Archive for the 'DVDs' Category

Pandora’s digital box: From films to files

“Up ahead was Pandora. You grew up hearing about it, but I never figured I’d be going there.”

DB here:

Actually it wasn’t originally a box but a jug. And it might not have been filled with all the world’s misfortunes; it might have housed all the virtues. In Greek mythology, the gods create her as the first woman, sort of the ancient Eve. We get our standard idea of her story not from the ancient world, however, but from Erasmus. In 1508 he wrote of her as the most favored maiden, granted beauty, intelligence, and eloquence. Hence one interpretation of her name: “all-gifted.” But to Prometheus she brought a box carrying, Erasmus said, “every kind of calamity.” Prometheus’ brother Epimetheus accepted the box, and either he or Pandora opened it, “so that all the evils flew out.” All that remained inside was Hope. (Don’t think there isn’t a lot of dispute about why hope was cooped up with all those evils.)

The idea of Pandora’s box spread throughout Western culture to denote any imprudent unleashing of a multitude of unhappy consequences. It’s long been associated with an image of an attractive but destructive woman, and we don’t lack examples in films from Pabst to Lewin. But there’s another interpretation of the maiden’s name: not “all-gifted” but “all-giver.” According to this line, Pandora is a kind of earth goddess. In one Greek text she is called “the earth, because she bestows all things necessary for life.”

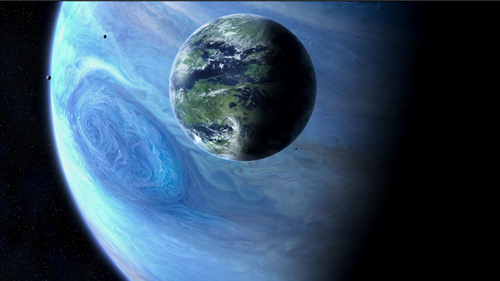

The less-known interpretation seems to dominate in Avatar. Pandora, a moon of the huge planet Polyphemus, is a lush ecosystem in which the humanoid Na’vi live in harmony with the vegetation and the lower animals they tame or hunt. Nourished by a massive tree (they are the ultimate tree-huggers), they have a balanced tribal-clan economy. Their spiritual harmony is encapsulated in the beautiful huntress Neytiri. As the mate for the first Sky-Person-turned-Na’vi, Avatar Jake, she’s also an interplanetary Eve. And by joining the Na’vi on Pandora, Jake does find hope.

The irony of a super-sophisticated technology carrying a modern man to a primal state goes back at least as far as Wells’ Time Machine. But the motif has a special punch in the context of the Great Digital Changeover. Digital projection promises to carry the essence of cinema to us: the movie freed from its material confines. Dirty, scratched, and faded film coiled onto warped reels, varying unpredictably from show to show (new dust, new splices) is now shucked off like a husk. Now images and sounds supposedly bloom in all their purity. The movie emerges butterfly-like, leaving the marks of dirty machines and human toil behind. As Jake returns to Eden, so does cinema.

Avatar or atavism?

Kristin suggested the title for this series of blog entries, and I liked its punning side. For one thing, Avatar was a turning point in digital projection. 3D, as we now know, was the Trojan Horse that gave exhibitors a rationale to convert to digital. Avatar, an overwhelming merger of digital filmmaking (halfway between cartoon and live-action) and 3D digital projection, fulfilled the promise of the mid-2000s hits that had hinted at the rewards of this format.

With its record $2.7 billion worldwide box office, Avatar convinced exhibitors that digital and 3D could be huge moneymakers. In 2009, about 16,000 theatres worldwide were digital; in 2010, after Avatar, the number jumped to 36,000. True, theatre chains also benefited from JP Morgan’s timely infusion of about half a billion dollars in financing in November 2009, a month before the film’s release. Still, this movie that criticized technology’s war on nature accelerated the appearance of a new technology.

Throughout this series, I’ve tried to bring historical analysis to bear on the nature of the change. I’ve also tried not to prejudge what I found, and I’ve presented things as neutrally as I could. But I find it hard to deny that the digital changeover has hurt many things I care about.

The more obvious side of my title’s pun was to suggest that digital projection released a lot of problems, which I’ve traced in earlier entries. From multiplexes to art houses, from festivals to archives, the new technical standards and business policies threaten film culture as we’ve known it. Hollywood distribution companies have gained more power, local exhibitors have lost some control, and the range of films that find theatrical screening is likely to shrink. Movies, whether made on film or digital platforms, have fewer chances of surviving for future viewers. In our transition from packaged-media technology to pay-for-service technology, parts of our film heritage that are already peripheral—current foreign-language films, experimental cinema, topical and personal documentaries, classic cinema that can’t be packaged as an Event—may move even further to the margins.

Moreover, as many as eight thousand of America’s forty thousand screens may close. Their owners will not be able to afford the conversion to digital. Creative destruction, some will call it, playing down the intangible assets that community cinemas offer. But there’s also the obsolescence issue. Equipment installed today and paid for tomorrow may well turn moribund the day after tomorrow. Only the permanently well-funded can keep up with the digital churn. Perhaps unit prices will fall, or satellite and internet transmission will streamline things, but those too will cost money. In any event, there’s no reason to think that the major distributors and the internet service providers will be feeling generous to small venues.

Did this Pandora’s box leave any reason to be optimistic? I haven’t any tidy conclusions to offer. Some criticisms of digital projection seem to me mistaken, just as some praise of it seems to me hype or wishful thinking. In surrendering argument to scattered observations, this final entry in our series is just a series of notes on my thinking right now.

What you mean, celluloid?

First, let’s go fussbudget. It’s not digital projection vs. celluloid projection. 35mm motion picture release prints haven’t had a celluloid base for about fifteen years. Release prints are on mylar, a polyester-based medium.

Mylar was originally used for audio tape and other plastic products. For release prints of movies, it’s thinner than acetate but it’s a lot tougher. If it gets jammed up in a projector, it’s more likely to break the equipment than be torn up. It’s also more heat-resistant, and so able to take the intensity of the Xenon lamps that became common in multiplexes. (Many changes in projection technology were driven by the rise of multiplexes, which demanded that one operator, or even unskilled staff, could handle several screens.)

Projectionists sometimes complain that mylar images aren’t as good as acetate ones. In the 1940s and 1950s, they complained about acetate too, saying that nitrate was sharper and easier to focus. In the 2000s they complained about digital intermediates too. Mostly, I tend to trust projectionists’ complaints.

But acetate-based film stock is still used in shooting films, so I suppose digital vs. celluloid captures the difference if you’re talking about production. Even then, though, there’s a more radical difference. A strip of film stock creates a tangible thing, which exists like other objects in our world. “Digital,” at first referring to another sort of thing (images and sounds on tape or disk), now refers to a non-thing, an abstract configuration of ones and zeroes existing in that intangible entity we call, for simple analogy, a file.

George Dyson: “A Pixar movie is just a very large number, sitting idle on a disc.”

Big and gregarious

Sometimes discussion of the digital revolution gets entangled in irrelevant worries.

First pseudo-worry: “Movies should be seen BIG.” True, scale matters a lot. But (a) many people sit too far back to enjoy the big picture; and (b) in many theatres, 35mm film is projected on a very small screen. Conversely, nothing prevents digital projection from being big, especially once 4K becomes common. Indeed, one thing that delayed the finalizing of a standard was the insistence that so-called 1.3K wasn’t good enough for big-screen theatrical presentation. (At least in Europe and North America: 1.3K took hold in China, India, and elsewhere, as well as on smaller or more specialized screens here.)

Second pseudo-worry: “Movies are a social experience.” For some (not me), the communal experience is valuable. But nothing prevents digital screenings from being rapturous spiritual transfigurations or frenzied bacchanals. More likely, they will be just the sort of communal experiences they are now, with the usual chatting, texting, horseplay, etc.

Of course, image quality and the historical sources and consequences of digital projection are something else again.

Irresolution

It’s a good thing the pros kept pushing. Had filmmakers and cinephiles welcomed the earliest digital systems, we might have something worse. Here’s George Lucas in 2005, talking less about photographic quality than the idea of the sanitary image.

The quality [of digital projection] is so much better. . . . You don’t get weave, you don’t get scratchy prints, you don’t get faded prints, you don’t get tears. . . The technology is definitely there and we projected it. I think it is very hard to tell a film that is projected digitally from a film that is projected on film.

And he’s referring to the 1280-line format in which Star Wars Episode I was projected in 1999.

Probably the widespread skepticism from directors and cinematographers helped push the standard to 2K. (So did the adoption of the Digital Intermediate.) Optimistic observers in the mid-2000s expected the major studios to make 4K the standard right away. Given the constraints of storage at that time, the 2K decision might be justified. But like the 24 frames-per-second frame rate of sound cinema, it was a concession to the just-good-enough camp.

At the same time, George seems to grant that progress will be needed in the area of resolution.

You’ve got to think of this [our current situation] as the movie business in 1901. Go back and look at the films made in 1901, and say, “Gee, they had a long way to go in terms of resolution. . . .”

Actually, in films preserved in good state from 1901, the resolution looks just fine—better than most of what we see at the multiplex today, on film or on digital.

The invisible revolution

Speaking of sound cinema: Is the changeover to talkies the best analogy for what we’re seeing now? Mostly yes, because of the sweeping nature of the transformation. No technological development since 1930 has demanded such a top-to-bottom overhaul of theatres. Assuming a modest $75,000 cost for upgrading a single auditorium, the digital conversion of US screens has cost $1.5 billion.

In an important respect, though, the analogy to sound doesn’t hold good. When people went to talkies, they knew that something new had been added. The same thing happened with color and widescreen. And surely many customers noticed multi-track sound systems. But what moviegoers notice that a theatre is digital rather than analog? Many probably assume that movies come on DVDs or, as one ordinary viewer put it to me, “film tapes.” Anyhow, why should they care?

There was a debate during the 2000s that audiences would pay more for a ticket to a digital screen. But that notion was abandoned. People aren’t that easy to sucker. So we’re back with 3D as the killer app, the justification for an upcharge. Whether 3D survives, dominates, or vanishes isn’t really the point. It’s served its purpose as the wedge into digital installation.

By the way, according to one industry leader, 2D ticket prices are likely to go up this year while 3D prices drop. Is this flattening of the price differential a strategy to get more people to support a fading format?

Mommy, when a pixel dies, does it go to heaven?

Digital was sold to the creative community in part by claiming that at last the filmmaker’s vision would be respected. Every screening would present the film in all its purity, just as the director, cinematographer et al. wanted it to be seen.

Last week I went to see Chronicle with my pal Jim Healy. The projector wasn’t perpendicular to the screen, so there was noticeable keystoning. The masking was set wrong, blocking off about a seventh of the picture area. And two little pink pixels were glowing in the middle of the northwest quadrant throughout the movie. I’m assuming that Chronicle’s director didn’t mandate these variants on his “vision.”

Jim went out to notify the staff, and two cadets came down to fiddle with the masking. The movie had already been playing in that house for several days. Maybe the masking hadn’t been changed for months? And of course the projector couldn’t be realigned on the fly. As for those pixels: There’s nothing to be done except buy a new piece of gear. Chapin Cutler of Boston Light & Sound tells me that replacing the projector’s light engine runs around $12,000. At that price, there may be a lot of dead pixels hanging around a theatre near you.

Video to the max

Not so long ago, the difference was pitched as film versus video. That was the era of movies like The Celebration and Chuck and Buck. Then came high-definition video, which was still video but looking somewhat better (though not like film). But somehow, as if by magic, very-high-definition video, with some ability to mimic photochemical imagery, became digital cinema, or simply digital.

We have to follow that usage if we want to pinpoint what we’re talking about at this point in history. But damn it, let’s remember: We are still talking about video.

The Film Look

Ever since the days of “film vs. video,” we’ve been talking about the “film look.” What is it?

I’m far from offering a good definition. There are many film looks. You have orthochromatic and panchromatic black-and-white, nitrate vs. acetate vs. mylar, two-color and three-color Technicolor, Eastman vs. Fuji, and so on. But let’s stick just with projection. Is there a general quality of film projection that differentiates it from digital displays?

Some argue that flicker and the slight weaving of film in the projector are characteristic of the medium. Others point to qualities specific to photochemistry. Film has a greater color range than digital: billions of color shades rather than millions. Resolution is also different, although there’s a lot of disagreement about how different. A 35mm color negative film is said to approximate about 7000 lines of resolution, but by the time a color print is made, the display yields about 5000 lines—still a bit ahead of 4K digital. But each format has some blind spots. There’s a story that the 70mm camera negative of The Sound of Music recorded a wayward hair sticking straight out on the top of Julie Andrew’s head. It wasn’t visible in release prints of the day, but a 4K scan of the negative revealed it.

Film fans point to the characteristic film shimmer, the sense that even static objects have a little bit of life to them. Roger Ebert writes:

Film carries more color and tone gradations than the eye can perceive. It has characteristics such as a nearly imperceptible jiggle that I suspect makes deep areas of my brain more active in interpreting it. Those characteristics somehow make the movie seem to be going on instead of simply existing.

Watch fluffy clouds or a distant forest in a digital display, and you’ll see them hang there, dead as a postcard vista. In a film, clouds and trees pulsate and shift a little. Partly the film is capturing very slight movements of them in air, or the movement of light and air around them. In addition, the film itself endows them with that “nearly imperceptible jiggle” that our visual system detects.

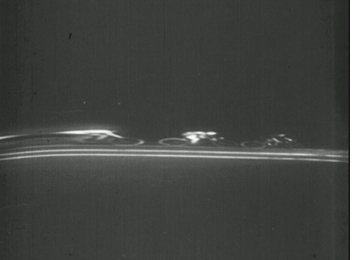

How? Brian McKernan points out that the fixed array of pixels in a digital camera or projector creates a stable grid of image sites. But the image sites on a film frame are the sub-microscopic crystals embedded in the emulsion and activated by exposure to light. Those crystals are scattered densely throughout the film strip at random, and their arrangement varies from frame to frame. So the finest patterns of light registration tremble ever so slightly in the course of time, creating a soft pictorial vibrato.

Another source of the film look was suggested to me by Jeff Roth, Senior Vice-President of Post-Production at Focus Features. Jeff notes that a video chip is a flat surface, with the pixels activated by light patterns across the grid. (We forget that in the earliest stages, “digital” image capture is “analog”—that is, photographic—before it gets quantized and then digitized.) But a film strip has volume. It seems very thin to us, but light waves find a lot to explore in there. Light penetrates different layers of the emulsion: blue on top, then a yellow filter, then green, then red. The light rays leave traces of their passage through the layers. Joao S. de Oliveira puts it more laconically:

There is a certain aura in film that cannot exist in a digital image. . . . From the capture of a latent image, the micro-imperfections created by light on a perfect crystalline structure—a very three-dimensional process—to its conversion into a visible and permanent artefact, the latitude and resolution of film are incomparable to any other process available today to register moving images.

For example, shadows and highlights are captured “deeply.” Bright areas move into shadow gracefully. Similarly, film is far more tolerant of overexposure than digital recording is; even blown-out areas of the negative can be recovered. (In still photography, darkroom technique allows you to “burn in” an overexposed area.) The blown-out elements are still there, but in digital they’re gone forever.

Film shown on a projector maintains the film look captured on the stock: You’re just shining a light through it. We’ve all heard stories, however, of those DVD transfers that buff the image to enamel brightness and then use a software program to add grain. One archivist tells me of an early digital transfer of Sunset Blvd. that looked like it had been shot for HDTV.

But today carefully done digital transfers can preserve some of the film look. When my local theatres were transitioning, I saw Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy first on film, then on digital, and then again on film. Although the digital looked a little harder, I was surprised how much graininess it preserved. So it seems to me that some qualities of the film look can be retained in digital transfers.

Marching orders

George Lucas, at the 2005 annual convention and trade show of the National Association of Theatre Owners: “I’m sort of the digital penny that shows up every year to say, ‘Why haven’t you got these digital theatres yet?'” (Variety 17 March 2005).

“His point to theater owners was that 3D, which can bring in new audiences and justify higher ticket prices, is only possible after they make the switch to digital projection” (Hollywood Reporter 10 February 2012).

Premonitions

In summer of 1999, Godfrey Cheshire published a two-part article, “The Death of Film/ The Decay of Cinema.” It’s proven remarkably far-sighted.

He predicted that within a decade your multiplex theatre would contain “a glorified version of a home video projection system.” He predicted that the rate of adoption would be held back by costs. He predicted that the changeover would mostly benefit the major distributors, and that exhibitors would have to raise ticket and concession prices to cover investments. He predicted what is now called “alternative content”—sports, concerts, highbrow drama, live events—and correctly identified it as television outside the home. He predicted the preshow attractions that advertise not only products but TV shows and pop music. He predicted what is being seriously discussed in industry circles now: letting viewers snap open their “second screen” and call, text, check email, and surf the net during the show. And he predicted that distractions and bad manners in movie theatres would drive away viewers who want to pay attention.

People who want to watch serious movies that require concentration will do so at home, or perhaps in small, specialty theatres. People who want to hoot, holler, flip the bird and otherwise have a fun communal experience . . . will head down to the local enormoplex.

Godfrey goes on to make provocative points about the effects of digital technology on how movies are made as well. His essay should be prime reading for everyone involved in film culture—e.g., you.

WYSIWYG

I’ve mentioned the postcard effect that makes static objects just hang there. In less-than-2K digital displays, I see other artifacts, most of which I don’t know the terms for. Film has artifacts too, notably graininess, but I find the digital ones more off-putting. There’s a waterfall effect, when ripples rush down uniform surfaces. Sometimes I see diagonal striping from one corner to its opposite, an effect common on home and bar monitors. (I’m told it comes from interference from phones and the like.) On cheap DVDs, or commercial ones played on region-free machines, you can detect a weird pop-out effect, where the surfaces of different planes, usually marked by dark edge contours, detach themselves. The surfaces float up, wobbling out of alignment with their surroundings.

I am not hallucinating these things. When I point them out, others see them, and then, like me, they can’t ignore them. So I’ve stopped pointing them out, especially when a friend wants to show me his (always his) fancy home theatre. Why spoil their pleasure?

Same difference

Various positions on the split between film and digital (for want of a better term): I’ve held nearly all of them at various points, and sometimes simultaneously. I’ll confine myself, as usual, just to film-based projection and digital projection, and assuming minimal competence of staff in each domain. (Just because something’s shown in 35mm, that doesn’t mean it’s shown well.)

1. They’re not the same, just two different media. They’re like oil painting and etching. Both can coexist as vehicles for artists’ work.

2. They’re not the same, and digital is significantly worse than film. This was common in the pre-DCI era.

3. They’re not the same, and digital is significantly better than film. Expressed most vehemently by Robert Rodriguez and with some insistence by Michael Mann.

4. They’re not the same, and digital is mostly worse, but it’s good enough for certain purposes. Espoused by low-budget filmmakers the world over. Also embraced by exhibitors in developing countries, where even 1.3K is considered an improvement over what people have been getting.

5. They’re the same. This is the view held by most audiences. But just because viewers can’t detect differences doesn’t mean that the two platforms are equally good. Digital boosters maintain that we now have very savvy moviegoers who appreciate quality in image and sound. In my experience, people don’t notice when the picture is out of focus, when the lamp is too dim, when the surround channels aren’t turned on, when speakers are broken, and when spill light from EXIT signs washes out edges of the picture. (See Chronicle anecdote above.) As long as they can hear the dialogue and can make out the image, I believe, most viewers are happy.

‘Plex operators are notoriously indifferent to such niceties. In most houses, good enough is good enough. Teenage labor can maintain only so much.

Film/video

“The picture was nice and crisp.” “So much better than film.” “We showed a Blu-ray and it looked fine.”

I don’t trust people’s responses to such things unless the judgment is comparative. Show film and the digital program side by side and then judge. Or even show rival manufacturers’ DCI-compliant projectors side by side. I think you will see differences.

As they develop, new reproductive media improve in some dimensions but degrade on others. As the engineers tell us, there’s always a trade-off.

CD is more convenient than vinyl, but its clean, dry sound isn’t as “warm.” Mp3, even more convenient and portable, packs a sonic punch but is inferior in dynamics and detail to CDs. Similarly, back in the 1990s, laserdiscs had to be handled more carefully than tape cassettes, and in playback they required interruptions as sides were flipped. But aficionados accepted these drawbacks because we believed that our optical discs looked and sounded much better than VHS. One well-known professor urged that classroom screenings could now dispense with film.

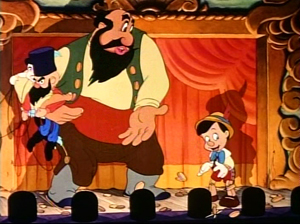

Now those laserdisc images would be laughed out of the room. Have a look at an image from the 1995 restoration of Disney’s Pinocchio. It’s taken from a transfer of the laserdisc to DVD-R. (You can’t grab a frame directly from a laserdisc.) In this and the others, I haven’t adjusted the raw image.

Actually, on a decent monitor, it looks better than this. Since you can’t grab a frame directly from a laserdisc, LD couldn’t stand up to home theatre projection today. The 2009 DVD and Blu-ray (below) are sharper.

Now compare the DVD with a dye-transfer Technicolor image from a 1950s 35mm print. There have been some gains and some losses in color range, shadow, and detail. For example, Stromboli’s trousers and the footlight area go very black, presumably because of the silver “key image” used for greater definition in the dye-transfer process. IB Tech restorations routinely bring out “hidden” color in such areas.

Which is best? You can take your pick, but you’re better able to choose when you’re not seeing one image in isolation.

Live/ Memorex

Of course side-by-side comparisons can fail when most viewers don’t notice even gross differences. In a course, I once showed a 16mm print of Night of the Living Dead, and a faculty friend came to the screening. (Yes, history profs can be horror fans.) In my followup lecture, I showed clips on VHS, dubbed from a VHS master. My friend came to the class for my talk. Afterward he swore that he couldn’t tell any difference between the film and the second-generation VHS tape.

This raises the fascinating question of changing perceptual frames of reference. My friend knew the film very well, and he’d watched it many times on VHS. Did he somehow see the 16 screening as just a bigger tape replay? Did none of its superiority register? Maybe not.

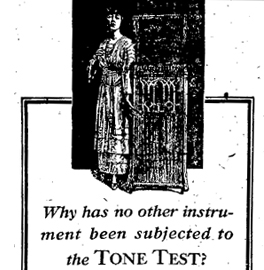

From 1915 to 1925, Thomas Edison demonstrated his Diamond Disc Phonograph by inviting audiences to compare live performances with recordings. His publicists came up with the celebrated Tone Tests. A singer on stage would stand by while the disc began to play. Abruptly the disc would be turned down and the singer would continue without missing a note. Then the singer would stop and the disc, now turned up, would pick up the thread of melody. Greg Milner writes of the first demonstration:

From 1915 to 1925, Thomas Edison demonstrated his Diamond Disc Phonograph by inviting audiences to compare live performances with recordings. His publicists came up with the celebrated Tone Tests. A singer on stage would stand by while the disc began to play. Abruptly the disc would be turned down and the singer would continue without missing a note. Then the singer would stop and the disc, now turned up, would pick up the thread of melody. Greg Milner writes of the first demonstration:

The record continued playing, with [the contralto Christine] Miller onstage dipping in and out of it like a DJ. The audience cheered every time she stopped moving her lips and let the record sing for her.

At one point the lights went out, but the music continued. The audience could not tell when Miller stopped and the playback started.

The Tone Tests toured the world. According the publicity machine run by the Wizard of Menlo Park, millions of people witnessed them and no one could unerringly distinguish the performers from their recording.

Edison’s sound recording was acoustic, not electrical, and so it sounds hopelessly unrealistic to us today. (You can sample some tunes here.) And there’s some evidence, as Milner points out, that singers learned to imitate the squeezed quality of the recordings. But if the audiences were fairly regularly fooled, it suggests that our sense of what sounds, or looks, right, is both untrustworthy and changeable over history.

To some extent, what’s registered in such instances aren’t perceptions but preferences. Wholly inferior recording mechanisms can be favored because of taste. How else to explain the fact that young people prefer mp3 recordings to CDs, let alone vinyl records? It’s not just the convenience; the researcher, Jonathan Berger of Stanford University, hypothesizes that they like the “sizzle” of mp3.

To some extent, we should expect that people who’ve watched DVDs from babyhood onward take the scrubbed, hard-edge imagery of video as the way that movies are supposed to look. Or perhaps still younger people prefer the rawer images they see on Web videos. Do they then see an Imax 70mm screening as just blown-up YouTube?

The epiphanic frame

Godard’s Éloge de l’amour: DVD framing vs. original 35mm framing.

Digital projection is already making distributors reluctant to rent films from their libraries, and film archives are likely to restrict circulation of their prints. When 35mm prints are unavailable, it will be difficult for us to perform certain kinds of film analysis. In order to discover things about staging, lighting, color, and cutting in films that originated on film, scholars have in the past worked directly with prints.

For example, I count frames to determine editing rhythms, and working from a digital copy isn’t reliable for such matters. True, fewer than a dozen people in the world probably care about counting frames, so this seems like a trivial problem. But analysts also need to freeze a scene on an exact frame. For live-action film, that’s a record of an actual instant during shooting, a slice of time that really existed and serves to encapsulate something about a character, the situation, or the spatial dynamics of the scene. (Many examples here.) This is why my books, including the recent edition of Planet Hong Kong, rely almost entirely on frame grabs from 35mm prints.

Paolo Cherchi Usai suggests that for every shot there is an “epiphanic frame,” an instant that encapsulates the expressive force of that shot. Working with a film print, you can find it. On video, not necessarily.

Just as important, for films originating in 35mm, we can’t assume that a video copy will respect the color values or aspect ratio of the original. Often the only version available for study will be a DVD with adjusted color (see Pinocchio above) and in a different ratio. I’ve written enough about variations in aspect ratios in Godard and Lang (here and here) to suggest that we need to be able to go back to 35mm for study purposes, at least for photographically-generated films. For digitally-originated films, researchers ought to be able to go back to the DCP as released, but that will be nearly impossible.

The analog cocoon

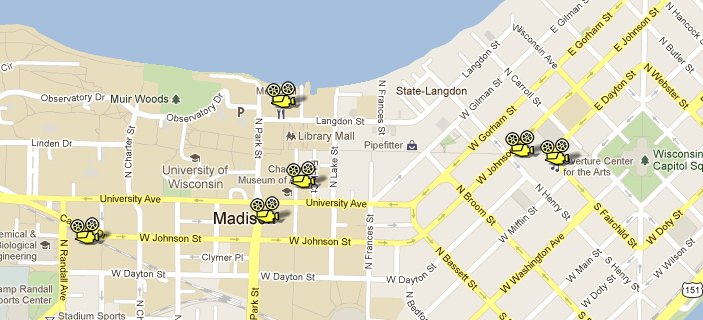

I began this series after realizing that in Madison I was living in a hothouse. As of this fall, apart from festival projections on DigiBeta or HDCam, I hadn’t seen more than a dozen digital commercial screenings in my life, and I think nearly all were 3D. Between film festivals, our Cinematheque, and screenings in our local movie houses, I was watching 35mm throughout 2011, the year of the big shift.

There are six noncommercial 35mm film venues within walking distance of my office at the corner of University Avenue and Park Street. And two of those venues still use carbon-arc lamps! Go here for a fuller identification of these houses. Moreover, in my office sit two Steenbeck viewing machines, poised to be threaded up with 16mm or 35mm film. (“Ingestion” is not an option.)

But now I’ve woken up. We all conduct our educations in public, I suppose, but preparing this series has taught me a lot. I still don’t know as much as I’d like to, but at least, I now appreciate the riches around me.

I’m very lucky. It’s not over, either. The good news is that the future can’t really be predicted. Like everybody else, I need to adjust to what our digital Pandora has turned loose. But we can still hold on to hope.

This is the final entry in a series on digital film distribution and exhibition.

On the Pandora perplex, see Dora and Erwin Panofsky, Pandora’s Box: The Changing Aspects of a Mythical Symbol (Princeton University Press, 1956). The Wikipedia article on the lady is also admirably detailed.

Godfrey Cheshire’s prophetic essay is apparently lost in the digital labyrinths of the New York Press. Godfrey tells me that he’s exploring ways to post it, so do continue to search for it. Another must-read assessment is on the TCM site. Pablo Kjolseth, Director of the International Film Series at the University of Colorado—Boulder, writes on “The End.” See also Matt Zoller Seitz’s sensible take on the announcement that Panavision has ceased manufacturing cameras. Some wide-ranging reflections are offered in Gerda Cammaer’s “Film: Another Death, Another Life.”

Brian McKernan’s Digital Cinema: The Revolution in Cinematography, Postproduction, and Distribution (MGraw-Hill, 2005) is the source of two of my quotations from George Lucas (pp. 31, 33) and some ideas about the film look (p. 67). My quotation from Greg Milner on the Tone Test comes from his Perfecting Sound Forever: An Aural History of Recorded Music (Faber, 2009), 5.

NPR recently broadcast a discussion of the differences, both acoustic and perceptual, among consumer audio formats. The show includes A/B comparisons. Thanks to Jeff Smith for the tip.

Thanks to Chapin Cutler, Jeff Roth, and Andrea Comiskey, who prepared the projector map of downtown Madison and the east end of the campus.

6 February 2012: This series has aroused some valuable commentary around the Net, just as more journalists are picking up on the broad story of how the conversion is working. Leah Churner has published a useful piece in the Village Voice on digital projection, and Lincoln Spector has posted three essays at his blogsite, the last entry offering some suggestions about how to preserve both film-based and digital-originated material.

“You get soft, Pandora will shit you out dead, with zero warning.”

Silents nights: DVD stocking-stuffers for those long winter evenings

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts

Kristin here:

The year 2011 has been a good year for silent cinema on DVD. In time for the holiday shopping season, here’s an overview of some of the highlights.

One-stop shopping for the latest restorations

In the past we have recommended films released on DVD through the Munich Film Museum’s Edition Filmmuseum. We haven’t really emphasized enough, however, what a major resource this site is for film enthusiasts interested in restorations of older films and new editions of hard-to-see modern films (like the work of James Benning). Edition Filmmuseum sells not only its own impressive series of releases but also DVD editions of restorations by other major national European archives. Its website is available in German and English versions, and it is as easy to sign up and order DVDs there as it is through Amazon. The DVDs on offer can be browsed via a number of different categories, such as “Silent films,” “German movies,” and “Danish classics.” Releases from Lobster Films and Flicker Alley are also available through Edition Filmmuseum. Have a look at its forthcoming releases here. North American educational institutions seeking public performance rights for many of these and other titles should contact Gartenberg Media Entertainment.

Scandinavia comes on strong

Danish and Swedish films show up fairly regularly on DVD these days, but Norwegian films are rarities. This year, though, there are two of them.

The Danish Film Institute continues to release the films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. This time it’s a pairing of Elsker Hverandre (Love One Another, 1922) and Glomdalsbruden (The Bride of Glomdal, 1926), also available in Blu-ray. (See below.) I have to admit that these are not among my favorite Dreyer films, and I don’t think many would put them alongside his best works. Still, Dreyer is one of the great masters of world cinema, and anyone seriously interested in film history will want to see these. Back when David was working on his book on Dreyer, we went to Copenhagen and saw these at the Film Institute. They were incredibly rare, and it was a privilege to see them. Now, they’re available to all. Check out the Institute’s entire list of restored Danish classics on DVD here.

[Dec. 16: Archivist Jan-Christopher Horak has recently blogged about Elsker Hverandre.]

The Bride of Glomdal is the first of our two Norwegian features. Dreyer worked outside Denmark a number of times. In the summer of 1925 he shot this film in Norway. His next film was to be La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc.

The second is Laila, a 1929 Norwegian feature, also with a Dreyer connection. Its director, George Schéevoigt, had been Dreyer’s  cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

cinematographer for some of his early films: Leaves from Satan’s Book, The Parson’s Widow, Once Upon a Time, and Master of the House. Laila bears no sign of Dreyer’s influence, but its images, shot in the snowy mountains and valleys of the arctic regions of Norway, are gorgeous.

Like many features made in countries with no real established film industry (Laila’s footage had to be processed and edited in Copenhagen), Laila exploits both national literature and landscapes to distinguish itself from the Hollywood films that dominated European theaters. It was based on an 1881 novel by J. A Friis, Fra Minmarken, Skildringer. Friis strove to promote the rights of the indigenous Sami people (sometimes known as Lapps). The story follows the heroine, Laila, from infancy to adulthood. The first half of the film succeeds in giving a distinctly non-classical feel to the story. Laila is lost in the snowy wastes when wolves attack her family as they travel on sleds. She is found and nurtured by a childless Sami couple who come to love her but return her to her parents when they learn her background. The scene of the return is handled in a subtle and moving fashion. As the grieving parents console each other on Christmas Eve, Aslag, the baby’s foster father, enters at the left, with the tree blocking the door. He crosses to appear at the center and puts the child beside the presents under the tree:

A cut-in to Aslag shows him struggling with his emotions before turning to the parents and declaring, “Tonight all should be happy.” The mystified parents stare at him uncomprehendingly before he explains that he had found their daughter:

Once Laila grows up, the film turns into the more typical romantic triangle. Still, its epic landscapes and focus on a little-known ethnic group make it quite appealing, and the print itself is gorgeous. Flicker Alley has provided a rare opportunity to step outside the more familiar filmmaking countries and explore a bit. Our friend, the fine Danish film historian Casper Tyberg, has provided a helpful text in the accompanying booklet.

Casper also provides a commentary for The Criterion Collection’s release of the restored version of Victor Sjöström’s The Phantom Chariot. (It’s number 579 for you Criterion completists–but you already know about this disc anyway.) I won’t say much about it, since it will inevitably show up in our year-end list of the ten best films of 1921. Here I’ll just note that it’s also a beautiful print, with impeccable tinting and toning that don’t darken the images to the point where the composition is obscured–something I’ve seen too often in recent DVD releases of silent films. The frame above shows the opening scene, with its masterful control of lighting. I was disappointed that the supplements stress Sjöström’s influence on Ingmar Bergman. It may sound heretical, but Sjöström seems to me the better director, and I wish there had been more on his career.

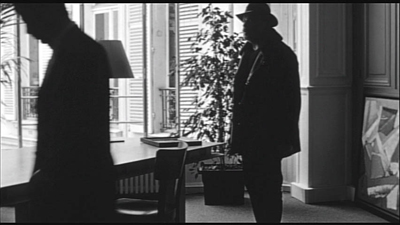

One of the most obscure of German Expressionist films

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morning to Midnight”) is an early Expressionist film. It came out the same year as Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. It’s based on a play by one of the major Expressionist dramatists, Georg Kaiser, and directed by one of the major Expressionist stage directors, Karlheinz Martin. The problem is, it never got released in Germany.

Most of the classic Expressionist films are, like Caligari, horror films that motivate their stylization through genre. Von Morgens bis Mitternachts adheres to the subject matter of Expressionist theater, which was vehemently critical of modern society. It centers around a downtrodden bank clerk who suddenly rebels against his apparently happy family life and good job, stealing a huge sum from the bank and trying to run off with a glamorous rich woman who visits the bank. Rejected by her, he wanders away to spend the money in frivolous pursuits.

It’s no wonder that German distribution companies shied away from releasing the film. Its only known theatrical screenings were in Japan, where one nitrate positive print survived. I saw an archival copy years ago. It was an impressive film, more extreme in its stylization than Caligari or even Robert Wiene’s second Expressionist film, Genuine. (All three films were released in 1920.) Unfortunately it had no intertitles, which made it seem all the more radical.

In 1987 censorship records were discovered that allowed the Munich Filmmuseum to reconstruct the intertitles and create the restored version that now has been released on DVD. It’s a significant film, not only as an artistic achievement but as a record of stage  Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Expressionism of the 1910s. Few plays of the era were filmed, most importantly this one and Jeopold Jessner’s 1923 film Erdgeist, adapted from the play by Frank Wedekind and starring Asta Nielsen and Albert Bassermann. (The play was adapted again by G. W. Pabst as Pandora’s Box, starring Louise Brooks, in 1929; wonderful though that version is, it retains little of the radical Expressionism of the original.)

Von Morgens bis Mitternachts has some of the most avant-garde set designs of the era. Jagged white sets are smeared across back voids, as in the scene at the top where the protagonist flees down an endlessly winding road after being rebuffed by the woman for whom he impetuously stole money. It records another performance by one of the leading Expressionist actors of the era, Ernst Deutsch, whom I mentioned in my entry on Der Golem. Apart from its jagged sets, the film features a remarkable scene at a bicycle race, with the contestants being filmed in a distorting mirror. It was a technique that the French Impressionists would soon popularize, but Martin may have used it first (see left).

Despite the film’s lack of impact at the time it was made, it belongs squarely within the German Expressionist movement. This release at last allows it to take its place. (The forthcoming issue of the restored Expressionist science-fiction film Algol, also from 1920, will give an even broader picture of the movement.)

Eureka! Ford is found

The British company Eureka! continues to bring out classic films of all sorts. Its “Masters of Cinema” series has released John Ford’s 1924 western,  The Iron Horse. By this point in his career, Ford has made many western features, only a few of which survive. They were lively low-budget films, but by the early 1920s the western became a prestige genre with the success of James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon in 1923. The Iron Horse was Ford’s move into the high-budget western, and what it lacks in high-spirited energy it makes up for in impressive landscapes and careful dramatic staging. The Indian attack on the train, revealed by shadows (right) is one of the film’s high points.

The Iron Horse. By this point in his career, Ford has made many western features, only a few of which survive. They were lively low-budget films, but by the early 1920s the western became a prestige genre with the success of James Cruze’s The Covered Wagon in 1923. The Iron Horse was Ford’s move into the high-budget western, and what it lacks in high-spirited energy it makes up for in impressive landscapes and careful dramatic staging. The Indian attack on the train, revealed by shadows (right) is one of the film’s high points.

This Eureka! release is the same version and has the same extras as the DVD in the American series “Ford at Fox.” The two-disc set includes both the 150-minute version released in the U.S. and a 133-minute version, with alternate takes, distributed abroad. Anyone in European Region 2 area who doesn’t want to buy the immense “Ford at Fox” set of 21 discs might want instead to pick up The Iron Horse, one of its highlights, separately. It has plenty of extras as well.

I’ll sneak in an early sound film by recommending another Eureka! release of just about a year ago, Max Ophuls’ La signora di tutti (Everybody’s Lady). Made in italy in 1934, it was Ophuls’ first film after fleeing the Nazi regime. It’s a flashback tale, with the heroine recalling her life after a failed suicide attempt. It’s a new transfer and comes with a video essay by Tag Gallagher and a booklet.

Do yourself, your family, and your friends a favor

The 1994 edition of the “Giornate del Cinema Muto” in Pordenone, Italy, was as memorable as usual. There was the magical presentation of all the surviving Indian films (apart from a few short scraps), accompanied by a delightful and inventive chamber group of three Indian musicians. There were the silent westerns of William Wyler and the sophisticated 1920s features of Monte Bell. The main thread, though, was “Forgotten Laughter,” a celebration of known, little known, and unknown comedians. Their films were mainly shorts, and they provided us with a great deal of laughter.

Then came Wednesday, October 12, when we all witnessed history. A program entitled “Max Davidson” unspooled five two-reelers starring a short, middle-aged guy doing a beleaguered-Jewish-father shtick as well as such a thing has ever been done. We enjoyed four films before the program culminated with the immortal Pass the Gravy. I don’t think I’ve ever heard an audience laugh so loudly and continuously. Don’t assume this is anti-Jewish humor. This is pure Jewish humor, injected for just a few years into mainstream American slapstick filmmaking.

For some reason that year there was a poll taken to determine a film which would be encored at the end of the final evening. Pass the Gravy inevitably won, and we laughed just as hard the second time through. Mere words cannot convey why this film is so funny. It involves Max’s  daughter being engaged to a young man who lives next door with his father, proud owner of a prize rooster which ends up the main dish in a meal shared by both families. The running gag involves the young people trying to convey to Max what has happened without the young man’s father realizing what has happened. But no, you have to see it for yourself, preferably with friends and family about you. Like so many comedies, this one works best with an audience.

daughter being engaged to a young man who lives next door with his father, proud owner of a prize rooster which ends up the main dish in a meal shared by both families. The running gag involves the young people trying to convey to Max what has happened without the young man’s father realizing what has happened. But no, you have to see it for yourself, preferably with friends and family about you. Like so many comedies, this one works best with an audience.

It has taken 18 years for the surviving Max Davidson shorts, most of them supervised by Leo McCarey, to appear on video, a two-disc set, “Max Davidson Comedies.” Fortunately the job has been done well. The Munich Filmmuseum has assembled 13 shorts, 12 silent and one sound. Not all are as funny as Pass the Gravy, and Max plays only a supporting role in the earliest one. (The less said of the sound short, the better.) A booklet, in German and English, includes historical background and complete credits, including descriptions of the lost films. Davidson, by the way, had a long career playing bit parts, often uncredited. Often he played tailors, as in The Idle Class and The Extra Girl; during the sound era he appeared in The Plainsman and The Great Dictator, among many others. But for a short stretch at the Hal Roach studios he was the star.

At this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, “Max Davidson Comedies” shared the DVD prize for “Best Rediscovery of a Forgotten Film” with a parallel set put out by the Filmmuseum, “Female Comedy Teams.” The latter included more films shown in Pordenone in 1994.

Of course, the Davidson films were not forgotten by those of us lucky enough to have been in the Cinema Verdi in 1994. Two of them, including Pass the Gravy, were shown on Turner Classic Movies at 6 am a few years later, and we long treasured our VHS tape of that. But now everyone can share in this rediscovery.

A modestly pioneering early American film company

The Kalem company was one of those firms that cropped up during the early years of the American film industry, made shorts and short features for less than ten years, and disappeared without growing into one of the important Hollywood studios. Today it is perhaps best remembered for its 1913 biblical feature, From the Manger to the Cross, which was shot in Egypt and “the Holy Lands” at a time when filming abroad was unusual for  American film companies.

American film companies.

Kalem had pioneered the tactic of filming abroad earlier, however. Its series of films shot in Ireland, beginning with The Lad from Old Ireland (1910), are claimed to be the first American films shot outside North America. Eight of these survive, though often with missing sections. The Irish Film Institute has released a two-disc set including all of them, along with a feature-length documentary, Blazing the Trail: The O’Kalems in Ireland, directed by Peter Flynn.

The films were shot in the region of the Lakes of Killarney, taking advantage of famous locales like the Gap of Dunloe and Torc Waterfall (seen in Rory O’More, right). Intertitles include passages emphasizing that the scenes were shot in the very places where their historical and literary sources were set.

Unfortunately even the surviving films are not in good condition. Some are lacking their endings, and all are worn. The transfer has unfortunately cropped the edges, even though the accompanying documentary stresses that director Sidney Olcott’s main strength was his eye for compositions. Still, this set of films provides a rare example of fairly standard American films of the transitional period between the primitive and classical eras. Most classes in cinema history represent this transitional period mainly through the Biograph shorts of D. W. Griffith. This DVD provides a chance to show the more mainstream filmmaking of the early 1910s.

The accompanying documentary, Blazing the Trail, takes its title from the memoirs of Gene Gauntier, Kalem’s main scenario-writer and leading lady in its early period, including most of the Irish-based films. The film is perhaps a bit over-long for the topic, but it provides a rare in-depth look at a small company of the early era. The DVD set is available only from the Irish Film Institute’s website.

Beyond praise 4: Even more DVD supplements that really tell you something

David Fincher, foreground left, lays out a scene for The Social Network

Kristin here:

Every year or so I write an entry on useful DVD supplements. These aren’t necessarily very recent ones, but items I’ve come across that actually reveal something interesting about the filmmaking process—as opposed to the litanies of mutual praise that making-ofs too often spend time on. For the three earlier entries, see here, here, and here.

These posts are aimed partly at fans, of course, but also offer suggestions to teachers who use Film Art concerning useful teaching tools to be found among the supplements.

Often the most elaborate DVD extras are those for big fantasy and science-fiction films. There’s certainly no shortage of clips and examples if you’re teaching special effects! The trouble is to find good supplements about the basic techniques of pre-production and filming. I’ve included some effects-heavy films in past entries, but I’m happy this time to have two dramas whose supplements don’t even mention special effects.

The Social Network (“Two-disc Collector’s Edition,” Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

As with many DVDs, the long, chronologically organized account of how the film was made is the least interesting of the supplements. But hang on, because the short, specialized ones that follow are terrific.

The feature-length documentary, “How Did They Ever Make a Movie of Facebook?” starts with pre-production, a section which is mildly interesting but basically uninformative. It then continues with four parts: “Boston,” “Andover,” and “Los Angeles,” and “The Lot.” The “Los Angeles” scene includes an excellent scene showing the camera on a dolly, rapidly tracking back in front of Eduardo (Andrew Garfield) as he hurries to confront Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg). This 92-minute making-of skips post-production and ends with a montage of self- and mutual congratulations.

I should add that there are moments during this film where the rehearsals and the exchanges between the actors and Fincher on set do reveal something about how performances are crafted. Someone who wanted to teach a unit on acting might find it helpful to pull out clips of these interesting moments and have students read David’s entry on the performances in the film.

Otherwise, save your 92 minutes and go straight to the “Additional Special Features.”

First is “Jeff Cronenweth and David Fincher on the Visuals.” At only 7 1/2 minutes, this is packed with good stuff. Cronenweth discusses why he and Fincher decided to go with Red HD cameras (below left) rather than the Vipers used for Zodiac and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. It well illustrates of what we talk about in Chapter 1 of the ninth edition of Film Art: technical decisions being made for aesthetic purposes. According to Cronenweth, digital cameras innately have greater depth of field than 35mm ones do, and the featurette explains how to manipulate depth of field in digital filmmaking in order to guide the attention of the viewer. Finally, there’s an enlightening example of how three cameras fastened together can take separate images that can be tiled into a long, panoramic space. The filmmakers can than create camera movements within that panorama, add lights, and otherwise manipulate the image in ways that will be imperceptible to the viewer.

“Angus Wall, Kirk Baxter, Ren Klyce on Post” is just as good if not better. It’s mostly about editing. About a minute in, Baxter, the editor, talks about how Fincher wanted him to conform to traditional rules of continuity editing, never crossing the axis of action. As he puts it, “We’re always doing basic film law, but it can just be done extremely rapidly.” In other words, the average shot length may be lower than in older Hollywood films, but the methods of handling space for clarity are still observed. One passage of this supplement shows the difficulty of keeping eyelines straight when shooting a group at a table (a topic we deal in Film Art using a simpler example from Bringing up Baby). Klyce, the sound designer, discusses being able to edit individual words from different takes to create exactly the dialogue the director wanted. He also points out that Fincher insisted that background noises be as loud as the dialogue being spoken by the principal characters present. That’s a pretty unconventional approach, as we mention in our sound chapter.

At several points in this supplement, the juxtaposition of two or more images in a black background helps illustrate the point, as in the frame at the top of this entry.

The innovative music in The Social Network has rightly drawn a great deal of attention, including an Oscar and other awards. It’s covered in “Trent Razor, Atticus Ross, David Fincher on the Score.” Again some of the concepts we lay out in Film Art show up here. The composers and director talk about how music affects the spectator’s expectations. They point out that variants of a key musical theme are used to connect three scenes (i.e., a musical motif links parts together to create a formal whole). That musical motif involves a slow, wistful piano tune played over a faintly ominous undercurrent of electronic tones. To indicate the progression across the film, the piano was recorded with the microphone at a different distance from the instrument each time, affecting its timbre.

“Swarmatron” is really an extension of the music supplement, this time focusing on a particular and eccentric musical instrument.

Finally, there’s a segment on the big night-club scene, “Ruby Skye VIP Room: Multi-angle Scene Breakdown,” which is about four minutes long. Multi-angle layouts of scenes juxtaposing the different camera angles within the frame have become fairly common on DVDs. Here, though, Kirk Baxter and Ren Klyce return to offer more insights into the post-production and how these disparate images and sounds were combined. This supplement is interactive, and one can choose which versions of the shots and sound to use. I didn’t try all possible combinations. Choosing “1) Composite view” and “2) Interviews” worked well, I thought.

Another Fincher film, Zodiac, has been discussed in our “Beyond praise” series. Evidently Fincher understands what makes for a useful supplement–at least when it comes to the ones that deal with specific aspect of filmmaking.

District 9 (“2-disc Edition,” Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

To begin with, don’t bother with the three short “The Alien Agenda: A Filmmaker’s Log” films on the same disc as the feature. They’re perfunctory and uninformative, probably something produced for cable channels to run as publicity.

The good stuff is on the supplements disc. Which has previews on it. I expect previews before the film, but in front of the supplements?! Maybe I just haven’t noticed this before, but this is the first time I was actively annoyed by it. At least one can skip through them by pressing the “next” button three times.

The individual documentaries are pretty good of their type. “Metamorphosis: The Transformation of Wikus” focuses on the make-up designed for the main character, Wikus Van Der Merwe, in the portion of the film after he is infected by something that turns him into one of the aliens he has been trying to control. This is as straightforward and dramatic a demonstration of make-up as you’re likely to see.

A lot of the film’s acting involved improvising on camera, and “Innovation: The Acting and Improvisation of District 9” is an unusually interesting little supplement on acting. Again, teachers who want to teach an extensive unit on acting might want to use this. It creates a considerable contrast with the main Social Network making-of, where Aaron Sorkin states quite emphatically that there was no improvisation at all on his film.

“Conception and Design: Creating the World of District 9” goes into such topics as the design of the aliens’ weapons (below, top). It’s fairly typical of these sorts of supplements, but there is a discussion of how the space-ship design was consciously imitating the style of sci-fi films of the 1970s and 1980s. That is, Alien (1979) introduced the notion that space craft could be corroded and dingy(below, bottom)–as opposed to the squeaky-clean interiors of the ships in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Thus the idea of styles and genres having their own histories, which we bring up in Film Art, is exemplified.

“Alien Generation : The Visual Effects of District 9” has some interesting footage exemplifying the challenges of trying to shoot improvised acting with a hand-held camera while having a motion-capture camera filming the same action simultaneously. With both cameras, complete with separate small crews, move in unpredictable ways, they tend to get in each other’s way. There’s also a nice moment at the end when a technician shows off a rotating still camera on a tripod. It’s used to record the light coming from all directions, so that the digital effects can add in light that’s consistent with that on set.

The New World (New Line Home Entertainment)

Note: Both the theatrical version DVD and the “Extended Cut” one (which restores 35 minutes cut by Malick for the theatrical release and is also available in on Blu-ray) have the same supplements.

With all the anticipation building up around Terence Malick’s upcoming The Tree of Life, I wondered what a making-of for a Malick film would look like. Would the elusive Mr. Malick take part, or would he allow little or no behind-the-scenes footage?

Turns out he did not take part, but the makers of “Making The New World,” a one-hour supplement, took an imaginative approach by attaching themselves to the second unit. That’s the unit that typically films the action and landscape shots, scenes where the main actors are not delivering dialogue. In this case the unit had plenty of work to do. We see the filming of a fire at the fort, footage of the three ships sailing up the river in the marvelous opening scene, and a long battle between the Native Americans and colonists.

The documentary camera operators were allowed to tag along right behind or even in the midst of the cinematographer’s team, who clearly cooperated extensively. A lot of what we witness is actual filming, often glimpsed over the shoulders of assistants, still photographers, the second-unit assistant director, the fight choreographer, and others. (See below.)

I doubt very much of the coverage was planned in advance. The camera dodges around people who intrude unexpectedly into the foreground, and in a few cases the microphone is too far from what’s going on, and the filmmakers insert subtitles to let us know what was said. The interview footage clearly included anyone the documentarists could corral between takes, including various bit players, make-up people, the assistant director, just whoever was available. It comes as a shock when about half-way through Colin Farrell appears briefly to make a few remarks. In this brief interview with one of the Indian actors, people pass close by in the background, making noise that competes with what he says:

The result is a greater immersion in the filmmaking process than I’ve seen in any making-of. There’s no real attempt to explain any aspect of filmmaking–no voiceover narration, no superimposed titles apart from the ones identifying the people speaking.

Overall, this caught-on-the-fly footage gives the impression that any aspect of filmmaking can be interesting. So often the directors of supplements foreground the stars and try to inject drama into what is already a fascinating subject. Here there might be a plastic tarp being put over a camera during the rain or a camera assistant instructing extras on a ship to make sure that their water bottles aren’t in frame, and the supplement makers include it.

We do, of course, learn something about how Malick works. Experienced camera operators remark on how he doesn’t use artificial lighting, and we see shots of men ripping openings in thatched roofs to allow sunlight into a scene:

Christian Bale notes that Malick shoots 360 degrees around the space, so that crew members must be prepared to duck out of sight if he turns the camera their way. Others express surprise at the complete lack of storyboarding.

Being attached to the second unit also allowed the making-of team to show how the filmmakers cooperated with and included many Native Americans in the planning and execution of the film. It’s great to see American Indians not only pleased with the way their ancestors are being portrayed, but excited by being able to experience something of their ancestors’ way of life.

There’s a touching moment when Buck Woodard, a Native American advisor on the film, is being shown around the frame of an Indian dwelling by the production designer, Jack Fisk. Woodard looks around with a smile, and as Fisk moves off to the left, Woodard turns away from the camera and whispers almost inaudibly, “It’s just wonderful!”—clearly speaking to himself and not to Fisk or the microphone.

In short, this is a thoroughly ingratiating making-of—and how often do you see one of those?

One final note. Is it just me that’s getting annoyed by the time-lapse photography in supplements that are used to show lengthy actions like set-building or light-shifting really fast? That was kind of impressive for a while, but it’s a cliché by now. In The Social Network supplements the fast-motion is so fast that one can’t really see what’s going on. That sort of thing is cutesy, and it condescends to the viewer. (Even The New World supplements, which are much more casual, use this device once or twice.) I would like to see a set-building scene that actually shows something about how sets are built, not about how cool the supplement producers can make the process look.

The factors considered in these supplements tend to support David’s arguments in The Way Hollywood Tells It that there are basic continuities of style between traditional studio filmmaking and what some scholars have characterized as “post-classical” Hollywood.

The New World.

More revelations of film history on DVD

The Great Consoler.

Kristin here:

Upon returning from Vancouver, we found the usual mountain of mail awaiting us. Among the bills and ads were some very welcome items: a new flock of DVDs of considerable historical interest.

A German Documentary on Veit Harlan

After Leni Reifenstahl, Veit Harlan is the most famous of the directors who made films for the Nazi regime. He made Jud Süss, which is the only non-Riefenstahl Nazi film you might have seen apart from Triumph of the Will and (if you think it’s Nazi propaganda) Olympia.

Now Felix Moeller has made a documentary film, Harlan: Im Schatten von Jud Süss (“In the Shadow of Jud Süss,” c. 100 minutes). It’s available on a German DVD from Edition Salzgeber and can be purchased from Amazon Germany. (Beware, it’s coded Region 2, so you’ll need a multi-region player.) It has English subtitles, a feature some European DVD makers wisely include, since they know that there are a lot of us out here with multi-regional players. A region 1 version will also be released in the U.S. on November 23 and is available for pre-orders on Amazon.

Harlan is a fascinating film, both in terms of its subject matter and its strategies. It starts out in a fairly conventional way, showing Harlan’s grave, and then drops a few brief clips from Jud Süss in among shots introducing some of the director’s descendants. He was married twice and had five children, who in turn had children, and there are nephews and nieces as well. At one point one granddaughter draws a family tree to help us out. (The small accompanying booklet has a “who’s who” feature with photos to help us keep the family members straight. This booklet is entirely in German.)

Much of the early part of the film is taken up with the story of Harlan’s career making films for the Nazis, being found innocent after two trials in the post-war era, and continuing his filmmaking into the 1950s. A nicely ironic comparison is made between Harlan’s “I was just following orders” defense and the identical defense that Süss makes during his trial scene in the film.

Initially the relatives seem to be present in part to provide information and in part to comment on Harlan’s life. Later in the film, however, we realize that “the shadow of Jud Süss” falls over them as well, and they have reacted in a wide variety of ways. A expository motif that runs through the film is a visit paid by several of the younger family members to an exhibition on the film (see below), where they (and we) are shown documents and clips.

One son, Thomas, denounced his father publicly and for decades sought evidence to convict Nazi war criminals. (Thomas Harlan died last weekend; see David Hudson’s obituary here.) Kristian Harlan and Maria Körber, his half-brother and half-sister, criticize him for not keeping his attitudes toward his father in the family. Thomas’ daughter Alice works as a physiotherapist in Paris and realizes she does not share her grandfather’s guilt–yet she worries about some sort inherited taint. Another son, Caspar, became an anti-nuclear activist, along with his wife and three daughters. Two sisters, Maria Körber and Susanne Körber both married Jews, almost as if to make amends for their father’s implicit role in the extermination of these men’s families; neither marriage ended well. A niece, Christiane, married Stanley Kubrick, who as a Jew was both shocked and fascinated by her relationship to Veit Harlan; he at one point planned to make a film on the Nazi director. Christiane’s brother ended up producing some of Kubrick’s films.

One thing that struck me was the generational difference in the attitudes toward Jud Süss itself. The first generation of sons, daughters, nieces, and nephews find it powerful, reprehensible, and disturbing. One of the granddaughters, however, considers it “so cheesy, and really banal, too,” wondering how anyone in the 1940s could have taken it seriously. This seems to reflect an attitude that many young people have toward old films;  she might be just as dismissive of a classic John Ford film of the same era. It’s a good argument in favor of teaching students about the conventions of older films and helping them to watch them with more respect. Not knowing at least a little about the historical context could easily make younger generations not take the propaganda of the past any more seriously than they take the entertainment films of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. (One can’t fault the granddaughter too much; she belongs to the family of anti-nuclear activists.)

she might be just as dismissive of a classic John Ford film of the same era. It’s a good argument in favor of teaching students about the conventions of older films and helping them to watch them with more respect. Not knowing at least a little about the historical context could easily make younger generations not take the propaganda of the past any more seriously than they take the entertainment films of Hollywood in the 1930s and 1940s. (One can’t fault the granddaughter too much; she belongs to the family of anti-nuclear activists.)

The filmmakers had extensive access to good prints of several of Harlan’s major films. One, Der Herrscher (“The Master,” 1937), deals with a factory whose owner is a strong leader type. The frame at left shows off Harlan’s feel for crowds that made him the equivalent for fiction film to Leni Riefenstahl as a documentarist. (Indeed, one might suspect a bit of influence here.) There are also home movies, some taken behind the scenes during the filming of Harlan’s Nazi-era films. Munich archivist Stefan Drössler adds some historical perspective. The exhibition shown in the film provides glimpses of key documents.

Harlan could be quite useful in the classroom. Obviously courses on German history would benefit from it. Film history classes could show it in a unit on Nazi cinema, either in combination with or as a replacement for Jud Süss or one of the other major Nazi film. But it also gives an interesting perspective on the post-war decades and the ways in which guilt and expiation could linger across generations.

Thanks to my friend Marianne Eaton-Krauss for recommending this film to me!

[Added October 31: Critic Kent Jones has kindly written to point out that Felix Moeller is Margarethe Von Trotta’s son. Kent has written a piece on Veit and Thomas Harlan in the May/June 2010 issue of Film Comment.]

The launch of a Russian DVD series

The Russian Cinema Council (RUSICICO) has recently released the first five DVDs in its new “Academia” series. The first group comes from the Soviet silent and early sound era: Strike, October, Happiness, The Great Consoler, and Engineer Prite’s Project. They can easily be ordered on the company’s website. Googling will find a few smaller online companies in Europe that sell them, but they are not available (yet, at least) from the larger sites like Amazon.

[January 31, 2012: Hyperkino has announced that its DVDs can now be purchased at a British site, MovieMail. For more on Hyperkino, see here.]

A major feature of these discs is “Hyperkino,” a version in which numbers appear at intervals in the upper right; clicking on them summons up an explanatory text. For Strike, for example, one can read an explanation of the “Collective of the 1st Works’ Theater” when that phrase appears in the credits. (The complete text of the annotations for Engineer Prite’s Project have been printed as an article in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema [Vol. 4, no. 1, 2010].) These “footnotes” would be of interest to film students, mainly at the graduate level; they would be invaluable for lecture preparation. The Hyperkino version appears on the first disc of each two-disc set; the film without the feature appears on the other disc. Despite the fact that the text on the boxes are almost entirely in Russian, the films have optional subtitles in English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Portuguese; the Hyperkino notes are available only in Russian or English. The discs have no region coding.

A major feature of these discs is “Hyperkino,” a version in which numbers appear at intervals in the upper right; clicking on them summons up an explanatory text. For Strike, for example, one can read an explanation of the “Collective of the 1st Works’ Theater” when that phrase appears in the credits. (The complete text of the annotations for Engineer Prite’s Project have been printed as an article in Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema [Vol. 4, no. 1, 2010].) These “footnotes” would be of interest to film students, mainly at the graduate level; they would be invaluable for lecture preparation. The Hyperkino version appears on the first disc of each two-disc set; the film without the feature appears on the other disc. Despite the fact that the text on the boxes are almost entirely in Russian, the films have optional subtitles in English, French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Portuguese; the Hyperkino notes are available only in Russian or English. The discs have no region coding.

The prints of Strike and October are both the familiar step-printed versions. The visual quality is reasonably good.

(We did not purchase the Happiness disc, since the film had already been available in DVD and we’re not Medvedkin specialists.)

The most important contribution of the series so far has been to make two rare Kuleshov titles available to the general public for the first time. Engineer Prite’s Project was his first film. Previously it was available in archives in a print lacking intertitles. The story was so difficult to follow that the film seemed to be incomplete. Now, with the intertitles reconstructed and inserted into the film, it makes sense. It’s a short feature about industrial intrigue, notable in its mixture of traditional European tableau staging style and some sophisticated American-style editing that was a complete innovation for Russian cinema. The release of Engineer Prite’s Project on DVD fills a large gap in the history of the Soviet silent cinema, since it was the first film by one of the group that would form the Montage movement. Indeed, the fast cutting in a brief fight scene looks forward to that movement:

The DVD also includes a documentary, The Kuleshov Effect, made in 1969. It’s a helpful overview, with clips from the major films up to The Great Consoler, along with interviews with Kuleshov, scenarist and Russian Formalist critic Viktor Shklovski, and others. It’s just under an hour and would be a great teaching tool for a history or theory class.

If Engineer Prite’s Project is of interest mainly for its historical significance, The Great Consoler is perhaps Kuleshov’s masterpiece. The complex, multi-leveled narratives so popular in contemporary cinema have nothing on this film’s storytelling. It shifts among three levels with thematic parallels. In one, an abused, miserable shop girl (played by Alexandra Khokhlova, Kuleshov’s wife and leading proponent of the “biomechanical” school of acting) reads O. Henry short stories as escapism. In another, O. Henry himself is seen in prison (as he was in real life). In a third, we see a dramatization of his tale of convict Jimmy Valentine (“A Retrieved Reformation”). Each level is filmed in a slightly different style, and the moralistic lesson–those who suffer from exploitation under capitalism find only hollow consolation in popular culture–is somewhat undercut by the zestful stylization with which Kuleshov presents the sentimental tale of Valentine.

Chaplin (Slowly) Becomes The Little Tramp

On October 26, Flicker Alley is coming out with another of its big boxes of restored films. (Amazon has it available for pre-order.) This time it’s four discs containing a group of 34 of Charlie Chaplin’s Keystone-era films (of the 35 he made there). The press release describes the lengthy process of finding and restoring prints, which involved several archives: