Archive for the 'Fans and fandom' Category

Pleased to meet you. What’s the greatest movie ever made?

(From the Seth Saith blog)

Kristin here:

Way back in January Jim Emerson participated in the “Movie Tree House” conversation on Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule. On January 14, his blog recounted his discussion of the differences between “average viewers” and those of us who are more intensely involved in films in one way or another:

I met a very nice, intelligent woman (maybe ten years older than me) at a New Year’s Eve party and she told me “The King’s Speech” was the best movie she’d ever seen. I responded politely by showing (genuine) enthusiasm for Geoffrey Rush’s performance. But I don’t know what to say to something like that. I mean, I had no reason or desire to dismiss her, but it wasn’t the kind of statement that calls for critical analysis, either. It was just social small talk. But I believe she was quite moved by the film. And, yes, there’s nothing at all wrong with that.

He added:

I thought of saying, “Wow. My favorite movie is ‘Nashville.’ Or maybe ‘Chinatown.’ Or ‘Only Angels Have Wings.'” But I didn’t think the conversation would have much opportunity to go anywhere from there, so I didn’t.

I suspect Jim’s experience is common among people whose main vocation is writing about films. When I meet someone who isn’t a film buff or scholar, he or she almost inevitably asks one of two questions: “What is your favorite film?” or “What do you think is the greatest film ever made?” From the looks on their faces, I suspect they really want to know the answer and think that it will be interesting, even gratifying. After all, meeting a film critic or historian is less common and more potentially interesting than meeting a mathematician.

Up to now, I have generally answered honestly that I think the greatest film ever made is Jacques Tati’s Play Time and that it’s probably my favorite as well. Or I say that it’s hard to choose, but some candidates would be  Ozu Yasujiro’s Late Spring, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, and Play Time. Almost invariably the smile on my interlocutor’s face fades into disappointment as he or she admits to never having heard of any of these films, let alone having seen them. Awkward pause, with conversation turning to other matters or my making a feeble attempt to say sometime to encourage the person to give these films a try.

Ozu Yasujiro’s Late Spring, Jean Renoir’s The Rules of the Game, Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, and Play Time. Almost invariably the smile on my interlocutor’s face fades into disappointment as he or she admits to never having heard of any of these films, let alone having seen them. Awkward pause, with conversation turning to other matters or my making a feeble attempt to say sometime to encourage the person to give these films a try.

I think I’ve come up with a better way to answer these questions. I’ll say something like, “Well, lately I’ve really enjoyed True Grit and Toy Story 3.” This dodges the question, but the person is bound to have heard of these, likely to have seen one or both, and may well have something to say about them—though I hope it isn’t “Yes, that’s the best film I’ve ever seen.”

Maybe that tactic will work. After all, most movie-goers work on what in cognitive psychology is called “the recency effect.” Our memories of things we’ve just experienced are more vivid in our minds than those from longer ago, even though those older experiences may have seemed equally intense or pleasurable at the time.

I ran across a good example of this effect in an Amazon review of True Grit posted by Harold Greene. Giving the film five stars, he enthuses, “I am reluctant to declare it THE best movie I have ever seen in my life but in five weeks watching it every Saturday night I can recall none to surpass it.” As a fan of True Grit and the Coen Brothers, I would believe that possibly it is the best film Mr. Greene has ever seen. But it could equally be that the intense repetition of viewings may have solidified the recency effect and diminished his memory of other films that he esteemed equally at the time.

More generally, the recency effect tends to be borne out when one of my colleagues in film studies here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison surveys their students at the beginning of a course. The goal is to find out something about their knowledge of film going into the class. One question, “What is your favorite film?” almost invariably elicits a title released in the past year or so.

So I suspect that the party-goer asking about my favorite film would be satisfied with my talking about recent movies I’ve enjoyed. The real puzzle, though, is why such people would ask such questions to begin with.

One possibility is that most people have very little sense that there is a vast body of movies out there, from over a century and from many significant filmmaking countries. Their impression of film history, as reflected in the popular media, could reasonably be that the film I might name as the greatest is probably one they’ve heard of, maybe Casablanca or Citizen Kane or The Godfather or La Dolce Vita or even Avatar.

Could it be that my questioner is hoping, probably without realizing it, that I will name his or her own favorite film? Or at least a title that he or she has seen and enjoyed? Or at least heard of? In the latter case, the person can hold up his or her side of the conversation by responding, “Oh, I’ve heard of that and have been meaning to watch it. I must put it in my Netflix queue.” A satisfactory conclusion to that little stretch of social interaction, and it does happen, albeit rarely.

I try to imagine whether scholars of opera or poetry get such questions at parties. Does someone who has just been introduced to them ask what their favorite opera or poem is? Maybe. I wouldn’t. My typical response on learning that a perfect stranger standing in front of me is a professor of something is to ask what his or her area of specialization is, hoping that it’s something I know a bit about (Vivaldi operas as opposed to Verdi, nineteenth-century Victorian novels as opposed to Renaissance poetry).

to Verdi, nineteenth-century Victorian novels as opposed to Renaissance poetry).

I have to admit, some people I meet at parties do launch in by asking me what areas of film I study, which makes the subsequent conversation less likely to end in mutual embarrassment. That is, with me looking like a pointy-headed, ivory-tower intellectual who wouldn’t be caught dead watching Cedar Rapids (which I’m actually looking forward to seeing) and my new acquaintance looking like an ignorant clod who doesn’t look beyond this year’s Oscar nominees (even though he or she has probably in reality seen quite a lot of excellent movies).

This entry on Jim’s blog led to a touchy exchange in his comments section about whether he and the other participants in the dialogue were being condescending to “average viewers.” This sort of disagreement seems inevitable, since people who know a great deal about any subject are likely to seem condescending to people who don’t, even if that is not their intention. But the question I’m asking is not whether “average viewers” have good taste. Some do, some don’t. So far I’ve just been trying to figure out why many of them seem determined to ask experts questions that will very likely expose their own lack of knowledge.

Beyond that issue, though, is the symptomatic implication of these two nearly universal cocktail-party questions. I think people are more apt to ask “What do you think the greatest film is?” than “What do you think the greatest opera is?” because film is still taken less seriously as an art-form than are the “high” arts. Most people think they know more about film than they do about opera because almost anyone you and I are likely to meet goes to movies more than to operas. The fact that a steady diet of well-reviewed, even Oscar-nominated Hollywood films remains only a tiny slice of the entire range of surviving movies made so far doesn’t occur to them. The same is true even for those who see the occasional indie or foreign-language film.

It used to be that a good liberal-arts education gave a young person a solid foundation in fields like music and art. I took two four-credit semesters of classical-music appreciation as a freshman and have benefited ever since. I took literature courses, and although I took only one semester of art appreciation, I have filled in by visiting museums all over the world. Even so, I would be cautious in trying to make conversation about topics like ballet, which I realize I know very little about.

Yet, the “What’s your favorite film?” question doesn’t just come from neighbors I see only at the annual block-party potluck or over bed-and-breakfast buffets. It comes from college professors who themselves are often specialists in one of the arts. They probably would feel, as well-rounded intellectuals, required to know at least something about the other arts—except film.

David was once talking with a distinguished literary scholar who would have been appalled if someone in a university had never heard of Faulkner or Thomas Mann. But when David said he admired many Japanese films, the scholar asked incredulously, “All those Godzilla movies?”

That’s really the crux of what bothers me about the awkward great-film/favorite-film question. If it’s a non-academic who asks it, it tends to be a conversation-stopper, which is unfortunate. But anyone is entitled to love the movies they want to love and to believe, if they wish, that Avatar is the greatest film ever made.

But when academics who would claim to be well-educated in the arts look blank when I mention The Rules of the Game or one of the other likely masterpieces of world cinema, I do mentally pass judgment. Is it more important to be aware of Monteverdi’s Orfeo or Velasquez’s Las Meninas than of Renoir’s film? Obviously I would say no. Yet I don’t think that these academics feel particularly embarrassed at not recognizing the title of a mere film.

This is not to say that all liberal-arts academics in other fields are ignorant of film and its history. On the contrary, we have friends who certainly know as much about the subject as we do about any other art form. But on the whole, in-depth knowledge of film is fairly uncommon across the campus. There are physicists who play piano sonatas and biologists who love painting, but those typically aren’t the people showing up for our Cinematheque screenings. The question isn’t merely one of taste either. In universities, people in the other arts vote on funding for film programs. If they deep down consider film a lesser art form and hence an inconsequential subject of study, we can expect less support, or perhaps the sort of condescending support that says, in effect, “Well, I suppose that since it’s popular with students we should go ahead . . .”

A final note. If anything I have said here sounds “elitist,” you might consider the vast movement we see occurring in this country’s politics, especially on the far right, where any learning at all is equated with elitism and any experience in public office is equated with being tainted. When our educational system is being systematically downgraded, expecting people to learn things is simple common sense.

PLANET HONG KONG: Fanned and faved

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third, on principles of HK action cinema, is here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. The next entry is concerned with directors, and the final one focuses on film festivals, with a list of a few more of my favorites. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D.

For a long time film academics lived in a realm apart from film fans. But over the last decade or so, the borders have been dissolving. Following the pioneering work of Henry Jenkins in Textual Poachers (1992), academics have started to study fans. More strikingly, they have joined their ranks.

Aca-what?

Michael Campi, fan, and Chris Berry, aca-fan. Hong Kong International Film Festival, 2006.

My generation of 1970s film academics looked down what were then called film buffs, the FOOFs (Fans of Old Films), and the star-gazers who dwelled in Gollywood. We were going to make film studies serious. We over-succeeded. Actually, many of us were fans without admitting it. Many of my peers were shameless fans of Ford, Hitchcock, Fuller, et al. Is the appeal of the auteur theory a form of fannery?

Still, things seem qualitatively different now. I think that the Internet, the arrival of new generations brought up on tentpole movies and HBO, and a boredom with the Big Theory that cast its spell over official film studies, hastened the arrival of what Jenkins has called the Aca-Fan.

The Aca-Fan is a researcher immersed in fan culture without a trace of guilt or condescension. In 1973, a film professor’s office was likely to display a poster for Blow-Up and maybe another for Singin’ in the Rain (approved classic). Today the professor’s office is likely to have something more downmarket—a poster for The Matrix or Fight Club or a Beat Takeshi movie. Look on a bookshelf and you might also find a few Simpsons or Buffy action figures. The emergence of aca-fans lends support to the idea that today geek culture is simply the culture. As Xan Brooks put it in 2003, “We are all nerds now.” Or as Patton Oswalt remarks in his funny Wired essay, “All America is otaku.”

Zapped by zines

Stefan Hammond and Nat Olsen. Hong Kong City Hall, 1996.

Irresistibly drawn to Hong Kong films (the story is in the preface to PHK), I soon found myself in one pulsing zone of fan culture.

If you wanted to know something about this tradition in the late 1980s and early 1990s, your options were limited. There were the annual catalogues published by the Hong Kong International Film Festival, but they were hard to find overseas. Virtually no Western scholars had studied this popular cinema, and the occasional pieces in Sight and Sound, Film Comment, Positif, and Cahiers du cinema made you want more. That more was often delivered by the fans.

They were a mixed lot: followers of the splice-ridden 1970s martial-arts imports that played in hollowed-out downtown theatres; lovers of Godzilla, Ultraman, and Sonny Chiba who saw Hong Kong as another wild and crazy cinema; big-city cinephiles who sought out recent imports at the local Chinatown house; fanboys and –girls in flyover country renting videotapes from Asian food shops and crafts stores. While Internet 1.0 cranked up, they found an easier outlet: print. Designing pages with good old Xerox and cut-and-paste, they created magazines.

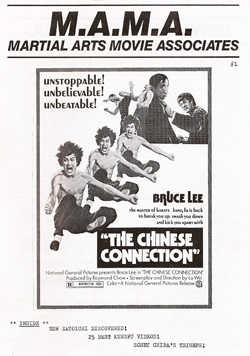

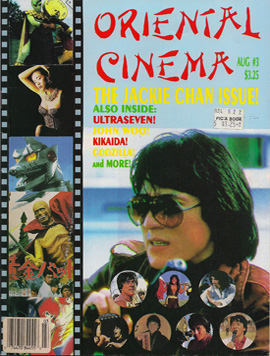

One distant progenitor was Greg Shoemaker’s Japanese Fantasy Film Journal (started in 1968), but the punkish Film Threat (1985) was also important, for it showed that deep-dyed fan publications with attitude could wriggle their way into magazine stands. Soon DIY Asian movie zines burst forth in gaudy profusion and gave the copy shops of the world a new clientele. The early production values recalled high-school poetry magazines, with ragged right margins and nearly illegible illustrations, but the content was compelling. An early entrant was the mimeographed M.A.M.A (Martial Arts Movie Associates, 1985), created by the authors of the still very useful From Bruce Lee to the Ninjas: Martial Arts Movies (1986). A step up in flair was Damon Foster’s Oriental Cinema. Lurid covers enclosed newsprint pages jammed with information, opinion, tawdry gossip, and pictures jaggedly assaulting text. Foster was probably the most colorful editor in the field, making his own films (notoriously, Age of Demons), offering his services as a mime for the blind, and boasting, “I’ve never gone to bed with an ugly woman, though I’ve woken up with quite a few.”

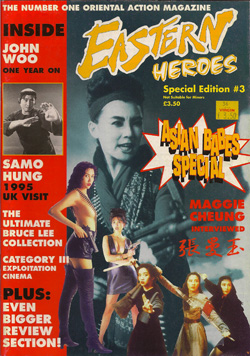

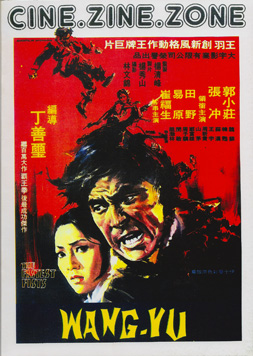

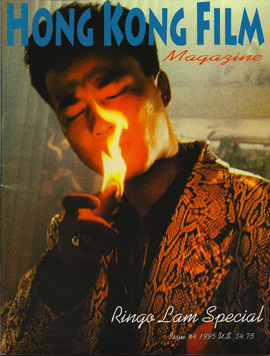

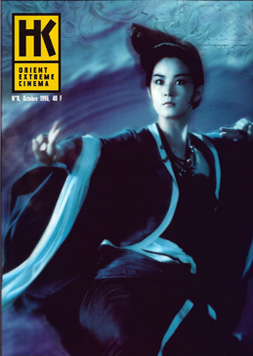

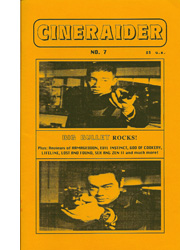

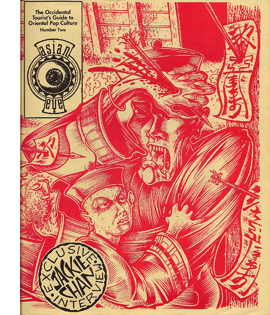

It was a far-flung community. Texas gave us Hong Kong Film Connection and Asian Trash Cinema (motto: “Good Trash Knows No Boundaries”). From Toronto came Colin Geddes’ Asian Eye (first issue: Guns Robots Ghosts Kung Fu). From Honolulu came Richard Akiyama’s Skam and then Cineraider, “published,” proclaimed the masthead, “a few times a year or less.” But soon real publishers brought out slicker magazines. San Francisco had Rolanda Chu’s Hong Kong Film Magazine. LA’s Giant Robot, a phantasmagoria of Asian lifestyles and pop culture, always ran some HK features, as did Tokyo Pop. The UK gave us Eastern Heroes (Free Van Damme Double Impact Poster Inside!) and Oriental Film Review. France had Cine.Zine.Zone, East Side Stories, and the Rolls Royce of the genre, the luxuriously printed HK: Orient Extreme Cinema. Some of these became fan magazines—professional magazines aimed at fans—as opposed to fanzines, magazines made by fans. The HK ones paralleled those devoted to anime, fantasy and science-fiction, and other realms of fandom. I couldn’t collect them all—I missed out on Fatal Visions, for instance—but in an era of scarce information, the ones I found were precious.

It was a far-flung community. Texas gave us Hong Kong Film Connection and Asian Trash Cinema (motto: “Good Trash Knows No Boundaries”). From Toronto came Colin Geddes’ Asian Eye (first issue: Guns Robots Ghosts Kung Fu). From Honolulu came Richard Akiyama’s Skam and then Cineraider, “published,” proclaimed the masthead, “a few times a year or less.” But soon real publishers brought out slicker magazines. San Francisco had Rolanda Chu’s Hong Kong Film Magazine. LA’s Giant Robot, a phantasmagoria of Asian lifestyles and pop culture, always ran some HK features, as did Tokyo Pop. The UK gave us Eastern Heroes (Free Van Damme Double Impact Poster Inside!) and Oriental Film Review. France had Cine.Zine.Zone, East Side Stories, and the Rolls Royce of the genre, the luxuriously printed HK: Orient Extreme Cinema. Some of these became fan magazines—professional magazines aimed at fans—as opposed to fanzines, magazines made by fans. The HK ones paralleled those devoted to anime, fantasy and science-fiction, and other realms of fandom. I couldn’t collect them all—I missed out on Fatal Visions, for instance—but in an era of scarce information, the ones I found were precious.

The fanzines were a rehearsal for the writerly gambits that would be played out high-speed on the web. Although wordage was costly in a print mag, an article could be as garrulous as a blog today. Concluding a report from a film set, the author notes: “If you found this report boring, then I am sorry. If you found it interesting, then I am glad.” The pages saw flame wars as well. “The retreading of that Amy Yip libel is but the tip of the proverbial iceberg for [your magazine] and other fanzines puking out unprovable sludge as though it were straight from CNN.” We watched all the games cinephiles play—exercising one-upsmanship, excoriating rivals, impressing newbies, and expressing pity or contempt for those wanting a snap course in hip taste. More often, there was the hospitality and a sincere urge to share l’amour fou that we find on fan URLs now. Within trembling VHS images, reduced to mere smears of color by redubbing, the writers glimpsed paradise.

I would read the zines for opinion-mongering, harsh or rhapsodic, and data delivery. Apart from pictures, usually of attractive women in swimsuits, the fanzines provided reviews (always with a ranking, usually numerical), interviews, and filmographies. There were lots of lists too; where is our Nick Hornby to commemorate the compulsive listmaking of this gang? Fandom is as canon-compulsive as any academic area, and as meticulous. One issue corrects an earlier Police Story review: “The synopsis indicated that Uncle Piao masqueraded as the aunt of Chan’s character. Actually, he disguised himself as Chan’s mother.”

Cultism reborn

Ryan Law, founder Hong Kong Movie Database and film programmer. Hong Kong, 2007.

As I discuss in PHK, upper-tier journalists usually learned of 1980s Hong Kong cinema from a parallel route, the festivals that began screening the films, usually as midnight specials. Visionaries like Marco Müller, Richard Peña, Barbara Scharres, and the New York group Asian CineVision boldly programmed Hong Kong movies. Critics, particularly David Chute in a 1988 issue of Film Comment, acted as an early warning system too. Meanwhile, the fans were amassing documentation. One zine might be given over to a film-by-film chronology of Jackie Chan’s career; another might solicit Roger Garcia to write about the tradition of Wong Fei-hong films.

One of fandom’s lasting monuments is John Charles’ vast reference book The Hong Kong Filmography 1977-1997, a detailed list of 1100 films with credits, plot synopses, and the inevitable ratings. Charles, a Canadian who wrote for many zines, has been a contributor to Video Watchdog, another generous source of Hong Kong data from the 1980s to the present. Many of Charles’ reviews are available on his site Hong Kong Digital.

By the mid-’90s the modern classics had become known to cinephiles throughout the west. A 1997 editorial announced that Hong Kong Film Connection, despite having a circulation of over 5000, could not continue. Why? Clyde Gentry III explained.

The fandom base has dropped considerably because they have been hand-fed ‘the list.’ You know. The list of films like A Better Tomorrow, A Chinese Ghost Story, Police Story and others that signify the popularity of these films as a collective. It’s even more of a shame that these people will walk away leaving an entire industry with a lot more than that to offer.

Once the canon was established, once everyone had reviewed the standard items and interviewed Michelle Yeoh, agitprop was no longer needed. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez were spreading the gospel, and the surface dwellers could now get The List through real publishers like Simon & Schuster, which produced the still-enjoyable Sex & Zen and a Bullet in the Head. In the hands of Stefan Hammond, Mike Wilkins, Chuck Stephens, Howard Hampton, and other skilled writers, fan enthusiasm blended with turbocharged prose to bring the news to a broad audience in search of offbeat cinema.

Once the canon was established, once everyone had reviewed the standard items and interviewed Michelle Yeoh, agitprop was no longer needed. Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez were spreading the gospel, and the surface dwellers could now get The List through real publishers like Simon & Schuster, which produced the still-enjoyable Sex & Zen and a Bullet in the Head. In the hands of Stefan Hammond, Mike Wilkins, Chuck Stephens, Howard Hampton, and other skilled writers, fan enthusiasm blended with turbocharged prose to bring the news to a broad audience in search of offbeat cinema.

Soon, the Internet created a new era in fandom, with sites like alt-asian.movies newsgroup, Brian Naas’s View from the Brooklyn Bridge, and Ryan Law’s Hong Kong Movie Database. Some zines, like Cineraider and Asian Cult Cinema (Asian Trash Cinema redux), continued for a time online. HKMDB, another monument bequeathed to us by fan passion, remains a central clearing house of information, as do LoveHongKongFilm, Hong Kong Cinemagic, and others. The Mobius Home Video Forum became a robust conversation space devoted to Asian film, and other forums sprang up, most maintaining the old zest for discovery, unexpected information, controversy, and nostalgia. At Mobius the perennial topic, So what have you been watching lately?, has amassed 32,209 posts.

The zines and the Net made fans more influential. Some turned into critics and film journalists, and a few, like Shelly Kraicer, Colin Geddes, Ryan Law, and Tim Youngs, became festival mavens too. Frederic Ambroisine became an accomplished maker of documentaries on classic and contemporary Asian cinema. With Udine’s Far East Film and New York’s Subway Cinema, enterprising fans launched their own superb festivals.

Academics respect knowledgeable people with vigorous opinions, so I found a lot to like in Hong Kong fandom. And since the phenomenon played an important part in bringing the movies to western attention, I devoted some pages in PHK to it. Wearing my historian’s hat, I wanted to trace how fans helped build up a climate of opinion that with surprising speed created a canon and gave stars and directors international fame.

There’s a personal side to it too. Otaku I was, otaku I remain. (Comics, detective stories, Jean Shepherd, Faulkner, certain TV shows, and chess as a teenager; movies came later.) As a professor, I turned late to studying fans, but once I started, it felt like coming home. “Fan” is short for fanatic, and outsiders speak of cult movies. Both terms suggest deviant, even dangerous religiosity. The analogy isn’t far-fetched. Fans pursue revelation, as often as the remote control will yield it up. This search gives their subculture its own strange sanctity. In their frenzies and ecstasies we can glimpse a quest for purity.

For a useful lineup of HK fan sites, go here. Nat Olsen maintains a gorgeous site on Hong Kong popular culture and street life from his base in the territory. Grady Hendrix is everywhere at once, but he’s often to be found at Subway Cinema, an enterprise he and Nat founded with their colleagues.

I’m inclined to think that most people who study popular culture have great fondness for the things they study. Many film academics are cinephiles (that is, lovers of the medium itself). Others confess to great admiration for films or directors they study. So there was a fan potential latent in many researchers. But some academics evidently hate the films they write about. One friend of mine, a meticulous scholar of film and culture, doesn’t seem to enjoy any movies at all. This attitude seems to be most common when the writer takes on the task of denouncing some ideological shortcomings in the movie–its covert political messages, or its portrayal of ethnic or sexual identity. How can you love a film that is criminal?

This is a complicated matter; I note in PHK that many Hong Kong films present questionable attitudes toward police procedure, women’s roles, and other topics of social importance. The problem is that by today’s standards, virtually every artwork ever made can be interpreted to be “complicit” (a favorite word), in league with some objectionable world view. Recall the critic who heard a passage in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony as “the throttling murderous rage of a rapist” (though she later modified her claim). By these standards, who shall ‘scape whipping? In a perfectly just society, will we have to stop watching Minnelli movies?

Granted, there are ways for the denunciatory critic to save a film that is she or he admires. It can be found to be secretly subversive, open to a “counter-reading.” Or it can be a work that openly challenges social norms, as with Surrealist cinema, gay/Queer cinema, or the work of Straub/ Huillet. Since the 1970s we have had films, mostly avant-garde ones, that seem to anticipate every possible line of objection that an academic critic might raise. But in any case you have to acknowledge that mass-production cinema is likely to call on prejudices and stereotypes. You don’t have to go as far as Roland Barthes, who noted that a “fecund” text needs a “shadow” of the “dominant ideology.” Nonetheless, our tasks as students of film, I think, is to recognize these factors but not to let them halt our efforts to answer our questions about other aspects of the films. As for love: Well, up to a point you can love a person despite his or her failings. Why not a film?

Lisa Odham Stokes and Tony Williams are other early HK aca-fans. Both have written for fanzines and have produced insightful books on Hong Kong films. See Stokes’ City on Fire: Hong Kong Cinema, with Michael Hoover, and Historical Dictionary of Hong Kong Cinema. A specialist in horror and action pictures, Tony has most recently published a study of Woo’s Bullet in the Head.

On fan culture, Henry Jenkins’ most comprehensive followup to Textual Poachers is Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. An important recent collection is Jonathan Gray’s Fandom: Identities and Communities in a Mediated World. Online fandom and its role in promoting a film are analyzed in Kristin’s book The Frodo Franchise (Chapter 6) and her blog here. Patton Oswalt’s newly published Zombie Spaceship Wasteland is in parts a memoir from within fandom.

Thanks to Shelly Kraicer, Yvonne Teh, Peter Rist, and Colin Geddes for help jogging my memory for this entry.

Fans all: Peter Rist, Shelly Kraicer, Erica Young, Colin Geddes, and Ann Gavaghan. Hong Kong Film Awards, 2000.

New Zealand is still Middle-earth: A summary of the Hobbit crisis

Richard Taylor during the October 20 anti-boycott march.

Kristin here:

Ordinarily I post about Peter Jackson’s Tolkien-adapted films on my other blog, The Frodo Franchise. But over the past five weeks a dramatic series of events has played out in New Zealand in regard to the Hobbit production. Those events tell us interesting things about today’s global filmmaking environment. As countries around the world create sophisticated filmmaking infrastructures, complete with post-production facilities, they are creating a competitive climate. Government agencies woo producers of big-budget films by offering tax rebates and other monetary and material incentives. Usually such negotiations go on behind closed doors, but the recent struggle over The Hobbit was played out more publicly.

Back in late September, the progress of Jackson’s project seemed slow. We Hobbit-watchers were mainly fretting over the lack of a greenlight for the two-part film “prequel” to The Lord of the Rings.

Of course, Tolkien’s LOTR (1954-55) was a sequel to The Hobbit (1937), but the films will have been made in reverse order. That’s due to MGM’s having the distribution rights back in 1995 when Peter Jackson went looking to use Tolkien’s novels to show off Weta Digital’s fancy new CGI abilities. Miramax bought the LOTR production and distribution rights and the Hobbit production rights.

Most of the news I was then blogging about related to MGM’s financial problems and how they would be resolved. Would Spyglass semi-merge with the ailing studio, convert its nearly $4 billion in debt into equity for its creditors, and bring it back into a position to uphold its half of the Hobbit co-production/co-distribution deal with New Line? Or would Carl Icahn push through his scheme to merge Lionsgate and MGM? The answer, by the way, came just this Friday, October 29, when the 100+ creditors voted to accept the Spyglass deal. I have been saying all along that the MGM situation was not the primary sticking point that was delaying the greenlight, even though most media reports and fan-site discussions assumed that it was. The greenlight having been given before this past week’s vote, I assume I was right. The real reason for the delay has not been revealed.

Meanwhile, other websites were speculating about casting rumors. Would Martin Freeman really play Bilbo, or were his other commitments going to interfere? (He will play Bilbo. Good choice, in my opinion. The man looks just like a hobbit.)

Then, on September 25 came the news that international actors’ unions were telling their members not to accept parts in The Hobbit. There was a boycott. The result was a maelstrom of events for the past five weeks or so. You may have heard about some of them. There were meetings and petitions. When Warner Bros. threatened to take the film to a different country, pro-Hobbit rallies followed. A visit by some high-up New Line and WB execs and lawyers to New Zealand led to hurried legislation to change the labor laws to reassure the studios that a strike wouldn’t happen. Finally, the government ended up raising the tax rebates for the production. Result: The Hobbit will be made in New Zealand after all. New Line, by the way, was folded into Warner Bros. by their parent company, Time Warner, after The Golden Compass failed at the box office. It remains a production unit but no longer does its own distribution, DVDs, etc.

The news that followed the launch of the boycott has come thick and fast, often involving misinformation. It was complicated, centering on an ambiguity in New Zealand labor laws as applied to actors and on a strange alliance between Kiwi and Australian unions. One of the biggest American film studios decided to use the occasion to demand more monetary incentives from the New Zealand government. I tried to keep up with all this and ended up posting 110 entries on the subject. (In this I was helped mightily by loyal readers who sent me links. Special thanks to eagle-eyed Paul Pereira.) That was out of 144 total entries from September 25 to now. There was plenty of other news to report. During all this, the MGM financial crisis was creeping toward its resolution, firm casting decisions were finally being announced, and the film finally got its greenlight. Whew!

For those who are interested in The Hobbit and the film industry in general but don’t want to slog through my blow-by-blow coverage, I’m offering a summary here, along with some thoughts on the implications of these events. Those who want the whole story can start with the link in the next paragraph and work your way forward. Obviously the links below don’t include all 110 entries.

In some cases the dates of my entries don’t mesh with those of the items I link to, given that New Zealand is one day ahead. I’ve indicated which side of the international dateline I’m talking about in cases where it matters.

September 25: Variety announces that the International Federation of Actors (an umbrella group of seven unions, including the Screen Actors Guild) is instructing its members not to accept roles in The Hobbit and to notify their union if they are offered one.

At that point, the film had not yet been greenlit, so it wasn’t clear how this would affect the production. The action against The Hobbit originated with the Australian union MEAA (Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance) and its director, Simon Whipp. Because relatively few actors in New Zealand are members of New Zealand Actors Equity, that small union is allied with the MEAA. The main goals of the union’s efforts were to secure residuals and job security for actors. The MEAA maintained that Ian McKellen (Gandalf), Cate Blanchett (Galadriel), and Hugo Weaving (Elrond) all supported the boycott; so far no evidence for this has been offered. Possibly they agreed to abide by it but were not in favor of it. Given the lack of a greenlight, none had been offered a role yet.

The main bone of contention has been a distinction made in labor laws in New Zealand. Actors are considered to be equivalent to contractors rather than employees, since they are hired on a temporary basis; it is illegal for a company to enter into negotiations with a union representing contractors. On that basis, Peter Jackson, who was first contacted in mid-August, refused to meet with the group. Besides, he isn’t the producer hiring the actors. Warner Bros., through New Line, is. As with all significant films, a separate production company, belonging to New Line, has been set up to make The Hobbit. It’s called 3 Foot 7. (The LOTR production company was 3 Foot 6, the average height of a hobbit being 3’6″.)

September 27. Peter Jackson responded angrily to the boycott, laying out the issues that would ultimately guide the New Zealand government’s response to the crisis:

“I can’t see beyond the ugly spectre of an Australian bully-boy using what he perceives as his weak Kiwi cousins to gain a foothold in this country’s film industry. They want greater  membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

“I feel growing anger at the way this tiny minority is endangering a project that hundreds of people have worked on over the last two years, and the thousands about to be employed for the next four years, [and] the hundreds of millions of Warner Brothers dollars that is about to be spent in our economy.”

Losing The Hobbit would leave New Zealand “humiliated on the world stage” and “Warners would take a financial hit that would cause other studios to steer clear of New Zealand”, Jackson said.

“If The Hobbit goes east [East Europe in fact], look forward to a long, dry, big-budget movie drought in this country. We have done better in recent years with attracting overseas movies and the Australians would like a greater slice of the pie, which begins with them using The Hobbit to gain control of our film industry.”

Various people and organizations in New Zealand soon line up behind one side or the other. Those siding with Jackson include Film New Zealand (which promotes filmmaking by foreign countries in New Zealand) and SPADA (the Screen Production and Development Association) and eventually the government. On the unions’ side is the Council of Trade Unions.

September 28. New Line, Warner Bros., and MGM weigh in with a statement that ups the ante. It dismisses the MEAA’s claims as “baseless and unfair to Peter Jackson” and continues:

To classify the production as “non-union” is inaccurate. The cast and crew are being engaged under collective bargaining agreements where applicable and we are mindful of the rights of those individuals pursuant to those agreements. And while we have previously worked with MEAA, an Australian union now seeking to represent actors in New Zealand, the fact remains that there cannot be any collective bargaining with MEAA on this New Zealand production, for to do so would expose the production to liability and sanctions under New Zealand law. This legal prohibition has been explained to MEAA. We are disappointed that MEAA has nonetheless continued to pursue this course of action.

Motion picture production requires the certainty that a production can reasonably proceed without disruption and it is our general policy to avoid filming in locations where there is potential for work force uncertainty or other forms of instability. As such, we are exploring all alternative options in order to protect our business interests.

Thus the specter of the production being not only delayed but also taken to another country is raised, and the implications of such a threat will gradually force the government to take measures to prevent that happening.

Peter Jackson also makes a statement to the Wellington newspaper that the Hobbit production might move to Eastern Europe. (The next day he reveals that WB is considering six countries for it.)

That night, a group of 200 actors met in Auckland, issuing a statement again asking the producers to meet for negotiations.

October 1. Jackson and WB voluntarily offer a form of residuals to Hobbit actors:

Sir Peter Jackson said New Zealand actors who did not belong to the United States-based Screen Actors’ Guild had never before received residuals – a form of profit participation. Warner Brothers had agreed to provide money for New Zealand actors to share in the proceeds from the Hobbit films.

It would be worth “very real money” to New Zealand actors. “We are proud that it’s being introduced on our movie. The level of residuals is better than a similar scheme in Canada, and is much the same as the UK residual scheme. It is not quite as much as the SAG rate.”

After much speculation, an announcement is made that Peter Jackson will definitely direct the film (which Guillermo del Toro had exited in May).

At about this time members of the filmmaking community begin campaigning actively against the boycott. An anti-boycott petition for New Zealand filmmakers and persons indirectly related to production to sign goes online; it ends with 3275 people having endorsed it.

October 15. The Hobbit is greenlit, but the possibility of moving the production out of New Zealand remains. Actors who have already been auditioned begin to be officially cast.

October 20. Actors Equity NZ is due to meet in Wellington. Richard Taylor (head of Weta Workshop) calls for a protest march. The actors’ meeting is called off due, the union says, to the “angry mob” that results. (Videos and photos posted online show a lengthy line of people walking through the streets in a peaceful fashion; that’s Richard talking to the press in the photo at the top. A person less likely to incite a “mob” to anger I cannot imagine.) An actors’ meeting scheduled for the next day in Auckland is also called off, putatively for the same reason, though no protest event had been planned there.

The turning-point day

October 21 (NZ). Jackson and his partner Fran Walsh issue a statement that implies that Warner Bros. has decided to move The Hobbit elsewhere:

“Next week Warners are coming down to New Zealand to make arrangements to move the production offshore. It appears we cannot make films in our own country even when substantial financing is available.”

Helen Kelly, president of the Council of Trade Unions calls Jackson “a spoiled little brat” on national television, helping turn the public against her cause.

Fran Walsh hints during a radio interview that WB might move The Hobbit to Pinewood Studios in England (where the Harry Potter films have been shot).

Prime Minister John Key says he hopes the production can be kept in New Zealand. Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee says he will meet with the WB delegation.

The international actors’ boycott against The Hobbit is called off.

October 21 (U.S.)/22 (NZ). WB is still considering moving the production, saying it has no guarantee that the actors will not go on strike. Key suggests that the labor law might be changed to provide that guarantee. The proposed legislation soon will become known as the “Hobbit bill.”

The Wall Street Journal suggests that a slight slip in the value of the New Zealand dollars against the American dollar is partly due to uncertainties about whether The Hobbit production will stay in the country.

WB announces the casting of Martin Freeman as Bilbo, plus several actors chosen as dwarves.

Bilbo Baggins by Tolkien and Martin Freeman, Bilbo-to-be.

A “positive rally” to convince WB to keep the production in New Zealand is announced. This eventually results in individual rallies in several cities and towns on October 25.

( U.S. time) Variety reports that unnamed sources within WB have said the studio is inclining toward keeping the production in New Zealand. This is the only hint of positive news from inside WB that comes out during the entire process.

Over the next few days, much finger-pointing takes place. Figures concerning the potential loss to NZ tourism if the film goes elsewhere are released. Helen Kelly apologizes for her “brat” remark.

October 25 (NZ). The WB delegation of 10 executives and lawyers arrive in Wellington. The pro-Hobbit rallies take place.

Pro-Hobbit rally in Wellington (Marty Melville/Getty Images).

October 26. News breaks that if The Hobbit is sent to another country, the post-production work (originally intended for Weta Digital and Park Road Post, companies belonging to Jackson and his colleagues) could take place outside New Zealand.

The WB delegation arrives at the prime minister’s residence in a fleet of silver BMWs. After the meeting ends, Key puts the chances of retaining the production at 50-50. He reiterates that the labor law might be changed.

Photo: NZPA

Presumably at this meeting, WB also puts forward a demand for higher tax rebates or other incentives; other countries it has been considering have more generous terms. Ireland has offered 28%, while New Zealand’s Large Budget Screen Production Grant scheme offers only 15%. This demand is not made public until later. During Key’s speech after the meeting, however, he mentions the possibility of higher incentives, but says the government cannot match 28%.

Editorials soon appear attacking the idea of changing a law at the behest of a foreign company.

The government’s deal with Warner Bros.

October 27. The New Zealand dollar again slips in relation to the American dollar, again attributed to uncertainty about The Hobbit.

Key and other government officials meet again with the WB delegation. The legal problem has been resolved to both sides’ satisfaction, but WB is holding out for higher incentives.

In the evening, Key announces that an agreement has been reached and the Hobbit production will stay in New Zealand:

As part of the deal to keep production of the “The Hobbit” in New Zealand, the government will introduce new legislation on Thursday to clarify the difference between an employee and a contractor, Mr. Key said during a news conference in Wellington, adding that the change would affect only the film industry.

In addition, Mr. Key said the country would offset $10 million of Warner’s marketing costs as the government agreed to a joint venture with the studio to promote New Zealand “on the world stage.”

He also announced an additional tax rebate for the films, saying Warner Brothers would be eligible for as much as $7.5 million extra per picture, depending on the success of the films. New Zealand already offers a 15 percent rebate on money spent on the production of major movies.

(The figure for the government’s contribution to marketing costs is later given as $13 million.)

October 28 (NZ). Peter Jackson returns to work on pre-production, which his spokesperson says has been delayed by five weeks as a result of the boycott. Principal photography is expected to begin in February, 2011, as had been announced when the film was greenlit. (The two parts are due out in December 2012 and December 2013.)

The Stone Street Studios. The huge soundstage built after LOTR is at the left; the former headquarters of 3 Foot 6 at the upper left.

In Parliament, a vote to rush through consideration of the “Hobbit bill” passes, and debate continues until 10 pm.

October 29 (NZ). The “Hobbit bill” passes in Parliament by a vote of 66 to 50, thus fulfilling the governments offer to WB and ensuring that The Hobbit would stay in New Zealand. It was known in advance that Key had enough votes going into the debate to carry the legislation.

It is revealed that James Cameron has been in talks with Weta to make the two sequels to Avatar in New Zealand. (Avatar itself was partly shot in New Zealand, with the bulk of the special effects being done there.) The timing has nothing to do with the Hobbit-boycott crisis. The two films are due to follow The Hobbit, with releases in December 2014 and December 2015.

October 30 (NZ). It is announced that the Hobbiton set on a farm outside Matamata will be built as a permanent fixture to act as a tourist attraction. (The same set, used for LOTR, was dismantled after filming, leaving only blank white facades where the hobbit-holes had been; nevertheless the farm has attracted thousands of tourists. See below.) Warner Bros. had been persuaded by the New Zealand government to permit this, though whether this was part of the agreement made with the studio’s delegation is not clear. I suspect it was.

It is also announced that the extended coverage of the 15% tax rebates specified in the “Hobbit bill” will apply to other films from abroad made in New Zealand—but only those with budgets of $150 million or more. (Presumably in New Zealand dollars.)

A remarkable outcome

In a way, it is amazing that a film production, even a huge one like The Hobbit, virtually guaranteed to be a pair of hits, could influence the law of a country–and make the legal process happen so quickly. Yet given the ways countries and even states within the USA compete with each other to offer monetary incentives to film productions, in another way it is intriguing that such pressure is not exercised by powerful studios more often. In most cases, a production company simply weighs the advantages and chooses a country to shoot in. Maybe countries get into bidding wars to lure productions or maybe they just submit their proposals and hope for the best. Certainly the six other countries considered briefly by WB were quick to jump in with information about what they could offer the Hobbit production.

In the case of Warner Bros. and The Hobbit, everyone initially assumed that the two parts would be filmed in New Zealand, just as LOTR had been. Yet the actors’ unions created an opportunity. The boycott gave Warner Bros. the excuse to threaten to pull the film out of New Zealand. Meeting with top government officials, WB executives demanded assurance that a strike would not occur–and oh, by the way, we need higher monetary incentives. As a result, a compromise was reached, the incentives were expanded, and there was a happy ending for the many hundreds of filmmakers of various stripes who would otherwise have been out of work.

Although there is considerable bitterness among the actors’ union members and those who supported their efforts, many in New Zealand see the tactics of the MEAA as extremely misguided. Kiwi Jonathan King, the director of the comic horror film Black Sheep, sums it up:

But this was all precipitated by an equal or greater attack on our sovereignty: an aggressive action by an Australian-based union taken in the name of a number of our local actors, backed by the international acting unions (but not supported by a majority of NZ film workers), targeting The Hobbit, but with a view to establishing a ’standard’ contract across our whole industry. While the actors’ ambitions may be reasonable (though I’m not convinced they are in our tiny market and in these times of an embattled film business), the tactic of trying to leverage an attack on this huge production at its most precarious point to gain advantage over an entire industry was grotesquely cynical and heavy-handed, and, as I say, driven out of Australia. Imagine SAG dictating to Canadian producers how they may or may not make Canadian films!

Whether the deal was unwisely caused by a pushy Australian union is a matter for debate. Whether the New Zealand government unreasonably bowed down to a big American studio is as well. But the deal that the two parties reached is a remarkable one, perhaps indicative of the way the film industry works in this day of global filmmaking.

Warner Bros. gets more money and a more stable labor situation. What’s in it for New Zealand? First, the incentives for large-budget films from abroad to be made in the country are raised. This comes not through an increase in the tax-rebate rate but an expansion of what it covers:

The Government revealed this week that the new rules would mean up to $20 million in extra money for Warner Bros via tax rebates, on top of the estimated $50 million to $60 million under the old rules.

While the details of the Large Budget Screen Production Grant remain under wraps, Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee said it would effectively increase the incentives for large productions to come to New Zealand.

The grant is a 15 per cent tax rebate available on eligible domestic spending. At the moment a production could claim the rebate on screen development and pre-production spending, or post-production and visual effects spending, but not both.

If the Government allowed both aspects to be eligible, it would be a large carrot to dangle in front of movie studios.

Mr Brownlee was giving little away yesterday but said the broader rules would apply only to productions worth more than US$150 million ($200 million).

It would bridge the gap “in a small way” between what New Zealand offered and what other countries could offer.

During this period, it was claimed that WB had already spent around $100 million on pre-production on The Hobbit, which has been going on for well over a year now. That figure presumably is in New Zealand currency.

There are some in New Zealand who oppose “taxpayer dollars” going to Warner Bros. As has been pointed out–though apparently not absorbed by a lot of people–Warner Bros. will spend a lot of money in New Zealand and get some of it back. The money wouldn’t be in the government’s coffers if the film weren’t made in the country. It’s not tax-payers’ money that could somehow be spent on something else if the production went abroad.

Another advantage for the country is the permanent Hobbiton set, which will no doubt increase tourism. There are fans who have already taken two or three tours of LOTR locations and will no doubt start saving up to take another.

One item that didn’t get noticed much during the deluge of news is that one of the two parts will have its world premiere in New Zealand. That’ll probably happen in the wonderful and historic Embassy theater, which was refurbished for the world premiere of The Return of the King. It was estimated that the influx of tourists and journalists for that event brought NZ$7 million to the city of Wellington. About $25 million in free publicity was provided by the international media coverage.

The Embassy in October 2003, being prepared for the Return of the King world premiere.

The deal also essentially makes the government of New Zealand into a brand partner with New Line to provide mutual publicity for The Hobbit. As I describe in Chapter 10 of The Frodo Franchise, the government used LOTR to “rebrand” the entire country. It worked spectacularly well and had a ripple effect through many sectors of society outside filmmaking. The country came to be known more for its beauty, its creativity, and its technical innovations than for its 40 million sheep. Now in the deal over The Hobbit, the government has committed to providing NZ$13 million for WB’s publicity campaign. But the money will also go to draw business and tourists. As TVNZ reported:

But the Prime Minister says for the other $13 million in marketing subsidies, the country’s tourism industry gets plenty in return.

“Warner Brothers has never done this before so they were reluctant participants, but we argued strongly,” Key said.

Every DVD and download of The Hobbit will also feature a Jackson-directed video promoting New Zealand as a tourist and filmmaking destination.

Graeme Mason of the New Zealand Film Commission says the promotional video will be invaluable.

“As someone who’s worked internationally for most of my life, you can’t quantify how much that is worth. That’s advertising you simply could not buy.”

If the first Hobbit film is as popular as the last Lord of the Rings movie, the promotional video could feature on 50 million DVDs.

Suzanne Carter of Tourism New Zealand agrees having The Hobbit production here is a dream come true.

“The opportunity to showcase New Zealand internationally both on the screen and now in living rooms around the world is a dream come true,” Carter said.

Marketing expert Paul Sinclair says the $13 million subsidy works out at 26 cents a DVD.

“It’s a bargain. It is gold literally for New Zealand, for brand New Zealand,” he said.

It’s not clear how the promotional partnership will be handled. There was a similar, if smaller partnership when LOTR was made. New Line permitted Investment New Zealand, Tourism New Zealand, the New Zealand Film Commission, and Film New Zealand to use the phrase, “New Zealand, Home of Middle-earth” without paying a licensing fee. (Air New Zealand was an actual brand partner during the LOTR years.) But for the government to actually underwrite the studio’s promotional campaign may entail more. That deal is more like the traditional brand partnership, where the partner agrees to pay for a certain amount of publicity costs in exchange for the right to use motifs from the film in its advertising. Has a whole country ever brand-partnered a film? I can’t think of one.

In my book I wrote that LOTR “can fairly claim to be one of the most historically significant films ever made.” That’s partly why I wrote the book, to trace its influences in almost every aspect of film making, marketing, and merchandising–as well as its impact on the tiny New Zealand film industry that existed before the trilogy came there. Years later, I still think that my claim about the trilogy’s influences was right. When an obscure art film from Chile or Iran carries a credit for digital color grading, it shows that the procedure, pioneered for LOTR, has become nearly ubiquitous. There are many other examples. The troubled lead-up to The Hobbit‘s production and the solutions found to its problems suggest that it will carry on in its predecessor’s fashion, having long-term consequences beyond boosting Warner Bros.’ bottom line. It will be interesting to see if other big studios announce they will film in one country and then find ways of maneuvering better terms by threatening to leave–or by actually leaving.

From Worldwide Hippies

Archie types meet archetypes

DB here:

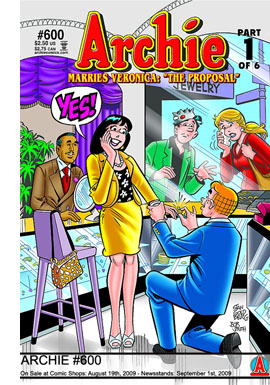

You heard about it in May, but the proof arrived in comic-book stores just lately. Archie has proposed to Veronica. At the midpoint of issue #600, he goes down on bended knee in Spiffany’s and pops the question.

The rest of the issue is devoted to other characters’ reactions. Mr. Lodge, at first outraged, says that Archie must come to work for him. Jughead is judgmental but ultimately forgiving, in his droopy-eyed way. Archie’s parents are delighted. Even Reggie shows a dash of gallantry. All of Riverdale is buzzing, but over the joyous news hangs a cloud of worry.

What about Betty?

She accidentally witnessed the proposal and at first broke down uncontrollably. Later we see her as surprisingly stoic—until she gets a phone call from Veronica (cruel? compassionate?) asking her to be maid of honor. The installment ends with Betty forlornly telling Veronica, “You—you won.”

She accidentally witnessed the proposal and at first broke down uncontrollably. Later we see her as surprisingly stoic—until she gets a phone call from Veronica (cruel? compassionate?) asking her to be maid of honor. The installment ends with Betty forlornly telling Veronica, “You—you won.”

DON’T MISS THE STORY THE WORLD HAS BEEN WAITING MORE THAN 60 YEARS TO READ! we read on the last page. Part Two, “The Wedding,” will follow next month, with four more parts after that. Archie Comics Publications has promised future episodes in which Arch and Ronnie procreate.

On her blog, Veronica is more or less gloating. Betty seems to have come to terms. On her blog she wrote:

What can I say? It is so sad.

Xoxoxoxo

Bets

Still, Betty suggests she feels the sting of mockery, and we can expect more pain in her future. Fan reaction has been far more furious. Mackenzie writes:

ARCHIE SHOULD HAVE MARRIED BETTY!! I MAY ONLY BE 10 BUT HE MUST MARRY BETTY. HOW COULD HE BE SO STUPID. I THINK HE IS TRYING TO BE RICH. POOR POOR BETTY.

One devotee, proprietor of a comics shop, sold his copy of Archie #1 in protest, and the $38,000 it fetched has not assuaged his discontent.

Like all boys I knew, I preferred Betty to Veronica. So I join in the mourning, and not just because it promises a sad married life for Arch. This upheaval threatens to destroy the Riverdale we loved. Betty working in a shop in Manhattan, Reggie in Atlanta selling cars, Moose running a burger joint in Staten Island: All dismally realistic options for today’s grads, but that’s small consolation. And what about Miss Grundy and Mr. Weatherbee and Pop Tate? Have we no cares for them?

In this crisis, panic is understandable. Yet I believe that older heads have a duty to assume leadership and calm the younger, more tempestuous spirits. A careful reading—well, okay, just a simple reading—of fateful issue #600 gives us a glimmer of hope. It also illustrates how a very old narrative convention can be revamped in popular culture.

A man of many parts

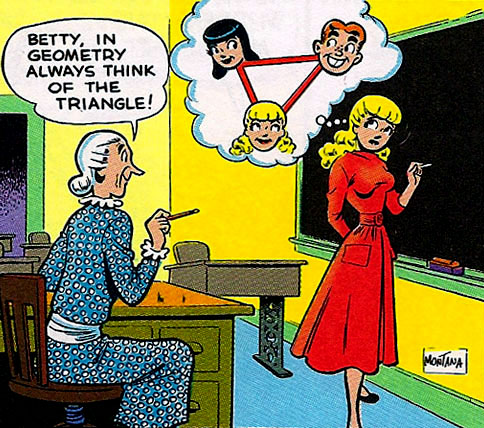

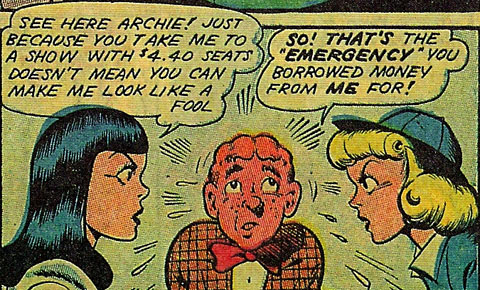

My acquaintance with the Archie series goes back to the mid-1950s. The books had already moved from the 1940s caricatural portrayal of Riverdale’s residents (above) to a more streamlined look reminiscent of Hergé’s clear line style.

Eventually the visual style would become still more minimal, offering little shading or detail and relying on a smaller repertoire of facial types, expressions, and gestures.

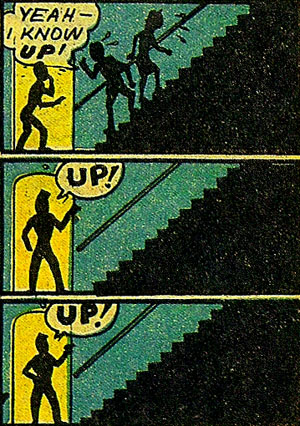

What I didn’t know then was that the first series artist, Bob Montana, was a gifted storyteller who made shrewd use of the graphic shorthand that adds so much to comics. In “Double Date” (#7, 1944), the issue that established the Eternal Triangle, Archie has wound up taking both girls to the same play. Of course neither knows that her rival is there. Archie escorts each one into the theatre and then races between Veronica in the orchestra and Betty in a distant balcony. Montana crisply renders Archie and Betty climbing past ushers to the nosebleed seats. Interestingly, this stack of panels must be read from bottom to top.

Archie races downstairs to check in with Veronica, and the swirl of his descent wraps inside the circular frame like baseball stitching. A horizontal stripe using the vertical panels’ green tone demarcates the movement between floors.

Once Betty discovers Archie’s perfidy, she stalks off, and Montana combines the two earlier framings, circle and square, yellow and green, in showing their zigzag descent.

Morover, in a story based on symmetries, each girl’s discovery of Archie’s perfidy is given a canted deep-focus framing that Orson Welles might have liked.

I wish I could find this sort of pictorial ingenuity in Archie #600, but like most of the 1950s and 1960s entries I’ve reread, this one is all about story. And fairly comedy-free story at that. Years ago boys like me followed Archie, but I suspect that now the prime readership is tween girls, so the romance-based pathos of Betty’s suffering may hit its target audience. Still, what the issue lacks in graphic sophistication may be made up for in its use of a narrative device that has become salient in popular culture, including movies.

The road not taken

In Poetics of Cinema I included an article called “Film Futures.” Originally a paper for a 2001 conference, it sought to analyze an emerging trend in filmic storytelling that has its roots in folktales and popular literature. That is the device of the hypothetical future.

The most famous example in literature probably remains A Christmas Carol, in which a ghost confronts Scrooge with a harrowing vision of his fate if he does not mend his ways. Dickens’ story showed how an alternative-future plot could be motivated by the supernatural, still a common way to show an alternative course of events. Later writers would rely on hallucination or science-fiction premises, such as time travel that allows a return to a point of choice. At various periods, films have drawn on these principles, from The Love of Sunya (1927) to Back to the Future II (1989). There are unmotivated instances of alternative futures as well in plays by J. B. Priestley, novels by Allen Drury, and art-comics by Chris Ware.

The central premise of this device goes back further. Many folktales from various cultures present brothers halting at a crossroads. Each brother picks a different road, and the plot is built out of their contrasting fates. Sometimes each road is marked with an enigmatic prediction about what will happen further along. O. Henry picked up the motif in his audacious 1903 story “Roads of Destiny,” which presents a single protagonist hypothetically taking each path in turn. His fate catches up with him whether he chooses one road or the other or just returns home.

In my essay I explore how the idea of forking-path futures was revived on film in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance (1987), Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1998), Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors (1998), and Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be No. 1 (1997). The essay aims to show how this plot formula, so apparently free-form, relies on a set of firm conventions. For example, in principle the character might have an indefinitely large set of fates, but the first parallel universe presented sets the premises–characters, issues, and the like–that will be varied in the other alternatives. The conventions, I argue, allow the filmmakers to establish a surprisingly narrow set of options, but this trains us to notice fine-grained differences.

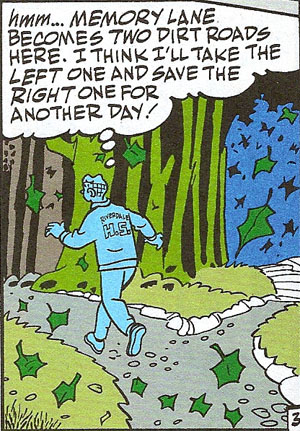

Archie’s proposal to Veronica, we learn, takes place in just such an alternative future. The present time of the narrative in issue #600 is the night of Archie’s last high-school rock concert. But Archie, facing the need to apply to college, goes out for a walk. He arrives at Memory Lane. Instead of walking down the lane—that is, into the past—he walks in the opposite direction, into the future. Suddenly he’s encountering his parents on the night of his graduation from college. A title intervenes.

Stop the presses! Did Mr. Andrews say Archie was graduating from COLLEGE? What happened to HIGH SCHOOL? By walking up Memory Lane, has Archie walked into his own FUTURE?

In short, yes. Everything we encounter from here on takes place four years after the initial scenes. Archie’s proposal and Betty’s fraught response are set in the future, as presumably will be the wedding and the eventual birth of Archie’s and Veronica’s children.

Already, then, there’s a way to set things right in Riverdale. That’s to change the future, to treat it as only one possible line of action. And in taking Archie up Memory Lane our plotters have relied on the folk archetype I’ve just mentioned.

This is quite a tease. The motif of pairs that we saw in “Double Date” returns with a vengeance. (A propos, it’s announced on the Internets that Archie and Veronica will have twins.) More important, the presence of a second road suggests that Archie has another future, one in which he doesn’t propose to Veronica. This device allows Arch to retreat at any time back along Memory Lane, and then back to the choice-point. Maybe there he will take the “right” road and eventually choose Betty? And is it an accident that the road on the left, drawing him toward marriage to Veronica, takes him into a gloomy forest, while the other one, paved in white stones, leads to a blue sky?

So the narrative leaves an escape hatch: Arch could retreat to this fork. Or he might even decide that he doesn’t want to know his other fate. In which case he could go back down Memory Lane, pass the point he entered, go further back in time, and return to his high school days, putting college—Archie a history major?—into a fuzzy future. But plot it yourself. Or follow the developments through the next five months.

Archie #600 may be offering its young readers a tutorial in understanding alternative-future plots–hence the redundant explanations in the panel quoted above. Historically,though, it’s behind the curve; the recent vogue for forking-path plots seems to have passed. Why did such plots become more common around the turn of the last century? We might invoke Steven Johnson’s argument, in Everything Bad Is Good for You, that audiences got smarter, so narratives became more complicated. Other students of “puzzle films” want to trace such narrative hijinks to postmodernity; no surprise there.

My own explanations can be found in the essay, where I look to factors like modern media’s intense demand for novelty, the quick spread (and exhaustion) of narrative innovations, and most specifically the conventions of storytelling established in things like branching-tree video games and the Choose Your Own Adventure books. Whatever the causes, at any point in history, very old narrative techniques lie waiting to be dusted off and given a fresh polish in the popular arts. Even Archie, going on seventy and still technically a bachelor, can get a makeover.

Archie Comic Publications has its website here. The story “Double Date” is reprinted in Charles Phillips, Archie: His First 50 Years (New York: Artabras, 1991), 34-44. An early published version of my “Film Futures” piece is here via library access, but the revised and expanded version in Poetics of Cinema is preferable. The “choice-of-roads” device is N122.0.1 in Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk Literature. It is discussed in Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature: A Handbook, ed. Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2005), 333-341.

P.S. 14 August 2010: Archie’s multiple futures were only the beginning of a major rebranding effort.

P.P.S. 23 January 2017: Turns out that Forking-Paths Archie was a turning-point for both the hero and the company. See this fascinating Vulture story.