Archive for the 'Experimental film' Category

Rebooked

3/60 Baum in Herbst (Kurt Kren, 1960). Hand-drawn soundtrack.

DB here:

It’s time again to write up books that fate and friends have sent my way. And I do mean books, as in printed matter on paper held together by string and glue and wrapped in a decorative cover.

Nothing against e-books, mind you. I’ve put out a couple myself (see right sidebar), and I’ve become more inclined to use them for my research. Every academic sometimes needs to read only parts of a book–a chapter that touches on your project, a bibliography that can help you, chatty footnotes that can suggest a new idea. If your library hasn’t got a copy and Inter-Library Loan is difficult, an e-book can be worth the investment. The only real problem is the prospect of buying, in any format, a book that you must read but that you know will be dire. (Names and titles omitted for the sake of the new year’s mood.) Then at least the e-book, being less expensive, can mitigate the pain of paying, if not of reading.

Direness isn’t on the agenda for the books I have on the desk today. All are worth your attention, in whatever format you can get them.

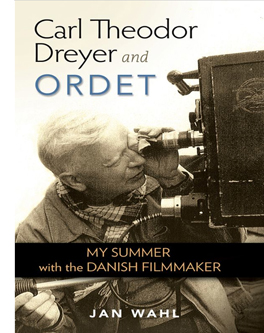

Before Jan Wahl became a prolific writer of children’s books, he left the US to study in Denmark. There he had the great fortune to be a dogsbody for Dreyer on the making of Ordet. Wahl left the country after the exterior shooting, but he kept in touch with Dreyer for some time afterward. His daily notes of their conversations were vetted and corrected by Dreyer, in hopes of eventual publication. Now, nearly sixty years later, the book has arrived.

Dreyer took a shine to the young Fulbright student and confided to him ideas about his earlier work and his plans for his Jesus film. Dreyer was at that point fairly undecided about many aspects of the Jesus script, including how to end the story. But these are sidelights compared to the central action of Wahl’s memoir, the making of Ordet in the cloudy and rainy summer of 1954.

Despite the inhospitable weather, Dreyer planned and shot much more action in exteriors than appeared in the final film. The film’s hermetic “theatricality” seems to have been arrived at through pruning landscape images and shots of characters coming and going. An especially intriguing shot of Anne and Anders meeting in a field took a great deal of time:

Despite the inhospitable weather, Dreyer planned and shot much more action in exteriors than appeared in the final film. The film’s hermetic “theatricality” seems to have been arrived at through pruning landscape images and shots of characters coming and going. An especially intriguing shot of Anne and Anders meeting in a field took a great deal of time:

Anne sets out to deliver a pair of trousers for her father, Peter Tailor, but she takes the long way around in order to have a tryst with Anders. The lovers meet in the field, lingering at a corner in the rye.

The camera had a long traveling movement, its tracks laid on a wooden platform in the shape of an immense letter L whose angle was parallel to the field. On that day, between three and five o’clock there was sufficient light for five takes. . . .

We’re also reminded of Dreyer’s fastidiousness—arranging sheep in ranks around the Borgen farmhouse and demanding that 1925 newspapers should line the drawers in the household. (Seeing a recent paper would “break the spell of concentration should an actor happen to see it.”) It’s a pity that Wahl could not stay through the whole production, which moved to the Palladium studio in the fall, to provide more details like this.

Just as ingratiating are Wahl’s accounts of the village where the film was shot, a tiny place taken over by Dreyer’s project. Wahl lingers over hearthside meals in a land where coffee has almost sacramental significance.

“There is something about coffee that soothes the Danes,” [Dreyer] said, “and puts them in touch with God. . . . On the winter days, which last so long here in Jutland, a warm cup is a balm; they take everyday communion in it.”

The primary value, I think, of Carl Theodor Dreyer and Ordet lies in atmospheric moments like these. I’ll always remember Wahl’s portrait of the gentle but obstinate Dreyer at sixty-five: dreaming of a film on Christ, smoking cigars, and tossing pastry crumbs to the bird that visits his garden every afternoon at three-thirty.

Pop quiz, hot shots:

What firm had the initial idea for VOD rentals? (Hint: Not Netflix.)

What firm had the initial idea for video kiosks? (Hint: Not Redbox.)

The answers, along with a solid story, can be found in Netflixed: The Epic Battle for America’s Eyeballs. Gina Keating’s brisk business reportage pits upstart Netflix against the well-entrenched Blockbuster in a cage match worthy of its title. Keating starts by demolishing Reed Hastings’s tale that he conjured up the service when he was annoyed by late fees on Apollo 13. In fact, tech entrepreneur Hastings entered the start-up as a fairly passive money guy, while the more retiring Marc Randolph devised the Netflix business model, which included what Keating calls an “intuitive user interface and peerless customer service.”

Keating shows how Randolph’s idea for an online video store on the Amazon model tapped into the expansion of internet retail. Randolph, according to Keating, “had what it took to conceive and launch Netflix. What came next—ruthless optimization and relentless growth—were not his strong suits.” By 2002, Randolph had left the company and Hastings ruled.

In counterpoint Keating chronicles Blockbuster’s ups and downs, mostly downs. It was already feeble when Netflix launched, and Viacom was perpetually trying to unload it. The decline was evident, however, in 2007 with the coming of CEO Jim Keyes, who had turned around 7-Eleven. Keyes decided to try to make Blockbuster outlets into “full-service entertainment destinations” where, according to Keating,

In counterpoint Keating chronicles Blockbuster’s ups and downs, mostly downs. It was already feeble when Netflix launched, and Viacom was perpetually trying to unload it. The decline was evident, however, in 2007 with the coming of CEO Jim Keyes, who had turned around 7-Eleven. Keyes decided to try to make Blockbuster outlets into “full-service entertainment destinations” where, according to Keating,

. . . customers would drop in for pizza and a Coke, or buy a book or a flat-screen television or hang out with their kids on weekends while waiting for a movie to download.

It was at this point that the Onion posted its YouTube video of the Living Blockbuster Museum. Still, Blockbuster should be credited with seeing the future of VOD. Execs tested it in 2001 (answer to Question One), but the concept had to wait until Internet access widened and download speeds picked up.

Netflix made missteps too. The firm let the staff who developed the video kiosk concept depart and form Redbox. (Answer to Question Two.) Hastings was also caught off-guard when Blockbuster Online began to surpass Netflix’s customer base. Still, you come away largely admiring the adroitness of the company. I hadn’t realized the power of Netflix’s software innovations, especially its recommendation engines.

Netflixed concentrates on major players, but Keating does introduce many economic-structural factors to provide higher context. And concentrating on personalities makes for a gripping read. Hastings, who declined to be interviewed for the book, is depicted as a math-mind who could inspire software engineers but who dealt coolly with human feelings in a way reminiscent of Steve Jobs. Carl Icahn, who stalks through many other histories of modern US media, has his moments too, mostly ones of fulmination.

Non-fun fact: A 2005 survey indicated that only 22% of Americans preferred to see a movie in a theatre rather than at home on video. And this was before the surge in VOD.

Netflix treated the Sundance Film Festival as a venue for dealmaking and PR. This is just one measure of the importance of such events for film as an art and a business. For decades our bookshelf devoted to film festivals harbored only a few volumes, mostly official histories of Cannes and Venice. By now, however, “festival studies” has become a teeming area of research. This is all to the good. International film culture after World War II, as we pointed out in Film History: An Introduction, has depended centrally on festivals, and film historians have to realize that these gatherings shape the history of cinema in many ways.

Netflix treated the Sundance Film Festival as a venue for dealmaking and PR. This is just one measure of the importance of such events for film as an art and a business. For decades our bookshelf devoted to film festivals harbored only a few volumes, mostly official histories of Cannes and Venice. By now, however, “festival studies” has become a teeming area of research. This is all to the good. International film culture after World War II, as we pointed out in Film History: An Introduction, has depended centrally on festivals, and film historians have to realize that these gatherings shape the history of cinema in many ways.

Jeffrey Ruoff’s new volume, Coming Soon to a Festival Near You: Programming Film Festivals, gathers several essays about the principles and pragmatics of deciding what’s shown. As Ruoff claims in his introduction, festivals perform many functions: they “celebrate film as an art, affirm different kinds of identity via film, [and] facilitate the marketing of films.”

Given these missions, the programmer functions minimally as a critic who aims to satisfy the audience’s tastes while steering it in novel directions. But the programmer can also be a celebrity in him- or herself, making the festival an extension of the programmer’s tastes, as happens with Michael Moore (Travers City), Roger Ebert (Ebertfest), and Tony Rayns’ Asian selections at Vancouver. This is what Ruoff calls the programmer as auteur.

The programmer is also a historian—reviving work from the past in retrospectives, while acting as a kind of future historian, laying down the conditions for later development in cinematic sensibility. The praise awarded to Bergman and Antonioni at 1950s and 1960s European festivals created a narrative of artistic development that historians who followed would elaborate.

Coming Soon to a Festival Near You offers a potpourri of pieces, from academically inflected accounts of festival history to personal memoirs from programmers and critics. Focus Features producer James Schamus provides a pungent entry on the economics of red-carpet galas, and Bill Pence, a long-standing fest entrepreneur, recounts the development of Telluride. All in all, Ruoff’s volume helps us understand the role of festivals as tastemakers and gatekeepers of world cinema.

“It is a country, culturally speaking, that respects its avant-garde filmmakers, present, past, and future,” writes Adrian Martin. He’s describing Austria, from which comes the magnificent volume Film Unframed: A History of Austrian Avant-Garde Cinema. Peter Tscherkassky, a major filmmaker himself, has created a collection that manages to be at once sweeping and in-depth. Many of us (but not enough) know work of the “old” masters Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren, but this anthology skips back to the early 1950s. There we find artists like Kurt Steinwendner, whose Der Rabe (The Raven, 1951) looks to be a stark exercise in neo-Expressionism, done to electronic music.

“It is a country, culturally speaking, that respects its avant-garde filmmakers, present, past, and future,” writes Adrian Martin. He’s describing Austria, from which comes the magnificent volume Film Unframed: A History of Austrian Avant-Garde Cinema. Peter Tscherkassky, a major filmmaker himself, has created a collection that manages to be at once sweeping and in-depth. Many of us (but not enough) know work of the “old” masters Peter Kubelka and Kurt Kren, but this anthology skips back to the early 1950s. There we find artists like Kurt Steinwendner, whose Der Rabe (The Raven, 1951) looks to be a stark exercise in neo-Expressionism, done to electronic music.

As the chapters move toward the present, some names and films were familiar to me, most were not, but all emerged as intriguing and provocative. The diverse directions of experimentation are traced by some of our best writers (Maureen Turim, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Steve Anker, Andréa Picard, and Christoph Huber, among others). The hefty volume is filled out with color photographs and many pages of -graphies: bio-, filmo-, and biblio-.

Martin’s foreword, from which my initial quotation comes, sets the stage for a comprehensive reappraisal of this major tradition. We have to thank the film collective sixpackfilm and the Austrian Film Museum, which has become a leader in publishing books and DVD editions that mightily expand our horizons. Thanks also to the government subsidies that allow the book to be available at a very decent price. Next up, one hopes: A big fat DVD compilation.

In the fall of 1988 there materialized at my office an elvish man with a neat white beard and a Compaq laptop. He was perpetually smiling, and he soon revealed why: he had one of the quickest wits and sharpest senses of humor I’d encountered. The Lilly Endowment had awarded him a year’s grant to improve his knowledge of film. Very sensibly, he came to UW.

The faculty all welcomed him, and he became friends with Kristin and me. Tapping away quietly on his laptop, sitting on the far side of the front row (to keep plugged in), he took the most extensive and precise notes on my blahblah that I have ever seen. Recalling those days, I have to smile when I realize that the oldest person in the class was the only one who brought a computer. His notes circulated in samizdat among the grads for years.

His name was Peter Parshall. A film fan from his youth, Pete had taught film and literature at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. He became famous as a beloved, highly demanding teacher: the student slogan was “Peter Parshall picked apart my perfect paper.” After his year in Madison, Pete went on a Fulbright Award to teach American film at the Technical University of Dresden. He retired from Rose-Hulman some years ago but kept active (bicycling, especially) and still teaches film courses.

His name was Peter Parshall. A film fan from his youth, Pete had taught film and literature at Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology. He became famous as a beloved, highly demanding teacher: the student slogan was “Peter Parshall picked apart my perfect paper.” After his year in Madison, Pete went on a Fulbright Award to teach American film at the Technical University of Dresden. He retired from Rose-Hulman some years ago but kept active (bicycling, especially) and still teaches film courses.

Now Pete has published a probing book on a broad storytelling strategy that goes by many names—thread structure, hyperlinked plots, network narratives. Altman and After: Multiple Narratives in Film provides incisive analyses of several films, while also offering an illuminating set of categories for understanding them. Nashville is a “mosaic narrative,” an effort to surrender forward-driving plot in favor of fragments that pull the characters into teasingly incomplete patterns. Network narratives, with intersecting and culminating plotlines, are exemplified by Pulp Fiction, Amores Perros, Code Unknown, and The Edge of Heaven.

A new and intriguing category is the “database narrative.” Here the film launches a set of events but then replays them differently, providing alternative pathways for events. Sometimes this strategy is motivated as reflecting different points of view, as in Rashomon. But other tales question the very solidity of the narrative world, as in The Virgin Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Run Lola Run, and The Double Life of Véronique.

Pete’s book has already received praise, with Sarah Kozloff noting in Choice: “For several of these films, Parshall’s discussion is the best analysis available, and teachers and students have much to learn from his searching intelligence.” Altman and After is a fine addition to the growing list of books seeking to understand the permutations of today’s cinematic storytelling.

Torkell Saætervadet, a Norwegian expert on film technology and cinema design (and on aviation!), won our thanks with his authoritative 2005 text The Advanced Projection Manual. Now the International Federation of Film Archives, which co-sponsored the earlier volume, has brought out his new FIAF Digital Projection Guide.

Torkell Saætervadet, a Norwegian expert on film technology and cinema design (and on aviation!), won our thanks with his authoritative 2005 text The Advanced Projection Manual. Now the International Federation of Film Archives, which co-sponsored the earlier volume, has brought out his new FIAF Digital Projection Guide.

It’s a comprehensive overview, written with great lucidity and packed with charts and specs. Sætervadet covers the Digital Cinema Package file system, projection systems, 3-D systems, sound formats, and best practices for projectionists, including advice on preparing one’s own DCP hard drive. Along with judicious presentation of rival formats, Sætervadet provides informed opinions, including a persuasive account of why 4K projection is much to be preferred to 2K. As an inveterate sitter in the Raccoon Lodge, I was happy to learn of the importance of the “front-row rule” in measuring resolution in relation to screen size.

This is an indispensable book for anyone interested in current cinema technology. I wish it had been available when I wrote Pandora’s Digital Box. The Guide is available direct from FIAF and from Amazon.uk.

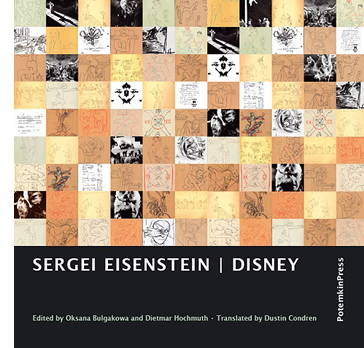

Finally, from the enterprising Potemkin Press comes a new edition of Eisenstein’s writings on Disney animation. An inveterate cartoonist himself, usually somewhere between Cocteau and Keith Haring, the polymath director reflected on Uncle Walt the artist throughout his career, but most deeply while he was at work on Ivan the Terrible. SME made no bones about it:

The work of this master is the greatest contribution of the American people to art–the greatest contribution of the Americans to world culture.

As often happens, Disney furnishes Eisenstein the occasion to launch a fantasia on what he’s been reading and thinking about since the last time he wrote. He hits on the ceaseless, “amoeba-like” change that animation permits and that Disney cartoons exploit. SME’s ruminations lead him into myth, ritual, medieval art, the drawings of Thurber and Steinberg, and much more. Typical is this:

TUSHMAKER’S TOOTHPULLER by John Phoenix, of course, stands in line with other plasmatic fancies. (Never observed this before.) Now I’ve just read some verses on the same topic by Walter de la Mare….

Much of the material is irreducibly private and may never be fully understood. Feel free to unleash your own associations on passages like this:

Octopi: Most plasmatic.

Merbabies.

The tiger is a goldfish.

↓

Lawrence.

↓

Horses like butterflies.

St. Mawr like a fish.

Back in 1986, Jay Leyda and Alan Upchurch gave us Eisenstein on Disney, a fine selection from these energetic, perplexing jottings. Unfortunately that book is currently rare and expensive. Now we have Sergei Eisenstein: Disney, edited by Oksana Bulgakowa and Dietmar Hochmuth. Based on recent archival discoveries, it incorporates more pieces and includes a more extensive commentary and an index. Dustin Condren’s translation reads fluently, and there are many illustrations. The editors employ varying fonts to label passages in different languages, although all passages, including SME’s obsessive cut-and-pastes from books, are fully rendered in English.

Oksana’s Afterword provides a historical account of the manuscript and an in-depth guide to the development of SME’s ideas at the period. She’s particularly helpful in explaining Eisenstein’s flirtation with psychoanalytical ideas. She flavors her account by itemizing the archaeological artifacts the researcher encounters:

Eisenstein writes on an incredible variety of paper–on the back of his own manuscripts and others’ screenplays, on Mosfilm’s or the film committee’s stationery, on concert programs. The annotations from the year 1944 are scribbled on 1942 calendar sheets. Call numbers for books from the library, telephone numbers, doctors’ prescribed diets, and a grocery list are all found in the text–cream meringues, sultanas, nuts.

When I learn things like this, I like him even more.

Sergei Eisenstein: Disney is a remarkable addition to the Eisenstein literature and ought to provoke lively debate in the animation community as well. But try to find or photocopy the Leyda/Upchurch volume too. It includes SME’s earlier 1932 notes on his drawings, where he floats his ideas about “plasmation,” and it has some different illustrations and its own helpful commentary. Both collections are invaluable to every Eisensteinian, which in a just and righteous world should mean everybody.

P.S. 28 January 2013: Thanks to Manfred Polak for correcting a misspelled name.

Thanks also to Peter Parshall for corrections in my memory of his visit (Compaq, not Apple as I’d said; Lilly grant; 1988; all duly adjusted above.) Details, details. He adds:

You probably don’t remember but the other students complained to you after the first day’s class because of the noise my computer keys made as I clattered away, trying desperately to keep up with the barrage of information coming at me. So when I came up to speak to you in my turn, you suggested that perhaps I shouldn’t use the computer. I was stunned! (All that money! That was one of the very first laptop models manufactured and it had cost a bundle!) The next day, instead of sitting in the back, I sat in the front row so that your voice would drown out my clatter and I announced at the class break that I’d put my notes on reserve. The complaints suddenly stopped.

Then on the first day of spring term, I was startled when a student rushed up to me and asked very anxiously what had happened to my notes!!! (I had taken them off reserve after exams were over, thinking they would no longer be needed.) No, No, he exclaimed. All the students wanted copies for prelims. So I put them back on reserve.

The climax to the joke came three or four years later when I flew into Rochester, NY, for a film conference and taxi-pooled with several other conferees to the hotel. I was delighted to learn that they were all grad students from UW, although I didn’t know any of them. I didn’t mention my name, it being of no scholarly importance, but simply said I taught in Indiana and had spent a sabbatical year at UW. A female voice with a rich British accent popped up from the back seat: “Oh, you’re Peetah Paahshall.” Turns out she had acquired a set of the samizdat. I chuckled at the thought of them still being handed on, from one generation of students to the next. . . . I know I learned a ton that year in Madison and if I could help the learning process for some UW students in return for all your hospitality, I was happy to do so.

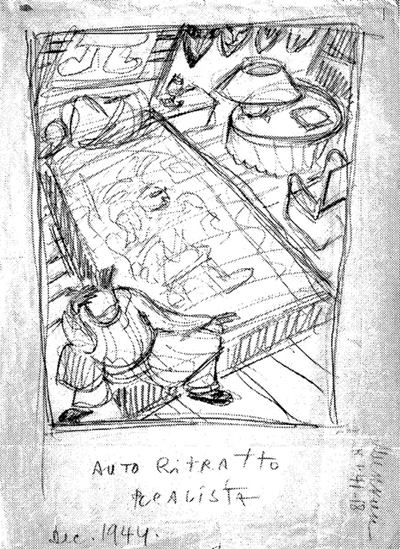

Eisenstein, Self-Portrait (1944).

Got those death-of-film/movies/cinema blues?

Night Across the Street (2011).

DB here:

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

These squibs seemed especially damp this time around because while these guys were knocking Hollywood and/or art movies I was enjoying the Vancouver International Film Festival. If you’re willing to watch mainstream entertainments from outside Hollywood, or films that aren’t the bland arthouse fare full of stately homes and British accents, or even films that don’t chop every scene to splintery images, Dr. Bordwell has a cure in mind for you.

Had you been looking for breezy or outlandish entertainment, for example, the Dragons and Tigers wing didn’t disappoint. Helpless, from South Korea, is a thriller built around identity theft. I thought it was clumsily plotted, but it sustains curiousity through the apparently bottomless series of discoveries a man makes about his missing fiancée. Jeff Lau’s East Meets West is a Hong Kong farrago of rapid-fire gags, weird haircuts, references to old Cantopop, and nonchalantly wacko storytelling. Granted, the central idea of making the Eight Immortals of legend into modern superheroes (and one supervillain) is smothered by Scott Pilgrim-style SPFX. Still, I will watch Karen Mok Man-wai and Kenny Bee in anything, albeit for different reasons. Closer to mainstream Hollywood tastes was Nameless Gangster, in which a restless flashback structure traces the rise of a flabby brute from customs agent to top drug smuggler. Yoon Jongbin’s slickly-made film ends with an abruptness that recalls the conclusion of The Sopranos.

Of all the pop-entertainment movies I saw at VIFF, the audience favorite was doubtless Key of Life, a nifty Japanese crime comedy. An amnesiac hitman and a shambolic slacker swap identities in a cunning series of coincidences that brings on some satisfyingly menacing underworld types. Intersecting the men’s misadventures is a hyperorganized OL, or office lady, who determines to find herself a husband within a month. Everything sorts itself out, of course, with one nice wrapup saved for the middle of the closing credits. This is the kind of Japanese diversion I’ve recorded a liking for earlier (Uchoten Hotel and Happy Flight). Hampered by a wretched title, Key of Life probably won’t get US theatrical distribution, although it may make some headway on VOD. Aussie movie maven Geoff Gardner and I agreed that if we had the money, we’d buy the remake rights.

Everything new is old (again)

Tabu (2012).

Form is the new content, they say. (Too simple, but some do say it.) No surprise, then, that part of what appeals in contemporary cinema is its overt reworking of previous styles. Neo-noir is perhaps the most common current example, but ingratiating retro-stylings were on display in more rarefied forms at VIFF.

Part of the appeal is the rediscovery of the glory of the 4:3 aspect ratio. Kristin has already talked about how Pablo Larrain’s No appropriates a seedy U-matic look to tell its tale of 1970s Chilean politics. A similar pastiche effect emerged from Mine Goichi’s All Day, a short that used even grubbier video to parody Japanese family dramas. May we expect to see more VHS-looking movies? I wouldn’t mind.

Silent cinema pastiches are usually lame, as witness The Artist, which scrambles history and treats old films as oddly soft-minded. (No Hollywood drama of the late 1920s would have been built around a protagonist so feeble he tries to commit suicide twice.) Jean Dujardin, and contemporary audiences that adore his film, should catch up with Hayashi Kaizo’s To Sleep As If to Dream (1986), in which the contemporary story is played as a silent film and the rediscovered (fake) old film is accompanied by benshi commentary and music. The “forged” footage in Forgotten Silver also shows how good filmmakers can create convincing, pleasantly anachronistic imagery.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

At VIFF, another D & T short, Yun Kinam’s black-and-white Metamorphosis (right) tried to replicate the look of silent cinema. While a family crowds around a deathbed, we get disruptive editing, aggressive depth, and even static flashes (those vein-like seepages into the image caused in old films by cold temperatures). As a retro exercise, Metamorphosis is better-informed and more evocative than what we get in The Artist. Suggestions of Maya Deren and Menilmontant gives these images the aura of having been exhumed from the archive.

More celebrated since its Berlin triumph (two awards) is another 4:3 exercise, Miguel Gomes’ Tabu. A vaguely 1920s prologue shows a brooding tropical explorer who has seen his ex-wife as a ghost. Then Part 1 (“Lost Paradise”) takes us to stately black and white imagery of contemporary Lisbon. It’s late in December, and Pilar is concerned about her elderly neighbor Aurora. The old woman is taken to a hospital and asks Pilar to find Aurora’s old lover, Ventura. By the time Pilar discovers him, it’s too late. After Aurora’s funeral, Ventura starts to explain how they met in Africa. Here starts Part II (“Paradise”).

Now the film becomes hypnotic. In Africa, Aurora is married to a sturdy, good-natured colonist, and she can hunt and shoot with the best of them. Ventura and his friend Mario, who’s becoming a pop crooner, are taken into the household. He and Aurora begin a torrid affair. Part II is rendered without onscreen dialogue, but not in exact mimicry of silent cinema. There is piano music, it’s true, and much of the action is carried by letters, as in a lot of silent movies. But there are no intertitles; instead, all the action is played out with the support of Ventura’s voice-over, occasionally supplemented by the young Aurora reciting letters she wrote. Moreover, Mario’s band and his singing are rendered in full lip-synch. More eerily, as Ventura explains the rise and collapse of the love affair, we get highly selective bits of noise—not everything audible in a scene, but perhaps the tinkle of glasses or a faint wind. These become the aural equivalent of glimpses.

“Paradise” gives us silent cinema not replicated, but refracted through memory and romantic longing. In a film paying homage to Murnau (a forbidden romance as in Tabu, the name Aurora recalling Sunrise), Gomes has apparently also sought to give us something like the “part-talkies” of 1928-1929. Those films had full-blown dialogue scenes (as in Part I) and other scenes containing only music and effects (Part II), relieved by synchronized musical numbers (a sequence showing Mario’s band performing by the pool). Tabu recovers something of the strangeness of those transitional films, notably Sunrise itself, while remaining highly contemporary. It knows that we can turn to tradition when we want to rekindle a romanticism that would look high-flown today.

Long live the long take

Beyond the Hills (2012).

At about 16 seconds per shot, Tabu has the same cutting rhythm as some early talkies, like The Black Watch and Hearts in Dixie. Today, as we’ve seen, the long take is increasingly the province of movies that play chiefly at festivals. All other things being equal, a movie with around 1200 shots, like the very popular Danish import The Hunt, will be an easier sell on the arthouse circuit than, say, Beyond the Hills, with only about 110 shots in 148 minutes. It’s a pity. Although The Hunt is a solidly crafted drama in the Nordic enemy-of-the-people tradition, it moves rather predictably across the combustible subject of false accusations of child molestation. Beyond the Hills, by Cristian Mungiu, director of Four Months, Three Weeks, and Two Days, is more enigmatic and demanding.

Voichita is a nun in a rural Orthodox enclave in Romania. She’s visited by her friend Alina. The two grew up as best friends in an orphanage, but Alina went to Germany to work, and now she insists that they must run off together. Voichita resists. Alina claims that Voichita once agreed to this plan. Has the young nun changed her mind and committed to the church? Or is Alina’s plan an idée fixe that Voichita has simply humored, without ever intending to join her? Were they perhaps lovers? Alina’s endless staring at Voichita and her lunges at suicide suggest deep passions at stake.

The refusal to supply full exposition makes characterization enticingly uncertain. Voichita’s wide-eyed sympathy for her friend can be seen as both pliable and stubborn, while Alina’s nearly wordless reprimands imply that Voichita has betrayed her. But perhaps Alina is just asking too much, or Voichita is being too unbending. The couple’s drama is played out against the stringent background of a female community ruled by a priest. Alina is incorrigible, not responding to the gestures of salvation extended to her, and agreeing, stone-faced, that she has committed every sin on a list of over 400. Eventually the pious souls decide that Alina is possessed, and her demons must be exorcised. In a simple gesture of solidarity, Voichita declares something like love for Alina, but too late.

Alternating discreet handheld takes with fixed shots staged in depth, making no concessions to impatience or easy responses, Beyond the Hills recalls the sobriety of Dreyer’s Day of Wrath and Bresson’s Les anges du péché. It plays out in a rougher-textured, muddier world, but it’s no less concerned with the dynamics of compassion and cruelty, dogmatism and eroticism. In each, a woman is ready to sacrifice herself for love. As Romania’s Oscar submission, Mungiu’s film deserves to find an audience in the US.

Long takes were also a specialty of the late Raúl Ruiz, whose penultimate film, Mysteries of Lisbon, won him probably the widest audience of his career. That film displayed his fascination with proliferating stories, but its adherence to a single plane of reality was exceptional in the career of a fabulist who enjoyed confounding all types of realism. In that regard, Night across the Street, his last fully completed work, is more characteristic.

An old office worker is about to retire and is convinced that someone is coming to kill him. While Don Celso awaits his assassin, he fraternizes with his co-workers, with schoolteacher and author Jean Giono, and with others in the hotel where he resides. He also recalls his childhood, when he talked to Long John Silver and went to movies with Beethoven. Eventually the plot shifts levels of reality even more radically, as one séance blends into another, characters shot down in a massacre return to life, and eventually Celso takes credit for inventing the people around him.

Mungiu’s handheld shots have no place here. As in Mysteries of Lisbon and his Proust film, Time Regained, the camera glides through this world with velvety assurance. Sometimes the characters do too, as they seem to ride the dolly or saunter in front of a blatantly unreal backdrop. Ruiz subverts academic cinema by using its well-upholstered technique, but he also mines film history. He revisits tableau staging in the shrewdly split set of Don Celso’s office, and he continues to exploit his more-Wellesian-than-Welles big-foreground technique.

Above all, the boy’s trip to the movies, in an awkwardly tilted image in which the usher usually blocks the screen, pays typically skewed homage to the medium’s enchantment. The mock film of Ruiz’s Life Is a Dream has given way to The Foxes of Harrow, the Hollywood cinema of Ruiz’s childhood.

Land, sea, and sky

small roads (2012).

When one thinks of the long take, James Benning comes quickly to mind, and small roads is true to form—in more ways than one. Forty-seven fixed shots in 102 minutes take us from the Far West to the South and to the Midwest before shifting westward again. The roads are indeed small, far from superhighways and traffic circles. As usual, landscape is the protagonist and slight shifts in image or sound arrest our attention. There are plenty of perceptual teasers. When a distant truck descends the distant sloping road above, it vanishes. Will it re-emerge in the nearer road? At another point, we wonder when, or if a car we hear will appear in the frame.

Hogarth spoke of art that leads the eye “on a wanton kind of chase,” and Benning’s roads—almost never seen from dead center, so we’re not given central perspective—carve oblique or sinuous paths into fields, plains, deserts, and forests. Road signs reenact the curve of the roadway, with carets and squiggles providing spare geometric “readings” of the piled-up surfaces of color and mass. There’s also some synesthesia. In one shot, I thought I heard mist rolling in. The topographies are real but through Benning’s strict scrutiny they become as fantastical as Ruiz’s dreamscapes.

That’s why I suspect that roads aren’t the real subject of the film. They serve as a pretext for Benning’s recurring interests in how wind curls clouds and makes branches tremble, how light outlines trees, how shapes like squat black oil derricks and the textures of fat snowflakes and soggy leaves can command the frame. Now that Benning has moved to digital filming, he has discreetly inserted some CGI. I couldn’t spot any, though one partial moon in daylight looks suspicious to me. No matter. Painterly beauty, along with a certain placid mystery, is enough for any movie nowadays.

At the other extreme lies the bustle of Leviathan, a poetic, quasi-abstract documentary by Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel. The filmmakers capture a New Bedford fishing trip through GoPro digital mini-cameras worn by fishermen, tossed into a netful of fish, or dragged through the water. Long takes abound here too, but it’s hard to say how many. As in The Man with a Movie Camera, the very boundary between one shot and another is put into question. So is the boundary between us and the space onscreen, as we’re weirdly wrapped in the extreme wide-angle yielded by this lens.

This is what you get when no human eye is looking through the camera. Often, in fact, nobody could look through the lens. No head, let alone human body, could occupy the space of some of these shots. Chains roll out past us from churning greenish darkness, while fish drift and slither on all sides. We’re right next to a gull trying to use its beak to lift itself to another area of the hold. Here the fish-eye lens lives up to its name. The camera bobs in a tank as fish are tossed in and spin aimlessly past. Coasting along the edge of the craft, we dip abruptly in and out of the heaving water, our plunge accentuated by brutal sound cuts. We chase starfish and ride waves, spinning up to watch gulls blotting out the sky. Accelerations of speed (again, Man with a Movie Camera comes to mind) render the action hallucinatory, especially since the shutter can capture foam with strobe-like precision.

One result is a disembodied, dehumanized vision of sea and sky: The camera as flotsam. But we also get bumpy, skittish visions of human labor definitely tied to bodies that harvest the ocean. Work activities are filmed from cameras lashed to the fishermen’s heads or lying on the deck among scallops to be shucked. Most documentary close-ups of artisans’ tasks are taken from far back and with long lenses; here the very wide-angle GoPro lenses not only show tasks from the inside, but their distortions exaggerate each gesture, sometimes heroically, sometimes grotesquely. Either way, human activity has been defamiliarized no less than undersea life.

We start the movie immersed in a welter of details and stay enmeshed for nearly an hour. Only then do we get an “establishing shot” showing the boat deck and mapping the overall process of filling and emptying the nets. And fairly soon after that, as if to parody the usual documentary about fisher folk, we get a four-minute shot of the captain dozing off while watching a TV show (apparently The Deadliest Catch). Leviathan ends with a sequence that brackets the chiaroscuro of the opening, but we no longer see a clam’s-eye-view of being snagged. Instead, we get barely illuminated darkness with whiffs of crimson teasingly darting to the edge of the frame, as if to signal the end, before swerving back to the center, then heading offscreen. Again, Ruiz has the line: Special shadows that give off light.

Ready to declare cinema dead? There is a cure for your malaise. We call it a film festival.

More of my thoughts on Ruiz can be found here and here. His widow Valeria Sarmiento completed his very last project, The Lines of Wellington.

On small roads and digital manipulation, see Michal Oleszczyk’s discussion at Slant and Robert Koehler’s informative review in Variety. In correspondence Benning confirms:

Yes, lots of compositing, but no speed changing, although the border cops are going around 100 mph. . . . Shot 26 has a sky that was filmed the next day about 100 miles away. And yes the moon was out, but that shot is pointing north so I filmed the moon in the southern sky during the day, and put it into the northern sky. All the compositing was done with shots I made; always somewhere nearby. (100 miles is nearby when you circle 2/3 of the US.)

You can learn more about Leviathan from Dennis Lim’s article on the filmmakers in the New York Times. The New York Film Festival provides a lengthy Q & A on its website. See also Phil Coldiron’s “Blood and Thunder: Enter the Leviathan“ in the latest Cinema Scope, with some superb frame enlargements. Above all, don’t miss the extract on vimeo, which gives you a good sample of the splendor of this film.

Leviathan (2012).

ADD = Analog, digital, dreaming

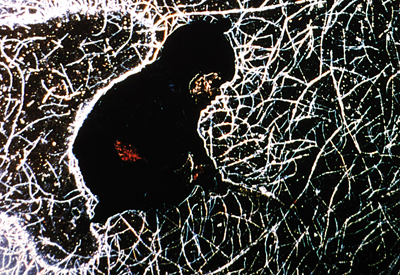

Luther Price, Sorry Horns (handmade glass slide, 2012).

DB here, just back from the Toronto International Film Festival:

It’s commonly said that any substantial-sized film festival is really many festivals. Each viewer carves her way through a large mass of movies, and often no two viewers see any of the same films. But things scale up dramatically when you get to the big boys: Berlin, Cannes, Venice, and Toronto. I’ve never been to the first three, but my first visit to TIFF was like wading into pounding surf and letting the current carry me off.

This is the combinatorial explosion of film festivals: A hefty 450-page catalog listing over 300 films from 60 countries. Moreover, because it’s both an audience festival and an industry festival where movies are bought, sold, and launched, you observe a range of viewing strategies. Although I sit too close to be much bothered, my friends tell me of mavens darting in and out of shows or checking their cellphones during slow stretches of what’s onscreen. The crowds add to the air of electric excitement, as of course do the visits of glamorous celebs.

So I was inundated. How to choose what to see in 3 ½ days for viewing? (I reserved time for industry panels.) I knew that some of the prime titles, such as Kiarostami’s Like Someone in Love or the remarkable-looking Leviathan, would be available for Kristin and me at Vancouver later in the month. And I saw no reason to stand in queues for Looper, Argo, and other movies that I could see in empty Madison, Wisconsin multiplexes during off-peak hours.

I still missed many, many things I wanted to catch. For much wider assessment of major movies, you should go to the coverage offered by the tireless scouts of Cinema Scope and the no less tireless scouts of MUBI. Here I’ll talk just about a few films that made me think about—no surprise—digital vs. analog moviemaking.

Fragments and figments

Mekong Hotel.

Stephen Tung Wai’s Tai Chi 0 (0 as in zero) represents everything we think of when we say that digital production and postproduction have transformed cinema. This kung-fu fantasy from the Chinese mainland (but using Hong Kong talent, including the director) retrofits the genre for the video-game generation. CGI rules. The result is, predictably, monstrous fantasy—a globular iron behemoth, a sort of Steampunk locomotive version of the Death Star—but also screens within screens, GPS swoops, tagged images, Pop-Up bubbles identifying the cast, and other scribbling that turns the movie screen into a multi-windowed computer monitor. One more thing Scott Pilgrim must answer for.

Jang Sun-woo played with similar possibilities in his 2002 Resurrection of the Little Match Girl, inserting character dossiers and creating digital effects mimicking gamescapes. But he sometimes paused to give these images a dreamlike langor. Tai Chi 0 never lingers on anything and instead carries the level of busyness to crazier heights. In a panel at the Asian Film Summit, Fung explained that one scene of the film was inspired by a particular online game. Sammo Hung was playing Fruit Ninja or something similar and Fung decided to include a scene of villagers turning away invading soldiers with a barrage of produce.

Fung said as well that fantasy martial arts remains a blockbuster genre in the PRC (viz. the success of Painted Skin: The Resurrection). Tai Chi 0 ends on a cliff-hanger, the end titles (rolled too fast to read) provide a trailer for part 2, and apparently a third part is in the works. Now China has franchise fever.

The stop-and-start plot is familiar from Hong Kong films of the 70s onward (including over-made-up gwailo villains), but its execution wrecks nearly everything I like about classic kung-fu movies. Clearly though, I’m not in the audience the movie is aimed at. My friend Li Cheuk-to, artistic director of the Hong Kong International Festival, opined that this digital froth could be very appealing to China’s online generation.

Tai Chi 0 exemplifies what academics writing on digital have talked about as the “loss of the real.” As Tom Gunning pointed out back in 2004, though, things aren’t so simple. Digital photography, after all, remains photography. The lens intercepts a sheaf of light rays and fastens their array on a medium. The fact that a shot can be reworked in postproduction doesn’t mean that every digital image must surrender the tangible things of this world.

At TIFF, the power of digital cinema to bear witness was on display in Sion Sono’s Land of Hope. Sono has already documented Japan’s 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Himizu, which I haven’t seen, but in that and Land of Hope, he abandons the wacko bad taste that made Love Exposure and Cold Fish so memorable. This is a sober, traditional drama presented with straightforward economy. It takes place in a fictitious district, Nagashima, but the fact that the name combines “Nagasaki” and “Hiroshima” suggests the gravity of Sono’s approach.

Three couples’ lives are torn apart by the quake, the tsunami, and the collapse of the nearby nuclear power plant. (All of these catastrophes are kept offscreen, glimpsed in TV reportage.) The oldest couple refuses to evacuate, clinging to their farm. Their son and his wife move to a nearby city where they succumb to the fear of radiation affecting their unborn child. And an unmarried couple wander the ruins looking for the girl’s father.

Sono intercuts the three lines of action. The old farmer adroitly manages his wife’s dementia and lets her indulge her fantasy of dancing in a village festival. In a critique of Japanese conformity, the young couple is shown being mocked for their worries about radiation poisoning. (The wife seals their apartment and, in a touch recalling the grotesque side of Sono, takes to wearing a Hazmat suit.) Less sharply developed are the fairly aimless ramblings of the youngest couple, though Sono injects some suspense when they dodge police blockades. At intervals, plaintive Mahler (a Sono weakness) surges up to underscore the futility of their search.

Throughout, government reassurances and the media’s insistence on putting on a happy face are treated with robust skepticism. Instead, Sono celebrates a dogged persistence to get through each day. The young couple’s mantra of “one step, one step” supplies the upbeat tone of the last scenes. As affecting as you’d expect is the footage of areas around the plant, seen as a wintry wasteland. Like Rossellini filming in bombed Berlin in Germany Year Zero, Sono has shot precious footage of ruins that testify to a calamity in which nature conspired with human blunders. And he did it digitally.

You can’t expect something so conventionally dramatic from Apichatpang Weerasethakul, and Mekong Hotel doesn’t supply it. It’s as relaxed as Tai Chi 0 is frenetic, and its central conceit makes it another pendant to Uncle Boonmee. The boy Tong and the girl Phon meet from time to time on the terrace of the hotel overlooking the river. They talk about folk traditions and the flood then besieging Thailand. They also encounter spirits that are as tangible, even mundane as they are; Phon’s dead mother appears in her room occasionally knitting. More shocking are the ghosts called Pobs who seem to possess the characters and make them hunch over and gobble intestines, sometimes in situations that suggest the organs have been torn from another character. All these scenes are handled with the usual Weerasethakul tact: long-take long shots, usually one per scene, that push the everyday and the extraordinary to the same unruffled level.

Mekong Hotel seems to operate on two planes of time. On the image track and in the dialogue, we witness Tong and Phon on the terrace or walking along the river. But the music, snatches of repetitive guitar tunes, seems to come from another time frame. At the start we see a guitarist practicing, and his noodlings run almost constantly under the drama we see. Another motif, fixed and lustrous shots of the Mekong River, yields a visual if not dramatic climax: a slowly paced choreography of Jet-skis crisscrossing the water. Here the digital medium may work to Weerasethakul’s advantage, with the clouds and landscape hanging unmoving over the racing watercraft, as a single, slow ship wades into the middle of their oscillating geometry.

The analog alternative

I suspect that Olivier Assayas filmed Something in the Air (originally Après Mai) on film, but even if he didn’t, the movie is a tribute to analog reproduction–mimeograph machines, LPs and turntables, and cinema in its different guises, from exploitation films to agitprop and experimental lyrics. We all know that the 1960s continued well into the 1970s, and here Assayas shows the uneasy carryover with a mixture of sympathy and critical detachment. The film starts with our high-school protagonist Gilles carving a peace symbol into his desk, flagrantly ignoring the teacher’s lecture. The shot encapsulates the film’s tension between political activism and image-making, and Gilles will oscillate between them in the course of the plot.

The poles come to be represented by two young women—the wealthy and ethereal Laure for whom he makes his paintings and the more hardheaded leftist rebel Christine, who goes out with him and others on nightly graffiti raids. When Laure leaves for London, Gilles continues his painting while leafleting and splashing slogans on walls, with the occasional Molotov cocktail to spice things up. The copains’ rebellion leads to some harm, but they cling to their ideals.

The poles come to be represented by two young women—the wealthy and ethereal Laure for whom he makes his paintings and the more hardheaded leftist rebel Christine, who goes out with him and others on nightly graffiti raids. When Laure leaves for London, Gilles continues his painting while leafleting and splashing slogans on walls, with the occasional Molotov cocktail to spice things up. The copains’ rebellion leads to some harm, but they cling to their ideals.

When summer comes, Gilles joins a film collective headed to document workers’ struggles in Italy. He encounters the arguments that made me smile in nostalgia: Shouldn’t revolutionary content have a revolutionary form? But how shall we reach the working class if our films are opaque? Assayas, who grew in this period and was repelled by the Maoist dogmatism of Cahiers du cinéma and Cinéthique, evokes these debates to remind us that the counterculture was about art and political change at one and the same time. Something in the Air chronicles a few years when imagination mattered.

After an early, shocking clash of students pounded down in a police riot, the film adopts a more circumspect rhythm, salting its scenes with books, magazines, record albums, and songs of the time. The plot keeps our interest by delaying exposition about the characters’ family lives until rather late. When we learn that Gilles’ father writes scripts for the celebrated Maigret TV series, we’re invited to see his forays into abstract painting as his form of teen rebellion. The plot doesn’t mind straying a bit from Gilles, as when his friend Alain, another aspiring artist, gets caught up in the fervor and pursues a wispy red-haired American dancer.

Characters meet, work or play together, drift apart, re-converge, and eventually settle into something like grown-up life. But at the end, when Gilles has apparently been absorbed into commercial filmmaking in London, he is granted one last vision of one of his Muses, who reaches out for him from the screen of the Electric Cinema.

Analog triumphs as well in The Master. Sitting in the front row of Screen 1 at the TIFF Lightbox (see below), I was astonished at the 70mm image before me. Not a scratch, not a speck of dust, not a streak of chemicals, and no grain. So did it have that cold, gleaming purity that digital is supposed to buy us? Not to my eye. The opening shot of a boat’s wake, which will pop up elsewhere in the movie, was of a sonorous blue and creamy white that seemed utterly filmic. Now we know the way to make movies look fabulous: Shoot them on 65.

The Master, as everybody now knows, centers on Freddie Quell, an explosive WWII vet, and his absoption into a spiritual cult run by the flamboyant Lancaster Dodd. Followers of The Cause are encouraged, through gentle but mind-numbingly repetitious exercises, to probe their minds and reveal their pasts. With the air of a charming rogue in the young Orson Welles mold, Dodd seems the soul of sympathy. But like Freddie he’s capable of bursts of rage, especially when his methods are questioned. Freddie becomes a sidekick because of Dodd’s fondness for his moonshine, while he also serves as a test case for the efficacity of The Cause’s “processing” therapies. If you can get this hard-bitten, borderline-sociopath in touch with his spiritual side, you can help, or fleece, anybody.

Like There Will Be Blood, this movie is primarily a character study. That film gained plot propulsion from Daniel Plainview’s oil projects, but many situations worked primarily to reveal facets of his dazzling self-presentation, his repertoire of strategies for dominating others. Something similar happens with Dodd and the ways he charms his congregation. But here the action is more episodic and the point-of-view attachment is dispersed across two characters. Dodd’s counterbalancing figure, the clenched Freddie, is so difficult to grasp psychologically (at least for me) that the film didn’t seem to build to the sort of dramatic, even grotesque peaks we find in other Anderson projects.

This is also a story about an institution, a quasi-church with a pecking order, rules, and roles. I wanted to know more about how The Cause worked, how it recruited people, and how it garnered money. Laura Dern plays a wealthy patron who lets the group stay in her home, and at one point Dodd is arrested for embezzling from the foundation, but the details of his crime aren’t explained. I also wanted to know more about the group’s doctrine, which seems so vague that Scientology need not worry about being targeted. The rapid-fire catechisms between Dodd and his acolytes are gripping enough, as Q & A dialogue usually is, but what system of beliefs lies behind them? The film seems to fall back on the familiar surrogate father/son dynamics at the center of most Anderson movies, but here filled in less concretely.

In short, after one screening I was left thinking the film was somewhat diffuse and flat. But I need to see it again. I thought better of Boogie Nights and Punch-Drunk Love after re-viewing them, so I look forward to trying to sync up with The Master on another occasion. Alas, in Madison, Wisconsin, I won’t have a 70mm image to entice me.

A bit of each, and both

Luther Price, No. 9 (handmade glass slide, 2012).

Analog imagery came into its own on other occasions, notably during the two programs of experimental films gathered under the heading “Wavelengths.” (At one I spotted Michael Snow in the audience.) Expertly curated by Andréa Picard, these programs assembled some strong, provocative films by several young filmmakers. I won’t review each one here–Michael Sicinski provides very useful commentary on nearly all those I saw—but I must mention the striking slide show that served as an overture one evening. The images didn’t move, exactly, but they might as well have.

Luther Price has been making remarkable films on 8mm and 16mm for several years, and one Wavelength program featured his Sorry Horns, a three-minute mix of abstraction and found footage. The same mix was evident in the procession of stunning handmade glass slides. Many, like the one surmounting today’s entry, evoke early cinema, decay, and clichéd Christian imagery: the wounds of film deterioration become cinema’s stigmata. Even the sprocket holes and soundtracks are invaded by festering particles. Arp-like blobs, pockmarked faces, and spliced and sliced movie frames lie under grids as irregular as medieval leaded windows. This is all gloriously analog.

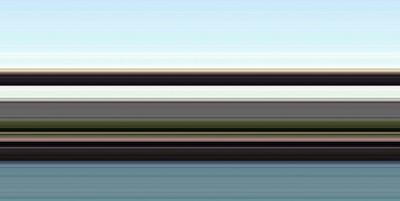

No less captivating is the new, 100% digital work of an even older master of American avant-garde cinema. In one Wavelengths program Ernie Gehr offered us Departure (2012), a train trip playing on optical illusions in the spirit of Structural Film. We all know what it’s like to sit on a stationary train but then feel, when another train passes, as if we’ve started to move. Gehr translates this kinesthetic illusion into optical terms by filming, first upside down and then in judicious framings, several railbeds rushing by, faster and faster.

These layered ribbons sometimes unfurl right, sometimes left, and sometimes simply hover there as fixed, pulsating strips, all but losing the details of rail and tie and spike. Sometimes the one on top moves right, the grass verge beside it moves left, and the bottom track moves right (or left). This creation of flip-flop movement harks back to Side/Walk/Shuttle (1991) and to Gehr’s 1974 exercise in traffic abstraction Shift, which filmed patterns of commuter traffic from a very high angle.

Accompanying Departure was one of nineteen pieces in Gehr’s Auto-Collider series. Most of them contain some recognizable imagery, Gehr explains, but not number XV, the one we saw. In a sense the distilled essence of Departure, that film’s whooshing planes become vibrant, and vibrating, stacks of bold color, a bit like Daniel Buren in a joyous mood.

How did Gehr create the gorgeous Auto-Collider images? He declined to explain. Kristin suggested a plausible means to me, but I’m keeping quiet. In the analog age, when new methods of abstraction required a lot of sweat equity, filmmakers freely explained their painstaking work with lenses, light, and optical printers. But digital video practice flattens the learning curve. Powerful discoveries like Gehr’s or Phil Solomon’s are very easily replicated without much time, toil, or talent. Hell, somebody would make an app for them.

These artists are right to have trade secrets, just as magicians do. We should be satisfied merely to look. What we see reminds us that both analog and digital media harbor possibilities that go beyond the ability to replicate phenomenal reality. Both media can also dazzle us with things we’ve never seen, or imagined.

Digital projection seems to be taking over the festival scene, if TIFF is any indication. Cameron Bailey reports in a tweet that of the 362 films screened, 232 (64%) were in the Digital Cinema Package format and another 79 (21%) were in HDCam. The remainining 51 (15%) were in 16mm, 35mm, and 70mm.

Are the digital items still films? Robert Koehler suggested that maybe we will start calling everything movies. Interestingly, at the Wavelengths screenings, the artists called their artworks (whether on film or on digital video) “pieces.” Me, I still vote for calling films films, even if they’re on video, just as we have books in digital formats (such as, oh, I don’t know, this one). For me, at least these days, a film is a moving-image display big or small, whether it’s on film or some other medium. For some purposes we may want to specify further: Just as e-book and graphic novel indicate a platform or a publishing format, TV movie or video clip tells us more about what kind of film we have.

See also my January entry on festival problems with digital projection.

Thanks to Cameron Bailey, Andréa Picard, and their colleagues for enabling my visit to TIFF.

The industry screening of The Master at TIFF. Photo by M. Dargis.

Solomonic judgments

The Great Blondin, from American Falls.

DB here:

Before you read any further, please go here and look and listen. Click on a few of the sample clips, such as Still Raining, Still Dreaming and Rehearsals for Retirement. Now try the extracts from American Falls here.

Take your time; I’ll wait.

Back? Good.

These excerpts can give you the flavor of Phil Solomon’s extraordinary filmmaking better than any prose of mine could. Solomon has been a major figure in the American avant-garde for nearly thirty years. I’m no expert on his work, but his visit to Madison during our film festival last month gave me a chance to see some of it the way it should be seen: On a big screen, with superb projection and sound thanks to our new Kinotons. (Phil said his films had never looked or sounded better.)

Phil Solomon came of age in the late 1970s, after American experimentalists had already created several imposing masterpieces. Bruce Conner, Stan Brakhage, Hollis Frampton, Ken Jacobs (with whom Solomon studied in Binghamton), and many other filmmakers had in the 1960s and early 1970s given the world what Solomon calls Big Films. Collage-based (Conner’s A Movie and Report), lyrical (Brakhage’s Twenty-Third Psalm Branch), Structural (Frampton’s Zorns Lemma, Jacobs’ Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son), or narrative (Jim Benning’s 11 x 14), these monumental works were intimidating in their length, ambition, and formal and thematic sweep. What were young filmmakers to do?

Phil Solomon came of age in the late 1970s, after American experimentalists had already created several imposing masterpieces. Bruce Conner, Stan Brakhage, Hollis Frampton, Ken Jacobs (with whom Solomon studied in Binghamton), and many other filmmakers had in the 1960s and early 1970s given the world what Solomon calls Big Films. Collage-based (Conner’s A Movie and Report), lyrical (Brakhage’s Twenty-Third Psalm Branch), Structural (Frampton’s Zorns Lemma, Jacobs’ Tom, Tom the Piper’s Son), or narrative (Jim Benning’s 11 x 14), these monumental works were intimidating in their length, ambition, and formal and thematic sweep. What were young filmmakers to do?

Some of the juniors, Tom Gunning pointed out in an influential essay at the time, backed off from these epic visions. Aiming at a more intimate cinema, they used their forebears’ discoveries in modest, fairly impersonal ways–somewhat as Wallace Stevens’ chiseled compactness reworked the techniques that Eliot splashed on a bigger canvas in The Waste Land. Solomon agrees that he joined this deliberately “minor” filmmaking tradition, exploring the fine grain of imagery and what Gunning calls “submerged narratives.”

The task these young filmmakers set themselves was to present a recognizable world, and then poeticize it in a more modest way than the 1960s generation had. The tension between pictorial abstraction and realistic representation is central to much cinema, but it’s felt most keenly by experimentalists. Solomon pursued the problem through found footage and rephotography. Uncomfortable shooting original footage, particularly of people, he preferred to scavenge home movies and classic films to rework at his leisure. He filmed from television, old films, even Super-8 viewfinders. His optical printer stopped or stepped shots or blew up bits of the frame. He became identified with one particular technique: the use of chemicals to alter the film after it had been processed.

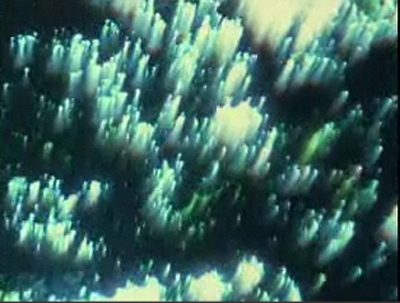

Solomon’s classics are unabashedly beautiful. The Secret Garden (1988) draws on children’s literature and film to present a dazzling image of paradise. James Cameron’s Avatar gives us glowing branches, but with the bland sheen of a Doré illustration. Who wouldn’t prefer Solomon’s radiant, evocative forest, created through optical printing distorted by lens aberrations?

Like Bruce Conner, Solomon enjoys popular media and its iconography, but unlike Conner’s his concern isn’t satiric or ironic. The Twilight Psalms are drawn from Twilight Zone and Outer Limits episodes, and images of Houdini flit in and out. The purpose is to enhance mystery and, inevitably, a sense of mournful decay.

The risk in such ravishing imagery is that it becomes merely pretty. Solomon doesn’t want to make decorative films, he says, and the pulsing, swarming shapes that gnaw into the figures recall the ravages of decomposing nitrate stock. Solomon says he practices “reverse archaeology”: “I throw dirt back on.” Dirt never looked better.

He’s reluctant to talk much about his methods, worrying that the conversation will turn away from the viewer’s experience. But he explained to us that once he has obtained his images, he “unmoors” them chemically by loosening the emulsion and subjecting it to chemical treatment. The result allows fungal growths and craquelure to overrun areas that harbor the silver bromide grains. Like embossing, the technique adds roundness and shading to the flat images. It reminds you that film has volume and that it can become, at very minute levels, a sculptural art.

Another risk of dazzling us with imagery is that the overall form of the film becomes elusive, merely a support for striking effects. One feature of both Structural Film and New Narrative was an insistence, in P. Adams Sitney’s phrase, on overall shape. Watching films like Zorns Lemma and J. J. Murphy’s Print Generation, the viewer is invited to work out a broad architecture into which each moment fits precisely. Solomon’s films are more diffuse, avoiding patterns that are perceptible on first acquaintance and moving toward more associative and elusive organization. What binds the films are recurring motifs (e.g., the hospital patients glimpsed in the punningly titled Remains to Be Seen) and emotional tone, often a quiet melancholy that builds toward lamentation.

I haven’t seen some of Solomon’s newest work, which reconfigures imagery from video games in the manner of machinima. Again, the samples on his site are very intriguing. But one screening at Madison brought us a very impressive recent item. At the end of the 2000s Solomon seems to have felt ready to tackle his own Big Film.

American Falls developed over several years, partly in reaction against the “one-liner art” Solomon saw as dominating the Whitney Biennial. American Falls began life as a gallery installation but in the 2010 version we showed in Madison, it was a triptych running nearly an hour. If The Secret Garden refers obliquely to children’s literature, here a national myth is boldly thrust forward. No “submerged” narrative here.

Referencing Ives’ “Three Places in New England” as well as Griffith, Keaton, Citizen Kane, Night of the Hunter, the Titanic, All Quiet on the Western Front, Pearl Harbor, the Rosenbergs, the JFK assassination, and the Civil Rights movement, American Falls offers nothing less than a panorama of twentieth-century American history. It starts with Annie Edson Taylor, who in 1901 became the first person to survive going over Niagara Falls.

The shots, bronzed throughout, seem stamped onto the surface of the screen, even as textures wriggle and pulse within the contours. I was reminded of a Rauschenberg combine, in which all manner of source imagery is given a busy but unifying finish. Another analogy is Gavin Bryars’ great musical piece The Sinking of the Titanic, which incorporates shards of spoken testimony into a ceaseless, majestically somber texture. (You can listen to some of it here.) Needless to say, Solomon references the Bryars piece too.

The film is a plangent survey of the failures of a dream: America has fallen. Yet even this “night prayer,” as Solomon calls it, can’t cancel the captivating charms of his pictures and sounds, and he knows it. When he was asked why Hitler didn’t appear in his saga, he replied that he didn’t want to make Hitler beautiful.

The sources for American Falls are listed extensively on Solomon’s site. (Another return to Big Art form, as with Eliot’s Waste Land footnotes?) In any case, on a single screening the film seemed to me to achieve a resonant eloquence. Big or small, a Solomon film merits seeing, hearing, and study. Although the films shine forth best on a big screen, Phil looks forward to making his work available to wider audiences on DVD. So do I. These are films you can live with a long time.

Tom Gunning’s essay mentioned above is “Towards a Minor Cinema: Fonoroff, Herwitz, Ahwesh, Lapore, Klahr and Solomon,” Motion Picture III, 1/2 (Winter 1989-90), 2-5. A detailed interview with Solomon appears in Scott MacDonald, A Critical Cinema 5: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers (University of California Press, 2006), 199-227. Jacob W. at Making Light of It provides a very useful dossier on Solomon’s career, with some critical essays. Two strong essays on Solomon’s videogame-inspired films are Michael Sicinski, “Phil Solomon Visits San Andreas and Escapes, Not Unscathed: Notes on Two Recent Works,” Cinema Scope no. 30 (Spring 2007), 30-33, available here; and John P. Powers, “Darkness on the Edge of Town: Film Meets Digital in Phil Solomon’s In Memoriam (Mark LaPore),” October no. 137 (Summer 2011), 84-106.

Solomon’s vimeo page displays other aspects of his interests.

Special thanks to John Powers for programming these films and bringing Phil to Wisconsin.

P.S. 22 April 2019: Phil Solomon died on 20 April. This is a huge loss to American film. Because some of my links to his work online have failed, I’ve revised the references supplied at the start of this entry.

Crossroad (2005; Phil Solomon/ Mark LaPore).