Archive for the 'Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato' Category

Arrivederci Ritrovato

The three chiefs of Cinema Ritrovato: Peter von Bagh and Gianluca Farinelli strategize, while Guy Borlée does some heavy lifting.

Our last days at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato were as busy as the first ones. Inevitably, choices, choices. Invasion of the Body Snatchers in a rare SuperScope print, or Asta Nielsen as Hamlet? Emilio Fernandez’s melodrama Enamorada (1946) or a 1907 version of Little Red Riding Hood, with a big dog playing the Wolf? You can’t see it all, but we offer some notes on some of the choices we made.

I can’t say that I am a great fan of Frank Borzage’s films of the 1930s and 1940s. For me his great period was the mid- to late 1920s. 7th Heaven (1927) somehow manages to climb beyond its blatant sentimentality, much as the hero and heroine ascend the stairs of their tenement apartment house, and earns our emotional investment in their transcendent love. For me, Lazybones (1925) and Lucky Star (1929) were the revelations of the Borzage retrospective during the 1992 Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone. It is a true pity that both remain largely unknown.

Borzage’s No Greater Glory (1934) was shown in a stunning print supplied by Sony Columbia. It didn’t fall into any of this year’s themes but was simply one of the “Ritrovati & Restaurati” items. The film deals with rival youth gangs in Budapest who organize themselves along strict military lines. Purportedly an anti-war tale, it manages to make the self-imposed discipline and even gallantry of the boys seem almost redemptive. I found the young hero, a scrawny but brave lad who struggles to be worthy of promotion within the ranks of his chosen gang, a bit too calculated to tug at the heartstrings. Still, it was entertaining, and the print showed it—and especially Joseph H. August’s cinematography—off to the best possible advantage. (KT)

While Kristin was watching Borzage, I decided to revisit Ilya Trauberg’s Goluboi Express (1929), one of the least known of the Soviet Montage films. Like Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia, it’s an attack on Western imperialism. Chinese, many sold into servitude, are packed into the rear cars of the train, while colonialists loll around up front. Two western soldiers of fortune attack a Chinese girl, and a young Chinese tries to defend her. This launches a prolonged battle and chase while the train roars on. By 1929, Trauberg had absorbed the lessons in cutting taught by Kuleshov, Eisenstein, and Pudovkin, and he adds his own imaginative touches. The taut construction and torrential editing (over 1400 shots in less than an hour) create an electrifying experience.

This particular version is an intriguing rarity. In his introduction, Bernard Eisenschitz explained that Soviet authorities persuaded Abel Gance to distribute the film in France. Gance recut it to avoid censorship, and he commissioned musical accompaniment by Edmund Meisel, the experimental composer who scored Battleship Potemkin. Meisel’s score amplifies and sharpens Trauberg’s hammering visuals. (DB)

The book room was running for only about half the festival, so I was glad I nabbed my consumer durables early. Many high points, including a fascinating DVD collection of Marey films, but the most memorable, if only because of the struggle to carry it back home, is This Film is Dangerous. Published by the International Federation of Film Archives, this colossal book appears to present everything you wanted to know about this incendiary filmstock. It includes discussions of how nitrate came to be an ingredient of film, how the nitrate preservation movement (“Nitrate won’t wait”) started, case histories of restorations, poems in praise of nitrate, a chronology of nitrate fires, and an anonymous contribution called “Nitrate Pussy.” In all, virtually a film geek’s bathroom book, although its bulk demands a large lap. It doesn’t yet seem to be available on the FIAF website, but it should be soon.

Speaking of swag and plunder, Dan Nissen of the Danish Film Institute kindly gave me a copy of their latest DVD publication, the first of several volumes devoted to Jørgen Leth. It’s a handsome production and sure to increase interest in the man behind The Perfect Human and the target of Lars von Trier’s painstaking abuse in The Five Obstructions. It’s available at the DFI website. (DB)

Although Michael Curtiz’s 1929 epic Noah’s Ark has been shown at various festivals in recent years, I somehow had always managed to miss it. Perhaps this was just as well, since the print shown in Bologna as part of the salute to Curtiz is longer than most and has the original sound restored from the Vitaphone records. (More often the film has been shown in its silent version.) Piecing together bits from several release prints held in different archives, something approximating the 1929 release version has been reassembled and matched to the sound. The credits in the program—“Print restored by YCM laboratories, funded by Turner Entertainment Company and AT&T in collaboration with La Cinémathèque Française and The Library of Congress”—hints at the complexity of the task.

Like The Jazz Singer and other early talkies, Noah’s Ark has long stretches of purely musical accompaniment. At intervals, though, characters suddenly start speaking, usually at the lugubrious pace typical of performances at the dawn of sound. The effect is startling, especially when the transition happens within a scene. Such switches proved jarring to the reviewers of the day, but the chance to see a film hovering between silent and sound can be fascinating to a modern viewer. The pacifist message of Noah’s Ark reflects a general anti-war sentiment in Hollywood films of the 1920s and 1930s—a healthy reminder of a day when the majority of good, patriotic Americans could take a dim view of warfare. The film’s ending, in fact, optimistically declares that the Great War had put an end to all wars. (KT)

Having written a book on Ernst Lubitsch’s silent features, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, I was particularly interested in a dossier on the director. It included a reconstruction of Die Flamme (1922), of which only one reel survives, using publicity photos, set designs, and descriptive intertitles. Though still short at only 44 minutes, this version gives a good sense of the plot, which was certainly not evident from the existing footage.

We have long known that Lubitsch’s intended first project in Hollywood was to be a version of Faust with Mary Pickford as Marguerite. That fell through, but it went far enough that screen tests were made. Twelve minutes of tests for a series of actors trying out for the part of Mephistopheles were shown. These were not exactly a revelation, but they do shed light on this transitional moment in the director’s career. (KT)

What do we do with a terrible movie by a sublime filmmaker? I’d argue that at least three directors achieved greatness in the years before 1920: D. W. Griffith, Louis Feuillade, and Victor Sjöström. Sjöström’s Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (1917), The Girl from Stormycroft (1917), The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), and Sons of Ingmar (1919) remain deeply moving and cinematically inventive. Sjöström moved smoothly from the fixed camera, long-take “tableau” style of the early 1910s to profound mastery of continuity editing on the US model only a few years later. He continued into the 1920s with such key American films as The Scarlet Letter (1926) and The Wind (1928).

So it’s saddening to report that A Lady to Love (1930) is a turkey. Edward G. Robinson, in full hambone overreach, plays an Italian-American grape farmer who seems to be flourishing despite the Volstead Act. Tony brings a down-at-heel waitress from the big city to be his wife, and she grows to love him, despite a little indiscretion involving Tony’s best friend. The sort of inert stage adaptation that gave talkies a bad name, A Lady to Love is solely for completists (of which Cinema Ritrovato boasts many). It was Sjöström’s last Hollywood picture. (DB)

The programs of 1907 films continued to yield treasures. Max Linder’s career got going that year, and he had not yet settled into the debonair, top-hatted persona that would within a few years become so familiar. In the simple and not terribly funny Débuts d’un patineur, he plays a novice ice-skater reduced to tears at by the film’s end, and in the more amusing Pitou bonne d’enfants Linder is a bumbling soldier who loses a baby confided to his care by his nursemaid sweetheart. The same program contained Louis Feuillade’s ever-popular Le Thé chez la concierge, where the guests start carousing so loudly that they drown out the bell rung by tenants trying to get into the house.

There were many early attempts to record synchronous sound, though all too often the accompanying discs have been lost even if the image track survives. The 1907 films contained a few such, but one, La Marseillaise, had its singer’s original voice, remarkably clear and perfectly synchronized. The result was an unusually poignant and vivid sense of a link to a hundred-year-old performance, an immediacy that went beyond what most silent films can convey, wonderful though they might be.

A familiar but welcome short was La course aux potirons (“The Pumpkin Chase”), one of the great entries in the very familiar genre of the day, the chase film. Special effects allow a wagon-load of pumpkins (looking like they were probably constructed from old tires) to bounce along city streets, up a chimney, and through windows, followed by the usual growing group of passersby. The inclusion of a donkey, duly hauled through the windows and up the chimney, makes the whole pursuit far funnier than in most such films.

Finally, the inclusion of a series of films about bomb-throwing anarchists, another common genre of the day, reminds us that the current international situation is not altogether a new one. (KT)

The DVD awards singled out efforts to making unusual cinema available in the DVD format. The top prize, Best DVD, was won by the Ernst Lubitsch collection, from Transitfilm and the Murnau Stiftung (available, with some variations, on Kino in the US). The committee commended it as “a model in the elegant packaging of rare materials in a form that is certain to attract new audiences.”

Anke Wilkening of the Murnau Stiftung accepts the award for best DVD.

Other awards: L’amore in città (Minerva, Italy), Best discovery; Seven Samurai (Criterion, US), Best Extras; the series on German cinema published by the Munich Film Archive, Best Series; and Akerman films of the 1970s (Carlotta, France), the French Naruse set (Wild Side) and the British Naruse set (Eureka), Best Box Sets.

Peter von Bagh commented that DVD producers are continuing the traditional work of film archives, and they often go beyond what archives can afford to tackle. Ironically, we sometimes find ourselves in the position of having excellent DVD versions of films that don’t exist in equally good prints. (DB)

Finally, some snapshots. Glancing around the book room, you’ll see Sawako Ogawa and Hiroshi Komatsu pouncing on items.

Not to be left behind, Janet Bergstrom and Richard Koszarski display Janet’s find.

Every year, Frank Kessler‘s birthday occurs during Ritrovato; this year was his fiftieth, and so Sabine Lenk made it a special treat.

At another meal, Danish film archivist Thomas Christensen, who really ought to know better, fends off the camera’s magical powers.

Same meal: shellfish and pasta sacrificed in a good cause.

Danish film historian Casper Tybjerg and Kristin sample gelato. Later I ate the one in the middle.

On the final evening, the film cans are wheeled out. Ci vediamo l’anno prossimo!

Another Bologna briefing

More notes and notions from Cinema Ritrovato, all from DB:

Could you make a movie today about a farm girl who becomes a concert pianist under the sway of a womanizing egomaniac? The slightly nutty I’ve Always Loved You (1946) displays Frank Borzage’s usual faith in the way lovers communicate by spiritual ESP, this time aided by Rachmaninoff. Borzage talked the low-end Republic studio into this expensive project, and the result, though marred by strained performances, looks great in a glowing restoration by UCLA. A teenage André Previn darts through, and for once someone playing the piano onscreen (in this case Catherine McCloud) looks skillful. (The playback renditions were those of Arthur Rubinstein, credited as “the world’s greatest pianist.”) The title is perfectly ambiguous, since it could refer to any character’s attitude toward almost any other.

Travel delays prevented Ben Gazzara from introducing the fine print of Anatomy of a Murder. Too bad. It would be fascinating to hear how he developed his disturbing portrayal of an accused killer under Preminger’s notoriously dictatorial direction. But Gazzara did participate in an interview with Peter von Bagh that led into a screening of a beautiful restoration of Jack Garfein’s The Strange One (aka End as a Man).

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

Gazzara talked of coming out of the Actors Studio after the success of Marlon Brando, a tremendous influence on Gazzara’s generation. He recalled that he was in the same Studio class as James Dean, Steve McQueen, and Paul Newman. What was the Method? “It’s a word I never use. I don’t know what it means. . . It gave you things to fall back on” if you couldn’t come to grips with the script material.

He said that he loved Hollywood acting of the studio era: Gable, Grant, Tracy, and Stewart remain fresh and modern. When he saw Meet John Doe, he realized that Gary Cooper used his own version of the Method: “He did very little, but he did everything.”

Gazzara said that seeing Faces (1968) drew him to Cassavetes. “I was mesmerized. I was so jealous. I thought, I’ve gotta work with this man.” A year later he made Husbands. Cassavetes was very supportive, always “waiting for surprises.” He was laughing in enjoyment behind the camera, encouraging his players. “All you did was safe, and you could do no wrong.”

The Strange One, set in a Southern military academy, was Gazzara’s first film. He was offered the part of the cadet who eventually leads a revolt against the Machiavellian cadet Jocko De Paris. But Gazzara said that he wanted to play DeParis because “he got all the laughs.” George Peppard wound up with the good guy role. Though the film seems to me confused on several dimensions, Gazzara revels in the showy part of a soft-spoken, eminently reasonable sociopath. As in Anatomy of a Murder, he makes gently menacing use of a cigarette holder.

In the early 1930s, Japanese companies explored the possibility of exporting their films to Europe and the US. One result of these initiatives was Nippon: Liebe und Leidenschaft in Japan, a 1932 German compilation created by Carl Koch. It originally consisted of three films from the Shochiku studio, condensed and supplied with German intertitles. The original films were silent, so, oddly enough, synced Japanese dialogue was added.

In the version screened here, only two episodes were presented. What beauties they were! Since many of the 1920s and 1930s Japanese films that survive look quite weatherbeaten, it was wonderful to see, in the print from the Cinémathèque Suisse, how gorgeous quite ordinary movies from this era could be.

The first story, Kaito samimaro (orig. 1928), deals with a young samurai rescuing his beloved from the clutches of a corrupt priest. Brisk and beautifully shot, it came to the sort of frothing swordplay climax typical of the period—rapid cutting, dynamic tracking, and slashing assaults aimed at the camera. Kagaribi (1928), about a young vassal betrayed by his corrupt lord, likewise ended with a protracted action scene capped by a jolting climax. A prolonged tracking shot follows the young man’s former lover as she backs away from him, but then we cut to a full shot. With a single stroke he kills her, jaggedly ripping a paper door in his follow-through. Both stand motionless for a moment before she falls. A conventional finish, but no less eye-smiting for that. For more on the power of this action-cinema tradition, see an earlier entry on this site.

There are no fewer than ten flashbacks in the 1950 Swedish film Flicka och Hyacinter (Girl with the Hyacinths, above). Peter von Bagh’s Bologna programming has often highlighted Nordic work that’s little known outside the region, such as this engrossing post-Kane exercise in probing a dead person’s life. Teasingly directed by Hasse Ekman, the interlocking flashbacks would be savored by today’s puzzle-film aficionados, and the movie’s equivalent of Rosebud is genuinely surprising. The twist would never have been permitted in Hollywood of that era.

Kristin and I hope to post one more entry, probably soon after Ritrovato’s final session on Saturday. Lots more to report–Lubitsch, Borzage, Chaplin (of course), etc. For now, a glimpse of the official names of the Cineteca’s two screening rooms…

Cinema bolognese

Cinema Ritrovato, a festival of rediscovered and restored films, is now in its twenty-first year. We visited its two previous installments, and we found it one of the most hugely enjoyable festivals on the calendar. Where else can you see films from 1907, Richard Fleischer’s Violent Saturday (1955), and a tribute to Ben Gazzara in a single week? Then there are the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, which attract hundreds of locals. The city plays host magnificently, with plenty of fine restaurants and perpetually cheerful people.

Mounting hundreds of screenings and panels is an enormous effort, but Gianluca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, Peter von Bagh, and all their colleagues have made it look easy. (The word sprezzatura comes to mind.) Here are our impressions from the first half of the event.

The home base is the Cineteca di Bologna, the local film archive. It’s located in a wide, quiet courtyard. It houses a large library and meeting rooms, along with two cinemas. During the festival, the Lumiere 1 auditorium specializes in silent screenings with piano accompaniment, while Lumiere 2 presents sound films. Widescreen titles and big events are reserved for the Arlecchino, a big, comfortable commercial theatre built in the era of roadshows and CinemaScope.

Organizing such a mixed program is more difficult in certain ways than presenting an event involving contemporary films, which are moving through the festival circuit already. Ritrovato must find good prints of titles that fit the year’s themes and also coordinate the ongoing efforts of archives that are restoring films.

A good example is a remarkable project overseen by Alexander Horwath of the Austrian Film Museum. One of the most famous lost films in US history is Josef von Sternberg’s 1929 movie The Case of Lena Smith. In 2003, Japanese scholar Komatsu Hiroshi found a fragment, in very good condition, in China. On the basis of this, Horwath and his collaborators created a wonderful book that reconstructs the film. It includes a detailed shot breakdown (based on one published in Japan during the film’s release), along with gorgeous stills, script extracts, summaries of critical reception in various countries, and essays about the film’s place in history.

The fragment, previously screened at the Giornate del Cinema Muto last fall, was tantalizing. Lena and her friend Pepi are in the Prater, Vienna’s dazzling amusement park, and they are eyed by two young officers. The women watch some of the sideshow entertainments before darting away, the officers in pursuit. Several of the shots evoke the heady atmosphere of the park, with prismatic, superimposed images of the sideshow attractions and—typical von Sternberg—a spinning ride providing pulsating visions of the crowd.

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

In his panel presentation, Horwath stressed that the book couldn’t have been done without the cooperation of researchers around the world. The multilingual volume is to be made available in the UK and the US in 2008. It is a splendid example of what archives and scholars can accomplish working together, with festivals like Cinema Ritrovato providing a forum for rediscoveries. The book is available already at the archive’s website and will be distributed later this year by Wallflower in the UK and Columbia University Press in North America. (DB)

One of the threads of this year’s festival is the early US career of Michael Curtiz. The Strange Love of Molly Louvain (1932) is an energetic Warners crook melodrama. Starring Ann Dvorak and the ever-annoying Lee Tracy, the film displays Curtiz’s characteristically staccato direction. The scenes with hard-bitten reporters use overlapping dialogue in a manner that prefigures His Girl Friday. Rarer was The Third Degree (1926), an early instance of Europe’s “International Style” infiltrating Hollywood. For his first Warners project, Curtiz fills an implausible mother-daughter melodrama with cloudy superimpositions, canted angles, florid tracking shots, oddball angles, extreme close-ups, and frantic montages played with prismatic lenses. Richard Koszarski gave an amusing and helpful introduction. (DB)

One attractive constant of the Ritrovato is a series of short films from 100 years ago. Thus when we first attended in 2005, there were groups of shorts from 1905. As we progress through the early years of the current century, we go in parallel through the early years of the previous one. Each day one or two small groups of 1907 films have been shown, grouped by country or genre. These included some familiar items, like the poignant Le Bagne des gosses (“Children’s Prison,” Pathé) and the amusing British chase film, That Fatal Sneeze (directed by Lewis Fitzhamon). I have run across references to early Westerns made in Europe but had not seen any from this early period. Les Apaches du Far-West (produced by Pathé) is as unauthentic as one might predict, with the cowboys riding on English-style saddles and the shoot-outs with the Apaches taking place in bucolic fields and woods that are clearly in France, not the West. (KT)

A major new initiative for international film preservation was announced in May at the Cannes Film Festival. The World Cinema Foundation was founded by Martin Scorsese, and its advisory board contains such major filmmakers as Abbas Kiarostami, Elia Suleiman, Walter Salles, and Wim Wenders. The goal is to restore films made in nations that lack the archival facilities to do so locally.

The Moroccan Transes (El Hal, 1981), directed by Ahmed El Maanouni, is the new foundation’s first restoration, and it was introduced by the director and by its producer, Izza Genini. The titles crediting Giorgio Armani, Cartier, and Qatar Airlines as sponsors raised some surprised laughter in the audience, but if Scorsese and his colleagues can draw funding from such sources into film restoration, all the better. Transes is partly a concert film and partly a history of a band that became popular in the 1970s by expressing young people’s frustrations and rebelliousness. The big concert that begins and ends the film is exhilarating in its depiction of the crowd’s enthusiasm—but chilling as well as soldiers patrol the audience and occasionally suppress the more demonstrative spectators. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Another major theme is the ever-popular star Asta Nielsen. Again, items familiar from other retrospectives are mixed with new discoveries. Karola Gramann has curated the series and plans to restore other Nielsen films, either new discoveries or better prints of familiar films. Zapatas Bande (1913-14), for example, existed before, but now a color print has been made based on tinting notations on an existing black-and-white copy. It’s a slight item, a casual tale of filmmakers getting into trouble while shooting an adventure movie, but it allows Nielsen to get away from her usual melodramas and display her range as a comic actor. (KT)

Our first visit to Italy for a film festival was in 1986, when Le Gionate del Cinema Muto, in Pordenone, presented a vast retrospective of Scandinavian cinema from the pre-1919 era. One of the major revelations was that alongside Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjöström, there was a third great Swedish director during the silent era, Georg af Klerker. The event also brought home to the audience one of the great tragedies of cinema history, the loss of many of Stiller’s and Sjöström’s films in an archive fire in the 1940s.

Every now and then, another film by one of these masters surfaces. This year the Ritrovato festival showed Madame de Thèbes, a 1915 Stiller film. As too often happens, the surviving copy, a French release print discovered by Lobster Films, was incomplete. The Svenska Filminstitutet has filled it out by inserting still shots created from copyright frames deposited at the Library of Congress and by replicating the original Swedish intertitles and letters. The result, full of sumptuous decor and extravagant plot twists, gives as good an approximation of the original as is now possible. It’s one more indication that the 1910s Swedish cinema was one of the glories of the silent era. (KT)

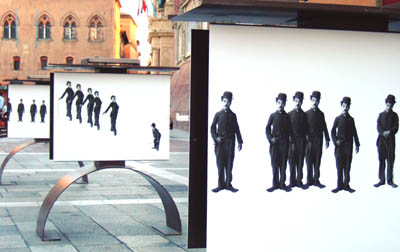

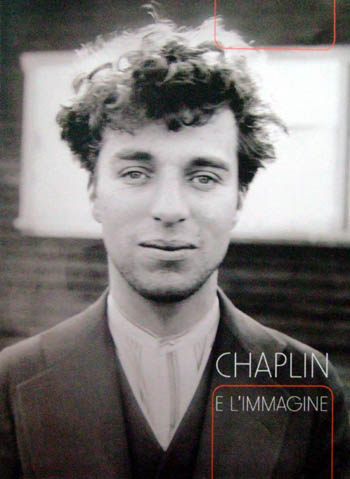

The festival has a close relation with the Charlie Chaplin estate; this is the place to come for the latest in Chaplin restorations and scholarship. Every year the festival mounts a tribute, including a superbly designed book on some aspect of Chaplin’s career. This year’s volume is a collection of rarely seen pictures, and its cover carries one of the most melancholy and haunting portraits of Charlie I’ve ever seen (up top).

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The first big event of the festival was a screening in the city’s Teatro Communale, an overpowering opera house. It was a fitting venue for The Idle Class (1921) and The Kid (1921), accompanied by orchestra. The prints were pristine, shown in a nearly square ratio. The version of The Kid was based on Chaplin’s 1971 rerelease, since that represents his final thoughts, but the Bologna gang generously tacked on the material that Chaplin chopped out—all scenes with Edna Purviance, playing the unwed mother who abandons her baby. These scenes include her uneasy meeting her old lover years after she’s achieved success. The plot turn and the regretful tone seemed to me to look forward to A Woman of Paris. This version, along with the deleted scenes, is available on the MK2 DVD release.

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

The score was by Timothy Brock, who also conducted. On the following day Brock gave an enlightening seminar on how he based his scores on original themes that Chaplin came up with. Chaplin was in the habit of working and reworking tunes at the piano, and many of his efforts were recorded. The recordings came to light three years ago, and Brock was able to integrate the tunes into his scores—sometimes linking five or six in a single passage. (DB)

A cloud was cast over our visit by the news of the death of Edward Yang (Yang Dechang). We admired his films and discussed them in Film History: An Introduction and my Figures Traced in Light. Edward was a likeable, tough-minded fellow. His films explored the effects of urbanization and politics on everyday life in Taiwan. He made his breakthrough to a broad international audience with Yi Yi (2000), but his other films, particularly Taipei Story (1985), The Terrorizers (1986), and A Brighter Summer Day (1991) are to me even more important. It’s a great loss that these aren’t easily available on DVD. When I get back to Madison and have access to pictures from my encounter with Edward in Kyoto in 1997, I hope to write a more adequate tribute. (DB)