Archive for the 'Directors: Welles' Category

When Hollywood ruminates: Calm after THE MORTAL STORM

The Mortal Storm (1940).

DB here:

We don’t usually think of classic studio cinema as particularly contemplative. But many films open up spaces for quiet reflection on what we’re seeing, or have seen. In the 1940s, that tendency owed a good deal to the ways that Hollywood became, to put it roughly, more novelistic.

Movies had been based on novels for many decades, but in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, I claimed something more specific. I think that many 1940s filmmakers became more acutely aware of sound film’s capacities for manipulating time and point of view. These are novelistic techniques par excellence, distinctly different from the largely “theatrical” conceptions of presentation that we find in most studio cinema of the 1930s. Films turned inward, probing perceptions, memories, and dreams. If you need a storytelling twist, one journalist cracked, just call it psychology, and it will get by.

Of course, there are plenty of precedents for time and POV shifts in early decades. Still, I wanted to show that between 1939 and 1952 many major options emerged and were developed in ambitious directions. The results left a legacy. Today, when flashbacks are common and we easily grasp elaborate shifts in viewpoint, our films rework the possibilities refined and consolidated in the 1940s.

One stretch of the book considered some films from early-to-mid 1940 that offered glimpses of innovations we’d see in later years. Married and in Love, One Crowded Night, Stranger on the Third Floor, and Edison, the Man previewed techniques that would dominate the next decade. Particularly chock-full of storytelling ideas, I argued, was Our Town, a daring transposition of 1930s theatrical devices into the key of cinema.

Missing from my roster, though, is The Mortal Storm, a film that went into release in June of 1940. I had neglected to rewatch it when writing the book. A couple of weeks back I caught up with it during a screening at our Cinematheque. Restored by UCLA, it fairly shimmered off the screen.

How could I not have remembered the stunning closing sequence? It’s a bundle of narrative strategies that would get elaborated in the years to come. And it achieves its effect from being somber, slow, and based on human absence. In this epilogue, the movie pauses to think.

To talk about this passage and its counterparts, I have to parade plenty of spoilers. Sorry. But at least you get video.

Emptying the nest

The Mortal Storm.

The plot starts in Germany at the moment of Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933. Elderly Viktor Roth is a much-loved Jewish professor of medicine. His household includes his stepsons Otto and Erich, his wife Emilia, and their daughter Freya. Two other young men are close to the family: Fritz, who aspires to marry Freya, and Martin, a farm boy training to be a veterinarian.

Otto, Erich, and Fritz become enthusiastic Nazis, but Freya draws closer to Martin, who quietly resists the growing bigotry in their small town. Professor Roth is arrested and killed. Martin and Freya, now deeply in love, try to escape by ski to Austria. A squad of soldiers, under Fritz’s direction, fires on them. Freya is killed.

In the crucial scene, Fritz returns to the family home to tell Otto and Erich.

The sequence blends several narrational choices. Most obvious is the camera movement that seems to drift off on its own. It is, we might say, semi-subjective. It suggests Otto’s slow walk through the now-empty home, but it isn’t clearly marked as his optical POV. The opening stretch of the shot shows him pacing more or less obliquely to us, before the camera pans and tracks to the table and beyond.

The framing insistently keeps Otto offscreen. Only the sound of his footsteps and pauses suggest that he’s present, off left or behind us, at each station of the shot.

As the camera drifts along, we get auditory flashbacks to earlier scenes, three at the table, and one echoing the Professor at his lectern. Flashbacks are characteristic features of 1940s cinema, and purely auditory ones will come into prominence, as in The Fallen Sparrow (1943). Since we’ve seen the action these flashbacks evoke, they’re as much flashbacks for us as for Otto. Indeed, Otto has been a minor character in the story. His walk triggers them, but his absence from the frame makes it easier for us to project our memories onto these spaces.

The transition among the flashbacks prepares for Otto’s defection. The voice shifts from Freya, whose death Otto is grieving, to the men challenging authority. We hear Professor Roth urge youth forward, and Martin advocating peace and free thought. These later moments seem to crystallize Otto’s change of heart. Dwelling a bit on the statuette of Youth carrying the torch of knowledge suggests that Otto may become inspired to take up his father’s commitment to humanism.

At the climax of the shot, the camera frames the staircase (another icon of 1940s cinema) and starts to back up. This can hardly be Otto’s optical viewpoint. The rapid footsteps suggest that he has left the house by striding out, as it were, behind us. The sound of a closing door confirms our inference. He has left us behind.

As he does in the final moments, when Otto’s flight is depicted as footprints in the snow. Perhaps, now that he has become revolted by the cruelty of Fritz and the Nazi regime, he will take up resistance in Martin’s spirit.

Accompanying the shots of the footprints is the voice-over narrator whom we heard at the film’s start. (Such narrators proliferate in 1940s movies.) His speech, from a poem called “The Gate of the Year,” echoes the visuals: a man “at the gate,” the prospect that one may “tread safely into the unknown.” In giving up Nazism, Otto is giving up home.

The camera tilts up to show the empty house. The snow-encased home is quite different from the bustling view we saw at the film’s start, when the postman delivered gifts for Professor Roth.

Hitler has destroyed the family. Still, as the snow buries the footprints, the narrator urges that divine guidance can provide safety for Otto’s escape, and perhaps a decision to fight Nazism.

We don’t normally think of MGM as a hotbed of cinematic innovation in the studio years. But the company had its moments (here and there), and this is one of them. The Mortal Storm‘s play with time (flashbacks, the solemn duration of the house tour) and viewpoint (Otto triggering some bits of remembered dialogue) resembles what we might get in a psychologically slanted novel of the time. We’re given a few minutes to breathe deeply and think about what we’ve seen, and to build up expectations about what Otto may do.

The house as memory vessel

The Miniver Story (1950).

One section of Reinventing Hollywood analyzes Enchantment (1948), a film narrated by a house. The house presents itself as a cozy repository of the memories of several generations. More generally, houses are powerful images in 40s films; think of Tara, Manderly, the estate in Dragonwyck, and the Gothic mansions of Jane Eyre, Gaslight, and The Spiral Staircase. Often they’re presided over by ominous portraits, as Steven Jacobs and Lisa Colpaert have shown.

One lesser-known example is House of Strangers (1949), directed by Joseph Mankiewicz. This story of an Italian immigrant who has become the head of a big bank is framed by his son Max returning to their massive home. The bulk of the film is given in flashback, but the flashback is launched by a wandering camera accompanied by “M’apparti tutt’amor” (from the opera Martha) playing on the phonograph. After a trip up the stairs we are taken via dissolve to the patriarch singing it in his bath.

The plot’s central section treats the lyric (“You all seem to love me”) with doubled implication: Gino’s reckless loans endear him to his customers, but his sons resent his power over them. The long flashback ends at Gino’s funeral, passing from the portrait in the past to the phonograph and to his son Max, brooding under the looming picture.

The huge Minafer mansion is practically a character itself in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). One of Welles’ late script versions envisioned a climax in which George, distraught by the shabbiness of their neighborhood, would pass numbly through the house, and our sense of it would be given through his eyes.

145 FULL SHOT of the Amberson Mansion, seen from behind George who is standing in front of camera. He starts walking toward the mansion. CAMERA FOLLOWS, moving faster than he does and soon is so close to him that his body creates a dark screen for a DISSOLVE TO:

146 CAMERA is on the steps of the Amberson Mansion, MOVING up to the door and STOPPING. George’s hands enter the scene, insert a key in the lock, turn it —

147 On the Narrator’s words, “move out” the door opens and CAMERA MOVES thru it into the house.

MOVING SHOT as CAMERA WANDERS SLOWLY about the dismantled house — past the bare reception room; the dining room which contains only a kitchen table and two kitchen chairs, up the stairs, close to the smooth walnut railing of the balustrade. Here CAMERA STOPS for a moment, then PANS down to the heavy doors which mask the dark, empty library. HOLD on this for a short pause, then CAMERA PANS back and CONTINUES, even more slowly, up the stairs to the second floor hall where it MOVES up to the closed door of Isabel’s room. The door swings open and we see Isabel’s room is still as it always has been; nothing has been changed. FADE OUT

This passage is strikingly similar to what we see in The Mortal Storm. True, the cues for George’s optical viewpoint are more explicit than what Borzage gives us for Otto. But Welles is subtler along another dimension. He counts on our remembering earlier scenes without benefit of auditory flashbacks. The camera revisits the reception area we saw during the ball, the dining room where George challenged Eugene Morgan, and the staircase where George and Fanny quarreled, before coming to rest in Isabel’s room, where we saw her waste away and die. We are asked to supply our own flashbacks.

Some of this POV passage might have been filmed, but it wasn’t retained in Welles’ final version, even before RKO’s mangling. In the film as we have it, only Welles’ lead-in and conclusion remain. The narrator supplies a moving-camera montage, as George registers the changes in Amberson Avenue.

The street sequence ends in darkness and tracks back from George kneeling at the bed begging forgiveness. The fact that the shot starts from his darkened head reinforces the subjectivity of the montage.

Welles’s handling is novelistic in the sense of wrapping a character’s flowing impressions inside an omniscient verbal commentary using free indirect discourse (“Tomorrow they were to move out”). George’s moments of rueful meditation are moments for us as well.

Like the narrator that closes The Mortal Storm, this voice is external to the story world. But the same house-haunting effect can be achieved by a narrator who lives in that world. Coupled with the wandering camera, this can turn our view of a scene in the present into a view of the past–or of an eternal future.

The example I have in mind is from The Miniver Story (MGM again, 1950). In Reinventing, I analyze a sequence that creates layers of time: Clem Miniver’s voice-over in our present, an image of he and Kay in the past, and references in the commentary to periods still earlier than what we see. (The clip of this sequence is online here.) At the end of the film, after the Minivers have married off their daughter Judy to Tom, they must face Kay’s impending death from cancer.

The final sequence shifts from the day of the wedding to a kind of timeless realm in which Kay’s spirit lives on. Again, camera movement suggests an invisible presence.

By 1950, we’ve had several permutations. The camera wanders without verbal narration (music alone in House of Strangers). It does so with auditory flashbacks (The Mortal Storm). It does so with a nondiegetic (external) narrator (The Magnificent Ambersons). And it does so with a diegetic (story-world) narrator (The Miniver Story). I try to show in the book that 1940s filmmakers swiftly expanded, even exhausted, menu options involving many storytelling techniques.

Trust Hitchcock to give us yet another variant, and in a tour de force at that.

Enough rope

In the eleven shots of Rope (1948), set almost completely in an apartment, the camera’s peregrinations are usually motivated by character movement or simple track-ins and track-outs. At the climax, though, the camera cuts loose. Sort of.

Brandon and Phillip have strangled their friend David and hidden his body in a chest in their living room. They’ve ghoulishly used the chest as a buffet table for their afternoon party. After the party, one guest, their prep school teacher Rupert Cadell, has returned. He suspects that something bad has happened to David. Rupert challenges the pair and sketches out how they might have murdered their friend.

His reconstruction isn’t wholly correct. David wasn’t bludgeoned, and apparently the armchair played no role. What’s fascinating is that the camera supplies a hypothetical, virtual flashback. As in our earlier examples, David becomes an invisible guest, summoned up by the mobile frame.

The camera traces out the action Rupert posits, emphasizing the hall closet (where Rupert earlier discovered David’s hat) and edging eventually toward the chest. At that point Brandon steps in, with his hand tensing around the pistol in his pocket. He stands in front of the drinks table.

That’s the climax of the shot. Cut to a shot of Rupert. He seems to intuit that he should avoid mentioning the chest, so he proposes that they might have carried the body out of the building. As the camera traces out that possibility, Brandon steps back into the frame to confront Rupert.

Here I think Hitchcock made a mistake. At the end of the first shot, Brandon and his pistol are quite close to Rupert, near the drinks table. But in the followup shot, he’s not visible when the camera pans left past the table to enact the scenario Rupert is considering. Brandon would have had to skip backward like the Road Runner to get as far away as he is when he steps back into the frame in the second shot.

Still, the important effect is the representation of Rupert’s thinking. Goaded by Brandon, he ponders how the crime might have been committed, and the camera carves into space to reveal the scheme he conjures up. A sort of flashback? Yes, but an unreliable replay, left largely to our imagination. Semi-subjective? Yes, since when we cut to Rupert he seems to be staring down at the chest. Yet the camera is too free-ranging to be purely Rupert’s optical POV. He’s not moving around, as Otto is in the Mortal Storm sequence.

In this most “theatrical” of movies, Hitchcock manages to give us a verbal-visual flow that is something like a cinematic equivalent of the novelist’s conditional perfect tense. If Brandon and Phillip had killed David, they could have done it this way. The camera enacts a speculative train of thought. Call it psychology.

One thing I shouldn’t ever forget: Hollywood in the Forties is a booming rush of visual, auditory, and narrative ideas. In the approximately 5,655 features released in the period I marked off, there are surely many other startling instances of creative craft. I’ll keep looking.

Thanks as ever to our Wisconsin Cinematheque for fine programming under the auspices of Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser and excellent projectionist Roch Gersbach. Thanks as well to Joe McBride for sharing material on The Magnificent Ambersons. More on Ambersons can be found here and here.

The Mortal Storm‘s “novelistic” final moments owe nothing to its source, Phillis Bottome’s The Mortal Storm (1938). An earlier version of my ideas about Enchantment are here.

Chapters 4 through 6 of Patrick Keating’s The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood offer a careful survey of creative choices facing filmmakers of the period, along with explications of their “practical theories” about cinematography. After writing this entry, I learned that Patrick has also made a fine video essay on the Ambersons sequence.

For earlier blogs on related subjects, see the category 1940s Hollywood.

PS 2 March 2020: Patrick Keating reminds me of another 1940 release I should have mentioned: Hitchcock’s Rebecca. When Maxim narrates his confrontation with Rebecca, the camera moves autonomously to “replay” the scene. It anticipates my Rope example, except that Maxim is recounting what really happened, while Rupert is sketching out his (partially inaccurate) reconstruction of David’s death. Still, though, it’s another variant on an emerging pictorial convention. Thanks, Patrick!

PS 2 March 2020, later: Thanks also to John Belton, who writes to remind me not only of the Rebecca scene but a comparable camera movement in Under Capricorn. Crowdsourcing works.

Rope (1948).

Cine-Vienna

The Third Man (1949).

DB here:

En route to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, Kristin and I paid a visit to this wonderful city. We wandered around, stomped through museums, ate tasty food, and saw a bit of the city’s film culture.

Visiting venues

Our first stop was the Austrian Film Museum. Founded in 1964 by the avant-garde filmmaker Peter Kubelka, the Museum has built up a collection of over 30,000 films. It contains a fine film theatre with features of the “Invisible Cinema” (above) that Kubelka and Jonas Mekas set up in Anthology Film Archive many years ago.

The Museum has been a pioneer in producing outstanding books and DVD editions devoted to an eclectic array of filmmakers (James Benning, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Straub/Huillet, Joe Dante). Exceptional as well are the Museum’s online offerings of films, clips, images, and paper documents.

Our host was our old friend, the ebullient curator Christoph Huber. Here he is with his colleagues Alexandra Thiele and Jurij Meden.

We didn’t have a chance to visit the classic Stadtkino in the same neighborhood, nor did we check out the highly esteemed Austrian Film Archive. But I did mosey down to the Gartenbaukino, a big, beautiful modernistic venue.

Built as a ballroom that occasionally screened films, the Gartenbau was made a permanent cinema in 1919. In 1960, after being redesigned by Robert Kotas, it opened as a showcase for widescreen motion pictures.

It’s now said to be the biggest theatre in Austria, with over 700 seats. Note the rising curtain, said to be a rarity these days.

The Gartenbaukino is equipped to project not only digital and 35mm but also 70mm. Managing Director Norman Shetler notes that it was the first Austrian theatre to boast large-format projection (for Spartacus) and was adapted for Cinerama as well.

More recently, the Gartenbau reactivated its 70mm equipment to show The Hateful Eight. The Phillips DP70 projectors now screen wide-gauge classics like Lawrence of Arabia and The Sound of Music. Picture and sound were excellent for The Dead Don’t Die, so I bet 70mm shows here are fantastic. Like the Stadtkino, the Austrian Film Archive, and the Film Museum, the Gartenbau is a venue for the city’s annual film festival, the Viennale.

Prater, not so violet

Plenty of movies have been set in Vienna, most notably The Joyless Street, Merry-Go-Round, Letter from an Unknown Women, and Amadeus. But for movie nerds the most flagrant example is The Third Man (1949). And Vienna hasn’t forgotten what this movie did for its local landscape, not least the amusement park set within the vast and beautiful park known as the Prater.

Said to be the oldest amusement park in the world, the Prater ‘s entertainment sector contains attractions that are shiny and enjoyable old-school rides: roller coaster, loop-the-loop, tilt-a-whirl, haunted house. There are shooting galleries, ice-cream stands, and even a Madame Tussaud’s.

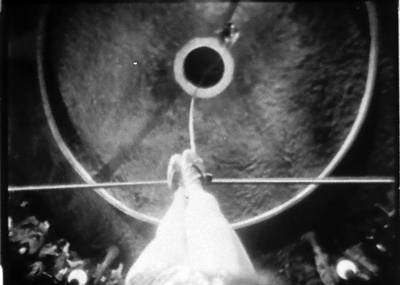

But of course the looming attraction is the great Ferris wheel that Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and Harry Lime (Orson Welles) share during their ominous reunion. I’m sure I’m not the only viewer who always expects Harry to try to throw his old friend out of the cabin.

The big wheel has been declared a site of European film culture and decorated with a more or less accurate image of the coy Lime.

My ride in the wagon was gentle and elating. I tried to replicate Harry’s POV on the “ants” below, whose lives, he says, can’t matter much.

A studio-based version of the Prater featured in the now mostly lost Josef von Sternberg film, The Case of Lena Smith (1929).

Oh, yeah–we also paid a visit to a street named for one of my favorite auteurs. See below.

Next up: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

For information about Viennese film culture, thanks to Christoph Huber, his colleagues, and the indefatigable Ted Fendt. Thanks as well to Norman Shetler and two staff members at the Gartenbau cinema. Christoph, by the way, is an exceptional critic. You’ll learn from reading his essays in Cinema Scope.

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Artisans and artistry

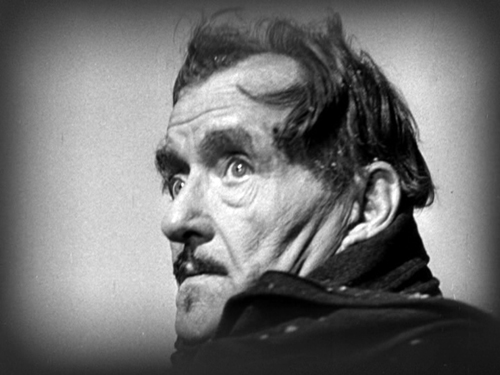

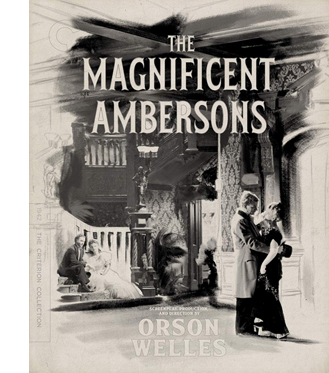

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942). Production still from lost scene.

DB here:

This is the third blog entry amplifying on the paperback edition of Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. This mini-series tries to enhance the book’s arguments by taking into account books and DVDs that have come out since the hardback publication in 2017. (Previous entries are here and here.) Today I want to talk about what T. S. Eliot called “tradition and the individual talent” in a realm Eliot would disdain: American studio cinema.

Curtiz, pronounced Cur-tess

Noah’s Ark (1928).

Reinventing Hollywood offers itself as an alternative to two major ways of understanding the films of a period. One angle is to see creativity flowing from gifted filmmakers. The story often concentrates on how they have to struggle against the constraints of the film industry. In the Forties, Orson Welles would be a prime instance, though Preston Sturges and others could also be invoked. Without denying the talent and originality of key filmmakers, and without neglecting the stubborn ignorance of many executives, I wanted to show that in many ways creativity can be enabled by the conditions of the industry.

Genre is an obvious instance. Without the Western, where would John Ford be? The musical brought out the gifts of Minnelli and Donen, just as the crime film spurred Huston and Anthony Mann. I wanted to suggest that filmmakers were challenged to work with other normative factors than genre—factors centering on how stories were told. Writers and directors collectively amassed a menu of narrative options, from flashbacks to voice-overs, that got quite refined in the course of a dozen years or so.

Some sympathetic readers have considered the book anti-auteurist because I emphasize those pooled resources that any filmmaker, weak or strong, could draw upon. To some extent, that’s right: stretches of the book resemble “art history without names.” Tony Rayns warned readers that they should read Reinventing Hollywood with Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide at hand.

Not a bad idea. A single paragraph compares A Child Is Born (1940), One Crowded Night (1940), Busses Roar (1942) and Dial 1119 (1950). None of them is exactly a lustrous classic, and I didn’t mention the directors or the screenwriters. My main point is that these films play out variants of the Grand Hotel plot, and they show how even artisans can take the opportunity to revamp current norms.

So for my project, creators of whatever rank matter. In the course of my research, it struck me that three “creative producers”–Hal Wallis, David O. Selznick, and Darryl F. Zanuck–are as important as many directors. The same goes for screenwriters, such as Casey Robinson, Vera Caspary, and Ben Hecht. And now that we have biographies of Victor Fleming and William Wellman, we’re starting to understand the importance of skilled directorial artisans. I’ll take even so-so craftsmen (and craftwomen) if they can teach us secrets of Hollywood carpentry. Charles Lang and Walter Lang are no Fritz Lang, but they made more popular films, and we can study the ways they instantiate filmmaking norms.

So for my project, creators of whatever rank matter. In the course of my research, it struck me that three “creative producers”–Hal Wallis, David O. Selznick, and Darryl F. Zanuck–are as important as many directors. The same goes for screenwriters, such as Casey Robinson, Vera Caspary, and Ben Hecht. And now that we have biographies of Victor Fleming and William Wellman, we’re starting to understand the importance of skilled directorial artisans. I’ll take even so-so craftsmen (and craftwomen) if they can teach us secrets of Hollywood carpentry. Charles Lang and Walter Lang are no Fritz Lang, but they made more popular films, and we can study the ways they instantiate filmmaking norms.

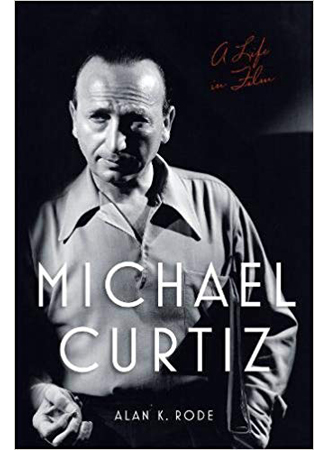

Then there’s Michael Curtiz.

Andrew Sarris claimed that “Curtiz reflected the strengths and weaknesses of the studio system,” and most writers have agreed. Although Curtiz is mentioned by name only twice in Reinventing Hollywood, I draw examples from ten of his films, from Four Daughters (1938) to Young Man with a Horn (1950). I devote most space to Passage to Marseille (1944). Mildred Pierce (1945) is absolutely central to the book’s arguments, but as I’ve written about it before, both in print and online, I didn’t rehash my argument in the book.

Which is to say, I guess, that Curtiz exemplifies what I was analyzing. He was a master craftsman who has a lot to teach us about norms, both inside and outside Hollywood.

Alan K. Rode’s biography, Michael Curtiz: A Life in Movies, focuses on the man and his accomplishments, and it paints a vivid portrait of a director of intense creative and sexual appetites. He also liked polo. Drawing on memos, production records, and memoirs published and unpublished, Rode provides brisk, telling background on dozens of films. He dwells, as you’d expect on the milestones: Noah’s Ark, the early 30s horror films like Dr. X, Angels with Dirty Faces, Yankee Doodle Dandy, Casablanca, and the Flynn vehicles. But he doesn’t neglect the fleet-footed programmers like The Kennel Murder Case (1933) and The Case of the Curious Bride (1935), projects enlivened with fancy angles, propulsive pace, and bold tracking shots.

On-the-set anecdotes keep things lively. Rode is careful to debunk some of the most famous stories, but he leaves a lot of good ones in. His conversational style is likewise engaging. He compares Peter Lorre to “a sinister kewpie doll” and calls Alexis Smith lissome, using a word I had forgotten exists. Although Rode isn’t as interested in the questions I pursued, his book set me thinking about creativity in the studio system. Specifically, we can broaden our view of Curtiz’s career, which ran from 1912 to 1962, and see it as encapsulating some major trends in commercial entertainment cinema, inside Hollywood and out.

Starting well before DeMille, Ford, Hitchcock, Hawks, Walsh, and other Hollywood auteurs, he was initiated into the standard tableau style of the 1910s. Fairly distant shots in long takes relied on deep sets, staging and performance. Cutting was used principally to shift the scene, show adjacent locales, or occasionally enlarge a detail. The Undesirable of 1914 (available in a stunning restoration distributed by Olive) shows fairly orthodox choreography of figures in depth and across the frame, with foreground figures masking irrelevant background action.

Apart from Lubitsch and DeMille, most of the directors who had long careers in the studio system didn’t come out of tableau cinema. They began by practicing the rapid editing and close-up framings that emerged in America in the mid-1910s. Curtiz was more or less up to speed with them in his stupendous Viennese production Sodom und Gomorrha (1922, available on a well-restored DVD version). He breaks up vast shots with axial cuts, close-ups, and occasional reverse angles. This nutty film, surely one of the biggest productions of the day, used kitschy modern sets for the contemporary story, expressionist ones (with cadaverous jailers) for dreams, and gigantic pseudohistorical ones for Biblical bacchanals.

His first American film, The Third Degree (1926), tries to bring into Hollywood some fashionable European stylization. Curtiz showcases flashy camera movements, rapid rack-focusing, swift montage, and distorted subjectivity reminiscent of French Impressionist cinema. The specific reference is Dupont’s Variety (1925). Curtiz’s tightrope shots mimic Dupont’s trapeze angles, and prismatic superimpositions of eyes during the cops’ third degree recall the swirl of the spectators’ eyes in Variety.

When a detective drops down to investigate a clue, Curtiz doesn’t hesitate to cut to a skewed view framed by the arm and leg of his crouching colleague.

Much of Noah’s Ark (1928) uses standard silent-film continuity style, although Hal Mohr’s lighting sparkles even more than in The Third Degree. Curtiz’s opening montage relies on wide-angle compositionssof a type resembling images in Murnau’s late silent pictures. Here we dissolve from Biblical worshippers of gold to modern stockbrokers, and the dense packing of figures recalls William Cameron Menzies’ work of the same period.

But Curtiz’s most flamboyant effects are reserved for the spectacle, especially in the preposterously vast flood scenes with devastation that recalls the rain of fire in Sodom und Gomorrha.

In his sound pictures Curtiz was less outré, but he never lost his taste for momentary flourishes. Anybody who starts a film called The Keyhole (1933) by moving the camera through a keyhole gets points from me.

Curtiz made his name as a master of crowd effects, and he didn’t shrink from handling groups in tight interiors. A hotel-suite party in Kid Galahad (1937) runs thirteen minutes and is packed with movement. The first shot starts on a phonograph, two abandoned drinks, and a carelessly smoldering cigarette–details indicating a wild party, and setting up the importance of serving drinks in the scene to come. Tilt up to a mirror that hints at a space we’ll soon visit.

The next shot launches a leftward track across two rooms, motivated by a damsel’s wild shimmying. People are packed into the foreground and distance. In the next room the dancing woman carries us to card players before we settle on the fight promoter played by Edward G. Robinson, who calmly gets a haircut amid all the revelry. (After all, the party has lasted three days.)

As these Kid Galahad shots show, Curtiz favored low angles and moderately wide-angle lenses to jam his figures together. In the party scene, he multiplies setups freely, almost never repeating one exactly. (Compare the slightly different framings of the second and third image.) The confrontation of two prizefight gangs is played out in a tricky mirror shot.

By comparison, W. S. Van Dyke’s handling of an apartment party in The Thin Man (1934) looks timid.

Watch Four Daughters (1938) and Four Wives (1939) to see how adroitly you can choreograph a big bunch of people strewn around a parlor. In the first film, Curtiz never lets us forget the defensive outsider Mickey (John Garfield), disturbed by this loving household and shielding himself behind the piano. Some might say that Curtiz’s use of “distant depth” is less heavy-handed than Welles’ in-your-face foregrounds in Kane, three years later.

Rode shows how Curtiz managed to control his films while shooting. From the start, in The Third Degree, he freely added scenes to the script. Thereafter, producer Hal Wallis railed at his “overshooting” with more angles than most directors would use, and he added props and actors without permission. Hawks, Hitchcock, and Ford would work uncredited on the screenplay, but Curtiz simply changed the script on the fly. As he gained more authority, he prepared new dialogue and business at night with his wife Bess Meredith.

Often over budget and schedule, constantly berated by his bosses, Curtiz got away with it all because the films were usually successful and critically acclaimed. Besides, the complaints usually came too late; he was already at work on the next movie. In some years he turned out six features. He’s a good example of a how a vigorous Hollywood artisan could leverage the system through both craft and craftiness.

Wellesapoppin’

I can’t foreswear auteurs altogether. Reinventing Hollywood does spare some time for Preston Sturges, Mankiewicz, Hitchcock, and a few others.

Notable among those is Orson Welles, who threads through my story. Citizen Kane helped popularize flashback narrative for A-pictures, and I argue that its use of the device blended several options that had floated around in the years just before. In the chapter on Hollywood’s efforts to interpret its own traditions, Welles and Sturges come forth as proto-film-geeks citing film history. The Magnificent Ambersons is imbued with a nostalgia for silent films. There’s the edge-vignetting on the early scenes (above), the famous iris that closes the snow idyll, the final credits showing the players more or less addressing the viewer, and the very geeky posters I illustrate in this entry and those leading up to it. The now-lost scene on the veranda with George, Aunt Fanny, and Isabel, shown at the top of today’s entry, included a vision of Lucy appearing to George “in transparency (the shadowy ghost figure from the silents).”

Most extensively, Reinventing discusses Welles and Hitchcock as directors who shaped 1940s storytelling conventions and then had to respond to others’ use of them. I’m again trying to set auteurist claims in a wider context, that of a flourishing ecosystem of creative choices. Just as important, both directors continued using 1940s strategies throughout their later careers. Welles’ importation of Theatricalist stage theory into film, along with his reliance on flashbacks, voice-over, and embedded stories, are central to his later work.

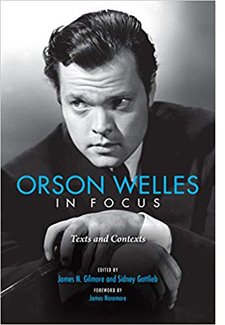

Research on Welles never stops, and so I’m happy to welcome new developments. There’s of course the rehabilitation of The Other Side of the Wind, which features flashback construction, films-within-the-film, voice-over, and other preferred Wellesian tactics. Now we also have Orson Welles in Focus, edited by James N. Gilmore and Sidney Gottlieb, with an introduction by James Naremore.

Research on Welles never stops, and so I’m happy to welcome new developments. There’s of course the rehabilitation of The Other Side of the Wind, which features flashback construction, films-within-the-film, voice-over, and other preferred Wellesian tactics. Now we also have Orson Welles in Focus, edited by James N. Gilmore and Sidney Gottlieb, with an introduction by James Naremore.

It’s a set of papers from a 2015 centenary conference on Welles at Indiana University, and they’re all stimulating and wide-ranging. Margaret Rippy reveals the roles of Asadata Dafora and Abdul Assen in collaborating with Welles on the 1936 Macbeth, while Catherine L. Benamou, an expert on It’s All True, shows how the episodes open up different options for transcultural critique in the documentary mode. Welles’ 1946 Broadway musical Around the World gets careful consideration by Vincent Longo, who intriguingly relates it to Bazin’s contemporaneous reflections on theatre and film. François Thomas incisively exposes the financial and legal tangles around Mr. Arkadin (1955).

Welles the fighting liberal gets important attention in two essays. Sidney Gottlieb, who has been assiduously collecting Welles’ writings for years, surveys the director’s journalism for The New York Post. Similarly, James N. Gilmore scrutinizes Welles’s 1946 correspondence, where he continued to denounce racism and antisemitism.

The two essays most relevant to Reinventing Hollywood touch on Welles as cinephile and Welles as storyteller. Matthew Solomon provides a detailed account of Welles’ love of “old-time movies.” Solomon is especially enlightening on Welles’s fondness for citing films made before his birth, as if there he found the most powerful images of “pastnesss.” Shawn Vancour traces how Welles’ use of first-person narration in the 1938 War of the Worlds broadcast develops norms of radio storytelling that were emerging at the moment. Using manuals for radio scriptwriting, Shawn shows that Welles’ shifts between present and past, first-person and third-person narration became common in the years that followed. Both of these essays enrich points I tried to make in my book.

Then there’s that triumph of modern DVD publishing, Criterion’s long-awaited version of The Magnificent Ambersons. A gorgeous transfer is accompanied by a booklet of discerning essays by Molly Haskell, Luc Sante, Geoffrey O’Brien, Welles himself (on his father), and Farran Smith Nehme (on Welles’ speaking voice, which definitely deserves analysis).

On the AV bonus front, producer Issa Clubb has wisely retained many items that made the company’s pioneering 1986 laserdisc release a demo of what that format could deliver. We get Robert Carringer’s sensitive voice-over commentary, an audio recording of Welles’ radio adaptation of Tarkington’s novel, some interview bits of Welles discussing the film, and the remaining clips from Pampered Youth (1925), an earlier adaptation of the book.

On the AV bonus front, producer Issa Clubb has wisely retained many items that made the company’s pioneering 1986 laserdisc release a demo of what that format could deliver. We get Robert Carringer’s sensitive voice-over commentary, an audio recording of Welles’ radio adaptation of Tarkington’s novel, some interview bits of Welles discussing the film, and the remaining clips from Pampered Youth (1925), an earlier adaptation of the book.

We’ve unfortunately lost Carringer’s visual essay on the film’s style, and Welles’ storyboards and shooting script, rendered in that single-frame technology that made CAV discs clunkily hypnotic. But the new material more than compensates. Clubb has turned a treasure chest into a cornucopia.

We get a second Mercury Theatre radio play, this one based on Tarkington’s Seventeen. A second audio commentary track, featuring James Naremore and Jonathan Rosenbaum, finds illuminating new things to say about this all-but-masterpiece. I also learned an enormous amount from François Thomas’s essay on the mix of cinematography styles in the film, which he tracks through daily production reports. Stanley Cortez, whom Kristin and I once interviewed across two fruitless hours, was only one of several DPs working on the movie.

Christopher Husted shows how the careful parallel scenes of the full-length version received delicate scoring by Bernard Herrmann, who took his name off the film when RKO recut it. A panoply of interviews with Welles, Simon Callow, Peter Bogdanovich, and Joseph McBride is sure to interest old fans and newcomers. The story of Ambersons will never grow old, and we’ve made remarkable progress in understanding its intricacies.

Magnificent ruin

Welles went to Brazil at the behest of the US government, to make a film supporting the “Good Neighbor” policy toward South America. Shooting on Ambersons finished in January 1942, and Welles left his notes with Robert Wise, the film editor who was to oversee postproduction. Wise was to bring a draft result to Welles in Rio, where they would fine-tune it. But wartime travel restrictions, and perhaps RKO’s reluctance, kept Wise at home.

In the trade papers, RKO claimed that Welles was fully engaged in finishing and cutting Ambersons in Rio. “Orson Welles So Tireless, Cuts ‘Ambersons’ by Wireless,” ran a rhyming headline in Hollywood Reporter. The first sneak preview was reported as being 2 1/2 hours, a second around two hours, but Robert Carringer in his authoritative study, The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction, has suggested on the basis of production correspondence that the first preview version probably ran about 101 minutes, the second around 117.

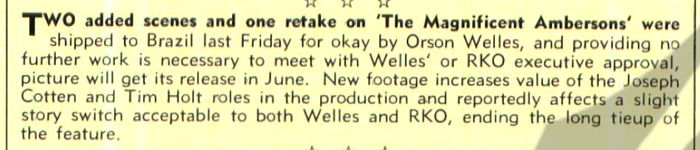

Reacting to harsh audience criticism, Welles’ associates at RKO decided that film had to be cut and new scenes had to be shot. Joe McBride’s Criterion interview explains that the studio had lost faith in the project and was ignoring the detailed instructions that Welles sent by cable. By this time, because of contract renegotiations after Kane, Welles no longer had right of final cut. But RKO continued to claim, as in this 29 April Variety story, that the director was fully on board.

Actually, two weeks earlier, Carringer tells us, studio head George Schaefer had transferred authority over the final cut to Wise.

The studio announced that changes were being made, though they seem never to have been specified. Press releases built on Hollywood’s continuing dislike of the boy genius. One story was put out that Welles had demanded that Joseph Cotten send him “weekly shipments of Chinese dishes” by air, as if defying wartime privation.

Ambersons had been planned as a “special” alongside other big RKO-distributed titles (The Pride of the Yankees, Bambi), and aiming at an Easter release. Instead, it was eventually absorbed into a block of titles, which was the standard way of packaging A and B pictures together. The recutting pushed the film’s release into the doldrum days of summer, the graveyard for second-tier product. After a July debut in Los Angeles, it didn’t appear in New York until August. Box office was initially good in some venues, but nothing compared to the big hits of 1942: Mrs. Miniver ($5.4 million in rentals), Yankee Doodle Dandy, Random Harvest, Reap the Wild Wind, Holiday Inn, The Road to Morocco, The Pride of the Yankees, and Wake Island.

A quick sampling of newspapers around the country shows that into the fall, the film sometimes appeared alone on a program (even in La Crosse, Wisconsin). Elsewhere it seems to have been the top of a double bill that includes such items as Syncopation, Her Cardboard Lover, Little Tokyo, USA, Ellery Queen’s Desperate Chance, and most notoriously, Mexican Spitfire Sees a Ghost.

Was it Ambersons that sank Welles’ future? Some have said so. According to a 1952 record of RKO profits and losses across the studio’s history, the film was claimed to have lost $620,000. Before that, only Abe Lincoln in Illinois (1940) was registered as a bigger flop for the studio.

McBride’s interview explains that the Amberson debacle was part of a larger effort to undermine Welles. RKO was in turmoil, having lost many key executives. Building off his book What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? A Portrait of an Independent Career, Joe suggests that after the problems with Ambersons and Welles’ departure for Rio, factional fights broke out among the suits. Schaefer, attacked for the disappointing box office of Kane, was caught between defending Welles and trying to save his job by cutting Ambersons.

Executives worked to sabotage Welles’ next project as well. One powerful piece of evidence that Joe discovered shows that RKO lied to Welles about the budget for It’s All True, so they could attack him for imaginary overruns. In his interview and book Joe reveals that Welles was under budget by over $440,000 when he was fired for going over budget.

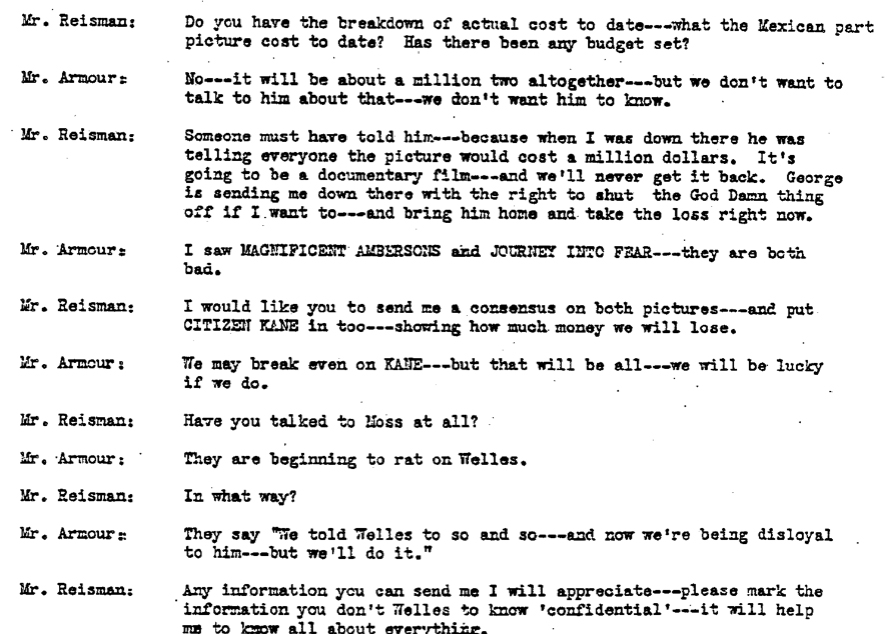

Joe also cites a damning transcript of an April 1942 conversation between two RKO executives, Phil Reisman and Reginald Armour, who conspired to keep information from Welles.

The reference is to Jack Moss, Welles’ business manager. Reisman and Armour go on to discuss the possibility of getting Welles drafted and speculate what could be salvaged from It’s All True–perhaps a couple of shorts?–and Armour adds: “George will lose his job out of this.” Schaefer was fired from RKO at the end of June.

Soon after the release of Ambersons in July, Welles’ Mercury unit was moved off the RKO lot. Welles returned from Rio still hoping to rescue It’s All True, but soon he would become a director for hire.

The Criterion disc release reminds us of how original Welles was in his storytelling strategies. Reinventing Hollywood argues that in Ambersons Welles found a fresh way way to treat time shifts. He keeps major action offscreen and prior to the scene we see, so that each character becomes a narrator reporting action to others, without benefit of flashbacks. The famous scene of Fanny and George in the kitchen is a good example, as he tells her that Eugene joined their trip to the college commencement.

There are many other examples; nearly every scene’s dialogue reaches back to the recent or distant past.

This rather literary strategy of replacing showing by telling echoes the narrative strategies of Henry James and Joseph Conrad–the latter a writer whose work influenced Welles strongly. In the 1940s Hollywood context, all this recounting in retrospect constitutes a “knight’s move,” a swerving response to the emerging flashback conventions of the time. I believe that Welles rethought his radio brand, “First Person Singular,” for Ambersons.

Welles’ original ending, which shows Eugene and Fanny reminiscing in her boarding house, was in keeping with this strategy of suppression. Eugene recounts the resolution we haven’t seen: the reunion of George and Lucy, and George’s contrite reconciliation with Eugene. “We shook hands.” Ending with George and Lucy, the new generation, would have been conventionally upbeat, but Welles wanted to linger on the old people–one the automobile pioneer, the harbinger of dubious progress, and the other a castaway of plutocratic pride and self-absorption.

The reshot scene in the hospital corridor exudes a hollow cheerfulness that generations of critics have rightly found a travesty.

This hospital shot lacks the pathos of Welles’ scene, in which a numb, impoverished Fanny is left alone while Eugene drives back into the grimy city. Still, at least the shot preserves much of the original dialogue and it sustains a narration that keeps crucial events (George’s apology and the lovers’ reunion) offscreen and in the past. To the end, action is replaced by reaction–or rather, by reflection.

My title today is a bit misleading. The artist/artisan distinction is fuzzy. Curtiz and Welles are both. The difference might come down to this: The creators we call artisans are adept at solving problems set by tradition or their contemporaries. But those we deem artists think up new problems and solve them with aplomb. They may even set themselves problems that seem ridiculously constraining (such as Ozu’s decision about low camera height). In any case, we need to recognize craft in any medium, because that helps us appreciate achievement of every sort.

I owe a big debt to Joseph McBride for his careful checking of earlier drafts of the Welles section of this entry. His What Ever Happened to Orson Welles is an indispensable guide to the director’s career. Any mistakes or misjudgments that remain in this entry are my doing. Thanks as well to Eric Hoyt for help on RKO financial information.

Joe also points out that Simon Callow’s Criterion interview contradicts other researchers’ findings about Welles’ calls and cables from Brazil. In addition, I wonder whether Rode’s citations of the Curtiz films’ grosses shouldn’t be called their rentals–that is, the chunk of the gross box-office receipts returned to the studio. For example, he lists Casablanca‘s grosses as being $$4.496 million. This is close to Variety‘s figure of $4.145 million for the film’s rentals. See Lawrence Coh, “All-Time Film Rental Champs,” Variety (24 February 1992), 164. Typically a picture’s rentals were about half of its gross.

Patrick Keating’s new book The Dynamic Frame: Camera Movement in Classical Hollywood calls the kind of tracking shot in Kid Galahad the “follow and switch.” He has much to say about Curtiz’s work in his fascinating account of how Hollywood filmmakers thought about and deployed the moving camera.

Curtiz would likely have seen Dupont’s Variety during his stay in Austria, or even in the US in 1926; it played Los Angeles in June and New York in July. Curtiz arrived in the US on 6 June 1926, and The Third Degree was released on 26 December. As Rode points out (p. 77), the trade paper Variety saw an affinity between Curtiz’s film and Dupont’s, though the reviewer scoffed at the “trick camera stuff” and “freak shots” (5 January 1927, p. 17).

I consider Casablanca in this entry, which ties in both to Reinventing and to Pauline Lampert’s podcast Flixwise. My fullest discussion of Ambersons online is here; the section in Reinventing is somewhat different. On Welles the silent-era cinephile, this entry on his centenary is also relevant, as is this later one.

The following errors are in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood but are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Horrible.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Duh. I try to do the film, and its genre, justice in another entry.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” What was I thinking?

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix,” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find slips like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. So I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

On the set of Casablanca.

Vancouver 2018: Two takes on two directors

The Eyes of Orson Welles (2018).

DB here:

If you want to make a biographical documentary, you face problems of structure. Do you go chronological—start with birth, go through youth, maturity, and death? Or do you start in medias res, at the peak of fame or the depths of failure, and flash back to origins and development? Or do you do something else altogether? These are essentially the same problems of narrative that face the fiction filmmaker, but of course the documentarist also confronts gaps in the record, incompatible information, and the prospect that the story has been told before and may benefit from a fresh perspective.

Two documentaries at Vancouver tackled these problems in instructively different ways.

How to become famous: Work very, very hard

True to its title, Jane Magnusson’s Bergman: A Year in the Life picks Ingmar Bergman’s breakthrough in 1957 as its through-line. It was indeed quite a year: The Seventh Seal opened in January, Wild Strawberries in December, and Brink of Life was filmed in between (to open in early 1958). Very soon, Bergman won acclaim as one of cinema’s greatest artists. In the same annus mirabilis Bergman directed a TV drama and four theatre productions, including a monumentally successful five-hour version of Peer Gynt. All this he accomplished while suffering intense stomach pain; for part of the year he was in the hospital.

To survey only the events of January through December would leave us in the dark about the director’s full accomplishment, so the calendar format becomes a sort of clothesline on which incidents from all across his life are pinned. Since Bergman’s published memoirs are notoriously unreliable, Magnusson says that the films are more faithful records of his life and obsessions. But she also opens up many documents that fill in or correct his account, and the result becomes a fairly chronological survey.

For example, early in the documentary we learn of Bergman’s real relation to his father, his youthful admiration for Hitler during his stay in Germany (“I shouted like the others. I raised my hand like them”), and his first lover Karin Land, a spy for Finnish intelligence. As the film proceeds through 1957, it surveys his prior career and points ahead as well. Through associational links, motifs in The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, along with a survey of his childhood and his sexual partners, in effect provide flashforwards to Persona, Fanny and Alexander, and other later works.

The wellsprings of Bergman’s astonishing 1957 output are only hinted at. He was obviously a workaholic, as several commenters point out. One observer reminds us that Fassbinder had years that were as brutally productive, but he owed his stamina to drugs; for Bergman, the fuel was Swedish yogurt, Marie Biscuits, and sex.

Still, I wonder whether advancing through the Swedish film business, a rather industrially strict one, may have accustomed him to a killing pace. He started as a screenwriter at age 26, and he took up film directing two years later (not an uncommon age to begin). From 1948 on, he often signed two films a year as director and a third as a writer. You could make a case that his first breakthrough was really 1953, with the remarkable duo Summer with Monika and Sawdust and Tinsel. From the start, he was directing plays as well; in that same 1953 he mounted five. 1957 seems a landmark because the two films of that year became official international classics, winning festival prizes and wide distribution, but the man’s volcanic drive seems to have been there for a decade before.

In any case, the year-in-the-life format provides a handy point of entry into an astonishing, lengthy career. Magnusson has excavated many valuable documents and collected striking testimony, not least from coworkers whom the great man energetically humiliated. I learned a lot, not least that you can free up your documentary from the constraints of sheer chronology.

The Great Man draws

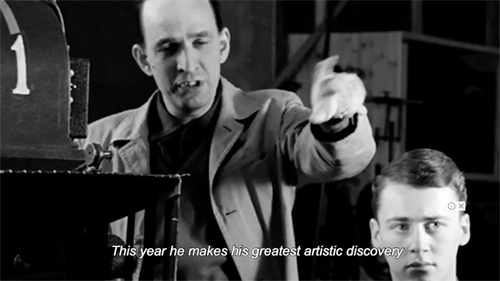

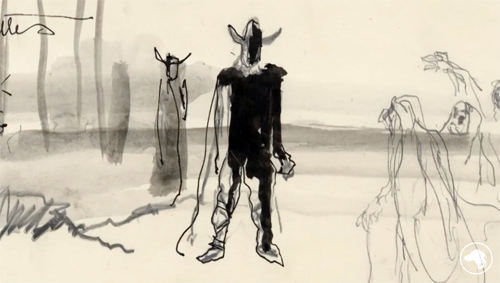

The same lesson issues more strikingly from Mark Cousins’ essayistic The Eyes of Orson Welles. Welles was of course another workaholic, moving across media freely. His energy was no less titanic than Bergman’s. For years we’ve known Welles the stage director, Welles the radio impresario, Welles the actor, and Welles the moviemaker. Now Cousins shows us Welles the graphic artist, and it’s a captivating, revelatory angle.

Welles started drawing as a child, and he later declared that painting was more important to him than filmmaking. Cousins examines hundreds of pictures archived at the University of Michigan and held by Welles’ daughter Beatrice. His film argues, with shrewd penetration, that a pictorial sensibility was central to Welles’ creative project. “You thought with lines and shapes. Your films are a sketchbook.”

How to structure this exploration? The film appears to offer trim boxes within boxes. Framing it all is a letter written and spoken by Cousins to the departed Welles. That apostrophe is in turn broken into numbered parts, some of which are in turn chopped into short topical segments. But these are engagingly digressive and untidy. For instance, part 3, devoted to Welles’s loves, skips from love of places, to love of vision itself (and Dolores Del Rio in Bird of Paradise), to love of chivalry, to omnivorous love (male friends), and finally to guilt over the death of love. A bit of Borges, a dash of Chris Marker: the swarming categories rub together in a cubistic way that Welles himself would probably have enjoyed.

In this porous, expanding design, Cousins takes us through familiar biographical terrain. The idea of Welles the graphic artist functions like 1957 in Magnusson’s film, a convenient wedge to open up episodes from family life and professional career. But Cousins brings out the pictorial side of well-covered material, such as the stage designs for the Harlem Macbeth. And he gains a lot from the frankly personal perspective. By writing a letter, he can ask rhetorical questions, mull over associations, imagine how Welles would view the modern world, and freely speculate on hidden autobiographical elements. “You wanted to be Falstaff, but you were Prince Hal.”

I came to Cousins’ film expecting a treatise on Welles’ cinematic style, and we get doses of that, but in unexpected ways. It turns out that most of his drawings don’t look a lot like his shots. Cousins floats the idea that Welles’ stay in Chicago, city of skyscrapers, may have tutored him in the low angles we see in his movies, but this seemed to me a stretch. Sketches of faces do, however, remind us of his fascination with actors, and of course his plans for sets, both on stage and on film, are very revealing.

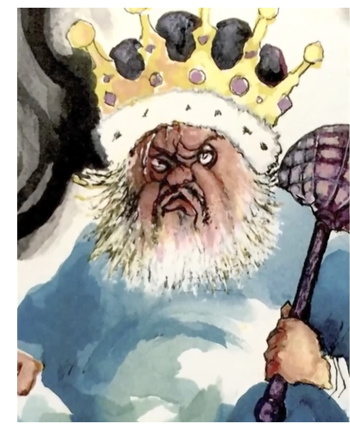

Cousins is very convincing on iconography. In both drawings and films there’s a recurring image of facelessness, which I had never noticed. There’s also the motif of domination and failed kingship, rulers who “can’t escape their own power,” and these ideas lead Cousins to a brilliant discussion of Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. And looking at the art resensitized Cousins to Welles’ cinematic strategies, whether or not they can be directly traced to a source. He points out the odd symmetrical camera movements that follow a cigarette passed along a lounging Rita Hayworth in Lady from Shanghai. This is a critic’s film, and the observations would be worthwhile even without the biographical pegs they hang on.

Cousins is very convincing on iconography. In both drawings and films there’s a recurring image of facelessness, which I had never noticed. There’s also the motif of domination and failed kingship, rulers who “can’t escape their own power,” and these ideas lead Cousins to a brilliant discussion of Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. And looking at the art resensitized Cousins to Welles’ cinematic strategies, whether or not they can be directly traced to a source. He points out the odd symmetrical camera movements that follow a cigarette passed along a lounging Rita Hayworth in Lady from Shanghai. This is a critic’s film, and the observations would be worthwhile even without the biographical pegs they hang on.

The obvious comparison is with the drawings of Eisenstein, perhaps more skillful than Welles’s, but equally suggestive of the filmmakers’ obsessions. Like Eisenstein as well, Welles shows a rueful humor in his sketches. Cousins acknowledges this streak in yet another section, a hypothetical posthumous reply from Welles to Cousins’ letter. Welles chastises his biographer for playing down the lighter side of his films and pictures. This is nicely illustrated by charming drawings for Christmas cards Welles sent his children. But Cousins shows the fun running down. Over the years Santa’s face droops and wobbles, the eyes grow hollow and the mouth goes slack. Santa as another ageing Welles tyrant? A teasing juxtaposition like this offers another reason to let The Eyes of Orson Welles train ours.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

For more on Bergman and Welles, see our categories devoted to the directors, on the right. A list of Bergman’s productions in film and other media is here.

Bergman: A Year in the Life (2018).