Archive for the 'Festivals: Ebertfest' Category

Snapshots and soundbites

Boardman’s Art Theatre, two blocks from the Virginia Theatre, Champaign, Illinois.

DB here:

As you may surmise, a hell of a time was had by all at last week’s Ebertfest. In the sessions I moderated, I was often so busy listening and thinking about my next question that I didn’t have time to write down all the aperçus that spilled forth from the guests. But here are some soundbites, mixed with pix.

Jeff Nichols, director of Shotgun Stories: “I managed to make a 90-minute movie that feels 2 ½ hours long.”

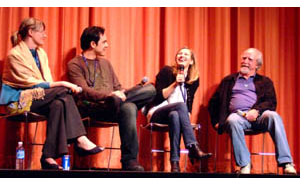

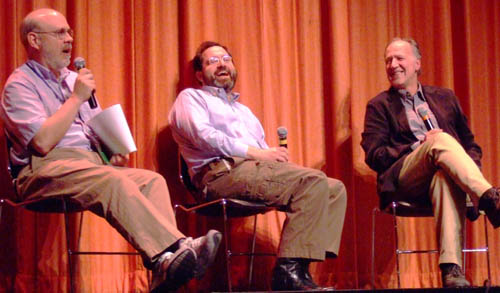

Jeff Nichols, John Peterson (The Real Dirt on Farmer John), Eran Kolirin (The Band’s Visit), Timothy Spall (Hamlet).

Bill Forsyth on his early work: “I made films about teenagers because they were cheap to hire.”

Christine Lahti (Swing Shift, Running on Empty, Jack & Bobby, Amerika) and Bill Forsyth, reunited for the screening of Housekeeping.

Why so much multiframe imagery in Hulk? “In those notes you get from studio people,” Ang Lee explained, “they always want more and faster. So I decided to give it to them.”

Ang Lee (Hulk) and unidentified admirer.

Barry Avrich asked Suzanne Pleshette how she had survived so long in the industry. Suzanne: “I don’t have a gag reflex.”

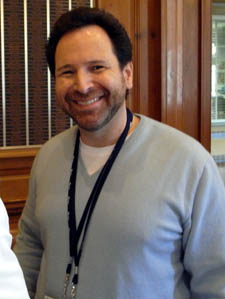

Barry Avrich (The Last Mogul, Satisfaction, Citizen Cohl: The Untold Story, and the book Selling the Sizzle).

Paul Schrader: Theatrical screening is dead. “The multiplexes look like mortuaries.”

Tom DiCillo: “Going to a film is a religious experience. . . . When you see it on a computer screen, fuck it.”

Tom DiCillo (Delirious) and Timothy Spall.

Paul Schrader: “When I started, there was a crisis of content. Nobody knew what a movie should be about. So we had films with sex and violence and anti-heroes. But now we have a crisis of form. How long should a movie be? How big should the screen be? What is this thing called movies?”

Paul Schrader (Mishima) and Hannah Fisher (Dubai International Film Festival).

“What part of this is directing?” Tom DiCillo, reflecting on the fact that it took six years to set up Delirious and he spent only 25 days behind the camera.

Tarsem Singh: “I’ve been an atheist since I was nine. I’ve never used any intoxicant—drugs or liquor or whatever. But I don’t like to associate with nondrinkers: they’re either religious or reformed alcoholics.”

Mary Corliss (Film Comment) and Richard Corliss (Time).

Joey Pantoliano (The Matrix, Memento, The Sopranos, Canvas, and book Who’s Sorry Now) with unidentified admirer.

Michael Barker (Sony Pictures Classics).

Eiko Ishioka: “When Paul asked me what I thought about Mishima, I said, ‘I don’t like him.’ He said, ‘Perfect!'”

Eiko Ishioka (Mishima, The Cell, The Fall), multimedia artist.

The Ebertfest Team

Chaz Ebert.

Mary Susan Britt.

James Bond, projectionist, and Nate Kohn, Festival Director.

See you here next year? Jim Emerson (scanners, Rogerebert.com) is counting the hours.

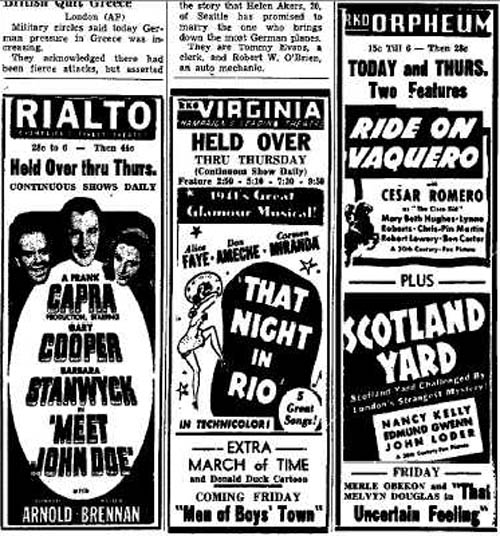

Bonus feature: What you would have been able to see in Urbana-Champaign 16 April 1941.

The show goes on

DB here:

Kristin and I had hoped to blog directly from this year’s edition of Ebertfest (formerly Roger Ebert’s Festival of Overlooked and Forgotten Films), but our blogging software failed us. We could post text but no pictures, and where’s the fun in that? Fortunately, the event was widely covered. The schedule, with very full film notes, is here. You can get a sense of what was happening by checking Jim Emerson at scanners and Peter Sobczynski at Hollywood Bitchslap and Kim Voynar at Cinematical and Lisa Rosman at A Broad View and P. L Kerpius at Scarlett Cinema and Andrew Wells at A Penny in the Well and many others. There is some coverage at the News Gazette, although the most informative stories from the paper aren’t on the net. Then there’s Roger’s own blog, Ebertfest in Exile, which in one entry goes off on an unexpected trajectory….toward Joe vs. the Volcano.

Now that we can again illustrate our entry, we offer you an ex post facto blog, like last year’s, which makes up in bulk for its tardiness. I hope to follow soon with a picture gallery.

This year’s Ebertfest lacked an essential ingredient: Roger Ebert. But Chaz Ebert took over hosting duties superbly, aided by the terrific organizational skills of Nate Kohn and Mary Susan Britt. At every screening, one person or another paid tribute to Roger’s gifts to film culture—his writing, of course, but also his tireless championing of deserving movies that should be brought to wider audiences.

The format of Ebertfest offers something for everyone. Traditionally, the opening night is an older film screened in classic 70mm, a format that’s almost vanished. Past years have included shows of Lawrence of Arabia, Play Time, and My Fair Lady. 70mm looks gorgeous on the vast screen of the Virginia Theatre. This year the film was Kenneth Branagh’s Hamlet, at four hours the most complete version of the play ever put on film. It looked grand.

Another slot is reserved for a silent movie, often accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra. (Part of their armory, including bells, springs, and a thunderstrip, can be found on the left.) Having programmed The Black Pirate, The General, and The Eagle in earlier years, Roger picked von Sternberg’s sumptuous Underworld (1927), which Kristin introduced and led a discussion about. The Alloy boys’ scores are getting more nuanced by the year, and this one did as much justice to von Sternberg’s quiet passages as to the gunplay.

Another slot is reserved for a silent movie, often accompanied by the Alloy Orchestra. (Part of their armory, including bells, springs, and a thunderstrip, can be found on the left.) Having programmed The Black Pirate, The General, and The Eagle in earlier years, Roger picked von Sternberg’s sumptuous Underworld (1927), which Kristin introduced and led a discussion about. The Alloy boys’ scores are getting more nuanced by the year, and this one did as much justice to von Sternberg’s quiet passages as to the gunplay.

Yet another Ebertfest mainstay is a children’s show on Saturday morning, and last year’s wonderful Holes was followed by an unexpected pick—Ang Lee’s Hulk, with the director in attendance. The place was packed, Lee was his charming self, a trio serenaded him, and the audience left well-pleased.

Prime spots are reserved for less-known films, with an emphasis on independent and personal cinema. We saw Tom DiCillo’s Delirious, Sally Potter’s Yes, Joe Greco’s Canvas, and Jeff Nichols’ Shotgun Stories. A highlight for me was Eran Kolirin’s The Band’s Visit, which I’d missed elsewhere. This unassuming, warm, funny movie recalled Tati and 1960s Czech films like Intimate Lighting. Then there was The Cell by Tarsim Singh at a late-night screening, with John Turturro’s Romance and Cigarettes to wrap things up on Sunday. For kaleidoscopic commentary on all these, see the above-mentioned weblogs.

Princely contradictions

I hadn’t seen Hamlet in 70mm in its initial 1996-1997 run, and at first the idea of taking this fairly intimate piece to a wide-film format seemed counterintuitive. But on the Virginia screen the film lost none of the play’s intensity and it gained a welcome monumentality. The central set, the Danish throne room as a gigantic hall of mirrors flanked by a warren of corridors and fissured by secret passageways, is made for the wide image.

Scale of time also matters. By playing the full version, Branagh can give full weight to the father/ son parallels that riddle the play. If Olivier’s Hamlet was about a son’s love for his mother, Branagh makes the play about the strife between fathers and sons, with women caught in the middle. Hamlet Sr./ Hamlet Jr., Claudius/ Hamlet, Jr., Polonius/ Laertes, old Norway/ Fortinbras, and even the Player’s speech about the murder of Priam: the parallels are in Shakespeare’s text but played out at proper length they snap into sharp relief. Once Laertes is off to Paris, Polonius makes sure he’s spied on, just as Claudius orders Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern to watch Hamlet. In his turn, Hamlet assigns Horatio surveillance duty during the play-within-a-play (a piece of action nicely caught in the opera glasses that Branagh’s choice of period allows). Branagh’s decision to emphasize the military politics around Fortinbras’ march into Denmark helps justify the 70mm format and his decision to set the action in late nineteenth-century Europe; it also allows him to expand, through crosscutting set up early in the movie, the plot of another son at odds with his father.

Sex is important in this game. Branagh presents flashbacks to Hamlet and Ophelia in bed together, accentuating the prince’s later indifference and motivating her despair at his rejection. Not that the fathers don’t clock some mattress time too. Claudius the urbane politician becomes an infatuated newlywed, and Derek Jacobi gives to my mind a definitive performance. Even Polonius, usually treated as a pompous ass, smokes worldly little cigars and has a drab tucked into his bed, so that his advice to Laertes and Ophelia about proper conduct becomes not only patronizing but hypocritical.

During the Q & A, Timothy Spall and Rufus Sewall emphasized something that Branagh explains on the DVD set: the need to create ensemble performances out of footage shot at different times. Sewall (a dark and scary Fortinbras) was filmed in a few days, before full-blown production, with his bits cut into the film at intervals. Robin Williams, as Osric, was also filmed out of continuity; there are scarcely any shots of him in the same frame as other players.

During the Q & A, Timothy Spall and Rufus Sewall emphasized something that Branagh explains on the DVD set: the need to create ensemble performances out of footage shot at different times. Sewall (a dark and scary Fortinbras) was filmed in a few days, before full-blown production, with his bits cut into the film at intervals. Robin Williams, as Osric, was also filmed out of continuity; there are scarcely any shots of him in the same frame as other players.

Spall, a temporizing Rosenkrantz, was present for much more of the filming and was eloquent in explaining how shooting in long, wheeling takes demanded great precision from the actors—hitting marks, using body language, and timing speeches carefully.

Branagh put the bulky 70mm camera on a dolly, then reinforced the studio floors so that no tracks or boards were necessary; the camera could glide anywhere. “Walk and talk” technique, which I’ve blogged about before, comes home to roost in a Shakespeare film; Branagh wanted continuous shots so that the audiences could follow the flow of the speeches, and it works very well.

In fact, Branagh’s editing varies in a patterned way across the play. Acts I and III are briskly cut, averaging about 5 seconds per shot. Acts II and IV rely on much longer takes, typified by the tracking-shot arabesques, and they average 10-11 seconds per shot. And Act V? Here, as you might expect, Branagh pushes the pace to suit the converging plotlines and the burst of poisonings at the climax: the average shot runs about 3 seconds. This seesawing rhythm helps sustain viewer interest across four hours, and it shows an unusually geometrical approach to a movie’s overall architecture.

In his program review, Roger points out that the play remains deeply mysterious, even in a production as lucid and buoyant as Branagh’s. Hamlet is of course one of the most fascinatingly inconsistent characters in literature. I’ve read the play probably a dozen times and seen many film versions of it, and I’m inclined to think that in Hamlet Shakespeare is experimenting with how indeterminate a character can be and still be intelligible to us. It’s not that he’s indecisive; we have to decide what he truly is, and Shakespeare makes our task very hard.

All the other characters in the play are complicated but consistent. Only Hamlet seems to reinvent himself at every entrance. He tells us that he will put on an “antic disposition,” but before he’s gotten very far with his fake madness, he tells Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern of his strategy, knowing that they are likely to report it to Claudius. This has the effect of letting Hamlet behave any way he wants, sincere or duplicitous, calculating or mad. When he’s around others, he’s always “on,” and this makes his true nature and purposes difficult to divine.

I liked Branagh’s idea of having Hamlet consulting a book on demonology, for in a revenge tragedy the protagonist has to be sure that the aggrieved spirit urging revenge isn’t a demon in disguise. More generally, the Victorian milieu lets Branagh give us a truly bookish Hamlet, one who retreats to his stuffed library when overcome by the strife unfolding in the vast throne room. At the same time, that library contains players’ masks and a curious miniature theatre that Hamlet toys with thoughtfully. He lives among books, but also among images of pretense and deceit.

I liked Branagh’s idea of having Hamlet consulting a book on demonology, for in a revenge tragedy the protagonist has to be sure that the aggrieved spirit urging revenge isn’t a demon in disguise. More generally, the Victorian milieu lets Branagh give us a truly bookish Hamlet, one who retreats to his stuffed library when overcome by the strife unfolding in the vast throne room. At the same time, that library contains players’ masks and a curious miniature theatre that Hamlet toys with thoughtfully. He lives among books, but also among images of pretense and deceit.

The questions tease you right to the end. Hamlet finds Laertes’ plunge into Ophelia’s grave overdramatic, but he goes on to declare that he himself loved her with the strength of forty brothers. Before the climactic duel, Hamlet apologizes to Laertes (“I have shot my arrow o’er the house/ And hurt my brother”), but it seems almost bad faith, given all the misery he has helped cause. Is this a morally obtuse sincerity, or another masquerade? It’s this Hamlet, reliably unpredictable, that Branagh’s manic-depressive performance brings home so forcefully.

The unwitting wisdom of the suits

It’s common to say now that the 1970s was the last great era in American cinema, followed by the degradations of the blockbuster 80s, but that remains little more than PR. Putting aside the “revolution” of the 1970s, which seems to me overrated, I’ll just offer the opinion that the 1980s brought us many worthy films, some of them quite daring. For example, one of the sweetest “little movies” of the era is Bill Forsyth’s Local Hero (1983).

It’s a comedy, at once dry and warm, about an oil executive sent to buy a small Scottish town and beachfront in preparation for the installation of a pumping rig and refinery. Forsyth’s script reverses the cliché. The townsfolk, far from clinging to their beloved tradition, are in fact anxious to sell and look forward to being rich. The young executive, Mac, doesn’t try to drive a hard bargain but settles into the rhythm of a life different from that he has known. His boss, a passionate amateur astronomer, surprises everyone with his final decision about the deal. You might call Local Hero one of the first films about the clash of global capitalism and community values, but though that’s accurate, the schematic formula doesn’t capture the understated humor and humanity of Forsyth’s treatment.

Forsyth is at Ebertfest for a screening of his no less brilliant Housekeeping; see Jim Emerson’s eloquent and poised review here. But I wanted to ask about Local Hero. The Scottish village is rendered with the affectionate good humor we find in Ealing comedies, and Forsyth mentioned that after he’d made the film he discovered an Alexander Mackendrick movie, The Maggie (1955), that prefigured his. For me, there were echoes of Jacques Tati in the long-shots and sound gags, and Forsyth confirmed that one of the formative films in his youth was M. Hulot’s Holiday, screened by an indulgent school head.

Forsyth talked about certain choices he made. The Mark Knopfler score, bringing together Scottish tunes and a Texas twang, helped open out the film in a way that a more conventional lyrical score would not. Forsythe talked as well about the final shot, one of the most satisfying I’ve ever seen. The original cut ended with Mac returning to his Houston apartment and staring out at the dark urban landscape—beautiful in its own way, but very different from the majesty of the Scottish shore. There the original film ended, but the Warners executives, although liking the film, wanted a more upbeat ending. Couldn’t the hero go back to Scotland and find happiness, you know, like in Brigadoon? They even offered money for a reshoot to provide a happy wrapup. Forsyth didn’t want that, of course, but he had less than a day to find an ending.

Forsyth talked about certain choices he made. The Mark Knopfler score, bringing together Scottish tunes and a Texas twang, helped open out the film in a way that a more conventional lyrical score would not. Forsythe talked as well about the final shot, one of the most satisfying I’ve ever seen. The original cut ended with Mac returning to his Houston apartment and staring out at the dark urban landscape—beautiful in its own way, but very different from the majesty of the Scottish shore. There the original film ended, but the Warners executives, although liking the film, wanted a more upbeat ending. Couldn’t the hero go back to Scotland and find happiness, you know, like in Brigadoon? They even offered money for a reshoot to provide a happy wrapup. Forsyth didn’t want that, of course, but he had less than a day to find an ending.

The movie makes a running gag of the red phone booth through which Mac communicates with Houston. Forsyth remembered that he had a tail-end of a long shot of the town, with the booth standing out sharply. He had just enough footage for a fairly lengthy shot. So he decided to end the film with that image, and he simply added the sound of the phone ringing.

With this ending, the audience gets to be smart and hopeful. We realize that our displaced local hero is phoning the town he loves, and perhaps he will announce his return. This final grace note provides a lilt that the grim ending would not. Sometimes, you want to thank the suits—not for their bloody-mindedness, but for the occasions when their formulaic demands give the filmmaker a chance to rediscover fresh and felicitous possibilities in the material.

Salvation through self-punishment

Another outstanding film of the 1980s is Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), which he brought to Ebertfest in a sparkling print. Schrader is one of two American film critics who became major directors (Peter Bogdanovich is the other), and there’s little doubt that he’s the most cerebral and theoretically inclined of that group known as the Movie Brats. Even if he hadn’t written milestone screenplays (Taxi Driver, Raging Bull) and made provocative films (Blue Collar, Hard Core, Affliction), he would be remembered for his critical writing. A trailblazing essay on Joseph H. Lewis, “Notes on Film Noir,” the essay on the yakuza film, and the book Transcendental Style in Film (1972) made Schrader a distinctive voice in American film culture. Fortunately you can now read his entire oeuvre online at paulschrader.org.

While the youthful Schrader expresses admiration for Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch, he’s no cheerleader for the New Hollywood. It’s bracing to watch him tear Easy Rider and Alice’s Restaurant limb from limb. The website displays each article in situ, on its original page of print. Since he wrote for many alternative weeklies, ads for bongs and day-glo paint lie alongside Schrader’s reflections on Bresson and Boetticher.

Although I also admire Patty Hearst, Mishima is my favorite Schrader-directed project. I think it’s one of the most artistically courageous films in American cinema. Putting the dialogue almost entirely in Japanese and focusing on a writer few Americans know, it compounds its difficulty with a daunting structure. On one axis, we get four chapters: Beauty, Art, Action, Harmony of Pen and Sword. On another axis, there are three interwoven strands: an account of the final day of Mishima’s life, when he seized control of a general’s office in order to address the garrison; a chronological biography, from his childhood to his adulthood; and stylized, efflorescent scenes taken from three Mishima novels. All these strands knot in the film’s final moments, when Mishima commits seppuku in the office and we see the culmination of the action shown in the novels’ tableaus. A “cross-hatched” structure, Schrader calls it.

The three strands are kept distinct through some technical markers: black and white for the biographical scenes, cinema-verite color for the 1970 attack on the garrison, and stylized color and setting for the extracts from the novels. Schrader explained that he had originally wanted to use video for the novel scenes, but his brilliant production designer Ishioka Eiko told him that the results might not be effective. Instead, she supplied designs of a dreamy radiance.

At the same time, both the biographical scenes and the tableaux take us through different eras of Japanese history, but in a way that sharpens comparisons among them. In the 1930s the boy Mishima glimpses a female impersonator at the kabuki theatre, but in his novel of the period, Runaway Horses, the young men formulate their plan to restore the emperor through an attack on corrupting capitalists. The sets for Kyoko’s House have, Eiko explained, ugly design because in the 1950s the Japanese were copying ugly American designs (though the results look pretty ravishing onscreen).

Schrader wanted to avoid the classic plot trajectory of a hero overcoming obstacles. He sought instead to present the way that a person’s life “becomes more and more fascinating, but you never really understand it.” The shuffling of chronology let him juxtapose different aspects of Mishima’s nature. The man wasn’t exactly contradictory, Schrader says, but rather “compartmentalized”: He could keep his aesthetics, his homosexuality, his militarism, and his childhood distinct, and the film aims to show these different facets of his career.

Nevertheless, I’d argue, the film has a marked trajectory. “Perfection of the life or of the art?” Yeats asked. Schrader’s Mishima wants both, together. He seeks to fuse physicality (eroticism, violence, endurance of pain) with spirituality (given as the realm of art). The emblematic image is the poem written in a splash of blood. He finally realizes that for him this fusion can come only in death, because his life has come to embody, literally incarnate, his literary themes and techniques.

Nevertheless, I’d argue, the film has a marked trajectory. “Perfection of the life or of the art?” Yeats asked. Schrader’s Mishima wants both, together. He seeks to fuse physicality (eroticism, violence, endurance of pain) with spirituality (given as the realm of art). The emblematic image is the poem written in a splash of blood. He finally realizes that for him this fusion can come only in death, because his life has come to embody, literally incarnate, his literary themes and techniques.

Schrader’s film enacts the blending of art and life in its very imagery. At the climax, in the biographical strand Mishima climbs into a jet and the black-and-white imagery gains radiant color as he stares into the sun. The shift brings the biography up to 1970, and so provides a transition to the color footage of the writer’s last day, but it also recalls the opening credits, with the sun rising, and the closing shot of the cadet Isao about to slash himself.

Schrader regrets the transition showing Isao running to the beach, because the imagery shifts from Ishioka’s stylized world to something more realistic (albeit with glowing amber rocks). So for the upcoming Criterion DVD release he has fiddled with the final shots so that the sun and sky look far more abstract. Evidently he wants the world of art and the world of life to remain stubbornly apart—denying to his film what his protagonist yearned for.

You might object that the film’s formal intricacy and specialized themes make for a fairly chilly experience. It isn’t a wildly emotional movie, that’s true; it has some of that ceremonial, contemplative quality you get from a Philip Glass opera, which provides a theatre of pictorial attitudes rather than action. (For an example, see coverage of the current Met production of Glass’s Satyagraha.) No coincidence that Glass provided the score for the film, which he wrote without seeing any footage and which Schrader cut and shuffled to provide cues. Glass obligingly rescored the film to fit the musical collage Schrader wanted.

The film provides a visceral and a sensuous experience, but it doesn’t carry you off on waves of emotion. It will never be popular on a massive scale, because it makes almost no concessions to what people like in biopics. But if you can adjust yourself to a solemn celebration of blood and beauty, Mishima offers unparalleled rewards.

More from Schrader

“Inspiration is just another word for problem-solving.”

Schrader’s intellect never lets up. What other filmmaker could produce such a thoroughly informed academic case as he does in the 2006 “Canon Fodder” (available on his site)? One on one, I peppered him with questions and he answered with seriousness and subtlety. Two themes ran through his comments: his approach to direction and his view that cinema is dead.

On his directing: Until his last project, he embraced the “well-made film.” He shoots with a single camera, and plans his takes cut to cut. (That is, not a lot of coverage from many angles that will be winnowed out during editing.) He doesn’t storyboard because he wants to develop the staging organically on site. He visits the set, tries out blocking with the actors and DP, then decides on the spot about the breakdown into shots. For the Temple of the Golden Pavilion scenes of Mishima, like the one above, he and cinematographer John Bailey played “dueling viewfinders,” pacing around the actors to test points of view and then settling on tracking shots which incorporated the best angles.

But for his latest project, Adam Resurrected (2008), Schrader switched to a rougher style. Now, he says, he uses two cameras and he likes the bouncing and swaying frame yielded by the Bungee Cam. “I’m sick of the well-made film.”

On new media: Schrader’s stylistic turnabout comes from his conviction that cinema, “the dominant art form of the twentieth century,” is coming to an end. Today’s audience demands new forms of moving-image media. Thanks to television, young people have seen every conceivable story, so narrative is “exhausted” as an expressive resource. They expect their media products to be free, available on demand, and interactive. The result is a challenge to traditional media on every front: financial, cultural, and artistic.

Schrader looks to the Internet as not just an intriguing option but film’s destiny. So while he is planning a traditional “three-act” film, he also has written a screenplay for a 75-minute Net movie. In his essay, “Canon Fodder,” he predicted the end of traditional cinema but thought that he could keep going before the revolution. Now, he says, the sun is setting faster than he expected and if he wants to make more films he has to adjust.

I’m no prophet, but I don’t share his beliefs about the imminent collapse of traditional cinema. I also think that Web-based films, with viewers tempted to browse and graze and fast-forward, will limit aesthetic options. The computer monitor is not as hospitable to contemplative cinema, which demands that the audience patiently submit to unfolding time. When I worried at a panel that an Ozu or a Bresson could not have originated in the age of YouTube, he told me, “Get over it, David!” Though we disagree, talking with him was terrifically stimulating. I left with the hunch that Schrader will continue to devise some characteristic provocations for new media, for which we should be thankful.

Envoi

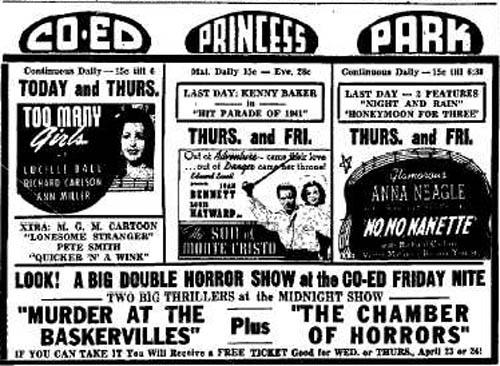

Dusty Cohl was one of the mainstays of Ebertfest, as well as the founder of the Toronto Film Festival and a shot in the arm to world film culture. He died last fall. He was honored by several events at this year’s festival, notably the biographical film, Citizen Cohl: The Untold Story, by Barry Averich (The Last Mogul). On my first visit to Ebertfest, the tough, salty guy with the quick grin and the cowboy hat immediately made me feel welcome, and he did the same when Kristin came along the following year. Everyone whose life he touched was grateful for Dusty’s generosity of mind and spirit.

1525 big thumbs up

Kristin here—

David and I just got back from Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival. It’s been held under the auspices of the University of Illinois, Roger’s alma mater, in late April for nine years now. This year the event was front-page news because our irrepressible host attended the event while recovering from surgery for salivary-gland cancer and complications last summer.

David and I just got back from Roger Ebert’s Overlooked Film Festival. It’s been held under the auspices of the University of Illinois, Roger’s alma mater, in late April for nine years now. This year the event was front-page news because our irrepressible host attended the event while recovering from surgery for salivary-gland cancer and complications last summer.

Roger’s features have changed somewhat and he faces further surgery and rehabilitation. Yet the man’s enthusiasm for movies and movie people has not waned. Most of the audience for Ebertfest (as it will officially be called starting next year) are regulars, and the standing ovations that greeted Roger and his wife Chaz show that the enthusiasm and affection are mutual. For more coverage, go here and here. For the official photoblog, with lots of neat pictures, go here.

If anything, Ebertfest audiences seemed even more cheerful and energetic than usual, happy that Roger has been so determined to avoid canceling this year’s event.

David and I have fond memories of Roger’s last visit to the Wisconsin Film Festival in 2006. There he introduced a restored print of Laura, held a signing at a local bookstore, and appeared at other screenings. People passing him on the street called out, “Hi, Roger,” as if he were an old friend. He graciously allowed me to interview him on the subject of press junkets for my chapter on marketing in The Frodo Franchise. There’s no way just to look up the history of junkets. No one has written one. But Roger is a primary document, having been attending them on and off since the 1960s. I learned a lot from our talk.

We drove down from Madison to Urbana-Champaign on Wednesday, David attending for the fourth year and I for the third. The opening film that evening was Gattaca (1997). With tepid reviews and box-office on its original release, Gattaca definitely counts as an overlooked film. Shown in an excellent print on the giant screen of the vintage Virginia movie palace, the cinematography was stunning and the story absorbing. Not an utter masterpiece, perhaps, but a very good film that deserved revival. As usual, people came from all over America to pack into the restored 1525-seat venue.

Now we’re back…and doing a summary blog. We had little time at the festival, and during our last day the web service at our lodgings conked out, so this stands as a fill-in.

Gattaca.

David’s two bits:

I saw ten films across three days and four nights.

The Virginia theatre did special justice to Gattaca. Writer-director Andrew Niccol used the anamorphic format imaginatively, a bit in the chilly manner of THX-1138, and the framings appeared to full effect on the 56-by-23-foot screen. This time I noticed how much the credit sequence, with only the G-A-T-C letters appearing first, owes to Godard. Like Alphaville, Gattaca uses not artificial sets but actual buildings to evoke the near future.

I thought that Moolade held up well on my second viewing, and the post-film discussion with the main performer Fatoumata Coulibaly (right) and Professor Samba Gadjigo was informative. The film’s call for an end to female genital mutilation is typical of Osmane Sembene’s use of controversial material; Professor Gadjigo recalled that Sembene calls his cinema a “night school” for Africa. Ms. Coulibaly said that in production “Papa Sembene” wouldn’t make eye contact with her, but before filming a painful sex scene he told her that she was “doing the scene for future generations.”

I thought that Moolade held up well on my second viewing, and the post-film discussion with the main performer Fatoumata Coulibaly (right) and Professor Samba Gadjigo was informative. The film’s call for an end to female genital mutilation is typical of Osmane Sembene’s use of controversial material; Professor Gadjigo recalled that Sembene calls his cinema a “night school” for Africa. Ms. Coulibaly said that in production “Papa Sembene” wouldn’t make eye contact with her, but before filming a painful sex scene he told her that she was “doing the scene for future generations.”

Sadie Thompson was still fine, I thought, with Walsh’s skill in cutting and staging exemplifying what Hollywood could do so easily in 1928. Swanson of course is tremendous in the role, using her whole body to tell the story of a woman who’s not as hard-edged as she makes out. The score by Joseph Turrin, conducted by Steve Larsen, was discreet and compelling.

La Dolce Vita seemed to me not to wear so well. I hadn’t seen it in at least twenty years, and its pacing and dramatic point-making appearing at once heavy and unfocused. Still, the film has that patented Fellini verve, and its daring fresco-like structure makes it a remarkable experiment in panoramic storytelling. It’s historically an enormously important film, and Jackie Reich illuminated it in our onstage discussion afterward. She has just published a book on Mastroianni’s career, Beyond the Latin Lover.

Of the items that were new to me:

The Weather Man took me by surprise, not only for its glum tone and antiheroic protagonist but also for its refusal of a tidy happy ending. Of Steve Conrad’s screenplay, Gil Bellows remarked that “one of the things that he can do is make you cringe for a character.” To his credit, Gore Verbinski, of Pirates of the Caribbean fame, found this uneasy domestic drama/ comedy a congenial project.

Come Early Morning by Joey Lauren Adams was a clear-eyed character study of an intelligent, flawed woman. Lacking villains and almost lacking heroes, it captures the rhythms of life in a small Arkansas town. Our protagonist, quietly efficient in her job, is caught in family and romance problems as she moves from man to man in a beery stupor. It was tactfully directed by Adams and graced by the underappreciated Ashley Judd. The Weather Man concludes with our hero facing us in close-up, but Come Early Morning ends with the protagonist turned away; in each case, the image feels right. On the left, Lisa Rosman, Eric Byler (Charlotte Sometimes), Joey Lauren Adams, and Scott Wilson (who plays the protagonist’s father).

Come Early Morning by Joey Lauren Adams was a clear-eyed character study of an intelligent, flawed woman. Lacking villains and almost lacking heroes, it captures the rhythms of life in a small Arkansas town. Our protagonist, quietly efficient in her job, is caught in family and romance problems as she moves from man to man in a beery stupor. It was tactfully directed by Adams and graced by the underappreciated Ashley Judd. The Weather Man concludes with our hero facing us in close-up, but Come Early Morning ends with the protagonist turned away; in each case, the image feels right. On the left, Lisa Rosman, Eric Byler (Charlotte Sometimes), Joey Lauren Adams, and Scott Wilson (who plays the protagonist’s father).

I must be the last person in North America to see Holes. Its tight plot, clever humor, and easygoing handling of racial matters endeared it to me. As in old Disney fare, familiar actors (Jon Voigt, Sigourney Weaver, Robin Wright Penn, Tim Blake Nelson) are willing to ham it up for the kids, with enjoyable results. And I was startled by the intricate flashback structure on offer; are kids now being trained to follow movies like 21 Grams? Given the interracial love story at the movie’s center, I had a new angle on what Walden Media might be contributing to modern Hollywood, something valuable that escapes cliches about “family-friendly” and “faith-based” entertainment.

Man of Flowers was a crowd-pleaser. I admired Paul Cox’s visuals, though the grainy print probably didn’t do justice to the range of dark tones in the original. An exercise in portraying a wealthy man’s obsessions and their sources in childhood, it moved toward Buñuel’s Archibaldo del Cruz, but it wasn’t prepared to be as lurid or delirious. A bit too dry and tasteful, perhaps. Still, I admire patient, unshowy long takes, and Man of Flowers is full of them. The photo above shows Paul reading a heartfelt tribute to Roger.

Perfume: The Story of a Murderer was much liked by the audience, and the presence of Alan Rickman made it all the more pungent. I wanted to like it more than I did. Despite my admiration for Tom Tykwer’s other films, particularly Winter Sleepers, The Princess and the Warrior, and Heaven, this one struck me as an overproduced Euro effort at a Big Movie. I thought it overdid the camera tricks (slow-mo, ramping) and the insistence on stuffing every shot with details (e.g., fish, cobwebbed glassware, glistening golden liquids). Above, you see the great actor with Festival Director Nate Kohn and entertainment analyst David Poland.

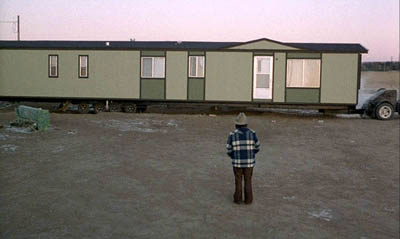

The simple and modest Stroszek was, for me, better at evoking smells—for instance, the stale smoke of the Himmel bar that our hero frequents. The print was faded and weatherbeaten, but the mysterious simplicity of this modern classic came through. The Wisconsin scenes, shot in Plainfield thirty years ago, wouldn’t need much changing today. As usual, I enjoyed the porous, unpredictable plot and Herzog’s willingness to dwell on unfathomable moments like a premature baby with powerful fingers (sleeping, he looks like a wrinkled alien) and the warped imagery of people passing a prison, seen through a hanging water bottle. The dancing chicken became one of the top screen icons of the 1970s.

Now for some quotes I like.

*Gattaca producer Michael Shamberg: “In the pilot scenes of Top Gun, Tom Cruise doesn’t wear his oxygen mask.” Ebertfest blogger Lisa Rosman: “It’s Scientology.”

*“None of the people I write about have friends.” Steven Conrad, screenwriter.

*“The US and Europe are my market. Africa is my public.” Osmane Sembene, quoted by Samba Gadjigo.

*Werner Herzog gave Roger Ebert an early alert about the importance of Anna Nicole Smith in American culture: “The poet must not avert his eyes.”

*“When I pray, I pray to Jesus.” Joey Lauren Adams.

*“Ambiguity in everyday life isn’t exactly celebrated in most movies. . . . It’s great when a big movie celebrates unnameable things.” Alan Rickman on Perfume.

*“Alan, be more subtle—do more.” Ang Lee to Alan Rickman, directing Sense and Sensibility.

*Why did Michael Wiese move to Penzance? “I was in a Witness Protec—oops.”

*“I’ve learned more about directing by working with bad directors than with good ones. And I’ve worked with a lot of bad directors.” Joey Lauren Adams.

*“Sometimes I think I’d like to join another species. . . . They seem to live a more sensible life.” Paul Cox.

*“Our technological civilization is not sustainable on this planet. Nature is going to regulate us very quickly. . . .We’ll be the next ones [to go extinct]. But that’s okay. Let’s enjoy movies and friendship and beer.” Werner Herzog.

*“I saw perhaps three or four films last year. I love cinema, but I’m not a cinephile.” Werner Herzog.

And some portraits of Ebertfest regulars:

First: Michael Wiese, filmmaker (Hardware Wars, The Sacred Sites of the Dalai Lamas) and publisher of outstanding books on the art and craft of film. Next, actor Scott Wilson (In Cold Blood, Junebug, The Host, and many more). Finally, Jim Emerson, who runs Roger’s website and writes fine film criticism at Scanners.

Each year, several guests receive an Ebert Thumb. This year, Kristin was one of the lucky ones.

Finally, here I am with Michael Barker, co-president of Sony Pictures Classics, and Werner Herzog. All I said was that I was from Wisconsin….

I plan to blog again soon about Roger and his contributions to filmmaking and film culture. For now, let me just echo Kristin’s opening point that his passion for film is exceeded only by his enjoyment of other people. This weekend’s gathering of top-rank filmmakers, young and old, and the enthusiastic audiences showed that he is probably the most deeply loved film critic whom we have ever had.

Cinema for cheeseheads

Meg Hamel introducing a film at the gigantic Orpheum Theatre.

DB here:

Today a chatty, catching-up blog filled with peekaboo links. Lots to do, know what I mean? Or do you?

Excuses, excuses

Kristin and I meant to blog about the Wisconsin Film Festival last weekend. We really did. But I missed the first night because my plane from Hong Kong got in late, and on Saturday I felt enough jetlag to mope around in a desultory fashion. I did see Fay Grim, Ten Canoes, Vanaja, and of course Johnnie To’s Exiled (better than ever on that CinemaScope Orpheum screen). Kristin saw several more films than I did, and that was part of the problem: She was too busy watching films to blog about them. By the time she finished, the festival was over and we faced some looming deadlines.

Regrettably, we simply let our festival blog go. Kristin drove off to Toledo for a conference of the American Research Council in Egypt. A fine conference it was too, but preparing for that took away some time for blog duties. To meet our Internets obligations, I pulled out a general essay that was sitting on the shelf. It turned out to be one of our most popular ever.

Over the same days I was occupied with two publishing projects. First is the online version of my 1988 book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available here. In the original book, the frames taken from color films were reproduced in black and white. Markus Nornes of the University of Michigan, who first suggested putting the book online, wanted to replace those with color frames. Since virtually all the book’s pictures came out poorly in the pdf scans posted online, we decided to replace the black-and-white images with scans from my original negatives. Kristi Gehring, our stalwart assistant, digitized all the black-and-white stills, and Markus found the color frames. So in the next few months the good folks at the University of Michigan should be replacing the tawdry stills with nicer ones. A bonus: Markus and his colleagues are working on giving the stills a click-to-enlarge feature.

Over the same days I was occupied with two publishing projects. First is the online version of my 1988 book Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, available here. In the original book, the frames taken from color films were reproduced in black and white. Markus Nornes of the University of Michigan, who first suggested putting the book online, wanted to replace those with color frames. Since virtually all the book’s pictures came out poorly in the pdf scans posted online, we decided to replace the black-and-white images with scans from my original negatives. Kristi Gehring, our stalwart assistant, digitized all the black-and-white stills, and Markus found the color frames. So in the next few months the good folks at the University of Michigan should be replacing the tawdry stills with nicer ones. A bonus: Markus and his colleagues are working on giving the stills a click-to-enlarge feature.

I’ll also be adding a new Foreword to the book. That will reflect on the book’s approach and its reception, and I’ll add corrections and new thoughts. In all, the updated online version should be available in late September. It’s been quite a struggle to revive the old thing, as I’ve chronicled earlier, but several people have taken a lot of trouble to help, and I’m grateful. Because, you see, I believe that Ozu is the greatest filmmaker who ever lived.

The second publishing project is my Poetics of Cinema collection. Delays, endemic in academic publishing, have pushed it past its spring release date. I’ve just gotten page proofs, and indexing should take place in August. So the thing is now slated for October. It’s rather big and expensive: 500 book pages, with about 500 stills. About half the essays are new to the volume. If you want to lay down your plastic before seeing it, you can order it here.

Coming attractions

At the moment we’re preparing for Roger Ebert’s Festival of Forgotten and Overlooked Films, which comes up later this week. Previous years’ sessions have been excellent. Alongside, you see a 2006 photo of Roger interviewing Ramin Bahrani and Ahman Razvi, director and principal actor of Man Push Cart. Ramin’s new film, Chop Shop, is now in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes.

At the moment we’re preparing for Roger Ebert’s Festival of Forgotten and Overlooked Films, which comes up later this week. Previous years’ sessions have been excellent. Alongside, you see a 2006 photo of Roger interviewing Ramin Bahrani and Ahman Razvi, director and principal actor of Man Push Cart. Ramin’s new film, Chop Shop, is now in the Directors’ Fortnight at Cannes.

This year should be lots of fun: a chance to meet Herzog, Alan Rickman, Joey Lauren Adams, and other creative film folk…and to see Roger and Chaz again. The films run the gamut from Holes to Beyond the Valley of the Dolls. Kristin and I will be moderating the screening of Sadie Thompson, with an orchestral score by Joseph Turrin. Another musical event: a performance by Strawberry Alarm Clock. (Now I do feel old.) We hope to post at least one blog, with pix of course. Other blogomanes will be present, notably the audacious David Poland and the hyperenergetic Jim Emerson.

Speaking of festivals: the biggest of them all is coming up, and to celebrate it Turner Classic Movies is running, on 16 May, Richard Schickel’s documentary Welcome to Cannes. It samples the glitz but also affords information about the caste system of screening passes, the role of Cannes in easing films into the world market, and even the harm that a Cannes prize can do to a director. There’s neat footage of Godard and Truffaut preparing to shut down the festival in May of 1968–an event that a couple of interviewees claim was a turning point in the festival’s history. Along with the docu, TCM will screen four Palme d’or nominees/winners: The Big Red One, Blowup, Taxi Driver, and Pale Rider. But one question remains: Why does nobody think of the French as cheeseheads like us?

When we get back to Madison from Ebertfest, we have just enough time to pack for a month in New Zealand. Brian Boyd has arranged for us to come as guest lecturers to the University of Auckland, under the auspices of the Hood Fellowship.

When we get back to Madison from Ebertfest, we have just enough time to pack for a month in New Zealand. Brian Boyd has arranged for us to come as guest lecturers to the University of Auckland, under the auspices of the Hood Fellowship.

Kristin will be lecturing mostly from her Lord of the Rings study, The Frodo Franchise (for instance, here), but she also offers a talk on her Amarna research. I’ve got a more varied agenda: talks on CinemaScope, on ShawScope, on the history of cinema style, on the cognitive approach to film theory, and on scene transitions, as well as a visit to the Philosophy department. One or more of these items may materialize as an essay on this site some day. We’ll also be visiting the University of Otago, in Dunedin, for a brief stay and a lecture apiece.

While dwelling among the Kiwis, I hope to write a short online essay reflecting on our 1985 book The Classical Hollywood Cinema, which amazingly still arouses some discussion. I’ll also be thinking about plans for two further books, one on Hong Kong cinema and the other on a new approach to film theory.

We’re planning to maintain our blog while we’re away, recounting our activities down under, and posting some more general pieces that I’ve already prepared.

Just butter, hold the popcorn

But what about our film festival just past? To be blunt: A hell of a time was had by all. We screened 182 films and attracted our biggest audience to date, with 28,700 tickets sold. Not bad for a festival that starts on Thursday night and ends on Sunday night, held in a town of about 240,000. Isthmus, our free arts-and-politics paper, offered an outstanding preview, and other local coverage was enthusiastic, natch. The event earned a glowing first-page write-up from Charlie Olsky in Indiewire. The official wrapup is here. For more on Madison cinephilia, go to our earlier entry.

We know whom to thank. Festival director Meg Hamel, The Boss of It All, is pictured at the top, channeling Judy Garland’s Palladium sessions. Technical supervisors Erik Gunneson and Jared Lewis are the calm and cheerful gents pictured below. We also owe a lot to Tom Yoshikami, Karin Kolb, Stew Fyfe, and a host of volunteers, as well as to several university agencies, notably the Department of Communication Arts and the International Institute.

With Sundance 608 opening in a couple of months, we might be able to spread next year’s fest between the downtown (cozy, near the students, lots of eateries) and the west side (the Borders-Whole Foods demographic). And with our University Cinematheque screening weekly, Madison film culture offers something for everybody.

Erik and Jared pay homage to the canted angles of Hartley’s Fay Grim.