Archive for the 'Experimental film' Category

Paris-Berlin-Brussels express

Doktor Satansohn.

Our trip to Europe has come to an end, and so we finish with a post scanning some highlights.

The magic lantern learns new tricks

DB here:

What am I seeing? Many avant-garde films pose this question. Mainstream fiction film and documentary cinema have mostly relied on the idea that the image should be recognizable as “what it is.” But one strain of experimental film has worked to delay or even prevent us from making out what’s in front of the camera.

Sometimes we lose our bearings only briefly, as when we eventually identify pot lids in Ballet Mécanique or bits of sunlit linoleum in Brakhage films. Sometimes language points out what’s really there. The titles of Joris Ivens’ Rain and the Eames’ Blacktop: The Washing of a School Play Yard allow us to enjoy the ways that ordinary sights can yield unexpected abstraction. Sometimes we toggle back and forth, as when in Ken Jacobs’ Tom, Tom, the Piper’s Son recognizable human figures, however grainy, jump into sheer blotchiness and then back into something like legibility. But other times we can’t ever tell what we’re seeing. Brakhage’s Fire of Waters offers one of the best examples I know, with its jagged bursts of light in a smoky void.

What am I seeing? The uncertainty was doubled during my visit to Ken Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern performance at the Cinémathèque Française. I say “doubled” because at least with Fire of Waters and Tom, Tom I knew I was watching a film. With this display, What am I seeing? started as a question about the format itself. Was it a film, a video, or something else?

Then the question became the customary one. Off-white textures—pebbly, dribbly, stalagmite-like—swim in and out of focus. Some are viscous and globular, some are like tangled foliage. They seem to spiral, but actually (I put up a finger to measure) they barely move. The effect of movement is given by pulsations of pure black, breaking the lyrical effect of the surfaces with a harshness that becomes aggressive. Aggressive as well is the soundtrack, blocks of sound from subway platforms and traffic and kitsch Latin percussion, all played at high volume. The surfaces just keep shifting and not shifting, sort of rotating while jabbing out at us, lovely and anxiety-inducing at the same time.

At the end of the performance, people crowded around the cardboard booth in the middle of the theatre. As Ken and Flo Jacobs packed up, they showed how they had generated the effects. What had I been seeing? Neither a film nor a video but a true magic-lantern display, assembled on the spot. But what had I been seeing? Something created with home-made equipment of a startling simplicity. (Strapping tape was involved.) Our magicians explained their tricks, like magic-lantern operators of earlier centuries explaining the science behind their shows. But I think it’s best that you not know until after you have a chance to see what they create.

In earlier entries (here and here) Kristin and I have praised Jacobs’ films for showing how very slight adjustments in technique or technology can create disturbing cinematic illusions. In this vein, the first item on the Cinémathèque program, a video called Gift of Fire, turned Louis Le Prince’s brief 1888 street scene into a 3D movie. (The homage was appropriate because Le Prince experimented with multiple-lens cameras.) The Nervous Magic Lantern performance generated a different sort of illusion, one conjuring up micro-landscapes and otherworldly vortices. In all, Jacobs makes us realize how many evocative effects are still to be discovered by tinkering with images thrown on a screen.

Detour to Berlin

KT here:

As David mentioned in last week’s entry, I took a week in the middle of our visit to Europe for research at the Ägyptisches Museum in Berlin. The staff there welcomed me into their storerooms, and I spent the days looking at fragments and the records of their discovery and the nights downloading and backing up my photos. No time for filmgoing. The most I managed was a trip to the well-stocked arts bookshop Bücherbogen, which has one of the best selections of film books to be found in Germany. Our old friend, experimental filmmaker Carlos Bustamente, met me there, and we had a quick cup of tea–most welcome on a cold morning when the results of the biggest snowfall in decades were still blanketing many sidewalks and roads.

I did note one film-related phenomenon, however. Every day I took the S-Bahn from Savignyplatz to Friedrichstrasse. The tracks pass directly across the street from the Theater des Westens (that is, the western part of Berlin). It was playing Der Schuh des Manitu, a musical version of the  highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

highly successful 2001 German film of the same name. (I hope the publicity photo at the left was taken in warmer weather than I experienced.) I mentioned the film here, in reference to the fact that every major producing country, and some minor ones as well, turn out their own local comedies, films that don’t travel well but are very popular locally.

By now it’s a familiar phenomenon in the U.S. for successful Hollywood films to be turned into stage musicals. It wasn’t always so. Back in the 1950s and 1960s, films were made of popular musicals, sometimes successfully, as with My Fair Lady, and sometimes not, as with Mame. But now the trend is the other way, with everything from Shrek to Hairspray getting the Broadway treatment.

It’s interesting to know that the same thing goes on abroad, though I’m not sure how prevalent such adaptations are. Der Schuh des Manitu, directed by Michael “Bully” Herbig, remains the highest grossing German film. Herbig doesn’t act in the stage play, as he did in the film, but he served as a creative advisor. The musical is a hit, having premiered on December 7, 2008 and it is expected to continue until at least the autumn of this year. There are several clips from both the film and the musical on YouTube. This one, at 8 minutes, gives a generous dose of the show. There are no subtitles.

I had only a couple of days back in Paris before we headed for Brussels for the final week of our trip. The German theme continued, since a few of the 1910s films David needed to see at the Cinematek here were German. The one I most wanted to see was Edmund Edel’s 1916 feature, Doktor Satansohn. Its main claim to fame is probably the fact that Ernst Lubitsch plays the title role. My book with Lubitsch started with his 1918 move to features, when he began to concentrate more on directing and less on acting. By 1920, with Sumurun, he appeared onscreen for the last time; being discontented with his performance as the tragic clown, he decided it was time to move behind the camera for good.

In the short films he starred in before 1918, Lubitsch often played a brash, ambitious Jewish youth, as in Der Stoltz der Firma (“The Pride of the Firm,” 1914). In Doktor Satansohn he’s a physician with a magical machine that transforms older women into beautiful young ones. We’re first introduced to a couple and the wife’s mother. When the latter makes a pass at her son-in-law and is rejected, she seeks the doctor’s help. His machine works by capturing the wife’s essence in a statuette and making the mother look like her daughter. Problem is, every time she’s about to kiss the husband, the doctor pops up with his devilish leer, visible only to the “wife.” David and I decided that the film is a comedy, though perhaps one only Germans of the day would find truly amusing. For one thing, the title character is clearly a Jewish caricature, one played to the hilt by Lubitsch. He decorates his machine with the Star of David and a Hebrew inscription (not to mention vipers and an image of Saturn).

Stylistically it’s a fairly conventional film for its day, though the black background of the doctor’s office, with its stylized youth machine and satyr-like bust, gives a hint of Expressionism to come. (See our topmost image.) Inevitably near the end there comes the moment beloved of historians of pre-World War II German cinema. The real daughter, released from her imprisonment in the statuette, confronts her double in the doctor’s waiting room. The Doppelgänger motif strikes again.

I wonder if German films actually have more Doppelgängers in them than appear in other national cinemas. Do they really reflect the disturbed soul of the nation? Or did the possibilities of filmic special effects draw moviemakers to try and multiply single figures? Georges Méliès and Buster Keaton used in-camera techniques to multiple their own figures in virtuoso displays. I recall being impressed by The Parent Trap‘s duplication of Hayley Mills when I saw it as a kid, and the whole notion of a single actor playing twins and other lookalike relations is a common enough convention. In Doktor Satanssohn, the doubled figure appears only in this one shot, and it’s the leering Lubitsch, delighted with his own nastiness, who walks off with the picture.

The 1910s, again, and still

DB again:

We saw Doktor Satansohn while I was studying staging and cutting strategies of the 1910s, thanks to the remarkable holdings of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, also known as the Cinematek. My comments on last summer’s visit are here.

Another German film, in a choppy Russian print, vouchsafed a new glimpse of Asta Nielsen. In Totentanz (Urban Gad, 1912), she plays a guitarist-dancer who must take to the stage to support her infirm husband. She attracts the devotion of a composer, and soon she feels attracted to him. Torn between desire and duty, she snaps during a rehearsal of his latest piece, “Totentanz.” In a chilling gesture, she uses his dagger to slice her lute strings.

Soon the two are locked in a violent erotic struggle, and a stabbing ensues. In all, melodrama as ripe as one could want.

As ever, I was happy to have my hypotheses about tableau staging confirmed by several of the titles I saw. A minor French bedroom farce, Le Paradis (M. G. Leprieur, 1914 or 1915), had a brief passage of the sort of blocking and revealing we find in many films of the period. The painter Raphael Delacroix (no kidding) is pretending to be the lover of Claire Taupin to deflect the advances of randy M. Pontbichot. But Claire is actually the mistress of M. Grésillon. . . .

First, very frontal staging strings out Pontbichot, Raphael, and Claire. The older man relents in his pursuit of her.

In the vivid depth characteristic of the tableau tradition, Pontbichot withdraws. But his position accentuates that central door, which starts to open.

Most remarkably, Pontbichot ducks almost entirely behind the couple, giving pride of place to M. Grésillon’s arrival in the center of the shot.

Pontbichot slides out in time to register Grésillon’s outraged reaction to finding his mistress in another man’s arms.

Grésillon rushes to the frontal plane, furious. As ever, a thrust to the foreground creates a major spatial/ dramatic event.

Although the Le Paradis passage is ABC compared to the emotionally powerful patterns of staging we find in Ingeborg Holm (1913), it illustrates how even average films could resort to the blocking/ revealing tactic within the deep-space geometry of the tableau.

More flamboyant was Il Jockey della Morte (1915), an Italian circus film made by the Dane Alfred Lind. Its bold lighting and varied angles on the Big Top recalled the Danish films of a few years before. Halfway through, Lind launches a dazzling chase that features leaps from a tall bridge and bicycling stunts on a cable stretched across a river.

Another Italian film, this time a diva vehicle, suggests that by 1917 1923 (see below) the tableau style was already giving way had given way to scenes organized around close shots. (See below.) L’Ombra (Mario Almirante) starred Italia Almirante Manzini as a lively, trusting wife who becomes paralyzed. While her husband betrays her with her younger protégée, she gradually recovers bodily movement. Yes, a paralyzed diva seems a contradiction in terms, but one small-scale scene shows a remarkable range of emotions. Berta’s hands start twitching, one lifts up, and she stares wildly, as if it were an alien being.

In an earlier scene, Berta had asked that a mirror facing her be tipped upward so that she would never see herself sitting immobile. This shot pays off now, when the hand ascends almost magically into the bit of reflection she can see.

When the hand descends, her astonishment turns into joy. She experimentally shoves the hands together, as if asserting her control.

In the end, she kisses her hands as if they were pampered children.

Manzini runs through many more micro-emotions than I’ve indicated here, but this sample is typical of the ways in which L’Ombra avoides the long-shot choreography of only a few years before and builds a performance out of face, body, and arms in a close framing. The mirror-shot motif shows that fairly careful filmic construction was emerging at this point too.

During my stay, I learned more about tinting and toning from the ever-helpful Noël Desmet. On the seldom-seen World War I drama L’Empreinte de la patrie (M. Dumeny, 1915), some images had curious oscillating patches of rusty brown. Noël explained that when Prussian Blue toning was combined with rose tinting, the chemicals eventually reacted to alter the pink cast. An example is shown at the top of this section, though the blue is more saturated in the original.

Once we get back to Madison, I’ll have to sort out all that I’ve learned from these movies. Onward and upward with the 1910s!

For more on Jacobs’ Nervous Magic Lantern, see Scott Foundas’ interview here. The Youtube clip doesn’t do the spectacle justice. If you must know something of Jacobs’ tools, the Dailymotion video from the performance I saw offers some clues. My notions about 1910s staging are laid out in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light. You can also find several discussions in earlier entries on this site. Just execute a search on tableau.

Now is a good time to thank Noël Desmet and Marianne Winderickx, both of whom are retiring from the archive in March. The research that Kristin and I have done over the years owes an enormous lot to them, and of course to the Director of the Cinematek Gabrielle Claes.

P.S. 15 November 2013: Ivo Blom has pointed out that the version of L’Ombra I saw wasn’t from 1917 but rather from 1923. Hence the corrections above. Thanks very much to Ivo! Go here for his blog and information about his newest publication on silent Italian cinema.

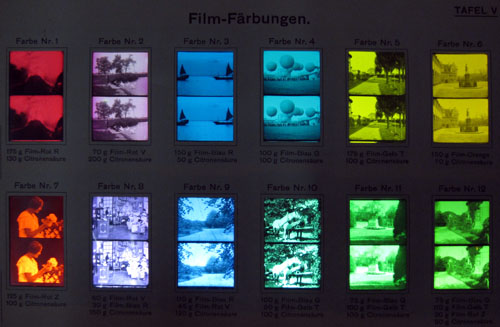

A tinting and toning sample card from the early 1920s. Courtesy Noël Desmet.

Wantons and wontons

Oxhide II.

DB here, with more from the Vancouver film fest:

Two of the more innovative films I saw evoked film history—one explicitly, the other obliquely. Raya Martin’s Independencia is part of a planned series devoted to the history of the Philippines, told from the bottom up. In this first installment, villagers flee into the jungle to hide from the American “liberation” of their islands. The film centers on a mother and son who, joined by a woman the son finds, create a new family. After years, the son and the woman have a child, but their new life is threatened by the encroachment of the invaders.

What sets Independencia apart is Martin’s effort to create the look and feel of a 1930s fiction feature. He shot the movie wholly in a studio, and the evidently faked backdrops are counterbalanced by gorgeously controlled lighting effects, and even dashes of color. Since virtually no Filipino films survive from this period, Martin gives us less a pastiche than a possibility, a sort of hypothetical archival film. The fact that the film makes aggressive use of Dolby sound, especially during a tremendous storm sequence, only adds to the sense of history being reimagined for today.

More traditional, at first glance, is Puccini and the Girl, a historical drama by Paolo Benenuti and Paolo Baroni. Facts of the case: In 1909, a maid in Puccini’s Tuscan villa, accused of being his concubine, committed suicide. But an autopsy revealed that she was a virgin.

The film’s reconstruction of what happened behind the scenes, tracing the veins of jealousy and deceit running through the household, relies on recent research into the tragedy.

At the same time, we have an homage to silent cinema. In most scenes we hear no dialogue: actors whisper at a distance from us, or simply conduct themselves without speaking. What words we do hear are recited pro forma (the Mass) or sung (in a waterside tavern, or in nondiegetic accompaniment). There is only one line of conversation, and that is given greater saliency by being a cry from the heart.

So we’re largely confronted with a silent film, accompanied by music and sound effects. To add to the estranging effect, characters communicate chiefly through letters and telegrams—exactly as in the films of the period. We hear the letters’ text read aloud, but the sense of stately compositions propelled by written commentary, distinctive features of 1910s cinema, remains. An unwitting homage, perhaps, but one that pleased this fan of classic tableau cinema.

Independencia was part of the Dragons and Tigers thread, one of the hallmarks of the Vancouver event. Year after year it gives an unequaled view of current Asian cinema. This year’s program, assembled by Tony Rayns and Shelly Kraicer, was at least as fine as ever. Eight films compete for the $10,000 prize given to first or second features. The winning film, Eighteen by Jang Kun-jae, centered on the familiar situation of teenage lovers separated by parents and school pressures. I didn’t see all the competitors, but my own favorite was Chris Chong’s Karaoke, a Malaysian story of a young man coming to terms with his mother’s decision to sell her karaoke bar. The first ten minutes are quite creative, disorienting the audience through complicated sound mixing, while the boy’s community, devoted to the production of palm oil, is presented with a documentary directness.

Outside the competition, I saw several Asian films of consequence. I’ve already discussed Yang Heng’s Sun Spots and Bong Joon-ho’s Mother. Ho Yuhang’s At the End of Daybreak marks a shift from his lyrical first feature, Rain Dogs, which I reviewed at Vancouver in 2006. A plot situation close to that of Eighteen is treated in much darker tones. A young man falls in love with a high-school girl, but he’s driven to murder by her growing indifference to him. The familiar elements of furtive sex, drinking parties, and demands from the girl’s family for reparations are given a noirish treatent. Ho’s admiration for American crime novels shows in his increasingly bleak handling of the affair. Here the femme fatale is a high-school girl, and the entrapped male’s revenge is complicated by an unexpected erection.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Also under the influence of classic crime films was Yang Ik-June’s Breathless from Korea (right). It shows a brutal debt collector coming to terms with his childhood. Under a harsh surface realism, the film has the contours of the familiar redemption of a hard case, including the decision to reform that comes a tad too late. (Whenever a crook vows that this will be the last time he pulls a job, wait for the ironic retribution.) I thought that the character parallels (two scenes of murdered mothers) were somewhat too neat, but the director plays the anti-hero with conviction and deadpan humor, and Kim Kkobbi supplies an exhilarating turn as the tough high-school girl who becomes his companion.

Bong Joon-ho has been something of a leitmotif on this site lately, with my comments on Influenza and Mother. Under the rubric “Bong Joon-Ho & Co.,” Dragons and Tigers screened a collection of shorts paying tribute to the Korean Academy of Film Arts. Most were from the 2000s, but Kim Eui-suk’s Chang-soo Gets the Job, dated from 1984. Focusing on a gang of teenage purse snatchers, Kim’s film was a little rough technically, but it built its story deftly. The quality of the rest was quite strong, with the grisly and wacky Anatomy Class (2000, Zung So-yun) being a high point. Meanwhile, Bong’s Incoherence (1994) shows that his urge to deflate official hypocrisy, seen in Memories of Murder and The Host, was already present in his student days.

My admiration for Hirokazu Kore-eda runs high, as I indicated in my discussion of Still Walking at last year’s VIFF. But Air Doll, while full of vagrant pleasures, left me unsatisfied. The Kafkaesque premise, derived from a manga, is that an inflatable saucy-French-maid dolly comes to life, endowed with speech and movement but retaining her seams and air valve (both of which will figure in the plot). Her sad-sack owner doesn’t notice the transformation, but while he’s at work, she takes a job at a video store and wanders the city.

The aim, I think, is to defamiliarize ordinary city life by seeing it through Nazomi’s eyes. The fact that a sex effigy is the most innocent character in the movie is part of the point. Makeup, money, and fashion start to seem extensions of sad, solitary eroticism, and the line between mainstream movies and porn gets blurred. But all the thematic elements didn’t blend very well, and at moments, as during the music montages showing people’s desperate loneliness, I worried that for once Kore-eda had slipped into conventional sentimentality. The tone also shifts, with a climax that revises the big scene of In the Realm of the Senses. Kore-eda deserves credit for his unflagging effort to try something fresh with every project, but here, it seemed to me, that the film was defeated by an overcute conceit and underdeveloped execution.

The most exciting Asian film I saw at VIFF was Liu Jiayin’s Oxhide II. Her first feature, Oxhide, was screened at Vancouver in 2005. (Full disclosure: I was on the jury that awarded that film the D & T prize.) This one seemed to me even better.

To say that this 132-minute film is about a family making dumplings is accurate but misleading. To add that the action consumes only nine shots makes it sound like an arid exercise. In fact, it’s a consistently warm, engaging—I don’t hesitate to say entertaining—film that is also a demonstration of how a simple form, patiently pursued, can yield unpredictable rewards.

In the first Oxhide, we saw the comedy and tensions of Liu’s life with her parents, who run a leatherwork shop. By the time she shot part two, they had already lost their business, but the sequel presupposes that the shop is still going, albeit coming to a critical point. So there’s a quasi-documentary aspect, as the family’s financial strains, discussed cryptically at various points, hover over the mundane process of wonton cookery. Yet although everything looks spontaneous, it was all completely staged—written out in detail, rehearsed over months, reworked in test footage, and eventually played out in “real time.”

And in real space. The first shot, which consumes twenty minutes, shows Liu’s father pummeling a hide in his vise and eventually clearing the table for serious food preparation.

Actually, the film’s subject is that table. On its surface, a meal is prepared; around it, the family gathers; we even see what happens underneath. We watch father and mother chop scallions, mince pork, twist and yank dough, pinch the dumpling wrappers around the filling. We watch the daughter try to match her parents’ dexterity. This is a movie about housework as handiwork, and family routines and frictions.

For minutes on end, we see only hands and arms; Liu’s 2.35 frame often chops off faces. Liu employed a construction-paper mask to create the CinemaScope format within HD video. Why the wide frame? Most filmmakers use it for expansive spectacle, she remarks; but “I wanted to see less.” And the horizontal stretch further emphasizes the table.

As if this weren’t rigorous enough, Liu has filmed the table from a strictly patterned arc of camera positions, dividing the space into 45-degree segments. These unfold in a clockwise sequence around the table. What could seem an arbitrary structural gimmick is justified by the fact that each setup proves ideally suited to each stage of the process. When father and mother team up to start the meal, the angle gives us two centers of interest. And Liu feels free to “spoil” her mathematical structure by varying the height and angle of her camera. Plates, bowls, and an articulated lamp become massive outcroppings in this micro-landscape.

Oxhide II is unpretentiously inventive, quietly virtuosic. Evidently it took a Chinese filmmaker (whose day job is writing TV dramas) to blend domestic life with the rigor of Structural Film. Liu displays the fine-grained resources yielded by several cinema techniques, from framing and staging to lighting and sound. The finished dumplings get constantly rearranged on the cutting board. Each family member has a different technique for pulling off bits of dough, and each gesture yields its own distinctive snap.

I had to think, almost with pity, of all those US indie filmmakers who believe they have to cultivate CGI and slacker acting, to seduce investors and strain for outrageous sex and edgy violence. Liu made this no-budget, low-key masterpiece over years in a single room, and with her parents. That’s a new definition of cool.

Liu promises us another installment. In the meantime, every festival that’s serious about the art of cinema should pledge to show Oxhide II.

Puccini and the Girl.

PS 12 October: Thanks to Matthew Flanagan for correcting an embarrassing typo.

PS 15 October: Thanks to Ben Slater for correcting yet another one!

A welcome INFLUENZA

DB here:

Kristin and I are en route to the Vancouver International Film Festival, after a few days in Seattle visiting Sanjeev and Megan, nephew and niece-in-law. We were completely awestruck by the vast holdings of Scarecrow Video, where even the Warner Archives special-order DVDs can be rented. We also had a good long talk over JaK steaks with Jim Emerson, impresario of the superb website Scanners. Not to mention catching a screening of the lively Walt & El Grupo at the Seattle International Film Festival theatre. As a big fan of Saludos Amigos and Three Caballeros, I was thrilled to learn the background story, as well as to watch gorgeous 16mm Kodachrome footage.

Last year’s trip to Vancouver put us on the road for thirteen days, encountering movie-related stuff (and Obama) in surprising places. This time we took the plane—faster but less relaxing. To get a better look at the landscape, we’ll be taking a train up to Vancouver.

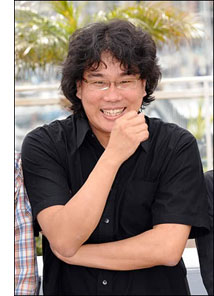

One of the films I’m most looking forward to at Vancouver is Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, brought to this year’s event by Tony Rayns. Alas, Bong himself will not be joining us. I enjoyed meeting him at my first Vancouver visit in 2006, when this blog was in swaddling clothes. He’s completely frank and unpretentious.

One of the films I’m most looking forward to at Vancouver is Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, brought to this year’s event by Tony Rayns. Alas, Bong himself will not be joining us. I enjoyed meeting him at my first Vancouver visit in 2006, when this blog was in swaddling clothes. He’s completely frank and unpretentious.

Even before meeting him, I had followed Bong’s career with keen interest. I think he’s one of the best Korean directors, though he probably doesn’t get as much attention as some others. Like the Japanese Kore-eda Hirokazu, Bong is the sort of quiet genre-hopper who’s hard to pin down. His first feature, Barking Dogs Never Bite, is a charming romantic comedy that also offers a portrait of neighborhood life. The mordant Memories of Murder (2003) quietly bends the conventions of the city-cop-in-a-village movie, mixing comedy into a serial-killer tale. Bong’s biggest commercial success came with The Host (2006), a monster movie in the grand tradition that manages to be at once scary, funny, and socially critical. Seeing it again this summer, I was struck by its compact elegance. Bong makes complex narrative and stylistic twists look easy.

Bong has also made some acute short films; he seems to understand that they require the snappy impact of a well-wrought short story. Probably his best-known short is the “Shaking Tokyo” segment of the omnibus movie Tokyo (2008). It focuses on a hikikomori, a young man who has withdrawn from social contact and lives wholly through the TV monitor and the computer screen. Bong’s hero tidily stacks empty pizza boxes along his walls like installation art. Only an encounter with a delivery woman makes him question his robotic seclusion. The ending, which lures our hero outside, provides a Twilight-Zoneish twist.

More single-minded, though, is a short I’ve just seen, the little-known Influenza (2004). There are several movies based on surveillance-camera footage; one of the most lyrical, Optical Vacuum, I reviewed here. Bong went instead for narrative. He staged a story in locales covered by surveillance cameras, and then retrieved the footage from the hours of material. Cut together, the shots follow Mr. Cho, a failed salesman who turns to petty theft and violent crime.

We discover Mr. Cho in men’s rooms, car parks, and ATM stations. The scenes, each shot in a single take, run through various spycam techniques: fixed high angle, black and white imagery, stuttering motion, mechanical scanning of the scene (sometimes leaving the main action behind). We see wide-angles, telephoto shots, barely legible long-shots, and split-screen imagery picking out opposite points of view.

Everything we see is staged, I think. Unrehearsed events seldom look this cogent and poised. Yet sometimes, especially during the climactic crowd scene, some of the action seems to have been left to luck.

Short but not sweet—mostly sour—Influenza shows what an ingenious filmmaker can do by setting himself a single, precise problem. Crossing the border between commercial fiction and avant-garde experimentation, the film deserves wider circulation.

As for Mother, Derek Elley’s Variety review promises the trademark Bong blend of gentle comedy and unsettling drama. And Vancouverites have an extra bit of luck: A program of shorts by Bong and his colleagues from the Korean Academy of Film Arts graces the festival this year. Bong’s next planned project, about the wretched survivors of a new Ice Age, shows him to be as unpredictable and unclassifiable as ever.

Thanks to Bong Joon-ho for his help in preparing this entry. The trailer for Walt & El Grupo is here. And there’s a poignant story of the founding and near-demise of Scarecrow Video here.

The Host.

The postman has rung more than twice

Optical Vacuum.

DB here:

While I try to whip up seven lectures for the Bruges Summer Film College and a couple more for the University of Copenhagen and our June Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image confab, I offer some quick notes on notable DVDs and books lugged to our door by our mailman.

When machines film better than they know

Snow blankets a terrace and the furniture on it. A bottle jerks back and forth on a pavement. Christmas lights blink on and off. Everything looks desolate. What people we see scuttle across washed-out landscapes, play mahjongg in stammering gestures, and toil in computer labs under glaring fluorescent lights. What planet are we on?

These images are available to any of us. For two years Dariusz Kowalski trawled through sites like www.opentopia.com for surveillance-camera footage. He chose only material from hidden cameras. He added nothing except some slow motion (“otherwise it would be too fast”) and a voice-over commentary from artist Stephen Mathewson reading passages from a year’s diary. The result was a fifty-five minute assemblage film called Optical Vacuum (2008), which I saw and admired in Hong Kong back in April.

Sometimes the diary account intersects with what we see: Mathewson talks of washing his laundry/ shots of a Laundromat. More often, the voice drifts off on its own. Optical Vacuum isn’t an effort to make a film essay or to create a complex audiovisual dynamic. Mathewson’s diary provides an intimacy that the footage lacks, but I think the film would stand up strongly without it.

As a flow of impersonal views, usually from a distant perch, the footage creates a bleak beauty.

Occasionally a human operator has commanded the camera to focus on something, usually a woman.

But most often the camera is just mindlessly recording.

In the process, the surveillance camera reinvents avant-garde film—not just the barely inflected fields of Structural cinema, but also the time compression and melting glimpses, the reflections and superimpositions, the transient ghosts and brutal geometry we find in silent experimental work by Richter, Vertov, and others. These stupid cameras can’t help turning reality into something else. They don’t know any better.

Optical Vacuum, along with other pieces by Kowalski, can be found on a PAL uncoded DVD from the extraordinary Austrian collective sixpack. The handsomely mounted Index release is available here, and elsewhere on the Net.

Dragons and tigers in the Udine sun

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Italian festivals of specialized cinema are mounted with incomparable flair–lots of screenings, panels, interviews, book sales, and of course outstanding food. Most famous are Pordenone’s festival of silent cinema and Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. But for admirers of Asian cinema, just as important is the Udine Far East Film event, which completed its eleventh installment on 2 May.

Alas, I’ve never been. In its earliest years it overlapped with the Hong Kong film festival; more recently, my commitments elsewhere, such as Ebertfest, have kept me away. But I have followed this celebration of Asian cinema at a distance through its remarkable publications.

The Udine event concentrates on popular cinema, mostly recent releases that are unlikely to come to US theatres or video stores. You can see films from Japan, Korea, and China but also from Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines. This year’s highlights include regional hits like Cape no. 7, Beast Stalker, Departures, and Ip Man as well as obscure and delirious items like Love Exposure and The Forbidden Legend: Sex and Chopsticks. Many screenings are European premieres.

The programmers also mount adventurous retrospectives of rare items. One year it was a survey of the work of Patrick Tam, still too little known among Asian aficionados. This year the retrospective was devoted to Ann Hui’s TV films, which are among her best work. These films, shot in 16mm and broadcast in the 1970s, were strong meat for a culture unused to social criticism in its popular media. Hui’s dramas showed police corruption, the sex trade, abandoned children, and drug addiction. The episodes were researched and scripted under great time pressure, and Hui was allotted two weeks for shooting and post-production. “We were experts at shooting in the streets on the sly.” The stories’ concern for ordinary people and their problems has resurfaced again in The Way We Are (2008) and Night and Fog (2009).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

The Hui volume is a model of the profuse documentation the Far East festival provides. Several concise essays, all in both English and Italian, enhance appreciation of the films. Contributors Law Kar, Shu Kei, and editor Tim Youngs do a fine job of situating Hui’s TV work in its context, and a lengthy interview with the director explores her working methods and intentions. There’s also valuable filmographic information about the episodes (four of them available on DVD).

As if this weren’t enough, the Udine event publishes a mammoth catalogue called Nickelodeon. Each year it’s a treasure chest of enthusiastically presented information. This time around, surveys of 2008 developments in all the major countries are accompanied by Roger Garcia‘s special section on the history of Thai action cinema. A vast section of reviews of the films to be shown rounds out this gift to the Asian cinephile. (A little of this material is available at the Udine site.) There is no coordinated effort to sell the books to the public, but if you want to purchase them, try writing to the festival directors at cec@cecudine.org.

So a tip of the hat to the dedicated Udine team, headed by Sabrina Baracetti, and a signal to you that if you have the time and the money to go, you would surely have a hell of a week. (Note that professors and students are offered lodging for some nights.) Who knows? A director might show up to put the audience in a movie, as Johnnie To once did. Even if you can’t make the trip, the quality of the publications makes them indispensible for research and enjoyable reading.

Rabbits from a hat

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

It’s tiresome to hear novelists kvetching that film adaptations mangle their work. So it’s a pleasure to read Christopher Priest’s brisk account of how his novel The Prestige became a film. In The Magic: The Story of a Film Priest takes us through the whole process, but this isn’t the usual behind-the-scenes tour. He never visited the set or met the principals. Instead we get the viewpoint of a writer living in East Sussex, following the production through agents’ correspondence and the gossip frothing up on Google Alerts.

Priest is a lively writer, and he is frank about the ups and downs of the process. Initially he is happy that Nolan acquired the rights because the novel, a cunningly designed piece of misdirection, seems ideal for the director of Memento. But he confesses disappointment when the Prestige project is sidetracked by Batman Begins (“overlong, simplistic, and dull”). When the production gets under way, there are more swerves in the road. Given an early script, Priest admires the craftsmanship of Jonathan Nolan. But then he’s baffled that Christopher Nolan is saying two inconsistent things: that the film is completely different from the book, and that reading the book will spoil the film. Then again, during a press preview in Leicester Square, Priest succumbs to the film’s intricacies. “It has one of the most complicated and sophisticated narrative structures ever seen in an entertainment film.”

The story of the production ends here, but Priest goes on for about fifty pages to analyze the film in considerable detail. He dwells on the opening, which has no equivalent in his novel, and praises it for its fluent shifts among different points in story time. He appraises various aspects of the film, and he doesn’t stint criticisms. He notes that the Nolans stripped off his contemporary story, crucially altered the roles of the women, and turned his elusive mysteries into plot-driven secrets. Yet he concludes:

There is hardly a line of dialogue or moment of action in the film that can be traced back word-for-word, yet the whole thing is faithful to the novel in spirit, in story and in effect. I have differences with the screenplay in places, but none of those detracts from my general impression that it is a classic film adaptation of an existing novel, one which intending screenwriters would do well to study alongside the novel. (157).

Priest is a former movie critic (for the sturdy old British Film Institute publication Film) and an astute observer of what happens in a shot and on a soundtrack. He contacted me after my March blog entry discussing micro-repetitions in The Prestige and told me of The Magic. I ordered a copy pronto, and I’m glad I did. If you want to give your mail carrier a bit more job security, go to this page and click on GrimGrin Studio.