Archive for the 'Directors: Welles' Category

Breaking AMBERSONS news: Did you say Buried?

DB here, again and still:

Still, until somebody comes along with a better account, I’m ready to believe that we’ve found the film.

That’s me, just two days ago. I suggested that the mystery poster tucked into the corner of one shot in The Magnificent Ambersons is the Pathé release of 1912, The Cow-Boy Girls. Readers with long memories and no life of their own will recall that this question has bugged me since my earlier post in May. Last week my colleague Eric Hoyt suggested what the title might be, and some rummaging in various sources, particularly the invaluable Lantern database, seemed to confirm it.

To recap: Here are two blow-ups from a 35mm print, showing the two angles from which Welles’ camera captures the poster. The text is clearer in the half-size one, but the more distant one yields a fuller view. The poster seems to depict a man thrashing an American Indian, with a young woman, arm outstretched, in the rear. Note also the shield-like triangular shape underneath the title on the first image.

Last night came word from two more vigilant correspondents, each with new evidence–again, unearthed by the light of Lantern.

My first correspondent was Luke McKernan, early film specialist and master builder of the vastly informative website The Bioscope. Luke has stopped posting there, but he continues to write keenly on cinema at lukemckernan.com. His message to me runs as follows:

Dear David,

I have struggled and struggled with this one til I’m at the point of worrying about my eyesight. I don’t think it can be The Cowboy Girls, but searching for the keyword Cowgirl might be productive. I found this in the Lantern site, searching for ‘cowgirl’ and 1912:

http://lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/movingpicturenew05unse_0122

It’s not the right film, but the still is quite close to that in the Ambersons poster, which at least gives encouragement.

Luke

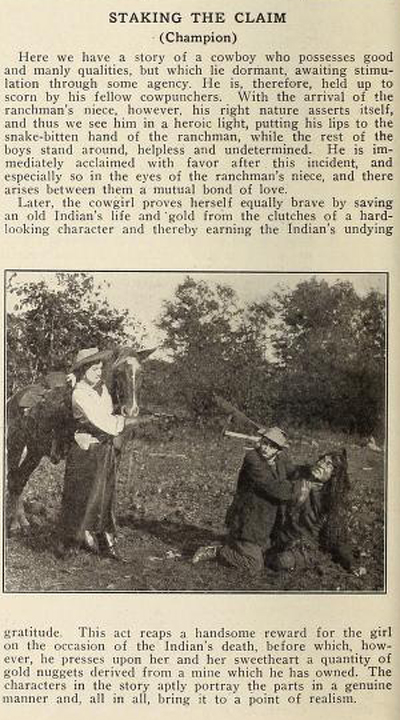

The entry Luke refers to is this one, from The Moving Picture News of 1912.

The picture shows the situation we find in the Ambersons poster. But as Luke says, our poster’s title clearly is not Staking the Claim. More research, as we academics say, is needed.

Just a few hours later came this from another colleague here at Madison, Ph.D. candidate Eric Dienstfrey.

Hi David,

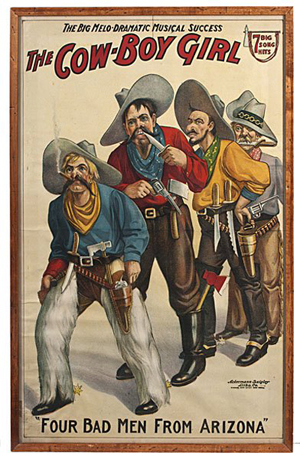

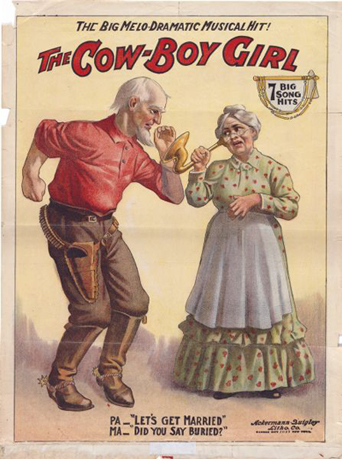

Reading your post on Ambersons now, I remember coming across the title The Cow-Boy Girl while researching stage musicals that were contemporary to Gottschalk’s The Tik-Tok Man From Oz and The Patchwork Girl of Oz. You are absolutely correct, the poster does say “The Cow-Boy Girl” but it was for a theatrical musical, not a film… at least I don’t think so. (But many films were probably called Cowboy Girl too.) I’ve attached two different posters from the musical that I found online. The triangle shield is not the Pathé rooster after all!

I hope you find this interesting/useful… or better yet, I hope this brings you a little closure.

Cheers,

Eric

I had mentioned on Saturday that there was a stage show called The Cow-Boy Girl, and I wondered whether the poster was promoting not a film but the theatre piece. In the end, I went with a film title. But Eric D’s visual evidence of the title font and the triangular motif (not a shield but a swag curtain, I think) strongly suggests that we’re dealing with a play. It would be characteristic of a theatre in 1912 to include vaudeville, stage shows, and other live entertainment alongside movies.

The Cow Boy Girl (no hyphen), a thirty-minute playlet including songs, was reviewed, unfavorably, by Variety (29 October 1910). The review doesn’t mention a scene like that depicted on the poster.

Other sources lists touring shows of The Cow-Boy Girl (with and without hyphen) from 1910 onward, so it might well have been playing the Bijou in the Ambersons’ town in 1912. Actually, Eric D. has found that it did play another Bijou. The Billboard of 18 February 1911 lists the following:

How can you argue with something that played the home of thrillers?

Are we there yet? Until we find a copy of the poster itself, I’m inclined to think so. But as Luke’s discovery indicates, we’re dealing with a period in which imagery, titles, and situations were copied and circulated in great profusion. In 1912 plenty of cowgirls and cowboys and cowboy girls and cow-boy girls were swarming over American entertainment. More or less like superheroes today.

No research project is finished, only abandoned. Thanks to the Fussbudget Team for playing!

The Fussbudget Report: An AMBERSONS solution

DB here:

Some readers may recall my post on The Magnificent Ambersons back in May. I argued that Welles built a sense of the irretrievable past into many aspects of the film’s narration. He used the voice-over commentary to evoke times gone by, but also ellipsis, offscreen action, constant recitation of memories, and other strategies. In addition, there were moments of cinephile nostalgia, including the iris shot at the end of the snow scene and the concluding credits of the actors slowly turning to face the audience, as in the manner of films of the 1910s.

Then there were the movie posters. George and Lucy are walking through the town. He’s about to leave for Europe, and she feigns a polite lack of concern. They pass the Bijou movie house, which flaunts several posters. I managed to identify all but one, the one tucked in the lower right of the frame above. I just couldn’t properly read the title, even on a good 35mm print.

Blown up from 35, the clearest view we get of it looks like this.

I thought it might be The Coin-Box Girl, but no such film title existed. Some readers– Jacopo Pes, Ivo Blom, and Paolo Cherchi Usai (thanks to all)–proposed some possibilities. Alas, none of their suggestions seemed to fit. Even running through the Library of Congress copyright listings for films didn’t yield a plausible candidate.

Over a lunch with colleague Eric Hoyt last week (Eric is one of the geniuses behind Lantern), we talked about this. Eric had access to a bigger list of titles than that of the LoC, and he suggested that the first words might be cow-boy. Checking his list, we find that there was indeed a May 1912 Pathé release called The Cowboy Girls. It’s also listed in Lauritzen and Lundquist’s American Film-Index 1908-1915 under that name. It might well have been postered as The Cow-Boy Girls. (We now assume that the squiggly line after “Cow” is a hyphen. It might be just a really curly w.) An April 1913 ad from the Carbondale Daily Free Press lists a film called The Cow Boy Girls, so if it’s the same movie, there was some freedom of punctuation around it.

I left the second ad underneath so you can appreciate having electricity.

It would be very nice to check a poster of the film, but I haven’t found one. Here, though, is a synopsis from Moving Picture World of 1912. (Again, thanks to Lantern.)

This doesn’t quite match the image on the poster, which shows a man apparently about to strike a Native American kneeling before him. But in the background, more visible in the half-framed poster, there seems to be a young woman coming out of a cabin protesting, and perhaps brandishing a pistol. (Open Carry applies here.)

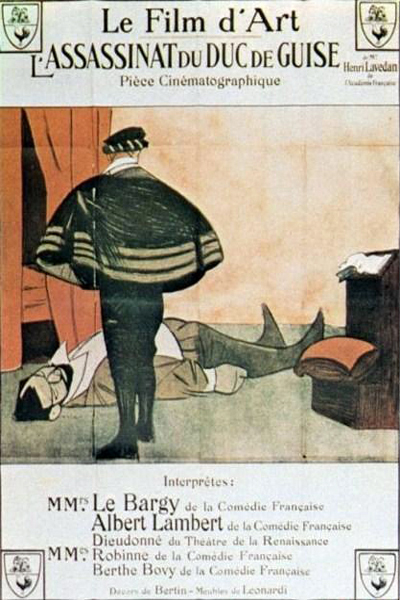

There are other anomalies. If this is indeed The Cowboy Girls from Pathé, does the triangular shield logo in the northwest corner boast a rooster? Some Pathé titles did, as for this 1908 French release (one of the most important films ever made). On the four shields, the rooster (also to be seen as decor in Pathé interiors) is joined by the eternal symbol of the theatre, the comic and tragic masks.

And if The Cowboy Girls is a Pathé title, did the Carbondale ad list it as “Essany” (Essanay) by mistake? Or is that a different cowgirls movie? It may be relevant that there was a vaudeville play called The Cow Boy Girl, which was touring at the same period. Filmmakers may have tried to cash in on that. Or maybe the Ambersons Bijou was presenting that stage show rather than a film?

Still, until somebody comes along with a better account, I’m ready to believe that we’ve found the film. The clincher for me is the Cowboy Girls’ date: 1912. Except for the fake lobby card promoting a nonexistent Jack Holt movie, all the discernible film posters in the Ambersons scene are from 1912 releases.

This obsessive synchronization is surely the work of a film nerd, either Welles or a staff member. Geek calls out to geek, from 1912 to 1942 to 2014. See? I’m not the only fussbudget here.

The Magnificent Ambersons (1942).

THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS: A usable past

Hellzapopppin’ (1941).

DB here:

By now everybody is used to allusionism in our movies—moments that cite, more or less explicitly, other films. But we tend to forget that movies have been referencing other movies for a long while. One classic form is parody, as when Keaton’s The Three Ages (1923) makes fun of Intolerance (1916). Another example occurs in Me and My Gal (1932). Spencer Tracy tells Joan Bennett that he just saw a movie called “Strange Innertube,” and then Raoul Walsh gives us a comic version of the inner monologues used in Strange Interlude (1932).

Some allusions are in-jokes that sail by most viewers. Almost everybody notices when Walter Burns (Cary Grant) in His Girl Friday mentions that a character played by Ralph Bellamy looks like “that fella in the movies—you know, Ralph Bellamy.” Probably fewer people catch the later line, Walter’s threat to the authorities: “The last man who said that to me was Archie Leach just a week before he cut his throat.” Grant’s real name, of course, was Archibald Leach.

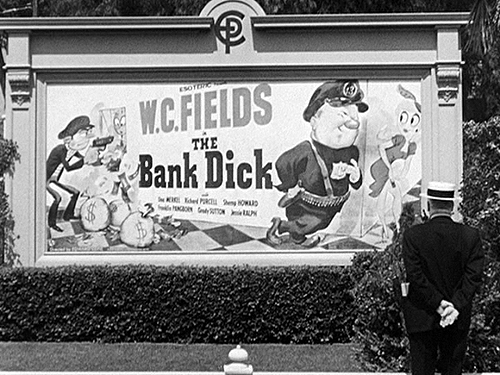

Week-End at the Waldorf (1945) is a sort of updating of Grand Hotel, so when one character remarks that a plot twist “is straight out of the picture Grand Hotel,” we probably catch the self-reference. But the other character piles on the allusions by replying: “That’s right. I’m the baron, you’re the ballerina, and we’re off to see the wizard.” Did people notice MGM congratulating itself twice? And you wonder how many viewers catch the spoiler in Hellzapoppin’ (1941), released only four months after Citizen Kane. Chic Johnson spots a Rosebud sled hanging outside an igloo and remarks, “I thought they burnt that.”

At the beginning of the 1940s, two novice directors seemed to be bringing fresh air to Hollywood cinema. Preston Sturges and Orson Welles were identified with innovative approaches to genre and storytelling. So we might expect them to inject something new into this practice of alluding to other movies. I think they did.

Consider a particular strategy that Sturges and Welles toyed with. Today, we enjoy it when a director treats characters in non-sequel films as sharing a fictional world. Tarantino imagines shifting his characters or brand names (e.g., Red Apple cigarettes) from movie to movie.

When I sell my movies, I retain the rights to characters so I can follow them. I can follow Pumpkin and Honey Bunny or anybody and it’s not Pulp Fiction II.

Jackie Brown (1997) features Michael Keaton as FBI agent Ray Nicolet, who also appears, played by Keaton, in Soderbergh’s Out of Sight (1998). The tactic fitted these directors’ adaptations of novels by Elmore Leonard, who tends to carry over characters from book to book.

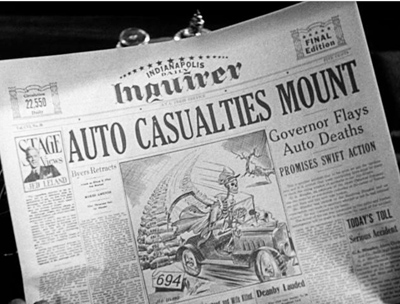

It’s a bit surprising to see this impulse in Sturges and Welles too. The governor and the political boss in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944) are McGinty and the Boss in The Great McGinty (1940), and they’re played (uncredited) by the same actors. A newspaper glimpsed in The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) contains a column, “Stage Views,” by drama critic Jed Leland, a major character in Citizen Kane (1941).

Today fans are used to spotting things that most viewers might not get, but in the early 1940s, it was rarer. I’ve proposed earlier that sometimes Hollywood’s creative community is addressing not the broad audience but its own members, perhaps letting dedicated outsiders “overhear” the conversation. One example would be the nearly-hidden jokes that can be wedged into the background or on the edges of the action. In an entry about a year ago, I considered how sequences around the small-town movie theatre in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek carry barely-noticeable jabs at current films, mostly those by Sturges’ home studio Paramount. And Luke Holmaas has pointed out to me that Hail the Conquering Hero contains a billboard advertising Morgan’s Creek—a sort of joking product-placement. Today, I want to suggest that Welles moved onto the same terrain but followed even more circuitous paths.

The past, not recaptured

Make pictures to make us forget, not remember.

Comment card from first preview of The Magnificent Ambersons, 1942.

The Magnificent Ambersons is, everybody knows, a film about the past. Its story action begins around 1885 and concludes just before World War I. Most of the plot concentrates on the decline of the Amberson family, due partly to financial mismanagement and the willful pride of Isabel Amberson’s son, George Minafer. Parallel to that decline is the development of the town into a city and the rise of the automobile company founded by Eugene Morgan, a failed suitor for Isabel’s hand. A major turning point comes when, after Wilbur Minafer’s death, Isabel is left a widow. She’d like to marry Eugene, but she declines because George is opposed. At the same time, George tries to win Eugene’s daughter Lucy. After the death of Isabel and her father Major Amberson, the family is destitute and George must find a way to support his aunt Fanny. Struck by a car, George is hospitalized, and only then does he reconcile with Eugene and Lucy.

After weak previews, the film was drastically recut, and some new scenes were shot. The original version has not yet been found, so we’re left with a ruined masterpiece. Still, there’s enough there to let us appreciate Welles’s effort to make sense of a crucial period of American history. Old money was giving way to modern, technology-driven fortunes; Eugene’s auto company is the Dell Computers of its day. The film also evokes changes in urban life, with shifting property values and rising pollution shown as consequences of progress. It’s the most downbeat of the “nostalgia” cycle of the 1940s, which includes Strawberry Blonde (1941), Meet Me in St. Louis (1944), and Centennial Summer (1946).

Many other films have sought to present the past, recreating the settings and costumes and props of an era. But Ambersons is about pastness. It conveys a melancholy recognition that things are always changing, that we struggle to make sense of events only after it’s too late to affect them. It’s a film centered on missed opportunities and what might have been. Eugene might have married Isabel when they were young, but his drunken serenade turns her against him. If George weren’t such a prig, he might have reconciled himself to Isabel’s remarriage; only at the end, kneeling in prayer, does he seem to realize how his stubbornness cheated many people of happiness. The original ending would have shown Eugene visiting Fanny in a boarding house, with her long and unspoken love for him counterpointing his suggestion that he’s been true to Isabel.

Ambersons carries its sense of an unrecoverable past into the very texture of its telling. At first, the aura of things gone by is given by Welles’ voice-over narration. In affectionate comedy he introduces us to habits and routines of an era of streetcars and changing men’s fashions. After Eugene’s botched serenade, the townsfolk add their voices to the chorus with comments on the scandal. More backstory is given when George is shown growing from a spoiled boy to an arrogant young man. Our narrator recalls “the last of the great Amberson balls.” Eugene arrives, a widower, bringing his daughter Lucy, and George begins to court her that night.

Now the narrator’s past-tense explanation withdraws for some time. Instead, characters take up the burden of narrating the past. “Eighteen years have passed,” says Isabel’s brother Jack at the ball. “Or have they?” Before Eugene dances with Isabel, he remarks that the past is dead. Unfortunately, it won’t stay buried. The old romance between Isabel and Eugene will be rekindled, and bad business decisions and George’s spendthrift ways catch up with the family.

Welles’s plot construction relies on ellipsis. The scenes skip over major story events—Wilbur’s death, the decline of the family fortune, Gene’s second courtship of Isabel, and Isabel’s death. So much occurs offscreen that we are left to play catch-up. We must listen to characters report on what has just happened, or reflect on the more distant past. The film is built on recollection and reaction. We don’t see Fanny at Isabel’s deathbed; she simply flies out of the room to embrace her nephew: “She loved you, George.” We don’t see George and Isabel on their European trip; we learn of it from the doleful Uncle Jack, who thinks that Isabel is falling sick. This refracted narration allows Jack to voice his concern—he’s probably the one Amberson whose judgments we trust—and Gene to display helpless, rigid sorrow at the news.

One of Ambersons’ most famous scenes, the long take of George and Fanny in the kitchen, is characteristic. Under her questioning, he explains that Gene and Isabel were starting to reunite at his college graduation. A peppy nostalgia movie would have shown us that cheerful moment on the campus, but Welles channels the information through George’s insensitive report and Fanny’s uneasy questions—and the scene climaxes with her breaking down in tears. As ever, melancholy wins out. As a result of George’s telling, Fanny will plant the suspicion that gossip about Isabel has been destroying the family’s good name.

Similarly, another film’s finale would show the reconciliation of the young lovers, George and Lucy, in the hospital. Instead Welles’ original script presents that moment through Eugene’s somber report of it to Fanny in her boarding house. (In the version we have, we get the report in the hospital corridor.)

Sometimes, the gaps in time and action are abetted by the studio’s reediting. In the present version, we learn about Aunt Fanny’s failed investments later than in the original version. But even then the information would have been presented after the fact. On the whole, the sense of the sadly unalterable past is built into Welles’ screenplay. As each scene unfolds, we get news about what has happened in the gap since the last scene, or what has happened years before. At the railroad station, Uncle Jack, about to depart, recalls a woman he left here long ago. “Don’t know where she lives now–or if she is living.” Here the pastness he evokes is familiar to us from earlier in the film: “She probably imagines I’m still dancing in the ballroom of the Amberson mansion.” At the limit, Major Amberson’s garbled fireside reverie takes us back to the origins of life: “The earth came out of the sun, and we came out of the earth . . . so–whatever we are must have been in the earth.” Now the past is primeval.

Retro as remembrance

Welles enhances the aura of pastness through specific film techniques. Critics have rightly been alert to creative choices that carry over from Citizen Kane: looming sets, drastic deep-focus cinematography, low angles, chiaroscuro, and long takes, often employing splendid camera movements. But the film displays some unique choices that are, historically, anachronistic.

The most noticeable old-time technique concludes the idyll in the snow. Jack, Fanny, Lucy, and George are riding in Eugene’s horseless carriage. This, one of the few scenes that doesn’t replay the past in its conversation, is given special treatment as a moment out of time. The iris out that concludes the scene is something of a visual equivalent to the old song the riders sing, “The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo.”

Similar is the vignetting that softens the edges of the opening sequences, starting with the first shot showing the streetcar stopping for the lady of the house.

Welles’ visual techniques aren’t faithful to the period when the story action takes place. Assuming that the snow idyll occurs around 1904, the iris wouldn’t have appeared in films of that time. And the earlier period of the streetcar shot and changing men’s fashions probably predates the invention of cinema. But by 1942, these techniques were associated with silent film generally and give a cinematic tinge of “oldness” to the action.

I say “by 1942” because recent years had made intellectuals especially conscious of film history. Several books, notably the 1938 translation of Maurice Bardèche and Robert Brasillach’s Histoire du cinéma (translated as The History of the Motion Picture) and Lewis Jacobs’ sweeping The Rise of the American Film (1939) had concentrated on the stylistic innovations of Porter, Griffith, and other pioneers. With some theatres reviving silent classics like Caligari and The Birth of a Nation, cinephiles in urban centers had some opportunities to see silent movies. Most notably, the Museum of Modern Art Film Library was founded in 1935 and under the curatorship of Iris Barry, began building a permanent archive and screening retrospectives.

MoMA also assembled many films into traveling 16mm programs that could be rented by schools, museums, libraries, and other institutions. Silent films also circulated in 8mm and 16mm prints from private companies like Kodascope and Castle Films. Throughout the late 1930s and 1940s, silent comedies were the most popular; Chaplin reissued The Gold Rush in a sound version in 1942. Welles’s interest in silent slapstick is shown in the recently discovered pastiche, Too Much Johnson (1938), which evidently owes a good deal to Entr’acte (1924), a MoMA-canonized classic.

Ambersons offers other, less obvious allusions to old cinema. One cluster of them comes during George and Lucy’s stroll along the sidewalk. George, somewhat petulantly, is insisting that his trip abroad with his mother may last a long time. “It’s goodbye, Lucy.” Angling for a declaration of devotion from her, he gets brittle, agreeable indifference. When he has stalked off, we learn that she is actually quite shaken by the prospect of separation. Watching the dramatic interplay in this long traveling shot, we are probably not likely to pay attention to the posters the couple pass outside the Bijou theatre.

The advertisements announce movies that could have played the Bijou in 1912. The ones in the rear of the lobby are impossible to make out, and there’s one outside I can’t be sure of. (See the codicil.) Raking the frames on DVD and on a good 35mm print, I’ve been able to discern The Bugler of Battery B (1912), Her Husband’s Wife (aka, How She Became Her Husband’s Wife, 1912), Ten Days with a Fleet of U.S. Battleships (1912; in the foyer), and The Mis-Sent Letter (1912). There were several Jesse James films circulating in 1911-1912, but one two-reeler named for the bandit (at the bottom of the second frame here) seems a likely candidate.

These casual background details betray extraordinary fussiness on the part of Welles and his colleagues. Few viewers would pay attention to all the posters, and very few viewers would realize that they’re all from the same year. It’s one thing to include authentic automobiles from the era, as car fanciers would be sure to spot mistakes. But 1912 two-reelers? It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the filmmakers put the posters in to satisfy themselves. (If you’re skeptical, I’d ask: If you’d thought of it, wouldn’t you do it?)

There’s more. The most prominent hoarding advertises a Western, The Ghost at Circle X Camp (1912), from Gaston Méliès. Surely the name also evokes Gaston’s brother Georges, by then an established pioneer of film history and a figure doubtless known to Welles. Is this a sideswiping tribute from one magician-cineaste to another?

There’s also a deliberate anachronism. Tim Holt, who plays George, was the son of action star Jack Holt. A lobby card over the box office announces “Jack Holt in Explosion.”

I can find no trace that such a film existed. Moreover, films of that era seldom identified the main actors in advertising, and in any case Holt was not a featured player in 1912. In order to create an in-joke/homage, Welles seems to have prepared a poster for a fictitious film—as Sturges did with Chaos over Taos and Maggie of the Marines in The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek.

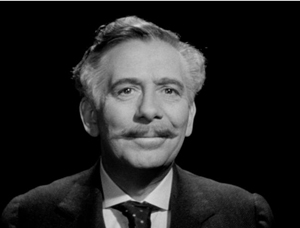

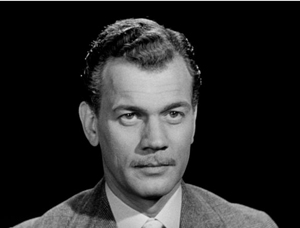

Perhaps the most sneaky allusion comes at the very end. After the florid voice-over credits for technical contributions, Welles intones: “Here’s the cast.” Medium-shots of the actors dissolve into one another as the voice-over identifies them. The images recall photographic portraits from the nineteenth century. They also seem to be a variant of those 1930s opening credits that catch the players in shots extracted from the movie to come. Still, there’s something peculiar about these.

Some of the actors look straightforwardly out at us, as we’d expect.

But others turn their heads slightly or shift their gaze, toward or away from us.

Sometimes the shift is tiny, as with the Joseph Cotten cameo. But the tactic is made into a joke when Tim Holt, staying in character, snaps his glance furtively to the camera.

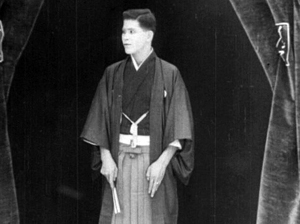

Why these fillips? Here’s my conjecture. Some 1910s films, from both America and Europe, introduced their casts with shots of the actors standing as if on a theatre stage. The actors then looked to left, then right, pretending to take in all sides of a live audience. Here’s an example from Reginald Barker’s The Wrath of the Gods (1914), featuring actor Thomas Kurihara.

None of the 1910s examples I know was framed as closely as Welles’s shots are. But I surmise that Welles offered a modernized variant of a minor silent-film convention. If this is right, it has to be an allusion more far-fetched than even the ones Sturges supplied.

Maybe I’ve gone too far. Once filmmakers start playing these games, overreach is a constant temptation. In any case, I think there’s enough evidence that Welles, like Sturges, was invoking early film history as a way of reinforcing the overall pastness-strategy of his film.

I’d go further and speculate that Welles’s obsessively pinpointed allusions may have stirred a competitive spirit in Sturges. Now we can see the Miracle of Morgan’s Creek tracking shot past the movie house posters as a variant, two years later, of the angle Welles chose for his long take.

And perhaps the audacious inclusion of footage from The Freshman (1925) at the start of The Sin of Harold Diddlebock (1947) was sparked by Welles’ virtuosically faked newsreel in Citizen Kane. As the two boy wonders from the East took advantage of the biggest train set a kid could play with, they may have egged each other on.

For more on the practice of allusionism and world-building see The Way Hollywood Tells It. Thanks to Ben Brewster for information on Jack Holt’s career. My quotation of the Ambersons preview card comes from Simon Callow’s Orson Welles vol. 2: Hello Americans (Viking, 2006), 87.

The Holt and Méliès posters are mentioned in the cutting continuity in Robert L. Carringer’s The Magnificent Ambersons: A Reconstruction (University of California Press, 1993), 214. Alas, the other posters aren’t specified.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster that I haven’t identified, and that drives me nuts, sits underneath The Bugler of Battery B. Here’s a blowup from 35mm.

The poster’s illustration, which we can glimpse more fully in a later phase of the shot, shows a man thrashing an American Indian while a woman stretches out her arms in the cabin in the background. At first I thought the first words are The Car, but I can find no film from the period that begins with that phrase. (It would fit more closely with Ambersons thematically than most of the other titles, but in fact “car” wasn’t then a common term for automobile.) Then I thought it was The Coin Box Girl, but again no such film seems to have existed, and that title is hardly in keeping with the illustration. Any ideas?

Yes, I know. Welles would have had a good big belly laugh at these efforts.

P.S. 10 June: I’ve been pursuing some readers’ leads about the still-mysterious poster. In the meantime, Joseph McBride has has corresponded with me with more ideas and information about Ambersons. Joe is the author of many books, including What Ever Happened to Orson Welles?: A Portrait of an Independent Career, Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless, and Into the Nightmare: My Search for the Killers of President John F. Kennedy and Officer J. D. Tippit, a meticulous study of those two murders. He is one of the world’s top Welles scholars, so naturally I’m happy to pass along his thoughts.

AMBERSONS is my favorite film, as you probably know, even in its partly ruined state. I think all your analysis is acute, and I like your focus on the self-conscious awareness of pastness that Welles conveys and dissects in the film. The film is redolent of Welles’s youth and even more so of the period before he was born (the period for which I find most of us are most nostalgic). Nostalgia was considered a neurosis in the pre-modern era, a sign of inability to adjust to reality rather than the warm-and-fuzzy state it’s thought of being today. There’s a deep melancholy throughout the film, even if Welles, good magician that he is, distracts us with misdirection via comedy in the beginning while simultaneously laying the seeds of destruction and foreshadowing George’s “comeuppance,” etc.

Last month I was at the Welles conference in Woodstock, Illinois, which has preserved much of its nineteenth-century flavor, including the Opera House where Welles put on TRILBY (but most of the Todd School for Boys he attended is gone). That town and its main square, with bandstand and Civil War monument, seems very Ambersonian as well. I have always seen AMBERSONS as Welles’s most deeply personal film, and his claim that Eugene Morgan is partly based on his father (and that Booth Tarkington knew his father) is noteworthy, as is George Amberson Minafer’s evil-twin resemblance to the young George Orson Welles.

I would only add to your insights that there was much more about the loss of the Amberson fortune in the full version of the film (you allude to that a bit), even though, as you intriguingly note, Welles employs an elliptical style throughout. Welles’s use of ellipsis is Lubitschean (he considered Lubitsch a “giant”), although used for somewhat different reasons, Welles doing so mostly to condense the story in witty ways (and, as you observed to me, focus on characters’ emotional reactions to offscreen events, in the manner of Henry James) and Lubitsch to evade censorship while providing subtle rather than blunt treatments of sex. And some of Lubitsch’s German films, as you know, start with specially posed head shots of him and his main actors, somewhat similar to what Welles does at the end (though he teasingly keeps himself out of frame, partly to stress the voice aspect and also to keep the identification of himself with George stronger). Tim Holt gazing accusingly at us in the end credits is startling — maybe it’s not only to keep him in character but also to say, “I’m you.”

Welles is terrible (archy, corny, and putting on a phony kid voice) as George in the radio version, which, however, is much like the film in some ways. During the night devoted to radio in the 1978-79 “Working with Welles” seminar I co-hosted for the AFI at the DGA Theater, Welles’s longtime associate Richard Wilson and I ran the first ten minutes of the radio show as the soundtrack for the film imagery, and it worked amazingly well. Welles’s use of ellipsis in the film recalls his radio work, in which he and his writers would condense a large novel into one hour, etc. The vignettes at the opening of AMBERSONS are very much drawn from radio. He sold the project to RKO’s George Schaefer by playing the radio show, though the fact that Schaefer fell asleep before the end might have given them pause.

Welles said he included the “Jack Holt in EXPLOSION” gag did to please Jack when he visited the set. Jack was an action star for Capra before AMBERSONS and turns up in THEY WERE EXPENDABLE, in the scene in which John Ford pays homage to his high school teacher Lucien P. Libby by naming a boat after him. Another of those in-jokes that permeate even classic Hollywood, as you say. Mr. Libby influenced Ford’s portraits of Lincoln and other folksy politicians as humorous storytellers.

Welles’s early films show a keen awareness of film history and culture, more than he would let on later he knew at that young age. He described THE HEARTS OF AGE to me as a spoof of THE BLOOD OF A POET and LA CHIEN ANDALOU. TOO MUCH JOHNSON is full of film influences and allusions (I think I sent you my essay on the film from Bright Lights. And KANE has its share of in-jokes, such as Gregg Toland interviewing Kane on board a ship and Kane responding with his first words in the film after “Rosebud” — “Don’t believe everything you hear on the radio.”

Thanks to Joe for corresponding.

Never Give a Sucker an Even Break (1941).

Carry me back to the old Virginia

Chaz Ebert and Roger Ebert on the stage of the Virginia Theatre, Ebertfest 2012. Photo by DB.

DB here:

The fourteenth Ebertfest, held in the sumptuous Virginia Theatre in Urbana, had its customary mix of independent films old and new, Hollywood classics (sometimes cult classics), an Alloy Orchestra performance, and some unclassifiable items. It was, as ever, a crowd-pleasing jamboree. It reflected Roger’s eclectic tastes and was brought to us by Chaz Ebert, festival director Nate Kohn, and woman-who-knows-and-does-all-things Mary Susan Britt.

You can see the intros, the panels, and the Q & As—that is, nearly everything, except the movies and the offside fun–on the Festival channel here.

The young and the restless

Kinyarwanda.

First features are a hallmark of Ebertfest, and many have stayed in my memory, among them The Stone Reader (2003), Tarnation (2004), Man Push Cart (2006), The Band’s Visit (2008), and Frozen River (2009). This year there were several feature debuts.

Patang (The Kite) concentrates on a single day in the life of a family celebrating the annual festival of kite-flying in Ahmedabad, India. An uncle has returned to town with his daughter, and usual in such movie reunions, old tensions are reignited. A side-story concerns Bobby, a street-wise local, and a little boy who delivers kites. Needless to say, this story intersects with and sheds light on the primary family conflict.

Prashant Barghava is a pictorialist with an eye for startling color and compositions. Shot in nervous handheld images, with many planes of action jammed together and the camera eye seeking something to focus on, Patang reminded me of The Hurt Locker, but without that film’s sense of ominous vigilance. The tone of this one is more exuberant, and the cast of nonactors gives it vibrancy.

Kinyarwanda, by Alrick Brown and an energetic team of collaborators, explores the Rwandan genocide of 1994 in an unusual way. It displays the role of the Muslim community in protecting the Hutu population (many Christian, some not) from the depredations of the Tutsi death squads. To emphasize the breadth of experience, the film adopts a chaptered network-narrative structure. A Catholic priest, a young woman, an angry Tutsi, a sympathetic imam, a little boy, and a leader of the Rwanda Patriotic Front gradually converge, first in a mosque compound, and ten years later in a reeducation and reconciliation camp. The film also plays with time, replaying some key events—notably the Tutsi’s advance on Jeanne’s home—but also anticipating some outcomes. Interestingly, by showing many of the Tutsi killers in 2004 repenting their crimes before we see those attacks, the film builds a degree of compassion into its overall form.

Scenes with adults are dominated by either personal problems (the Hutu/ Tutsi clash infiltrates a marriage) or discussions of religious doctrine. There are as well wordless moments in which we follow children—a little girl whose Qu’ran has been defaced, a boy who encounters a death squad while sent to fetch cigarettes. If the adults supply the film’s prose, the kids are its poetry.

Patang played both Berlin and Tribeca and will be opening in New York, Chicago, and San Francisco soon. Kinyarwanda won awards at several festivals, including Sundance and AFI Fest, and is coming to several other festivals. It arrives on DVD 1 May.

The misfit section

Terri.

Two other young directors got good exposure. Robert Siegel wrote the screenplay for The Wrestler after working on The Onion (Madison cheer obligatory here). His debut feature, Big Fan, is the story of a football fan who is mangled by his idol and has to struggle against his family’s pressure to sue. Patton Oswalt, who had to cancel his Ebertfest visit at the last minute, played Paul with a potato-like obstinacy that offset the shrieking caricatures around him. On the down side, I could have done with a couple of hundred fewer close-ups. (Watching a movie at the Virginia reminds you of the power of the two-shot.) Still, Siegel wisely doesn’t give his hero a girlfriend who would lead him to the Big Normal and wean him away from his obsession. As Siegel points out, “He’s completely happy, but everyone around him thinks he’s unhappy.” Big Fan is an enjoyable portrait of the sports nerd.

More laid-back was Azazel Jacobs’ second feature Terri. It’s sort of a coming-of-age movie, but it has a peculiar humor that such wistful exercises usually lack. Terri, an enormous teenager, goes to high school in pajamas and is teased mercilessly, but he reacts with a dead-eyed passivity that suggests both resignation and resilience. Like the hero of Gulliver’s Travels, the book Terri is working his way through, he’s tied down by Lilliputians around him, but he gets by.

It’s a film of character revelation rather than plot turns. No, Terri’s addled uncle isn’t going to die; no, Terri’s not going to lose his virginity. The action revolves around Jacob Wysocki as the title character and John C. Reilly, who never disappoints in any film, as the school principal. Their scenes together are the heart of the film, and if Terri is looking for a father-figure/ role model this off-center administrator with a soft heart for hard cases wouldn’t be a bad choice. To the film’s credit, though, we have little reason to suggest that he’s looking for any such thing. This movie has tact.

I ran into another Ebertfest first-time-director, Nina Paley, whose Sita Sings the Blues (2009) I first saw and loved at Roger’s event. Kristin had already seen it at the Wisconsin Film Fest. Sita worked her way into our blog and into our Film Art material. Nina, long a foe of copyright in any form, told me she plans an act of “copyright civil disobedience” soon. In the meantime, check her effervescent blog site, news of her new project Seder-Masochist, and excerpts from her new books about Mimi, Eunice, and their take on IP.

And then there was…

Take Shelter.

The first evening’s late show was given over to John Davies and Raymond Lambert’s Phunny Business, a documentary about the rise of a Chicago comic club, and this was preceded by Kelechi Ezie’s The Truth about Beauty and Blogs. I had to miss the doc, but go here for a review from Scott Jordan Harris. The short was charming—a snappy comedy about a single woman trying to be Queen of All Media on her YouTube show. Very quickly her aplomb cracks and she uses her online persona to recapture her straying boyfriend. Her web skills give her a rostrum, and then a tracking device (she follows him on Facebook), but soon her site turns into a diary of mounting desperation.

Higher Ground: Not a come-to-Jesus moment but a go-from-Jesus one. I had trouble figuring out the tone. I think the obvious caricatures, including an unctuous evangelical marriage counselor, were there to suggest that the ordinary believers were more worthy of respect. But they all gave me the creeps, including the relentlessly sunny pastor. Also, it seemed a bit of a hothouse drama. I missed a sense of exactly where this story took place, and I kept wondering how all these people made a living wage. But of course it’s Vera Farmiga’s film, and as usual she projects a wary intelligence. The opening sequence showing a string of people being immersion-baptized had a winning radiance.

Joe vs. the Volcano: Joe wins the match, sort of. It deserves to be a cult film for its portrayal of a workday out of the dankest basements of Brazil and Hudsucker Industries. Still, I thought everybody was trying a little too hard, especially Meg Ryan. Cinematographer Stephen Goldblatt talked about how he likes shooting on film and showing on digital: Film’s richness can support 4K, 8K, or whatever. As for 48 frames per second: “I can’t wait.”

Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time: A warts-and-all tribute to the stubborn director of over thirty films. I can’t think of a question to ask about Paul Cox that the film doesn’t answer.

The Alloy Orchestra: Wild and Weird: Classic early trick-films plus a couple of avant-garde items from the 1920s given new brio by the Alloy boys. It was fun but less hefty than earlier efforts. I especially liked re-seeing Winsor McKay’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (aka The Pet) from 1921, which replays McKay’s fascination with figures and spaces that swell to mammoth proportions (a bit like Avery’s King-Size Canary), though the effect is less looming onscreen than in the comics. You can see the whole thing, and other of the W & W titles, on Fandor, one of this years E-fest sponsors.

I’d like to see the Alloy talents and others move away from the big spectacles like Napoleon and Metropolis, which appeal to our current tastes in splashy films with special effects, and toward quieter, less-known silent masterworks by the French (e.g., Germinal), the Danes (The Abyss, The Ballet Dancer, The Evangelist’s Life), Italians (Il Fauno, Rapsodia Satanica, Ma l’amore mio non muore) and above all Victor Sjöström. Audiences would, I think, love Ingeborg Holm, Sons of Ingmar, Masterman, and The Girl from Stormycroft, and the Alloyists could do them proud. Not to mention William S. Hart, whose films are among the pride of US silent cinema.

Take Shelter: A tour de force of what literary theorists call the fantastic: Is the hero going mad, or is there indeed something real behind his visions of impending disaster? Everyone has praised, and rightly, the precision of the performances and framings. Jeff Nichols was another first-timer at Ebertfest some years back, with Shotgun Stories. Take Shelter is the sort of movie that makes independent American cinema proud.

A Separation: I wrote about it here a year ago, having seen it during what might be my last visit to Hong Kong. This time around, I admired it all over again. It shows many characters’ attitudes without bias (everyone has his or her reasons), and it’s aware of how lies told out of loyalty corrode love. The screening was enhanced by excellent background information from Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics and Omer Mazaffar during the Q and A.

If you’re a good storyteller, I think, you balance straightforward presentation (e.g., A Separation’s exposition, which sketches in the core of a relationship) and somewhat sneaky suppression (e.g., the ellipsis that hides a key event from us). I’ve argued that Iranian directors understand suspense better than almost anybody working today, and this film supports that hunch. Now let’s get hope we get to see, on some platform, Arghadi’s earlier exercise in mystery and ambivalent morality, About Elly. Now there’s an overlooked/ forgotten film.

E-fest goes digital

Ebertfest has shown digital copies of films in the past, notably Bad Santa and Woodstock, but this time around only Take Shelter was on film. Everything else was on HDCam, except Paul Cox: On Borrowed Time, which was on Blu-ray.

James Bond, legendary projection magician and theatre designer/ outfitter, oversaw the shows. Although the films often looked very good on the 50+ -foot Virginia screen, his expert eye saw shortcomings in the digital versions. Even I could detect the videoish quality of Joe vs. the Volcano. It looked pretty good, but compared to what James had shown in years past—70mm prints of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, My Fair Lady—there was definitely a sense that we were passing into a new era. Above you see James between his thoroughbreds, the lovingly assembled 35/70mm projectors.

Because Steak ‘n Shake became a festival sponsor this year, Roger presented James with the first-ever S-n-S award, a cap displaying the motto, “In Sight It Must Be Right,” a fitting label for James’ superlative standards in projection. Here he receives the Order of Takhomasak.

James was ably assisted by Steve Kraus and Travis Bird, who is both a musician and a cinephile. Great guys and great professionals, all.

The Virginia Theatre, an analog artifact if there ever was one, is closing after Ebertfest this year. It will be renovated and spiffed up, with new seats and many other upgrades.

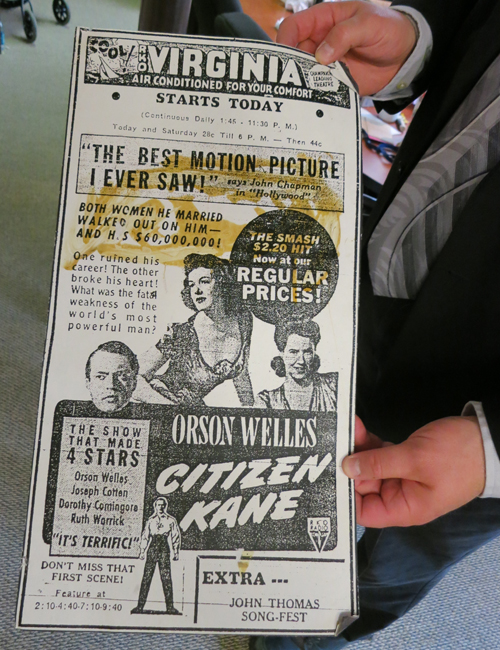

The festival wrapped up with Citizen Kane brought to us digitally. A Blu-ray copy was screened, and instead of the film’s original track, we heard Roger’s pointed and wide-ranging 2001 commentary. He was by this point an old hand at play-by-play explication, after years with his “Cinema Interruptus” series, now taken over by Jim Emerson. After the screening, I was happy to be able to interview Jeff Lerner, of Blue Collar Productions. Jeff produced and recorded Roger’s commentary. Again, check the Ebertfest channel if you want to see the Q & A, which takes off after Chaz’s moving memoir.

Thanks to the many staff and guests who made this year’s Ebertfest especially enjoyable. I’m particularly grateful to C. O. “Doc” Erickson for giving me an interview for an upcoming blog entry, and to David Poland and Michael Barker for enlightening table talk. Thanks as well to Jim Emerson, excellent companion of the highway.

Thanks to Kat Spring and Nate Kohn for correction of boo-boos.

Speaking of digital, here’s a neat possibility: http://gizmodo.com/5906353/the-avengers-screening-delayed-because-some-dunce-deleted-the-freaking-movie.

This deserves a blog entry of its own. The hands belong to Steven Bentz, Virginia Theatre Director, whom we must thank for preserving this ad (from, I assume, 1941). Note the listing of start times for the feature, and the request not to miss the opening. This is a topic discussed elsewhere on this site.