Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Cinema for cheeseheads

Meg Hamel introducing a film at the gigantic Orpheum Theatre.

DB here:

Today a chatty, catching-up blog filled with peekaboo links. Lots to do, know what I mean? Or do you?

Excuses, excuses

Kristin and I meant to blog about the Wisconsin Film Festival last weekend. We really did. But I missed the first night because my plane from Hong Kong got in late, and on Saturday I felt enough jetlag to mope around in a desultory fashion. I did see Fay Grim, Ten Canoes, Vanaja, and of course Johnnie To’s Exiled (better than ever on that CinemaScope Orpheum screen). Kristin saw several more films than I did, and that was part of the problem: She was too busy watching films to blog about them. By the time she finished, the festival was over and we faced some looming deadlines.

Regrettably, we simply let our festival blog go. Kristin drove off to Toledo for a conference of the American Research Council in Egypt. A fine conference it was too, but preparing for that took away some time for blog duties. To meet our Internets obligations, I pulled out a general essay that was sitting on the shelf. It turned out to be one of our most popular ever.

Over the same days I was occupied with two publishing projects. First is the online version of my 1988 book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available here. In the original book, the frames taken from color films were reproduced in black and white. Markus Nornes of the University of Michigan, who first suggested putting the book online, wanted to replace those with color frames. Since virtually all the book’s pictures came out poorly in the pdf scans posted online, we decided to replace the black-and-white images with scans from my original negatives. Kristi Gehring, our stalwart assistant, digitized all the black-and-white stills, and Markus found the color frames. So in the next few months the good folks at the University of Michigan should be replacing the tawdry stills with nicer ones. A bonus: Markus and his colleagues are working on giving the stills a click-to-enlarge feature.

Over the same days I was occupied with two publishing projects. First is the online version of my 1988 book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available here. In the original book, the frames taken from color films were reproduced in black and white. Markus Nornes of the University of Michigan, who first suggested putting the book online, wanted to replace those with color frames. Since virtually all the book’s pictures came out poorly in the pdf scans posted online, we decided to replace the black-and-white images with scans from my original negatives. Kristi Gehring, our stalwart assistant, digitized all the black-and-white stills, and Markus found the color frames. So in the next few months the good folks at the University of Michigan should be replacing the tawdry stills with nicer ones. A bonus: Markus and his colleagues are working on giving the stills a click-to-enlarge feature.

I’ll also be adding a new Foreword to the book. That will reflect on the book’s approach and its reception, and I’ll add corrections and new thoughts. In all, the updated online version should be available in late September. It’s been quite a struggle to revive the old thing, as I’ve chronicled earlier, but several people have taken a lot of trouble to help, and I’m grateful. Because, you see, I believe that Ozu is the greatest filmmaker who ever lived.

The second publishing project is my Poetics of Cinema collection. Delays, endemic in academic publishing, have pushed it past its spring release date. I’ve just gotten page proofs, and indexing should take place in August. So the thing is now slated for October. It’s rather big and expensive: 500 book pages, with about 500 stills. About half the essays are new to the volume. If you want to lay down your plastic before seeing it, you can order it here.

Coming attractions

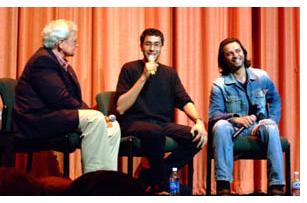

At the moment we’re preparing for Roger Ebert’s Festival of Forgotten and Overlooked Films, which comes up later this week. Previous years’ sessions have been excellent. Alongside, you see a 2006 photo of Roger interviewing Ramin Bahrani and Ahman Razvi, director and principal actor of Man Push Cart. Ramin’s new film, Chop Shop, is now in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes.

At the moment we’re preparing for Roger Ebert’s Festival of Forgotten and Overlooked Films, which comes up later this week. Previous years’ sessions have been excellent. Alongside, you see a 2006 photo of Roger interviewing Ramin Bahrani and Ahman Razvi, director and principal actor of Man Push Cart. Ramin’s new film, Chop Shop, is now in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes.

This year should be lots of fun: a chance to meet Herzog, Alan Rickman, Joey Lauren Adams, and other creative film folk…and to see Roger and Chaz again. The films run the gamut from Holes to Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. Kristin and I will be moderating the screening of Sadie Thompson, with an orchestral score by Joseph Turrin. Another musical event: a performance by Strawberry Alarm Clock. (Now I do feel old.) We hope to post at least one blog, with pix of course. Other blogomanes will be present, notably the audacious David Poland and the hyperenergetic Jim Emerson.

Speaking of festivals: the biggest of them all is coming up, and to celebrate it Turner Classic Movies is running, on 16 May, Richard Schickel’s documentary Welcome to Cannes. It samples the glitz but also affords information about the caste system of screening passes, the role of Cannes in easing films into the world market, and even the harm that a Cannes prize can do to a director. There’s neat footage of Godard and Truffaut preparing to shut down the festival in May of 1968–an event that a couple of interviewees claim was a turning point in the festival’s history. Along with the docu, TCM will screen four Palme d’or nominees/winners: The Big Red One, Blowup, Taxi Driver, and Pale Rider. But one question remains: Why does nobody think of the French as cheeseheads like us?

When we get back to Madison from Ebertfest, we have just enough time to pack for a month in New Zealand. Brian Boyd has arranged for us to come as guest lecturers to the University of Auckland, under the auspices of the Hood Fellowship.

When we get back to Madison from Ebertfest, we have just enough time to pack for a month in New Zealand. Brian Boyd has arranged for us to come as guest lecturers to the University of Auckland, under the auspices of the Hood Fellowship.

Kristin will be lecturing mostly from her Lord of the Rings study, The Frodo Franchise (for instance, here), but she also offers a talk on her Amarna research. I’ve got a more varied agenda: talks on CinemaScope, on ShawScope, on the history of cinema style, on the cognitive approach to film theory, and on scene transitions, as well as a visit to the Philosophy department. One or more of these items may materialize as an essay on this site some day. We’ll also be visiting the University of Otago, in Dunedin, for a brief stay and a lecture apiece.

While dwelling among the Kiwis, I hope to write a short online essay reflecting on our 1985 book The Classical Hollywood Cinema, which amazingly still arouses some discussion. I’ll also be thinking about plans for two further books, one on Hong Kong cinema and the other on a new approach to film theory.

We’re planning to maintain our blog while we’re away, recounting our activities down under, and posting some more general pieces that I’ve already prepared.

Just butter, hold the popcorn

But what about our film festival just past? To be blunt: A hell of a time was had by all. We screened 182 films and attracted our biggest audience to date, with 28,700 tickets sold. Not bad for a festival that starts on Thursday night and ends on Sunday night, held in a town of about 240,000. Isthmus, our free arts-and-politics paper, offered an outstanding preview, and other local coverage was enthusiastic, natch. The event earned a glowing first-page write-up from Charlie Olsky in Indiewire. The official wrapup is here. For more on Madison cinephilia, go to our earlier entry.

We know whom to thank. Festival director Meg Hamel, The Boss of It All, is pictured at the top, channeling Judy Garland’s Palladium sessions. Technical supervisors Erik Gunneson and Jared Lewis are the calm and cheerful gents pictured below. We also owe a lot to Tom Yoshikami, Karin Kolb, Stew Fyfe, and a host of volunteers, as well as to several university agencies, notably the Department of Communication Arts and the International Institute.

With Sundance 608 opening in a couple of months, we might be able to spread next year’s fest between the downtown (cozy, near the students, lots of eateries) and the west side (the Borders-Whole Foods demographic). And with our University Cinematheque screening weekly, Madison film culture offers something for everybody.

Erik and Jared pay homage to the canted angles of Hartley’s Fay Grim.

A many-splendored thing 12: The long goodbye

Two sides of the Triangle: Ringo Lam and Johnnie To.

My last day in Hong Kong, and still so much to say.

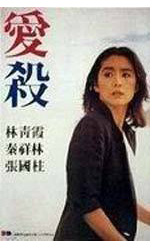

A few days ago I saw the new print of Patrick Tam’s Love Massacre (1981). It’s one of the stranger contributions to the Hong Kong New Wave of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The early stretches play as Antonioniesque scenes of alienation and loss, with a dash of Godard in the red/white/blue color design. About halfway through it becomes a movie about a stalker with a knife. Tam has great visual flair and devises some remarkable compositions and cuts, but I think that the film’s descent into gore comes too abruptly. We never understand the killer’s dementia, or his relation to his suicidal sister. Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia is as usual restrained and subtle in her performance, but such can’t be said for most of the other participants.

A few days ago I saw the new print of Patrick Tam’s Love Massacre (1981). It’s one of the stranger contributions to the Hong Kong New Wave of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The early stretches play as Antonioniesque scenes of alienation and loss, with a dash of Godard in the red/white/blue color design. About halfway through it becomes a movie about a stalker with a knife. Tam has great visual flair and devises some remarkable compositions and cuts, but I think that the film’s descent into gore comes too abruptly. We never understand the killer’s dementia, or his relation to his suicidal sister. Brigitte Lin Ching-hsia is as usual restrained and subtle in her performance, but such can’t be said for most of the other participants.

The seminar on Herman Yau’s films, “Herman’s Hermitage,” offered valuable critical commentary and a dialogue with Mr. Yau (right). A major cinematographer, Yau gained fame with two remarkably aggressive films, The Untold Story (1993) and Ebola Syndrome (1996). He has worked in many genres, lending a distinct local tang to cop dramas and even musicals. He’s a unique and energizing presence on the Hong Kong scene.

The seminar on Herman Yau’s films, “Herman’s Hermitage,” offered valuable critical commentary and a dialogue with Mr. Yau (right). A major cinematographer, Yau gained fame with two remarkably aggressive films, The Untold Story (1993) and Ebola Syndrome (1996). He has worked in many genres, lending a distinct local tang to cop dramas and even musicals. He’s a unique and energizing presence on the Hong Kong scene.

Two docus of note to fans of Asian film: In Development Hell (2007), Fukazawa Hiroshi chronicles the efforts of Teddy Chen to make Dark October, a film about Sun Yat-sen. As we follow Chen’s efforts, we learn of an earlier project undertaken by Chan Tung-man, father of prominent director Peter Chan Ho-sun. Tidbits about HK filmmaking emerge from comments by producers and directors.

Two docus of note to fans of Asian film: In Development Hell (2007), Fukazawa Hiroshi chronicles the efforts of Teddy Chen to make Dark October, a film about Sun Yat-sen. As we follow Chen’s efforts, we learn of an earlier project undertaken by Chan Tung-man, father of prominent director Peter Chan Ho-sun. Tidbits about HK filmmaking emerge from comments by producers and directors.

Yves Montmayeur’s In the Mood for Doyle (2006) follows Chris Doyle across a year of projects and interviews his collaborators, including Wong Kar-wai and Fruit Chan. Doyle appears somewhat calmer than I’ve seen him before (and certainly calmer than his reputation would indicate), and he shares some of his working methods.

Some points, such as the importance of place in determining a film’s style, Doyle has emphasized fairly often. But I’d never heard him say this before: “The choices you make push you in a certain direction, and that becomes what people call style.” Exactly right, methinks. Making a film is what technological historians call “path dependent”; one choice creates a limited but coherent set of future choices. The cascade of choices can precipitate into an overall stylistic pattern.

In a film with many good quotes, Peter Chan contributes another: “Working under the banner of a genre can give you more creative freedom.” In the Mood for Doyle and Development Hell would both be fine for festivals.

I have been written up a little in the Chinese-language press here and here. The loyal Golden Rock blogspot has pointed out that the stories misunderstood what I said in my blog about Johnnie To’s style.

Speaking of Johnnie To, as I frequently am: Last week he invited critics Lorenzo Codelli (below) and Shelly Kraicer and your obedient servant to dinner at his brother’s restaurant in Sai Kung. It was a wonderful meal, from the French sausages to the Kobe beef, prepared by the estimable Dracula Kwong. I never thought anybody would ever say this sentence to me: “And now meet Dracula.”

Soon Mr. and Mrs. To were singing American pop hits of the 1960s, including Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer.”

Ringo Lam, one of Hong Kong’s most celebrated filmmakers, dropped by.

Mr. Lam is the director of the middle section of Triangle, which I commented on in an earlier blog. In our conversation, he pointed out that the idea of taking off from another director’s story was something already present when he and Mr. To worked at TVB. The station would commission a 100-episode series (!), and either he or Mr. To would be responsible for the first five episodes. Then the next director would pick up the series and contribute another five installments, possibly taking the plots in entirely new directions. So this sort of serial production, a bit like Japanese linked verse, was already at work in Hong Kong popular culture.

Mr. Lam is known as bringing a level of harsh realism to the action pictures of the 1990s. In our conversation, he talked a lot about censorship troubles with the hard-edged School on Fire (1988). He also explained how he shot the jarring vehicle chase in Full Alert (1997) with virtually no retakes. “No problem! If other drivers see a crash or gunfire, they just drive around it.” Remarkably, Mr. Lam recalled reading our book Film Art when he was studying film in Canada.

Shu Kei has made a brief, gentle film called Ten Years, centered on a pair of dancers at the Academy for Performing Arts, where he is head of the School for Film and TV. Without words, accompanied solely by a Keith Jarrett piece, it tells its story through abstract compositions and carefully selected details.

A plush new local magazine, Muse, has published Vivienne Chow’s discussion of attitudes toward the festival. The story, not available online, discusses the festival’s efforts to broaden its public and seek commercial sponsorship. For many years after its launch in 1977 HKIFF ran as a municipal venture, but recently it went private. Now several high-profile companies like Giordano, Diesel, Starbucks, Shui On Land, and others support it. The festival has filled the central city with banners and billboards and created many red-carpet events, which generate press coverage and sizable local turnout.

Some long-time supporters feel that HKIFF has been pandering to the mass audience. They suggest that the festival’s principal mission was once to bring to Hong Kong the rare films, usually European, that wouldn’t be shown theatrically. Others resent the influx of viewers who aren’t strict cinephiles. One loyal festival attender is quoted in Chow’s piece: “The gimmicks and publicity brought in a lot of non-regulars who do not have much theater etiquette.” Long-timers complain of cellphone chatter and rude patrons.

As an outsider, I offer my $.02.

There are now a huge number of festivals, chasing the same films, lusting for red-carpet events. In Asia alone, Pusan, Tokyo, and Shanghai have become strong contenders, all more or less imitating Hong Kong. Moreover, the western world has finally recognized that Asia is a source of tremendous cinematic innovation, and now the big European and American festivals are cherry-picking films and filmmakers. If Wong Kar-wai can premiere his film at Cannes, why should he offer it to Hong Kong a month before? The HKIFF is hurt by its years of success: many of the filmmakers it introduced to the world are now snapped up by other festivals.

Just as important, the festival has offered comprehensive documentation of local cinema. Recognizing that Hong Kong film was largely unknown, the festival set about creating retrospectives and publications that brought to light the entire history of a great tradition. (On right, the festival’s book on the 1970s.) Without the precious catalogues published by the festival, both Chinese and westerners would know much less about Hong Kong cinema. The festival’s mission of education and scholarship has continued unabated, matched by the programs and publications of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

Just as important, the festival has offered comprehensive documentation of local cinema. Recognizing that Hong Kong film was largely unknown, the festival set about creating retrospectives and publications that brought to light the entire history of a great tradition. (On right, the festival’s book on the 1970s.) Without the precious catalogues published by the festival, both Chinese and westerners would know much less about Hong Kong cinema. The festival’s mission of education and scholarship has continued unabated, matched by the programs and publications of the Hong Kong Film Archive.

The festival shrewdly merged with a broader event, the Entertainment Expo, which included Filmart, the Asian Film Financing Forum, and the Asian Film Awards. Variety reports that a lot of business was done at Filmart, and the Awards were broadcast and rerun on Chinese television. In all, the festival seems to have created a unique identity for itself as a regional gathering place for both industry types and film fans.

Like all great festivals, this is really many festivals in one. Confronted by nearly 300 programs in 23 days, you’re in a vast cafeteria. You could, as I did, stick close to the Hong Kong retrospectives and archival shows. But you could also attend a rich array of avant-garde screenings, highlighted by the Paolo Gioli work. Or a documentary thread, including Enemies of Happiness and Nanking. Or a sampling of contemporary Asian film, showcasing dozens of works from South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, India, and on and on. Viewers craving contemporary European items had a chance to see eight films from Romania, eight from Germany, eight from the Nordic countries, and assorted titles from France, Italy, Portugal, and elsewhere; not to mention retrospectives of Visconti and Pedro Costa.

Add to this the enormous friendliness of everyone you encounter and the sheer exhilaration of being in this city. It would be ungrateful to ask for more. For the chance to see all these movies and wander through Hong Kong, I’d let Starbucks stamp its logo in my tooth fillings.

Will I see you here next year?

A many-splendored thing 8: The spice of life

Two more days at the Hong Kong film festival include…..

Seeing a lion dance auspiciously opening a new restaurant. I’d just eaten there last week, soon after it opened, with local filmmaker, critic, and educator Shu Kei. The meal included pig-lung soup; good!

Watching the unexpectedly solid Wo Hu (2006). Wong Jing is widely known as the great vulgarian of Hong Kong cinema; nothing is too lowbrow to be tossed into his movies. I like some of his work, but I worried when the opening credits of a serious picture like this listed Wong as producer. Despite my concerns, this turned out to be a strong cops-and-triads pic. The presence of Eric Tsang, Francis Ng, and Jordan Chan helps a great deal, and Marco Mak’s direction is efficient enough. The real strength is the script, with a plot that is unusually taut for a Hong Kong movie.

The cops have declared a mission to infiltrate the triads with 100, 500, 1000 moles—whatever it takes. The references to Infernal Affairs are evident (characters even mention the movie), but in some ways this is a subtler effort. The film follows three triads’ personal lives and interweaves the fate of a cop with his own secret. There are touches of humor, but mostly the mood is somber, accentuated by the dank, bleached-out look that’s so common today. There are sharp suspense passages and some genuine surprises.

The cops have declared a mission to infiltrate the triads with 100, 500, 1000 moles—whatever it takes. The references to Infernal Affairs are evident (characters even mention the movie), but in some ways this is a subtler effort. The film follows three triads’ personal lives and interweaves the fate of a cop with his own secret. There are touches of humor, but mostly the mood is somber, accentuated by the dank, bleached-out look that’s so common today. There are sharp suspense passages and some genuine surprises.

Wo Hu was much praised by local critics, and it seems to me the best of the recent crime films I’ve seen so far in the festival (Protégé, Undercover, Dog Bite Dog, and the surprisingly weak Confession of Pain). This is the one that could yield an interesting US remake. The title—get ready—translates as “Crouching Tiger.” The sequel, already announced, will be called Jia Lung: “Chasing Dragon.” The shamelessness of Hong Kong cinema isn’t dead quite yet.

Going on a rainy-day shopping circuit with Athena Tsui. Many of the old places supplying unusual and bootlegged DVDs have closed. Why? The government stepped up anti-piracy enforcement, and consumers can now get digital content online more easily. We did re-visit one place selling graymarket mainland versions of US, European, and Russian films, all for low prices (about US$3). Legit, I picked up mostly Japanese titles: Sabu’s Dead Run, the otaku hit Train Man, the Suo boxed set (didn’t have a DVD of Fancy Dance), and an unmissable item, The World Sinks, Except Japan. Go here for Twitchfilm’s coverage of the last-named.

The highlight was a trip to Comix Box in Sino Centre. It’s run by Neco Lo Che Ying, one of Hong Kong’s first independent animators, who started out in the 1970s. Neco was also the first to offer American superhero mags. Here he’s surrounded by some of his toys.

Thanks to Athena for the trip, the cocoanut-mango drink, and all the information about the HK film scene, including the factoids about Wo Hu.

Having dinner with Raymond Phathanavirangoon, who works for the energetic distribution company Fortissimo. Probably best known for handling Wong Kar-wai’s films, Fortissimo has established itself as one of the top distributors/ producers of ambitious international cinema (East Palace, West Palace, U-Carmen eKhayelitsha, Shortbus).

Among his other duties, Raymond makes presskits. This is seldom a creative endeavor, but Raymond’s results go far beyond the usual leaflet. He produces virtually museum-quality artifacts. His most flagrant kit promotes the Hungarian film Taxidermia, offering a marbled booklet in a shrink-wrapped styrofoam package.

Seeing James Yuen’s curious Heavenly Mission (2006). After several years in a Thai jail, young triad Ekin Chan wants to go straight. He asks an arms merchant to stake him to US$30 million, and he returns to Hong Kong to set up a vast charity. The cops don’t trust him, and neither do some of his old triad buddies. Problems ensue.

One of many crime movies screened in the Panorama section of the festival, this is neither the worst nor the best. The plot proceeds spasmodically, and our mysterious protagonist seems a little too passive. Nice to see Ti Lung again, though, playing an aging and pacific triad boss. Nice also to see for once Thailand treated not as hell but rather as purgatory, the place in which Ekin discovers spirituality and kindness. And, proving once more that there’s some little stab of pleasure in nearly every movie, we do get a nifty final shot.

Catching up with Soma films: Jouni Hokkanen, a regular at the HKIFF, gave me a sampler of several films he has made with another Finn, Simoujukka Ruippo. Their company is called Soma. You’ve probably heard of Soma’s most famous film, Pyongyang Robogirl (2001), which puts a traffic warden’s rigid moves to a techno beat.

Soma has made other films about North Korea, most ambitiously a survey of the nation’s cinema called The Dictator’s Cut (2005).

These entertaining and informative babies won’t be on YouTube. The Soma website is under construction, but it does give a list of the films, all of which would seem natural film festival choices.

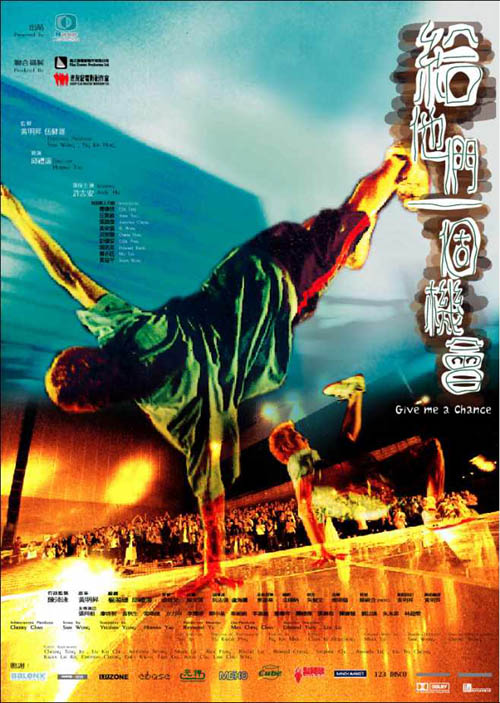

Enjoying in an old-fashioned way Herman Yau’s Give Them a Chance (2003): The notion of a movie about how HK teenagers become breakdancing stars didn’t seem promising, but it turns out to be a sweet piece of work. Yau has always had sympathy for grassroots life here, and he makes his ensemble plausible and ingratiating.

The kids, including a mute boy who apparently can spin on his head all night, are at once clumsy and sensitive, like most adolescents. They live in high-rises, struggling with broken families, but they retain honor and idealism. They look out for each other and try to take everybody’s feelings into account, thereby creating even more awkward complications. It’s a pleasure to see movie youths who aren’t bullies or triad wannabes, just good-hearted kids who want to make something of themselves (with a little help from Andy Lau).

The kids, including a mute boy who apparently can spin on his head all night, are at once clumsy and sensitive, like most adolescents. They live in high-rises, struggling with broken families, but they retain honor and idealism. They look out for each other and try to take everybody’s feelings into account, thereby creating even more awkward complications. It’s a pleasure to see movie youths who aren’t bullies or triad wannabes, just good-hearted kids who want to make something of themselves (with a little help from Andy Lau).

Yau, a rocker himself, treats the clichés of the musical film with casual zest. Romantic rivalries flare up, health problems keep a promising dancer offstage, youthful energy collides with old-fashioned tastes, and corrupt promoters try to discourage naïve hopefuls. Of course there are lively dance numbers. In the process, alienated brothers come together and the kids’ efforts are crowned by their appeal to—who else?—the ordinary people of Hong Kong.

At a time when most HK directors seem wall-eyed for the Mainland box-office, here is a movie that is utterly local. It even has two English titles, Give Them a Chance and Give Me a Chance, just going to show that it wasn’t made for us Anglos. Actually, though, it speaks to anybody.

I’ll be blogging more about Yau’s work soon, since the festival is giving him a retrospective and a seminar. In the meantime, you can check his website.

Korean monsters, Miami hard guys, and looping Tokyo

More from Vancouver from DB:

Bong Joon-ho, one of the most talented Korean directors working now, has in a few years proven himself adept in many genres. His first feature was the charming comedy Barking Dogs Never Bite (2000), and he followed that with one of the best recent cop movies I know, Memories of Murder (2003). Now The Host has broken Korean box-office records and won tremendous praise at Cannes last spring.

Naturally, there’s been a buildup of interest for the three screenings of The Host scheduled during the festival. The opening one is sold out, and the others are nearly full too. This morning there was a Forum discussion with Bong, moderated by Tony Rayns, and it proved to be a very interesting conversation.

Bong had wanted to make a monster movie ever since his childhood, when he looked out his window at the Han river and imagined a creature like the Loch Ness monster rising out of it. Eventually he was able to summon up the money to do so. The budget for The Host ran to about $11 million US, nearly half of which was used on special effects. (Bong points out that the ordinary Korean film is budgeted at about what he spent on fx.) He contracted the CGI out to several firms, including Peter Jackson’s Weta Digital and The Orphanage, a San Francisco company.

To save money Bong cut several monster shots, instead simply suggesting the creature’s presence through other means. He was inspired by Spielberg’s handling of Bruce the shark in Jaws: faced with Bruce’s constant mechanical failures, Spielberg used point-of-view shots and Williams’ score to signal when the shark was nearby.

Will there be a Host 2? Bong says that if there is, he wouldn’t be directing it. He envisions the possibility of something like the Alien series, where different directors turn each installment in different directions.

Tony Rayns set up the context for the discussion with his usual aplomb, and the audience coaxed Bong into wider comments. One listener asked what makes Korean audiences so eager to support their local movies. Tony pointed out that Korea has the most cosmopolitan and film-loving population in Asia, and Bong talked of the expansion of the market, with The Host going out on more than 600 screens. Also, Tony added, Korean movies tend to be very good.

I can’t refrain from a personal note. Bong greeted me warmly, and he reminded me that we met in Hong Kong in 1995, when his breakout short, Incoherence, screened at that festival. At that time he told me that he had read the (pirate) Korean translation of Film Art: An Introduction. I was happy that our book might have contributed a little toward his film career, and he cheerfully autographed my Vancouver catalogue with a little tribute to the textbook. Sometimes I forget that film researchers can affect filmmakers.

I was pleasantly reminded again at tonight’s reception. There I met Reg Harkema, an Ontario director, who became obsessed with Film Art‘s discussion of La Chinoise and nondiegetic inserts….so much so that Monkey Warfare, his film in this festival, is full of them! (Have to catch that.) And Ho Yuhang, director of the Malaysian movie Rain Dogs, knew Film Art but was more interested in my Ozu book. His autograph in my catalogue reads, “My friend, that f*cker, bought the only Ozu book left in the store. Damn!” Yuhang is also a big fan of film noir and he’s now scripting a crime movie.

Apart from hobnobbing with directors, I saw the disturbing docu Rampage, about black family life in one of Miami’s most poverty-plagued neighborhoods. All the young men, including one serving in Iraq, want to be rappers, and the most talented of all is only 14. But can he and his brothers survive gang warfare? I thought that the editing and sound were a little too aggressive, even somewhat sensationalistic, but as the film goes along it raises very tough issues concerning filmmakers’ ethical responsibilities. The question of whether the presence of a film crew changes the situation it’s filming is brought to the surface with really unsettling results.

I ended the day with pure fun. Tokyo Loop is a string of animated shorts, in varying styles, all aiming to comment on life in Japan’s metropolis. I’ve long thought that animated filmmakers don’t get enough credit, because we forget that they have to acquire an enormous understanding of how creatures and objects move. I was reminded of this again in seeing Tokyo Strut, a record of human and animal movement conveyed solely by dots of light, and the very funny Dog & Bone. Other filmmakers record movement, but animators have to know how to create it.

Finally, a greeting to Marlene Yuen and Ted Tozer, who despite my best efforts to hide my operating tactics, spotted me counting shots in screenings at Vancouver last year. Ted, if this interests you, check the CineMetrics website on the first page of this site.