Archive for the 'Experimental film' Category

GRAVITY, Part 1: Two characters adrift in an experimental film

There was no way to rely on anything we knew before this film. No character was like Stone, no film set was ever like these sets, not one member of this crew had ever done this before. We all were doing something that had never been done before.

Kristin here:

Back in mid-September, on the verge of leaving Madison to attend the Vancouver International Film Festival, I mentioned that I had watched one of the trailers for Gravity and thought it looked like “the most exciting new piece of filmmaking this year.” I added that the trailer “called ‘Drifting’ reminded me of Michael Snow’s brilliant Central Region, but with narrative, with the earth and stars spinning past a close-up of Sandra Bullock as the marooned, panicky astronaut protagonist.”

At that point, I wondered whether the film as a whole could keep up that experimental feeling, with vertiginously wheeling actors combined with an untethered camera swooping around them. Or would the narrative gradually lead us into a more conventional style later in the film? It turns out that, to a remarkable extent, the highly unconventional treatment of unanchored space, where up, down, and sideways characters and background change with a breathless rapidity, extends through much of Gravity‘s length. For brief intervals Ryan enters space capsules and sits, right-side up, and the action calms down briefly. Yet these lead to further scenes in space with the same swooping camera. In short, the film turned out to be as remarkable a formal and stylistic achievement as I had hoped.

SPOILER ALERT. This is not a review but an analysis of the film. Gravity does depend crucially upon suspense and surprise, and I would suggest not reading further without having seen the film.

An experimental blockbuster

I am not the only one who was struck by Gravity‘s resemblance to an experimental film. After the film’s opening weekend in the USA, Variety‘s Scott Foundas published an article on the subject: “Why ‘Gravity’ Could Be the World’s Biggest Avant-Garde Movie.” He references the influence of Jordan Belson’s work on 2001: A Space Odyssey and speculates that the final shot of The Shining echoes the ending of Michael Snow’s Wavelength. More specifically he links Gravity to Central Region, shot in 1971 at in a Canadian mountain range; Foundas describes the robotic arm used to shoot the film and how it was controlled by instructions on magnetic tape. (I’ll have an illustration of the robotic arm in Part 2.) To Foundas, the avant-garde aspects of Gravity outweigh its narrative: “‘Gravity’ has more of a plot than ‘La Region Centrale,’ but only barely, and surely no one is telling their friends to see Cuaron’s film because of its great story. Rather, it’s the very absence of a dense narrative line that gives ‘Gravity’ its majesty.”

I think that to say Gravity has “only barely” more narrative than Snow’s purely abstract film is a considerable exaggeration. The film’s story is certainly simpler and more unconventional than other mainstream Hollywood films, but as we shall see, it contains goals, motifs, character traits, careful setups of upcoming action, and other traits of classical narratives.

In an October 11 blog entry, J. Hoberman also stresses the film’s modernism:

Depth and volume are illusory. Mass has no weight. In this 3-D spectacle, best seen on the outsized IMAX screen, Cuarón promotes sensory disorientation–or better, reorientation. […] Gravity is something quite rare–a truly popular big-budget Hollywood movie with a rich aesthetic pay-off. Genuinely experimental, blatantly predicated on the formal possibilities of film, Gravity is a movie in a tradition that includes D. W. Griffith’s Intolerance, Abel Gance’s Napoleon, Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia, and Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds, as well as its most obvious precursor, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001. Call it blockbuster modernism.

(Actually I’d say Gravity is better than some of these, notably Napoléon and 2001.)

Hoberman sees more of a balance between style and narrative than does Foundas. In fact, he considers that the film contains “a distracting surplus of backstory.” Presumably he would prefer to do without the references to the death of Stone’s daughter and her subsequent aimless car rides after work, listening to the radio. The space voyage does become an overly obvious extension of that drifting and listening, coming close to turning the film into a maternal melodrama. Presumably the filmmakers felt that simply sending Stone on a mission and having her struggle to return to earth was not enough. In interviews, the co-scriptwriters, Alfonso and his son Jonás Cuarón, emphasized that their basic idea was to create a character arc of her “rebirth” after despair. To some, this arc, with its religious overtones, will seem a bit, as Hoberman says, distracting and even contrived. To others it may be inspiring. At least it is not allowed to come forward very often.

Hoberman stresses the balance of plot and radical style. The film, “premised on the absence of up or down, is naturally abstract although it also has a streamlined and suspenseful narrative that, save for one or two ellipses, might almost be happening in real time.” In Variety, Justin Chang’s review highlights the same balance: “at once a nervy experiment in blockbuster minimalism and a film of robust movie-movie thrills, restoring a sense of wonder, terror and possibility to the bigscreen that should inspire awe among critics and audiences worldwide.”

David and I have often claimed that Hollywood cinema has a certain tolerance for novelty, innovation, and even experiment, but that such departures from convention are usually accompanied by a strong classical story to motivate the strangeness for popular audiences. (This assumption is central to our e-book on Christopher Nolan.) Gravity has such a story, though Cuarón is remarkably successful at minimizing its prominence. The film’s construction privileges excitement, suspense, rapid action, and the universally remarked-upon sense of immersion alongside the character in a situation of disorienting weightlessness and constant change.

That construction derives partly from techniques unique to this project. The weightless dance of characters and camera almost entirely does away with such widely applied spatial premises as the axis of action, eyeline directions, and the establishing of stable spatial relationships. And, as Cuarón pointed out in an interview for Wired, “After all, you learn how to draw based on two main elements: horizons and weight.” Those two factors are virtually gone as well.

The weightlessness and the long takes in the film have been given much attention in the press. Reports refer less often to the “Light Box, one of the film’s most extraordinary innovations. It is a giant inside-out LED monitor that allows the film’s own previs special effects to light the faces and bodies of the actors inside the box, making it possible for those shots to be integrated seamless into the effects shots. Basically, apart from the scenes inside space vehicles, traditional three-point lighting is jettisoned along with spatial relations.

Other technical aspects of the film are innovative. A bold new camera mount, the Isis, was devised to allow the camera to twist and whirl around the actors. The silence of space was respected by the filmmaker, leading them to substitute a eerie musical score to replace sound effects and convey emotions. The blocking and acting, of course, had to be vastly different from methods used in conventional films where the actors have the luxury of walking on a ground plane.

In short, it is hard to think of another mass-audience film in recent years that has so thoroughly departed from the current technological and stylistic conventions of mainstream filmmaking. Jurassic Park and The Lord of the Rings, to be sure; perhaps Avatar. Publications devoted to the techniques of cinema have recognized this. The Cinefex issue dealing with Gravity is not yet out, but on the journal’s blog, Don Shay’s remark is quoted: “Every once in a while, a film comes along that is a game-changer. This is one of those films.” Debra Kaufman, writing about the film’s 3D for Creative Cow, agrees: “Anyone who’s seen Gravity 3D will agree that the 3D was a game changer.” And unlike those earlier game-changers, Gravity has a strong experimental component to it that audiences gladly accept, since it is so well motivated by the story and situation.

In the next blog entry, I’ll survey the innovative aspects of Gravity‘s style and technique. Today, though, I’ll concentrate on the plot–in some ways conventional and in some ways quite strange–that holds it all together.

Who needs psychological depth in a crisis?

Arguably Cuarón had constructed nearly the most sparse narrative that can sustain the experimental style and motivate that style enough to hold the attention of a popular audience. Three characters, then two, then one, all with minimal backstories and simple goals.

Most Hollywood films have two parallel plotlines, usually one involving a romance. Here there is only one, and it primarily concerns an immediate situation, a cycle of deadly threats alternating with stages of Ryan’s progress toward safety. On balance, the focus is more on the suspense and terror of the situation than on the characters. Although there is a little mild flirtation between Stone and Kowalski, it’s more to generate humor and defuse the tension than to suggest any real possibility of mutual attraction.

One indication of the film’s minimal characterization is that fact that we never learn the nature of Stone’s experiment. That would be a logical initial goal for her character. Why has she set herself this particular task, which obviously involved not only scientific expertise in a complex field but also elaborate training to become an astronaut? Where does she work? What might her test achieve? Some reviews have referred to her as a medical expert. As far as I can tell, this is based on one line when she and Kowalski are working together to activate the communications device that is her focus of attention in the opening scene. During the calm before the debris collision, she remarks, “I’m used to a basement lab in a hospital where trays fall to the floor.” She also says that “It’s designed for hospital use.” That’s it. Normally a Hollywood film would redundantly give us information about her job. Here we don’t even get a sketch of it. And why is a medical experiment attached to the Hubble Space Telescope?

Incidentally, the Hubble is detached from the shuttle just before the debris cluster reaches it. We never learn whether it, too, is destroyed in the disaster. Might it have survived, with Stone’s experiment, perhaps activated during her brief delay before obeying the mission-abort command? Might she return to earth to find her experiment a success, with her initial goal miraculously achieved despite the tragic events in space. So little is the narrative concerned with the experiment as a significant goal that such questions are unlikely to occur to a spectator. They came to me only after three viewings.

Stone’s casual reference to working in a hospital lab typifies the limited sort of backstory we’ll get for the most part. Aside from Stone’s recollections of her daughter’s death and her aimless evenings of driving as her form of mourning, the moments of backstory are mere hints. In the opening we learn that Matt’s wife left him when he was in space on a mission. Might he be so obsessed with the beauties of space travel because he, too, is seeking to escape loneliness? We can’t know, since he treats the mention humorously, as if he has managed to shrug off his wife’s betrayal. Of the third character present on the spacewalk, Shariff, we learn that he has a wife and son, something revealed by a photo only after his death. This knowledge serves less to characterize him than to contrast this cheerful fellow with the wifeless Kowalski and childless, unattached Stone.

Stone’s mention of her home in Lake Zurich, Illinois and of her daughter’s death is the last piece of backstory that we get, and it comes slightly under half an hour into the film, during the calm interlude when she and Kowalski are slowly traveling toward the International Space Station (ISS). After this, I believe the only scrap of information from her past that we get is that Stone’s daughter had worried about a lost red shoe.

This lack of information about the characters is probably what led Foundas to say that the film has “barely” more of a plot than Central Region. In the same piece, he speculates, did the executives at Warner Bros. “wonder if they’d just gambled away $100 million on the most expensive avant-garde art movie ever made?”

Kevin Jagernauth reports on indiewire that the studio pushed for a more conventionally constructed film. Cuarón told him about some of the feedback he got from WB:

But at first, the studio suggested that [the Mission Control] team in Houston should get more face time. “…there area lot of ideas. People start suggesting other stuff. ‘You need to cut to House and see how the rescue mission goes.'”

And that’s not all. Part of the emotional journey of “Gravity” rests on Stone’s backstory, which includes a daughter she lost, but this is all effectively communicated without breaking the single location concept. However, Cuarón was advised to perhaps include some flashbacks in the film and even more. “A whole thing with … a romantic relationship with the Mission Control Commander, who is in love with her. All that kind of stuff. What else? To finish with a whole rescue helicopter, that would come and rescue her. Stuff like that,” he explained of some of the ideas that were floated his way.

There’s that conventional second romantic plotline, which in the wake of the film’s success seems such a ludicrous suggestion. The studio’s attitude demonstrates how very much Cuarón was able to get away with and how much of a struggle it must have been. Audience and critical enthusiasm suggests that he and his team managed to include just enough classical storytelling to make spectators identify with the characters even while knowing very little about them.

Why would a film need to establish psychological depth for characters when most of what they’re going to be doing is struggling frantically for their lives, cast adrift in space and bombarded by hurtling space debris? They must summon what skills and psychological strength they have and get on with it. Thoughtful conversations and subtle complexities are irrelevant for the most part. We need to care about these people to be engaged by the film, but that is part of the point of having Sandra Bullock and George Clooney as the leads, playing to the likeable personal qualities that we already associate with these stars.

Challenges and goals

There’s no question that the characters do have goals, but these are largely based on circumstances thrust upon them rather than on character traits. Before disaster strikes, the characters have short-term goals: Stone to solve the glitch with her equipment (and to avoid allowing nausea to cut short her attempt) and Kowalski to enjoy his final space walk and ideally break the record for duration of space walks. Both goals are cut short by the news of approaching debris and the mission-abort order. As we’ve seen, whether Stone achieves her original goal concerning her experiment is never revealed, nor are we encouraged to wonder even briefly as to whether the Hubble might carry it away from the destruction of the shuttle. Kowalski achieves his goal of breaking the record, in a sense, as he comments ironically while detached and drifting in space and awaiting his death. His space walk will last forever, but records are hardly intended to include corpses.

Once Stone spins off into space, alone, her goal is to re-establish contact with Mission Control and Kowalski. His is to rescue her. Once he finds her and tethers them together, their mutual goal is to get to the shuttle, with Kowalski adding the goal of retrieving Shariff’s body. Very quickly these goals are shattered, since the shuttle has been extensively damaged and its other crew members killed. A new short-term goal arises: reaching the relatively nearby ISS.

Kowalski fails to achieve this goal, since the fuel in his jetpack and his inability to grab anything on the ISS’s exterior send him floating off into space. Stone’s goal is now to get inside before she passes out from lack of oxygen. Once inside, her goal is to detach the remaining semi-functional Suyuz landing vehicle and use it to get as far as the Chinese space station, in turn using its landing pod to return to earth.

Discovering that the deployed parachute has become tangled in the ISS, she takes another space walk to detach it from the Soyuz. Another short-term goal that is soon accomplished. As she starts to remove the bolts anchoring the parachute, she states the short-term and long-term goals: “OK, we detach this, and we go home.”

Her purpose, however, seems to be thwarted when the fuel tank of the Soyuz vehicle proves to be empty. Here Stone loses hope, drifting into despair. She decides to turn off the oxygen supply and allow herself to die. Suddenly Kowalski appears and enters the pod, giving her a pep talk and telling her to use the soft-landing function of the Soyuz rather than its take-off capabilities. He disappears, and Stone, reinvigorated and determined, follows the instructions for landing the craft.

In traditional classical films, shifting goals often mark the turning point between large-scale sections of the plot, generally referred to as acts. Despite its unconventional aspects, Gravity’s plot does stick fairly closely to the well-balanced four-part structure that I have claimed is typical of Hollywood narrative conventions. Not counting titles or credits, the story runs approximately 83 minutes. Thus on average the acts would run about twenty-one minutes each.

At about 22 minutes in, Stone and Kowalski achieve their goal by reaching the shuttle, only to discover that it has been destroyed. At 23 minutes, Kowalski declares them the last survivors of the mission. I take this to be the first turning point, ending the setup and beginning the complicating action. Essential premises are reversed as the pair realize that they are stranded in space and they shift their goal, striving next to reach the ISS. Stone’s failed attempt to contact Kowalski by radio once she enters the ISS–she initially hopes to rescue him–and declaration of herself as the mission’s sole survivor happens at roughly 43 minutes. The third act, the development, begins, with Stone meeting numerous obstacles that threaten her new goal of getting back to earth in the Chinese landing vehicle. The last turning point, launching the climax, comes when Stone awakens from her dream about Kowalski and turns the oxygen flow back on, signaling her return to hope and determination to reach earth. That happens at about 66 minutes in, leaving seventeen minutes for her landing, including the brief epilogue of her floating, swimming ashore, and shakily standing up.

Motifs and causal motivation

As I mentioned, strongly innovative films in the Hollywood tradition need the support of classical conventions to keep the narrative clear and appealing. Two of Gravity‘s most traditional techniques are its motifs and its motivations. Motifs can quickly make the characters more vivid, even if they are not particularly rounded or complex. Motivations often involve planting an object or event in advance. In this film, several motifs trace the relationship between Stone and Kowalski.

In the opening, the motif of Kowalski’s wanting to break the space-walking record is introduced early on, stressing that this is his last mission and hinting that he loves his time in space. Similarly, his anecdotes, introduced with the “I’ve got a bad feeling about this mission” running gag, create irony but also suggest how Kowalski inspires Stone. Before setting out on her re-entry flight in the Chinese landing pod, she repeats this line with the same good humor that Kowalski had displayed. Another parallel is set up between the two when Stone detaches the clasp tethering her to the wildly spinning support in the opening scene, and later Kowalski does the same to separate himself from Stone when they are precariously suspended from the ISS (below). She comes back; he doesn’t.

In the early scene where the pair work to activate Stone’s equipment, he refers to her “beautiful blue eyes,” though she points out that hers are brown. Later, when Kowalski has set himself adrift in space, their radio conversation mentions his “beautiful blue eyes,” which are also brown. Though we see nothing of their earlier relationship, such motifs lend it depth, because we sense that the two have already developed a customary way of bantering with each other.

Similarly, in the opening scene, Kowalski tells an anecdote about how, during a previous mission, he had imagined his wife looking up into space and thinking about him, when in fact she had run off with another man. Later, as Kowalski moves toward the ISS dragging Stone tethered behind him, he asks her if anyone is looking up and thinking about her. This elicits her most intimate revelation, that she had had a daughter who died in a freak accident. There is also no Mr. Stone waiting at home for her. Thus although the two characters have different personalities, both are escaping loneliness by a retreat to the beauty and peace of space.

Finally, there is the last shot, with Stone seen from behind against the sky, covered by light clouds. It reverses the opening, when we were in the opposite position, looking down at the earth from space, with the clouds of a huge hurricane prominently visible. There Stone drifted in space, held in place by a large mechanical arm; here she struggles to regain her sense of balance after prolonged weightlessness and succeeds in walking a few steps, thanks to gravity.

Like motifs, careful motivation of action helps us navigate through the plot. Given the rapidity with which new information is thrown at us as the narrative progresses, the screenwriters are careful to set up major premises in advance so that we will quickly understand them when they arrive. In the opening scene, as Kowalski swoops cheerfully around the shuttle, Houston asks about the supply of fuel in his jetpack. He reports that it’s 30% down. Not a lot, but enough that we are prepared for the moment after the disaster when he says he’s running “on the fumes.”

During the opening, the messages from Mission Control thoroughly forewarn us of the rapidly approaching hail of space debris. After it passes, Kowalski has Stone set her watch for 90 minutes, since that is when they can expect the same debris to return–as it does at regular intervals to destroy the ISS and the Chinese station. Stone reminds us of this danger when she exits the Soyuz vehicle to detach its parachute, muttering, “Clear skies with a chance of satellite debris.” The presence of the deployed parachute also sets up the moment when the chutes of the Chinese pod deploy as it nears its splashdown in the final sequence.

As Stone struggles to get aboard the ISS, Kowalski converses with her via radio. They mention her training with landing vehicles. Her only experience has been with simulators, and in every case she crashed them. Still, as Kowalski points out, she knows something about them–a point which proves vital in the dream scene discussed above, where Stone’s mind summons up a memory about how launching and landing space vehicles are not all that different.

Apart from creating a brief scene of suspense, the fire in the ISS introduces the fire extinguisher and demonstrates how, in a situation of weightlessness, the extinguisher propels Stone through space. This prepares us for the crucial scene in which she uses it as Kowalski had used the jetpack, allowing her to reach the Chinese station despite being untethered in space.

Character motivation, fortuitous events, and religion

Throughout the film the cause-effect chain remains fairly straightforward, with one major exception that I’ll get to shortly. But because the characters are reacting to rapidly changing circumstances almost entirely beyond their control, the outcomes are often fortuitous rather than the result of character traits. This is not to say the film uses numerous coincidences. It is not coincidence that Stone manages time and again at the last possible moment to grab a pipe or handle on the outside of a space vehicle. She’s aiming to do that, so she manages it not by coincidence but by luck.

Some of the most crucial events in the film are partly a matter of character motivation, but the outcomes of Stone’s and Kowalski’s actions are fortuitous. Stone apologizes to Kowalski for not having immediately obeyed his order to stop trying to repair her equipment and head for the space shuttle. She presumably continued with the rebooting because she is a dedicated researcher, reluctant to abandon her important work even when in physical danger. Yet as it turns out, reaching the space shuttle interior would have been fatal. When Kowalski and Stone do reach the shuttle, they find it split open, its crew dead–just as the pair would be had they retreated inside immediately. Stone’s delay actually saved the pair, though neither character could know this at the time.

Less obviously, Kowalski accidentally dooms himself. We see him in the opening minutes, cheerfully circling the shuttle and Hubble, playing music, telling anecdotes, and apparently hoping to stay outside the shuttle long enough to set a record. Presumably he has already accomplished his task in the space walk, or perhaps as the most experienced member of the team, he is watching over the other two. He is also, however, wasting fuel–fuel that he doesn’t realize he may need. Later, when forced to travel through space to rescue Stone and then to make it from the shuttle to the ISS, his tank becomes empty just before they reach it. His inability to maneuver without endangering Stone leads to him detaching his tether and stranding himself in space forever.

There are other fortuitous events. Stone is lucky that her Chinese pod lands in a body of water but close enough to shore that she can survive the impact and get onto land easily. It is probably by chance that in entering the Soyuz craft, the weightless fire extinguisher blocks the door and that she pulls it into the craft rather than pushing it out. Later the extinguisher enables her to propel herself to the Chinese station. There are also obstacles fortuitously created, as when Stone discovers that the Soyuz vehicle has no fuel–presumably because its supply tank has been ruptured by flying debris.

There may be one major exception to this dependence on accidental causes and effects: the religious motif. This is a strange motif, since it doesn’t become significant to the plot until fairly late. Early in the complicating action, as Kowalski and Stone journey toward the ISS and he asks her about her life on earth, he’s playing a country song, “Angels Are Hard to Find.” It’s playing when Stone mentions her daughter’s death; Kowalski soon turns it off to pay more serious attention to her story. At the time, the song doesn’t seem relevant. About seventy-two minutes in, the religious motif returns and becomes more prominent. Stone discovers that the Soyuz fuel tank is empty. The vehicle drifts as sunset settles on the earth below. We see vast snow fields and fjords below, and frost forms on the window. (The cut to the frosty window is one of the film’s few apparent ellipses.) There is a brief shot of a Russian icon inside the Soyuz (Christ as a child carried by John the Baptist, I think).

Immediately after this, Stone makes contact with someone on earth. She tries to communicate her mayday call. Gradually she loses hope and begins woofing in echo of dogs she hears on the radio. She says she’s going to die. During this scene she talks of how there is no one on earth who will mourn or pray for her soul. She asks the man to “Say a prayer for me.” She adds, “I’ve never prayed in my life. Nobody ever taught me how. Nobody ever taught me how.” A baby is heard on the radio, and the man apparently sings a lullaby to it. Stone sadly comments, “I used to sing to my baby. I hope I see her soon.” At that point she dials down the oxygen inflow and says, “Sing me to sleep, and I’ll sleep.”

As she falls asleep, a knock on the door is heard off, and Kowalski enters the Soyuz. He drinks some of the hidden vodka, chats, and tells her to use the soft-landing device. Although he sympathizes with her desire to surrender to the eternal peace of space, he encourages her to save herself rather than giving up: “Ryan, it’s time to go home.” After his disappearance, Stone once again strives to save herself.

Once she has reached the Chinese landing pod, she struggles to cope with its instrument control-panel. As the countdown clock starts running, there is a tilt up to a little Budda figure, roughly in the spot where the icon had been on the Soyuz. As Stone works, she talks to Kowalski, asking him to find her daughter: “Tell her that she is my angel.”

Finally, back on earth, in the final shot Stone struggles to rise, muttering “Thank you,” before walking away from the camera, which tilts up to a low angle of her against the sky.

Though this motif appears late in the film, the narrative stresses it. Something is going on here, but what?

Most obviously, Stone seems to become somewhat religious, despite never having prayed before. Perhaps this is simply an emotional change that allows her to reconcile somewhat to her daughter’s death, to feel hope and enthusiasm for carrying on with her attempts to reach earth, and to accept her survival as a gift to her from some sort of deity.

Given that the startling visit of Kowalski, whom we assume to be dead, to the Soyuz and also his providing Stone with the one bit of information she needs in order to carry on, we might assume that this scene presents a sort of miracle. Kowalski’s visit makes him a quasi-angelic figure bringing divine intervention to Stone, perhaps, or simply a vision inspired by a divine power.

Yet his return is cued as a dream, with Stone falling into a sleep that she assumes will end in death. We all have had some sort of experience with a dream providing inspiration or the solution to a nagging problem. As Kowalski points out, Stone should know that taking off and landing are essentially the same thing; it was part of her training. The dream does not give her the knowledge but rather reminds her of it. Indeed, after she wakes up, she still has to struggle to remember what she learned about soft landings and also consults the manual.

Everything in the dream reflects things we already know about the two characters. Kowalski mentioned knowing where the vodka is kept. Earlier he had reminded her of things she knows about landing from her training with simulators. His words to her about the sorrow of losing her daughter and the temptation to surrender to the eternal peace of space recall her own line from the beginning when he asked her what she likes about space: “The silence. I could get used to it.” (Cuarón, in an interview with Anne Thompson, refers to Kowalski’s return as “a projection of herself in a dream.”)

Seemingly Stone gains some sort of religious belief or spiritual consolation. While working on the Chinese pod’s controls, she talks animatedly to the absent Kowalski, whom she apparently envisions meeting her daughter in an unspecified afterlife. The “Thank you” at the end I take to be the conclusion of this monologue in the pod, thanking Kowalski. In a truly classical film, a character mentioning never having learned to pray would surely say a prayer later in the film. Stone never does. I interpret the religious motif as signaling a transformation of her attitudes rather than implying some sort of divine intervention to rescue her. Either way, some viewers might take this motif to be heavy-handed or saccharine, but its ambiguities could prevent others from having such reactions.

It all worked

The combination of narrative techniques that I have just analyzed obviously appealed to many of the the people who have seen the film.

On November 1, Box Office Mojo summed up the film’s career since its October 4 release:

Through four weeks in theaters, Gravity earned $206.1 million, which accounted for just under a third of total domestic box office earnings in October. It’s already the highest-grossing movie ever to be released during the Fall (September or October) and will earn at least another $50 million before the end of its run.

Gravity‘s remarkable success can be attributed in part to Warner Bros.’s great marketing campaign, which helped the movie set an October opening weekend record ($55.8 million). From there, the movie had an unprecedented second weekend hold thanks to world-of-mouth that asserted the movie needed to be seen on the biggest screen possible (and preferably in 3D). Speaking of 3D–Gravity‘s box office has been pumped up by the fact that most people (around 80 percent) are choosing to pay an extra few bucks to see the movie in that premium-priced format.

According to Variety, “Imax contributed 21% of the opening-weekend domestic cume for the film.”

(Even I, no fan of 3D, have seen it in that format at two of my three viewings so far and would do so again.)

Abroad, the film has also done well. As of November 6, its foreign box-office gross is about $207 million, with the film still to open in several major markets, and its domestic take has risen to almost $220 million, expected to top out at $260 million.

[Nov. 10: Box Office Mojo is now estimating that Gravity will ultimately gross about $660 million worldwide. It opened this weekend in the United Kingdom, where 89% of its ticket sales were for 3D screenings.]

This is also one of those rare films people see in theaters repeatedly within a short period. By the end of its opening weekend, three percent of audience members said they had already seen it more than once. On October 21, the film’s official FaceBook page asked fans, “How many times have you seen the film in theaters?” One, two, or three times were common, but even by that date, two and a half weeks into its run, there were a few who had seen it four or five times. Many single and repeat viewers mentioned plans to see it again. Quite a few also specified which formats they saw it in at the different screenings. Dan Fellman, head of Warner Bros.’s domestic distribution, remarked, “This is a phenomenon where people are asking friends and family not only if they’ve seen the film, but where.”

Some moviegoers (and critics) have found the film boring. But those who love it really love it.

Our next entry will deal with the film’s style and how it was achieved.

Coincidences can play many roles in a film’s plot, as we discuss in this entry. You could take Gravity’s ambivalent gestures toward Stone’s spiritual redemption as another example of Hollywood’s strategic ambiguity about controversial themes.

Jason Mittell has written an essay, “Gravity and the Power of Narrative Limits,” which nicely complements my analysis. He concentrates on the film’s relation to traditional genres, discussing how it departs from familiar conventions of science-fiction and survival narratives.

P. S. 9 November: After I linked to this entry on my Facebook page, Meraj Dhir commented that the song Shariff sings as he does his little weightless dance is from a famous number in Raj Kapoor’s 1955 musical Shree 420. Not exactly relevant to my analysis, but fun to know, so thanks, Meraj! You can see the number here.

NOTE: On November 8, after watching the film a fourth time, I revised this post, correcting a few errors and quoting some brief passages of dialogue that I was able to record on this go-through. I have not noted the changes with the usual strike-through lines, since it seemed too complicated and distracting to do so in this case.

I’ll never tell: JASON reborn

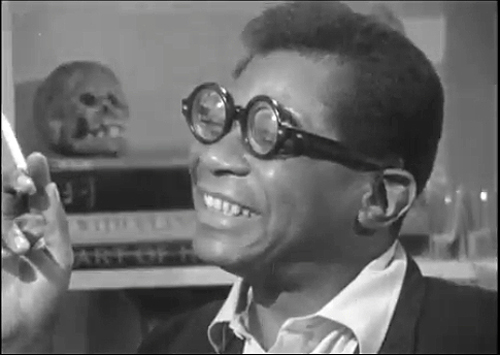

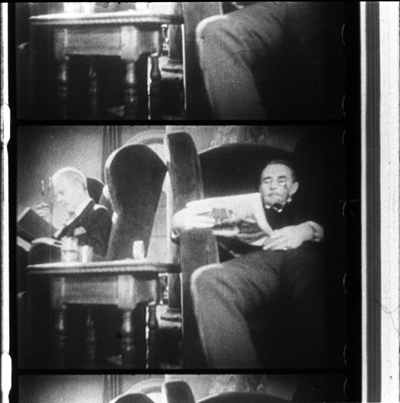

Portrait of Jason (1967).

DB here:

A white-walled apartment; no windows visible. Screen left: a day bed wedged into the corner. Center of screen: A fireplace and mantelpiece. Screen right: an easy chair with an end table boasting a lamp and ashtray. Behind it a bookcase. It’s as colorless a performance space as you could ask for, except perhaps for the skull on a bookshelf; but even that isn’t real.

In this arena a slender black man with thick Harold Lloyd glasses and a winning smile talks to us. His first words, delivered with calm sincerity, are immediately revealed as false.

My name is Jason Holliday. My name is Jason Holliday. (Breaks into laughter.)

(With a confiding smile) My name is Aaron Payne.

Over a single night, from 9 PM to 9 AM he talks to the camera, and eventually with the unseen filmmakers. High on marijuana and drunk on single malt scotch, he recounts his life as a gay hustler, recalls his family and childhood, and offers his analysis of how to behave around whites. He strikes attitudes, mimics the slaves in Gone with the Wind, and sings show tunes.

At first the filmmakers encourage him to tell this or that story, but late in the film one offscreen voice presses him. “Why’d you write letters about me?” “You should suffer.” “You’re full of shit.” Near the end Jason is sobbing. “If you don’t know,” he says, “I love you.” The offscreen voice is pitiless: “Stop that acting.”

Portrait of Jason (1967) is a legendary film that until recently had gone astray. Last Friday our Cinematheque hosted the US premiere of the restored version. The movie tells quite a story, but so too does Dennis Doros, VP of Milestone Films and the man whose tenacity brought back this delightful, disturbing record of Jason’s long night.

In and out of focus

It was a shocker in its day. What other film talked so frankly about gay life, race relations, and drug use? Where else would you hear virtually every four-letter word in the American vernacular? Shown in festivals and independent art houses, it won an astonishing level of praise. Here is Newsweek:

Jason lives, and Jason gives one of the most incredible performances ever recorded on film. This inverted Everyman, this anti-matter Jack Armstrong has a terrible tale to tell about how much it can hurt to be human, and he tells it in magnificently rich language with the gay desperation of an artist.

But the film was doubtless worrying. It circulated in the same year as Blow-Up, Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Bike Boy, In Cold Blood, I am Curious (Yellow), Rush to Judgment, and I, a Woman—a year in which studio films, exploitation, art movies, and the underground seemed to be joyously blitzkrieging conventional values and good taste. Portrait of Jason opened at the New York Film Festival after a summer in which American cities had been shaken by riots in black neighborhoods. Now came a film in which a black man blithely reveals the cynicism behind his shuck-and-jive for rich white employers. And he’s a gay prostitute.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

The director, Shirley Clarke, was a member of the New American Cinema group around the Film-Makers Coop and the magazine Film Culture, but she never fitted into any clear-cut category. She made dance films and some lyrical shorts like the zesty Bridges Go Round (1958), but she never joined the avant-garde tradition typified by Stan Brakhage, Michael Snow, and Ernie Gehr.

Her other feature-length films (The Cool World, The Connection) owed something to American cinéma vérité. Variety sourly remarked of Jason, “C’est la vérité,” and ran its review alongside a review of Frederick Wiseman’s Titicut Follies. But Clarke’s daughter Wendy recalls that although Shirley was friends with vérité filmmakers, she doubted that they could capture reality objectively. Leacock and Pennebaker would have found it impure to jab their own comments into the subject’s monologue the way Clarke and her lover Carl Lee do. Clarke’s approach is closer to that of the French cinéma direct, as pioneered by Jean Rouch and Chris Marker. In Le joli mai (1963) the filmmakers ask their interviewees frankly: “Are you happy?” This question underlies Portrait of Jason too.

Apart from the coaxing and goading interjections, Clarke’s filming method seems artless. There are fewer than fifty shots in 105 minutes, and they’re linked by black frames and out-of-focus passages. Both transitions mimic casual shooting. Yet Dennis Doros and Wendy Clarke pointed out that Clarke loved cutting. She was aware of the paradox:

I had enormous patience in terms of editing and I’ve always adored that part of making films, and in an odd way as I develop as a director I set up less and less situations to edit. The better I’ve become as a director, the less editing, the more I’m thinking in terms of the last twenty or thirty minutes that will have no editing at all.

In Jason the cutting isn’t as casual as it might seem. The blurry passages conceal edits, and the order of scenes doesn’t reflect the progress of the shoot. It will take patient research to determine the original chronological order of the reels we see. Clarke claimed that she enjoyed editing because at that phase she was really discovering her film.

Clarke’s apparently loose shooting, often running the camera until the magazine is empty, may seem a version of Warhol’s static films like Eat. It seems likely that she also learned from Warhol’s approach to performance. His psychodrama-based dramaturgy, as explained in J. J. Murphy’s fine book, constantly hovers between confession and put-on, and this is central to what happens in Clarke’s film. But Clarke gives her movie a more clear-cut narrative contour than Warhol would, with Jason’s monologue devolving from grinning self-assurance to stricken self-exposure.

Clarke and her crew acknowledge the act of filming, although they don’t emerge from behind the camera, as some do in The Connection. This recognition of artifice can encourage the subject to perform, to play up to the camera for the approval of the filmmakers and the audience. And a chance to perform is exactly what Jason wants. Now, he chortles, he can show off the nightclub act he’s been working on. The film is at once an audition and an effort to define himself. He’ll create “a picture I can save forever—one beautiful something that’s my own.”

So in the stage space between the day bed and the armchair, he strolls and poses. He fires off randy one-liners like “If I’d been a ranch, I’d be called Bar None.” Flipping his boa, he channels Mae West, Butterfly McQueen, Dorothy Dandridge, and Harry Belafonte. (Did he rename himself in honor of Judy Holliday?) He jiggles ice cubes in his glass with the winking panache of Dean Martin at the Sands. Clarke once said that in watching the rushes she was reminded of her choreography films: Jason seemed to be dancing.

To recover from his numbers, Jason flings himself offstage, flopping back on the daybed or sinking into the armchair as his cigarette burns down to the filter. In these moments, he seems to be candid. He admits that even with all the money he’s borrowed from friends, he’s not ready to take the show-business plunge. Drunk and giggling, he tells of childhood beatings with a razor strop: you mustn’t stick your butt up high but press yourself against the bed; that hurts less. His oscillations of mood are dislocating, passing from exuberance to frankness to self-mockery. Moments of self-celebration (“I’m a male bitch”) can also seem inadvertent glimpses of vulnerability–which may be exactly what Jason wants us to think. At one level Jason gives lessons in impression management.

I see his tears at the climax as born of authentic pain, but I can’t be sure. Earlier in the film he bragged: “When I do my pathetic bag, I’m really pathetic.” The layers of Jason’s one-queen show seem endless. Clarke said in an interview that everything he does on film—his jokes, stories, even the weeping—she had seen many times before. “His entire life is a role.” He seems to spill everything, but one of his mottos, delivered with finger snaps, is: “I’ll never tell.”

Treasure hunt

Wendy Clarke, Dennis Doros, and Maxine Fleckner Ducey.

How was this extraordinary film brought to light again? That was the story Dennis Doros told at our departmental colloquium the day before the screening. His company Milestone has specialized in reviving forgotten or neglected films of all types, including American independent work like Kent MacKenzie’s The Exiles and Charles Burnett’s Killer of Sheep. Simply trying to get a quality version of Portrait of Jason took him on a hunt that revealed, after many twists, that the closest thing to an original print was residing here in Madison, Wisconsin.

Back in the 1960s and early 1970s, our Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research made an effort to collect off-Hollywood cinema, including the works of East Coasters like Emile de Antonio, Doris Chase, and Shirley Clarke. Clarke’s collection, like several others, harbors vast amounts of personal papers and film material.

Clarke shot Jason on 16mm, but no negative has yet been found. There were 35mm prints made, and some wound up in archives, notably at the Museum of Modern Art. But among the material Clarke began giving the Center in 1973 were six reels of silent 16mm footage and several reels of sound recording. When they were inspected, the reels were believed to be either outtakes or stretches of a rough cut. We didn’t yet have a release print of Jason to compare them to.

Many years later, after searching high and low across the world, Dennis had the good idea of adding up the footage counts of our reels. The length was four minutes longer than the final running time of the film. After further research, our footage was revealed as Clarke’s original cut of summer 1967, which was trimmed and revised for the film’s official premiere at the New York Film Festival. This was, says Dennis, “the great irony in the search. Because Shirley Clarke had created a film that was meant to look unedited—filled with out-of-focus shots and black leader—Shirley’s 16mm fine-grain master was hidden all these years as outtakes!”

Our archivist Maxine Fleckner Ducey assisted Dennis throughout his quest. They found that the sound material, alas, was indeed outtakes, and Dennis still needed a good 35mm print of the Film Festival/release version for sound and final checking. More hunting ensued. Searching through the WCFTR collection, Dennis found an old telegram from Jacques Ledoux of Belgium asking permission to borrow a print from the Swedish Film Institute. Dennis contacted Jon Wengstrom at that archive, and soon he had a copy that could guide the restoration.

The whole process was enabled by funding from the Academy and from a Kickstarter campaign. To support that effort, Dennis and his wife and business partner Amy Heller made a video that traces their search for Jason. Their restored version had its world premiere at the Berlin Film Festival, and it will go on to other festivals and selected theatres. The image and sound quality far surpasses that of earlier versions in circulation.

A sort of epilogue came when Dennis and Wendy Clarke visited Madison last week. They dipped into Shirley’s vast collection, and in only two days they found treasures of a personal as well as professional nature. Perhaps some of their discoveries will surface as bonus materials on the eventual DVD release. Dennis and Wendy stayed on to introduce Friday’s premiere and take questions.

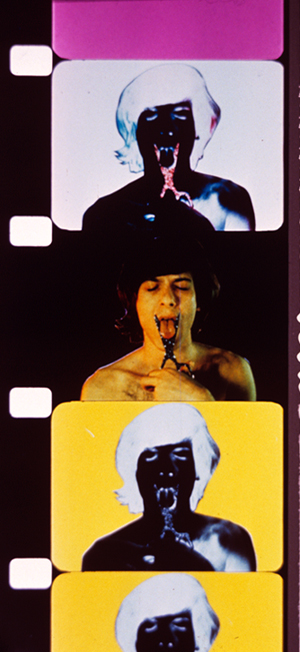

A charming pendant to Jason was the screening of a half-hour of Wendy’s Love Tapes series. In the 1970s Shirley shifted to making videos, and Wendy followed her path and became a major video artist. The series began as Wendy’s video diaries, but in 1977 she began recording people talking about what love means to them. Each person sat alone in a room, seeing her or his image on the monitor, and talked for three minutes. Over the years, the formats shifted from reel-to-reel tape to VHS to DVD, but the theme remained the same.

Wendy now has over 2500 tapes, shot in museums, schools, shopping malls, prisons, centers for battered women, and even in a booth at the World Trade Center. Ideally, she says, everyone on the planet should make one—a goal that isn’t so far-fetched thanks to smart phones and the Internet.

The Love Tapes assembly we saw with Jason was broadcast on PBS in 1982, and it was alternately grave and exhilarating. People celebrated love they’ve found but also mourned its passing and reflected on how it shaped their lives. Wendy has tried other themes, notably death, but love works best. “You talk about everything in it.” Sort of what happens in Jason too.

Thanks to Wendy Clarke and Dennis Doros for their visit to Madison, and to Jim Healy for facilitating it. Thanks also to Joe Lindner and Mike Pogorzelski, two graduates of our program, for enabling the Academy to take part in Milestone’s project. Maxine Fleckner Ducey was a great help on the Milestone project and, on a daily basis, makes us proud to have the WCFTR connected to our program. Thanks as well to current WCFTR director Vance Kepley for background information on the Clarke collection.

Project Shirley recently won Milestone an award from the National Society of Film Critics (the company’s sixth). Look for more Project Shirley material to surface from our holdings. And who, as Dennis asked in colloquium, will write the first book on this remarkable artist?

I drew Clarke’s comments about editing from Gretchen Berg, “An Interview with Shirley Clarke,” Film Culture 44 (Spring 1967), 55; and “A Conversation—Shirley Clarke and Storm de Hirsch,” Film Culture 46 (Autumn 1967), 47. The Newsweek review of Jason appeared in the issue of 6 November 1967, and the Variety review appeared on 25 October 1967.

The trailer for the new version of Jason is here; it includes side-by-side comparison of an archived 35mm print and the restoration. Clarke’s discussion of Jason’s role-playing is captured in an episode of the TV series Cinéastes de notre temps, by Noël Burch and André S. Labarthe. You can watch it here.

On The Connection, see J. Hoberman’s lively introduction on the New York Review of Books blog. Jason is a prototype of the portrait genre of documentary, a subject covered with care in Paul Arthur’s essay, “Identity and/as Moving Image,” Line of Sight: American Avant-Garde Film since 1965 (University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 24-44.

A sample of Wendy Clarke’s Love Tapes is here.

Love Tapes (1982).

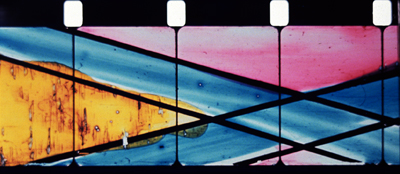

16, still super

From Lost & Found Film Club.

DB back:

While I was semi-snowbound in Evanston, IL, messages kept rolling in. Many of them were responding to my account of surrendering my 16mm movies and gear. That post’s whiff of nostalgia was caught by Gary Meyer, co-director of the Telluride Film Festival.

Don’t get me started on 16mm memories. I started showing movies in 8mm at about ten years old and by thirteen I had two for changeovers on silent classics rented from Cooper Films in Chicago. For about $2 I got a full feature and short including postage. Using my parents’ record collection I could score the films. . . .

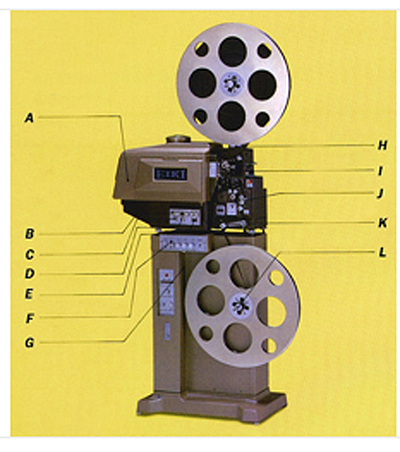

Graduated to 16mm in high school when a local church and the library each offered use of their projectors and I started collecting prints seriously. In college I got a job in the media center showing films, cleaning prints and projectors. When the department decided to buy Bell & Howell Auto-Shreds, they sold off the old projectors for $50. I knew each machine intimately and selected the quietest, gentlest RCA 400 which I still have in a booth in my basement. One of my favorite projectors.

With 16mm projectors I have shown movies on garage doors from my apartment, in a barn, an orchard or two, and most famously on clouds, which resulted in the police department getting many phone calls about aliens.

Gary reports that his former venue, the Balboa Theatre, has given its theatrical Eiki projector to the San Francisco State University film department, but it can be borrowed back if ever needed. A more acute sense of the passing of an era was reported by program curator and Czech arts consultant Irena Kovarova:

One of the sad moments in my film history was being invited to the Czech Embassy in Washington, DC to visit a room of 16mm film piles. I was asked to pick and choose which ones should be saved and which would be chucked away (the majority). It was a collection of films that the Embassy inherited from the Communist-era offices when the staff was shipped films for their entertainment (Czech popular comedies) and of course tons of “travel” and “propaganda” stuff. It was impossible to know what was really there and a lot was mediocre, but still such a sad thing that no one could really dig in and explore.

Secrets of the Incas, and non-Incas

Projection booth, Cleveland Cinematheque.

But there was good news too. In the course of that entry, I said that 16 was “nearly dead” as an exhibition format. Trust this blog’s alert readers to give a more upbeat emphasis and offer some weighty counterexamples. Don’t hesitate to use the hyperlinks!

I was confirmed in my belief that archives will keep the format going. I hear from our old friend Antti Alanen of the National Audiovisual Archive of Finland, that 16 flourishes in Helsinki.

We still keep screening 16mm regularly at Cinema Orion, and for the moment print access is still good. We recently showed three programs of Stan Brakhage movies (from Canyon Cinema) and one programme of Rose Lowder movies (from Light Cone of Paris), all in the original format of 16mm, all prints and colours perfect.

I haven’t seen Brakhage on DVD, but those who have remarked that it is not the same thing. There is something about the special sensuality of 16mm which is essential to the Stan Brakhage experience. All of those films fill up the senses.

Besides Canyon Cinema and Light Cone, LUX in London still seems to be well-stocked with good 16mm prints in commercial distribution.

Bracing news. Antti mentions as well that he used to be able to access 16mm films made for the Finnish Broadcasting Corporation, but now the agency has realized that the prints are irreplaceable and provide digibeta copies instead. The loss for showing is a gain for preservation.

I indicated as well that colleges, universities, and museums will probably maintain 16mm prints and showings. My correspondents have confirmed it, and offer some ripe local detail. Tracy Stephenson of the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, tells me that they have shown films since the 1930s and may be the only venue in Houston that still screens 16. They have a program of jazz shorts coming up in June.

Here’s John Ewing of Cleveland:

I still show 16mm on occasion (and two-projector 16mm at that) at both of my venues: the Cleveland Cinematheque and the Cleveland Museum of Art. In fact, I just ran the 16mm program from the 50th Ann arbor Film Festival tour last Thursday night at the Cinematheque. Last time I showed 16 at the art museum was in December when we screened an IB Tech print of Secret of the Incas, from the Academy Film Archive.

From the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, Brian Hearn writes:

We are pretty serious about 16mm and maintain a modest collection of about 500 prints, ranging from Lumiere Brothers shorts to studio features to avant-garde to educational films to 70s exploitation trailers. As the film medium dematerializes it makes me appreciate our collection even more, vinegar and pink fading prints included!

Calling a collection of 500 titles modest makes me grin (in envy). On the university side, Jon Vickers supplies other breathtaking information:

Indiana University Cinema programs from the University’s 16mm collection on a regular basis, with 16mm screenings at least once each month. In the IU Libraries Film Archives, there are over 80,000 items, the majority being 16mm. Within that collection is Lilly Library’s David Bradley Collection, spanning the history of cinema in the US and Europe, including classic, obscure, and some unique titles. We dedicate a series each semester to the holdings within the Bradley Collection (programmed by Film and Media Studies grad students), as well as program from the educational/non-theatrical collections and holdings.

We can’t imagine a day when we will stop screening 16mm.

With that treasure house, I can see why! Pablo Kjolseth of the University of Colorado at Boulder also defends the format resolutely. Pablo has written one of the most fiery and persuasive polemics on digital cinema. Not only does his program have an extensive library, but they are still actively collecting in 16. Moreover, as home to the annual Brakhage Center for Media Arts symposium on experimental film (coming up next week), Boulder’s campus relies constantly on 16.

Hipsters, nostalgics, and toddlers

Eiki EX-9100 Professional 16mm Sound Optical/Magnetic projector with 2000-watt lamp. Currently available on eBay for $8,500.

Perhaps the most cheering news comes from those enterprising programmers of films for public venues, both for-profit and not-. Barak Epstein of the Texas Theater uses Kodak Pageants (of my fond memory) with manual changeovers and a manual audio fader. Pittsburgh Filmmmakers, writes Gary Kaboly, uses its Kinoton and Eiki machines every couple of months. He adds:

Throwing around the idea of a “classic 16mm experimental” series in the fall. Young Hipsters see attending a 16mm show as an “event.” Old Hipsters always describe what an Art House was “back in the day.”

The Cinefamily venue of LA has established itself as home to what the local paper called “pathologically idiosyncratic programming,” and 16 adds sharp spice to the mix. Here’s Hadrian Belove, the Head Programmer, on his personal quest and the formation of the Lost & Found Film Club:

I’m definitely of an age that would be post-16mm collecting, but still got hooked. One of the great appeals of 16mm for me is it feels like the final frontier for discovering true rarities. . . . It’s kind of the ultimate format for a “digger.” Finding Christian experimental films, industrial films, student films, and copies of TV movies, episodes, and even theatrical features that simply never made it to any form of video is de rigueur.

Nothing gives me more pleasure as an explorer than trolling eBay for 16mm.

I began showing things I would buy after hours to the staff here at Cinefamily, and hadn’t even considered it as a public show. Over time, some of the “kids” on the staff started buying their own 16mm ephemera, and finally proposed taking our private show public. I thought what the hell, cost is low, and we were doing it anyway. I gave them a terrible time slot I wasn’t using (10:30 on a Wednesday).

They launched this:

https://www.facebook.com/LostFoundFilmClub

Anyway, the first show had 100 people, even at 10:30 on a Wed night. Maybe it’s those grilled cheese sandwiches!

Finally, I had noted that FOOFs (Fans of Old Films) had a noble tradition of gathering in annual conventions. Jessica Rosner, film scout extraordinaire, writes of screenings at the upcoming Syracuse Cinefest: “The majority of films will STILL be in 16mm and they will be films that are rarely available to be seen any other way.”

A further note from Pablo Kjolseth brings things back to Gary Meyer’s childhood and the FOOF in us all. Pablo hosts summer screenings in his back yard.

My Eiki Xenon projector shoots through a guest-room window to the screen in the backyard – transforming the guest room into a “projection booth” of sorts. The next [picture] is a nice ominous shot of Darth under stormy skies. . . . Although I’ve played around with some digital screenings, everyone prefers the 16mm shows. And this even though I don’t do reel-changes or employ a take-up tower – thus having small intermissions between each reel change. These intermissions are quite popular, as it allows folks time to refill their drinks, go to the bathroom, and comment on what they’ve seen so far.

As many as 60 people might show up for any screening. As the children in the neighborhood are always entranced by the projector, I try to make sure to have a couple family-friendly screenings every summer. My neighbors are great: they’ve even tolerated backyard screenings of such titles as DAWN OF THE DEAD and THE TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE – admittedly poor choices, given that in the summer heat most people sleep with their windows open and late at night they might not appreciate all the screaming and, well, chainsaws. But, so far, no complaints!

None from my end, either. Is it just me, or does Darth look more menacing here than in any other setting?

After reading these communiqués, two thoughts. First, a great many programmers are working very hard to track down and screen unusual items for their audiences. These folks and their peers are committed to exploring cinema along routes that bypass the multiplex. Who wouldn’t rather watch Secret of the Incas than, say, The Last Exorcism Part II?

My second thought comes with a pang. Was I wise to clear out my 16 collection? Our department and other collectors benefit, but still… A basement will dry out, but films that are gone are gone.

Thanks to all who wrote me, and to the Art House Convergence list serve for its stimulating conversations.

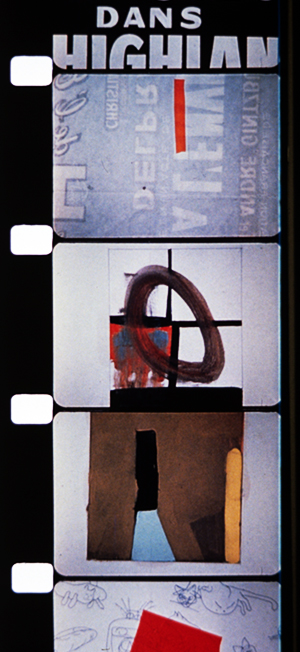

Sweet 16

REcreation (Robert Breer, 1956); T.O.U.C.H.I.N.G (Paul Sharits, 1969).

DB here:

Snows and thaws and refreezing, amplified by a torrential rain, gave water a new path into our basement. We’ve spent about two weeks emptying bookshelves, drying them out, and shifting books to other places. No volumes were damaged, but we had to make space in the dry areas for the migrant titles.

That meant facing up to the problem of 16mm.

The solution was drastic.

Narrow-gauge movies

My film collecting started with 8mm. Not super-8; that was invented later. (Imagine how old I am.) I made my own movies in 8, but I also bought, from the venerable Blackhawk Films of Davenport, Iowa, copies of films in that format. Most memorable was the Odessa Steps reel from Battleship Potemkin, which I projected often on my bedroom wall.

Not until I went to college and joined a film club did I lay my hands on 16mm. I suppose if you start out handling 35mm, 16 looks skinny and 8 looks like a toy. But moving from 8 to 16, I could see only improvement. You could, with the sharp eyes of the teenage geek, actually see the image on the strip. I projected many films on our JAN surplus projectors, and one weekend I hauled a print of Citizen Kane to my apartment to watch several times. Do I need to add that all this was in the 1960s, long before films became available on videotape?

Arriving in Madison in 1973, Kristin and I bought a Kodak Pageant, the 16mm workhorse. Not as good as a Bell & Howell, most aficionados would tell you, but fairly cheap and easy to handle. When we moved from apartment to apartment, the Pageant went with us.

In 1977 we bought a house, and I set up a jerry-rigged projection room in the unfinished basement. In our second house, where we still live, I was able to set up something more permanent. Now there were two projectors encased in a booth and mounted on a platform.

We spent many hours watching movies in that currently soggy basement, with its burgundy carpet and dark wood paneling. Although the room lacked the comforts of what we think of as a home theatre, we sometimes screened things for big groups, either a party or once in a while students in a seminar.

In both venues, we previewed movies we were showing in courses and revisited some of our growing collection: The Shop Around the Corner, High and Low, True Stories (must blog about that some time), You Only Live Once, and so on. I’ve already expounded on the key role of His Girl Friday in our mini-cinémathèque.

By then Kristin and I had also started working with 35mm prints in archives and with 35mm trailers we scavenged to make slides for lectures. For a brief while we even had 35mm in our screening space, but with only one projector, shows stretched too long. Although home video had taken off, Betavision, VHS, and even laserdiscs couldn’t compare to a good 16 copy. We continued to collect and show on film, as did our department.

In the last decade, improvements in digital projection, along with the arrival of Blu-ray, led to the decline of 16 in our local media ecosystem. Our department still shows a lot of 35, but 16 seems mostly the province of our experimental and documentary courses. As for us, we hadn’t screened 16 at home for some years. Then came the February leak, and we had to face the problem.

We’d already given many of our 16mm titles to the department, keeping our most fond treasures at home, thinking we’d watch them some day. Now we needed the space that those cans and cases occupied. Anyhow, it was probably time to let go. So we decided to surrender the features, the shorts, the cartoons, the splicers and the rewinds and the six Pageants—everything.

Our house is a museum of defunct technology. Just recently I surrendered my lovely Teac reel-to-reel tape recorder. Packed away are hundreds of Beta and VHS tapes. On groaning shelves sit hundreds of laserdiscs, mostly Asian. Yet under a roof that houses no fewer than six laserdisc players, there is no trace of the predominant nontheatrical film format of the twentieth century.

FOOFs

Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates (1966).

Nowadays it’s easy to own a “film”—or rather a disc or file or stream of pixels fed to your display. (Though I wonder what it means to “own” something sitting on the Cloud in your virtual locker.) Back in the day, joining the ranks of 16mm collectors meant a real commitment. You needed to buy gear, you needed to clean and inspect the films, and you needed to learn a little projector maintenance. You probably subscribed to The Big Reel and Classic Film Collector, tabloids that ran ads selling or swapping prints and equipment. And you usually went to film collectors’ conventions, jamborees of selling, trading, and movie watching. The three biggest events, Cinecon (Los Angeles), Cinefest (Syracuse), and Cinevent (Columbus, Ohio), brought together the overwhelmingly male tribe of FOOFs: Fans of Old Films.

FOOF collectors had good hunting in those days. There were plenty of 16mm prints floating around, but quality varied. The best were those cast off from legit distributors. Made from internegatives drawn from 35mm positives, they usually had good tonal values. At the other end of the scale were the dupes, copies pulled from 16mm distribution prints. These ranged from acceptable to awful; but if you wanted a rarity, you might have to spring for a dupe.

In the middle zone were TV prints, probably the majority of copies in circulation. When studios licensed their pre-1948 libraries to television, go-between companies like C & C put together packages of prints to be sold to local stations around America. Small stations in the hinterlands harbored scores of 16mm copies, to be trimmed, filled out with commercials, and broadcast outside prime time, and sometimes within it as “Million Dollar Movie” or whatever. It’s still not fully appreciated, I think, how many baby-boomer auteurists around the country caught classics in the pre-dawn hours on local television.

But as network and syndicated programming expanded, there was less room for old movies. Why run a 1936 Paramount picture when you could show color re-runs of Bewitched or The Six Million Dollar Man? The stations’ 16mm prints were headed for landfill when enterprising collectors and entrepreneurs salvaged them. You could tell when you got a TV print. It might carry a packager’s logo; it would have low contrast; and splices between scenes would signal where the commercials had been jammed in.

FOOFs had their demons and demigods. Principal among the demons was one colorful character, who had the habit of bothering collectors circulating versions of old classics to which he claimed current rights. In The Sneeze, FOOFs made fun of the man who, releasing recovered prints of Birth of a Nation and Keaton films, made sure his own name featured prominently in the credits.

Among the demigods were Kevin Brownlow, he who had rescued Napoleon, and David Shepard, who started out at Blackhawk and eventually founded Film Preservation Associates. Most legendary of collectors was William K. Everson, who died in 1996. Thousands of prints were squeezed into his two Manhattan apartments and spilled over into the storage areas of NYU’s film department. He acquired many of his films in exchange for services he rendered to Hollywood studios. His gems were screened in his courses, in sessions of the Theodore Huff Memorial Film Society, and in lectures he presented around the world. I remember his excellent presentation on Joseph H. Lewis at Chicago’s Art Institute Film Center, where he showed clips from Lewis’ Poverty Row productions and even some credit sequences Lewis had crafted.

Bill brought a magnificent selection of titles to Madison in the early 80s, and many of them, such as Bulldog Drummond (1929) and Justin de Marseille (1935), remain rarities. Generous beyond measure, he also let NYU faculty and students borrow his movies. When Annette Michelson needed to see East of Borneo (1931) for her essay on Joseph Cornell’s Rose Hobart (1936), she turned to Bill. All of this largesse was made possible by the portable, user-friendly format of 16mm.

Freezing the frame

Teachers, filmmakers, and collectors had a special relation to 16mm. In addition, as researchers, we developed an unusually intimate rapport with the format. When I started teaching, I felt the need to illustrate my lectures with images from the films. My first efforts involved setting up a 35mm still camera on a tripod and photographing from the screen. If the projector could stop on a frame, so much the better; but even if not, you might snag an acceptable shot. The projected image would be surrounded by darkness. Today I wince at the results, as with this shot from Crime of M. Lange, one of the few old slides we haven’t cast out.

You could get sharper slides with a gadget called a Duplicon, but it cropped the 4 x 3 image to something like 3 x 2.

When Kristin and I decided to write Film Art: An Introduction, the few introductory textbooks relied almost entirely on production stills, those images shot on the set and circulated to promote the film. The Museum of Modern Art had an archive of production stills, and then as now, publishers turned to such collections for illustrations. As part of the first generation of university-trained film researchers, we doggedly insisted that all our examples would be actual film frames.

Today, digital video has made grabbing frames easy. But before the late 1990s, it was hard. Videotape frames looked terrible, as some books from the 1980s attest. To get decent quality, you needed access to prints. You needed a way to put a reel onto rewinds or, ideally, a flatbed editor like a Steenbeck. And you needed a camera with an enlarging attachment. When you’d copied your frames, you took the exposed film to a lab, where you hoped for a passable result. Black-and-white shots were easier than color, which required blinding lamps of a color temperature matched to Ektachrome or Fujichrome or Agfachrome.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

When we could get access to 35mm prints, they were our prime sources for stills. I went to Copenhagen to copy frames from Dreyer films for my first book, and for her dissertation and first book Kristin made frames from 35mm copies of Ivan the Terrible loaned her by Janus Films. Before that, for the first edition of Film Art (1979), we took our color shots from 35mm prints, most of them in the New Yorker Films library. Dan Talbot and José Lopez kindly granted us permission to go to Bonded Storage in Fort Lee. There in the tall aisles of shipping cases we set up a rewind and patiently hunted for the frames we needed.

But most of the films we wanted to illustrate we could find only on 16. We rented prints and then took stills on a rickety gadget built for us by our friend David Allen. David bolted a pair of rewinds to a plank of plywood. That plank rested on a little table. Into the plank was cut a square slot for an upright light box. The box contained a bulb and was surmounted by a square of translucent plexiglass. The bulb could be put at the bottom of the box, for a photoflood lamp, or near the top with a cooler and dimmer appliance bulb for black-and-white. You positioned the film on the plexiglass and aimed the camera down at the film. A crude zoom lens allowed us to photograph a couple of frames of 16mm and one of 35.

We took the light box on our travels. Archivists certainly looked at us oddly when we brought the thing in, but they usually gave us permission to use it. We’d watch the film on a flatbed and bring the light box over alongside it. Laying the film gently on the surface, we’d poise the camera above it.

Here’s an example of what we got with our plywood setup, from Bill Everson’s print of Bulldog Drummond.

Over the years we improved our system. We bought better cameras, with sharper lenses. We found purpose-built attachments that hold the film strip firmly in place. (Alas, Canon and Nikon seem to have discontinued these rigs.) We used smaller lighting units rather than our curious box. For the last few decades we’ve shot horizontally rather than vertically.

Even in this age of video grabs, we make many frame enlargements on analog stock with 35mm cameras. Even if a film is available on DVD, some of the things we study aren’t preserved in that format. Of course many films aren’t available on video at all, and a great many of those were made to be seen on 16mm.

Format churn catches up with us

Notebook (Marie Menken, 1962).

Super-16 lives as a production format, but its older brother is nearly dead. True, a few die-hards like Ben Rivers continue to shoot on 16mm, but its future is mostly all used up. James Benning could make 16mm look like 35; when I asked him how he did it, he answered: “I use a light meter.” But even Jim has switched to digital. As for projection, many colleges and art centers have pitched out their 16 equipment.

Since our earliest editions, Film Art included discussions of two remarkable films: Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958) and Robert Breer’s Fuji (1974). These have not been, and might never be, released on digital disc. Yet by the end of the 2000s, we found that virtually none of the users of our book screened these films for their classes, and curious readers without access to 16mm projection couldn’t easily see them. Reluctantly we cut them from the tenth edition of last year. We replaced A Movie with Koyanisqaatsi to illustrate associational form, and Fuji was replaced by Švankmajer’s Dimensions of Dialogue as an instance of experimental animation. Both titles are available on DVD.

Thanks to the Internet we’ve been able to revive our original discussions of the Conner and Breer films on our site here. We hope that will help the few loyal chevaliers who told me that they did indeed use the films in their courses. But our choice points up a larger problem.

So many documentary and avant-garde films were made and circulated on 16mm that we are at risk of losing a very large slice of film history. We’re lucky to have some Stan Brakhage and Hollis Frampton films on DVD, but what about all the other titles that were distributed by Canyon Cinema, the Film-Makers’ Coop, and other groups? We can get DVDs of Frederick Wiseman documentaries, and some classic ones have been made available on archival collections; but there are many more that depended on 16mm platforms. Even bigger is the set of everyday 16mm movies: amateur films, home movies, and hundreds of miles of newsfilm, from both big TV networks and local affiliates. A great many of the “orphan films” championed by Dan Streible and his colleagues are in this narrow-gauge format.

Recall too that the films of those animators and experimentalists who work frame by frame, such as Breer and Paul Sharits and Paolo Gioli, cannot be studied closely on DVD. How could DVD reveal to us the nifty paintwork of Marie Menken’s Notebook? For that you need a light table, or someone able to photograph it and show you.

Archives will retain 16mm projectors and viewing tables as long as they can. They will preserve prints, perhaps migrating the most sought-after ones to digital formats. Passionate collectors like Tim Romano, who zealously pursues lost films and then donates them to the AFI, will find a way to use our cast-off gear. Our Film Studies department will hang onto the format until the last aperture plate cracks.

16mm was so much a part of our work, our play, our education—in short, our lives—that the separation was inevitably poignant. Pinned to the bulletin board in my basement booth was Ellen Levy’s poem, “Rec Room.” It is, I think, about the fragility and faultiness of the 16mm image, as made palpable in home screenings, and about how that fragility nonetheless carries a pulse of vitality. It begins:

The film assumes the texture of its screen

on the first projection. Audrey Hepburn’s face

creases where the rec room paneling once

took exception to it for the sake of

rephrasing it slightly—a lesson