Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Film-industry pros share secrets in Vancouver

Kristin here:

Even while tempting us with many, many films, the Vancouver International Film Festival runs an event that could all too easily lure us away from viewing and into the world of film-industry gurus: the Film and Television Forum. Its website describes it as “four days of professional development for senior and emerging professionals, from financing to production, to marketing and distribution, to storytelling and engagement.”

In an ideal world, we would attend all of the sessions, but they run concurrently with as many as eight films showing elsewhere. Two talks were particularly appealing, though, given our interest in the  practice of making films within the mainstream American industry. I slipped away to hear master-classes by Terry Rossio (screenwriter for all of the Pirates of the Caribbean films) and Walter Murch (editor of Particle Fever, shown at the festival, and sound designer on many films, including Apocalypse Now).

practice of making films within the mainstream American industry. I slipped away to hear master-classes by Terry Rossio (screenwriter for all of the Pirates of the Caribbean films) and Walter Murch (editor of Particle Fever, shown at the festival, and sound designer on many films, including Apocalypse Now).

Terry Rossio

Rossio’s modest title was “Revisions,” though his discussion ranged far beyond advice on how to rewrite a script. He immediately won over the audience, clearly many of them professional or aspiring screenwriters, by passing around a flash-drive and inviting anyone with a script-in-progress on their laptop to put some pages on it. He would end the session by making some impromptu revisions of those pages.

I’m not secretly working on a screenplay or even aspiring to write one, but if I were, I think I would have gleaned some valuable tips from Rossio’s talk.

Most panels and seminars tend to be too general, he said. They “focus on the business side, tell personal anecdotes,” and so on. He feels that it is probably impossible to teach screenwriting: “No, the better question is, can writing be learned?” Yes, but people must teach themselves.

Writing and revising

To Rossio, one crucial thing to learn is that finishing a story is not the end. One should have both doubt and faith: doubt that a story or scene is good enough, and faith that it can be better.

Revision, according to Rossi, is “talent reapplied.” One may have a limited amount of talent for writing, but it can be stretched by reapplying it over and over during the revision process.

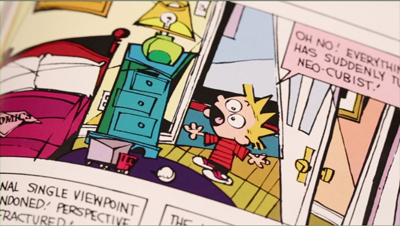

Rossio is a big advocate of succinctly creating a strong visual sense in each scene. Even on Rossio’s desktop he comes up with a distinctive icon for each folder (see top): a Rubik’s cube for “Screenwriting,” a little gramophone for “Music,” and so on.

For Rossio, each scene should consist of:

- Opening image

- Key moment (character revelations, reversals, etc.)

- Throw (i.e., the setup for the next scene)

Apart from visual imagery, writing should be situation-based: “Every scene you write must be an obvious situation.” A screenplay is a string of situations, which creates a compelling interest in the scene. His example was two people discussing an important deal in a car on the way to a meeting. The dialogue might become boring because of the static setting, but the writer could make them experience car trouble and have their discussion outside the car while worrying whether they will make it to the meeting: “The easiest way to create interest is through some sort of dilemma.”

One important technique of revision is what Rossio calls “performance dialogue.” Writers tend to compose speeches in full, grammatical sentences, but that doesn’t sound natural in spoken dialogue. Rossio takes these complete sentences and starts to eliminate words: “Less words allows for performance the actor will be performing in between the syllables.” He adds, “If you give an actor a very long line, they can’t manipulate that into an emotion. But a shorter line allows them to express the subtext or nuance of what’s going on.”

This advice led to a question from the audience about how a writer can convey to the director and actors what he or she intended the nuances of a scene to be. Rossio suggested three possibilities:

- Become a director. The director is the one who puts things on the screen. The writer makes suggestions about what to put on the screen.

- Negotiate having the power to be on set during shooting.

- Annotate the screenplay.

The third point caused quite a bit of interest and is an unusual approach that Rossio himself has recently adopted. He writes a normal script, fairly compact and easy to read. But he includes endnote numbers that refer to a separate document, a list of annotations. These might be something like an indication that a certain moment in the film is a reference to the opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark or suggestions about special camera angles. Rossio has not used this tactic often enough to gauge whether directors in general would appreciate it, but he did have a good response to the first annotated script he provided.

Rossio dislikes all the screenwriting software on the market, but he showed off a system that he devised himself. The screen below shows the list of scenes for his current project, Masters of the Universe. Each scene is identified by a single word, such as “Vengeance” or “Snake.” The ones that are finished are highlighted in color. (I don’t believe Rossio mentioned the difference between the purple and the yellow highlighting.) The scenes can be switched in order with their labels automatically re-numbered.

One advantage of this system is that the author opens only one scene rather than the whole script. Dealing with something that may be about four pages long is less overwhelming. Rossio also finds that his system facilitates sharing drafts of scenes with a collaborator.

Tips for pitching

In keeping with his emphasis on the visual aspects of a screenplay, Rossio recommends that writers make up a brief pre-viz that captures the essence of the script’s premise. Increasingly, software is becoming available that would allow technically adept writers to create demo clips on their own. For writers unable to do this, Rossio suggests that in a highly competitive market, they should get an effects house to do the job for them. These days even some directors are using this approach in trying to get a job.

Rossio was asked a question about pitching to get a job revising an existing script. He had four suggestions.

First, read the script that is to be revised. Surprisingly, not all writers do that. If it’s based on a literary property, read that, too. A lot of writers just wing such pitch meetings.

Second, take along a presentation board. It can be used for breaking down the script or drawing images.

Third, write a recap of the script as it exists and be ready to discuss specific possible changes.

Fourth, go to the trouble of having two or three specific images ready to show. If the VIPs like the images, they can get access to them only by hiring the writer.

I think if I were a scriptwriter, aspiring or otherwise, I would consider that Rossio packed a lot of useful information into his 75-minute presentation. He also chose two of the script excerpts submitted by audience members and gave their authors some quick and helpful suggestions for revisions.

Walter Murch

As far as I could tell, Murch’s talk had no title, but the concept he threw out early on was “fungibility,” one meaning of which is being capable of changing easily. The example he gave was a caterpillar changing into a butterfly. Murch was referring to the digital revolution in film editing. This was not so much a how-to talk as an attempt to demonstrate the dramatic changes that have come about as a result of rapidly changing technologies.

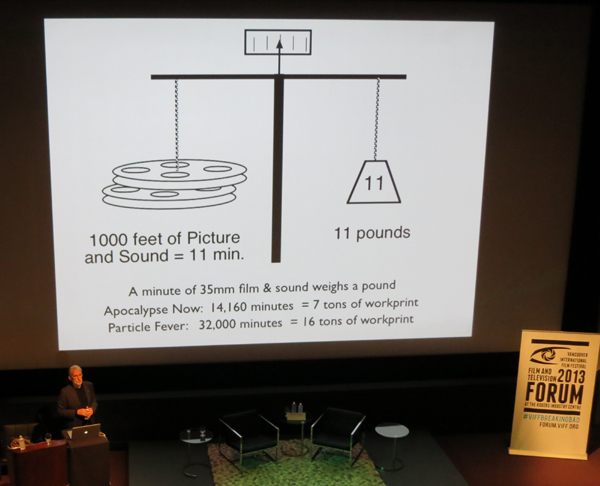

Murch showed a photo of himself struggling with 35mm film strips in editing Apocalypse Now in the 1970s (above). Now, of course, there would be no such physical sorting and splicing. He then pointed out the sheer weight of film, which has been entirely eliminated:

As the graphic shows, a single 1000-foot reel of 35mm film weighs 11 pounds. The strips of Apocalypse Now in the photo above were part of workprint material totaling 7 tons. If Murch’s latest film, Particle Fever, had been edited on 35mm, he would have had to deal with far more, 16 tons of film. It simply would have been impossible to edit such a quantity of footage. (Would a hard-drive with a complete feature film on it weight measurably more than a blank one? he wondered.)

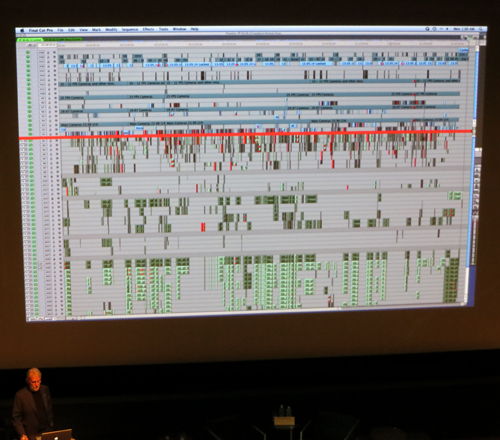

For Particle Fever, Murch used Final Cut Pro 7–an announcement that led to scattered applause from the audience. Like Murch, users of that program are loyal to it, but as he pointed out, a 32-bit program simply can’t keep up with modern demands for memory. While editing, he kept running into situations where there was no memory left, and he had to use elaborate and time-consuming methods to free up storage space. (The film ended up with 18 terabytes of material stored.) On his current project, Tomorrowland, he is using a 64-bit Avid program and has had no problem running out of memory.

(Tomorrowland is being made here in Vancouver, which is presumably why we had the privilege of Murch’s participation in the forum.)

Murch showed a timeline graphic for Particle Fever, with multiple image track, dialogue tracks, effects tracks, musical tracks, and so on. Each small horizontal line represents a separate track:

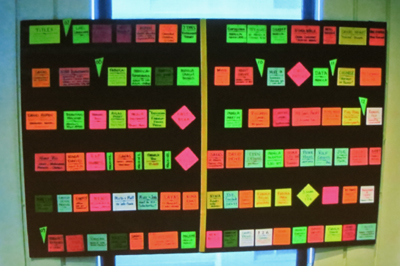

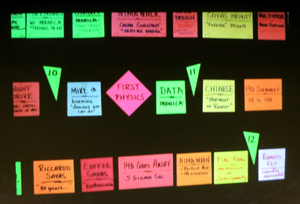

Even while working on this level of complex technology, however, Murch sticks to simple methods for some of his planning. He creates a “scene board” using cards coded with colors, sizes, and shapes . The little green triangles create a chronology, giving the years covered by each set of scenes:

As with Rossio’s system of storing his scenes in a way that allows him to change their order, Murch can move the cards around if the structure of the film changes. Murch put it this way: “I would suggest reversion to kindergarten.”

He also showed some photos of his workspaces for various projects. One was intriguing for indicating how important perspective is for editing. One workroom contained a 50-inch monitor for playing back scenes as he edits them. (See bottom.) Note the little white figures of a man and a woman at the bottom corners of the screen. Murch wanted to keep scale in mind, and the figures represent normal-sized people at the proportionate size they would appear if the monitor were a forty-foot theatrical screen.

This photo inspired someone during the question session to ask whether the increasing tendency for people to watch movies on very small digital screens has influenced Murch’s editing decisions. He replied that it has to some extent, though from the beginning of his career at the end of the 1960s he has had to keep the smaller television screen in mind. Yet he does not edit primarily for the tiny images on mobile devices: “If you cut for the big screen, it will work for the small screen. If you cut for the small screen, it won’t work as well for the big screen.” The Master speaks. So far, the theatrical experience remains the basis for moviemaking.

The Guardian has a video interview with Walter Murch discussing Particle Fever.

A monitor in Walter Murch’s workspace, with two white human figures at the lower corners to indicate scale.

VIFF extremes

The Missing Picture (2013).

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival, known to all as VIFF, has been undergoing some big changes. It lost its primary venue, an ageing but cozy multiplex surrounded by pubs, creperies, music clubs, and other marks of downtown culture. Alas, the Empire Granville 7 is now shuttered, to be renovated as a retail space. VIFF must spread its bounty more widely.

As before, films are shown at the Cinematheque and the Vancity media center. The new venues include the Vancouver Playhouse, the Rio Theatre, three screens at the Cineplex Odeon International Village, the Vancouver Centre for the Performing Arts, and the Goldcorp Centre for the Arts at Simon Frazer University. All the ones we’ve visited have been excellent screening spaces.

Everything we’ve seen has been on some form of video—excuse me, “digital cinema.” Apart from the occasional 35mm or HDCam show, DCP projection, after a couple of years of teething pains, is the norm. Not that this guarantees uniformity. Albert Serra’s Story of My Death, a peculiar portrait of the elderly Casanova, still looked (probably intentionally) like it was shot on VHS. The furor about festivals’ conversion to digital formats, discussed in this 2012 blog entry and extended in my little e-book, belongs firmly to history. Henceforth film festivals will be file festivals.

Genres plain and fancy

El Mudo.

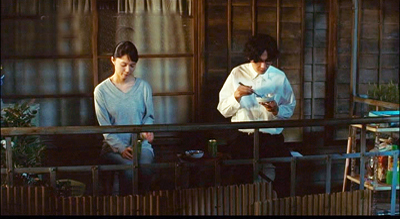

As usual at VIFF, the range is wide. At one end of the scale is a feel-good dramedy like The Great Passage, Japan’s Academy Award entry. The central character is Majime, a shy and unworldly young linguist who is drafted to help create a dictionary of Japanese as a living language. An otaku when it comes to words, he soon devotes his life to fulfilling the mission. Over the years he manages to find a girlfriend and earn the respect of the elders steering the project and the friendship of a ne’er-do-well colleague who prefers alcohol to etymologies. The dweeb Majime, despite his sweater-vests and sleeve protectors, becomes moderately sociable, while his pal acknowledges that his own commitment to a geeky endeavor shows he’s not as cool as he thought.

The English title is misleading; a better one might be Crossing the Sea of Language, since the central metaphor is that of charting the ebb and flow of usage. The process is dramatized by setting the start of the project in 1995, before Internet 2.0. The professor overseeing the project points out that the arrival of the Web speeds up language change. The Net works its way into the plot, as card-based research gets replaced by algorithms and word searches. A lot of the film’s humor arises when sequestered scholars, like those in Ball of Fire, have to figure out what this younger generation means when it calls something bad (i.e., good).

Ishii Yuya, who brought to VIFF Sawako Decides (2010) and Mitsuko Delivers (2011), tells his heart-warming story in a trim, efficient manner. His composure could teach our Hollywood directors a thing or two. I didn’t see a wasted shot or gratuitous camera movement, and you might miss Ishii’s virtuoso handling of a crowded office space as volunteers pack in to beat the deadline.

You can often spot a director’s skill in delicate touches. Here, I admired a gentle hook between two scenes. Majime has written a florid, anachronistic letter to Kaguya declaring his fondness for her. At the end of one scene he walks away from the camera clutching the note, which the framing centers on. Cut to a distant shot of him with Kaguya, the letter a small detail alongside his left leg.

Most viewers, I’m convinced, scan to find the letter and then wait with an amused tension for Majime to awkwardly offer it. It’s a good example of gradation of emphasis: No need for a close-up at the start of the second scene. This sort of unforced, easygoing presentation of a plot with a serious point—the quiet heroism of committing yourself to something of value to your community—makes The Great Passage as much worth exporting to North America as Departures and Shall We Dance? have proved in years past.

A more offbeat genre film is El Mudo, a Peruvian quasi-thriller, quasi-comedy from Daniel Vega and Diego Vega. After a day of dreary complaints and insults, the magistrate Constantino finds his car window smashed. What else is new? Soon after, he’s driving through traffic and is apparently wounded by a sniper. He loses his voice but becomes doggedly determined to uncover what he thinks is a conspiracy.

Constantino is not your raging rogue investigator. His muteness only increases a fixed, slightly scowling demeanor that suggests stoicism, boredom, or emotional vacuity. He refuses to perform the exercises that might strengthen his voice, as if he welcomes the loss of one more channel of expression. Everyone else seems normal, but Constantino (played superbly by Fernando Bacilio) might have walked out of an Aki Kaurismaki movie. The filming is in tune with the protagonist–static and prolonged shots, shrewd but unemphatic angles that simply wait for something to happen.

The result is an anti-action film. The assassination attempt, if that’s indeed what it is, is merely a bump in what is otherwise a drab long take filmed from the back seat of Constantino’s car. After waiting for a traffic light to change, he proceeds and suddenly slumps sideways as we hear four faint cracking sounds and watch the car drift onto the curb.

When the case is solved (perhaps) during a police raid, poor Constantino waits outside and so merely glimpses the stunt that would get visceral treatment in another movie. By the end, he finally smiles with pleasure, revealing himself as at a memory of maternal affection; he’s a mama’s boy after all. Il Mudo is a continuous pleasure throughout and is to be recommended to any fan of deadpan grotesque.

Many missing images

We’ve suggested, in both Film Art and elsewhere on this site, that a documentary film can be highly artificial. As long as it purports to make claims about the nonfictional world, the film can stage scenes and even use animation to support its points. A new test of this idea has come along in the form of Rithy Panh’s muted but powerful memoir of Khmer Rouge atrocities, The Missing Picture.

It employs some documentary conventions, like newsreel footage and voice-over commentary, but it seeks to present what was never put on film at the time. Panh’s family is shipped out of Phnom Penh, sent to forced labor and starvation in the countryside. Medical experiments are conducted with humans. Children are forced to pound out fertilizer and haul bodies to burial pits. The Party cadres, of course, eat well. Western intellectuals may have praised the Khmer Rouge as disciplined Communist idealists, but “the revolution they promised exists only on film.” How do you show what was never shown, not even widely known?

To provide a counter-film, Panh fills tabletop tableaus with carved clay figures. By the hundreds, these little effigies populate toy settings of work camps, hospitals that are merely storehouses for the dying, and landscapes that call forth children’s fantasies of escape and memories of happy family life. The figures themselves, squat and chunky, wear emblematic clothes–most often, gray work pajamas–and bear hollow-eyed expressions hinting at sullen fear or merely numbness. Panh’s childhood self is clothed, against all orders, in a pink shirt with yellow dots, which not only lets us identify him but suggests his yearning for the world of color that the Khmer stamped out.

As The Missing Picture proceeds, it becomes more reflexive. The Khmer officials show their propaganda films to the camp audiences, and Panh takes the opportunity to show his figures gathered and obediently watching. At the end, he reminds us that those who resisted are still wandering among us, like ghosts. Some things, he grants, should not be seen or known. “But should any of us see or know them, then he must live to tell of them.”

VIFF may be living in many new houses, but it’s definitely living, and as splendidly as ever.

The Empire Granville 7 was the last remaining movie house on Vancouver’s Theatre Row, which at one time had over twenty theatres. On the Granville 7’s future as retail space, a story is here. This article mentions that the Granville 7 originally absorbed a theatre called the Coronet. Cinema Treasures supplies more details of Granville 7 history. Images of the interior demolition of the house are here.

The Maestro of Chagrin Falls

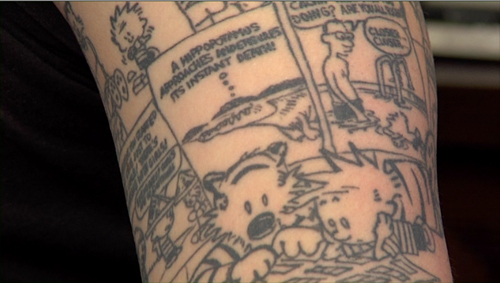

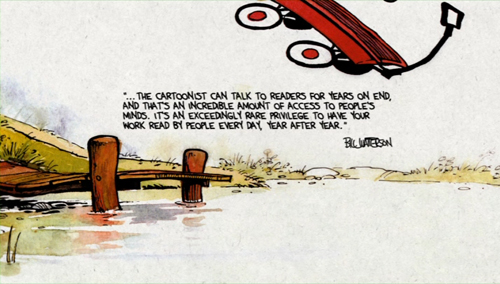

A fan’s tattoo, from Dear Mr. Watterson (2013).

DB here:

Bill Watterson, creator of Calvin and Hobbes, was probably the best cartoon draftsman since Carl Barks and Walt Kelly. His versatile line could be thick or thin, fluent or jagged. His coloring was rich, his layout experimental in the Herriman vein. His energetic picture stories provided zany humor and an unsentimental look at childhood imagination.

If Schulz treated kids as miniature adults, complete with obsessions and neuroses, Watterson saw Calvin as an adolescent in a child’s body, a rebellious teenager-to-be surrounded by adversaries and fools. Schulz’s Peanuts kids suffer in thin, wriggly lines, but Calvin’s mood swings from rage to rapture are rendered by manic exaggeration in the classic cartoon tradition. Meanwhile Hobbes, contrary to his name, exercises a gentling effect, becoming a tolerant Superego to Calvin’s Id.

Watterson was the Pynchon of cartoondom. His studio in Chagrin Falls, Ohio yielded a solitude rare for a publishing celebrity. He almost never appeared in public and seldom answered mail. In one of his rare public gestures, he criticized syndicate power, the tired old strips put on life support, and the scramble for licensing deals. Accordingly, he permitted no merchandising beyond book collections. Any Calvin and Hobbes toys or T-shirts or decals you see around you are DIY handicraft. After ten years Watterson simply halted the strip, an abnegation that drove his millions of admirers to despair. And he has remained reclusive.

Dear Mr. Watterson, which won a Golden Badger award at our Wisconsin Film Festival, sprang from Joel Schroeder’s fondness for the strip. He realized early on that interviewing Watterson wasn’t in the cards. So he set out to find ordinary readers who would testify to their love for Watterson’s creation. He found plenty of eloquent ones, but the movie is no mere fanboy indulgence. Schroeder’s travels took him to many of today’s top cartoonists, from Berkeley Breathed to Stephan Pastis, as well as critics and syndicate executives.

By outlining the shape of Watterson’s achievement in comics history, Dear Mr. Watterson mutes its admiration with regret, and not merely because Watterson quit at the height of his popularity. The film shows that, as one interviewee puts it, Calvin and Hobbes is very likely the last great comic strip.

Why? The conditions of publishing have a lot to do with it. As newspapers got thinner and smaller, the space allotted to comics shrank. Complex compositions and spacious storytelling became difficult in the slots allotted to Sunday strips, while the daily panel formats were minuscule. Only the sketchiest drawing survives the reduction.

The squeeze was starting in Schulz’s day: Peanuts was the beginning of the “minimalist” look of Cathy and Fox Trot. Watterson’s bold drawing style and appetite for scale posed problems for publishing. Ironically, as Schroeder pointed out in his Q & A, the sort of freedom and flexibility Watterson sought would become available a decade later on the Net.

Something else suffocated comics creativity. Just as tentpole films need an array of ancillaries, a successful cartoon demands the womb-to-tomb merchandising that Watterson foreswore. Children need to be hooked on the franchise before they can read. Garfield clothes and toys introduce infants to a pudgy beast that will stalk them throughout their lives, on lunchboxes and calendars and mugs and mousepads and refrigerator magnets and TV shows and “Is it Friday Yet?” placards for office cubicles. Watterson realized, I think, that being surrounded forever by leering images of cute creatures was one version of Hell.

Schroeder, a graduate of UW—Madison, has made a smart, touching movie. It deserves wide circulation and even, I should say, a PBS airing. It’s at once a tribute to a fine artist, a probe into comics history, and a revelation of how integrity can be maintained in the era of Monetization. Turning down hundreds of millions of dollars, Watterson in effect said something that almost no one imagines possible today: I don’t need that much money.

One observer comments that when Calvin and Hobbes ceased, many critics expected its fan base to dwindle, because it wouldn’t be maintained by all the spinoffs. Instead, parents pass down their Watterson paperbacks as family heirlooms. Fans have the lavish three-volume compendium of the strips, which is selling briskly on Amazon, while school libraries are replenishing their holdings of the slim anthologies. Our children are following the adventures of the hyperkinetic brat and his imaginary tiger in the best way: By reading books.

P.S. 2 May: Chris Blunk of Through a Glass Productions writes this followup:

Coincidentally, this past Sunday I met John Glynn, who works at Andrews/McMeel promoting their properties to Hollywood (such as Garfield and Over the Hedge). He was at the Free State Film Festival in Lawrence, Kansas where he showed the Sundance-boosted Small Apartments, also based on an Andrews/McMeel property. He was the first person I’d ever met who has any kind of semi-regular contact with Watterson. Though Watterson retains nearly all ancillary rights to his characters, A/M-Universal consults him on book printings, electronic distribution, etc.

While there were several tidbits that thrilled a fan like me, one item he mentioned particularly pertained to your article. He claimed that traffic at the Universal comics website (www.gocomics.com) is by and large driven by the Calvin and Hobbes classic – i.e. rerun – strips. The majority of visitors to all other comics on the site – including popular current strips like Get Fuzzy, Pearls Before Swine, Dilbert, etc, – arrive through Calvin and Hobbes.

So in addition to being propagated through handed-down book collections, as you pointed out, Calvin has managed to attract new fans and dominate comics circulation even in the new frontier of the web that grew into being long after Watterson’s retirement. And this with no new strips published in the past 20 years.

He told a couple other anecdotes that were similarly surprising. Such as a time in the early 90s when Spielberg was involved in some animation projects (Tiny Toon Adventures, Family Dog, Animaniacs, etc) and made inquiries about the rights to Calvin and Hobbes. According to Glynn, Watterson turned down a direct phone call with Spielberg himself reasoning they had nothing to discuss.

Thanks to Chris for his thoughts and information, and for reading our blog.

P.P.S. 16 July 2013: Gravitas Ventures announces that it will be releasing Dear Mr. Watterson on theatrical and VOD in November.

Dear Mr. Watterson.

Silent films, old and new

Blancanieves

Kristin here:

February and March have been good to silent cinema. Time for a round-up of some highlights as we impatiently anticipate Il Cinema Ritrovato, coming up in a little over two months.

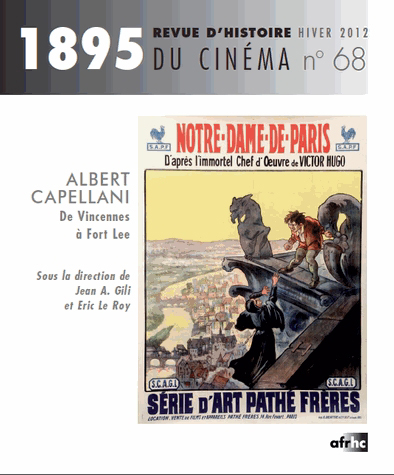

Publications on Albert Capellani

In reporting on the 2010 and 2011 programs of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I highlighted one of the festival’s major revelations, that of the silent films of Albert Capellani. These generous doses of Capellani’s splendid films were put together by Mariann Lewinsky, who realized his importance after she included some of his shorts in her annual “Cento Anni Fa” programs. In my entries I argued that Capellani was revealed as one of the early cinema’s great masters. (The 2010 entry is here, and the 2011 one here.)

Not surprisingly, during the intervening years, scholars have been busy researching Capellani’s films and career. March 6 to 24 saw a major retrospective at the Cinémathèque Française. (Information on the program is still available online, as is a detailed press release.) Shortly before it began, the first biography appeared: Christine Leteux’s Albert Capellani: Cineaste du Romanesque, with a foreword by Kevin Brownlow.

Leteux discovered Capellani in May of 2012, thanks to seeing Notre-Dame de Paris and Les Misérables at the Forum des Images in Paris. Setting out to learn more about the filmmaker, she realized how thoroughly his memory had nearly vanished from film history. She sought out and received the cooperation of his grandson, Bernard Basset-Capellani, whom she describes as “intarissable” (inexhaustible) on the subject.

The result is a solid, traditional biography, with chapters mostly organized around the companies for which Capellani worked (Pathe, SCAGL, World, Mutual, and so on) and some of his key films (Les Misérables, The Red Lantern). The prose style is easily readable French, at least to someone like me with an average knowledge of the language. For an interview with Leteux concerning the book, see here.

The book is on sale at the Cinémathèque’s shop, which unfortunately does not sell online. It was supposed to be available on Amazon.fr, but so far is not. The easiest way for those outside France to order it is through three third-party book-sellers on amazon.fr, all offering it at the cover price of 14.90 €. Leteux’s book is a vital source for anyone interested in early cinema.

I was pleased to see that the last chapter ends with some quotations from my second entry on Capellani, ending with “With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work.”

The book includes a filmography and list of films available on DVD. These include a new one, a restoration of The Red Lantern by our friends at the Cinematek in Brussels, available on Amazon.fr or directly from the Cinematek’s shop.

The French-language historical journal on cinema, 1895, timed its March, 2013 issue to coincide with the Cinémathèque’s retrospective. It is entirely devoted to Capellani. I have not had a chance to see it yet, but the table of contents is available here. The only online purchasing source for individual issues I have found is here; the page gives a lengthy summary of the contents.

Mariann continues to search for more surviving prints for restoration and eventual inclusion in future editions of Il Cinema Ritrovato. She has sent me some tantalizing news about recent discoveries and restorations. There will be a third Capellani season in 2014. This will probably include some of the director’s American films: Social Hypocrites (now restored), Flash of the Emerald (the one surviving reel), Inside of the Cup (surviving but so far with no projection print), Eye for Eye (two surviving reals), Sisters, and the French film Le Nabab. Other possible restorations include House of Mirth, La belle limonadiere, and Oh Boy!

A description of the 2013 Ritrovato festival is available here.

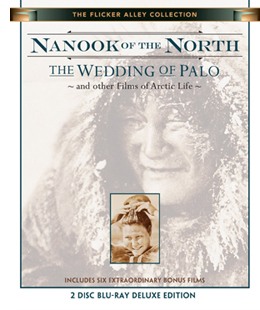

Nanook and friends

Early this year we posted our annual list of the ten best films of ninety years ago. It featured the classic early documentary, Robert Flaherty’s Nanook of the North. In March our friends at Flicker Alley released a two-disc Blu-ray edition of Nanook paired with the 1934 Danish feature, The Wedding of Palo (Palos Brudefærd). The latter is one of those titles that one occasionally encounters on the fringes of older historical surveys, but it has been difficult indeed to see. This new print is a 2012 restoration from a George Eastman House original 35mm nitrate copy.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

Nanook is familiar enough, but The Wedding of Palo is not. It was made by the Danish explorer and anthropologist Knud Rasmussen, who appears in a brief introductory passage. Clearly he was influenced by Flaherty’s work. He combines a simple fictional narrative with documentary scenes of traditional Inuit life in eastern Greenland. The basic story involves the heroine Navarona, whose brothers are reluctant to lose their housekeeper by allowing her to marry. Two men of the tribe court her and come into violent jealous conflict. Interjected are sequences of a salmon hunt, a festival, a traditional song duel between the two rivals, and a polar-bear hunt. The staged dialogue scenes involve sound recording, with no subtitles but the occasional brief intertitle to translate.

As in Nanook, the non-professional actors are remarkably natural, especially the “actress” portraying the heroine. There is a cute young boy brought in at intervals for comic appeal, and the members of the village seem always to be laughing and enjoying a suspiciously carefree life. The film has the advantage of more spectacular scenery than that in Flaherty’s film, with huge mountains and glaciers in place of the vast ice-covered vistas (see bottom image).

As usual, the Flicker Alley team has gone beyond the call of duty with this release. It includes not only the two features, but six bonus films, as described in the press release:

Nanook Revisited (Saumialuk) by Claude Massot was made in the same locations used by Flaherty. It shows how Inuit life changed in the intervening decades, how Flaherty consciously depicted a culture which was then already vanishing, and how Nanook is used today to teach the Inuit their heritage. Nanook Revisited was produced in 1988 on standard definition video for French television. Dwellings of the Far North (1928) is the igloo-building sequence of Nanook re-edited and re-titled as an educational film; Arctic Hunt (1913) and extended excerpts from Primitive Love (1927) are by Arctic explorer Frank E. Kleinschmidt; Eskimo Hunters of Northwest Alaska (1949) by Louis deRochemont shows many activities seen in Nanook thirty years after, and Face of the High Arctic (1959) depicts the ecology of the region, produced by the National Film Board of Canada.

Altogether, the films run an impressive 281 minutes. There’s also a booklet with excerpts from Flaherty’s book, My Eskimo Friends, an essay by Lawrence Millman, “Knud Rasmussen and The Wedding of Palo,” and notes on the films.

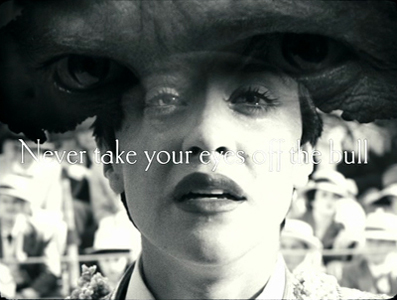

Snow White and the Seven (?) Bullfighting Dwarves

In 2011, a French film, The Artist, gained huge attention in the infotainment media as a modern version of silent cinema, winning yet another Best Picture Oscar for the Weinstein brothers. It was a reasonably successful imitation of mid- to late 1920s cinema during the transition to sound. Now a much better modern silent film has arrived, Pablo Berger’s Blancanieves, a loose version of the Snow White story transposed to 1920s Spain. A famous bullfighter is paralyzed after being gored in the ring. His wife dies in childbirth and his scheming nurse marries him. She keeps his daughter, Carmen, away from her father by setting her to work as a downtrodden servant in his country estate. Upon her father’s death, the evil wife schemes to have her killed, and she escapes to the protection of a troupe of six bullfighting dwarves who, possessing uncertain arithmetic skills, bill themselves as seven bullfighting dwarves.

While The Artist was a fairly good imitation of 1920s Hollywood filmmaking, Blancanieves is a pastiche of the 1928-29 era of European silent cinema. It draws on what I have termed the International Style of filmmaking, a late 1920s blend of influences from the French Impressionism, German Expressionism, and Soviet Montage movements. One could almost pass it off as a genuine film of the era.

At times there are subjective effects à la Impressionism. A superimposition conveys Carmen’s memories of her father’s crucial instructions to her, and superimposed images of hands waving handkerchiefs present the enthusiam of the crowd’s plea for the bull to be pardoned.

This was also the period in which the power of the wide angle lens, particularly in close-ups and in low-angle shots, was exploited, initially in Soviet cinema and then all over Europe. Blancanieves is full of such shots, as in the frame at the top of this entry and in these two shots from the opening scene:

There are also montage sequences, building up to flurries of very short shots. This accelerated-editing technique is typical of both Soviet and French filmmaking of the era.

The too-frequent use of handheld camera in Blancanieves detracts somewhat from the feeling of authenticity. In the late 1920s, cameras were too heavy to be handheld. They could be strapped to the body of the cinematographer with harnesses, but that creates a subtly different look. And during the late 1920s, shots with the camera holding on a character while the background spins around behind him or her would have been achieved by placing both camera and actor on a large turntable. (This effect apparently was pioneered in Germany in the mid-1920s). But the occasional dramatic lighting effects, particularly in the climactic scene, are distinctly reminiscent of German cinema.

In general, the narrative is charming and amusing. The heroine’s pet rooster provides exactly the sort of comic relief that is common in films of the 1920s, and the story has an effective fairy-tale quality. I found the ending a bit disappointing and certainly not typical of the films of the 1920s. Still, Berger has clearly watched an enormous number of 1920s European films and absorbed their styles. He can imitate the International Style remarkably well, telling a tale that is appropriate to the 1920s and yet has a touch of humor that doesn’t belittle the silent era.

Blancanieves was released in the US on March 29 and is currently making the rounds of art-houses and festivals.

Other entries discussing the International Style and wide-angle filming at the end of the silent era can be found here and here.

The Wedding of Palo