Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

All play and no work? ROOM 237

Room 237 (2012).

DB here:

Rodney Ascher’s Room 237 gathers the thoughts of five people concerning the deeper, or wider, or just awesomer meanings evoked by Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Those thoughts will strike many viewers as fairly far out there. Me, not so much.

Over the top

Room 237 adroitly blends several documentary genres. It recalls Cinemania and Ringers in its investigation of fan cultures. But instead of focusing on the personalities and lifestyles of the fans, Ascher concentrates on their readings of the movie. We never see the commentators. In this respect, it evokes the newly emerged genre of video essays as practiced by Kevin B. Lee and Matt Zoller Seitz. Yet it doesn’t offer itself as an earnest contribution to the critical conversation because Ascher freely intercuts stills and shots from other films, often to ironic effect.

In all, his film has the quizzical, gonzo flavor of an Errol Morris movie, minus the talking heads. But Morris is as interested in people as he is in their ideas. Ascher is interested in the ideas, and the way they swarm over and burrow into a film we thought we knew.

So he performs the sort of surgery more appropriate to the Zapruder footage. In the boldest test of cinematic Fair Use I’ve ever seen, a great many clips from the Warner Bros. release are run, slowed, halted, backed up, blown up, and overwritten as support for the interviewees’ claims. Ascher never tries to counter their arguments; at times he supplements them with extra evidence.

The results seem, to many, at best far-fetched and at worst (or best, from an entertainment standpoint), wacko. One of Ascher’s interviewees believes that The Shining is a denunciation of the genocidal destruction of Native Americans. Another takes the film as an exploration of the Theseus myth. Another believes that the film makes references to the Holocaust. Another finds a welter of subliminal imagery pointing to “a dark sexual fantasy.” Another sees the film as Kubrick’s apologia for staging the faked footage of the Apollo 11 moon landing.

Are these interpretations silly? Having spent forty-some years teaching film in a university, I found much of them pretty familiar. Some of the specifics were startling, but I’ve encountered interpretations in student papers, scholarly journals, and conference panels that had a lot of similarities.

If you think that this just proves that all film interpretation is ridiculous, you can stop reading now.

Because most film enthusiasts think that at least some movies need interpreting. We assume that like artists in other media, some writers and directors are using their medium to transmit or suggest meanings. And if a movie doesn’t express its makers’ ideas, perhaps it can still bear the traces of ideas out there in the culture. This “reflectionist” idea, tremendously popular among both journalists and academics, allows us to interpret even escapist fare.

Our interpretive itch has been around for a long time. Centuries of commentary have accrued around the Bible, the Torah, the Koran, and other texts deemed sacred. Secular texts, from Homeric epics to last month’s bestseller, have been scoured for hidden meanings too. The search hasn’t just been confined to literature, of course. An entire school of art history, called iconology, has devoted itself to deciphering objects, compositions, and other features of paintings. Even musical pieces without verbal texts have been “read.”

If at least some movies need interpreting, The Shining would seem to be a prime candidate. The film creates many questions about the reality of what we see and hear, and it seems to point toward regions larger than its central tale of terror. The director was one of the most ambitious filmmakers of the twentieth century, a film artist who could use a genre-based project like the famously puzzling 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) to convey ideas about the place of human history in the cosmos. Why couldn’t he do the same thing with a Stephen King horror novel?

What’s wrong, then, with the five critics’ readings? Why do many viewers find them strained and forced, even loopy? One of the many virtues of Room 237 is that it forces us to ask: What do we do when we interpret movies? What makes one film interpretation plausible and another not? Who gets to say? What historical factors lead ordinary viewers to launch this sort of scrutiny?

All in the family

We all grant that movies have conventions. In an action picture, the bad guys have extraordinarily bad aim, except when it comes to winging the hero or plugging his best friend. Similarly, film criticism relies on a batch of conventions about what things to look for and how they should be talked about. No quickie film review, for instance, is complete without discussing acting.

Interpretation, a central activity of film criticism, has its conventions as well, and the Room 237 interviewees make some moves that are common to interpretation in academe and elsewhere. For one thing, they assume that The Shining is more than a standard-issue horror movie. Most cinephile and academic critics would agree that we have to go beyond this movie’s literal level.

Some of the Room 237ers’ conclusions echo critically respectable interpretations already out there. One idea held by other critics is that the film is to some degree a parody or critique of horror conventions. Another is the conviction that the film says something about the repression of the Native American population. The Overlook Hotel is built on tribal burial grounds, a history that hints an earlier, oppressed America returning to avenge a great wrong.

Other Room 237 interpretations don’t show up in the mainstream critical literature, but they aren’t unknown in wider traditions of interpretation. Take numerology. Some interpreters of Biblical scripture find multiples of seven to be of divine significance, and so does the Holocaust advocate in Ascher’s film. According to him, the novel Lolita, which Kubrick adapted, makes 42 a symbol of fate. In The Shining, it becomes a symbol of “danger and malevolence and disaster.” Why? Multiply 2 x 3 x7 and you get 42. Danny wears a jersey with the number 42, there are at one point 42 vehicles in the hotel parking lot, and 1942 is the year in which Hitler launched the Final Solution.

Similarly, anagrams aren’t unknown in some interpretive traditions. Scholars have claimed to find in Shakespeare’s plays encoded references to the real author (Marlowe or Francis Bacon or the Earl of Oxford). Ferdinand de Saussure, one of the founders of modern linguistics, whiled away his later years with detecting anagrams in Latin poetry. Joining up with this method, the interviewee who sees The Shining as an apology for faking the Apollo landing rearranges the letters on the room key to spell out MOON ROOM. And the moon, says the critic, is 237,000 miles from our earth.

I grant you that such cabalistic maneuvers aren’t common in film criticism. But plenty of others on display in Room 237 use the same reasoning routines that we find in consensus critical writing.

What do I mean by reasoning routines? When we interpret a movie, we’re making inferences based on discrete cues we detect in the film. What cues we pick out and what inferences we draw vary a lot, but the process of inference making tends to follow certain conventions.

Consider the claim that Kubrick is warning that we shouldn’t expect a conventional horror film. A more mainstream critic would point to the flamboyant performance of Jack Nicholson, at once grotesque, comic, and ominous. This would seem to be a strong ensemble of cues asking us not to take the film straight, and perhaps implying that it’s a send-up, in a grim register, of its genre. But none of our 237ers mention this cue as a basis for their interpretation.

Instead, they scan the setting for disparities. The hotel’s architectural features sometimes differ from one shot to another. A chair is present in one reverse shot of Jack, but in the next reverse shot, it’s gone. The hotel geography can’t be plotted consistently. Moreover, one of Wendy’s visions during her desperate flight through the corridors at the climax invokes the clichés of ordinary shockers: dust, cobwebs, and skeletons—all the paraphernalia that the film has studiously avoided up to this point. These anomalies encourage the interpreter to see the film as parodying typical horror movies. The 237 critics are picking out cues less obvious, they would say, than Nicholson’s over-the-top acting.

Making meaning, or making up meanings?

Ascher’s interviewees don’t always go for minute cues. They focus as well on many items that conventionally invite symbolic interpretation. Mirrors signal any sort of reversal, such as Danny’s backward steps through the maze or the film’s symmetrical beginning and ending. Something open—a door, a character’s eyes—suggests knowledge and acceptance; something closed, like elevator doors, suggests repression. If a character enters a space, that space can be taken as a projection of the character’s mental state, as when Danny nears his parents’ bedroom and gets into “his parents’ headspace,” as one 237 critic puts it. Another commentator suggests that Jack’s job interview at the beginning of the film might be entirely his hallucination, a question raised by academic critics as well. Such speculations on the border between the subjective and objective are commonplace in discussions of horror, fantasy, and that in-between register known as the fantastic.

Puns are another time-tested inferential move. You can find a cue in the mise-en-scene and then “read” it with a verbal analogy. Snow White’s Dopey on Danny’s door suggests that the boy doesn’t yet realize what’s going on; but when the dwarf disappears, Danny is no longer “dopey”. A crushed Volkswagen stands for Kubrick’s telling King that his artistic “vehicle” has obliterated the novelist’s original “vehicle.” Abstract patterns in carpeting become Rorschach tests: Are those shapes mazes? Phalluses? Wombs? NASA launching pads? Mainstream critics might not fasten on these particular cues, but many wouldn’t resist the urge to find puns. After all, even Freud interpreted a dream in which his patient got kissed in a car as exhibiting “auto-eroticism.”

The Room 237 critics, following tradition, let the cues and inferences lead them to what I call both referential and implicit meanings. Referential meanings involve concrete people, places, things, or events. Spielberg’s Lincoln refers to a specific historical context and people and events in it. Implicit meaning is more abstract and is something we might expect to be intended by the filmmaker. So, for instance, Lincoln could be interpreted as about the necessary mixture of principle and expediency in politics; to achieve virtuous policies, you may need to cut moral corners.

The 237ers make use of different degrees of referential meaning. The Shining makes clear references to the Native American motif, not only in the hotel’s décor but the manager’s line of dialogue indicating that the building rests on burial grounds. That line is a rather explicit cue, and one that many non-237 critics have taken up. In a similar vein are the mythological references; both Juli Kearns in the film and several academic critics have discussed the the maze/ labyrinth imagery as citing the legend of the Minotaur.

There are more roundabout cues to inferences about the Holocaust. Kubrick might have included a photo of Nazis or Prussian generals in the Overlook’s Gold Room salon, but he didn’t. So the critic defending the Holocaust reading has to look for what we might call “hidden references”—the numerology we’ve already seen, along with the German-made typewriter on Jack’s desk, which is an Adler (“eagle,” symbol of Nazism). There’s also a dissolve that, according to another critic, gives Jack a Hitler mustache.

The Room 237 critics gesture toward implicit meanings too. The Playgirl magazine that Jack is reading when he waits in the lobby suggests that troubled sexuality is at the center of this maze—a suggestion made more explicit in the fateful Room 237, where a beautiful woman, upon embracing Jack, turns into a haggard zombie. The references to both the North American and German genocides suggest the film induces us to reflect on the cruelty of those events. More broadly, one critic believes that the film has far-reaching thematic import: The Shining is about “pastness” itself, about coming to terms with history.

To be convincing, though, an interpretation can’t merely take a one-off cue to make references or evoke themes. What really matters are patterns.

Patterns of associations

Interpreters typically gather cues into patterns and then use them to bear thematic meanings. One instance of this maneuver comes early on in Room 237, when Bill Blakemore, proponent of the Native American genocide hypothesis, is attracted to a lone Calumet baking-powder tin, turned toward us on a shelf. Not only does the label show a tribal chief, but the plainness of presentation emphasizes the original meaning of calumet, the tobacco pipe used in Amerindian peace brokering. But that might be a one-off occurrence. Later, however, other Calumet tins are massed on another shelf–but turned from us. It’s not enough that the can has now been repeated. The change, Blakemore proposes, indicates that the original, straight-on image has turned into something hidden and dishonest—the destruction of the tribal population. The spatial opposition frontal/oblique has been made to bear a thematic difference between honesty and betrayal.

A similar duality, with a punning tint, is raised when Kearns traces how she came up with the Minotaur hypothesis. She points out that a skier poster (to her eyes, resembling a Minotaur’s silhouette) stands opposite a rodeo poster (“Bull-man versus cow-boy”). The poster led her to realize that the Minotaur sits at the center of a cluster of images that recur in the film. He presides over the labyrinth that is the hotel, which, Kearns argues, has an impossible geography, while the intertwined logo of the Gold Room recalls Theseus’s thread. In his alternate identity Asterios, the Minotaur suggests stars, which in turn suggest movie stars (who, we’re told, have stayed at the Overlook). The ski poster reads “Monarch,” which in a sense the Minotaur is, and we learn that royalty have visited the hotel too.

Or take the Holocaust reading. Apart from the fateful 42 motif, the Adler typewriter does other work. Its name (“eagle”) evokes the emblem of the Reich, but an eagle is also a prominent American icon. So the critic adds that Kubrick always uses an eagle to symbolize state power. How then to link it to Germany? The typewriter, as a machine, evokes the bureaucratic efficiency of Hitler’s mass deportations and executions. To back this up, the critic recalls Schindler’s List, in which typewriters figure extensively.

Such expanding clusters are common in interpretive activity because artworks often ask us to tease out associations. Early in The Shining, the Torrance family talks about the Donner party. We’re invited to see the reference as conjuring up slaughter, isolation in a snowbound environment, and the collapse of civilized restraints—just what the film will give us. Critics of all stripes track the dynamic of the artwork by creating associative patterns out of repeated elements. When Wendy and Danny watch the film Summer of ’42 on TV, it’s not the 42 that attracts the distinguished academic critic James Naremore. He links the embedded film about the sexual attraction between an older woman and a younger man to the moment when Danny runs out of the maze and kisses Wendy on the lips. These moments are part of a constellation of images and events marking the film as “flagrantly Oedipal,” in that it presents the son’s struggle against the hostile father. Naremore is able to build on this cluster to suggest that the film is unusual in rehearsing different, non-Freudian aspects of the Oedipus myth.

You might object that, unlike Naremore and other professionals, the critics in Room 237 build up associations from their personal experiences rather than what’s objectively on the screen. Blakemore says that he noticed the Calumet label because he grew up in Chicago near the Calumet River and as a child he gathered Indian pottery. Yet the conventions of mainstream movie reviewing allow critics to look inward too. Jonathan Rosenbaum opens his piece on James Benning’s El Valley Centro:

About halfway through I found myself, to my surprise, thinking about Joseph Cornell’s boxes, those surrealist constructions teeming with fantasy and magic—dreamlike enclosures that make it seem appropriate that Cornell lived most of his life on a street in Queens called Utopia Parkway.

The only difference between Rosenbaum’s associational links and Blakemore’s would seem to be the cultural level of the references. Why should the amateur not be allowed to import less arcane personal associations into an interpretation?

Finally, you might object that the Room 237 critics are too focused on trying to infer Kubrick’s intentions. Kubrick had wanted to make a film on the Holocaust at some point; he read Raul Hilberg’s Destruction of the European Jews and corresponded with the author. Kubrick also read Bruno Bettelheim’s Uses of Enchantment, a Freudian explanation of fairy tales; hence the Hansel and Gretel and Big Bad Wolf references in the film. One Room 237 critic says that Kubrick was bored after making Barry Lyndon and wanted to make a movie that reinvented cinema. Yet, again, journalistic critics commonly make assumptions about what the filmmaker is up to. Even academics, trained to believe in “the intentional fallacy” and to “never trust the teller, trust the tale,” can indulge in hypotheses about directorial purpose. In explaining the eccentricities of the lead performance, Naremore notes that in interviews, Nicholson reported that Kubrick told him that “real” performances aren’t always interesting.

Tie me up! Tie me down!

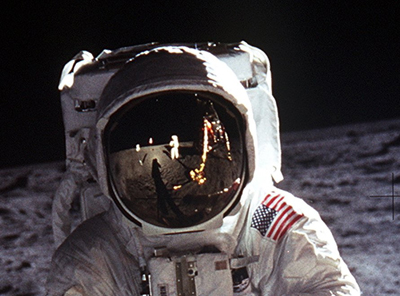

Apollo 11 moon landing, July 1969.

For mainstream film criticism, however, the patterns and the significance-laden associations they trigger have to be constrained somehow. Not everything is relevant to the implicit meanings of the film. This condition, I think, shows the real gap between the 237ers and the pros. One interviewee’s enthusiasm marks this difference: Kubrick, he says, is “thinking about the implications of everything that exists.” No mainstream critic would dare make this move.

What are the constraints on interpretation within the community of publishing critics, either journalistic or academic? Here are some common ones.

Salience: The patterns and associations are more plausible if they’re readily detectable– if not at first, then on subsequent viewings. The case gets stronger if the motif is reiterated along many channels—image, dialogue, music, sound effects, written language. The Native-American genocide association is moderately salient, present in both items of décor and in Ullman’s line about the burial grounds. Accordingly, many viewers have picked up on it. On the other hand, even repeated viewings don’t help us (me, at least) to identify the magazine as Playgirl.

Coherence: The patterns and associations are more plausible if they’re related functionally to the narrative—not just to single moments but to its overall development. Most critics writing about The Shining assume that it’s centrally about the disintegration of the family. They have gone on to relate this to the way that the delusions of patriarchy subject women and children to its control. (That common academic trope of “the crisis of masculinity” hovers nearby.) This thematic thrust can be traced scene by scene, and the motifs of fairy tales, American history, and the Minotaur can blend with specific plot twists and character presentation. Some of the Room 237 critics’ readings mesh with the arc of the narrative, but many, such as certain overlays during dissolves, seem unmotivated by narrative factors.

Congruence with other relevant artworks: The patterns and associations gain plausibility if they can seem congruent with other works by the same artist or in the same genre. For example, the uncertainty about whether Jack is imagining the Gold Room or whether it’s a genuine supernatural entity is characteristic of horror/ fantasy films. Here the 237ers are more in line with their mainstream colleagues. The unresolved ending, leaving us with a puzzle about whether Jack himself is a reincarnation of someone from the past, isn’t out of keeping with the ending of 2001. The room 237 itself, one of Ascher’s critics suggests, is a bit like the old man’s bedroom and the space pod in the earlier film.

Appeal to authorial intention: The critic’s case gains plausibility if people having significant input into the work claim the patterns and associations were deliberately put there. While rewatching The Shining, Nicole Kidman remarked of Kubrick:

“He always said that you had to make sure the audience understood key pieces of information to follow the story, and that to do that you had to repeat it several times, but without being too obvious about it,” Ms. Kidman said. “Here, in this scene, look at how there is this rack of knives hanging in the background over the boy’s head. It’s very ominous, all of these knives poised over his head. And it’s important because it not only shows that the boy is in danger, but one of those very knives is used later in the story when Wendy takes it to protect herself from her husband.”

Most mainstream critics would, I think, find that Kidman’s inference rings true. It picks up a fairly salient cue, it invokes a pattern involving the knives, and it squares with the unfolding of the narrative. She reports that Kubrick understood the need for patterns to have salience, and it seems quite likely that he was the sort of artist to use pictorial prefigurations like this. Note, though, that this shot exemplifies function-driven dramaturgy—foreshadowing—not thematic interpretation.

By contrast, consider the Room 237 critic who takes The Shining to be Kubrick’s apology to his wife for staging the fake Apollo 11 moon landing. As Ascher presents the case, it involves a long chain of causation. It starts from the claim that, whether or not NASA actually sent a crew to the moon, the landing that the public saw was staged. The project needed front-screen projection. Kubrick was the master of those special effects. He agreed to help film the fake landing. Later he felt guilt for it. So by making a film about a husband/wife conflict, Kubrick confesses to his mistake. This backstory would gain a lot of plausibility if a NASA staffer or one of Kubrick’s crew came forward to support any part of it, in the way Kidman offers testimony about Kubrick’s working methods. It would be even better if the Apollo tale could be tied to the specifics of the unfolding narrative. And it would be best if the interpretation of this film didn’t depend on a (questionable) interpretation of another film–the Apollo 11 footage.

The Apollo 11 argument illustrates the risk of appeals to intention: they tend to substitute causal explanations for functional ones. That is, they tend to look for how something got into the film rather than what it’s doing in the film. But that’s a risk that professional critics run as well when they appeal to intention. The problem is just more apparent when the causal story that’s put forward seems tenuous.

I’ve argued that the cue-inference method and the use of association to create patterns aiming at referential and implicit meanings are involved in all interpretations, staid or unorthodox. But the constraints I’ve just sketched aren’t so fundamental to interpretation as such. They typify the established critical institution, which includes journalism high and low, belles-lettres (e.g., The New York Review of Books), specialized cinephilia (eg., Cinema Scope), and academic writing.

Not everybody belongs to that institution. There are other arenas of film criticism, and there’s no mandate that discussion in those realms adhere to the constraints urged by professional criticism. Some readers prefer to muse on barely perceptible patterns, incoherence, unlimited association, and relatively unrestrained speculations about Kubrick’s mental processes. Fans like to think and talk about their love, and anything that gives them the occasion is welcome, no matter what any establishment thinks. To a considerable extent, Ascher’s film documents the habits of folk interpretation.

Some precedents

But why now? Why do amateur critics today launch these ambitious expeditions? The short answer, as so often, would be: Because they can. As Juli Kearns points out, it was thanks to VHS, then DVD, that she was able to scrutinize The Shining. Home video has allowed us, including all the obsessed among us, to halt and replay a movie ad infinitum—a process that Ascher’s own film freely indulges in. I think, though, that there are other historical factors that impel fans to dig ever deeper into the movies they love.

Most obviously, there’s the rise of the puzzle film, the movie that litters its landscape with hints of half-buried meanings. The vogue for this began, I suppose, in the late 1990s with films like Memento, Magnolia, and Primer. Even then, though, there were different constructive options. Primer called out for re-watching because much of its plot was obscure on a single pass; you had to examine it closely to figure out its basic architecture. By contrast, Memento’s principle of reverse chronology was evident on first viewing. I suspect that most viewers, like me, studied the film to pick up the finer points of its form and to try to disambiguate the Sammy Jankis plotline. Still different was Magnolia, with a perfectly comprehensible plot that planted a Biblical citation in its mise-en-scene. In this case, the extra stuff suggested a thematic level that might not be apparent otherwise.

Some critics have objected that the Room 237 critics turn Kubrick’s film into a mere puzzle movie, the implication being that puzzle movies are inferior forms of cinema. Yet I don’t see a good reason to scorn them. Assuming that films often solicit our cognitive capacities, I don’t see why artists shouldn’t ask us to exercise them. Cinema takes many shapes, and one critic’s puzzle (“Rosebud,” “Keyser Söze”) is another critic’s mystery. Some artworks throb with passion; some are more intellectual and austere. There is Mahler, and there is Webern. Even artworks with a lyrical or emotional dimension ask for decipherment and meditation too. Dante explained to his patron Can Grande della Scala that he had laid layers of non-literal meanings into The Divine Comedy. The poem, he explains, is “polysemous.” Its meanings are to be grasped and pondered upon in the manner of Scripture.

Long before puzzle movies came into fashion, literary modernism had assigned readers this sort of homework. The idea of loading every rift with ore was taken quite seriously by T. S. Eliot, who supplied footnotes to The Waste Land. Could you really hope to understand it without reading Jesse Weston’s From Ritual to Romance? James Joyce built so many layers into Ulysses that he had to take a critic aside and explain them to him, so the critic could then publish a guidebook to the novel. Finnegans Wake is supersaturated with references, puns, and esoteric meanings. If ever an artwork needed decoding, this is it. One of the earliest scholarly studies is called A Skeleton Key to Finnegans Wake.

In cinema, Peter Greenaway’s Tulse Luper series seems to be his bid for Joycean stature. More successful has been Godard, who in his mid-1960s films created an aesthetics of dispersal, a display of citational pyrotechnics that reaches its apogee in the Histoire(s) du cinéma. Surely this suite of films has engaged many critics in a process akin to puzzle-solving. More to our point today, we might see Kubrick’s films, especially 2001, as bringing aspects of high modernism into mainstream cinematic genres. We can hardly be surprised that after courting many interpretations of 2001 (whose subtitle cites a classic literary text), this director might be posing us similar tasks in a horror film.

Something else besides the rise of the puzzle film and high-modernist polysemy is probably responsible for the rise of this sort of fan dissection. Throughout history storytellers have experimented with creating what we might call richly realized worlds. Naturalist literature describes fine details of the writers’ society at the time, while Gulliver’s Travels and Looking Backward take us into alternative realms. The rise of fantasy and science-fiction literature has led readers to demand to know the history, lore, and furnishings of the imaginary places they visit. The Lord of the Rings saga, part of what Tolkien called his legendarium, is the obvious prototype, but the tendency to fill every niche of imaginary worlds is there in the Star Wars and Marvel universes too.

Once fans have become accustomed to raking every frame for clues about the plumbing system of the Millennium Falcon, they are going to expect an equal density in ambitious works in other genres. But not all films, or even all genres. I suspect that we won’t get the equivalent of Room 237 for My Fair Lady or Dinner at Eight. Combined with the intrinsic fascination of The Shining, Kubrick’s well-publicized concern for detail in the futuristic 2001 and A Clockwork Orange leads us to expect that a film centered on the enclosed world of the Overlook would yield bounty when scrutinized.

Finally, I should note that the seeming capriciousness of the Room 237 readers has a counterpart in one strain of academic interpretation. Borrowing from both Surrealism and a post-Structuralist concern for a “free play of the signifier,” Tom Conley and Robert B. Ray have practiced a criticism that yields results strikingly similar to the work of Ascher’s interviewees. Ray cultivates free association, as when he puns on characters’ names, and Conley has been known to find, as one Room 237 critic does, significant images in cloud formations.

The only major difference is that these academics typically discount an appeal to the filmmakers’ intentions: that move would inhibit the critic’s free-ranging imagination. Once in a while, the Room 237 critics follow suit on this front. They withdraw from attempts to anchor their readings in Kubrick’s life, thought, and personality. One who appealed to intentions early in the film has abandoned them by the end, and another frankly admits: “One can always argue that Kubrick had only some or even none of these [interpretations] in mind, but we all know from postmodern film criticism that author intent is only part of the story of any work of art.”

One of Ascher’s most engrossing final sequences shows John Fell Ryan’s effort to run The Shining forward and backward at the same time, superimposing them to create startling new images like the one that surmounts today’s entry. Folding the film over onto itself is in the spirit of Conley and Ray’s work, I think. The gesture hearkens back to that “irrational enlargement” of films that the Surrealists sought when they dropped in on the middle of one movie, stayed a little while, and then hurried out to slip into another. (They would have loved multiplexes.) Again, the apparently far-fetched meaning-making strategies of our amateur critics turn out to have some kin in the academic establishment and in the history of artistic culture.

I’ve made Room 237 more solemn than it is. It’s a pleasurable and provocative piece of work. It too would be worth interpreting, but I haven’t tried that here. I’ve used it as a kind of AV demonstration. It handily illustrates how interpreting a movie involves certain informal reasoning routines shared by “amateur” and “professional” critics. The differences between the two camps depend largely on what cues the critic fastens on in the film, what associational patterns the critic builds up, and how strongly the critic subscribes to the professional constraints on inferences.

Whether the cues, the patterns, and the inferences based on them seem plausible depends on what particular critical institutions have deemed worthwhile. Claims that won’t fly in mainstream or specialized cinephile publications can flourish in fandom. The purposes and commitments of these institutions may sometimes overlap, but we shouldn’t expect them to.

My account of these critics’ interpretations is drawn wholly from Ascher’s film. All of the interviewees have published more detailed arguments for their views. Bill Blakemore’s thesis about the film’s portrayal of Amerindian genocide is here. Go here for Juli Kearns’ writings on various aspects of Kubrick’s film. Jay Weidner’s thoughts are here. Geoffrey Cocks’ thesis is laid out in his book The Wolf at the Door: Stanley Kubrick, History, and the Holocaust (2004). Jay Fell Ryan discusses and updates his observations in this tumblr site. See also Ryan’s reflections after seeing Room 237.

There seems little doubt that musical texts featuring a verbal text or carrying a program that the composer has sanctioned (like Tyl Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks) can be interpreted in the manner of a novel or painting. Even non-programmatic works without texts have been subjected to interpretation. A still controversial example is Ian MacDonald’s 1990 The New Shostakovich, which launches detailed interpretations of hidden meanings in the composer’s work. For critiques, see Richard Taruskin’s articles in Shostakovich in Context, ed. Rosamund Bartlett, and Shostakovich Studies, ed. David Fanning.

The standard book on secret codes in the Bard is William F. Friedman and Elizabeth S. Friedman, The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. On Saussure’s search for Latin epigrams, see Jean Starobinski, Words upon Words, trans. Olivia Emmet and “The Two Saussures,” Semiotexte 1, 2 (Fall 1974).

James Naremore’s wide-ranging interpretation of The Shining is in On Kubrick. Dennis Bingham provides a detailed history of journalistic and academic interpretations of Kubrick’s film in “The Displaced Auteur: A Reception History of The Shining,” in Perspectives on Stanley Kubrick, ed. Mario Falsetto, 284-306.

Shane Carruth explains that the puzzle aspect of Primer involves only making chronological sense of the plot, which avoids redundancy to an unusual degree.

It’s just that the way the narrative is constructed, I can see how when the story asks you to pull the threads together that’s probably going to happen where threads are pulled together wrong. I definitely didn’t set up this narrative to be open to interpretation. I mean, except for a few things. For the most part, the information is in there to have a very concrete answer as to what is happening in the narrative.

Some critics have worried that Ascher’s film gives viewers an impoverished view of what film criticism is. See for instance Girish Shambu’s comments here. For my part, I doubt that viewers come away believing that the views of these interviewees are typical of criticism as practiced in the mainstream. Nor do I see why Ascher’s movie needs the bigger dose of Theory that Girish prescribes. For my take on Theory (as opposed to theories and theorizing), see the book I edited with Noël Carroll, Post-Theory:Reconstructing Film Studies.

There’s another issue. Like Girish, Jonathan Rosenbaum reprimands the 237 critics for turning The Shining into a puzzle movie.

One way of removing the threat and challenge of art is reducing it to a form of problem-solving that believes in single, Eureka-style solutions. If works of art are perceived as safes to be cracked or as locks that open only to skeleton keys, their expressive powers are virtually limited to banal pronouncements of overt or covert meanings.

I’ve already proposed that a problem-solving approach need not reduce the artwork to a bloodless abstraction. (By the way, I don’t see puzzle-solving and problem-solving as quite the same; I’d say that a puzzle is a particular kind of problem.) But perhaps we should read Jonathan’s first sentence as objecting only to problem-solving approaches that posit “single, Eureka-style solutions.” That would rescue Eliot and Joyce, perhaps, although realizing that Ulysses is a remapping of The Odyssey is something close to a Big Solution to the novel.

In any case, it’s not clear that the 237ers are absolute in their arguments, at least not all the time. The last section of the film chronicles them backing away from their own machinery, confessing that there are dimensions to the film that they haven’t yet grasped, acknowledging that it remains elusive, mysterious, confusing, and, as Dante or a modern theorist might say, polysemous. Moreover, it seems clear that these critics all acknowledge the “expressive powers” of The Shining. They all testify to having been deeply shaken by it; that’s what fuels their urge to probe it. They just claim, like many critics, that the film’s significance extends beyond the visceral and emotional arousal it creates.

On richly realized worlds: J. R. R. Tolkien chose the Latin term legendarium to characterize the entire body of his writings set on the fictional planet Arda, (primarily on the continent of Middle-earth) and the universe in which it exists. The legendarium includes works published during his lifetime, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Adventures of Tom Bombadil, as well as posthumous publications edited by his son Christopher, The Silmarillion, “The Quest of Erebor,” and The Children of Hurin. Not strictly speaking part of the legendarium but closely related to it are the numerous drafts published as Unfinished Tales and the twelve-volume “The History of Middle-earth” series, as well as previously unpublished drawings and maps collected by Wayne Hammond and Christina Scull in J. R. R. Tolkien: Artist & Illustrator and The Art of The Hobbit. (Kristin wrote this paragraph, as you can probably tell.)

For samples of the post-Structuralist interpretative modes I mention, see Robert B. Ray, The Avant-Garde Finds Andy Hardy, and Tom Conley, Film Hieroglyphs.

In another entry I suggest that interpretation is only one critical activity we might pursue. On contemporary Hollywood cinema’s penchant for puzzle films and richly realized worlds, see my book The Way Hollywood Tells It. In Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema I try to show that just as we can analyze the conventions of a genre or mode of filmmaking, we can analyze the conventions of film talk. It’s one thing that I think a poetics of cinema brings to the table: an effort to disclose what principles shape a critical argument. As for my own tastes, I value consistency, coherence, constrained ascriptions of intention, and historical plausibility in interpretations. But in my own research, I favor analyzing films’ functional dynamics over hunting down hidden meanings.

P.S. 7 April: Thanks to David Kilmer for a corrected quotation!

The Simpsons: Tree House of Horror V: The Shinning (1994).

I’ll never tell: JASON reborn

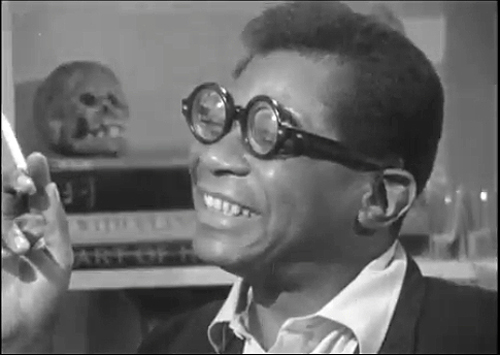

Portrait of Jason (1967).

DB here:

A white-walled apartment; no windows visible. Screen left: a day bed wedged into the corner. Center of screen: A fireplace and mantelpiece. Screen right: an easy chair with an end table boasting a lamp and ashtray. Behind it a bookcase. It’s as colorless a performance space as you could ask for, except perhaps for the skull on a bookshelf; but even that isn’t real.

In this arena a slender black man with thick Harold Lloyd glasses and a winning smile talks to us. His first words, delivered with calm sincerity, are immediately revealed as false.

My name is Jason Holliday. My name is Jason Holliday. (Breaks into laughter.)

(With a confiding smile) My name is Aaron Payne.

Over a single night, from 9 PM to 9 AM he talks to the camera, and eventually with the unseen filmmakers. High on marijuana and drunk on single malt scotch, he recounts his life as a gay hustler, recalls his family and childhood, and offers his analysis of how to behave around whites. He strikes attitudes, mimics the slaves in Gone with the Wind, and sings show tunes.

At first the filmmakers encourage him to tell this or that story, but late in the film one offscreen voice presses him. “Why’d you write letters about me?” “You should suffer.” “You’re full of shit.” Near the end Jason is sobbing. “If you don’t know,” he says, “I love you.” The offscreen voice is pitiless: “Stop that acting.”

Portrait of Jason (1967) is a legendary film that until recently had gone astray. Last Friday our Cinematheque hosted the US premiere of the restored version. The movie tells quite a story, but so too does Dennis Doros, VP of Milestone Films and the man whose tenacity brought back this delightful, disturbing record of Jason’s long night.

In and out of focus

It was a shocker in its day. What other film talked so frankly about gay life, race relations, and drug use? Where else would you hear virtually every four-letter word in the American vernacular? Shown in festivals and independent art houses, it won an astonishing level of praise. Here is Newsweek:

Jason lives, and Jason gives one of the most incredible performances ever recorded on film. This inverted Everyman, this anti-matter Jack Armstrong has a terrible tale to tell about how much it can hurt to be human, and he tells it in magnificently rich language with the gay desperation of an artist.

But the film was doubtless worrying. It circulated in the same year as Blow-Up, Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Bike Boy, In Cold Blood, I am Curious (Yellow), Rush to Judgment, and I, a Woman—a year in which studio films, exploitation, art movies, and the underground seemed to be joyously blitzkrieging conventional values and good taste. Portrait of Jason opened at the New York Film Festival after a summer in which American cities had been shaken by riots in black neighborhoods. Now came a film in which a black man blithely reveals the cynicism behind his shuck-and-jive for rich white employers. And he’s a gay prostitute.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

Her other feature-length films (The Cool World, The Connection) owed something to American cinéma vérité. Variety sourly remarked of Jason, “C’est la vérité,” and ran its review alongside a review of Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies. But Clarke’s daughter Wendy recalls that although Shirley was friends with vérité filmmakers, she doubted that they could capture reality objectively. Leacock and Pennebaker would have found it impure to jab their own comments into the subject’s monologue the way Clarke and her lover Carl Lee do. Clarke’s approach is closer to that of the French cinéma direct, as pioneered by Jean Rouch and Chris Marker. In Le joli mai (1963) the filmmakers ask their interviewees frankly: “Are you happy?” This question underlies Portrait of Jason too.

Apart from the coaxing and goading interjections, Clarke’s filming method seems artless. There are fewer than fifty shots in 105 minutes, and they’re linked by black frames and out-of-focus passages. Both transitions mimic casual shooting. Yet Dennis Doros and Wendy Clarke pointed out that Clarke loved cutting. She was aware of the paradox:

I had enormous patience in terms of editing and I’ve always adored that part of making films, and in an odd way as I develop as a director I set up less and less situations to edit. The better I’ve become as a director, the less editing, the more I’m thinking in terms of the last twenty or thirty minutes that will have no editing at all.

In Jason the cutting isn’t as casual as it might seem. The blurry passages conceal edits, and the order of scenes doesn’t reflect the progress of the shoot. It will take patient research to determine the original chronological order of the reels we see. Clarke claimed that she enjoyed editing because at that phase she was really discovering her film.

Clarke’s apparently loose shooting, often running the camera until the magazine is empty, may seem a version of Warhol’s static films like Eat. It seems likely that she also learned from Warhol’s approach to performance. His psychodrama-based dramaturgy, as explained in J. J. Murphy’s fine book, constantly hovers between confession and put-on, and this is central to what happens in Clarke’s film. But Clarke gives her movie a more clear-cut narrative contour than Warhol would, with Jason’s monologue devolving from grinning self-assurance to stricken self-exposure.

Clarke and her crew acknowledge the act of filming, although they don’t emerge from behind the camera, as some do in The Connection. This recognition of artifice can encourage the subject to perform, to play up to the camera for the approval of the filmmakers and the audience. And a chance to perform is exactly what Jason wants. Now, he chortles, he can show off the nightclub act he’s been working on. The film is at once an audition and an effort to define himself. He’ll create “a picture I can save forever—one beautiful something that’s my own.”

So in the stage space between the day bed and the armchair, he strolls and poses. He fires off randy one-liners like “If I’d been a ranch, I’d be called Bar None.” Flipping his boa, he channels Mae West, Butterfly McQueen, Dorothy Dandridge, and Harry Belafonte. (Did he rename himself in honor of Judy Holliday?) He jiggles ice cubes in his glass with the winking panache of Dean Martin at the Sands. Clarke once said that in watching the rushes she was reminded of her choreography films: Jason seemed to be dancing.

To recover from his numbers, Jason flings himself offstage, flopping back on the daybed or sinking into the armchair as his cigarette burns down to the filter. In these moments, he seems to be candid. He admits that even with all the money he’s borrowed from friends, he’s not ready to take the show-business plunge. Drunk and giggling, he tells of childhood beatings with a razor strop: you mustn’t stick your butt up high but press yourself against the bed; that hurts less. His oscillations of mood are dislocating, passing from exuberance to frankness to self-mockery. Moments of self-celebration (“I’m a male bitch”) can also seem inadvertent glimpses of vulnerability–which may be exactly what Jason wants us to think. At one level Jason gives lessons in impression management.

I see his tears at the climax as born of authentic pain, but I can’t be sure. Earlier in the film he bragged: “When I do my pathetic bag, I’m really pathetic.” The layers of Jason’s one-queen show seem endless. Clarke said in an interview that everything he does on film—his jokes, stories, even the weeping—she had seen many times before. “His entire life is a role.” He seems to spill everything, but one of his mottos, delivered with finger snaps, is: “I’ll never tell.”

Treasure hunt

Wendy Clarke, Dennis Doros, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey.

How was this extraordinary film brought to light again? That was the story Dennis Doros told at our departmental colloquium the day before the screening. His company Milestone has specialized in reviving forgotten or neglected films of all types, including American independent work like Kent MacKenzie’s The Exiles and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. Simply trying to get a quality version of Portrait of Jason took him on a hunt that revealed, after many twists, that the closest thing to an original print was residing here in Madison, Wisconsin.

Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research made an effort to collect off-Hollywood cinema, including the works of East Coasters like Emile de Antonio, Doris Chase, and Shirley Clarke. Clarke’s collection, like several others, harbors vast amounts of personal papers and film material.

Clarke shot Jason on 16mm, but no negative has yet been found. There were 35mm prints made, and some wound up in archives, notably at the Museum of Modern Art. But among the material Clarke began giving the Center in 1973 were six reels of silent 16mm footage and several reels of sound recording. When they were inspected, the reels were believed to be either outtakes or stretches of a rough cut. We didn’t yet have a release print of Jason to compare them to.

Many years later, after searching high and low across the world, Dennis had the good idea of adding up the footage counts of our reels. The length was four minutes longer than the final running time of the film. After further research, our footage was revealed as Clarke’s original cut of summer 1967, which was trimmed and revised for the film’s official premiere at the New York Film Festival. This was, says Dennis, “the great irony in the search. Because Shirley Clarke had created a film that was meant to look unedited—filled with out-of-focus shots and black leader—Shirley’s 16mm fine-grain master was hidden all these years as outtakes!”

Our archivist Maxine Fleckner Ducey assisted Dennis throughout his quest. They found that the sound material, alas, was indeed outtakes, and Dennis still needed a good 35mm print of the Film Festival/release version for sound and final checking. More hunting ensued. Searching through the WCFTR collection, Dennis found an old telegram from Jacques Ledoux of Belgium asking permission to borrow a print from the Swedish Film Institute. Dennis contacted Jon Wengstrom at that archive, and soon he had a copy that could guide the restoration.

The whole process was enabled by funding from the Academy and from a Kickstarter campaign. To support that effort, Dennis and his wife and business partner Amy Heller made a video that traces their search for Jason. Their restored version had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, and it will go on to other festivals and selected theatres. The image and sound quality far surpasses that of earlier versions in circulation.

A sort of epilogue came when Dennis and Wendy Clarke visited Madison last week. They dipped into Shirley’s vast collection, and in only two days they found treasures of a personal as well as professional nature. Perhaps some of their discoveries will surface as bonus materials on the eventual DVD release. Dennis and Wendy stayed on to introduce Friday’s premiere and take questions.

A charming pendant to Jason was the screening of a half-hour of Wendy’s Love Tapes series. In the 1970s Shirley shifted to making videos, and Wendy followed her path and became a major video artist. The series began as Wendy’s video diaries, but in 1977 she began recording people talking about what love means to them. Each person sat alone in a room, seeing her or his image on the monitor, and talked for three minutes. Over the years, the formats shifted from reel-to-reel tape to VHS to DVD, but the theme remained the same.

Wendy now has over 2500 tapes, shot in museums, schools, shopping malls, prisons, centers for battered women, and even in a booth at the World Trade Center. Ideally, she says, everyone on the planet should make one—a goal that isn’t so far-fetched thanks to smart phones and the Internet.

The Love Tapes assembly we saw with Jason was broadcast on PBS in 1982, and it was alternately grave and exhilarating. People celebrated love they’ve found but also mourned its passing and reflected on how it shaped their lives. Wendy has tried other themes, notably death, but love works best. “You talk about everything in it.” Sort of what happens in Jason too.

Thanks to Wendy Clarke and Dennis Doros for their visit to Madison, and to Jim Healy for facilitating it. Thanks also to Joe Lindner and Mike Pogorzelski, two graduates of our program, for enabling the Academy to take part in Milestone’s project. Maxine Fleckner Ducey was a great help on the Milestone project and, on a daily basis, makes us proud to have the WCFTR connected to our program. Thanks as well to current WCFTR director Vance Kepley for background information on the Clarke collection.

Project Shirley recently won Milestone an award from the National Society of Film Critics (the company’s sixth). Look for more Project Shirley material to surface from our holdings. And who, as Dennis asked in colloquium, will write the first book on this remarkable artist?

I drew Clarke’s comments about editing from Gretchen Berg, “An Interview with Shirley Clarke,” Film Culture 44 (Spring 1967), 55; and “A Conversation—Shirley Clarke and Storm de Hirsch,” Film Culture 46 (Autumn 1967), 47. The Newsweek review of Jason appeared in the issue of 6 November 1967, and the Variety review appeared on 25 October 1967.

The trailer for the new version of Jason is here; it includes side-by-side comparison of an archived 35mm print and the restoration. Clarke’s discussion of Jason’s role-playing is captured in an episode of the TV series Cinéastes de notre temps, by Noël Burch and André S. Labarthe. You can watch it here.

On The Connection, see J. Hoberman’s lively introduction on the New York Review of Books blog. Jason is a prototype of the portrait genre of documentary, a subject covered with care in Paul Arthur’s essay, “Identity and/as Moving Image,” Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 24-44.

A sample of Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes is here.

Love Tapes (1982).

Got those death-of-film/movies/cinema blues?

Night Across the Street (2011).

DB here:

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

These squibs seemed especially damp this time around because while these guys were knocking Hollywood and/or art movies I was enjoying the Vancouver International Film Festival. If you’re willing to watch mainstream entertainments from outside Hollywood, or films that aren’t the bland arthouse fare full of stately homes and British accents, or even films that don’t chop every scene to splintery images, Dr. Bordwell has a cure in mind for you.

Had you been looking for breezy or outlandish entertainment, for example, the Dragons and Tigers wing didn’t disappoint. Helpless, from South Korea, is a thriller built around identity theft. I thought it was clumsily plotted, but it sustains curiousity through the apparently bottomless series of discoveries a man makes about his missing fiancée. Jeff Lau’s East Meets West is a Hong Kong farrago of rapid-fire gags, weird haircuts, references to old Cantopop, and nonchalantly wacko storytelling. Granted, the central idea of making the Eight Immortals of legend into modern superheroes (and one supervillain) is smothered by Scott Pilgrim-style SPFX. Still, I will watch Karen Mok Man-wai and Kenny Bee in anything, albeit for different reasons. Closer to mainstream Hollywood tastes was Nameless Gangster, in which a restless flashback structure traces the rise of a flabby brute from customs agent to top drug smuggler. Yoon Jongbin’s slickly-made film ends with an abruptness that recalls the conclusion of The Sopranos.

Of all the pop-entertainment movies I saw at VIFF, the audience favorite was doubtless Key of Life, a nifty Japanese crime comedy. An amnesiac hitman and a shambolic slacker swap identities in a cunning series of coincidences that brings on some satisfyingly menacing underworld types. Intersecting the men’s misadventures is a hyperorganized OL, or office lady, who determines to find herself a husband within a month. Everything sorts itself out, of course, with one nice wrapup saved for the middle of the closing credits. This is the kind of Japanese diversion I’ve recorded a liking for earlier (Uchoten Hotel and Happy Flight). Hampered by a wretched title, Key of Life probably won’t get US theatrical distribution, although it may make some headway on VOD. Aussie movie maven Geoff Gardner and I agreed that if we had the money, we’d buy the remake rights.

Everything new is old (again)

Tabu (2012).

Form is the new content, they say. (Too simple, but some do say it.) No surprise, then, that part of what appeals in contemporary cinema is its overt reworking of previous styles. Neo-noir is perhaps the most common current example, but ingratiating retro-stylings were on display in more rarefied forms at VIFF.

Part of the appeal is the rediscovery of the glory of the 4:3 aspect ratio. Kristin has already talked about how Pablo Larrain’s No appropriates a seedy U-matic look to tell its tale of 1970s Chilean politics. A similar pastiche effect emerged from Mine Goichi’s All Day, a short that used even grubbier video to parody Japanese family dramas. May we expect to see more VHS-looking movies? I wouldn’t mind.

Silent cinema pastiches are usually lame, as witness The Artist, which scrambles history and treats old films as oddly soft-minded. (No Hollywood drama of the late 1920s would have been built around a protagonist so feeble he tries to commit suicide twice.) Jean Dujardin, and contemporary audiences that adore his film, should catch up with Hayashi Kaizo’s To Sleep As If to Dream (1986), in which the contemporary story is played as a silent film and the rediscovered (fake) old film is accompanied by benshi commentary and music. The “forged” footage in Forgotten Silver also shows how good filmmakers can create convincing, pleasantly anachronistic imagery.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

More celebrated since its Berlin triumph (two awards) is another 4:3 exercise, Miguel Gomes’ Tabu. A vaguely 1920s prologue shows a brooding tropical explorer who has seen his ex-wife as a ghost. Then Part 1 (“Lost Paradise”) takes us to stately black and white imagery of contemporary Lisbon. It’s late in December, and Pilar is concerned about her elderly neighbor Aurora. The old woman is taken to a hospital and asks Pilar to find Aurora’s old lover, Ventura. By the time Pilar discovers him, it’s too late. After Aurora’s funeral, Ventura starts to explain how they met in Africa. Here starts Part II (“Paradise”).

Now the film becomes hypnotic. In Africa, Aurora is married to a sturdy, good-natured colonist, and she can hunt and shoot with the best of them. Ventura and his friend Mario, who’s becoming a pop crooner, are taken into the household. He and Aurora begin a torrid affair. Part II is rendered without onscreen dialogue, but not in exact mimicry of silent cinema. There is piano music, it’s true, and much of the action is carried by letters, as in a lot of silent movies. But there are no intertitles; instead, all the action is played out with the support of Ventura’s voice-over, occasionally supplemented by the young Aurora reciting letters she wrote. Moreover, Mario’s band and his singing are rendered in full lip-synch. More eerily, as Ventura explains the rise and collapse of the love affair, we get highly selective bits of noise—not everything audible in a scene, but perhaps the tinkle of glasses or a faint wind. These become the aural equivalent of glimpses.

“Paradise” gives us silent cinema not replicated, but refracted through memory and romantic longing. In a film paying homage to Murnau (a forbidden romance as in Tabu, the name Aurora recalling Sunrise), Gomes has apparently also sought to give us something like the “part-talkies” of 1928-1929. Those films had full-blown dialogue scenes (as in Part I) and other scenes containing only music and effects (Part II), relieved by synchronized musical numbers (a sequence showing Mario’s band performing by the pool). Tabu recovers something of the strangeness of those transitional films, notably Sunrise itself, while remaining highly contemporary. It knows that we can turn to tradition when we want to rekindle a romanticism that would look high-flown today.

Long live the long take

Beyond the Hills (2012).

At about 16 seconds per shot, Tabu has the same cutting rhythm as some early talkies, like The Black Watch and Hearts in Dixie. Today, as we’ve seen, the long take is increasingly the province of movies that play chiefly at festivals. All other things being equal, a movie with around 1200 shots, like the very popular Danish import The Hunt, will be an easier sell on the arthouse circuit than, say, Beyond the Hills, with only about 110 shots in 148 minutes. It’s a pity. Although The Hunt is a solidly crafted drama in the Nordic enemy-of-the-people tradition, it moves rather predictably across the combustible subject of false accusations of child molestation. Beyond the Hills, by Cristian Mungiu, director of Four Months, Three Weeks, and Two Days, is more enigmatic and demanding.

Voichita is a nun in a rural Orthodox enclave in Romania. She’s visited by her friend Alina. The two grew up as best friends in an orphanage, but Alina went to Germany to work, and now she insists that they must run off together. Voichita resists. Alina claims that Voichita once agreed to this plan. Has the young nun changed her mind and committed to the church? Or is Alina’s plan an idée fixe that Voichita has simply humored, without ever intending to join her? Were they perhaps lovers? Alina’s endless staring at Voichita and her lunges at suicide suggest deep passions at stake.

The refusal to supply full exposition makes characterization enticingly uncertain. Voichita’s wide-eyed sympathy for her friend can be seen as both pliable and stubborn, while Alina’s nearly wordless reprimands imply that Voichita has betrayed her. But perhaps Alina is just asking too much, or Voichita is being too unbending. The couple’s drama is played out against the stringent background of a female community ruled by a priest. Alina is incorrigible, not responding to the gestures of salvation extended to her, and agreeing, stone-faced, that she has committed every sin on a list of over 400. Eventually the pious souls decide that Alina is possessed, and her demons must be exorcised. In a simple gesture of solidarity, Voichita declares something like love for Alina, but too late.

Alternating discreet handheld takes with fixed shots staged in depth, making no concessions to impatience or easy responses, Beyond the Hills recalls the sobriety of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Bresson’s Les anges du péché. It plays out in a rougher-textured, muddier world, but it’s no less concerned with the dynamics of compassion and cruelty, dogmatism and eroticism. In each, a woman is ready to sacrifice herself for love. As Romania’s Oscar submission, Mungiu’s film deserves to find an audience in the US.

Long takes were also a specialty of the late Raúl Ruiz, whose penultimate film, Mysteries of Lisbon, won him probably the widest audience of his career. That film displayed his fascination with proliferating stories, but its adherence to a single plane of reality was exceptional in the career of a fabulist who enjoyed confounding all types of realism. In that regard, Night across the Street, his last fully completed work, is more characteristic.

An old office worker is about to retire and is convinced that someone is coming to kill him. While Don Celso awaits his assassin, he fraternizes with his co-workers, with schoolteacher and author Jean Giono, and with others in the hotel where he resides. He also recalls his childhood, when he talked to Long John Silver and went to movies with Beethoven. Eventually the plot shifts levels of reality even more radically, as one séance blends into another, characters shot down in a massacre return to life, and eventually Celso takes credit for inventing the people around him.

Mungiu’s handheld shots have no place here. As in Mysteries of Lisbon and his Proust film, Time Regained, the camera glides through this world with velvety assurance. Sometimes the characters do too, as they seem to ride the dolly or saunter in front of a blatantly unreal backdrop. Ruiz subverts academic cinema by using its well-upholstered technique, but he also mines film history. He revisits tableau staging in the shrewdly split set of Don Celso’s office, and he continues to exploit his more-Wellesian-than-Welles big-foreground technique.

Above all, the boy’s trip to the movies, in an awkwardly tilted image in which the usher usually blocks the screen, pays typically skewed homage to the medium’s enchantment. The mock film of Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream has given way to The Foxes of Harrow, the Hollywood cinema of Ruiz’s childhood.

Land, sea, and sky

small roads (2012).

When one thinks of the long take, James Benning comes quickly to mind, and small roads is true to form—in more ways than one. Forty-seven fixed shots in 102 minutes take us from the Far West to the South and to the Midwest before shifting westward again. The roads are indeed small, far from superhighways and traffic circles. As usual, landscape is the protagonist and slight shifts in image or sound arrest our attention. There are plenty of perceptual teasers. When a distant truck descends the distant sloping road above, it vanishes. Will it re-emerge in the nearer road? At another point, we wonder when, or if a car we hear will appear in the frame.

Hogarth spoke of art that leads the eye “on a wanton kind of chase,” and Benning’s roads—almost never seen from dead center, so we’re not given central perspective—carve oblique or sinuous paths into fields, plains, deserts, and forests. Road signs reenact the curve of the roadway, with carets and squiggles providing spare geometric “readings” of the piled-up surfaces of color and mass. There’s also some synesthesia. In one shot, I thought I heard mist rolling in. The topographies are real but through Benning’s strict scrutiny they become as fantastical as Ruiz’s dreamscapes.

That’s why I suspect that roads aren’t the real subject of the film. They serve as a pretext for Benning’s recurring interests in how wind curls clouds and makes branches tremble, how light outlines trees, how shapes like squat black oil derricks and the textures of fat snowflakes and soggy leaves can command the frame. Now that Benning has moved to digital filming, he has discreetly inserted some CGI. I couldn’t spot any, though one partial moon in daylight looks suspicious to me. No matter. Painterly beauty, along with a certain placid mystery, is enough for any movie nowadays.

At the other extreme lies the bustle of Leviathan, a poetic, quasi-abstract documentary by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. The filmmakers capture a New Bedford fishing trip through GoPro digital mini-cameras worn by fishermen, tossed into a netful of fish, or dragged through the water. Long takes abound here too, but it’s hard to say how many. As in The Man with a Movie Camera, the very boundary between one shot and another is put into question. So is the boundary between us and the space onscreen, as we’re weirdly wrapped in the extreme wide-angle yielded by this lens.

This is what you get when no human eye is looking through the camera. Often, in fact, nobody could look through the lens. No head, let alone human body, could occupy the space of some of these shots. Chains roll out past us from churning greenish darkness, while fish drift and slither on all sides. We’re right next to a gull trying to use its beak to lift itself to another area of the hold. Here the fish-eye lens lives up to its name. The camera bobs in a tank as fish are tossed in and spin aimlessly past. Coasting along the edge of the craft, we dip abruptly in and out of the heaving water, our plunge accentuated by brutal sound cuts. We chase starfish and ride waves, spinning up to watch gulls blotting out the sky. Accelerations of speed (again, Man with a Movie Camera comes to mind) render the action hallucinatory, especially since the shutter can capture foam with strobe-like precision.

One result is a disembodied, dehumanized vision of sea and sky: The camera as flotsam. But we also get bumpy, skittish visions of human labor definitely tied to bodies that harvest the ocean. Work activities are filmed from cameras lashed to the fishermen’s heads or lying on the deck among scallops to be shucked. Most documentary close-ups of artisans’ tasks are taken from far back and with long lenses; here the very wide-angle GoPro lenses not only show tasks from the inside, but their distortions exaggerate each gesture, sometimes heroically, sometimes grotesquely. Either way, human activity has been defamiliarized no less than undersea life.

We start the movie immersed in a welter of details and stay enmeshed for nearly an hour. Only then do we get an “establishing shot” showing the boat deck and mapping the overall process of filling and emptying the nets. And fairly soon after that, as if to parody the usual documentary about fisher folk, we get a four-minute shot of the captain dozing off while watching a TV show (apparently The Deadliest Catch). Leviathan ends with a sequence that brackets the chiaroscuro of the opening, but we no longer see a clam’s-eye-view of being snagged. Instead, we get barely illuminated darkness with whiffs of crimson teasingly darting to the edge of the frame, as if to signal the end, before swerving back to the center, then heading offscreen. Again, Ruiz has the line: Special shadows that give off light.

Ready to declare cinema dead? There is a cure for your malaise. We call it a film festival.

More of my thoughts on Ruiz can be found here and here. His widow Valeria Sarmiento completed his very last project, The Lines of Wellington.

On small roads and digital manipulation, see Michal Oleszczyk’s discussion at Slant and Robert Koehler’s informative review in Variety. In correspondence Benning confirms:

Yes, lots of compositing, but no speed changing, although the border cops are going around 100 mph. . . . Shot 26 has a sky that was filmed the next day about 100 miles away. And yes the moon was out, but that shot is pointing north so I filmed the moon in the southern sky during the day, and put it into the northern sky. All the compositing was done with shots I made; always somewhere nearby. (100 miles is nearby when you circle 2/3 of the US.)

You can learn more about Leviathan from Dennis Lim’s article on the filmmakers in the New York Times. The New York Film Festival provides a lengthy Q & A on its website. See also Phil Coldiron’s “Blood and Thunder: Enter the Leviathan“ in the latest Cinema Scope, with some superb frame enlargements. Above all, don’t miss the extract on vimeo, which gives you a good sample of the splendor of this film.

Leviathan (2012).

Make mine music, not to mention pictures

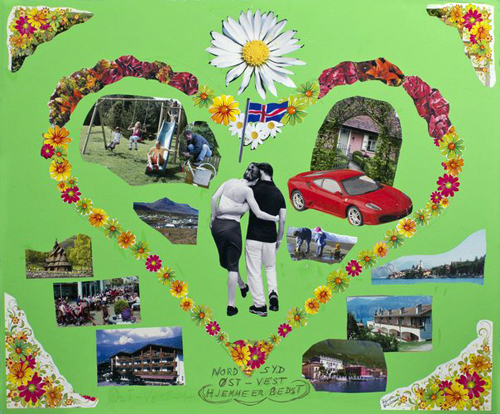

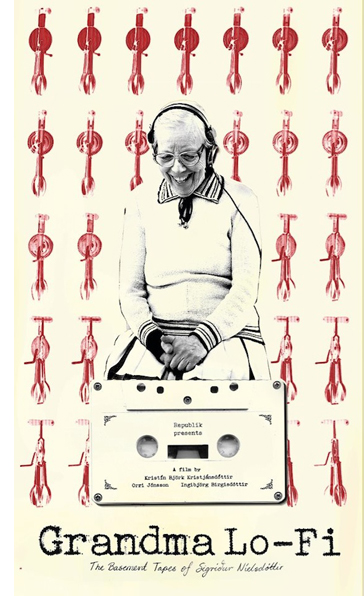

Collage by Sigrídur Níelsdóttir.

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has had strong commitments to certain types of cinema–Asian, Canadian, environmentally-sensitive documentaries, and perhaps least well-known, arts documentaries. I still recall seeing The Red Baton, a vivid account of Russian musical life under Stalin, at my first VIFF visit in 2006, and ever since I’ve tried to check out at least a few entries in this category. They’re not usually very daring formally, but they do open up areas of the arts that I cherish, and–just as important–areas I’m completely unaware of.

Childhood and the morning of the world

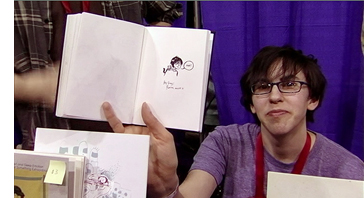

For instance, as an admirer of comic strips and comic books, I had to see Josh Melrod and Tara Wray’s Cartoon College. The institution in question is the Center for Cartoon Studies at White River Junction, Vermont. (Go here for the most educational college catalog I’ve ever seen.) Each year twenty students are admitted for the two-year MFA program, and the film follows several as they move through the curriculum.

Don’t be misled by the black clothes, Kool-aid hair, and cats’-eye glasses. These kids aren’t your usual Art School posers. They want to tell stories. Jen explores menstruation; Al, the 61-year-old Boston archaeologist, takes time off to learn to draw; and Blair the Mormon wants to chronicle his missionary work. Interviews with Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, and Chris Ware are salted through this story of intense work, achievement, and occasional disappointment.

Don’t be misled by the black clothes, Kool-aid hair, and cats’-eye glasses. These kids aren’t your usual Art School posers. They want to tell stories. Jen explores menstruation; Al, the 61-year-old Boston archaeologist, takes time off to learn to draw; and Blair the Mormon wants to chronicle his missionary work. Interviews with Lynda Barry, Art Spiegelman, Charles Burns, and Chris Ware are salted through this story of intense work, achievement, and occasional disappointment.

One accomplishment of the film is to remind us of the very unusual qualities needed to be a cartoonist. There’s the patience of drawing hundreds of panels, and sometimes the same figure in hundreds of different postures, along with the hours of fine-grain line work and coloring. There’s also the sense that of all artists, cartoonists are most in touch with childhood, that period, as Ware remarks, when each experience is “rich and warm . . . and days seem to last for weeks.”

Perhaps that’s why the students radiate that awkward innocence that’s easily mocked. They explain how they didn’t fit in with their high-school milieu; one man recalls that people assumed he was either gay or a British exchange student “because I didn’t contract all my g’s and used proper English.” The great thing students find at CCS, says Spiegelman, is that “instead of being the outcast in art school you get to be with a bunch of other outcasts.” Yet these outcasts bond, forming couples and offering group critiques, and cooperating on projects for conventions and festivals. Cartoon College teaches you a lot about cartooning, but it also reminds you of the vitality of young imagination.

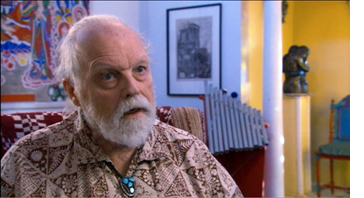

Lou Harrison, whom I knew chiefly as a pioneer of melding non-Western music with classical traditions, proved to be a fascinating figure in Eva Soltes’s Lou Harrison: A World of Music. This biographical account showed me that this man often considered marginal–far less well-known than Copland or Bernstein–in fact thrived at the center of the bohemian world of American music. He went to Mills College, taught at Black Mountain College, hung around with Henry Cowell and John Cage and Virgil Thompson, collaborated with Merce Cunningham and Mark Morris, and conducted the premiere of Ives’ monumental Third Symphony.

Harrison was open to every influence, from Schoenberg’s serialism to Harry Partch’s unorthodox instrumentation. He drew on Korean and Taiwanese music and Javanese Gamelan, and even composed pieces for Geiger counters (as a protest against nuclear testing). The result is music of great delicacy, with sumptuous textures and fluid melodies. Go here to listen to some samples.

Harrison was open to every influence, from Schoenberg’s serialism to Harry Partch’s unorthodox instrumentation. He drew on Korean and Taiwanese music and Javanese Gamelan, and even composed pieces for Geiger counters (as a protest against nuclear testing). The result is music of great delicacy, with sumptuous textures and fluid melodies. Go here to listen to some samples.

Like many of his peers and collaborators, Harrison was gay, and he wasn’t shy about saying so. The partner of his later years, Will Colvig, lovingly crafted unique instruments for his compositions. After Colvig’s death, Harrison struggled to put onstage Young Caesar, a gay-centered opera–for puppets, no less. “Lou was always out of fashion,” reflects conductor Michael Tilson Thomas. Unfashionable or not, Harrison left us music of pulsating lyricism and quiet, unforced radiance. The film’s celebration of this American original deserves wide circulation. Now a personal request to Ms. Soltes: How about Alan Hovhaness next?

Nordic thaws

Then there were two films that opened my ears. I wasn’t prepared for the brawny music of Kimmo Pohjonen, who is on roaring display in Kimmo Koskela’s Soundbreaker (aka Ice Bellows). Along with street mimes and face-painters, accordion playing has become a bad joke, but Pohjonen makes it a contact sport. Built like a torpedo, with short hair razored to a cellbock edge, he plays his amplified squeezebox like he’s grappling with a python. Our musician is first shown tramping across a frozen lake and then plunging through a hole before taking up his instrument and playing underwater.