Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Love isn’t all you need

Pat and Mike.

DB still in HK:

Last week the Hong Kong International Film Festival hosted Gerry Peary’s For the Love of Movies: The Story of American Film Criticism. It’s a lively and thoughtful survey, interspersing interviews with contemporary critics with a chronological account that runs from Frank E. Woods to Harry Knowles. It goes into particular depth on the controversies around Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, but it even spares some kind words for Bosley Crowther.

Some valuable points are made concisely. Peary indicates that the alternative weeklies of the 1970s and 1980s were seedbeds for critics who moved into more mainstream venues like Entertainment Weekly. I also liked the emphasis on fanzines, which too often get forgotten as precedents for internet writing. In all, For the Love of Movies offers a concise, entertaining account of mass-market movie criticism, and I think a lot of universities would want to use it in film and journalism courses.

I should declare a personal connection here. I’ve known Gerry since 1973, when I came to teach at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Like me, he was finishing a dissertation: he was writing a history of the gangster films made before Little Caesar. We spent good lunches together at the Fish Store. Gerry was one of the moving spirits of Madison movie culture—running a film society, writing and editing for the student paper, working with John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tim Onosko, and Tom Flinn on The Velvet Light Trap. I knew I’d come to the right place when somebody would drop by my office to talk about last night’s screening of Underworld or Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

I should declare a personal connection here. I’ve known Gerry since 1973, when I came to teach at the University of Wisconsin—Madison. Like me, he was finishing a dissertation: he was writing a history of the gangster films made before Little Caesar. We spent good lunches together at the Fish Store. Gerry was one of the moving spirits of Madison movie culture—running a film society, writing and editing for the student paper, working with John Davis, Susan Dalton, Tim Onosko, and Tom Flinn on The Velvet Light Trap. I knew I’d come to the right place when somebody would drop by my office to talk about last night’s screening of Underworld or Steamboat ‘Round the Bend.

Like many of our generation, Gerry became a mixture of critic and academic. He taught at several colleges, wrote for The Boston Phoenix, and published books, notably Women and the Cinema: A Critical Anthology (1977) and The Modern American Novel and the Movies (1977). Most recently he’s edited collections of interviews with Tarantino and John Ford. He has moved smoothly into online publishing with a packed and wide-ranging website.

Gerry’s documentary comes along at a parlous time, of course. Most of the footage was taken before the wave of downsizings that lopped reviewers off newspaper staffs, but already tremors were registered in some interviewees’ remarks. Apart from this topical interest, the film set me thinking: Is love of movies enough to make someone a good critic? It’s a necessary condition, surely, but is it sufficient?

Gerry’s film includes the inevitable question: What movie imbued each critic with a passion for cinema? I have to say that I have never found this an interesting question, or at least any more interesting when asked of a professional critic than of an ordinary cinephile. Watching Gerry’s documentary made me think that everybody has such formative experiences, and nearly everybody loves movies. But what sets a critic apart?

Elsewhere, I’ve argued that a piece of critical writing ideally should offer ideas, information, and opinion—served up in decent, preferably absorbing prose. This is a counsel of perfection, but I think the formula ideas + information + opinion + good or great writing isn’t a bad one.

You really can’t write about the arts without having some opinion at the center of your work. Too often, though, a critic’s opinions come down simply to evaluations. Evaluation is important, but it has several facets, as I’ve tried to suggest here. And other sorts of opinions can also drive an argument. You can have an opinion about the film’s place in history, or its contribution to a trend, or its most original moments. Opinions like these allow you to build an argument, drawing on evidence or examples in or around the movie in question. Several of our blog entries on this site are opinion-driven, but not necessarily evaluations of the movies.

Most people think that film criticism is largely a matter of stating evaluations of a film, based either in criteria or personal taste, and putting those evaluations into user-friendly prose. If that’s all a critic does, why not find bloggers who can do the same, and maybe better and surely cheaper than print-based critics? We all judge the movies we see, and the world teems with arresting writers, so with the Internet why do we need professional critics? We all love movies, and many of us want to show our love by writing about them.

In other words, the problem may be that film criticism, in both print and the net, is currently short on information and ideas. Not many writers bother to put films into historical context, to analyze particular sequences, to supply production information that would be relevant to appreciating the movies. Above all, not many have genuine ideas—not statements of judgments, but notions about how movies work, how they achieve artistic value, how they speak to larger concerns. The One Big Idea that most critics have is that movies reflect their times. This, I’ve suggested at painful length, is no idea at all.

Once upon a time, critics were driven by ideas. The earliest critics, like Frank Woods and Rudolf Arnheim, were struggling to define the particular strengths of this new art form. Later writers like André Bazin and the Cahiers crew tried to answer tough idea-based questions. What is distinctive about sound cinema? How can films creatively adapt novels and plays? What are the dominant “rules” of filmmaking ? (And how might they be broken?) What constitutes a cinematic modernism worthy of that in other arts? You could argue that without Bazin and his younger protégés, we literally couldn’t see the artistry in the elegant staging of a film like George Cukor’s Pat and Mike. Manny Farber, celebrated for his bebop writing style, also floated wider ideas about how the Hollywood industry’s demand for a flow of product could yield unpredictable, febrile results.

One of the reasons that Sarris and Kael mattered, as Gerry’s documentary points out, was that they represented alternative ideas of cinema. Sarris wanted to show, in the vein of Cahiers, that film was an expressive medium comparable in richness and scope to the other arts. One way to do that (not the only way) was to show that artists had mastered said medium. Kael, perhaps anticipating trends in Cultural Studies, argued that cinema’s importance lay in being opposed to high art and part of a raucous, occasionally vulgar popular culture. This dispute isn’t only a matter of taste or jockeying for power: It is genuinely about something bigger than the individual movie.

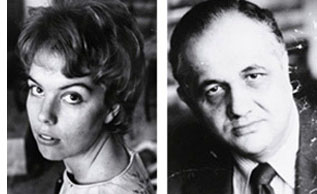

During the Q & A, it emerged that at the same period critics’ ideas had an impact on filmmaking. Sarris’s promotion of the director as prime creator, with a bardic voice and a personal vision, was quickly taken up by Hollywood. Now every film is “a film by….” or “ a … film”: auteur theory shows up in the credits. Similarly, the concept of film noir was constructed by French critics and imported to the US by Paul Schrader. Suddenly, unheralded films like The Big Combo popped up on the radar. Today viewers routinely talk about film noir, and filmmakers produce “neo-noirs.” It seems to me as well that Hollywood became somewhat more sensitive to representation of women after Molly Haskell (here, alongside Sarris) had brought feminist ideas to bear on the American studio tradition, avoiding simple celebration or denunciation. Film criticism had a robust impact on the industry when it trafficked in ideas.

During the Q & A, it emerged that at the same period critics’ ideas had an impact on filmmaking. Sarris’s promotion of the director as prime creator, with a bardic voice and a personal vision, was quickly taken up by Hollywood. Now every film is “a film by….” or “ a … film”: auteur theory shows up in the credits. Similarly, the concept of film noir was constructed by French critics and imported to the US by Paul Schrader. Suddenly, unheralded films like The Big Combo popped up on the radar. Today viewers routinely talk about film noir, and filmmakers produce “neo-noirs.” It seems to me as well that Hollywood became somewhat more sensitive to representation of women after Molly Haskell (here, alongside Sarris) had brought feminist ideas to bear on the American studio tradition, avoiding simple celebration or denunciation. Film criticism had a robust impact on the industry when it trafficked in ideas.

You can argue that these are old examples. What new ideas are forthcoming from mainstream film criticism? In the Q & A Gerry, like the rest of us, couldn’t come up with many. On reflection, I wonder if the rise of academic film studies forced ideas to migrate to the specialized journals and the Routledge monograph. These ideas also had a different ambit—sometimes not particularly focused on cinema, or on aesthetics, or on creative problem-solving.

Of course ideas don’t move on their own. A more concrete way to put this is that bright, conceptually oriented young people who in an earlier era would have become journalistic critics became professors instead. The division of labor, it seems, was to aim Film Studies at an increasingly esoteric elite, and let film reviewers address the masses. It’s an unhappy state of affairs that we still confront: recondite interpretations in the university, snap evaluations in the newspapers. You can also argue that print reviewers, by becoming less idea-driven, paved the way for DIY criticism on the net.

What about information, the other ingredient I mentioned? If we think of film criticism as a part of arts journalism, we have to admit that most of it can’t compare to the educational depth offered by the best criticism of music, dance, or the visual arts. You can learn more from Richard Taruskin on a Rimsky performance or Robert Hughes on a Goya show than you can learn about cinema from almost any critic I can think of. These writers bring a lifetime of study to their work, and they can invoke relevant comparisons, sharp examples, and quick analytical probes that illuminate the work at hand. Even academically trained film reviewers don’t take the occasion to teach.

Most of the print criticism I’ve seen today is remarkably uninformative about the range and depth of the art form, its traditions and capacities. Perhaps editors think that film isn’t worthy of in-depth writing, or perhaps their readers would resist. As if to recall the battles that Woods, Arnheim and others were fighting, cinema is still not taken seriously as an art form by the general public or even, I regret to say, by most academics.

Yet other aspects of information could be relevant. Close analysis offers us information about how the parts work together, how details cohere and motifs get transformed. For an example of how analysis can be brought into a newspaper’s columns, see Manohla Dargis on one scene in Zodiac.

I’d also be inclined to see description—close, detailed, loving or devastating—as providing information. It’s no small thing to capture the sensuous surface of an artwork, as Susan Sontag put it. Good critics seek to evoke the tone or tempo of a film, its atmosphere and center of gravity. We tend to think that this is a matter of literary style, but it’s quite possible that sheer style is overrated. (Yes, I’m thinking of Agee.) Thanks to our old friends adjective and metaphor, even a less-than-great writer can inform us of what a film looks and sounds like.

I’d also be inclined to see description—close, detailed, loving or devastating—as providing information. It’s no small thing to capture the sensuous surface of an artwork, as Susan Sontag put it. Good critics seek to evoke the tone or tempo of a film, its atmosphere and center of gravity. We tend to think that this is a matter of literary style, but it’s quite possible that sheer style is overrated. (Yes, I’m thinking of Agee.) Thanks to our old friends adjective and metaphor, even a less-than-great writer can inform us of what a film looks and sounds like.

In any event, I’m coming to the view that the greatest criticism combines all the elements I’ve mentioned. As so often in life, love isn’t always enough.

Gerry’s documentary doesn’t distinguish between critics and reviewers, but we probably should. Reviewers typically give us opinions and a smattering of information (plot situations, or production background culled from presskits), wrapped up in a writing style that aims for quick consumption. Today anybody with a web connection can be a reviewer.

Exemplary critics try for more: analysis and interpretation, ideas and information, lucidity and nuance. Such critics are as rare now as they have ever been. Far from being threatened by the Internet, however, they have more opportunities to nourish film culture than ever before.

The Big Combo.

PS 4 April (HK time): Thanks to Justin Mory for correcting a name error in the original post!

Showing what can’t be filmed

DB, again:

People tend to think that documentary films are typified by two conditions. First, the events we see are unstaged, or at least unstaged by the filmmaker. If you mount a parade, the way that Coppola staged the Corpus Christi procession in The Godfather Part II, then you aren’t making a documentary. But if you go to a town that is holding such a procession and shoot it, you are making a doc—even though the parade was organized to some extent by others. Fiction films stage their events for the camera, but documentaries, we tend to think, capture spontaneous happenings.

Secondly, in a documentary the camera is seizing those events photographically. The great film theorist André Bazin saw cinema’s defining characteristic as its capacity to record the actual unfolding of events with little human intervention. All the other arts rely on human creation at a basic level: the novelist selects words, the painter chooses colors. But the photographer or filmmaker employs a machine that impassively records what is happening in front of it. “All the arts are based on the presence of man,” Bazin writes; “only photography derives an advantage from his absence.” This isn’t to say that cinema can’t be artful, only that it offers a different sort of creativity than we find in the traditional arts. The filmmaker works not with pure imaginings but obstinate chunks of actual time and space.

Given these two intuitions, unstaged events and direct recording of them, it would seem impossible to consider an animated film as a documentary. Animated films consist of almost completely staged tableaus—drawings, miniatures, clay, even food or wood shavings (in the works of Jan Svankmajer). And animated movies offer no recording in Bazin’s sense of capturing the flow of real time and space. These films are made a frame at a time, and the movement we see onscreen doesn’t derive from movement that occurred in reality. And of course you can make an animated film without a camera, for instance by painting directly on film or assembling computer-generated imagery.

Recently, however, we’ve been faced with animated films that claim documentary validity. How is this possible? Maybe we need to rethink our assumptions about what documentary is.

In certain types of documentaries, especially those in the Direct Cinema or cinéma vérité traditions, the assumption that we’re seeing spontaneously occurring events holds good. But a documentary can consist wholly of staged footage. Think back to those grade-school educational shorts showing a tour of a nuclear power plant. Every awkward passage of dialogue recited by the hard-hatted, white-coated supervisor was scripted. The whole show was planned and rehearsed, but that doesn’t detract from the factual content of the film.

Go further. Recall those attack maps that are shown in war films, tracing the progress of an army through enemy terrain. Now imagine an entire film made of those animated maps. The maps might even be enhanced with a few cartoon images, as in the above shot from one of the Why We Fight films. The film would be entirely designed, presenting no spontaneous reality being captured by the camera. Yet it would plainly be a documentary, telling us that, say, the Germans marched into the Sudetenland in 1938 and proceeded on to Poland. So we don’t need photographic recording of actual events to count a film as a documentary either. Both the staging and the recording conditions don’t have to be present for a film to count as a documentary.

I’m not saying that the claims advanced in my nuclear-power film or my attack-map movie would necessarily be accurate. They might be erroneous or inconclusive or false. But that possibility looms for any documentary. The point is that the films, presented and labeled as documentaries, are thereby asserting that the claims and conclusions are true.

Film theorist Noël Carroll defines documentary as the film of “purported fact.” Carl Plantinga makes a similar point in saying that documentaries take “an assertive stance.” Both these writers argue that we take it for granted that a documentary is claiming something to be true about the world. The persons and actions are to be taken as representing states of affairs that exist, or once existed. This is not something that is presumed by The Gold Rush, Magnificent Obsession, or Speed Racer. These films come to us labeled as fictional, and they do not assert that their events and agents ever existed.

This isn’t just a case of a professor stating something obvious in a fancy way. Once we see documentary films as tacitly asserting a state of affairs to be factual, we can see that no particular sort of images guarantees a film to be a doc.

Take the remarkable documentaries made by Adam Curtis. These are in a way very old-fashioned. Blessed with a voice whose authoritative urgency makes you think that at last the veils are being ripped away, Curtis mounts detailed arguments framed as historical narratives. Freudian theory shaped the emergence of public relations, which was in turn exploited not just by business but by government (Century of the Self). Islamic fundamentalism grew up intertwined with US Neoconservatism, both being reactions to perceptions that the West was becoming heartlessly materialistic (The Power of Nightmares). Mathematical game theory came to form politicians’ dominant conception of human behavior and civic community (The Trap). The almost uninterrupted flow of Curtis’s voice-over commentary could be transcribed and published as a piece of nonfiction. True, there are some interpolated talking heads, but those experts’ statements could be printed as inset quotations.

What’s particularly interesting is that Curtis’ rapid-fire declamation accompanies images that often seem not to illustrate it, or at least not very firmly. Like the found footage in the preacher’s sermon “Puzzling Evidence” in True Stories, Curtis’ images are enigmatic, tangential, or metaphorical.

Here are a few seconds from the start of The Power of Nightmares. Eyes are staring upward, as if possessed.

We hear: [Our politicians] say that they will rescue us from dreadful . . .

The eyes are replaced by a shot of a man wearing a cowl, and as this image zooms back the commentary continues.

. . . dangers that we cannot see and do not . . .

Cut to a magician or mime demanding silence.

. . . understand.

Cut to rockets being fired.

And the greatest danger . . .

Cut to a procession of cars, seen from above, rounding a corner into a government compound at night.

. . . of all is international terrorism.

Cut to shot of security agent staring at us.

The ominous, not to say paranoid, tenor of the sequence is aided by the unexpected juxtapositions. For instance, you’d think that the shot of the iconic terrorist (anonymous, with automatic weapon) would be synchronized with the final line of the commentary, referring to “international terrorism.” Instead the commentary links the mention of terrorism to an image of government deliberation, and then to an image of surveillance (aimed at us, but also perhaps suggesting the previous high-angle shot was the spy’s POV). The wild-eyed close-up might belong to a terrorist, but is accompanied by claims about rescuing us from fearsome threats, so the eyes could also belong to someone panicked–especially since they contrast immediately with the sober eyes of the gunman in the cowl. Perhaps the first shot represents the fearful public ready to be led by the politicians playing on fear. And the insert shot of the mime becomes sinister but also comic, perhaps debunking the official position that our dangers are unseen and unknowable. In all, the sequence bubbles with associations that are less fixed and more ambiguous than we’re likely to find in a more orthodox documentary, like Jarecki’s Why We Fight.

My point isn’t to analyze the image/ sound relations in Curtis’s work, a task that probably demands a whole book. (This sequence takes a mere eleven seconds.) I simply want to propose that regardless of what pictures Curtis shows, his films are documentaries in virtue of a soundtrack constructed as a discursive argument that makes truth claims. The picture track often works on us less as supporting evidence than as a stream of associations, the way metaphors or analogies give thrust to a persuasive speech.

Just as we could have an account of Germany’s 1938 invasion of Czechoslovakia presented in cartoon form, we could imagine The Power of Nightmares illustrated with political cartoons. Once we’ve pried the image track loose from the assertions on the soundtrack, anything goes.

One example much on our minds now is Waltz with Bashir. Ari Folman interviews former Israeli soldiers. But instead of using film footage of their conversations and, say, still photos of the events in Lebanon they took part in, he provides (until the final sequence) drawings a bit in the Eurocomics mold of Tardi or Marc-Antoine Mathieu. The result takes the form of a memoir, admittedly. But in both literature and cinema, memoir is a nonfiction genre.

Another memoir supports the point. Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels, Persepolis and Persepolis 2, assert factual claims about her life. The claims are presented as drawings and texts rather than simply as texts, but that doesn’t change the fact that she presents agents and actions purported to have existed. True, on film the people whom she remembers are represented through voice actors speaking lines she wrote. But as with written memoirs (especially those that claim to remember conversations taking place fifty years ago), we can always be skeptical about whether the events presented actually took place.

Another memoir supports the point. Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels, Persepolis and Persepolis 2, assert factual claims about her life. The claims are presented as drawings and texts rather than simply as texts, but that doesn’t change the fact that she presents agents and actions purported to have existed. True, on film the people whom she remembers are represented through voice actors speaking lines she wrote. But as with written memoirs (especially those that claim to remember conversations taking place fifty years ago), we can always be skeptical about whether the events presented actually took place.

Turning Satrapi’s published memoir into an animated film did not change its status as a documentary. If we had contrary evidence, we could charge her with fibbing about her family life, her rebelliousness, or her life in Europe. But we’d be questioning the presumptive assertions the film makes, not the fact that it is drawn and dubbed rather than photographed from life.

We’re tempted to see the animation in these films as adding a level of distance from reality. We’re so used to fly-on-the-wall documentaries that we may be suspicious of the cobra-like caricatures of the female teachers in Persepolis or the hallucinatory dawn bombardment in Bashir. Yet animation can show things, like the Israeli veterans’ dreams, that lie outside the reach of photography. And the artificiality doesn’t dilute the claims about what the witnesses say happened any more than does purple prose in an autobiography. In fact, the stylization that animation bestows can intensify our perception of the events, as metaphors and vivid imagery in a written memoir do.

I realize I’m pointing toward a slippery slope here. Strip off the image track from Aardman‘s Creature Comforts and you have impromptu recordings of ordinary people talking about their lives. Those monologues could have been accompanied by documentary-style talking heads. Does that make Creature Comforts a documentary? I’d say not because the film doesn’t come to us labeled that way; it’s presented as comic animation using found soundtracks (like the movie based on the Lenny Bruce routine Thank You Mask Man). Then there are Bob Sabiston‘s rotoscoped films like Waking Life and The Even More Fun Trip, recently released on Wholphin no. 7. The latter (left) takes another documentary form, the home movie, as the basis for its animation. This seems to me an instance where the documentary category has the edge, but it’s a surely a borderline case.

I realize I’m pointing toward a slippery slope here. Strip off the image track from Aardman‘s Creature Comforts and you have impromptu recordings of ordinary people talking about their lives. Those monologues could have been accompanied by documentary-style talking heads. Does that make Creature Comforts a documentary? I’d say not because the film doesn’t come to us labeled that way; it’s presented as comic animation using found soundtracks (like the movie based on the Lenny Bruce routine Thank You Mask Man). Then there are Bob Sabiston‘s rotoscoped films like Waking Life and The Even More Fun Trip, recently released on Wholphin no. 7. The latter (left) takes another documentary form, the home movie, as the basis for its animation. This seems to me an instance where the documentary category has the edge, but it’s a surely a borderline case.

Animated documentaries are likely to remain pretty far from our prototype of the mode. Still, we should be grateful that even imagery that seems to be wholly fictional—animated creatures—can present things that really happen in our world. This mode of filmmaking can bear vibrant witness to things that cameras might not, or could not, or perhaps should not, record on the spot.

André Bazin’s arguments for the documentary basis of cinema are set out in “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” in What Is Cinema? ed. and trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967), 9-16. Noël Carroll’s argument that documentaries are framed as presenting “purported fact” can be found in Theorizing the Moving Image (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 224-259. On the “assertive stance” of documentaries, see Carl Plantinga, Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 15-25. Errol Morris interviews Adam Curtis here. Thanks to Mike King for pointing me toward The Even More Fun Trip.

PS 10 March: Harvey Deneroff writes:

Very much enjoyed your post on animated documentaries, a topic of some interest to and often discussed in the animation studies community. There was a panel on it during last year’s Society for Animation Studies conference and there will also be one at this year’s as well.

Two recent Oscar recipients for Best Animated Short Subject are also documentaries: Chris Landreth’s wonderful computer animated Ryan (produced by the NFB about animator Ryan Larkin, and features a lot of talking heads) and John Canemaker’s The Moon and the Son: An Imagined Conversation, which is about Canemaker’s father and mixes animation with home movies and photographs.

At least two winners in the Oscar Documentary Short Subject category were largely animated: Chuck Jones’ So Much for So Little (WB, 1949, which I believe was made for the US Public Health Service) and Norman McLaren’s Neighbours. The Story of Time, a 1951 British documentary which featured stop motion animation was nominated in the same category.

Also, the International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film includes a section for animated documentary films.

Thanks to Harvey for this. I’m not sure I’d categorize Neighbours as a doc, but it’s a long time since I’ve seen it. On Harvey’s site he also has a note quoting Ari Folman on the difficulty of funding animated docs. And thanks to Ryan Kelly and Pete Porter for reminding me of Winsor McCay’s Sinking of the Lusitania from 1918.

More light from the East

Useless (Jia Zhang-ke, China, 2007).

DB’s last communiqué from the 2007 Vancouver International Film Festival:

I’m so taken with José Luis Guerin’s En la ciudad de Sylvia (Spain/ France) that I’ll be devoting a separate blog entry to it soon. At Vancouver it was projected with his Unas fotos en la ciudad del Sylvia, a remarkable sketchpad for and rumination on the feature. Rubbed together, the two films throw off sparks. En la ciudad is in color and very tightly constructed, Unas fotos consists of hundreds of black-and-white stills linked by associations and intertitles, with no sound accompaniment. Guerin, an admirer of Murnau, says that as a young man he watched old films in “a sacred silence” and he wanted to try something similar.

Unas fotos may not be factual—call it a lyrical documentary—but it illuminates En la ciudad in striking ways and is intriguing in its own right. Structured as a quest for a woman the narrator met 22 years ago, the film moves across several cities and invokes as its patrons Dante and Petrarch, each of whom yearned for an unattainable woman. But this isn’t exactly a photo-film à la Marker’s La jetée; it uses dissolves, superimpositions, and staggered phases of action to suggest movement. The subjects? Dozens of women photographed in streets and trams. Some will find a creepy edge to the movie, but it didn’t strike me as the obsessions of a stalker. Guerin becomes sort of a paparazzo for non-celebs, capturing the many looks of ordinary women.

Watch this space for more on the many looks of Sylvia. For now, more Asian highlights from Vancouver.

Fujian Blue.

Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai have reunited for The Mad Detective (Hong Kong), which is as off-balance as you’d expect from its premise. Evidently spun off those TV series that feature telepathic profilers, the film stars Lau Ching-wan as a detective who solves cases by intuiting crooks’ “inner personalities.” We’re introduced to him crawling into a suitcase and asking his partner to throw it downstairs. After a few bumpy descents, he flops out and names the man who packed up a girl’s body the same way. Soon Lau is mentally reenacting a convenience-store robbery, and To/Wai cut together various versions of it as he plays with the possibilities.

Years after Lau leaves the force, his partner brings him back as a consultant to another case. By now, though, our mentalist has gone mental. The filmmakers get comic mileage, and some genuine poignancy, out of intercutting his hallucinations with what’s really happening. Lau envisions multiple personalities within the man they’re hunting, and as he traces out clues each personality flares up. To and Wai carry their dotty premise to a vigorous climax that multiplies the mirror confusions of both Lady from Shanghai and The Longest Nite. The brilliant sound designer Martin Chappell is back on the Milkyway team, making the effects and music magnify Lau’s heroic disintegration.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Lee Chang-dong, of Peppermint Candy and Oasis, has won his widest acclaim yet with Secret Sunshine (Korea). As your basic domestic crime-thriller Born-Again-Christian female-trauma melodrama, it’s undeniably gripping.

Secret Sunshine earns its 130-minute length, because Lee needs time to do several things. He traces the assimilation of a widow and her little boy into a rural town. Then he must follow the remorseless playing out of a harrowing crime. He makes plausible her succumbing to fundamentalist Christianity and her growing conviction that she needs to forgive the criminal. And there are more changes to come.

For me the most unforgettable moment was the heroine’s appalled confrontation, in a prison visiting room, with the man who wronged her. His unexpected reaction dramatizes how religious faith can cultivate both emotional security and an almost invincible smugness. Jeon Do-yeon won the Best Actress award at Venice for her nuanced performance, and Song Kang-ho, best known for The Host and Memories of Murder, lightens the somber affair playing a man of indomitable cheerfulness and compassion.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

I found Brillante Mendoza’s Slingshot (Philippines) quite absorbing. Hopping among various lives lived in the Mandaluyong slums, it’s shot run-and-gun style, but here the loose look seems justified by both production circumstances and aesthetic impact. It was filmed on actual locations across only 11 days, and though it feels improvised, Mendoza claims that it was fully scripted and the actors were rehearsed and their movements blocked. Most of the actors were professionals, intermixed with non-actors—a strategy that has paid off for decades, in Soviet montage films and Italian Neorealism. Slingshot reminded me of Los Olvidados, both in its unsentimental treatment of the poor and its political critique, the latter here carried by the ever-present campaign posters and vans threading through the scenes. I suspect that the final shot, showing an anonymous petty crime accompanied by a crowd singing “How Great Is Our God,” would have had Buñuel smiling.

Off to China for Fujian Blue by Robin Weng (Weng Shouming). The setting is the southeastern coast, a jumping-off point for illegal immigration. The plotline has two lightly connected strands. In one, a boys’ gang tries to blackmail straying wives by photographing them with boyfriends, going so far as to sneak in homes and catch the couples sleeping together. The other plot strand presents Dragon, a boy who’s trying to sneak out of China and make money overseas. The whole affair is reminiscent of Hou Hsiao-hsien’s Boys from Fengkuei, and in Dragon’s story we can spot overtones of Hou’s distant, dedramatized imagery. Yet Weng adds original touches as well, including an almost subliminal ghost of London across the blue skies of the China straits.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

Fujian Blue shared the festival’s Dragons and Tigers Award with Mid-Afternoon Barks (China) by Zhang Yuedong. The two films are very different; if Weng echoes Hou, Zhang channels Tati and Iosseliani. (When I asked him if he knew the directors, he didn’t recognize the names.) Mid-Afternoon Barks is broken into three chapters. In the first, a shepherd abandons his flock and wanders into a village. An unknown man shoots pool. Dogs bark offscreen. The shepherd shares a room with another visitor, but midway through the night, the innkeeper orders them to put up a telegraph pole. When he awakes, the man is gone, and so is the pole. He wanders on.

In the second episode . . . But why give away any more? In this relaxed, peculiar little film Beckett meets the Buñuel of The Milky Way and The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. As the enigmatic men without pasts or even psychologies wound their way through the long shots, Zheng’s quietly comic incongruities won me over long before the last dog had barked and the last ball had bounced.

Jia Zhang-ke is known principally for fiction films like Platform, The World, and Still Life, but from the start of his career he has shown himself a gifted documentarist as well. His In Public (2001) is a subtle experiment in social observation, and Dong (2006) made an enlightening companion piece to Still Life. Useless is more conceptual and loosely structured than Dong. Omitting voice-overs, Useless offers a free fantasia on the theme of China as apparel-house to the world.

The first section of the film presents images of workers in Guangdong factories as they cut, sew, and package garments. Jia’s camera refuses the bumpiness of handheld coverage; it opts for glissando tracking shots along and around endless rows of people bent over machines. (Now that fiction films try to look more like documentaries, one way to innovate in documentaries may involve making them look as polished as fiction films.) Jia also gives us glimpses of workers breaking for lunch and visiting the infirmary for treatment.

In a second section, Useless follows the success of a fashion house called Exception, run by Ma Ke. Her new clothing line Inutile (Useless) consist of handmade coats and pants that are stiff and heavy, almost armor-like, and that flaunt their ties to work and nature. (Some outfits are buried for a while to season.) Ending this part with Ma’s Paris show, in which the models’ faces are daubed with blackface, Jia moves back to China and the industrial wasteland of Fenyang Shaoxi. There he concentrates on home-based spinning and sewing. Neighborhood tailors patch up people’s garments while the locals descend into the coalmines. A former tailor tells us that he gave up his work because large-scale clothes production rendered him useless.

Jia’s juxtaposition of three layers of the Chinese clothes business evokes major aspects of the country’s industry: mass production, efforts toward upmarket branding, and more traditional artisanal work. Without being didactic, he uses associational form to suggest critical contrasts. The miners’ sooty faces recall the Parisian models’ makeup, and their stiff workclothes hanging on a washline evoke the artificially distressed Inutile look. What, the film asks, is useless? Jia shows industrial China’s effort to move ahead on many fronts, while also forcefully reminding us of what is left behind.

Thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Mark Peranson, and all their colleagues for a wonderful festival. They’re so relaxed and amiable, they make it look easy to mount 16 days crammed with movies. Be sure to check on CinemaScope, the vigorous and unpredictable magazine that makes its home in Vancouver. It gives you many gems online, but it’s well worth subscribing to.

Alan Franey, Director of the Vancouver International Film Festival; PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager; and Mark Peranson, Program Associate and Editor of Cinema Scope.

Back in Vancouver

DB again:

I sang the praises of the Vancouver International Film Festival in my first venture into blogging a year ago, so it’s a pleasure to report that this year’s event is no less captivating. Too many movies to take in, natch, so I’ll concentrate on two of the fest’s great strengths, documentaries and Asian films (programmed this year by both Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer). Top and bottom of today’s entry: glimpses of the two venues where I spend the most time: the Empire Granville 7 multiplex and the Pacific Cinémathèque a couple of blocks away, the latter offering ambitious programming to gladden the heart of any cinephile.

Two docus

10 + 4 (Iran) provides vignettes of Mania Akbari’s struggle to live with cancer therapy. The fact that she’s also the filmmaker, and that she starts, at Kiarostami’s suggestion, from the visual premise of 10, gives the film extra layers of interest. In fewer than seventy shots, most from within moving vehicles, the film presents a series of dialogues, usually between only two people. Since most major action takes place elsewhere, we watch and listen for signs of characters’ pasts, their relationships, and their states of mind.

We can trace Akbari’s development from cheery pride, going to parties despite her chemotherapy (“Every morning I thank God for make-up”), to anguish as the pain mounts and the treatments intensify. No viewer will forget the scene on a cablecar when she and Behnaz, from 10, reveal their different responses to their illness, and offscreen, examine each others’ mastectomies. In a final scene, Akbari, her hair now regrown, is confronted by another woman who warns her of using cancer as a weapon. The final words, heard under the credits—”I am using it, and I can’t give up the joy of this game”—reveal a psychological insight we rarely find in discussions of the social implications of illness.

Oatmeal-video visuals shot handheld and often out of focus, talking heads, dicey sound, overbusy editing—never mind. My Kid Could Paint That shows that we’ll forgive all sorts of technical faults if the subject, story, and ideas are gripping.

At one level, Amir Bar-Lev’s film simply traces how four-year-old Marla Olmsted was catapulted to celebrity when her dribbly paintings became collector’s items. Bar-Lev was lucky enough to be around Binghamton from more or less the start of her strange adventure, and he gained the family’s confidence. Soon enough, though, Bar-Lev is asking exactly how these paintings could wriggle into the artworld.

At one level, Amir Bar-Lev’s film simply traces how four-year-old Marla Olmsted was catapulted to celebrity when her dribbly paintings became collector’s items. Bar-Lev was lucky enough to be around Binghamton from more or less the start of her strange adventure, and he gained the family’s confidence. Soon enough, though, Bar-Lev is asking exactly how these paintings could wriggle into the artworld.

It’s partly because, he shows, experts are pretty evasive when it comes to explaining how to tell good abstract painting from bad. Can’t you tell just by looking, as we can when we appreciate the figurative work of old and new masters? Turns out it’s not so easy. Critic Michael Kimmelman suggests, somewhat vaguely, that even abstract art is about a “story”—if not in the picture, behind the picture. Marla, of course provides a great story, but the question of how to judge her oeuvre remains.

We might insist that an artwork’s goodness is intrinsic, regardless of the circumstances of its making. If we learned on good evidence an eighty-year old woman had composed The Marriage of Figaro, surely it wouldn’t lose its sublimity. But philosophers Arthur Danto and Denis Dutton have suggested that our information about how an artwork came to be is usually relevant to interpreting and judging it. Sure enough, collectors rhapsodized about the work when they thought Marla had done it, but they cooled after a 60 Minutes story suggested that the father had coached her, and perhaps even finished the pieces himself.

That raises another issue, encapsulated by a Binghamton journalist. She explains that if a story is to run long in the media, it has to be given steep ups and downs. Hyped at the start, Marla’s paintings are suddenly called con jobs, and even Bar-Lev starts to get doubtful. How the family tries to regain their credibility, and how Bar-Lev exposes his own hesitations and complicities, makes for a fascinating film.

My Kid Could Paint That touches on other matters, such as the world’s love of a prodigy, the money that drives the gallery scene, and the issue of how much craft, such as skill in drawing, we now demand of our artists. What shines through the intellectual issues is a childhood joy in picture-making. As portrayed here, Marla remains a kid, and she reminds us of the pleasure in gooping up a surface with our fingers. Sony Pictures Classics made a wise move in acquiring this engrossing movie.

Turning Japanese

I try mostly to blog about films I like, passing over the others in silence. Hammer jobs are fun to write and to read, and I confess to having indulged in a couple when I felt that historical or stylistic analysis could cast light on current films that were being overpraised for originality. By and large, though, I prefer what Cahiers du cinéma called the criticism of enthusiasm. Everyone should write about the films she admires, and let history sort them out.

But my admiration for Kitano Takeshi has been so great since I saw Sonatine back in the 1990s that I can’t let Glory to the Filmmaker! pass without a little comment. His previous foray into fake autobiography, Takeshis’, seemed to me pleasant enough in a casual way. Unless I’m missing something, however, Glory to the Filmmaker! is an unmitigated embarrassment. Gone are the surprising compositions and subtly daring cuts; gone too the elliptical narrative that has time for adolescent digressons. Glory! is nothing but adolescent digressions, sketches and skits that either cling to an unfunny premise, like the dummy Kitano that pops up now and then, or abandon their premises halfway through. The pastiches of Ozu and Kurosawa are slapdash and inexact, while the more purely Kitanoesque stretches work at very low wattage.

But my admiration for Kitano Takeshi has been so great since I saw Sonatine back in the 1990s that I can’t let Glory to the Filmmaker! pass without a little comment. His previous foray into fake autobiography, Takeshis’, seemed to me pleasant enough in a casual way. Unless I’m missing something, however, Glory to the Filmmaker! is an unmitigated embarrassment. Gone are the surprising compositions and subtly daring cuts; gone too the elliptical narrative that has time for adolescent digressons. Glory! is nothing but adolescent digressions, sketches and skits that either cling to an unfunny premise, like the dummy Kitano that pops up now and then, or abandon their premises halfway through. The pastiches of Ozu and Kurosawa are slapdash and inexact, while the more purely Kitanoesque stretches work at very low wattage.

Kitano is such an important filmmaker that you can’t ignore even something as offhand as this, but we have to hope for more.

Ten Nights of Dreams, a portmanteau feature based on stories by Soseki Natsume, is as uneven as these affairs usually are. The first chapter, a lovely episode by Jissoji Akio, is eerie in a subdued way, with some quietly canted compositions and some cutting reminiscent of the great Page of Madness. I also enjoyed Ichikawa Kon’s entry, a sober monochrome exercise. Most of the others, however, rely on turbocharged CGI and frantic grotesquerie—all justified by the indulgent premise that dreams are really, really weird.

Yamashita Nobohiro’s Matsugane Potshot Affair (2006), however, bowled right down my center lane. A crooked couple comes to a small town and their search for stolen bullion becomes one thread in a tangle of dysfunctional families and grubby sex. My last sentence does the film an injustice, though, because the laconic narration fills in the circumstances and backstory at such a leisurely pace that all your attention is on the grim comic byplay and furtive eroticism of the townfolk. Any movie that starts with a little boy feeling up what appears to be a woman’s corpse on a frozen lake signals its tone pretty straightforwardly.

As in Linda Linda Linda, the only other Yamashita I’ve seen (and mentioned here), the staging and shooting are quietly commanding. The shots average about 23 seconds, but they seem longer because the camera almost never moves. Lovely long takes with layers of depth and pockets of action captured in windows and paper doorways recall the great Japanese tradition of all-over composition. Yamashita provides several shots that could be filed in my gallery of funny framings. When you film this way, you have to know exactly where to put the camera, and several scenes—notably a confrontation among the thieves and the twin brothers—quicken areas of the frame we never normally notice. Movies like this remind you of the pleasure of having time to see everything.

I haven’t yet mentioned the film I enjoyed most, Jiang Wen’s The Sun Also Rises, and today I’m also seeing the new Suo (I Just Didn’t Do It) and some other enticing items. So I turn Chinese, and Japanese again, in my next entry.

For more blogs anchored to the festival offerings, go here.