Archive for the 'Documentary film' Category

Errol Morris, boy detective

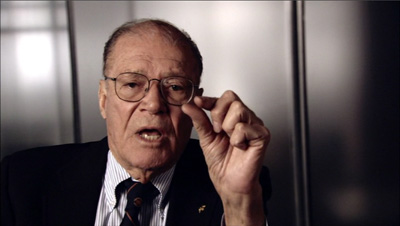

The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara.

DB here:

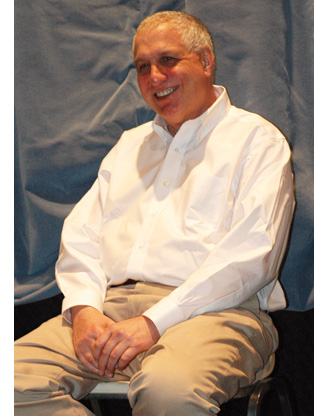

Over a couple of sunny days in late October Errol Morris visited the University of Wisconsin—Madison. It was something of a homecoming. Morris took his BA in history here, and was inspired by two legendary teachers, Harvey Goldberg and George L. Mosse. (“The UW saved my life.”) After a few years in graduate schools (Princeton, Berkeley), he went into filmmaking, working with Werner Herzog on Stroszek while it was shooting in Wisconsin.

Morris’s first film, Gates of Heaven (1978), examined pets, their owners, and the cemeteries that cater to both. Vernon, Florida (1981) reinforced Morris’s reputation as an aficionado of the backwoods bizarre. His reputation widened with The Thin Blue Line (1988), a true-crime story that cast doubt on whether an innocent man had been imprisoned for a murder. I’d argue that this film, along with Roger and Me, played a crucial role in opening theatrical markets to documentary film. From then on, Morris has been acclaimed as one of our finest filmmakers, finally receiving an Academy Award for The Fog of War (2003), a study of Robert McNamara’s prosecution of the war in Vietnam.

Morris’s first film, Gates of Heaven (1978), examined pets, their owners, and the cemeteries that cater to both. Vernon, Florida (1981) reinforced Morris’s reputation as an aficionado of the backwoods bizarre. His reputation widened with The Thin Blue Line (1988), a true-crime story that cast doubt on whether an innocent man had been imprisoned for a murder. I’d argue that this film, along with Roger and Me, played a crucial role in opening theatrical markets to documentary film. From then on, Morris has been acclaimed as one of our finest filmmakers, finally receiving an Academy Award for The Fog of War (2003), a study of Robert McNamara’s prosecution of the war in Vietnam.

Morris’ visit was the culmination of months of screenings in several Madison venues. The big weekend was ushered in by a lecture by Carl Plantinga, one of our most distinguished scholars of documentary film. He’s a professor at Calvin College, and like Morris, he’s a Wisconsin graduate (my Ph. D. student, ahem). Dave Resha, who wrote a dissertation on Morris, and Bill Brown, our accomplished documentarist, were on hand to join our guest on a panel. Perky and boyish, Morris offered a public lecture at the Student Union. Next day, the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art hosted a screening of his new movie Tabloid and a Q & A.

Morris is an exuberant presence, onstage and off. I could fill this entry with one-liners and anecdotes.

My high-school guidance counselor told me, “You should go to Wisconsin. They take anybody.”

I sometimes think of myself as someone who should be beaten up a lot.

Just because he’s a victim doesn’t mean he isn’t an asshole.

The electric chair is a very scary thing.

My wife says I should give up Twitter and start writing for fortune cookies.

Fred Leuchter, electric-chair repairman and Holocaust denier, smokes constantly but won’t be filmed with a cigarette. He explains, “You have to understand, Errol. I’m a role model for children.”

I don’t think anybody knows how crazy they are. I include myself and the persons in this room.

Morris’s visit was so stimulating that it got me thinking afresh about his career. While many documentaries engage in fact-finding, Morris’s films recall for me the figure of the classic detective, the nosy fellow drawn to secrets high and low. Morris is a fan of film noir (he thinks that Detour is at least as good as Citizen Kane) and he worked for a time as an investigator. His only fictional film, The Dark Wind (1991), is adapted from a Tony Hillerman mystery. It’s useful to think of Morris’s documentaries as private investigations—not illustrating an argument but exploring the mysteries around a situation or a personality. Like any investigation, his may lead nowhere or create more puzzles than it solves. Morris shines his penlight in some dark places, finding not only clues but some embarrassing items in the drawer or the back of the closet. The truth often has a sordid side, but that can harbor its own pleasures.

The filmmaker and the murderer

The Fog of War: “Rational individuals came that close to total destruction of their societies.”

History is a crime scene, and you’re the detective. Film can be a tool to solve the mystery.

Errol Morris

Morris’s recent films on the Vietnam War and on the abuses at Abu Ghraib prison (S. O. P.: Standard Operating Procedure, 2008) are somber inquiries into the mechanics of power and bureaucracy. Balzac said that behind every great fortune lies a great crime; for Morris behind every war lies many such crimes. Early on McNamara admits that his misjudgments cost thousands of lives. Morris’s reconstructions of prisoner treatment at Abu Ghraib are chilling neo-noir, filmed in chiaroscuro and featuring agonizing slowed-down imagery, as when a shotgun is fired into a cell and shells tumble out of the chamber.

He’s particularly interested in the photos snapped by the Abu Ghraib guards, and they provoked him to his lengthy New York Times blog essays on the philosophy of photography. S.O.P. and his writings ask how reliable a photograph is, how we can so easily miss what’s before us, and how what’s really happening–the chain of command, the war crimes that aren’t photographed, even another witness–can be hidden by the images we make. He often invokes a soldier’s remark about the Abu Ghraib pictures: “When you see a picture, you never see what’s outside the frame.”

The philosophical quests in Morris’s work lay at the center of Carl Plantinga’s presentation, “Errol Morris and the Anosognosic’s Guide to Documentary Film.” Carl trained as a philosopher, and his lecture teased out many concerns that weave through Morris’s work. On his website, Morris has written about anosognosia, the condition of not knowing that you don’t know something. It’s the realm of Donald Rumsfeld’s “unknown unknowns.” Anosognosia, Morris claims, is “a universal condition of the human race.”

Carl’s talk developed this idea along several lines. Morris, he suggested, is a critical realist who believes that reliable knowledge is in principle attainable, even though we seldom attain it. Accordingly, Carl suggested, the films expose the mistaken beliefs of his subjects, their “epistemic distortions” revealed in behavior and, especially, language.

But the pathway to truth can’t be the cinéma-vérité methods of straightforward recording, if only because simply turning on the camera won’t give us access to the “mental landscapes” his speakers inhabit. For Carl, Morris deals in tragicomedy—sometimes bleak, sometimes absurdist, sometimes tinged with “fellow feeling.” His films can seem denunciatory, but they pause for moments of sympathy: a trial lawyer quits practice when justice is outrageously miscarried, the grunts at Abu Ghraib are scapegoated.

Carl invoked a controversy that has played out in academic circles but that Morris obviously feels passionate about. It centers on The Thin Blue Line. That film, some scholars argued, was a “postmodern” documentary. The conflicting testimony, rambling digressions, and incompatible replays seemed to display a corrosive skepticism about what really happened on the night that Officer Robert Wood was shot on a lonely Texas highway. Morris had apparently made a film about the impossibility of finding truth. Perhaps Morris encouraged that interpretation by remarks like this:

I like the irrelevant, the tangential, the sidebar excursion to nowhere that suddenly becomes revelatory. That’s what all my movies are about. That and the idea that we’re in a position of certainty, truth, infallible knowledge, when actually we’re just a bunch of apes running around.

Since then, though, Morris has been at pains to insist that The Thin Blue Line doesn’t say that arriving at a truth is impossible, only that it’s damnably difficult. Unlike the preformatted rhetorical documentary, a Morris film starts out from an uncertain place and moves into unknown territory. We may not arrive at certain truth or infallible knowledge, but that doesn’t mean that we’re forever floating in a realm in which belief in ghosts is as valid as belief in atoms. Randall Adams did not shoot Officer Wood, and David Harris probably did. Approximate but reliable truths are likely as close as we’ll get, and even those are very hard won. This is one reason Carl calls Morris a “critical realist”: There is a real world and there are true things to be said about it, but there are never any guarantees that we’ll find them.

Hence, again, the figure of the detective. The P. I. searches for the truth. The result may be partial, or vague, or so thickly wrapped in falsehood that it seems a pitiful thing. The trail is cluttered with distractions. With The Thin Blue Line, Morris developed a story line, starting with Randall Adams’ arrival in Dallas and ending with David Harris’s chillingly casual suggestion, captured on tape, that he was the guilty party.

The interviews provided the spine of Morris’s tale. But he embellished the interviews with inserts of documents (newspapers, police records), reenactments, and other images, some of them apparently irrelevant to the case: road maps, a drive-in’s popcorn machine, clips from Boston Blackie movies. In the terms we propose in Film Art, he gave his narrative form doses of associational form.

One function of this vagrant material is to remind us what any private dick knows: You have to sift through a lot of detritus to get to the important facts. (This idea seems literalized in the floating feathers and clumps of dust that irradiate the cell block in S. O. P.) Sometimes the detritus buries the facts, and you miss out. But some inquiries make progress. “It’s not just about constructing stories,” Morris says, “but finding things out.”

Morris’s films aren’t necessarily full records of an investigation but rather soundings and probes. The movies assemble, in provocative form, promising leads, false trails, and clues that are striking but still inscrutable. Sometimes what’s out of the frame is crucial. The viewer of The Thin Blue Line is likely to think that Harris’s climactic half-confession is what won Adams’ reprieve. In fact the decisive material was footage not in the final movie, drawn from interviews with Emily Miller and Michael Randell, along with proof that evidence was suppressed at Adams’ trial. As Morris is fond of saying, “What freed him was not the movie but the investigation.”

The lure of the lurid

Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control.

What amazed me was the number of murderers who’d come from Plainfield and the surrounding areas, so I started interviewing them, too . . . . At the time I remember my mother asking me why I didn’t spend time with people my own age. I said, “But mom, the murderers are my own age.”

Errol Morris

Emphasizing Morris’s search for truths may make him seem a more genteel filmmaker than he actually is. Another side of his work is an unabashed sensationalism. When I said to him, “You’re preoccupied with the weirdness of things,” he corrected me: “No, the profound weirdness of things.” The world is just plain strange (that’s part of what makes truth hard to get to) and it’s strange all the way down.

Morris has an appetite for free-range surrealism. Vernon, Florida began as an inquiry into a town whose citizens displayed a penchant for hacking off their arms and legs. (Pitching a fictional version, Morris proposed the one-sheet tagline: “If they would do this to themselves, think of what they would do to you.”) He has been intrigued by spontaneous human combustion, people struck by lightning, the search for Einstein’s brain, the breeding of giant chickens, and the efforts of a Minnesota man to build his own interstate highway.

At the limit stand figures preoccupied with end-of-life concerns—that is, the ending of other people’s lives. Morris’s time in Wisconsin with Herzog led him to Ed Gein, our state’s most famous grave-robber and the prototype for Norman Bates. Pretending to be psychiatrists, Morris and Herzog interviewed a serial murderer in California. Later, after working as a P. I., Morris heard of “Dr. Death,” a psychiatrist who specialized in testifying to the sanity of convicts on Death Row. A perfect subject for a movie, Morris thought, and checking into Dr. Death’s record he found Randall Adams’ case.

Morris’s cheerfully morbid curiosity, which puts him in the company of Dr. Hunter S. Thompson, Ed Regis, and, of course, Herzog, is channeled into subjects that a high schooler might choose for a book report. Baby-boomer men, brought up on the Hardy Boys and Popular Science, are perpetual kids. Anything to do with magic, mystery, snooping, and weird science holds us fascinated. I’d bet that Morris has a set of William Poundstone’s wondrous Big Secrets books. How did he miss tackling UFOs?

So Morris is a connoisseur of weird science and lethal battiness. But it’s all in a day’s work for a P. I. The detective is inevitably drawn to seaminess, curiosities, and compulsions. Things that shock or disgust or baffle us can be clues to something we’d rather not face. In Morris’s hands, material that would shriek at us from supermarket racks can turn grotesquely comic (the early films), ominous (Thin Blue Line, Mr. Death), or strangely poetic (A Brief History of Time; Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control).

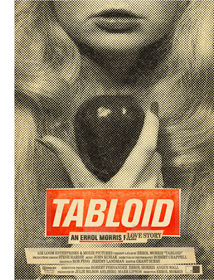

Come to think of it, Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control would also be a good title for Tabloid. Joyce McKinney’s saga has enough spice for a full issue of Weekly World News: beauty contests, religious mania, kidnapping, bondage, flight from the law, cloned puppies, and Joan Collins. There are moments that demand blunderbuss typeface. I still want my Mormon! He was a doo-doo dipper! Booger gave me five black jellyrolls! And no reenactments now, just interviews enhanced by found footage, snapshots and headlines hurled into the frame. Once we’re dizzied from the bombardment of alluring phrases (Manacled Mormon Sex Slave!), we’re yanked into a circulation battle. The Mirror and the Express are deploying operatives to buy stories that will undercut each other.

Come to think of it, Fast, Cheap, and Out of Control would also be a good title for Tabloid. Joyce McKinney’s saga has enough spice for a full issue of Weekly World News: beauty contests, religious mania, kidnapping, bondage, flight from the law, cloned puppies, and Joan Collins. There are moments that demand blunderbuss typeface. I still want my Mormon! He was a doo-doo dipper! Booger gave me five black jellyrolls! And no reenactments now, just interviews enhanced by found footage, snapshots and headlines hurled into the frame. Once we’re dizzied from the bombardment of alluring phrases (Manacled Mormon Sex Slave!), we’re yanked into a circulation battle. The Mirror and the Express are deploying operatives to buy stories that will undercut each other.

At some point we’re engulfed, and the tabloids become an alternative reality of magical transformations. An innocent girl, radiant in her own home movie, becomes a felon, and then her real transgressions come to light. The tabs’ endless escalation of sordidness, with each week’s scandal trumped by the next, gives the movie its pounding rhythm, the tempo of the rotary presses pumping out—what else?—stories that bury truth under trivia.

Except that this time around, the trivia are all we have, and the obsessiveness of the young McKinney is matched by that of the reporters pursuing her. Captured in pitiless high-definition, the men’s seamed faces glow with self-satisfaction and the thrill of the hunt. True, they’re investigators like Morris, and one journalist elicits some actual conversation with our offscreen filmmaker. (They discuss the phrase “barking mad,” which Morris wishes Americans used more often.) After a while, though, we can add these Grub Streeters to Morris’s gallery of people who talk and talk without any sense of what they’re giving away.

The great mystery

The Thin Blue Line.

Even as [the writer] is worriedly striving to keep the subject talking, the subject is worriedly striving to keep the writer listening. The subject is Scheherazade. He lives in fear of being found uninteresting, and many of the strange things that subjects say to writers—things of almost suicidal rashness—they say out of their desperate need to keep the writer’s attention riveted.

Janet Malcolm

The detective, by vocation, asks questions. A detective-story plot consists largely of following the investigator pounding the path, interrogating witnesses, suspects, and experts. (With time out for occasional pistol ambushes, seductions, and whacks on the back of the head.) What people say and how they say it can lead you to truth, or to the profound weirdness that informs the human condition, or both.

Hence the very special conditions for a Morris interview. Complex lighting, and in the later films artificial backdrops, create the aura of a special occasion. Hair and make-up are attended to. Up to twenty crew members are at work. Looming in front is the Interrotron, that mad-scientist rig of mirrors that lets the interviewee look at Morris while also looking into the camera. In a later development, several cameras are trained on the speaker. In all, it’s not quite like being dragged to sit in the hot seat at Headquarters, but there is an almost ceremonial surrender of autonomy. All the subject can do is talk, and aim it directly at us.

Morris does not provide questions in advance. He starts by saying, “I don’t know where to start.” He doesn’t pounce on his subjects (he calls them his “characters”). He speaks as little as possible, regarding it as best to let the people gabble on. Thanks to videotape, they can talk uninterrupted for hours. We seldom hear his questions. He never comes on camera to make himself the protagonist or star (à la Moore), nor does he provide a stream of voice-over narration (à la Curtis). We have simply to look at these people and listen to what they say.

During his stay in Madison, Morris referred often to the case of Scott MacDonald, the convicted murderer whose case journalist Joe McGinnis turned into a bestseller. Of particular interest to Morris was Janet Malcolm’s book about the case, The Journalist and the Murderer. MacDonald sued McGinnis for seeming to support his case during the trial, then publishing a damning account declaring MacDonald guilty as charged. Analyzing MacDonald’s litigation, Malcolm reflects on the betrayal at the heart of journalistic inquiry. The subject interviewed wants the story told his or her way; the writer, at least the writer of conscience, can never fulfill that pledge. The naivete of the subject is always shattered when the story is published, for the writer had another agenda.

Malcolm’s book intersects Morris’s concerns at several points: a tabloid murder, a man perhaps wrongly convicted, a subject sueing the writer (as Randall Adams eventually sued Morris). In particular, I think that Morris is taken with the idea that interviewees have a kind of compulsion to keep talking. They want to explain themselves fully, of course, and to justify what they’ve done. But they also want to prove themselves worthy of someone else’s interest. Compulsive confessors, they want to be caught and are always startled when they are.

Morris’s ultimate interest, Carl Plantinga noted, lies in people’s “mindscapes,” their private construals of reality. Morris seemed to agree. The great mystery, he said, is “human personality, who we are.” That includes all the madness and dirt. The surprises that pop out, Interrotron or no Interrotron, remind us that we’ll never completely crack the case.

For much more on Morris, visit his website. He tweets here. His New York Times essays on photography are now evidently behind a paywall, but an all-out search will reveal some of them. Here is a pdf of what I think is the first one. A more recent cycle starts here. A book of Morris essays is planned for publication.

The best compendium of Morris’s evolving ideas is Livia Bloom’s collection Errol Morris Interviews (University of Mississippi Press, 2010). From this book, I’ve quoted Morris’s remarks in Chris Chang’s 1997 Film Comment article “Planet of the Apes,” p. 56, and in Paul Cronin’s wide-ranging “It Could All Be Wrong: An Unfinished Interview with Errol Morris,” p. 165. My quotation from Janet Malcolm’s The Journalist and the Murderer is from pp. 19-20.

Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film has recently come back into print, and I discuss it briefly in a recent entry.

I wrote an analysis of The Thin Blue Line in Film Art, ninth edition, pp. 425-431. We contrast Morris with Michael Moore and other documentarists in Film History: An Introduction, third edition, pp. 544-548.

The Wisconsin symposium, Elusive Truths: The Cinema of Errol Morris, was a model of campus cooperation. Thanks to the Wisconsin Union, and especially the dedicated students of the WUD Distinguished Lecture Series, the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, our Cinematheque, the University of Wisconsin Foundation, the UW Arts Institute, and other agencies, not least my home Department of Communication Arts. We owe a special debt to Professor Vance Kepley who orchestrated the event with aplomb. A full record of events, sponsoring bodies, and people to be grateful to can be found here.

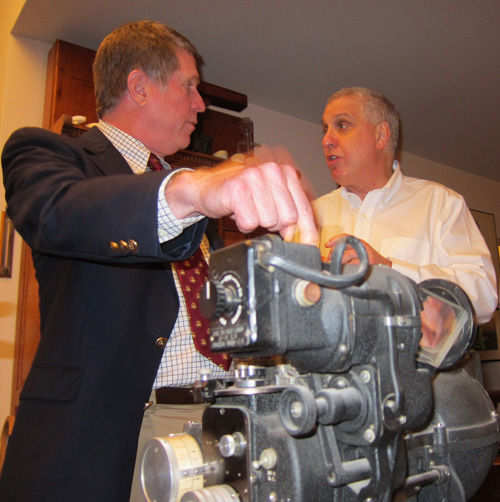

Vance Kepley and Errol Morris discuss the once-top-secret Norden bombsight.

A last celluloid banquet from Vancouver

Detail from “Crimson Autumn” (1931) by Ural Tansykbaev (from The Desert of Forbidden Art)

Kristin here:

A Film Unfinished (Israel; dir. Yael Hersonski, 2010)

A Film Unfinished satisfies on many levels. It is based on several reels of an unfinished Nazi propaganda film labeled “The Ghetto,” discovered among an archive of thousands of cans of Nazi footage. On a simple documentary level, the scenes in the film show precious evidence of life in the Warsaw ghetto in the 1941-42 era, before most of its inhabitants were sent to death camps. As a piece of historical research on the part of the filmmakers, who found written and taped material that shed considerable light on this mysterious footage, it  comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

The samples from the silent footage shown early in A Film Unfinished show a strange combination of subject matter. Apparently candid footage of people in the street, going about their daily lives, is mixed in with scenes of well-dressed men and women in restaurants or elegant apartments. How do these incongruous scenes fit together?

The filmmakers found extensive diaries kept by one of the officials in charge of the Ghetto, as well as taped testimony given in 1961 by one of the main cameramen who recorded the footage. Passages from these, read over additional footage from the film,gradually reveal at least part of the purpose behind the footage. The Nazis apparently wanted to show that some inhabitants of the ghetto were living a normal, even luxurious life (above left). But other scenes were shot showing these same people on sidewalks. Beggars pass by them, but the actors playing the well-off Jews were instructed to ignore them. The result would  presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

The filmmaking process frequently intrudes. Apart from the voiceover readings from witnesses to the filming, there are occasional glimpses of cameramen in the backgrounds of scenes (left). Moreover, one reel of the rediscovered film turned out to be unedited takes of several brief sequences, showing retakes of the same footage. Thus an apparently candid shot of two little boys looking into a shop window abundantly stocked with food turns out to have been staged; we even get a glimpse of one of the filmmakers leaning into the shot to direct the boys. A scene of police clearing a crowded street was done by assembling a large group of Jews and then having the police drive people away (the scene at left being part of that action). Urgency was added when the filmmakers fired shots into the air to frighten the crowd.

An added layer was given to A Film Unfinished by assembling a small group of men and women from the ghetto who witnessed many of the events. They are seen watching the film and adding comments. One remembers having seen the filming. Another worries that she will see someone she once knew among the faces on the screen. The presence of these witnesses emphasizes the fact that what we are watching in the rediscovered footage is both an elaborately staged series of events and a grim record of reality in the ghetto. A particularly grim sequence shows men with a handcart gathering corpses from the sidewalks (where helpless relatives, without any other recourse, dumped them overnight). These are taken to a mass grave, where they are stacked like firewood, covered with sheets of paper, and buried. Though the men working at this grisly task were clearly told what to do by the filmmakers, the fact remains that this gathering and disposing of bodies was a routine that went on daily in the late days of the ghetto.

A Film Unfinished would be very useful in a class on documentary cinema.

The Desert of Forbidden Art (Russian/USA/Uzbekistan; dir. Tchavdar Gorgiev and Amanda Pope, 2010)

Our interest in 1920s and 1930s Soviet avant-garde art led David and me to this film. It reveals the remarkable, unknown work of Igor Savitsky, a Russian Russian archaeologist who discovered the culture and art of the Karakalpakstan region of Uzbekistan. Applying for government funds to create the Karakalpak Museum of Arts, Savitsky initially stocked it with the jewelry, costumes, pottery, and other local cultural artifacts that were discouraged by the Soviet modernization policy.

He also discovered that there were many hidden paintings and drawings by artists whose avant-garde tendencies had gotten them into trouble with the central Soviet government in the Stalinist era. In 1966 he secretly–and very illegally–began using government money to buy up whole caches of these works. By the time of his death in 1984, he had acquired around 44,000 of them! Many are still in storage, awaiting restoration, but the galleries of this remote museum are full of extraordinary, hitherto unknown artworks.

The Desert of Forbidden Art is informative not only about the history of Savitsky and the museum, but it reveals something of the current culture of this isolated province, a culture which figures prominently in the artworks as well. Sons and daughters of the artists appear on camera, as does Marinika Babanarzorova, the museum’s current director. Naturally many beautiful artworks are on display as well.

The film touches only briefly on the fact that these artworks have been hidden away in a remote desert area which is also increasingly under the sway of Islamic extremism. A few documentary shots show the dynamiting of ancient rock-cut Buddha statues in adjacent Afghanistan in 2001. The head of the Nukus Museum was invited to appear with the film at the VIFF, but she was unable to get permission to leave the country. One is left wondering whether these artworks will need to be rescued anew.

The film is screening widely at film festivals and societies, mostly in the USA but in a few other countries as well. See its website for a schedule of upcoming showings. It also will be run in April or May, 2011 in the PBS series “Independent Lens.”

Certified Copy (France/Italy/Belgium; dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

This was the film I was most looking forward to at the festival, and it was the last–and best–one I saw. As usual, Kiarostami has come up with a novel approach to storytelling. (See David’s entry on Shirin.) After only one viewing, I’m not confident enough to say much about Certified Copy. Besides, almost anything I say about the plot will give away too much. This is a puzzle film that unfolds very slowly and very subtly.

It seems to work in ways almost opposite to those of the big puzzle film of the year, Inception. That film was almost all exposition, which we had to frantically note and try to piece together to get even a rough grasp of the plot. Certified Copy has almost no exposition–or none that we can recognize immediately or even trust when we do recognize it. I could gauge how slowly that recognition comes by the fact that the laughter at apparently incongruous behavior between the characters gradually faded. Different members of the audience realized at different moments that what had seemed incongruous maybe wasn’t after all, though it’s possible that the incongruity was just increasing right up to the end. Close to the end, only a lady two rows behind me was still laughing.

Essentially what happens is that a plot unfolds, and despite a lack of solid information, most of us probably infer from the conversations enough to assume we understand the two main characters and their relationship. Eventually their actions suggest that perhaps an entirely different plot and relationship has been unfolding all along. (This comes fairly late in the film, in maybe the last third or even quarter.) Perhaps the information we receive does not allow us to decide in this ambiguous situation, though I think people do tend to decide. I decided one way, David decided the other.

Interestingly, this mirrors in longer form the last sequence of Under the Olive Trees. There we are not told what the girl replies when the boy runs after her and proposes marriage one last time. In that case, too, I decided one way, David the other. Years ago we told Kiarostami this, and he laughed and said men tend to assume the girl accepts him, while women assume she rejected him. (I think there actually are some fairly clear clues earlier in the film that she will reject him, but explaining those would be a different entry.) That may be the case here, that men and women will reach opposite conclusions.

On the other hand, and this would require at least a second viewing, the film may remain utterly ambiguous about which plot is “real.” Or it may even stray into the territory of the inexplicable, à la Buñuel or David Lynch, where the difference parts of the story are each “true” but incompatible. M. Tsai suggests, “‘Certified Copy’ plays out a bit like a romantic comedy directed by David Lynch with its distinct two-halves connected by a thread.” (Not to be read until you’ve seen the film.)

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

For many links to articles and reviews, see David Hudson’s helpful wrap-up on Mubi. (Again, not until you’ve seen the film.)

Sodankylä Forever (Finland; dir. Peter von Bagh, 2010)

DB here:

Do writers write books about fanatical readers? Do composers write operas about opera lovers? Sometimes, but not to the degree that cinephiles delight in making films about their passion. Case in point: Peter von Bagh’s Sodankylä Forever. The Festival screened two films devoted to Finland’s Midnight Film Festival, which not only runs movies around the clock but hosts marathon interviews with filmmakers.

It isn’t your usual red-carpet event. The town is tiny. Guests are treated to campfire cookouts and invited to play soccer. But watching old clips, catching snatches of the Johnny Guitar theme, and hearing revered directors spin their yarns is enough to bring pleasure. There are moments of drama—Zanussi and Makavejev boycott a screening of Potemkin because of its “totalitarian” ideology—but mostly the filmmakers muse in a relaxed fashion about the good, and bad, old days.

The Yearning for the First Cinema Experience treats a core cinephile topic: What was your earliest encounter with the movies? Disney films, as you might expect, play a major role, but so too does Frankenstein (which made Victor Erice realize that people kill other people) and even the MGM lion (which startled Kiarostami in his childhood). The First Experience includes more mature epiphanies, such as Bob Rafelson’s obsessive visits to Manhattan’s Thalia. If the official classics get particular attention, it’s perhaps because, as Costa-Gavras says, “Everything was done in the silent cinema.”

So cinephiles are nostalgists, sentimentalists, even narcissists. But we aren’t oblivious to history behind the screen. The Century of Cinema episode focuses on directors’ relation to World War II (a continuing fascination of von Bagh’s). An era of purges, battlefront savagery, and prison camps, created, Szabo reflects, “a generation without fathers.” Jancsó, who served time in a Finnish POW camp, pays tribute to his hosts with a recitation, in Hungarian, of the opening of the Kalevala.

After the war, however, several Western European directors recall the advent of a new era of intelligence and creative engagement. The spirit was most apparent in the Italian Neorealist films. Erice tells of sneaking a forbidden print of Rome, Open City out of customs so that Spanish cinephiles could see it. In Eastern Europe, of course, things were different, and tales of censorship and young directors’ struggle to innovate are treated as continuations of wartime crises and constraints. Alexei German sums up the status of the artist who refuses to affirm official culture: “We are not the doctors, we are the pain.” Samuel Fuller, who has already explained that being assigned to a rear-guard unit in a retreat is a death warrant, is given the epilogue. He recalls visiting the tidiest graveyard he has ever seen and turning to watch the wind rustling the grass. Was he imagining how the scene would look on film? Naturally, arch-cinephile von Bagh shows us.

DB, Abbas Kiarostami, KT. Chicago, March 1998.

The buddy system

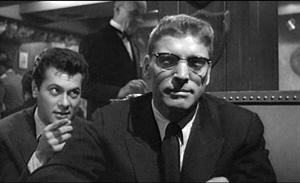

Sweet Smell of Success.

DB here:

Many of our friends write books, and what are friends for if not occasionally to promote each other’s books? Here’s an armload of titles, most of them recently published. They’re so good that even if the authors weren’t our friends and colleagues, I’d still recommend them.

James Naremore has made major contributions to film studies since his fine monograph on Psycho, published way back in 1973. That book remains one of the most sensitive analyses of this much-discussed movie. Now he has another monograph, on the stealth classic Sweet Smell of Success. When I was coming up, Alexander Mackendrick wasn’t much appreciated, and this movie slipped under the radar. More recently it has emerged as one of the model films of the 1950s, and not just for James Wong Howe’s spectacular location cinematography. It’s a very brutal story, with Tony Curtis playing against type as venal press agent Sidney Falco and Burt Lancaster as J. J. Hunsecker, a monstrously vindictive newspaper columnist.

Jim’s book provides a scene-by-scene commentary but also more general analysis of production circumstances and directorial technique. An enlightening instance is what Mackendrick called “the ricochet”—when character A talks to character B but is aiming at character C. This allows the filmmaker great flexibility in framing and cutting, often showing C’s reactions while we hear the dialogue offscreen. In the shots surmounting this blog, Sidney is needling J. J. by asking the Senator if he approves of capital punishment. Jim’s book joins his work on Welles, Kubrick, and film noir as part of a subtle reassessment of American postwar cinema.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

With the current revival of interest in André Bazin’s film theory, it’s fruitful to look again at the “classical” theoretical tradition in which he participated. “Classical” here refers to the very long period before the emergence of semiotic and psychoanalytic theories of cinema in the 1960s. The newer theories have somewhat beclouded our recognition of how imaginative and wide-ranging the old folks were. In Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition, Malcolm Turvey scrutinizes four thinkers who saw film as having the power to show us things beyond (or above, or below) surface reality. In the spirit of analytic philosophy, Turvey carefully lays out the positions of Béla Balázs, Jean Epstein, Siegfried Kracauer, and Dziga Vertov before asking whether their claims hold up.

I’m not giving much away by revealing that Malcolm thinks the revelationist tendency has its problems. But his purpose isn’t simply to reject the position. He treats it as an instance of what he calls “visual skepticism,” the idea that we ought to treat our ordinary intake of the world as something suspect. This idea, Malcolm argues, is central to modernism in the visual arts. He extends his critique of visual skepticism to more recent theorists as well, notably Gilles Deleuze, and he shows how his own ideas apply to films by Hitchcock, Brakhage, and other directors. Malcolm’s book is a model of theoretical clarity and probity, and a stimulating read as well.

Skepticism of another sort is central to Carl Plantinga’s Rhetoric and Representation in Nonfiction Film. One result of semiotic theory was to question whether a film could ever adequately represent reality. If a movie is only an assembly, however complex, of conventional signs, it can’t give us access to something out there. Even a documentary, some theorists argued, had no privileged access to the real world, let alone to general truths. “Every film is a fiction film” was a refrain often heard at the time. Carl tackles this assumption head-on by carefully arguing that just because a documentary is selective, or biased, or rhetorical, that doesn’t mean that it can’t affirm true propositions about our social lives.

Like Malcolm, Carl brings a philosopher’s training in conceptual analysis to debates about the ultimate objectivity of any documentary. In adopting a position of “critical realism” opposed to skepticism, Carl examines the realistic status of images and sounds, the way documentaries are structured, and filmmakers’ use of technique. He shows, convincingly to my mind, that a documentary may offer an opinion and still be objective and reliable to a significant degree. Carl’s 1997 book went out of print before it could be published in paperback. He has enterprisingly reissued it as a print-on-demand volume, and it’s available here.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

To take film theory in another direction, there’s Evolution, Literature, and Film, edited by Brian Boyd, Joseph Carroll, and Jonathan Gottschall. As a wider audience has become aware of the power of neo-Darwinian thinking, more and more scholars have been arguing that evolutionary theory can shed light on aesthetics. The most visible effort recently is Denis Dutton’s The Art Instinct.

For some years Brian, Joe, and Jonathan have been in the forefront of this trend, with many books and articles to their credit. Their anthology pulls together broad essays on biology, evolutionary psychology, and cultural evolution before turning to art as a whole and then focusing on literature and cinema. There are also pieces displaying evolutionary interpretations of particular works, and a finale that provides examples of quantitative studies of genre, gender variation, and sexuality, including an article called “Slash Fiction and Human Mating Psychology.”

Among the film contributors are other friends like Joe Anderson, a pioneer in this domain with his 1996 book The Reality of Illusion, and Murray Smith, who provides an acute piece called “Darwin and the Directors: Film, Emotion, and the Face in the Age of Evolution.” There are also essays of mine, drawn from Poetics of Cinema. In all, this book presents a persuasive case for an empirical, broadly naturalistic approach to the arts.

By the way, the same team is involved with an annual, The Evolutionary Review, edited by Alice Andrews and Joe Carroll. Its first issue offers articles on Facebook, musical chills, women as erotic objects in film, and Art Spigelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers (by Brian Boyd).

Some books emerge from conferences, and Tom Paulus and Rob King’s Slapstick Comedy is a good instance. Based on “(Another) Slapstick Symposium,” held at the Royal Film Archive of Belgium in 2006, the anthology brings together a host of experts who look back at madcap comedy in American silent film. There are essays on particular creators—Griffith, Sennett, Fatty, and Chaplin, inevitably—as well as pieces on slapstick parodies of other movies and the genre’s relation to modernity, also inevitably. Tom Gunning offers a fine analysis of Lloyd’s Get Out and Get Under (1920), concentrating on a complex string of gags around an automobile. The collection gathers work by some of the outstanding scholars of silent film while also, of course, making you want to see these crazy movies again.

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

You also want to see all the movies lovingly evoked by Gary Giddins in Warning Shadows: Home Alone with Classic Cinema. As indicated in another blog entry, I find Giddins one of the best appreciative critics we’ve ever had. Any essay, indeed almost any sentence, cries out to be quoted. Here he is on Edward G. Robinson:

His round, thick-lipped, putty face could brighten like paternal sunshine or shut down in implacable contempt or stall with crafty desperation or pontificate with ingenuous wisdom; his short, stumpy, erect frame could sport a tailor-made as smartly as Cary Grant.

Some of the pieces in Giddins’ latest collection were designed to accompany DVDs, but they will outlast this evaporation-prone genre. Other reviews come from the New York Sun, which gave him freedom to mix and match his subjects: Young Mr. Lincoln and Lust for Life (both biopics), Lady and the Tramp and Miyazaki movies. The collection opens with Giddins’ thoughts on how changes in film exhibition, from nickelodeons to digital screens, have altered our relationship with the movies. This isn’t just nostalgia, because his survey allows him to celebrate the power of DVD to exhume forgotten titles. The standards for a film classic, he notes, “are gentler and more flexible” than those in appraising other arts. “The passing decades are a boon to the appreciation of stylistic nuance that gives certain melodramas and genre pieces the heft of individuality.”

Who was Segundo de Chomón? In the 1970s, I kept finding that films I thought were by Méliès turned out to bear this mysterious signature. You imagine a man in a cape and a floppy hat. Photographs show someone a little less operatic, but with a superb mustache. Today he’s far from a mystery, although many of his movies can’t be fully identified. Several scholars have followed his trail, none more thoroughly than Joan M. Minguet Batllori in Segundo de Chomón: The Cinema of Fascination.

Chomón started as a cinema man-of-all-work in Barcelona, translating film titles, distributing copies, and producing films for Pathé. After moving to Paris in 1905, he continued working for the company and established his fame with trick films. He returned to Barcelona to create a production company, but that failed. On he went to Italy, where he specialized in visual effects, most famously for Cabiria (1914).

In his Parisian Pathé years, he was in charge of all the studio’s trick films, which included not only stop-motion, superimpositions, and other effects but also marionettes and animation. Joan argues that he was a prime exponent of the “cinema of attractions,” Tom Gunning’s term for that early mode of filmmaking which aims to startle and enchant the audience. A famous instance is Kiriki, acrobats japonais (1907), which shows gravity-defying stunts.

Chomón accomplished this by shooting from straight down, filming the performers on the floor. They had to simulate leaps and flips as they rolled along each other’s bodies, and then they had to slip perfectly into position. This English edition of Joan’s book on Chomón, full of information and providing a “provisional filmography” along with many pages of gorgeous color images, will be available soon here.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

We recently noted the anniversary of our book on classic studio cinema, a 1985 project in which we bypassed talking about exhibition. That part of the industry has been a scholarly growth area in the years since, and one of the newest yields is Epics, Spectacles, and Blockbusters: A Hollywood History, by Sheldon Hall and Steve Neale. It’s a chronological account of Big Movies, from the earliest features to the digital era, and it concentrates on how such films have been marketed and shown. It explains how exhibition changed across the decades, and how we got the phenomenon of the “roadshow” movie, the film shown selectively (only certain cities), at intervals (perhaps only one matinee and one evening screening), and at more or less fixed prices. My middle-aged readers will remember roadshow releases like The Sound of Music (1965), although there were many before and even a few since.

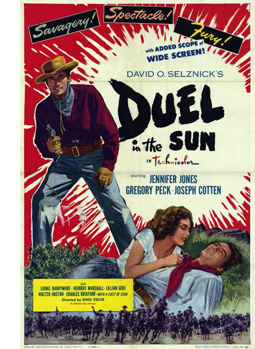

Sheldon and Steve trace in unprecedented detail the cycles of blockbusters that have run throughout American cinema. In the process they refreshingly redefine the very idea. We don’t usually think of The Best Years of Our Lives as a Big Movie, but it runs three hours and was considered a “special” production, comparable to the more obvious sprawl of Duel in the Sun. The authors bring the story up to date by considering today’s event movies as a “Cinema of Spectacular Situations.” Yes, that category includes comic-book films, Inception, and, of course, the 3D sagas that may finally be wearing out their welcome. (My editorializing, not theirs.)

Japanese cinema is endlessly fascinating in all its eras; I’d argue that in toto it’s one of the three greatest national cinemas in film history. The postwar period is exceptionally interesting because of the American occupation (1945-1951) and its effects on Japanese film culture. This period has already provoked one of the best books we have on Japanese cinema, Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo, and it finds a worthy accompaniment in Hiroshi Kitamura’s Screening Enlightenment: Hollywood and the Cultural Reconstruction of Defeated Japan. Kyoko focused on how US policy shaped domestic filmmaking, while Hiroshi asks how the Occupation helped American studios penetrate the local market.

Over six hundred Hollywood movies poured into Japan during the period, and Hiroshi traces how local tastemakers as well as U.S. policymakers drew audiences to them. Young Japanese learned about the Academy Awards, assembled in movie-study clubs to discuss what they were seeing, and were urged to consider even a gangster tale like Cry of the City (1950) as demonstrating the humanistic side of democracy. A center of this activity was Eiga no tomo (“Friends of the Movies”), a magazine that went beyond entertainment news and tried to reshape the tastes of young people. In sharp prose and vivid evidence, Hiroshi captures the ways in which American cinema promised to help heal a devastated country.

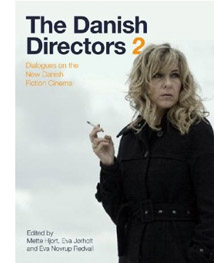

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

The Danish Directors, by Mette Hjort and Ib Bondebjerg, has become a standard companion to the most successful “small cinema” on the European scene. Now it has a successor in The Danish Directors 2: Dialogues on the New Danish Fictional Cinema, edited by Mette, Eva Jorholt, and Eva Novrup Redvall. Once again, we get lengthy, in-depth interviews covering the value of film education, the vagaries of funding, and filmmakers’ creative decision-making. Lone Scherfig, Christoffer Boe, Per Fly, Paprika Steen, and many other major figures are included. (Disclosure: The editors were kind enough to dedicate the book to me.)

While the first volume is a rich storehouse of information on Danish film in “the Dogma era,” the newest volume shows how directors (some of whom made Dogma projects) have gone beyond it. In preparing 1:1, a film about Danes and Arab immigrants living in a housing project, Annette K. Olesen had a full script but concealed it from the non-professional cast. After getting the performers comfortable with ordinary situations, she began staging scenes while encouraging improvisation. Screenwriter Kim Fupz Aakeson incorporated the improvised material into revisions of the script.

By contrast, the prolific director-screenwriter Anders Thomas Jensen (Adam’s Apples, The Green Butchers), relies on strong structure, with lean expositions and sharply defined climaxes. He appreciates clean filming technique too.

It’s easy to make something that’s ugly and handheld, but you have to take telling stories with images seriously. You have to take the language of film seriously. Many Danish directors have started doing this in recent years and it’s wonderful, because there was a time when everything looked Dogma-like and I found myself thinking, “It’s got to stop now.”

To those who think that Danish cinema is at risk of becoming a cinema of cozy liberal reassurance, this collection offers many salutary signs. Every director speaks of the need to keep innovating, to push ahead provocatively. Simon Staho, whose Day and Night seems to me one of the most adventurous Danish films of recent years, aims at utter purity: “My task is to figure out how to add as little as possible to the black screen. The damned problem is that you have to add image and sound!”

What makes all these books exciting to me is a willingness to test ideas–sometimes very general ones–about cinema and the wider world by examining film as a distinctive art form. Even the most conceptual books on this week’s shelf are firmly rooted in the particular choices that creators make and the concrete ways that viewers respond.

Next stop: Vancouver International Film Festival. Whoopee!

Day and Night.

Ledoux’s legacy

DB here:

Every summer Brussels hosts one of the world’s most unusual film festivals. By global standards it’s a small event: it showcases only twenty or so titles, each screened twice. The films are on the whole unknown. The prizes are minuscule by the million-plus benchmarks set by Dubai and Abu Dhabi. The venue stands behind an inconspicuous doorway. Yet for me it’s an unmissable event, a crucial influence on my thinking about film and my search for cinematic satisfaction.

Jacques the gentle

Young Murderer (Seishun no satsujin sha, 1976).

Between 1948 and his death in 1988, Jacques Ledoux was the curator of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium. He made it into one of the cinema’s legendary places, at once Mecca and Aladdin’s cave. On remarkably small budgets, he assembled broad and deep collections. He bought many titles for distribution to local cinemas and schools. He created a public screening program that for decades has shown five different films (two of them silents), every day of the year. The year Ledoux died he received an Erasmus Prize for his services to European culture.

His early life could have come out of an East European movie. Born in Poland in 1921, he fled to Belgium to escape the German onslaught. He hid in several places, including a monastery. There the abbot gave him work publishing Benedictine books. In the abbey’s screening room Ledoux discovered a copy of Nanook of the North. He offered it to the just-started Belgian Cinémathèque, and its supervisor, the filmmaker Henri Storck, offered Ledoux a job. Finding film archivery more appealing than studying science and medicine, he stayed with the Cinémathèque. Interestingly, “Jacques Ledoux” was a pseudonym; one translation is Jacques the Gentle.

Not always gentle Jacques in his scraps with other archivists and local politicians, Ledoux pledged himself to filmmakers, audiences, and—a rarity at the time—overseas film scholars. New Wave directors and Parisian critics made railway pilgrimages to Brussels to see films unavailable in France. When Kristin and I started doing research in the archive in the 1979, Ledoux welcomed us and guided us to treasures we hadn’t known existed.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

Unlike the very public Henri Langlois, Ledoux worked best behind the scenes. Probably most cinephiles today know him only from his brief appearance as one of the sinister experimentalists in La Jetée (1961). He resisted being photographed, and he refused to wear a necktie. Unsurprisingly, he admired directors who strayed from the beaten path. He created the first festival of experimental cinema at Knokke-le-Zoute, in 1949.

His desire to widen everyone’s knowledge of cinema found another outlet when he created the Prix l’Age d’or/ Prijs l’Age d’or in 1958. It was aimed to reward, as Ledoux put it, “a film that, by questioning taken-for-granted values, recalls the revolutionary and poetic film of Luis Buñuel, L’Age d’or.” Ledoux wanted to encourage a cinema that was subversive in both content and form.

The first prizes were given within the framework of the Knokke event: in 1958, to Kenneth Anger; in 1963, to Claes Oldenberg; in 1967 to Martin Scorsese (for The Big Shave). In 1973, the prize assumed something close to its current form. Several films were screened for the public, and the award, now in the form of cash, was decided by a jury system. The first winners were W. R.: Mysteries of the Organism (in 1973); Borowczyk’s Immoral Tales (1974); Raul Ruiz’s Expropriation (1975); Angelopoulos’ Traveling Players (1976); Hasegawa Kazuhiko’s Young Murderer (1977); and Antoni Padros’ Shirley Temple Story (1978).

The winners emerged from a vast and powerful field of competition. In 1973, the first formal year of L’Age d’or, there were sixty-nine films screened, including Aguirre, the Wrath of God, Oshima’s Ceremonies, Paul Morrissey’s Heat, Tout va bien, and works by Rosa von Praunheim, Wim Wenders, and Miklós Jancsó. There was even The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, but Buñuel didn’t win a prize named after his own film! The number of titles dropped a little as the years passed, but it’s good to know that in 1978 Assault on Precinct 13, Eraserhead, Perceval le Gallois, and films by Ruiz, Littín, and Schroeter were in the competition.

Ciné-Discoveries

City of Sadness (Hou Hsiao-hsien, 1989); screened at Cinedécouvertes 1990.

Things changed a bit after 1979. The L’Age d’or criteria were modified to identify “films that by their originality, the singularity of their viewpoint, and their style [ecriture] deliberately break from cinematic conformity.” For whatever reasons, hard-edged subversive cinema was harder to come by. In the meantime, the Prix was absorbed into a broader festival Ledoux launched in 1979, Cinédécouvertes.

Cinédécouvertes became a “festival of festivals.” It culled its selection from films that had been screened at Rotterdam, Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and other events. What set Cinédécouvertes apart was its determination to expand film culture. All the films on the program had no Belgian distribution. Each cash award (today, two of 10,000 euros each) would go not to the filmmaker but to a distributor willing to pick up the film. This is a very tangible way to help films of quality find a local audience.

Over the last ten years, Cinédécouvertes has awarded prizes to Audition, Chunhyang, Werckmeister Harmonies, Oasis, Tropical Malady, Day Night Day Night, Mogari no Mori, Afterschool, and Police, Adjective. The L’Age d’or prize has been given to Aoyama’s Eureka, Reygadas’ Japón, Encina’s Hamaca Paraguay, Balabanov’s Cargo 200, and several others. Not every film has been picked up for local distribution, but the impulse to elevate films that go beyond the obvious festival favorites has continued. Ledoux’s successor as curator, Gabrielle Claes, has maintained the legacy of L’Age d’or and Cinédécouvertes. The July festival flourishes in the Cinematek’s newly rebuilt complex and in its other venue, the lovely postwar-moderne building in the Flagey neighborhood.

The annual Brussels event helped me find my way through modern cinema. There I saw my first Kiarostami (Where is My Friend’s Home?), my first Tarr (Perdition), my first Hou (Summer at Grandpa’s), my first Oliveira (No; or, the Vainglory of the Commander), my first Sokurov (The Second Circle), my first Kore-eda (Maborosi), my first Panahi (The Mirror), my first Jia (Xiao Wu). The Cinematek’s talent-spotters were quick to find many of the most important filmmakers of the 1980s and 1990s, and I’ll be forever grateful for their acumen. After I saw these films and many others here, my ideas about cinema got more cogent and complicated. My life got better, too.

Now most of these filmmakers find commercial distribution in Belgium, so Gabrielle’s scouts must scan new horizons. This year as usual Cinédécouvertes boasted some familiar names like Iosseliani, Wiseman, Guzman, and the eternal troublemaker Godard. But there are also filmmakers from Costa Rica, Sri Lanka, Ireland, Peru, Colombia, and Ukraine. The landscape of film is vast, as Ledoux always reminded us, and a small festival can nonetheless open windows wide.

Mind games, or just games

Elbowroom.

Psychology is at the center of festival cinema. Deprived of car chases and exploding buildings, arthouse filmmakers try to track elusive feelings and confused states of mind. That this can be dramatically engaging in quite a traditional way, as was shown by one of the Cinédécouvertes winners, How I Ended This Summer.

Director Aleksei Popogrebsky puts two men on a desolately beautiful island in the Arctic. They’re initially characterized by the way they execute the routines of measuring weather conditions. Sergei, the stolid older one, is soaked in the ambience of the place, enjoying fishing and boating while insisting on exactness in the log. Pasha is a summer intern, a little careless because he’s exhilarated by the atmosphere: he’s introduced first taking a Geiger-counter reading but then hopping and racing along a cliff edge to the beat of his iPod.

Soon, though, Pasha must give Sergei a piece of bad news that comes in over the radio. Out of awkwardness, fear, refusal of responsibility, and other impulses, he avoids telling his mentor. The consequences are unhappy for each. The film takes on the suspense of a thriller, with conflicts surfacing in a cat-and-mouse game at the climax. Yet before that, more subtly, we have watched several tense long takes of Pasha’s face as he tries to cover up his failures. Not surprisingly, How I Ended This Summer won one of the two Cinédécouvertes prizes. It is an engrossing case for character-driven, locale-sensitive cinema.

Elbowroom tackles psychology from a more opaque and disturbing angle. With no exposition or backstory, we’re plunged into an institution for the handicapped. During the first ten minutes, without dialogue, a handheld camera lurks over the shoulder of a young woman who tries with twisted fingers to apply lipstick. Soon she is preparing to have sex with another inmate, and after their liaison she is whacking her feeble roommates, who sob under her blows. Eventually we’ll recognize this introduction as a summary of her days: fighting with others, being coaxed or berated by staff, meeting her lover, and taking up cleaning tasks. Only far into the film will we learn about how she got here and what her fate will be.

Soohee, stricken with cerebral palsy, is played by a young woman with a milder disease. Very often the camera doesn’t let us see her face, fastening instead on a ¾ view from behind. This seems to me partly a matter of tact, but its ultimate effect is to force us to infer Soohee’s state of mind from her behavior. The visual narration remains resolutely outside the character. Psychology gets reduced to gestures— spasmodic smearing of lipstick, the clasping of a necklace, the seizure of a baby doll (with which she’s bribed). Only at the end does a long held close-up of Soohee’s twitching, smiling face give us fairly direct access to her feelings. Despite the smile—which can be read as a sort of perverse victory for her—Soohee isn’t the noble victim; we’ve seen her petty and selfish side already.

This trip into a world most of us haven’t seen before is presented without conventional pieties, and it’s unsettling. Elbowroom, Ham Kyoung-Rock’s first feature, offers the sort of challenge to aesthetic and moral conventions that the L’Age d’or Prize was designed to encourage. The film won it.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Characters’ psychological developments can also be brought out by parallel construction. A willful little girl and a scientist cross paths in Paz Fábrega’s Cold Water of the Sea. Karina is on a beach holiday with her family and insists on wandering off at intervals. Marianne is a medical researcher, here for a vacation with her boyfriend. When Marianne finds Karina asleep along the road one night, the girl claims that her parents are dead and that her uncle abuses her. But next morning she’s gone, and fears for her safety are only the first of several anxieties that haunt Marianne’s holiday. While Karina incessantly bedevils her mother and makes mischief with other kids, Marianne descends into ennui as she watches her boyfriend devote his time to selling a piece of family property.

Once more Rossellini’s Voyage to Italy proves to be a template for festival cinema. What is wrong with Marianne goes beyond her diabetes: she feels bored and useless. But while Rossellini adhered primarily to the viewpoints of his dissolving couple, Fabrega opens out the portrayal of upper-class anomie by intercutting episodes from the lives of working-class families. The film has two fully-developed protagonists, with Karina’s verve balancing Marianne’s increasing torper. Splitting his story allows Fabrega to make some social points (the family camps on the beach, the couple stays in a motel with a scummed-over swimming pool) and to suggest secret affinities between the little girl and the professional woman. Cold Water of the Sea seemed to me an honorable effort to let some air into the premises of the standard portrayal of a cosmopolitan couple’s ennui.

Parallels likewise form the core of Otar Iosseliani’s Chantrapas, another of his celebrations of shirkers, layabouts, con artists, and free spirits. The title is Russian slang for a disreputable outsider (derived from the French ne chantera pas, “won’t sing”). Here the outsider is Kolya, a young Georgian director who turns in a movie that can’t pass the censors. He emigrates to Paris, where he finds an aging producer (played by Pierre Etaix) eager to tap his talent. But the new project’s backers try to take over the project in scenes deliberately echoing the ones of Party interference.

Chantrapas lacks the shaggy intricacy of Iosseliani’s “network narratives” like Chasing Butterflies (1992) and Favorites of the Moon (1984), the latter of which I enjoyed analyzing in Poetics of Cinema. When we’re given a single protagonist, as in Monday Morning (2002), Iosseliani’s characteristic refusal of motivation, exposition, and introspection creates a more plodding pace. No mind games here. In earlier films, his favorite shot—panning to follow people walking—creates convergences and near-misses and comic comparisons in the vein of Tati. Here the pans serve as merely functional devices, almost time-fillers, and comedy is largely lacking. Still, Iosseliani avoids the easy traps. A Soviet censor bans Kolya’s film, then congratulates him on making such a good movie. When the Parisian preview audience flees the theatre, we can’t call them philistines. Kolya’s movie, despite its stylistic debt to Iosseliani’s own films, looks awful. In the end, even cinema seems less important than smoking, drinking, eating, and, above all, loafing.

It was a documentary, Nostalgia de la Luz by Patricio Guzmán, that won the second Cinédécouvertes prize. It starts as a memoir of Guzmán’s fascination with astronomy, explaining that the unusually clear skies of Chile have attracted researchers who want to probe the cosmos. Because the light from heavenly bodies takes a long time to reach us, Guzmán casts his observers as archeologists and historians: “The past is the astronomer’s main tool.” This is the pivot to the film’s main subject, the search for the disappeared under the US-installed dictator Pinochet.

The analogies rush over us. The enormity of the universe is paralleled by the immensity of Pinochet’s oppression of his country. Captives in desert concentration camps learned astronomy, but eventually they were forced inside at night; the skies’ hint of freedom threatened the regime. Some of the astronomers are friends or relations of the disappeared and see research as therapeutic, putting their personal sufferings in a much more vast cycle of change. Above all there are the old women who patiently scour the desert for traces of their loved ones. A woman tells of finding her brother’s foot, still encased in sock and shoe. “I spent all morning with my brother’s foot. We were reunited.” Scientists try to know the history of the cosmos, and ordinary people tirelessly challenge their government’s efforts to conceal crimes. Both groups, Guzmán suggests, acquire nobility through their respect for the past.

Taking some chances

More formally daring was Totó. This was the first Peter Schreiner film I’ve seen, and on the basis of this I’d say his high reputation as a documentarist is well-deserved. Without benefit of voice-over explanations, we follow Totó from his day job at the Vienna Concert Hall (is he a guard or usher?) to his hometown in Calabria. The film is an impressionistic flow registering his musings, his train travel, and his conversations with old friends, many of the items juggled out of chronological order.

Schreiner avoids the usual cinéma-vérité approach to shooting. Instead the camera is locked down, the framing is often cropped unexpectedly, and the digital video supplies close-ups that recall Yousuf Karsh in their clinical detail. We see pores, nose hair, follicles at the hairline; the seams of sagging eyelids tremble like paramecia. In addition—though I won’t swear that Schreiner controlled this—the subtitles hop about the frame, sometimes centered, sometimes tucked into a corner of the shot, usually with the purpose of never covering the gigantic mouths of the people speaking. All in all, a documentary that balances its human story with an almost surgical curiosity about the faces of its subjects. The Jean Epstein of Finis Terrae would, I think, admire Totó.

I had to miss some of the offerings, notably Oliveira’s Strange Case of Angelica. (Fingers crossed that it shows up in Vancouver.) Eugène Green’s Portuguese Nun was screened, but I’ve already mentioned it on this site. Other things I saw didn’t arouse my passion or my thinking, so they go unmentioned here. Of the remainders, two stood out above the rest for me.

My Joy (Schastye moe), by Sergei Loznitsa, is a daring piece of work. After a harsh prologue, it spends the first hour or so on Georgy, a trucker whose effort to make a simple delivery takes him into the predatory world of the new Eastern Europe. He meets corrupt cops, a teenage hooker, and most dangerously a trio of ragged men bent on stealing his load. After an anticlimactic confrontation, the film introduces a fresh cast of characters, including a mysterious Dostoevskian seer. The film becomes steadily more despairing, culminating in a shocking burst of violence at a roadside checkpoint.

At moments, My Joy flirts with the idea of network narrative. When Georgy turns away from a traffic snarl, the camera dwells on roadside hookers long enough to make you think that they will now become protagonists. One character does bind the stories together: an old man who fought in World War II and who now helps the seer at a moment of crisis. The sidelong digressions, slightly larger-than-life situations, and the floating time periods suggest a sort of Eastern European magic realism. But the whole is intensely realized, at once fascinating and dreadful. After one viewing, I wanted to see it again.

My favorite, as you might expect, was Godard’s Film Socialisme. There are the usual moments of self-conscious cuteness (the zoom to the cover of Balzac’s Lost Illusions, for instance), but on the whole it’s pretty splendid.

Contrary to what a lot of people claim, I don’t think Godard is an “essayist” in most of his films. (Perhaps in Histoire(s) du cinema, but rarely elsewhere.) He tells stories. Granted, they are elliptical, fragmentary, occulted stories, free of expository background and flagrantly unrealistic in their unfolding. Into these stories he inserts citations, interruptions, digressions: associational form gnaws away at narrative. But stories they remain.

The first part of Film Socialisme takes place on a cruise ship. As it visits various ports on the Mediterannean, some passengers learn that a likely war criminal is on board. Then, like Loznitsa, Godard shifts to a new plot. In the French countryside, a garage-owner’s family is invaded by a TV crew. (As far as I can tell from the untranslated dialogue, the son and daughter are purportedly running for elective office.) Finally, in the last eighteen minutes or so, we get pure associational cinema—not an essay, I think, but something like a collage-poem: a busy montage of clips seeking (or so it seems to me) to ask what sort of European politics is possible after the death of socialism.

Andréa Picard has already written a superb commentary on the film, and it would be useless for me, after only two viewings, to try to go much beyond her account. I’d just say that the first two stories show the same sort of ripe visual imagination we have come to expect from late Godard. The images are oblique and opaque, framed precisely but denying us much in the way of story information. Who are these people? Who’s related to whom? (Who are the women apparently linked with the mysterious Goldberg?) More concretely, who’s talking to whom?

Godard cuts among images of varying degrees of definition in a manner reminiscent of Eloge de l’amour, but here color is paramount. We get saturated blocks of blue sky and blue/ turquoise/ charcoal sea. See the image further above, or this one, which is virtually a perceptual experiment on the ways that color changes with light and texture.

Anybody with eyes in their head should recognize that such shots show what light, shape, and color can accomplish without aid of CGI. They aren’t simply pretty; they’re gorgeous in a unique way. No other filmmaker I know can achieve images like them. We also get entrancing scatters of light in low-rez shots in the ship’s central areas and discotheque.

Just as noteworthy from my front-row seat was Godard’s almost Protestant severity in sound mixing. For the first twenty minutes or so, the sound is segregated on the extreme right and extreme left tracks, leaving nothing for the center channel. We hear music on the left channel and sound effects on the right, or ambient sound on one side and dialogue on the other. The result is a strange displacement: characters centered in the screen have their dialogue issuing from a side channel. Sometimes a sound will drift from one channel to another and back again, but not in a way motivated by character movement (“sound panning”). Having accustomed us to this schizophrenic non-mix, Godard then starts dropping a few bits into the center channel. But for the bulk of the shipboard story, that region is largely unused.

We leave the ship with a title, “Quo Vadis Europa,” and now we’re in Martin’s garage, listening to him being interviewed by an offscreen woman. His voice squarely occupies the central channel, with offscreen traffic sliding around the side channels. The same central zone is assigned to the wife and the kids. Would it be too much to say that the working people have taken control of the soundtrack? In any case, although the side channels are very active, the sound remains centered during a permutational cluster of family scenes (parents and children alone, father with daughter, mother with son, boy with father, daughter with mother).

This section ends with a final confrontation with the nosy reporters. The overall episode can be seen as a revisiting of Numero deux (1975), another uneasy family romance and one of Godard’s first forays into video.

The rapid-fire finale would require the sort of parsing that Histoire(s) du cinema has invited. Through footage swiped from many other filmmakers, Godard revisits the cruise ship’s ports of call, investing each with a symbolic role in the history of the West. Egypt and Greece get considerable emphasis, but so do Palestine and Israel. This history is, naturally, filtered through cinema: not just footage of the Spanish Civil War but clips from fiction films like The Four Days of Naples (1962). After glimpses of Eisenstein’s Odessa Steps massacre, we get shots of today’s kids standing on the steps declaring they have never heard of Battleship Potemkin.