Archive for the 'Festivals: Ebertfest' Category

A second chance at childhood

DB here:

This year Ebertfest has been such a swirl of activity that I hardly know where to start. Jim Emerson’s reportage, here and here, decorated with neat photos and trim Tweets, has admirably hit the high points—the panels, the Q & A’s, and the young Web critics, or “foreign correspondents,” that Roger has summoned to his annual get-together. There’s even streaming of the panels and Q & A.

After participating in four events in rapid succession, I find that I’m still sorting out impressions. I hope to do justice to the broad swathe of doings in another entry after I get home tomorrow. For now, why not just let my impulses take over and write about my most enjoyable movie so far?

Takita Yojiro’s Departures (2008) well deserves the standing ovation that greeted him when he stepped out on the Virginia Theatre stage. I mentioned the film last year, and since then I’ve seen it two more times, not counting the splendid projection Friday. I was happy that Roger shares my affection for the movie. In my remarks before the screening, I praised the movie’s willingness to go straight for the heart. This sort of sincerity, which John Ford or Frank Borzage would have understood, is hard to come by in today’s American cinema, where emotion tends to be framed by irony or self-consciousness cuteness (500 Days of Summer). My intro did mention the comedy in the film, but I didn’t stress it enough. Watching it with the Ebertfest audience again taught me that the film cleverly uses humor to lead us into its pathos.

Takita Yojiro’s Departures (2008) well deserves the standing ovation that greeted him when he stepped out on the Virginia Theatre stage. I mentioned the film last year, and since then I’ve seen it two more times, not counting the splendid projection Friday. I was happy that Roger shares my affection for the movie. In my remarks before the screening, I praised the movie’s willingness to go straight for the heart. This sort of sincerity, which John Ford or Frank Borzage would have understood, is hard to come by in today’s American cinema, where emotion tends to be framed by irony or self-consciousness cuteness (500 Days of Summer). My intro did mention the comedy in the film, but I didn’t stress it enough. Watching it with the Ebertfest audience again taught me that the film cleverly uses humor to lead us into its pathos.

The first half hour handles a lot of narrative business. We need to meet the main characters and learn their situation, of course. We also need an introduction to the trade of encoffinment, the practice of preparing the body of the deceased for cremation. But if the story proceeded chronologically, we wouldn’t get this introductory scene for quite a while. So the film provides a pre-credits flashforward that serves up the process, making it palatable with a dose of humor.

We see Daigo and his crusty boss Sasaki visiting a household and arranging a young woman’s corpse. No, it’s not a woman: Daigo discovers that the corpse has a penis. Should they apply male or female make-up? This bit of comedy undercuts the solemnity of the occasion and builds up curiosity: How to resolve the situation? Cut back to Daigo two months earlier, playing the cello in an orchestra that is about to be disbanded. The end of his musical career sends him and his wife back to his hometown seeking a new job.

Since the first scene shows Daigo practicing the “sending-off” trade, we know how that search will turn out. With our superior knowledge we can enjoy all the misunderstandings that fill the first scenes in Yamagata. A misprint in the newspaper ad makes Daigo think he’s applying to a travel bureau; Sasaki hires him without glancing at his résumé; Daigo becomes disturbed at the prospect of handling dead bodies, but the generous advance makes him decide to try. Moreover, in the opening we’ve watched him skillfully executing the routines of the ceremony, so we know that he will eventually succeed. The question is how.

One of the pleasures of movies is showing us how people work. (Think of Steve McQueen running the ship’s engine in The Sand Pebbles, or the arcana of sleight of hand in The Prestige.) So the opening fascinates by introducing us, matter-of-factly, to a craft. In doing so, the scene treats the ceremony fairly objectively. A second ceremony is staged for a video demo, with Daigo serving as the corpse. Here the comedy is even broader, but we’re still learning about the procedures.

A third ceremony, involving the decomposed body of an old woman, is skipped over, but it is heavy in consequences. It drives Daigo to the bathhouse to clean up, and there he reunites with an old friend and his mother, the bathhouse owner. The third encounter also makes Daigo return to playing the cello, using the instrument he was given as a boy. In a way, the whole story offers another chance at childhood. Daigo, feeling guilty for abandoning his mother and angry at the father who deserted them, will be granted a chance to reconcile with both.

The film’s next sending-off ceremony is a turning point, for it’s Daigo’s first encounter with the dignity of Sasaki’s craft. With the young man we study the tender precision with which Sasaki tucks the dead wife’s garments around her, strokes her face and hands, and applies her favorite lipstick. The husband, initially enraged that Sasaki and Daigo arrived late, ends up moved to tears: “She never looked so beautiful.” Here, fifty minutes into the film, humor is suspended in order to present a compassionate gravity in the face of death. Characteristically, however, a certain lightness returns when in the car Sasaki and Daigo chew noisily on the snacks the husband has given them.

From a penis joke and Daigo’s humiliation at playing dead for the video, the film has led us to care about the characters. We can relax and start to appreciate the depths of what Sasaki and Daigo do. The film will busy itself with new problems—the shame Daigo faces in pursuing this craft, his stratagems for concealing it from his wife Mika, his revived memories of his father, a subplot involving another son impatient with his mother—but we are now ready for these enrichments of the central situation. Eventually too we will see the encoffinment ceremony though other characters’ eyes, as they arrive at our appreciation of its astringent tenderness.

The shrewd placement of the opening flashforward has gently pulled us into the story’s world and its key issue, the tie between the living and the dead. By the time that we return to that family and their transvestite son, the question of how to make up his face has gathered a thick array of associations. The parents’ quarrel anticipates all the other parent/ child relationships that accrue across the film, and the resolution of it, through a father acknowledging his guilt, provides a foretaste of the climax.

The unruffled exactness of Sasaki’s tradecraft is mirrored in Takita’s direction. This is classic Japanese filmmaking: Not a wasted shot, each angle precisely depicting what we need to see at any moment. After the fumbling and flailing displayed by most contemporary Hollywood directors, after filmmakers’ urge to “give a scene energy” manages to muff getting an actor out of a car, it’s a pleasure to watch powerful effects achieved delicately. How many movies can wring tears from uncurling a fist or an image of a smooth stone on a woman’s palm?

Several scenes of the dead include photos of the person in life. Early on, these are given force through simple cutaways.

Once he’s trained us to watch for these photos, Takita can let us compare death and life through more discreet revelations, as when a slight movement of Daigo’s head allows us to see a photo that remains out of focus.

Or take the moment when Daigo comes home after preparing the decomposed body. He gags when he sees that Mika is preparing raw chopped chicken, but then he frantically embraces her. The gestures begin in panic but end in desire. At this point Takita cuts to a new angle, a long shot showing the couple, the table, and the dish that triggered it all.

It’s always sound practice to tactfully recall earlier moments in a film, but the composition also completes the scene’s arc from disgust at death to ardent vitality.

The whole film’s craftsmanship is as warm and fastidious as the job practiced by the send-off experts. At the end, Daigo’s respectful handiwork, with all its dispassionate concern, turns into caresses, the intimate gestures of a son rediscovering a parent through physical contact. Modulation of movement, mood, and attitude; slight variations that become subtly expressive; the prosaic detail that cuts right through you: In this domain the Japanese cinema has no superior. Departures shows that this tradition lives on.

Take my film, please

Kristin here–

As I mentioned in our main entry about Ebertfest, Nina Paley’s animated feature, Sita Sings the Blues, was one of the highlights of the festival. Afterward I had the privilege of moderating the onstage discussion with the director and University of Illinois film professor Richard Leskovsky, who has a special interest in animation.

Sita has not had a regular theatrical release, though Nina has made it available to theaters, festivals, and everyone with access to a high-speed internet link-up. She gives it for free to anyone who wants it, believing that people who see it will pass the word along and that as the film becomes more well-known, it will become more valuable as well. Income should flow in. Nina is confident, some might say cocky about this. The thing is, she may be right. Sita is a terrific film, and I can well imagine a ground-swell of interest gradually building. Indeed, it’s happening already. Here I am, blogging about it, and others are as well. Non-bloggers are emailing their friends. Festivals have booked it up to the end of this year and beyond.

Roger Ebert found Sita early on, and his program notes were also his online review, which begins:

I got a DVD in the mail, an animated film titled “Sita Sings the Blues.” It was a version of the epic Indian tale of Ramayana set to the 1920’s jazz vocals of Annette Hanshaw. Uh, huh. I carefully filed it with other movies I will watch when they introduce the 8-day week. Then I was told I must see it.

I began. I was enchanted. I was swept away. I was smiling from one end of the film to the other. It is astonishingly original. It brings together four entirely separate elements and combines them into a great whimsical chord.

The four elements are: a sketchily animated account of the breakup of Nina’s marriage; the tale of Rama and Sita from the Indian epic, the Ramayana; musical numbers that all borrow recordings of Ms Hanshaw; and three shadow-puppet narrators who try, not always successfully, to recall the details of the Ramayana and its background history. As Roger says, somehow all this achieves complete unity.

The timing of the Ebertfest screening was fortuitous. Within the next few weeks, the DVD release is due. Of course, you can already watch it online and/or burn your own DVD. But for those who can’t or don’t want to, you can buy the DVD package, complete with what is described on the film’s website as a predownloaded copy of the film.

As Roger’s review says, Nina is a hometown girl. She started out doing comic strips and then made some  animated shorts before progressing to Sita, her first feature. Her father taught at the University of Illinois. Her mother was an administrator there. Both have supported her in the making and distribution of Sita, and both were present throughout the festival.

animated shorts before progressing to Sita, her first feature. Her father taught at the University of Illinois. Her mother was an administrator there. Both have supported her in the making and distribution of Sita, and both were present throughout the festival.

Here’s a transcript of our conversation (that’s Nina at the far left, Richard, and me). Applause, laughter, and a fast-talking film director at times defeated my efforts to catch every word of my recording, so some details have been lost.

KT: I know you want to talk about how you’ve been getting the film out to the public, but I’d like to start off by talking about the film itself, which is fascinating. I think we can start with the computer animation. A lot of people think that you were pushing a lot of buttons and somehow the computer was generating the images. But obviously you were generating them yourself by painting and collage and so forth. Could you just start with the process of what you did before you put this material into the computer and then what you did afterwards?

NP: Well, there are a whole bunch of different styles and techniques used in the film. The style of the musical numbers, actually I drew that in Flash using a lot of really simple tools, so the perfect circles have a smoothness that you don’t get by hand. By the way, I want to mention that what you saw was not 35mm. You saw HD-cam, and there are actually 35mm prints of this, and seeing it here was very strange. It was unusually solid, rock solid, a little bit troublingly solid, although that is the ideal that film technology has been striving for. But 35mm prints have all these scratches and splices, and grain and a kind of warmth that moves around, which is almost like a kind of very desirable filter that really warms up the film. So watching it in 35mm is different. I was noticing how computery it looked on the HD projection at this particular size, because I was looking for imperfections that simply weren’t there.

But anyway, yeah, I did some paintings on parchment paper. To me, some things were simple, because I only had me working on the animation, and I used as many computer shortcuts as I possibly could. Most of the technique was what’s called “cut-outs,” so I made pieces of things, moved them around, and the computer does what’s called “tweening.” [i.e., in-betweening, filling in the frames between key points] There’s a little bit of full animation in there. It would take a long time to say everything that I did.

KT: Yeah, but every bit of that visual material was something that you put into the computer in some fashion, so that-

NP: The computer didn’t draw it, that’s for sure. I drew it, whether I started with paper or drawing on a little [digital] graphics tablet or eventually I got what’s called a Cintiq, which is a monitor you can draw on. You can draw straight into a program through the monitor, and so what’s on the monitor-it tricks you into thinking you’re actually drawing on the screen, but it went through both my hand and the computer.

KT: Is this the kind of thing you teach? Do your students learn how to do this kind of animation?

NP: No. I’d love to teach this. A lot of the students are just not [inaudible]. So right now I’m teaching visual storytelling, which is a much more basic class, and I taught something called “classic film and video” for a while at Parsons [School of Design]. I actually really like to teach artists. I’m teaching people who already know what they want to say and already have a voice and just need a little bit of technical-it’s slightly faster if they ask me rather than reading a manual. I learned by reading manuals.

RL: It struck me that you’re a woman artist making an animated feature, and actually one of the very first animated features, done ten years before Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, was Lotte Reiniger’s The Adventures of Prince Ahmed, which also deals with Eastern myths. You actually did a little bit of the cut-out animation there, too, with the shadow-puppets. That brings a nice circularity-

NP: Well, hopefully this isn’t the last one!

KT: Was that the silent film that you referred to in your film?

NP: I still haven’t seen that film. First of all, everything has influenced me, because everything influences everything else. Culture [inaudible] language, so there’s a language of cell phones, a language of animation that comes from every piece of animation that’s been shared ever. So even if I haven’t been directly influenced by something, I haven’t seen the actual film, I will have been indirectly influenced by it simply keeping my eyes open.

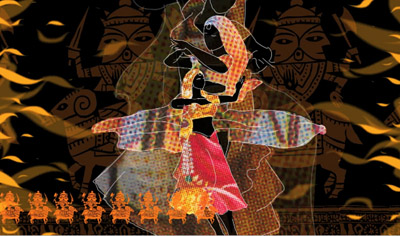

RL: All the Annette Hanshaw songs are accompanied with the Flash animation, but it looked like there was a couple of different styles of Indian art represented there, from different periods. Tell us a little bit about what the choice was.

NP: The Ramayana is thousands of years old, and it also covers an enormous chunk of geography. It’s very popular not just in India but also in Cambodia, Thailand, Polynesia, Indonesia, this huge swath of South and Southeast Asia-parts of China. So there’s just this enormous range of art styles that have come up around it, and the styles I used in the film were influenced by just a tiny, tiny sample of that. Obviously shadow puppets. The designs were derived from puppets from Indonesia, Korea, Thailand, Malaysia, and also India. There’s a whole slew of paintings. There’s lots of Ramayana paintings that were actually commissioned by Muslim [inaudible] who had money. There were collages of these traditional arts. Everything went into the hopper, all going into my head Everything goes in there, grinds up, and comes out.

KT: Traditionally in animation the entire soundtrack is done first, which is not the way it’s done in regular live-action filmmaking, but of course it’s virtually impossible to synchronize cartoons if you have someone doing the voices after the animation is done. So could you tell us a little about the soundtrack and how much of it you had ready by the time you started the visuals?

NP: Well, I should say, the whole production, it’s not like I had everything ready when I started the visuals. The way you’re supposed to make a film, first you’re supposed to write a treatment, and then you’re supposed to write a script, and then you’re supposed to, if it’s animation, have everything designed and do breakdowns and storyboards and this and that, and then at the very end you animate it.

I didn’t have to do that, because it was just me working and it was with a computer. So I came up with things as I was going along. The whole structure of the story was there, because the Ramayana is this very well-established story that’s been told billions of times. I knew that story. I also had the songs, so the first thing that I synchronized and edited was the songs. As I was working on those, I was figuring out how the rest of the film was going to come together. The [inaudible] part of the film was the three narrators, who were just friends of mine who I convinced to go into a recording studio, and I asked some questions about the Ramayana. They were all very busy and went, “Oh, I should have read more before.” The conversation that they had was actually quite typical, because I had so many conversations with so many Indians, who-it was just uncanny, they really captured the twenty-first century zeitgeist of Ramayana, I guess.

RL: That intermission was a bit daring.

NP: I should mention that the 35mm print, depending on where you see it, it has surround sound and the HD only has stereo. If you see it on 35mm, depending on what speaker you’re near, you’ll hear different complete conversations coming out of each. Some of those conversations are extremely funny. I recommend the left rear speaker. There will be Will Franken, who’s a distribution executive, talking about unsellable the film is. And there are people on the front right speaking Hindi. I think they’re saying, “I thought this was a children’s film.”

So, yes, intermission. Old American musicals had intermissions. I was watching some of them while I was working on the film, and sure enough, two-thirds of the way through, intermission comes up. Bollywood films still have intermissions-a three- or four-hour-long Bollywood film has a little gap. So it was a tribute to both old American musical films and all Bollywood films. When I showed the film in Livingston, New Jersey to an audience of primarily Indian-Americans, during intermission they just left for 15 minutes. And they missed my favorite part of the film, which is the part that comes a minute after the intermission.

Nina’s favorite part, shortly after the intermission

KT: I can second that statement about the 35mm, because I was lucky enough to see this film three weeks ago in 35mm at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and it’s a different experience. I’ve enjoyed both of them, but I think there are definite advantages to 35.

It’s actually much easier for most people to see this film on a computer screen or television, because you chose a very unusual way to disseminate the film to the public. Can you talk a little about that?

NP: Why, yes, I can! You can see this film for free online if you go to sitasingstheblues.com and follow a variety of links and get the film. You can get everything from a streaming version from New York Public Television to a 200 gigabyte file from which you can make your own 35mm print if you have $30,000 to download it. Briefly, every file I have for the film is either online now or it’s going to go online. It’s a completely decentralized distribution model. People have compared it to Radiohead’s [inaudible] English model [for their “In Rainbows” album, 2007], but that’s different, because that relied on a single, central location where you got the audio, and it was tracked. It was simply what you decided to pay.

Mine is totally decentralized. I shouldn’t even call it “mine” anymore. It’s yours. This film belongs to you and everybody else in the world. The audience, you and the rest of the world is actually the distributor of the film. So I’m not maintaining a server or host or anything like that. Everyone else is. We put it on archive.org, a fabulous website, and encourage people to BitTorrent it and share it. That’s what’s happening, and we hope people do it more. There’s also broadcast versions, which you can download. If anyone here is from a television station, you can broadcast this for free.

Which begs the question, why is Nina Paley giving her work away for free? Doesn’t she want to get money? The answer is yes, I want to get money, and I believe that I will get money. I think I am getting money from this, because the more people share the film, the more valuable the film becomes. I have told people after screenings that they can get the film for free online, but I have some DVDs which I sell for twenty bucks, and here for twenty-five bucks-the Virginia is still remodeling, so this is for the Virginia.

I should also mention regarding DVDs that we, my mom-Oh, I should mention my mom! Sorry, I[inaudible] my parents, of course, who gave me the gift of life and all that, but my mom, who gave Sita Sings the Blues the gift of being its festival-relations manager, which is a huge, huge job. For those who don’t know, my mom was the main administrator of the math department of the University of Illinois and is a spreadsheet master and business-communications master and stuff like that and has been just essential to the film having such a successful festival life. So, thank you, mom! [Applause]

Anyway, I have made thousands of festival screeners so that festivals will have something to preview, and we’re down to the last 35, or at least we were this morning, and we handed them to the people in the Virginia, and that’s it for DVDs until a few weeks from now I’ll have the new purchasable DVD edition available.

RL: Will there be special features?

NP: Because the film is free, people can subtitle it freely, and the new one will have some subtitles. There’s gonna be more subtitles online. It’s been translated into French and Hebrew and Spanish and Italian and pirate. [applause and laugher covers a stretch of speech] The thing is, the film is now half-way. It will just continue growing, so whatever the DVD is, it’s just snatched off the stuff we have as of this week. So it’ll be the film, it’ll be a bonus feature called Fetch, a film I made, it’ll be some subtitles, I think there’ll be a couple different audio options.

It’ll be a very nice package, because basically what I’m selling is packaging for the film. If you have a computer, you’ve got your own packaging. You just download it. But many people just the same want an actual printed package. There’ll be two editions. There’s the artist’s edition, a limited edition of 4,999 DVDs, because for every five thousand DVDs I sell, I have to pay the licensers more money. You may think that’s too bad, and it’s OK if the other DVD distributors pay the licensers more money, but I [inaudible] paid $5,000 in order to decriminalize the film, so that I wouldn’t go to jail.

Jean Paley from the audience: Fifty thousand!

NP: Fifty thousand, yeah. Fifty thousand dollars is enough.

KT: Which is for the song rights.

NP: Yes. Those old songs. I cannot thank Roger enough for writing about this film. Also, after he wrote about it on his blog, my colleague, a professor of copyright law here, said, “Does he know about the copyright issue of the songs?” The film uses old songs that were written and performed in the late 1920s. Had they been from 1923, they would be in public domain now. When they were written, they were supposed to be in public domain in the 1980s, but there have been these continuous, retroactive copyright extensions, so they may never enter the public domain.

NP: Yes. Those old songs. I cannot thank Roger enough for writing about this film. Also, after he wrote about it on his blog, my colleague, a professor of copyright law here, said, “Does he know about the copyright issue of the songs?” The film uses old songs that were written and performed in the late 1920s. Had they been from 1923, they would be in public domain now. When they were written, they were supposed to be in public domain in the 1980s, but there have been these continuous, retroactive copyright extensions, so they may never enter the public domain.

We were so relieved that Roger agreed that what copyright law has become is really not serving culture or people. These copyright extensions have really gotten way out of control. [applause] They [inaudible] me so much that I actually question copyright fundamentally, but even those who don’t agree, I think, that retroactively assigning copyrights is not actually acting as an incentive for dead artists to create more art.

Whereas these songs. It’s a scandal, these beautiful songs! Many people have never heard of them until seeing my film. That’s just a crime. She was a huge seller in the twenties. Huge! Why is it that we can’t hear her music? It’s because all the rights are controlled by corporations, and anybody who dares to share Annette Hanshaw’s music is risking a lawsuit or jail. As I did. As I decided I was willing to do. I didn’t realize I was doing civil disobedience at the time. I didn’t realize how severe the possible punishments were for doing this kind of thing, but even had I know I would have done it anyway. I have no regrets. Now, I’m turning into a full-time free-culture activist. [applause]

Some of you may know my dad is a retired math professor here. But I grew up in this science and engineering culture. In all these books about copyright, people always talk about scientists and how scientists share information. How it’s really important, this really strong ethic of sharing information. Scientists seek to discover some really great information to share it with the community, and that actually benefits the contributing scientist.

As an artist, it’s actually exactly the same. My status vastly increases as I share this film. But I think it’s quite possible that the way I was growing up here formed me that way, to see it this way. A lot of artists don’t see it this way. People see it as property. I just wanted to share what I’ve been thinking about a lot. [applause]

RL: Has your film prompted an Annette Hanshaw revival?

NP: Not an official one. I should mention that the only reason that these songs exist in a form in which we can hear them at all is because of the efforts of underground record collectors, because the corporations that have the official rights to control this music hadn’t done it. They actually scrapped the masters. There’s no surviving masters of Annette Hanshaw’s recordings, because they were so very valuable that in the forties they were sent for scrap metal. And yet somehow it would be theft if somebody in America released her recordings today.

But yeah, there’s this wonderful network of record collectors who just preserved her stuff on lacquer, and that’s how I originally heard her songs. I was staying in the home of a record collector, and he actually had Annette Hanshaw on 78s. And this is the tip of the iceberg. There’s so much amazing culture that we’ve forgotten all about and can’t get at. There’s this wealth of films that’s just sitting there, that nobody can restore, because if you restore a film you don’t have the rights to, you can get sued for showing it! And it’s very expensive to restore films, so the result is, nobody wants to touch it. Everyone is scared, and our cinematic history is disintegrating. It doesn’t last. Records actually last longer than film.

KT: We should point out that you have a very informative website, ninapaley.com.

NP: Yeah, it’s now blog.ninapaley.com, and there’s also sitasingstheblues.com, and I’m also artist-in-residence at QuestionCopyright.org.

KT: Most of the ways to get the film out to people that you’ve talked about would be DVDs or downloaded copies, but your film is still being shown in a lot of festivals, well into the future.

NP: Yeah, festivals and also cinemas. Hurray for independent cinemas! I support them, and they support me. [applause] There’s some great cinemas programming it. It’s going to be in Chicago at the Gene Siskel Film Center, very soon. And it’s going to be in Vancouver. It’s going to be in some other cities. And there’s no real time limit. There’s no advertising for this film, no paid advertising. The audience is also the public-relations department, so it’s gone completely by word of mouth, word of web, word of blog. There’s absolutely no end time. It can be screened anytime. There are some prints circulating right now, and hopefully any cinema that has a little off time and wants to give it a shot, can program it.

KT: Your mother was telling me that the film will be probably in two hundred festivals.

NP: Not two hundred. I think it’s been in a hundred.

KT: Well, there’s a long list on your website that goes into 2010, I think, so [to audience] you want to tell your friends who live in those various cities, see it on the big screen!

[Note: the list of screenings and festivals on the film’s website numbered exactly 200 as of May 4.]

NP: When I decided to give it away free online, what finally made me realize this was viable was when I realized that this didn’t mean it wouldn’t be seen on the big screen, that the internet is not a replacement for a theater. It’s a complement. Many people will see it online and go, “Wow, I wish I could see this on the big screen!” And so they can, and some people like to see it more than once. Another thing is, you see it online, and that increases the demand for the DVDs. So it’s the opposite of what the record and movie industries say. Actually, the more shared something is, the more demand there is for it. [applause]

RL: Are you doing this for your short films, too?

NP: I would like it for the short films. It’s simply a matter of time. I want to do it with my comic strips. I’m still seeking a volunteer, although someone contacted me from the U[niversity] of I[llinois], I think from the library, whom I need to call. Maybe everything will be scanned and uploaded right here from Urbana, which would be awesome. But yeah, I want to go back. Just as Congress is retroactively extending copyrights, I’m retroactively de-copyrighting all of my stuff and sharing it, because that will make it more valuable. Imagine some original comic strip that everybody knows. That’s much more valuable to people than a comic strip that no one’s ever seen. Andy Warhol, for example. Some Warhol print just fetched some huge price at auction. There was a photo of it up in the newspaper. We all know what Andy Warhol’s prints look like, even though most of us have never seen them in the flesh. We all know that they’re worth a lot, ‘cause they’re famous. They’re famous because people reproduce images of them.

[People do indeed. Here’s another of Nina’s:]

Getting real

Art is not reality; one of the damned things is enough.

Attributed to Virginia Woolf, Gertrude Stein, and others.

DB here, with another followup to Ebertfest:

Ebertfest, once known as the Overlooked Film Festival, has always been keen to support American independent filmmaking. In previous incarnations, Roger spotlighted Junebug, Tarnation, and other movies that flew below the multiplex radar. This year’s crop was especially ripe. Besides The Fall and Sita Sings the Blues, there were important documentaries like Begging Naked and Trouble the Water. In particular, two fiction features set me thinking about types of independent storytelling and how they might be considered realistic.

The river is wide

Roger noted that when he first saw Frozen River, he wanted to bring it to his festival, but then it became the very opposite of an overlooked movie. It has grossed $4.3 million worldwide, a very healthy amount for a small-budget film without big stars. It won eleven national awards and was nominated for fourteen others, including a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. By now, you’ve probably seen it. I had been away during its Madison run, so I was happy to catch up with it.

“You have five minutes to show the audience you’re in charge,” commented director Courtney Hunt in the Q & A, and her film follows that advice. Seconds into Frozen River, we hit a crisis. Ray finds that her no-good husband has grabbed their savings and taken off to gamble, even as she waits for the delivery of their new prefab home. What begins as a drama of pursuit, with Ray trying to track down her husband, turns into a blocked situation. He’s gone and she has to not only pay off their mortgage but also keep her two sons going, counting on their school lunches to offset their domestic meals of popcorn and Tang.

Drama is about choices, and good drama is about bad choices. Ray has clearly made her share of mistakes—addictive mate, kids she can’t support, a bigscreen TV she can’t afford—and the plot shows her making the biggest of all. To scrape together money she agrees to transport illegal immigrants from Canada to upstate New York, driving across the frozen St. Lawrence. She casts her lot with Lila Littlewolf, a Native American with her own bad choices, and their common fate creates a series of parallels about motherhood that are resolved through Ray’s final sacrifice. The film also activates some current concerns about immigration, racism, and the problems shared by poor whites and ethnic minorities.

Resolutely unHollywood in its setting, theme, and characters—deglamorized women, especially—Frozen River still adheres to classical script structure. We have characters with goals, encountering obstacles and entering into conflicts, and the turning points come at the standard junctures. The ending is a resolution, although not an entirely happy one. In the course of the plot, suspense is built up at many points. Will Ray and Lila be caught by the state troopers who grimly monitor their comings and goings? What will become of that abandoned baby? The film is a sturdy example of how classic principles of construction can be applied to subject matter that is worlds away from our prototype of Hollywood filmmaking.

Neo-neo and all that

Ramin Bahrani’s Chop Shop, which I was also just catching up with, offers another flavor of independent dramaturgy. Roger has been a staunch supporter of Ramin’s films since Man Push Cart, and he has declared him “the new great American director.”

Bahrani has mastered a somewhat different narrative tradition than the crisis-driven plotting of Frozen River. “Neo-neorealism,” A. O. Scott has called it, linking Goodbye Solo to Wendy and Lucy, Treeless Mountain, Old Joy, and other films that offer us an “escape from escapism.” Now, Scott suggests, American cinema is having its delayed Neorealist moment. Richard Brody offers some useful, sometimes scornful, qualifications of Scott’s conjecture, reminding us of the urban dramas of the 1940s and the rise of Method acting. Scott has replied, claiming that their dispute essentially depends on their differing tastes in movies.

Here’s my $.02. “Neorealism” isn’t a cinematic essence floating from place to place and settling in when times demand it. The term, like the films it labels, emerged under particular circumstances, and it’s hard to transfer the label to other conditions. Moreover, there are many problems just with applying the term to Italian cinema, since it tends to cover not only the purest cases, like Bicycle Thieves, but also more mixed ones like the historical drama The Mill on the Po.

Still, because postwar Italian cinema had a big influence on other national cinemas, we have a prototype of The Italian Neorealist Movie. The filmmaker focuses on the lives of working people. He emphasizes their daily routines and travails. The film will be shot on location (at least in the exteriors) and may use nonactors in some or all roles. Bazin pointed out that we’re likely to find an elliptical or unresolved plot. It’s also very likely that we’ll see washlines and women in slips.

Why not just call this an Italian variant of that broad tradition of naturalism or verismo or “working-class realism” that we find in many national cinemas? In France there was the work of Andre Antoine (e.g., La Terre, 1921) and Jean Epstein’s Coeur fidele (1923) and his lyrical barge romance La Belle Nivernaise (1923). More famous are Renoir’s Toni (1935) and The Lower Depths (1936). (Recall that Visconti was Renoir’s assistant on A Day in the Country, 1936.) In Italy, there were harbingers too, not only the famous ones like Four Steps in the Clouds (1942) but also the charming Treno Popolare (1933). And Japan gave us many instances in the 1930s, notably Ozu’s Inn in Tokyo (1935) and The Only Son (1936).

Realer than real

On an Ebertfest panel Ramin Bahrani argued for a realist aesthetic. “Most people in movies never seem to pay rent or keep track of how often they can eat out . . . [Ordinary people] have day-to-day struggles; they ask how to survive.” That’s to say that a realistic work is distinguished primarily by its subject matter, the social milieu it presents. Bahrani also mentioned that some plot devices are unrealistic. Criticizing Slumdog Millionaire, he remarked: “My world doesn’t end in a Hollywood fantasy.” He didn’t deny the need for a dramatic structure, but he did insist on avoiding “obvious plot points like ‘He crossed the door and can’t go back.’”

This leads me to another $.02 contribution. I’m reluctant to contrast realism with something like artifice or formula. To me, realism comes in many varieties, but none escapes artifice. All realisms I know rely on conventions shaped by tradition.

For example, Chop Shop shows us a slice of life that most of us don’t know, the world of garages and salvage yards clustered around Shea Stadium. Such a low-end milieu is a convention of literary naturalism (Zola, Gorki). In this tradition, an artwork acknowledging the lives of the poor gains a dose of realism that, say, a novel by P. G. Wodehouse or a play by Noël Coward will lack. Some critics complained that when Rossellini’s Europa 51 and Voyage to Italy presented upper-class life, he left Neorealism behind.

There seem to me other conventions at work in Chop Shop. In one garage we find a boy, Alejandro, who has two goals. He wants to set up a food van that will sell meals to the men working in the neighborhood, and he wants to keep his sister Isamar safe from bad companions. Goal-driven plotting is central to Hollywood dramaturgy, as it is to much literary realism (e.g., An American Tragedy). It’s true that in real life people often form goals, but many do not, and those who do seldom come to a state of heightened awareness in the time frame typical of a movie’s plot. Alejandro fails to achieve one goal but partially achieves another, so we have an open, somewhat ambivalent ending—another convention of realist storytelling and modern cinema (especially after Neorealism). Life goes on, as we, and many movies, often say.

Instead of following a crisis structure, as Frozen River does, Chop Shop presents what we might call “threads of routine.” Most scenes consist of ordinary activities: the work of the garage, Alejandro’s sales of candy and DVDs, opening and closing the shop, Alejandro watching from the window of his room. But these vignettes aren’t sheer repetitions. They vary as Alejandro encounters progress or setbacks with respect to his goals. Most of the routines establish a backdrop against which moments of change and conflict will stand out.

Building a movie out of routines can also make convenient coincidences seem plausible. For instance, dramas have always relied on accidental discoveries of key information—the overheard conversation, the token that betrays what’s really happening. In Chop Shop, Ale and his pal Carlos discover that Isamar has become one of the hookers who service men in the cab of a tractor-trailer. They might have discovered this, as in life, by simply wandering by the spot on a single occasion. Instead, Bahrani’s script motivates their discovery by explaining that they habitually spy on the truck assignations. “Let’s go to the truck stop and see some whores.” Planting information in scenes of everyday activities seems more natural than giving it special emphasis at a moment of crisis. In two later scenes, the truck-stop becomes an arena for conflict, so Ale’s initial discovery motivates his later actions.

As for plot points, Chop Shop has them. (At about 15 minutes, the zone of the Inciting Incident, Ale declares his intention to buy the van. At about 30 minutes he discovers that Isamar is turning to prostitution.) Likewise, the threaded routines yield poetic motifs, such as the pigeons that are carefully established early in the film. Bahrani’s plotting is meticulous, and it highlights the paradox of realism: It takes effort and calculation to “capture reality.” De Sica was said to have endlessly rehearsed the boy in Bicycle Thieves.

What gives the film a more episodic organization than Frozen River, I think, and what gives it a greater sense of “dailiness,” is that it lacks deadlines. There’s relatively little time pressure on the action, except for Ale’s sense that he’s getting close to having enough money for the van. Chop Shop’s refusal of Hollywood’s ticking clock seems to me to confirm the observation, made by Geoff Andrew and J. J. Murphy, that in some respects American indie film is located midway between classical narrative cinema and “art cinema.”

The threads-of-routine pattern can be harnessed to character-driven drama, as in Chop Shop, but it can also be more opaque or minimalist. During at least half of Elia Suleiman’s Chronicle of a Disappearance, we watch anonymous characters go through routines, but instead of revealing their psychological drives, the scenes show the people overwhelmed by their surroundings. Narrative development is charted through changes in the spaces that the figures inhabit and vacate. The result is a “surreal realism” that evokes the anxieties of Magritte or de Chirico.

To say that realist traditions rely on conventions doesn’t make them less worthwhile. Chop Shops seems to me quite a good film. Nor would I deny that realist conventions do capture some aspects of real life. Both the crisis structure and the threads-of-routines structure can be taken as realistic. Sometimes our lives are in crisis, and at other times we do just plod along. But more stylized narrative forms can capture important aspects of reality too. The Searchers, a work of high artifice, renders a portrait of a self-destructive racist that many of us recognize in the world outside the movie house. Has any film better caught the adolescent yearning for romantic love and family stability than Meet Me in St. Louis?

The problem comes when we think that only one variant of realism can lay claim to validity, let alone beauty. Sometimes fidelity takes a back seat to vivacity. In Roy Andersson’s films, everyday nuisances like checking in to a plane flight or waiting in a clinic are inflated to grotesque, gargantuan proportions, becoming torments in a vision of hell. Like all caricatures, the exaggeration captures something true.

Comparing Wilkie Collins and Dickens, T. S. Eliot notes that both writers give us vivid characters. Collins’ characters are “painstakingly coherent and life-like,” terms of praise that we could assign to Bahrani’s films as well. But, Eliot adds, “Dickens’ characters are real because there is no one like them.”

What was Neorealism? Some of André Bazin’s invaluable essays on the subject can be found in What Is Cinema? vol. 2 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1971). Kristin and I offer a survey of some historical factors in Chapter 16 of Film History: An Introduction. (Go here for a little bibliography.) For more on art cinema and its commitments to realism and open endings, see my essay, “The Art Cinema as a Mode of Film Practice,” in Poetics of Cinema, 151-169. On American indies’ borrowing of art-cinema conventions, see Geoff King, American Independent Cinema (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2005) and J. J. Murphy, Me and You and Memento and Fargo (New York: Continuum, 2007). J.J. also has a blog entry on Chop Shop here. The quotations from T. S. Eliot come from “Wilkie Collins and Dickens,” Selected Essays (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1950), 410-411.

Songs from the Second Floor (Roy Andersson, 2000).

Virginia Theatre on our minds

Left to right: Kristin, unidentified ardent moviegoer, Erik Gunneson, and Meg Hamel.

Kristin here–

A year ago, those of us attending Roger Ebert‘s Film Festival were forced to do without the presence of the moving force at the center of this lively annual event. Still in therapy from his health crisis of 2005, Roger fell and broke his hip. Characteristically, he struggled to convince his doctors that he could take an ambulance to Champaign/Urbana, but their caution prevailed.

Since then, Roger has become ambulatory again, and this year he looked very happy to be back (an impression confirmed by his wrapup blog here). He still can’t talk, but he was a benign presence at the opening reception at the university president’s residence. There his wife Chaz took over the speaking duties, introducing the filmmakers and the critics who are this year’s guests.

Since then, Roger has become ambulatory again, and this year he looked very happy to be back (an impression confirmed by his wrapup blog here). He still can’t talk, but he was a benign presence at the opening reception at the university president’s residence. There his wife Chaz took over the speaking duties, introducing the filmmakers and the critics who are this year’s guests.

Roger went onstage at intervals during the festival, and he made his first appearance to introduce the opening night’s film, the director’s cut of Woodstock: 3 Days of Peace and Music (1970). Thanks to dedicated software, Roger tapped out messages on a laptop and pushed a button. A voice with a British accent conveyed his words of welcome to us and to director Michael Wadleigh. Then Roger retired to the back of the theater, where a comfy chair is reserved throughout the festival for him.

Michael Wadleigh, Jocko Marcellino, and Dale Bell discuss Woodstock.

From the perspective of nearly forty years, Woodstock has become both a record of remarkable musicians in their prime and a valuable document of the youth culture of the late 1960s. I was a junior at the University of Iowa at the time of the concert, only about five months away from taking my first film course and changing the direction of my education from tech theater to cinema studies. Working on props and make-up for productions every night, I was only dimly aware of the concert or the film that followed.

I also admit I don’t know much about pop music. I kept asking David “Who’s that?” Jefferson Airplane, The Who, Joe Cocker, and others were just names to me, not people whose appearance or music I recognized. But I could appreciate the remarkable way in which the filmmakers were able to capture live performances: the fluidity of multiple, 16mm cameras filming onstage only feet from the performers, the maintenance of focus even when events were recorded at night in less than ideal lighting conditions, and the excellent sound recording.

The screening heralds the release of the new version on DVD on June 9. Amazon has it on pre-order in 3-disc Blu-ray and DVD boxes, as well as a 2-disc set. The third disc has some making-of featurettes and about two hours of additional concert footage left out of even this extended version. I can’t imagine anyone who wants a compilation of performances by this remarkable group of musical talent settling for the smaller set.

Von Sternberg and Jannings, round one

The Alloy Orchestra has become a fixture at Ebertfest. This year’s silent film was Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command. I hadn’t seen it in thirty years or more, and it’s better than I remembered it being. Of course, seeing a gorgeous print on the big Virginia screen with an excellent musical accompaniment does it more justice than an old 16mm copy. Von Sternberg’s images were luminous, and his depiction of silent filmmaking as accurate as anything you’ll see on the screen.

In von Sternberg’s autobiography, Fun in a Chinese Laundry, he spends most of the six pages devoted to The Last Command badmouthing star Emil Jannings, with a brief sidetrack to badmouth William Powell. Presumably he’s talking about their behavior on the set, since their performances are both impressive, with Jannings emoting away and Powell as stone-faced as Buster Keaton. Von Sternberg reports that he and Jannings vowed never to work together again. Maybe winning the first Academy Award as best actor changed Jannings’ mind, for a few years later he invited von Sternberg to direct him and Marlene Dietrich in The Blue Angel. The rest, as they say, is history.

Drawing on their usual range of odd percussive objects, including a bedpan, the Alloy group provided a lively score. With Chicago Tribune critic Michael Phillips as moderator, Guy Maddin and I joined the orchestra members for a discussion afterwards. One of them hinted to me backstage that a score for Docks of New York might be in the offing, which would round off the von Sternberg series perfectly.

Saturday matinee

Last year the festival presented Tarsem Singh’s The Cell, with its delirious production design by Eiko. Tarsem’s 2008 follow-up, The Fall, got less attention in theatres, not having a star like Jennifer Lopez to carry it with audiences. It’s a complex fantasy set in a hospital during the silent-cinema era. There a suicidal, injured stuntman telling the tale of a band of mythical heroes bent on revenge to a seven-year-old girl with an arm cast. Her visions of the narrated events, set in spectacular landscapes and exotic buildings, mutate as she insists on changes in the story. The Fall was distinctly a crowd-pleaser, at least for the indefatigably enthusiastic audience in the Virginia Theater. Its Romanian child star, Catinca Untaru, is now twelve, and she proved an articulate charmer as she answered questions after the screening.

Ramin Bahrani with Catinca Untaru and her family.

The next film was Sita Sings the Blues, a marvelously imaginative animated feature by Nina Paley. I had seen the film two weeks earlier at the Wisconsin Film Festival, and it was a treat to see it on the big screen again. It’s available for download in various formats here. I had the pleasure of moderating the discussion afterward, and I like the film so much that I’ll be blogging on it separately, including a transcript of the Q&A.

Tattling and bullying

DB here:

A Belgian friend, the late Michel Apers, admired American films above all others. One of the reasons, he explained, was that our films analyzed our political system with uncommon clarity. No other national cinema, he claimed, focused so insistently on the mechanisms and purposes of government, on the duties of citizenship, and on the dilemmas of public life. Not wanting to seem too chauvinistic, I said that we often failed to fulfill our nation’s ideals. “Of course,” he said. “But at least you have ideals. And your films show that it is not easy to live up to them.”

Michel’s remarks reminded me that we do have a tradition of politically critical films: 1930s films opposing lynching and hate groups, 1940s films about political corruption, still later movies like Twelve Angry Men and The Best Man and The Manchurian Candidate. Directors who contributed to this tradition include John Ford (Young Mr. Lincoln, The Last Hurrah), Otto Preminger (Advise and Consent especially), and Alan J. Pakula (All the President’s Men, The Parallax View, Rollover, The Pelican Brief).

Rod Lurie’s favorite film is All the President’s Men, which ought to tell you where his heart is. He made The Contender (2000), a subtle drama about a woman nominated for Vice-President. It has the trappings of a political thriller (the conspiracy at its heart echoes Chappaquiddock, as well as Blow-Out), but that’s just the bait for its serious questions. Graced by a warm but steely performance by Joan Allen, The Contender asks whether a woman in politics is held to a higher standard of sexual conduct than a man would be.

I thought of Michel Apers’ remarks when I watched Lurie’s Nothing But the Truth (2008) at this year’s Ebertfest. The plot revolves around a reporter, Rachel Armstrong (Kate Beckinsale), who outs covert CIA agent Eric van Doren (Vera Farmiga, her of the admirably crooked smile). Rachel refuses to divulge her source and goes to jail. Again, there’s a mystery to draw us through the plot: Who is the source? But more important is the problem of whether a reporter should be forced to name sources in a case that breaches national security. It’s the sort of issue that Preminger or Pakula would have loved to tackle.

Lurie’s film is as close to a Shavian drama of ideas as I’ve seen in recent American movies. Patton Dubois (Matt Dillon), the prosecutor trying to worm the truth out of Rachel, has plenty of reasonable arguments on his side. During the post-film discussion, Dillon suggested that he leaned toward Dubois’ position: No one should have the power to destroy a person’s career in a sensitive job and go unpunished. In the film, Rachel’s lawyer Alan Burnside (Alan Alda) responds to Dubois with principled refutations, as well as a few pragmatic ones. After all, if Rachel is forced to talk, no whistle-blowers will be likely to step forward. See Roger’s recent review for more thoughts on the political implications.

Lurie’s film is as close to a Shavian drama of ideas as I’ve seen in recent American movies. Patton Dubois (Matt Dillon), the prosecutor trying to worm the truth out of Rachel, has plenty of reasonable arguments on his side. During the post-film discussion, Dillon suggested that he leaned toward Dubois’ position: No one should have the power to destroy a person’s career in a sensitive job and go unpunished. In the film, Rachel’s lawyer Alan Burnside (Alan Alda) responds to Dubois with principled refutations, as well as a few pragmatic ones. After all, if Rachel is forced to talk, no whistle-blowers will be likely to step forward. See Roger’s recent review for more thoughts on the political implications.

While the debate plays out, Rachel languishes in jail, her family and career dissolving. The case has some analogies to the Valerie Plame incident, but Lurie stressed that the film takes on a similar situation but not comparable characters. He was inspired as much by Susan McDougal’s tenacious loyalty to Bill Clinton.

The film’s secret about Rachel’s source is no mere Macguffin. It provides a powerful supplementary reason for Rachel’s silence, yet it doesn’t wholly excuse it. The film’s last scene leaves you wondering whether Rachel exploited her source. The film’s last shot suggests that she’s wondering too. That shot also wraps up a visual motif that hangs Rachel’s face on one extreme edge of the 2.40 frame, making her look precarious and vulnerable.

All in all, Nothing But the Truth is a sober, unsensational, gripping film about the press’s rights and obligations. It’s not surprising that Lurie was a professional journalist. During the Q & A, the questions were probing and he responded with rapid-fire, well-shaped sentences. There was good humor as well. After Lurie promised to tell us who slept with whom on the shoot, he paused and said: “All I’ll say is that Alan Alda was a complete slut.”

The opportunity for ordinary moviegoers to talk with such gifted and committed filmmakers makes Ebertfest one of the great film festivals on this continent. Roger’s urge to communicate with as many people as possible naturally inclines him toward creating communities, and the folks who gather annually in the Virginia Theatre form one of the most genial and generous group of movie lovers I’ve ever encountered.