Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Vancouver: Stories, spliced and stacked

Sarita (2019).

DB here:

Humans love stories, the more the better. As a result, many storytellers find ways to bring distinct story lines together. The most common way is to link them, through subplots involving major and minor characters. Viktor Shklovsky urged us to think of folktales, novels, and plays as “braided” out of several story lines. At other times, the stories are bracketed within a bigger plot. A character tells others about incidents in childhood, or characters tell completely detachable tales, as Scheherazade and Chaucer’s pilgrims do. Instead of braiding, we get embedding within a frame situation.

I started to think again about these options watching four films at the always exhilarating Vancouver International Film Festival. All were engaging, partly because they often mixed comedy and drama in rewarding ways. They also offer a nice menu of creative possibilities, exploited by ambitious filmmakers.

Screen life

An omnibus film can offer a frame story, as the British classic Dead of Night does, but most modern ones simply line up one tale after another, in blocks. Essentially these are short stories, and they tend to follow literary patterns.

One option is the “snapper,” the plot consisting of twists and a sting in the tail, a surprise ending. Edgar Allan Poe may have invented this format, O. Henry canonized it, and Roald Dahl gave it a grisly tenor. Diverting examples of the surprise-ending story can be found in the omnibus Spanish film Tales of the Lockdown (2020).

All five modules are comic, though sometimes in a macabre vein. Produced during the COVID-19 lockdown, somehow staged and shot remotely, each episode is cleverly scripted and elegantly directed. In one, a reclusive Milquetoast is pressed by an aggressive neighbor who wants to sell him a plan to expunge “bad vibrations” from his apartment. The Feng Shui saleslady gets more than she bargained for when she learns the source of those vibes.

In another, an aspiring hitman recruited by The Agency gets a remote tutorial from an experienced killer, who makes him practice techniques on a teddy bear and the dogs he snags from the neighborhood. A third, gentler episode is still tricky: we’re led to presume some things about a couple that turn out to be not valid–at least, not until the end. Sorry to be so elliptical, but films like this oblige you to avoid spoilers.

The most straightforward comedy concerns a woman auditioning by video for a TV part, aided by her husband who decides he could get a role as well. For a local audience, the fact that she is played by star Sara Sálamo and her actual husband, a Real Madrid football player, doubtless adds to the fun. The last episode, a black comedy, presents a rich couple’s extreme reaction to a tenant strike in one of their buildings.

The filmmakers have found many nifty ways to exploit the limited viewpoint enforced by lockdown. Naturally, remote conversations take place over laptops, which motivates minimal change of setting and little need for elaborate action scenes, or even ordinary staging in interiors. Offscreen action is likewise conveyed minimally, just by speech or noise in the world outside. The funniest moments in the fifth episode concern the rich couple learning they’ve received a “package” which we never see and must assume is problematic, since the thug on speakerphone says it’s “middle-aged.”

Confined settings have in effect created five “chamber plays” of the kind I’ve talked about before. This constraint allows directors to design and dress settings and find playful compositions to accentuate the plot twists that keep us glued to the screen.

In all, Tales of the Lockdown is a display of light and lively cinema craftsmanship. It’s heartening to see creative energy maintained in pandemic conditions. It premiered on Spanish Amazon Prime and would be worth looking for on that platform in other markets.

Food, memories, and the future

The major alternative to the twisty snapper tale is the “slice of life,” the muted drama of a situation that may change little or not at all. Here the emphasis falls on characters–their relations, their reactions, and their sensitivity to one another. The classic examples come from Chekhov and from Joyce’s Dubliners, but they’re also prevalent in what used to be thought of as the classic New Yorker short story of John Cheever or J. D. Salinger.

Pensive incompleteness of this sort well suits the Hong Kong film Memories to Choke on, Drinks to Wash Them Down (2019). Directors Kate Reilly and Leung Ming-kai have made three of the four stories fictional, treating them as vignettes of restrained realism. A Malay caregiver takes a grandma on an afternoon outing. She wants to go to a political rally where rice will be given out, and she hopes to meet old friends from her village. The old lady is forgetful, and her chatter recycles memories of her youth. The trip turns out to be something quite different, but she doesn’t realize it. The caregiver’s concern turns a simple duty into an act of kindness, as well as a tactful political gesture.

In “Toy Stories,” two brothers meet in their mother’s toy store, which is being sold, contents and all. As with the first episode, memory comes to the fore. The men play games and quarrel about the Power Rangers figures they loved. One, who has a son, tries to find something educational to bring back. He is barely hanging on financially, while his brother has lost his job. A final scene shows a bit of development in their situation, and gives room for a little hope; it’s the only episode that ends, “To Be Continued.”

The third episode is a wistful, Wongkarwai-ish almost-romance. Ruth, an American Caucasian, has come to teach in the school where John, a Chinese, teaches economics. Both are on their way elsewhere–Ruth to teach in Beijing, John to “try something different” in America. They bond over food. (Of course; this is a Hong Kong movie.) From their meeting at a vending machine to the street stalls and cheap restaurants they explore, Ruth learns of the joys of salted egg, pig intestines, and above all yuen yeung, a uniquely local mixture of tea and coffee.

These three stories quietly evoke distinctive Hong Kong culture–the older generation’s memories of moving to the colony, the Gen-X absorption in popular culture, and the particularities of local cuisine. The fourth segment builds on these in looking toward the future.

It’s a documentary showing the barista and cat-lover Jessica Lam running for a local council seat. She faces a pro-Beijing candidate, but she’s more grassroots. She’s also an amateur and runs a fairly minimal campaign. Although she does denounce police violence against demonstrators, the main force of this sequence is the portrait of a sincere young woman trying to improve neighborhood life. This is the only episode with a climax, the election-day vote count. And there is a twist when Jessica gives her final verdict on the results.

The omnibus format has proven a strong option for contemporary Hong Kong cinema, as witness the powerful Ten Years (2015). Memories to Choke On addresses not state oppression, as that did, but the politics of everyday life, the ways in which the sagging economy and the Chinese takeover ripple through the lives of ordinary people. The impact is quite specific: local audiences would know that the actor playing John in the third segment is Gregory Wong Chung-yiu, who is at risk of years of imprisonment for participation in a demonstration. Each story is a telling vignette, a slice of Hong Kong life that will engage overseas audiences and instill a mixed nostalgia in everybody who has ever visited what Chuck Norris in The Octagon (a very different movie) calls “the place.”

Camp as community

The option of embedding the stories within a frame can blur their edges more or less. Sarita (aka Tell Me Who I Am; 2019), an Italian film about refugees from Bhutan living in a Nepalese camp, could have been a straightforward documentary about problems of exile and resettlement under the auspices of the UN. Instead, it blends real-life stories of the refugees with a young girl’s quest to recover her memory. In what filmmaker Sergio Basso calls a more fanciful and energetic approach than a “tragic” documentary would give, we get a film close to magical realism–with DIY Bollywood musical numbers.

Sarita is more or less happy in the camp. She has friends to play and dance with, a school to attend, and every opportunity to worship her favorite god Shiva. But she often quarrels with her parents and wonders why they can’t go back home, a place she has never known. Shiva wipes Sarita’s memory, endowing her with the drive to ask questions of everyone around her. In this Rip van Winkle device, we are introduced to camp routines, as well as the history of her displaced neighbors.

Sarita visits her beloved teacher, only to find that he is often laid low by his injuries from torture sessions. People tell her of ethnic cleansing in Bhutan, of disappeared relatives and political oppression. Deciding that “building my future is easier than desiring my past,” Sarita turns to her immediate prospects. But her sister tells of the hardships of getting a university education. Taking her grandma to be treated for diabetes, she learns of people sleeping in a clinic as they wait days for treatment.

After the family is assigned a home in Oslo, she acquires a super-8 camera and cassette recorder and begins to document the life she will leave behind. Now the world she rejected seems precious. After Sarita has gone, we see her grandmother and those left behind lingering at a tree, studying mementos of their departed neighbors.

Counterpointing the harsh realities of daily routines and homesickness are moments of song and dance, in bursts of brilliant color and gymnastic choreography. We also get fantasy scenes, satires on overeager bureaucracy (the resettlement officer is a hyperactive Gene Kelly wannabe), and signs that youthful exuberance can’t be contained by drab regimentation. We hear “There is no childhood here” on the soundtrack as kids are shown inventing games and playing jacks with pebbles. The ending, however, has the poignancy of pure realism (even though it’s fictitious).

This film is an extraordinary achievement. Basso and his colleagues made it over ten years–filming without electricity and no funding from national governments or NGOs. Yet the minimal conditions enabled close collaboration with the camp residents. Seeing the children’s dances inspired Basso to make it a musical, and he gained access to local leaders. Thanks to the Kuleshov effect, Sarita even appears to interview the head of the resettlement office. Although the performers had some coaching from a theatre director and a choreographer, they clearly have natural gifts, particularly Sasha Biswas, who carries the film.

In the wake of the coronavirus, seventy Italian independent cinemas cooperated in making Sarita available on streaming platforms. There, Basso reports, it has found an encouragingly large audience. Another item to look for on the streaming menu in your area!

Visions of the good life, words of disquiet

One more film about memory, but now the memories themselves are captured on film. And the stories aren’t sealed off in blocks or gently embedded in a wider frame. They’re stacked.

Again, to say too much would soften your efforts to come to grips with the teasing, hypnotic My Mexican Bretzel (2019). Think of it as layered, like a cake.

The image track consists of a Swiss family’s home movies from the late 1940s through the early 1960s. In luscious color we see a couple leading a European life of leisure: summers on the beach, winter skiing, tours of postcard capitals, yummy meals with friends in open-air restaurants. The husband, a genial, brawny fellow, clowns for the camera, but most screen time is given to his wife, a willowy brunette with a radiant smile. The landscapes might have come straight out of Holiday, that oversize American magazine dedicated to worldwide vacationing.

The next layer is a written text, purportedly a diary of Vivian Barrett. This tells of the marriage. Vivian traces the efforts of husband Leon to make and market an antidepressant. Leon’s love of flying during the war has translated into his urge to travel widely, especially on his luxurious yacht. But as the years pass, Vivian starts to record her worries, her dissatisfactions, and the temptation of taking a lover. Her musings are interrupted by remarks she finds in an untitled book by the Indian guru Kharjappalli. (Sample piece of wisdom: “God also doubts your existence.”) The couple’s lives form the outline of an Antonioni film.

Léon is making a record too. He’s wielding the Daddycam as he documents all those vacations and breakfasts and views of Manhattan, Hawaii, Las Vegas, and aqueducts. Vivian has misgivings (“If you film, you don’t have to live”) but learns to use the camera herself, and even steer the yacht.

Finally there is an exceptionally discreet effects track. The home-movie scenes are eerily silent because there’s no voice-over, but occasional noises are dubbed in, and very rarely there’s a snatch of music. On the whole, the absence of musical cues for emotion renders the pictures and the diary texts all the more powerful. (Compare the emotional tug of Jóhannsson’s score for Last and First Men, a film that also “overwrites” mysterious visuals with a text sourced to a woman.) The result is a dry, unsentimental treatment of a crumbling marriage in the midst of Europe’s postwar boom.

Out of 29 hours of found footage Nuria Giménez and her colleagues have fashioned a fascinating film that is at once pure documentary and creative fiction. I like to think of it as another way to assemble a narrative–at one level simple chronology of a cosmopolitan couple’s life, on another the hidden story of voyages to Italy and elsewhere. I kept seeing the ghosts of Bergman and Sanders in this couple on the modern Grand Tour.

I knew about none of these films before encountering them at VIFF, which is of course one reason we cherish this and all other festivals. Granted, there’s reassuring pleasure in seeing the latest accomplishments of established and esteemed old hands (here Ozon, Petzold, Vinterberg, Rasoulof et al.). Just as valuable, though, is the jolt of seeing newcomers present beguiling variants on familiar traditions. Three of these films, as far as I can tell, are first features, and they offer fresh takes on stories we thought we’d seen before.

All are graced with sharp cinematic intelligence and offer pointed commentary on lives lived now and back then, close to home or far away. All remind me of why this VIFF wing is called Panorama. Every movie widened my vision.

Thanks, as usual, to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival. Thanks as well to programmer and consultant Shelly Kraicer for background on Memories to Choke On.

You can sample the films in their trailers: Tales of the Lockdown is here; Memories to Choke On is here; Sarita is here; and a particularly shrewd one for My Mexican Bretzel is here (incorporating, I think, footage not in the film). Giménez’s film won the Found Footage Award at Rotterdam. If you insist on knowing about how her film was made before seeing it, you can check this Film at Lincoln Center interview.

I hope other festivals, and streaming services, and even theatres will pick up all these films for wide distribution.

My Mexican Bretzel (2019).

Il Cinema Ritrovato: More and more

Il Cinema Ritrovato Book Fair (photograph Margherita Caprilli).

Kristin here:

I mentioned in my entry on the African thread at this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato that I filled in blank spaces in my program with a miscellany of intriguing films. Here are some of those films I saw, and others that David saw.

O Pão (1959)

Manoel de Oliveira’s first film, the gorgeous black-and-white documentary short, Douro, Faina Fluvial, was released in 1931. His last, Um Século de Energia, another documentary short, came out in 2015, the year of his death aged 106 (as did Visita ou Memórias e Confissões, a deliberately posthumous legacy film shot in 1982). That’s an 84-year career. I doubt any other filmmaker can claim as much.

Initially that career proceeded in fits and starts. He made more documentary shorts in the 1930s and then a black-and-white feature, Aniki-Boko (1942), during the war under an authoritarian regime. After the war he could not find funding and decided to study color filmmaking in Germany. During the 1950s he applied his resulting expertise to two documentaries: O Pintor e a Cidad (“The Painter and the City,” 1956) and O Pão (Bread). A beautiful print of the latter was shown in this year’s Ritrovati e Restaurati thread. It was to be his last film before he turned to feature filmmaking, though he never entirely gave up documentaries, particularly near the end of his life.

This hour-long film slowly follows the entire progress of bread, from wheat-fields to milling to baking to consumption. The images, whether in field or factory, are lovely, showing that Oliveira had indeed learned a great deal about color.

There is no voice-over narration, even during a lengthy scene in a large mill where technicians perform mysterious tests on samples of flour. The slow progression creates a soothing, almost mesmeric tone. Only toward the end does some social criticism emerge. A hungry urchin stealthily retrieves a roll dropped by a shopper, only to have it snatched away by a little street thug. Clearly bread, despite the lyricism of its production, is not for everyone.

Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Avval, Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Duvvum (1979)

Another must-see was Abbas Kiarostami’s early film, First Case, Second Case, also presented in the rediscovered-and-restored thread. Like Oliveira, Kiarostami began in documentary work. This remarkable film was started before the 1979 Iranian Revolution and finished after it–and then banned.

The film’s beginning rather resembles other Kiarostami openings, with a simple scene in a classroom. A teacher drawing the anatomy of an ear on a blackboard is interrupted by a knocking noise caused by one of his students. No one confesses or reveals who caused the noise, and the teacher suspends seven of the boys, who spend the next days in the hall outside the classroom.

This scene is revealed to be a 16mm film being shown to a succession of teachers, government officials, religious leaders, and the fathers of some of the boys. In the latter cases, some variant of the framing above is shown, with an arrow pointing to the son of the father being interviewed. Unseen, Kiarostami asks them the same question: did the boys do right in refusing to reveal who disrupted the class? Some of these interviewees became key figure in the Islamic Revolution. (Jason Sanders’ program notes for a screening of the film provide some information about this historical context.)

This “documentary” has of course been carefully staged. A page from Kiarostami’s script reveals how he designed the passing days of the boys’ suspension, with different ones standing or sitting each time. The illustration is from Ritrovato programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht’s blog entry on the film, where he credits First Case, Second Case with introducing the interview technique into the director’s work.

This first case shows the boys maintaining their refusal to identify the culprit. In a new scene, the second case, an alternative outcome shows one of the boys naming the guilty classmate to his teacher. Again, Kiarostami interviews many of the same people as to whether they believe the boy’s decision can be morally justified.

If not as charming as some of Kiarostami’s later work, First Case, Second Case contains a familiar combination of complexity and simplicity, as well as a fascination with people telling their own versions of events.

The film has been picked up by Janus in the USA, which should mean that it becomes available from Criterion on Blu-ray and/or its streaming service, The Criterion Channel.

Twelve O’Clock High (1949)

In recent years, Il Cinema Ritrovato has featured the films of a major Hollywood director as one of its main threads. This year it was Henry King. I managed to miss nearly all of his films. In part I feared that, since the auteur du jour is always one of the the more popular items in the program, the screenings would be crowded. Word of mouth suggested that they were.

Still, I had an afternoon free, and I wanted to guarantee myself a good seat for Varda par Agnès, showing later in the day. I went to an earlier screening in the same theater, and I was glad I did. Twelve O’Clock High is an impressive and entertaining film, if not an outright masterpiece.

Fitting into David’s set of innovations typical of the 1940s, the action is enclosed by a framing situation. A man we eventually discover was an American officer posted in England during World War II bicycles out into the countryside and visits the derelict remains of the military airport where he served. (Above, played by Dean Jagger in a role that won him a best-supporting-actor Oscar).

For a long time the story concentrates on General Frank Savage (Gregory Peck), who takes over command of an underperforming bomber unit in the same air station we saw at the beginning. He proves an absolute stickler for discipline, initially alienating the pilots he commands. Eventually he wins their respect, of course, and he learns to unbend a bit.

Eventually a series of air battles occur, with some very impressive and genuine combat footage, including aerial views of bombs exploding on their German targets. The film was presented in a nearly pristine 35mm print, which certainly contributed to my pleasure at having ended up at that screening somewhat by chance.

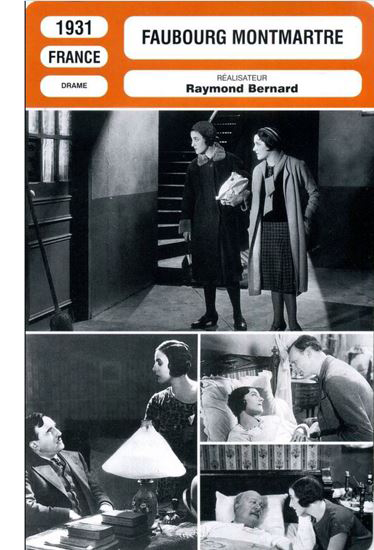

Faubourg Montmartre (1931)

I definitely planned from the start to see this film. I very much admire director Raymond Bernard’s 1932 World War I drama Wooden Crosses, his next feature after Faubourg Montmartre. Indeed, I had done a video on it for The Criterion Channel (“Observations on Film Art” #16 “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses“)

While a slighter film than Wooden Crosses, Faubourg Montmartre is quite stylish and technically impressive, considering that it was Bernard’s first sound film. In it he abandons his concentration during the silent era on historical epics (his best-known being The Miracle of the Wolves, from 1924).

Here he tackles a melodrama in a contemporary setting, centering around Ginette, a somewhat naive young working-class woman, played by popular star Gaby Morlay. She and her older sister Céline live and work in the titular district of Paris, the disreputable area of cheap entertainment and brothels. Céline works as a prostitute but tries to protect Ginette from such a life. Becoming more dependent on drugs, however, she nearly dupes Ginette into following her into prostitution.

Despite its grim setting, the film has many light moments, mostly provided by the amiable Morlay. It also contains some impressive musical numbers, one a variety number by Florelle and a café song about prostitution by Odette Barencey.

The film was yet another in the festival’s Ritrovati and Restaurati thread.

Georges Franju

There was an unaccustomed focus on documentaries this year, which presumably was the occasion for devoting a small thread to Franju. Of the thirteen shorts which he made or at least is tentatively credited with (most of them commissioned documentaries), eleven were shown. Judex, his fiction feature paying homage to the serial of the same name by Louis Feuillade, was also on the program.

I tried to see all the Franju shorts, since only Le Sang des bêtes (above) and Hôtel des Invalides are well-known in the US. The prints shown ranged widely in quality, some being in 35mm and some 16mm. En passant par la Lorraine was almost unwatchable, though most of the rest were in varying degrees acceptable.

The most interesting revelations were perhaps Mon chien (1955), a melancholy narrative based on the common habit of people abandoning their pets in the countryside. The amazingly callous parents of the little heroine dump her beloved German shepherd in the woods on their way to a vacation spot. The film follows the faithful animal’s trek home, only to find a locked house and a dog-catcher waiting. An empty cage signals that the animal was euthanized, with the voiceover of the girl calling forlornly for her pet. The other was Les poussières (1954), a lyrical survey of many kinds of dust generated in the world, ending in a strong anti-pollution message.

It was a pleasure to see this body of work brought together, but the screenings also demonstrate the pressing need to restore many of these films.

A Gabin tribute

DB here (with films I saw in boldface):

Jean Gabin has become emblematic of French cinema from the 1930s and after, so the several films devoted to him were welcome. Programmer Edward Waintrop included the classic Pépé le Moko (1936) but correctly assumed he didn’t have to show this crowd La Grande Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and Le Jour se Lève (1939). Edward’s catalog entry wisely emphasized how much Gabin owed to Julien Duvivier, an underrated director who helped the young actor find starring roles.

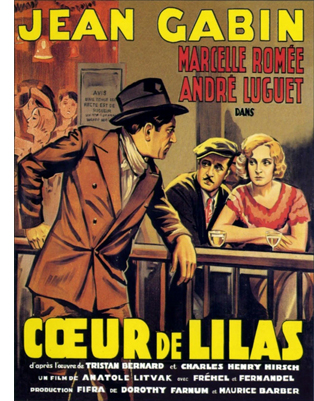

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

In her book on popular song in French cinema, our colleague Kelley Conway has written a superb analysis of Cœur de Lilas, and you can find a clip of Gabin’s big musical number here. Director Anatole Litvak handles his performance in a long tracking shot that keeps our attention fastened on Gabin’s half-scornful, half-boastful mug as he spits out lines about his girlfriend’s bedroom calisthenics (“The rubber kid. . . She dislocates you”).

Gabin plays the third point of a love triangle in Cœur de Lilas, but he’s somewhat more central to the lesser-known Du Haut en Bas (1933), a sort of network narrative that reminds us that The Crime of M. Lange (1936) isn’t the only film tracing the tangled passions in a courtyard community. More easygoing here but still a force to be reckoned with, Gabin plays a footballer with his eye on an aspiring teacher forced to work as a maid. Other plotlines, including Michel Simon’s raffish wooing of his landlady, intermingle in this thoroughly agreeable movie by the great G. W. Pabst.

A generous sampling of Gabin’s later career included La Marie du Port (1949), Le Plaisir (1951), Maigret tend un piège (1957), and the brutal Simenon adaptation Le Chat (1970), the first film I saw on my first visit to Paris. En Cas de Malheur (1957), an efficient plunge into sex and crime by Autant-Lara, features Gabin as a prestigious but dodgy lawyer drawn to the pouting self-regard of Brigitte Bardot. In youth and age, as a sort of French Spencer Tracy, Gabin could exude both relaxed joie de vivre and stolid menace. An icon, as we say.

Americana, urban and rural

State Fair (1933).

Speaking of Spencer Tracy, it was a pleasure to see this Milwaukee native in a long-neglected racketeer drama. Quick Millions (released May 1931) arrived in the middle of the first big gangster cycle and was overshadowed by two Warners hits, Little Caesar (January 1931) and The Public Enemy (May 1931). As part of Dave Kehr’s welcome second Fox cycle, Quick Millions had its own pungent force.

It traces the familiar trajectory of a working stiff, trucker “Bugs” Raymond, who claws his way to the top of the mob. Thanks to blackmail and crooked labor maneuvers (“The brain is a muscle,” he tells his moll), he winds up triggering a spate of gangland killings that eventually swallows him up.

Quick Millions was noticed as one of the earliest films to find a smart tempo for talkies, one that relies less on long speeches than snappy scenes delivering one point apiece. The passage of time is signaled by changing license plates, and the ending is a shrug, shoving Bugs’ death offscreen and giving him none of the tragic flourishes of Little Rico or Tom Powers. For almost every scene, the little-known director Roland Brown finds an unexpected twist in visuals or performance . Who else would film a sidling George Raft jazz dance from a high angle and then supply inserts of his legs, from behind no less?

Fox found more success with a folksy Grand Hotel variant based on the popular novel State Fair (1932). Henry King’s 1933 film was planned as an “all-star” vehicle, and it did boast Will Rogers, Janet Gaynor, and Lew Ayres. An Iowa family heads to the fair, aiming for blue ribbons in pickle preserving and hog-fattening. The son has a surprisingly carnal affair with a trapeze artist, while the daughter meets a roguish reporter who makes her rethink her engagement to a hick back home. State Fair‘s script gives the plot a happier ending than the book did, but that’s not necessarily a problem; we want these kind souls to enjoy a bit of glory.

Henry King became famous for rustic realism with Tol’able David (1921), a model for Soviet filmmakers, and Ehsan Khoshbakht’s King retrospective reminded us that he worked this vein a long time. From 1915 Twin Kiddies (a Marie Osborne vehicle) to Wait ‘Till the Sun Shines, Nellie (1952), this loyal Fox craftsman showed himself, like Clarence Brown at MGM, an adaptable director with an unpretentious gift for celebrating small-town life.

Still more, more…

Under Capricorn (1949).

I could go on about other films, such as Zigomar: Peau d’Anguille (“Zigomar, the Eelskin,” 1912), Victorin Jasset’s forerunner of Feuillade’s delirious master-criminal sagas. (In one episode, an elephant’s trunk fastidiously picks the lock on a circus wagon and drags away a strongbox.) Our next entry will spend a little time looking at a neat Genina film from 1919. In the meantime, I’ll sign off by mentioning two other high points.

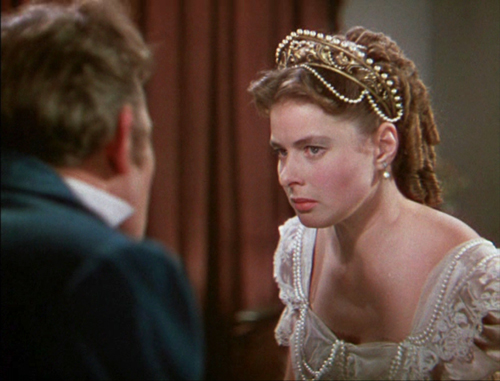

The pretty Academy IB-Tech print of Under Capricorn (1949) made me like the film quite a bit better than previous viewings. As ever, one high point was La Bergman’s virtuoso soliloquy admitting her guilt. Any other director of the time would have reenacted the crime in a flashback, but, in the shadow of Rope (1948), Hitchcock makes her squeeze out her confession in a ravishing single-take monologue running almost eight minutes.

Its power comes partly from the fact that the framing withholds the facial response of the man who loves her. He’s slowly understanding the depth of her devotion to her husband during penal servitude. “How did you live all those years?” he murmurs. How’d you think? Her glance flicks over him, in both guilt and defiance (above).

Finally, no film gave me more pure pleasure than the restoration of Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome (1959). Sony archivist Grover Crisp explained that the original prints had all been made from the camera negative (!) and so he had no internegatives or fine-grain masters to work from. Nevertheless, this digital version, made in 4K with wetgate scanning, looked superb.

I tend to judge Boetticher westerns by the strength of the villains, meaning that Seven Men from Now (Lee Marvin) and The Tall T (Richard Boone) sit at the top of my heap, but it’s hard to resist the laconic dialogue Burt Kennedy supplied everybody in Ride Lonesome. And the antagonists facing Randolph Scott here–Lee Van Cleef (brief but unforgettable), Pernell Roberts (the good-bad rascal), and sweet-natured dimwit James Coburn (on his way to rangy knife-wielding in The Magnificent Seven)–add up pretty powerfully. Against them stands Scott as vengeance-driven Brigade, an unyielding chunk of sweating mahogany.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator. Thanks also to Dave Kehr, Grover Crisp, Mike Pogorzelski, and Geoffrey O’Brien for talk about many of the classics on display.

The entire Ritrovato ’19 catalogue, with full credits and essays, is online here. There are also videos of many events, including master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Quick Millions was remembered several years after its release for “the rapid rhythm of its continuity.” See Janet Graves, “Joining Sight and Sound,” The New York Times (29 November 1936), X4.

John Bailey’s introduction to Under Capricorn included a revealing short explaining the Technicolor dye-transfer process. For further information there’s the remarkable George Eastman House Technicolor research site and of course James Layton and David Pierce’s superb book The Dawn of Technicolor.

Kristin discusses Kiarostami’s landscape techniques in a Criterion Channel Observations entry. In American Dharma, discussed by David here, Errol Morris reveals that Twelve O’Clock High was an inspiration for Steve Bannon’s political career.

The Ritrovato program notes credit Fréhal as the working-class singer in Faubourg Monmartre, but Kelley Conway’s Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in French Film (linked above) identifies her as Odette Barencey, a lesser-known chanteuse of the period who resembled Fréhal.

Opening shot of Ride Lonesome (1959).

Wisconsin Film Festival: Not docudramas, but docus as dramas

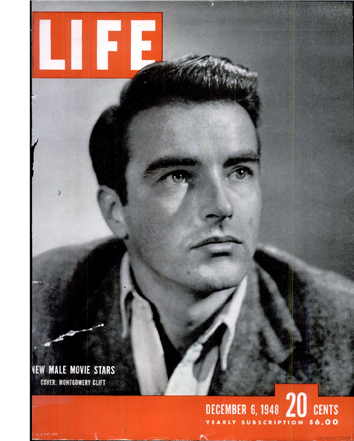

Making Montgomery Clift (2018).

DB here:

Our days and nights at our annual film festival would have been hopelessly frustrating if we hadn’t already seen several of the fine items on offer. At other festivals we caught Asako I and II, Ash Is Purest White, Dogman, The Eyes of Orson Welles, The Girl in the Window, Girls Always Happy, The Image Book, Long Day’s Journey into Night, Lucky to Be a Woman, The Other Side of the Wind, Peterloo, Rosita, Shadow, Styx, Transit, and Woman at War. As you can see, our programmers assembled a spectacular array of movies. Most of these we’d happily watch again, but there were so many new offerings we had to resist.

With this elbow room I could pay attention to three documentaries I’d been looking forward to. They had all the appeal of a fictional film, with keen plots and tricky narration and fascinating characters. It didn’t hurt that two were about world-class celebrities and the third appealed to my deepest conspiracy-theory instincts.

Heart of Glasnost

Werner Herzog’s Meeting Gorbachev was a surprisingly conventional effort for this legendarily odd filmmaker. As my colleague Vance Kepley remarked, Herzog typically makes documentaries of two types. He probes eccentric personalities (the “ski-flyer” Steiner, or a man trying to hang out with grizzly bears) or he treks into remote, dangerous landscapes (Antarctica, a swift-moving volcano, the fires of Kuwait).

But this portrait of Mikhail Gorbachev is neither. Herzog’s interview with the elderly but still vigorous Soviet leader is interrupted by biographical inserts tracing his career, his struggles, and his policies. Newsreel footage and other talking heads provide context in a mostly straightforward account of the man’s life and work. Only a story about tree slugs briefly diverts Herzog’s attention.

The film revives our appreciation of a politician many people have tried to bury. Gorbachev emerges as a thoughtful, upbeat man who tried to make the Soviet Union more democratic and open to the popular will, to create Communism with a human face. But he triggered events that cascaded too quickly. He broke up the USSR but also cleared a path for economic collapse and a corrupt kleptocracy. His suggestion for his tombstone inscription: We tried.

Herzog’s montages dramatize the breakdown of national borders, the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the coup that destabilized reforms while Gorbachev was away from Moscow. The main principle of swimming with sharks in a bureaucracy is: Don’t tell anybody what you’re going to do until you do it. The 1991 unseating of Gorbachev by Yeltsin reminds me of a second: Don’t take vacations.

Meeting Gorbachev is actually a double portrait, because Herzog puts a good many personal feelings into it. He remembers the emotion he felt as Germany reunited. Gorbachev’s call for “a common European home” rouses him to recall his youthful Wanderjahr when he walked across the continent.

Although I don’t think the name Trump is mentioned, his shadow falls over the whole film. Portraying a sane, reasonable leader today seems virtually a bid for controversy. Gorbachev reminds us of the reductions in nuclear weaponry that he negotiated with Reagan and Thatcher. “People say that Reagan won the Cold War. Actually, it was a joint victory. We all won.” The idea of pursuing policies that benefit the whole world seems oddly old-fashioned right now.

When Herzog gives us a glimpse of a robotic Putin peering down into the casket of Gorbachev’s beloved wife, we’re forced to register what Russia has become, and how the US is now complicit with it. Maybe this film has more of the director in it than I initially thought. As Herzog dared to declare in an earlier film, Nosferatu lives.

Unmaking an icon

Whenever I see Elizabeth Taylor and Montgomery Clift kiss in A Place in the Sun, I think: Here are the two most beautiful people in the Western world. I’m not alone. Clift was one of Hollywood’s most celebrated stars after the war, partly because he didn’t easily fit the molds of either the old guard or the new.

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).

The dapper guys with mustaches (William Powell, Fredric March, Melvyn Douglas) and the bashful beanpole boys (Cooper, Fonda, Stewart) were being challenged by what I’ve called in an earlier entry the brawny contingent. I’m thinking chiefly of Robert Ryan, Kirk Douglas, and Burt Lancaster, beefcakes with big hands and thrusting, sometimes confused energies. The hero might be a heel (Douglas) or a beautiful loser (Lancaster) or a bit of both (Ryan).

In this context, Clift looks like cannon fodder. Put him alongside Lancaster in From Here to Eternity, and you’ll find it hard to believe he’s the prizefighter; in that movie, only Sinatra looks skinnier. Delicate, with an innocent stare and an angular body, a wide-eyed Clift takes over his debut film, Red River (1948), from the lumbering John Wayne. Hawks claimed he told Clift that if he quietly watched the action from behind his tin coffee cup, he could steal every scene.

Clift carved out a space all his own. Late in his career, the tremor in his voice and a wary tilt of the head gave him antiheroic quality, as in Wild River (1960). Not for him the over-underplaying of Brando or the unpredictable gestures and dialogue cadences of James Dean. He has his own method, not The Method.

One of the many merits of Making Montgomery Clift, a fascinating documentary by Robert Clift and Hillary Demmon, is that it triggers such thinking about the actor’s craft. Emerging from a hillock of papers, home movies, video tapes, and audio tapes, the film documents two dramas–that of Clift’s life, and that of the process through which complex human beings get flattened into media clichés. As a bonus, we reap many insights into how actors shape their performances, sometimes against the grain of the script they’re handed.

On the life, we learn that Clift was often a buoyant, bisexual fellow, not the brooding and moody figure of legend. He was also a demanding artist who turned down juicy parts. When he signed up for a role, he insisted on vetting the script and sometimes rewriting it. In split-screen Clift and Demmon present the page on the left, scribbled up with Monty’s notes and excisions, and then run the scene alongside. The excerpts they give us from The Search and Judgment at Nuremberg show how a committed actor can strip an overwritten scene down to an emotional core.

If nothing else, Making Montgomery Clift shows us how performances shape movies: the actor as auteur. But it’s exactly this analysis of craft that’s missing from most film biographies. Those doorstop volumes revel in scandal and exposés because publishers think that a straightforward account of hard-won artistry–the sort of thing we routinely get in biographies of composers or painters–doesn’t suit movies. The result is glamor, excitement, sad stories, and banal interpretations rolled into one fat book.

This is the other drama so patiently traced by Clift and Demmon. They show how two 1970s biographies set a mold for the Tragic Homosexual story that has dogged the Clift legend ever since. Just as the filmmakers pay attention to the movies, they provide close readings of passages in the books, and the evidence of sensationalism, inaccuracy, and offhand speculation is pretty damning. One description of Clift’s injured face after his 1957 car crash savors brutal detail. And it’s not just the ambulance-chasers; passages from John Huston’s autobiography also radiate bad faith.

Clift understood that cookie-cutter journalism would oversimplify him. Thanks to the endless tapes he and his brother Brooks made of their phone conversations, we hear his quick condemnation of “pocket-edition psychology.” There’s a continuum between the tabloid headline, the talk-show time-filler, the celebrity memoir, and the bulging star bio. All try to iron out the wrinkles. During the Q & A, Robert Clift talked about traditional biographies as exercises in taxidermy: “It feels so real because it’s dead.” Hillary Demmon remarked that they wanted to “open up Monty to more readings.”

Making Montgomery Clift proves that academic talk about the “social construction” of this or that isn’t hot air. The film ranks with Errol Morris’s Tabloid as combining a fascinating life story (full of, yes, drama) with a serious argument about how celebrity culture reduces that story to captions and soundbites. Let’s hope the film makes its way to wider audiences, in theatres and on disc and streaming services. It belongs in the library of every college and university, so that students can get acquainted with an extraordinary performer, appreciate the art of star acting, and witness how the media shrink people to less than life size.

In the crosshairs of history

Like other baby boomers, I’m a connoisseur of conspiracy theories. But we have an excuse. Today’s kids grow up with school lockdowns and street shootings; we had assassinations. Patrice Lumumba (1961), Medgar Evers (1963), John Kennedy (1963), Lee Harvey Oswald (1963), the Freedom Summer murder victims (1964), Malcolm X (1965), Martin Luther King (1968), and Robert Kennedy (1968): this cavalcade of killings made political life seem a theatre of Jacobean intrigue.

Not the least of these was the 1961 death of the UN Secretary-General Dag Hammerskjöld. Hammerskjöld had pressed for peace in the Middle East and was a patient advocate for decolonization in Africa. En route to the breakaway Congolese province of Katanga, his plane crashed. For years many people, including former President Harry Truman, believed that the plane was shot down in order to murder Hammerskjöld.

So of course I had to see Mads Brügger’s Cold Case Hammerskjöld. It did not disappoint.

At first it seems cutesy, with the filmmaker dictating his findings to two African women typists, who occasionally turn to question him. He’s both pedantic and flamboyant (wearing white clothes to match the habitual outfit of a villain he will expose). In contrast there’s the veteran Hammerskjöld researcher Göran Björkdahl (on the right above beside Brugger). Björkdahl is a steady presence as the men question witnesses to the crash and then, crazily, set out to dig up the site. When they’re forbidden to do so, you might think that we’ve got another film about not making a film.

Instead, in the spirit of Morris’s Thin Blue Line, the story we’re investigating drifts into another story, and then another, as documents and witnesses and people who refuse to talk to the filmmakers lead to some appalling charges. Let’s simply say, to preserve the film’s shock value, that the Hammerskjöld case reveals SAIMR, a white supremacist militia for hire. The most horrifying claim about SAIMR and its leader is broached by a well-spoken mercenary purportedly haunted by guilt. His claim has been contested by researchers (as reported in the New York Times). Even if his charge doesn’t hold water, though, the existence of SAIMR seems well-documented.

We conspiracy theorists are often told that history proceeds by accident, not by intention. Yet some intentions succeed splendidly (viz. the killings itemized above), and some succeed by luck. Perhaps the darkest intentions chronicled in Cold Case Hammerskjöld were too crazy to be implemented. But that doesn’t lift responsibility from the feverish minds who dreamed them up, or from the institutions–perhaps mining companies, perhaps MI6 and the CIA–that gave them a hand. In an era when white supremacy has come on strong, Brügger’s film will remain the provocation it was intended to be.

One more entry will talk about still more films at this festival which so generously spoils us.

Thanks to film festival coordinators Jim Healy, Ben Reiser, Mike King, Zach Zahos, and their dedicated staff for this year’s wonderful event.

Cold Case Hammerskjöld.

Oscar’s siren song: The return: A guest post by Jeff Smith

A Star Is Born.

As you probably know, Jeff Smith has been our collaborator on Film Art: An Introduction and our Criterion Channel series “Observations on Film Art.” For the last few years (here and here and here), Jeff has offered his thoughts on the Academy’s music nominees. This time around, he concentrates on the songs.

Here’s a brief preview of the Best Original Song category in this year’s Academy Awards. I also include a prediction for this year’s winner. Of course, I’d be the first to admit I don’t even win my own Oscar pool. So you’ll want to take that into account before making any wagers.

A good old-fashioned tune

Mary Poppins.

The Academy has a long history of nominating songs from live action and animated musicals. This year is no exception.

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” from Mary Poppins Returns fits that bill, giving Disney a third straight nomination in this category. (“Remember Me” from Coco and “How Far You’ll Go” from Moana are the others.) Like the Sherman Brothers, who wrote songs for the original Mary Poppins, Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman derived inspiration from British Music Hall.

In fact, although actor Lin-Manuel Miranda insisted that he didn’t want his character to sound like Hamilton, Shaiman and Wittman wrote a patter section of “A Cover is Not a Book” for him, enabling Miranda to show off his unique skill set. With its tricky wordplay and fast pace, the classic patter song is a forerunner of the rhymes spat by rap and hip-hop artists. As Shaiman noted, “So we got very lucky there because we didn’t want to feel like we were pandering to the audience, to supply Lin with rap that would seem anachronistic.”

“The Place Where Lost Things Go” sits on the opposite side of the musical spectrum as a soft, mid-tempo ballad scored for strings and winds. Fans of the original Mary Poppins will note that it bears more than a faint resemblance to “Stay Awake.” Both songs are sung to the Banks children at bedtime in an effort to inveigle them to sleep. Whereas “Stay Awake” shows the über-Nanny using reverse psychology, “The Place Where the Lost Things Go” is a paean to memory, loss, and grief. The children’s mother has recently died and they further risk losing their beloved house. Mary Poppins reassures the children that they will be reunited one day with all their loved ones and that, in the meantime, their mother will forever have a place in their hearts.

The number is beautifully sung by Emily Blunt and it captures the sense of melancholy that gives Mary Poppins Returns its emotional heft. Still, it seems like a long-shot to take home the award. I admire Marc Shaiman’s work. He has written some absolutely iconic scores in the past, like The American President. And I’d love to see him recognized this Sunday, even if it is just for his phenomenal work on South Park: Bigger, Longer, and Uncut. But I fear that an Oscar statuette with his name engraved upon it is also in the place where the lost things go.

When corn meets pone

The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

The second nominee is David Rawlings and Gillian Welch’s “When a Cowboy Trades His Spurs for Wings.” It appears in the comically violent opening story of the Coen Brothers’ The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. It is sung as a duet by the titular character and the Kid, a mysterious gunslinger dressed in black. Buster has just been shot dead in a duel. In the song, the Kid imparts some lessons learned from his short, rugged life as a cowboy with Buster chiming in to provide harmony. Kid’s grimly acknowledges that he will suffer the same fate as Buster. It is just a matter of time.

Rawlings and Welch are long-time collaborators, having worked together on the former’s debut album. Rawlings has also produced albums by Welch and by Willie Watson, who plays the Kid. Adding to the sense of family reunion is the fact that Welch provided the voice of one of the Sirens in O Brother Where Art Thou? Among those enchanted by the Sirens? You guessed it – Tim Blake Nelson, who plays Buster.

In an interview in Variety, Welch describes the absurdity of the original pitch the Coens made to her and Rawlings:

It was a pretty straightforward thing: “Well, we need a song for when two singing cowboys gun it out, and then they have to do a duet with one of ‘em dead. You think you can do that?” “Yeah, I think we can do that,” she laughs.

In crafting the song, Rawlings and Welch pull off a rather neat trick. They’ve created something evocative of the “singing cowboy” films that inspired the first segment of The Ballad of Buster Scruggs. Yet is also connects with a larger tradition of mournful ballads that are part of folk and country music history. A lilting Texas waltz, the number is sparsely orchestrated, relying largely on guitar, harmonica, and vocals. The lyrics also make reference to a “bindling sheet.” As Welch noted, the word “bindling” was something she and Rawlings made up as a gesture toward the Coens’ fondness for anachronistic language. Yet it also works as a clever allusion to the “white linen” that is wrapped around a dying cowboy’s body in “Streets of Laredo.”

As was the case with Mary Poppins Returns, this song perfectly blends music and narrative, beautifully capturing the darkly humorous sensibility characterizing the Coens’ career. The lyrics are solemn, but Tim Blake Nelson’s yodeling lightens the tone to keep it from seeming maudlin. If I had a vote to cast, this is where I’d put it. Yet my gut tells me that the Academy’s beacon will shine on one of the other nominees.

A song for one of the Supremes

Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

The third nominee, “I’ll Fight,” was written by Diane Warren, a longtime Academy favorite. The song represents Warren’s tenth nomination, but she has never taken home top honors. This year, in an ironic twist, she may lose out to former co-writer Lady Gaga. (The two were nominated for “Til It Happens to You” in The Hunting Ground.) Warren admits that “I’ll Fight” is another of her “call to arms” songs as she has turned more of her energies toward films that support social causes.

One can easily make a solid prima facie case for “I’ll Fight” as the song to beat. It features a strong, soaring vocal performance by Jennifer Hudson, a previous Oscar winner for Dreamgirls.

Warren’s melody and lyric capture the inspirational vibe that is found in several previous winners, most recently “Glory” from Selma. And, of course, Warren herself seems long overdue.

Even so, “I’ll Fight” has a number of things working against it. It is featured in a documentary, and documentaries usually don’t get the exposure of more mainstream releases. It appears over The RBG’s closing credits, which mostly restricts the song to a summative function. And, unlike “All the Stars” and “Shallow,” the song failed to chart, an indication that it didn’t get much exposure in the music marketplace. I feel confident that Warren’s opportunity to make an acceptance speech will come someday. But on Oscar night, she’ll once again be the “bridesmaid” rather than the “bride.”

The battle of the titans

Black Panther.

For me, the race comes down to the remaining two nominees: “All the Stars” from Black Panther and “Shallow” from A Star is Born. Both tracks have gotten extraordinary exposure outside the films in which they appeared. The former was a chart hit in 25 countries, garnering steady radio airplay and thousands of streams and downloads in the process. The latter arguably did even better, charting in 40 countries, selling nearly 600,000 downloads and accruing almost 150 million streams. Both songs are fueled by star power: hip-hop sensation Kendrick Lamar for “All the Stars” and pop diva Lady Gaga for “Shallow.”

Lamar has just the right profile to woo Academy voters, even those in the music branch for whom “big beatz” and “flow” seem like foreign concepts. He has won thirteen Grammy Awards as well as the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for Music, becoming the first artist to do so from outside the domains of classical and jazz music. Billboard even compared Lamar to Shakespeare.

Although some music critics argue that “All the Stars” is not entirely typical of Lamar’s and SZA’s respective styles, it does fit beautifully with the overall vibe of Ryan Coogler’s pathbreaking film. The song begins with loping rhythms, electronic textures, and auto-tuned vocals. When Lamar drops the beat in the chorus, “All the Stars” gains intensity thanks to the layering of additional synthesizers and SZA’s melismatic topline.

The overall effect is one that neatly draws together Black Panther’s principal settings, being equal parts Wakanda and Oakland. The tension in the lyrics between the sung choruses and Lamar’s linguistic turns also restages the film’s central conflict: Prince T’Challah’s policy of peaceful co-existence vs. Killmonger’s thirst for violent world revolution. Appearing over the end credits, the number also works brilliantly with the shifting lines, shapes, and textures of the sequence’s graceful animation.

Lady Gaga, of course, supplies “Shallow” with its vocal fireworks. But she shares her nomination with three other collaborators, all of whom cut pretty large figures in the world of popular music.

Chief among them is superproducer Mark Ronson, who twirled the knobs on Gaga’s fifth album, Joanne in 2016. Ronson is perhaps best known for his smash hit, “Uptown Funk.” Yet, Ronson had already won three Grammy’s for his production of Amy Winehouse’s Back to Black long before he gave us his Bruno Mars earworm. Besides his production work for Gaga, Winehouse, and Mars, Ronson has collaborated with a “who’s who” of current stars and pop music legends: Adele, Lily Allen, Miley Cyrus, Kaiser Chiefs, Chance the Rapper, Janelle Monae, Duran Duran, Nile Rodgers, and Paul McCartney.

One of Ronson’s other songwriting partners, Anthony Rossomondo, shares the nomination for “Shallow.” Rossomondo is a guitarist and trumpet player who was a founding member of Dirty Pretty Things and toured with the Libertines as Pete Doherty’s replacement. Fans of British television might also remember Rossomondo as Pete Neon in The Mighty Boosh, the surrealist comedy series about a pair of failed musicians working in an alien shaman’s magic shop.

Rounding out the quartet of songwriters is Andrew Wyatt, still another songwriting partner of both Ronson and Gaga, who also penned tunes for Mars, Lil’ Wayne, Beck, Florence + the Machine, and former Oasis bad boy, Liam Gallagher. Wyatt also has previous experience writing for film. He composed four songs for the Hugh Grant/Drew Barrymore romantic comedy, Music and Lyrics, including the wonderful pastiche of eighties New Wave, “PoP! Goes My Heart.”

With so much musical talent on board, it is hard to see how “Shallow” could miss. Yet the song’s many virtues are enhanced by its perfect placement in the story. It was a lot to expect that one song could deliver something that a) pays off the romantic sparks of Ally and Jackson’s initial flirtation; b) signifies Ally’s leap of faith as she returns to the stage to complete Jackson’s arrangement of her song; and c) convince the audience that Ally could legitimately be the proverbial overnight sensation of the film’s title. “Shallow” delivers on all that and more.

The song begins with Jackson singing, “Tell me something, girl.” The first verse is sparely arranged for just voice and acoustic guitar. Jackson essentially baits Ally into claiming a spotlight he believes is rightfully hers. When Ally comes on stage, she begins the second verse in the lower part of her vocal register, adding a husky sensuality that captures the slow-burn of the couple’s simmering passions. Piano, violin, and pedal steel guitar slightly thicken the arrangement while maintaining the relatively soft dynamic level. An octave leap leads into the chorus, which Ally belts out with newfound confidence.

The lyrics serve as a metaphor for the character’s personal journey, her willingness to take the emotional and professional risks that Jackson had encouraged. This is Ally’s moment of self-realization. Yet it also foreshadows the relationship’s failure by previewing a future in which her stardom will overtake his.

This is followed by Jackson and Ally finally harmonizing together on the phrase, “In the shallow, the sha-ha-low.” Their voices blend, suggesting the consummation of their romantic connection onstage, if not yet in bed. Ally follows with a kind of vocal cadenza. No longer bound by lyrics, she sets free the “yargh” in her voice that rock critic Greil Marcus famously ascribed to Van Morrison’s Irish soul.

The addition of drums and bass enhance the big crescendo that leads into the final chorus. Jackson joins Ally at her microphone and the two finish the song with a final duet. The song is in G major, but ends on an E minor chord, another subtle hint of the sadness that ultimately consumes couple’s relationship.

As an Oscar nominee, “Shallow” has a lot to offer. It is a duet between a major movie star and a major star of the recording industry. It not only pays off a previous dangling cause, but also foreshadows later plot developments. Best of all, it takes the audience on an emotional journey that symbolizes the characters’ story arcs in microcosm. If the snatch of “Shallow” heard in the A Star is Born trailer proved surprisingly meme-worthy, the full performance of it in the film was indelible. Moreover, in a cheeky bit of self-mythologization, it invites viewers to consider “Joanne,” the flesh-and-blood being that sits just behind the Gaga mask.

Prediction: “Shallow”

I likely tipped my hand earlier, but I fully expect Lady Gaga and company to add Oscar to the Grammy and Golden Globe they’ve already won. If that happens, I’ll be content with the result, even if the memory of Tim Blake Nelson and Willie Watson’s duet tickles me every time I think of it. I’ve enjoyed Mark Ronson and Lady Gaga’s music for more than a decade. And if nothing else, an Oscar for Andrew Wyatt will balance the scales of justice. Back in 2008, I felt Wyatt was robbed when he failed to secure a nomination for a song Billboard called “the greatest fake 80s song of all time.” Well, if I see Wyatt clutching an Oscar come Sunday, you’ll hear a little PoP! go in my heart.

For an alternate take on this year’s music nominees, a real pop star from the eighties, Thomas Dolby, offers his perspective here. A report on a panel discussion at the Los Angeles Film School featuring several of the nominees can be found here.

Marc Shaiman and Scott Wittman talk about their work on Mary Poppins Returns here and here.

Gillian Welch discusses working with the Coen Brothers on The Ballad of Buster Scruggs here and here.

Diane Warren offers her perspective on writing “empowerment anthems” here and here. A deep dive into Warren’s career can be found on a Hollywood Reporter podcast featuring the 10-time Oscar nominee.

Finally, much ink has been spilled about the process of writing “Shallow” for A Star is Born. You can read more here and here and here and here.

Jeff Smith has provided us many guest blogs related to film music, most recently his discussion of the score for True Stories.

Music and Lyrics (2007).