Archive for the 'Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato' Category

Everybody’s Irish

Three Bad Men (1926) at the Piazza Maggiore; Orchestra del Teatro Communale di Bologna conducted by Timothy Brock. Photo by Lorenzo Burlando.

DB, still in Bologna:

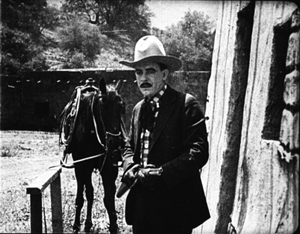

The early Ford retrospective at Cinema Ritrovato rolls on. The surviving reel of The Last Outlaw (1919) proved very tantalizing. An end-of-the-West Western, it shows its grizzled hero revisiting the town of his youthful exploits. But now, in an anticipation of Ride the High Country (1962), civilization has taken over. Cars chase Bud off the streets and the theatre features movies (Universal Bluebirds at that, a bit of product placement). Ford heightens the contrast by letting us into the hero’s memory, introduced by the title: “Memories of the past flashing back to him”—the earliest reference to the term “flashback” I recall seeing in the movies.

The plot of Cameo Kirby (1923) involves a cardsharp who tries to help a southern family but whose chivalrous intentions are misunderstood. The film’s virtues were, I’m afraid, undercut by a choppy, contrasty print. Another 1923 vehicle, North of Hudson Bay (1923) was in much better shape. A fairly routine adventure about schemers trying to take over the gold claim of two brothers, it was enlivened by a mysterious murder scene, in which a man is shot before our eyes but we can’t say exactly how. Ford later replays the scene to clarify what happened, and then sets up suspense as the trap is put in play again, this time to kill our hero.

Kentucky Pride (1923) is a turf tale narrated by a racehorse. This might have become a tedious gimmick, but the film handles it with aplomb and modest emotion. Our narrator Virginia’s Future stumbles during the race, and the scene during which she is about to be shot generates a great deal of suspense and concern. At the end, her reunion with her son, Confederacy, is smoothly integrated into the humans’ reconciliations and just deserts. In between, Virginia’s Future passes from owner to owner, in something of a rough draft for the adventures of Bresson’s donkey in Au hazard Balthasar.

Kentucky Pride is a programmer, but between the peaks of racetrack excitement we get several arresting interludes. In one scene the now-destitute horse farmer reunites with his daughter. He’s at the dinner table. She comes up behind him and covers his eyes. So far, so conventional. But he raises his calloused, dirtied hands very slowly to touch her wrists. Prolonging the gesture shows not only Ford’s delicate way with such moments but the quiet skill of Henry B. Walthall; it’s impossible not to think of similar handwork in Griffith’s The Avenging Conscience (1914) and The Birth of a Nation (1915). The scene’s subdued pathos was enhanced by the accompaniment of Neil Brand, a Bologna regular.

Kentucky Pride is a programmer, but between the peaks of racetrack excitement we get several arresting interludes. In one scene the now-destitute horse farmer reunites with his daughter. He’s at the dinner table. She comes up behind him and covers his eyes. So far, so conventional. But he raises his calloused, dirtied hands very slowly to touch her wrists. Prolonging the gesture shows not only Ford’s delicate way with such moments but the quiet skill of Henry B. Walthall; it’s impossible not to think of similar handwork in Griffith’s The Avenging Conscience (1914) and The Birth of a Nation (1915). The scene’s subdued pathos was enhanced by the accompaniment of Neil Brand, a Bologna regular.

In another horsy tale, The Shamrock Handicap (1926), the financially challenged aristocrat is an Anglo-Irish lord , and to pay his taxes he sells some of his stable to an American racing entrepreneur. His top rider, Neil, goes along, leaving sweetheart Sheila behind. Once in the US, Neil takes a serious spill and acquires a game leg. Soon the aristocrat and his 120 % Irish household are coming to America to stake everything on racing their pride filly in the Handicap. The whole thing is a pleasant tissue of contrivance and coincidence, allowing Ford some chances for sentiment, camera tricks induced by ether, and gags on Irishness. The horse handler discovers that all his old friends and kinfolk in the New World have become cops.

There were opportunities to develop Sheila as more than a pretty face (that belongs to the enchanting Janet Gaynor), but the plot puts the menfolk to the front. The scenes of Neil’s acceptance in the hard-bitten jockey world show America as a place in which ethnic minorities hang together; his best friend is a Jewish rider who keeps a black valet. The characteristic Ford sadness surfaces in a lovers’ reunion. When Neil greets Sheila at dockside, Ford gives us a painful glimpse of wounded masculine pride. Neil stands waiting with his pals. Has he recovered?

As Sheila approaches, Neil swings his crutch abruptly away from her, as if to hide it. But the same gesture sharply reveals to us that he’s now lame.

In their embrace, the crutch falls away. Neil clutches Sheila as if she were not his sweetheart but his mother; he needs consolation, not passion.

The film may be about male pride, but as ever in Ford a man’s sense of self-worth is sustained by a touching reliance on women. So it’s fitting that the walking staff Neil leaves behind in Ireland–a slip in continuity, you might think–becomes his new crutch when he comes home again for good.

Lightnin’ (1925) moves not like lightning but at the pace of its elderly protagonist, Bill (Lightnin’) Jones. The opening is a drawling play with rustic humor, centering on Bill’s laborious stratagems to hide his whisky bottles from his wife. Bill isn’t Irish, but he might as well be, like the purported Welshmen of How Green Was My Valley (1941).

Initially the film seems to depend on one of those promising screenwriting switcheroos. The couple manage a hotel perched on the border between California and Nevada, so aspiring divorcées can collect their California mail and still maintain residency in Nevada. A dividing line runs through the center of the house, and it provides some adroit byplay when a young lawyer, pursued by corrupt businessmen, teases the Nevada sheriff by hopping from state to state. The romance between the lawyer and the old couple’s adopted daughter is handled briskly, with the usual repeated-and-varied dialogue motifs (courtesy Frances Marion’s script). One might expect a climax wringing comic confusion out of the divided household. But soon the border gimmick is forgotten and Ford moves to the emotional core of the movie, the testing of the old couple’s marriage.

When Mrs. Jones tries on a guest’s fashionable dress to find out what it’s like to wear nice clothes, Bill reacts obtusely. It’s his indifference as much as her decision to sell the hotel to land-grabbers that pushes her to sue for divorce. The climax is a prolonged trial scene in which Bill becomes his own advocate. As in later folkish tales like Judge Priest (1934) and The Sun Shines Bright (1953), plot dynamics take a back seat to horseplay and quietly detailed scenes of character reaction and reflection. Some laughs are milked from the family dog wavering between husband and wife, the judge flirting with a flapper, and the dimwitted drinking buddy with his two pudgy children. But soon Bill is fingering his Civil War medal as he slowly confesses his faults as a husband, and we recognize what we’d learn to call a pure Fordian moment.

Those were the days when you could make a film about old people.

For more on Ford, visit Tag Gallagher’s generous and wide-ranging website. It includes a revised version of his critical biography on the Skipper, as well as articles on many other filmmakers. For more Cinema Ritrovato photos, go here. For Gabe Klinger‘s rapid-fire Bologna updates, try Mubi. And for remarks on non-Fordian entries in this abundant festival, check in with us again soon.

John Ford, silent man

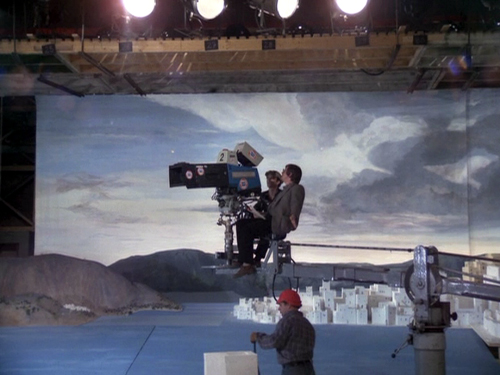

John Ford on the set of Air Mail (1932).

DB here:

This is the busiest installment of Cinema Ritrovato I can recall. We scarcely have time to sleep, let alone blog. The coordinators Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée have outdone themselves in offering something for everybody, from early films to postwar French and Italian rarities up through a tribute to Stanley Donen and special screenings of The Leopard and Metropolis. Our attention has been riveted by the 1910 programs and an extensive collection of films directed by Alberto Capellani, a little-known master of silent film.

One headliner is the early Ford series: all his surviving silents, plus a selection of rarely-seen talkies. The first one screened, The Black Watch (1929), concentrates on intrigue in the Khyber Pass during World War I. Captain King is assigned to India while the rest of his Scots regiment is sent to Europe. In India, King masterminds the defeat of the forces of Yasmani, a woman who has been taken as sort of a goddess by her followers. The central section, involving Yasmani’s passion for King and his betrayal of her, seems to me sketchy and rushed; Ford’s real interest, not surprisingly, is in the rites of comradeship among the Black Watch. Twenty-two of the film’s 91 minutes are taken up with the opening dinner celebrating the regiment, conducted while King gets his assignment. Since his mission is secret, he abandons his comrades and suffers their opprobrium. A bookended sequence at the close shows him returning to the Watch as, in the trenches of war, they hold another dinner, complete with ruffles and flourishes.

Some of the central portion was directed by Lumsden Hare, but it too has some striking moments, perhaps most memorably the display of Yasmani’s powers when she conjures up an eerie vision of the European battlefield in a glowing crystal ball. The war sequences have the dank Expressionist look that Murnau brought to Fox and that Ford exploited in Four Sons (1928). There are as well touching train-station farewells between brothers and between father and daughter, all of which seem very Fordian. Overall, Ford finds ways to avoid the multiple-camera shooting common to early talkies, often using offscreen dialogue during reaction shots.

Also fairly free of multicamera work was The Brat (1931). Like many talkies derived from a creaky Broadway play, it entices us with a “cinematic” curtain-opener. Cops (including the young Ward Bond) hustle perps into night court, all captured in a flurry of high and low angles, bursts of deep space, and swift tracking shots. Afterwards things slow down, enlivened by some social satire (the pretentious novelist writes with a quill pen), a few sight gags (an artist’s muscled model who discovers he’s been rendered in a faux-Cubist image) and an all-in grappling fight between a society dame and a girl from the other side of the tracks. According to Ford, the fight got its impact from the fact that the actresses couldn’t stand each other.

The first silent Fords were introduced by Joe McBride. “When the real West ended,” Joe remarked, “the cinematic West began.” Born soon after the closing of the frontier, Ford was fascinated by cowboys and Native Americans. Early filmmakers were to a surprising extent celebrating the stoic Indians uprooted and forced to give up their way of life, and this resonated with Ford. The elegiac quality we find in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and other late films, Joe suggested, was already there in the genre. Ford’s own first Westerns, thanks partly to the presence of Harry Carey, carry an air of resignation to history. Even the fragmentary sequences surviving from The Secret Man (1917), in which Harry must sacrifice his freedom to save a little girl, have a severe melancholy.

Hell Bent (1920) has long been famed for its flashy, unrepeatable shot: A carriage pulled by horses tumbles into a ravine; the camera tilts down to follow the crash; and then the horses, freed at the top, come hurtling back into the frame to pass the wreckage. Otherwise the film is consistently agreeable, suffused with Fordian camaraderie among drunks and respect between hero and villain. This last element is starkly dramatized when Harry and his adversary, having wounded each other in a gun duel, must crawl through the desert together.

On my first viewing, I didn’t see in Hell Bent the inventiveness and grace notes I admire so much in Ford’s first feature, Straight Shooting (1917). As we’ve mentioned before, this film shows a mastery of the classical Hollywood style that emerged in the late 1910s. It bears comparison with William S. Hart films of the period, high points of filmmaking craft. Late in the plot Ford give us a shootout with ever-tighter framings that could have come out of Leone.

Whether Ford invented this particular piece of cinematic rhetoric we can’t say; too many silent films are lost. But coming from a 23-year-old filmmaker in his first feature, this remains a remarkably assured use of the continuity editing system for 1917.

Ford’s debt to Griffith has often been noted, and in this movie it turns up in unexpected ways. At one point Joan tenderly puts away the plate her dead brother had used, as if to preserve it. Later, Ford recalls the gesture when the cabin is under siege and bullets blow apart other plates on the sideboard. But Ford has already quietly suggested an association between brother Ted and Cheyenne Harry; as Joan kisses the plate before putting it away, Ford cuts to Harry outside, and then back to Joan slipping the plate into a drawer. Using the then-current technique of a “ruminative cut”, the editing suggests that Joan may also be thinking of Harry, and he of her. The idea of Harry replacing Ted is made explicit at the end when Sims plaintively asks Harry, “You be my son.”

The Griffith influence is particularly acute in Straight Shooting’s climax, when the farmers are under siege in the Sims cabin. Horsemen gallop around the cabin as hired gunmen pepper it with bullets. Meanwhile, Cheyenne Harry has persuaded Black-Eyed Pete’s gang of outlaws to rescue the settlers, and Ford gives us a rousing passage of rapid crosscutting. It’s a canonical last-minute rescue, straight out of the climax of The Birth of a Nation (191t5).

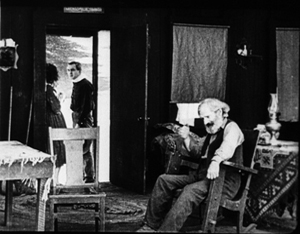

Or more particularly, I think, out of The Battle at Elderbush Gulch (1914). Griffith commonly staged interior scenes with doors at the left and right of the frame, letting actors play laterally. The strategy can be considered somewhat theatrical, in that we never see the “fourth wall” that would in reality enclose the characters.

But this leads to problems when you want to show your characters surrounded. In Elderbush Gulch, the settlers are besieged by encircling Indians. At one point, Griffith cuts from the exterior of the cabin to the interior, and to convey the sense of enclosure he has one of the settlers firing “through” the fourth wall, as if over the heads of the audience!

This is an awkward compromise, but at least give Griffith credit for grasping that his dollhouse playing area doesn’t fully render a realistic space. In Straight Shooting Ford provides a more three-dimensional rendering of interiors. Even though most scene in the Sims cabin lacks Griffith’s side walls, the set yields layers of depth, and the famous door in the back of the set opens on to the porch and the farm outside.

During the gunmen’s siege, we get a strong sense of enclosing space by virtue of the cuts of men firing from different angles. In addition, the cabin interior displays a little more angular depth.

But even Ford can’t escape compromises. We never see the space “behind us” in the Sims’ cabin, and as the farmers take up positions at windows, Ford shows us old Sims readying to fire by turning toward the camera and, like Griffith’s settler, aiming through the fourth wall.

The two shots of Sims in this posture go by fast, and they’re less noticeable because the siege hasn’t quite begun. Still, the anomaly indicates that in this setting Hollywood technique still doesn’t give the sense of a wraparound space that we get in the exterior scenes, like the shootout. A few years after Straight Shooting, American directors would master the ability to build up a four-walled interior through careful cutting. Those techniques would then be exploited for dramatic effect, as in Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925).

More to come, but now I must rush off to a morning of early film! If you’re hungry for more in the meantime, visit our category Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato for highlights of earlier years.

It takes all kinds

Kristin here—

How many directors are there whose bad reviews just make you more eager to see their new films? I’m not at Cannes and haven’t seen Jean-Luc Godard’s Film socialisme. But I’ve read some negative reviews, mainly those by Roger Ebert and Todd McCarthy. Now I’m really hoping that Film socialisme shows up at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year. (Please, Mr. Franey? I promise to blog about it.)

As you can tell from my writings, I’m no pointy-headed intellectual who won’t watch anything without subtitles. I love much of Godard’s work and have analyzed two films from early in what a lot of people see as his late, obscurantist period (Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie) in Breaking the Glass Armor). But I also love popular cinema. If I made a top-ten-films list for 1982, both Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior) and Passion (left and below) would be on it.

Of course, those are old films by most people’s standards. Godard’s films have gotten much more opaque since I wrote those essays. I wouldn’t dare to write about King Lear or Hélas pour moi. That’s partly because I don’t speak French, though a French friend of ours has assured us that that doesn’t help much. Here Godard thwarts the non-French-speaker further by not translating the dialogue. Variety‘s Jordan Mintzer describes the subtitles that appear in the film: “To add fuel to the fire, the English subtitles of “Film Socialism” do not perform their normal duties: Rather than translating the dialogue, they’re works of art in themselves, truncating or abstracting what’s spoken onscreen into the helmer’s infamous word assemblies (for example, “Do you want my opinion?” becomes “Aids Tools,” while a discussion about history and race is transformed into “German Jew Black”).” Mintzer’s review provides a long description of the film; he mentions how baffling it is but doesn’t offer any real value judgments on it. Like other reviews, though, it piques my interest in the film.

Since Godard has increasingly moved into video essays, I’ve not kept as close track of him. But I always look forward to seeing his occasional new features on the big screen. The man has a mysterious knack for making beautiful images out of the mundane. How could a shot of a distant airplane leaving a jet-trail across a blue sky be dramatic? Godard manages it in the first shot of Passion. (I won’t show a frame from that shot, since it depends on the passage of time for its effect.) His soundtracks are dense and playful. Every few years the man cobbles together an incomprehensible plot based on rather tired political ideas and turns out something so visually striking that it might as well be an experimental film. I’m willing to watch and listen hard without assuming that I’m obliged to strain to find a message. McCarthy comments, “More personally, I have become increasingly convinced that this is not a man whose views on anything do I want to take seriously. […]” Did we take his views all that seriously back when he was a Maoist? I didn’t, but La Chinoise is a terrific film.

That’s not my point, though. As Ebert’s and McCarthy’s reviews both mention there are devotees of Godard who will most likely enjoy and defend Film socialisme. Ebert: “I have not the slightest doubt it will all be explained by some of his defenders, or should I say disciples.” McCarthy says that Godard is one of an “ivory tower group whose work regularly turns up at festivals, is received with enthusiasm by the usual suspects and then is promptly ignored by everyone other than an easily identifiable inner circle of European and American acolytes.” (McCarthy’s review is entitled “Band of Insiders.”)

I’m not sure what’s wrong with being devoted to Godard, even to the point of defending films that may be obscure or even maddening. I personally haven’t enjoyed his more recent theatrical releases like Forever Mozart and Éloge pour l’amour as much as his earlier work, but they’re still better than most Hollywood, independent, and foreign art-house films. The man is pushing 80 and not likely to change, so live and let us acolytes live.

Not coming to a theater remotely near you

I’m not here to defend Godard—not yet, anyway. But on May 19, Roger posted an essay calling for more “Real Movies” to be made, essentially narratives based on psychologically intriguing characters in situations with which we can empathize. He doesn’t say so, but I suspect this idea was inspired in part by his reaction to Film socialisme. His examples of real movies are some of the films he’s enjoyed this year at Cannes. I haven’t seen those, either, but I’ve read enough of Roger’s writings and been to Ebertfest often enough to know he loves U. S. indie films like Frozen River and Goodbye Solo. Excellent films with fascinating characters, but they and most of the foreign-language films that get released in the U.S. play mostly at festivals and in art-houses, both of which tend to be confined to cities and college towns. I’m sure that such character-driven films would be more likely than Film socialisme to get booked into art-houses, but they wouldn’t wean Hollywood from its tentpole ways.

Even the films that play festivals and arouse great emotion and admiration in the audiences will seldom break through into the mainstream. There simply aren’t enough of those art-houses.

As with many of Roger’s posts, “A Campaign for Real Movies” has aroused comments from people complaining about the lack of an art-house within driving distance of where they live. Jeremy Chapman remarked:

But Roger, if they did that (“Real Movies”), then I’d return to the cinema. And those in charge of the movie industry have proven again and again that they don’t wish to see me there. They’d rather show regurgitated nonsense to people so desperate for some distraction from their lives that they’ll go even though they know that they’re watching rubbish.

If any of these films you mention play nearby, then I shall see them. But they won’t. Instead I’ll have the option of Avatar II or some remake of a movie that was quite good enough (or not) the first time it was made. I love the movies, but I’m so over the movie industry (at least in the US).

Talking to regulars at Ebertfest, one hears time and again that some of them journey across several states to have a quick, intense immersion in films that haven’t played near their homes. Similarly, many who post comments on Roger’s essays refer to having been limited to seeing indie and foreign films on DVDs or downloads from Netflix.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

I completely sympathize with that problem. Even with Sundance’s six-screen multiplex and the University of Wisconsin’s Cinematheque series and Wisconsin Film Festival, most of the movies David and I see at events like Vancouver or Hong Kong don’t play here. Sundance has to book pop films on some of its screens to allow them to bring art films to the others. Right now Iron Man 2 and Sex in the City 2 are playing there, alongside The Secret in Their Eyes and Letters to Juliet. If that’s what it takes to keep the place going, then so be it.

However much people decry the crassness of Hollywood—and there’s plenty of it to go around—or denounce audiences who only go to the latest CGI spectacle, the simple fact is that the market rules. Indeed, if there were a truly free market, we probably would see far fewer indie and foreign-language films. Film festivals are supported largely by sponsors, and the films they show are often wholly or partially subsidized by national governments. The festival circuit has long since become the primary market for a range of films that otherwise never reach audiences.

That may sound terrible to some, but consider the other arts. Some presses only publish books they hope will be best-sellers, while poetry and other specialist literature is relegated to small presses whose output doesn’t show up in Barnes & Noble. That’s very unlikely to change. Amazon and other online sales have been a shot in the arm for small presses, just as Netflix has made it far easier for people to see films they probably would not otherwise have access to. (Our plumber told me the other day that he had been watching a bunch of recent German films downloaded from Netflix. Well, that’s Madison, as we say; high educational level per capita. But most people have the same option, if they wish.)

Art-houses are scarce in small cities and towns, but such places are not likely to have opera houses either, or galleries with shows of major modern artists, or bookstores which offer 125,000 titles. (As I recall, that’s what Borders claimed to have when it first opened in Madison. Now they seem to be working on that many varieties of coffee.) Opera or ballet lovers are used to traveling to cities where they can see productions, and serious Wagner buffs aim to make the pilgrimage to Bayreuth at least once in their lives.

David and I are lucky. It’s vital to our work to keep up on world cinema, so now and then we travel to festivals and wallow in movies for a week or two. Quite a few civilians plan their vacations around such events, too. We’ve run into people in Vancouver who say they save up days off and take them during the festival. Naturally not everyone can do that, but not everybody can see the current Matisse exhibition in Chicago (closes June 20) or the recent lauded production of Shostakovich’s eccentric opera The Nose at the Metropolitan. I really wish I had seen The Nose, but I don’t really expect the production to play the Overture Center here.

To some people, film festivals might sound like rare events that inevitably take place far away, like the south of France. Those are the festivals that lure in the stars and get widespread coverage. But there are thousands of lesser-known festivals around the world, dedicated to every genre and length and nationality of cinema. For those who like to see old movies on the big screen, Italy offers two such festivals, Le Giornate del Cinema Muto (silent cinema) and Il Cinema Ritrovato (restored prints and retrospectives from nearly the entire span of cinema history; this year’s schedule should be posted soon). Last month in Los Angeles, Turner Classic Movies successfully launched its own festival of, yes, the classics. Ebertfest itself began with the laudable goal of bringing undeservedly overlooked films to small-city audiences, specifically Urbana-Champaign, Illinois. It was and is a great idea, and it would be wonderful if more towns in “fly-over country” had such festivals.

The films we don’t see

Usually when someone calls for more support of independent or foreign films, there seems to be an implicit assumption that all those films are deserving of support, invariably more so than Hollywood crowd-pleasers. If a filmmaker wants to make a film, he or she should be able to, right? But proportionately, there must be as many bad indie films as bad Hollywood films. Maybe more, because there are always lots of first-time filmmakers willing to max out their credit cards or put pressure on friends and relatives to “invest” in their project. There’s also far less of a barrier to entry, especially in the age of DYI technology.

True, the indie films we see seem better. By the time most of us see an indie film in an art cinema, it has been through a pitiless winnowing process. Sundance and other festivals reject all but a relatively small number of submitted films. A small number of those get picked up by a significant distributor. A small number of those are successful enough in the New York and LA markets to get booked into the art-house circuit and reach places like Madison. Yes, some worthy films get far less exposure than they deserve. But many more films that would give indies a bad name mercifully get relegated to direct-to-DVD, late-night cable, or worse. On the other hand, most mainstream films, no matter how dire their quality, get released to theaters. Their budgets are just too big to allow their producers to quietly slip them into the vault and forget about them.

The winnowing process for art-house fare happens on an international level as well. A prestige festival like Cannes dictates that a film they show cannot have had a festival screening or theatrical release outside its country of origin. Programmers for other festivals come to Cannes and cherry-pick the films they like for their own festivals. Toronto has come to serve a similar purpose, especially for North American festivals. Some films fall by the wayside, but the good ones attract a lot of programmers. These films show up at just about every festival. By the way, that kind of saturation booking of the year’s art-cinema favorites at many festivals means that the distributors are more and more often supplying digital copies of films to the second-tier events. Going to festivals is no longer a guarantee that you’ll be seeing a 35mm print projected in optimal conditions. At the 2009 Vancouver festival, I watched Elia Suleiman’s The Time that Remains twice, because it was a good 35mm print and I suspected that I’d never have another chance to see it that way.

To each film its proper venue

There’s no way that every deserving film will reach everyone who might admire it. Condemning the crowds who frequent the blockbusters won’t help open new screens to offbeat fare. If someone loves Avatar, as long as they keep their cell phones off, refrain from talking, and don’t rustle their candy-wrappers too loudly, as far I’m concerned they can go on believing that this is the best the cinema has to offer. Simply showing these audiences a film like A Serious Man, say, or Precious isn’t going to change their minds about what sort of cinema they prefer. To break through decades of viewing habits, such people would need to learn new ones, which takes time and effort. People’s tastes can be educated, but the odds are usually against it actually happening.

Finally, in defending art cinema against mainstream multiplex fare, commentators often cite Avatar or Transformers or the latest example of Hollywood’s venality and audience’s herd-like movie-going patterns. Yet every year major studio films come out that get four stars or thumbs up or green tomatoes. Last year, we had Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs, Up, Inglourious Basterds, Coraline, and a few others that were well worth the price of a ticket. All of them did fairly well at the box-office while playing in multiplexes. Some readers might substitute other titles for the ones I’ve mentioned, but to deny that Hollywood is bringing us anything worth watching seems blinkered. As I said in 1999 at the end of Storytelling in the New Hollywood, where I criticized some aspects of recent filmmaking practices, “In recent years, more than ever, we need good cinema wherever we find it, and Hollywood continues to be one of its main sources.”

Ultimately my point is that in this stage in cinema history, international filmmaking has settled into a defined group of levels or modes. Hollywood gives us multiplex blockbusters and more modest genre items like horror films and comedies. They bring us the animated features that are among the gems of any year’s releases. Then there are the independent films and the foreign-language ones which together form festival/art-house fare. There are also the experimental films, which play in festivals and museums. The institutions that show all these sorts of films have similarly gelled into specialized kinds of venues suited to each type. A broad range of films is still being made. There are some few really good films in each category made each year. The question is not how many worthy films are getting made but how much trouble it takes to see them.

None of the current types of institutions is likely to change on its own. What will make a difference is the growing possibilities of distribution via the internet. Filmmakers who get turned down by film festivals can produce, promote, and sell their movies via DVD or downloads. True, recouping expenses that way is so far a dubious proposition; it’s probably easier to get into Sundance than to do that. As I mentioned, digital projection may make some festivals less attractive to die-hard film-on-film cinephiles. On the other hand, in some towns opera-lovers who can’t get to the big city now can see a digital broadcast of a major production each week at their local multiplex. Not as exciting as a trip to the city to see it live, but a lot cheaper and hence within the reach of a lot more people’s means. All sorts of other digital developments will change movie viewing in ways we can’t yet imagine.

_______________

Jim Emerson has been covering the Film socialisme battle of the reviews on Scanners, with quotes and links to the ones I mentioned and more. He also demonstrates that people have been baffled by Godard since Breathless, with reviews that “are, incredibly, the same ones he’s been getting his entire career — based in part on assumptions that Godard means to communicate something but is either too damned perverse or inept to do so. Instead, the guy keeps making making these crazy, confounded, chopped-up, mixed-up, indecipherable movies! Possibly just to torture us.” He offers as evidence quotes from New York Times reviews over the decades.

Eric Kohn gauges the controversy and offers a tentative defense of the film on indieWIRE.

For our reports on various festivals, see the categories on the right. We discuss Godard’s compositions, late and early, here and his cutting here.

DER GOLEM: Revisiting a classic

Kristin here:

In 2009, Il Giornate del Cinema Muto, the silent-film festival held each year in Pordenone, Italy, launched a new series. “Il canone rivisitato/The Canon Revisited” addressed the fact that many rare and often obscure silent films are made available through restoration each year, and yet many young enthusiasts who have started attending the festival have seldom had the chance to see the classics on the big screen with musical accompaniment. The opening group of films proved highly successful, and “Il canone rivisitato 2” will be presented this year, when Il Giornate will run October 2 to 9.

Part of the point of the series is to have historians re-evaluate these classics and examine how well they live up to their status as part of the film canon. Last year I contributed a program note on Paul Wegener and Karl Boese’s 1920 German Expressionist film Der Golem. This year I’ve written about Danish director Benjamin Christensen’s 1916 thriller Hævnens Nat (Night of Revenge, released in the U.S. in 1917 as Blind Justice), which will be shown this year, and rightly so.

When I went back and reread my Golem notes to remind myself what sort of coverage is needed, I decided that the text I wrote then might be of wider interest to those who weren’t at the festival last year. Thanks to Paolo Cherchi Usai, one of the festival’s founders and organizers, for permission to revise my brief essay as a blog entry. I’ve changed it minimally and taken the opportunity to add illustrations. Here’s what I said at the time:

Der Golem is a classic film—doubly so.

First, it has long nestled comfortably within the list of titles that make up the German Expressionist movement of the 1920s. Teachers of survey history courses are more likely to show Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (which premiered in early 1920) but a serious enthusiast will make it a point to see Der Golem (which appeared later the same year) as well.

From the start, reviewers recognized Der Golem as Expressionist. In 1921 the New York Times’ critic wrote, “Resembling somewhat the curious constructions of THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, the settings may be called expressionistic, but to the common man they are best described as expressive, for it is their eloquence that characterizes them” (George Pratt’s Spellbound in Darkness, p. 362). In 1930, Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now, the most ambitious world history of cinema in English to date, appeared. Highly influential in establishing the canon of classics, Rotha adored Weimar cinema, including Der Golem.

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art obtained a large number of notable European films. The core collection of the young archive contained such prestigious titles as Caligari, Battleship Potemkin, Metropolis, and Der Golem. These films soon became part of the museum’s 35mm and 16mm circulating programs. With MOMA’s sanction as historically important classics, they remained the most widely accessible older films available to researchers and students alike for many decades.

There is, however, a second, largely separate audience: monster-movie fans. Starting in the 1950s, German Expressionist films were promoted as horror fare by Forrest J. Ackerman in his magazine Famous Monsters of Filmland. In 1967 Carlos Clarens included Der Golem in his An Illustrated History of the Horror Film. Really dedicated horror devotees pride themselves on their expertise across a wide variety of films, including foreign and silent ones. Der Golem became a certified horror classic.

In the 1950s and 1960s, companies offering public-domain 8mm and 16mm copies for sale enabled both film-studies departments and movie buffs to start their own film libraries. Ultimately home video made previously rare silent classics easily obtainable—including a restored Golem from the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau-Stiftung, with new tinting and a musical score, on DVD. Such a presentation reconfirms the film’s status as a classic.

But what sort of classic is it? An undying masterpiece that one must see immediately? A film one should definitely watch someday if the chance arises? On the occasion of Der Golem being presented on the big screen with live musical accompaniment, we have a chance to specify what distinguishes it from its fellow exemplars of Expressionism.

I suspect that horror-film fans won’t feel that a reevaluation is necessary. Der Golem is a forerunner of Frankenstein and hence an important early contribution to the genre. It’s a striking film to look at and obscure enough to impress one’s friends during a late-night program in the home theater.

But for film historians returning to Der Golem in the early twenty-first century, after nearly ninety years of taking it for granted, what is there to say?

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

Some would deny that Der Golem is truly Expressionistic. If one has a very narrow view of the style, insisting that only films with flat, jagged, Caligari-style sets qualify for membership in the movement, then Der Golem doesn’t pass muster. Neither do Nosferatu, Die Nibelungen, Waxworks, and a lot of other films typically put into the Expressionist category.

It’s a subject susceptible to endless debate. To avoid that, it’s helpful to accept historian Jean Mitry’s simple, useful distinction between graphic expressionism, with flat, jagged sets, and plastic expressionism, with a more volumetric, architectural stylization. If Caligari introduced us to graphic Expressionism in 1920, Der Golem did the same for plastic Expressionism later that year.

For me, seeing Der Golem again doesn’t much affect its status as an historically important component of the German Expressionist movement. It’s not the most likeable or entertaining of the group. Caligari has more suspense and daring and black humor. Die Nibelungen has a stately blend of ornamental richness with a modernist austerity of overall composition, as well as a narrative that sinks gradually into nihilism in a peculiarly Weimarian way.

Moreover, Der Golem’s narrative has its problems. None of the characters is particularly sympathetic. Petty deceits and jealousies ultimately are what allow the Golem to run amok. The narrative momentum built up in the first half of  the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

the film is inexplicably vitiated for a stretch. Initially the emperor’s threat to expel Prague’s Jews from the ghetto drives Rabbi Löw to his dangerous scheme of creating the Golem to save his people. Yet after the creation scene, the dramatic highpoint that ends the first half, we see the magically animated statue chopping wood and performing other household tasks that make his presence seem almost inconsequential. The imperial threat has to be revved up again to get the Golem-as-savior plot going again.

But putting aside Der Golem’s minor weaknesses, it has marvelous moments that summon up what cinematic Expressionism could be: the opening shot, which instantly signals the film’s style (below); the black, jagged hinges that meander crazily across the door of the room where Löw sculpts the Golem; the juxtaposition of the Golem with a Christian statue as he stomps across the crooked little bridge returning from the palace (at top).

Hans Poelzig was perhaps the greatest architect to design Expressionist film sets. He designed only three films, and Der  Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Golem is the most important of them. Once the monster has been created, Poelzig visually equates the lumpy, writhing towers and walls of the ghetto and the clay from which the Golem is fashioned. The sense that sets and actors’ performances constitute a formal, even material whole became one of the basic tactics of Expressionism in cinema.

Speaking of performances: A lot of the actors in German Expressionist films were movie or stage stars who didn’t specialize in Expressionism. There were, however, occasional roles that preserve the techniques the great actors of the Expressionist theater. There’s Fritz Kortner in Hintertreppe and Schatten. There’s Ernst Deutsch, who acted in only two Expressionist films, as the protagonist in the stylistically radical Von morgens bis Mitternacht (out this month on DVD) and as the rabbi’s assistant in Der Golem.

Just watching his eyes and brows during his scenes in this film conveys something of the experimental edge that Expressionism had when it was fresh—before its films had become canonized classics.