Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Propinquities

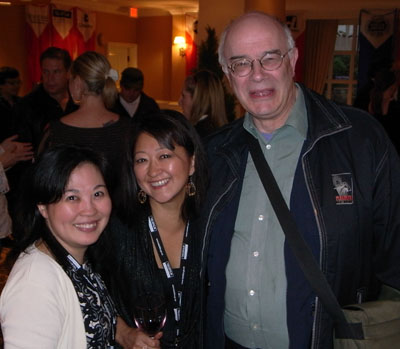

Jinhee Choi, Centre Pompidou, January 2010.

Propinquity: Nearness, closeness, proximity: a. in space: Neighborhood 1460. b. in blood or relationship: Near or close kinship, late ME. c. in nature, belief, etc.: Similarity, affinity 1586. In time: Near approach, nearness 1646. —Oxford Universal Dictionary

DB here:

In any art, tools and tasks matter. From the first edition of Film Art (1979) to the present, our introduction to film aesthetics starts with an overview of film production. How is production organized within the commercial industry, or within a more artisanal mode? What freedom and constraints are afforded within the institutions of filmmaking? How does current technology support or limit what the filmmaker can do? And how do filmmakers explain what they’re doing—not just as personal proclivities but as rhetorical “framings” that lead us to think of their work in a particular way?

Some would call this approach “formalism,” but that label doesn’t capture it. Traditionally formalism refers to studying an artwork intrinsically, as a self-sufficient object. In this sense, our perspective is anti-formalist: We look outside the movie to the proximate conditions that shape its form, style, subjects, and themes.

More literary-minded film scholars have sometimes been impatient with this perspective. Yet in the history of painting and music, it has yielded real advances in our knowledge. It continues to do so in film studies too, as I learned when we came back from Yurrrp to find some books awaiting us. (Kristin has already remarked on the stacks of DVDs that had accumulated.) Among these were books that illustrate the continuing value of situating film artistry in its most immediate context: the creative circumstances, the norms and preferred practices operating within traditions, the rationales that artists offer for their choices. Even better, the books were written by friends, so we have both intellectual and personal propinquity. I have always wanted to use the word propinquity in a piece of writing.

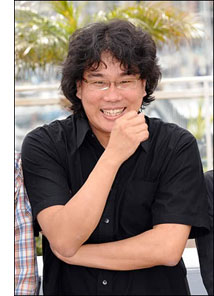

Memories of Murder (Bong Joon-ho).

Jinhee Choi’s The South Korean Film Renaissance: Local Hitmakers, Gobal Provocateurs is a wide-ranging survey of what some have called the “next Hong Kong”–a popular cinema of brash impact and technical polish, on display in JSA, Beat, Dirty Carnival, My Sassy Girl, and the like. But unlike Hong Kong, South Korea has a strong arthouse presence too, typified by Hong Sang-soo’s exercises in parallel narratives and thirtysomething social awkwardness. Between these poles stands what local critics called the “well-made” commercial film, as exemplified by Bong Joon-ho’s Memories of Murder.

Choi, a professor at the University of Kent, mixes analysis of cultural and industrial trends with consideration of crucial genres (notably the “high school film”) and major auteurs. She is the first scholar I know to explain changes in the Korean film industry as emerging from a dynamic among critics, filmmakers, private funding, and government sponsorship. A must, I would say, for anyone interested in current Asian film.

T-Men (Anthony Mann, cinematographer John Alton).

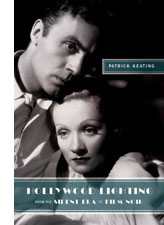

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

The South Korean Film Renaissance is matched by a work of equal subtlety, Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting: From the Silent Era to Film Noir. Keating has an MFA in cinematography from USC, and his Ph. D. work concentrated on classical American cinema. His book captures the craft of the great studio cameramen, following not only what they said they were doing (in interviews and in the trade papers) but also what they actually did. He homes in on the contradictory demands facing artists who, they claimed over and over, had to serve the story. How do you claim artistry if your contribution is unnoticeable? This problem becomes acute with film noir, where the style is expected to come forward to a significant degree.

Keating scrutinizes the films with unprecedented care, tracing not only cameramen’s distinctive styles but showing that originality was always in tension with the conventional lighting demands of various genres and situtations. Many big names are here—John Seitz, Gregg Toland, John Alton—but the book also examines innovations coming from solid craftsmen like Arthur Lundin, who lit Girl Shy and other Harold Lloyd films. You won’t look at a studio movie the same way after you’ve digested Keating’s richly illustrated analyses.

Both Jinhee and Patrick were students here, and I directed the dissertations that eventually became these books. So of course I’m biased. But I think that any outside observer would agree that these monographs show the value of studying how film artistry and the film industry intertwine.

Blue (Krzysztof Kieslowski).

No less sensitive to the interplay of art and business is Patrick McGilligan’s Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s. The collection is as illuminating as earlier installments have been. How could it not be, with career ruminations from Nora Ephron, John Hughes, David Koepp, Barry Levinson, John Sayles, et al.?

I’ve long found Pat’s Backstory volumes a treasury of information about Hollywood’s craft practices. Every conversation yields ideas about structure, style, and working methods. In this volume, for instance, Richard Lagravanese points out that scenes have become very short; with slower pacing in the studio days, scenes had time to breathe. And after claiming over and over that cinematic narration comes down to patterning story information, I was happy to read Tom Stoppard:

The whole art of movies and in plays is in the control of the flow of information to the audience. . . . how much information, when, how fast it comes. Certain things maybe have to be there three times.

In the studio days this last condition was called the Rule of Three: Say it once for the smart people, once for the average people, and once more for Slow Joe in the Back Row. Some things don’t change.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

Pat McGilligan is also a Wisconsin alumnus, so to keep these notes from getting too incestuous, I’ll just mention that I know the distinguished musicologist David Neumeyer chiefly from his writing (though I have to confess I first met him when he visited . . . Madison). Along with coauthors James Buhler and Rob Deemer, David has published an excellent introduction to film sound. Hearing the Movies: Music and Sound in Film History is designed as a textbook, but it’s so well written that every movie lover would find it a pleasure to read.

The examples run from the silent era (including Lady Windermere’s Fan, a favorite of this site) to Shadowlands, and while music is at the center of concern, speech and effects aren’t neglected. There’s a powerful analysis of the noises during one sequence of The Birds, and the authors pick a vivid example from Kieslowski’s Blue (above), in which Julie is shown listening to a man running through her apartment building; we never see the action that triggers her apprehension.

The authors provide a compact history of sound film technology, including many seldom-discussed topics. For instance, 1950s stereophonic film demanded bigger orchestras and more swelling scores, while separation among channels permitted scoring to be heavier, without muffling dialogue. Throughout, Neumayer and his coauthors balance concerns of form and style with business initiatives, such as the growth of the market for soundtrack albums and CDs (a topic first explored by another Wisconsite, Jeff Smith, in his dissertation book). Once more we can arrive at fine-grained explanations of why films look and sound as they do by examining the craft practices and industrial trends that bring movies into being.

Watching back episodes of the American version of The Office recently, I’ve been struck by the premise it takes over from the UK original. This comedy of humors in Cubicle World is supposedly recorded in its entirety by an unseen film crew. I enjoy the clever way in which the show bends documentary techniques to the benefit of traditional fictional storytelling. The slightly rough handheld framings suggest authenticity, and the to-camera interviews permit maximal exposition by giving backstory or developing character or filling in missing action. The premise that an A and a B camera are capturing the doings at the Dunder Mifflin paper company permits classic shot/ reverse-shot cutting and matches on action.

The camera is uncannily prescient, always catching every gag and reaction shot; even private moments, like employees having sex, are glimpsed by these agile filmmakers. Above all, the camera coverage is more comprehensive than we can usually find in fly-on-the-wall filming. For instance, Dwight is preparing Michael for childbirth by mimicking a pregnant woman and Andy, behind him, tries to compete. Here are four successive shots, each one pretty funny.

Somehow the cameramen manage to supply a smooth cut-in to Andy, and that’s followed by a reaction shot, from a fresh angle, showing Jim watching. The range of viewpoints, implausible in a real filming situations, is often smoothed over by sound that overlaps the cuts, as in both documentary and fictional moviemaking. (See our essay on High School here to see how a genuine documentary uses these techniques.)

Of course I’m not faulting the makers of The Office for not rigidly imitating documentary conditions. Any such blend of fictional and nonfictional techniques will involve judgments about how far to go, as I indicate in an earlier post on Cloverfield. It’s just to acknowledge that TV visuals have their own conventions, and these can be creatively shaped for particular effects. We ought to expect that those conventions would encourage close analysis as easily as film traditions do. Jeremy Butler’s new book Television Style offers the best case I know for the claim that there is a distinct, and valuable, aesthetic of television.

Following his own study Television: Critical Methods and Applications (third edition, 2007) and paying homage to John Caldwell’s pioneering Televisuality, Butler gets down to the details of how various TV genres use sound and image. Butler’s conception of genres is admirably broad, considering dramas, sitcoms, soap operas, and commercials, each with its own range of audiovisual conventions and production practices. His discussion of types of television lighting complements Keating’s analysis; put these together and you have some real advances in our understanding of key differences and overlaps between film and video.

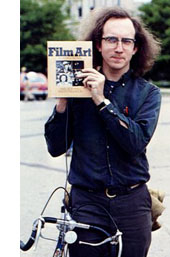

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

Kristin has met Jeremy, but I haven’t yet. In any case, Television Style shows that he’s a kindred spirit who’s made original contributions to this research tradition. Like Jinhee, Patrick, Pat, and David, he demonstrates that we can better grasp how media work if we study, patiently and in detail, the creative options open to film artists at specific points in history. He began thinking about these matters in 1979, as the photo attests.

None of this is to say that artistic norms or industrial processes are cut off from the wider culture. Rather, as becomes very clear in all of these books, cultural developments are often filtered through just those norms and institutions.

For example, everybody knows that in classical studio cinema, women were usually lit differently from men. But Keating notices that often women’s lighting varies across a movie, depending on story situations. He goes on to make a subtler point: there was a greater range in lighting men’s faces. Men could be lit in more varied ways according to the changing mood of the action, while lighting on women was a compromise between two craft norms: let the lighting suit the story’s mood, and endow women with a glamorous look. The fluctuations in the imagery stem from adjusting cultural stereotypes to the demands of Hollywood’s stylistic conventions.

Careful studies like these, alert to fine-grained qualities in the films and the conditions that create them, can advance our understanding of how movies work. Pursuing these matters takes us beyond both the movie in isolation and generalizations about the broader culture; we’re led to examine the filmmaker’s tasks and tools.

Resurrection of the Little Match Girl (Jang Sun-woo, 2002).

Wrapping up the ROW

Paparazzi swarm over the nominees for the Dragons and Tigers Award at the Vancouver International Film Festival.

Kristin here:

Some final films from VIFF

So far Central American countries have produced fewer films than their neighbors to the north and south. So I couldn’t pass up The Wind and the Water, the first fiction feature made in Panama. Made by a collective of fifteen young indigenous people from the Kuna Yala archipelego under the leadership of MIT graduate and first-time director Vero Bollow, it’s a tale of threats to the paradisiacal island by developers who want to build a giant hotel there. It also reflects temptations for young people to desert their traditional lives on the islands for the attractions of nearby Panama City.

The contrast between the islands emerges through a simple tale. Machi, a young man from the islands, goes to the city for schooling and finds it grim and threatening. Rosy, a transplanted native who grew up there, aspires to be a model.

She returns to the islands for her grandfather’s funeral. Confronted with crude latrines and fish-head stews, she is initially miserable but gradually falls under the spell of the area’s beauty. Meanwhile her father works for the group planning to move the islands’ population to a new suburb and build their resort.

The plot is based loosely on that population’s vigorous efforts—successful so far—to fend off efforts of outsiders to gain control of the islands. I was reminded while watching it of the many classic documentaries of the 1930s and 1940s, like Song of Ceylon, shot by Americans and Europeans in exotic locales. For decades film scholars deplored the fact that the people who formed the subjects of such films were being portrayed by outsiders. The Wind and the Water, though a fiction film, has a strongly documentary thread running through it, but this time it is the local population making a film about their own situation.

Bollow (right), who initially left MIT to live in Panama and bring digital technology to indigenous people, wrote the script along with the fifteen team members. She attended Vancouver and answered questions, but members of the team will be traveling with the film to other festivals.

Bollow (right), who initially left MIT to live in Panama and bring digital technology to indigenous people, wrote the script along with the fifteen team members. She attended Vancouver and answered questions, but members of the team will be traveling with the film to other festivals.

In some ways, Ozcan Alper’s debut feature, Autumn, is a classic art-house film. Yusuf, a student radical, is released after ten years in prison because he has a fatal lung disease. He returns to his home. He returns to his rural home in the eastern Turkish mountains and settles in with his widowed mother, keeping his illness secret. He tutors a local boy in math and perhaps falls in love with a melancholy prostitute struggling to support her child.

Many of the scenes consist of the hero lying or sitting in the yard, contemplating the surrounding mountains as autumn slowly changes them. David found the lack of dramatic action and the slow pace of the scenes to be overly familiar conventions of art cinema. No doubt the hero’s goals are de-dramatized, as when he promises a bicycle to the student should he succeed in mother or when very late in the film he decides to help the prostitute. There is one central motif that becomes overly emphatic. When Yusuf first notices the prostitute, she is buying a Russian novel; they simultaneously sit alone watching the same broadcast of Uncle Vanya; eventually she tells Yusuf that he’s like a character out of Russian literature. The film’s tone successfully suggests this comparison without our needing to have it made explicit.

To me, the success of the film arises from the director’s integration of the landscape into the story. The prominence of the rugged landscape and the care with which the story is linked to the fall of leaves and the creeping of snow down the mountainsides lifts this above standard art-house fare. In this case, the fading of the year, beautifully brought into a central role by the cinematography, becomes linked more subtly to the hero’s plight.

Kill Daddy Goodnight, an Austrian film by veteran director Michael Glawogger, starts with a promising premise. The protagonist Ratz hates his father, a cold and critical government minister, and creates a videogame, “Kill Daddy Goodnight,” to wreak a fantasy revenge. Summoned by Mimi, a friend with whom he may or may not be in love, he abruptly flies to New York. She wants him to renovate the basement hideaway of her grandfather, a fugitive Nazi war criminal. Initially revolted, over the course of his work he comes to like the old man. Ratz also manages to find a sleazy internet entrepreneur willing to offer “Kill Daddy Goodnight” on his website, where it becomes an immediate success. Interspersed with this plot are scenes of an unidentified man (below) recording testimony against and visiting his childhood friend, who had worked for the Nazis during the war and killed his father.

So far, so good. But the film’s already complex plot is overburdened by strong hints of Ratz’s incestuous desire for his sister, a thread that comes to little. Mimi’s motivations are confusing, and it’s hard to sympathize with any of the characters. Perhaps that was the intention, but my sense was that the two intriguing plotlines, which could have fit neatly together, were diffused by distractions and uncertainties.

I didn’t get to many documentaries, but being a lover of Vivaldi’s vocal music, I had to see Argippo Resurrected. It’s the fascinating tale of how Czech conductor and musicologist Ondrej Macek ingeniously tracked down the lost 1730 opera, which had originally been composed for Prague. He then staged the piece in one of the two perfectly preserved court theaters of the era, the Castle Theatre at Cesky Krumlov, two hours outside of Prague, near the Austrian border.

The other is at Drottningholm, outside Stockholm, where in 1999 David and I had the privilege of seeing The Garden, a new opera about Linnaeus. (It was the first premiere at the theater since it was sealed in the 18th century.) The original candles have prudently been replaced by electric replicas of one candlepower each, flickering realistically. The Cesky Krumlov theater still uses real candles to light both the stage and the musicians’ stands. I guess this says something about fire codes in Eastern Europe. I for one would be happy to risk it in order to have a thoroughly authentic experience, especially if a Vivaldi opera was playing.

It’s a complicated story to fit into 62 minutes. Director Dan Krames took a clever and effective approach, starting backwards. He shows the theater first, with its wooden framework, sets, and stage machinery. He then goes on to introduce some of the musicians and singers, in the process explaining the concept of authentic performance style to those who may not be familiar with it. We also get to see some short excerpts from rehearsals, so that we come to know the opera a little. Only then does Krames proceed to the tale of Macek’s search for the original manuscript and his laborious piecing-together of the individual arias. Macek makes an engaging subject, though he is so self-deprecating about his discovery that the film has to include another musicologist to explain just how extraordinary the accomplishment was.

Finally Macek takes us on a tour of Venice, showing the few surviving places associated with Vivaldi, whose life is little documented. Along the way, there are further excerpts from rehearsal for the production shown, featuring a collection of excellent singers. Krames told me that Argippo Resurrected should be released on DVD in about a year. In the meantime, a live recording of Macek’s production is available as a 2-CD set.

Some final photos

Film festivals aren’t just for watching movies, of course. They’re for seeing old friends, meeting new ones, and sharing meals—including the festival’s wonderful hand-made waffles—to talk about what we’ve seen. As usual, David had his camera in hand nearly all the time, as the accompanying images show.

Theresa Ho, Eunhee Cha, and Tony Rayns: Three key players in the Vancouver Festival.

Chris Chong (director of Karaoke) and Liu Jiayin (Oxhide II).

Bob Davis, of American Cinematographer, and Noel Vera, Critic after Dark.

Canadian corner: Lisa Roosen-Runge, Shelly Kraicer, and Peter Rist.

Get your Terimayo, Oroshi, and Okonomi here: Japadog, a Vancouver Institution.

A welcome INFLUENZA

DB here:

Kristin and I are en route to the Vancouver International Film Festival, after a few days in Seattle visiting Sanjeev and Megan, nephew and niece-in-law. We were completely awestruck by the vast holdings of Scarecrow Video, where even the Warner Archives special-order DVDs can be rented. We also had a good long talk over JaK steaks with Jim Emerson, impresario of the superb website Scanners. Not to mention catching a screening of the lively Walt & El Grupo at the Seattle International Film Festival theatre. As a big fan of Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros, I was thrilled to learn the background story, as well as to watch gorgeous 16mm Kodachrome footage.

Last year’s trip to Vancouver put us on the road for thirteen days, encountering movie-related stuff (and Obama) in surprising places. This time we took the plane—faster but less relaxing. To get a better look at the landscape, we’ll be taking a train up to Vancouver.

One of the films I’m most looking forward to at Vancouver is Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, brought to this year’s event by Tony Rayns. Alas, Bong himself will not be joining us. I enjoyed meeting him at my first Vancouver visit in 2006, when this blog was in swaddling clothes. He’s completely frank and unpretentious.

One of the films I’m most looking forward to at Vancouver is Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, brought to this year’s event by Tony Rayns. Alas, Bong himself will not be joining us. I enjoyed meeting him at my first Vancouver visit in 2006, when this blog was in swaddling clothes. He’s completely frank and unpretentious.

Even before meeting him, I had followed Bong’s career with keen interest. I think he’s one of the best Korean directors, though he probably doesn’t get as much attention as some others. Like the Japanese Kore-eda Hirokazu, Bong is the sort of quiet genre-hopper who’s hard to pin down. His first feature, Barking Dogs Never Bite, is a charming romantic comedy that also offers a portrait of neighborhood life. The mordant Memories of Murder (2003) quietly bends the conventions of the city-cop-in-a-village movie, mixing comedy into a serial-killer tale. Bong’s biggest commercial success came with The Host (2006), a monster movie in the grand tradition that manages to be at once scary, funny, and socially critical. Seeing it again this summer, I was struck by its compact elegance. Bong makes complex narrative and stylistic twists look easy.

Bong has also made some acute short films; he seems to understand that they require the snappy impact of a well-wrought short story. Probably his best-known short is the “Shaking Tokyo” segment of the omnibus movie Tokyo (2008). It focuses on a hikikomori, a young man who has withdrawn from social contact and lives wholly through the TV monitor and the computer screen. Bong’s hero tidily stacks empty pizza boxes along his walls like installation art. Only an encounter with a delivery woman makes him question his robotic seclusion. The ending, which lures our hero outside, provides a Twilight-Zoneish twist.

More single-minded, though, is a short I’ve just seen, the little-known Influenza (2004). There are several movies based on surveillance-camera footage; one of the most lyrical, Optical Vacuum, I reviewed here. Bong went instead for narrative. He staged a story in locales covered by surveillance cameras, and then retrieved the footage from the hours of material. Cut together, the shots follow Mr. Cho, a failed salesman who turns to petty theft and violent crime.

We discover Mr. Cho in men’s rooms, car parks, and ATM stations. The scenes, each shot in a single take, run through various spycam techniques: fixed high angle, black and white imagery, stuttering motion, mechanical scanning of the scene (sometimes leaving the main action behind). We see wide-angles, telephoto shots, barely legible long-shots, and split-screen imagery picking out opposite points of view.

Everything we see is staged, I think. Unrehearsed events seldom look this cogent and poised. Yet sometimes, especially during the climactic crowd scene, some of the action seems to have been left to luck.

Short but not sweet—mostly sour—Influenza shows what an ingenious filmmaker can do by setting himself a single, precise problem. Crossing the border between commercial fiction and avant-garde experimentation, the film deserves wider circulation.

As for Mother, Derek Elley’s Variety review promises the trademark Bong blend of gentle comedy and unsettling drama. And Vancouverites have an extra bit of luck: A program of shorts by Bong and his colleagues from the Korean Academy of Film Arts graces the festival this year. Bong’s next planned project, about the wretched survivors of a new Ice Age, shows him to be as unpredictable and unclassifiable as ever.

Thanks to Bong Joon-ho for his help in preparing this entry. The trailer for Walt & El Grupo is here. And there’s a poignant story of the founding and near-demise of Scarecrow Video here.

The Host.

Forgotten but not gone: more archival gems on DVD

Kristin here-

We don’t make a practice of regularly reviewing DVDs here, but when a special release comes along that makes historically important, hard-to-see films available, we like to point it out. David spotlighted the new Criterion set of Shimizu Hiroshi films, and this week it’s Lotte Reiniger and Belgian experimental silents.

The lady with the flying scissors

Up until recently, the name Lotte Reiniger meant little to most people. Some were aware that she, rather than Walt Disney, had made the first animated feature film, The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926). Some had been lucky enough to see a few of her shorts, created with a delicate silhouette technique using hinged, cut-out puppets. She had pioneered the approach in the late 1910s and continued to use it in much the same way up to her last films in the 1960s and 1970s.

Now, however, in another of the marvelous revelations that DVDs have made possible, we are in the process of having virtually all of Reiniger’s surviving work become available over a short stretch of time.

Early this year the British Film Institute released a two-disc set, “Lotte Reiniger: The Fairy Tale Films.” It concentrates on a series of thirteen films Reiniger and her husband Carl Koch made for television during an intensely productive period in 1954-55.

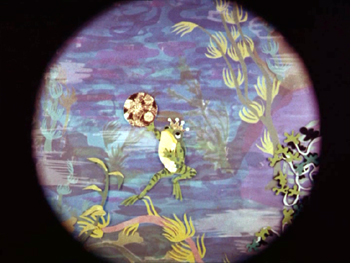

Two of these, Aladdin and the Magic Lamp and The Magic Horse, recycle footage from The Adventures of Prince Achmed, the elaborateness and delicacy of which stand out. Yet the rest of the series, though clearly made on a lower budget and remarkably quickly, are consistently excellent, with considerable detail of gesture and a great deal of wit (as in Thumbelina, right).

The rest of the program includes the 1922 Cinderella (left) which is Reiniger at her prime-though the detail of  one of the stepsisters slicing off part of her foot to make it fit in the tiny slipper may be a bit grim for some children. The Death-Feigning Chinaman (1928) is a fascinating item, a sequence cut from Prince Achmed and released as a free-standing tale. Reiniger made The Golden Goose (1944) in Berlin late in the war, as she cared for her ailing mother. It was not edited into a silent version until 1963, with a soundtrack being added for TV in 1988. It’s a real treasure that belies the grim circumstances of its making.

one of the stepsisters slicing off part of her foot to make it fit in the tiny slipper may be a bit grim for some children. The Death-Feigning Chinaman (1928) is a fascinating item, a sequence cut from Prince Achmed and released as a free-standing tale. Reiniger made The Golden Goose (1944) in Berlin late in the war, as she cared for her ailing mother. It was not edited into a silent version until 1963, with a soundtrack being added for TV in 1988. It’s a real treasure that belies the grim circumstances of its making.

The material following chronologically after the thirteen television episodes consists of three films. One, The Little Chimney Sweep, is the only disappointment in the program. It’s a revised, abridged version of a film from 1934, and the voiceover narration and truncated action downplay the subtle touches and charm that characterize all the other films. Fortunately the original survives and will be presented in the DVD program of the musical films.

The other two films are in color. I had never seen a color Reiniger film, but both are lovely, like old-fashioned children’s book-illustrations come to life. Jack and the Beanstalk (see image above) is the more polished of the two. Here black silhouette figures move amid brightly colored, stylized landscapes. It doesn’t sound like it should work, but it does. The Frog Prince is more what one would expect, with hinged colored puppets replacing the dark silhouettes. The result is highly engaging, though the lack of expression in the characters, which works so well for the dark silhouettes, might become too apparent in a film lasting more than a few minutes.

Wonderful though it is to have this big dose of Reiniger made available, I wish that the BFI had organized its presentation more helpfully. For a start, there’s no indication that this set is part of an ongoing series that will eventually make most of the filmmaker’s work available. No reference to that fact that the BFI already put out The Adventures of Prince Achmed in 2001, accompanied by an hour-long documentary, Lotte Reiniger: Homage to the Inventor of the Silhouette Film, directed by Katja Raganelli (which isn’t is also on the American disc released by Milestone). No announcement that a set of Reiniger’s music-based animated shorts is due out later this year or that the second set of GPO advertising shorts also due soon will include some Reiniger works (The Tocher and The H.P.O.), though brief references to that future release are buried in a couple of the program notes. (The two Reiniger films are already available on a British DVD called The GPO Story.) Only diligent trawling about the internet reveals such things. There’s a good summary of the situation in the DVD Times review of the fairy-tales set.

The program notes are fairly informative if you want plot synopses, but they provide virtually no historical context. There’s no general introduction to the program or the overall series, just a brief biographical note on Reiniger and notes on the individual films. I would have appreciated some information on the 1954 television series for which many of the films in the set were made.

Speaking of plot synopses, the notes for The Death-Feigning Chinaman miss a key narrative point. The title character, Ping Pong, gets drunk and starts eating a cooked fish that a young couple give him. The description continues, “Ping Pong eats a little of the fish, then tramples it in a drunken rage and falls down in a stupor.” This is a key moment, since his apparent death launches a snowballing accumulation of confusion, confession, and near execution. What actually happens is that Ping Pong chokes on a bone while eating the fish, and it paralyzes him. At the climax, an insect lands on his nose, he sneezes, the bone flies out of his mouth, and he emerges from his “death.”

Another instance of disorganization comes with a charming little color film, The Frog Prince, from 1961. It  was originally creates as an interlude in a stage pantomime, and on the disc it is presented silent. The program note comments, “No evidence of a soundtrack survives, and indeed sound seems unbefitting for a pantomime interlude. Although surprisingly, the aperture format of this mute positive print is 1:1.375 with an unused soundtrack area.” Yet the short documentary included in the set, The Art of Lotte Reiniger, includes The Frog Prince in its entirety, accompanied by lively and quite appropriate orchestral music. Given that Reiniger’s own production company made this film and she participated in its creation, it seems highly probable that the music used in the documentary was either the intended accompaniment for the film or at least considered suitable for it. A case of the right hand not knowing what the left is doing when this package was being put together, I guess.

was originally creates as an interlude in a stage pantomime, and on the disc it is presented silent. The program note comments, “No evidence of a soundtrack survives, and indeed sound seems unbefitting for a pantomime interlude. Although surprisingly, the aperture format of this mute positive print is 1:1.375 with an unused soundtrack area.” Yet the short documentary included in the set, The Art of Lotte Reiniger, includes The Frog Prince in its entirety, accompanied by lively and quite appropriate orchestral music. Given that Reiniger’s own production company made this film and she participated in its creation, it seems highly probable that the music used in the documentary was either the intended accompaniment for the film or at least considered suitable for it. A case of the right hand not knowing what the left is doing when this package was being put together, I guess.

The Art of Lotte Reiniger is a fascinating little film, despite the rocky sound quality of the surviving print. The filmmaker shows off her storyboards and puppets, but the really amazing thing is watching how quickly she cuts the silhouettes, freehand, out of black paper.

For those who read German and want as full a dose of Reiniger as possible, an 8-disc box is already available, including Prince Achmed, the fairy-tale and music shorts, and a two-disc set called “Dr. Dolittle & Archivschatze” (Dr. Dolittle and archive treasures).

Animation historian William Moritz provides a biographical note and filmography for Reiniger here. It or something like it would have been a helpful introduction to the DVD booklet.

“This is not a pipe,” the movie

As of February of this year, I have been visiting the Cinémathèque royale de Belgique/the Koninklijk Film Archief, or, unofficially, the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, for thirty years now. (David made his first visit there in 1982.) It has been a tremendous resource for us, and its staff, especially current archive director Gabrielle Claes, have invariably been generous and welcoming.

Being a government-supported institution in a bilingual country, the Archive renders all texts in French and Flemish, from the monthly screening schedules to the subtitles that sprawl across the bottoms of frames. Now, as part of a renovation of the screening venue and museum space, the Royal Film Archive has abandoned all that verbiage and officially renamed itself the Cinematek. That’s not a real word in any language, but it conveys more or less the same thing in French, Flemish, and English. I suspect that the epic subtitles will remain. For full details of the new facility and programming, go here.

Before the name change, the archive had started a DVD series awkwardly entitled “filmarchief dvd’s – les dvd de la cinémathèque.” These are collections of archival films mostly relating to Belgium, and a lot of them are documentaries. The series includes an excellent new two-disc set, “Avant-Garde 1927-1937.” (The archive also publishes modern films, mostly in Flemish.) It’s in fact a trilingual release, with the subtitle “Surréalisme et expérimentation dans la cinéma belge/Surealisme en experiment in de Belgische cinema/Surrealism and experiment in Belgian cinema.” The text of the detailed accompanying booklet is in all three languages, and the discs also offer options for subtitles in any of the three. The producers have taken great care with the music, commissioning Belgian musicians to compose and perform modernist chamber-orchestra scores. These vary considerably, effectively matching the tone and style of each film. The design of the packaging is practical and sturdy: it’s a small hard-cover book with the pages containing the text and the discs fastened onto the endpages.

Belgian silent experimental cinema might sound a bit obscure, but recall that the country had a pretty prominent role in the Surrealist movement, mostly famously with painter René Magritte. Categorizing all the films on these discs as Surrealist is a bit of a stretch. Some fit that designation, but others are more like city symphonies and political documentaries, and a couple defy definition. But if the label attracts more attention, all the better. Henri Storck and Charles Dekeukeleire, the filmmakers whose works dominate the set, are major filmmakers, and the two shorts that fill out the discs are of historical interest–and genuinely Surrealist.

Storck has long been better remembered than Dekeukeleire. He helped form the national film archive in the late 1930s, and he went from experimental cinema in the 1920s to become a prominent documentarist for the rest of his career. His collaboration with Joris Ivens, Misère au Borinage (1933), is a classic in the genre.

Disc One

Storck dominates the first disc with four titles. his Images d’Ostende (1929) is a quiet study of the seaside resort town where the filmmaker was born. It’s a lovely debut, revealing his eye for composition and  feeling for nature. There’s nothing Surrealist about it. It’s closer to some of the more familiar lyrical studies of the era, like Ivens’ Rain. The accompanying music is modernist with a 1920s feel; a soprano voice weaves subtly through the instrumentation.

feeling for nature. There’s nothing Surrealist about it. It’s closer to some of the more familiar lyrical studies of the era, like Ivens’ Rain. The accompanying music is modernist with a 1920s feel; a soprano voice weaves subtly through the instrumentation.

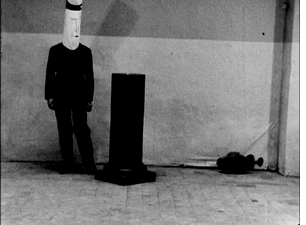

The second film, Pour vos beaux yeux (1929), is a fiction film and definitely Surrealist. The story is minimal. A man finds a false eye lying on the ground. He visits a prosthetics shop, makes plans involving maps, and contemplates the eye on a pedestal while wearing a peculiar cylindrical mask (left). Eventually he wraps the eye in a box and attempts to mail the package.

The program notes claim that Storck could not have seen Un chien andalou when he made Pour vos beaux  yeux. That’s difficult to believe, given that the film seems almost to be an elaborate riff on that film’s eyeball-slitting shot. There are definite references to Ballet mécanique, and the seashells that line the desk where the protagonist wraps the package recall Germaine Dullac’s La coquille et le clergyman.

yeux. That’s difficult to believe, given that the film seems almost to be an elaborate riff on that film’s eyeball-slitting shot. There are definite references to Ballet mécanique, and the seashells that line the desk where the protagonist wraps the package recall Germaine Dullac’s La coquille et le clergyman.

Storck had obviously seen Eisenstein films as well, including October. Histoire du soldat inconnu (1932) is made up of footage from 1928, when an anti-war treaty had been signed. The filmmaker uses intellectual montage to make the point that militarism and the institutions that support it are clearly going to make mincemeat of the treaty’s ideals. The approach is pretty simple, juxtaposing marching soldiers with religious processions. At that point in film history, it was probably still a pretty novel idea that one could cut from a pompous politician speaking to a small dog yapping. By now it looks pretty heavy-handed.

Indeed, the next film in the program, Sur les bords de la caméra (also 1932, also incorporating found footage from 1928) uses the same technique with more restraint. It reminded me a little of Bruce Conner’s A Movie, where odd juxtapositions gradually come to seem more sinister and finally disastrous. Scenes of groups exercising, religious processions, shots in traffic and in prison, all add up to a suggestion that a whole population is voluntarily doing regimented things controlled by the police and other authorities.

On my first visit to the Royal Film Archive back in 1979, one of the titles on my to-see list was Impatience, an experimental film by Charles Dekeukeleire. I had seen a reference to it in the British-Swiss journal of film art, Close-Up. Jacques Ledoux, director of the archive, was delighted that anyone should want to see a film by this nearly forgotten director. He urged me to see Deukeukeleire’s other experimental films, all made in the 1920s and early 1930s before he, too, moved into documentary work.

I saw Combate de boxe (1927), made when Dekeukeleire was only 22. Combining negative and positive footage, hand-held camera, rapid montage, masks–pretty much all the devices of the European avant-garde of the day–he strove to give the subjective impressions of the two combatants in the ring. That’s the first of four Dekeukeleire films in this set. It’s an impressive film by a very young, talented man–but not one that suggests the highly original artist that he would soon become.

The last film on disc one skips forward to 1932, when Dekeukeleire made Visions de Lourdes. Beginning with conventionally beautiful mountain vistas, the film slowly moves toward the area around the sacred grotto and finally to shots within the grotto itself. There are shots of shop-windows full of Lourdes souvenirs (including candy made with holy water from the shrine), but these come in fairly late, avoiding a blatant focus on the commercialization of the site and the notion that those hoping to be healed of illness and deformity are being exploited.

Clearly Dekeukeleire has a more original sense of composition than does Storck. There is a motif of old women selling candles that the filmmaker turns into a series of shots that look like something out of Eisenstein’s Mexican footage–which of course Dekeukeleire could not have seen. (See the image at the bottom, which has enough gap framing to impress even David.) The film is critical of the church, but subtly so–and perhaps mainly because we’ve been cued to take it that way, especially in this case by the dissonant music. I wonder if, in a different context and with a cheerier soundtrack, some of the devout might actually take it as a serious tribute to the healing powers of the saint. They would be mistaken, I think, but the film is understated enough that I think it’s possible.

Disc Two

Dekeukeleire’s two masterpieces, however, were made between these Combat de boxe and Visions de Lourdes. Impatience (1928) is an abstract film that hints maddeningly at a possible narrative situation that never develops. Instead, shots of  four “personnages,” a woman, a motorcycle, a mountainous landscape, and three abstract blocks are edited together. None of these elements is every seen in a shot with any of the others. Rapid montage, vertiginous views against blank backgrounds, upside-down framings, and ruthless, unvarying stretches of repetition make this one of the most challenging, opaque films of its era.

four “personnages,” a woman, a motorcycle, a mountainous landscape, and three abstract blocks are edited together. None of these elements is every seen in a shot with any of the others. Rapid montage, vertiginous views against blank backgrounds, upside-down framings, and ruthless, unvarying stretches of repetition make this one of the most challenging, opaque films of its era.

Perhaps in the wake of post-World War II experimental cinema, where spectator frustration and the denial of conventional beauty and entertainment are often part of a film’s intent (Michael Snow’s Wavelength comes to mind), we are better equipped to understand a film like Impatience, which in its day baffled most reviewers and audiences. Indeed, now Impatience is widely considered to be the best of Dekeukeleire’s avant-garde films.

I think that’s partly because one can at least classify it as an abstract film. For me, his next and longest experimental work, Histoire de detéctive (1929), is even more daring. It purports to present a story in which a  detective named T is hired by Mrs. Jonathan to investigate why her husband has been behaving in a peculiar fashion. T uses a movie camera to record Mr. Jonathan’s actions, and what we see purports to be the results. But, as a title points out, sometimes conditions made T’s filming impossible. What we see are scraps of scenes rather than coherent, continuous footage. The narrative deliberately depends extensively on lengthy intertitles and inserted documents, while the images suggest little in the way of narrative–as when repeated shots show Jonathan lingering on a bridge in the tourist town of Bruges while the intertitles list all the famous sights that he didn’t see (left).

detective named T is hired by Mrs. Jonathan to investigate why her husband has been behaving in a peculiar fashion. T uses a movie camera to record Mr. Jonathan’s actions, and what we see purports to be the results. But, as a title points out, sometimes conditions made T’s filming impossible. What we see are scraps of scenes rather than coherent, continuous footage. The narrative deliberately depends extensively on lengthy intertitles and inserted documents, while the images suggest little in the way of narrative–as when repeated shots show Jonathan lingering on a bridge in the tourist town of Bruges while the intertitles list all the famous sights that he didn’t see (left).

Histoire de détective flew in the face of all contemporary assumptions about the “cinematic” lying in images with as few intertitles as possible. It was audacious in ways that annoyed critics, and its considerable humor went right past most of them. Dekeukeleire apparently realized that his distinctive brand of experimentation had virtually no audience, and he turned to documentaries.

For some reason this program does not include his Witte Vlam (1930), a short Vertovian drama about a protest march broken up by police. It’s not Surrealistic, but no less so than some of the other films included here.

The two final films in the set are by directors who only made one film each. Both refer to Louis Feuillade’s  work, suggesting that his serials, though a decade old and more by the end of the 1920s, retained their hold on the Surrealist imagination.

work, suggesting that his serials, though a decade old and more by the end of the 1920s, retained their hold on the Surrealist imagination.

Henri d’Urself’s La perle (1929), is quite self-consciously a Surrealist work about a young man who keeps trying to buy and deliver a pearl necklace to his beloved, only to give it away to a lovely thief who tries to steal it from his hotel room. The thief is only one of several women lurking in the hotel corridors, all dressed in skin-tight body suits that recalls those worn by Musidora in her immortal role as villainess Irma Vep in Les Vampyrs. In true Surrealist fashion, although the hero enters a jewelry shop in a bustling street of a large city, he exits the building directly into country scene (right).

The last and latest of the films in the set is Ernst Moerman’s Monsieur Fantômas (1937), an intermittently  amusing homage to the super-villain of Feuillade’s 1913 serial. Traveling the globe in search of his true love, Fantômas (left, imitating his famous pose from the film’s posters) apparently commits a murder and is investigated by Juve, Feuillade’s clever but perpetually thwarted opponent. Filming on virtually no budget, Moerman set his action mainly on a beach and in an old cloister, thus allowing him to add some of the anti-religious touches so beloved of the Surrealists.

amusing homage to the super-villain of Feuillade’s 1913 serial. Traveling the globe in search of his true love, Fantômas (left, imitating his famous pose from the film’s posters) apparently commits a murder and is investigated by Juve, Feuillade’s clever but perpetually thwarted opponent. Filming on virtually no budget, Moerman set his action mainly on a beach and in an old cloister, thus allowing him to add some of the anti-religious touches so beloved of the Surrealists.

A bit of six-degrees-of-separation trivia: Fantômas is played by Jean Michel, the future father of French actor-singer Johnny Hallyday, who stars in Vengeance, the Hong Kong film by David’s friend Johnnie To that’s playing at Cannes this year.

The Belgian avant-garde cinema of this era is not a little backwater that merits a quick look only by specialists. Storck’s and particularly Dekeukeleire’s works are as sophisticated and challenging as almost anything that was going on in experimental filmmaking of the era, though the latter’s films were so idiosyncratic that they had no noticeable influence.

Back in 1979, when I learned about Dekeukeleire, I was so impressed that I sought to bring him some attention. I wrote an article, “(Re)Discovering Charles Dekeukeleire.” As the title suggests, Dekeukeleire hadn’t fallen into obscurity but had languished there from the beginning. Unfairly so, as I argued in the article, which was published in the Fall/Winter 1980-81 issue of the Millennium Film Journal. With this new DVD set making his and his colleagues work more accessible, I am inspired to revive my old article, which helps explain, I hope, some of what seems to me so original and daring about his early films, particularly Impatience and Histoire de detétective. The piece was written in the pre-digital age, and scanned .pdfs would probably be scarcely readable. So I plan to retype the thing and post it in the articles section of David’s website as soon as possible. [June 4: Done! Now available here.]

I hope that now devotees of animation and experimental cinema will seek out both these DVD sets. The Belgian one is in the PAL format, but without region coding. The Reiniger is also PAL, region 2 coding.

[May 23: Thanks to Harvey Deneroff for a correction concerning the American DVD of Prince Achmed.]