Archive for the 'Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato' Category

Solo in Bologna

Kristin here:

Two days before David and I were to set out for Bologna and its annual Il Cinema Ritrovato festival, back pain struck him. He decided not to go, and so our coverage this year will be briefer. I struggled to see as much as possible, but if anything, the program was even more packed than last year.

The auteurs

The main threads included four directors who are of historical interest. Raoul Walsh was the main attraction, with emphasis less on familiar classics like Roaring Twenties and White Heat and more on hard-to-see items like Me and My Gal and other early 1930s films. Lois Weber, the first important female director in American cinema, was represented with as complete a retrospective as possible, including fragments from features not otherwise extant. Jean Grémillon, one of the less famous French prestige directors during the 1930s and 1940s, was extensively represented. And there was Ivan Pyriev (or Pyr’ev, going by the program notes’ spelling), most famous as one of the main proponents of the “kholkoz [collective farm] musicals” of the last 1930s and 1940s.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

I had seen a couple of Pyriev’s films and decided to see as many as possible of the series on offer, programmed by our long-time front-row neighbor in the Cineteca venues, Olaf Möller. Pyriev is an interesting case historically. He came to filmmaking just as the Soviet Montage movement of the 1920s was coming under official pressure for its formal complexity.

The Civil Servant (or The State Functionary, 1931) was a full-blown, skillful leap into Montage, with an prologue of trains coming into Moscow, shot with canted framings, low angles, and quick cuts with trains moving left, then right. The rest is a satire on bureaucracy within the national railroad system—ostensibly set during the Civil War but clearly a contemporary story. It’s broad in its humor, and it has the obvious typage in the choice of actors, the wide-angle lenses that the Montage filmmakers explored in the late 1920s, and other scenes of quick cutting with jarring reversals of directions.

Official dislike of The Civil Servant kept Pyriev from directing again for three years. Turning his back on Montage, he went to the other extreme, helping to develop the kholkoz (collective-farm) musical and making some of its liveliest, most entertaining, and most enthusiastic examples of that genre. His Traktoristi of 1939 was not shown during the festival, but one that I hadn’t seen, Swineherd and Shepherd (1941), is fully its equal. From the moment the film begins, with the camera madly tracking backward through a birch forest as the heroine runs full tilt after it, singing joyously to the masses of pigs that emerge from corrals and gallop along with her, the spectator realizes that this film will be exactly what one wants and expects from Pyriev.

A later entry in the genre, The Cossacks of the Kuban (1950), was even better, and I can see why it is Olaf’s favorite. The opening vistas of immense wheat fields, gradually moving to scenes with tiny figures and finally to ranks of harvesting machines and trucks achieves a genuine grandeur, aided considerably by the fact that by this point Pyriev is working in color. The story goes beyond the simple stock figures of some of the earlier musicals, with a stubborn Cossack who heads one collective farm nearly missing his chance at romance with a widow who heads a rival farm.

Overall, I like these films a little better than those of his more famous colleague in the creation of buoyant musicals, Grigori Alexandrov. Yet it has to be mentioned that there is a certain underlying unease in being entertained by films that created hugely idealized images of life on collective farms. In reality many peasants were starving, and few were working with such cheerful enthusiasm to increase production for the sake of the great Soviet state. One might rationalize this dissonance by thinking that Pyriev was perhaps making fun of his subject with over-the-top dialogue and musical numbers. Yet surely to many audiences at the time, this was escapist entertainment, and urban audiences may have had little sense of the blatant inaccuracy of the portrayals of the countryside.

Two more straightforward dramas, The Party Card (1936, below) and The District Secretary (1942), a war story, were more conventional Socialist Realist works, skillfully done but lacking the appeal of Pyriev’s lighter films.

It was sad to see the one post-Stalinist film from Pyriev’s late career, his adaptation of The Idiot (1958). A sumptuous production, again in color, it consisted almost entirely of overblown confrontations among characters. The actors shout all their lines at each other with almost no variation in the dramatic tone, with everything underlined by an amazingly intrusive musical score.

I saw only a few of the Walsh films, since they frequently conflicted with the Pyrievs and Grémillons and just about everything else on offer. To me, the director was a bit oversold. Peter von Bagh’s introduction to the catalog says, “Unjustly, Raoul Walsh, although blessed with so much cinephilic worship, is usually placed a few notches below his more revered colleagues Ford and Hawks. Now he will have a chance to be upgraded, in our continuing series featuring extensive screenings from Walsh’s silent period through his very rare early sound films.” Perhaps Walsh will go up a notch in people’s estimations—the screenings of his films were certainly very popular—but not, I think, the few notches it would take to place him alongside these two other masters. I enjoyed Me and My Gal, a rare 1932 comedy in which Spencer Tracy and a very young Joan Bennett adeptly exchange snappy patter, yet it occurred to me more than once during the screening that Twentieth Century (1934) is a much funnier film.

The Big Trail, shone in its original wide-screen Grandeur format on the giant Arlecchino screen, was better than I expected. Walsh was given enormous resources to tell the story of a large wagon train making its way to Oregon from the Mississippi. He showed off the crowds of wagons, cattle, and people by the simple expedient of raising the camera height so that most of the screen’s height became a tapestry of people stretching into the distance, all going about their business while the main dramatic action in the foreground occurred. This often involved a very young John Wayne, whose occasional awkward delivery of lines managed somehow to fit with his character.

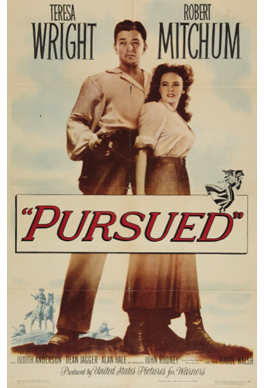

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Pursued (1947), shown in an excellent 35mm print, was one of the few certified Walsh masterpieces in the series. Of course I enjoyed it. It struck me how crucial the casting of Teresa Wright as heroine Thor Callum was. So often Westerns have minor actresses as the love interest, women that one can seldom recall seeing in any other film—starlets rather than stars. Thor’s dramatic arc is pretty extreme and somewhat implausible, but Wright manages to make the character convincing and sympathetic, as well as an effective counterpoint to Robert Mitchum’s stolid Jeb Rand. James Wong Howe’s cinematography was also a big plus.

Few of Walsh’s pre-1920s films survive, but those few were shown. I skipped the wonderful Regeneration, having seen it multiple times, but I caught The Mystery of the Hindu Image, notable mainly for Walsh’s own performance as the detective, and Pillars of Society, a somewhat stodgy adaptation of the Ibsen play.

I can’t say much about the Weber films, since they were consistently in conflict with screenings of films by the other main auteurs. I regret having skipped one Pyriev film, Six O’clock in the Evening after the War (1944) to see Shoes (1916), which had been touted as one of the director’s best. It proved a considerable disappointment, stuffed with expository intertitles that often simply described what we could already see from the action in the images. This may have been because Weber’s “discovery,” Mary McLaren, was so inexpressive. She almost constantly wore the same expression of resigned sadness at her family’s grinding poverty, varying it occasionally with a look of annoyance at her father’s shiftless behavior. I tried to steer people to The Blot, which is probably Weber’s masterpiece among the surviving films.

It was fairly easy to see most of the Grémillon titles, because a number of them were repeated in the course of the week. I enjoyed Maldone, which I had seen once long ago. Its story involves a runaway heir to a large estate who has run away as a young man and now, in late middle age, works on a canal barge. Infatuated with a beautiful gypsy and spurned by her, he returns to claim his inheritance, only to be disgusted by gentrified life. Like Pyriev, Grémillon came late to one of the commercial avant-garde movements of the 1920s, French Impressionism. He uses the subjective camera effects and the rhythmic editing in a straightforward way, with little of the flashiness of a L’Herbier or a Gance. Maldone and his subsequent film, Gardiens des phare (1929), shown at the festival in a tinted Japanese print, remind me of perhaps the best filmmaker of the Impressionist movement, Jean Epstein.

This legacy might logically have led Grémillon into the Poetic Realism of France in the 1930s. Unfortunately his first sound film, La petite Lise (1930), which might be said to fit into that tradition, was not shown. After seeing several of the films on offer this year, I still think it may be his masterpiece. (We talk about it briefly in the section on early sound cinema in Film History: An Introduction.) Though some might argue that he has at least one foot in that tradition, his work is perhaps closer to what the Cahiers du cinéma critics later dubbed the Cinema of Quality.

As for the others I caught: L’étrange Monsieur Victor (1938, dominated by Raimu as a successful merchant who is not all he seems), Remorques(1939-41, perhaps Grémillon’s best-known film, re-teaming the favorite French couple of the 1930s, Jean Gabin and Michele Morgan), and Pattes blanches (literally, “White putties,” 1948). I enjoyed them all, and yet there was no sense of discovering an overlooked genius. Best of the sound features for me was Pattes blanches, which tempered Grémillon’s taste for melodrama with a hint of surrealism. The obsessive young wastrel Maurice (played by a very young Michel Bouquet), the gamine hunchback maid who falls in love with the reclusive and menacing local nobleman, and the nobleman himself, invariably bizarrely clad in his white puttees, help give the film a fascination that the others, for me at least, lack.

The themes

There were other threads oriented by genre or topic or period. These I sampled when it was possible to insert them into my schedule. One of these was “After the Crash: Cinema and the 1929 Crisis,” which included an intriguing potpourri of documentaries and fiction films from several countries and political stances, from Borzage’s A Man’s Castle to two short films by Communist-leaning Slatan Dudow, director of Kuhle Wampe. Because of my interest in international cinema styles of the late 1920s and early 1930s, I went to Pál Fejös’s Sonnenstrahl (“Sun Rays,” 1933) was shown in the festival’s first time slot, 2:30 on Saturday afternoon. It thus competed with the first showing of the Grandeur version of The Big Trail and the first program of the “Cento anni fa” set of 96 films from 1912, but such is Bologna’s lavish scheduling.

Fejös, a Hungarian, made films in Hollywood, France, Denmark, Sweden, and a number of other countries. Sonnenstrahl, with its romance between German actor Gustav Fröhlich and French leading lady Annabella, is basically a reworking of the director’s best-known film, Lonesome (1928), with touches of 7th Heaven (Borzage, 1927), redone for the Depression era. It’s a pleasant enough piece, though not up to Fejös’s best work of the 1920s. Again, the program claims to too much for the filmmaker by saying that some historians consider him “as one of the cinema’s great poets, along with Murnau and Borzage.”

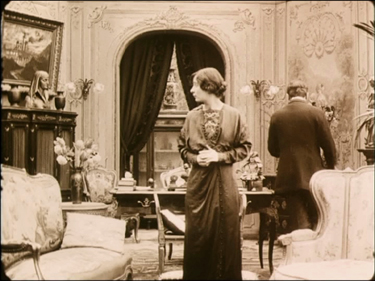

The Depression program also included a surprisingly good early sound film by Julien Duvivier, David Golder (1931, above). It’s the story of a wealthy businessman, played by Harry Baur, who discovers that his wife and daughter love him only for his money. How he could have lived this long with them without realizing this is perhaps a weakness in the plot, but from the start Duvivier showed a remarkable assurance in framing, cutting, and camera movement that was continually in evidence. Sets by the great Lazare Meerson also enhanced the style.

Baur also starred as Jean Valjean in Raymond Bernard’s 1934 three-part Les Misérables. I skipped the screenings, since the film is available in a Criterion boxed set (along with Bernard’s remarkable 1932 anti-war film Wooden Crosses). The Bernard film was part of the “Ritrovati and Restaurati” thread. The presence of Baur in both David Golder and Les Misérables led to the Depression and Ritorvati threads to weave together to produce a third: “Homage to Harry Baur.”

The only other entry in this brief thematic collection was Duvivier’s La tête d’un homme (1933), the third film based on a novel by Georges Simenon. Baur stars as Commissioner Maigret, and Valery Inkijinoff (known largely as the hero of Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia/The Heir of Ghengis Khan, though he acted in numerous other films as well) plays the doomed, obsessive villain, Radek. The film is not as accomplished as David Golder, but it’s an entertaining little thriller with some novel twists. Early in the film the murder is revealed, and we know from the start the Radek committed it. The duel between him and Maigret becomes the focus of the action. Moreover, the very first scene introduces a thoroughly unlikeable fellow who initially seems to be the villain, a womanizing cad who lives by gambling and other unsavory activities, yet who himself eventually comes to be tormented and threatened by Radek.

Another intriguing thread was “Japan Speaks Out! The First Talkies from the Land of the Rising Sun.” Ordinarily I would have tried to see most of these, but again they conflicted with the auteur threads I was trying to follow. I did make it a point to see Mizoguchi’s first sound film, Hometown (1930, above), since it’s one of the hardest to see. A part talkie built around a famous Japanese tenor and opera singer, it was more an historical curiosity than a satisfying film. I reluctantly skipped Heinosuke Gosho’s delightful Madame and Wife (aka The Neighbor’s Wife and Mine), the first really successful Japanese talkie, having seen it a number of times. On David’s and Tony Raynes’ advice, I caught Yasujiro Shimazu’s First Steps Ashore, a romantic tale inspired by Von Sternberg’s The Docks of New York. It didn’t quite match the original (as what could?) but was an entertaining tale well acted by the two leads. The first frame below reflects something of the style of Docks of New York, but the second, more typical of the film, is pure Shochiku.

The organizers of Il Cinema Ritrovato have declared that they will continue to show films on 35mm as long as possible. Most of the screenings that I attended were indeed on film. There’s no doubt that the move to digital restoration became dramatically more apparent this year. Nearly all of the 10 pm screenings on the Piazza Maggiore were digital copies, including Lawrence of Arabia, Lola, La grande illusion, and Prix de beauté. David and I don’t usually go to these screenings, since we invariably want to see films in the 9 or 9:30 AM time slots and don’t want to fall asleep during them. But I did catch two digital restorations shown earlier in the evening in the Arlecchino.

The first, Voyage to Italy, was flawless and sharp—perhaps a little too sharp. I liked the film much better than the first time I saw it, maybe because I understood better the claims that are made for it as a forerunner of the art cinema of the 1960s, with the aimless, confused couple presaging the characters of directors like Antonioni.

Perhaps the high point of my week, though, was an entry in an ongoing thread at the festival, “Searching for Colour in Films.” There were many films in this category, which was broken down into the silent and sound eras. Bonjour Tristesse may well be my favorite Otto Preminger film. Our old friend Grover Crisp (above, with interpreter) returned to Bologna to introduce it in a digital restoration, but one which, he assured us, retained the grain of the original film. It was certainly a beautiful copy and looked great on the Arlecchino screen. (The frames at the top and bottom of this entry were taken from a 35mm copy, not a DVD or the new restoration.)

Il Cinema Ritrovato grows more popular each year. A number of our friends from other festivals and alumni of the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s film studies program attended for the first time and vowed to return. Perhaps a sign that the event is gaining real prominence internationally was the fact that Indiewire columnist Meredith Brody also made her first visit. She conveys the impressions of a newbie in a series of posts: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3, Day 4, and Day 5. For many images of the festival guests and screenings, see the official website.

David analyzes one Hitchcock-like scene in The Party Card in his On the History of Film Style.

July 9: Thanks to Ivo Blom for correcting my spelling of Harry Baur’s name.

Capellani trionfante

Quatre-vingt-treize (1914)

Kristin here:

The early films of Albert Capellani are probably the most significant of all the discoveries of the Hundred Years Ago series.

Mariann Lewinsky

During the recent Il Cinema Ritrovato, I was somewhat surprised at the relatively small audiences for the programs that included films by Albert Capellani. Those films formed the second half of a large Capellani retrospective that began during the 2010 festival. Last year’s program was a revelation to me, and this year’s only confirmed my sense that here is a truly major discovery from the period before World War I. No doubt the addition of a fourth venue and the appeal of the Boris Barnet and early Howard Hawks retrospectives drew some attendees away.

As I wrote in my first Capellani entry, his significance has only slowly become apparent over several of the festivals. Initially his films were few and scattered through the annual “Cento Anni Fa” seasons of movies made one hundred years earlier. (The first “Cento Anni Fa” program in 2003 was curated by Tom Gunning; those since have been curated by Mariann Lewinsky.)

My first entry was handicapped by the fact that almost none of the films was available on DVD, and few of them had ever been accessible for researchers to view in archives–Germinal being the main exception. For illustrations, I mostly resorted to online versions of a few of the films, mediocre in visual quality and covered with bugs and time read-outs. The situation has changed enormously in the intervening year. Many more films have been restored; many of the archival notes at the beginning of this year’s prints were dated 2011. Moreover, in May Pathé brought out the Coffret Albert Capellani, a four-disc set with seven of the best-preserved films of 1906, as well as L’Assomoir and three major features from 1913 and 1914. Filling in the gaps to a considerable extent is the Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur disc, from the Cineteca di Bologna, released just in time for the festival; it contains twelve films from 1905 to 1911. Between them these releases contain 23 films, plus some fragments. (The contents are more extensive than it might appear, since the three features alone add up to about seven hours.) Booklets accompanying the DVDs provide much up-to-date information on Capellani. It’s hard to think of an early filmmaker whose work has gone from such scarcity to such abundance in a single year. Once again, a driving force behind this dramatic improvement has been Mariann, working with La Fondation Jerôme-Seydoux-Pathé and the archives that provided print material.

I have taken advantage of this new availability to return to my earlier entry and add illustrations to descriptions of such important films as L’Arlésienne and L’Épouvante, which I could only summarize verbally when I first wrote it. This entry takes up where that one left off, with comments on several of the newly revealed films, or in one case, a new version.

For a list of all the Capellani films so far shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD, see the end of this entry.

An artist of the 19th Century meets a new art form

Those festival guests who missed the Capellani films missed, in my opinion, the rewriting of early film history. He is not simply another important silent filmmaker to be placed in the pantheon. Film by film, this year and last, I kept comparing what I was watching with what D. W. Griffith had made that same year. In each case, Capellani’s film seemed more sophisticated, more engaging, and more polished. Overall Capellani may not have been a better director than Griffith, but for the period of the French films, I believe it would not be exaggerating to say that he was: L’Arlésienne (1908) compared with anything Griffith did that year or L’Assomoir (1909) versus The Lonely Villa or even The Country Doctor. Capellani’s L’Épouvante (1911) was shown again this year; I had to shake my head in amazement that it was made the same year as another woman-in-danger film, The Lonedale Operator. Nothing in Griffith’s pre-war career comes close to Les Misérables or Germinal.

Both Griffith and Capellani came from the theatre, though the French director had already had a much more successful career there than had the American. Both had a strong bent toward melodrama and historical epics. But their styles developed along different lines. Undoubtedly Griffith’s pioneering work in editing sets him apart; Capellani never ventured far in that area. Capellani’s strengths were in the tableau style, with lengthy takes and intricately staged action. (For David’s thoughts on the tableau style, see here and here.) Rather, his strengths were in his elaborate staging of scenes, whether with one actor or a crowd. Perhaps because of his theatrical success, from early on Pathé must have given him generous budgets, for his settings are more opulent than Griffith’s, and he frequently went on location to the spectacular and picturesque landscapes and buildings of France. For example, he could simply take his team into old streets in Paris and create a more realistic impression of the city in the French Revolutionary era than Griffith could manage with the sets of Orphans of the Storm eight years later. (See left, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge, 1914; note how close Capellani places the camera to the wall at the left, exaggerating at once the sense of depth and of narrowness.)

There is no doubt that in the long run, Griffith’s editing-based approach won out and helped establish the norms that remain with us to this day. It has been all too easy to trace the history of cinema as, at least implicitly, a history of innovations in editing. The great directors were those who fit into that specific history. Although Griffith never entirely mastered the classical Hollywood style the way Allan Dwan or Rex Ingram or Maurice Tourneur did, the continuity editing system undoubtedly grew in part out of techniques he popularized. In an historiographic approach based on editing, those who did not contribute to its development are likely to be passed over. Capellani uses every technique but editing with great artistry, and hence his films may be easy to dismiss as theatrical or old-fashioned. Moreover, many of them are based on 19th-Century classics, especially by Zola and Dumas, even when they deal with an older period, notably the French Revolution in his last two surviving French features, Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge and Quatre-Vingt-Treize.

Yes, as Mariann wrote in last year’s catalogue, “Capellani’s profile made him the target of a film historical trend–now long discredited–which criticised ‘the theatrical’ and promoted ‘the filmic.’ This is perhaps why he was so underestimated.” I am not sure that the contrast between theatrical and filmic cinema has entirely disappeared even today, but if we assume that all film techniques are equal, we can better appreciate Capellani in the context of his era.

I admit that, to a film historian or buff who learned early cinema from seeing Griffith and Chaplin and perhaps Hart and Feuillade, Capellani’s films may at first take some getting used to before their virtues become apparent. A feeling for Victorian narrative art, both written and visual, would help. At first, the acting might seem histrionic, and there are probably few, if any other directors’ films that so well preserve the stage conventions of the previous century. But for the most part, the acting in Capellani’s films is quite brilliant. The lack of editing might be a hurdle for some. Capellani also entirely avoided dialogue titles, and the expository titles are few. Characters are constantly writing and reading letters, which substitute for intertitles. It’s a convention one must simply accept, and it forces the viewer to concentrate fiercely on the actors’ faces and gestures, which carry the narrative information. For me, all this simply adds up to gripping filmmaking.

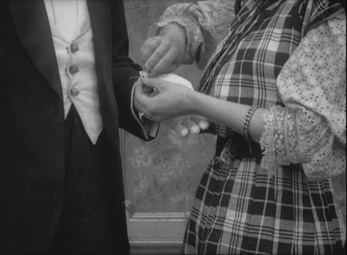

Take L’Assomoir, the earliest undeniable masterpiece from among the films so far shown at Bologna (though L’Homme aux gants blancs and L’Arlésienne come close). It is full of lengthy takes with intricate choreography. In all his films, Capellani clearly gave precise movements and business to each actor present, no matter how insignificant, and their faces, stances, and gestures, often fairly broad, make up for the almost entire lack of cut-ins. Take the scene where Gervaise and her new fiancé Copeau celebrate their engagement in an open-air café, with the proceedings interrupted at intervals by Gervaise’s former lover Lantier and the vengeful Virginie, with whom Lantier has taken up. The scene is done in a single two-minute shot, with the fluid action moving forward and back, in and out.

The ten frames below show phases of the action:

(1) Lantier in the foreground and Virginie in the middle ground watch the engagement party guests arrive. (2) Virginie speaks to Gervaise as Copeau comes forward.

(3) The guests begin to dance, with an organ-grinder coming in from the right. (4) The dancers move out left, and Copeau and Virginie begin to dance.

(5) They move out left with the organ-grinder, leaving Gervaise alone. (6) A comic friend who is continually eating comes back in to speak to Gervaise and then leaves.

(7) Lantier comes in from the right and starts bullying Gervaise. (8) Another friend comes in and drives him away out right.

(9) The dancers and organ-grinder return, with Virginie still dancing with Copeau. (10) The scene ends as Gervaise sits disconsolately while Virginie moves to Lantier and the pair watch Gervaise menacingly from the extreme right edge of the frame.

Similarly complex scenes, notably a celebration of Gervaise’s birthday, follow, culminating in a final shot that runs 6:45 minutes, out of a 35:46 minute film! (There is a pair of titles in Flemish and French that interrupt the shot early on, but the take was clearly continuous, and the titles seem likely to have been added by the exhibitor in whose collection the sole known surviving print was discovered.)

As Mariann also points out, one can find “filmic” elements in Capellani, including “the sheer photographic beauty of exterior shots, which is not to be found in the work of any of his contemporaries.” The frame at the top of this entry, made in 1914, is striking enough. (Mont St. Michel appears only in this fashion, as a tiny shape in the backgrounds of a few shots to establish that the characters have landed on the Normandy coast, but otherwise does not figure in the film.) But I suspect few would guess that the shot illustrated at the bottom was made as early as 1906.

The temptation is to go on and on about Germinal and make a long entry even longer. But Germinal has been the most familiar of Capellani’s films, and I mentioned some writings on it in my first entry. I’ll just make a few remarks about it here.

First, Capellani does a remarkably good job of capturing the naturalism of the Zola novel, as the first frame below suggests. Second, the scenes in the mine convincingly convey a sense of cramped working spaces, despite the need to shoot on sets (second frame below).

The film also makes highly effective use of the giant slag heaps behind the coal fields, placing them in the backgrounds of shots in various locales:

Clearly the resemblance of these neatly squared-off heaps to pyramids did not escape Capellani. (Compare the Red Pyramid at Dashur, above.) I think he intended this to be noticed and to be part of a motif linked to the decor of the mine owner’s study:

Like many rich men in the movies of this era, the owner is characterized as a collector of antiquities and of modern statuary with ancient motifs. (One film shown this year, I forget which, showed a rich man buying such pieces.) A case in the hallway beyond the study presumably houses his real ancient pieces, while his desk sports a small modern statue of a samurai, and the mantelpiece holds a modern Egyptianizing bust of a woman. Capellani was probably intentionally comparing the mine owner to a pharaoh and his workers to the “slaves” who built the pyramids. (This was the view of the time, though the pyramids were in fact built with paid labor.) Such a conceptual use of motifs again marks the sophistication Capellani’s films had reached by the “anna mirabilis” of 1913.

A major step forward since last year is the fact that we now have a reasonably complete print of L’Homme aux gants blancs. As it demonstrates, Capellani can cut in on those rare occasions when it’s necessary (first frame below). Here we need to see the detail of the seamstress fixing a loose button on the new gloves, not just for its own sake but because those gloves will later be lost, found by a thief, and deliberately dropped beside the body of a woman whom the thief kills. The seamstress’ identification of the repaired glove leads to the arrest of the wrong man. In the final shot (second below), the devil-may-care thief, witnessing the arrest, enjoys the irony by holding the door open for a police inspector and handing him his dropped cane. The ending is grim, since the paddy-wagon departs, leaving us to assume that the wrong man will be punished.

I can’t mention all the films shown this year, but two I particularly enjoyed were La Bohème (1911) and Le Signalement (1912), neither of which I can illustrate.

Firstly, this year Capellani’s brother Paul, whom we have seen in smaller roles in previous years, emerged as a fine actor, with perhaps his best work being as Rodolphe in La Bohème. (He played the same role opposite Alice Brady in Capellani’s American feature based on the same story, La Vie de Bohème, in 1916; there the more restrained acting style favored in the U.S. by that point makes his performance less dynamic and affecting.) The familiar tale is compressed but movingly told.

Le Signalement (“The Description”) in some ways echoes the remarkable dramatic twist of the previous year’s L’Épouvante. There a burglar ends by gaining our sympathy, and the suspense during the later part of the film centers not around the frightened heroine but around whether the terrified man will fall to his death. The heroine’s compassion makes for a moving resolution. In Le Signalement, Capellani raises the stakes. A shoemaker and his daughter (granddaughter?) Jeanette, played by the excellent child actor Maria Fromet, live in a French village. The police circulate a flyer describing a child murderer who has escaped from a nearby insane asylum. While delivering some boots, the cobbler is lured to linger in a tavern, and the murderer comes to the house. In characteristic fashion, Capellani lets most of the length of the killer’s time in the house play out in a single take into depth; the camera faces diagonally across the room toward the open door, the only place where help might appear.

When the escapee arrives, Jeannette innocently invites him in and offers him some food, including a dangerous-looking knife to cut a piece of pie. Tempted to kill and yet overwhelmed by the child’s kindness, the man sits and eats. Capellani ups the ante when Jeannette lifts a crying baby, whose presence we had not previously noticed, out of a basket to comfort it, even handing it to the man to rock. During all this we are left in suspense as to whether he will give in to his murderous obsession or resist it. At last the pair hear the police outside, and Jeannette realizes that her visitor is the killer–yet she helps him to escape out the window. Again we are torn, not wanting the child’s generous gesture to be thwarted and yet not wanting a child murderer to run loose! The plot solves the dilemma in a neat and dramatic fashion. Overall, like L’Homme aux gants blanc and L’Épouvante, Le Signalement packs conflicting emotions into a single reel.

Such density of narration is one characteristic of Capellani’s work. As Mariann wrote in the program last year: “Capellani’s speciality as a director is the broad scope of his narratives, connecting different locations and characters, which invests even short films with grandeur and space, to such an extent that the film lengths, given in either metres or minutes, often seem unbelievable. What? Can L’Épouvante really only be 11 minutes long? And Pauvre mère and Mortelle Idylle only 6 minutes each?”

Two final French features

Apparently Capellani made eight films in 1914, but as far as I know, only two survive. Both happen to deal with the French Revolution, and both are based on 19th-Century novels: Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (Dumas) and Quatre-Vingt-Treize (Hugo).

Last year I suggested that Le Chevalier might be a bit of a let-down after the heights of Les Misérables and Germinal. But it would be hard to match Germinal, and I have to admit that upon seeing Le Chevalier again on DVD, it kind of grew on me. The main problem, I think, is that Capellani doesn’t take much trouble to give the characters traits and make them sympathetic. They seem more like game pieces in service to the plot. But as always the staging and acting are marvelous, and both locations and sets, as I suggested above, give a vivid sense of revolutionary Paris.

Oddly, though, for the first time there are signs that Capellani is being influenced by cinematic trends of the day and is trying to expand his style in a somewhat tentative way. Clearly, like so many filmmakers, he has seen Cabiria and been impressed by its lumbering tracking shots. The tribunal near the end where the young lovers, Maurice and Geneviève, are condemned uses such a tracking movement well, pulling out from the lovers and the court to include the crowd that welcomes the death sentences:

In a few scenes Capellani also explores offscreen space in a way that I haven’t seen in his other films. Most dramatically, when Maurice sneaks up to the house where he hopes to see Geneviève, he appears small in the distance, disappears out the bottom of the high-angle framing, and suddenly reappears very close in the foreground, having somehow climbed up to a window:

In one scene Capellani even cuts in for a closer view and a different angle during a letter-writing scene. It’s a bit clumsy, with a mismatch on the man’s position–though not one that is worse than many attempted matches in European cinema of the 1910s:

The cut-in isn’t really necessary, though, and one would expect Capellani not to use it. This is one of the few moments in all the films shown where briefly Capellani seems truly old-fashioned, catching up with a technique that had already been in use for a few years. Here I wish he had stuck to his accustomed long shots, for it’s a sign of things to come. The next year Capellani would be working in the U.S. and making a smooth transition into continuity editing.

Capellani’s last film in France was Quatre-Vingt-Treize. With the outbreak of World War I, the subject matter, French fighting against French during the Revolution, was considered too provocative in a fervently patriotic context, and the film was banned. Capellani did not finish it but went immediately to the U.S. After the war, it was completed by his fellow theatre/film director André Antoine and finally released in 1921. There is no sign of any of the footage being by a different hand or done at a later time. It appears that Antoine simply edited the footage, perhaps to a script or shot list from the director, since the result on the screen is pure Capellani. It eschews the mild experiments of Le Chevalier and returns to a concentration on acting and a wonderful use of locations. At one point, in a single take, a troupe of Revolutionary soldiers marches past in a woodland setting. After they exit, there is a brief pause, and a man rises up from behind the foreground rocks in the path, signaling. Suddenly counter-revolutionary soldiers pop up all over the frame from the undergrowth and follow their foes stealthily in a seemingly unending stream:

In this film the characters are assigned more traits than in Le Chevalier, and the result, even at 165 minutes, is a rattling good tale.

(I mentioned that Capellani avoided dialogue intertitles. This films has some, but it may be that Antoine added those on his own.)

Despite dealing with the same historical period, the two films say nothing about Capellani’s politics, since in Quatre-Vingt-Treize the sympathies are clearly with the Revolutionaries, and in Le Chevalier, they lie with the group, including the title character, who are plotting to rescue Marie Antoinette from prison.

The American period

Given Capellani’s expertise in and long use of the tableau style of filmmaking, it is remarkable how easily he adapted to Hollywood. Only a few of his films from the early years in Hollywood survive, and His La Vie de Bohème (1916), a pleasant, well-made film, is not nearly as lively and absorbing as the French version, La Bohème (1912). I enjoyed the other features shown, Camille (1915, starring Clara Kimball Young) and The Virtuous Model (1919, starring Dolores Cassinelli), but I couldn’t help missing the French Capellani. It is hard to imagine how his career would have developed had he stayed in France. Perhaps, like Victor Sjöström and Ernst Lubitsch, he could have waited until after the war to move smoothly from the tableau style to adopt continuity editing. Perhaps, like them, he could have remained one of the top filmmakers of the silent period. (He returned from Hollywood to France after directing the 1922 Marion Davies vehicle The Young Diana. He did not direct again and died in 1931.) Good though the Hollywood features are, however, for me they inspire none of the sense of discovery and excitement that the films of the 1908 to 1914 period do.

Wishful thinking

By the 2011 festival, most of the known Capellani films have been restored. Some have improved before our eyes. In 2008 and again in 2010, the older restoration of L’homme aux gants blancs (1908) was shown. The newer, more complete restoration combines images derived from a 35mm print and a 28 mm one. A new restoration of Germinal with toning based on original color indications was shown this year.

There were also some fragments, which were saved for the seventh and final program in the series, “Borders and Blind Dates (A Workshop).” There is a version of Le Belle et la bête, for example, that is badly deteriorated, even within most of the footage retained by the restorers. What little remains suggests that the film must have been quite charming; the fragment is included among the extras on the Cineteca di Bologna DVD. There were also some films that were considered as possible Capellanis. According to the booklet accompanying the same DVD, Capellani is thought to have made anywhere from 70 to 80 films from 1905 to 1912. The number is uncertain, due to problems of attribution. Of these, about half survive, less than a third of them from the 1910-1912 period.

La loi du pardon, a 1906 melodrama of the type Capellani frequently made, is listed in the festival catalogue as “Ferdinand Zecca? Albert Capellani?” It could be Capellani, but to me most of his films of the 1906-07 years, though excellent, are not distinctive enough to be attributed to him without any documentation. Manon Lescaut (1912 or 1914; it is listed as both in the program on pages 128 and 129) was more tantalizing. An adaptation from a classic French novel, made by Pathe’s prestigious S.C.A.G.L. unit, would seem exactly Capellani’s sort of project. The first scene, set in an open-air café, seemed plausible as his work, but the rest of the film has little or nothing of his style about it. Instead there is a lack of long-held, intricately staged shots, one completely unnecessary cut-in, and too many old-fashioned painted sets. Compared to the location work in Germinal or just about any of the big films from the immediate pre-war years, these looked crude. Plus, as Caspar Tyberg pointed out to me, the action was staged more quickly than one would expect from Capellani, who often lets situations develop gradually, with many details in the gestures and facial expressions. There are some of his films in archives but apparently as yet unrestored. (According to the booklet accompanying the Coffret Albert Capellani, the Cinémathèque Française has a negative of a 1909 version of Manon Lescaut.) Otherwise I fear we must count on future discoveries in the archives for more Capellani films. Surely some will be forthcoming, now that archivists are aware of the importance of this newly revealed master. “Cento Anni Fa” will move on into 1912, 1913, and 1914, and perhaps the Capellani retrospective will resurface occasionally.

With the end of the main retrospective, however, it is safe to say that from now on anyone who claims to know early film history will need to be familiar with Capellani’s work. If you live outside Europe and don’t already have a multi-region DVD player, this might be the time to invest in one. It would be worth it just to see these new DVDs.

Capellani films shown at Bologna and their availability on DVD

Symbols used in the list:

* A film on the Coffret Albert Capellani, (La Cinémathèque Française, La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé), Pathé, two four discs with booklet, Region 2 Pal. 36-page booklet in French. There is a bare-bones filmography, with titles and dates, on page 35, but this no doubt will be revised as research continues.

** A film on Albert Capellani: Un Cinema di Grandeur 1905-1911 (La Fondation Jérôme Seydoux-Pathé, the Cineteca Bologna) Il Cinema Ritrovato, 1 disc with booklet, Region 2 Pal. Intertitles in various languages; optional subtitles in Italian, French, and English. 55-page booklet in Italian, French, and English.

+ The titles I would most like to see on a future DVD!

In last year’s entry, I expressed the hope that some films from previous years could be repeated. Whether or not that hope influenced the programming, some were.

[Added July 19: Mariann tells me that she is now convinced that La Loi du pardon is genuinely a Capellani film. I find that quite plausible.]

2005

*Le Chemineau (1905)

2006

**La Fille du sonneur (1906)

2007

*Les Deux soeurs (1907)

*Le Pied de mouton (1907)

**Amour d’esclave (1907)

2008

Don Juan (1908)

La Vestale (1908)

*Mortelle idylle (1908)

Corso tragique (1908)

Samson (1908)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908)

Marie Stuart (1908)

2009

*L’Assomoir (1909)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909)

2010

Dans l’Hellade (1909)

**Le Pain des petits oiseaux (1911)

*La Fille du sonneur (1906) (Repeated from 2006)

Notre-Dame de Paris (1911)

+Les Miserables (1912)

**Le Chemineau (1905) (Repeated from 2005)

*La Femme du lutteur (1906)

**L’Arlésienne (1908)

Eternal amour (1914)

**L’homme au gants blancs (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

**L’Épouvante (1911)

*Pauvre mère (1906)

**L’Intrigante (1910-11)

La Mariée du château maudit (1910)

**Cendrillon ou la pantoufle merveilleuse (1907)

Samson (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

*Le Chevalier de Maison-Rouge (1914)

*Drame passionel (1906)

**Le Pied de mouton (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

**La Mort du Duc d’Enghien (1909) (Repeated from 2009)

La Fin de Robespierre (1912)

+La Glu (1913)

The Red Lantern (USA, 1919)

*Mortelle idylle (1906)

+L’Évade des Tuileries (1910)

2011

La Belle au bois dormant (1908)

Le Courrier de Lyon ou l’attaque de la malle poste (1911)

+La Bohème (1912)

La Vie de Bohème (USA, 1916)

*Quatre-vingt-treize (1914, released 1921)

**[Amour d’esclave (1907) Not shown for lack of time]

+Le Signalement (1912)

*L’Âge du Coeur (1906)

**Les Deux soeur (1907) (Repeated from 2007)

Camille (USA, 1915)

*Germinal (1913)

**L’Homme aux gants blancs (1908, more complete restoration)

Le Visiteur (1911)

Marie Stuart (1908) (Repeated from 2008)

Le Luthier de Crémone (1909)

The Feast of Life (USA, 1916)

**La Belle et la bête (1908, fragment) In “Extras” on DVD

Foulard magique (1908, fragment)

Béatrix Cenci (1909, incomplete)

**La Loi du pardon (1909) By Capellani or Ferdinand Zecca

La Legend de Polichinelle (1907)

[August 13, 2012: Roland-François Lack has recently added a post on Capellani on his website, The Cine-Tourist. He gives an extraordinarily detailed run-down of the Parisian (and Vincennes) locales used by Capellani (such as the one below), with many frames from the films and both current and vintage photos of the places, as well as a few maps and some engravings and other graphics. Well worth a look!]

La Fille du sonneur (1906)

More riches from Bologna

We’re still catching up with last week’s generous Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, the world’s premiere festival of restored and rediscovered films from all eras.

DB here:

O Segredo do corcunda (The Hunchback’s Secret, 1924) was more than a curiosity. Directed by the Italian Alberto Traversa, it was the first Brazilian feature screened abroad. It also has a documentary bent in that it shows a bit of what coffee farming was like in that era. The plot traces how the budding romance between a poor boy and the plantation owner’s daughter is blocked by the overseer Pedro, who actually killed the boy’s father.

The film illustrates penetration of Hollywood filming technique around the world. The linear plot includes a flashback explaining key motivation, a romantic subplot with helper characters, and a last-minute rescue built out of parallel editing. Scenes are filmed and cut according to continuity principles, with eyeline matches and angled changes of setup. There is even a split-screen delirium sequence.

Yet the film was out of step with Hollywood in one respect: the proportion of titles, especially dialogue titles. O Segredo do Corcunda has a lot of intertitles; they make up 22% of all its 518 or so shots. Somewhat similar proportions can be found in the mid-1920s in Hollywood, as Upstream and Cradle Snatchers indicate. But what’s different is the proportion of dialogue titles to expository ones. Most Hollywood films of the period have a very small proportion of expository titles, usually no more than 15% of all titles, and often much less. Fazil, discussed in an earlier entry, has 118 dialogue titles and only seven expository ones. But in O Segredo the 65 dialogue titles comprise 57% of all titles, leaving the 49 dialogue titles to make up the difference.

Why does this matter? In The Classical Hollywood Cinema, I argued that American generally tend to favor methods that let the story seem to tell itself. Although an early silent feature might have many expository titles, in the late 1910s and the early 1920s, films began minimizing expository titles and letting dialogue carry the action. By the 1920s a US film would have relatively few expository titles. The pattern is visible across a film as well, with expository titles most common in the opening scenes but diminishing as the plot proceeds. In Segredo, not only do expository titles do more work, they’re spread out pretty evenly across the film. An external narrational authority is there from start to finish.

I suspect that the method of fading external authority is an identifying mark of American silent film and is rarer in other cinematic traditions. If that hunch is right, we can ask: Why did other countries persist in using expository titles so much? Matters for further research!

Polustanok (A Small Station).

Boris Barnet started out as one of Lev Kuleshov’s circle, and he became a well-established director. Not as famous as the Big Three (Eisenstein, Pudovkin, Dovzhenko) or even Kuleshov, Barnet directed charming comedies like The Girl with the Hat Box (1927) and The House on Trubnoi Square (1928) and heartfelt dramas warmed by music, such as By the Bluest of Seas (1935). But many of his later films are unknown to me. I couldn’t catch all the titles in the Barnet retrospective, but the two features and one short I saw convinced me of his gifts.

Those gifts come off as gentle and genial in the wartime feature A Good Lad (Slavny Maly, 1942). A French pilot’s plane is downed in a Russian forest, where a resistance group is hiding out and forming its own little community. Living under the imminent threat of discovery doesn’t forestall songs, romantic affairs, and mistakes born of the language gap. (“I love you.” “I don’t understand.” “I don’t understand.”) Somber notes are struck when the village poet strides along singing patriotic tunes set to Borodin’s melodies, and soon the German soldiers are finding some partisans to threaten. With the villagers’ help the plane is repaired and soars into the sky to engage the enemy. The film seems to take place in an otherworldly realm, floating between an idyll and a battlefront drama.

Twenty years later Barnet could indulge in a more relaxed pastoral. Polustanok (1963) is variously known as Whistle Stop or A Small Station. A Moscow scientist goes on a painting vacation to the countryside. He settles into a collective farm where many painters have come before and winds up in a shed that is underfurnished (the chickens have to be shooed out) and overdecorated (the walls are covered with graphic inspirations). With something of the episodic structure of M. Hulot’s Holiday (though without its rigorous underlying timetable, at least to my eye), A Small Station rings variations on the fish-out-of-water situation of Pavel Pavlovich. He makes friends with a local delinquent, the party man, and cute girls. He even gets some support from the grumpy farm lady who has been painted many times and in many styles, some surprisingly unofficial in those Krushchev years. After Pavel sets painting aside, he and the delinquent build a brick stove for his shed. He signs it as if it were a work of art. He can return to Moscow reinvigorated, and as so often happens in films like this (Local Hero comes to mind), the departure is bittersweet.

Barnet’s light touch was nowhere in evidence in the long-unavailable short Priceless Head (A Bestsenaya golova, 1942). On every corner of an occupied Polish city, the Nazis have mounted a reward poster for a wanted partisan. He realizes he’s trapped, and meeting a penniless woman unable to feed her sick child, he offers to let her turn him in. This impossible choice is rendered in precisely controlled drama, with not a wasted shot or false note. Priceless Head shows that Barnet was an outstanding dramatic director, as well as Soviet cinema’s most unassuming lyricist.

Underground New York.

What would a trip to Bologna be without a foray into the 1910s? Kristin will have a lot to say about the biggest discovery, the consistent excellence of Alberto Capellani, so I’ll contribute a mite on the things I enjoyed. Of course I tracked the Feuillades. Roman Orgy (1911) was fairly tame, even allowing for a climax of Christians crunched by lions in the arena. Bébé est neurasthénique (1911) was shamelessly silly, with the little rascal pulling dishes off the table and then escaping punishment by feigning illness. His gift for rolling his eyes back into his head proved to be as funny on the tenth instance as on the first. But the most peculiar Feuillade entry was a sort of satiric PR response to Les Vampires. Lagourdette Gentleman Cambrioleur (1916) shows Musidora, no longer Irma Vep, absorbed in reading the novelization of Les Vampires. Marcel Levesque decides to woo her by pretending to be a debonair thief, so he convinces his valet and cook to pose as wealthy opera patrons. He’ll then display his skills by robbing them in front of Musidora. The two-reeler accepts, in a mocking spirit, the charge from bluenoses that sensational stuff on the screen only encourages crime.

Lagourdette has its nice points, notably its tendency to supply very large close-ups of its principals. (Who knew that Musidora had freckles?) This technique, almost absent from Feuillade’s features of the period, may have been an adaptation to the star-driven nature of the product. As Annette Förster noted in her introduction, the film involved a sort of product placement, and Gaumont’s stars, no less than its literary spinoffs, were branded items. The movie is minor Feuillade but significant in showing that as early as 1916, filmmakers were seeking synergy.

Mauritz Stiller began directing in 1912, and through 1914 he turned out some 20 films. All have been assumed lost, but one surfaced in Poland a few years ago. It was restored in 2011 by the Swedish Film Institute, so once more Ritrovato hosted a “second world premiere.” Gränsfolken (People of the Border aka The Border Feud, 1913) is derived from a Zola novel. A boy and a girl fall in love, but their families live on opposite sides of a border. For the girl’s father, loyalty to country comes before all else, and so he tries to block the marriage. Nonetheless the couple unite, but they face a dilemma when the two countries plunge into war. Will the young man fight for his old homeland or his new one? And will his ferocious brother kill him as a traitor?

Stiller had mastered the tableau style of the 1910s. Although nothing in the film displays Victor Sjöström’s virtuosity in staging, Stiller gets a lot of mileage out of the two families’ densely furnished parlors. Every inch of the frame is used at some time or another; a figure lying on a tall bed can roll into view in the upper left corner of the shot. The exteriors are picturesque and often framed geometrically. I need to see Gränsfolken again to do justice to its visuals, but the fairly restrained playing and the emotional intensity of the situation prefigure what would become signature elements in Stiller’s style in work like the Thomas Graal comedies and of course Herr Arne’s Treasure (1919).

Jumping far ahead to the 1960s, it was a pleasure to see Gideon Bachmann’s Underground New York. Shot in 1967, it treats protests against the Vietnam War as of a piece with the avant-garde film scene. Shirley Clarke, Jonas Mekas, the Kuchars, Bruce Conner, and other legendary figures are captured in quick, telling portraits. Andy Warhol confides that acting in his film involves not performance but “faking it.” There are many lively moments—Conner dancing in pegged pants, Mekas tearing up company checkbooks—and enough nudity to suggest that new filmmaking and political protest were tied to erotic liberation.

Bachmann, dynamic and articulate at 84, offered many thoughts on the film and how he wound up making it. A cosmopolitan intellectual, he began producing an interview show for WBAI radio, a major initiative in American film culture. His talks with Fellini, Tarkovsky, and others proceed from his conviction that “The person is more important than the film.” By that he means that you never really make the film you have in your head—you get at best 80%–and you end up lying about your mistakes. But the person has an achieved identity. “My life’s work is to meet the people behind the camera.”

Bachmann, dynamic and articulate at 84, offered many thoughts on the film and how he wound up making it. A cosmopolitan intellectual, he began producing an interview show for WBAI radio, a major initiative in American film culture. His talks with Fellini, Tarkovsky, and others proceed from his conviction that “The person is more important than the film.” By that he means that you never really make the film you have in your head—you get at best 80%–and you end up lying about your mistakes. But the person has an achieved identity. “My life’s work is to meet the people behind the camera.”

Over eight hundred hours of those meetings have been preserved in Bachmann’s audio archive, Vox Humana—The Voice Bank. The model for Bachmann has always been not the interview, with its predictable questions and stale answers, but the conversation, “just friends talking.” Bachmann, a straightforward and serious man, was forty when he made Underground New York, and he retains the mature lucidity on display in his comments in that film—and in his film criticism, which I remember reading with pleasure in Film Quarterly in the 1960s. We’re likely to get an earful of his archive, for Criterion has already signed up the North American rights to the Vox Humana collection.

KT here:

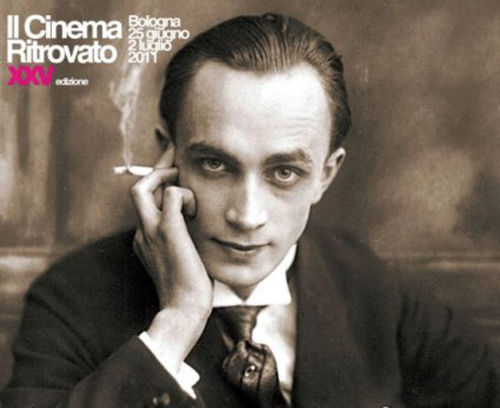

Given the great abundance of films at this year’s festival—some might say an overabundance—I singled out out three threads to concentrate on. I resolutely ignored the others unless I could somehow fit a film in here and there. Naturally I chose the second part of the Albert Capellani retrospective that began last year; I wrote about the 2010 season here and will do a follow-up soon. I also chose the 1911 “Cento Anni Fa” programs, since, as usual, the festival presented films from exactly one hundred years ago. Not surprisingly, the most interesting among these were by Feuillade, which David covers above, and Capellani. Finally, since I have a particular interest in Weimar cinema, I stuck with the “Conrad Veidt, From Caligari to Casablanca” retrospective.

The title refers to what are probably Veidt’s two most famous roles, as the somnambulist Cesare in Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (1920) and his final performance, as the Nazi Major Strasser, in Casablanca (1942). But presumably on the assumption that just about everyone knows these two films well, Il Cinema Ritrovato didn’t show either one. Instead, the program successfully assembled a group of lesser-known Veidt performances. Despite the fact that I’ve seen a lot of Veidt’s films from the 1910s and 1920s, almost all the items on offer were new to me. The selection seemed designed to display the considerable range of an actor often identified with villainous roles, like his portrayals of Nazis in the 1940s, or downright demonic, like Ivan the Terrible in Waxworks.

Almost none of the films in the program were newly discovered or restored. Most were drawn from existing prints held by various archives. The Wandering Jew, for example, was a beautiful print from the National Film and Television Archive, but it was full of splices, often with whole lines of dialogue missing. The exception was The Thief of Bagdad, a newly restored version shown as one of the evening screenings in the Piazza Maggiore. Not having the stamina that we once had for nearly round-the-clock film viewing, David and I missed all of those. I also passed up the familiar Waxworks (1924, Paul Leni), which I gather was shown in the same dark, indistinct version that has been circulating for years. It’s a film ripe for restoration, but perhaps no better material survives. That would be a pity, since it’s the one film that three of the main Expressionist actors, Veidt, Werner Krauss, and Emil Jannings appeared in together. Leni is also an interesting director, as well as a set designer; perhaps a retrospective of his largely unknown body of work could be arranged someday.

Apart from these, the program pulled together an admirable selection of films. The earliest, Dida Ibsens Geschichte (“Dida Ibsen’s Story,” 1918, Richard Oswald), was a sequel to the original version of Das Tagebuch einer Verlornenen, later remade in 1929 by G. W. Pabst with Louise Brooks. Veidt features relatively little in Dida Ibsen, playing a rich man who takes Dida as his mistress. The film is stolen by Werner Krauss, however, playing a highly eccentric man who forces Dida to marry him and then terrorizes her and their little daughter. Their home is crammed with what appear to be the exotic souvenirs of the husband’s adventures, including Asian furnishings and curios, as well as a parrot, crocodile, and lively python. Krauss carried the latter curled around his body much of the time. Indeed, where else could one see two snake-carrying villains in a single week? Three days later I watched Burl Ives sporting a cottonmouth moccasin in Nicholas Ray’s Wind across the Everglades, a film from the color series that I managed to fit into my schedule.

Veidt’s demonic roles are well represented here not only by Waxworks but also by the 1922 historical epic Lucrezia Borgia (also directed by the prolific Richard Oswald). I had expected the latter to be the usual stodgy historical drama, but it was livelier and more enjoyable than I had expected. Veidt plays the ruthless Cesare Borzia, lusting after his sister Lucrezia and scheming against her repeatedly until he leads a suicidal attack on the fort where her husband is defending her. The fort itself is an immense, lumpy set of the kind common in German epics of the 1920s, That, along with the huge armies of extras, suggests that this was one of the biggest-budget films prior to Metropolis.

Veidt was more versatile than such roles would suggest, however. He often played intense, suffering young men, as in one of F. W. Murnau’s earliest surviving films, Die Gang in der Nacht (1920, not, as in the catalogue, 1922). Veidt plays a supporting role as a mysterious, spiritual young painter who has been blinded. His more cheerful side was in evidence in the wonderful musical The Congress Dances (19331, Eric Charell); there as the confidently scheming Metternich he smilingly relishes eavesdropping on officials and politicians and reading their sealed letters with a contraption involving a bright lamp and magnifying lenses. He plays a Prussian military hero in Die letzte Kompagnie (1930, Kurt—later Curtis—Bernhardt), an early talkie shown in what appeared to be an English-language version, part dubbed, part redone with the actors speaking English.

Veidt’s ability to play both sympathetic and dastardly characters was shown off in the final two offerings, scheduled back to back, in both of which he plays diametrically opposed brothers: Die Brüder Schellenberg (1926, Karl Grune) and Nazi Agent (1942, Jules Dassin). Seeing the two films juxtaposed was odd. In each one, the evil brother is played by Veidt as he usually looked, with dark hair slicked back from his face, while the virtuous brother is gray-haired, reserved, with a little goatee (below). One has to suspect that Dassin saw the earlier film, and in fact Die Brüder Schellenberg was screened at the festival in an American print entitled Two Brothers.

The Mosfilm site offers some Barnet titles for downloading, without subtitles and for a fee. The short list includes A Small Station. The opening twelve minutes, with subtitles, can be found on YouTube. A Good Lad is available here, for free, without subtitles.

For a lovingly compiled fan site, see The Conrad Veidt Society, but beware the Wikipedia entry.

[Thanks to Armin Jäger for correcting my mistake on the date for The Congress Dances.]

Conrad Veidt and Conrad Veidt in Nazi Agent.

Written on the rewind

The High and the Mighty: The view from the café at the Cineteca of Bologna.

DB here:

Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato has just ended, and while Kristin and I hustle to write some final entries about films we’ve seen, here are a few images, or maybe lobby cards, from the biggest Ritrovato yet. If we’ve so far posted fewer dispatches than in previous years…that’s largely because the expanded screening list (a fourth venue was added) kept us busy!

If you’re unfamiliar with the Ritrovato, our 2007 orientation is here. For a complete account, check our category Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato. And for many more images from the festival, see the Ritrovato page here, which includes shots of Bertolucci and Charlotte Rampling, as well as a video of a Piazza Maggiore mini-concert.

The Crowd: A full house for Murnau’s Der Gang in die Nacht.

Café Lumière: Pierre Rissient, man of the cinema, and Li Cheuk-to of the Hong Kong International Film Festival.

Le silence est d’or: Silent-film impresarios Jon Gartenberg of Gartenberg Media and Kim Tomadjoglou, curator of the Alice Guy Blaché retrospective.

Summer Storm: Gian Luca Farinelli of the Cineteca and Peter Becker of Criterion take shelter in a portico.

In the Mood for Love: Susan Ohmer and Don Crafton of Notre Dame University.

Make Mine Music: Maud Nelissen and Donald Sosin, virtuoso accompanists for Bologna screenings.

Le Doulos (x 2): Olaf Möller and Christoph Huber of the Ferroni Brigade pioneering a new form of digital cinema.

The History Boys: Naum Kleiman of the Moscow Central Cinema Museum, and Ian Christie of Birkbeck College, University of London.

Gentleman Jim: Jim Healy of the University of Wisconsin–Madison Cinematheque.

Cinema Paradiso: Introduction to one of the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore.