Archive for the 'Fans and fandom' Category

The latest updates

KT here:

On May 29 we posted an entry responding to the inevitable badmouthing of sequels that journalistic movie critics tend to indulge in when the summer season starts. “Live with it! There’ll always be movie sequels. Good thing, too.” gathered comments from current and present “filmies” of the University of Wisconsin-Madison. They defended sequels for a wide variety of reasons.

Now another ex-Madisonian, Henry Jenkins, has weighed in with “The Pleasures of Pirates and What It Tells Us about World Building in Branded Entertainment.” Despite its somewhat formidable title, this essay jumps into the fray, taking critics to task for their knee-jerk tendency to lump virtually all sequels together into a category fraught with prior expectations and to dismiss the latest entries as mindless, inept films.

Henry takes Pirates of the Caribbean: At World’s End as his point of defense. Somehow critics seem by telepathy to agree to take the same stance on a particular blockbuster. Here they claimed that AWE is far too complicated and gets bogged down in exposition at the expense of action. (So much for claims that blockbusters are all CGI pyrotechnics and no plot!) They also kvetched that there is too little of Jack Sparrow’s character, apparently their main focus of interest in the film.

Henry takes AWE to be, alongside The Matrix, an example of elaborate world-building, a trait of the best of the big film series. In the age of DVDs and cross-media franchises, such films, he argues, are meant to be watched more than once. They also place a lot of faith in the viewer to be able to follow a complicated plot. Henry, like Steve Johnson in his Everything Bad Is Good for You, credits modern media as challenging viewers/readers with dense works that require a lot of figuring out.

Critics assume the opposite, that summer movies are supposed to be mindless entertainment, and they treat them as such. Complexity, which they would hail in an art-house release, becomes a fundamental flaw. Henry has some cogent remarks on the circumstances of reviewers’ screenings and how they handicap the writers’ approach to pop summer movies.

Whether or not one admires AWE, Henry mounts a strong defense of the film and in the process shows how much most reviewers are out of touch with audiences’ tastes and miss the various ways in which summer blockbusters work.

In other news, David’s The Way Hollywood Tells It has just been slated for translation into simplified-form Chinese. He’s now preparing a blog entry paying tribute to the great art theorist Rudolf Arnheim, who died on Monday at the age of 104. The family’s obituary is here.

The Cinema Ritrovato, which we’ll be attending in July, has posted a provisional schedule here. David will go on from Bologna to Brussels for research and the annual Cinedecouvertes and L’age d’or festival; films and other info available here.

A many-splendored thing 3: Filmart and filmfans

The annual Hong Kong Filmart is a trade show for all aspects of film/TV production and distribution. As in past years it commands several floors of the Convention and Exposition Center, shown in yesterday’s entry. There are many screenings (thinly attended) but the main business is dealing. Representatives from Europe and Asia meet and greet in their display spaces, or more often in restaurants and hotel rooms. Here are some snapshots from the floor of the market, which I managed to visit on Wednesday.

The cheerful Park Jiyin gave me some publications and DVDs from the Korean Film Council. She had read Film Art in her university courses!

Sanrio’s display areas were pretty nifty.

On the Filmart floor I again ran into King Wei-chu, brandishing yet another of his poster treasures while we talked with Ip File, a publicity executive for Celestial Pictures (current owners of the Shaw film library). Mr. Ip also worked as an assistant director to Chor Yuen, one of the best Hong Kong directors of the 1950s-1970s.

After cruising Filmart I caught the trade screening of Twins Mission, a goofy but likeable Hong Kong film by martial arts choreographer Kong Tao-hoi. Twins, in case you don’t know, are, or is, a pair of girl pop singers who have made some films before this, notably The Twins Effect (2003). In this entry, Twins are now trapeze artists, and they encounter a squad of kung-fu killers, all themselves either male or female twins. It’s gradually revealed that our Twins were trained in the martial arts along with many other twins…by kung-fu masters who are twins. Confused yet? Given that our Twins don’t resemble one another, the premise seems a sendup of the very idea of twins and, er, Twins.

The agreeable fight sequences are enhanced by digital effects; my favorite passage includes a moment when a spinning blade trims one girl’s eyelashes. There’s a mawkish subplot about a little kid with cancer, but the presence of Sammo Hung and Yuen Wah, who literally plays his own evil twin, more than makes up for it.

A sequel seems already to be shot. This movie, released about a month ago, ends without resolving the plot, and then we’re asked to watch out the rest of the story. Maybe the next installment will develop the subplot involving Sam Lee overacting as a mainland cop, a trail that leads nowhere here. Morever, the 35mm print I saw jumped from scarily sharp HD footage (every pore on the face all too crisp) to fairly poor digitized stuff to soft, sometimes out-of-focus 35 footage. Did they change formats partway through the shoot?

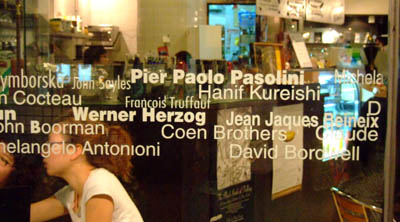

Yes, I learned later that night. I met Grady Hendrix and Goran Topalovic, directors of the New York Asian Film Festival (aka Subway Cinema), for drinks at the movie-themed coffeeshop/ bookstore Kubrick. They bought books, I bought books, then we sat outside chatting. Soon Ryan Law joined us. Ryan has recently expanded the server for the Hong Kong Movie Database, of which he’s the founder and mainstay.

Ryan, Grady, and Goran

Ryan said that for reasons of economy, it’s become very common for HK movies to mix analog and digital formats. He said that in fact Twins Mission used film, HD, and Betacam!

Leisurely talk on a balmy spring night was a good ending to a full but unhurried day, and I came back to write the blog you see now. Tomorrow: more film viewing and a visit to a night shoot of Johnnie To’s installment of Triangle.

Snakes, no, Borat, yes: Not all Internet publicity is the same

Kristin here–

This past summer I had my first experience of being quoted as a pundit in a major newspaper. The Los Angeles Times was planning a story on the internet buzz around Snakes on a Plane and more specifically around the fact that some of that buzz had actually influenced New Line to change the film.

In late July I had completed the final revision and updating on The Frodo Franchise. Two chapters cover the official and unofficial internet publicity for The Lord of the Rings. The last thing I had added to those chapters was a reference to the Snakes internet phenomenon—which was still ongoing, of course, since the film was not released until August 18. The connection is closer than it may appear, since New Line distributed both films.

Dawn Chmielewski, of the LA Times, got wind of my work on fans and the internet. She called me, and we had a pleasant 40-minute conversation. The result was one pretty uncontroversial statement from me near the end of the story, describing how studios have a mixed attitude toward fan sites on the internet: “It is a phenomenon where the studios are having to keep a delicate balance between, on the one hand, wanting to use this enormous potential for publicity, and on the other hand have to control over copyrighted materials and over spoilers.”

This story was part of the huge amount of attention paid to the Snakes phenomenon, with Brian Finkelstein, webmaster of the main fan site, Snakes on a Blog, widely quoted about how New Line had cooperated with him and even invited him to LA for the premiere. One of the main points of interest to the media was that New Line had added a line of dialogue that had originated on a fan site for Samuel L. Jackson’s character. The studio also added some sex and gore, moving the film’s rating from PG-13 to R.

Fans’ influencing films was not entirely new by this point. After The Fellowship of the Ring came out in 2001, two fans elevated a non-speaking elf extra from the Council of Elrond to fame by dubbing him “Figwit” and starting a website devoted to him. As a salute to the fans, the filmmakers brought the extra back and gave him one line to say in The Return of the King, where he is credited as an “Elf escort.” That phenomenon, however, didn’t get much notice beyond fan circles. The Snakes revisions got far more attention.

Much was made of the fact that industry officials were eager to see whether wide internet buzz—especially when covered by mainstream news media—would translate into boffo box-office figures. As we all know by now, Snakes was a deemed a failure. New Line said that its opening gross was typical for a low-budget genre film. Snakes cost a reported $33 million. Ultimately it took $34 million in the domestic market and a total of just under $60 million internationally. I suspect that New Line spent a great deal more on advertising that it ordinarily would have, hoping in vain to expand the enthusiasm. The film’s box office takings would certainly not bring in a profit, but doubtless New Line hopes for better things on DVD. That DVD was released on January 2, so no sales figures are available yet, but the widescreen edition is doing reasonably well at #19 on Amazon.

The film’s disappointing ticket sales led to questions. Why would fans spend so much time on the internet and generate such hype and then not go to the film? After all, fans created parody posters, music videos, comic strips, and photos on their sites, as well as designing T-shirts and other mock-licensed products. (The DVD supplement “Snakes on a Blog” presents a generous sampling of such homages; see also Snakes on Stuff.com.) And if that much free hype—even aided and abetted by the studio—didn’t translate into ticket sales, was the internet all that useful for publicizing films?

The film’s disappointing ticket sales led to questions. Why would fans spend so much time on the internet and generate such hype and then not go to the film? After all, fans created parody posters, music videos, comic strips, and photos on their sites, as well as designing T-shirts and other mock-licensed products. (The DVD supplement “Snakes on a Blog” presents a generous sampling of such homages; see also Snakes on Stuff.com.) And if that much free hype—even aided and abetted by the studio—didn’t translate into ticket sales, was the internet all that useful for publicizing films?

Of course fan sites had already proven their worth for New Line’s own Austin Powers: Man of Mystery and Lord of the Rings. Other films had benefited from free fan labor and enthusiasm. Famously The Blair Witch Project became a massive hit primarily because of the internet. But anytime a hitherto dependable formula results in even a single failure, the studio publicity departments go into a tizzy of doubt. It’s true of genres, stars, and just about any other factor you can name. Snakes fails, so maybe the internet isn’t that powerful a publicity force.

Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan came along to confuse things even further. It, too, had a huge fan presence on the internet. In this case, the main activity was the posting of clips on YouTube. Well before the film was released on November 3, deleted footage and some scenes from the film were showing up. There were about 2000 by then, and as of yesterday a search for “Borat” on YouTube yielded 6,293 items.

It came to be a joke on the internet: “What is the difference between Google and Borat? The latter knows how to make money from YouTube.” (“Borat” was recently reported to be one of the top search terms on Google in 2006.) Webmasters and chat-room denizens who were already fans of Sacha Baron Cohen from Da Ali G Show, where the Borat character originated, promoted the film. The internet buzz probably led to more coverage of the film in mainstream infotainment outlets than would have otherwise occurred.

Borat’s reported budget was $18 million. To date, it has grossed $126 million domestically and a total of $241 million worldwide.

The timing of the two events triggered much press coverage and show-business hand-wringing. What did it all mean? Is the fan-based sector of the internet good for films or not?

This isn’t some idle question as far as the industry is concerned. Twentieth Century Fox wisely encouraged all the Borat uploaders at YouTube. Far from threatening to sue over copyright, they leaked footage. Then, however, shortly before the film’s release, audience research (that highly dubious tool in which studios put such faith) revealed that many members of the public had never heard of Borat. What to do? At the last minute Fox cut back the number of theaters in which the film would be shown. Did anyone else in the world think that was a good idea?

Back on November 11, with Borat freshly successful and speculation about internet coverage rife, I promised to explore how the two films differed when it came to internet hype and success. That would be possible to do without seeing either film. I saw both, though. Like many others, I watched Borat in a theater and Snakes on DVD.

Others have offered reasons for the difference. On NPR, Kim Masters made some plausible observations. Snakes, she points out, “was a film with a very broad concept—Samuel L. Jackson battles snakes on a plane. The buzz took off on thousands of Web sites as the film became the butt of many jokes. The problem is that the movie wasn’t really meant to be that funny. Borat, on the other hand, is meant to be funny.” True enough. In fact, Snakes has a weird mixture of tones, starting off with a highly non-humorous scene of a gangster killing a man with a baseball bat. It goes on to interject funny moments in the midst of grim ones in a seemingly random way.

Moreover, Masters claims, the buzz for Snakes “took off too fast” and in the wrong places. The sites making all the jokes and parodies weren’t the same ones that horror fans frequent, and the humor may in fact have created a negative reaction among what would ordinarily have been the film’s target audience. Borat had no such problem. Fans of comedy and especially of Cohen spread the word to likeminded fans through what is termed viral marketing in the publicity business.

All true, and yet, having studied Lord of the Rings fan sites for a long time, I think there was another crucial factor that never occurred to the anxious studios. That factor was what the fans were doing with the films on their websites, in chat rooms, and on YouTube.

Many popular films, especially in genres like fantasy, science fiction, action, and horror, generate fanfiction, fanart, spoofs, and other creative responses. Snakes on a Plane offered the inspiration for all sorts of clever writing and drawing and videomaking through its title alone. As was pointed out over and over, from that title and the casting of Jackson, everyone knew what the film would be like. It could be parodied without even being seen. Indeed, I suspect that after months of posting and mutually enjoying hundreds of amusing riffs on “Snakes on a Plane,” many fans realized that they could never have as much fun watching the film as they had playing around with its title and concept. It had never been the movie itself they were really interested in.

Borat’s full, unwieldy title was also an attention-getter, but no one could possibly predict much about the film from it, let alone parody it. Here the focus was primarily on how funny Cohen was as Borat and how funny the film was going to be. What circulated were samples that seemed to prove exactly that. People would go to this film and have more fun than they could possibly make for themselves by messing around on the internet with its title. The words “snakes on a plane” could inspire just about anybody with a creative bone in their body, but only Cohen could do Borat.

Print and broadcast media spread the same message. For Snakes, they had zeroed in on the internet coverage and stuck with that. End message: there is a lot of fan attention being paid to a rather silly-sounding film. For Borat, they had Cohen appear as an interviewee.

Cohen brilliantly manipulated the infotainment outlets, especially the chat shows, by appearing in character as Borat. As the film’s release approached, Cohen was a hot property, a ratings booster. Talk-show hosts and soft-news reporters presumably couldn’t alienate him by insisting that he speak as himself. Maybe they didn’t want to. As a result, three things happened. First, the endlessly talkative Borat dominated each interview. On The Daily Show, the ordinarily in-charge Jon Stewart was totally unable to control the situation and frequently cracked up, once badly enough that he had to turn his back on the audience momentarily.

The second result was that each appearance by “Borat,” supposedly there to talk about the film, ended up being a hilarious performance by Cohen, ad-libbing on everything around him—the chairs, the coffee mugs, the cameras, the audience. Spectators ended up with one impression about the film: it was about this incredibly funny guy doing incredibly funny things.

Third, there could be no discussion of the less savory aspects of Borat, the ones that mostly surfaced after the film was already a hit. These included allegations that people had been manipulated by false claims into signing consent forms and “performing” in the film. One has to suspect that when Cohen was explaining his project to them, he may have appeared as his own rational self and not in the wild-and-crazy persona of Borat. The stylistics of the film itself betray many points at which encounters with real people could have been manipulated. Who knows what the crowds at the rodeo where Borat butchers the national anthem were actually reacting to? None of their responses is ever visible in the shots of Borat. How many non-bigoted interviews were thrown out for every bigoted one that could be used?

The point is, though, that the interviews were like the internet clips, furnishing more evidence of how entertaining the film would be. Borat could provide a sort of creativity that was all his own, and fans could never imagine it ahead of seeing the film or create a more fun version of it themselves. Many, many of the people who posted or read stuff about Borat on the internet went to the film.

Ultimately the studios have yet to emerge from their early love-hate relationship with fan-generated publicity on the internet. They dread the early posting of bad reviews and crave good ones, naturally. But they still seem to believe that most other online publicity means the same thing: eyeballs on monitors should equal bottoms in theater seats. Publicists have not yet grasped that fans don’t go to the web just to talk about films and learn about films. They do things with films, and different films inspire different sorts of activities. Those different activities may or may not mean that the fan ultimately wants to see the film itself.

In most cases they probably do end up seeing the film. Snakes on a Plane is most likely an aberration, as Blair Witch was. But Snakes does prove one other thing. Fawning attention paid to the webmasters and bloggers who launch these unofficial campaigns is no guarantee of success. The “Snakes on a Blog” supplement displays some interesting aspects of New Line’s wooing of the main fans involved in the online hype. The documentary seems to have been made at just about the time Snakes was released. It ends with the bloggers, by invitation, on the red carpet at the Chinese Theater for the film’s premiere and later at the bloggers’ party put on by New Line at a bar. The whole tone is very enthusiastic about the internet’s impact on the film’s success; there is no sense that the film will disappoint and raise doubts about the value of fan publicity. There is also the implicit suggestion that fans starting future film-related blogs might get similar encouragement and hospitality from studios.

Clearly no amount of studio cooperation and attention to fans’ interests will make a film succeed if the right blend of ingredients isn’t there. Nevertheless, fans’ enthusiasm and willingness to spend great amounts of time, effort, and even their own money to create what amounts to free online publicity for films is of incalculable value to the studios. Yet for the most part those studios are still making only grudging, limited use of this amazing resource. The resentment they garner from fans as a result may be squandering part of that resource’s potential.

Gradually, though, the studios are giving up their policy of stifling the fans by making vague threats about copyright and trademark violations. If they go further and actually learn how fans use all the amazing access the internet has given them, maybe movie executives can relax and recognize the obvious answer to the current debate: Yes, fans on the internet are good for the movie business.

What Are Aca/Fans?

Kristin here–

There was a time when studying film fans was something sociologists or film-industry marketing people did. Sociologists wanted to find out why fans behaved the way they did because it was interesting and often strange, and the industry wanted to figure out fan behavior so they could sell movies to them more effectively.

Then, a couple of decades ago, a new kind of expert came along: the fans themselves. People who had gone to the university to study film, television, literature, or other aspects of popular culture gradually realized that they could study themselves, their kids, and the people they met at fan conventions and later on the internet.

Prof. Henry Jenkins did not originate the study of fandoms, but he has been perhaps the most influential “aca/fan,” as he terms himself on his blog. (The term “fan academic” also gets used to describe this new field of study.) These days books and articles and web publications about fandoms are proliferating, but just about any of them will cite Henry’s seminal 1992 book, Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture (Routledge).

Henry doesn’t study fans to find out what makes them tick. He knows that. He’s one of them, a participant in fan cons, a player of video games, an explorer of the multimedia sagas like those of Star Trek and The Matrix that have grown up in the age of franchise culture. He received his doctorate here at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where David was his dissertation advisor, and we have followed his career, as they say, with great interest. Straight out of the gate he was hired by MIT, where he is now the Director of the MIT Comparative Media Studies Program and the Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities. (Read more about his prolific and wide-ranging activities at his blog.)

This year two books by Henry appeared: Fans, Bloggers, and Gamers: Exploring Participatory Culture and Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide (both New York University Press). Given that my The Frodo Franchise has chapters on Lord of the Rings video games and fan culture on the Internet, I thought I’d start with the first. Henry assured me, however, that Convergence Culture represented a more current and probably more relevant overview, so I started with it instead.

This terrific book uses a series of case studies to give an overview of how digital media have expanded the possibilities for participatory fan culture. It also shows how the producers of popular culture have reacted to this new empowerment of the consumers. Only two chapters focus on films: “Searching for the Origami Unicorn: The Matrix and Transmedia Storytelling” and “Quentin Tarantino’s Star Wars? Grassroots Creativity Meets the Media Industry.” In the modern entertainment industry, however, films are increasingly linked to other media, and no one has a better grasp of the overall relationship among popular media than Henry.

Convergence Culture is unusual, perhaps unique, in offering an overview of the entertainment industry from the perspective both of the big corporations that control popular media creations and of the fans, who often appropriate those creations for their own purposes. Much of the book depends on interviews with fans and executives alike. Henry is evenhanded in dealing with both points of view—except when the big firms try to stifle fan creativity through intimidation and the invocation of copyright and trademark control.

Here Henry is firmly on the side of the fans. The chapter on Star Wars mentioned above reviews the love-hate relationship George Lucas has had with fan websites that post innumerable works derived from his saga. Another chapter, “Why Heather Can Write,” details how Warner Bros. attempted to squelch fan creativity based on the Harry Potter series. Henry provides a cogent argument for rewriting fair-use laws to accommodate amateur, not-for-profit activities that utilize characters and situations from copyrighted works.

So am I an aca/fan, too? I wouldn’t exactly describe myself as one, though in this new book I have dabbled in that approach, meeting many fellow Lord of the Rings fans in person and in cyberspace. One has to admire members of the various fandoms and the amount of time and effort they are willing to put into keeping themselves and others informed about the objects of their fascination. They also lovingly create their own works (fanfiction, fanart, machinema, RPGs, and so on) derived from their favorite books, games, movies, TV shows, and comics. Most of the results aren’t masterpieces, of course, but that’s true of “real” artworks created by professionals and aspiring professionals as well. If enough of just about anything gets made, some of it is bound to be good. I’ve found some excellent Lord of the Rings fanfiction among the many conventional, sometimes nearly unreadable tales I have sampled. And Chocolate Cake City’s Brokeback to the Future demonstrates what David likes to describe as “the spontaneous genius of the American people” (usually in reference to the speed with which any significant event generates a body of tasteless jokes, or, in this case, parodies).

For all the attempts to analyze audiences through questionnaires and interviews and other traditional methods, Henry shows that the best way to understand fans is as an insider. The aca/fan approach is spreading as the study of popular media and fandoms gains legitimacy within academe, and it is lucky to have an enthusiastic, intelligent pioneer in Henry Jenkins.