Archive for the 'Experimental film' Category

The ten best films of … 1926

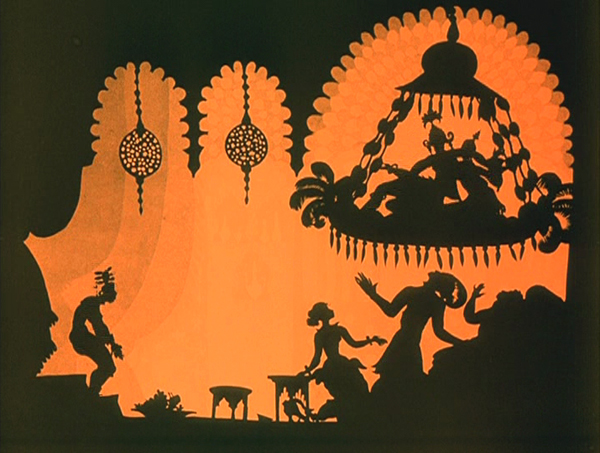

The Adventures of Prince Achmed.

Kristin (with some help from David) here:

David and I have been offering this greatest-of-90-years-ago series almost as long as this blog has existed. For earlier annual entries, see 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, and 1925.

I approached 1926 with the assumption that it would present a crowded field of masterpieces; surely it would be difficult to choose ten best films. Instead it turned out that some of the greatest directors of the era somehow managed to skip this year or turn in lesser films. Eisenstein had two masterpieces in 1925 but no film in 1926. Dreyer made a film that is a candidate for his least interesting silent feature, The Bride of Gromdal. Chaplin did not release a film, and Keaton’s Battling Butler, while a charming comedy, is not a plausible ten-best entry. The production of Lang’s Metropolis went over schedule, and it will appear on next year’s list, for certain.

Still, the Soviet directors were going full-tilt by this time and contribute three of the ten films on this year’s list. French directors on the margins of filmmaking created two avant-garde masterpieces. Two comic geniuses of Hollywood already represented on past lists made wonderful films in 1926. A female German animator made her most famous work early in a long career. I was pleased to reevaluate a German classic thanks to a sparkling new print. Finally, Japan figures for the first time on our year-end list, thanks to a daring experimental work that still has the power to dazzle.

The Russians are coming

Vsevolod Pudovkin’s Mother was a full-fledged contribution to the new Montage movement in the Soviet Union. By the 1930s, that movement would be criticized for being too “formalist,” too complex and obscure for peasants and workers to understand. Nevertheless, being based upon a revered 1906 novel of the same name by Maksim Gorky, Mother was among the most officially lauded of all Montage films. It tells the story of a young man who is gradually drawn into the Russian revolutionary movement of 1905. His mother, the protagonist of the novel, initially resists his participation but eventually herself joins the rebellion.

Along with Potemkin, Mother was one of the key founding films of the Montage movement. Its daring style is no less impressive now than it must have been at the time. One brief scene demonstrates why. Fifteen years before Mother, D. W. Griffith was experimenting in films like Enoch Arden (1911) with cutting between two characters widely separated in space, hinting that they were thinking of each other. By 1926, Pudovkin could suggest thoughts through editing that challenged the viewer with a flurry of quick mental impressions.

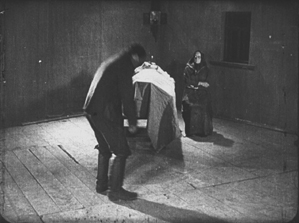

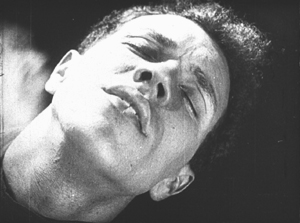

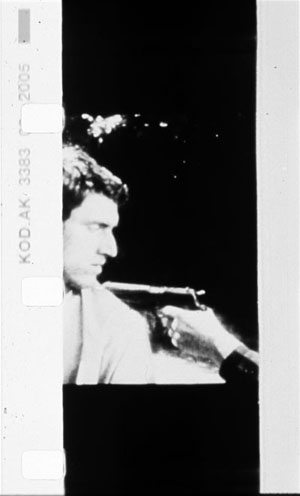

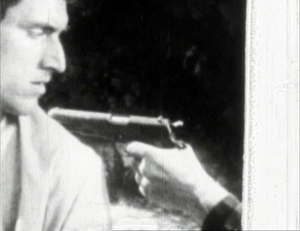

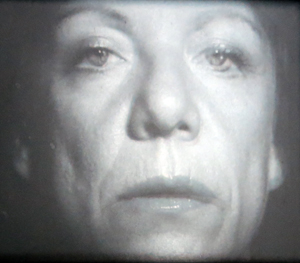

As the Mother sits beside her husband’s dead body, her son, a participant in the 1905 failed revolution, comes in. He is about to bend down and open a trap-door in the floor (73 frames). A cut-in shows her horrified reaction (12 frames), and there follows a brief close shot of some guns she had seen him hide under the floor in an earlier scene (11 frames). Even shorter views of a man clutching his chest (8 frames), two jump-cut views of the dead husband (3 frames and 2 frames), and a tight framing of the son being shot follow (8 frames). We return to her face, registering even greater horror (15 frames). A return to the initial long shot shows her leaping up to try and stop her son from taking the guns out to participate in a seditious act (31 frames).

The series of five shots goes by in a few seconds, and we are challenged to grasp that the guns are a real memory, while the shots of the man’s chest and her son’s anguished face are visions of what might happen. The shots of her husband’s body suggest that she could soon end up sitting by her son’s corpse as well. The jumble of recollection, imagination, and reality are remarkably bold for this relatively early era.

Mother also contains two of Pudovkin’s most memorable scenes, the breaking up of ice in the spring as a symbol of the Revolution and the final violent attack on the demonstrators, including the heroine.

Mother was released on DVD by Image Entertainment in 1999, but it seems to be very rare. An Asian disc, perhaps a pirated edition of the Image version, is sold on eBay. I’ve never seen the film on DVD and can’t opine on these. The time is ripe for a new edition.

Pudovkin was one of the filmmakers who had studied with Lev Kuleshov during the early 1920s, when Kuleshov made the famous experiments that bear his name. Pudovkin played the head of the gang of thieves in The Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks, which I included in the ten-best list of 1924.

Kuleshov had moved on as well to direct his most famous film and probably his best silent, By the Law, based on Jack London’s story “The Unexpected.” Set in the Yukon during the gold rush, it involves five people who are cooperatively working a small claim and discover gold. Taking advantage of a warm autumn, they stay too long and are trapped for the winter. One of the men kills two of the others, and the heroine, Edith and her husband Hans are left to determine the fate of the killer, Dennin. Edith insists on treating him strictly according to the law. After enduring the harsh winter and a spring flood, the couple finally act as judge, jury, witnesses, and, after finding Dennin guilty, executioners.

The great literary critic and theorist Viktor Shklovsky (one of the key figures of the Russian Formalist school) adapted the short story, condensing it by eliminating the opening section of Edith’s backstory and a few scenes in which a group of Indians appear occasionally to help the prospectors. The result is a concentration on the tense drama of a three people trapped together in a tiny cabin.

In the 1924 entry, I mentioned that Kuleshov’s team emphasized biomechanical acting and that Alexandra Kokhlova was adept at eccentric acting. She delivers a bravura performance here, as Edith moves closer to a breakdown as the months go by.

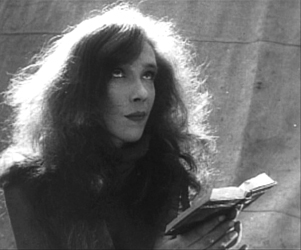

Kuleshov also puts into practice the experiments in imaginary geography that his classes had made. Although in this film he didn’t unite shots made in widely separate spaces, he did favor scenes built up of a considerable number of detail shots before finally revealing the entire space in an establishing shot. Edith, for example, though glimpsed briefly asleep early on, is introduced in a later scene by a shot of her boots and Bible, followed by a shot of her head as she read the Bible. The scene also contains close shots of the other characters before a general view of the cabin interior shows where each of them is.

The scene of the execution includes one of the most famous images of the Monage movement, a framing with the horizon line at the bottom edge of the frame and the sky dominated by trees (see bottom). Any number of framings of tall features such as trees and telephone poles against a huge sky appeared in Montage and non-Montage films, and this device became so common as to be a trait of the Soviet cinema of the late 1920s and early 1930s.

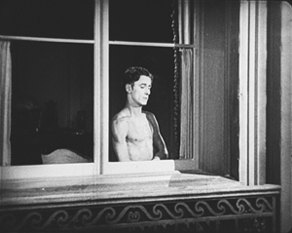

The desire to hide the actual hanging led Kuleshov to stage is behind the larger of the two trees, as Edith and Hans struggle to carry out their sentence on Dennin. This leads to some eccentric framings, such as our view only of Edith’s legs as she teeters on the box where Dennin stands, presumably adjusting the noose (see top of this section).

A beautiful print of By the Law is available on DVD from Edition-Filmmuseum.

Grigori Kozintzev and co-director Leonid Trauberg did not study with Kuleshov, but they shared a passion for eccentricity. Having started out in the theater, in 1921 both contributed to the “Manifesto for an Eccentric Theater,” a dramatic approach based on popular forms like circus and music-hall. In 1922 they founded the “Factory of the Eccentric Actor” group and two years later transformed it into FEKS, devoted to making films.

The Overcoat (also known in English as The Coat), their second feature, was based on a combination of two short stories by Gogol, an author whose grotesque creations were very much in tune with their own tastes. It tells the story of a poor, middle-aged low-level government clerk, Akaky Akakievich, who is bullied over his shabbiness, particularly his worn-out overcoat. Scrimping to buy a new one, he finally purchases a magnificent new coat and finds his status suddenly raised–until the coat is stolen.

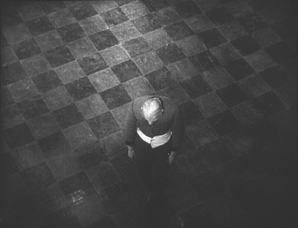

Andrei Kostrichkin was a mere twenty-five years old when he played the fiftyish clerk, but he was highly effective and provided another model of the eccentric actor. As Akakievich he stands with bent legs and twisted torso, as if flinching away from a blow, and walks in tiny steps along perfectly straight lines through the hallways in his office building. When he applies to a Person of Consequence for help in recovering his stolen coat, the official leans over his desk to look downward, with a high-angle point-of-view framing of Akakievich appearing dwarfed by the other’s superiority.

The script of The Overcoat was adapted by another Russian Formalist critic and theorist, Yuri Tynjanov.

Unfortunately The Overcoat does not seem to be available on any form of home video.

Petit mais grand

The IMDb lists 23 directing credits for Dimitri Kirsanoff from 1923 to the year of his death, 1957. He is largely remembered, however, for one film, the 37-minute Ménilmontant, a melodrama about the travails of two sisters orphaned as children by a violent crime. Each is later seduced by a callous young man who leaves the heroine a single mother and her sister reduced to prostitution. It belongs to the French Impressionist moment. (We deal with Impressionist films in other entries: La roue, L’inhumaine, L’affiche, Coeur fidèle, The Smiling Madame Beudet, Le brasier ardent, Crainquebille, and El Dorado, as well as DVD sets of Impressionist films by the Albatros company and by director Jean Epstein.)

The story itself is simple and indeed might be thought clichéd were it not for two factors. First, there’s the performance of the delicately beautiful Nadia Sibirskaïa as the protagonist. There’s also the lyrical, melancholy use of the settings, initially in the countryside and later in the desolate working-class Parisian district whose name gives the film its title. The simplicity of the narrative also makes it one of the most successful of the attempts to tell a story visually, eschewing intertitles.

The film’s most famous scene is its abrupt, shocking opening. With no establishing shot, there is a series of rapid shots of details of faces, hands, a window, and an ax, during which we can barely discern that a man has committed a double murder. The spectator cannot possibly know who these people are and why the murders occur.

Instead of offering an explanation, the action then shifts to two little girls playing in the woods. As they return home, the camera begins to concentrate on one of them, apparently the younger, as she arrives at the murder scene and reacts in horror. Kirsanoff presents her expression in a series of five shots, linked by what David has termed axial cuts, from medium shot to extreme close-up as she gradually realizes what has happened.

There had certainly been axial cuts before this, including in Potemkin, but Kirsanoff probably went further than anyone of the era by including so many shots, by making each so short, and by moving his camera forward in such small increments. It is difficult to notice every cut, particularly the one from the third to the fourth shot, and the effect adds an unsettling quality to an already intense moment.

After this opening, a funeral scene reveals through labels on the grave that the murdered man and woman are the children’s parents. We might have suspected that the killer was a jealous husband discovering his wife with her lover. As it is, we never learn whether the crime was the result of a love triangle or the random act of a madman.

The rest of the film establishes the sisters now grown up, working in a workshop making artificial flowers and sharing a small flat in Menilmontant. The heroine’s brief romance leads to a baby, and superimpositions and other Impressionist techniques depict her despair and contemplation of suicide. Beautifully melancholy atmospheric shots of the streets of the neighborhood punctuate the action and underscore the dreariness and hopelessness that the heroine faces. The ending, though an improvement in the heroine’s lot, does little to dispel the overall grimness of the story.

Menilmontant is included in the out-of-print set “Avant-garde – Experimental cinema of the 1920s & 1930s.” It has been posted twice on YouTube in a low-rez format.

Even shorter is Anémic cinéma, the only venture into film directing by the great French Dadaist, Marcel Duchamp. It’s hard to compare a roughly seven-minute abstract film with narrative features, but this short is so innovative and influential that it’s also hard to leave it off the list.

Duchamp went through a phase of spinning artworks, including some “Rotoreliefs” that he attempted to sell as toys. These were similar to some Victorian optical toys, such as the Phenakistopscope and the bottom disks of Zoetropes. See Richard Balzer’s website for a collection of such devices, as well as “The Richard Balzer Collection” on tumblr, which contains gifs that animate some of the disks, done by Brian Duffy. Some of these resemble the spinning spirals and embedded circles that Duchamp used for his short. (See the top of this section.)

These spinning abstract circular images alternate with slowly spinning disks with sentences laid out as spirals. These involve either alliteration or puns or both. Unfortunately the English subtitles cannot render these in a way that conveys the original intent. For example, “Esquivons les ecchymoses des esquimaux aux mots exquis” becomes “Let us dodge the bruises of Eskimos in exquisite words.” The meaning is the same, and even the echo of the first syllables of “Eskimos” and “exquisite” is retained. Nevertheless, the similar syllables in two other words in the original are lost, as are the echoes of “moses,” “maux,” and “mots.” It is rather as though someone attempted to render “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers” into another language quite literally. (The Wikipedia entry includes a complete list of the sentences in French.)

Duchamp’s purpose was presumably to create an artwork with minimal means, including quasi-found objects, the disks he had made for another purpose. His idea is clearly reflected in the title, Anémic cinéma, which suggests a weakness or thinness of means. “Anémic” is also an anagram for “cinéma.”

Anémic cinéma is available in the same collection as Menilmontant, linked above. it is also available in the similarly out-of-print set, “Unseen Cinema.” There are numerous versions on YouTube, varying in quality. Some of these have been manipulated by other artists.

Lloyd and Lubitsch

Though Chaplin and Keaton might have had off-years in 1926, Harold Lloyd did not. Over the past several years, Lloyd has gradually been gaining the admiration he deserves. He used to be known largely for Safety Last (1923) and The Freshman (1925), two excellent films which, however, are not his finest. Girl Shy (1924) and The Kid Brother (1927) are better known now for the masterpieces they are. For Heaven’s Sake (directed by Sam Taylor), which clocks in at a mere 58 minutes, is just as good.

Lloyd plays a breezy millionaire, J. Harold Manners, who unintentionally helps Brother Paul found a mission in the downtown slums of Manhattan. He falls in love with Hope, the missionary’s daughter, and decides to help out around the place. By this time Lloyd was known for his spectacular chase scenes, and there are two here. Initially he puts a twist on the chase, luring a growing crowd of criminals into racing after him, ending in the mission. Gaining their respect, Harold makes the mission a happy social center.

The romance provides one of my favorite comic intertitles, leading into a love scene: “During the days that passed, just what the man with a mansion told the miss with a mission–is nobody’s business.” The love scene in turn includes a visual joke that emphasizes the rich boy – poor girl contrast.

Harold’s rich friends hear that the pair are to be married and determine to kidnap him to prevent the inappropriate match. The result is a lengthy chase through the streets of Manhattan, with the drunken thugs rescuing Harold and using a variety of means to get him back to the mission in time for the wedding–as when the drunken leader of the group demonstrates his tightrope-walking abilities on the upper railing of a double-decker bus (see above).

Two years ago, when I put Girl Shy on my list, the New Line Cinema boxed set of Lloyd films was out of print and hard to find, and the separate volumes appeared to be going out of print as well, with Volume 1 not being available at the time. The situation has changed, and the boxed set, though apparently still out of print, is now available at reasonable prices from various third-party sellers on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. The set contains a “bonus disc” with extras, including interviews and home movies. The same is true for the three individual volumes (here, here, and here). For Heaven’s Sake is in Volume 3.

Inevitably, coming directly after Lady Windermere’s Fan, probably Ernst Lubitsch’s greatest silent film, So This Is Paris does not quite live up to its predecessor. Still, it’s a very fine, clever, and funny film, and it marks Lubitsch’s last appearance in these lists until sound arrives.

The opening scene, running nearly twenty-five minutes, is as good as anything Lubitsch did in this era. Set in Paris, it’s a slow build-up of misunderstandings and deceptions involving two affluent couples in apartments across the street from each other. One couple, Maurice and Georgette Lalle, are practicing a melodramatic dance in Arabian costumes. Their marriage seems to be a rocky one. Across the street, Suzanne Giraud is reading one of the lurid “Sheik” novels that were popular at the time, involving “burning kisses” in its final scene. Put into a romantic mood by this, she looks out her window and sees the head of a man in a turban at the window opposite–Maurice relaxing after his strenuous rehearsal.

Her husband Paul arrives home, and she kisses him passionately. Apparently not used to such affectionate greetings, he is puzzled until he, too, looks out the window. By now Maurice has doffed his turban and necklaces and appears to be not only naked but also examining a piece of his anatomy.

Paul jumps to the conclusion that this sight is what caused Suzanne’s unaccustomed display of passion. He calls her to the window, and we see Maurice in depth through the two windows.

Suzanne then asks if Paul is going to stand for such a thing, and he goes to the other apartment to confront Maurice. Instead he finds Georgette, who turns out to be an ex-lover of his. She introduces him to Maurice, who is very friendly and charms Paul. The latter who returns home and claims that he has beaten Maurice and even broken his cane on him, though in fact he had simply forgotten it. Shortly thereafter Maurice visits Suzanne to return the undamaged cane and takes the occasion to flirt with her. It’s a beautifully plotted and developed farcical scene. The film is based on a French play and could easily have become stagey in its adapted form. Yet the byplay between the two apartments via the windows allows Lubitsch to avoid any such impression; the misunderstandings based on optical POV recall the racetrack scene of Lady Windermere.

The rest of the film develops the two potentially adulterous affairs, primarily with Paul secretly taking Georgette to the Artists’ Ball. Here Lubitsch uses an elaborate montage sequence to convey the wild party, with superimpositions and shots taken through prismatic lenses.

Such sequences were primarily developed in German films and were still fairly rare in American ones in 1926. Similar techniques convey Paul getting drunk on the champagne he and Georgette are awarded when they win a dance contest–the announcement of which on the radio broadcast of the ball alerts Suzanne to her husband’s presence there with another woman.

So This Is Paris is less famous than Lubitsch’s earlier American comedies primarily because it has never appeared on DVD. Marilyn Ferdinand, in a blog entry that gives a detailed description of the film, writes that Warner Bros. claims not to own the rights to the film anymore and therefore has made no effort to bring it out on home video. On the other hand, a four-minute excerpt of the dance montage sequence was included in the Unseen Cinema set (disc 3, number 18), and the credit there is “Courtesy: Warner Bros., Turner Entertainment Company.” Whatever the rights situation is, a home-video version of this film is in order. A beautiful 35mm print is owned by the Library of Congress, so there is hope.

Two German flights of fancy

I must confess that I was disappointed the first time I saw F. W. Murnau’s Faust, and I have never warmed up to it in later viewings. I am delighted at having occasion to look at it again for this 1926 list, since a recently discovered and restored print reveals that the main problem before was the poor visual quality of the print formerly in circulation.

Different local release prints survived in a number of countries, but there were basically two original versions made: the domestic negative for German release and the export negative. These were shot using two camera side-by-side on the set, as was the standard practice in much of the silent era, given the lack of an acceptable negative-duplicating stock. The primary camera contributed most of the shots to the domestic negative, though in some cases where the second camera yielded a superior take, that was used in the domestic negative. Conversely, inferior takes from the primary camera sometimes made their way into the export negative. The result, as we now know, was that both the visual quality and in many cases the editing of the scenes was markedly different in the two negatives.

The version familiar for decades originated from the export negative. Recently the domestic negative was rediscovered, and the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung restored the that version using the that negative, supplemented with material from a variety of other prints. The result closely approaches the original German release version, including the original decorated intertitles. The contrast in quality between this restoration and the old, familiar Faust is remarkable.

Given how dark the film is, details in the backgrounds could easily be lost. The scene in which Faust is called to help a woman dying of the plague is revealed to have dramatic staging in depth against a very dark room contrasted with the stark foreground underlighting of the woman’s haggard face. Faust enters from behind the daughter and comes forward to her, after which his movement is balanced by the daughter retreating into that same dark background.

The famous aerial journey of Mephisto and Faust from Germany to Italy (below left) always looked rather hokey, but the detail revealed in the extraordinarily extensive model makes it far more impressive. Similarly, when one can actually see the sets, visual echoes become apparent. For example, Faust first encounters Gretchen and follows her into the church, where he finds himself barred from entering by his pact with Mephisto. Later, when Gretchen has been abandoned, she laments when not permitted to enter there.

No doubt some motifs of this sort were visible in the earlier print, but their clarity here enhances both the beauty and the craft of Murnau’s film.

Faust is available in several editions on DVD and Blu-ray. DVDBeaver ran a detailed comparison among seven of these, including a selection of frame grabs. To my eye, the 2006 DVD “Masters of Cinema” version of the domestic print, released by Eureka!, looked the best. (The two-disc set also includes the export version.) The Blu-ray from the same source, released in 2014, looked slightly darker. The box for the Blu-ray also includes the DVD, however. These releases are Region 2. The film is available on Blu-ray in the USA from Kino.

Both Eureka! releases’ supplements include a booklet, a commentary track, a Tony Rayns interview, and a lengthy comparison of the domestic and export versions. One particularly striking example is drawn from the scene in which Mephisto talks with Gretchen’s brother in a beer hall, with the domestic version on the left.

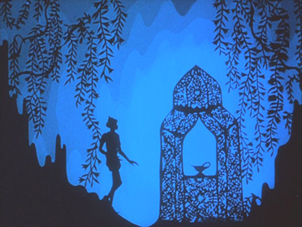

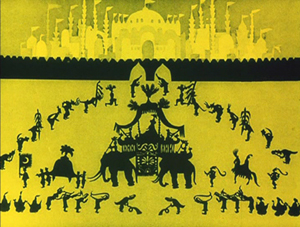

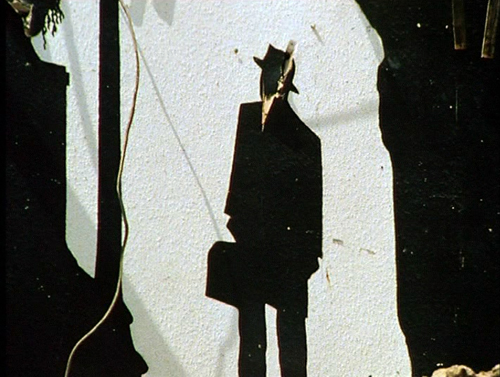

While watching Faust, I kept grabbing frames, far too many to be used in this entry. They were simply too beautiful or impressive to be passed over, and they made my final selection of illustrations difficult. The only other film for which this was true this year is Lotte Reiniger’s silhouette-animated feature, The Adventures of Prince Achmed. The restored, tinted print that is currently available is even lovelier than the older black-and-white version.

Reiniger seems to have invented the use of jointed silhouette puppets, and she still is the first artist one thinks of in relation to this form of animation. She continued to practice it until the 1970s. (See the link below to a collection of many of her short films.) Her one feature film remains her most famous and is probably her masterpiece.

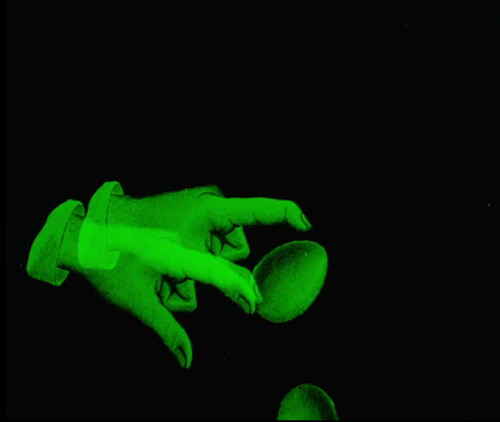

It involves far more than simple black figures moving against a light background. As the frame at the top of this entry shows, her characters, furnishings, and locations, all rendered in paper with scissors, were often elaborate indeed. Characters wore feathers, jewelry, fancy wigs, and other decorative elements. The hanging platform has many little tassels, and the lamps are rendered in delicate filigree. The backgrounds are not blank but have varying layers of saturation that suggest a depth effect, the equivalent of atmospheric perspective. At the left in the top image, a series of identical curtains start out a dusky orange and in three stages lighten until there is a bright, solid glow at the center.

In the frame at the left below, the same sort of shading creates the depth of a cavern, setting off the tracery of the foliage and the kiosk in which the hero finds the magic lamp. On the right, very simple shading suggests a vast and elaborate palace in the background, while Reiniger fills the foreground with many small figures, all marching out to surround the procession of the caliph.

By choosing a classical fantastic tale, Reiniger found the perfect subject matter to fit the technique that she invented. Both the subject matter and the sophistication of the animation give her films a timeless look. Her reputation remains high today as a result. One scene in Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Part 1, “The Tale of the Three Brothers,” was made in a style inspired by Reiniger’s work. (I discuss it here.)

A restored, tinted version of The Adventures of Princes Achmed is available from Milestone. A combination Blu-ray/DVD release of the film is available from the BFI. (I have not seen this version.) Note that these have somewhat different content. The BFI version has five Reiniger shorts from across her career along with a booklet. The Milestone version has only one of the shorts, but it includes a documentary about Reiniger. (This documentary was on the 2001 BFI release of the film on DVD but is not listed among the extras on its Blu-ray.) See also the BFI’s collection of many of her shorts, “Lotte Reiniger: The Fairy Tale Films,” which I discussed here.

[Dec 27: Thanks to Paul Taberham for pointing out that Prince Achmed also has no intertitles and gets along without them very well.]

Into the asylum

David here:

Few western viewers of 1926 saw any Japanese films, but Japanese audiences had been watching imported films for a long time. Hollywood films could easily be seen in the big cities, and The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (released in 1922), La Roue (released in early 1926), and other films from Europe had made a strong impression on local filmmakers. One fruit of this influence was the wild Page of Madness (Kurutta ichipeiji, aka “A Crazy Page”).

Directed by Kinugasa Teinosuke and based on a story by the renowned experimental writer Kawabata Yasunari, the film bore the influence of German Expressionist and particularly French Impressionist cinema. Page of Madness set out to be a bold exercise in subjective filmmaking. But it wasn’t widely seen at the time, and wasn’t revived until 1971, when Kinugasa discovered a print in his house (reportedly, among cans of rice). Apparently the version we have is slightly edited.

A woman has been confined to a madhouse, and her husband has taken a job as a janitor there to stay in touch with her. Many of the scenes are presented as the hallucinations of the wife and other inmates, while abrupt flashbacks attached to the husband fill in the past. But this story is terribly difficult to grasp. There are no intertitles (perhaps an influence of The Last Laugh, shown in Japan earlier in 1926), and the film is a blizzard of images, choppily cut or dissolving away almost subliminally.

Viewers of the period had the advantage of a synopsis printed in the program, and there was a benshi commentator accompanying the screening to explain the action. Because we lack those aids, the film seems more cryptic than it did at the time. Even when you know the story, though, Page of Madness often surpasses its foreign counterparts in its free, unsignalled jumps from mind to mind and time to time. It remains a powerful example of narrative and stylistic experiment, from its canted framings and single-frame cutting to its frenzied camera movements and abstract planes of depth (thanks to scrims à la Foolish Wives, 1922).

For nearly fifty years it has remained a milestone, a grab-bag of advanced techniques and likely the closest Japan came to a silent avant-garde film.

Page of Madness is not commercially available on home video. It is occasionally shown on TCM, and a reasonably good print is on YouTube. Aaron Gerow’s A Page of Madness: Cinema and Modernity in 1920s Japan is an indispensable guide to Kinugasa’s eccentric masterpiece.

By the Law.

Paolo Gioli, maximal minimalist

Anonymatograph (1972).

DB here:

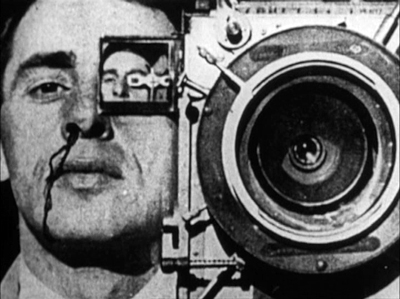

Since the late 1960s, the Italian filmmaker Paolo Gioli has been employing procedures that are almost frighteningly stripped down. He has made films without cameras. He has devised his own cameras, often without lenses or shutters or motor drives. When he needs a shutter, his fingers, or perhaps some leaves from trees, will suffice. He has embedded images within images without benefit of optical printers, and he has brought photos to frenetic life without animation stands. When he needs a camera, a modest old Bolex or Bell & Howell will do fine. Impresario of clamps and masking tape, he creates extraordinary films with equipment that looks distinctly knocked-together.

The overused term DIY doesn’t capture the eccentric craftsmanship of a filmmaker who starts from the most basic features of cinematic material: film stock, perforations, light. Everything else, even the frame, can be treated as an add-on. These films are hand-made with a vengeance.

Sparse as the equipment and approach are, the results are overwhelming. Gioli’s films can be quietly lyrical or explosively aggressive. Most are fairly compact—fifteen minutes or less—but all are dauntingly dense. Each one’s fusillade of images would be enough for a feature. Skittering and jumpy, emitting a spray of single frames, the most fast-moving ones benefit from being black-and-white and silent: nothing distracts from the swarming images’ direct hit on your eye and brain.

Last weekend, the Harvard Film Archive hosted an event honoring Gioli, his long-time producer Paolo Vampa, and my Wisconsin colleague Patrick Rumble, a tireless advocate for Gioli’s cinema. Head archivist Haden Guest, another long-time supporter of Gioli’s work, timed the gathering with the release of Gioli’s collected works in a three-DVD set from Raro. That collection is a must for anyone interested in experimental cinema. Along with the films it includes Patrick’s seminal essay, “Free Films Made Freely,” and his superb documentary on Gioli’s life and working methods.

I was lucky enough to be present too, thanks to the accident of my having written a little on Gioli way back when. I think it’s fair to say that a hell of a time was had by all—not least because seeing a rich sampling of the work on the Archive’s magnificent big screen made these films, at once rough-edged and precise, even more powerful than when they’re seen on a monitor.

Back to basics–real basics

When the Eye Quakes (1991).

There’s no easy way to sum up the great variety of these films, but I owe you a sense of what they’re like. Start with the ones based on the physical stuff of the medium.

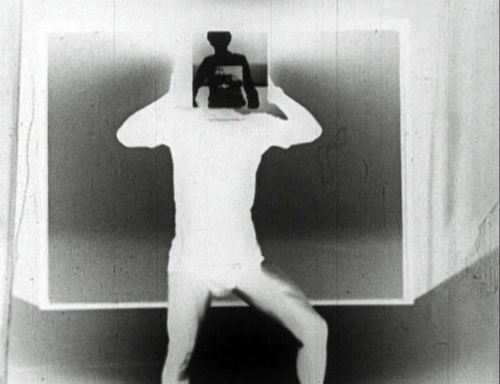

Gioli began as a painter and became both a photographer and filmmaker. He came to cinema as a result of his youthful stay in New York, where he encountered the New American Cinema. It’s not hard to see an overlap with filmmakers like George Landow (Owen Land), Ken Jacobs, and others whose films were based on displaying grain, scratches, perforations, and other physical properties of the medium. But instead of the Cagean repetition of Landow’s Film in Which There Appear Edge Lettering, Sprocket Holes, Dirt Particles, Etc. (1966), Gioli’s Commutations with Mutation (1969) bombards us with weaving, sliding, rolling strips of film (Super-8, 16, 35), all yoked violently together.

Already one sees a major motif of Gioli’s work, the frame-within-the-frame. The sprocket holes become miniature versions of the frame that can’t contain the agitation of the film stuff spilling across it.

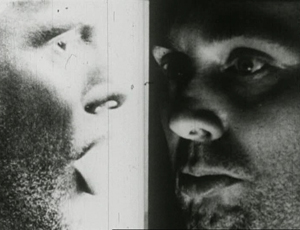

When the film gets more representational, as in According to My Glass Eye (1971), the split screen still suggests two or more films crammed into the same frame. Human faces and figures are wrenched into obsessive symmetries, mirrorings, and embeddings.

The pounding oscillation of this film, made of hundreds of different frames, is unremitting. It’s a sort of anti-Muybridge experiment: instead of decomposing action into bits, the fragments are whipped into a frenzy. The motion is insanely fast, with bodies surging in convulsions as eyes roll and pop terrifyingly. Most Gioli films are silent, but here the aggression is accentuated by driving drum rhythms.

The same primal thrust comes from When the Eye Quakes (1991), one of Gioli’s found-footage efforts. Starting from the woman’s slit eye at the beginning of Buñuel’s Andalusian Dog (1929), we get a sort of pictorial cadenza. Bunuel’s original metaphorically linked eye to moon, cloud to a razor slicing it. In Gioli’s remake, a fly crawls on the eye, the eye is peeled open to reveal a flurry of abstract patterns inside, the gash is stitched shut, and the whole array triggers REMs in another pair of eyes.

The agreeably assaultive side of Gioli’s work finds an emblem in his painting Superficie vasta della sorgente (1970). Here a rectangle serves as the screen, and two trapezoidal paintings mimic the projector beam.

The whole ensemble suggests not only a projector sending images to a support but a torrent of images pumped out to punch the viewer.

A more leisurely found-footage film is The Perforated Cameraman (1979), which stops and restarts shots from a silent comedy. Those images are haunted by yet another variant of the frame: wide-angle rectangles drifting in and out.

One such shape turns out to be a ghostly version of the center perforation of the 9.5mm format. That’s the format of the source movie itself, which is, in another reflexive twist, about the making of a movie.

Optics, mechanics

Paolo Gioli demonstrates one of his pinhole cameras as Paolo Vampa looks on.

Gioli has said that he wants to free himself from cinema’s reliance on “optics and mechanics.” Accordingly, he has reverse-engineered, or rather de-engineered, the apparatus of image-making. Take his various experiments with pinhole imagery. He has pushed the idea of the pinhole photograph (of which he has made many) to another level with pinhole movies.

He started with buttons, using their holes as light-gathering apertures. But since a shirt’s buttons are arranged top to bottom, why not do the same with pinholes? Accordingly, he devised a tube punctured at regular intervals, like a flute. The tube has a chamber for a film strip, with one pinhole per frame. The “shutter” is a hinged strip of metal that opens and shuts to expose the film.

To make the shot the “camera” is held upright. What’s hard to get your mind around is that the frames aren’t exposed sequentially, but all at once. They present varying angles on the subject at one instant.

When developed and run through a projector, however, they gain a temporal dimension. The footage presents an object that seems to slide vertically into view, framed by serrated edges and illuminated by irregular flares of light. Because the first images we see in a shot are those at the bottom of the tube, we may get the effect of a rising camera movement, when in fact there was none. A bowl of fruit in the foreground sinks out of sight as we seem to withdraw from a window.

Each tubular camera yields “takes” of more or less constant length; one tube is two meters long, another is only about 50 frames. Assembled (usually in camera rather than in postproduction), the shots arrive in a regular rhythm. Sometimes the footage displays another in-camera montage: Gioli has cut the hinged strip into two parts, so that he’s able to expose the top part of the film in taking one “shot,” then, separately, another strip of frames at the bottom. And sometimes the upper edge of the motif is cropped and it creeps in from the bottom.

The rigid verticality of Film Stenopeico (aka The Man without a Movie Camera, 1973/1981/1989) and Natura Obscura (2013) seems to me another version of the way in which Commutations with Mutation created one long image on the film strip and then chopped it into bits in projection. What has no framelines acquires them during the screening.

In an essay posted on this site, I noted that these efforts toward a “vertical” cinema recalled Eisenstein’s call to repudiate the horizontality of the classic 4:3 frame. It’s also worth remarking that once you know how the pinhole films are made, you’re obliged to think of each film as having two modes of existence: the physical object threaded through the perforated cylinder, and the film as we see it, an upward scan of an object in our surroundings.

Seeing red

Patrick Rumble and Paolo Gioli explain the experiment Land’s Red (2014).

This “double film,” the duality of the physical and the perceptual in our experience of the movies, is there at the start of his career. On the screen, Traces of Traces (1969) vibrates with abstract patterns of contours, edges, and whorls; it takes on a different sense when you learn that Gioli made it by pressing fingers, sandpaper, rubber stamps, and body surfaces against the film stock. As ever with avant-garde cinema, the question What am I seeing? often comes down to How were these images made?

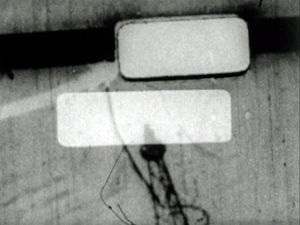

Gioli’s “new optics” makes him interested in perceptual phenomena like visual saccades (exaggerated to a terrifying degree by his frenetic fast motion) and color vision. Fascinated by the oddities of our visual system, he has “operationalized” Edwin Land’s early experiments in color perception. In an important 1959 article, Land considered the sources of color constancy—the fact that an orange looks about as orange in bright sunlight as it does in deep shade. Yet the lighting conditions are drastically different and should yield a different color sensation. Somehow our visual system “knows” to adjust for fluctuating illumination and yields a stable color world.

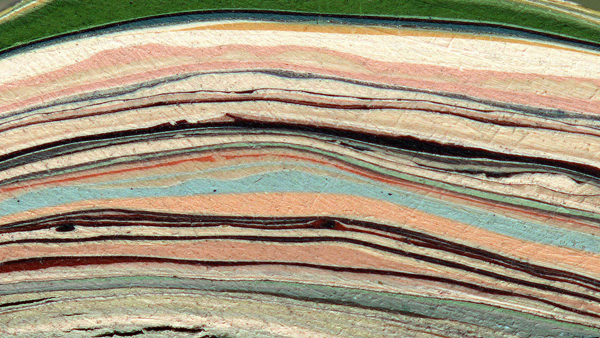

Land’s experiment filmed black-and-white still photographs through color filters, then displayed them as slides and tinted the projection beams. He discovered that under certain conditions, we can recover a wide range of colors from a combination of pure white light and a red filter. It’s as if our visual system, which is sensitive to three overlapping wavelengths of light, was endowed by evolution with a bit of redundancy. Moreover, color constancy suggests that perception of color is independent of degrees of illumination.

Gioli replicated Land’s experiment with motion pictures by creating black-and-white film loops (Land’s Red, 2014). During his Harvard Film Archive stay, he demonstrated the result, including a close-up shot of a woman with blue eyes and bluish-silver eye shadow. The left image is the double-projection without a filter, the right is the image with a red filter. We’d expect that putting the filter on tints the entire image red. Instead, the filter generates a range of color, from the vibrant lips to the pale blue of the eyes and eye shadow.

Land’s theory involves psychophysical matters I can’t claim to understand. I gather that his account of three wavelengths in our cones’ pigments is now seen as a partial explanation of color vision. His “retinex” theory—the idea that the retina isn’t the only source of color, that there must be coding of the wavelengths in the cerebral cortex too—pointed other researchers toward a computational account of perception. The eye is a part of the mind.

Gioli’s startling demonstration reminds us that experimental science and “experimental” cinema aren’t always so far apart. A lot of avant-garde films, such as those of Ken Jacobs (discussed a bit herabouts) constitute rich, poetic probes into the quirks of our vision.

A past remade

Gioli has quickened photographs through pixillation, creating movement out of stills with an almost childish simplicity. He just snaps frames from illustrated books. Filmarilyn (1992) uses images from a Bert Stern collection to evoke Marilyn Monroe’s flirtation with death. Perhaps Gioli’s most accessible film, Children (2008) is a succinct, somewhat mordant reflection that carries us from Avedon shots of John and Jackie Kennedy, romping with Caroline and John, Jr., to images from Jacob Riis’ investigation of poverty in New York, and then to the imagery of the My Lai massacre.

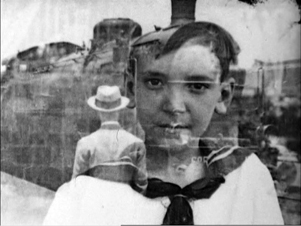

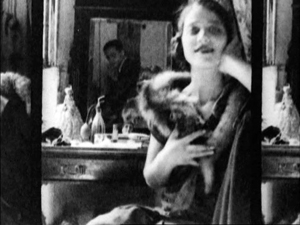

Gioli has also done a kind of archeology of early film, as in his homage to chronophotography Little Decomposed Film (1986). My own favorite of his works is the lyrical and melancholy Anonymatograph (1972). In some ways it’s parallel to the work of “Structural” filmmakers like Malcolm Le Grice (e.g., Little Dog for Roger, 1966). The principal source is 35mm material of 1910-1930s from an unknown cameraman. The anonymous photographer recorded families and street scenes, both posed figures and spontaneous laughs and yawns. The footage was shot on an unusual Zeiss camera that could take both still images and motion pictures (a machine ideally made for Gioli).

Gioli’s reworking is typically high-strung, with nearly single-frame imagery at various points. Yet it doesn’t seem jittery. Despite the pace, the film proceeds majestically. It’s at once celebratory, showing gorgeous people, grave or gay, turning to or from the camera, and mournful, as the progression of shots takes us toward war and fascism. There are glimpses of “folk porn,” and hallucinatory superimpositions recalling juxtapositions out of Magritte or Paul Delvaux.

Gioli endows these long-dead divas and sturdy gentlemen with graceful, almost tragic unawareness of their place in history. Anonymatograph goes beyond his pure experiments with light, shape, and the skin of the film. It’s a testimony to the subtle power of old pictures and to an artist’s ability to reimagine, without abandoning any of his nervous intensity, the world they captured. No wonder Patrick Rumble calls Gioli “the last of the first filmmakers.”

I haven’t dealt with the full range of Gioli’s work. I’ve neglected the paintings and photographs, and I’ve had to neglect his powerful “photofinish” films (e.g., Slit-scan Figures, 2009). I just hope I’ve intrigued you enough to induce you to explore this unique and unpredictable filmmaker.

Thanks to Haden Guest for inviting me to participate in the HFA event, to Jeremy Rossen for help during my visit, to Patrick Rumble for many discussions of the films, to John Powers of Madison for information about optical printing, and of course to Paolo Vampa and Paolo Gioli for sharing ideas and information.

The Gioli collection is distributed in the US by the far-sighted company Kino Lorber. There’s also a book of essays, Paolo Gioli: The Man without a Movie Camera, ed. Alessandro Bordina and Antonio Somaini (Mimesis, 2014). The official Paolo Gioli website is here.

The Edwin Land articles are “Experiments in Color Vision,” Scientific American (May 1959), 84-99. and “The Retinex Theory of Color Vision,” Scientific American (December 1977), 108-128. A good biography of this remarkable man is Victor K. McElheny, Insisting on the Impossible: The Life of Edwin Land (New York: Basic, 1999).

The first Sherlock and other video releases for the holidays

Our Lady of the Sphere (Lawrence Jordan, 1969)

Kristin here–

Our friends at Flicker Alley have offered three major releases since early October: Masterworks of American Avant-garde Experimental Film 1920-1970 (October 6), Sherlock Holmes (November 10), and Chaplin’s Essanay Films 1915 (November 17). This may seem ridiculously fast-paced, but it is partly explained by a delay in the release of Sherlock Holmes. All three editions package Blu-ray and DVD versions together.

In the move from 16mm to digital, avant-garde cinema was initially left behind. Eventually big boxes and series of DVD releases made a huge number of experimental short films available to audiences who may  have had little access to such fare before. In quick succession, Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1894-1941 (2005), Kino’s three-volume series Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema 1920s and ’30s (2005), Experimental Cinema 1928-1954 (2007), and Experimental Cinema 1922-1954 (2009), and the forth volume of the “American Treasures” series, Avant-Garde Film 1947-1986 (2009) were released.

have had little access to such fare before. In quick succession, Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1894-1941 (2005), Kino’s three-volume series Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema 1920s and ’30s (2005), Experimental Cinema 1928-1954 (2007), and Experimental Cinema 1922-1954 (2009), and the forth volume of the “American Treasures” series, Avant-Garde Film 1947-1986 (2009) were released.

Now we have another ambitious set, Masterworks of American Avant-Garde Experimental Film 1920-1907. Fans of experimental cinema who have purchased all of the earlier sets might wonder if there is room for yet another extensive collection of American films. Won’t there be a lot of overlap? The answer is a definite no. The body of work by important avant-garde filmmakers is extensive enough to support many boxed-sets.

I can find not a single film in the seven DVDs in Unseen Cinema (which takes a rather broad view of what counts as avant-garde) that is duplicated here. The same is true of the Avant-Garde Film 1947-1986 set. The Kino boxed sets (two discs each) are heavily slanted toward international films, and there is a slight overlap. Flicker Alley’s website has a list of all 37 titles included in Masterworks.

It’s impossible to deal with all the films included in the set here. (The film illustrated at the top is one of them.) I’ll just say that I was happy to see Hilary Harris’ 9 Variations on a Dance Theme (1966/67, right). We used to show it in the introductory film course we taught back in the mid-1970s, when Film Art had not yet been dreamt of. It’s a lovely film in itself, but it also might possibly be the clearest way to get across the ideas of form and style that one could find. Starting with a long shot of the dancer in a segment that simply records her movements, documentary style, the film repeats the same music and choreography eight times, with the cinematography and editing rendering a progressively abstract set of images.

Flicker Alley has put together an essential collection of films that will be new and exciting to many fans. The extras include, generously, three other experimental films. A a helpful booklet contains an introduction by Bruce Posner and brief program notes and filmmaker bios.

The Return of Sherlock Holmes

Until recently the 1916 version of Sherlock Holmes, based on the play by William Gillette, was lost. That seemed exceptionally unfortunate, not only for legions of Holmes fans but for anyone interested in late Victorian stage practices. Gillette’s performance as Holmes was considered the defining one, influencing subsequent portrayals. The play, which was produced in the US in 1899, had the cooperation of Arthur Conan Doyle, whom Gillette consulted during the period when he was writing it. The film version was a precious record from the time when the Holmes series was still being written.

In fact, Conan Doyle had killed Holmes off in 1893 in “The Final Problem,” and at the time when he authorized the play, he still had not resurrected his popular character. Gillette’s play influenced the later stories with such additions the character of the young servant Billy, a character invented by Gillette and later used by Conan Doyle.

In one of those happy endings that occasionally happen with lost films, a copy was discovered in the Cinémathèque française. Not just any old copy but the original nitrate negative of the French release version, which was shown as a serial in four parts in 1919. Apparently no footage was lost, and the main difference between the restored version that we have now and the original American feature film is that the new intertitles have been translated from those of the French release.

The original play has four acts, and the film has compromised between maintaining the interior setting of each act for a long stretch of the film and opening it out with brief exterior scenes and cutaways to other locales. One very lengthy section of the film takes place in the isolated house used by the villains to imprison the heroine, Alice. The sets are somewhat reminiscent of the stage, and yet they have been extended forward, and at times we see at least three walls and perhaps part of a fourth. In many cases, the stage-style set is made more cinematic through the simple device of adding some furniture in the foreground (left). In others, the characters are strung out in a line across the playing space, as in the final “act,” which takes place in Dr. Watson’s office (right).

Physically, Gillette makes a convincing Holmes in terms of the way Conan Doyle describes him, and his performance is restrained and usually lacking in expressivity–which works for a character noted for not exhibiting emotion. Unfortunately Gillette added a love interest for Holmes. Doyle, who apparently didn’t care what others did with Holmes now that he was rid of him, gave his permission. This would be bad enough in itself, but Alice is quite young looking, and Holmes is much older than she. Gillette had originated the role seventeen years earlier, when he was 46. By the time the film was made, he was 63, and though he doesn’t look that old in the film, the age difference between Holmes and Alice is obvious.

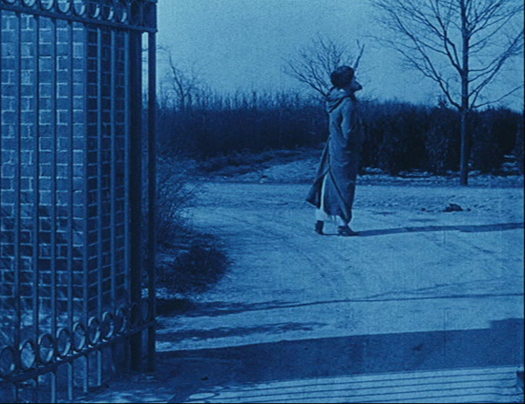

Given the survival of the negative, the Blu-ray/DVD transfer is impressive. Serpia toning is used in most scenes, while dark blue tinting represents night exteriors, many of which are nicely filmed (see bottom). The music is by Neil Brand, one of the best accompanists in the business.

There are generous bonuses, including some earlier comic shorts based around the character, Conan Doyle’s Fox Movietone interview, and a typescript of Gillette’s play. The set comes with a booklet with short essays on Gillette and his play, the film adaptation, the restoration, and the music.

The Little Tramp takes shape

Jeffrey Vance begins his essay on Chaplin in the booklet accompanying Chaplin’s Essanay Comedies 1915 with this observation:

If the early slapstick comedy of the Keystone Film Company represents Charles Chaplin’s cinematic infancy, the films he made for the Essanay Film Manufacturing Company are his adolescence. The Essanays find Chaplin in transition, taking greater time and care with each film, experimenting with new ideas, and adding textue to the Little Tramp character that would become his legacy. Chaplin’s Essanay Comedies would become his legacy. Chaplin’s Essanay comedies reveal an artist experimenting with his palette and finding his craft.

The unstated conclusion to the series of companies where Chaplin worked during the 1910s is that the Mutual period saw Chaplin’s maturity as an artist. Flicker Alley has now completed its epic survey of all three periods, with copies restored by the Cineteca Bologna and Lobster Films in cooperation with Blackhawk Films and the Chaplin Mutual and Essanay Project. Many archives provided material. For those who first saw Chaplin in worn 8mm and 16mm copies, these prints are a revelation.

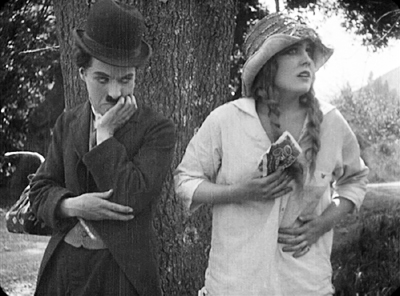

Chaplin’s tinkering with his Tramp character is evident in the most famous short in the set, The Tramp. It begins and ends with the character on the road, going nowhere in particular. In between are sandwiched broad slapstick scenes, quieter comic moments, and a big of the pathos that would become increasingly central to the Tramp.

Early in the film he is capable of saving an innocent farm girl with a wad of money from a trio of thieving hobos, then stealing the money himself (above), and then relenting and giving it back. His comic pacing is sometimes off–way off in an overlong scene of the Tramp, who gets a job at the heroine’s farm, repeatedly poking a fellow farmhand with a pitchfork (a pretty cliched gag to begin with). The Tramp’s clueless attempts at milking a cow work distinctly better, as he tries everything, including turning the cow’s tail into a pump handle. That’s the sort of visual punning that would become one of Chaplin’s comic strengths. There are some funnier scenes, as when the Tramp is forced to bunk in with the farmhand and suffers agonies from his roommate’s smelly socks.

Some quietly funny moments are better, though, as when the Tramp, having been wounded in the leg while trying to foil a burglary attempt, sits complacently enjoying his leisure and assuming that the heroine is in love with him. The absent boyfriend, well-dressed and handsome, soon shows up and, recognizing the inevitable, the Tramp removes himself from the triangle and takes to the road once more. Perhaps more than any other image, this one summarizes how Chaplin’s Tramp was thought of for many years and by millions of people.

Bonuses include some films using discarded footage or cutting together scenes from already-released shorts, as Essanay tried to capitalize as much as possible on Chaplin’s extraordinary international popularity. There is also a booklet with Vance’s essay and a set of program notes. Each of these has a brief description of the restoration process, which is a nice thing to see in a supplement.

Sherlock Holmes (1916)

An evening with Mr. Smith

Dad’s Stick (John Smith, 2012).

DB here, from London:

Last week we held another annual meeting of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image. I think it’s safe to say that a hell of a time was had by all. I hope to file a report on some of what was said in nearly 100 presentations across 3 ½ days. For now I want just to note a conference highlight that deserves special notice.

English filmmaker John Smith has been working since the mid-1970s, originally in 16mm and now in HD video. On Thursday 18 June, several lucky participants got a very substantial sampling of his career’s achievement in an evening retrospective.

English filmmaker John Smith has been working since the mid-1970s, originally in 16mm and now in HD video. On Thursday 18 June, several lucky participants got a very substantial sampling of his career’s achievement in an evening retrospective.

In their visual wit and their emphasis on perceptual shifts, Smith’s films owe something to the international Structural Film trend, but they stand out by their wit and their almost classical beauty. I saw affinities with Hollis Frampton, especially in Associations (1975), in which a test of word-associations slips hilariously out of control. But Smith seems to lack Frampton’s interest in poeticizing scientific and philosophical concepts. The work sampled in our session was characterized by sensuous appeals: precise framing, saturated color, image-sound counterpoint, and richly detailed landscapes. The conceptual element entered as teasing jokes or half-formed narratives.

I had seen three or four before. Hackney Marshes–November 4, 1977 wasn’t in the program, but Kristin and I referred to it in Film History: An Introduction, because of its brash editing patterns. More famous, I suppose, and screened on Thursday, was The Black Tower (1985-87, below), with its oppressive rectangle looming over a striking variety of locales. The film keeps cutting among widely different vistas and neighborhoods, each with the tower visible in middle distance. The associations pile up: state surveillance, a prehistoric monolith, a dark temple, or an alien spacecraft. It was a pleasure to see again.

Altogether different is another of Smith’s most famous works, The Girl Chewing Gum (1976). A busy street is rendered strange by the soundtrack, in which a commentary seems to be directing the whole ensemble of passersby and traffic. Quite soon the voice-over turns into something quite odd. I find a whiff of Monty Python in this charming lesson in image/sound interference. (You can watch it on Vimeo here.)

One of the most striking selections was Blight (1994-96). The demolition of a nearby building becomes, through Smith’s maniacally locked-down camera, a study in abstract composition and eerie movement. My stills can’t suggest the way in which apparently fixed timbers and bricks suddenly shift or fall, moved by no visible hand. The music by Jocelyn Pook further “defamiliarizes” imagery of collapsing walls and exposed wiring. And the tattered man above seems to be watching the whole proceedings.

The program concluded with recent work. Flag Mountain (2010, above) elicited much comment. Fixed stop-motion telephoto shots of a mountain in Nicosia become almost hallucinatory in vibrant HD video and rapid day/night alternations. Dad’s Stick (2012, above) is a lovely tribute to Smith’s father, but it’s also a witty game of form. What seems at first to be a voluptuous abstract painting turns out to be something more mundane, but now mysterious in its accidental beauty. As a bonus, you get a good-natured teasing of art critics’ jargon. Part of Dad’s Stick is here.)

John proved a delightful and modest commenter on his work. He points out that the fixity of each image allows him to treat them as discrete items, like letters of an alphabet, so that the cutting has a crisp force. He’s come to like HD video, but yearns to “get out the old Bolex and shoot one last film.” He declines all the standard labels—avant-gardist, experimental filmmaker, maker of “artist’s films.” He thinks that his films can be appreciated by anybody who’s open-minded, and I think we all agreed. Quiet yet powerful, John Smith’s work seems to me to attest to the continuing relevance of artisanal filmmaking.

You can visit John’s website here. A large selection of his work is available on the three-DVD set John Smith, available from Lux here. The discs aren’t region-coded. Every university should have this set, as well as the Cinema 16 collection, British Short Films, which includes work by John and his contemporaries.

Thanks to Tim Smith, Murray Smith, and John Smith (no relation, none at all) for arranging this wonderful evening.

The Black Tower (John Smith, 1985-1987).