Archive for the 'Fans and fandom' Category

Now leaving from platform 1

From a Facebook post by Tahereh

To all my friends:

What can I reply to Hossein? He’s pursuing me so avidly, but you know he isnt really a prime catch. No education, no house. If it werent for the earthquake, I wouldnt give him a second look. But he does interest me a little—he’s made me lose track of my lines so many times!

Oh no, now he’s chasing me across the field. What can I tell him? BRB!

DB here:

Many people in the film industry hold media studies in disdain, and often the feeling is mutual. Filmmakers recoil from the abstrusities of Big Theory, and academics often consider filmmakers gearheads (just before wagging their fingers and warning us about the Intentional Fallacy). But scholars like Rick Altman, John Caldwell, Janet Staiger, Kristin, and me, and younger folks like Patrick Keating and Ben Wright have been trying to study filmmakers’ creative choices in concrete ways. Some of us even ask filmmakers what they were trying to do.

So it’s heartening to see movement in the other direction. For quite a while academically trained filmmakers like James Schamus and Todd Haynes have brought ideas from their university studies into their films. Recently Reid Rosefelt composed an enlightening blog entry on Kathryn Bigelow’s intellectual side. Now some terms and ideas are being spread even more widely across the industry.

For example, in a recent Entertainment Weekly story about why women viewers like horror, we read:

One of the most consistent tropes of the genre is the character whom filmmakers call ”the final girl” — the survivor.

Actually, it was Carol Clover, scholar of horror movies and Scandinavian epics, who came up with the “final girl” nickname in her book Men, Women, and Chainsaws. Going back to the EW sentence, you notice that academics helped popularize the term genre too, which you seldom find in Hollywood’s patter before the 1970s. And the very word trope smells of classrooms and chalkdust.

Even more striking is a recent Variety article entitled, “Transmedia Storytelling Is Future of Biz.” Peter Caranicas explains that it involves “developing a piece of intellectual property across multiple media platforms.” The Star Wars franchise is the major modern instance, as Caranicas explains.

What Lucas did went several steps beyond old-style character licensing and brand extensions. He created a unified body of work with an extensive backstory and mythology, and he determinedly guarded its canon [another academic term—DB] while simultaneously opening up peripheral parts of his universe to exploration by other contributors.

One of my former students assures me that Kristin and I used the term “transmedia” back in the 1990s, but we have no memory of doing so. More relevantly, Liz Rosenthal reminds us that Peter Greenaway was pushing the concept in 1993. “If the cinema intends to survive, it has to make a pact and a relationship with concepts of interactivity and it has to see itself as only part of a multimedia cultural adventure.”

In any case, the person who brought the concept of transmedia storytelling to the forefront of media studies, and thus industry parlance, was another Wisconsin student, Henry Jenkins. Henry has made the concept part of his broader research into how modern media connect with audiences, particularly fan audiences. In his 1992 essay on Twin Peaks, he was already exploring how fans used the still-emerging internet to respond to a range of ancillary texts around Lynch’s TV series. You can get a quick acquaintance with his most recent ideas in this 2007 blog essay. For me, his argument emerged most vividly in a talk he gave at Madison some years ago. The lecture became the chapter “Searching for the Origami Unicorn” in his book Convergence Culture. For his more recent thinking, you can check his current course syllabus, which includes reading and web references, in the 11 August entry here.

The platform-shifting that Caranicas describes is planned and executed at the creative end, moving the story world calculatedly across media. These, dubbed by Jenkins “commercial extensions,” differ from “grassroots extensions,” which are created by audience members without the permission, or even the knowledge, of the creators. The commercial extensions are what I’ll be considering here.

From aggregator Movie MMORPG:

Welcome to a sophisticated world teetering on the edge of decadence. Get hammered on Italian cocktails. Fight your way out of a hospital jammed with nymphos. Cheat on your wife. Seduce a married man. Wander through the streets and stare at gushing water. Have you got what it takes to survive a day in LaNotteCity? You’ll get hooked, since the endgame is always inconclusive!

As it’s currently discussed, transmedia storytelling has two uncontroversial components and one rare but intriguing one.

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

First, the term implies that a story is spread among a series of discrete “texts.” This “hypernarrative” idea was explored with taxonomic zeal by Gérard Genette in his 1982 book Palimpsests. His taxonomy of storytelling is worth considering a little here because he anticipated several possibilities we’re seeing now. Many of his categories have parallels in cinema, but I’ll stick to his domain, literature.

Novels and short stories feed off other novels and short stories. Obvious examples are parodies, pastiches, sequels, and continuations (sequels not written by the original author). Genette also considers what he calls the “transposition,” a very roomy category that’s of particular interest to us.

Transpositions are things like translations, rewritings, and literary adaptations, as when a novel becomes a play. A transposition also occurs when the original text is pruned or compressed, as in abridged versions of Don Quixote or Moby-Dick. At the other quantitative extreme is what Genette calls augmentation. Here, the derivative work expands the original, either in style (three sentences replace one) or narrative material (extra scenes or plots).

Yet another sort of transposition occurs when the story events in the original are rendered through alternative literary techniques. Charles Lamb retells Ulysses’ adventures in a different order than Homer does, and someone could rewrite the events of Madame Bovary in first person, from Charles’ point of view. When Genette was writing, he had to reach for some esoteric examples, but nowadays we have others. Alice Randall’s The Wind Done Gone (2001) retells Gone with the Wind from the point of view of a slave on Tara. The novel Wicked is a large-scale example, as is Tom Stoppard’s Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead.

All these examples of hypernarrative operate within a single medium. The second condition of transmedia storytelling is, of course, that it crosses media. Genette considers drama and written literature to be all part of the same medium, but if you don’t, then novels turned into plays, like Les Miserables, would count as transfers across media.

In this sense, transmedia storytelling is very, very old. The Bible, the Homeric epics, the Bhagvad-gita, and many other classic stories have been rendered in plays and the visual arts across centuries. There are paintings portraying episodes in mythology and Shakespeare plays. More recently, film, radio, and television have created their own versions of literary or dramatic or operatic works. The whole area of what we now call adaptation is a matter of stories passed among media.

What makes this traditional idea sexy? I think it’s a third, less common component that Henry has spotlighted. Some transmedia narratives create a more complex overall experience than that provided by any text alone. This can be accomplished by spreading characters and plot twists among the different texts. If you haven’t tracked the story world on different platforms, you have an imperfect grasp of it.

I can follow Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories well without seeing The Seven Percent Solution or The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. These pastiches/continuations are clearly side excursions, enjoyable or not in themselves and perhaps illuminating some aspects of the original tales. But according to Henry, we can’t appreciate the Matrix trilogy unless we understand that key story events have taken place in the videogame, the comic books, and the short films gathered in The Animatrix. The Kid in The Matrix Reloaded makes cryptic reference to finding Neo by fate, but only those who have watched the short devoted to him knows what that means. If Sherlock pastiches are parasites, the texts around The Matrix exist in symbiosis, giving as much as they take.

This strategy differentiates the new transmedia storytelling from your typical franchise. In most film franchises, the same characters play out their fixed roles in different movies, or comic books, or TV shows. You need not consume all to understand one. But Henry envisages the possibility of creating a whole that is greater than its parts, a vast narrative experience that doesn’t end when the book’s last page is turned or the theatre lights come up. His idea seems to be echoed in Will Wright’s suggestion:

It’s a fractal deployment of intellectual property. Instead of picking one format, you’re designing for one mega-platform. . . . We’ve been talking about this kind of synergy for years, but it’s finally happening.

Stimulating as this prospect is, it remains rare. The Matrix is perhaps the best example, but Henry suggests that it’s also an extreme instance: “For the casual consumer, The Matrix asked too much. For the hard-core fan, it provided too little” (p. 126). More common is a Genette-style transposition, in which the core text—usually the movie—is given offshoots and roundabouts that lead back to it. As I understand it, the Star Wars novels operate under the injunction that although they can take a story situation as the basis for a new plot, in the end that plot has to leave the films’ story arc unchanged. Similarly, websites with puzzles, games, clues, and other supplementary material tend to be subordinate to the film, planting hints and foreshadowings (The Blair Witch Project, Memento). Alternatively, the A. I. website provided a largely independent story world that impinged on the movie’s action only slightly.

The “immersive” ancillaries seem on the whole designed less to complete or complicate the film than to cement loyalty to the property, and even recruit fans to participate in marketing. It’s enhanced synergy, upgraded brand loyalty.

For the most part Hollywood is thinking pragmatically, adopting Lucas’ strategy of spinning off ancillaries in ways that respect the hardcore fans’ appreciation of the esoterica in the property. Caranicas quotes Jeff Gomez, an entrepreneur in transmedia storytelling, saying that for most of his clients “we make sure the universe of the film maintains its integrity as it’s expanded and implemented across multiple platforms.” It would seem to be a strategy of expanding and enriching fan following, and consequent purchases.

As best I can tell, then, in borrowing this academic idea, the industry is taking the radical edge off. But is that surprising?

Excerpt from www.ballsup.net

What a bloody week. Just now had a chance to update things. Fact is, it’s me last post. Luckily I let that cellphone drop and grabbed the satchel just before it fell into the Thames. Me and the crew are now packing for Bimini, ready for living large but in a rush becuz Big Chris may be looking for us. Hang on, must upload now, someone’s knocking at me d

Henry’s chapter in Convergence Culture grants that “relatively few, if any, franchises achieve the full aesthetic potential of transmedia storytelling—yet” (p. 97). Perhaps that hopeful “yet” will be fulfilled outside Hollywood? In the realm of the avant-garde, Matthew Barney has elaborated his own private mythology, dispersed among artifacts and hard-to-see films. In this he followed Joseph Beuys and Salvador Dalí. But you could argue that these artists really weren’t telling an overarching story. They were creating secular cults, full of arcana that only the pious initiates of Gallery Culture could grasp.

What about something more accessible? This month in Filmmaker magazine, Lance Weiler has suggested that indie filmmakers embrace the concept of transmedia storytelling (though he doesn’t use the term). Weiler argues that the explosion of digital technology has so transformed narrative that the filmmaker has to keep up. Instead of creating a script, with its genre formulas and three-act layout, the filmmaker should generate a bible, which plots an ensemble of characters and events that spills across film, websites, mobile communication, Twitter, gaming, and other platforms. The filmmaker designs “timelines, interaction trees, and flow charts” as well as “story bridges that provide seamless flow across devices and screens.”

Weiler doesn’t offer any specific examples apart from his Head Trauma, a horror feature accompanied by an alternate reality game that involved mobile and online access. You can watch his account of the “evolution of storytelling” here, where he and Ted Hope speculate about transmedia storytelling as offering economic help to filmmakers, reclaiming authorship from corporations, and promoting new relations with the audience.

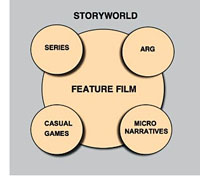

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

Hope and Weiler raise many fascinating questions about the prospects for multiplatform storytelling. At times, though, it seems that they accept the studio strategy of putting the film at the center of a multimedia ensemble. The diagram accompanying Weiler’s article illustrates that. It’s hard to think outside the franchise model, even if we want to denounce Hollywood for being stuck in an outdated commitment to the theatrical feature as foundational “content.”

We should welcome experimentation, so I wish Hope, Weiler, and other creators well. But I think we ought to recognize some problems with expanding story worlds in these directions.

For one thing, most Hollywood and indie films aren’t particularly good. Perhaps it’s best to let most storyworlds molder away. Does every horror movie need a zigzag trail of web pages? Do you want a diary of Daredevil’s down time? Do you want to look at the Flickr page of the family in Little Miss Sunshine? Do you want to receive Tweets from Juno? Pursued to the max, transmedia storytelling could be as alternately dull and maddening as your own life.

Sure, somebody might go for it. Kristin points out, though, that people who would be motivated to follow up on all the transmedia bits of a spreadeagled narrative are people who would identify themselves as part of a fandom. There aren’t that many films/franchises that generate profoundly devoted fans on a large scale: The Matrix, Twilight, Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, Star Wars, Star Trek, maybe The Prisoner. These items are a tiny portion of the total number of films and TV series produced. It’s hard to imagine an ordinary feature, let alone an independent film, being able to motivate people to track down all these tributary narratives. There could be a lot of expensive flops if people tried to promote such things.

Consider a deeper point. Transmedia storytelling in the radical sense is posited as an active, participatory experience. Henry suggests that fans will race home from the multiplex to study up on iconography in The Matrix. Weiler’s article is accompanied by a hierarchy that lists “layers of interactivity.” The most superficial is “Passive Viewing,” defined as “Sit back and watch.” (Here Weiler parts company with Henry, who doesn’t consider ordinary viewing passive.) Further along are layers involving social networking, playing games, discussing or interacting with characters, finding hidden content, and even creating elements of the story world.

But it seems to me that film viewing is already an active, participatory experience. It requires attention, a degree of concentration, memory, anticipation, and a host of story-understanding skills. Even the simplest story gears up our minds. We may not notice this happening because our skills are so well-practiced; but skills they are. More complicated stories demand that we play a sort of mental game with the film. Trying to guess Hitchcock or Buñuel’s next twist can engross you deeply. And the very genre of puzzle films trades on brain strain, demanding that the film be watched many times (buy the DVD) for its narrational stratagems to be exposed. Films are interactive in the way a board game is: each move blocks certain possibilities, another anticipates what you’re going to do (mentally).

Moreover, how the ancillary texts add to the film is a crucial matter. No narrative is absolutely complete; the whole of any tale is never told. At the least, some intervals of time go missing, characters drift in and out of our ken, and things happen offscreen. Henry Jenkins suggests that gaps in the core text can be filled by the ancillary texts generated by fan fiction or the creators. But many films thrive by virtue of their gaps. In Psycho, just when did Marion decide to steal the bank’s money? There are the open endings, which leave the story action suspended. There are the uncertainties about motivation. In Anatomy of a Murder, did Lieutenant Manion kill his wife’s rapist in cold blood? Likewise, being locked to a certain character’s range of knowledge is the source of powerful emotional effects. We want to make the discoveries along with the character, be he Philip Marlowe or Travis Bickle.

The human imagination abhors a vacuum, I suppose, but many art works exploit that impulse by letting us play with alternative hypotheses about causes and outcomes. We don’t need the creators to close those hypotheses down. Indeed, you can argue that one of the contributions of independent film has been the possibility of pushing the audience toward accepting plots that don’t fit clear-cut norms. That innovation shrinks if we can run home to get background material online. By following the franchise logic, indie films risk giving up mystery.

At this point someone usually says that interactive storytelling allows the filmmaker to surrender some control to the viewer, who is empowered to choose her own adventure. This notion is worth a long blog entry in itself, so I’ll simply assert without proof: Storytelling is crucially all about control. It sometimes obliges the viewer to take adventures she could not imagine. Storytelling is artistic tyranny, and not always benevolent.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

Another drawback to shifting a story among platforms: art works gain strength by having firm boundaries. A movie’s opening deserves to be treated as a distinct portal, a privileged point of access, a punctual moment at which we can take a breath and plunge into the story world. Likewise, the closing ought to be palpable, even if it’s a diminuendo or an unresolved chord. The special thrill of beginning and ending can be vitiated if we come to see the first shots as just continuations of the webisode, and closing images as something to be stitched to more stuff unfolding online. There’s a reason that pictures have frames.

In between opening and closing, the order in which we get story information is crucial to our experience of the story world. Suspense, curiosity, surprise, and concern for characters—all are created by the sequencing of story action programmed into the movie. It’s significant, I think, that proponents of hardcore multiplatform storytelling don’t tend to describe the ups and downs of that experience across the narrative. The meanderings of multimedia browsing can’t be described with the confidence we can ascribe to a film’s developing organization. Facing multiple points of access, no two consumers are likely to encounter story information in the same order. If I start a novel at chapter one, and you start it at chapter ten, we simply haven’t experienced the art work the same way. This isn’t to say, of course, that each of us has an identical experience of a movie. It’s just that our individual experiences of the film overlap to an extent that allows us to talk about the patterning of the story under our eyes.

In correspondence with me, Henry suggests that transmedia storytelling may work best with television because of the serialized format; different people hop aboard at different points. I’d add that television’s installment-based storytelling, operating in the lived time of the audience, allows time for viewers to explore or create media offshoots. The installment-based nature of serial TV poses intriguing aesthetic problems of continuity, coherence, and memory. (See Jason Mittell’s essay on this matter.) For films, however, which are typically designed to be consumed in one sitting, multiple points of entry will tend to make plot patterns less clearly profiled.

If transmedia storytelling is difficult to apprehend for the viewer, it also makes critical analysis and evaluation much more difficult. How might we analyze overarching patterns of multiplatform plotting in The Matrix? True, one can itemize the inputs and decipher the citations, but it’s very hard to show how they work together, how they unfold, what it all adds up to—except to note that different people will encounter information bits at different times and with different states of knowledge.

Gap-filling isn’t the only rationale for spreading the story across platforms, of course. Parallel worlds can be built, secondary characters can be promoted, the story can be presented through a minor character’s eyes. If these ancillary stories become not parasitic but symbiotic, we expect them to engage us on their own terms, and this requires creativity of an extraordinarily high order.

Henry Jenkins suggests that for big-budget projects, this means finding unusually gifted collaborators. In the indie sector, the obstacles are even more considerable. Whether the result is Wendy and Lucy or Goodbye Solo, creating a first-rate feature-length movie takes tremendous talent, sweat, and resourcefulness. It is immensely harder to create a story universe that sustains the same intensity and quality across platforms. True, you can sprinkle clues and cryptic references among websites and YouTube shorts. The formulas of genre (horror, mystery) help you generate shock effects and mystification in teaser trailers. Appeal to stock characterization helps you mount a “realistic” Second Life life. But building a vast, sturdy world teeming with distinctive characters, unpredictable plotting, and human resonance is an immense task.

We await our multimedia Balzac. In the meantime, maybe indie filmmakers should settle for trying to be Chekhov.

http://tinyurl.com/scarkiller

Debbie, sorry 2 hav left SOOOO suddenlike. am @ Gila flats = cactus + varmnts. LOL with Blankethead!!! :-/

Uncl Ethan

Thanks to Henry Jenkins for comments on this entry. He recommends that interested readers have a look at Geoffrey Long’s 2007 MA thesis on the Jim Henson company, available, along with many other MIT projects, here. Thanks also to Kristin and Jeff Smith for suggestions, and to Janet Staiger for correcting my memory and calling attention to Dennis Bound’s book on “transmedia poetics” as applied to Perry Mason.

PS 11 Sept: Henry Jenkins has responded to my entry, with the first of three installments starting here.

Comic-Con 2008, Part 3: Two newbies share thoughts

Autographs are big: Richard Taylor signing books about the designs for The Chronicles of Narnia

Kristin here–

Back in the early days of this blog, I posted an entry on our friend Henry Jenkins and his concept of the “aca/fan,” a scholar who studies fandoms while being a fan him- or herself. At that time his book Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide, had recently come out, and I highly recommended it. Fortunately the book has had a well-deserved success. On October 1 it will be coming out in paperback.

In that entry, I described Henry and our long friendship with him:

Henry doesn’t study fans to find out what makes them tick. He knows that. He’s one of them, a participant in fan cons, a player of video games, an explorer of the multimedia sagas like those of Star Trek and The Matrix that have grown up in the age of franchise culture. He received his doctorate here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where David was his dissertation advisor, and we have followed his career, as they say, with great interest. Straight out of the gate he was hired by MIT, where he is now the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities.

(You can find Henry’s blog, “Confessions of an Aca/Fan,” here. He interviewed me when The Frodo Franchise was published; you can find that in three parts, here, here, and here.)

The Frodo Franchise dealt with fan culture as well in Chapter 6, on fan-originated websites. Convergence Culture deals to a considerable extent with modern transmedia franchises. Yet neither of us had ever been to that Mecca of fandoms, Comic-Con. Of course, this year, when I got invited to participate on TheOneRing.net’s panel on the Hobbit project, I accepted. I emailed Henry just in case he happened to be going as well. It turns out he was, being on a long driving vacation through the west with his wife and son.

At first I thought maybe we could meet up early in the Con and then get together afterwards and share our impressions. (We bloggers look for material anywhere we can find it, and this seemed like a golden opportunity.) In fact we didn’t meet early on. There was so much going on, and we never glimpsed each other in the course of the entire event—not surprising, really, when you consider its size. But I made cell-phone contact on Sunday, and we sat down in my hotel lobby and spoke our thoughts into a microphone. Here are some excerpts.

(We talk about what we went to—him to the TV previews, me to artists’ presentation.)

On Different Tracks

We started off by talking about what we had each concentrated on.

HJ: It’s very clear that it’s like six or seven different conventions I could have gone to in the course of the weekend, and it would be a totally different experience depending on which one you went to.

KT: Yeah, I had that impression that there were probably people here mainly to buy stuff, some people here mainly to see celebrities and get autographs and so on.

HJ: And even on that there was a split between the film and the TV people. And there’s a whole comics track. Under other circumstances I would have just been spending my entire time at comics panels, because they’re the strongest comics sessions anywhere in the country.

Coming Alone vs. Having Something Specific To Do

KT: I was happy that I had something to anchor myself, though. I don’t think I’d like to come here, at least for the first time, alone and not having anything specific to do.

HJ: Luckily Henry and Cynthia were along, but it was overwhelming a bit, trying to negotiate and keep up with three people in a space that congested. So that was its own kind of challenge. Sometimes I was thinking it would be great just to be a single person navigating through the space and not have to have large-scale logistics! The scale of it just blows you away. I’ve been on the floor at E3, which is supposed to be one of the largest entertainment trade shows. I’ve done South by Southwest. But neither of them are anywhere near the scale of Comic-Con.

The Scale of the Event

KT: They always say 125,000, because that’s the number of tickets they sell, but then you’ve got all the exhibitors and the people who are presenting on panels. It must be another few tens of thousands packed into that building.

HJ: Yeah, at least.

KT: I was kind of amazed that it worked as well as it did

HJ: Yeah, they did a remarkable job in just managing crowd control. Getting people in and out of things with some degree of order. Some more bullying guards than others, but it was probably necessary to keep the peace.

KT: Yeah, there were a LOT of guards and guides and so on, but people seemed really to be polite, on the whole. I was taking the shuttle bus from a hotel down the street [from my hotel] every day and then coming back by shuttle bus. This morning the bus was quite late compared to other days. It was supposed to come every ten minutes, and we were there maybe twenty. And people who were arriving made this very neat horse-shoe shaped line on the sidewalk. It was very orderly.

HJ: Almost no signs of anyone breaking in line, despite the intensity of some people’s desire to get into things. Someone commented behind me about ‘honor among geeks,’ and that’s probably a good description. There’s a strong honor code.

KT: The venue seems to be up to having that many people in it. I hardly had to wait for rest rooms at all.

HJ: No, the facilities are good.

We ended up doing a fair amount of what they call here “camping,” which is sitting in several panels in a row because there was something we really wanted to see. But you end up trapped in a space with no access to food. Hall H at least has rest-room facilities in the space.

KT: I didn’t try that myself, that is, camping. But I was going to this action-figure panel because it involved Toy Biz, which did the action figures for Lord of the Rings. I heard from people in line that a lot of them were there for the next panel, which was on Sanctuary, which I know from nothing, but they were very devoted and were saying, “They shouldn’t have put this in such a small room.”

HJ: There is a certain sense that you vote with your body at Comic-Con. One of my newest fandoms is Middleman, which is a new ABC family show, and it was in a small room, but we packed it. There was a sense of accomplishment. The producer looked out and said, “This may be the whole audience for the show,” because it hasn’t gotten much publicity yet. There was a sense that just being there was show of support for things.

KT: I wonder how many of the companies have people at those panels—in the audience. I hadn’t realized it, but there was somebody from New Line—who’s probably not from New Line anymore—and then some Warner Bros. people, supposedly, sitting out in the audience for the Hobbit one. That kind of surprised me. Why bother?

HJ: At the larger sessions it seemed they had blocked off four or five rows of space just for the studio people. Rarely were they occupied to anywhere near that extent, so it was maybe overkill. But there were a few sessions where there were a significant number of people. The Battlestar Gallactica, for example. There was a large studio contingent there for that. Suits and friends and family and other writers, because that was a kind of last hurrah for that production. They just wrapped shooting the last episode two weeks ago, so this would have been a major last gathering of a lot of those people. They said they really hadn’t had a chance to have a wrap party yet, so in a sense it probably was.

The Hall H Experience

KT: Did you have the Hall H experience at all?

HJ: We went to see Heroes one morning, which was the first time, they said, a TV show had made it into Hall H. We managed to be there for Watchmen and a few of the other movies that followed it.

KT: I kind of avoided it for a while because I kept hearing that there would be incredibly long lines, and I pictured just sitting there for hours and hours and hours reading and possibly not getting into what I wanted to see anyway. So I avoided it until yesterday [Saturday], and I went to the Terminator Salvation one. I wanted really to go to the Pixar one, so I went to get in line very early, and ended up getting in on time for Terminator Salvation.

HJ: Well, for Heroes we waited for about an hour outside and then got in. Then there was a fairly long wait to get started, but then we knew that there were several things after that that we wanted to see as well.

KT: And was it full?

HJ: It was packed. But Heroes has been a kind of success story of Comic-Con. They showed the pilot there before it debuted, and Heroes is pretty desperate at this point to rekindle fan enthusiasm. Last season is largely seen as a bust. Hence their decision not to come back from the strike. They did a partial season and put it off to the fall, because the ratings were plummeting and they were getting bad buzz from fans. So they wanted to come back this year with a killer. They showed the entire opening episode, which was definitely a fan-pleaser. They had figured out what had gone wrong the first season and had put together something that was going to please. So there was lots of extended applause at key moments. It’s kind of fascinating to watch an episode of a TV show with 6500 other people.

The Exhibition Hall

KT: I only discovered the comics section today, as I was about ready to leave, because I hadn’t really been aware of which sections were devoted … I sort of thought it was all random, but obviously they do devote one big section to all the people who are selling old comic books. I suppose you could just stay in one part of the hall and never see the rest of it.

HJ: I felt I barely made a dent in the hall. The first day I didn’t quite realize how big it was, so I was just going up every aisle, and the second and third day I was going on targeted missions. But it still was just so immense that there’s no way you could see it all.

KT: And it’s SO congested.

HJ: Especially if you get to the studio side of things.

Autographs and Planning

KT: I could not figure out what was going on at the Warner Bros. exhibit, but they were constantly surrounded by lines and lines and lines of people who were obstructing the aisles around them. I guess they had people from their TV shows signing.

HJ: They seemed to. I kept stumbling into people. You wander around one corner and there’s Peter Mayhew of Chewbacca fame sitting there, and Will Frakes suddenly would pop up at another table. Neither particularly advertised. Then there were all the advertised autographed stuff. There were a lot of people there that you would know in another context.

KT: I don’t know how you would find out about all of those things in advance. I don’t think Lynda Barry was listed in the program as doing autographs, but she was at the Drawn and Quarterly booth at certain times. I missed her entirely. I got her autograph because I was sitting in the audience before her presentation and she sat down beside me.

HJ: They seemed to have a certain number of people who were there to do autographs, but then there were all these other people randomly. I guess you had to follow a particular company and maybe they posted on the Web.

KT: Yes, I was doing autographs at certain times for my book, and it was just on TheOneRing.net and The Frodo Franchise [websites]. You have to really investigate, go in with a plan.

HJ: It seems to be the case: The more you plan, the more you can get out of the experience.

KT: We were selling copies of my book at this very small booth, and I was there for an hour at different times of day on three days. I think almost everyone, if not everyone, who bought a copy came to the booth specifically to buy it. There were no impulse purchases. I don’t think people buy books at Comic-Con.

HJ: I looked at comics while I was there, but I would buy them from my dealer back in Boston or online at Amazon or My Line Comics [?]. Why I would weigh my suitcase down with comics in the age when it’s so easy to buy stuff digitally?

KT: Not new ones.

HJ: Not new ones. Collectibles, sure.

KT: Unless you have them signed.

Fan Culture hangs on at Comic-Con

HJ: Usually the cons I go to are small-scale, very intimate, you know a high number of the people who are coming. It’s fan-driven and fan-focused. This was like Creation Con on steroids!

KT: Though technically speaking, it is run by fans; there’s a committee.

HJ: It is, and they had a really bad art room with lots of cat pictures and dragon pictures and wolf pictures, which gave it a sense of fan authenticity, because they hadn’t closed out the really bad fan art, even in the midst of all the commercial takeover.

KT: Well, I missed that one.

HJ: You didn’t miss anything, other than the reaffirmation that this was still a con. There were still places and niches and corners where the fan stuff still ruled. You wouldn’t see fanzines there, but then you wouldn’t see them at most fan-run cons these days, since everything’s moved to the Web.

KT: Well, there’s Artists’ Alley, which is way over in the corner. That seems to be fans who are aspiring to be pros but haven’t really made it yet.

HJ: Well, it was a mix. I mean, you’d see Paul Chadwick there [author of “Concrete” series, published by Dark Horse Comics] or Kim Deitch [author of graphic novels such as The Boulevard of Broken Dreams and Shadowland], who were independent and weren’t necessarily going to be there with a company, but yeah, it’s definitely a lot of wannabes in some of that space.

And then fans show themselves through costumes. For all the jokes about women in Princess Leia costumes—and I saw maybe a dozen Princess Leia slave-girl outfits—it was still a way in which fans asserted their presence. There were some quite remarkable pieces of fan performance going on there. There was someone doing Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast, which had quite a spectacular Beast costume—a little more arty than one expects at a fan con.

Genre

[I mentioned having seen Focus Features’ Hamlet 2 preview.]

HJ: The role of comedy here interests me a lot. I’m always intrigued: What’re the borders of what a fan text is and what isn’t a fan text? Here comedy seems to creep into fandom in a more definitive way than I’ve seen elsewhere. So there was the focus on Hamlet 2, there was Harold and Kumar, The Big Bang Theory [TV series, 2007-08], but then just a bunch of panels on writing for sit-coms. So it’s probably just the industry’s priorities, but it’s interesting that it doesn’t extend to drama. You can imagine a lot of people there being into The Wire or The Shield or some equivalent, and it didn’t cross over in that direction.

KT: I suppose it’s what the studios think the fans want. It’s true there were a lot of comedies, and martial arts, war.

HJ: I think martial arts probably has crept into fandom pretty definitively over time. But it’s interesting to see where the boundaries are. We stumbled across one booth that had just a porn star signing her pictures, and it sort of outraged my son. Pornography isn’t fandom in his world view, but he thought nothing of going up to get wrestlers to sign autographs. Probably in any other fan con, the strong presence of wrestling performers would be out of keeping with fandom.

The Economics of It

KT: I was struck by how cheap it is, basically. How much was it for a single day pass?

HJ: Twenty-five dollars for a single day pass. It’s not bad at all for the scale of what you get. [Four-day passes are $75.]

KT: Some of the smaller tables were something like $380 for the full period, which I thought was kind of cheap. But obviously they NEED both sides of it. They need the exhibitors to attract the people and they need the people to attract the exhibitors, so keeping the cost down makes perfect sense.

HJ: The scale at which companies brought in people was also truly remarkable. I certainly have been to cons where they might have two or three performers from a show, but they brought the entire regulars of Heroes down, as well as the entire writing team. And Heroes is a large, large cast. They scarcely had time for anyone to say anything, but all lined up there on a panel, it was a pretty spectacular display. And Watchmen did pretty much the same thing. All the main characters in Watchmen were there with the director.

KT: That reminds me of the coverage that the film events and I suppose the television events, too, get in the trade press. I’m sure you read some of these articles about how, “Oh, it’s all becoming SO much Hollywood. The big media companies are coming in and taking over,” and so on. It struck me that Hall H is really kind of a world unto itself.

HJ: It is.

KT: It’s separate. You have to go out of the building and get in this line, and then you have to go out of the building when you exit. It’s quite a hike to get there if you’re around D or C in the exhibition hall. I think probably they don’t see much of the rest of the con.

HJ: It does seem largely cut off. That’s the sort of classic place where people camp. And so there’s almost an interesting tactical advantage in being one of the filler programs between the main events, if you can really maneuver into that. It’s like being right after a hit TV show or between two hit TV shows. You’re going to get exposure to people who wouldn’t otherwise. Yesterday Chuck was between Battlestar Gallactica and the Fringe panel. I’ve never see Chuck, but I wanted to see Battlestar and I wanted to see J. J. Abrams [executive producer of Lost and one episode of The Fringe], so we stuck through it. And we’ll probably give it a shot come fall as a result of being exposed to it in that way. There’s lots of things that get sandwiched in that probably get a boost off of this. Or they could hurt themselves.

KT: Bring the wrong scenes or whatever.

HJ: Wrong scenes or just the people are inarticulate. There’s certainly a range of comfort level up there.

In terms of the press coverage, the fact that Entertainment Weekly put Watchmen on its cover this week a year before the film comes out, purely on the basis of it playing at Comic-Con, says something about the publicity value of this thing.

KT: Oh, yeah, for the films there’s no doubt about its publicity value. I just think that if the big entertainment journalists plant themselves in Hall H and don’t pay a lot of attention, then you get this coverage that makes it sound as though the movies are just taking over everything.

HJ: It’s odd. It’s certainly every bit as spectacular a place to do TV as it is to do film. And comics. I couldn’t believe the betrayal I was committing in not seeing the full writers of Mad magazine in the 1960s or seeing Forrest J. Ackerman and his staff—things that were really significant to me as a kid or now. But they were competing with other things that I valued even more. So there are things that you would have killed to get to in any other context that you pass up because there’s so much going on at once. You can’t get to it all.

KT: I just get the feeling that if you at Hall H you’re at one con, and if you’re at the rest of it, you’re in a completely different world. The trades just never talk about that other stuff because it’s not really high-powered.

HJ: The question is, to what degree does that other stuff provide the context that explains what goes on in Hall H? Geek culture is integrated. Probably there are lots of people who travel between Hall H and other things, but if the reporters stay at Hall H, they won’t see the full layering of this.

The Gender Composition of the Attendees and the Industry

HJ: One of the things that struck me was the gender composition here was much—well, certainly there were more guys than girls, but compared to, say, E3 or many other cons I’ve gone to, the gender balance was surprisingly solid. There were an awful lot of women there.

KT: Yeah, they remarked on that on the Harry Potter panel this morning, saying that, unlike those cons, there were probably more women than men in that particular room.

HJ: That makes sense.

KT: When I went to the One Ring Celebration, the ORC, for my book, as I said there, it was maybe 95% women. I suspect it’s partly a factor of whether a con has gaming facilities. Gamers will come, and they’re mostly going to be guys, although probably not as much as it used to be.

HJ: Historically, if you go to Creation cons, which are more star-centered, men turn out much more, whereas if you go to a fan-driven con, which is fanzine oriented, women turn out much more. But because this combines everything, you’ve got just such a spread of people.

I’ve seen people argue that Comic-Con is becoming powerful and it’s exaggerating the power of fan men at the expense of fan women, that the fan-boy mafia is taking over the entertainment industry. Certainly you see it on the producers’ side, that an awful lot of the guys onstage would have been in the audience a decade before—and they’re mostly guys. But what’s interesting is to see the audiences that they’re trying to respond to and engage with has a large female component, and that’s got to have an impact over time on what plays here and what doesn’t.

KT: One of the people on the “Masters of the Web” panel on Thursday morning was making the point that now the younger studio executives are either people who had their own Websites a few years ago or they were in college when the big Websites were being formed. Now they’ve grown up into adulthood reading that stuff, and they’re now in position of power and will continue to be in the industry.

HJ: It was fascinating just to watch the producers, writers, stars, to see which ones were really comfortable in the space and which ones weren’t. Someone like Joss Whedon just grew up in that space. That’s his world. He was totally in his element, and he would understand what questions were being asked and how to respond to them and could use in-joke references to the culture, whereas someone like Alan Ball (executive producer), who no doubt in another context would be totally articulate and interesting, really felt strongly uncomfortable. Moving from Six Feet Under to True Blood, he doesn’t yet know how to “speak fan.” Where Zack Snyder (director of 300) has got to be the most totally inarticulate person I’ve seen on a stage in a long time. Watchmen is going to be his second movie, and he totally works with images, but his ability to use words did not seem to be his strong suit. Some of them who have done multiple fan shows seem really comfortable, and others just looked in shell-shock up there.

Henry and his other new book, Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers

Comic-Con 2008, Part 2: Why Hollywood cares

Kristin here-

You can’t picture the typical reader of Variety or the New York Times picking up the latest issue of Superman at the local comics shop. So why is Comic-Con, the annual confab of fans from around the world, gathering so much interest from both mainstream media and the trade press?

The obvious answer is that a growing number of megapictures and TV series are derived from superhero comics and, more broadly, fantasy and science-fiction literature. The chance to see stars and directors on panels, the first look at preview clips–these draw both fans and entertainment reporters.

Recently, the press is suggesting that Hollywood’s presence is becoming dominant at this gathering of self-professed geeks. After going to my first Comic-Con last month, I’m thinking that something else is going on. First, it’s not clear that Hollywood rules the Con. Second, and more interesting, is the question of exactly how Hollywood benefits from being there–or indeed, whether it benefits at all.

Hollywood vs. comics

Michael Cieply’s July 25 article in the New York Times is entitled, “Comic-Con Brings Out the Stars, and Plugs for Movies.” To read it, you would think that Comic-Con is a purely film event. Cieply Refers to Hugh Jackman promoting X-Men Origins: Wolverine, Mark Wahlberg presenting clips from Max Payne, the cast and director of Twilight addressing a squealing crowd of young female fans, and so on. Nary a mention of comics, video games, action figures, collectibles, original artworks, and other items being sold or promoted in the vast exhibition hall, let alone the numerous simultaneous panels going on all day upstairs and the long, sinuous lines of fans awaiting their turn for autographs from artists.

Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Geoff Boucher started his July 28 story, “This is the year they tried to take the comic out of Comic-Con.” The piece is entitled “Comic books overshadowed by the embrace of Hollywood.” A reporter could probably find plenty of people at Comic-Con to deplore the decline of comics’ representation at the event and an equal number to say that the non-Hollywood part of Comic-Con is alive and well.

Boucher quotes two of the former, who tend to be people who have been attending Comic-Con and other such events for decades. Michael Uslan, a comic-book author in the 1970s and now the executive producer of, among others, The Dark Knight, declares, “I think Comic-Con is in danger of having Hollywood co-opt its soul. It’s turning into something new, and you could really see it this year.” Robert Beerbohm, who has sold comics at every Comic-Con since it was first held in 1970, also worries about the trend: “All the Hollywood directors say that they loved comics as a kid, but now they [i.e., the comics] are being pushed off the floor. Where are the next generation of directors going to come from?”

I tend to think that young directors get influenced by such a diverse mix of popular and high cultural works that the putative lack of comics at Comic-Con won’t make much difference. Plus these days the “comics” are often graphic novels, readily available to any future director from big bookstore chains and internet sources.

Avoiding Hall H

Comic-Con has grown hugely over its nearly four decades of existence, and other media have crept in slowly. Hollywood has been prominently represented for years now. Peter Jackson promoted The Lord of the Rings there, and Adrien Brody and Naomi Watts showed up to promote his King Kong. But somehow this year the journalistic zeitgeist seems to have dictated that most writers choose to stress that Hollywood is in danger of taking over the con. Well, it makes for a dramatic story premise.

Admittedly, I’m a Comic-Con newbie. I’m sure to the old hands the creeping presence of films and TV is noticeable and perhaps worrisome. To me the big Hollywood previews were something you had to seek out, and they weren’t that easy to get to. As I mentioned in my first blog on the subject, the ground floor of the enormous, lengthy building is divided into halls A to H. A to G formed one vast open space, and an attendee could trek from one end to the other without going through doors or lobbies. Hall H, where most of the biggest Hollywood previews and panels took place, was entered from a separate door on the outside of the building. The lines to get in snaked in the opposite direction from doors A to G. Entering and exiting the exhibition hall’s lobby through one of those doors, you might not even notice the lines.

The other big “Hollywood” space is Ballroom 20, on the second floor. Anyone going from one part of the building to the other on this level, on the way to the panel rooms or the autograph area, would be likely to pass it.

My sole Hall H experience came when I attended the Terminator Salvation and Pixar previews on Saturday afternoon. The rest of my time at Comic-Con bore no resemblance to what the news stories describe. Apart from Hall H, I moved extensively around the exhibition hall, the various hallways between the panel rooms, through the “sails pavilion” and along the main lobby without having any sense of the big film and television events going on. I occasionally passed Ballroom 20 when there was a long line outside, but even then there was seldom any indication of what the people were waiting for—no banners or posters. (In general, Comic-Con has sold only very limited “signage” outside the exhibition hall. The upstairs hallways outside the panel doors were unadorned apart from small schedule boards.) In the exhibition hall I saw the studio logos hanging above their exhibit spaces and learned to skirt around them to avoid the particularly dense crowds in that area—but it was one area among many in that giant space. I seem to have experienced a different Con from the one widely reported on.

I’m not alone in thinking that Comic-Con is a giant, diverse event that simply has a big Hollywood screening room next door for those who are interested. Marc Graser, who wrote several pieces on this year’s Con for Variety, talked with its PR director, David Glanzer:

“Not every studio has a presentation every year,” Glanzer says. “It’s not an earth-shattering event. Sometimes people read too much into it.”

Yet the irony in all of this is that film- and TV-specific programming makes up less than 25% of the Con’s schedule, Glanzer says. And even on the event’s show floor, studios are overshadowed by comicbook publishers, retailers, videogames and toy companies.

The rest of the panels are educational sessions on how to break into the comicbook biz, for example, that allow Comic-Con to consider itself an educational nonprofit.

In other sources, Glanzer gives the more specific figure for film- and TV-related programming as 22%.

Those educational sessions for budding comic-book creators do make up quite a share of the program. These aren’t just how-to-draw lessons. There was a panel, “Comic Book Law School Afternoon Special: Gone But Not Forgotten!” dealing with intellectual property rights and others on the practicalities of the business. There were also 50-minute “Spotlight” sessions devoted to individual artists like Ralph Bakshi and Lynda Barry. The Eisner Awards ceremony celebrated accomplishment in the comics world.

Camping in Hall H

Why do journalists covering Comic-Con tend to stress Hollywood so much? I assume because the previews and panels are where the big stars are. They and their forthcoming films are the big news, the buzz that makes it worthwhile for magazines, newspapers, and blogs to spend the money to send their reporters or hire free-lancers. Most reporters experience that other “Hall H” con that I only visited once. I saw Anne Thompson at the “Masters of the Web” panel on Thursday morning, and she duly blogged about it. Still, most of the many Comic-Con stories posted on her Variety blog by her and other reporters were on the films and TV shows.

And why not? The big entertainment reporters get access to the major talent for short interviews, and their photographers can get up close for glamorous shots to use as illustrations. That’s no doubt what the largest portion of their readership or viewership is interested in. Attending the Con is an efficient way of generating a lot of copy.

Nevertheless, it doesn’t hurt to note that Hall H seats 6500 people, dozens, perhaps hundreds of them the entertainment reporters and bloggers. That’s out of 125,000 attendees who bought passes and probably tens of thousands more who were exhibitors, “booth babes,” or panel presenters. Granted, people circulated in and out of Hall H, though my impression is that some people stayed there much of the time. If sheer numbers of fans were to determine news coverage, the other facets of Comic-Con would get more attention than they do. But it’s the stars.

What’s in it for the studios?

The answer to that question might seem self-evident: publicity, and lots of it. The situation fuels itself. As more reporters from bigger outlets come to Comic-Con, the studios get more valuable publicity at a relatively small cost. (USA Today’s July 28 wrap-up occupied nearly a page and a half of the print edition.) And as more studios send previews and big stars, more news sources will find it worth sending their main reporters. In fact, perhaps this year the situation reached saturation. Hollywood studios filled all the possible slots in the two large halls, and in some cases big news outlets sent teams of reporters. That might be what gave both studio execs and reporters the impression that Hollywood is steamrolling the rest of the Con.

Publicity is all very well, but in the August 1 issue of The Hollywood Reporter, Steven Zeitchik questions whether it’s really worth all the fuss to preach to the converted. He notes the growth of the big studios’ efforts to impress fans: “On its face, this shouldn’t be the case. A brand’s cult following isn’t a very large number, and it’s also a group already inclined to like and spend money on a product, which by most marketing logic is exactly the group you should spend the fewest resources on.”

Sure, the Comic-Con previews may impress fans who are assumed to be tastemakers, particularly in the blogosphere. Zeitchik comments, “And if the tastemaker effect doesn’t happen, the strategy loses its teeth. One director who’s had repeated visits to Comic-Con noted just before he went to this year’s convention that ‘The total number of people in the blog world is probably only a few hundred thousand, and as much as they might hate to hear it, for most movies that’s not going to make the difference between a success and a failure.’” Zeitchik points out that the Speed Racer preview at the 2007 Con was cheered, but that didn’t mean that a lot of fans bought tickets to the film itself. The wider public stayed away.

Yet surely the studio suits know all this, and they keep providing glimpses of films and series to come. What other advantages do they perceive?

A Comic-Con preview can be a chance not only to woo fans but to get clues that might help in the general publicity campaign. Focus Features president James Shamus, who previewed Hamlet 2 at Comic-Con this year, views the process as a chance to get instantaneous feedback that might help later in promoting a film: “It’s the start of an ongoing dialog. It doesn’t just start and end there. It’s not a thumbs up or thumbs down because some guy didn’t like your poster.”

Many studio executives also still believe in the viral quality of fan buzz on the internet. Lisa Greogorian, the executive vice-president of marketing for Warner Bros. Television, assesses past years’ previews of Chuck, Pushing Daisies, and The Sarah Connor Chronicles: “We saw an immediate impact online. Word of mouth is now one individual impacting a couple hundred individuals who can impact thousands. Social networking has allowed us to empower one fan to impact thousands of potential viewers.” (Both executives spoke to Marc Graser for a July 11 Comic-Con preview in Variety.)

I emailed James, who is an old friend of ours, about the subject. He pointed out that while the blockbusters may have a pre-sold audience, smaller films like Shaun of the Dead can create momentum at Comic-Con. Moreover, there are a lot of blogs out there now, and studios monitor the more important ones to help shape their own publicity efforts.

A Comic-Con presence often, however, is not simply a matter of persuading fans to watch a film or TV series. Sometimes major negative buzz began to surround a film from a few bad online comments based solely on the Con previews. Wooing the fans with stars and footage can be a way to prevent that negativity from getting started—or a big reason for some studios not to preview a film at the Con.

One factor that doesn’t get mentioned in the press coverage of why the Hollywood studios bother with Comic-Con previews is that this event in effect provides them with huge, low-cost press junkets.

The modern press junket for a tentpole film is typically an expensive affair. The studio pays for dozens, maybe hundreds of reporters to travel to a single spot. It may be as bland as a rented hotel conference room, or it may be set in some more picturesque locale. At Cannes in 2001, New Line held a big junket for The Lord of the Rings at a hillside chateau with a spectacular view. Other junkets might be on-set, at a studio where the film is still shooting. The studios have to shell out for the reporters’ hotels, give them a per diem, and supply a reasonably impressive swag-bag. And there isn’t just one junket, but several in the course of publicizing a major release.

With Comic-Con, the studios have a whole bevy of reporters, many of them famous names in their own right, delivered to them at their employers’ expense. There are rows up front in Hall H reserved for them They sit through preview session after preview session for four days and generate a huge amount of publicity. Certainly there are expenses involved for the studios, but cutting together a few scenes or a random collection of finished shots together with a temp music track doesn’t cost a lot, and the actors don’t get paid extra for their publicity appearances. Transportation might be a relatively simple matter of sending whatever stars happen to be in Los Angeles in a limo down to San Diego. James specified to me that Comic-Con is “a very cost-effective” way of bringing the talent from a film together with fans to gauge how they interact.

I suppose for the reporters, the chance to attend what is in effect a whole passel of press junkets in one stretch saves a lot of time on airplanes.

Oh, yes, the comics

Some stories do stress the comics. Not surprisingly, Publisher’s Weekly printed an excellent preview that talked about the comics and graphic-novels companies that would be present. The author also pointed out that the connections between comics and films are getting closer, what with all the adaptations that have been made or are in the pipeline. The article quotes comics author Steve Niles (30 Days of Night) as saying, that the Con is “crawling with producers now, which means some of the up-and-comers have a chance to get someone to notice their book.”

USA Today ran a story that analyzed the recent trend toward comics-based movies quite carefully. Author Scott Bowles discusses the trends toward darker stories and heroes who aren’t conventional heroic, such as Hancock and the Watchmen. The story also discusses whether this trend indicates that the superhero genre is nearly over or just reaching a more imaginative stage.

Bowles also points out that the traditional notion of the Con as largely frequented by fanboys is no longer accurate. This year nearly 40% of the fans were female.

Costumes and the press

Naturally journalists with cameras make a beeline for costumed Comic-Con attendees. They stand out in the crowd, they seem to these journalists to epitomize the fan sensibility, and they are delighted to pose at any length for photos. (Anne Thompson’s blog has a sampling posted.) Many of them have very impressive costumes and put on little skits or tableaux in the hallways. There’s a “masquerade” competition with cash (up to $150) and merchandise prizes on Saturday night.

[Added August 11: David Glanzer kindly emailed me to compliment me on this entry. He informed me that roughly one percent of fans attending Comic-Con come in costume. Not that either he or I have anything against costumed fans. On the contrary, I enjoyed seeing them, and obviously they were having a terrific time. But some journalists adopt a definitely mocking tone, and even those who are respectful tend to mislead the public about the attendees at the Con in general.]

But most attendees are content to declare their interests on their T-shirts, as I did, and their shopping bags. Again, that doesn’t make for good copy or images. The photos at top and bottom show what I saw much of the time in the exhibition hall. These people are not likely to be approached by journalists, though these days they might have a questionnaire thrust into their hands by a sociologist or ethnographer trying to figure out what makes fans tick.

If you have to ask …

For my account of things and event relating to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings at Comic-Con, see here.

Rowling’s revelations: Who wants to know

Dumbledore, by Lisa, from

http://www.poudlard.org/fanarts/displayimage.php?album=toprated&cat=6&pos=0

Kristin here–

By now anyone who has not lived in thorough isolation from the media knows that on October 19, during a signing of Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows at Carnegie Hall, J. K. Rowling revealed that Prof. Albus Percival Wulfric Brian Dumbledore is gay.

At least in her opinion, some might add.

Rowling’s public revelation that she has long considered Dumbledore to be gay came during a question and answer session in which a fan asked, “Did Dumbledore, who believed in the prevailing power of love, ever fall in love himself?” Rowling replied, “My truthful answer to you … I always thought of Dumbledore as gay.” According to mainstream media reports, after a stunned silence the audience burst into a lengthy ovation.

Rowling has made a few additional comments on this subject since then. On October 22 during a press conference in Toronto, she was questioned about how far back her outlook on Dumbledore’s sexual orientation went. She dated it back to the planning stages, “probably before the first book was published” (Harry Potter and the Philospher’s Stone, 1997). She pointed out, “I was writing for seven years before the first book came out.” (The press conference has been posted in two parts on YouTube, here and here. Some stories from reporters covering the event have slightly misquoted Rowling’s statements. My quotations are transcribed from the video.)

Naturally questions about the Dumbledore outing came at regular intervals during the Toronto press session. Initially Rowling commented, “It has certainly never been news to me that a brave and brilliant man could love other men.” Asked about the political ramifications of the outing, Rowling said that she could not comment on that so soon after the fact. “I can’t really answer that. It is what it is. He’s my character, and as my character, I have the right to know what I know about him and say what I say about him.”

But do we want to listen?

Of course, she has the right. The questions that have been raised by many are, should she? If she does, should we accept her statements as true within the universe of the published books?

Whether she should provide additional background for the series is basically a matter of opinion. Some people, many of them children, want more information and think she should.

Salon.com’s Rebecca Traister has posted a thoughtful essay taking the “she shouldn’t” position. She points out one thing that most fevered accounts of the Dumbledore outing have neglected: “Dumbledore’s gayness is one of the pieces of bonus information about her characters that she’s been dispensing steadily since the publication of her magical swan song, ‘Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.’”

Certainly at the Carnegie Hall appearance, the Dumbledore question came amidst several that Rowling was asked about the fates or motives of other characters. (The most extensive transcript of that Q&A session is on The Leaky Cauldron.) Nearly all mainstream media reports ignored these in favor of blowing up the gay issue, but just as much information about other characters was revealed, and Rowling has answered similar queries in other Q&A situations.

Traister admits that the fans are the ones asking for such information. “Her abundant generosity with information is surely a response to a vast, insatiable fan base that does not have a high tolerance for never-ending suspense, ambiguity or nuance. As she told the ‘Today’ show’s Meredith Vieira back in July, ‘I’m dealing with a level of obsession in some of my fans that will not rest until they know the middle names of Harry’s great grand-parents.’”

Traister adds, “Rowling naturally wants to provide answers for these heartbroken obsessives who perhaps are too young to know the satisfying pleasures of perpetual yearning and feel that they must must must know how much money Harry makes and whether Luna has kids.” I don’t know about heartbroken, but they certainly are curious.

Traister goes on to argue that Rowling should stop giving out information and ruining readers’ own imaginings about what the author left out. She cites an example of Rowling revealing to a fan what Harry’s Aunt Petunia nearly said to him upon their last parting. According to Rowling, it was “I do know what you’re up against, and I hope it’s OK.” Traister is disappointed: “Oh. That’s too bad. Because in my imagination, Petunia was going to say something much more exciting than that.”

Perhaps in many cases, especially about specific details like this, knowing is less fun than imagining. Still, I’m sure some of Rowling’s revelations are more exciting, or at least more interesting, than what we imagine.

Let’s take one small example, Rowling’s explanation for the name “Dumbledore.” Few readers will imagine anything about it or realize that the word actually means something. I have wondered whether Rowling just liked the sound of the word (which appears in Hardy and Tolkien) or she saw some connection between the headmaster and a bumblebee. She revealed the answer in a radio interview in 1999: “Dumbledore is an old English word meaning bumblebee. Because Albus Dumbledore is very fond of music, I always imagined him as sort of humming to himself a lot.”

That’s charming. I didn’t imagine Dumbledore humming as I read the book. Indeed, I don’t recall any scenes where he is alone (presumably when he hums), given how much of the narration is restricted to Harry’s point-of-view. But I am glad to know this, even if it had to come from the author herself. (In the same interview, by the way, she said, “I kind of see Dumbledore more as a John Gielgud type, you know, quite elderly and – and quite stately.” Perhaps a hint of where the gayness crept in.)

If Rowling were to heed Traister’s plea that she stop dispensing extra-textual information, that would mean we adults, who presumably “know the satisfying pleasures of perpetual yearning,” would get our way and the children wouldn’t. (Of course, not nearly all adults would refrain from asking for more information from Rowling.) I think that’s rather unfair, since these are at bottom children’s books. It was initially surprising how many adults ended up reading them, and there are HP fans of all ages. Still, shouldn’t the target audience take priority?

The video of the Meredith Vieira interview and the transcript of the Carnegie Hall event confirm that many of the questions were requests for more information about the characters. Would we really want the author to refuse each of these? How boring and frustrating for those children if every other answer is, “I really shouldn’t tell you. Just use your imaginations”! They want those “pieces of bonus information about her characters that she’s been dispensing steadily.” As far as I can tell, most or all of the bits of information Rowling has given out have come in response to specific questions from fans. She hasn’t been volunteering them right and left. And apart from the Dumbledore comments, the information she gives out has hardly been flooding the media to such an extent that we can’t avoid it if we wish. Given that Rowling has been answering such questions for months, why did commentators wait until this particular revelation to complain?

Who’s J. K. Rowling to tell us Dumbledore is gay?

Quite apart from there being some people who want this information and others who don’t, there is a more theoretical question. As Jason Mittell puts it in a brief essay on his website, “What does it mean for an author to proclaim such information about a character in an already completed fictional world?”

Mittell would accept that Rowling’s statements about that world would become part of the HP canon as long as the series was still in progress. “But something changes once a series is complete.” He points out that Rowling seems to have known all along that Dumbledore is gay, and yet she never made that explicit. “Does she retain her power to control her fictional world after the books have been closed?”

Does it have to be explicit, or will implicit do? Some, including Rowling, would say that there is a portrayal of Dumbledore’s relationship with Grindelwald that hints at his being gay. At the Toronto press conference, Rowling stated, “It’s in the book. It’s very clear in the book. Absolutely. I think a child will see a friendship, and I think a sensitive adult may well understand that it was an infatuation. I knew it was an infatuation.” I must admit that I didn’t pick up on the clues. Not that I’m insensitive, I hope, but because it would not have occurred to me that a popular mainstream writer would include a prominent gay character. (Associated Press writer Hillel Italie has pointed out a few passages that some may have taken as indications.)

[Added Oct. 29: The November 2 print issue of Entertainment Weekly has the results of an online poll, “Did you suspect Dumbledore was gay? (p. 11). 22% said they did. That’s probably self-selecting, as those who did might be more likely to vote. Still, at least some people did figure it out.]

Putting aside that example, though, much of the other information Rowling has been giving out does concern events that occur after the books’ action or are never referred to in the texts, so Mittell’s question remains.

Mittell contrasts this situation with that of Star Trek, where it has been the fans who “claim their interpretive rights to open up ambiguities and subtext freely,” primarily by writing fanfiction. The situation is different, though, I think, because most fans would not claim that their fics enter into and become part of the canon, even though they may meticulously obey its premises. Rowling seems to be claiming the right to expand the HP canon by her statements as well as by her writing.

(By the way, Rowling also mentioned fanfiction during her answers about Dumbledore at Carnegie Hall. I’ve written on her remarks and that subject on the Frodo Franchise blog.)

One can accept Rowling’s pronouncements about the book series or not. But do those pronouncements carry any greater weight than comments made about the HP world by others?

I am aware that in the 20th Century, the “death of the author” was proclaimed. When I was in graduate school, “intentions” was still sort of a dirty word in analysis. If the work cannot stand entirely by itself, then it has to some degree failed, was the widespread view.

There’s some truth to that, and yet there clearly is a very widespread impulse on the parts of readers and viewers to ask living creators for more. Film scholars read interviews with directors and other filmmakers. Some filmmakers have written about their individual works or their craft in general. David has commented here recently, “Do filmmakers deserve the last word?” As he shows, they can dispense misleading information about their own films. Yet not letting them have the last word doesn’t mean we must ignore all their other words. They often have very interesting things to say.

There are points that could be made in favor of a voluble Rowling.

One could argue that the books are not necessarily closed. Rowling could always write more in this universe. Indeed, she has said she probably will write an encyclopedia on the HP world–though she has cautioned this may not be her next project. A summary of Rowling’s July 24 appearance on the Today Show describes the project, partly in Rowling’s words: “’I suppose I have [started] because the raw material is all in my notes.’ The encyclopedia would include back stories of characters she has already written but had to cut for the sake of the narrative arc (‘I’ve said before that Dean Thomas had a much more interesting history than ever appeared in the books’), as well as details about the characters who survive ‘Deathly Hallows,’ characters who continue to live on in Rowling’s mind in a clearly defined magical world.” Presumably much of the information she has given in answer to questions comes from this mass of material, so it may someday exist in print with her as the author.

In the Toronto press conference Rowling gave further information about possible writing projects within the franchise. She said she would probably not write a prequel for the HP series, though she would not rule it out entirely. Asked about the rumored encyclopedia, she replied that it “would be the way of putting in all the information, the extra information on all these characters.” She adds that the proceeds would go to charity and that “It’s certainly not something I plan on being my next project. I’d like to take a little time from Harry’s world before I go into that.”

Tolkien did something comparable. For nearly two decades after the publication of The Lord of the Rings, he wrote drafts of essays on various characters and events. He seems to have initially intended these as an entire volume of appendices, though later he continued because he just could not seem to stop examining his invented world. The resulting posthumous publications of these texts as edited by his son are not exactly canon—not least because they are unfinished and sometimes contradict each other. But they certainly are treated by scholars and fans as illuminating parts of Tolkien’s created world that are not in the novel. Semi-canon, if you will. Perhaps if Rowling does write down all the nuggets of information that she has been tossing out, publication will anoint them with canonical status at last.