Archive for the 'Experimental film' Category

Lines of sight and light

DB here:

Two weeks ago the film critic and historian Paul Arthur died. (An obituary is here.) Apart from being a warm and robust man, Paul advanced our understanding of cinema in important ways. He was a committed teacher and an energetic writer. For years it seemed that almost every issue of Film Comment or Cineaste contained an essay by him. Although he had an encyclopedic knowledge of film, he wrote with particular brilliance about experimental work. His book, A Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (2005), reflects a lifetime of sensitive study.

Paul was naturally on my mind as I watched the avant-garde films on display here at the Hong Kong Film Festival. I’ve mentioned some in an earlier entry, but I wanted to signal others that seemed to me especially fine.

A set by Ben Rivers had quiet poetic overtones. Very short (We the People lasts only one minute), they center on landscapes. I especially liked House (2007), a spectral suite of images derived from a miniature house Rivers contrived.

Lewis Klahr‘s Antigenic Drift (2007) was a lovely and funny meditation on, I think, air travel in a post-9/11 age. Glossy images of airports are haunted by wandering bar codes, boarding passes, and anatomy drawings. Tablets burst out of blister packs and gather in colorful rank-and-file formations. The film bears the traces of Klahr’s visit to Wisconsin, some details of which are here.

Lewis Klahr‘s Antigenic Drift (2007) was a lovely and funny meditation on, I think, air travel in a post-9/11 age. Glossy images of airports are haunted by wandering bar codes, boarding passes, and anatomy drawings. Tablets burst out of blister packs and gather in colorful rank-and-file formations. The film bears the traces of Klahr’s visit to Wisconsin, some details of which are here.

Ken Jacobs is a legendary figure in the avant-garde. Prolific, outrageous, and wide-ranging in his interests, he has been at it for fifty years. His oeuvre includes the casually goofy Little Stabs at Happiness (1960), the epic Star Spangled to Death (1957-2004), and the classic Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son (1969). There Jacobs dissected a 1905 Biograph film on the optical printer (see P. S. below), revealing not only isolated faces and gestures in its crowded shots but also abstract masses of light and dark, and even the grain of the film stock.

Across several years, Jacobs and his wife Flo have developed a mode of multiple-projection performance. Their Nervous System shows films at different speeds, halts them, drops down filters, even superimposes slightly different frames from prints of the same film, creating vivid 3-D effects. Such spectacles trigger comparisons to nineteenth-century impresarios of wonder: the conjuror who calls up ghosts, the sideshow entertainer whose calliope happen to be a movie machine. (1)

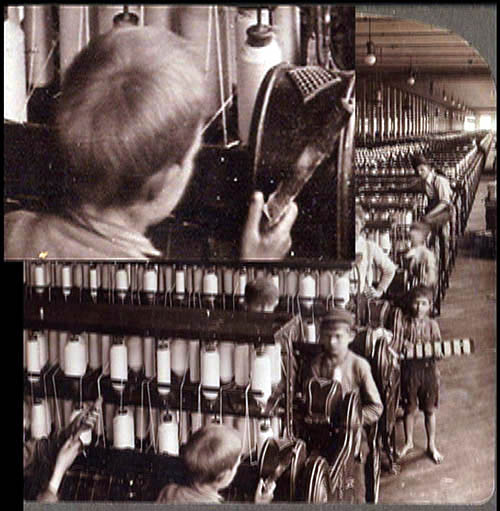

Capitalism: Child Labor (2006) might at first seem a rerun of Tom, Tom. A photograph shows men and boys at work in a thread factory. This dire image, with the workers’ flat expressions only adding to the sadness, might suffice in itself. But Jacobs takes the picture to pieces and shows us everything. He creates close-ups and long-shots, embedding them within one another to create games of scale. And then? Informed by Nervous System discoveries, Jacobs takes things a step further.

The picture originated as a stereoscope card. A stereoscope card consists of two side-by-side images, shot at angles corresponding to the difference between our eyes. Looking at the card through the viewer, the viewer has an illusion of 3-D. (Remarkably, my top illustration also features a factory scene.) For a detailed account of stereoscopy, see the Wikipedia entry.

Jacobs intercuts the two slightly different photos, often allotting only a single frame to each. With simple geometric shapes this procedure would yield “wiggle stereo,” as illustrated in the Wikipedia piece. But the density of the images evidently allows Jacobs to create a fluttering, nagging sense of volume. We seem to move just a bit around the figures and their workstations before popping back to our starting place, then launching again, endlessly. Somehow my brain thinks I’m spasmodically starting to circle through the factory.

This is why we’re right to call such films experimental. They often try to discover how our senses, our minds, and our emotions reveal themselves in their encounter with cinema. The goals are different, I grant you: Art exposes, science explains. But scientists should have a special eagerness to study avant-garde films. I can’t imagine anyone interested in filmic perception—and not just cognitivist film researchers—who wouldn’t find Capitalism: Child Labor a provocation to marvel at how our vision jumps to conclusions about depth. This movie makes us say Wow.

Song and Solitude, a 2006 film by Nathaniel Dorsky, was simply stunning. (2) In the Brakhage tradition, it’s woven out of lyrical shots of details seized and abstracted. Reflections, silhouettes, out-of-focus textures, veils and grids shedding unexpected ripples of light: everything seems radiant. Sometimes you recognize a familiar object, like a window screen pebbled with rain. Often, though, you have to ask: What am I seeing? And then Why don’t I ever notice this?

Dorsky’s Buddhist-influenced aesthetic, revealed in his book Devotional Cinema, drew this commentary from Paul Arthur:

Old School doesn’t describe it. Dorsky has achieved such a subtle mastery over the most basic means of cinematic expression–composition, duration, juxtaposition–that he can squeeze a wealth of emotional vibrations out of the silent, seemingly banal interplay of foreground and background objects. A formalist with a brimming, elegiac soul, Dorsky will gently rock your attitude toward cinematic landscape. His world is a sublime mystery measured by patience and unmatched visual insight.

I didn’t know Paul well. I met him around 1974, when we had a good conversation about landscape in Anthony Mann. We ran into each other occasionally over the years and corresponded a little.

His generosity to Kristin and me came through on several occasions. In a roundtable discussion published in October no. 100, he called attention to the fact that Film Art tried to remind students and teachers of the importance of avant-garde film. (3) In reply to an essay of mine in Film Quarterly, he sent overabundant praise but added several pointed questions that forced me to tighten up my argument. Most vividly, when I was criticized (some would say personally attacked) in the pages of Film Studies’ most prestigious academic journal, he was moved to write me with encouragement. Of my critic he wrote: “To hell with him if he can’t take a joke.”

Like a great many others, I will remember Paul with affection and admiration.

Song and Solitude.

(1) An engrossing interview with Jacobs can be found here.

(2) By the sort of coincidence I like, Song and Solitude also played the Wisconsin Film Festival, which I had to miss this year. Trusty Joe Beres of the Walker Art Center, still a Badger at heart, provides coverage.

(3) The discussion is here, but beyond the first page the material is proprietary.

P. S. 21 May 2009 Keith Sanborn wrote me to point out that, in a reply to Ed Halter (who discusses Anaglyph Tom (Tom with Puffy Cheeks) in Artforum), Ken Jacobs corrects the frequent claim that the 1969-71 Tom, Tom was made on an optical printer. No, says Jacobs; he rephotographed the movie from the screen. Here is the inimitable explanation Jacobs supplied to Halter.

The movie so pushes forward the character of film projection. Images explode out of darkness. Nor was I using a specialized analytic projector that with a steady flicker minimizes exchange of frames. I used what had been a common RCA home sound-projector, from the 1940’s, possibly the late 1930’s, but one with a hand-controllable clutch that allowed for slowing and even stopping the film. Freezing as it’s called but usually more like burning. A heat-shield would fall in place to protect the film from burning but would then darken the image, and so I removed it and took my chances with burning. The energy that is light was a featured and constant presence in the work. Darkness is death and the old reclaimed images constantly struggle against death to proclaim themselves. Release of energy, via intermittent projection or in the return of rambunctious ghost-actors, was much of what the work was about.

Thanks to Keith for calling my attention to this.

News from the fragrant harbor

DB here:

For those of you who have had problems connecting with this site: Sorry! Our server was down for a couple of days. Ironically, I was one of the last to climb on. Hence the slight delay in this posting from the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Whither Hong Kong film?

The Warlords.

Local cinema is still in the doldrums. As in most countries, Hollywood rules the box office. Production has dropped to about 50 releases last year, and the quality of what I’ve seen over the last week isn’t on the whole strong.

I’m told by a film professional who follows things closely that critics feel that 12-15 local films from 2007 are worth seeing and about 5 are actually good. Those five are Ann Hui’s The Postmodern Life of My Aunt, Derek Yee’s Protégé, Johnnie To’s Mad Detective, Yau Na-hoi’s Eye in the Sky, and Peter Chan’s The Warlords. It’s significant, my friend indicates, that almost never before has the same clutch of films been nominated for best picture, best screenplay, and best director at the Hong Kong Film Awards. (The awards will be given on 13 April.) “The falling industry has reached a plateau,” she remarks.

My sense is that Hong Kong cinema is sustained, however minimally, on three levels. As usual, there are the program pictures, chiefly urban action films and romantic comedies and dramas. These come and go, using local singers and TV stars, and allow theatres to keep their doors open. More creative are the films from local auteurs, principally Johnnie To Kei-fung. (Should I count Wong Kar-wai as a local filmmaker any more?) To’s Milkyway company turns out several worthy items per year, most directed by To. As I indicate in an earlier post, The Sparrow is their upcoming release; it’s also the best Hong Kong movie I’ve seen so far on my trip.

A third category includes the increasingly important China coproductions, nearly always military costume dramas. The emblematic shot: Mighty warriors on mighty steeds galloping toward the camera in a telephoto framing. Add spears, swords, shields, and slow-motion to taste.

The Warlords is the prime instance from last year, but it was preceded by The Myth (2005) and A Battle of Wits (2006). The genre was made popular by Mainland movies like Zhang Yimou’s overdecorated epics, and it has already furnished us two spring releases, An Empress and the Warriors (yes, you read that right) and The Three Kingdoms: Resurrection of the Dragon. Both are straightforward tales of military struggle, centering on loyalty and honor, with relatively little of the palace intrigue that usually furnishes plot motivation.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

An Empress, starring Donnie Yen, Leon Lai, and Kelly Chen, is pretty thin going, with overhasty fight scenes and Bumpicam coverage. The only engaging element, apart from the porcupine armor on display in the ads, is the fact that Leon plays a warrior who has retired from the world. He has for obscure reasons turned his patch of the forest into a launching pad for a hot-air balloon. Still, when ninja-like invaders assault his rickety scaffolding, we get a fairly effective action scene that carries a little of the impact of director Ching Siu-tung’s best movies.

The Three Kingdoms, a Korean-China coproduction directed by Hong Kong’s Daniel Lee, is a somewhat more impressive item. The plot traces the rise of a general (Andy Lau), aided by his mentor (Sammo Hung), and their confrontation with a rival general, whose cause is taken over by his daughter (Maggie Q). There is little characterization; everything hinges on honor, retribution, and service to one’s superior. A tranquil interlude with Andy’s love interest, a shadow puppeteer, is quickly forgotten in the rush to combat. The musical score channels Morricone, and as in Empress, it employs thunderous drumbeats, chanting male choruses, and a keening soprano. Inevitably, we also sense the influence of Wong Kar-wai in the meditative voice-over and the fight scenes (choreographed by Sammo) that recall Ashes of Time in their slurring and spasmodic rhythms.

Are such films really desired by Asian audiences, let alone Western ones? The jury is still out. Thanks to shooting in China and the diffusion of CGI technology, such genre pieces can be made for much less than Hollywood would spend. Three Kingdoms came in at less than US$20 million, which is twice the budget purportedly spent on Empress. But international sales of the genre are spotty, and audience uptake isn’t overwhelming. Somebody will have to tweak the formula creatively. Will it be John Woo, with Red Cliff? Odds are against it, but I’d like to be surprised.

Incorrigibly optimistic, I’m still looking forward to Ann Hui’s newest film, The Way We Are, premiering tonight, and Coffee or Tea, the collaboration of veteran director Shu Kei and his student Mandrew Kwan Man-hin. That’s the closing film of the festival.

Films briefly noted

Kabei–Our Mother.

Other festival highlights for me:

Please Vote for Me! A primary school in Wuhan is introduced to democracy when the teacher decides that the monitor will be elected by the class. There ensues a struggle all too reminiscent of U.S. political campaigns. We have sound bites, applause lines, political operatives (here, overzealous parents), scurrilous charges, personal attacks, and outright bribery. The collision of human nature and democratic ideals make this a charming and thoughtful movie. I can’t imagine anyone not enjoying it, if only for its reminder of how humiliation feels when you’re nine years old.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Observando al cielo. Jeanne Liotta’s ode to astronomical phenomena, at once scientific demonstration and lyrical tribute to the swiveling of the heavens. Visit her website here.

Mauerpark. From the Austrian collective Stadtmusik, Tati-goes-Betacam. A long shot of a snow-covered park is at first puzzling, then amusing, then engrossing.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

Alexandra. I nearly always like Sokurov. Yes, the films can be a little overbearing, but they have a certain weirdness that keeps them from pretentiousness. Here he gives us another story of family love. An old lady visits her grandson, who’s soldiering in the Caucasus. She rides in a tank, watches men clean their weapons, and putters doggedly about the bivouac. No big emotional climaxes, unless you count her encounters with other old ladies, who have set up a market selling shoes and cigarettes, and the moment when her soldier tenderly braids her hair.

The weirdness comes in the color values–sometimes blinding orange, sometimes bilious green reminiscent of Sovcolor—and in a murmuring soundtrack that blends machine whirs and conversation with barely discernible swoops of orchestral and vocal music. (Since Galina Vishnevskaya plays the old lady, are these fragments from her performances?) Nobody makes soundtracks quite like Sokurov; even an unadorned shot can take on urgency through the drifting whispers our ears struggle to make out.

Jim Hoberman has a discerning review here.

Elegy of Life. Rostropovich. Vishnevskaya. Also a pleasure to listen to, but much more straightforward. A documentary tribute to the great cellist/ conductor and the singer. Since I’m interested in Russian music and cultural politics, this was an unadorned pleasure. To hear Rostropovich compare Prokofiev the classicist with Shostakovich the Mahlerian was especially worthwhile.

Kabei—Our Mother. Yamada Yoji received a lifetime tribute at the Asian Film Awards. Having directed over seventy movies, including the long-running Tora-san series, he’s usually discussed in terms of sheer productivity. But his calm, grave period films Twilight Samurai (2002), Hidden Blade (2004), and Love and Honor (2006) have reminded people that he’s a fine director too. A man of restraint, he never shoots handheld, he seldom moves the camera, and he uses close-ups as high points, not default values. His sobriety makes the 1.85 ratio look as cleanly fitted to the human body as the 1.33 one is. “The last classical director,” Mike Walsh called Yamada after the screening, and it’s hard to disagree.

Kabei was for me the high point of the festival so far. It’s 1940, and a Tokyo intellectual is arrested for “thought crimes.” As he endures prison, his wife and two daughters struggle to make ends meet, with the help of Yamazaki, a loyal student. An epilogue reminds us of the now-elderly mother’s devotion to her husband.

That’s about it, but the poise of the performances and the simplicity of the presentation make this like a film from the era it portrays. I wish I had a DVD to illustrate the craftsmanship that Yamada brings to the very first shot, which unhurriedly introduces the family while the mother simply hangs out wash on the line. I wish I could show you how the moment that a badminton birdie lands on a rooftop pivots from comedy to sadness. I wish I could replicate the composition that hides a weeping Yamazaki from us—a shot that actually makes the audience burst into laughter. Who else would have the film’s biggest star, Tadanobu Asano, keep his back to us for an entire scene?

But maybe it’s better I don’t give such things away. Best to say: Despite all the other movies you see, Kabei shows one way that cinema can still be.

Finally, as antidote to my somewhat depressing diagnosis of the state of HK film, two items. First, the reception for Sylvia Chang‘s Run, Papa, Run showed off her lively charm. Here Sylvia, in black, is flanked by her stars, Yuhan Liu, Rene Liu, Lewis Koo, and Nora Miao, who played in Bruce Lee pictures.

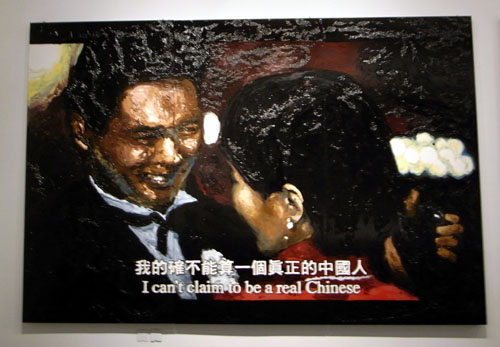

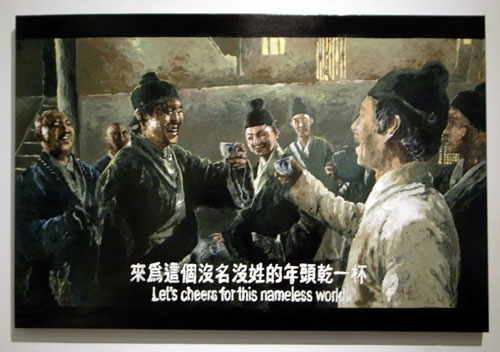

Second, in the entertaining exhibit Made in Hong Kong at the art museum, you will find the work of Chow Chun-fai, whose output includes large, glossy enamel images taken from movies, complete with letterboxing and subtitles (typically about Chinese/ Hong Kong identity). The blocky figures seem both chunkily monumental and somewhat decaying. One of Chow’s huge pictures, derived from Love in a Fallen City, surmounts this blog entry. Below is another, based on King Hu’s Dragon Inn.

More to come in a few days, including, I hope, thoughts on Maya Deren and an interview about sound design in Milkyway movies.

PS later on 27 March: I’ve just discovered a remarkable array of comments on Alexandra in this Criterion thread. John Cope‘s discussion is particularly admirable.

Manhattan: Symphony of a Great City

DB here:

In December Kristin and I attended a wide-ranging conference at Rome University devoted to “Exploded Narration”—the effects that digital technology has had on storytelling in film and television. As our host Vito Zagarrio put it, the question is one of continuity or rupture. Have new formats like HD, the Internet, and DVD revolutionized media storytelling? Or are they serving traditional approaches?

Many papers explored the “rupture” option, while Kristin and I offered presentations that emphasized continuity. You can find one version of my argument elsewhere on this site. Still, both of us also pointed up some innovations, or what I called “spillover” effects. As so often with such questions, the answer turned out to be complicated.

We enjoyed the conference, and one standout aspect was the presence of Amos Poe. Poe is probably best known for his first feature, Alphabet City (1985), and for his 16mm film on the Punk scene, The Blank Generation (1976). His Triple Bogey on a Par Five Hole (1991) has also attracted attention. For three decades Poe has worked as a director, producer, screenwriter, and teacher. The Sundance festival is playing Amy Redford’s The Guitar, which Poe wrote and coproduced.

We enjoyed the conference, and one standout aspect was the presence of Amos Poe. Poe is probably best known for his first feature, Alphabet City (1985), and for his 16mm film on the Punk scene, The Blank Generation (1976). His Triple Bogey on a Par Five Hole (1991) has also attracted attention. For three decades Poe has worked as a director, producer, screenwriter, and teacher. The Sundance festival is playing Amy Redford’s The Guitar, which Poe wrote and coproduced.

Amos was great fun. A soft-spoken man with a quick and wicked sense of humor, he enlivened our dinners at various ristoranti. He also spoke extensively about screenwriting, which he teaches at NYU and at NYU’s Florence program. Like many screenwriters, he’s extremely intelligent and articulate about his craft. Three examples:

*How to learn screenwriting? Get a script version of a film you admire. Read the first ten pages, then closely watch the first ten minutes of the movie. Go back and read the next ten pages, and go ahead and watch the corresponding ten minutes. And so on until the end. Do this with three first-rate films, and you will have a concrete, intuitive understanding of how a screenplay works.

*A screenplay, Amos points out, isn’t a short story or novel or play. It’s a movie in words. It must make the reader see and hear an imaginary film, and not only the action, either. Without indicating specific shots, the descriptions should suggest the flow of long-shots and close-ups (”Her lipstick leaves a smear on the cigarette butt”). “The screenwriter is a filmmaker.”

*Write sounds into the background of scenes, setting them up for fuller presence later. If a train becomes important late in the story, mention the wail of a distant train early in the screenplay. This sort of auditory planting quietly strengthens the structure of the story in your reader’s mind.

Amos must be a terrific teacher. I learned a great deal from his descriptions of contemporary film conventions, several of which I hadn’t noticed before. Don’t be surprised to find some of them creeping into future blogs.

Given Amos’ expertise in mainstream storytelling, the film he presented was quite a surprise. It’s called Empire II, and though you don’t normally call a three-hour movie a delight, I can’t think of a better word. After a week of tourism and no films, it was just the sensuous boost that my hungry eyes needed.

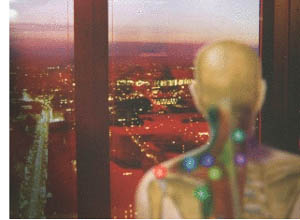

Man with a Video Camera

Poe’s apartment on Christopher Street yields a stunning view of the Manhattan skyline—the Chrysler Building, Jefferson clock tower, and of course the Empire State Building. He planted a Sony PD150 video camera at his window for a year, from 1 November 2005 to 31 October 2006, and took time-lapse shots. Through single-framing, he captured a total of 1 or 1 ½ seconds of every thirty seconds of real time. He shot traffic, people, skies, and the horizon. He did not look at the footage until after the year was up.

He wound up with sixty hours of imagery. He then made an absolute gesture. Using Final Cut Pro, he compressed all sixty hours into three. What was already highly elliptical, a string of tiny slices of action, became enormously accelerated.

Poe and his students then spent months blending up to forty tracks of music, spoken verse, and sound effects. It’s a crisp stereo mix, with remarkable audio-visual correspondences: whipping wind and ticking machinery sync up with snow and the tower clock. The music, which ranges from alt-rock to Keith-Jarrettish piano strumming, works sympathetically but not redundantly with the imagery. (No surprise that Poe has made music videos.) Shooting the film cost virtually nothing, but Poe spent about $100,000 for music clearances, though old friends like Patti Smith and Deborah Harry gave him their material for free.

The result is a city symphony, a lyrical tribute to the looks and sounds of New York. It joins the tradition of Walter Ruttmann and Dziga Vertov, as well as Paul Strand’s Manhatta (1921) and Jay Leyda’s Bronx Morning (1931). It also reminds you that Poe has roots in the downtown avant-garde. In 1972-1975, he often watched works by Jonas Mekas, Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, Bruce Baillie, and Jack Smith at Millennium Film Workshop, and he made films for its Friday night open screenings. As a result, Empire II carries premises of lyrical and Structural cinema into the digital era.

The conditions of production are at once subjected to strict guidelines—a single year, only views from the window, the 20x compression—and open to chance. As with the films of Ernie Gehr, chance becomes more felicitous when set within a rigid frame. “I needed to create a base for accidents to happen.” Poe refused to cut or rearrange what he had (”I don’t edit unless I get paid for it”) and so he was ready to accept what came out. “I had to let go of the result.” That result mixes smoothness and fracture; the moon arcs like a golf ball, but traffic hammers relentlessly in a way recalling the last sequence of Man with a Movie Camera. Every so often there are calm islands of blank frames, provided by Poe’s occasional neglect to set focus or exposure.

Poe’s Book of Hours and Days

The title pays homage to Warhol’s 1964 film, so often discussed and so little seen. In many ways, though, Poe gives us an anti-Empire. Instead of a silent film, sound, both aggressive and immersive. (The stereo tracks shoot noises bouncing across channels, swallowing you up.) Instead of a single night, a year’s time span. Warhol shot Empire at 24 frames per second but insisted on projecting it at 16, slowing up time; Poe’s single-frame sampling and frantic acceleration speed time up. Warhol used for the most part a single camera position and shot in long takes, but Poe presents a flutter of shots. The framing is steady, but what we see flickers and pulsates, creating superimposition effects comparable to Ruttmann’s and Vertov’s slashing diagonals.

Warhol was withdrawn and impersonal, but Poe turned on the camera when he spotted something that looked interesting. He felt free to focus, reframe, zoom, and shift camera position for different angles on the life beyond his balcony. Likewise, the automaton Warhol (”I’d like to be a machine”) is counterposed to Poe’s more organic sensibility. He never lets us forget the flowers twitching on his windowsill, and their growth and rearrangements become traces of his daily life in the apartment.

The rules are simple and viewer-friendly. We instantly recognize the trappings of city life; we know the cycles of the seasons and the shifts between night and day. This cogent structure throws all our attention on what we see from moment to moment, and how we see it.

The Empire State Building and the skyline around it, along with the flowing clouds, remain stable reference points for a flurry of visual transformations. The taxis and pedestrians we glimpse move in jagged, incomplete rhythms very different from the smooth flow of fast motion in Godfrey Reggio’s films like Koyaanisqatsi.

As you see, high angles, plays of focus, and tight framings provide energetic abstraction. Flaring exposure makes the Building look like it’s in flames, triggering echoes of the 9/11 attacks.

When the weather changes, the light does too. Raindrops become not only a pebbly surface on the windows but tiny filters. As with Warhol’s films, we have to change our conception of what counts as an event. Slight differences of framing and texture become visual epiphanies. Rain can be gray-green, and snow can go pale red. At times, the steeple clock face in the lower right becomes an imperturbable timekeeper, a sort of pictorial timecode, reminiscent of the clock in the corner of the shots of Robert Nelson’s Bleu Shut (1971).

Spring comes about halfway through. It’s as lyrical as you’d expect, but again the colors startle. If snow can be red, then budding trees can be blindingly white.

As in Ives’ Holidays Symphony, the festive iconography of Americana is made somewhat dissonant. July Fourth fireworks become splinters, and the slurred, jerky figures in the final Halloween chapter recall Mekas’ Notes on the Circus. Now shooting more continuously, with handheld shots and bumpy pans and zooms, Poe lets his 20x compression turn the parading ghosts, skeletons, nuns, and dark angels into scurrying hallucinations, complete with cellphones.

Empire II is at once exuberant and tranquil. What a pleasure to find a film devoted simply to seeking out beauty in everyday surroundings. “She celebrates the small,” sings Jimmie James while we see snow lashing the sidewalks. So does Poe. He has said that he made the film at a difficult period of his life, but what he has given us, I think, is jubilation.

PS 22 Jan: For more on Empire II, including a trailer, go to amospoe.com.

Things to like about looking

13 Lakes.

“What I like about looking is how many ways there are to see the same thing.”

Sadie Benning

DB here. Today no extended essay, just some jottings.

Some day I really must do an extended tribute to the Eureka/ Masters of Cinema DVD line. To call it the UK Criterion is partly right, given the painstaking transfers and the ample supplementary material. But Eureka ventures into some very fresh territory. A company that puts out the terminally peculiar Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969) as well as a double-disc set of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff and Gion Bayashi deserves points for audacity.

Some day I really must do an extended tribute to the Eureka/ Masters of Cinema DVD line. To call it the UK Criterion is partly right, given the painstaking transfers and the ample supplementary material. But Eureka ventures into some very fresh territory. A company that puts out the terminally peculiar Funeral Parade of Roses (Toshio Matsumoto, 1969) as well as a double-disc set of Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff and Gion Bayashi deserves points for audacity.

A recent batch of Eureka releases:

*Two cult animation items by René Laloux, Gandahar and Les maitres du temps. Fans of Fantastic Planet and the bande dessinée artist Moebius will snap these up, as much for the large booklets as for the discs.

*Then there’s Nosferatu. You say we’ve already got enough? Nope. First, we can never have too many of this, one of the greatest of silent films. Second, this version looks scarily definitive: a two-DVD set with the Murnau-Stifung restoration and the original score, plus a documentary, plus a book including some primary material along with essays by Enno Patalas, Gil Perez, Thomas Elsaesser, and Craig Keller.

*Sticking with Murnau (who directed, some say, in a white lab coat), Eureka offers a double-disc set of Tabu, also from the Murnau-Stiftung and with previously unseen scenes and title cards.

*Finally, there’s Peter Watkins’ Edvard Munch in its long version, with a booklet including a Watkins “self-interview.”

Unbelievably, many more great movies are on the way. Check the catalogue and preview lineup here.

Also from overseas, the Austrian Filmmuseum adds a new title to its Synema book series, alongside Alexander Horwath’s remarkable dossier on Sternberg’s Case of Lena Smith (discussed in an earlier entry here) and many other books on experimental cinema. It’s the first book devoted to James Benning.

Also from overseas, the Austrian Filmmuseum adds a new title to its Synema book series, alongside Alexander Horwath’s remarkable dossier on Sternberg’s Case of Lena Smith (discussed in an earlier entry here) and many other books on experimental cinema. It’s the first book devoted to James Benning.

I have a personal interest. I met Jim when I came to Madison in 1973. He was working on his MFA in film and art, and he was one of four teaching assistants assigned to me. There was Doug Gomery, already an impressive film historian, soon to go on to fame for his work on the US film industry. There was Brian Rose, one of the most alert cinephiles I ever met, and one of the funniest. There was Frank Scheide, already an expert on Chaplin, Keaton, and their peers. And there was Jim, a master mathematician (helpful for computing grade curves) and the only filmmaker in the bunch. Jim and Frank, both serene, had a calming influence on the rather hyper Rose, Gomery, and Bordwell. It was a great team, my Dirty 1/3 Dozen, and I remember our collective grading sessions fondly.

Jim had already made Time and a Half, but his most famous works, starting with 81/2 x 11 (1974), were yet to come. He left Madison and went on to teach filmmaking at several places, settling finally at Cal Arts. I kept in occasional touch with him and his work. He visited our Wisconsin Film Festival with his remarkable, politically charged Four Corners, El Valley Central, and Los. I’ve seen him more frequently in the last few years because turn up at the same film festivals—me as an observer, him showing gorgeous and provocative films like 13 Lakes, 10 Skies, and One Way Boogie Woogie/ 27 Years Later.

So the book, edited by Claudia Slanar and Barbara Pichler, is very welcome. It just arrived, so I haven’t had a chance to read it through, but I signal it to all those interested in a filmmaker who has been enthralling and surprising us for thirty-five years. Apart from a career chronology and a complete filmography, it features essays by Julie Ault, Sharon Lockhart, Volker Pantenburg, Dick Hebdige, Amanda Yates, Scott MacDonald, Allan Sekula, Michael Pisaro, Nils Plath, and of course Sadie Benning, a mean hand with Pixelvision. Lockhart supplies lustrous shots of some Wisconsin beer bottles in Jim’s collection.

Speaking of books, not beer, the Korean Film Council has just published a series of trim books on major directors, both classic and contemporary. Each volume includes a detailed filmography and a lengthy interview. Some volumes are through-written by a single author, others consist of analyses and appreciations by various hands, including major Korean critics and Asian cinema expert Chris Berry.

Speaking of books, not beer, the Korean Film Council has just published a series of trim books on major directors, both classic and contemporary. Each volume includes a detailed filmography and a lengthy interview. Some volumes are through-written by a single author, others consist of analyses and appreciations by various hands, including major Korean critics and Asian cinema expert Chris Berry.

The directors honored are Kim Dong-on, Im Kwon-taek, Lee Chang-dong, Kim Ki-young, Park Chan-wook, and Hong Sang-soo. This last volume, edited by Huh Moonyung, includes an homage by Claire Denis and a small essay by me, “Beyond Asian Minimalism: Hong Sang-soo’s Geometry Lesson.”

Books in the series may be ordered here.

Speaking, again, of books. . . The paper edition of Phillip Lopate‘s American Movie Critics: An Anthology from the Silents until Now (The Library of America) has just come out. I found reading the first edition addictive, like eating peanuts and M & Ms. Now we need a second volume including Frank Woods (a critic close to Griffith), Welford Beaton, and other less-known early writers.

In the meantime, the new edition has grown to include an essay on Fincher’s fine Zodiac by Nathan Lee and internet pieces from Stephanie Zacharek (Salon.com) and your obedient servant. I’ve never imagined an essay of mine in a collection that includes my teenage idols Mencken, Macdonald, Sontag, and Sarris, so this volume amounts to a swell early Christmas present. Thanks to Mr. Lopate and Geoffrey O’Brien for all their help.

Speaking, yet again, of books. . . A plug is in order for Scott Higgins’ meticulous, engagingly written Harnessing the Technicolor Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s, just out from Texas. I sat on Scott’s dissertation committee, and I was impressed by his imaginative research methods (e.g., using Pantone swatches as an objective measure of color hues in movies) and his sensitive attention to the way the movies look. Nobody before Scott has analyzed color in film so carefully. Scott is also attentive to production practices, so filmmakers interested in the history of technology should find a lot to chew on here. Several pages of original Technicolor frames support Scott’s case in graceful detail. No beer bottles, however.

More books from Wisconsin scholars: The above-mentioned Doug Gomery has a new book due out early next year, A History of Broadcasting in the United States. Lea Jacobs’ The Decline of Sentiment: American Film in the 1920s should follow soon. I’ve read the latter already, but both are without doubt worthy of your attention. If you like your American film history at once informationally solid and intellectually daring, you will like these items. Neither Doug nor Lea is a fan of conventional wisdom.

Finally, for fans of Hong Kong cinema: Johnnie To and Wai Ka-fai‘s Mad Detective (I filed a note on it from Vancouver) has been a hit in Hong Kong, beating Beowulf. An analog Lau Ching-wan can thrash a digital Ray Winstone any day of the week. Milkyway Image’s boundlessly energetic Shan Ding has set up a Facebook page as a place to chat about movies and, one hopes, to keep us apprised of developments in Mr T’s upcoming remake of Melville’s Cercle Rouge.

Mad Detective.

PS: Just learned about an informative interview with Jim Benning here, with more ravishing shots from 13 Lakes. This entry also includes several other links to web discussions of Jim’s films.