Archive for the 'Festivals: Hong Kong' Category

The smoking section

Twenty Cigarettes.

DB here:

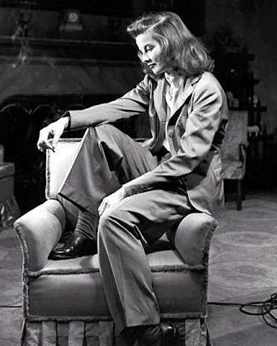

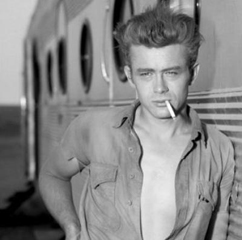

Reflect for a moment on the powerful role played by the cigarette in twentieth-century photographic portraiture. Before our recent worries about lung cancer, why were artists, movie stars, and other celebrities so often artfully posed with a tobacco product? Sometimes the imagery seems to evoke sophistication, presenting the subject as a man or woman of the world.

Or the portrait can suggest a relaxed, informal moment, a cigarette break.

That moment of relaxation can be extended to suggest contemplation or meditation, with the eyes gazing off into the middle distance. Despite the pretty face, this person is deep.

Alternatively, the cigarette can also suggest that painting or writing is a pretty casual affair. Smoking while working, the artist becomes an artisan. Maybe creating masterpieces is no more highfalutin than laying pipe.

And of course there’s the erotic side. A cigarette can make you look attractively dangerous.

In Golden Age studio portraiture, the smoke can become a compositional arabesque.

I’m not suggesting that James Benning set out to subvert this glamourous, stylized tradition in Twenty Cigarettes, which I caught at the Hong Kong Film Festival. But I think his film presents smoking as never seen before–defamiliarizing it, the Russian Formalist literary critics might say. And the movie’s not solely concerned with smoking. It resonates a bit with something I looked into in an earlier entry, on facial expressions in The Social Network. But here the film asks a different question: How expressionless can a face be?

Studied neutrality

A person in a medium shot smokes a cigarette. Repeat nineteen more times, showing smokers who suggest different ethnic and social identities. They are framed against outer walls, gardens, skies, or rooms. As in the Structural Film tradition, we witness an activity whose end is more or less known, and this forces us to study the minutiae of the process. But how much time the shot takes isn’t completely determined. Some smokers smoke faster than others, some shots run longer, and occasionally Benning halts the shot before the cigarette is quite finished.

In each shot, the smoker doesn’t talk and seldom looks at the camera. No one else is visible or audible (except, in one take, a voice distantly shouting, “Fuck you!”) Benning put himself out of sight during the filming of each take. By cutting the smokers off from all social intercourse, the film reminds us that it’s probably more usual for to people smoke while doing something else, like reading or watching TV or talking with friends. Benning forces us to watch the act of smoking in an almost artificially pure state. The film quickly becomes a study in smoking styles—quick non-inhalant puffs, luxuriant drags, little exhalations, slow streams curling out of nostrils. The ciggie is held tipped up in a dainty salute, or jammed between fingers. Solitary smoking becomes a sort of social-science experiment: If you can’t walk around, talk to others, window-shop, or whatever after you’ve lit up, how will you behave?

You’ll behave, Benning’s film suggests, by putting on the most blank expression possible. The portraits of artists and movie stars above use the cigarette to enhance the subject’s attitude–frankness, cool regard, disdain, pensiveness, intellectual seriousness. The cigarette, even the smoke, signifies. Nothing in the cigarette-portrait tradition prepares us for the almost frightening neutrality we see on the faces of Benning’s people. What are they thinking? Are they feeling anything?

It’s rather hard to maintain a poker face in a social interaction. Engaging with others, we spontaneously send signals of interest or mutual understanding, if only through raised eyebrows or a quick smile. But Benning’s lone smokers are eerily blank. Even what might seem to be an expression is often simply the person’s face at rest. (Some resting faces are read as non-neutral, as when an elderly person seems perpetually frowning or hangdog.) In the film, when the person’s expression changes, that’s usually because of the smoking; the twenty people squint or frown or tighten their jaw as they suck or exhale. For once facial movement is divorced from emotional signaling, and the result is a kind of anti-Shirin, Kiarostami’s portrait gallery of people caught up (apparently) in spontaneous bursts of emotion.

Benning’s film brings to mind the Warhol Screen Tests, and he has acknowledged the influence. Yet unlike Warhol, Benning gave his people the same specific task to execute. He’s like Hou Hsiao-hsien, who has explained that he got performances from his nonactors by letting them occupy themselves with eating and smoking. Warhol, as I recall, left things up to his performers, and so they might fiddle with props, run through a range of expressions, or simply stare innocently or challengingly at the camera. (To avoid reproduction rights problems, let me just send you here to sample some possibilities. On this page Nico the superstar seems herself to recreate the mystique of the classic studio portrait.)

Twenty Cigarettes yields something different from the Screen Tests I’ve seen. Using the cigarette as a constant feature, pulling smoking out of its usual place in our habits and social exchange, denying the tradition that shows smoking as connoting attitudes and emotions in people onscreen, Benning enables us to watch, across some ninety minutes, faces that aren’t dramatizing themselves or sending signals. No stars, these folks, let alone superstars. No narcissism either.

Yes, through dress and hair and demeanor we quickly characterize these men and women by type (housewife, hipster, working man). And each face carries marks of experience we can’t help but wonder about. At times I found myself looking for wrinkles and the other signs of smoking’s skin damage. And yes, the subjects know the camera is there, so to some extent they are posing themselves. Even granting all this, it seems to me that Twenty Cigarettes gives us a disconcertingly pure example of what happens when people make a tremendous effort to show as little of themselves as possible. We get to study what lived-in faces look like when they aren’t participating in social life but are aware that the camera is watching them.

Cigarette pictures, as if you didn’t know: Susan Sontag, Cary Grant, Louis Feuillade, Gary Cooper, Katharine Hepburn, Robert Rauschenberg, Jean-Luc Godard, Bette Davis, James Dean, Gary Cooper again, and Marlene Dietrich.

The website Celebrities with cigarettes includes many studio portraits. For examples from the Warhol Screen Tests, go here. On this page Nico the superstar seems herself to recreate the mystique of the classic studio portrait. Background on the making of Benning’s film can be found in this interview at Cinema Scope. On MUBI Neil Young provides a stimulating and painstaking analysis of Twenty Cigarettes.

Thanks to J. J. Murphy for discussions about Warhol, the subject of his forthcoming book, and of course to James Benning for his assistance.

Twenty Cigarettes.

Milkyway’s fine romance

Don’t Go Breaking My Heart.

DB here, from the Hong Kong Film Festival:

First, news. The Asian Film Awards, presented in a glitzy ceremony Monday, held some surprises. Confessions from Japan and Let the Bullets Fly from the Mainland (discussed in my previous entry), each had six nominations going in. But Confessions nabbed no prizes and Bullets won only for Best Costume Design, the award going to William Chang Suk-ping, probably best known as a versatile collaborator with Wong Kar-wai.

Best Picture winner was festival favorite Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, by Apichatpang Weerasethakul (right, in remarkable suit). The Best Director and Best Screenplay awards went to Lee Chang-dong for Poetry (which Kristin and I had liked very much at Vancouver). The winners are picked not by a mass of voters, as with the Oscars, but by a jury drawn from industry figures, critics, and festival executives. The first year’s awards in 2007 was dominated by the crowd-pleasing monster film The Host, which garnered four prizes, but this time two top honors went to arthouse/ festival titles. Still, it was very nice that local industry mainstay Sammo Hung got the Best Supporting Actor kudo for Ip Man 2.

Best Picture winner was festival favorite Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives, by Apichatpang Weerasethakul (right, in remarkable suit). The Best Director and Best Screenplay awards went to Lee Chang-dong for Poetry (which Kristin and I had liked very much at Vancouver). The winners are picked not by a mass of voters, as with the Oscars, but by a jury drawn from industry figures, critics, and festival executives. The first year’s awards in 2007 was dominated by the crowd-pleasing monster film The Host, which garnered four prizes, but this time two top honors went to arthouse/ festival titles. Still, it was very nice that local industry mainstay Sammo Hung got the Best Supporting Actor kudo for Ip Man 2.

As ever, there were special awards too: one to veteran Busan director Kim Dong-ho, one for Lifetime Achievement to Raymond Chow of Golden Harvest, one to Fortissimo Films for promotion of Asian cinema, and a prize to the top-grossing Asian film. That last was one of the three that went to Feng Xiaogang’s Aftershock (which we wrote about here). For a full listing go here. At Filmbiz Asia Patrick Frater suggests that the catastrophe in Japan gave the ceremony a sombre cast.

Milkyway on the move

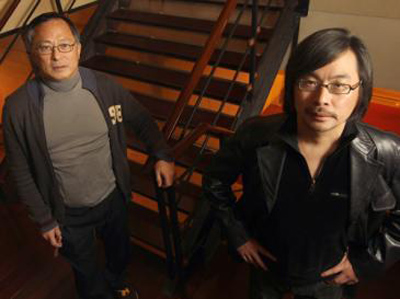

Source: South China Morning Post.

When I arrived last week, I was greeted by a long story in the South China Morning Post announcing that Johnnie To Kei-fung and Wai Ka-fai (above), the movers behind Milkyway films, were embarking on a new production strategy.

Although Milkyway movies had cracked the mainland Chinese market in the past, notably with Breaking News (2004), To had made several films that could not be exported. His most personal films, crime stories like The Mission and PTU, violated the PRC’s demands that movies treat the police with respect. Worse, his Election films, which surveyed the treacherous power plays at work in Triad societies, was unthinkable as an export item–especially since the second entry extended its vision to the role played by PRC forces in controlling the Hong Kong crime scene.

Today, however, everyone acknowledges that the primary market for any Hong Kong film with a substantial budget is the mainland. In the SCMP story To and Wai announce their plans to craft a cycle of films for that audience. Romantic comedies and dramas have shown strong legs there, and true to their prolific energies, To and Wai have committed to making three romances this year. The first, Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, opened the festival on Sunday night. To is currently shooting the next one on the Mainland, and the third is set up to follow quickly.

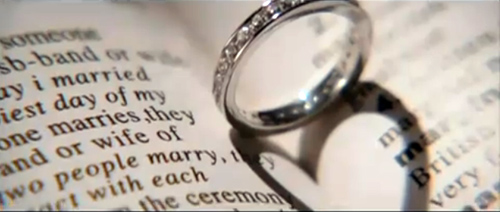

Don’t Go Breaking My Heart, which is better than the Kiki Dee/ Elton John song, is an office romance like Milkyway’s 2000 hit , Needing You. . . . But the creators have deliberately updated the milieu, which includes not only a mainland émigrée as the heroine but also many scenes shot in China, as required by the financing.

The action starts just before the 2008 financial crisis. Cheng Zixin (a charming Gao Yuanyuan) is a lowly staffer at an investment company, while Cheung Sun-yin (Louis Koo) is an executive at a rival firm who first spies her from his sportscar. Noticing that Zixin occupies a cubicle by the window in a building adjacent to his, the ingratiating rascal begins flirting with her through pantomime. The third corner of the triangle is Fong Kai-wang (Daniel Wu), an architect turned alcoholic bum. The affair between Zixin and Sun-yin falls apart because of his attraction to other women, and she develops a platonic affection for Kai-wang, whom she urges to return to his profession. Three years later, as the financial sector is recovering, the three meet on more equal terms and Kai-wang and Sun-yin begin a serious competition for the young woman.

The financial crisis is no more than a pretext for the meet-cutes, handy coincidences, running gags, and emotional ups and downs characteristic of this genre. (One hopes that the recession gets more sober treatment in To’s long-gestating bank suspense drama, currently known as Life without Principle.) We get the common tension between the world of selfish business operations and that of nobler artistic expression, seen in Kai-wang’s love-inspired architectural designs. There’s also the convention, common to Asian romances, that these grown-up lovers are actually childlike, enjoying pets and stuffed animals. (You find it even in Chungking Express.) Don’t Go Breaking My Heart handles these conventions adroitly, but adds the To/ Wai flavor in its plot geometry and its strict but surprising ways with visual technique.

An American movie would have added subsidiary romances, usually involving the friends of the main characters. Instead, as in many Milkyway films, Wai’s plot is built out of rhyming situations. Sun-yin twice glimpses Zixin on a bus, both suitors use Post-Its and magic acts to attract her attention, characters’ zones of knowledge shift symmetrically, and an engagement ring pops up unexpectedly. Most remarkably, much of the courtship is carried on through skyscraper windows, as the men communicate with Zixin across adjacent buildings.

This last strategy allows To to build wordless sequences that rely on precise point-of-view cutting. At key moments, reverse-shot breakdown yields to striking compositions of the anamorphic frame. First we get two characters framed in different windows, but eventually, when Kai-wang tries to win Zixin away from Sun-yin, the love triangle finds diagrammatic expression in a spread-out three-shot.

Were shots like these accomplished through CGI? I wouldn’t put it past To to set up a location-based shot like this.

While subjecting its love story to a playful rigor that few Hollywood directors could summon up, Don’t Go Breaking My Heart never dissipates its inherent appeal to our emotions. Those emotions are all the stronger because Wai’s script shrewdly puts the outcome in doubt. The movie is a second-tier Milkyway product, I guess, and I could do with one less twist in its rather long running time. But it’s still a treat. It shows that in a popular cinema, creative minds can turn market demands to their own ends. And once the trio of romances is finished, the SCMP story hints, To and Wai may well turn to another crime saga, this time with the blessing of the PRC. We can only hope.

Wai Ka-fai, writer/ producer/ director of many Milkyway projects, is the subject of this year’s HKIFF Filmmaker in Focus cycle. Several of his older films, including the engaging parallel-worlds yarn Too Many Ways to Be No. 1, are in the program. There is, as usual, an informative book about Wai and To; a pdf sampler is here.

For much more on Milkyway on this site, go here. Ad insert: Films from the company, particularly those directed by To, are discussed in my new edition of Planet Hong Kong, available here.

PS 23 March: Thanks to Sean Axmaker for correcting my aging memory. The original entry attributed the song Don’t Go Breaking My Heart to the Captain and Tennille. Maybe I was subliminally wanting to see them again. No, wait, that can’t be it.

The target: Young mainland viewers of Avatar, China’s biggest box-office hit of 2010.

Bullets from the East

Chow Yun-fat, Jiang Wen, and Ge You in Let the Bullets Fly (2010).

DB here:

It’s mid-March, so it must be the first of a string of entries from the Hong Kong International Film Festival, a place I’ve visited regularly since 1995.

This year, the Boy Scout hotel was too full to take me, so I’ve wound up in the YMCA on Salisbury Road. If you want glimpses of the neighborhood, just watch Peter Greenaway’s Pillow Book. It’s as if he ventured only a few blocks from his hotel. (Unlikely to have been my Y; more likely he based himself at the far tonier Peninsula alongside.)

The Japanese quake, tsunami, and nuclear meltdowns are much on local people’s minds. Some people are worried that the light rains punctuating every day are carrying radiation, but so far there doesn’t seem any danger. I had planned to stop over in Tokyo on my way here, but after the quake struck I changed my flights. The good news is that the friends in Tokyo and Nagoya I’d planned to visit are safe.

Let the Bullets Fly, China’s biggest locally produced box-office hit to date was playing in a cycle of screenings devoted to major candidates for the Asian Film Awards, to be given Monday night. It was screened in the Grand cinema complex with Shaw Sound, which makes your seat vibrate in sync with the lower frequencies. This enhances any movie, I suppose. The Grand is located in Elements, a hypermall that has lost none of its weirdness. (The mazelike structure has four zones, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.) I was pleased to note that the Grease Trap Room is still doing its duty.

Let the Bullets Fly, China’s biggest locally produced box-office hit to date was playing in a cycle of screenings devoted to major candidates for the Asian Film Awards, to be given Monday night. It was screened in the Grand cinema complex with Shaw Sound, which makes your seat vibrate in sync with the lower frequencies. This enhances any movie, I suppose. The Grand is located in Elements, a hypermall that has lost none of its weirdness. (The mazelike structure has four zones, Earth, Air, Fire, and Water.) I was pleased to note that the Grease Trap Room is still doing its duty.

Actor-turned-director Jiang Wen is one of the PRC’s most ambitious and intelligent directors. I’ve admired his In the Heat of the Sun (1994) and Devils on the Doorstep (2000, to be shown in its long version during the festival). Our blog files contain my impressions of his sumptuous, somewhat mystifying The Sun Also Rises (2007). But that film was a huge financial failure, and it’s generally agreed that he needed a hit. He provided it in Let the Bullets Fly.

This wild, cynical Eastern Western is set, the opening title tells us, in 1920 when warlords ruled great stretches of China. By choosing this pre-Communist era, Jiang is free to parade all manner of duplicity, amorality, and aggression, while still suggesting a modicum of revolutionary sensibility at the end. Pocky Zhang leads a band of marauders who capture a conman, Ma, and his wife. Ma’s swindle of choice is bribing officials to appoint him governor of a remote area and then squeezing taxes out of the locals before fleeing to his next target.

Captured, Ma pretends to be merely an advisor to the real governor, whom he claims was killed during the raid. Bandit Zhang decides to try his hand at governing and so brings his gang, along with Ma and his wife, to claim the post at Goose Town. There he butts heads with the local gang leader Huang Silang. The bulk of the plot presents an escalating series of comic and violent encounters between bandit-as-governor and warlord-as-godfather. Things come to a head when Huang offers Pocky Zhang a huge sum of silver to kill the biggest threat to his rule, none other than Pocky Zhang himself.

The beginning evokes Duck You Sucker, plunging us into Pocky’s raid on a steam train carriage (pulled by horses). As his gang races along with the carriage, we get the tone of lilting swagger that opened The Sun Also Rises. Very fast cutting, rushing tracking shots, and a bouncy musical score climax in Pocky’s adroit use of a flying axe to derail the carriage and send it flipping majestically into the river. Soon the bravado action gives way to games of deceit and disguise. Ma saves his skin by pretending to be his aide Tang. Pocky assumes the identity of the governor, while Huang has an identical double he will use as a decoy. Everybody suspects, rightly, that everybody else is lying. Even Pocky Zhang isn’t really pock-faced. (An alternate translation calls him Scarface Zhang. But he isn’t scarfaced either.)

The game is played out in fusillades of banter that are, my Chinese friends assure me, packed with gags and wordplay. Maybe it should be called Let the Bullshit Fly. Characters rattle out brief lines or single words in a thrumming rhythm that is underscored by frantic back-and-forth cutting: cinematic stichomythia. Overall, the film’s average shot length is about two seconds.

Let the Bullets Fly is a showcase for action scenes, dizzying dialogue, clever running gags (the bird-whistles that Zhang’s gang uses to communicate), and perhaps above all star performances. Three popular male actors dominate the proceedings, leaving poor Carina Lau as Ma’s wife little to do but look seductive and die early on. Ge You as Ma is querulous but cunning. Ma’s death, buried in a mountain of silver currency, balances exaggerated imagery and gory gags with a gentler humor as he tries to utter some last words. Chow Yun-fat hams it up agreeably in a dual role, as gangster Huang and his hapless, nattering double.

Central of course is Jiang himself as Pocky Zhang, a crack shot and an utterly confident, resourceful leader who spares a little time to eye the ladies. Director supremo Feng Xiaogang shows up in the prologue playing the unfortunate counselor Tang. His drowning in the train carriage carries a peculiar extra-filmic resonance: by the end of its run, Bullets broke the box-office record set by Feng’s Aftershock earlier in the year.

More generally, the film shows how filmmakers on the mainland are broadening and fine-tuning popular genres. Having mastered the costume epic, they have branched out, winning audiences with modernized comedies and relationship romances (e.g., Feng’s recent If You Are the One films). So why not Westerns too? After all, the genre has been transplanted to Italy, Germany, Spain, and even, some would say, Russia and India. Hong Kong’s Peace Hotel and South Korea’s The Good, the Bad, and the Weird showed that frontier conventions could be adapted for Asian audiences. Let the Bullets Fly seems to me not up to Jiang’s best work, and on one viewing, I found it occasionally monotonous and mechanical. Still, it should underwrite his more ambitious projects and encourage other directors to try their hands at a format that seems inexhaustible.

Thanks to Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to for sharing ideas over dim sum, and Shelly Kraicer for further clarification of names. For informative reviews of Bullets, see Ross Chen’s entry at lovehkfilm.com; James Marsh’s at twitchfilm; and Derek Elley’s commentary at Film Business Asia. This PRC review, in English, faults Jiang for his “unduly high opinion of himself.”

Speaking of Hong Kong: In case you didn’t know, the second, digital edition of my book Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment, is available here. Brace yourself for reports on my shameless efforts to hawk this item as the festival proceeds.

PS 21 March: Thanks to Luo Jin for a name and date correction.

A point of pilgrimage for every Hong Kong-addled cinephile: Chungking Mansions, on Nathan Road. You can see bamboo scaffolding on the left side.

PLANET HONG KONG: One more visit

Hong Kong, Central, April 2008.

DB here:

Planet Hong Kong, in a second edition, is now available as a pdf file. It can be ordered on this page, which gives more information about the new version and reprints the 2000 Preface. I take this opportunity to thank Meg Hamel, who edited and designed the book and put it online.

As a sort of celebration, for a short while I’ll run daily entries about Hong Kong cinema. These go beyond the book in dealing with things I didn’t have time or inclination to raise in the text. The first one, listing around 25 HK classics, is here. The second, a quick overview of the decline of the industry, is here. The third discusses principles of HK action cinema here. A fourth, a portfolio of photos of Hong Kong stars, is here. That was followed by a tribute to western Hong Kong fans and then by a photo gallery of directors. Today’s installment is the last. Thanks to Kristin for stepping aside and postponing her entry on 3D, which will appear later this week.

Since the 1980s, the film festival circuit has become the only distribution system to rival Hollywood’s global reach. A big-name festival publicizes a film, some high-end critics at the festival write reviews, then once the film opens in a region or country, critics at large review it. As smaller festivals pick up films from the bigger ones, until eventually films make their way to small cities around the world. This process is parallel to the one that the studios orchestrate, though they have more centralized control. Video distribution, the circulation of DVD screeners, and Internet reviewing complicate this picture, but I don’t think they change the essential role of the festival network.

Just as film scholars have started to pay attention to fandom (see this post), they’ve started to ask research questions about festivals. As very few films from overseas find their way to U. S. screens, scholars keen on current cinema have realized that they need to visit festivals. It’s like scholars of painting traveling to exhibitions and gallery shows, or opera aficionados attending premieres at Bayreuth and La Scala. And film scholars of certain genres or periods have realized that they can do on-the-fly research by visiting historically oriented festivals like Pordenone and Bologna.

These days I see more of my colleagues at various festivals. In particular there’s the peripatetic Bérénice Reynaud, an early example of the multitasker (critic, programmer, professor, fan). On the same circuit I meet Virginia Wright Wexman, Peter Rist, Mike Walsh, Jim Udden, Gary Bettinson, and many other profs. So I’m starting to think that festivals are giving academic film studies a fresh charge of energy. Reciprocally, the events at Pordenone and Bologna, which began as cinephile events, have invited academic researchers to help program them and write for their publications. In sum, festivals are now a vigorous workspace for not just screenings and critical write-ups but discussions about ideas that would normally haunt the groves (or is it grooves?) of academe.

Saturation booking

Athena Tsui and Li Cheuk-to. Hong Kong, 2000.

I had dropped in at screenings at the New York and London film festivals in the 1970s and 1980s, and I had steadily attended the summer Cinédécouvertes series in Brussels. But I had never “done” a festival intensively until I went to Hong Kong in the spring of 1995. There I saw films that still stay with me: Through the Olive Trees, Postman, In the Heat of the Sun, A Borrowed Life, Smoking/ No Smoking, Quiet Days of the Firemen, Taebek Mountains, 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance, Whispering Pages, and Clean, Shaven. (My one big miss was Sátántangó; I had to wait years to catch up with that.) Who says the 1990s were a meager decade? Can any festival today come up with a menu like this?

I had gone, as I explain in the Preface to Planet Hong Kong, mainly to check on local cinema. The “Hong Kong Panorama” surveying 1994 releases yielded a bumper crop, including some titles I’d seen only on laserdisc (Chungking Express, Ashes of Time) and others that were revelations. Above all, there was a retrospective—an entire festival in itself, really—dedicated to early Chinese and Hong Kong cinema. They swept over me in a heaving wave: Love and Duty (1932), The Eight Hundred Heroes (1938), Boundless Future (1941), and many others, along with postwar Hong Kong classics like Where Is My Darling? (1947), Song of a Songstress (1948), The Kid (1950), with Bruce Lee, and on and on. The series was capped by stunning restored Technicolor prints of The Orphan (1960), also with Bruce, and General Kwan Seduced by Due Sim under Moonlight (1956). Some of these had circulated on poor VHS copies, but most were, and still are, unknown in the West.

I had picked the perfect year to come to the festival. Looking back at the notes I scribbled in the dark, I realize that over three weeks I got a crash course in Chinese film history. In any given day I was given more to think about, and certainly more to feel about, than I got from almost any academic conference.

For those of us interested in non-Hollywood cinema, festival programmers and critics are central gatekeepers. They scout the ridge and scan the horizon, and around the campfire they teach us film lore. They’ve built up fingertip knowledge about movies, moviemakers, distribution patterns, sales agents, theatre circuits—in sum, the workings of world film culture. The best of these gatekeepers are intellectuals, ready to search out something stimulating in even the most marginal film. They have honed their senses to detect qualities that could provoke an audience or yield a lively Q & A or a piquant catalogue entry or a solid review. Out of pure selfishness, I wish I could download the neural storage files of Alissa Simon, Richard Peña, Tony Rayns, Cameron Bailey, and their peers. Alas, there is no app for that.

In Hong Kong I met Li Cheuk-to, Jacob Wong, Freddie Wong, and many other programmers, along with Athena Tsui and Shu Kei. What made my experience that spring of 1995 so thrilling were their months of patient planning and sleepless nights behind the scenes—finding the prints, arranging for them, writing catalogue copy and, not least, assembling a massive reference work like Early Images of Hong Kong & China, one of the precious books the festival managed to turn out every year to document the local cinema.

Many programmers are also critics, and such was the case in Hong Kong. When I arrived, Cheuk-to and his colleagues had just formed the Hong Kong Film Critics Society, and I was invited to their first awards ceremony. They were mostly young, and after the awards were handed out I was invited out to dinner with several of them. It was then I realized that here was a local film culture in which criticism mattered. Hong Kong was small enough for critics to band together to debate their cinema. Soon another critics’ group was founded, and the debates spread. I started to understand that if one were to study a film culture, one would have to grasp the dynamics of taste among schools of critics and between critics and their audiences. I made an effort to describe this dynamic in the second chapter of Planet Hong Kong.

It’s not just that that book had its origins in that first visit. And it’s not just that the newest edition is the result of my attending the festival for the last fifteen years. More important, my ideas about film and about the world changed when I met critics, programmers, and other academics in Hong Kong. Immersion in one of the world’s most fascinating cities had something to do with it too.

Favorites, for now

As Tears Go By (1988).

In my first entry in this hurriedly posted series, I listed around 25 Hong Kong films that most aficionados consider of major importance—historical, artistic, cultural, or all three. In the days since, I’ve mentioned several other films that you can check into. Here, as an envoi to this yakathon, are a few more movies that I’ve repeatedly enjoyed, and that I’ve sometimes talked about in PHK 2. They’re grouped in very loose categories.

Lesser-known items from major directors. Once a Thief is a good example. Sandwiched between Woo’s official classics is this good-natured, somewhat silly action comedy about art thieves, romance, and parenthood. Lifeline is one of my favorite Johnnie To Kei-fung films—not as formally audacious as his later masterpieces, but containing one of cinema’s great action sequences involving a fire that seems as unstoppable as a waterfall, with the bonus of a throat-catching epilogue. Ann Hui On-wah’s Summer Snow, about a busy career woman who must treat her Alzheimer’s-affected father, glows with the intimate realism and understated sentiment that inform her more recent The Way We Are.

Everybody knows some works by Wong Kar-wai, but I think his later accomplishments have overshadowed his debut, As Tears Go By, a prototype of the arty gangster movie. Drenched in romanticism, it has one of the great music montages in Hong Kong film and a finale that you feel lifting from genre formula to pictorial poetry. With Johnnie To as well, even offbeat items like Throw Down are getting well-known, but I’d like to make a pitch for the New Year’s mahjong comedy Fat Choi Spirit. It has some of the 1980s nuttiness; the laughs start at the DVD menu.

Tsui Hark has produced so many films that have been fan favorites–Peking Opera Blues, Once Upon a Time in China, and Swordsman III: The East Is Red–that you can’t expect anything worthy to be overlooked. And yet not enough people have seen the bouncy Shanghai Blues, with moments of musical rapture, and The Chinese Feast, with all his faults and virtues bundled into a celebration of cooking and eating. There’s also The Blade, a convulsive revenge saga that seems to me one of the best movies made anywhere in the 1990s. After it’s over, you’re not sure what hit you.

Drama, comedy, dramedy. Any reader of PHK knows my fondness for the gender-bending romance Peter Chan Ho-sun’s He’s a Woman, She’s a Man, a lovely integration of musical, coming-of-age story, and satire of sex roles. But my favorite Michael Hui film, Chicken and Duck Talk didn’t feature in the first edition because I couldn’t get my hands on a print to illustrate it. Tracing the rivalry between a scruffy duck restaurant and a Japanese knockoff of Colonel Sanders, it yields many hilarious sequences, perhaps most notably Hui’s efforts to conceal a plague of rats from health inspectors.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

Chow Yun-fat made his western reputation in crime movies, but his local fans also love his comedies and dramas. Try the screwball Diary of a Big Man (right) in which Chow juggles two wives and enacts a music video; the wistful romantic drama An Autumn Tale; and of course the male melodrama All About Ah Long. Churning out six to nine movies a year, the man was a real movie star. In April 1995, I was waiting in line to see Peace Hotel and felt the crowd’s nervous anticipation. Three whole months had passed since they’d seen their friend in a new movie.

My associates sigh when I mention Wong Jing. What can I say? I find some of his films funny. Try Boys Are Easy, Tricky Master, and, probably my favorite, Whatever You Want. If you don’t like them, write my suggestion off as David in his Dotage. Speaking of silliness, I’m not over-fond of Stephen Chow, but All for the Winner, Flirting Scholar, From Beijing with Love, and A Chinese Odyssey are ingratiating enough. Square that I am, I like Shaolin Soccer too.

I’d add the medical melodrama C’est la Vie, Mon Cherie, the unpredictable cop stakeout movie Bullets over Summer, and the poignant Juliet in Love, about a triad’s attraction to a woman recovering from a mastectomy. Sylvia Chang Ai-chia’s quiet romantic dramas Tempting Heart and 20 30 40 are also rewarding. Patrick Tam Kar-ming’s films are still unjustly neglected, so anything might be considered obscure, but I was delighted when a passable DVD of My Heart Is that Eternal Rose was released. Here Tam lyricized the gangster movie; Wong Kar-wai took the next step.

For grotesque comedy, try You Shoot I Shoot, about a contract killer who adds value by having an aspiring director film the hits (complete with slo-mo) for the delectation of the client. Unclassifiable is The Inspector Wears Skirts II, a cop-training story that pits women recruits against dimwitted men. It includes a dance sequence displaying minimal skill and maximal cheerfulness.

Fight club: Of Chang Cheh’s vast output of martial-arts movies, I have a special affection for New One-Armed Swordsman, a spectacularly mounted action picture, and Crippled Avengers, in which “disabled” really does mean “differently abled.” For Lau Kar-leung, I especially admire Legendary Weapons of China, one of the strangest of his forays into the arcana of martial arts lore and Chinese history; Shaolin Challenges Ninja (aka Heroes of the East), a sort of Taming of the Shrew, but with throwing stars; and the harrowing Eight-Diagram Pole Fighter, something of a valedictory for the Shaolin tradition at Shaw Brothers. Both these directors made so many worthwhile films that you can spend a lot of agreeable time exploring their output.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

Though not everyone agrees, I think that Corey Yuen Kwai is a fine director of action pictures, from the tonally discordant Ninja in the Dragon’s Den through the warrior-women saga Yes, Madam!, the vigilante-justice Righting Wrongs (incredible, literally, final airborne sequence), and Saviour of the Soul, a futuristic fantasy with one shot looking forward to Chungking Express (right). Yuen’s Fong Sai-yuk films and Bodyguard from Beijing contain classic sequences—fighting on the heads of a crowd, on top of a precarious pile of furniture, in a hypermodern kitchen. Co-signing the first Transporter film, he turned in something resembling the classic Hong Kong style.

In the crime vein consider Kirk Wong’s hard-driving and pitiless Rock ‘n’ Roll Cop and Danny Lee’s Law with Two Phases (not a typo). Ringo Lam’s films are notably tougher and more tactile than those of his contemporaries; see his deromanticized classic City on Fire, the effort to out-Woo Woo that is Full Contact, and the lesser-known Full Alert. Eddie Fong Ling-Ching isn’t known for policiers, but Private Eye Blues was one of the films I enjoyed in the 1995 Panorama. His historical drama Kawashima Yoshiko is even more remarkable.

Connoisseurs know The Outlaw Brothers; one glimpse of the climax, in which a gunfight is interrupted by a hailstorm of poultry, usually convinces any viewer to take a closer look. I must add the below-the-radar ensembler Task Force, by John Woo protégé Patrick Leung Pak-kin. Gratifyingly untidy in skipping among the personal lives of a cop squad, it eventually focuses on the need to settle conflicts without violence—after, of course, supplying some snappy fight scenes of its own.

Post-handover take-outs. Most of the films I’ve mentioned are from the 1970s through the 1990s. But many worthy films have emerged in the 2000s. If they don’t always carry the effervescence of the earlier ones, many are solidly crafted. Some are discussed in Planet Hong Kong 2.0 and many more have received commentary on other websites (e.g., LoveHKFilm), so I’ll just mention a few that seem to me of more than transitory appeal.

Patrick Tam’s After This Our Exile is an unsentimental look at how an aggressive, heedless father must come to terms with his little boy. Needing You is a better-than-average office comedy, while Hooked on You is poignant in the gruff Hong Kong way, with a touching finale about the changes since 1997. Benny Chan Muk-sing’s action pictures usually deliver sturdy value in the old style. Try Connected, a remake of Cellular; New Police Story, with Jackie Chan as a cop coming to terms with age and failure in the face of nihilistic youth; and Invisible Target, which boasts an old-fashioned Hard Boiled demolition derby, with a police station ground zero this time. Horror fans already know how uneven HK films in that genre can be, but surely Fruit Chan Goh’s Dumplings is an admirably creepy achievement, and Soi Cheang Pou-soi did good work in the genre as well (Diamond Hill, Horror Hotline) before moving to the suspenseful Love Battlefield and the harsh action picture Dog Bite Dog.

Whew! After seven sword-like days, I’m running out of time, and I haven’t achieved a final victory. Want more dangerous encounters? Go to PHK or the Hong Kong Critics Society Award winnerss and start looking for your better tomorrow.

Sorry, I couldn’t resist.

Kristin and I discuss film festivals as an aspect of global film culture in Chapter 29 of Film History: An Introduction. For detailed research into the festival scene, see Richard Porton, ed., Dekalog 3: On Film Festivals and several publications from St. Andrews University. The most recent volume, edited by Dina Iordanova and Ruby Cheung, focuses on East Asian events.

P.S. Thanks to Yvonne Teh for a title correction, and Tim Youngs for a geographical one!

Photo: Joanna C. Lee, courtesy Ken Smith.