Archive for the 'Fans and fandom' Category

Memory books, the movies, and aspiring vamps

Kristin here:

We are happy to have a guest entry from our long-time friend and colleague, Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, who recently retired from teaching film at the University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. Back in the 1990s, when David and I were helping edit a series called “Wisconsin Studies in Film” (University of Wisconsin Press), Leslie contributed Reel Patriotism: The Movies and World War I. Now she is involved in a fascinating project on the same period, the 1910s. There is much focus these days on reception studies, which focuses on trying to gauge the reactions of audiences to movies. Reconstructing mental events is a difficult, near impossible task. Yet Leslie has found a way to glimpse the ways in which American girls and young ladies of decades ago consumed and thought about movies: by studying the scrapbooks they left behind. Here’s a sample of what she has discovered.

Fangirls of yesteryear

Kate Key received a scrapbook bound in red leather and entitled My Commencement as a gift from her oldest sister Ruth when she graduated from Lampasas High School, class of 1917.

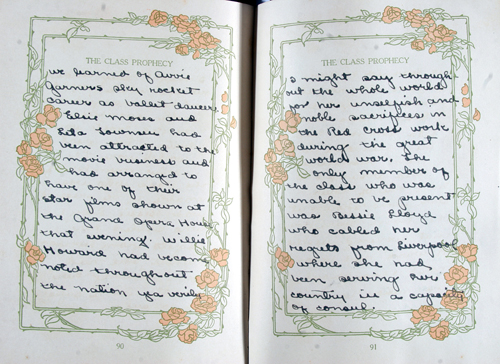

She was eighteen, born and raised in this central Texas farming and ranching community of about 2,100. As far as I can tell, there were no dedicated film theatres in town. Instead, movies alternated with concerts, vaudeville and plays on the bill at the Witcher Opera House. So, I was surprised to read in her class prophecy (a humorous forecast of what the students would be doing in a fictive future) that Elsie Moses and Leta Townsen would return for their class’s reunion in 1928 as movie stars and graciously show their films at the Grand Opera House.

This caused me to wonder whether girls who lived in other parts of the United States also made jokes out of the movies? Might scrapbooks offer film historians like me, interested in the ways that films fit into the lives of everyday people, a new sort of evidence of exhibition and reception in the 1910s and 1920s? When girls mentioned movies in their scrapbooks, or pasted in ticket stubs and theater programs, did they whisper “open sesame” to a quotidian film culture? Was that culture different from and more pervasive than that practiced by fangirls (and boys) who avidly consumed Photoplay and wrote mash notes to their favorite actors? I began to search out scrapbooks, specifically high school and college memory books.

To date, I have collected upwards of 45 scrapbooks. The scrapbooks I have found and studied are mainly the products of white, middle class and upper middle class girls. I have an example or two at either end of the economic spectrum. Despite my best efforts, I have had no luck so far finding the memory books made by African-American teenagers, though I suspect these exist. (I would welcome any suggestions.) New immigrants to the country may not have been aware of this “tradition.”

Before I survey what I have learned from American girls about themselves and about movie-going, let me tell you a bit about scrapbooks.

Multi-purpose compendiums

They have a long history in the United States. Samuel L. Clemons, Mark Twain himself, was an avid scrapbook-maker, and he patented a model featuring self-adhesive pages in 1873. By 1880, how-to books like E.W. Gurley’s Scrapbooks and How to Make Them, Containing Full Instructions for Making a Complete and Systematic Set of Useful Books, guided novices with instructions for what to include and even recipes for the glue to stick objects in place.

Arranged by topic and indexed for efficient access, early scrapbooks consolidated recipes for food or household concoctions. They served as encyclopedias and also provided entertainment. Poetry and fiction were appropriate inclusions harking back to the days of commonplace books. The scrapbook became a means for autobiography and a method of keeping family history. Gurley promoted making scrapbooks both an individual and a collective endeavor. Neighborhoods might organize a scrap-book club, and families could draw on the help of relatives to fill the gaps in their chronicles by bringing their books to reunions. For example, in 1906, Marion Renfrew, a school girl in Boston, invited her friend Eva Alberta Mooar to a party celebrating the “debut” of the “offspring of her labor and patience Memory Book.” Eva saved that letter in her own scrapbook, and the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at Radcliffe preserved Mooar’s book in its archive.

Marketing scrapbooks to girls

Girls were a devoted audience for advice about creating scrapbooks, and the activity became, increasingly, a gendered one. By 1905, scrapbooks were a commodity, mass produced, sold at stationery shops, and complemented by auxiliary  businesses which supported them. Companies manufactured specialty paper corners, some with elaborate designs for sticking photographs to the scrapbook page. One genre of scrapbook was the memory book designed mostly for girls and young women and given to them as presents on special occasions like graduation from high school or college.

businesses which supported them. Companies manufactured specialty paper corners, some with elaborate designs for sticking photographs to the scrapbook page. One genre of scrapbook was the memory book designed mostly for girls and young women and given to them as presents on special occasions like graduation from high school or college.

The Reilly & Britton Company offered eight different titles of school memory books for sale by 1917. The price of these gift books depended on their binding; “Fancy cloth, decorated with gold and two colors,” cost two dollars (about $40 today), but a leather cover with a velvety finish called ooze, added an extra dollar and twenty-five cents.

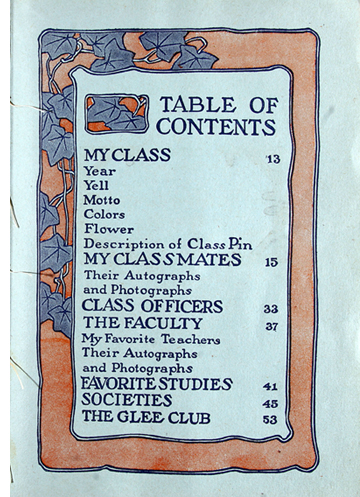

A blank page might have invited girls to fill in stuff of their choosing, but flowery Art Nouveau borders pushed the design toward a notion of conventional, appropriate girlhood. The filled spaces also conjured the metaphor that school was a garden, carefully tended, its flowers growing in tidy uniform beds. Memory books featured standard tables of contents that suggested what girls should preserve and how their mementos ought to be arranged. However helpfully intended, these headings also functioned to delimit what high school included and to prompt girls to tell a cheery, triumphal story in which “favorite” teachers, “best friends,” all sorts of parties, athletic endeavors, and the rituals of graduation would lead ineluctably to the happy reunion foretold by the class prophecy.

Still, what I have come to relish about girls who made scrapbooks is that they did not necessarily abide by the dictates of their books’ blueprints. They surely recognized the ideological requisites of girlhood structured onto memory book pages, but they may not have entirely subscribed to them. Often and idiosyncratically, girls changed and adapted their books.

Girls make scrapbooks to suit themselves

Elizabeth Walker travelled more than one hundred miles from Mineola, Texas to attend the College of Industrial Arts at Denton in 1918. She seemed to embrace the process of compiling My Memory Book. Hers was larger than most: 15” wide, 11” tall, and 2 ¼” thick. It appears that she received it when she matriculated and she filled in the pages as she progressed through her four years of teacher-training. After Elizabeth graduated in 1922, she became a teacher in El Paso. She continued to slide letters, documents including the Code of Ethics for Texas teachers and newspaper clippings, inside the back cover of her book during the 1930s. The most recent insertion was dated 15 July 1969. It was snipped from the school’s (now Texas  Women’s University) alumnae bulletin and brought her up-to-date on members of the class of ’22.

Women’s University) alumnae bulletin and brought her up-to-date on members of the class of ’22.

Still, at the beginning, the freshman Elizabeth had composed a bantering dialogue with her memory book’s table of contents. She treated it as a slightly irritating senior who was trying to tell her how to act. For instance, halfway down the list of things she was supposed to save were pressed flowers and leaves. “Don’t believe in ‘em,” retorted Betty.

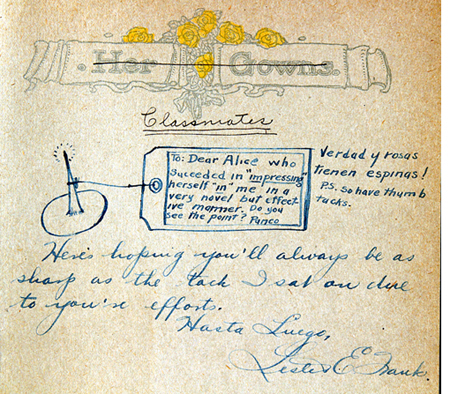

Alice Ebeling graduated in 1919 from South Bend High School in Indiana. She drew a line through the heading “Her Gowns,” replaced it with “Classmates,” and used the pages for autographs from her friends including Lester Frank (left). Apparently, he was on the receiving end of a prank she played in Spanish class.

Corinne Campau, Sophie B. Wright High School, New Orleans, class of 1919, crossed out “Favorite Studies” and pasted in a drawing of a rotund store clerk resembling the Campbell Soup kids drawn by Grace Drayton. Even better, the illustration covered up rude comments Corinne had written about a first-aid class and its annoying, irrelevant, teacher: “IT’S a joke. (‘Girls, I heard a case of a beautiful young woman—Oh, a sweet lovely young woman who fell on a brick + broke her hip.’)”

To me, there is irony, if not a nervous, dark humor in the decision of Fannie Klapman (Murray F. Tuley High School, Chicago, 1920) to glue a little cloth envelope embroidered with flowers on the page designated for “Card Parties.” The description she wrote underneath said, “New Year’s card from my brother at that time in France.” (He mustered out safely and went on to graduate from Crane Junior College in 1920.)

As well as manifesting a playful irreverence, the ways that girls altered memory books testified to a belief in their own agency. Scrapbooks were not private or secret like diaries. Girls took them to school where they solicited classmates’ autographs and good wishes; they showed them to friends who visited their homes. Although I expect many girls started to compile their memory books by following the order set out in tables of contents, when that rubric didn’t accommodate their stuff or their lives, they deliberately, messily, and with the knowledge that their actions would be seen, took matters into their own hands. They also began to make changes in the history of their lives at school almost as soon as they pasted their stuff in place. Memory books, like memory itself, were changeable, dynamic.

Movies and American girls

Since none of the books I have examined contain designated pages for films, how did American girls fit movie scraps into their memory books? When I consider my collection of artifacts, two broad patterns hold.

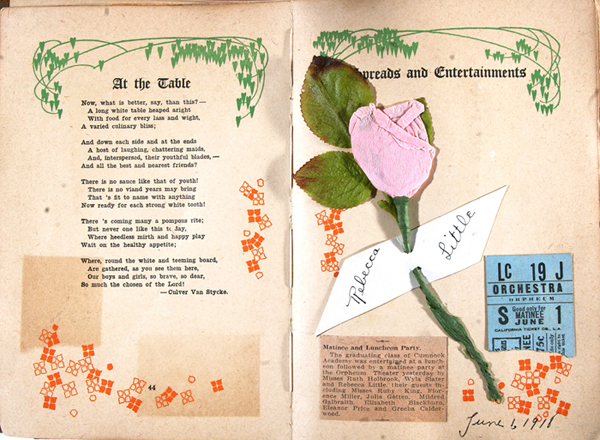

First, girls saved ephemera including ticket stubs, programs, occasionally newspaper advertisements that proved they actually saw films. (Above, Rebecca Little’s scrapbook from 1918.) I’ll call this category “Girls Go to the Movies.”

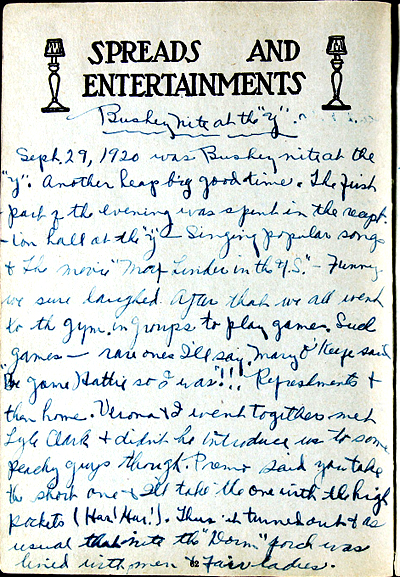

Second, and more intriguing, scrapbooks are crammed full of evidence that girls incorporated the movies–their actors, narrative conventions, and film titles—into a vernacular culture, national in its scope, spanning different religious affiliations. (Above, Hattie Stein’s School Friendship Book describes how she and her friends saw a Max Linder movie at the YMCA in Appleton, Wisconsin.) Let’s name this second motif, “Girls Make Fun with Movies.”

Girls go to the movies

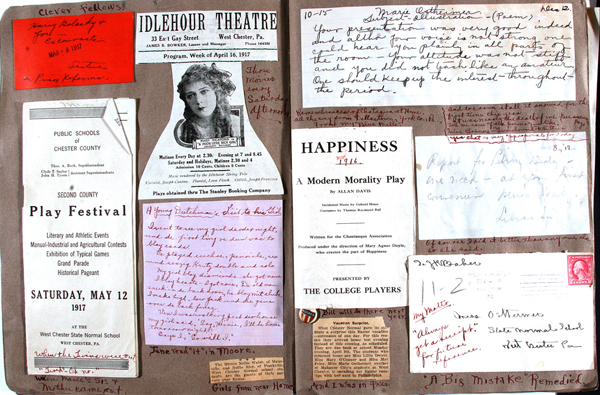

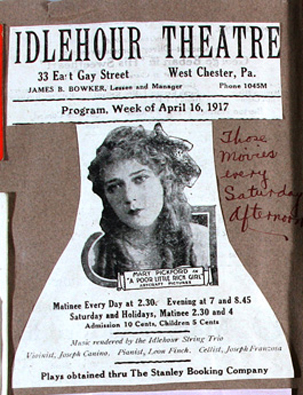

Scrapbooks show that movie-going was one activity among many that mattered to girls in the 1910s and 1920s. No one expressed this better than did Marie Ostheimer, who graduated from West Chester Normal School in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1917. The only mention of film in the thirty-six pages of her Normal Life is the Liberty Bell-shaped newspaper ad for The Poor Little Rich Girl at the Idlehour Theatre which she clipped out (see bottom image). Nevertheless, she captioned it “Those movies every Saturday afternoon.” Her annotated two-page spread surrounds Little Mary with play programs, an excellent evaluation she received for a class presentation, news cuttings about her own and her friends’ trips home, and a receipt that was evidence of some sort of kerfuffle over a doctor’s bill. It is a snapshot of learning, leisure, and life experiences among which going to the picture show was part of the routine of weekend fun.

home, and a receipt that was evidence of some sort of kerfuffle over a doctor’s bill. It is a snapshot of learning, leisure, and life experiences among which going to the picture show was part of the routine of weekend fun.

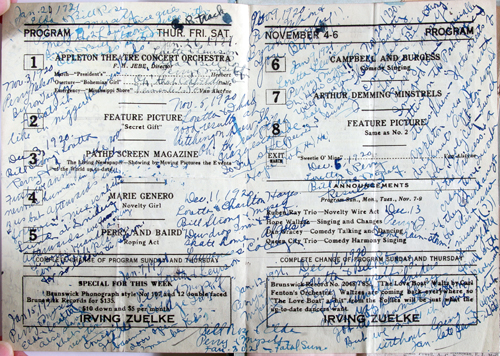

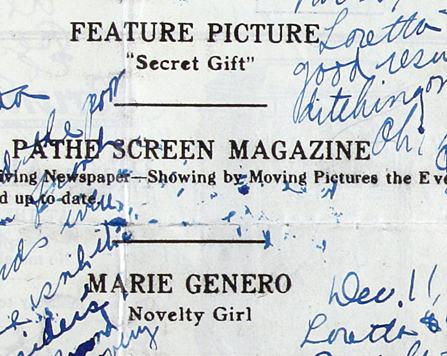

When girls did go to the movies with friends—which always seems to be the case—the screening was only one feature of the afternoon or evening’s or weekend’s entertainment. Case in point: Hattie Selma Stein, Busheys Business Academy, Appleton, WI, 1921-1922. She used a vaudeville program (above, the film Secret Gift is the 2nd turn and the chaser) to record the movies she attended during her year at school. Hattie jotted down the names of her companions, what the weather was like, how they “annoyed” the “nervous humans” seated in front of them, where they had snacks afterwards, and whether she and her boyfriend Perry won the race to the dorm’s porch swing at the end of the evening.

She didn’t always name the movie that served as the pretext for the date. Neglecting to note the film’s title wasn’t unusual in the scrapbooks I’ve examined. Instead, what girls saved was their experience of going to the movies.

For both Hester Swan from Independence, Missouri, class of 1919, and Janet Seidenman, who graduated from Western High School in Baltimore in 1926, food made an evening with friends and films tasty–an adjective which, at the time, meant not only yummy but also “in conformity with good taste.” Swan and twenty others attended a “line party,” featuring Marguerite Clark starring in Mrs. Wiggs of the Cabbage Patch. “After the show Grape Sherbert and Cake were served. We all had a lovely time and enjoyed the show and refreshments immensely.” In a page of her scrapbook, Seidenman drew an arrow from a caption “Richard Barthlemess [sic] in ‘The Fighting Blade.’ Peanut chews were served and everybody was happy,” to her admission ticket, which she also festooned with an inch-long strip of Kodak film negative.

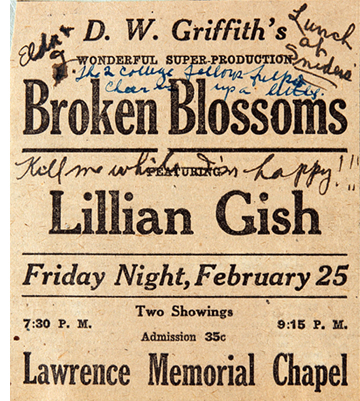

Every so often, though, going to the movies was a special occasion. Girls responded to promotional hype surrounding roadshows. When they saved movie programs, it was invariably from “big” films shown at a theaters which usually presented plays, for instance, the Majestic Theatre in Boston or the Savoy in San Francisco, or motion pictures made on the grand scale by D.W. Griffith. Hattie Stein captioned the ad for Broken Blossoms (right) showing at the Lawrence University Chapel, “Kill Me While I’m Happy.” She also noted that two “college fellows” were on hand to cheer her up and, of course, there was “lunch,” a colloquialism for snacks, at Sniders afterwards.

Girls make fun with movies

Girls did much so more than purchase tickets, sit in theaters, and watch movies before munching on peanut chews. Memory books show that girls around the United States incorporated the movies into their own playful culture. Certainly this is evidence that by the mid-teens, Americans were widely and deeply aware of information about movie stars, narrative conventions, movie-making itself, and the nuts and bolts of film exhibition. I think it’s also akin to the ways girls exercised control over their scrapbooks. When they used movies to make jokes, girls inflected the tone of the film industry’s advertising and narrative messages. They impressed their own proclivities onto increasingly standardized fare. The graduation convention of the class prophecy is a good place to start to see how girls adapted and used the movies for their own purposes.

So you want to be in pictures?

Class prophecies were an American school graduation tradition at least through the 1960s when I completed junior high. They were intended to be light-hearted, funny predictions about the future lives of the members of the class. Prophecies were guided by certain conventions of the form. They were often read publicly during graduation festivities, and it was not unusual to find pages designated for the class prophecy in memory books. Sometimes a prediction hinged on the student’s traits, interests, or romantic inclinations; it could hinge on word play about their name. It was important that the audience got the joke, or most of the jokes.

In nearly every class prophecy I encountered written from 1917 onward, at least one student was proclaimed to be destined for a job in the film industry. The most elaborate example lodged in Bertha Glennon’s memory book. Glennon graduated in 1918 from high school in Stevens Point, WI, the small city where I live. In fact, she was the author of her class’s prophecy and it was also her honor to read it aloud at Class Day a few days before the more formal graduation exercises. (She wore a dress of old-rose colored voile for the occasion.) The rhetorical device she created to frame her story was personal, timely, and more than a little macabre. The United States had entered World War I in April of Bertha’s junior year, and she had done her bit by helping to supervise in the Red Cross Room at school where students rolled bandages.

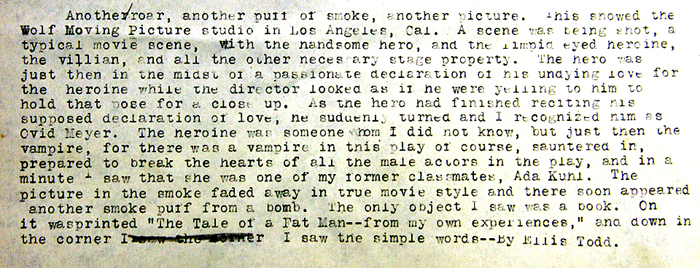

In the class prophecy, Glennon imagined herself as a nurse taking a break from her duties in a hospital on the western front. She sat on a hill and watched bombs explode in the distance. In each burst of smoke, Bertha saw a vision of the future. Boom! As the dusty haze resolved into an image, she identified classmates Ovid Meyer and Ada Kuhl in the midst of shooting a scene for a movie melodrama. Bertha Glennon described mise-en-scene, cinematography, and editing in sharp detail.

Glennon also wrote a diary that documented what she did every day during 1918, so, I know that in the five months leading up to her graduation she went to the movies fifteen times. Once she went on her birthday, another time because she didn’t have a date to the prom. She also recorded once when she went with her mother to visit a sick uncle. At his house she found a movie magazine which she read to pass the time while the grown-ups chatted. Bertha Glennon may have been a little better informed than most of my scrapbook girls, but she was not movie-mad.

Most often in class prophecies, girls were cast as movie stars. Dewene Flynt, Elizabeth Walker’s classmate at Mineola High School (1918) was sure to work for the American Motion Picture Co. and Adelheit M.W. Dettmann of Atlantic, Iowa (1918) was destined to be “Charles Chaplin’s leading lady.” After graduating in 1919 from Sophie B. Wright high school in New Orleans, Elizabeth Wakeman “will play piano at a moving picture show.”

“My Ambitions”

As you might guess, in real-life 1910s and 1920s America, relatively few girls made the transit from the high school auditorium to the movie studio, not even Rebecca Little who graduated from the Cumnock Academy in Los Angeles in 1918. (Martha Graham danced at the May Day celebration at her school that year.) Yet among the young women I have met in these books, one did actually become an actress: on the stage in the 1920s, on the radio in the 1930s, in the movies in the 1940s and 1950s, and on television in the 1950s and 1960s. She also wrote a novel, under the pseudonym Xanthippe, which was adapted into a film. Edith Meiser who graduated from the Liggett School in Detroit in 1917 is the exception that proves the rule. She was extraordinary.

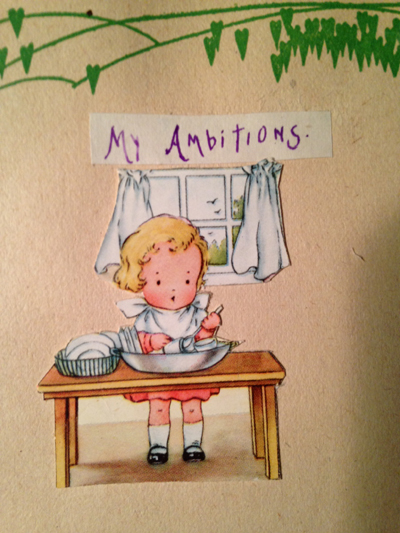

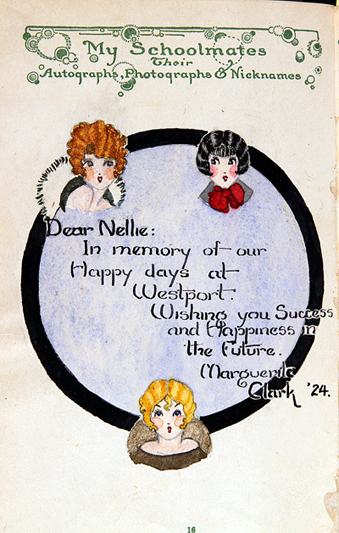

In fact, the hopes girls had for themselves and the wishes they made for others, were, in the main, conventional: success, happiness, good luck, and marriage. In a cartoon of a schoolgirl dreaming of her future, Sylvia Seidenman (Western High School, Baltimore, 1917) might have chosen the nurse with a hypodermic needle, a mother, a scholar, a ballet dancer, or a teacher with a ruler in her hand. Sylvia drew an arrow pointing at the typist, noting “This for me.” Edna Kallberg (Central High, Minneapolis, 1921) cut out and glued down a fat-cheeked toddler washing dishes (below left). “My Ambitions” was the heading which she affixed like a valance above the illustration. Nellie McKeever, from Westport High School, in Kansas City, Missouri (1924) had more talented friends and teachers than most girls did, but the same sentiments abide in their art and calligraphy (below right).

Girls didn’t make jokes with the movies when they autographed each other’s books; they wrote cautionary rhymes. “Long may you live; happy may you tarry, Court whom you please, but mind whom you marry.” (Mollie Winer warned Mary Louise Howell, Commercial High School, Atlanta, 1918.)

Some alluded to infamous moments in classes. Nearly always, they expressed the desire to be remembered. As Beatrice B. requested of Dolly Bennett (Houghton High School, Houghton, Michigan, 1921) “In the wood-box of your memory, save a little stick for me.”

The differences between the humorous fortunes cast for girls in class prophecies and the sincere but commonplace wishes one girl offered to another show that they fully understood a paradox at the heart of the popularity the film industry enjoyed with the American public. The stuff of the movies–its stars and its stories–must be both fanciful and familiar, provocative enough to pique the imagination, but also secure, a safe playground for parody. The industry provided fodder for jokes, whether it meant to or not.

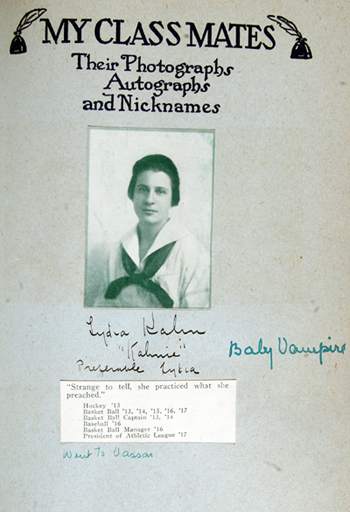

Starring Lydia Kahn, Baby Vampire

I will close this post with one last example of how girls employed the movies for their own amusement, to their own ends. The society these scrapbook girls lived in valued “correctness” in dress, speech, and behavior. Girls realized there were consequences—in life as well as in fiction–for not minding their Ps and Qs. As my grandmother Kate Key might have said, they knew “straight-up.” But, propriety did not stop girls from making fun of the rules governing them as young women, and movies gave them the ingredients for jokes.

Let me introduce Lydia Kahn, “Baby Vampire.” Vampire? The reference is to the character—a woman who destroyed men—made most famous by Theda Bara when she starred in the 1915 film, A Fool There Was. It was based on an 1897 Burne-Jones painting which inspired Kipling’s poem as well as both a play and a novel by Porter Emerson Browne. The movie coined the noun vamp and the verb to vamp. It also sparked jokes among young people all over the United States.

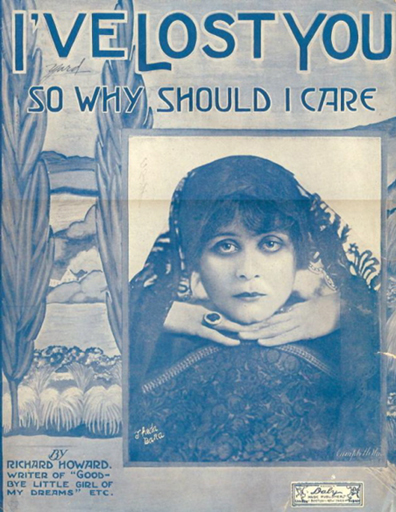

Kahn, the daughter of architect Albert Kahn, was memorialized as a vampire in Helen Schloss’s memory book. The girls were part of a remarkable class of upper and upper-middle class young women, including actress Edith Meiser, who graduated from the Liggett School in Detroit in 1917. The in-joke linking Lydia Kahn to Theda Bara was doubly made. First, there was the epithet Schloss scrawled next to her name. “Baby” in this context means vamp-in-training. Second, I found an allusion to Kahn as Bara in an issue of a little newspaper–more tongue-in-cheek than hard news–that the Liggett girls published their senior year. In a column headed “Heard at Grinnell’s” (a music store in downtown Detroit), one joke referenced a song, “’I’ve Lost Him so Why Should I Cry?’ which paraphrased the actual, “I’ve Lost You So Why Should I Care.” The titular question was attributed to “Kahnie,” which was Lydia’s nickname.

The sheet music portrayed Theda Bara—dressed, I think, for her role in Carmen (1915). Was Kahn a flirt? Had she broken up with some boy? Or, he with her? Was the question in the title ironic? Maybe Lydia Kahn was the opposite of a vamp but she bore a physical resemblance to Bara; perhaps Lydia Kahn did a great imitation of Theda Bara.

We’ll never know exactly why this joke worked so well that Helen Schloss transposed it from the Cap and Gown to her School Friendship Book, but my scrapbook collection can provide a context for interpretation. It turns out that Theda Bara’s vamp is the most common reference to the movies in memory books.

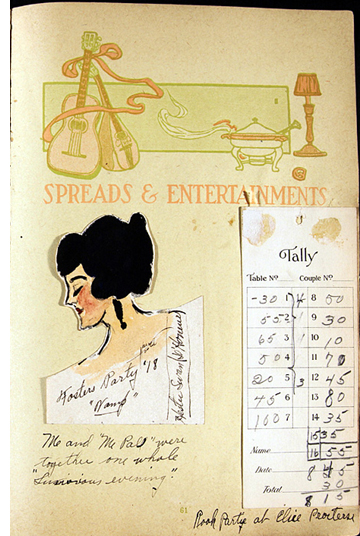

Lydia Kahn wasn’t alone, even in Schloss’s memory book, where Lucile Boynton was available to give lessons in vamping, “Efficiency guaranteed in three easy lessons. Prices reasonable.” Hester Swan’s place card at the Foster’s party (below left) read “Vamp” and pictured dangling earrings and a sophisticated demeanor. Although I expect this evening in Independence, Missouri was innocent, Swan wanted to remember that “Me and ‘My Pal’ were together one whole ‘Luxurious evening.’”

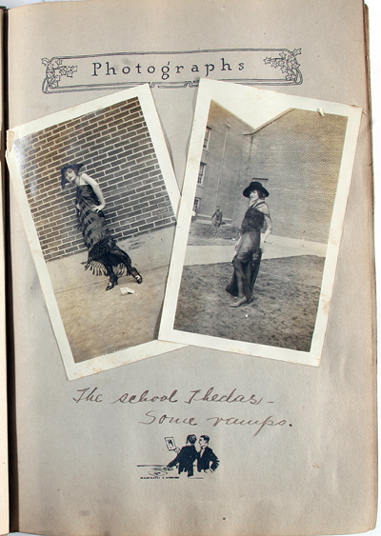

The prophecy for the Sophie B. Wright high school of 1919 foretold how Corinne Campau’s good friend Louisiana Clayton would depose Theda Bara as queen of the vamps after she graduated. This joke may have begun at the fashion show the seniors had hosted for the school’s junior class. Under snapshots of Lou dressed as the “Futurist,” and Aline Richter as “Hobble-Skirt Girl,” Corinne renamed them: “The school Thedas—Some Vamps” (above right). Everything about Lou screamed vamp: her outré costume, the slouchy, hand-on-hip pose, her dark-colored lips. There was another photo on the following page of Corinne’s memory book: here the school Theda is surrounded by classmates costumed as men–some kneeling, others leaning in–as Lou, blasé, looks off the right.

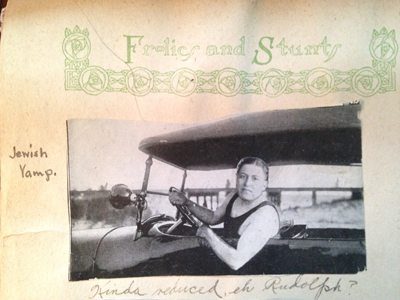

Even boys were liable to be called “Theda” or to be teased as vamps. Adele Franz seems to be recounting an embarrassing moment glimpsed in a boat house when she noted that Alfred J. Peterson, “alias Theda” would star in a production of “As the Lord Made Him.” And, Fannie Klapman printed “Jewish Vamp” beside a collage she had made by gluing the cut-out head of one of her male classmates onto the buff torso of a guy wearing a swim suit sitting at the wheel of an auto (below left ). To amplify the incongruity, underneath the picture she wrote, “Kinda reduced, eh Rudolph?” This might also be early evidence of Valentino’s star persona. No one in Fannie’s class was named Rudolph.

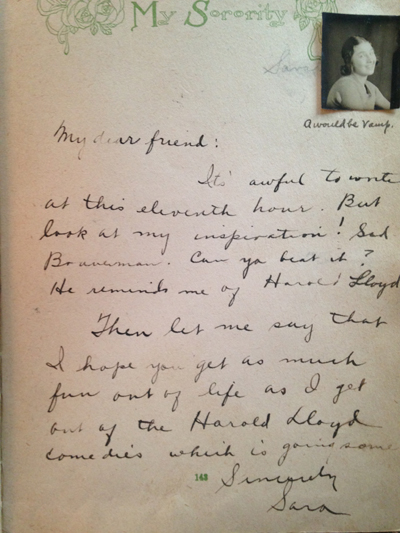

Klapman also commented upon other autographs friends wrote in her memory book. Next to a picture of Sara, who made an analogy between her own good wishes for the graduate and her love of Harold Lloyd, Fannie, somewhat cattily, I think, adds the annotation, “A would be vamp” (below right).

Hattie Stein and her girlfriends in Appleton, Wisconsin wore out the verb, vamping their way throughout their school year in 1920-1921.

What ought we to make of so many Thedas and so much vamping? I’m not entirely sure. If this is an example of an early 20th century meme, then Theda Bara and the vampire she portrayed function to throw conventional femininity and social mores into high relief. Bara was unambiguously evil in A Fool There Was. Girls (and boys) recognized this and camped her up even more. Girls could play dress-up and pretend to be bad—the better they were at the game, the clearer it was that they knew the rules of correctness. When I look at the references to Bara and vamping chronologically (and I surely wish I had more examples from 1915 and 1916), I detect a change. In the earliest mentions, there are connotations of physically sexuality (as with poor, perhaps naked, Alfred Peterson) and an imperious woman (hear the disdainful tone of “I Lost Him So Why Should I Cry” and imagine the smug look on Lou Clayton’s face as she ignores her admirers). By the early 1920s though, it seems to me that all menace has drained from verb and it simply means to flirt.

While there is more to tell about American girls, their memory books, and the movies, I must stop here. For readers who have watched and thought about American silent film or have studied its history, I hope that my research has added to your store. If you are interested in women’s history, I trust the scraps which illustrate this piece have reinforced what you know and have piqued your curiosity. I have grown inordinately fond of many of these girls and fascinated by their doings. My search for memory books continues; they are a rich resource for historians. They are exuberant, charming, funny, sometimes poignant and sad. They bear witness to how girls lived their everyday lives, what possibilities they were able to imagine for themselves, and the ways that movies fit into both these spheres.

I would like to thank David and Kristin for inviting me to share my work with you. It is a huge honor. I would also like to thank Doug Moore for shooting most of my photographs, and Sally Key DeBauche for casting her professional archivist’s eye on my scrapbooks and helping me to think about them as a collection.

Pure hits of storytelling: Westlake, Oswalt, Brackett

To Each His Own (1946).

DB bere:

Old friend and student, and proficient blogger, Paul Ramaeker writes:

I’m in the middle of Slayground now. In his Stark guise, Westlake as a writer really is as fearsomely directed and effective as Parker himself. I was thinking about the particular narrative pleasures here, like the way that delayed exposition works with the perspective switches between different sections. There is such precision to the way he builds certain effects in a systematic way, the way that we see Parker making plans, going around Fun Island doing things, but Stark not telling us what, exactly. I really did not get the logic of painting white circles in the house of mirrors–I thought of them as targets. Then, [spoiler excised] it makes so much sense, and becomes such a pure hit of storytelling, producing such a rush of pleasure in the reading.

That’s the way Donald E. Westlake worked. With Elmore Leonard and Ed McBain, he was one of the top crime-action writers to emerge in the postwar boom in paperback originals. He wrote a huge number of novels and some screenplays (The Grifters, The Stepfather). Several films, notably Point Blank, The Outfit, The Ax, and Made in USA, were taken from his books.

I’ve paid tribute to Westlake’s prose in this entry, but why not another Richard Stark passage to show how it’s done? Many of the novels start with a “When” clause, and upon relaunching the series in 1997, Westlake picked a dilly:

When the angel opened the door, Parker stepped first past the threshold into the darkness of the cinder block corridor beneath the stage.

The “When” clause hooks you in firmly, with the last word of the sentence locking in a framework that explains the opening. Here’s a simpler prototype Westlake himself picked, from Flashfire:

Parker looked at the money, and it wasn’t enough.

Anybody else would have cut the and and put in a period. This is better, I think because it quietly leads us to expect something more: a piece of action, a demand for more money. Anyhow, once we’re arguing about whether to put in an and, we’re talking about a real writer.

Slayground is one of those nifty experiments Westlake tried, this time putting two books in a divided POV arrangement. Both Slayground and The Black Bird begin with the same action, a getaway described almost identically in each one. Parker and his sidekick Grofield separate. One book follows Parker’s fate and other follows Grofield’s. I want to read both right now.

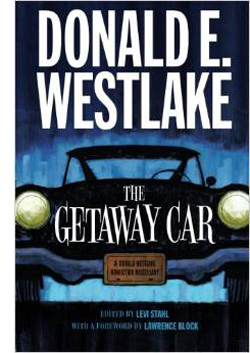

Before I do, though, I must signal (a) the University of Chicago Press’s brilliant idea of reprinting all the Stark novels; and (b) Levi Stahl’s wonderful compilation The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany. This consists of essays, memoirs, and interviews, running from 1960 into the 2000s. There’s even a recipe for tuna casserole contributed by Dortmunder’s girlfriend May.

Before I do, though, I must signal (a) the University of Chicago Press’s brilliant idea of reprinting all the Stark novels; and (b) Levi Stahl’s wonderful compilation The Getaway Car: A Donald Westlake Nonfiction Miscellany. This consists of essays, memoirs, and interviews, running from 1960 into the 2000s. There’s even a recipe for tuna casserole contributed by Dortmunder’s girlfriend May.

You learn a lot about Westlake’s life, of course; for one thing, you learn how Made in USA became unseen in USA for several years. A career-survey interview with a convicted bank robber is alone worth the price of admission. Stahl adds in fragments from an autobiography (“I was born in Brooklyn, New York, on July 12, 1933, and I couldn’t digest milk”).

Westlake was a thoughtful observer of his tradition, and he offers historical surveys and close readings of his hardboiled predecessors. He compares the prose of Black Mask writers Hammett and Carroll John Daly, and calls Raymond Chandler “a bookish, English-educated mama’s boy whose raw material was not the truth but the first decade of the fiction. This is not to denigrate Chandler, or at least not to denigrate him very much.” He praises Richard S. Prather for his “bonkers” style (“She was as nude as a noodle”) and registers his admiration for lesser-known contemporaries like Peter Rabe. He offers the best analysis of George V. Higgins I know, and his appreciation of Rex Stout warms the heart. Acknowledging the cunning ways that Stout hides plot gaffes under Archie’s patter, Westlake notes that perhaps Stout had “an affinity with those Indian tribes who deliberately include a flaw in their designs so as not to compete with the perfection of the gods.”

You also learn about the market. Westlake was a “fee reader” for Scott Meredith literary agency, one of the most prestigious around. He became a self-supporting writer in 1959, when he churned out over half a million words, all published. Writing an Avon paperback in 1960 would earn you $350, or $2800 in today’s money, but writing a serial for a magazine like Analog could net $450 for only 18,000 words. There’s a marvelous letter from that year in which a twenty-seven-year-old Westlake complains to a top publisher that he can’t get his best science fiction accepted, and that specific editors traduce the work of writers he knows. Stahl calls it “one of the most spectacular acts of bridge burning in the history of publishing.” Again, the author’s gesture recalls Parker’s chilly recklessness, but with jokes.

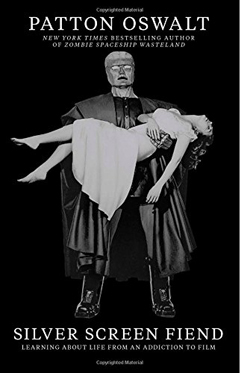

Popcorn and Red Vines

In his recent interview with the New York Times, Patton Oswalt included the Stark/Westlake Man with the Getaway Face as one of his favorite books of all time. It comes as no surprise that this gremlin polymath gets Stark/ Westlake. Those who know his fine Zombie Spaceship Wasteland will find more of the same in Silver Screen Fiend: Learning about Life from an Addiction to Film. As ZSW traced his early standup career and its intertwined relation to nerd culture, this quasi-memoir traces his early years in LA, writing for MadTV by day, honing his comedy act by night, and watching movies obsessively at all other times.

Despite his fondness for sitting far back (I’m down front) and mixing popcorn and Red Vines (I’ve been a Dots man for sixty years), Oswalt has left us the best memoir I know of being a sheer headbanging movie geek. A sort of nonfiction Moviegoer (Walker Percy), or a prose version of Cinemania, that disconcerting documentary in which everything reminds you of you, Silver Screen Fiend takes us into hard-core hell-for-leather filmgoing.

Despite his fondness for sitting far back (I’m down front) and mixing popcorn and Red Vines (I’ve been a Dots man for sixty years), Oswalt has left us the best memoir I know of being a sheer headbanging movie geek. A sort of nonfiction Moviegoer (Walker Percy), or a prose version of Cinemania, that disconcerting documentary in which everything reminds you of you, Silver Screen Fiend takes us into hard-core hell-for-leather filmgoing.

Filmgoing is the operative idea, not just film viewing. The book is set on the cusp of the DVD revolution, when the big-screen experience was so much better in contrast with VHS. There are descriptions of favorite theatres and fetishized experiences like Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast and a Hammer movie marathon. At the same time, this “sprocket fiend” was also a “stage ghoul,” trying to out-kill the other standup comics at the Largo. The two obsessions fed each other, as when Oswalt arranged public readings of the script for Jerry Lewis’ legendary Day the Clown Cried.

Throughout, the movie madness emerges as another channel for the explosive energy of a young man burning with ambition. At the theatre the splendid lunacy might be onscreen, or in the row behind you, where Lawrence Tierney was talking loudly back to Citizen Kane. The moment pulsates because Oswalt wanted to be in movies too, maybe as a character actor.

The book hits one of its high points in telling of his big break, in Down Periscope (1996), where he utters one line as the camera sweeps past him. He describes the process of filmmaking as hammering slowly away at the movie that isn’t there yet. It’s like “blasting a tunnel through a mountain. Or brushing every grain of sand off of a fossil. You attacked it relentlessly.” Oswalt squeezes pages of entertainment out of brooding over how to deliver “There’s a call for you, sir. Admiral Graham.”

Rest assured that every movie you see where an actor delivers just one line? They’ve put this kind of thought into it. Sometimes you can see it. Sometimes they can hide it. But everyone who gets in front of that lens has this inner conversation. I was having mine now. I was about to speak on film.

The moviegoing spiral ends on 20 May 1999, when Oswalt sees Star Wars: The Phantom Menace. The postmortem at a dinner marks the moment when the addiction subsides. “It hits me, sitting there with my friends, that for all of our bluster and detailed, exotic knowledge about film, we aren’t contributing anything to film.” He realizes that film should be one ingredient in the fuel for your life. “But the engine of your life should be your life.”

The epiphany is movingly described. (I wish I could say I’ve learned the same lesson.) Oswalt implies that film frenzy was a phase he went through, and now he’s grown up. (I wish I could say the same for me.) Yet I’m encouraged that Oswalt has not gone cold turkey. He’s passed from gourmand to gourmet. “My love of movies has turned into a love of savoring them.” And he can’t resist movie comparisons when describing that day-and-date release sometimes called Life. “Faces are scenes. People are films.”

In the back of Silver Screen Fiend are thirty-three pages listing all the films Oswalt saw across four years, along with the theatres where he saw them (New Beverly, Nuart, Tales Café et al.). Plenty of pure storytelling hits there. Far from makeweight, these pages create a new list of the kind he obsessed over in Danny Peary’s books. How many twenty somethings will start checking off the titles here?

The team

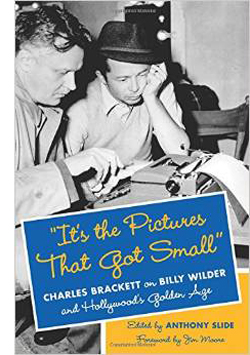

Charles Brackett, Gloria Swanson, and Billy Wilder.

On his very first night at the New Beverly, Patton Oswalt caught, and was caught by, Sunset Blvd. and Ace in the Hole. He mentions they were “co-written and directed” by Billy Wilder. He doesn’t identify the other half of the co-.

Nor do most people. In the case of Sunset Blvd., that fellow was Charles Brackett, who now stands revealed as not only a gifted writer but the Samuel Pepys of classic Hollywood. “It’s the Pictures That Got Small,” edited by Anthony Slide, is an absorbing chronicle of a tempestuous collaboration and the lifestyles of an era. A Harvard-educated WASP from Saratoga Springs, Brackett became a novelist, was made drama critic for The New Yorker, and sat at the Round Table with the likes of Woollcott and Parker. After some of his fiction was adapted to film, he moved to Los Angeles.

Brackett’s early work seems to have been undistinguished, though I’d defend at least Picadilly Jim (1936). Eventually he wound up at Paramount partnering with Wilder, and under the aegis of Lubitsch they clicked for Bluebeard’s Eighth Wife (1938) and Ninotchka (1939). There followed Midnight (1939) and Hold Back the Dawn (1941) for Leisen, and Ball of Fire (1941) for Hawks–an early title of which, we learn here, was Dust on the Heart. Then came Wilder’s directed pictures, from The Major and the Minor (1942) to Sunset Blvd. (1950). Brackett was active in the Screenwriters Guild, became a producer, and continued to write scripts for his producing projects, including the delirious Niagara (1953) and the insufficiently delirious Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959). The Uninvited (1944), Brackett’s first solo production, remains charming, and To Each His Own (1946) is an interesting wartime weepie, with Olivia de Havilland massively frumped up. Miss Tatlock’s Millions (1948) also has its defenders.

“It’s the Pictures That Got Small” is a plump album packed with tiny but revealing snapshots. Although Brackett wrote entries nearly every day, he often made do with very brief mentions. Slide has edited them judiciously and arranged them chronologically, with some stitching to fill in events. A 1936 entry strikes a warm chord:

“It’s the Pictures That Got Small” is a plump album packed with tiny but revealing snapshots. Although Brackett wrote entries nearly every day, he often made do with very brief mentions. Slide has edited them judiciously and arranged them chronologically, with some stitching to fill in events. A 1936 entry strikes a warm chord:

I am to be teamed with Billy Wilder, a young Austrian I’ve seen about for a year or two and like very much. I accepted the job joyfully.

By 1943, Brackett is recording something much more rankling:

My consciousness that, after years of partnership, his first free act was to stab me in the back…my conviction that he’s turned into a second-rate director…my knowledge of the awful thinness of his mind, his stupidly limited interests. Alas, alas. And my knowledge that I am as little stimulating for him as he is for me.

During this supposed phase of creative drought, they were working on The Lost Weekend.

Apart from charting this bumpy collaboration, Brackett gives us a lot of information about how films got made. We learn about studio differences (Paramount less disciplined than MGM) and the importance of telling stories to others, face to face. I found plenty to feed my act-structure appetite. I was happy to find how often moviemakers went to the movies. Brackett attends dozens, both premieres and regular shows, and he records how easily screenwriters could summon up an older picture to be screened, even at a rival studio. This from 1947:

In the afternoon Billy and I saw Mr. Deeds at Columbia to check on certain similar situations in The Hon. Phoebe. It proved helpful and an excellent picture despite curious non-sequiturs and at least one horrible scene, Cooper absolutely charming. I could see some loathsome Capra characters beginning to unfold, but still in the lovely promising bud stage.

As a writer, Brackett is no less captivating than Westlake or Oswalt. We can rejoice in his Algonquin acidity.

Chaplin seems to me as repellant a human being as I’ve ever been in the room with—a thin, reedy voice, a show-off-hog face, and hysterical protestations of liberalism.

Jean Arthur called us, worried about the fact that there’s another woman in the picture [A Foreign Affair]. “I have sex appeal,” she said calmly, but inaccurately.

Greeted at the office by a nasty little note from Charles Jackson [author of the novel The Lost Weekend]. I had addressed him as “Birdbrain” in a telegram, something I could do to any friend—but an unsafe term to use to a man five feet tall.

And there are flat-out funny stories. Here’s just one, reported by Wilder.

[Von Stroheim] has always thought Swanson too young and desirable for the role of Norma. “Look at her,” he said. “I would like to fuck her now.” “I,” said Billy, “would rather fuck you.” “You have,” von Stroheim retorted.

If it didn’t happen, I want it to have.

In short, three more items for your shelf—repositories of good stories in themselves, prods and teases for your own thinking about story-making.

The University of Chicago Press has mounted a fine infographic on Westlake/Stark’s Parker novels here.

P.S. 19 January 2014: Thanks to David Cairns for correcting a slip. My original entry said that Brackett co-wrote Ace in the Hole with Wilder. Actually, the collaborators on Ace were Lesser Samuels and Walter Newman. Be sure to check David’s excellent Shadowplay site.

Down Periscope (1996).

Comic-Con: The end of an era, and other highlights

Kristin here:

Long-time readers of this blog may recall that in 2008 I went to Comic-Con for the first time. I can’t recall exactly what led me to take the plunge. It may have been that by that time it was evident that the con had grown into a major opportunity for Hollywood studios to publicize their upcoming blockbusters to their core audience and I wanted to witness the process in person. Until this year, I hadn’t returned to Comic-Con. I was motivated in part by the fact that this was the last big promotional event for a film in the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise. I had briefly discussed Comic-Con in relation to LOTR in The Frodo Franchise, but I had not witnessed any of the appearances of cast and crew promoting the first trilogy. This was my final chance, the end of an era.

I blogged about my first visit four times. I wrote about the LOTR/Hobbit presence on the Frodo Franchise blog. On this blog I gave an overview of the Comic-Con experience, analyzed why Hollywood poured so many resources into an event nominally about comic books, and posted a conversation between Henry Jenkins and me. Henry, who had helped found the area of fan studies back in the 1990s with such widely cited publications as Textual Poachers, was also a Comic-Con newbie that year, and we shared our reactions. (This year Henry was on a panel, “Creativity Is Magic: Fandom, Transmedia, and Transformative Works,” one of a number of panels on fan culture. I missed it because I was in line for Hall H. More on that below.)

A friend of mine who has a press pass assured me that they were not as hard to obtain as I had feared, so, based on my collaboration on this blog and my position on the staff of TheOneRing.net, I applied. To my delight, I was granted one, so I set out to cover Comic-Con more officially.

Going to Comic-Con alone isn’t nearly as fun, and I was lucky enough this year to meet up there with my friends, Professors Jonathan Kuntz and Maria Elena le las Carreras and their irrepressible daughter Rebecca, who are always terrific company.

Preview night

On the Wednesday evening before Comic-Con begins, there is a preview. This means that people with various special passes can get into the big exhibition hall where most of the booths are set up. These range from dealers in rare comic books to the biggest entertainment companies, like Warner Bros. and Lego. Many of them offer unique items only for sale or give-away at Comic-Con.

Many attendees have realized this, and they buy tickets that include the preview evening. The floor was much more crowded than when I attended the preview night in 2008. There were lots of lines with people trying to get those unique collectibles.

Others were there to look at comics. Yes, there are still plenty of comics at Comic-Con. There are dealers offering rarities, as in the image above. There are comics publishers with their latest offerings.

A particular favorite of ours is Fantagraphics, which specializes in reprinting comics. They’ve launched a set of hard-cover volumes of Walt Kelly’s syndicated Pogo strips. They also, I discovered, are doing a series of Don Rosa comics, also in hardback. In fact, when I was strolling around the booth, I realized that Rosa himself was signing autographs until 8 pm. It was then 7:59, so I grabbed volume 1 and was the last person to get my copy signed. By the way, it includes “Cash Flow,” one of the Uncle Scrooge stories I mentioned in our first blog entry on Inception. Volume 1 hasn’t actually been published, but it’s available for pre-order on Amazon.

The big moment of my evening, entirely by chance.

My first press conference

Once you’re granted a press pass, your name is put on a list made available to the exhibitors and publicists planning events. Companies big and small send you announcements about signings, press  conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

I showed up and got a front-row seat off to the side. The room filled up (right).

The event itself started somewhat late, and two gentlemen who were not Benedict Cumberbatch or John Malkovich appeared and answered some questions. (I would give their names, but the usual signs put on the table in front of guests were not in evidence.) We were approaching 11:25. John Malkovich and another gentleman appeared. Another couple of questions were asked, and someone announced that Benedict Cumberbatch’s plane had gotten in late the night before and besides we had to leave to make room for the next event scheduled in the room. We were not escorted to reserved seats in Hall H, where I hear that Benedict Cumberbatch did appear.

I can only trust that this is not how most press conferences turn out. Perhaps I will be invited to another one and find out.

Bill Plympton in person

Given that I had no option to go to the Hall H DreamWorks Animation presentation, I sought out an alternative among the several items offered during the noon slot. I had had my eye on a panel which had as its guests the well-known animator Bill Plympton, as well as Jim Lujan, the co-director of the feature-length Revengeance, in progress. David and have long been fond of Plympton’s work, especially his laugh-out-loud classic, Your Face (1987), which was nominated for an Oscar. It’s just a series of distortions of a man’s face as he sings an utterly wimpy love ditty (above).

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Apart from clips from Revengeance, Plympton also showed a brand new short, Footprints, a charming tale of a man’s search for a mysterious house invader. It will be shown on August 14 as part of the Hollyshorts Film Festival, which will honor Plympton with the Indie Animation Icon Award. The film was entirely hand-drawn in black and white and then colored digitally.

During the panel there was a contest for a T-shirt. The question was: What is Bill Plympton’s middle name? Despite a plethora of cell phones, laptops, and tablets in the audience, no one could come up with the right answer. A second question was put forth: what was Plympton’s first theatrically released film? “The Tune,” came a cry from the audience. It was Sam Viviano, art director of Mad Magazine; he walked off with the shirt. Plympton then sheepishly confessed that his middle name is Merton.

Plympton’s films have been hard to find online, but this fall they will become available on Source HD: “It’s the entire catalog, everything I’ve ever done.” That includes about 60 shorts. As a result of this online exposure, he says, “I expect that when I come back to San Diego next year they’re going to have to give me one of those huge 2000-seat rooms.” I hope so, and I hope it will be filled–but not so jammed that I could not get a seat.

Plympton offered all attending his panel a free autographed drawing. I went to collect mine at his booth in the exhibition hall and found him drawing (right), as he must constantly be doing. Note the Cheatin’ poster behind him at the left and the usual bustle of Comic-Con in the background. He paused to dash me off a delightful image of his famous Dog character. (An animator who doesn’t use cels has to be really fast at drawing.)

Plympton DVDs are not all that easy to find, though you can get them and other merchandise at his website’s shop. If you don’t know his work, it’s time to start catching up.

A new experience: The Indigo Ballroom

Seeking to accommodate more fans without violating fire regulations, Comic-Con has expanded into nearby buildings. One of the facilities utilized this year was the Hilton San Diego Bayfront, just across from the Convention Center on the Hall H end. That’s where the DreamWorks press conference sort of took place. Its biggest room was the Indigo Ballroom. I’m not sure it had 2000 seats, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

My colleagues at TheOneRing.net have been presenting panels on the Hobbit series for several years now. In fact, my visit to Comic-Con in 2008 was as a participant on one of those panels, speculating much before the fact on the shape that the Hobbit project would take. At that point the cast hadn’t even been chosen. I suggested that Wisconsin’s own Mark Ruffalo would make an excellent Thorin. I still think he would have, but Richard Armitage has gained a large fan following in that role. I’m not sure that at that early stage Martin Freeman was everyone’s favorite candidate for Bilbo, but he soon became so–including mine. The man is a born hobbit.

That 2008 panel took place in a relatively small room in the Convention Center. In more recent years, the TORn panel has been joined by such luminaries from the filmmaking team as Richard Taylor. It has gained such a following that this year it was booked into the Indigo Ballroom.

Then we learned that George R. R. Martin was booked into the same room in the time-slot directly before TORn. (I’m sure you all know who he is, but for the few who don’t, I’ll just say, he’s the author of the “A Song of Fire and Ice” series, of which Game of Thrones is the first book.) We were all convinced that Martin’s session would be jammed and furthermore that an overlap in fandoms would mean that the audience there for Martin would stay for the TORn panel, excluding those who showed up just before the TORn session. There was much discussion as to how TORn staff not on the panel (like me) could get in and be sure of a seat. How many seats could be reserved? We didn’t know.

I determined to support my colleagues and attend the TORn panel. The question was, how many sessions would I have to sit through to make sure I could get a seat? (Rooms are never cleared between sessions at Comic-Con, since doing so would take too much time and would mean that people in one room for a session would not be able to get in line for the next session in that room. Hence the strategy of sitting through multiple panels in the same room to guarantee a seat at the one you really want to see.)

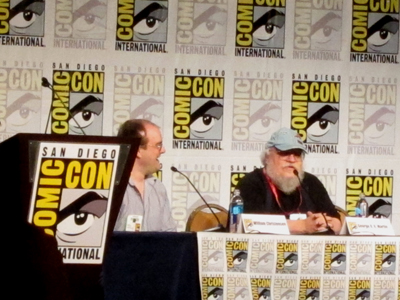

I arrived early in the afternoon in the middle of a session about some show on Comedy Central. This finally ended and the George R. R. Martin panel began. To my surprise, it was only about two-thirds full. I learned later that Martin often attends Comic-Con. Moreover, this time he wasn’t talking specifically about Game of Thrones. The session was billed as “George R. R. Martin Discusses In the House of the Worm.” The title in question is a new comic-book series that Martin is involved with. (Above, William Christensen, publisher at Avatar Press, interviews Martin.)

I had expected to sit through Martin’s session merely waiting for the TORn one to begin. I had read Game of Thrones, widely assumed to be heavily influenced by The Lord of the Rings. Game of Thrones was entertaining, but by the end I found it repetitious. I figured that the series could only become more so, so I quit there. I haven’t seen the TV episodes. Yet Martin turned out to be quite entertaining. He is a long-time fan, and his reminiscences about fandoms during the 1960s and onward were fascinating. He’s a lively, knowledgeable, and entertaining speaker with a wide experience in both reading and creating fantasy works in those days. His presentation made me wish that I liked that first book better.

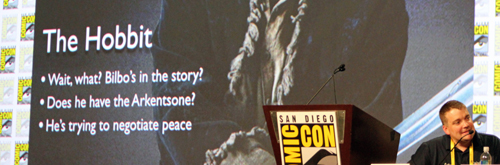

The next session was “An Unofficial Look at the Final Middle-earth Film: The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies.” (Actually in the program the title said “Final Middle-Earth Film,” but I’m sure my colleagues did not make that capitalization error when they proposed the panel.)

The panel consisted of, from the left, Chris “Calisuri” Pirotta, a TORn co-founder; John Tedeschi, long-time staffer; Cliff “Quickbeam” Broadway, frequent contributor to the site; Kellie Rice, staffer and half of the “Happy Hobbits” fan duo; and Larry D. Curtis, another long-time staffer and frequent contributor. Chris and Cliff were among several TORn interviewees when I was researching The Frodo Franchise.

TORn has made annual appearances at Comic-Con, usually speculating in expert fashion on what might be included–or not–in the next film. Staffers comb the previous films, trailers, Peter Jackson’s production diaries, publicity photos, and cast and staff interviews, seeking for clues. While presenting their findings, they point out things in the earlier parts that people might not have noticed or may have forgotten.

The first line in the Powerpoint image above refers to widespread fan annoyance that Bilbo seems to have been pushed to the periphery of his own story in The Desolation of Smaug. This is a topic of frequent comment on the website. The TORn panel was held on Thursday, two days before any of us had a chance to see the first teaser-trailer’s premiere on Saturday in Hall H. (More on that below.) Although there are shots of Bilbo in that trailer, they mainly show him staring offscreen and reacting. I was left hoping that this is not an indication of more sidelining of our protagonist. In Tolkien’s book Bilbo decides to sit out the Battle of Five Armies and gets knocked unconscious early in the fighting; given that he’s our point-of-view figure, the battle is mainly told through other characters describing it afterward. No one expects Peter Jackson to stay true to that action and sacrifice the chance for another epic battle scene, so maybe Bilbo will get to do his share of fighting.

This year’s celebrity guest made an appearance at the end and took a few questions: Jim Rygiel, multi-Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor for The Lord of the Rings (and more recently Godzilla and The Amazing Spider-Man):

Whether the panel members were right in their speculations will not be known until December 17 (in the USA). Right or not, it was an entertaining and informative session.

What were they really there to see?

There are many rooms devoted to Comic-Con events, not to mention the various open-air booths and attractions set up in open spaces near the convention center. Room 25ABC is fairly large, but it’s considerably smaller than the Indigo Ballroom, 23ABC, and of course, Hall H. I was not alone in being puzzled as to why the panel “Fight Club: From Page to Screen and Beyond,” was scheduled in 25ABC at 7 pm on Saturday evening. Sure, the topic was an older film, and the panel was largely devoted to a forthcoming graphic-novel sequel to the story. Still, the participants included David Fincher, making his first Comic-Con appearance. I can only suspect that Fincher was a late addition to the panel’s line-up and it was too late to change the venue.

The result was that anyone determined to hear what Fincher had to say was bound to line up for the panels just before the Fight Club one and sit through them in order to see it. I decided to line up for “Disney’s Gargoyles 20th Anniversary” at 5 pm, having no idea what the Gargoyles are, and “Publishing 360: Building a Bestseller” at 6 pm, having no intention of trying to build a bestseller.

I got into a line that looked fairly short and was defined by lines of tape laid down on the carpets in the broad corridor outside 25ABC. It turned out to be one of those Disneyland-style ribbon-candy set-ups, where the line folds back on itself time after time, and you end up walking in one direction, turning around to walk in the opposite direction, only to realize that there is another group of people doing the same thing ahead of you in the same line. Fortunately most people seem to stick to the rules pretty closely, perhaps being aware of the wrath they would call down upon themselves by attempting to cut ahead of others.

I ended up about ten people back in line when the room was full. I never did learn what the Gargoyles were, but I suspected some people behind me had been hoping to get into that panel and were not there for the Fincher event. Indeed, as it became clear that no seats were going open up, a small number of people departed, leaving me about six people back from the front. It was looking good for me to get into “Publishing 360.”

At this point, from behind me I heard “Pardon me, but are you Kristin Thompson?” or words to that effect. Thus I met Ryan Gallagher, one of the stalwarts of The Criterion Cast, which describes itself as “A podcast network and website for fans of quality theatrical and home video releases.” (It is not officially associated with The Criterion Collection.) I recognized his name because he has sent many a reader to Observations on Film Art. Ryan’s latest podcast is a preview of Comic-Con, and I expect he will add one looking back on his experiences there.

What are the odds, I thought, and still think, that with 125,000+ visitors to Comic-Con, I would end up in line next to someone who recognized me? Turns out Ryan had been in line for the Gargoyles panel, so after a brief conversation, he departed. Eventually I was among the first into the room for the “Publishing 360″ panel, though there were people already there who didn’t leave, and I suspect the audience for Gargoyles doesn’t overlap all that much with the audience of people longing to write a bestseller. The procedure for building a bestseller, by the way, seems to consist primarily of getting the best agents and editors in the world. Aspiring writers, take note. Before the session began, I located an unoccupied electrical outlet and recharged my recorder. (This is a serious business at Comic-Con. The convention center is full of cell phones, tablets, and cameras dangling from outlets.)

The panel as pictured above consists of, from the left: moderator Rick Kleffel, Doubleday executive editor Gerald Howard, Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk, David Fincher, and three artists and/or editors from Dark Horse Comics, which will bring out the Palahniuk-penned ten-part sequel starting in May, 2015.

A lot of the panel was about the graphic-novel sequel, of course. The main bit of new information about the film was that although it didn’t do particularly well at the box-office, Fincher finally got 20th-Century Fox to give him figures on how many DVDs were sold. Sales totaled around 13 million, so Fincher reckons the film must have made a profit in the long run. Probably the quotation from Fincher that will be remembered is: “My daughter had a friend called Max. She told me Fight Club is his favorite movie. I told her never to talk to Max again.” Fincher may not have been to Comic-Con before, but he knows how to please the fans.

Check out the Film website for an audio recording of the panel.

Hall H: Getting in

Hall H tends to draw much of the attention accorded to Comic-Con in the media. It’s the largest venue, with 6500 seats–including a large number reserved for representatives of the studios presenting publicity events there. That’s a big venue, but compared to the roughly 125,000 people attending the con each day, it’s not big enough. Although not everyone at Comic-Con wants to get into Hall H, most days the lines snake down and across the street, along the sidewalks. (A video moving along an entire Hall H line at a walking pace was posted on Youtube last year. It runs for over fourteen minutes, despite the fact that the people toward the front of the line are walking forward past the camera; if they were standing or sitting still, it would have run even longer.) In previous years the only way to guarantee getting into the hall for the first events of a day was to get there the previous evening and stay in line overnight. Short departures were possible if someone held your place, but basically you were there for the duration.

I was lucky enough to benefit from the innovation of a new policy on Hall H admissions. Color-coded wristbands would be handed out as the line formed, pausing at 1 am and resuming at 5am. The first portion of the line got a red band, with other colors for the next portions. The purposes were 1) the management could gauge how many people were lined up; 2) those in line could know whether they would get in or not; and 3) for the first time some people could leave for longer stretches of time than required for a rest-room break, as long as someone from their group with the same color wristband remained.

At least, that was how it was described in the online announcement. Those charged with distributing the bands and keeping order informed us that “a majority” of the group had to remain. To what degree that was enforced, we never learned. Fortunately that worked for Jonathan, Maria Elena, and I, since Rebecca had formed a “Hall H-line” group on Facebook and assembled a bunch of friends to camp out in line together. We adults, with our less flexible bones, departed for dinner and some sleep at our hotel. The next morning when we came to rejoin our group, the people in charge of keeping order asked if we had been to the rest room. Yes, we had. That and other things. Apart from everything else, the parking garage under the convention center has to be cleared after 10 pm, so the Kuntzes had to leave to get their car out. Clearly some clarifications of the guidelines are in order, but based on our experience the new wristband policy has improved the Hall H-line experience considerably.

The announced wristband-distribution schedule also had to be adapted. In the past, the Hall H line has started forming in the late afternoon or early evening, depending on the popularity of the first event scheduled for the following morning. Jonathan presciently went and got in line at 2:30 pm, and he was far from the first. Our party gradually grew as other members arrived, and inevitably groups ahead of us also swelled. Soon the line was very, very long. (A small portion of it is pictured above; the line had taken a U-turn a few hundred feet behind us, off right here.) Somewhere around 6:00 the wristbands started to be handed out, and small groups were escorted across the street to line up in the relatively luxurious area on the grass near the entrance to Hall H. There were white canopies overhead and the inevitable red plastic barriers dividing the area into rows approximately one reclining person wide. Those further back in line were less fortunate, having the sidewalk to call their bed. Our group of young stalwarts settled in for games, sleep, and an endless supply of trail mix and donuts. Rumor has it that anyone who arrived after about 9:30 pm didn’t get in. The last wristbands were handed out at around 2:30am. Presumably the handout did not pause at 1 am as planned, since clearly everyone who was going to get in when the hall opened was already there.

The next morning we received a call from Rebecca saying the group had been moved into the “chutes,” a process which had started at 7 am. These are slightly narrower strips of grass with the same plastic barriers; the chutes are opened one at a time, allowing the people in each to go in before the next chute is opened. More people are moved into the emptied chutes, and the process continues until the hall is full.

Although the handlers had said we would be let in at 9:30 for a 10:00 start, they got the process going at 9 am. By 10 we were all seated and ready for the Warner Bros. extravaganza to begin. There I am, wearing my vintage licensed Fellowship of the Ring T-shirt and the crucial pink wristband:

Expensive flash

Warner Bros. had two hours in Hall H on Saturday morning to promote their films. The full program is not announced in advance. People were assuming that The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies, as the biggest item on tap, would be saved for the end. That turned out to be correct.

The event started with curtains sliding back to reveal a long, panoramic screen on either side of the big central one. This surrounded about the front half of the audience in a U-shaped set of images. Warners installed these screens at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars; naturally no other studios were allowed to use them.

Some short presentations opened the program, beginning with Zack Snyder coming onstage. He introduced Ben Afleck, Henry Cavill, and Gal Gadot, none of whom spoke. We saw a very brief clip from Batman vs. Superman. The two lead characters’ first meeting had them glaring at each other with glowing eyes, white and red respectively. (Naïve me, wondering why if they’re both good guys, they don’t just join forces to fight evil.) My main impression was that Batman looks like he’s wearing a small tank turret on his head. The fans were apparently pleased with what they saw.

The moderator then introduced Channing Tatum, who stood below the screen as a montage of footage from Jupiter Ascending was shown. This made no impression on me, and I have no memory of it, except that the big action scene looked pretty conventional.

The event really got going with a much longer promotion with George Miller talking about Mad Max: Fury Road. This used the side panels to good effects (above). David and I have been fans of Miller and the Mad Max series ever since Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior in the USA) appeared. It was a treat to hear him talk about the new film, though what he said is pretty much what he has said in other interviews: there’s little CGI in the film, he storyboarded the whole thing rather than writing a script, it’s an attempt to do a continuous chase sequence for an entire film, etc.

Miller presented a montage of quick scenes from the film. It looked good but familiar. There’s Max, chained up on the front of one of the villains’ vehicles, as were some of the captives in The Road Warrior. A lot of the minor characters recall those of the same film. The digital image looked brighter and sharper than the previous films–not necessarily a good thing, since the three first films were muted, conveying a sense that everything and everyone was coated with dust. Unseasonal rains in Australia forced the new film’s shoot to move to Namibia, which looks like it stands in for the Outback pretty well. We must trust that, just as the first three films were significantly different from each other, this fourth film will have a unique flavor not apparent in the footage shown.

This was, by the way, the second preview I’ve seen recently of a film that imitates the awesome (in the old and literal meaning of that word) dust-storm in this well-known National Geographic clip online. And why not, though CGI can never equal the real thing in this case.

Hall H for Hobbit

Quasi-Spoilers ahead:

The second half of Warners’ slot was given over to The Battle of Five Armies. An opening blast of music accompanied the appearance from left to right of a panorama of images from all three Hobbit films:

Even this fairly comprehensive view of the screens leaves out two or three images on the far right. The most revelatory of these shows Galadriel, Elrond, and Saruman at Dol Guldur, rescuing Gandalf. The panorama stayed up throughout the presentation. (A rather juddery pan around the whole things can be seen on Youtube.)

Steven Colbert, widely known as a devoted and highly knowledgeable Tolkien fan, MCed the panel, dressed in his costume from the third film, in which he has a nonspeaking bit part. He expressed his love for Tolkien and the films and showed the brief scene in which he appears. Then he introduced the impressive eleven-person panel Warner Bros. had managed to assemble:

From the left, Colbert, Peter Jackson, Philippa Boyens, Benedict Cumberbatch, Cate Blanchett, Orlando Bloom, Evangeline Lilly, Luke Evans, Lee Pace, Graham McTavish, Elijah Wood, and Andy Serkis

Of course, most of us couldn’t see them this clearly with the naked eye. Seated about a third of the way back in the auditorium, my view was as shown in the image at the top of this entry. Peter (that’s he in the lower left corner) looked mighty small in reality, but in Hall H three large screens magnify the proceedings for the crowd. (Similar video screens are used in the other very large auditoriums, notably the Indigo Ballroom.)

One highlight was the first screening of the long-awaited teaser trailer. This was released online two days later; the best place to see a large, sharp image that starts streaming almost instantly is on Peter’s Facebook page. I have to say that it looks pretty promising, apart from the continued presence of the distracting and tedious Azog and Bolg.

I won’t give a complete run-down on this panel, since a good video of it has been posted on Youtube (with the two screenings of the teaser trailer cut out). Much of it consists of typical star chit-chat. The most interesting thing said came from Peter. There has been considerable speculation among fans as to whether the filmmakers will stick to the book and let some characters die during the battle. Peter stated that the grim parts of the book are being retained and implied that several characters will indeed die. (This should mean that here will be much lamentation among the “hot Dwarves” aficionados.)

I won’t give a complete run-down on this panel, since a good video of it has been posted on Youtube (with the two screenings of the teaser trailer cut out). Much of it consists of typical star chit-chat. The most interesting thing said came from Peter. There has been considerable speculation among fans as to whether the filmmakers will stick to the book and let some characters die during the battle. Peter stated that the grim parts of the book are being retained and implied that several characters will indeed die. (This should mean that here will be much lamentation among the “hot Dwarves” aficionados.)

There has also been much speculation as to whether Peter Jackson or anyone else will be filming other adaptations of Tolkien’s work. This question wasn’t addressed during the panel, but the obvious answer is no. The production and distribution rights to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings were sold by Tolkien and his publisher Allen and Unwin to United Artists in 1969. Rather than placing a time limit on the rights, as is customary, they sold them in perpetuity, and any control over the use of those rights forever passed out of the hands of Tolkien and subsequently of his estate. His son Christopher Tolkien has objected to the films that have been made, and he quite possibly will find a way to prevent any sale of film rights relating to the other books, even after his death. The Silmarillion, which takes place primarily in the First and Second Ages of Middle-earth, is, I think, virtually unfilmable. The most filmable single work, The Children of Hurin, is unremittingly grim and would be unlikely to attract any support within the industry. Apart from all that, Peter probably has no desire to prolong the franchise, either as a director or a producer.

In short, we have almost certainly seen the final “Middle-earth” presentation at Comic-Con. I’m glad I was there to see it. The franchise as a whole will undoubtedly have a presence at Comic-Con for years to come. Weta Ltd. has become a major force in the world of film and its future seems assured in a way that it did not a decade ago, when Peter Jackson’s projects were its main customers. Weta Workshop now has taken over making the collectible figures not only for Peter’s work but for other films, and it develops its own original projects for collectibles, television, and publishing. Its booth this year (below) was considerably bigger than the one I saw in 2008. (See the top image here.) It was doing very good business every time I passed by. The full-size Smaug head (above right) attracted considerable attention.

It’s still the case that the vast majority of Comic-Con attendees are not in costume.

All photos down to the one of George R. R. Martin, plus the two of lines for Hall H and the Smaug head on the Weta booth were taken by me.

My camera failed me during the Fight Club panel, so I have borrowed one from Anie Bananie’s Tumblr site, “David Fincher Stole My Life.” The photo of the panoramic screen with the Mad Max image is by Albert L.Ortega for Getty Images and illustrates the Variety story linked as “Warners installed …” in the second paragraph below it.