Archive for the 'Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato' Category

Your tax dollars at work for Michael Bay

Kristin here–

Back in July, when I was watching films at Il Cinema Ritrovato in Bologna, I managed to catch several of the films in the Frank Capra retrospective. Two of them, Dirigible (above and left) and Submarine, were surprisingly spectacular, given that at the time Columbia was still a relatively minor studio. It wasn’t known for high-budget items. How had Capra managed such lavish-looking films?

One clue lies in the title at the beginning of Dirigible: “Dedicated to the United States Navy without whose cooperation the production of this picture would not have been possible.” Clearly the film’s second sequence (from which both frames here were taken) was shot at an actual air field with real planes and dirigibles. Many shots in the scene were taken during what seems to have been a public air show.

One clue lies in the title at the beginning of Dirigible: “Dedicated to the United States Navy without whose cooperation the production of this picture would not have been possible.” Clearly the film’s second sequence (from which both frames here were taken) was shot at an actual air field with real planes and dirigibles. Many shots in the scene were taken during what seems to have been a public air show.

I recalled that when I was growing up, every now and then a movie I saw had a similar acknowledgement. Jimmy Stewart and other stalwart stars played government employees of various sorts, with pictures of impressive buildings in Washington and superimposed titles thanking this agency or that for its aid.

It also reminded me of The Lord of the Rings. One sequence in The Return of the King, the battle before the Black Gates, was shot in an old military practice range of the New Zealand army (right and below). The country, with its lush forests and stunning mountains, is short on desolate plains. The practice range was the only suitably Mordor-like landscape that could be found.

Not only did the army clear the field of unexploded ordnance, but it supplied soldiers to serve as extras by playing the Gondorian troops. The supplement on the extended-version DVD, “Cameras in Middle-earth,” shows these troops, as well as the officers who gave them orders. Apparently the soldiers were far more capable than regular extras of marching in straight lines and less willing to merely mime fighting during the battle.

Not only did the army clear the field of unexploded ordnance, but it supplied soldiers to serve as extras by playing the Gondorian troops. The supplement on the extended-version DVD, “Cameras in Middle-earth,” shows these troops, as well as the officers who gave them orders. Apparently the soldiers were far more capable than regular extras of marching in straight lines and less willing to merely mime fighting during the battle.

All this got me to wondering how much free or cheap labor and mise-en-scene movies have received from the military over the years. Coincidentally, when I got home in July, the stack of magazines awaiting me included an issue of Variety with the headline “Tanks a Lot, Uncle Sam,” on this very subject. In the article author Peter Debruge explains a lot about the nuts and bolts of how the military’s contributions work. (As often happens, Variety opted for a more dignified title for the same article online: “Film biz, military unite for mutual gain.”)

The occasion was the release of Transformers : Revenge of the Fallen. Lt. Col. Greg Bishop, an Iraqi vet appointed last year to handle the Army’s interface with Hollywood, says of it, “This is probably the largest joint-military movie ever made.” Indeed, Transformers enjoyed the assistance of four of the country’s five military branches, with the Coast Guard being the only exception. That’s unusual, as Bishop points out. Black Hawk Down mainly called upon the Army, Top Gun upon the Navy, and Iron Man upon the Air Force.

Debruge doesn’t offer a lot of historical background, but he does mention that the Vietnam War led to a period of anti-military films. Naturally the armed forces didn’t supply aid to films excoriating them. In recent decades relations have become chummier.

What are the typical financial arrangements? According to the article,

Hollywood has every incentive to seek the military’s blessing. A film like ‘Transformers’ gets much of the access, expertise and equipment for a fraction of what it would cost to arrange through private sources, with the production on the hook only for those expenses the government encounters as a direct consequence of supporting the film (such as transporting all that megabucks equipment to the set from the nearest military base). But the production pays no location fees for shooting on military property and no salaries to the service men and women who participate in the filming, in front of or behind the cameras.

In some cases, military exercises are arranged that can be incorporated into the filming. Capt. Bryon McGarry, the deputy director of the Air Force’s PR office, is quoted concerning a day when Transformers was shooting “at White Sands when a formation of six F-16s popped flares over the set, simulating a low-level, air-to-ground attack. ‘The flyover was very much the type of training the Air National Guard does every day. Only that day, Michael Bay and his cameras had a front-row seat to the air power show,’ he says.”

This sort of military assistance isn’t available to films that shoot entirely overseas, such as Saving Private Ryan and HBO’s Band of Brothers. Hence films like Transformers and Iron Man arrange to shoot some key sequences in the American West, where deserts and mountains can convincingly double for places like the Middle East.

Even in this day of elaborate CGI special effects, many directors prefer the real thing. For one thing, it often looks more realistic, and for another, CGI is really expensive.

Naturally the military doesn’t do all this for nothing. They want influence over the way the Armed Forces are depicted. Spielberg’s War of the Worlds had military assistance. The Pentagon’s film laiason, Phil Strub, says, “The big battle scene at the end was going to be different. We just wanted the case made that the Marines understood that they were not going to prevail, but they were nobly sacrificing so the civilians in that valley could escape.”

Naturally the military doesn’t do all this for nothing. They want influence over the way the Armed Forces are depicted. Spielberg’s War of the Worlds had military assistance. The Pentagon’s film laiason, Phil Strub, says, “The big battle scene at the end was going to be different. We just wanted the case made that the Marines understood that they were not going to prevail, but they were nobly sacrificing so the civilians in that valley could escape.”

Strub also decries “the enduring stereotype of the loner hero who must succeed by disobeying orders, going outside the rules by being stupid.” As Debruge points out, “By contrast, the ‘Transformers’ sequel embodies the military philosophy that teamwork is essential to success.”

The positive depiction of the military also might attract young people to enlist—and give enemies an impression of America’s overwhelming might. McGarry says, “Recruiting and deterrents are secondary goals, but they’re certainly there.”

The idea that Hollywood often gets in bed with the military won’t come as a surprise to anyone. (For a book emphasizing this aspect of the military’s involvement in filmmaking in the U.S., see David L. Robb’s Operation Hollywood: How the Pentagon Shapes and Censors the Movies.) But the extent to which even the biggest—or maybe that should be especially the biggest—Hollywood films boost their budgets in a big way is less obvious. From the standpoint of the business history of Hollywood, it’s fascinating and deserves a closer look.

The Bologna beat goes on

Guy Borlée, Festival Coordinator for Cinema Ritrovato, in a pas de deux with Moira Shearer.

DB here:

Like most film festivals, Cinema Ritrovato is many festivals. There’s so much on offer you can carve out your own mini-fests. You may meet a friend for lunch and learn that you two have seen none of the same movies. So here are some titles from my sampled version of Ritrovato.

1909 and a little later

Le Trust (Feuillade, 1911).

As Kristin pointed out in our last entry, we spent a lot of time in the 100 Years Ago thread. Things were definitely changing on screens in 1909. True, you still had your costume picture with suspiciously insubstantial walls and props, your gimmicky special-effects comedies (e.g., The Electric Policeman), and your chase films with people falling over and getting up and running on, endlessly.

But you also had powerful movies like Capellani’s L’Assommoir, discussed by Kristin, and charming ones like Charles Kent’s Vitagraph Midsummer Night’s Dream. There were crime films like Tell Tale Blotter and An Attempt to Smash a Bank, with its peculiar slow reverse tracking shots linking the lobby and the banker’s office. There was Cowboy Millionaire, which presents the always-edifying spectacle of a buckaroo bringing his uncouth pals to the big city. There were wonderful Film d’Art items, not least Le Retour d’Ulysse, which had the most rapid editing pace of any 1909 film I clocked. There was even a lifelong romance told through the fate of two pairs of shoes (Roman d’une bottine et d’un escarpin).

Louis Feuillade was one of the finest directors of the 1910s, but most of his earlier work that I’ve seen doesn’t suggest his mature storytelling skills. Of the 1909 Feuillades on display in Bologna, the two I found most intriguing were La Possession de l’enfant, about a divorced wife who kidnaps and raises her child in poverty, and La Bouée, a touching tale about a fisherman’s family about to lose everything. But the cherry on the sundae for me was a pristine print of a 1911 Feuillade, part of Eric de Kuyper’s program of films about financial crises. My man Louis did not fail me.

In Le Trust, a businessman indulges in a bit of corporate espionage. He hires a detective (the sinister René Navarre) to kidnap an inventor and squeeze a secret formula out of him. The detective resorts to some unusual methods, such as hiring an actor to dress in drag and impersonate a rival’s wife. The inventor is kidnapped but outwits his captors with a trick that could have come straight out of Les Vampires. The plot’s outrageous surprises are played straight and brisk, and we can see Feuillade moving toward the compact, inventive staging of Fantomas and Tih-Minh. How could Le Trust not be my favorite movie of the week?

Tsars, Commissars, and Jews

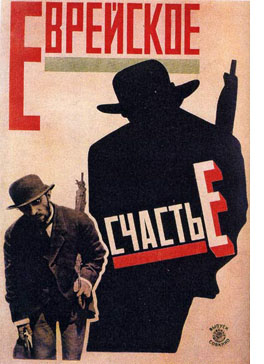

Given my fondness for Russian and Soviet film, Kinojudaica was a thread I followed fairly closely. This imaginative program, drawn from a larger package assembled by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, ran from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Given my fondness for Russian and Soviet film, Kinojudaica was a thread I followed fairly closely. This imaginative program, drawn from a larger package assembled by the Cinémathèque de Toulouse, ran from the 1910s to the early 1930s.

Véra Tcheberiak (1917) is probably more important for its subject matter than its fairly simple technique. The two-reel film was the third to treat a famous case of anti-semitic hysteria under the Tsar. In 1913, a Jew named Beilis was charged with ritual murder of a Christian child, and it became Russia’s Dreyfus affair.

More elegantly directed was Evgenii Bauer’s worldly, somewhat cynical Leon Drey (1915) which retains its fascination. (I wrote about its staging in an earlier entry.) But its intertitles still need to be restored.

Two later films were strongly marked by Soviet montage influence. In The Five Brides (Piat Nevest, 1929-1930), a shtetl is threatened with a pogrom by a gang of bandits. The band will spare the citizens if five virgins can be offered to their leaders. Director Aleksandr Soloviev accentuates this dramatic situation with every trick in the montage playbook: fast cutting, low angles, handheld shots, dynamic graphic conflict, and even explosions and bursting waves as Red partisans ride to the rescue. The final moments are missing, but there is plenty to savor, including an emotionally complex scene in which the elders decide to sacrifice their five virgins and suffocate a young man who is trying to stop them. The film was revised for Russian release, but we saw the original Ukrainian version.

No less engaging, though a little more formulaic, was Remember Their Faces (Zapomnite ikh litsa, 1931). A young Jewish worker devises a machine to speed the work of a tannery, but his efforts are blocked by saboteurs and anti-Semites. In a slap to the New Economic Policy, the chief villain is a private entrepreneur who wants to make the tannery uncompetitive. The scenes in which Beitchik is casually bullied by young thugs are quite strong. The final moments, when the bullies won’t even let Beitchik leave town unmolested, present the stirring image of the Komsomol youths marching to rescue him. Such support did not materialize behind the scenes: the film encountered censorship at every stage and was given a modest release.

Despite a 1927 Party directive ordering films treating anti-Semitism as a threat to socialism, both The Five Brides and Remember Their Faces encountered obstacles at every turn, largely on the grounds that the Party was given too small or too passive a role. In a fine book accompanying the series, Valérie Pozner supplies details of how the films were censored and suppressed.

Capra, company man

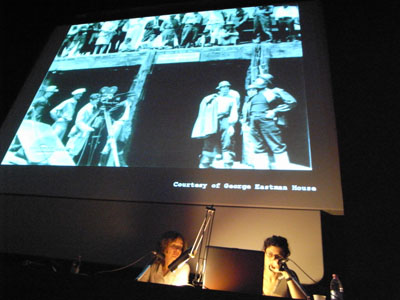

Donald Sosin gives us Scott Joplin’s “Wall Street Rag” (1909), uncannily appropriate today.

One of the highlights of this year’s Ritrovato was the Capra series, featuring his surviving silent work and several early sound pictures. We were also lucky to have Joe McBride, professor, critic, and UW alum, there to introduce many sessions.

I didn’t attend the talkies, having seen the batch except Rain or Shine (1930), but several of the silents grabbed my attention. Most seemed to be attempts by Columbia to hitch a ride on the bigger studios’ successes.

The Way of the Strong (1928) is a post-Underworld exercise in hoodlum redemption, graced by vigorous action, swift cutting (4.3 sec ASL by my count), and nice juggling of recurring props (mirrors, pistol barrels, a book devoted to great lovers). And the plug-ugly hero is truly ugly, none of your Hollywood fake-ugliness; a face only a blind girl could love. Submarine (1929) is a take on the What Price Glory plots analyzed by Lea Jacobs in her recent book. Two amiable sides of beef brawl and drink their way through navy life until a woman comes between them. The sexual rivalry is compelling, and the suspense during a stifling undersea rescue is admirably sustained. The Younger Generation (1929) owes something to the back-to-your-roots impulse of The Jazz Singer. Based on a Fannie Hurst story, it tells of a Jewish family that rises into society because of the son’s business acumen; in the process, class snobbery makes them increasingly unhappy.

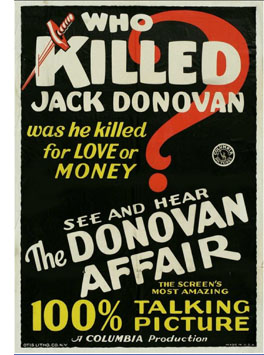

I leave aside the silent version of Rain or Shine, which I found underwhelming, so as to focus on the most curious thing I saw at the festival. The Donovan Affair is a Philovanceish murder mystery from a play by the ubiquitous Owen Davis. It was released in April 1929, and it isn’t particularly good. But it nags me.

I leave aside the silent version of Rain or Shine, which I found underwhelming, so as to focus on the most curious thing I saw at the festival. The Donovan Affair is a Philovanceish murder mystery from a play by the ubiquitous Owen Davis. It was released in April 1929, and it isn’t particularly good. But it nags me.

The movie was made in both silent and sound versions. Our print was silent, but it had no intertitles. At first blush it seemed to be the sound version without its track, sort of a 000% talking picture. The print’s average shot length is 9.3 seconds—too long for most late silents, but typical of some early talkies. Yet this did not look like any 1929 American talkie I have seen.

It had silent-film lighting, some huge lip-sync close-ups, and very smooth cutting. Except for a couple of moments, it lacked the jerky reframings, the long-lens imagery, and multiple-camera coverage typical of shooting from booths, the common practice of early talkies (and the talking sequences of The Younger Generation). Capra’s setups sat well inside the action, as was the case in 1920s silents and as would be the case in single-camera sound films a few years later.

Crazy as it sounds, I had to wonder if we were seeing a copy of the silent version made before titles were inserted! This is very unlikely. But if this was indeed an early talkie version, Capra was able to shoot sound with a fluidity that directors at bigger firms didn’t display—and in a rented studio at that, if the AFI Catalogue is to be believed. On the road and away from my research base, I can’t investigate further, but if you know more about the Donovan Affair affair, feel free to correspond and I’ll add postscripts.

Whatever the provenance of that Library of Congress print, the other silent/ early sound Capras have been admirably buffed by Sony’s Grover Crisp and Rita Belda (another Wisconsinite). The prints’ sparkle and sheen prove that even a minor-league studio (which Columbia was then) could turn out gorgeous imagery, thanks in no small part to cinematographers like Joseph Walker and Ted Tetzlaff.

Miscellany

The Lewinsky Dog surveys the climactic battle in Karadjordje (1911).

Be Patient! Department: Anke Wilkening, who was among those announcing the discovery of a new Metropolis print last year, gave us an update on the restoration process. The archivists are nearly done integrating the Argentine footage into the whole. Next comes the cleanup phase—awkward because the original Argentine print was heavily scratched and what we have is a 16mm copy and cropped for sound at that.

So far, the restored footage is clearly making secondary characters like Josaphat and the “Thin One” more prominent. But even the Argentine print is lacking things known to us, as three clips illustrated. Getting everything in some order will take time. Anke promises another report next year.

Box sets routinely attract attention at Bologna’s annual DVD awards, and this year things went according to form. The top prize went to Joris Ivens, Wereldcineast, a vast assembly of rare work by the Dutch filmmaker. Another generous package, Flicker Alley’s Douglas Fairbanks set, won best silent-film box set. (We have an entry on it.) Two more big collections, GPO Film Unit Collection vol. 2 (BFI) and Treasures from American Archives IV (Film Foundation) triumphed in the Sound Film and Avant-Garde categories.

Other winners: the two Vampyr releases (Eureka and Criterion) and Berlin, Symphony of a Big City (Munich Filmmuseum) for their rich bonus materials; Vittorio De Seta’s documentary collection Il Mondo Perduto (Feltrinelli Real) and two studies of Pasolini’s La Rabbia (Raro) in the Rediscovery category. Cinema Ritrovato wisely acknowledges that DVD producers are contributing powerfully to research into film history and are making rarities available to viewers who live far from festivals, archives, and cinematheques.

Not heralded—in fact, just sitting on the counter at the ticket booth—were still other DVDs, this time from Serbia. Sharp-eyed Olaf Müller pointed them out to me, and I’m grateful he did. Two volumes from the “Film Pioneers” series include a set of newsreels and, happily, the 1943 Innocence Unprotected (which Makavejev “decorated” in his revised version of 1968). A third disc consists of Karadjordje; or, Life and Deeds of the Immortal Duke Karadjordie (1911). This is the first Serbian and Balkan feature, and is thus, as the box text indicates, “one of a kind.” Same goes for Cinema Ritrovato itself.

Gian Luca Farinelli and Peter von Bagh, two more we have to thank for a great festival.

Just in time for Bologna, the historical journal 1895 has published a splendid special number on Le Film d’Art, ed. Alain Carou and Béatrice le Pastre. Feuillade’s Le Trust is available on the Gaumont early years DVD set and will soon be released on a Kino set drawn generously from the Gaumont collection. Keep your eyes open for early Capra features on Turner Classic Movies; several have run there recently.

Back in Bologna

The newly restored version of The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly on the Piazza Maggiore.

Kristin here-

This year, the main complaint about Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival held by the Cineteca Bologna, is that there’s too much to see. With three venues playing films against each other, plus the 10 pm screenings each evening in the Piazza Maggiore, there’s no way to see everything. Some people complain that the conflicts are becoming worse-but I remember these same complaints about the over-abundance of films coming in previous years as well. Yes, it’s frustrating at times, but being offered more films than one can watch is a problem a lot of people would love to have. Basically one either chooses a couple of threads to follow through or just goes to whatever appeals in any given time slot.

According to the 2009 festival’s newsletter, there were 810 attendees, including 557 from outside Italy.

This year there have been several main focuses: a retrospective of Frank Capra’s silent and early sound films; a portion of the Cinémathèque de Toulouse’s program of Jewish-themed Russian and Soviet cinema from the 1910s to the late 1940s; a selection of color films from the early years of the twentieth century to the 1960s; a survey of the work of Vittorio Cottafavi; the annual “100 years” program, this time from 1909; the sea films of Jean Epstein; the silent Maciste films; and many other items.

Even between the two of us, we could not take in nearly all of the riches on offer, so here’s some of what I managed to see, with David’s report to follow.

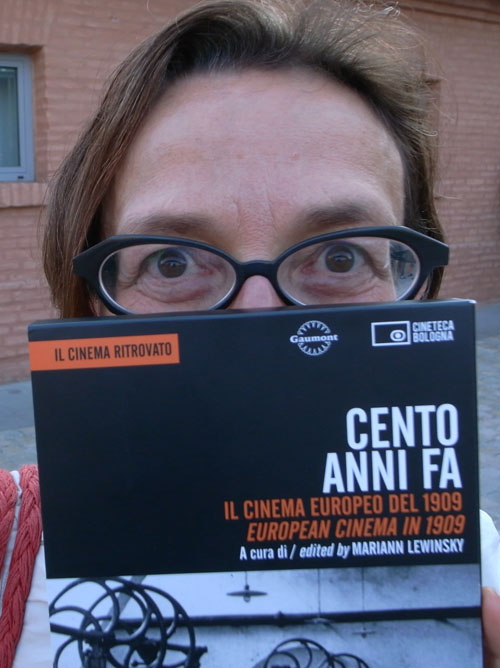

An annual hundredth birthday

Each year the festival has a thread of programs of films from one hundred years earlier. This tradition started in 2003, when Tom Gunning was asked to put together groups of films from 1903. Thereafter Mariann Lewinsky took over as programmer for these threads. In recent years, her choices have been supplemented by small groups of films chosen by individual national film archives. This year Tom programmed the 1909 Griffiths and a group of other U. S. titles.

Maybe it’s just my impression, but the hundred-year packages seem to gain in prominence and popularity each year. Presumably in response to such popularity, the festival has just released a DVD with a selection of 22 shorts from this year’s 1909 program: Cento anni fa: Il cinema Europeo del 1909/European cinema in 1909 (running two hours and twenty minutes and presented below by Mariann). It contains only about a fifth of the roughly 100 films screened, but many of the others are available in online archives. DVDs of previous years’ programs are in the works, with 1907 soon to come. The DVD and other publications of the festival are available here.

I managed to see most of the 1909 programs but obviously can mention only a sampling. Undoubtedly the highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

highlight for me and others I talked to was Albert Capellani’s L’Assommoir, notable for its skillful and intricate staging and splendid performances. It looked more like a film from 1912 or 1913. During the comedy, Un chien jaloux (a Gaumont one-reeler by an unknown director, left), pianist Donald Sosin had the audience in stitches by providing barks, whines, and growls as appropriate. (It’s included on the DVD, alas, without the sound effects.)

French director Alfred Machin contributed two excellent dramatic films, both involving windmills: Le Moulin maudit (also on the DVD) and, in the program of early color films, L’Ame des moulins. Comedy stars were represented by two Cretinetti films and a strange Max Linder film in which he becomes Amoreux de la femme à barbe (“Infatuated with the Bearded Lady”).

There were a great many documentaries giving glimpses into the world of 1909. Airplanes were much in  evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

evidence, as were detailed depictions of industries in colonized countries. Mariann confessed herself to be fascinated by the random, unplanned events that intrude into both non-fiction and fiction films of this early period-particularly those shot in the street. As usual with early films, passers-by frequently come to a standstill and gawk at the camera. As she pointed out, the frequent intrusion of dogs into the frame reflected the reality of the time, when numerous homeless animals inhabited cities. We all became very aware of these animals, which David dubbed “Lewinsky dogs.” At the right, a little one that half-enters the end of one shot of a typical chase film, Les tribulations d’un charcutier (director unknown; also on the DVD).

Mariann watched a great number of 1909 films in order to make her selection. Her experience convinced her of what many of us feel, that this was a turning point for the development of film art, though perhaps not as dramatic a one as 1913. Apart from L’Assommoir, Griffith’s The Country Doctor could be pointed to as evidence that the year saw films of a greater complexity and beauty than had previously been released. Griffith may no longer be quite the lone giant of the pre-1920 era that film historians have portrayed. Still, there are touches in The Country Doctor that no other director could have conceived, such as the early shot of the central family strolling through a field of tall grass that hides everything except the doctor’s top hat floating above the stalks.

Reaching 1909 raises the question as to how long these 100-year anniversary programs can continue and what form they should take. With fiction films getting longer in years to come, particularly in Europe, there emerges a problem of including enough of them to give a sense of a single year without having the programs expand even more. Perhaps non-fiction films will figure as an increasing proportion of this thread-with more Lewinsky dogs inadvertently captured for posterity.

A garland of color films

Two programs of early color films demonstrated the various processes: hand-coloring with stencils, tinting, toning, and attempts at photographic color. The only really successful of the latter were two 1912 shorts using the Gaumont system, which provided images in sharp, reasonably true color.

I caught only a few of the features in the color thread. Victor Schertzinger’s Redskin (1929), in two-strip Technicolor, was a beautiful print. Despite its implausibly happy ending, this story was a sophisticated look not only at racial tensions between whites and Indians but also at equally divisive tensions among Indian tribes. Like the other occasional films of the early decades that show the action from the Indians’ standpoint (Griffith’s The Red Man’s View figured in the 1909 program) are remarkably sympathetic to their culture. The color portrays not only the beautiful desert landscapes of the American Southwest but also Navaho blankets and Pueblo sand paintings.

Toward the end of the week, when people asked me what my favorites had been so far, I forgot to mention Pandora and the Flying Dutchman, which had played way back on the opening Saturday. It has a reputation as a bizarre film, and I wasn’t expecting much beyond some glowing color images of two beautiful stars, Ava Gardner and James Mason. But I was pleasantly surprised by its well-handled fantasy tale of the Flying Dutchman visiting a contemporary Spanish seaside resort and finding his true love. In particular a lengthy flashback to the Dutchman’s original crime has a degree of stylization and intensity that allow it to avoid seeming absurd. The tale has an other-worldly quality that recalls some of Powell and Pressburger’s films-enhanced by the presence of cinematographer Jack Cardiff handling the Technicolor.

Unfortunately Track of the Cat (William A. Wellman, 1954) failed to similarly avoid a sense of the absurd in its overheated Tennessee William pastiche set on an isolated farm in the West. Lumbering dialogue lays out explicitly all the tensions among the members of the central family, exacerbated by the depredations of an elusive puma and a visit by the younger brother’s potential fiancée. The reason for its presence in the festival, though, was its color scheme. Wellman set out to make a “black and white film in color,” as the program describes it. Both the snowy landscapes and the interiors are dominated by white, black, and flesh tones, with the sole exception-the Robert Mitchum character’s bright red coat-disappearing from the action partway through.

Not only silents need restoring

Martin Scorsese’s influence hovers over the festival and the Cineteca Bologna. One of the two screening rooms in the Cineteca’s building is the Scorsese (the other being the Mastroianni). In recent years, films from the institution that Scorsese founded, the World Film Foundation, have been screened here. The WFF is dedicated to restoring and preserving films from countries whose archives might lack the resources to handle such major projects. This year’s presentations were Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gómez Muriel’s Redes (The Wave, 1936), Shadi Abdel Salam’s Al Momia (known in English as The Night of Counting the Years, 1969), and Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day (1991). The foundation also aided in the editing of Ingmar Bergman’s home movies into Images from the Playground (Stig Borkman, 2009).

I had seen The Night of Counting the Years in one of the faded 16mm copies that have long been the only form in which this Egyptian classic was available. The new copy is a vast improvement, finally revealing why this is considered perhaps the great Egyptian film. It is based around a true story from 1881, when a powerful tribe on the west bank at Luxor discovered a cave containing a huge cache of royal mummies and funerary goods that had been hidden away by ancient priests to preserve them after the extensive robbing of their original tombs. The tribe started selling items gradually on the illicit antiquities market, but one of its members revealed the location of the cache to the authorities, allowing them to salvage most of the mummies and their grave goods. The film was beautifully shot on location in the desert and temples of the west bank and provides a meditation on why the young man might have acted against the apparent best interests of himself and his family.

A 1991 Edward Yang film might not seem an obvious candidate for restoration, yet the complete version of A Brighter Summer Day was barely rescued from oblivion. The original negative does not exist, and the print materials on the shorter version were discovered to be moldy. Rescuing these and combining footage from both versions has resulted in a pristine new print of Yang’s greatest achievement. An in-depth look at Taiwanese society a decade after Chiang Kai-chek took over the island, it follows a middle-class boy drawn gradually into gang violence. The new version, which premiered at Cannes earlier this year, looked great on the big screen in the Arlecchino.

This and that

A brief tribute to Harry d’Abbadie d’Arrast included Laughter, the director’s first sound film. A romantic comedy, it stars Frederick March as a witty young composer aspiring to marry a wealthy society woman against her father’s wishes. The film has touches of Holiday and Design for Living, both films yet to be made. Laughter confirms d’Abbadie Arrast’s reputation as a good but lesser filmmaker in the Lubitsch mold.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

We all have reason to celebrate the fact that Georges Méliès’ films went into the European public domain this year. (The films have long been in the public domain in the U.S.) With obstacles to programming out of the way, the festival presented a program in homage, featuring twenty shorts presented by Serge Bromberg, who helped put together the extensive Méliès collection that came out in the U.S. and won the 2008 award for best DVD set here at the Cinema Ritrovato. (It came out in France earlier this year.) While all the films shown are on the DVDs, it was a treat to see them on the big screen. Bromberg provided a lively, if not entirely authentic, running commentary to “explain” the action of the final film, La Fée Carabosse.

Demonstrating that history repeats itself, Belgian film scholar Eric De Kuyper programmed a selection of titles dealing with financial speculation and crisis. These included perhaps the best of several items from Louis Feuillade shown during the week, Le Trust ou les batailles de l’argent (1911). It stars René Navarre, who would soon play Fantômas, as an unscrupulous detective, and the action is more in the thriller mode than a serious depiction of French finances. Also included was a 1916 German feature, Die Börsenkönigin (“The Queen of the Stock Exchange”), with a fine performance by Asta Nielsen as a woman more successful in finance than in love.

More to come from David, on Capra, DVD awards, and personalities glimpsed by a roving camera.

For our previous Cinema Ritrovato entries, see here for 2008 and here, here, and here for 2007. For a thorough discussion of dogs in early film, with comments by Mariann Lewinsky, see Luke McKernan‘s authoritative entry here. On the occasion of Edward Yang’s death in 2007, David offered an homage to him and A Brighter Summer Day here.

B is for Bologna

A big crowd assembles for one of the nightly screenings on the Piazza Maggiore.

Not laziness or old age (we hope) but sheer busyness has reduced our Bologna blogging to a single entry this year. Last year we managed three entries, but this time there was just so much to see, from nine AM to midnight, that we couldn’t drag ourselves away to the laptop. That it was blazing hot and surprisingly humid may have given us less biobloggability as well. Still, DB has many pictures, so maybe a followup blog with unusual images of critics and historians disporting in the sun….

Some backstory: Hosted by the Cineteca of Bologna, Il Cinema Ritrovato is an annual festival of rediscovered and restored films. Every July hundreds of movies are screened in several venues. For our 2007 report, with more background and some orienting pictures, go here and then here and here. Watch a lyrical trailer for the event here.

As before, both KT and DB contribute to this year’s entry. But first, the breaking story.

Freder and Maria, together again for the first time

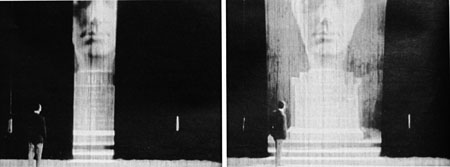

While we were there, the news of a long version of Metropolis broke. The estimable David Hudson offers a quick guide and an abundance of links at GreenCine. A rumor went around Bologna that fragments of the new Buenos Aires print would be screened, but instead there was a twenty-minute briefing anchored by Martin Koerber of the Deutsche Kinemathek. Along with him, Anke Wilkening (Friedrich-Wilhelm-Murnau Stiftung), Anna Bohn (Universitat der Kunste, Berlin), and Luciano Berriatua (Filmoteca Espanola) provided some key points of information.

*Provenance: The “director’s cut” was released in Argentina during the 1920s, with Spanish intertitles and inserts made at Ufa. A collector acquired a print. (Once more we have a collector to thank for saving film history.) When the Argentine film archive (Museo del Cine Pablo C. Ducros Hicken) received the copy in the 1960s, a 16mm dupe negative was made, and the nitrate original was discarded, a common practice at the time.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Condition of the copy: The print is very worn, as the frame reproduced by Die Zeit indicates. Can the torrent of lines and scratches be eliminated? The rescue isn’t likely to be perfect; the damage is perhaps “beyond the reach of our algorithms,” as Martin puts it. To my eye, judging from the Die Zeit frames, many images are lacking in texture and contrast as well.

*Completeness: Contrary to some reports, virtually all the missing scenes are present on the Argentine print, the single exception being a small portion at a reel end. Among the new sequences are scenes filling in the roles of three characters (Georgy, Slim, and Josaphat), a car journey through the city, and moments of Freder’s delirium.

How can the researchers be confident that the print is so complete? It’s a fascinating story.

Metropolis has been reconstructed many times since the 1960s. In 2001, the Murnau foundation presented a digital restoration of the film supervised by Martin Koerber in collaboration with Enno Patalas. In this version, which is available on DVD (Transit Film, Kino International) about 30 minutes of the original material are missing. In 2003-2005 Enno Patalas and Anna Bohn together with a team at the University of the Arts in Berlin created a “Study Edition” version in which the missing footage was represented by bits of gray leader. For the first time the full length of the film was reconstructed with help from the the original music score.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

In 2006 a “DVD study edition” was released by the Film Institute of the Berlin University of the Arts (Universität der Künste Berlin; DVD-Studienfassung Metropolis). This scrupulous version includes the original score, a lot of production material, and the complete script by Thea von Harbou. It’s a model of how digital formats can assist documentation of film history. The DVD incorporates production stills and intertitles from the missing scenes, and presents each scene in its original duration (sometimes with only gray leader onscreen). The editors determined the duration of each scene by a critical comparison of the remaining film materials with the music score and other source materials. This DVD edition was released in a limited edition available to educational and research facilities. For information see here or here.

Bohm and Patalas’s comparative method proved itself valid: The Buenos Aires footage fitted the gaps in their study edition perfectly!

A viewing copy will not be forthcoming immediately, given the restoration task, but sooner or later we will have a good approximation of the fullest version of one of the half-dozen most famous silent movies. Getting news like this while among archive professionals is one of the unique pleasures of Cinema Ritrovato. (Special thanks to Dr. Bohn for clarification on several points and to enterprising film historian Casper Tybjerg, who helped me get a copy of the Die Zeit issue.)

Two Davids and a Kevin: Robinson, Brownlow, and Shepard at a critics’ lunch.

Powell meets Bluebeard and Bartók

KT: One of the high points of the week for me was Michael Powell’s 1964 film of Béla Bartók’s short opera Bluebeard’s Castle. It was made for German television and shown in Bologna as Herzog Blaubarts Burg. Unfortunately it was programmed opposite the screening of fragments from Kuleshov’s Gay Canary, but Powell’s post-Peeping Tom films are so difficult to see that I made the difficult choice and gave up hope of seeing the entire Kuleshov retrospective.

Despite being relatively recent in comparison with most of the films shown during the week, Herzog Blaubarts Burg is one of the most obscure. I felt it was an extremely rare privilege to see it, one which I will probably never have again, at least in so splendid a print.

The film belongs to the late period of Powell’s career, after the controversial Peeping Tom had made it impossible for him to work within the mainstream film industry. It was produced by Norman Foster—though not the Norman Foster who directed Journey into Fear and several of the Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto films. This Norman Foster was an opera singer whose stage career was cut short by a dispute with Herbert von Karajan. His widow, Sybille Nabel-Foster, explained this and described how Foster produced and starred in two television adaptations, Herzog Blaubarts Burg and Die lustigen Weiber von Windsor (1966). Foster had originally approached Ingmar Bergman to direct the former, but when that proved impossible, Powell stepped in—and probably a good thing, too. It was definitely his kind of project.

The two performers are perfect for their roles. Foster plays Bluebeard brilliantly, having both a powerful bass voice and the necessary combination of handsomeness and a sense of threat. His co-star, the excellent soprano Ana Raquel Satre, recalls the pale beauties of some of Powell’s earlier films (Kathleen Byron as the increasingly mad Sister Ruth in Black Narcissus, Pamela Brown in I Know Where I’m Going!, and particularly Ludmilla Tcherina in The Tales of Hoffman), but she also bears a resemblance—perhaps deliberately enhanced through costuming and make-up—to Barbara Steele and other horror-film heroines of the 1960s.

The film was shot cheaply in a Salzburg studio, using garish, modernist settings against black backgrounds. These create a labyrinthine, floating space that avoids seeming stage-bound. (Hein Heckroth, the production designer, had previously worked on several Powell films, including The Red Shoes and The Tales of Hoffman.) I was reminded of Hans-Jürgen Syberberg’s Parsifal (1982), which looks somewhat less original in the light of Powell’s film.

As Nabel-Foster explained, after its initial screening on German television, Herzog Blaubarts Burg has been shown seldom because of rights complications with the Bartók estate. Non-commercial screenings have occurred on public television in the U.S. and Australia, but basically the film is off-limits until the copyright expires in 2015, seventy years after the composer’s death. Nabel-Foster has been providently preparing for a DVD release, gathering the original materials.

The print shown was a privately held Technicolor original from the era, in nearly mint condition. (The British Film Institute has a print as well.) The sparse subtitles written by Powell himself were added for this screening.

I’m not convinced that the film is quite the masterpiece that some claim, but it is a major item in Powell’s oeuvre nonetheless, and I felt privileged to have seen it in ideal conditions.

[July 12: Kent Jones, a great admirer of Powell and Bluebeard’s Castle, tells me that he programmed it at the Walter Reade in New York for a centenary retrospective of the director’s work in 2005. Foster’s widow introduced that screening as well.]

Janet Bergstrom and Cecilia Cenciarelli summarize their research on von Sternberg’s lost film The Sea Gull.

1908 and all that

KT: There were several programs of silent shorts, which I could only sample, as they tended to play opposite the Kuleshov films. As usual, the Bologna program included selections of short films from 100 years ago, so we were treated to numerous films from 1908. I was particularly pleased to see The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers, directed by Lewin Fitzhamon, who had made Rescued by Rover two years earlier. That film had been so fabulously successful that it had actually been shot three times as the negatives wore out from the striking of huge numbers of release prints.

The Dog Outwits the Kidnappers at first appears to be a sort of sequel (as it is described in the program), since it stars the same dog (Blair) who had played Rover, and again there is a kidnapped baby. It’s not really a sequel, though, since Cecil Hepworth, who had played the father in the earlier film, here appears as the kidnapper, and the dog is not named Rover. The new film is more fantastical than the original, since the dog races after the car in which the child is abducted and rather than fetching its master, effects the rescue itself by driving the car back home when the villain leaves his victim unattended!

Other 1908 films I particularly enjoyed: In Pathé’s Le crocodile cambrioleur, a thief hides inside a huge fake crocodile and crawls away, creating fear wherever he goes. The Acrobatic Fly by British director Percy Smith, provides a very close-up view of an apparently real fly juggling various small objects. (How was it done? It’s a mystery to me.)

Another retrospective series was “Irresistible forces: Comic Actresses and Suffragettes (1910-1915).” The suffragette films were rather depressing, despite the fact that many were meant at the time to be comic and amusing. Mostly the joke was how masculine these determined women were, a self-verifying proposition when the filmmakers often chose to have the suffragettes played by men. My favorite program was one involving early French female comics. I’ve long been fond of Gaumont’s Rosalie series since seeing a few at an early-cinema conference in Perpignon, France back in 1984. Rosalie, a chubby, cheerful little dynamo played by Sarah Duhamel, was highly entertaining in three films in the “France—Rosalie, Cunégonde et les autres…” program.

As Mariann Lewinsky, who devises these annual series, pointed out, Duhamel is the only early female French comic whose name we know. Léotine, represented here in Rosalie and Léotine vont au théâtre, is played by an anonymous actress. I had not encountered Cunégonde, also anonymous, before, but she proved to be quite amusing as well. I particularly liked Cunégonde femme du monde, where she plays a maid who dresses up as a society lady when her employers go off on a trip; the carefully constructed story and twist ending are impressive for such an apparently minor one-reeler.

It was a treat to see a succession of gorgeous prints of von Sternberg’s films. I particularly enjoyed seeing Thunderbolt (1929) again after many years. Back in 1983 I taught a survey film history course in which I used the director’s first talkie as my example of the transition to sound. Not a good example, I must admit, since Thunderbolt is completely atypical, with its highly imaginative use of offscreen sound. The second half, set primarily in a prison block, involves shouts from unseen cells and a small band that breaks into songs, often completely out of tone with the action, at unexpected moments. Eisenstein and the other Soviet directors would have thoroughly approved of its sound counterpoint. I have to admit that I prefer von Sternberg’s George Bancroft films (Underworld, Docks of New York, and Thunderbolt) to the Dietrich ones. Not only are the plots simpler and more elegant, but they contain a genuine element of emotion that is not, as in the Dietrich series, frequently undercut by irony.

I didn’t make it to many of the CinemaScope films playing on the very big screen in the Cinema Arlecchino theater, but I did enjoy two westerns. Anthony Mann’s Man of the West (1958) and John Sturges’ Bad Day at Black Rock (1954) both looked terrific and were highly popular with everyone we talked to. The latter was particularly a revelation, since in contrast to the Mann, it hasn’t had much of a reputation among cinephiles.

A Rodchenko angle for Yuri Tsivian.

Teacher and experimenter

DB: As Kristin mentioned, we missed a lot of the “Hundred Years Ago” series—a pity, since 1908 is a miraculous year—in order to keep up with one of our favorite directors, Lev Kuleshov.

In the 1960s and 1970s, it was common to say that Eisenstein and Vertov were the most experimental Soviet directors, while the others were more conventional. Then we realized that in films like Arsenal (1928), Dovzhenko had his own wild ways. Then we discovered the Feks team, Kozintsev and Trauberg, and the bold montage of The New Babylon (1929). A closer look at Pudovkin, particularly his early sound films like A Simple Case (1932) and Deserter (1933), revealed that he too was no timid soul when it came to daring cutting and image/ sound juxtapositions. But surely their mentor Kuleshov, admirer of Hollywood continuity and proponent of the simplest sorts of constructive editing, played things safe?

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

Wrong again. Just as we must reevaluate the other master Soviet directors (even in their purportedly safe Stalinist projects), so too does Kuleshov deserve a fresh look. He got this thanks to Yuri Tsivian, who with the help of Ekatarina Hohlova (right; granddaughter of Kuleshov and his main actress Aleksandra Hohlova) and Nikolai Izvolov, mounted a superb retrospective. It ranged from Kuleshov’s first solo effort, Engineer Prite’s Project (1918) to his final film, the short feature Young Partisans (1942-3, never released).

My admiration for Kuleshov, confessed in an earlier blog entry, already led me to spot some weirdnesses in Mr. K’s official classics. The Extraordinary Adventures of Mr. West in the Land of the Bolsheviks (1924) boasts some very un-formulaic cutting in certain passages (including an upside-down shot when cowboy Jeddy ropes the sleigh driver), and By the Law (1926) makes chilling use of discontinuities when the scarecrow Hohlova holds the Irishman at gunpoint. But thanks to the retrospective we can confidently say that Kuleshov was no less venturesome, at least in certain projects, than his pupils.

Soviet specialists already suspected that The Great Consoler (1933) was K’s sound masterpiece, and another viewing confirmed it. It incorporates three registers. William S. Porter, in prison but serving in the pharmacy, witnesses brutality and oppression and is driven to drink. Under the name O. Henry he writes cheerfully sentimental tales as much to console himself as to charm readers. His stories are in turn consumed by shopgirls like Dulcie, a romantic who may not realize how unhappy she is. Kuleshov adds a level of sheer fantasy, represented by a pastiche silent film dramatizing O. Henry’s “A Retrieved Reformation,” in which a safecracker trying to go straight reveals his identity by saving a girl trapped in a bank vault. The embedded story features characters from the other two levels, convict Jimmy Valentine and Dulcie’s lover, a vaguely sadistic businessman in a ten-gallon hat.

The Great Consoler reminds us of the popularity of O. Henry in the Soviet Union, both among readers and the Russian Formalist literary theorists, who were fascinated by his flagrant, playful artifice. (Boris Eikhenbaum’s essay on the writer is one of the most brilliant pieces of literary analysis I know.) Even though Kuleshov must denounce Porter for reconciling the masses to their misery under capitalism, the zest of the embedded film and the unique architecture of the overall project pay tribute to another entertainer who did not forgo experimentation. And Kuleshov’s image of a writer in prison probably had Aesopian significance for artists in the era of Socialist Realism.

K’s other major sound experiment, less widely seen, is Gorizont (1932). The title is at once a man’s name and the Russian word for “horizon”—a metaphor literalized in the final shot of a train leaving a tunnel. As Yuri pointed out, it is one of the few Soviet films centered on a Jew, and so the formulaic growth-to-consciousness plotline takes on a new resonance in the light of Slavic anti-semitism. Lev Gorizont is an amiable, somewhat thick young man who dreams of emigrating to the US to make his fortune. But in New York he finds only poverty and disillusionment, eventually returning home to help make a better society. Famous for its use of sound, Gorizont contains a passage of imaginative “counterpoint.” Both Lev and his friend Smith have been jilted by the social-climber Rosie. As they talk, we hear warm piano music, but not until the end of the scene does Smith speculate that probably Rosie is somewhere listening to Chopin. The music has retrospectively functioned somewhat like crosscutting, suggesting that Rosie now lives among the wealthy.

Kuleshov, like Eisenstein, gained his fame for his ideas on editing and sound montage, but both men were deeply interested in performance. Kuleshov’s idea that the film actor should become an angular mannequin carries on the impulse of Meyerhold’s biomechanics, and he anticipated CGI software in suggesting that human action could be plotted on a three-dimensional grid. Still, Kuleshov usually gives his figures a fluid dynamism that doesn’t seem mechanical. The three narrative registers of The Great Consoler are delineated largely through acting: naturalistic and slowly paced in the prison scenes, rigid and posed in the shopgirl romance, and broad and eccentric in the embedded silent movie.

Kuleshov’s performance theories popped out of other films in the series. What survives of The Gay Canary (1929) centers on a cabaret actress courted by lustful reactionaries during the civil war, and her scenes of fury, as she flings around flowers, vases, and pieces of furniture, come off as acrobatic rather than realistic. Naturally, the circus milieu of 2 Buldy 2 (1929) encourages stunts. A father and son, both clowns, are to perform together for the first time, but the civil war separates them, and the elder Buldy, tempted for a moment to acquiesce to the White forces, casts his lot with the revolution. At the climax Buldy Jr. escapes the Whites thanks to flashy trampoline and trapeze acrobatics; the gaping enemy soldiers forget to shoot. Even Kuleshov’s more naturalistic films show flashes of kinetic, stylized acting. A partisan listens to a boy while draping himself over a door. A Bolshevik official answers the phone by reaching across his chest, twisting his body so the unused arm can hike itself up, right-angled, to the chair.

The interaction of the body with props occurs with a special flair in Young Partisans. A Bolshevik partisan tells some children how a boy saved his life in a German-occupied town (This flashback was directed by Igor Savchenko and functions as a short film on its own.) Having learned their lesson, the kids gather in their schoolroom and under the teacher’s eye draw a map of the partisans’ camp. But when Nazi soldiers burst in, the teacher flips the blackboard over; now all we see is algebra.

A scene of Hitchcockian suspense ensues: Will the Germans turn over the blackboard and discover the map? The tension is enlivened by a grotesque moment, when one alcoholic soldier finds a jar holding a pickled frog and decides to drink the formaldehyde. “Draw a map—show me where the partisans are!” the officer demands. He flips the blackboard, and in a split-second we see a boy crouching behind it; the blackboard swings into place toward us, the map now erased. The boy ducks into his seat, brushing off chalk dust.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

There were plenty of other revelations. We got the reconstructed Prite (was it the first really modern Soviet film?), a bit of an original Kuleshov experiment in constructive editing, and a tantalizing fragment from The Female Journalist (1927), with a surprisingly pensive Hohlova as a modern-day reporter. Sasha (1930), directed by Hohlova herself, was a sympathetic portrait of a pregnant woman. An educational film called Forty Hearts (1930) explained the need to electrify the Soviet countryside and was brightened by faux-naïve animation. Timur and His Crew (1942), with some of the charm of a Nancy Drew movie, showed Young Pioneers helping on the home front; it unexpectedly centered on a girl’s devotion to her military father.

One of the biggest surprises was news of Dokhunda (1936), an ethnographically based fiction set in Tazhikistan. Although the film is lost, Nikolai has reconstructed its plan, revealing that Kuleshov adopted a strange preproduction method. He prepared “living storyboards,” photos of the cast enacting the scenes. He then drew and scratched on them, creating busy, nervous backgrounds or changing the figures’ features and hair styles—Kuleshov as pre-Warhol scribbler, or a graffiti artist tagging his own images.

Nikolai has also finished a DVD edition of Prite that exemplifies what he calls hyperkino, a way of annotating and comparing a film’s images, texts, and supplementary materials for instant access. Another project involves the Yevgenii Bauer classic, The King of Paris (1917), which Kuleshov completed. We haven’t had the intertitles for this, however, but now Nikolai has discovered them, and they will go on the DVD version that is being completed. For more information on these projects and Dokhunda, go to hyperkino.net.

So Kuleshov stands revealed as more supple and ambitious than most of us once thought. Once more Bologna plays to its strengths—filling in gaps but also forcing us to rethink what we thought we knew.

The key issue: What the hell am I going to be seeing now? From left, Olaf Muller, Jonathan Rosenbaum, Don Crafton, Haden Guest, and KT.

So much else to report, so little time. Besides The King of Paris, there was a string of fine 1910s films. Raoul Walsh’s Pillars of Society (1916), while not a patch on his Regeneration of the previous year, offered a solid adaptation of Ibsen. The Dawn of a Tomorrow (1915), James Kirkwood’s Mary Pickford vehicle, seemed to me flat and talky, but others liked it. For me the outstanding item was Paul Garbagni’s In the Spring of Life (1912). Beautifully directed in the tableau style, with precise depth choreography and a stirring scene of a theatre consumed by fire, it starred three men who would become great directors very soon: Sjöström, Stiller, and Georg af Klercker.

Not to mention the von Sternbergs (I liked An American Tragedy much more on this outing), the Scope revivals (Man of the West, Ride Lonesome in a handsome digital restoration from Grover Crisp), my first viewing of Duvivier’s La Bandera (1935), the Monta Bell items (most notably the incessantly energetic Upstage from 1926), and on and on.

What can Gianluca Farinelli, Peter von Bagh, and Guy Borlée, along with their devoted staff members, do for an encore? Bravo! Now take a rest.

Standing Room Only for the rarely seen Children of Divorce (Sternberg/ Lloyd, 1927).