Girl trying to commit suicide near a seedy dockside tavern. (None of the main characters is given a name.) As she recovers, the pair get to know each other a little. She is presumably a prostitute, he a drifter with, as his tattoos show, a girl in every port. He offers to marry the Girl, and the ceremony takes place in the bar to the amusement of the drunken crowd looking on. The Girl is filled with hope, but the Stoker heads out to sea the next morning. Will he change his mind, or will she despair and successfully drown herself on the next attempt?