Archive for the 'Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato' Category

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Back to the future (of movies)

DB here:

The Teatro Comunale of Bologna is an eighteenth-century opera house that was launched by a premier of a work by Glück. It has hosted massive productions of Wagner, Rossini, and Verdi, and was a favorite venue of Toscanini’s. Elegant and imposing, with box seats and an orchestra pit, it makes you feel like you’re in Senso or Liebelei.

In some years Cinema Ritrovato has secured the Teatro for gala screenings of silent films, complete with orchestral accompaniment. One show of Lady Windermere’s Fan was a delight. In another year, the hammering Meisel score for The Battleship Potemkin nearly blasted me out of my seat. I was sitting up front.

This year it was Rapsodia Satanica (1917) that got the Comunale treatment. This apparition has lost none of its exuberant morbidity, and we got to watch it with the original Pietro Mascagni score. Timothy Brock found that the original orchestra parts were lacking hundreds of tempo changes, because Mascagni himself conducted during screenings and never inserted them. Through careful testing against the film, Brock managed to create a score that brought a packed Communale audience to its feet cheering. One more testament to the power of 1910s cinema.

1915 and all that

Assunta Spina (1915).

I tried, really tried, to see other wonders from all the places and periods on display at this year’s overstuffed Ritrovato. But because of my love of ‘teens films, both American and not, I kept coming back to as many items from that era as I could squeeze in.

There was, centrally, the series Cento Anni Fa (A Hundred Years Ago), curated by Marianne Lewinsky and Giovanni Lasi. 1915 was, of course, a decisive year in American cinema, to be forever identified with Griffith’s monumental The Birth of a Nation. Standard histories would have it that this was the stroke that revealed the artistic power of cinematic storytelling. Griffith’s colossus was naturally very influential, but it wasn’t an isolated accomplishment. Earlier films, such as Weber/Smalley’s Suspense (1913), and other 1915 films–De Mille’s The Cheat and Walsh’s Regeneration in particular–are more typical stylistically of what Hollywood silent cinema would turn out to be.

Add to this list another 1915 item. If film history were an exercise in fairness, Reginald Barker would be recognized as one of the directors who set American filmmaking on its “classical” road. Working under Thomas Ince’s supervision, Barker showed a flair for economical framing, frequent changes of setup, and bold cutting within scenes. His Typhoon (1914) is at many moments more nuanced in its analytical editing than Birth.

1915 was a fine year for Barker. He turned out the long-praised The Italian (shown in the series), as well as the dynamic Civil War drama The Coward, along with superb William S. Hart westerns like On the Night Stage.

So The Despoiler, another Barker from 1915, did not disappoint. It survives only in a cut-down French print, but it still packs a sensational punch.

The original, according to a contemporary review, involves a border war in which troops invade a small town. The leader of the dark-skinned horde fastens on one beautiful woman, who has taken refuge in a nunnery. She is about to sacrifice herself to save the others, when the colonel learns that she is his own daughter. She is saved, and at the very end the whole thing is shown to have been a dream. The French version Châtiment (“Punishment”), painstakingly restored by the Cinémathèque Française in 2010, was modified to fit propaganda demands of the war period. Here the daughter really gets raped, and she shoots her attacker. The colonel turns his troops loose on the nunnery, but halts them in time when he realizes who the victim is. No dream stuff here.

Barker’s style is fluid, and he builds great suspense when the daughter, barely recovered, prepares to shoot her ravisher with his own pistol. The scene has judicious depth staging, as when the soldier lies drunkenly on the cot but he’s blocked by the woman’s gradual decision to use the weapon. At the proper moment she swivels aside to reveal his head lolling in the background.

The match-on-action when the woman turns and pulls up her sleeve is more perfect than many such cuts in Griffith’s films. She then strides to the background to give us a full view of her target.

A brief shot of the daughter’s attacker is replaced by a 3/4 view of her drawing a bead on him, with Jesus taking her side.

Other countries’ 1915 output wasn’t ignored. We got Denmark’s Revolutionary Wedding, proof that August Blom had not given up the somewhat rigid version of the tableau style he had used in Atlantis (1913). More florid were the Italian offerings. Assunta Spina (lovingly restored by Bologna’s own Cineteca and now available in a DVD), is a classic of the nation’s silent cinema. It was treated to a carbon-arc projection one evening in the courtyard. The less-known but no less flamboyant Il Fuoco (“The Fire”) is a melodrama about a rich woman who destroys a naive, passionate painter.

The two films are famous for showcasing the divas Francesa Bertini and Pina Menicelli respectively. But they’re just as important as powerful illustrations of the variety of 1915 pictorial styles. Assunta Spina is a triumph of tableau staging. By contrast, the opening of Il Fuoco, detailing the first encounter of the owl-woman and the burly artist, is as rigorous a piece of editing that I’ve seen anywhere at the period. Assunta Spina fills the frame with layers of depth (above and first still below). Il Fuoco makes play with bold optical POV, especially when the painter is transfixed by his languid model.

To which one can only say: Zowie.

Bluebirds of happiness

Back in the 1980s I wanted to see some films from Universal’s Bluebird Photoplay series. It had been accepted wisdom that the Bluebirds were among the first American films seen in Japan, and accordingly they had influenced Japanese filmmakers. My searchings led me merely to fragments at the Library of Congress. But today, according the Ritrovato’s indispensable catalog, about thirty complete titles have been found in archives. The most famous, Lois Weber’s Shoes (1916), screened at Bologna in 2011.

The Bluebird franchise was identified with feel-good stories, often rom-coms centered on women and derived from fiction by women. Mariann Lewinsky points out that the unit was a training ground for Rudolph Valentino, Mae Murray, Tod Browning, Rex Ingram, and several other notables. A striking number of Bluebirds were directed by women, in particular Elsie Jane Wilson. About 170 films were produced under the logo, and Hiroshi Komatsu’s catalogue entries confirm that they had a powerful impact on Japanese fans and filmmakers.

Four Bluebird titles, all discovered at the French CNC archive, confirmed the ingratiating charm attributed to the brand. Little Eve Edgarton (1916) centers on a botanist daughter who’s whip-smart in science. Her father tries to marry her off to an older colleague, but she resists. The Love Swindle (1918) is more elaborately plotted. The main couple meet cute during a comic home invasion, in which Diana Rosson proves better at defeating hungry tramps than Dick Webster, who gets conked out trying to protect her. After a date, Dick decides Diana’s too modern and highbrow for him. Diana, undaunted, takes a room in a pension and masquerades as her own impoverished sister, Miranda. Dick naturally falls for Miranda.

Here again, the polish and inventiveness of ‘teens Hollywood comes through. Stylistically, we find nearly everything characteristic of classical presentation: scene analysis, angled shot/reverse shot (though no over-the-shoulders), surprising camera movements, expressive low and high framings. In narrative terms, our heroines conceive goals and pursue them tenaciously. Rosamond in The Dream Lady (1918) even makes a list of her four aims in life. Getting a house is surprisingly easy; marrying a real gentleman takes a little longer.

There are as well ambitious storytelling gambits. At one point in The Dream Lady, an orphan girl imagines that she has a mother and lives in nice surroundings. Director Elsie Jane Wilson cuts freely between the girl’s fantasy and Rosamond looking in on her. One startling cut matches on the girl’s gesture of flouncing her ribbon, taking us between dream and reality. (It’s actually a cheat–wrong arm–but perhaps the change of angle covers the disparity. Sort of like here.)

Then there’s the plot of The Little White Savage (1919). It starts with a circus boss and his sidekick telling customers how they acquired a star attraction, a wild girl purportedly from an island on no maps. The flashback yarn is absurd from the get-go, and it gets wilder as it proceeds, as the heroic sidekick somehow goes from he-man adventurer to pious parson. In a surprisingly salacious passage, Minnie, escaped from the sideshow, hops into the clergyman’s bed. They squeeze and nuzzle unashamedly as nosy townsfolks watch in horror.

It’s all a tall tale, of course, confirmed when the frame story reveals Minnie as simply a cute modern girl. The Confession (Fox, 1918), hinged on a more serious lying flashback and may have supplied the premise for The Little White Savage. Again we find the 1910s as an era of fertile innovation. “Its breezy bold difference makes it worthwhile,” wrote a critic of this Bluebird release. “What Paul Powell and scenarist Waldemar Young have done here is the sort of adventure that makes screen progress.”

A bigger-budget Universal release served as pendant to the Bluebirds. Lois Weber’s Dumb Girl of Portici (1916) was a collaboration with dancer Anna Pavlova. A truncated version had long lain at the British Film Institute, but Geo Willeman and Valerie Cervantes found a 16mm print at the New York Public Library. That enabled them to create a very pretty, nearly-complete version, which now concludes with a lengthy Pavlova dance. The super-production, now running nearly two hours, was based on Daniel Aubert’s 1828 opera and offers some ambitious spectacle.

As a prestige entry with crowd scenes, lavish sets, and one of the stage’s top stars, it’s about as far from the humble Bluebirds as you can get. It’s notably stiffer and less dynamic too; what is it about costume pictures that makes for an academic approach? Still, The Dumb Girl of Portici and the Bluebirds exemplify the ways in which filmmakers of the period laid down many paths of exploration for the future.

The devil you know

I first saw Rapsodia Satanica some years back during a Brussels visit. I liked it fine, but seeing it with tinting and hand-coloring, on the big Comunale screen, with a live orchestra convinced me that it really needs its score. The plot is thin, but with the music throbbing along with its heroine’s seductive pirouettes and mournful drifting, the whole thing makes powerful cinema. It was in fact billed as a “Cinematic-Musical Poem,” suggesting that here lyricism will dominate.

With the score tightly matching fluent acting, I’m reminded of a point Kristin made some years ago. She wrote about the ‘teens as an era in which many directors opened up new domains of cinematic expressivity. Having developed effective methods of storytelling, they began looking for techniques that would deepen the emotional impact of the action. Rapsodia satanica is practically a case study for this tendency.

Countess Alba sells her soul to regain youth. One of her suitors kills himself, the other flees. She winds up alone on her estate. This simple story is elaborated through many techniques of mise-en-scène. There are the dancelike performances; Satan practically coils himself around his victim’s calf. There are the costume changes, as Alba moves from her heavy dowager dress to diaphanous veils in her voluptuous phase, and then, in her solitude, a simple shift. When she thinks the surviving lover is about to return, she wraps herself in the veils she wore before. Even the hand-coloring adds impact; as in the pair of stills below, often Alba’s dress is the only colored mass in the shot.

The hallucinatory images gain both precision and passion from the soaring score. Our heroine sells her soul to Satan in exchange for a return to youth. The moment when she sheds her elderly skin and emerges, like the butterfly we’ll see later, as a ravishing beauty is accompanied by a motif that exfoliates just as lushly. An offscreen pistol shot is prepared by a driving crescendo, but the orchestral outburst is still startling. The countess registers the realization that one lover has killed himself, and diva Lyda Borelli synchronizes her attitudes with that climax: body clenched at first, then sliding toward a more doleful pose.

At forty-two minutes, Rapsodia Satanica is practically, as Gian Luca Farinelli remarked in his introduction, an experimental film. Its unsettling use of multiple mirrors, trapping the heroine in fractured reflections, sets up Charles Foster Kane’s zombie-like passage through his palace. The film’s second part, in which the heroine drifts through landscapes and enormous rooms, looks forward to the American “trance films” of the 1940s and the Cinema of Walkies, from Neorealism and Antonioni to Tarkovsky. In all, the film lets us recognize the persistence of some trends across film history, and appreciate that the 1910s are not as far away as they might seem.

Thanks to Guy Borlée and Cecilia Cenciarelli for help with this entry.

The immense catalogue of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, essential for background to the screenings, can be purchased here. There’s a pdf for reading or downloading here. These folks think of everything.

For contemporary accounts of The Despoiler, see the Lantern pages here and here. The Cinémathèque Française webpage provides a detailed explanation of the restoration. The Photoplay review of The Little White Savage is here.

You can read more about Bluebirds at Adrian Curry’s “Poster of the Week” site on mubi, from which I took the Bluebird logo above. Be sure to scroll down to enjoy the gorgeous designs on display.

For more on why the ‘teens are crucial, see the Vimeo talk, “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.” On continuity editing, you might start here; on tableau staging, here. Kristin’s article is “The International Exploration of Cinematic Expressivity,” in Karel Dibbets and Bert Hogenkamp, eds., Film and the First World War (1995).

Rapsodia Satanica.

Il Cinema Ritrovato: The advantages of leaving home

Kristin here-

David and I are in Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato. Once again there is an overwhelming choice of films on offer, demanding a patient acceptance of the fact that one cannot possibly see anything close to everything one wishes. Careful planning can only do so much.

If there is anything I have learned from the films in the first half of the festival, it is that one should not leave home. In the earliest surviving Mizoguchi Kenji film, The Song of Home (1925), a talented but impoverished young man accepts the idea that staying in his village is best for both himself and Japan.

Nearly thirty years later, Girls in the Orchard (dir. Yamamoto Kajiro, 1953), the heroine must choose between going to Okinawa with her fiancé or marrying a man who can help her maintain her family’s traditional pear farm. Naturally, she makes the right choice.

The heroine of Ousmane Sembène’s first feature, the pioneering Senegalese film La noire de … (aka Black Girl, 1966) leaves her home country for France and the better life she dreams of, only to find herself virtually imprisoned working as a maid in Antibes.

The lesson is clear, and yet those of us who have ventured from around the world to Bologna are all the better for it.

Color blooms in Bologna

Color films have always featured on the program at Bologna, but this year various processes are on display in more threads than usual. While the past three festivals have offered a lengthy retrospective of early Japanese found films, this year’s it’s early Japanese color films. There are vintage Technicolor prints in one series, restored color from the silent era in several threads, and eye-poppers like Cover Girl among the restorations being shown off by various archives and labs.

The first screening on the opening afternoon of June 27 was The Thief of Bagdad–not the Fairbanks silent but the 1940 British version co-directed by Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell, and Tim Whelan. I must have been one of the few in the vast Arlecchino theatre who had never seen it, even in a faded 16mm print. Some were there to recapture the fond memories of their youth.

As a “vintage” print, it had an odd history. This was not a vintage re-release print, as some of us expected. It stemmed from the 1990s chemical restoration which was subsequently digitally scanned. The images looked like the Technicolor films of my youth (not quite the 1940s, but at least the 1950s). It was a relatively early film using the three-strip Tech process, which had really only reached its ideal form in Hollywood as recently as 1939, with The Wizard of Oz and Gone with the Wind.

This print had the eccentricities of the three-strip process. Some shots had poor registration, with red and green rims around the characters, while others were in perfect alignment. The matte lines for the numerous fantastical effects (flying horse, giant jinn, flying carpet) were very obvious, and the color changed suddenly for every dissolve. The print was probably not a bad indication of what audiences would have seen at the time.

The design certainly took advantage of the color process, with numerous false-perspective sets and costumes carefully arranged to show off the range of bright hues that Technicolor could achieve (above).

As for the film itself, it is extremely charming without being one of the masterpieces of the era. It suffers from having a bland pair of actors as Ahmad and the princess who loves him, and Sabu is perhaps a trifle too irrepressible as the titular thief, Abu. Miles Malleson, the comic character actor who co-scripted the film, steals the show as a Sultan so obsessed with elaborate mechanical toys that he trades his daughter to the villainous Jaffar (Conrad Veidt, acting rings around much of the cast) for the flying horse. It was an epic in its day and perhaps helped give rise to the many Technicolor fantasies of the 1950s.

A different sort of range was shown off in a program of silent films restored by the EYE Filmmuseum of the Netherlands. These included hand coloring, as in a 1915 short documentary preserved under its English title, Dutch Types, primarily consisting of shots of villages and schoolchildren.

A 1913 Italian film La falsa strada (dir. Roberto Danesi) was a tinted print. It starts off with a familiar situation of an opera singer giving up the stage to live a quiet life on her rich husband’s country estate. One might expect a young lover to rescue her from her boredom, but instead her very lively show-business friends from the city visit and cause the husband to be jealous of the singer’s apparent preference for their company over his. Unfortunately the final reel was missing.

Even more incomplete was Una notte a Calcutta (dir. Mario Caserini, 1918, right). Only a couple of scenes totaling eleven minutes survive, but they show off the talents of diva Lyda Borelli and suggest that the settings and costumes for this otherwise lost film were impressive.

The emphasis on color promises to continue next year, as with the hints dropped concerning further early Japanese color films to come on a second program.

The auteur of the year

Following a long-established tradition, the festival includes a retrospective of a Hollywood director, Leo McCarey. Having seen quite a few of the films on offer, I haven’t followed this thread faithfully. I fondly remembered Ruggles of Red Gap (1935) from a single 16mm viewing many years ago, though, and decided to watch it. I was glad I did. For a start, it was a mint 35mm print and a joy to watch. Moreover, I had remembered Charles Laughton’s performance as hopelessly mannered and eccentric. This time I caught many of the subtle gestures and glances that he used to convey the thoughts of a character who, at least in the early scenes, speaks little and then only very formally. The supporting cast is ideal for the witty script that condenses the overly long original novel.

McCarey got his start by directing two-reelers with some of the best second-tier slapstick comics of the 1920s, including Charlie Chase, Max Davidson, and Mabel Normand. One program of three showed off each in turn. The Uneasy Three (1925) casts Chase as an aspiring burglar invading a society party with two partners-in-crime sneaking in by impersonating a trio of classical musicians. Don’t Tell Everything (1927) has Max Davidson marrying a wealthy widow, only to have his obnoxious freckled son (Spec O’Donnell, as always) worm his way into the household by disguising himself as a surprisingly convincing maid. Finally, Should Men Walk Home? (1927) teams Creighton Hale and Mabel Normand in another stealing-a-brooch-from-a-society-party plot. Normand gives a late, great performance. (Imdb lists this as her penultimate role.)

The World Cinema Project restores another three

I always try to see the latest films restored by the World Cinema Project, which aims to save important movies made in countries that do not have the archives or resources to protect them. This year the films were La noire de …, Sembène’s first feature, Ahmed El Maanouni’s Moroccan film, Alyam Alyam (aka Oh the Days, 1978), and Lino Broca’s Insiang (the Philippines, 1976).

La noire de … deals with the post-colonialist effects of French rule in Senegal, with the heroine Diouana (below) eager to visit the France of her dreams. Once there, she is never allowed to leave the apartment of the French couple who has employed her; they told her she was to care for their children, but she is relegated to household tasks.

Our friend Peter Rist recalled seeing this film with a color sequence, but this was not included in the restoration. The informative panel introduction to the film, led by Cecilia Cenciarelli of Project, revealed that a sequence showing Diouana’s arrival in Marseilles was shot in color. The idea was to show the heroine’s hopeful view of her new country, contrasting with the black and white of the rest of her film as that hope dissipates. Cenciarelli said that there is no clear evidence that Sembène intended this color scene to be part of the final film. If it survives, it would make a valuable supplement to a future home-video release.

Going from Ruggles of Red Gap to Insiang was an experience in contrasts of the sort one often has here. Insiang is the film’s heroine, a laundress living in a Manila slum. The film was shot in a poverty-stricken area and incorporates many candid shots of children playing in mud and puddles. Much of the action involves shiftless young men who drink and gossip as the women around them do most of the work (above). Against this reality-based milieu, Brocka sets an extremely melodramatic story of Insiang and her mother competing for the affections of the same wastrel. One suspects that Brocka was trying to make his grim film palatable to a broader audience, but the film was a financial failure.

Maanouni took a very different approach for Alyam Alyam. There is a minimal plot about a young peasant earning money to travel to France or the Netherlands for work. This character and his mother and grandfather,  who strenuously object to be his perceived desertion of them, appear at intervals through the film. Most of the scenes, however, are poetic views of village life, evoking both the back-breaking labor of the countryside and the beauty of its traditions.

who strenuously object to be his perceived desertion of them, appear at intervals through the film. Most of the scenes, however, are poetic views of village life, evoking both the back-breaking labor of the countryside and the beauty of its traditions.

In introducing the film, Maanouni said that he wanted to question why Morocco cannot provide the opportunity and incentive to keep young people from leaving. By emphasizing a lyrical depiction of the countryside and the impossibility of earning anything but a subsistence wage, he makes vivid the sad waste of the nation’s potential–a problem that has persisted for decades since the film was made.

The unending march of restoration

The one theme that persists from festival to festival is the thread of re-discovered and restored films. The screenings and, increasingly, the panels and lectures on archival methods, reminds us of how expensive and difficult this process is and how much work goes on each year.

The main film I have seen so far among the restorations is Julien Duvivier’s little-known 1939 film, La fin du jour. (A restoration of his more famous Le belle equipe, 1936, was also shown this year.) It’s the story of a group of actors living in a chateau supported by private charities and dedicated to taking care of aging thespians. They play out their individual dramas against the backdrop of a threatened bankruptcy of the home and a dispersal of its inhabitants to various government hospitals across the country.

There are three primary stories. Cabrissade (Michel Simon) maintains his claim to dramatic fame despite having been only an understudy, and that to a star who never missed a performance. Now entering the home and disturbing its equilibrium is Saint-Clair (Louis Jouvet), an unrepentant seducer and liar. Marny (the less famous but excellent Victor Francen) is a successful actor depressed over his wife’s death, perhaps by suicide, after she ran away with Saint-Clair.

There are numerous small plotlines played out by skilled character actors of the era. The ensemble is interwoven in an impressive example of the “Cinema of Quality,” here practiced by scriptwriter Charles Spaak in collaboration with Duvivier. The tale briefly becomes maudlin toward the end but overall is a touching and often funny depiction of old age among a group particularly reluctant to face that time of life.

In the second half of Il Cinema Ritrovato, I’m concentrating on a small retrospective of Iranian cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, as well as a long-awaited restoration of Satyajit Ray’s Apu Trilogy.

David’s book Figures Traced in Light discusses how The Song of Home displays Mizoguchi’s early mastery of Hollywood-style staging and cutting, before he went on to try considerably different techniques.

Thanks to Manfred Polak for a correction regarding La noire de … His blog entry on the film is here.

La noire de… (Ousmane Sembène, 1966).

Ritrovato 2015: Tributes to a great friend

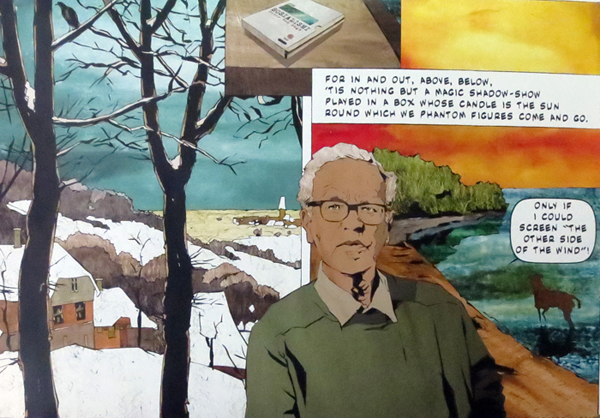

Poster in memoriam Peter von Bagh, Bologna June 2015. Text: “For in and out, above, below,/ ‘Tis nothing but a magic shadow show/ Played in a box whose candle is the sun/ ‘Round which we phantom figures come and go.” “Only if I could screen ‘The Other Side of the Wind.'”

DB here:

The absence of Peter von Bagh, who died last September, was keenly felt at this year’s session of Cinema Ritrovato. It wasn’t just that Peter was no longer there, striding from session to session wearing a big smile and checking the schedule he carried on a small card in his shirt pocket. The loss was made palpable by the reminders of what he had done for world film culture. We know in the abstract that Peter was at once critic, historian, archivist, programmer, festival director, festival founder, and filmmaker. But all over the Cineteca Bologna and environs you find traces of his astonishingly busy life.

Walk into the book room and you’ll see a table groaning with massive volumes. A particularly bulky one is devoted to the Midnight Sun Film Festival he created in Sodankylä, Finland. There’s also a bulky autobiography. On the same table you’ll find DVDs of his films. Above the whole ensemble you’ll find the pensive poster that surmounts today’s entry.

Cinema Ritrovato is the world’s most comprehensive festival of restored and rediscovered movies. Mixing new editions of classics with heaps of films mostly unknown, it’s unique. It’s been called, not only by us, the Cannes of cinephilia. Peter was artistic director of the event during its years of intense expansion. It’s still growing, with bigger crowds and yet another screening venue added (making five in all, not counting the city’s central plaza for the big evening shows). Its size owes something, I think, to Peter’s enormous appetite for cinema–his urge to show as much as possible, to remind us of the majestic (but not solemn) tradition that cinephiles must treasure.

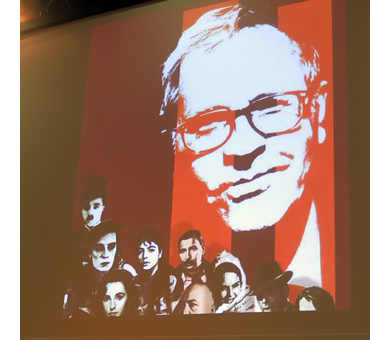

Books and DVD displays go only so far. Despite all these competing attractions, this year’s event has found plenty of occasion to celebrate Peter’s legacy. Threaded through this year’s vast offerings are tributes to the man who, with his colleagues Guy Borlée and Gian Luca Farinelli (with Peter, right, in 2008), has made the whole mad machine go. There are several screenings of his films coming up, and an evening on the Piazza Maggiore will be devoted to his memory.

Books and DVD displays go only so far. Despite all these competing attractions, this year’s event has found plenty of occasion to celebrate Peter’s legacy. Threaded through this year’s vast offerings are tributes to the man who, with his colleagues Guy Borlée and Gian Luca Farinelli (with Peter, right, in 2008), has made the whole mad machine go. There are several screenings of his films coming up, and an evening on the Piazza Maggiore will be devoted to his memory.

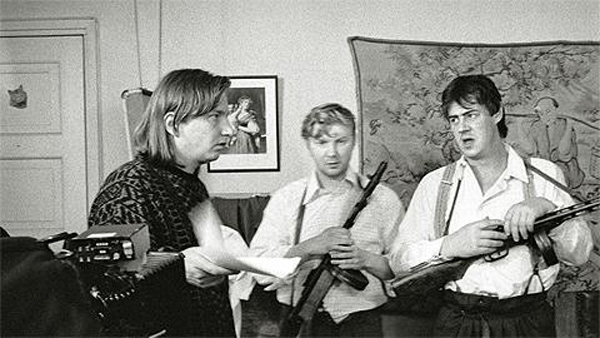

First off yesterday was a screening of Aki Kaurismaki’s TV film Les Mains sales (“Dirty Hands,” orig. Likaiset Kädet) from 1989. Peter had long wanted to screen it at the Ritrovato, and this rare item came forth as Kaurismaki’s homage to Peter. Shot in seven days on 16mm, it fits comfortably into the director’s personal world. Ironic humor mixes with dread, people in desperate situations act with surprising impassivity, and powerful figures bully and deceive pathetic, trusting innocents. A vaguely noir exercise shot in flat, drab color, Les Mains sales shows a political convert eager to become an assassin. At the start, his return from prison is interrupted by a flashback, complete with old-fashioned focus-pull transitions, showing how he got there. The usual Kaurismaki deadpan demeanor undercuts the brooding anxiety of noir, not to mention the source play. “It is Sartre read like a telephone directory,” Peter noted.

The screening was followed by “The 1000 Eyes of Dr. von Bagh.” Here several people shared memories of Peter. Gian Luca’s moving memoir of Peter in the catalogue was echoed in his opening remarks at the round table. Several people shared striking moments of what one called Peter’s “holy enthusiasm.”

The screening was followed by “The 1000 Eyes of Dr. von Bagh.” Here several people shared memories of Peter. Gian Luca’s moving memoir of Peter in the catalogue was echoed in his opening remarks at the round table. Several people shared striking moments of what one called Peter’s “holy enthusiasm.”

*Peter’s sardonic humor: He introduced his Third Reich series last year with the call, “Welcome, Hitler fans!”

*He explained why he brought 70mm equipment to Sodankylä for Play Time: “A film has the right to be screened as it was filmed by its author.”

*All cinephiles feel themselves somewhat out of step with normal living, noted Cecilia Cenciarelli, one of Ritrovato’s programmers. “Peter made this feeling of non-belonging noble.”

*Peter the educator warned how easy it was to show movies that would ingratiate the teacher with the class: “Always go against the tastes of the students.”

*Marianne Lewinsky, stalwart programmer of the Early Cinema events, observed Peter’s pleasure in selecting films: “He knew the joy of being judgmental.”

*Peter in a Russian museum: “Look, this painting is almost as good as a Tashlin movie!”

*Peter’s daughter Anna (above, with Cecilia and Gian Luca) recalls that Peter’s grandson, now talking, wants to fly to meet Peter. “I’d like to do that too.”

Antti Alanen, the preeminent Finnish archivist (and no mean blogger), will supervise the organization and presentation of Peter’s vast posthumous legacy of writings on cinema. During his lifetime Peter already donated his 8000 film books, heavily annotated, to the National Library of Finland, to be housed in a dedicated room in 2016. His archive includes interviews (most running 2-3 hours), and many manuscripts. He took notes during screenings and, unlike most of us who scribble by screenlight, immediately typed them up, embellished with ideas and associations.

Peter never stopped writing (often in bed, Anna says). There are several unpublished works nearly ready for the press, including books on Hitchcock and Welles, a study of comedy, a survey of cinephilia, and most daunting: a twelve-volume history of world cinema, one decade per volume. There are, Antti reports, passages ready to print, passages in a stream-of-consciousness mode, and passages in bullet-point outlines. They will find a home in the Website, “Peter von Bagh: The Memory of Cinema,” expected to go online, with English translations, in 2016.

Antti Alanen’s obituary, a thorough and moving career survey, is must reading. The meticulous David Hudson entry on Fandor gathers many tributes and other material. A book of admiring essays, Citizen Peter, can be ordered here. A brief review of Peter’s memoirs, published in Finnish in the year of his death, is here.

This site’s tribute to Peter is here. You can find references to him in our Bologna blog entries over the years.

28 June 2015, later: Thanks to Antti Alanen for corrections and elaborations of this entry.

Kaurismaki directing Les Mains sales.

Peter von Bagh

Richard Lester and Peter von Bagh, Cinema Ritrovato Bologna, June 2014.

DB here:

Kristin and I have just learned of the death of Peter von Bagh. Critic, historian, programmer, and filmmaker, Peter was an indefatigable lover of cinema whose generosity and kindness was a model for all of us. He made the Midnight Sun Film Festival an obligatory stopping point for the world’s great directors, and as artistic director of the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna he helped push that event to its prominence in world film culture. His personal documentaries, most famously Helsinki Forever (2008), earned their rightful place in festivals.

Mention a film you hadn’t seen, and very likely a week or so later that film–at first in VHS and in later years a DVD–would materialize in your mailbox. I remember Peter asking if I knew Mika Kaurismäki’s films. I confessed ignorance, but when I got home from the trip, there was a parcel of his films waiting for me. Last year at Bologna, I wasn’t able to see Peter’s latest film Socialism; when our paths next crossed, he pressed a copy into my hand.

I will always remember the few days we spent together at a 1997 Archimedia symposium in Brussels. Having meals with him was an education in itself, and his talk–which began with a screening of the first few moments of Barnet’s By the Bluest of Seas–radiated his passion, his deep knowledge, and his vast appreciation for all kinds of cinema. The brunt of his talk was that there was no unimportant film, that every movie deserved our attention. To call him a canon-buster would insult his gentleness, but through his writing, his lectures, and his programming, he drove home the idea that there was always another film out there that would speak to us, if only we would listen.

A warm and easygoing elder brother to us–most likely, to everyone he met–Peter will be remembered wherever film lovers gather.

For a comprehensive account of Peter’s career, see this interview in Cinema Scope 60. Colin Beckett has an informative interview with Peter about the Midnight Sun festival. A book of tribute essays, Citizen Peter, edited by Olaf Möller, is available here. See also Antti Alanen’s Film Diary.

P.S. 22 September 2014, later. David Hudson is compiling tributes to Peter at his invaluable Fandor Keyframe blog.

By the Bluest of Seas (1935).