Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Vancouver 2018: Two takes on two directors

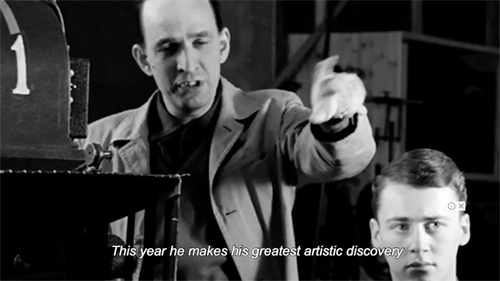

The Eyes of Orson Welles (2018).

DB here:

If you want to make a biographical documentary, you face problems of structure. Do you go chronological—start with birth, go through youth, maturity, and death? Or do you start in medias res, at the peak of fame or the depths of failure, and flash back to origins and development? Or do you do something else altogether? These are essentially the same problems of narrative that face the fiction filmmaker, but of course the documentarist also confronts gaps in the record, incompatible information, and the prospect that the story has been told before and may benefit from a fresh perspective.

Two documentaries at Vancouver tackled these problems in instructively different ways.

How to become famous: Work very, very hard

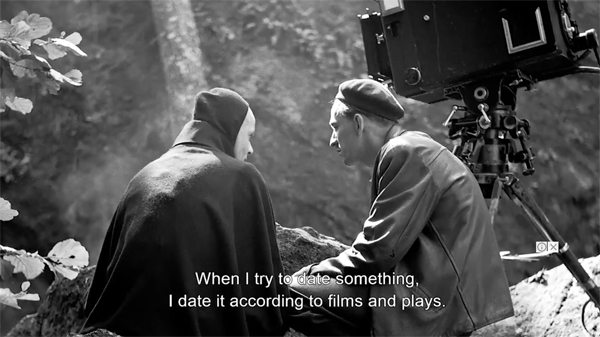

True to its title, Jane Magnusson’s Bergman: A Year in the Life picks Ingmar Bergman’s breakthrough in 1957 as its through-line. It was indeed quite a year: The Seventh Seal opened in January, Wild Strawberries in December, and Brink of Life was filmed in between (to open in early 1958). Very soon, Bergman won acclaim as one of cinema’s greatest artists. In the same annus mirabilis Bergman directed a TV drama and four theatre productions, including a monumentally successful five-hour version of Peer Gynt. All this he accomplished while suffering intense stomach pain; for part of the year he was in the hospital.

To survey only the events of January through December would leave us in the dark about the director’s full accomplishment, so the calendar format becomes a sort of clothesline on which incidents from all across his life are pinned. Since Bergman’s published memoirs are notoriously unreliable, Magnusson says that the films are more faithful records of his life and obsessions. But she also opens up many documents that fill in or correct his account, and the result becomes a fairly chronological survey.

For example, early in the documentary we learn of Bergman’s real relation to his father, his youthful admiration for Hitler during his stay in Germany (“I shouted like the others. I raised my hand like them”), and his first lover Karin Land, a spy for Finnish intelligence. As the film proceeds through 1957, it surveys his prior career and points ahead as well. Through associational links, motifs in The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, along with a survey of his childhood and his sexual partners, in effect provide flashforwards to Persona, Fanny and Alexander, and other later works.

The wellsprings of Bergman’s astonishing 1957 output are only hinted at. He was obviously a workaholic, as several commenters point out. One observer reminds us that Fassbinder had years that were as brutally productive, but he owed his stamina to drugs; for Bergman, the fuel was Swedish yogurt, Marie Biscuits, and sex.

Still, I wonder whether advancing through the Swedish film business, a rather industrially strict one, may have accustomed him to a killing pace. He started as a screenwriter at age 26, and he took up film directing two years later (not an uncommon age to begin). From 1948 on, he often signed two films a year as director and a third as a writer. You could make a case that his first breakthrough was really 1953, with the remarkable duo Summer with Monika and Sawdust and Tinsel. From the start, he was directing plays as well; in that same 1953 he mounted five. 1957 seems a landmark because the two films of that year became official international classics, winning festival prizes and wide distribution, but the man’s volcanic drive seems to have been there for a decade before.

In any case, the year-in-the-life format provides a handy point of entry into an astonishing, lengthy career. Magnusson has excavated many valuable documents and collected striking testimony, not least from coworkers whom the great man energetically humiliated. I learned a lot, not least that you can free up your documentary from the constraints of sheer chronology.

The Great Man draws

The same lesson issues more strikingly from Mark Cousins’ essayistic The Eyes of Orson Welles. Welles was of course another workaholic, moving across media freely. His energy was no less titanic than Bergman’s. For years we’ve known Welles the stage director, Welles the radio impresario, Welles the actor, and Welles the moviemaker. Now Cousins shows us Welles the graphic artist, and it’s a captivating, revelatory angle.

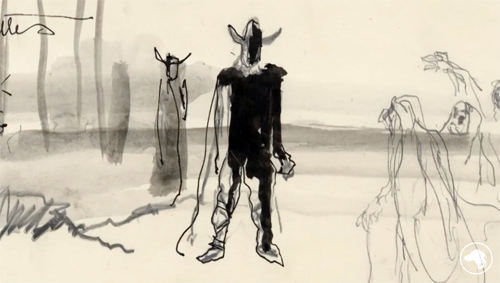

Welles started drawing as a child, and he later declared that painting was more important to him than filmmaking. Cousins examines hundreds of pictures archived at the University of Michigan and held by Welles’ daughter Beatrice. His film argues, with shrewd penetration, that a pictorial sensibility was central to Welles’ creative project. “You thought with lines and shapes. Your films are a sketchbook.”

How to structure this exploration? The film appears to offer trim boxes within boxes. Framing it all is a letter written and spoken by Cousins to the departed Welles. That apostrophe is in turn broken into numbered parts, some of which are in turn chopped into short topical segments. But these are engagingly digressive and untidy. For instance, part 3, devoted to Welles’s loves, skips from love of places, to love of vision itself (and Dolores Del Rio in Bird of Paradise), to love of chivalry, to omnivorous love (male friends), and finally to guilt over the death of love. A bit of Borges, a dash of Chris Marker: the swarming categories rub together in a cubistic way that Welles himself would probably have enjoyed.

In this porous, expanding design, Cousins takes us through familiar biographical terrain. The idea of Welles the graphic artist functions like 1957 in Magnusson’s film, a convenient wedge to open up episodes from family life and professional career. But Cousins brings out the pictorial side of well-covered material, such as the stage designs for the Harlem Macbeth. And he gains a lot from the frankly personal perspective. By writing a letter, he can ask rhetorical questions, mull over associations, imagine how Welles would view the modern world, and freely speculate on hidden autobiographical elements. “You wanted to be Falstaff, but you were Prince Hal.”

I came to Cousins’ film expecting a treatise on Welles’ cinematic style, and we get doses of that, but in unexpected ways. It turns out that most of his drawings don’t look a lot like his shots. Cousins floats the idea that Welles’ stay in Chicago, city of skyscrapers, may have tutored him in the low angles we see in his movies, but this seemed to me a stretch. Sketches of faces do, however, remind us of his fascination with actors, and of course his plans for sets, both on stage and on film, are very revealing.

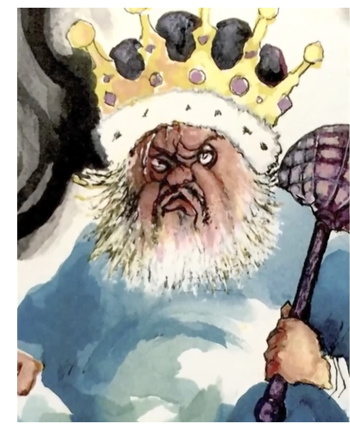

Cousins is very convincing on iconography. In both drawings and films there’s a recurring image of facelessness, which I had never noticed. There’s also the motif of domination and failed kingship, rulers who “can’t escape their own power,” and these ideas lead Cousins to a brilliant discussion of Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. And looking at the art resensitized Cousins to Welles’ cinematic strategies, whether or not they can be directly traced to a source. He points out the odd symmetrical camera movements that follow a cigarette passed along a lounging Rita Hayworth in Lady from Shanghai. This is a critic’s film, and the observations would be worthwhile even without the biographical pegs they hang on.

Cousins is very convincing on iconography. In both drawings and films there’s a recurring image of facelessness, which I had never noticed. There’s also the motif of domination and failed kingship, rulers who “can’t escape their own power,” and these ideas lead Cousins to a brilliant discussion of Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. And looking at the art resensitized Cousins to Welles’ cinematic strategies, whether or not they can be directly traced to a source. He points out the odd symmetrical camera movements that follow a cigarette passed along a lounging Rita Hayworth in Lady from Shanghai. This is a critic’s film, and the observations would be worthwhile even without the biographical pegs they hang on.

The obvious comparison is with the drawings of Eisenstein, perhaps more skillful than Welles’s, but equally suggestive of the filmmakers’ obsessions. Like Eisenstein as well, Welles shows a rueful humor in his sketches. Cousins acknowledges this streak in yet another section, a hypothetical posthumous reply from Welles to Cousins’ letter. Welles chastises his biographer for playing down the lighter side of his films and pictures. This is nicely illustrated by charming drawings for Christmas cards Welles sent his children. But Cousins shows the fun running down. Over the years Santa’s face droops and wobbles, the eyes grow hollow and the mouth goes slack. Santa as another ageing Welles tyrant? A teasing juxtaposition like this offers another reason to let The Eyes of Orson Welles train ours.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

For more on Bergman and Welles, see our categories devoted to the directors, on the right. A list of Bergman’s productions in film and other media is here.

Bergman: A Year in the Life (2018).

Is there a blog in this class? 2018

24 Frames (2017)

Kristin here:

David and I started this blog way back in 2006 largely as a way to offer teachers who use Film Art: An Introduction supplementary material that might tie in with the book. It immediately became something more informal, as we wrote about topics that interested us and events in our lives, like campus visits by filmmakers and festivals we attended. Few of the entries actually relate explicitly to the content of Film Art, and yet many of them might be relevant.

Every year shortly before the autumn semester begins, we offer this list of suggestions of posts that might be useful in classes, either as assignments or recommendations. Those who aren’t teaching or being taught might find the following round-up a handy way of catching up with entries they might have missed. After all, we are pushing 900 posts, and despite our excellent search engine and many categories of tags, a little guidance through this flood of texts and images might be useful to some.

This list starts after last August’s post. For past lists, see 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017.

This year for the first time I’ll be including the video pieces that our collaborator Jeff Smith and we have since November, 2016, been posting monthly on the Criterion Channel of the streaming service FilmStruck. In them we briefly discuss (most run around 10 to 14 minutes) topics relating to movies streaming on FilmStruck. For teachers whose school subscribes to FilmStruck there is the possibility of showing them in classes. The series of videos is also called “Observations on Film Art,” because it was in a way conceived as an extension of this blog, though it’s more closely keyed to topics discussed in Film Art. As of now there are 21 videos available, with more in the can. I won’t put in a link for each individual entry, but you can find a complete index of our videos here. Since I didn’t include our early entries in my 2017 round-up, I’ll do so here.

As always, I’ll go chapter by chapter, with a few items at the end that don’t fit in but might be useful.

[July 21, 2019: In late November, 2018, the Filmstruck streaming service ceased operation. On April 8, 2019, it was replaced by The Criterion Channel, the streaming service of The Criterion Collection. All the Filmstruck videos listed below appear, with the same titles and numbers, in the “Observations on Film Art” series on the new service. Teachers are welcome to stream these for their classes with a subscription.]

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

David writes on the persistence of classical Hollywood storytelling in contemporary films: “Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017.”

In FilmStruck #5, I look at the effects of using a child as one of the main point-of-view figures in Victor Erice’s masterpiece: “The Spirit of the Beehive–A Child’s Point of View”

In FilmStruck #13, I deal with “Flashbacks in The Phantom Carriage.”

FilmStruck #14 features David discussing classical narrative structure in “Girl Shy—Harold Lloyd Meets Classical Hollywood.” His blog entry, “The Boy’s life: Harold Lloyd’s GIRL SHY on the Criterion Channel” elaborates on Lloyd’s move from simple slapstick into classical filmmaking in his early features. (It could also be used in relation to acting in Chapter 4.)

In FilmStruck #17, David examines “Narrative Symmetry in Chungking Express.”

Chapter 4 The Shot: Mise-en-Scene

In choosing films for our FilmStruck videos, we try occasionally to highlight little-known titles that deserve a lot more attention. In FilmStruck #16 I looks at the unusual lighting in Raymond Bernard’s early 1930s classic: “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses.”

FilmStruck #3: Abbas Kiarostami is noted for his expressive use of landscapes. I examine that aspect of his style in Where Is My Friend’s Home? and The Taste of Cherry: “Abbas Kiarostami–The Character of Landscape, the Landscape of Character.”

Teachers often request more on acting. Performances are difficult to analyze, but being able to use multiple clips helps lot. David has taken advantage of that three times so far.

In FilmStruck #4, “The Restrain of L’avventura,” he looks at how staging helps create the enigmatic quality of Antonionni’s narrative.

In FilmStruck #7, I deal with Renoir’s complex orchestration of action in depth: “Staging in The Rules of the Game.”

FilmStruck #10, features David on details of acting: “Performance in Brute Force.”

In Filmstruck #18, David analyses performance style: “Staging and Performance in Ivan the Terrible Part II.” He expands on it in “Eisenstein makes a scene: IVAN THE TERRIBLE Part 2 on the Criterion Channel.”

FilmStruck #19, by me, examines the narrative functions of “Color Motifs in Black Narcissus.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

A basic function of cinematography is framing–choosing a camera setup, deciding what to include or exclude from the shot. David discusses Lubitsch’s cunning play with framing in Rosita and Lady Windermere’s Fan in “Lubitsch redoes Lubitsch.”

In FilmStruck #6, Jeff shows how cinematography creates parallelism: “Camera Movement in Three Colors: Red.”

In FilmStruck 21 Jeff looks at a very different use of the camera: “The Restless Cinematography of Breaking the Waves.”

Chapter 6 The Relation of Shot to Shot: Editing

David on multiple-camera shooting and its effects on editing in an early Frank Capra sound film: “The quietest talkie: THE DONOVAN AFFAIR (1929).”

In Filmstruck #2, David discusses Kurosawa’s fast cutting in “Quicker Than the Eye—Editing in Sanjuro Sugata.”

In FilmStruck #20 Jeff lays out “Continuity Editing in The Devil and Daniel Webster.” He follows up on it with a blog entry: “FilmStruck goes to THE DEVIL”,

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

In 2017, we were lucky enough to see the premiere of the restored print of Ernst Lubitsch’s Rosita (1923) at the Venice International Film Festival in 2017. My entry “Lubitsch and Pickford, finally together again,” gives some sense of the complexities of reconstructing the original musical score for the film.

In FilmStruck #1, Jeff Smith discusses “Musical Motifs in Foreign Correspondent.”

Filmstruck #8 features Jeff explaining Chabrol’s use of “Offscreen Sound in La cérémonie.”

In FilmStruck #11, I discuss Fritz Lang’s extraordinary facility with the new sound technology in his first talkie: “Mastering a New Medium—Sound in M.”

Chapter 8 Summary: Style and Film Form

David analyzes narrative patterning and lighting Casablanca in “You must remember this, even though I sort of didn’t.”

In FilmStruck #10, Jeff examines how Fassbender’s style helps accentuate social divisions: “The Stripped-Down Style of Ali Fear Eats the Soul.”

Chapter 9 Film Genres

David tackles a subset of the crime genre in “One last big job: How heist movies tell their stories.”

He also discusses a subset of the thriller genre in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

FilmStruck #9 has David exploring Chaplin’s departures from the conventions of his familiar comedies of the past to get serious in Monsieur Verdoux: “Chaplin’s Comedy of Murders.” He followed up with a blog entry, “MONSIEUR VERDOUX: Lethal Lothario.”

In Filmstruck entry #15, “Genre Play in The Player,” Jeff discusses the conventions of two genres, the crime thriller and movies about Hollywood filmmaking, in Robert Altman’s film. He elaborates on his analysis in his blog entry, “Who got played?”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

I analyse Bill Morrison’s documentary on the history of Dawson City, where a cache of lost silent films was discovered, in “Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction and (sometimes) recovery.”

David takes a close look at Abbas Kiarostami’s experimental final film in “Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES.”

Chapter 11 Film Criticism: Sample Analyses

We blogged from the Venice International Film Festival last year, offering analyses of some of the films we saw. These are much shorter than the ones in Chapter 11, but they show how even a brief report (of the type students might be assigned to write) can go beyond description and quick evaluation.

The first entry deals with the world premieres of The Shape of Water and Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri and is based on single viewings. The second was based on two viewings of Argentine director Lucretia Martel’s marvelous and complex Zama. The third covers films by three major Asian directors: Kore-eda Hirokazu, John Woo, and Takeshi Kitano.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Traditions and Trends

My usual list of the ten best films of 90 years ago deals with great classics from 1927, some famous, some not so much so.

David discusses stylistic conventions and inventions in some rare 1910s American films in “Something familiar, something peculiar, something for everyone: The 1910s tonight.”

I give a rundown on the restoration of a silent Hollywood classic long available only in a truncated version: The Lost World (1925).

In teaching modern Hollywood and especially superhero blockbusters like Thor Ragnarok, my “Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker” might prove useful.

Etc.

If you’re planning to show a film by Damien Chazelle in your class, for whatever chapter, David provides a run-down of his career and comments on his feature films in “New colors to sing: Damien Chazelle on films and filmmaking.” This complements entries from last year on La La Land: “How LA LA LAND is made” and “Singin’ in the sun,” a guest post featuring discussion by Kelley Conway, Eric Dienstfrey, and Amanda McQueen.

Our blog is not just of use for Film Art, of course. It contains a lot about film history that could be useful in teaching with our other textbook. In particular, this past year saw the publication of David’s Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Hollywood Storytelling. His entry “REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD: Out of the past” discusses how it was written, and several entries, recent and older, bear on the book’s arguments. See the category “1940s Hollywood.”

Finally, we don’t deal with Virtual Reality artworks in Film Art, but if you include it in your class or are just interested in the subject, our entry “Venice 2017: Sensory Saturday; or what puts the Virtual in VR” might be of interest. It reports on four VR pieces shown at the Venice International Film Festival, the first major film festival to include VR and award prizes.

Monsieur Verdoux (1947)

Wisconsin Film Festival: Confined to quarters

12 Days (2017).

DB here:

I try to watch any film at two levels. First, I want to engage with it, opening myself up to the experience it offers. Second, I try to think about how the film is made, why it’s made this way, and what those practices and principles can teach me about the possibilities of the medium. That second level of response, not easy to sustain in the thick of projection, comes from my research interests, something spelled out as the “poetics of cinema.”

Most critics, particularly those reviewing films on a daily basis, don’t have the time or inclination to reflect on that second level. I’m lucky to have the leisure to mull over what this or that film can suggest about film in general. When a new release points me toward something I think is intriguing, I’ll go back and watch it again. I saw Zama three times last year, and Dunkirk five times. After three viewings and getting the Blu-ray, I think I’m ready to write about Phantom Thread fairly soon.

Several films at the festival set me thinking. Vanishing Point (1971), which I hadn’t seen in a long time, confirmed my idea in Reinventing Hollywood that 1940s narrative strategies resurfaced in the 1970s. (Whew.) We get a crisis structure motivating a flashback, which itself embeds further flashbacks, everything tricked out with plenty of road rage.

Philippe Garrel’s Lover for a Day (L’Amant d’un jour, 2017) reminded me of how important coincidence is in narrative, particularly the accidental discovery of an important item of narrative information. You know, like coming home just as somebody’s about to commit suicide. Or discovering on your way to the WC that your lover’s having sex with someone else. I began to wonder if the episodic nature of art films, which are built more on routines than on sharply articulated goals, gets away with such handy accidents by suggesting that with so many characters drifting around, they’re bound to intersect occasionally. Realism once more becomes an alibi for artifice.

And I was happy to see American Animals (2018), an amateur-heist movie that uses my friend the flashback in a way that cunningly misleads us. I will say no more, except to refer you to other reflections on caper movies, and to express my hope that Ocean’s 8 will offer some fresh twists too.

All of these films employ what we might call omniscient point of view. The film’s narration shifts us among many characters in many places and times. Herewith, though, some thoughts on two films that tie us down.

Elbow room

The Guilty (2018).

One of cinema’s great powers is its ability to shift locales in the blink of an eye. Unlike proscenium theatre, bound to drawing rooms or perspective streets, a film can carry us from place to place instantly. Novels can do this too, of course, and so can certain theatre traditions, such as Shakespeare’s wooden O. But cinematic crosscutting swiftly from one line of action to another and back again is such a powerful tool that many theorists identified it as part of the inherent language of cinema. The medium seemed wired for camera ubiquity.

At certain periods, though, filmmakers kept to single spaces. Early cinema’s one-shot films locked us to a single view, and in the 1910s, long scenes would play out in salons and parlors. Even after the arrival of crosscutting and other editing strategies, some filmmakers embraced the kammerspiel, or “chamber play” aesthetic popularized in Germany. Lupu Pick’s Sylvester (1924), Dreyer’s Master of the House (1925), and other silent films built drama out of micro-actions in tight spaces. Later Hitchcock took this premise to an extreme in Lifeboat (1944), Rope (1948), Rear Window (1954), and to some extent in Dial M for Murder (1954). Rossellini’s Human Voice (1948) is another instance which, like Rope and Dial M, was based on a play.

The confined-space option reemerges every few years. Put aside Warhol’s psychodramas, so well analyzed by J. J. Murphy in his book The Black Hole of the Camera. Most of Tape (2001), Panic Room (2002), Phone Booth (2002), Locke (2013), and Room (2015) follow this formal option. Two striking films from our festival show that this strategy still holds a fascination for directors. They know that spatial concentration can shape the audience’s experience in unique ways.

In The Guilty director Director Gustav Möller ties us to Asger, a Danish policeman assigned to answering calls on an emergency line. A woman caller tells him she’s been kidnapped, and he tries to locate her while also giving her advice on how to protect herself. In the meantime, he summons police units to track the car she’s in and to investigate the household she’s left behind. In the course of this, we come to understand that he’s grappling with his own problems. He’s about to go before a judge for an action he committed on duty, and his partner is going to testify about it. The whole action takes place in more or less real duration, in eighty-some minutes of one night.

The Slender Thread (1965) similarly includes longish stretches confined to a suicide-hotline agency, but it supplies flashbacks that take us into the caller’s past. Here, we stay in place with Asger. By confining us to what he hears, and what little he sees on his GPS screen, the narration obliges us to make inferences that seem reasonable but that turn out to be invalid. I can’t say more without giving away the twists, but it’s worth mentioning how keeping major action offscreen enables the film to summon up the Big Three: curiosity (about the past), suspense (about the future), and surprise (about our mistaken assumptions).

The Guilty is a sturdy thriller, and it certainly works on its own terms. While restricting us to a character, it doesn’t plunge–as many films would have been tempted to do–into his mind, by means of flashbacks or fantasies. These would have “opened out” the film, but lost the laconic objectivity of the action we get.

The film coaxed me to reflect on how the reliance on the conversational situation allowed for a certain looseness at the level of pictorial style. Once we’re tethered to Asger at his workstation, not a lot hangs on choices about camera placement or shot scale. As long as his face, gestures, and body behavior are apparent, niceties of framing count for less. His reaction can be signaled adequately from many angles. He’s so stone-faced that even a 3/4 view from the rear suffices.

In other words, I can’t see that the situation is submitted to a stylistic pattern that would add another dose of rigor to the filmic texture. The style, I think, works to adjust our attention in the moment, in the manner of what I’ve called “intensified continuity,” rather than building longer arcs of pictorial interest. While the plot constraints are strict, the visual style seems less so.

What would be a way to make pictorial style more active? Well, the obvious cases are Hitchcock’s long takes in Rope and optical point-of-view in Rear Window. (And, I’d suggest, his use of 3D in Dial M.) Dreyer did something similar in The Master of the House, in which editing patterns activate a range of props and bits of setting. Films like these benefit from including several characters onscreen, providing details of setting and building up spatial “rules” that channel our vision. Or think of Kiarostami’s auto trips (I almost said “car-merspiel”), which limit camera setups pretty stringently. Ditto Panahi’s ways of stretching the notion of “house arrest” in This Is Not a Film (2011), Closed Curtain (2013), and Taxi (2015)–films that tantalize us with the possibility of glimpsing the world outside.

Möller chose, with good reason, to rivet our attention on two basic elements: the calls and Asger’s responses. The cop’s interactions with others in the office are minimal, and there’s almost no play with props or setting, apart from a moment when Asger decisively snaps down the windowblinds. Our attachment breaks off only at the end, at the conventional moment when the protagonist turns from the camera and walks away.

The tight concentration enhances both plot action and character revelation, and we’re obliged to listen more closely than we do in most movies. Along the way, blinks and eye-shifts and finger-tapping become major events. Still, The Guilty reminded me that every choice cuts off others, forces new choices, sets up constraints–and new opportunities. Film art is full of trade-offs.

12 Day wonder

12 Days (2017).

A more “dialectical” approach to confined space is on display in Raymond Depardon’s documentary 12 Days (2017), probably the most emotionally wrenching film I saw at our fest. The situation is a similar to that in his Délits flagrants (1994), which recorded police interrogations of suspects. The official procedure captured here is a hearing, mandated within twelve days of a patient’s being involuntarily committed to a psychiatric hospital. A judge reviews the case to determine whether the patient should be set free.

Sessions with ten patients take us along a spectrum of disturbance, from a woman believing herself persecuted in her office to a man whose inner voices commanded him to stab a stranger. The last petitioner, a woman sufficiently aware of her illness to admit that she can’t care for her baby, makes a lucid case for being allowed to visit the child occasionally.

All these encounters are shot in a simple but strict fashion. In three reverse-shot setups, we see the petitioner, the judge, and a wider view of the petitioner and the lawyer who states the case.

This neutral approach, far less free-ranging and nerve-wracking than the shots in The Guilty, doesn’t try to amp up the suspense with cut-ins or zooms or pans. It throws all the emphasis on the interchange. Call it Premingerian, if you must.

Sandwiched in between these inquiries are shots of the hospital itself. We’re still confined, in that we never leave the grounds, but these let us breathe a little. Sometimes these interludes are simply quiet tracking shots down empty corridors; sometimes we hear wails and cries behind locked doors; sometimes we see the patients in a rest area, smoking or pacing or simply staring.

By respectfully observing the surroundings, Depardon lets us into a bit of the texture of the patients’ lives and makes us understand that this hospital, while apparently not very oppressive, is still far away from freedom.

Confronting 12 Days we on the outside are forced to balance compassion with prudence. Should a calm, polite man who believes he beatified his father by killing him be allowed free access to our world? Most of the patients we see are remanded for further treatment, but one leaves the judge ambivalent, to the point that we aren’t told of the final decision. We’re left to reflect that to become wholly human, we must confront madness in our midst. As the opening quotation from Foucault has it: “The path from man to true man passes through the madman.”

Thanks as usual to our Wisconsin Film Festival programmers: Ben Reiser, Jim Healy, Mike King, Matt St John, and Ella Quainton. Thanks as well to Tim Hunter for giving us access to Vanishing Point. In all, it was a swell event. See you there next year?

12 Days reminded me that one of the less-known examples of early Direct Cinema was Mario Rispoli’s Regard sur la folie (1962), which presents afflicted patients and their caregivers with a surprising lack of sensationalism.

We’ve written a fair amount about site-specific narratives. I discuss the crystallization of the trend in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, and I consider its recent revival in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. On the blog, we’ve discussed Panic Room, Dial M for Murder, The Master of the House, This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, and the Kammerspielfilm. And on coincidence, you can drop by here.

12 Days.

Bill Morrison’s lyrical tale of loss, destruction, and (sometimes) recovery

Kristin here:

Many readers of this blog have heard of the Dawson City Film Find (hereafter DCFF), as it is called in Bill Morrison’s extraordinary documentary, Dawson City: Frozen Time. How in 1978 work on a construction site in Dawson City, Canada, led to the discovery of hundreds of reels of nitrate films packed into a swimming pool in 1929, covered over, and forgotten. How these reels turned out to be from silent films, mostly from the 1910s, many of them previously thought entirely lost.

Few will know the story in the detail with Morrison provides, nor will they know the rich historical context that he provides for the discovery and recovery of the reels. His film is not, however, simply a presentation of the DCFF. It’s about growth, loss, recovery, and destruction in several areas, all circling around Dawson City as their hub. The subtitle “Frozen Time” is a bit misleading. The reels of nitrate sealed away in the permafrost were no doubt frozen, and the temporal fictional and newsreel images they contained were lost for decades.

Morrison, however, weaves information about a variety of other subjects together in a way that makes the passage of time palpable for us. We see its effects on people and places and discover the odd, fortuitous connections among them in a dizzying fashion.

A complex film like this deserves an extended commentary, which I offer below. There are spoilers galore in it, and I would suggest seeing the film before reading this. It should appeal to anyone interested in early cinema, in North American history, and in documentaries in general. Kino Lorber has recently released Dawson City: Frozen Time on Blu-ray, with extras including eight films from the DCFF.

Easing into the past

The films-in-a-swimming-pool hook is what Morrison uses to lure us into his larger historical weave. He begins with a hint of the recovered footage, showing a baseball game which will later be revealed as the scandalous 1919 World Series where White Sox players were bribed to throw the deciding game. Then we see briefly see Morrison himself being interviewed by a talk-show host, followed by a lady in 1890s costume enthusiastically introducing a premiere screening of some of the restored films for an audience in the Palace Grand. That theatere is a modern reconstruction of the first theater built in Dawson City, used for live drama, opera, eventually films, and other forms of entertainment.

We move by stages back into history. Fifteen months before the premiere the discovery was made: a man running a back hoe turned up reels and coils of film. We meet the protagonists of the film-discovery portion of Morrison’s tale: Michael Gates, curator of Collections at Parks Canada from 1977 to 1996, and Kathy Jones-Gates, Director of the Dawson Museum from 1974 to 1986. She was Kathy Jones at the time of the discovery; this tale even has a romance, since the pair married after working together on the recovery of the buried reels. The couple describe the initial find, over still photos of mud-covered reels taken with Jones’s camera (above).

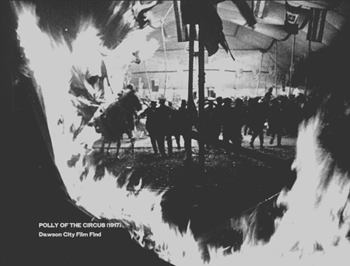

Morrison now takes us further back, to demonstrations of how nitrate film was made (with extracts from a 1937 film optimistically titled Romance of Celluloid) and how it is prone to catch fire and burn fiercely. The well-known 1897 Charity Bazaar disaster in Paris is cited, while film of a burning tent and fleeing spectators is shown. No visual record survives of the Charity Bazaar disaster, not even photographs. News accounts used engravings as illustrations. The burning tent footage is from a film released twenty years later, Polly of the Circus (1917), one of the main lost films recovered in the DCFF.

Morrison does not hide this source but superimposes a caption giving the film’s title, date, and source. This is the first time he draws upon DCFF images to evocatively represent real historical events. Later in Dawson City, the mention of an actual person, such as Gates, sending a letter will be accompanied by a montage of letter-reading moments culled from DCFF films. It’s a clever way to add a little humor and to show off a wide variety of the titles without dwelling on long clips from any one film.

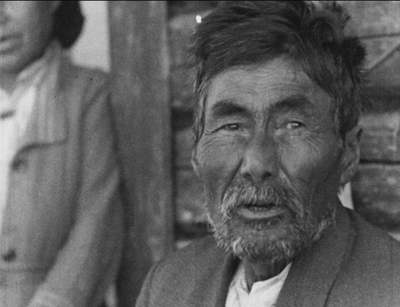

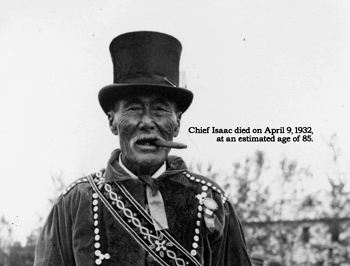

Having established the destructibility and danger of nitrate, Morrison flashes back to the earliest period portrayed in the film. Epic photographs show forested landscape. The narration, done with captions rather than voiceover, informs us that for millennia the area where the Klondike River flows into the Yukon has been the hunting grounds for one of the First Nations, the “native Hän-speaking people.” (The footage is from City of Gold, the famous 1957 Canadian documentary about Dawson City, which will become more important later in Morrison’s film.) A photo introduces Chief Isaac, leader of one subgroup of the Hän.

Nothing is said at this point, but the fate of these hunting grounds initiates one of the major threads recurring through the film, that of ecological destruction.

The third major thread is the history of Dawson City itself, which is as fascinating as the story of the buried films. In late 1896 or early 1897 one Joseph Ladue claimed 160 acres as a town site, where he sold lumber and lots to prospectors. By the summer of 1897 there were 3500 residents, and Morrison uses population figures to trace the wide swings in the town’s fortunes over the decades.

At this point the Northwest Mounted Police relocated the Häns’ village five miles downriver, and their fishing and hunting grounds were destroyed by mining.

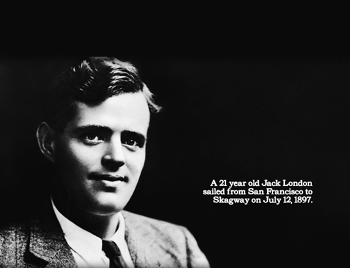

During the descriptions and facts about the huge amounts of gold coming out of the area, Morrison introduces other motifs and threads. He mentions that Jack London was among the prospectors. He was the first of several writers and theater figures who were in the Yukon, often during these early years. Most of them resurface late in the film later on, turning out to have surprising connections with the history of the cinema and each other.

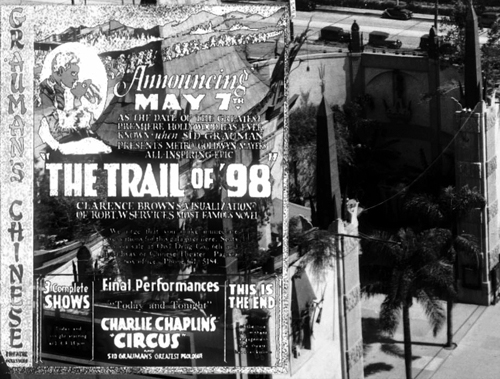

Famous entrepreneurs of later years got their starts here. Sid Grauman was a newspaper boy who eventually went on to build a theater chain, including the Egyptian and Grauman’s Chinese in Los Angeles. Ted Richard, who staged boxing matches in the Monte Carlo theater, later founded the New York Rangers and rebuilt Madison Square Garden. Alex Pantages started as a bartender, rebuilt Dawson City’s Orpheum theater after it burned to the ground in 1899 and showed traveling programs of early movies. He became one of the first major film tycoons, building a string of 70 theaters in North America.

The Gold Rush frozen in time

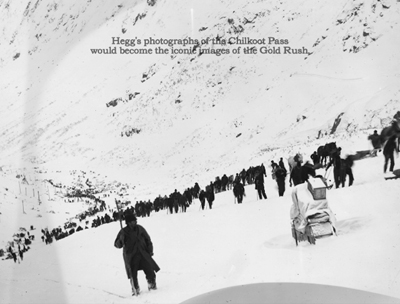

One of the revelations of Dawson City is the work of photographer Eric Hegg, who traveled to the Yukon alongside with the hordes of hopeful prospectors. He, however, worked as a photographer, and shot thousands of images that became, as Morrison’s caption says, “the iconic images of the Gold Rush.” The one above shows the arduous and crowded journey up over the notorious Chilkoot Pass. Chaplin later staged a remarkably similar scene for The Gold Rush (1925), though whether he could have seen Hegg’s images is unclear.

By the summer of 1898, the population of Dawson City was around 40,000, and the richest claims were all taken. Businesses were set up to cater to the prospectors, including Hegg’s photographic studio. Saloons, casinos, theaters, as well as more practical boat-builders and banks sprang up. Of the two initial banks that opened branches, the Canadian Bank of Commerce is the more important to Morrison’s story, since it eventually acted as the Dawson City agent for distributors sending films to town.

The first boom ended in the spring of 1900, after the announcement of a gold strike in Nome. Three-quarters of Dawson City’s population left, including Hegg, who left his collection of glass negatives with his partner, Ed Larss. He opened a new studio in Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush.

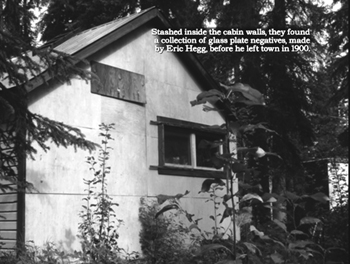

After his departure, Hegg disappears from Dawson City for quite some time. His work there, however, was also fortuitously rescued from oblivion. Twenty minutes from the end, we are introduced to Irene Caley and Will Crayford, who married in 1947 and decided to move a cabin from Dawson City to Rock Creek. Inside the walls they found hundreds of Hegg’s glass negatives. How they got there is unknown. Coincidentally, Hegg died in 1947, presumably unaware of the recovery of his early negatives.

The newlyweds proposed to strip the emulsion off the plates and use them to build a greenhouse. Luckily a local shopkeeper recognized their nature and gave the couple plain plates in exchange for the 93 glass ones, as well as 96 nitrate negatives. He donated the collection to the National Museum of Man in Ottawa. Arguably this rescue is as significant as the DCFF, especially given that Hegg’s photographs mostly survived in beautiful condition and constitute the best record of the Gold Rush’s first stage.

In 1949 a book of Hegg’s photographs, edited by Edith Anderson Bccker, was published as Klondike ’98.

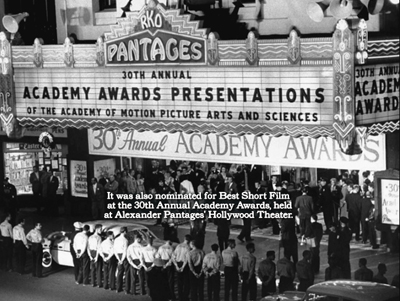

Subsequently documentary film director and producer Colin Low saw the plates in Ottawa and was inspired to make City of Gold (1957), co-directed by Wolf Koenig. City of Gold, which drew extensively on Hegg’s images, was nominated for an Oscar for Best Short Film. The awards ceremony took place at the Pantages Theater in Los Angeles, built and owned by the same Alexander Pantages who launched his theatrical career in Dawson City. It would be nice to think that whoever attended that ceremony representing City of Gold saw the connection.

In 1900, Hegg moved to Skagway and continued to document the Gold Rush. His post-Dawson City photographs also survive. The University of Washington’s collection contains over 2100. Its library offers a short biography and a generous sampling of those photographs here.

Weaving the threads together

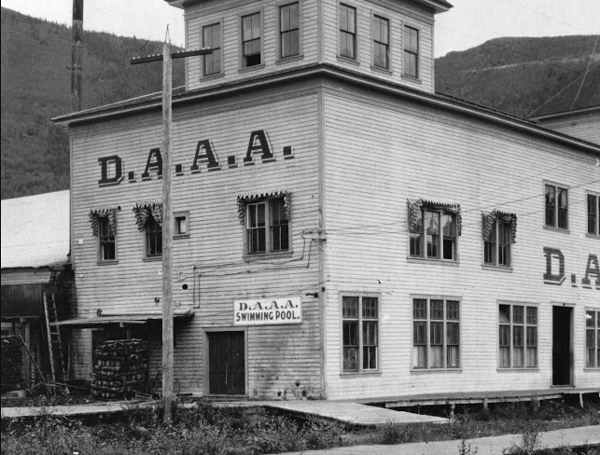

Dawson City’s second boom was less spectacular but more ominous. The White Pass Railroad made Dawson City more accessible, and heavier equipment was brought in: giant hoses to break up the ground, sluices to convey the ore to a central locale, and so. Miners brought their families to live in Dawson City, with the population steadying at 9000. Various institutions, including banks, the Carnegie Library (above), and, in 1902, the huge Dawson Amateur Athletic Assocation (DAAA) building was built, with an auditorium, billiards room, bowling alley, skating rink, and swimming pool (top). I can’t summarize the whole film, but by this point Morrison has introduced enough people and places to start connecting them up in unexpected ways.

One such thread meanders like this. The celebrity motif returns at about this point, with Marjorie Rambeau (later to have a career as a character actress in movies from 1917 to 1957) performing in Dawson City with a traveling theatrical trouple. Rambeau is not significant here, but Fatty Arbuckle was also in the cast. This information is accompanied by a frame from Fatty’s Day Off (1913), a film discovered in the DCFF.

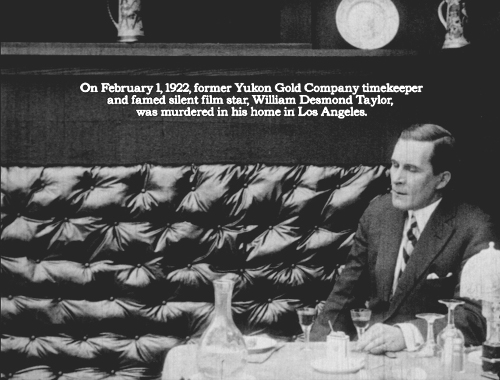

Shortly after this, we hear of two further celebrities-to-be who were in Dawson City. In 1908, poet Robert Service arrives to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce, and the following year he writes his first and best-known novel, The Trail of ’98 (1909), about the Gold Rush. From 1908 to 1912, William Desmond Taylor works as a timekeeper on a large gold-mining dredge belonging to the Yukon Gold Company, founded by Daniel and Soloman Guggenheim in 1907. These dredges handled most of the mining, throwing many out of work and causing Dawson City’s population to shrink to 3000. Huge dredges would continue to grind down the land for decades.

In 1912, Taylor left for Hollywood, where he enjoyed a short but prolific career as an actor and director, before, as Morrison foreshadows, his untimely death.

These people disappear for a time, and we learn that in 1911 the auditorium of the DAAA was turned into a movie house, the DAAA Family Theater. Other theaters in town went over to showing films. Morrison conveys this via an amusing montage of shots of people in cinema and theatrical audiences, all from DCFF films. He also provides a quick summary of disastrous nitrate fires during the early 1910s.

There follows a long interlude of coverage of the suppression of laborers and leftists during this period, in part to show off some of the newsreel footage preserved in the DAAA swimming pool. These include the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, the “Silent Parade” protesting violence against African-Americans in 1917, and the World Series scandal of 1919.This somewhat tangential though interesting foray into politics also serves to bring us forward nearly a decade.

The Solax studio fire, which also happened in 1919, provides a rather wobbly transition back to film and Dawson City as the end point of a film distribution line. The population has sunk to 1000 by this point. Since the films shown in the town during this decade were not shipped back to the distributor, many of them were stored in the basement of the Carnegie Library and continued to be through the 1920s.

A long, effective montage of shots from various DCFF films follows, beginning with people listening through doors and going through them, so that we get the impression of a giant house with dozens of people sneaking around. This is followed by shots of men attempting to embrace women and being repulsed.

The last of these is from The Kiss (1914), starring William Desmond Taylor. A caption announces his murder in 1922.

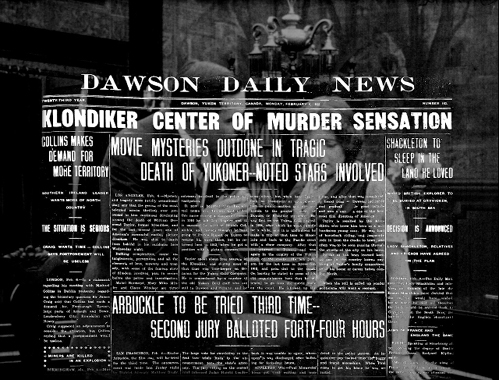

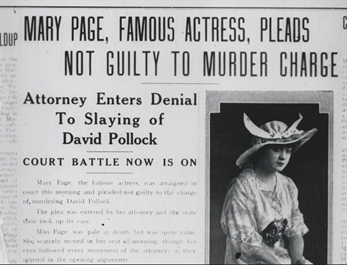

A Dawson City newspaper page announcing the murder and calling Taylor a “Klondiker” and a “Yukoner” is superimposed over another image from The Kiss. Coincidentally, just below this story is one about Arbuckle’s second murder trial ending in a hung jury. The second Taylor headline points out: “Noted Stars Involved.” One of these was Mary Miles Minter, and Morrison shows her in a film, The Little Clown (1921), from the DCFF. Minter had acted in films directed by Taylor, though this is, alas, not one of them. It was however, discovered among the DCFF films. Not one to quit there, Morrison cuts to a shot from another DCFF film, The Strange Case of Mary Page (1916), which has a plot that resembles Taylor’s case.

That two Hollywood directors should have been linked to murder cases, one as victim, one as alleged perpetrator (Arbuckle was never convicted), was certainly a gift to a director keen to stitch as many elements of his film together as possible through associations rather than straightforward historical causes.

Other connections are less elaborate. At the point where the story of Dawson City has reached the late 1920s, The Trail of ’98 (1928), an adaptation of the Robert Service novel mentioned above, is shown via a superimposed poster to be screening at Grauman’s Chinese, another chance confluence of two people who could not have crossed paths in the Yukon, since Grauman left there in 1900.

The burial

All this material has brought us to the point when the accumulating films in the library basement were transferred to the DAAA swimming pool. By 1928 Dawson City had developed a “modest season tourist industry.” Chief Isaac, whom we met early on, had become mayor of Moosehide (above). And Clifford Thomas, the man responsible for putting the film reels in the swimming pool, moved to Dawson City to work at the Canadian Bank of Commerce. He also became the treasurer of the Dawson Amateur Hockey League, which played on the ice rink installed annually over the swimming pool.

In 1929 the library storage had reached capacity, and when Thomson inquired of the studios what he should do with the films, he was instructed to destroy them. At about the time, it was decided to fill in the pool so as to allow for a the skating rink to get rid of a broad bulge caused by the pool’s cover. Thomson made the decision to use the reels as fill in this conversion. Numerous other reels were burned or thrown into the Yukon River–a standard way of disposing of trash.

Morrison could have skipped back to the recovery of the films roughly fifty years later, but instead he continues the Dawson City story. First, he poetically indicates the long decades the reels spent sealed underground with a montage of women asleep, all drawn from DCFF films. The talkies finally reach Dawson City, and more silent reels are dumped or burnt. Chief Isaac dies in 1932.

Parades continue to celebrate the Gold Rush heritage, as recorded by George Black, an avid local amateur cinematographer who recorded several events shown in Dawson City. The one below took place in 1941.

By 1950, the population of Dawson City dropped under 900 people. The last theater was torn down in 1961, though the replica of the Palace Grand went up as a multi-purpose facility in 1962.

On November 15, 1966, the Yukon Consolidated Gold Corporation closed down its last dredge. A lengthy drone shot flies high over the tortuous, unnatural landscape that resulted from many decades of grinding down and spewing out the land (bottom). The ecological thread has not been emphasized through most of the film, but it comes to a devastating conclusion.

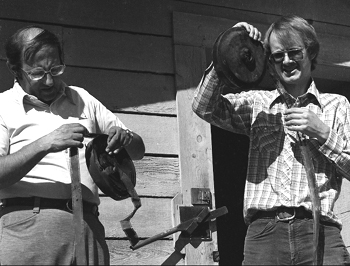

Morrison reaches the discovery of the reels in 1978, and Gates and Jones-Gates resume their story. They contact Sam Kula, Director of Audiovisual Archives, 1973-1989 at the National Archives of Canada. Kula comes to Dawson City, and he (left) and Gates (right) investigate the sodden reels of film.

Kula initially suggested donating the films to the local museum and contacted Kathy Jones. She helped dig up the films, which turned out to be far more numerous and buried far more deeply than they imagined. A newspaper item about the find led to a letter from Clifford Thomson. His explanation of how he had arranged for the films to be put in the swimming pool solved that mystery and provides us with our basic knowledge of the origins of the reels.

The rest of the film’s tale of the reels’ discovery follows how the three rescuers tried to ship the thems to the National Archives of Canada, with several truck, bus, and air services refusing to deal with nitrate film. In November of 1978 a Canadian Air Force plane delivered 506 reels to the Archives.

Morrison ends with a series of shots from various DCFF films with heavy deterioration. The thread of nitrate’s flammability and the recounting of numerous nitrate fires finds its quiet ending in the film’s lengthy final shot. A female dancer performs a modern dance that apparently expresses anguish. Blank white flashes flicker across the frame, suggesting that the dancer is being enveloped by the flames generated by nitrate film.

It is a fitting ending to a film that blends fascinating information and poetic associations in equal measures.

Some caveats

Despite my considerable admiration for Dawson City: Frozen Time, I have to take issue with some of the descriptions in this last part of the film. The narration does not point out that most of the films recovered were incomplete–not surprisingly, given how many reels were burned or otherwise destroyed. A film historian would assume that. A casual viewer would not. Similarly, there is an explicit statement that “every other copy” of these films had been lost to fire and decay. Some of these films, however, survived elsewhere, and sometimes in better copies.

The reception of the film has, through no fault of Morrison, distorted the significance of the DCFF considerably further. This evidently started with a extensive article in Vanity Fair that dubbed the DCFF “The King Tut’s Tomb of Silent-Era Cinema.” Numerous reviewers picked up this idea and repeated it, as when Kenneth Turan began his review, “It’s been called the King Tut’s Tomb of silent cinema, a celluloid find at one of the world’s far corners that dazzled the film universe.”

I cannot think of a more inapt comparison. Tutankhamun’s tomb is one of only two largely undisturbed royal tombs from the entire three-thousand-year history of ancient Egypt, and it is far and away the more important of the two. Despite the tomb’s small size in comparison with others in the Valley of the Kings, an extraordinary number of intact royal grave goods came from it–about 5000 of them (a small sample shown above). Indeed, most of what we know about ancient Egyptian royal grave goods is derived from those pieces. Tutankhamun’s tomb is, as far as we now know, unique.

In contrast, there have been many hundreds of discoveries of original silent films. One of the most notable is the Desmet collection in the Netherlands, which contained over 900 films, most of them complete and in excellent condition. Other such discoveries have ranged from single prints to large collections. Those who have discovered and restored these films are still building the international archival holdings of silent cinema. The Dawson City find is simply one important contribution to this extensive and ongoing effort.

Sam Kula himself wrote, “No-one familiar with the considerable resources now accessible through the work of film archives throughout the world would seriously argue that the Dawson Collection, or any one cache of early film, will lead to a wholesale re-write of the histories.”

The story continued

Morrison essentially ends his account when the films leave Dawson City, which is quite understandable. But the viewer might ask what happened next. There is little attention paid to the lengthy, complex procedures necessary to rescue the films from the effects of their long burial and to transfer their images onto modern negatives.

The Blu-ray release contains a nine-minute supplement, Dawson City: Postscript, which does trace some of the subsequent history of the rescued reels. We see the washing of the films in the Canadian facility, as well as the storage facilities in which the original films were stored once they had been duplicated. In the US, the Library of Congress’ 388 reels are now kept at the Packard Campus in Culpeper, Virginia, which David visited and blogged about earlier this year. Morrison maintains his history of Dawson City as well, noting that in the summer of 1979 the town suffered a disastrous flood and that the premiere of some of the restored films took place shortly after that, on September 1.

At first glance, the Dawson find seems to have been handled in a casual way, with local administrators who were not film archivists digging up reels with shovels and handling them in a way that today would seem reckless. Some have assumed that considerable unnecessary damage was done to the films after their discovery. Yet no written account of the whole affair has yet been published.

I asked our friend Paolo Cherchi Usai, Senior Curator of the Moving Image Department of the George Eastman Museum, for his opinion. He kindly gave me his account of the rescue process, which suggests that the original participants in Dawson City did the best they could under extremely challenging circumstances.

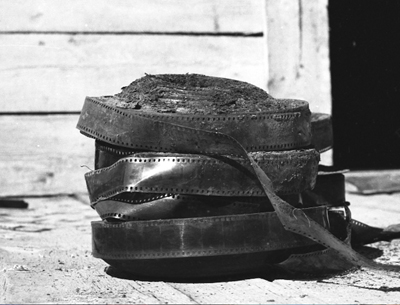

As Paolo wrote in introducing his description, “Please note that what I know is just a matter of oral history — things I heard from the protagonists and witnesses of the events, several years ago. Also, I have not yet seen Bill Morrison’s film.” Others may be able to correct or expand upon some of what Paolo has written. Still, it provides a very informative and useful summary of the rescue process. (I have identified the people mentioned below in brackets. The undated image of a silent-era drying drum is the only image in this entry that is not from Dawson City: Frozen Time.)

In my opinion, the rescue of the Dawson City was a miracle of improvisation and initiative achieved under extremely difficult and often adverse circumstances (see below). In all fairness, I can’t call it a disaster (I can think of other occurrences in my field where that term could rightfully apply). In hindsight, it is all too easy to point out the mistakes made in the process; back in 1978, archival practices were less sophisticated than they are now.

The comparison with Tutankhamen’s tomb is indeed excessive in regard to the aesthetic importance of the films; there is no exaggeration, however, in pointing out the extraordinary circumstances surrounding the discovery, and the steps taken in a very short period of time. You don’t find silent films in a frozen swimming pool that often. When you do, the historical value of the artifacts is not an issue. You want to save all the objects, and then find out their worth. That’s the main reason for the mystique surrounding the discovery; that’s also why I heard about it as soon as I started studying silent film history and film preservation.

It must be pointed out at the outset that the film reels found in the layer right under the permafrost that covered the swimming pool were already decomposed. Nothing could be done to save those prints. It is my understanding that preliminary identification work was undertaken at Dawson City, and that such work was implemented in a cold area. It may be argued that there was no particular reason why this work had to be done there instead than later in Ottawa, but that’s what happened. The late Sam Kula, one of the protagonists (together with Bill O’Farrell [Head of Film Preservation, 1975-2002, National Archives of Canada] and Paul Spehr [former Secretary for the Motion Picture Section of the Library of Congress and Assistant Chief of the Motion Picture Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division of the Library of Congress], among others) of this story, may have been able to explain this.

The reels gradually thawed in at least three stages, during their transfer to a) an air-force base near Dawson City; b) the National Archives in Ottawa; c) the Library of Congress. The thawing could perhaps have been minimized (if not avoided altogether) if the material had been processed in a refrigerated area from beginning to end. This didn’t happen. The nitrate unit at the National Archives of Canada had been shut down to make room for operations on safety materials, and no special precaution could apparently be taken while dividing the collection in two main groups: the Canadian newsreels to be kept at the National Archives, and the American films to be sent to the Library of Congress.

Bureaucracy was the nemesis of the Dawson City rescue project. The only way Bill O’Farrell could bypass it was for him to personally transport the reels of American films from Canada to the US by car, in a large station wagon, from Ottawa to Suitland, Maryland. His heroic feat — perhaps the most important of his career — would have hardly been possible today. He had no choice; following the usual protocol would have taken months, and the emulsion on the prints would have melted completely. Paul Spehr did his part by having the films accepted into the collection in record time, without following the standard acquisition procedures at the LoC. O’Farrell had alerted Spehr that “there is water in the cans” — this is what Spehr heard on the phone, and he expected this to be the case when the material arrived. It’s not that the reels were drenched in a pool of water in each can; but there was water. The prints had thawed.

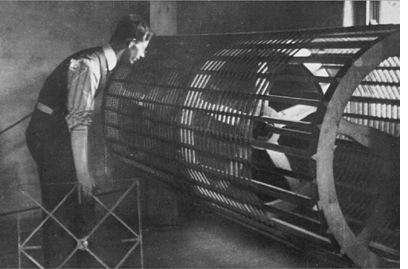

In that situation, it was deemed necessary to do something about that water. The technical staff at LoC designed and built  a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

a drying drum, similar to those used in film laboratories during the silent era. Because of their size, each reel had to be unwound and cut into sections of approximately 300 feet each. The reels were dried that way. They were unwound while very wet on the edges of the reels, and the emulsion inevitably peeled off from the left and right margins of the frame; hence the distinctive look of the Dawson City films we can see today in reproduced form. I think the very same method for drying the films was applied in Ottawa to the Canadian newsreels.

To reiterate the point, the whole story has always been described to me as an emergency rescue performed at breakneck speed, a chain of events where careful advance planning could not be part of the picture. The only way to avoid the partial loss of the emulsion would have been to undertake the entire process in a much colder working area. By the time the reels reached Dayton, however, it would have already been too late to apply such a solution, even if a low-temperature processing area had been available. All that could be done at LoC was to “stabilize” the material long enough for it to go through the printers for duplication.

So that’s that. I hasten to add that my recollections raise a number of questions to which I have no answer.

Our thanks to Paolo for filling in so much of the rest of the story of the Dawson City Film Find.

Thanks to Jonathan Hertzberg of Kino Lorber for his assistance.

The Sam Kula quotation comes from his account of the DCFF rescue, “Rescued from the Permafrost: The Dawson Collection of Motion Pictures,” which can be found on Archivaria: The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archvists #8 (Summer 1979), reprinted from American Film (July 1979).

A brief description of the “Public Archives of Canada/Dawson City Collection” is on the Library of Congress “Motion Pictures in the Library of Congress” page.