Archive for the 'Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato' Category

Addio Bologna 2014

Okoto and Sasuke (1935).

DB here:

Some final notes on this year’s Cinema Ritrovato. Kristin has more when I’ve finished.

Poland, very wide

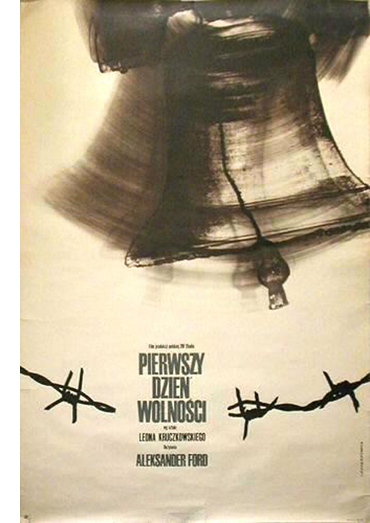

The First Day of Freedom (1964); production still.

Revisiting a couple of the Polish widescreen classics Kristin mentioned earlier, I’d just add that The First Day of Freedom struck me as merging that heaviness often ascribed to Polish cinema with casual shock effects, as much visual as dramatic. It’s not just the opening shot, with the camera descending implacably to reveal layers of activity in a POW camp before settling on barbed wire in the foreground, made as big as the chains on an ocean liner’s anchor. A symmetrical vertical lift ends the film, rising through floors of a nearly destroyed church tower, revealing a half-shattered Madonna and a looming bell, to float back up to the sky.

As in Wajda’s Ashes and Diamonds, gunfire not only cuts you down but sets you on fire. A Nazi dead-ender, holed up in the steeple and dying from his wounds, orders his girlfriend (“Whore!”) to take over his machine-gun nest. Since she’s been raped by wandering refugees early in the film, she has every reason to fire on the Poles, which she does with animal abandon. A Polish bullet cuts short her shooting spree, and then the camera launches on its remorseless movement heavenward. The primal force of this movie, especially the climax, suggests that Alexander Ford and Samuel Fuller have more in common than I’d suspected.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Kristin pointed out the efforts of Lenin in Poland (1965) to humanize the Great Man, and indeed there are many charming scenes showing him sliding down a banister, taking innocent walks with a Polish maiden, and generally being avuncular. But Sergei Yutkevich also doesn’t spare us the enraged Lenin, ranting in his cell when he learns of mistakes in party strategy. We also get a bit of the puritanical leader. He goes to the cinema for reportage on the political-military situation but walks out when a stupid melodrama comes on. To be fair, though, he does stick around to enjoy a comic short, Le cochon danseur (1907), with a lady cavorting with a man-sized pig. But the ex- (or maybe not so ex-) formalist Yutkevich recycles this image in a return to 1920s montage, when the pig shot reappears in a newsreel sequence showing the march to war.

Yutkevich seems to be keeping up with the Young Cinemas of his day. The film is plotted as a series of flashbacks, alternating the present (Lenin in prison) with pieces of the past, sometimes out of chronological order. He imagines himself striding across a battlefield, conveyed by him walking in place against a blatant back-projection. Late in the film, newsreel footage gets stretched and distorted to fill the ‘Scope format, as in Truffaut’s Jules et Jim (1962). The experimentation with the soundtrack seems likewise rather modern. The noises are filtered nearly as strictly as in Miguel Gomes’ Tabu, so that sometimes we hear only Lenin’s footsteps in a city street.

Lenin not only narrates the film but “quotes” the whole dialogue of the scenes; we never hear any voice but his. Reminiscent of passages of The Power and the Glory (1933) and the entirety of Guitry’s Roman d’un Tricheur (1936), this device blankets the movie with Lenin’s thoughts, feelings, and political analyses. It’s scarily evocative of that booming voice-over narrator that Soviet cinema imposed on imported films. Denied subtitles and dubbing, audiences were obliged to listen to an impersonal voice drowning out the actors with its sovereign interpretation of the action. I wouldn’t put it past Yutkevich to be slyly alluding to this Orwellian voice of authority.

1914 fashionistas and 1940s fakers

Maison Fifi (1914).

For sheer dirty fun I have to recommend Maison Fifi by Viggo Larsen, a Danish director working in Germany. Here situation comedy meets notably horizontal sight gags. A young couturier cozies up to the officers stationed in her town, hoping that their wives will buy her wares. Her first encounter takes place outside the officers’ quarters, as each man, from private up to general, spots her and starts to flirt before being ordered aside by a higher-up. Part of the humor comes from the strict adherence to the table of ranks, part from the fact that each dislodged officer enjoys watching his superior get taken down.

Later, on a lark, some officers swipe one of Fifi’s dummies and take it to a tavern. When their wives surprise them there, they stow the mannequin in a distant phone booth. As they expostulate with their wives in the foreground, the dummy sits unmoving in the window of the booth far on frame right. Meanwhile, increasingly annoyed customers line up outside the booth. The dummy is more visible in projection than in my still, but Larsen also obliges with a cut-in.

In a very logical reversal, Fifi is at the climax caught in a boudoir and must pretend to be one of her own mannequins. This affords the officers an excellent pretext to undress her. Today the scene yields a vivid sense of the hooks, buttons, and stays that women, and men, of 1914 had to contend with.

Faked identity was a motif of the festival’s Hitler strand. The Strange Death of Adolf Hitler (1943) centers on a man with a knack for mimicking his Fuhrer and accidentally becomes his double. In a series of twists, both he and others try to kill the original, but confusion ensues and leads to a very downbeat ending.

The same premise gets a different workout in The Magic Face (1951), a film as puzzling as its title. Luther Adler delivers a performance at once peculiar and virtuoso. A stage impersonator’s wife is stolen away from him by Hitler. Escaping from prison, he decides to get his vengeance by posing as a servant and gaining access to the dictator. He kills Hitler and takes over his identity. Thereafter he cunningly fouls up the prosecution of the war by an ill-timed invasion of Russia, etc. His general staff are baffled and even try to kill him, but he represses all resistance.

The weirdness of this speaks for itself. In addition, the film doesn’t explain how Hitler’s new mistress fails to realize that her paramour has been replaced by her husband. Perhaps more striking, we wonder whether the impersonator might have taken a little trouble to alter other Nazi policies, e.g., the Final Solution. No less odd is the frame story, narrated by celebrated war correspondent William L. Shirer. There he maintains that this account was relayed to him by the wayward wife, who survived the fire in Hitler’s bunker. An independent production directed by Frank Tuttle (recently under HUAC pressure for his Communist affiliations), The Magic Face was judged by Variety to provide “a dramatic and suspenseful story which would have had far greater audience impact five or more years ago.”

Talking, in and out of sleep

The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (Hanayome no negoto, 1933); production still.

The Japanese cinema of the 1930s through the 1960s has been one of the very greatest national film traditions. I once characterized it as the Western cinephile’s dream cinema: a relentlessly commercial industry that has given us dozens of indisputable masterworks. Yet it seems that every few years it’s necessary to remind western publics of this nation’s titanic accomplishments. Packages circulated by the Japan Film Library Council in the 1970s have been followed by retrospectives and one-off touring programs at rather long intervals; the Mizoguchi series is a recent example.

Another effort to draw Japanese cinema to the spotlight, “Japan Speaks Out!” has become a high point of Cinema Ritrovato over the last three years. Curators Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström deserve credit for assembling new prints of early talkies, grouped by studio. As in previous years, some of the titles were familiar to specialists, and a few to generalists (Ozu’s The Only Son being this year’s example). But there have been several new discoveries, and the Ritrovato audience has responded enthusiastically. This year the films were screened twice, often to jam-packed halls. The sessions were introduced with brevity and point by Alexander, Johan, and Tochigi Akira of the National Film Center of Tokyo.

This year’s batch focused on the Shochiku studio, more or less the MGM of Japan. Shochiku enjoyed financial stability because of its theatre holdings (both cinemas and live-performance venues) and its address to a modernizing, western-leaning urban audience. Its policies, overseen by Kido Shiro, aimed to provide movies mixing tears and laughter. Kido urged that Shochiku comedy have a melancholy cast, and that Shochiku melodrama indulge in lighter moments. This blend is familiar to us in Ozu’s 1930s works; even as sad a film as The Only Son displays a comic side when the mother falls asleep during a German talkie.

Perhaps the purest example of Kido-ism in this year’s package was one of Shimazu Yasujiro’s best films, Our Neighbor Miss Yae (Tonari no Yae-chan, 1934). Two brothers are introduced practicing baseball, and soon we learn that one has considerable affection for the girl next door. The neighboring families are thrown into quiet turmoil when Yaeko’s sister returns home, having left her husband.

Stylistically, Shimazu is less rigorous than either Ozu or Shimizu Hiroshi, but he is very skilful. Our Neighbor Miss Yae has the real Kido flavor, mixing comedy and drama and throwing in cinephile references that the studio’s young directors enjoyed: one boy is compared to Fredric March, the young people watch a cartoon featuring Betty Boop and Koko the Clown. Just as important, Shimazu enjoys throwing in a stylistic flourish every now and again–a striking, even eccentric shot that arrests our attention. As the four young people are eating in a restaurant, a very straightforward shot of them gives way to a bold composition full of peekaboo apertures. The shot enlivens the fairly routine act of waitresses delivering food; at the end, one pair stands and switches positions.

Not all Shochiku films displayed a mixed tone; we saw some fairly pure comedies and melodramas. Three self-consciously modern films showed an amused, slightly sexy concern with young marriage. Happy Times (Ureshii koro, 1933) by Nomura Hiromasa, begins with a pair of teenage boys practicing pitching and catching to the strains of “There’s No Place Like Home.” Soon they’re spying on newlyweds who are so infatuated with one another that the husband skips work to stay at home and lounge around. He’s mocked by his fellow employees and upbraided by his boss, but his wife is relentless in her sweet-talking ways. The marital bliss is disrupted by an obstreperous visiting uncle, and the couple must turn to one of the man’s old girlfriends, a tough singing teacher, to dislodge him—without sacrificing the inheritance he may leave them. Awkwardly shot and rather too prolonged, the film exemplified how loose-limbed Shochiku comedy could get.

A brace of films by Shochiku stalwart Gosho Heinosuke, The Bride Talks in Her Sleep (1935) and The Groom Talks in His Sleep (Hanamuko no negoto, 1935), showed other newlyweds with comic problems. Again the motif of spying plays a role. (Naughty voyeurism was essential to that strain in popular culture called Ero-guru-nansensu, “erotic-grotesque nonsense.”) Salaryman Komura’s pals have learned that his wife talks in her sleep, and so they drop by to hear for themselves. Unfortunately they drink so much that they fall asleep and miss the big revelation. Plot complications include a burglar, the couple’s decision to sleep elsewhere, and the revelation of what keeps the bride “sleep-talking.”

Only a little less slight is The Groom Talks in His Sleep. Here the title probably gives away too much, because the initial puzzle is why the young wife naps during the day. This scandalous dereliction of housewifely duty leads eventually to a demand for divorce until the cause, the husband’s sleep-talking that keeps her awake all night, is revealed. The family brings in a self-styled hypnotist, played with relish by Ozu regular Saito Tatsuo, to cure the groom.

Gosho is said to be the fastest cutter among classic Japanese directors, but I’m not sure that he goes much beyond what was fairly standard at Shochiku. Most of the studio’s directors working in the contemporary-life genre (gendai-geki) employed what I called in my book on Ozu “piecemeal découpage,” a breakdown of action and dialogue akin to that seen in late US silent films. What Gosho does have in abundance is different camera positions. In The Bride, our introduction to Komura’s drinking buddies takes place at a bar, and I didn’t spot any repeated setups. Throughout the two films, each composition is calibrated to a specific item of information—a line of dialogue, a reaction shot, or a change in the staging. This makes for a tidy visual texture, which is an advantage in the rather loose plotting that’s characteristic of Shochiku comedy (Ozu, always, excepted).

At the other extreme were some very serious drama, such as Mizoguchi’s relatively well-known Poppies (Gubinjinso, 1935) and the more obscure Mizoguchi-supervised Ojo Okichi (1935). There was as well Okoto and Sasuke (Shunkinsho: Okoto to Sasuke, 1935), another Shimazu work. It’s based on a Tanizaki Junichiro tale of male devotion passing into love and masochism. Okoto is blind, but her family can afford to pamper her. She takes up the koto and the family’s young servant Sasuke faithfully escorts her to her music lessons. She often treats him disdainfully, but she insists on his company, and so gossip grows up around them. Sasuke’s loyalty is tested when Okoto is wooed by a vacuous but persistent suitor. Spurned, he arranges an attack on her, which triggers Sasuke’s ultimate sacrifice.

Shimazu treats this story with a calmness that builds up tension between the often wilful Okoto and the simple-hearted Sasuke. The discreet simplicity of the film’s technique, excepting the violent climax, can be seen in an almost throwaway moment. Sasuke as been assigned to tutor two of Okoto’s students, and they laugh at his efforts. As they rise, Shimazu cuts to a new angle, putting them the background and showing Okoto is shown growing anxious in the foreground.

Keeping Sasuke out of focus and far back allows Shimazu to stress a micro-movement in the foreground: Okoto’s shift from sympathy for Sasuke to her usual imperious annoyance. After unfolding her hands, she clenches her right hand and softly strikes it on the edge of the brazier.

As Okoto turns to summon him for a mild dressing-down, still keeping her little fist extended, Sasuke has shifted his position slightly so that he is a more active responder to her.

This sort of directorial discretion, so characteristic of classic Japanese cinema, seems today to come from another world.

Probably the greatest revelation of the Shochiku show was another masterwork by the ever-more-impressive Shimizu Hiroshi. A Woman Crying in Spring (Nakinureta haru no onna yo, 1933), Shimizu’s first sound film, was given its western premier. It was chosen to exemplify his experiments with sound–experiments that induced Ozu to try his own hand at talkies.

Mining work in Hokkaido brings day laborers by ship, along with women who wind up serving them drinks and perhaps something more. Most of the action takes place in a tavern with a bar downstairs, women’s rooms on the next story, and a small upstairs where the mysterious, somewhat cynical Chuko keeps her daughter. Kenji and his boss become rivals for Chuko, and a young woman drawn into prostitution further complicates the situation.

After only a single viewing, I’m pressed to say much more than noting that Shimizu sacrifices some of his geometrical precision (discussed here) to a more naturalistic treatment of the bar’s space and more experiments with chiaroscuro lighting. A somewhat flamboyant scene, in which our view of a fistfight is mostly blocked by a high wall, shows how Shimazu was trying to let sound do duty for the image. The title has multiple implications: the woman we see crying at the outset is Fuji, the girl initiated into the trade; but at the end, Chuko is weeping. Moreover, as Alexander Jacoby pointed out, the scenes we see are all set in winter, although the ending suggests that the couple that is created will find spring elsewhere. Long unavailable in its Japanese VHS edition, A Woman Crying in Spring is ripe for Western distribution.

Last notes from Kristin

Despite my commitment to the Polish, Indian, and Japanese threads, I was able to fit in a film or selection of shorts now and then.

On the afternoon of the opening day, the first “Cento Anni Fa” program for 1914 included a couple of interesting items. One was La guerre du feu, a French film directed by George Deonola. It dealt with a tribe of fur-clad cavemen who have captured fire but lack the knowledge to create it themselves. Thus they must tend their fire constantly and protect it from a rival tribe. In the course of the action the hero learns the secret to using tinder and flint to generate a blaze. This, it has to be said, was more interesting as an historical curiosity than as entertainment.

Not so the final film of this group, Amor di Regina (Guido Volante, 1913). Its unusual story dealt with a queen of an unnamed country who is having a secret affair with a young soldier. When the latter gets wind of a rebellious group’s plans to assassinate the king, the hero and the queen manage to spirit him out of the palace and away to exile. It struck me that in a more conventional film, the lovers would use the assassination of the king to allow them to marry. Instead they take care of the king in exile and watch for a chance to reinstate him.

Stylistically there were some impressive shots. In one, we see a close-up of the back of the hero’s head, looking out from a terrace at a group of conspirators in the distance sneaking toward the palace, and the camera racks focus from him to them–for 1913, a highly unusual way to handle a very deep composition. If anyone is contemplating a DVD/BD release of some Italian short features of this era, Amor di Regina would be a good choice.

Another 1914 program included the lovely La fille de Delft, which, along with Maudite soit la guerre (which was shown at one of the Piazza Maggiore screenings), is one of Alfred Machin’s best-known films. Its plot concerns a little country boy and girl who are dear friends; a variety-theater owner sees them dancing at a country celebration and takes the girl off to the city to become a star. Seeing it again, I was struck at how marvelously natural the performances of the two child actors (above) was, something that goes a long way to making this film so very affecting.

Despite the fact that all of Tati’s early short films are on the new French boxed Blu-ray set, I decided to see the Tati program on the big screen. Seen again, Gai dimanche (1935) seemed a bit labored in its humor, dealing with two layabouts who hire an old car and persuade several people to purchase day trips to the country. The situation seems more the sort of thing that René Clair could have made work, but director Jacques Berr makes it somewhat leaden.

Soigne ton gauche centers on a gawky farmhand who is mistaken for a boxer by a promoter and ends up in a practice ring with a tough opponent. Tati creates a very Keatonesque situation as the naive young man finds a book on boxing on his stool and proceeds to consult it at intervals (below). As he assumes classic boxing poses, the experienced boxer uses brute force to knock him silly.

The opening and closing of Soigne ton gauche contains a comic, bicycle-riding postman, and clearly Tati recognized the comic potential of the character. In his first directorial effort, L’école des facteurs (School for Postmen, 1946), Tati himself played the postman François, who tries to please his teacher by finding ways to deliver the mail more swiftly. The idea proved so fruitful that the film was remade as Tati’s first feature, Jour de fête. The bouncy music and many of the gags were retained, and the longer film’s success established Tati as a major director and star.

To all our friends and the coordinators of Cinema Ritrovato: Thanks for another wonderful year!

You can watch The Eye’s tinted copy of Maison Fifi here.

Miriam Silverberg’s Erotic Grotesque Nonsense offers a thorough discussion of Japanese popular culture of the 1930s. For more on Kido Shiro’s influence on Kamata cinema, see Mark Schilling’s Kindle book Shiro Kido: Cinema Shogun. I discuss trends in 1930s Japanese film style in Chapters 12 and 13 of Poetics of Cinema. For more on the restoration of Machin’s films, see our entry here.

Soigne ton gauche (1936).

Il Cinema Ritrovato: Strands from the 1950s and 1960s

Faraon (1966).

Kristin here:

David has already posted an early report on his first full day at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna. It conveys something of the overwhelming abundance of offerings at this year’s festival. Writing another entry during the festival itself proved impossible, given our packed schedules, but now we have time to catch our breath and reflect on what we were able to see.

As with the 2013 festival, I decided that the only way to navigate the many simultaneous screenings was to pick out some major threads and stick with them. I chose the retrospective of Polish widescreen films of the 1960s, that of Indian classics from the 1950s, and the third season of early Japanese talkies. Miraculously, none of these conflicted with each other, the Polish films being on mainly in the mornings, the Japanese ones directly after the lunch break, and the Indian films starting late in the afternoon.

Again, it was possible to fit in a few films from the other programs on offer, including a series of Germaine Dulac’s films, restorations of East of Eden and Rebel without a Cause, a selection of Riccardo Freda’s work, Italian contributions lifted from various anthology films of the 1950s and 1960s, a celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Österreichisches Filmmuseum, and many Chaplin shorts (the festival was preceded by a brief conference on Chaplin).

The annual Cento Anni Fa program, showing films from 100 years ago, has changed, in part to accommodate the fact that the transition to feature films was well underway. The series programer, Mariann Lewinsky, has also branched out. Having discovered many unknown or little-known early silents during her annual quests, she has included other brief thematic programs, such as fashion in early films. In addition, there was a lengthier selection of early films dealing with war, given that we are now in the centenary of World War I.

A Journey from Pole to Pole

The Saragossa Manuscript (1965).

To me the biggest revelation of the festival was the program of Polish anamorphic widescreen films. Representing most of the major Polish directors working in widescreen in the 1960s, these were shown in 35mm, mostly in original release prints from the period, on the big screen of the Cinema Arlecchino theatre. Despite occasional wear in the prints, they looked great.

The series kicked off with Aleksander Ford’s little-known The First Day of Freedom (Perwszy dzień wolności, 1964). Like many of the films in the program, it dealt with World War II. Polish soldiers, escaped from a POW camp, enter a nearly deserted German town. They disagree on whether to help protect the civilians they encounter or participate in the general rape and pillage in the wake of the Nazi retreat. It’s a grim and realistic look at a topic seldom tackled in films about the war.

Also on the program was Andrej Munk’s Passenger (Paseżerka, 1963), left unfinished when the director was killed in a car accident. His colleagues eventually decided to assemble the film without additional footage, drawing upon still photos for some scenes and an effective voiceover filling in the action. The effort works well, and the result is a powerful examination of a Nazi death camp. The story does not concentrate on Jews but on political prisoners, implicitly communists and other rebels. The result is the sort of disguised political comment on Poland’s contemporary situation that is common in these films.

Early on, a middle-aged woman aboard a ship tells her companion about her life in as an official in the camp–a story that is contradicted when the actual scenes of her activities at the camp play out. The woman singles out a female prisoner, Marta, and rationalizes her irrational mixture of rewards and punishments as efforts to save her from the other prisoners’ fates. With its depictions of cat-and-mouse games between prisoners and captors and its references to mysterious sadistic rituals played out by the guards, the film is a powerful meditation on the camps, worthy, as Peter von Bagh’s program notes say, to sit alongside Resnais’s documentary, Night and Fog.

Among the unexpected delights of the series was Lenin in Poland (Lenin w Polsce, 1966) by Sergei Yutkevich (or, as he is credited here, Jutkevič). Yutkevich began as a member of the Soviet Montage movement, contributing a little-known, late feature, Golden Mountains (1932). Working in Poland, he managed the formidable task of humanizing Lenin in unorthodox ways. Yutkevich concentrates on the leader’s Polish exile on the eve of World War I. Framed by Lenin’s brief imprisonment on charges of espionage, the film proceeds through flashbacks to his recent activities. As portrayed by Maksim Strauch, whose resemblance to the revolutionary leader gave him a long career in numerous films, Lenin is humorous, kind, thoughtful, and a likeable protagonist. Yutkevich includes touches from the Montage movement, with some passages of quick cutting and frequent heroic framings of the protagonist.

With my interest in ancient Egypt, I was particularly curious about Faraon (Pharaoh, Jerzy Kawalerowicz, 1966). The director tackles the unusual and obscure topic of the end of the 20th Dynasty, which led to the end of the golden age of the New Kingdom and the instability of the Third Intermediate Period. The film’s drama comes from the real-life conflict between the impoverished, weakened monarch and the wealthy, powerful priests of Amun in Thebes. I’m not sure how well an audience not familiar with this era would follow the plot, even simplified as it is. There are some remarkable crowd scenes, as at the top of this entry, when Herhor, the chief of the priests, rallies the crowd against the pharaoh. Still, I did not find the story engaging. Presumably it was a covert commentary on politics in Poland at the time.

The best-known of Polish directors, Andrzej Wajda, was represented by two films. One was the earliest film shown in the series, Samson, from 1961. It concerns a young Jewish man who is lured to escape from the Warsaw Ghetto and spends most of the film dodging the police by moving from one temporary haven to another. Wajda creates a compelling depiction of the ghetto early on, and I wished he had stayed in that environment longer.

My favorite film of the festival was Wajda’s little-known Ashes (Popioły [not to be confused with Ashes and Diamonds], 1965), an epic tale of the Napoleonic wars and Poland’s unwise participation in them on the side of the French. The protagonist, Rafal Olbromski, is a naive young nobleman from a rural area, a Candide-like figure whom we follow as he leaves his estate to go to war and moves from locale to locale, manipulated by more sophisticated characters. The result is a dizzying succession of battle scenes, largely without any context being established, punctuated by visits to the estates of those who are backing the Polish participation in Napoleon’s conquests. Wajda seemed to have had nearly limitless funds for the film, and the battle scenes are monumental.

Far less obscure is Wojciech Has’s The Saragossa Manuscript (Rękopis znaleziony a Saragossie, 1965), a cult item among film buffs and reputedly one of Luis Buñuel’s favorite films. It’s a complex, surreal tale of a wandering soldier of the 18th Century who passes the gibbets of two executed men in a bleak Spanish landscape and enters a mysterious inn. There he encounters a large bound manuscript that leads him into a world of shifting fantasy and tales within tales within tales. Has’s was certainly one of the most humorous and entertaining films in the series.

The latest film in the program, Adventure with a Song (Przygoda z piosenka, Stanisław Bareja, 1969), was radically different from the others and provided a look at popular Polish cinema of the 1960s. Bareja was a successful director of comedies and musicals. This one follows a young singer who wins a local singing contest with the improbably named “The Donkey Had Two Troughs,” and decides to head for a professional career in Paris. The filmmakers’ attempts to replicate the Mod styles and garish colors of the 1960s in the West yield an incongruous and awkward but fascinating film .

The one disadvantage of seeing these vintage distribution prints (mostly with English subtitles) was that some were abridged versions, occasionally radically so. Samson, The First Days of Freedom, Adventure with a Song, and, inevitably Passenger were shown complete. Judging by imdb’s timings, however, others were missing significant amounts footage: Ashes (shown at 169′, originally 234′), The Saragossa Manuscript (155′ vs. 175′), Pharaoh (149′ vs. 180′).

Recently there seems to be a revival of interest in Polish classic films. Martin Scorsese has curated a large program that is currently touring the US with digital copies of restored films. (For links to numerous articles on the series and the restorations, see its Facebook page.) I hope that some enterprising company will issue the complete versions of these Polish classics in their proper widescreen ratios. Ashes is a particularly good candidate for such treatment. Having sat through it once at nearly three hours, I would happily watch it at closer to four.

Worthy of restoration

There’s a growing interest in recent Indian films, at least in the USA. Our biggest local multiplex nearly always devotes  one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

one screen to a Bollywood musical, and sometimes two. Yet few know the great classics of the early post-colonial period in India, following World War II and independence from Great Britain, which are seldom seen, even by film historians.

One reason is because many of these classics still await restoration. While most programs shown in Bologna consist of newly restored prints, this series was titled “The Golden 50s: India’s Endangered Classics.” Each of the features was accompanied by an episode of “Indian News Review,” a newsreel that for years was shown in film programs across India. Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, founder of the Film Heritage Foundation, curated the series and introduced each film, emphasizing that even the eight classics selected for the program are in danger if not properly restored soon.

The need was evident from the prints. Some were old distribution prints, but three of the films could only be shown on Blu-ray. Even under these conditions, however, the range and quality of Indian cinema of the 1950s was apparent.

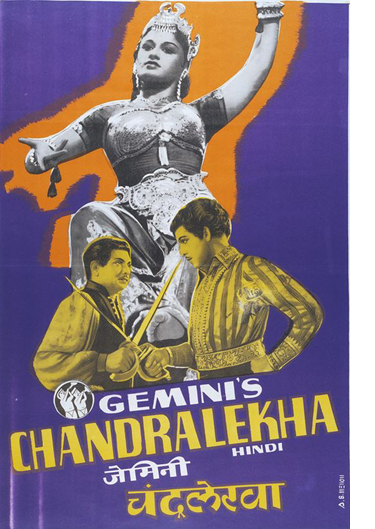

The earliest film in the series, Chandralekha (S. S. Vasan), was made a little before that decade, in 1948. Its presence stems from its crucial importance in Indian film history. It was the first big, successful Indian musical of the post-colonial era and set the pattern for many of the country’s subsequent films. The story has a fairy-tale setting, with a good and an evil brother fighting over the throne of their father’s kingdom and also for the hand of the beautiful Chandralekha. The rambling plot includes lots of songs and dance numbers, leading up to the climactic, legendary Drum Dance (below right), with dozens of dancers atop rows of enormous drums. It lives up to expectations. (For more on Chandralekha, see fellow Ritrovato fan Antii Alanen’s epic blog post.)

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

David has already described seeing the sole Raj Kapoor film in the series, the very popular Awara. Bimal Roy’s Two Acres of Land (Do Bigha Zameen, 1953) is a very different sort of film. Quite consciously inspired by Bicycle Thieves, Roy’s film eschews the standard musical numbers and deals with a poor farmer destined to lose his small farm unless he can pay off a large debt. His journey to Kolkata, with his son trailing after, throws obstacle after obstacle in his path, and Roy avoids a happy ending. The film was shot on the streets of Kolkata, which Dungarpur assured us have not changed much since this record of them.

One of the great Indian directors, Ritwik Ghatak, has become somewhat familiar in the West, thanks in part to the British Film Institute’s issuing two of his masterpieces on DVD: A River Called Titas and The Cloud-Capped Star. The series at Bologna included Ghatak’s first feature, Ajantrik (1957). It is set among the poverty-stricken Oraons, an isolated population in Central India, and follows a man who is devoted to his dilapidated taxi, which he manages to hold together well enough to supply him a marginal living. He has come to think of the car as a human companion. (Accordingly, the title means, roughly, “not mechanical,” although for western distribution it was given the unenticing title Pathetic Fallacy.) Though Ajantrik is not a major film on the level of the others in the program, it was good to have the rare opportunity to see Ghatak’s first film.

The star of the series was undoubtedly an equally respected director, Guru Dutt. Two of his films, in both of which he also starred, were shown. One of his finest films, Pyaasa (The Thirsty One, 1957), was perhaps the best film of the program. Dutt is considered to have integrated the conventional song episodes of Indian cinema into his films more skillfully and in more original ways than other directors.

Dutt plays a great but unappreciated poet whose work is ignored by the intelligentsia of his own class. He wanders in despair among the poor and outcast, for whom he has great sympathy. In one haunting scene, he walks through a brothel district and sings of his despair for humanity (below). Early in the film he meets a prostitute who appreciates his poetry and falls in love with him. Only after the poet’s apparent death does his work become widely loved among the the common people, but his reputation is exploited by his hypocritical family and publisher.

Dutt’s Kaagaz Ke Phool (Paper Flowers, 1959), was also shown. Again Dutt plays an unappreciated artist. A film director divorces his wife and becomes the target of gossip when he casts a beautiful young actress in his next movie. His personal misery affects his ability to direct, and after a slow slide into alcoholism, he loses his job. The plot allows Dutt to express self-pity more obviously than in Pyaasa, and the comic scenes with his ex-wife’s family strike an odd tone in such a grim story. Kaagaz Ke Phool was not a success, and Dutt gave up filmmaking altogether, dying of an overdose of sleeping pills five years later. As Dungparapur pointed out, he was one of several important Indian filmmakers who died rather young, which makes the rescue of these classics all the more essential.

Pyaasa (1957).

12 hours, Ritrovato time

DB here:

Reporting on the magnificent Cinema Ritrovato festival at Bologna has become a tradition with us, but it’s become harder to find time during the event to write an entry. The program has swollen to 600 titles over eight days, and attendance has shot up as well; the figure we heard was over 2000 souls. The organizers–Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée–have responded to requests for more repetition of titles by slotting shows in the evening, some starting as late as 9:45. (You can scan the daily program here.) There are as well panel discussions, meetings with authors, and some unique events, such as carbon-arc outdoor shows, the traditional screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, and Peter Kubelka’s massive and mysterious Monument Film. Add in time to browse the vast book and DVD sales tables, and the need to socialize with old friends.

In all, Ritrovato is becoming the Cannes of classic cinema: diverse, turbulent, and overwhelming. How best to give you a sense of the tidal-wave energy of the event? I’ve decided to take off one morning and write up just one day, Monday 29 June. I don’t know when Kristin and I will find time to write another entry, for reasons you will discover.

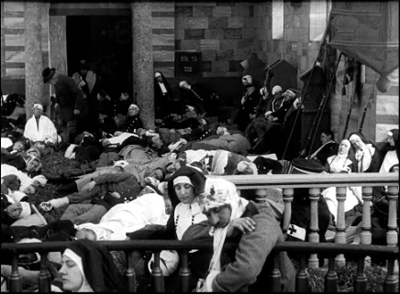

9:00 AM: Ned Med Vaabnene! (Lay Down Your Arms!, 1914) was a big Danish production, based on a popular anti-war novel by the German Bertha von Suttner. It’s a remnant of the days when the rich went to war along with the common folk. (Sounds quaint in today’s America, where the elite have other priorities.) The Nordisk studio specialized in “nobility films,” melodramas that show the upper class brought low by circumstances; Dreyer’s The President (1919) is another example. The film, directed by Holger-Madsen, shows a family devastated by war and its aftermath. It’s shot in tableau style, with the restrained acting and sumptuous, light-filled sets characteristic of Nordisk. The combat scenes are remarkably forceful, but the most harrowing scene, for me, is the shot showing a battlefront hospital, with exhausted nuns and wounded men strewn around the shot–a tangle of limbs and heads.

Premiered soon after the Great War broke out, Lay Down Your Arms! anticipates Nordisk’s wartime policy. Denmark was a neutral country, and the Danish industry depended on both the German and the American markets. As a result, most of the films studiously avoided taking sides. After the war, with the revival of the German industry and the circulation of American films in Europe, Nordisk lost its powerful position in the international market.

The entire film is available for viewing online at the Danish Film Institute site.

Programmer Mariann Lewinsky, in charge of the “100 Years Ago” thread, wisely included other pacifist films from the mid-teens. One of the high points was the evening screening, on the Piazza Maggiore, of the fine Belgian film Maudite soit la guerre (1914), in the hand-colored version I discussed some years back. Not by accident, I suspect, Lay Down Your Arms! featured several Lewinsky dogs.

10:30 AM: Werner Hochbaum was an unknown name to me, but after seeing Morgen beginnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow, 1933), I realized that was my loss. This story of a cafe violinist released from prison is a sort of anthology of 1920s International Style devices: canted angles, rapid montages, City Symphony passages, flamboyant camera movements, multiple-image superimpositions, and huge close-ups of faces, hands, and objects. The work on sound is no less ambitious, with voice-overs, sound motifs (a carousel, a canary’s call-and-response to a chiming doorbell), offscreen dialogue, and harsh auditory montages of traffic and city life. Everything from Impressionist subjective-focus point-of-view to Expressionist shadow work comes into play.

The plot is gripping throughout. At first we don’t know why the violinist was imprisoned, and we learn about the case first from his gossiping neighbors (excellent run of whispers during fast-cut close-ups of housewives), then from his own flashbacks, which build up to a revelation of the murder he committed. Threaded with all this is another uncertainty: Has his wife begun a love affair while he was in jail? Giving us only glimpses of her life as a cafe waitress, Hochbaum leads us to suspect that he will come home to more misery–and perhaps another temptation to murder.

Along with all this were arresting side scenes of cafe life, like a fat woman ordering up a gigolo to dance with her, reminiscent of Georg Grosz and the New Objectivity’s cynical portrait of daily desperation. It’s a lot to pack into 73 minutes, but Morgen beginnt das Leben succeeds smoothly and made me want more. Alex Horwath‘s introduction confirmed that this is a director we should know better. We can hope that a DVD edition is coming soon.

Noon: A packed house for the panel of three American studio archivists: Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox, Grover Crisp of Sony, and Ned Price of Warners. Too many ideas to summarize here, but one that emerged: Digital tools are great for restoration, not so reliable for preservation.

Ned (left) emphasized that now scanners are very sensitive to the oldest negatives, with their shrinkage and warpage. But Ned pointed out that today’s monitors don’t often render the full color scale needed to respect film’s tonal range, so that weak monitors mean that we are “working blind” and may “bake in” flaws that will be evident when display devices improve. Likewise, low bit-depths (often only 10-bit) in outputting to film for preservation can cause problems later. Grain reduction is another big problem. Grover (center) added: “When you do anything to grain, you’re denaturing the film.”

On the restoration front, Schawn showed clips from the 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth, first from a beautiful photochemical restoration of twelve years ago, then from a recent digital one. To my eye, the warm skin tones of the 35mm image were more attractive than the almost porcelain surfaces of the digital version, but the latter was sharper and contained a healthy amount of grain. Grover screened A/B comparisons of the main titles of Only Angels Have Wings and Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa (Sandra ), both of which showed how handily digital restoration creates a rock-stable image, without the jitter and weave unavoidable with a strip of film.

All the panelists agreed that digital restorations are rapidly improving; ones finished only a few years ago could now be done better. A major problem coming up is that younger restoration workers know the digital tools better than the look and feel of photochemical, particularly the surface of older films. Grover recalled that one eager techie added flicker to a Capra silent because he thought that was how old movies looked.

1:15 PM: Hurried lunch with Schawn. Main topic: The Grand Budapest Hotel, but also the vagaries of the DVD and Blu-Ray market.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

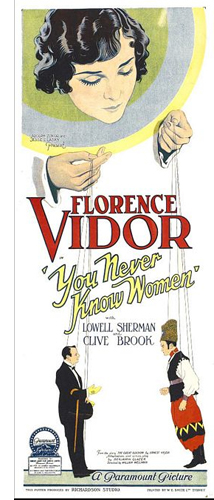

You Never Know Women (1926) is an exercise in good old classical storytelling. The plot presents Vera (Florence Vidor), star of a troupe of Russian entertainers, momentarily entranced by a no-good millionaire who wants to seduce her. The magician of the troupe, Norodin (Clive Brook) loves her, but she’s unaware of her feelings for him until the Lothario’s true nature is exposed. El Brendel adds spice as a clown devoted to his pet duck.

Variety‘s review was ecstatic, claiming that “Wellman at the megaphone lifts himself into the ranks of select directors with by his handling of this story, for his direction is never obvious or old-fashioned.” I’ll say. Filled with running gags, seesawing conflicts, and motifs (Ivan’s skill at knife-throwing, the expletive, “Ridiculous!”), You Never Know Women has a headlong pace. With nearly a thousand shots in 70 minutes, it relies on glances, gestures, and reactions to channel the dramatic flow. It needs only three expository titles, letting its 100 or so dialogue titles pinpoint key emotional transitions. In anticipating the sound cinema that was just around the corner, You Never Know Women resembles the more famous Beggars of Life (1928, given pride of place at Ritrovato), which as I recall uses dialogue titles exclusively.

The Man I Love (1929) tells the familiar story of a prizefighter who, as he rises in the game, leaves his loyal woman behind. As an early sound film, it relies on multiple-camera shooting for extended dialogue scenes, but Wellman enlivens the staging with unusual angles, including a view of a quarrel seen through a window in a dressing-room door. The Man I Love boasts the sort of ambitious, somewhat bumpy tracking shots we sometimes find in early talkies. One swaggering camera movement takes us from the locker room into an arena, down the aisle, past the ring, and to Dum Dum’s anxious wife in the crowd, a sketchy prefiguration of the celebrated Steadicam movement in Raging Bull. The fight scenes, not requiring sync sound, are shot with brio, while the dialogue scenes are extremely well-miked, allowing for fairly fast line readings and varied volume and emphasis in the voices.

Gina Teraroli and David Phelps, along with other colleagues, have assembled a wide-ranging dossier on Wellman’s work that serves as a fine complement to the Ritrovato thread.

5-something PM: One of the things in the first edition of our Film History: An Introduction that made me proud was the inclusion of sections on Indian cinema, a subject usually ignored in textbook surveys. I remember in the late 1980s and early 1990s watching the 1950s-1960s classics of Hindi filmmaking with a sense of discovery: How could we not have known this invigorating tradition? It was therefore with a sense of homecoming that I visited Raj Kapoor’s Awara (“The Vagabond,” 1951), in a pretty sepia-tinted print.

The young ne’er-do-well Raj (no last name, and this is important) is on trial for attacking a judge in his home. A female lawyer, Rita, takes up his defense and urges the judge, on the witness stand, to tell why he expelled his wife from his home many years ago. The wife had been kidnapped by the gangster Jagga, and the judge assumed that the child she was now expecting was Jagga’s. Before the courtroom, Rita recounts up the story of how young Raj, actually the judge’s legitimate son, took up a life of crime. To add spice, Rita is the judge’s ward and Raj’s lover.

No coincidence, no story, they say, and Awara offers plenty of timely misunderstandings and improbably neat encounters. No matter. We’re told that TV narrative, by stretching its tale over several hours, can introduce novelistic breadth, but so can Indian classics of the 1950s. This one takes us across twenty-four years and as many ups and downs as a mini-series might offer. Not to mention Kapoor’s vigorous visual style, with huge sets, vivacious fantasy sequences, and traces of 1940s Hollywood hysteria (chiaroscuro, fluid track-ins to overwrought faces, even thunder and lightning in the distance). Here Raj, about to stab the judge, shatters the childhood picture of Rita; her simple gaze checks his moment of revenge.

Then there are the songs, lusciously sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Mukesh. Of course the sprightly “Awara Hoon” is the official classic and Kapoor’s signature tune, but this time around my favorite was the duet, “I wish the moon…,” with Rita asking the moon to look away and Raj asking it to turn to him. With its glamorized social realism, its tale of a good boy gone wrong, unjustly punished, and eventually redeemed, and its primal themes of mothers, fathers, and sons, Awara is a milestone in the world’s popular cinema…. and just one of several Indian classics in this year’s Ritrovato.

That was one day. Now I’m off to…what? Polish films in widescreen? The Riccardo Freda retrospective? The rare Ojo Okichi? Or maybe the restored Oklahoma!? In any case, this afternoon an incontro on Nicola Mazzanti‘s book 75000 films, and tonight Guru Dutt’s glorious Pyaasa.

I tell you, it’s hard to keep up, running on Ritrovato time.

Nargis and Raj Kapoor sing to the moon in Awara.

Il Cinema Ritrovato, number 9 and counting

Kristin here:

For a second year running I unexpectedly ended up attending Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna alone. (For the 2012 report, see here.) Last year David’s back went out shortly before we were due to leave. This year an exceptionally long stretch of days with heavy thunderstorms resulted in flooding in our basement (where many of our books reside). I had already been in London for nearly three weeks and was planning to meet David in Bologna. Instead, he valiantly stayed home to deal with the unwanted water, and I went on to the expanding smorgasbord of films presented by the festival.

The programmers are limited to their existing venues: the relatively small Mastroianni and Scorsese auditoriums in the Cineteca’s building, the larger Arlecchino and Jolly commercial cinemas, and the vast space of the Piazza Maggiore for the nightly open-air screenings starting at 10 pm. This year for the first time, to accommodate the many films, post-dinner screenings, starting at 9:30, 9:45, or 10 pm, were scheduled in the Scorsese and Mastroianni.

Faced with so many options, one could only focus on a few of the bounteous threads of programming. I opted to see as many of the early Japanese sound films as possible, the early (pre-mid-1960s) Chris Marker works, and the annual Cento Anni Fa series, this year presenting a sampling of films from 1913, the year when worldwide the cinema seemed to take an extraordinary leap forward in complexity and inventiveness. Whenever there was a gap, I could fit in items from the other threads: European widescreen movies; cinema of the 1930s that presaged the coming war; a retrospective of the work of Soviet director Olga Preobrezhenskaja, another devoted to Vittorio de Sica, primarily as an actor, more Chaplin restorations from the Cineteca’s ongoing project, the newly restored Hitchcock silents, and of course various other newly restored films. A tradition of highlighting the work of a Hollywood director has become a centerpiece of Il Cinema Ritrovato, with the subject this year being Allan Dwan.

Japanese Talkies, Part 2

Last year I caught only a few of the films in the retrospective of early Japanese sound films. I regretted not being able to see more, but the Ivan Pyriev and Jean Grémillon threads lured me away. This year the rival was Chris Marker, but I determined that by careful planning, I could fit almost everything in both retrospectives into my schedule. These became my top priorities.

The Japanese series is ongoing and organized not by auteurs but by film companies. The programmers were again Alexander Jacoby and Johan Nordström, whose encyclopedic knowledge of the history of Japanese studios of the 1930s made  for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

for fascinating introductions. This year it was PCL and the very obscure company JO, both of which made American-style musicals in the early and mid-1930s. These were not the best films in the season, but they were highly entertaining. This series also had the advantage of being presented entirely in 35mm and with English subtitles devised years ago for traveling retrospectives.

I had seen only one of the films in the series, Mikio Naruse’s 1935 masterpiece, Wife, Be like a Rose. I didn’t remember much about it, except that it was marvelous, and it proved so on second viewing. Naruse often has been compared with Ozu, both during his active career and since. Overall, he seems to me not as great a filmmaker, but Wife, Be like a Rose must be among his best films and would undoubtedly rank alongside some of Ozu’s work of this period. A moga (modern girl) is upset that her father has deserted his family in Tokyo and established another family in the countryside. Determined to drag him back to his familial responsibilities, the daughter confronts the possibility that he was right in leaving her mother. The film is shot in a somewhat Ozu-like style, with low camera heights and across-the-line shot/reverse shots. Still, there is no slavish imitation (the climax is filled with camera movements), and Naruse’s film is both moving and stylistically engaging.

Naruse was the only director with two films in the retrospective. His Five Men in the Circus, also released in 1935, was a less ambitious work than Wife, Be like a Rose, but it was an entertaining story of musicians on the road earning a living during the Depression, encountering disappointments in work and love.

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

Naruse has already gained a modern reputation in the West, but for some the discovery of the season was Sotoji Kimura, whose Ino and Mon was well received. As with so many of this thread’s films, its subject was a modern girl struggling with tradition. Mon, who has become pregnant and doesn’t want to marry her child’s father, returns to her country home and faces sullen opposition from her much beloved but fiercely traditional brother Ino. Aside from its realistic depiction of the countryside, the film is notable for its Soviet-style scenes of work on a nearby construction project supervised by the siblings’ father (left).

The Japanese musicals were all charming films. Romantic and Crazy (1934) starred the popular comic performer Kenichi Enomoto, better known as Enoken. (In the West, he is most familiar from his comic role in Akira Kurosawa’s third feature, The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail [1945].) Romantic and Crazy is basically a college musical imitating the early 1930s films of Eddie Cantor–and at  moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

moments I wished I were watching an Eddie Cantor musical. The other two musicals–Tipsy Life (Sotoji Kimura, 1933) and Chorus of One Million Voices (Atsuo Tomioka, 1935)–were quite entertaining. Clearly the filmmakers felt no compunction about stealing recent American songs and setting the tunes to new Japanese lyrics. The most popular seemed to be “Yes, Yes, My Honey said Yes, Yes!” as sung by Cantor in the 1931 musical Palmy Days; the tune was heard in at least two of the films.

Another notable film was Sadao Yamanaka’s Kôchiyama Sôshun (1936), one of his three surviving feature films. (These and fragments of others are available on a new set from Eureka! in its “Masters of Cinema” series.) It’s a strange film, partly comic but mostly a crime story. An attractive woman, played by a very young Setsuko Hara, keeps a shop owned by a local gangster, and tries to prevent her thuggish younger brother from becoming a criminal. The title character, Kôchiyama Sôshun, appears to be an idler getting by on the income from his wife’s gambling house, but he apparently has unlimited sources of money. Despite his shady background, Kôchiyama tries to help save the heroine when, after her brother has gambled away the house and shop, she is forced to sell herself into prostitution.

The seasons of early Japanese sound films will continue during the 2014 Il Cinema Ritrovato, with a focus on Shochiku.

Chris Marker’s youth returns

It has been difficult to see any of Chris Marker’s early films lately. By early I don’t mean early 1950s, but essentially anything made before La jetée (1962). As Florence Dauman of Argos Films explained in an introduction to one of the programs, Marker thought of the films made during his first decade as a director as mere trials and didn’t want them seen again. Fortunately Dauman and others made the decision not to honor his wishes. Perhaps Marker thought that his later films, more complex and philosophical (Sans soleil comes to mind), were how he wanted to be remembered. But the playful, emotional, politically committed film essays of the 1950s and early 1960s are precious and not to be abandoned. We were treated to excellent restored prints of them during the festival.

The only film that made me understand Marker’s reluctance to show his early work was Olympia 52 (1952), a documentary on the Olympic Games in Helsinki. It was Marker’s first professional feature, and it is barely competent. The coverage sticks almost entirely to the track and field events, with endless 100-meter dashes, shot-puts, hurdles, high jumps, pole-vaults, and so on. The several cameras filming the events rendered very different footage, ranging from excellent to dark gray. Cut together, these shifting images look amateurish. A brief series of shots of yacht-racing, equine-jumping, and other sports leads back to more shot-puts, hurdles, pole-vaults, and so on. Valuable practice for Marker, no doubt, but a film which bears no hint of the talent soon to burst forth.

It was wonderful to see Letter from Siberia (1958) again after so many years. David and I had taught it in an introductory class in the mid-1970s. Its repeated series of shots of a bus on a street and some men doing construction work has been an example of the powers of the sound track from the very first edition of Film Art in 1979 to the present one.

There were no subtitles on the prints, and the headphone translation could never keep up with the rapid, contemplative voice that accompanied these images, so I missed much of the point of Dimanche à Pékin (1956) and Description d’un Combat (1960). Marker’s written contribution to Joris Ivens’ documentary …À Valparaiso (1963) presaged much of his later work. His 16mm documentation of American hippies’ gently protesting assault on the Pentagon in La sixiéme face du Pentagone (1968) made me proud to be an American (something not too easy in the light of recent events).

Dwan at his peak? The 1920s

I missed most of the Dwan films, but I managed to fit in three of the four from the 1920s. These did not include the 1923 Gloria Swanson vehicle Zaza, alas, though I heard good things about it from friends who saw it. The three I caught seemed to represent Dwan at the height of his career.

I had seen the other Swanson film, Manhandled (1924) before, but it was a treat to see it again. It’s a strange mixture of realism–most notably in the famous early scene of the working-class heroine’s commute home on a crowded subway–and an absurdly melodramatic plot in which she manages to attain the pampered stature of a kept woman while maintaining her virtue. Swanson is a delight, and the fact that the film is incomplete, missing a scene in which she demonstrates her talent for mimicry by imitating various characters, including Charlie Chaplin, is a true pity. We can only hope that a complete version will someday surface.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

Dwan’s 1927 melodrama, East Side, West Side, was a considerable surprise. For a director who has a reputation for making B picture in the sound era, this high-budget production seemed remarkable. The production design and cinematography were excellent, and a ship accident scene done with models was unusually convincing. The print was a fine restoration by the Museum of Modern Art. The Iron Mask (1929, above) was introduced by Kevin Brownlow (right), who had helped supervise the restoration.

As always it was a treat to hear anecdotes from the man who had the inspired idea of interviewing stars and filmmakers from the silent era before it was too late. The Iron Mask was another impressive print, dated 1999 and bearing a Carl Davis score. I much prefer Douglas Fairbanks in his early comedies to his more famous swashbuckler films, and the story and staging in this one seemed very by-the-numbers, especially in comparison to the more imaginative East Side, West Side. Its main interest, and that was considerable, lay in the impressive sets designed by Ben Carré and William Cameron Menzies and its glowing cinematography by Henry Sharp.

By the end of the week, I was happy to have caught these particular Dwan films. From conversations with people who followed his thread more closely, I gathered that they thought the 1920s titles were the best of those shown in Bologna.

Glimpses of 1913

There was a time when the Cento Anni Fa series, programmed by Mariann Lewinsky, was a must-see for me. With the proliferation of screenings, however, seeing all of the sessions has become difficult, and I found myself ducking in and out to catch a few items now and then. I wanted to see the new restoration of Mario Caserini’s remarkable feature, Ma l’amor mio non muore!, but there was something else I wanted to see playing opposite both screenings. Luckily the Cineteca has put the film out on DVD. The catalog claims that it’s the first diva film. It stars Lyda Borelli in a spectacular performance, plus it has many complex examples of what David calls tableau staging (see here), especially in the amazing set in the frame above. One of the must-see films of 1913.

I am not a great fan of Italian (or any other) spectacles set in ancient times, and there were quite a few included in the series. They also tend to be rather long, which makes it more difficult to fit them into a packed schedule. Still, I did like Spartaco ovvero il gladiatore della Tracia (Giovani Enrico Vidali). Its minor actors and extras avoided giving the usual impression of people milling around in sets; they actually behaved as if they were living in real places in antiquity. The actress playing Emilia (not listed in the catalog) gave an engaging performance, quite the opposite of the diva approach, though Mario Guaita as Spartaco depended largely on rolling his eyes upward at frequent intervals to convey suffering. As Ivo Blom points out in his program notes, however, Guaita turns out to be the the first strongman figure, bending iron bars with his hands a year before Bartolomeo Pagano supposedly innovated this iconic gesture as Maciste in Cabiria.

More than that film, though, I was impressed by Luigi Maggi’s La lampada della nonna. It begins with an old woman knitting beside an oil lamp. When her grandchildren try to present her with a new electric one, she objects. The bulk of the film is an extended flashback set in the era of the Risorgimento, with the heroine in her youth helping to shelter a wounded officer and falling in love with them. The lamp, seen unobtrusively in the background of several shots, comes to play a key role as a signal in the climactic scene. Again there is an unusual degree of naturalness in the acting, with the extras in the military campground scene, for example, all given bits of plausible action to collectively present the impression of an actual campground. The flashback structure, framing, staging, and acting all reminded me strongly of Griffith at the same period.

There were slight but charming films like Léonce et Toto, a very funny Léonce Perret comedy (director unknown, but probably Perret). Léonce’s wife receives a tiny chihuahua as a gift and immediately dotes on it, to the point of putting it on the table at meals. The hero is disgusted and tries increasingly devious and extreme ways of getting rid of the little pest. Another was an American documentary with the irresistible title Aquatic Elephants. Who would not delight in five minutes of elephants rolling cheerfully in a pond while silly men try to stand on them and invariably fall into the water?

DVDs and Blu-ray

Just about every film scholar and buff in the world probably knows the Criterion Collection. As a brand, it’s sort of the Pixar of high-end home-video. We all have at least some of its releases on our shelves, whether lined up alphabetically or by director or by number. This year a session was devoted to the background of the company, with guests Jonathan Turell and Peter Becker (left and right, above). The history of Criterion is a bit complicated. Briefly, it was founded in 1984 to release laserdiscs and eventually, after the introduction of DVDs in 1997, switched to that format, eventually adding Blu-ray discs. Becker joined the company in 1993.

Criterion is closely linked to the historically important Janus Films, founded in 1956 and responsible for distributing many of the most famous art films of subsequent decades. In 1966 it was acquired by Saul J. Turell and William Becker, the fathers of the two speakers. Their sons are now co-owners of the Criterion Collection, of which Peter is the president; Jonathan is director of Janus.

To David’s and my generation of film students, Janus was a key player in our discovery of art cinema. How many of us, I wonder, first watched many of the classics that now grace Criterion DVDs through the landmark PBS series, “Film Odyssey,” in 1972? I first saw and was bowled over by Ivan the Terrible in that series. Three years later, when I was working on my dissertation on the film, I called Janus and got through to Saul Turell. Could I possibly borrow 35mm prints of the two parts of the film, I asked, explaining that I needed and to take frames from good copies. He gave me the name and phone number of a person in the company’s storage facility to call, and she arranged to ship the prints to me. I was able to spend weeks in front of a Steenbeck in the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research, wallowing in strange, beautiful images and sounds. Nearly all the illustrations in my book, Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible, were taken from those prints.

That same spirit of cooperation with academic film studies has lived on. David and I are grateful for our friendly relationship with the Criterion team, who have cooperated in our creation of video-based online examples tied to Film Art: An Introduction. (The examples all come from Janus films; a sample analysis of a clip from Vagabond is available on YouTube.)

The pair’s presentation included a video, The Criterion Collection in 2.5 Minutes. It features over 600 clips from the collection as of September 1, 2012, chosen and edited by Jonathan Keogh, clearly one of the company’s most devoted fans. Although cut too fast too allow the viewer to identify every title (and I must admit, I don’t think I could recognize every single one, even with longer excerpts), it’s an exhilarating paean to great cinema.

The plaudits in the festival’s annual DVD contest were spread, deliberately or not, among many DVD/Blu-ray companies, with none winning more than one award. A number of items that we’ve covered here took home awards: Flicker Alley’s collection of films by the Russian firm in Paris, Albatros, was deemed the best boxed-set of silent films; and Edition Filmmuseum’s set of four Asta Nielsen films shared the award for best rediscovery. Our friends at the Belgian Cinematek won best Blu-ray boxed set for the “Henri Storck Collection.” Criterion took home best Blu-ray for its edition of Paul Fejos’s Lonesome. For these and the other winners of this year’s DVD awards, see Jonathan Rosenbaum’s website. (As one of the jurors, he explains the changes in the award categories this year.)

The Return of Carbon Arcs

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

I’m old enough to remember when carbon-arc projectors were the norm. Gradually xenon lamps replaced them, starting in 1956. This year, the festival put on two outdoor screenings in the courtyard of the Cineteca’s building. These started at 10 pm, so they competed with the bigger shows in the Piazza Maggiore. I usually don’t go to the Piazza screenings, since they tend to end late, and I don’t want to fall asleep during the 9 am screenings the next day. But the two programs, billed as “Il Cinema ambulante Ritrovato. Tesori dal Fondo Morieux,” were considerably shorter, so I attended the first one. As the name suggests, the idea was to simulate a traveling cinema of the early era. The first screenings included one Pathé film from 1904 and five others from 1906, some with hand-stenciled color. All six were rediscovered titles.

They came from the remarkable 2006 find of a wealth of films, equipment, posters, and even sets and puppets, in a warehouse in Belgium. The collection all originated from the stock of the traveling Théâtre Morieux, which had started with puppet and magic-lantern programs, adding films in 1906. All this material had been in the warehouse for a century and was in good condition.

The projector used for the program was not from 1906, but it was old, and very heavy. I happened to be between films when a truck with a crane delivered the projector and a generator and a team set up the equipment facing a small screen on one side of the courtyard. (At the very top of today’s entry, the crane lowers the projector body onto its platform. Above, festival coordinator Guy Borlée watches as the lamp housing is attached. Bottom, all ready to go and waiting for the sun to set.) The projector was a Prevost, of French manufacture, I would guess from the 1940s.

When 10 pm arrived, it became apparent that the light from buildings near the Cineteca could not be entirely controlled. Shadows of the trees in the courtyard were cast on the screen, with light patches between them. But traveling cinemas no doubt frequently set up in venues where nearby sounds and other distractions abounded, so we all accepted the light pollution as part of the experience.

Perhaps the most memorable of the films was Cambrioleurs modernes (“Modern Burglars,” director unknown, 1904). In some ways it was rather crude, with the set consisting of two large painted house façades facing each other, angled from the front, and a wall beyond them. The acrobatic burglars arrived over the wall to rob one house, propping a long board against an upper window to use as a chute for sliding furniture and other large objects down.

The action becomes faster and more impressively choreographed as police arrive, also over the wall, and give chase. Soon burglars and comic cops are diving through windows and doors in the two buildings, as well as performing comic acrobatics on the chute. The whole thing, as far as I could tell, was done in a single take, though there might have been some invisible cuts. If it was indeed one shot, it was a most impressive piece of staging and performance.

This ‘n’ that

Jean-Pierre Melville’s 1963 crime/road movie L’Aîné des Ferchaux (based on a minor Georges Simenon novel) is almost impossible to see on the big screen, apparently due to some sort of rights problem that keeps the French distributor from circulating it. (It is available on a region 2 French DVD without subtitles.) The festival managed to show it in the European widescreen thread by borrowing a print from Svenska Filminstitutet, complete with Swedish subtitles. Translations in Italian and English were projected on small screens below the image. I quickly got accustomed to skipping down to the read the third set of subtitles. It’s certainly not one of Melville’s masterpieces, but it’s definitely worth seeing.

The basic premise is that an unscrupulous banker, Dieudonné Ferchaux (veteran French star Charles Vanel), flees arrest by flying from Paris to New York and then setting out toward the South via car. Michel Maudet, an unsuccessful young boxer (Jean-Paul Belmondo), also unscrupulous but so far with no apparent serious crimes to his name, goes along as his secretary. Although the two seem to like each other, Michel becomes increasingly tempted to steal the suitcase stuffed with cash that Ferchaux has picked up in New York, while Ferchaux seems to lose interest in visiting various other places where he has stashed away large sums. The gradual switch in their power relationship furnishes one main line of interest.

The film is also remarkable in that the two stars did not go to the U.S.A. to appear in the considerable amount of landscape footage shot there by a second unit. Instead, they worked in interior sets in France, as well as exteriors that pass for America. Melville managed to stitch these two kinds of footage into a reasonably convincing depiction of an American road trip.

Another film that has long been hard to see outside Italy, at least in its original form, is Rossellini’s L’Amore (1948), two contrasting short tales displaying the acting talent of Anna Magnani. The first, Une voca umana, is based on Jean Cocteau’s  much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

much-adapted short play, La voix humaine. Confined to an apartment, it concentrates on a woman talking on the phone with the lover who has recently left her, trying to convince him that she has adjusted to the break-up while demonstrating through her behavior that she is devastated. Rossellini never places the camera much further back than a plan-américain position, and most of the time the framing displays Magnani’s face in close-up. Short though it is, it becomes repetitive, and it is too evidently a display of virtuoso acting.

The longer second part, Il Miracolo, is more engaging and original. It is based on an idea by Fellini and a script by Tullio Pinelli and Rossellini. A feeble-minded homeless woman, Nannina, who is tending a herd of goats near a small Italian village, meets a traveler (played by Fellini, left) whom she, being very pious, assumes to be St. Joseph. He offers her wine and, when she falls asleep, rapes her. Learning that she is pregnant, and not realizing what the traveler did, Nannina becomes convinced that she is carrying the baby Jesus. She is teased and hounded by the townspeople. This part of the film led to censorship problems, not because of the sexual content (the rape is simply skipped over and merely implied) but because of the apparent parody of the Immaculate Conception. (This, too, has been available in a mediocre copy without subtitles on an Italian DVD.)

Apart from its innate interest, L’Amore is historically important for the “Miracle Decision” in the U.S., where it was banned for sacrilege. The Supreme Court decision in the case led to the extension of first-amendment protection to cinema.

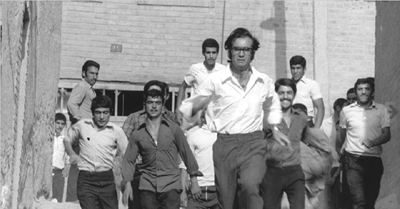

Il Cinema Ritrovato has become a venue for the exhibition of the latest restorations by Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Foundation. This organization restores films from countries whose archives do not have the means to do such work. Since 2007, the foundation has preserved on average three films a year. This year the items on show at Bologna included Filipino director Lino Brocka’s Manila in the Claws of Light (1975, also known as Manila in the Claws of Neon). I had never seen a Brocka film (it’s discussed in a passage of Film History: An Introduction, for which David was responsible), but I was impressed by this one, widely considered to be his best.