Archive for the 'Directors: Welles' Category

John Ford and the CITIZEN KANE assumption

Kristin here:

A few days ago I was reading the February 24 issue of Entertainment Weekly. I started subscribing to EW during the days when I was working on The Frodo Franchise. Being a Time Warner publication, it tended to feature The Lord of the Rings a lot (Time Warner also owns New Line Cinema). I was trying to keep track of the popular-press coverage of the film, and EW was a helpful source. It also used to be a bit more substantive in those days. In recent years it has become more fluffy. Still, it’s handy for reading over lunch or when brushing one’s teeth.

Turning to page 66, I found Chris Nashawaty’s “The Most Overrated Best Picture Winners.” The double-page spread was slathered with photos of My Fair Lady, Out of Africa, Gandhi, The King’s Speech, and Shakespeare in Love. (The piece is online, but as a gallery rather than an article, lacking the introduction.)

I like putdowns of overrated and/or over-rewarded films as much as anyone, so I settled in to read. I was shocked, however, to find that the first film on the list was How Green Was My Valley.

I happen to think the How Green is one of the very greatest American films. Probably no Best Picture winner in the history of the Oscars has been a more fitting recipient of that award. Why lump it in with Shakespeare in Love?! (I think you know what’s coming.)

Nashawaty gives his reasons. He admits that How Green has three pluses going for it: “It’s got beautiful cinematography, John Ford as a director, and a three-hankie plot about a Welsh mining village.” He goes on: “The minuses: mismatched accents and the still-outrageous fact that it beat Citizen Kane.”

Mismatched accents as a reason not to win Best Picture? The notion belittles the brilliant ensemble acting in Ford’s film, with Donald Crisp, Sarah Allgood, Barry Fitzgerald, Maureen O’Hara, Walter Pigeon, and many others giving fabulous performances, career bests in some cases. It is a joy to watch them interact. Of course most of these people sound more Irish than Welsh, but frankly, who cares?

By the way, I’m assuming Nashawaty means the mismatch of Irish accents to a Welsh setting, not a miscellany of accents among the cast, which is common in Hollywood films. Besides, isn’t accuracy of accents—think Meryl Streep—one of the criteria used to judge the very Oscar-winners that Nashawaty is decrying? I’ve never seen Gandhi, but I’ll bet Ben Kingsley did a heck of an authentic accent. Accents are one of the easiest aspects of performances to notice, so it’s not surprising that they are so often a factor in Oscar-nominated and -winning roles.

But it’s not really the accents that bother people about How Green. No, it’s really the “beat Citizen Kane” part that grates on film fans. Quite possibly it has led them to dismiss or undervalue one of Ford’s greatest films.

I’m going to be heretical and say that How Green deserved to win over Kane.

For years Kane has been sitting atop many lists of the greatest films of all times, including polls of professional film critics. The notion that Kane really is the greatest film of all time has become so engrained that people seem seldom to question it. Back when that idea arose, critics were unaware of the films of Yasujiro Ozu, probably the world’s greatest film director to date. Play Time was for years ignored and only recently has begun to be recognized for the masterpiece it is. With the rise of film restoration in the 1970s and the spread of film festivals and retrospectives, we now know vastly more about world cinema than we did before. Yet Kane has settled into its top slot for many people, including entertainment journalists. I can think of many films I would rank above Kane.

No doubt it’s a great film, with a marvelously tricky plot, another great ensemble of actors, splendidly distinctive cinematography, and innovative special effects masquerading as cinematography. It was hugely influential at the time and remains so to this day. Of course, Welles has declared time and again that he learned filmmaking by watching Stagecoach over and over, so Kane would probably not be as good as it is without Ford’s influence. Not that such influence proves that How Green is better than Kane, but it shows Welles’s respect for Ford. More on that below.

Middlebrow and proud of it

I think another reason why How Green tends to be dismissed as merely the film that cheated Kane out of its best-picture Oscar is that it is resolutely middlebrow. Indeed, in that way it fits in with all the other films Nashawaty writes about. They’re all resolutely middlebrow, too. Middlebrow films are for those people who look down upon popular genres and want to feel they’re seeing something worthwhile.

Despite this attitude, most of the great American films fit into popular genres: Keaton’s The General (or substitute your favorite Keaton film), Kelly and Donen’s Singin’ in the Rain, and Hitchcock’s Rear Window (or, if you will, Shadow of a Doubt or Notorious or Psycho). This is one thing that the auteur theory, somewhat indirectly, taught us. Howard Hawks’s modern reputation rests partly on his ability to waltz into any American genre and make one of its best entries. The Godfather is technically a gangster film, but one could argue that by taking it from a bestseller and making it into a glossy A picture, Coppola pushed his film into the middlebrow range far enough for the Academy to dub it Best Picture—twice. The one Best-Picture winner of recent decades that arguably did thoroughly deserve the prize was a serial-killer thriller, The Silence of the Lambs. I think a lot of people were surprised that the strait-laced Academy members could accept such subject matter in a nominee, let alone a winner.

Like Hawks, Ford moved easily among genres and excelled at least once in every one he touched. He made arguably the greatest war film ever, the underrated They Were Expendable, and the greatest Western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (or Stagecoach or My Darling Clementine). He also pulled the turgid middlebrow genre of the 1930s biopic into greatness with Young Mister Lincoln. There’s no doubt that Ford was an uneven director, and arguably his worst films arose from his attempts to go for middlebrow respectability. The Fugitive is almost unwatchable in its pretentiousness, and the mid-1930s brought forth such items as Mary of Scotland and The Informer. But starting in 1939, he produced an almost unbroken string of masterpieces and near masterpieces, culminating in They Were Expendable and My Darling Clementine.

We should recall also that Welles himself adapted a middlebrow bestseller for the film he made directly after Kane: The Magnificent Ambersons. Had the studio not meddled so extensively with it, it probably would have been one of the American cinema’s great middlebrow classics, fit to sit alongside How Green.

Earned sentimentality

Welles himself probably would have felt honored by that comparison. In a 1967 interview he described his taste in films:

Old masters—by which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford. With Ford at his best, you feel that the movie has lived and breathed in a real world—even though it may have been written by Mother Machree.

In other words, Welles recognized that sentiment did not take away from the brilliance of Ford’s best work, and How Green is definitely in that category. Welles was too big an egotist not to have been annoyed at losing the Best Picture award to Ford, but he probably understood why How Green won better than most people do today. Today, apart from groups of women who go to see heartwarming female-oriented fare, audiences tend to shy away from sentimentality.

To his credit, Nashawaty lists sentimentality as a plus for How Green. (“Three-hankie plot” has a dismissive ring to it, but I’ll chalk that up to the requirements of infotainment journalese.) But I’m sure that many people who underrate How Green do so because it’s essentially a family melodrama where everything starts out in an Edenic state and the situation slowly goes downhill to a distinctly unhappy ending for all concerned. A lot of people simply dismiss sentimentality in all its manifestations, presumably as too naive, hitting us below the belt for an easy emotional appeal. In this day and age, it is much easier to admire cynicism than unembarrassed emotion. Despite its subject matter of environmental depredation by greedy companies, How Green is resolutely focused on the joys and sorrows of the family. Kane is cynical in a very modern way. Yet I cannot believe that we care nearly as much about the characters in Kane, even Susan, as we do in How Green.

Sentimentality is not a bad thing in itself. Sure, it’s an easy thing to evoke. Easy sentimentality is banal and cloying because there’s so little underpinning it except conventional romance and cute babies and long-suffering mothers and the like. Then there is what I call earned sentimentality. (A similar distinction is often made between sentiment and sentimentality.) Films with this quality are rich with original characters and situations that might make even a viewer who dismisses easy sentimentality pull out a hankie. The sentimentality in Chaplin’s films sometimes achieves this, and his Little Tramp character has been widely praised over the decades for his mastery of this emotion. Even those who dismiss sentimentality can forgive Chaplin, since humor usually undercuts the cloying quality just a bit. In a less obvious way, Harold Lloyd sometimes proves himself a master of sentimentality, as in The Kid Brother. And earned sentiment is not dead. It pervades Big Fish, another film that has been underrated or at least largely forgotten, perhaps in part due to its sentimentality. It has eccentrics galore and an original plot idea, but it doesn’t have that edgy, weird quality that sophisticated viewers treasure in Tim Burton’s work. There’s even sentimentality in the Wallace & Gromit films, though again humor makes the emotion palatable. Art cinema has its own sentimental masterpieces: Bicycle Thieves, Jules et Jim, Tokyo Story, Sansho the Bailiff, Distant Voices, Still Lives, and the list could go on and on. True, all these films are grimmer in part or in whole than the average Hollywood film, but so is How Green.

By the way, Welles himself delivers one of the sublime sentimental passages of world literature in the heartbreakingly nostalgic “chimes at midnight” speech in Falstaff, which has other passages of the same emotion. The Magnificent Ambersons is a sentimental film of a different sort.

For my money, How Green earns its sentimentality as well as any film ever made.

On everyone’s syllabus

You may be asking at this point, if How Green is so fantastic, why didn’t Bordwell and Thompson use it as their central example of a narrative film in Film Art? Why is Kane in that spot? There’s a simple answer to that: Kane is a very teachable film, and How Green, to say the least, is not. Our challenge was to find a film that most teachers used, or would happily start to use, and that demonstrated many concepts about film narrative and style that we wanted to describe.

Some films are just more teachable than others. They use a lot of different techniques, both stylistic and formal, in a way that students can notice. Hitchcock is probably the most teachable director overall, and I would bet that his films show up on introductory-film-class syllabi more often than any other director’s. It’s just that with Hitchcock, there’s no one film that’s self-evidently more useful for teachers than others. I sometimes think that one could almost write an entire introductory textbook using nothing but examples from Lang’s M. There are other classics like that. But Kane beats them all: a complex but clear flashback structure, obvious and varied technique, a complex soundtrack born of Welles’s radio experience, and examples of many things teachers want their students to learn about. It’s a classical Hollywood film, but it has touches of art-cinema ambiguity about it. It’s entertaining, at least to motivated students, so they’re likely to pay attention rather than dismissing it. They may come into the class knowing that it’s a revered classic and hence be interested in seeing it. It may even reconcile them to watching black-and-white films.

How Green, however, is difficult to teach. David has found this to be true. Our colleague Lea Jacobs occasionally offers a seminar on Ford, and How Green is among the most challenging films by a director whom students tend to be slow to warm up to. She attributes this partly to changing tastes and partly to the subtlety of the style of its cinematography. It’s very hard to make students, and indeed almost anyone who isn’t already a believer, see why How Green is a masterpiece.

Kane is not only teachable, but it’s highly conducive to analysis, and no doubt these two traits are closely related. David’s first widely seen article was a study of Kane, and I wrote the sections of chapters in Film Art dealing with it. I don’t mean that it’s simple; Kane is a complex film that has provided material for many different essays and books. But How Green has so many ineffable qualities that it resists cold, precise analysis. It has been one of my favorite films for over three decades, and occasionally I have contemplated writing something in-depth about it. I can’t, however, think what one could possibly write. One would just have to throw up one’s hands and say, “You either get it or you don’t.”

It reminds me of when I was nearing the end of my undergraduate career. I didn’t “get” Godard. I found his work pretentious and boring. But given how many people whose opinions I respected admired Godard, I persisted. I think I suffered through seven features, and at about number eight (Weekend), I got Godard. Maybe Ford, at least for his non-Western films, is somewhat the same sort of challenge. I’ve written analyses of two of Godard’s more difficult films, Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie). I’m still scared to try to deal with How Green.

(Stagecoach is much easier. For several editions of Film Art we included an analysis of it, which I wrote. Eventually it got replaced, but it’s still available here.)

A few hints

Since I doubt I will ever thoroughly analyze How Green, here I’ll offer just a few hints as to why it deserved to take home Best Picture and leave Kane an also-ran.

Nashawaty mentions the beautiful cinematography. Arthur C. Miller was 20th Century-Fox’s A-list cinematographer, having shot some of the Shirley Temple films in the 1930s, films that kept the studio afloat during the Depression. He teamed with Ford only on Tobacco Road and How Green, though he apparently helped with Young Mr. Lincoln uncredited. Miller won his first Oscar for How Green, his second for Henry King’s The Song of Bernadette (the main virtue of which is it looks a lot like How Green), and his third for Anna and the King of Siam. Few of Miller’s non-Ford films like The Ox-Bow Incident and Gentlemen’s Agreement are watched much today. He did lens somewhat minor films by major directors (Hitchcock’s Lifeboat, Preminger’s Whirlpool), but he is less famous than he deserves.

Just a few examples. How Green contains some of the same techniques that are so admired in Kane, but in a less flamboyant fashion. Deep focus, for example:

Admittedly, the people at the right rear are slightly out of focus, but the shot was done in-camera. No special effects.

The interiors of How Green have a distinctive touch: patches of light on the ceilings. Implausible, when you start to think about where the light must be coming from, but beautiful nonetheless. Miller (or at least Fox) almost had a patent on this way of lighting a room. With Kane getting so much credit for adding ceilings to sets, we should remember that Ford has done so in Stagecoach and does it here as well. It’s not as in-your-face as Kane’s ceilings, but it’s an example of the subtlety that pervades How Green. The first shot (below) is part of the series of scenes at the beginning setting up the happy home life of the large and relatively prosperous Morgan family; the father is about to dole out allowances to his sons on payday. The second comes much later, as the last two grown sons prepare to depart abroad in search of work after the mine has declined.

Kane is admired for both its long takes and its dynamic editing. Ford seldom used either. He held a shot long enough to be effective but not long enough to turn into showing-off. Take the scene after Angharad’s marriage to the wealthy mine-owner’s son. Mr. Gruffydd, the minister whom she actually loves, has performed the ceremony. As has been pointed out many times, Ford filmed the final shot without doing any close views to be cut in later. (Indeed, most of How Green was edited in the camera by Ford, so that most of the footage he shot ended up on the final version. It was his way of keeping control over his film.) By happy accident, a breeze caught Angharad’s veil, sending it soaring and twisting through the shot. Perhaps it was a reflex gesture on the part of the actor playing the mine-owner’s son, but he reaches out and holds the veil down as his bride climbs into the coach; it perfectly captures his cold, proper nature. For a split second before the coach pulls away out right, Angharad glances back toward the church, where Gruffydd remains inside. Once the coach is gone, Ford holds, and Gruffydd appears on the hillside at the rear, watching and then turning to go inside. No cut-in mars the perfection of the shot.

There’s one of the hankie moments. I get tears in my eyes during this scene, partly out of sympathy of the sundered couple and partly from aesthetic pleasure. If ever there was a single shot that exemplifies Ford’s combination of sentiment and discretion, this is it.

The last of these five frames belongs to the visual motif that appears in the opening sequence, as Angharad waves to her father and Huw on the beautiful distant hillside (see above), as well as in the final scene, where Angharad struggles in her fine clothes across a similar hillside, swathed in smoke, to reach the mine after the disaster that traps her father (see below). Such moments create a quiet measure of the gradual degradation of the valley and the dwindling of the family’s happiness.

Did Ford realize how brilliant this shot was? We can be confident that Welles was well aware of how daring and wonderful his techniques in Kane were. It shows in the film. With Ford, one can only suspect that he knew exactly what he had accomplished here and elsewhere.

Another thing How Green shares with Kane is a flashback structure. It largely consists of one big flashback told by the protagonist, not a series of embedded stories by witnesses. Nevertheless it’s unusual, since we never come out of the flashback. The tale opens with the valley in severe decline, the village nearly deserted, and the hero about to depart for a better life. We witness the decline of his family as he grows, gets educated, and opts to follow his father and brothers into a job in the mine. By the end his elder brothers have scattered all over the world, his father is dead, and we don’t know what has become of his mother and sister. (One plausible assumption is that his mother has recently died, prompting his departure in the opening scene.) Yet the ending gives us a series of shots of the family as they had been in their prime, with the protagonist-narrator declaring, “Men like my father can never die.” Like Kane, it is a film about the power of memory, but in this case the power to comfort rather than to baffle.

One thing that makes How Green stand apart from some of Ford’s other films is that it for once controls the director’s penchant for mixing in broad humor. His stable of supporting actors playing minor characters who love to drink and fight can be trying. There is a particularly ill-advised moment in The Searchers when, after the epiphanic moment when Ethan has lifted Debbie as if to kill her and then embraced her, Ford cuts to the Ward Bond character having a wound on his posterior dressed, to the derision of his comrades. That Ford should undercut such a scene with a vulgar moment of comedy combines with another flaw or two in the film keep if off my list of Ford’s very best films. And much though I love the first three-quarters of The Quiet Man, that climactic brawl just goes on and on.

In How Green, the characters Dai Bando and Cyfartha provide humor, but they are held in check. They play reasonably significant roles in the action, helping Huw deal with the school bullies and his sadistic teacher. Many of the family scenes involve amusing moments as well, moments that arise naturally from the situations and have no air of mere comic relief. In screenwriter Philip Dunne’s introduction to the published version of his screenplay, he finds fault with several scenes and actors. Maybe he’s right that the scene when the mine owner visits the Morgan family is played for broad comedy, but it’s not as broad as elsewhere in Ford’s work. Luckily Ford’s brother Francis does not return for yet another of his bit parts as a drunk.

In 1972, when Ford was dying of cancer, the Directors Guild held an evening gathering to honor him. He was asked to choose one of his films to be projected, and he named How Green. He had consistently said he considered it his finest film.

There’s no budging Kane

I doubt that the notion of Citizen Kane as the Greatest Film of All Time will go away anytime soon. Changing (and unchanging) tastes are reflected in the decadal Sight & Sound poll of critics concerning the ten greatest films of all times. They started in 1952 and have continued to 2002, with another due this year. The lists reflect the fact that apparently critics can somewhat agree on the greatest older classic, though fashions in these come and go, but they cannot agree on much of anything that has been made since 1970:

1952

- 1. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica)

- 2. City Lights (Chaplin)

- 2. The Gold Rush (Chaplin)

- 4. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 5. Intolerance (Griffith)

- 5. Louisiana Story (Flaherty)

- 7. Greed (von Stroheim)

- 7. Le Jour se lève (Carné)

- 7. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 10. Brief Encounter (Lean)

- 10. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

1962

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 3. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 4. Greed (von Stroheim)

- 4. Ugetsu Monogatari (Mizoguchi)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica)

- 7. Ivan the Terrible (Eisenstein)

- 9. La terra trema (Visconti)

- 10. L’Atalante (Vigo)

1972

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 4. 8½ (Fellini)

- 5. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 5. Persona (Bergman)

- 7. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 8. The General (Keaton)

- 8. The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles)

- 10. Ugetsu Monogatari (Mizoguchi)

- 10. Wild Strawberries (Bergman)

1982

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Seven Samurai (Kurosawa)

- 3. Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly, Donen)

- 5. 8½ (Fellini)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 7. The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles)

- 7. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 10. The General (Keaton)

- 10. The Searchers (Ford)

1992

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Regle du Jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Tokyo Story (Ozu)

- 4. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 5. The Searchers (Ford)

- 6. L’Atalante (Vigo)

- 6. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 6. Pather Panchali (Ray)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 10. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

2002

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 3. La Regle du Jeu (Renoir)

- 4. The Godfather, parts I and II (Coppola)

- 5. Tokyo Story (Ozu)

- 6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

- 7. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. Sunrise (Murnau)

- 9. 8 ½ (Fellini)

- 10. Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly and Donen)

There is much that could be said about these lists. Most readers will probably be astonished to see Bicycle Thieves at the head of the first list, with Kane not even present. Brief Encounter above La Regle du jeu. Louisiana Story, of all things, and Le Jour se léve. By 1962, tastes had changed. Italians won the day, with three films, while Eisenstein, whose Ivan the Terrible, Part 2 had finally been released in 1957, had two films chosen. Two French films and two American. But it was in this year that Kane appeared, immediately bouncing to number one, a position from which it has never budged. I suspect it will sit atop the 2012 list, simply because now so many critics assume it’s the best film ever–and even if they don’t assume that, they won’t be able to agree on an alternative.

Ford has had only one film on the lists, The Searchers, in 1982 and 1992. For a time it was the Ford film du jour, until in 1992 Hitchcock zipped past it with Vertigo, which settled into the second spot after Kane in 2002. Mizoguchi has been on only one list, in 1972 with Ugetsu Monogatari. Ozu’s first film to became well known in the west didn’t make the list until decades later, in 1992, and yet despite the discovery of Late Spring and Early Summer and An Autumn Afternoon, Tokyo Story remains the Ozu film. Tati has never appeared on the list. Neither has Bresson. I’ll buy the idea that critics are out there voting for Bresson like mad, but all for different films. But Play Time, surely one of the very greatest films ever made, should be easy to converge around. Finally, the only post-1970 film on here (and not by much) is the Godfather pair. I was still working on my master’s degree when the first one came out.

I suppose by now, with so many smaller countries starting to make movies and so many festivals making them widely available, it becomes impossible to anoint new classics in the way critics used to. Kiarostami’s Koker Trilogy, in whole or in part, would seem to be such a classic, but there are so many great competing films. Does one have enough perspective to choose more recent films when others, like Sunrise, have stood the test of time? Play Time is 45 years old now, and I think it’s a greater film than most of those on the 2002 list–certainly including the number one. Possibly it will make the list this year.

Why is Kane so fixed at the top, when other films move up and down and ladder, and some appear and disappear? Perhaps the simple assumption that if it has been up there so long, it must really be the greatest film ever made.

I think this business of polls and lists for the greatest films of all times would be much more interesting if each film could only appear once. Having gained the honor of being on the list, each title could be retired, and a whole new set concocted ten years later. The point of such lists, if there is one, is presumably to introduce people who are interested in good films to new ones they may not have seen or even known about.

Such an approach is not wholly unthinkable. Each year the National Film Registry maintained by the Library of Congress chooses 25 films deemed to be national treasures worthy of special priority in preservation. There’s probably some assumption that the best films were on the early lists and that each new 25, especially coming annually rather than at longer intervals, must be of less interest than its predecessors. But on the whole it’s a pretty egalitarian exercise, one that treats all kinds of films as fair game, not just fiction features, and it really does draw attention to obscure films that deserve to be better known. Given how many films have been made in the USA, it will be a long time before the Registry is scraping the bottom of the cinematic barrel. The entire world could supply so many more.

At any rate, I don’t insist that justice will not be done until How Green or some comparable Ford masterpiece appears on Sight & Sound‘s poll, any more than I would say that it’s having won the Best Picture Oscar proves that it’s a great film. I think we all know that the whims of the Academy members are hard to fathom, then and perhaps even more so now. But why call it overrated just because it beat Kane for that dubious honor? If anything, How Green is underrated for that very reason. Had it been made in a different year and won the Oscar against some other films that weren’t Kane, would it be any better or worse?

If you have never seen How Green and are not wholly opposed to earned sentimentality, give it a try. Just make sure you have at least three hankies handy.

PS March 8, 2012. Our friend Antti Alanen points out that Maureen O’Hara said the shot with the veil was carefully planned. She disagrees with Philip Dunne’s claim that the wind catching it was a happy accident, as Joseph McBride recounts in Searching for John Ford:

Dunne thought Ford had “one of the greatest strokes of luck a director ever had” when the wedding veil suddenly caught a gust of wind and billowed behind Mareen O’Hara as she walked down the steps from the church. O’Hara recalled, “Everybody said, ‘Oh, that Ford luck! How wonderful that was! What an effect it has!’ Rubbish! It wasn’t ‘Ford luck.’ It was three wind machines placed by John Ford, and I had to walk up and down those steps many times while he worked out that the wind machine would do exactly that.” As she climbs into the carriage, the ator playing her husband, Marten Lamont, reaches out to catch her veil. Dunne thought, “The man shouldn’t have touched it when the veil spiraled up. My God, what a shot! Luckily, Joe LaShelle, who was the operator, just gave it a little tilt with the camera.” I told Dunne I thought the gesture of restraining the veil (probably planned by Ford, like the rest of this meticulously composed shot) is an eloquent metaphor for the repressiveness of Angharad’s loveless marriage. “Well, I guess so,” the screenwriter responded. “I didn’t think beyond that. I said, ‘My God, you get a break like that, you leave it alone.'” (p. 332)

PPS March 11, 2012. Thanks to Przemek Kantyka for pointing out that Ugetsu actually figured on the 1962 and 1972 lists.

An all-too-short visit to Ebertfest 13

Tulip’s unique way of expressing delight at the prospect of walkies.

Kristin here–

With David still recovering from pneumonia, I drove down to Champaign-Urbana by myself for a truncated Ebertfest visit. As always,  the event began with a reception at the president’s home, where Roger delivered a speech via his talking computer (left).

the event began with a reception at the president’s home, where Roger delivered a speech via his talking computer (left).

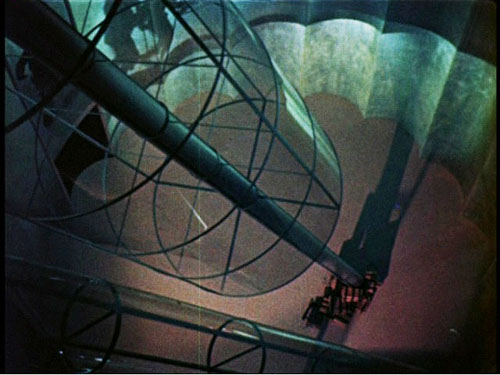

This year, rather than kicking off the festival with a Wednesday-night screening of a 70mm print, the opening program was a screening of the restored version of Metropolis, incorporating footage found in Argentina. (David has already blogged about the new version, having seen it last year at the Hong Kong Film Festival.) I had the privilege of introducing the screening.

Roger’s program notes gave a good summary of the film and its latest restoration, so I talked a little about why it’s not all the odd that a nearly complete print should be found in Argentina. First there’s the matter of what happened to prints at the end of their theatrical circulation in the silent era. Films didn’t open around the world day and date the way they do now. Prints might be exhibited in one country, then move onto another with new intertitles in a different language cut in. They might be shown for years, until their useful life was over. By that point they might have reached places far away from their place of origin. They were also usually covered with scratches and lines, and they weren’t worth the cost of shipping them back to their makers. They might be buried, as was the case with the 1978 Dawson City find in Alaska, or stored in the attic of a theater, or rescued by a projectionist who tucked them away in a garage. In some cases, collectors acquired them, as happened with the Argentinian Metropolis print. Occasionally these treasures come to light, as recently happened when the Film Archive of New Zealand located several American titles, such as John Ford’s lost silent film Upstream. So far-flung places that long ago were the end of the line for prints are where we might expect them to resurface. Indeed, New Zealand’s archive also held a print of Metropolis that contained some shots not found in earlier restorations or in the Argentinian print, and these appear in this latest version.

A second reason why Argentina is not a surprising place to find a long print of Metropolis has to do with the German film industry’s strength after World War I. Despite having been defeated, the country built up its production until it was second only to Hollywood. European companies found it difficult to sell their films in the U.S.; then, as now, American films dominated their domestic market. German companies sought other areas where they could compete on a more equal footing. They were quite successful in South America, and Fritz Lang’s films were among the most popular there. Small wonder, than, that a well-worn, largely complete print should survive there.

The original score has been reconstructed, but as has become customary at Ebertfest, the Alloy Orchestra supplied their own original accompaniment. (See below.)

Dog-lovers’ delight

The thing that sets Ebertfest apart from other festivals is that it reflects the taste of one person. Roger chooses the films, and his reviews are reprinted in the program as notes. When Roger saw the acclaimed animated film My Dog Tulip, based on J. R. Ackerley’s memoir about life with his Alsatian, he was reminded of another man whose only love was his dog, Umberto D. So, having the ability to program of double feature of the two films, Roger did. Apart from the annual silent film, Ebertfest seldom shows older classics, so this was something of a departure. I had only seen a 16mm copy of Umberto D, way back in my graduate-school days, so it was great to see a 35mm print on the big Virginia Theater screen.

The juxtaposition of the two films worked well, with the grim image of old age and despair of Umberto D followed by the nostalgic but fairly upbeat My Dog Tulip. Judging by the questions and comments afterward, the latter struck a particular chord with dog lovers in the audience, and during the remainder of my stay I heard many pet anecdotes exchanged among people around me.

The film was created by a husband-wife team, with Paul Fierlinger drawing on a digital tablet and Sandra Fierlinger painting in the colors with a computer program. As I pointed out during the panel discussion after Nina Paley’s Sita Sings the Blues was shown at Ebertfest in 2009, computer animation doesn’t mean that the computer does all the work. Far from it. A computer has to have a lot of material fed into it before it can aid in the filmmaking process. Each frame of My Dog Tulip was done by hand, and it has the look of traditional cel animation. (As with traditional cel animation, the Fierlingers use each image twice in a row, so that only twelve drawings suffice for a second of film.) There’s a deliberately rough, slightly jittery look to the outlines of the figures in the shots, helping give that impression of drawn animation.

Ordinarily I would have preferred to see the film in 35mm, but Paul and Sandra told me that the 35mm prints actually washed out some of the vibrancy of the intended colors. The digital print projected at Ebertfest definitely did the colors justice.

Matt Soller Zeitz with Paul and Sandra Fierlinger onstage after the screening

Filling the big screen

On Friday, two very well-known directors presented beautiful, color, widescreen 35mm prints that looked terrific–and huge–on the big screen. (I was sitting in the second row for one, the first row for the other, so the effect was particularly overwhelming.) I had missed Richard Linklater’s most recent release, Me and Orson Welles, in first run, so it was a pleasure to catch up with it. As all the reviewers remarked, Christian McKay uncannily impersonates the real Orson Welles. As Linklater pointed out, McKay was in his  mid-30s at the time of filming, while Welles was a mere 22 during the time depicted–and yet the portrayal works, since Welles didn’t really look young, even at the beginning of his career.

mid-30s at the time of filming, while Welles was a mere 22 during the time depicted–and yet the portrayal works, since Welles didn’t really look young, even at the beginning of his career.

The film pulls a great deal of humor out of rehearsals for Welles’s famous 1937 staging of Julius Caesar, with the director’s whims and ego dominating the proceedings, and Zac Efron’s stagestruck high-school kid providing a naive point of view of the backstage politicking. Given all the antics in the lead-up to the premiere, it’s impressive that Linklater manages to switch gears abruptly and present snippets from the production itself that genuinely suggest the impact of Welles’s revolutionary staging. It wowed New York and pioneered the way for modern-dress versions of the Bard’s works.

The on-stage discussion after the film revealed that the production, which manages to convey 1930s New York so convincingly, was mostly shot on the Isle of Man. The British island not only offered favorable production incentives, but it boasted a well-preserved local playhouse that could double for the long-since-destroyed Mercury Theater.

That evening veteran director Norman Jewison presented one of his less well-known films, Only You (1994). It’s a screwball, absurdly romantic comedy starring Marisa Tomei and Robert Downey Jr., both looking very young and very gorgeous.

After Jewison moved from television into feature films in the 1960s, his early projects included two Doris Day and Rock Hudson comedies (The Thrill of It All and Send Me No Flowers), and he returned to the genre with Moonstruck.

Only You has a slender plot in which the heroine, convinced that a Ouija board has given her the name of the man she will marry, abandons her fiancé to follow a man she thinks is her destined true love across Italy. Cinematography by Sven Nykvist and location shooting in Venice, Rome, and Positano give the film considerable charm.

David has been recovering well, but I didn’t want to leave him alone too long. I returned home today rather than staying through the entire festival. But it was a wonderful few days, and I enjoyed talking with Michael Barker, Paul and Sandra Fierlinger, Kevin Lee, Michael Phillips, David Poland (when he wasn’t busy chasing his lively 15-month-old son), some of Roger’s “Far-flung Correspondents,” and many of the devoted audience members who return year after year to this unique event. With luck, both David and I will be there for the whole event next year.

(From the Ebertfest website)

Note: For a second year, the introductions, post-film discussions, and morning panels were streamed live, and they’re also archived online.

Foreground, background, playground

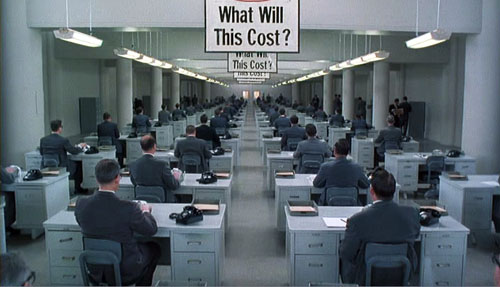

The Devil and Miss Jones (1941); The Hudsucker Proxy (1994)

DB here:

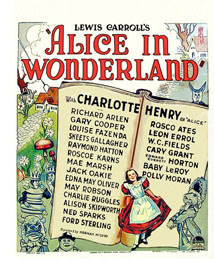

I’ve been waiting for thirty years for Alice in Wonderland. No, not the theatrical release of Tim Burton’s version. That interests me only mildly. I’m referring to the DVD release of the 1933 Paramount picture. I saw it on TV as a kid, and remembered it only dimly. But it bobbed up on my horizon in the summer of 1981 when I was doing research on our book The Classical Hollywood Cinema.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was in the old Academy library in Los Angeles studying the emergence of certain compositional schemas. I can’t recall what put me on the track, but I requested the shooting script of Alice. What came was Farciot Edouart’s copy, over six hundred pages teeming with sketches for each shot. And a lot of those shots had a startling similarity to good old Citizen Kane.

I was reluctant to attribute pioneering spirit to director Norman Z. McLeod. Instead, I realized that these images’ somewhat freaky look owed more to one of the strangest talents in Hollywood history.

I tried to see Alice in Wonderland, but I couldn’t track down a print. So for years I’ve been waiting to find if it confirmed what I saw on those typescript pages. In the meantime, for the CHC book and thereafter, I’ve bided my time, sporadically looking in on the career of one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. He’s the subject of a new web essay I’ve just posted here (or click on the top item under “Essays” on the left sidebar). Today’s blog entry is a teaser trailer for that.

Deep thinkers

It’s commonplace now to say that Citizen Kane (1941) pioneered vigorous depth imagery, both through staging and cinematography. Many of the film’s shots set a big head or object in the foreground against a dramatically important element in the distance, both kept in fairly good focus. But where did this image schema come from?

The standard answer used to be: The genius of Gregg Toland and Orson Welles. In the 1980s, however, I wanted to explore the possibility that something like the deep-focus look had been a minor option on the Hollywood menu for some time. Once you look, it’s not hard to find Kane-ish images in 1920s studio films, from Greed (1924) to A Woman of Affairs (1929).

During the 1930s, William Wyler cultivated such imagery in some films shot with Toland, such as Dead End (1937), and some films shot by other DPs, such as Jezebel (1938). In turn, Toland had undertaken comparable depth experiments in films with other directors. Moreover, yet other directors, notably John Ford, had used this sort of imagery in films shot by Toland and others, such as George Barnes, Toland’s mentor. There are plenty of non-auteur instances too. (See my post on 1933 Columbia films.) We also find similar imagery in films from outside America. Here’s a stunner from Eisenstein’s Bezhin Meadow (banned 1937).

You see how complicated it gets.

What I concluded in Chapter 27 of CHC was that Toland and Welles didn’t invent the depth technique. They fine-tuned it and popularized it. Their predecessors, in the US and elsewhere, had staged the action in aggressive depth and used many of the same compositional layouts. But the wide-angle lenses then in use couldn’t always maintain crisp focus in both planes (below, American Madness, 1932).

Welles and Toland found ways to keep both close and far-off planes in sharp focus. They deployed arc lamps, coated lenses, and faster film stock. Although it wasn’t publicized at the time, we now know that some of the most famous “deep-focus” shots were also accomplished through back-projection, matte work, double exposure, and other special effects, not through straight photography. Again, though, this tactic was anticipated in earlier films. One of my favorite examples comes from a matte shot in Mr. Moto’s Gamble (1935).

Menzies seems to have planned for similar fakery. In the script for Alice in Wonderland we find: “CLOSE UP, leg of mutton. The room and characters in the background are on a transparency.”

The flashy depth compositions of the 1920s and 1930s were typically one-off effects, used to heighten a particular moment. Welles and Toland pushed further by making the depth look central to Kane’s overall design and by featuring such imagery in fixed long takes. The prominence of Kane may have encouraged several 1940s filmmakers, such as Anthony Mann, to make the depth schema part of their repertoire. But as the style was diffused across the industry, the hard-edged foregrounds became absorbed into dominant patterns of cutting and spatial breakdown. The static long takes of Kane remained a rare option, perhaps because they dwelt on their own virtuosity.

Digging up films made around the time of Kane, I found many filmmakers experimenting with the look that Toland and Welles highlighted. You can see touches of it in The Maltese Falcon (1941) and All That Money Can Buy (1941). Above all, there are two remarkable movies directed by, of all people, Sam Wood. Our Town (1940) turns Wilder’s play (itself surprisingly melancholy) into a Caligariesque exercise.

Several shots anticipate the low-slung depth, bulging foregrounds and all, that became the hallmark of Citizen Kane a year later.

Our Town also uses postproduction techniques that yield depth-of-field effects you couldn’t get in camera.

Perhaps even more startling is Wood’s Kings Row (1942), with deep-focus imagery that occasionally rivals Kane‘s.

From the evidence I was encountering, it seemed that Welles and Toland’s accomplishment was to synthesize and push further some deep-space schemas that were already circulating in ambitious Hollywood circles. Connecting some dots, I realized that one of the earliest champions of aggressive imagery in general, not just big foregrounds and deep backgrounds, was William Cameron Menzies.

Menzies frenzies

Menzies started out as an art director, most famously for United Artists. He designed sets for Mary Pickford’s Rosita (1923, directed by Lubitsch) and several Fairbanks films, notably The Thief of Bagdad (1924). He won the first Academy Award for set design and went on to a noteworthy career—most famously as production designer for Gone with the Wind (1939). He also directed films, such as Things to Come (1936) and Invaders from Mars (1953). Most significant for my purposes, he was production designer for Our Town, Kings Row, and three other films of the early 1940s directed by Sam Wood. And he designed the 1933 Alice in Wonderland. The drawings I saw in Edouart’s script were by Menzies or his assistants.

Menzies was one of the chief importers of German Expressionist visuals to the US. Although his early efforts leaned toward Art Nouveau effects, by the end of the 1920s he was cultivating a dark, contorted look keyed to the harsh geometry of city landscapes.

Since the late 1920s, Menzies had explored the possibility of steep depth compositions. He didn’t usually employ a big foreground, but he did favor overwhelming perspective–either abnormally centered or abnormally decentered. Here is his sketch for Roland West’s Alibi (1929) and the shot from the finished film.

Menzies loved slashing diagonals created by architectural edges and worm’s-eye viewpoints. The harrowing opening of Things to Come is full of such flashy imagery.

Menzies calmed his style down for GWTW, although the sequences he directed bear traces of his inclinations. And in his work for other directors he managed to slip in a few odd shots. Here, for instance, is a typically maniacal central perspective view from H. C. Potter’s Mr. Lucky (1943). Squint at this image and you’ll see that it’s weirdly symmetrical across both horizontal and vertical axes.

When he met Sam Wood, it seems, Menzies found a director ready to let his imagination roam further. In these collaborations, we get depth shots à la Welles and Toland, but also skewed perspectives. Pride of the Yankees (1943/44) searches for ways to make a baseball stadium look like a Lissitzky abstraction.

Menzies subjects the partisans of For Whom the Bell Tolls (1944) to his sharp diagonals as well.

Alice, we hardly knew ye

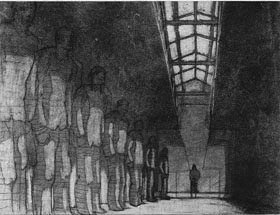

What then of Alice in Wonderland? Back in the early 1980s, I wasn’t permitted to photocopy or photograph script pages. Here is one of the few sketches I later found for the film. Alice crawls into the mirror with looming armchairs in the foreground.

Surely, I thought, the film would be an early example of the depth aesthetic that would be developed by Welles, Wyler, and Wood/ Menzies. Alas, the film has nothing like those imperious armchairs.

In fact, Alice proves a huge disappointment on the pictorial front. Menzies expended all his ingenuity on the special effects, coordinated by Paramount master Farciot Edouart. Although the spfx are not in the league of that other big 1933 effects-film King Kong, they are pretty solid for the time. It’s just that this remains a painfully arch, flatly filmed exercise.

But I look on the bright side. Menzies created some memorable movies, both on his own and with other directors. (Of his directed films, not only Things to Come but Address Unknown, 1944, remain of interest today.) Perhaps most important, his stylistic boldness may have encouraged other filmmakers to try something fresh. Most immediately there is Since You Went Away (1944), a big Selznick production that bears traces of the Menzies touch.

More broadly, Menzies represents a strand in American cinema that never really disappeared. His frantic Piranesian perspectives, canting the camera and filling the frame with grids, whorls, and cylinders, are still in use. And his head-on, wide-angle grotesquerie looks ahead to the Coen brothers. This shot of a department-store manager in The Devil and Miss Jones (1941) could come from any of their films.

Menzies’ films, though mostly not celebrated as classics, gave American cinema the permission to be peculiar. Meet me in the sidebar for a closer look at one of Hollywood’s most eccentric creators. Special thanks to Meg Hamel for going beyond the call of duty in posting that essay.

Invaders from Mars (1953); Shutter Island (2010).

Do filmmakers deserve the last word?

DB here:

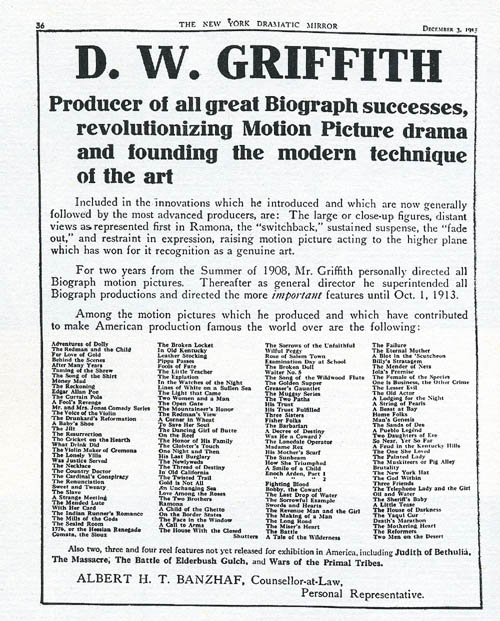

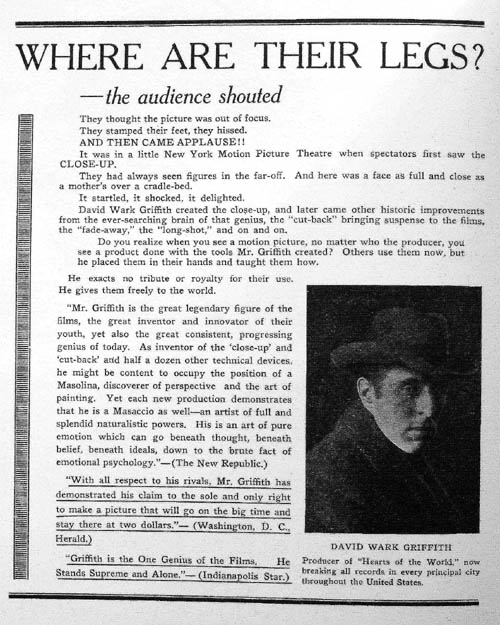

On 3 December 1913, the above advertisement appeared in the New York Dramatic Mirror. D. W. Griffith had left the American Biograph company and set out on an independent path that would lead to The Birth of a Nation and beyond. Because Biograph never credited directors, casts, or crews, he wanted to make sure that the professional community was aware of his contributions. Not only did he point out that he had made several of the most noteworthy Biograph films; he also took credit for new techniques. He introduced, he claims, the close-up, sustained suspense, restrained acting, “distant views” (presumably picturesque long-shots of the action), and the “switchback,” his term for crosscutting—that editing tactic that alternates shots of different actions occurring at the same time.

Griffith’s bid for credit was a shrewd move for his career, and it had repercussions after the stunning success of The Birth of a Nation two years later. Many historians took Griffith at his word and credited him with the breakthroughs he listed. He became known as the father of “film grammar” or “film language.” The idea hung on for decades. Here’s the normally perceptive Dwight Macdonald, criticizing Dreyer’s Gertrud for being anachronistic:

He just sets up his camera and photographs people talking to each other, usually sitting down, just the way it used to be done before Griffith made a few technical innovations. (1)

Filmmakers believed the Griffith story too. Orson Welles wrote of the “founding father” in 1960:

Every filmmaker who has followed him has done just that: followed him. He made the first close-up and moved the first camera. (2)

In the late 1970s a new generation of early-cinema scholars gave us a more nuanced account of Griffith’s place in history. They pointed out that most of the innovations he claimed either predated his Biograph work, (3) or appeared simultaneously and independently in Europe and in other American films. Some Griffith partisans had already conceded this, but they maintained that he was the great synthesizer of these devices, and that he used them with a vigor and vividness that surpassed the sources.

That judgment seems right in part, but Eileen Bowser, Tom Gunning, Barry Salt, Kristin Thompson, Joyce Jesniowski, and other early-cinema researchers have drawn a more complicated picture. (4) Griffith did speed up cutting and devote an unusual number of shots to characters entering and leaving locales. But these innovations weren’t usually recognized as original by previous historians. More interestingly, much of what Griffith did was not taken up by his successors. His technique was idiosyncratic in many respects. By 1915 younger directors like Walsh, Dwan, and DeMille were forging a smoother style that would be more characteristic of mainstream storytelling cinema than Griffith’s somewhat eccentric scene breakdowns. Instead of creating film language, he spoke a forceful but often unique dialect.

The New York Dramatic Mirror ad coaxes me to reflect on how filmmakers have shaped critics’ and historians’ responses to their work. Hawks and Hitchcock developed a repertory of ideas, opinions, and anecdotes to be trotted out on any occasion. Today, directors write books, give interviews, appear on infotainment shows, and provide DVD commentary. We know that many of the talking points are planned as part of the film’s publicity campaign, and journalists dutifully follow the lead. (In Chapter 4 of The Frodo Franchise, Kristin discusses how this happened with Lord of the Rings.) For many decades, in short, filmmakers have been steering critics and viewers toward certain ways of understanding their films. How much should we be bound by the way the filmmaker positions the film?

Deep focus and deep analysis

Citizen Kane (1941).

Determining intentions is tricky, of course. Still, I think that in many cases we can reconstruct a plausible sense of an artist’s purposes on the basis of the artwork, the historical context, surviving evidence, and other information. (5) This may or may not correspond to what the artist says on a particular occasion. For now, I want simply to point to one instance in which filmmakers have shaped critical uptake, with results that are both illuminating and limiting.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, André Bazin, one of the great theorists and critics of cinema, argued that Orson Welles and William Wyler created a sort of revolution in filmmaking. They staged a shot’s action in several planes, some quite close to the camera, and maintained more or less sharp focus in all of them. Bazin claimed that Welles’ Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons and Wyler’s The Little Foxes and The Best Years of Our Lives constituted “a dialectical step forward in film language.”

Their “deep-focus” style, he claimed, produced a more profound realism than had been seen before because they respected the integrity of physical space and time. According to Bazin, traditional cutting breaks the world into bits, a series of close-ups and long shots. But Welles and Wyler give us the world as a seamless whole. The scene unfolds in all its actual duration and depth. Moreover, their style captured the way we see the world; given deep compositions, we must choose what to look at, foreground or background, just as we must choose in reality. Bazin wrote of Wyler:

Thanks to depth of field, at times augmented by action taking place simultaneously on several plane, the viewer is at least given the opportunity in the end to edit the scene himself, to select the aspects of it to which he will attend. (6)

While granting differences between the directors, Bazin said much the same about Welles, whose depth of field “forces the spectator to participate in the meaning of the film by distinguishing the implicit relations” and creates “a psychological realism which brings the spectator back to the real conditions of perception” (7).

In addition, Bazin pointed out, this sort of composition was artistically efficient. The deep shot could supply both a close-up and a long-shot in the same framing—a synthesis of what traditional editing had given in separate shots. Bazin wove all these ideas into a larger theory that cinema was inherently a realistic medium, bound to photographic recording, and Welles and Wyler had discovered one path to artistic expression without violating the medium’s biases.

There are many objections to Bazin’s argument, some of which I’ve rehearsed in On the History of Film Style. My point here is that Bazin was presenting analytical points that stemmed from publicity put out by Welles, Wyler, and especially their talented cinematographer Gregg Toland.

In a 1941 article in American Cinematographer, Toland talked freely about how he sought “realism” in Citizen Kane. The audience must feel it is “looking at reality, rather than merely a movie.” Key to this was avoiding cuts by means of long takes and great depth of field, combining “what would conventionally be made as two separate shots—a close-up and an insert—into a single, non-dollying shot.”(8) Toland defended his sometimes extreme stylistic experimentation on grounds of realism and production efficiency, criteria that carried some weight in his professional community of cinematographers and technicians. (9)

Toland’s campaign for his style addressed the general public too. For Popular Photography he wrote an article (10) explaining again that his “pan-focus” technique captured the conditions of real-life vision, in which everything appears in sharp focus. A still broader audience encountered a Life feature in the same year (11), explaining Toland’s approach with specially-made illustrations. Two samples show selective focus, one focused on the background, the other on the foreground.

An accompanying photo shows pan-focus at work, with Toland in frame center, an actor in the background, and Toland’s camera assistant in the foreground.

In sum, Toland’s publicity prepared viewers, both professional and nonprofessional, for an odd-looking movie.

Throughout the 1940s, Welles and Wyler wrote and gave more interviews, often insisting that their films invited greater participation on the part of spectators. In a crucial 1947 statement, Wyler noted:

Gregg Toland’s remarkable facility for handling background and foreground action has enabled me over a period of six pictures he has photographed to develop a better technique for staging my scenes. For example, I can have action and reaction in the same shot, without having to cut back and forth from individual cuts of the characters. This makes for smooth continuity, an almost effortless flow of the scene, for much more interesting composition in each shot, and lets the spectator look from one to the other character at his own will, do his own cutting. (12)

Some of this publicity material made its way into French translation after the liberation of Paris, just as Kane, The Little Foxes, and other films were arriving too. Bazin and his contemporaries picked up the claims that these films broke the rules. Deep-focus cinematography became, in the hands of critics, a revolutionary new technique. They presented it as their discovery, not something laid out in the films’ publicity.

But the case involved, as Huck Finn might say, some stretchers. Watching the baroque and expressionist Kane, it’s hard to square it with normal notions of realism, and we may suspect Toland of special pleading. Some of Toland’s purported innovations, such as low-angle shots showing ceilings, had been seen before. Even the signature Toland look, with cramped, deep compositions shot from below, can be found across the history of cinema before Kane. Here is a shot from the 1939 Russian film, The Great Citizen, Part 2 by Friedrich Ermler.

More seriously, some of Toland’s accounts of Kane swerve close to deception. For decades people presupposed that dazzling shots like these were made with wide-angle lenses.

Yet the deep focus in the first image was accomplished by means of a back-projected film showing the boy Kane in the window, while the second image is a multiple exposure. The glass and medicine bottle were shot separately against a black background, then the film was wound back and the action in the middle ground and background were shot. (And even the middle-ground material, Susan in bed, is notably out of focus.) I suspect that the flashy deep-focus illustration in Life, shot with a still camera, is a multiple exposure too. In any event, much of the depth of field on display in Kane couldn’t have been achieved by straight photography. (13)

RKO’s special-effects department had years of experience with back projection and optical printing, notably in the handling of the leopard in Bringing Up Baby, so many of Kane‘s boldest depth shots were assigned to them. But here is all that Toland has to say on the subject:

RKO special-effects expert Vernon Walker, ASC, and his staff handled their part of the production—a by no means inconsiderable assignment—with ability and fine understanding. (14)

Kane’s reliance on rephotography deals a blow to Bazin’s commitment to film as a medium committed to recording an event in front the camera. Instead, the film becomes an ancestor of the sort of extreme artificiality we now associate with computer-generated imagery.

Despite these difficulties, Toland’s ideas sensitized filmmakers and critics to deep space as an expressive cinematic device. Modified forms of the deep-focus style became a major creative tradition in black-and-white cinema, lasting well into the 1960s. Bazin’s analysis certainly developed Toland’s ideas in original directions, and he creatively assimilated what Toland and his directors said into an illuminating general account of the history of film style. None of these creators and critics were probably aware of the remarkable depth apparent in pre-1920 cinema, or in Japanese and Soviet film of the 1930s. Their claims taught us to notice depth, even though we could then go on to discover examples that undercut Toland’s claims to originality.

Some little things to grasp at

I assume that Toland and his directors were sincerely trying to experiment, however much they may have packaged their efforts to appeal to viewers’ and critics’ tastes. But sometimes artists aren’t so sincere. By the 1950s, we have directors who started out as film critics, and they realized that they could guide the agenda. Here is Claude Chabrol:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics over their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, no knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want. (15)

Chabrol is unusually cynical, but surely some filmmakers are strategic in this way. I’d guess that a good number of independent directors pick up on currents in the culture and more or less self-consciously link those to their film.

Today, in press junkets directors can feed the same talking points to reporters over and over again. An example I discuss in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema is the way that Chaos theory has been invoked to give weight to films centering on networks and fortuitous connections. As I read interview after interview, I thought I’d scream if I encountered one more reference to a butterfly flapping its wings.

More recently, Paul Greengrass gave critics some help when he suggested that the jumpy cutting and spasmodic handheld camera of The Bourne Ultimatum suggested the protagonist’s subjective point of view–presumably, Jason’s psychological disorientation and frantic scanning of his surroundings. I expressed skepticism about this on an earlier blog entry, Anne Thompson replied on her blog, and I returned to the subject again. Any director’s statement of purpose is interesting in itself, but it should be assessed in relation to the evidence we detect onscreen.

Another recent instance: the new Taschen book on Michael Mann. The luscious pictures, mainly from Mann’s archive, are the volume’s raison d’etre, but the filmmaker seems to have placed unusual demands on the text. F. X. Feeney writes:

An earlier version of this book completed by another writer attempted (in a spirit of sincere praise) to treat Mann’s films as reactions against film traditions, as subversions of genre. This fetched a rebuke from Mann: “It’s irrelevant and neither accurate nor authentic to compare my films to other films because they don’t proceed from genre conventions and then deviate from those conventions. They proceed from life. For better or worse, what I’ve seen and heard and learned on my own is the origin of this material. Maybe the film medium by nature spawns conventions, because we all built on what’s gone before, but the content and themes of my films are not facile and derivative. They are drawn from life experience.” (16)

We have to wonder if Mann’s objection played a role in eliminating the earlier writer’s version. If that happened, it’s an unusually strong instance of a director’s holding sway over critical commentary. (17)

In the text we have, Feeney provides a chronological account of Mann’s career: plot synopses, thematic commentary, production background. There’s no discussion of broader historical trends, such as the migration of TV directors into film, the creative options available in 1980s-1990s Hollywood, the development of self-conscious pictorialism in modern film, the possibility of genre films becoming art-films or prestige pictures, or the changes in media culture or American society. All of these lines of inquiry would require comparing Mann with other filmmakers. It remains for other writers, perhaps without the director’s cooperation, to put Mann’s achievement into such contexts.

It’s always vital to listen to filmmakers, but we shouldn’t limit our analysis to what they highlight. We can detect things that they didn’t deliberately put into their films, and we can sometimes find traces of things they don’t know they know. For example, virtually no director has explained in detail his or her preferred mechanics for staging a scene, indicating choices about blocking, entrances and exits, actors’ business, and the like. Such craft skills are presumably so intuitive that they aren’t easy to spell out. Often we must reconstruct the director’s intuitive purposes from the regularities of what we find onscreen. (For examples, see this site here, here, and here.) And it doesn’t hurt, especially in this age of hype, to be a little skeptical and pursue what we think is interesting, whether or not a director has flagged it as worth noticing.

(1) Macdonald, “Gertrud,” Esquire (December 1965), 86.

(2) Quoted in Orson Welles and Peter Bogdanovich, ed. Jonathan Rosenbaum, This is Orson Welles (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 21).

(3) Such would seem to be the case of the close-up, which of course is found very early in film history. But Griffith’s idea of a close-up may not correspond to ours. More on this in a later blog, perhaps.

(4) I give an overview of this rich body of research in Chapter 5 of On the History of Film Style. See also various entries in the Encyclopedia of Early Cinema, ed. Richard Abel (New York: Routledge, 2005).

(5) The most detailed argument for this view I know is Paisley Livingston’s book Art and Intention: A Philosophical Study.

(6) “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work: Major Essays and Reviews from the Forties and Fifties, ed. Bert Cardullo (New York: Routledge, 1997), 8.

(7) Orson Welles: A Critical View, trans. Jonathan Rosenbaum (New York: Harper and Row, 1978) 80).

(8) Toland, “Realism for Citizen Kane,” American Cinematographer 22, 2 (February 1941), 54, 80.

(9) See the discussion in Bordwell, Janet Staiger, and Kristin Thompson, The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1985), 345-349.

(10) Toland, “How I Broke the Rules in Citizen Kane,” Popular Photography (June 1941), 55, 90-91.

(11) “Orson Welles: Once a Child Prodigy, He Has Never Quite Grown Up,” Life (May 26, 1941), 110-111.

(12) Wyler, “No Magic Wand,” The Screen Writer (February 1947), 10.

(13) Peter Bogdanovich was to my knowledge the first person to publish some of this information; see “The Kane Mutiny,” Esquire 77, 4 (October 1972), 99-105, 180-90.

(14) Toland, “Realism,” 80.

(15) “Chabrol Talks to Rui Noguera and Nicoletta Zalaffi,” Sight and Sound 40, 1 (Winter 1970-1971), 6.

(16) F. X. Feeney, Michael Mann (Cologne: Taschen, 2006), 21.

(17) Mann’s reasoning puzzles me. He insists that his films can’t be compared to others along any dimensions, especially thematic ones. Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his. Moreover, what about comparisons on grounds of technique, surely one of the most striking and admired features of Mann’s work? For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).

Ad in Wid’s Year Book 1918.

PS: 15 October: I’ve received a clarification from Paul Duncan, editor of F. X. Feeney’s Michael Mann book for Taschen. He expresses general agreement with my suggestions about how directors shape the uptake of their work, but he explains that the Mann book isn’t an instance of it. Here are the comments bearing on my blog entry.

In reply to my suggestion of other avenues to explore about Mann’s career:

In fairness to F.X. Feeney, he only had 25,000 words to cover Mann’s career, and all the subjects you write about are really outside the scope of the book. It sounds as though these are subjects that you would like to explore, and I can’t wait to read them in a future book or blog.

As for whether Mann exercised some control over the book’s final form, which I float as one possible explanation for its compass:

First, you speculate whether Mann caused the first version of the book to be scrapped, i.e. He exerted editorial control/censorship over the book. This is not the case, and if it was, do you think that he would have allowed F.X. to write that in the published version of the book?

In Note 17 appended to Feeney’s quote, you write: “Yet in saying that his films are lifelike, he suggests that other films aren’t as realistic as his.” If you had continued Mann’s quote, you would have reported the following: “I don’t look at the excellent French director Jean-Pierre Melville to decide how to tell the story in Thief. I meet thieves. And I guarantee you the reason Melville’s Le Samourai 1967) has authenticity, the reason Raoul Walsh’s White Heat (1949) has authenticity, is because those film-makers knew thieves, too.” I do not see any evidence here that Mann suggests that his films are more lifelike than other directors’. Only that his films stem from life like other films stem from life.

Also, in Note 17, you write: “For reasons that are obscure, the director discourages any critical consideration of style; Feeney tells us that Mann hates the very word (p. 20).” The reason Mann hates the word “style”—and I apologize for not making this clear in the book—is because after producing the Miami Vice TV show, he was forever referred to as a stylist, and the “style” of the show was all anybody ever talked about. The implication was that Mann is a director of style without substance. Subsequently, Mann has been very wary of the word, and discussion of it, because it puts undue weight on one aspect of his work.

Finally, I would like to explain a little of the working method with Mann on the book. The book was researched and written during rehearsal, filming and editing of Collateral. F.X. wrote the text and was given full access to everything that Mann had said in interviews. Mann then read and annotated the text, and this was discussed face-to-face with F.X. Most of these annotations were of a factual nature, correcting dates, being precise about the sequence of events, and to correct misinterpretations of his comments in previous interviews. However, they would also bring up new comments from Mann about his work. F.X. then rewrote some texts to include Mann’s comments, and then F.X. wrote his replies. In this way, the book became more of a dialogue between Mann and F.X. and is stronger for it I feel. So, in this case, the filmmaker did not get the last word.

I thank Paul for his clarifications, which should be of interest to all the book’s readers. On only two matters do we disagree.

First, Feeney’s book achieves what it set out to achieve, and it deserves credit for giving us valuable information about Mann in a clear, pungent style. And no one expects a Taschen book to be an in-depth monograph covering all aspects of a director’s career. But I still think that length limits don’t prevent an author from raising the contextual issues I mention. Many articles manage to address matters that go beyond the sort of career survey that Feeney provides, so there are ways to sketch such issues in an abbreviated way. I inferred, erroneously, that the choice not to tackle them could have been related to Mann’s own views on the comparative dimension that such issues tend to rely on.

Secondly, a minor matter: The fact that Mann can invoke Melville and Walsh on films about thieves suggests that a comparative perspective is valuable; he’s including himself in the company of directors who know their subjects from life, in explicit contrast to those who don’t. I didn’t include the extra sentences because I thought that they simply provided further signs of the contradiction I found in Mann’s own position—that his films can’t be compared to other directors’ works.