Archive for the 'Festivals: Hong Kong' Category

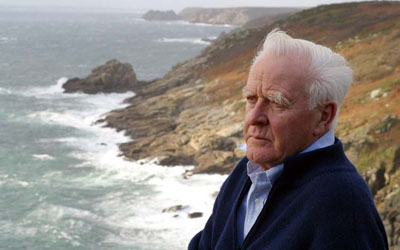

The spy who came in from the typhoon

Every year I buy a used paperback of John le Carré’s The Honourable Schoolboy (1977) and take it to Hong Kong with me, to be left for someone else when I pack up to leave. One year I left a copy, then returned the following year to the same hotel. The desk clerk remembered my name and ran to the back room, where last year’s copy had been carefully retained.

During my first trip in spring of 1995, I found The Honourable Schoolboy remaindered in a Silvercord bookshop that has long since vanished. Reading the novel while I encountered HK for the first time was an exhilarating experience because, of course, the story is set there. Le Carré aficionados know that it’s the second in the Quest for Karla trilogy launched by Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and completed by Smiley’s People. In this middle installment, we see how the mole who infiltrated the highest reaches of British intelligence wrecked the spy setup in the Crown Colony. A youngish agent, Jerry Westerby, is sent there to pursue the possibility that a member of Hong Kong’s business elite might be representing Soviet interests. Eventually, since this is Hong Kong, opium and the People’s Republic push their way into the picture.

The particular enjoyment I get from this novel during my visits owes a lot to its evocation of a city in the seventies that remains recognizable today.

Star Heights was the newest and tallest apartment block in the Midlevels, built on the round, and by night jammed like a huge lighted pencil into the soft darkness of the Peak. A winding causeway led to it, but the only pavement was a line of curbstone six inches wide between the causeway and the cliff. At Star Heights, pedestrians were in bad taste.

Yet the pleasures go far beyond acute observation of local detail. Everything that makes le Carré a splendid storyteller appears at full stretch in The Honourable Schoolboy.

The novel shows how intelligence missions, no matter how carefully planned, spin out of control because of human frailties, administrative rivalries, budget cuts, and political expediency. Sound familiar in the America of today? Like its mates in the Karla trilogy, the book begins on the periphery of the action, filling in secondary characters before building patiently towards a widely-ramifying plot. Le Carré manipulates point of view in a way that few novelists can manage, giving us a sense of circles of power made up of unnamed observers commenting on things they don’t understand. Here are the opening sentences of the first three paragraphs.

Afterward, in the dusty little corners where London’s secret servants drink together, there was argument about where the Dolphin case history should really begin. One crowd, led by a blimpish fellow in charge of microphone transcription, went so far as to claim that the fitting date was some sixty years ago. . . .

To less-flowery minds, the true genesis was Haydon’s unmasking by George Smiley and Smiley’s consequent appointment as caretaker chief of the betrayed service, which occurred in the late November of 1973.

One scholarly soul, a researcher of some sort—in the jargon, a “burrower”—even insisted, in his cups, upon January 26, 1841, as the natural date, when a certain Captain Elliott of the Royal Navy took a landing party to a fog-laden rock called Hong Kong at the mouth of the Pearl River and a few days later proclaimed it a British colony.

Our unidentified chronicler has the omniscience of an urbane insider. This is institutional memory as rumor, half-baked opinion, and shreds of fact, flavored with a touch of sarcasm. At the same time, this first page is a call to adventure. You can’t miss the rumble of kettledrums and thunder in the distance. This story will unfold in a spacious, even leisurely, manner, but will be no less suspenseful for that.

A page along we read:

The debate continues wherever old comrades meet, though the name of Jerry Westerby, understandably, is seldom mentioned. Occasionally, it is true, somebody does, out of foolhardiness or sentiment or plain forgetfulness, dredge it up, and there is atmosphere for a moment; but it passes. Only the other day. . . .

The worrisome chord is struck in a single word: understandably: At this point we understand no such thing, but five hundred pages later we will. Only then will this passage, reread, deliver its full charge of pathos.

Our chronicler’s tradecraft is impeccable. Most narratives consist of taking someone from one place to another and having him or her talk to somebody else. This poses several problems: (a) creating a vivid scene of character interchange; (b) using that interchange to summon up past events with clarity; and (c) pushing the story forward by having us understand what is gleaned from the conversation. Le Carré’s masterwork in this regard is probably Smiley’s People, which is almost Jamesian in suggesting that nearly all the important action is over, and what matters is how it has changed people’s lives. But The Honourable Schoolboy solves the problem no less deftly. Today’s spy novel would be unlikely to devote twenty pages to the questioning of the slightly gaga Reverend Hibbert, served tea by his scowling daughter. Yet it is a whole short story in itself.

Like other le Carré novels of the period, The Honourable Schoolboy displays an almost Dickensian relish in human variety. Every character is a little magnified, endowed not only with memorable tags, speeches, and bits of behavior but a pervasive attitude toward life that shifts our perspective on the main action. It’s as if the stolidity and self-containment of spymaster George Smiley calls forth extravagance in the portrayal of nearly all his staff. Connie Sachs, the bubbling, arthritic Soviet expert who carries her dog with her everywhere; de Salis, the Chinese specialist who tugs his hair and writhes as he reports; Fawn, Smiley’s devoted little bodyguard, who will grin while he breaks a man’s arms—the characters have something that most of today’s novelists, committed to the mundane, fail to give us: eccentric vitality.

The characters’ colliding attitudes emerge most starkly in a situation in which le Carré rules supreme. That is the administrative meeting. No writer I know is better at tracing the ripples of jealousy, showoffishness, toadying, and side-switching set loose when rather colorless men (it is always men) sit around a table and struggle for bureaucratic power. Le Carré is especially good on American arrogance.

One of the quiet men used the work name Murphy. Murphy was so fair he was nearly albino. Taking a folder from the rosewood table, Murphy began reading from it aloud with great respect in his voice. He held each page singly between his clean fingers.

Lest it be thought from these books, and from le Carré’s outrage against the Iraq war, that he is a reflexive anti-American, it should be said that he is no less severe with the Brits. One of his most scathing nonfiction pieces is his introduction to The Philby Conspiracy, where he denounces English snobbery and complacency for facilitating the real-life counterspying that formed the basis of his trilogy. Throughout his work, le Carré asks whether decency and kindness can survive the cynicism and compromises of a life built on deceit. Whether anyone, schoolboy or not, can retain honor in the Great Game is the central question of his Hong Kong novel.

Le Carré manages to show the bureaucrats’ tabletop swordplay as at once petty, springing from vanity and professional spite, and momentous. The world, or at least some big part of it, really is at stake. By the end of The Honourable Schoolboy, Westerby is at the end of his rope and he contemplates the betrayals and innocent deaths at which he has connived. Through his bitter disillusionment, we see an apocalypse.

As he gazed through the rear window of the car, it seemed to him that the very world that he was moving through had also been abandoned. The street markets were deserted, the pavements, even the doorways. Above them the Peak loomed fruitfully, its crocodile spine daubed by a ragged moon.

It’s the Colony’s last day, he decided: Peking has made its proverbial telephone call. “Get out, party over.” The last hotel was closing; he saw the empty Rolls-Royces lying like scrap around the harbour, and the last blue-rinse round-eye matron, laden with her tax-free furs and jewellery, tottering up the gangway of the last cruise ship; the last China-watcher frantically feeding his last miscalculations into the shredder; the looted shops, the empty city waiting like a carcass for the hordes. For a moment it was all one vanishing world; here, Phnom Penh, Saigon, London—a world on loan, with the creditors standing at the door and Jerry himself, in some unfathomable way, a part of the debt that was owed.

The end of empire has seldom been evoked so chillingly, and any day now the creditors whom Jerry imagines, moving toward hypermodernization, will be calling for payment.

The first and last novels in the trilogy became BBC adaptations, and they’re watchable, largely because of Alec Guinness as Smiley. They were shot in 16mm, largely on location, and the visual drabness fits the atmosphere of the books. (See the opening of Tinker, Tailor here.) It was evidently beyond the BBC’s budget to film The Honourable Schoolboy in Hong Kong, Cambodia, and Thailand, or plausible facsimiles thereof.

The first and last novels in the trilogy became BBC adaptations, and they’re watchable, largely because of Alec Guinness as Smiley. They were shot in 16mm, largely on location, and the visual drabness fits the atmosphere of the books. (See the opening of Tinker, Tailor here.) It was evidently beyond the BBC’s budget to film The Honourable Schoolboy in Hong Kong, Cambodia, and Thailand, or plausible facsimiles thereof.

There is a BBC radio version, but I still hope for a film adaptation some day. The story can stand independently of the trilogy, and with its multiple viewpoints, sympathetic protagonist, geopolitical themes, vivid settings, and side trips to Southeast Asian theatres of war, it could in respectful hands make for a strong feature.

In the meantime, we have the book. Granting my special fondness for its locale, I still think it one of the great novels—not great “genre” novels, but just great novels—of the century just past.

Dragons on your doorstep

DB here:

Once more, Hong Kong. Still a spellbinding place, although the municipality is doing whatever it can to force pedestrians underground and surrender the streets to cars. Even a dragon has to wait for the pedestrian light. And now, thanks to the sandstorms in China, the air is thick with pollution. I have taken defensive measures. My students probably wished I’d worn one of these more often.

Yes, that is the Boy Scout logo behind me. Why? Answer here.

I’ve already seen a few films at the Hong Kong International Film Festival, but I’ll try as usual to fold my viewings into a few thematically related entries. In the meantime, amateur reportage and celebrity gawking take over. I’m surface-skimming, I grant you, but it’s quite a surface.

For some years now, the festival has meshed with Filmart, the regional film market and trade show, and the Asian Film Awards. So you need badges.

For most of this week, the big events take place at the Hong Kong Convention Centre.

The opening reception for the festival offered all the glitter you can ask for, literally, when a cascade of sparkling paper showered down on the group photo of the organizers.

Among those present: Tang Wei, star of Lust, Caution and featured alongside Jacky Cheung in Ivy Ho’s festival-opener Crossing Hennessy.

Then there was Lisa Lu, radiant as ever. She was a wonderful star in Shaws’ golden age and continues to visit the festival annually, while sustaining her acting career.

Clara Law, director of one of the opening films, Like a Dream, embraces Lisa while Nansun Shi, herself a legendary and still central Hong Kong producer, looks on.

Filmart this year teemed with mainland Chinese media firms, but the classic Hong Kong companies also put in their appearance.

It’s reassuring to see that Wong Jing, the brains behind Naked Killer and Naked Weapon, hasn’t abandoned his old ways.

New regional enterprises are emerging. Patrick Frater and Steven Cremin, old Asian hands, have created FilmBusinessAsia as a resource of news, industry analysis, and in-depth information. Based in Hong Kong, they are ably teamed with Business Development Executive Gurjeet Chima, who speaks five languages.

Anyone interested in Asian film will find their information-packed website a must.

Two more entrepreneurs are Joey Leung and Linh La of Terracotta Distribution, a London-based outfit with an already impressive library. I met them through King Wei-chu, on the right, a programmer for Montreal’s FantAsia.

Three-dimensional film and TV were all over Filmart. Take a look at a 3D setup using the Red HD camera.

What a contraption! To shoot Potemkin, Napoleon, and a host of other 1920s films, you just needed a Debrie Parvo, that model of Style Moderne design.

Still, 3D television seems more or less ready for prime time. Can you tell the difference between reality and a 3D image?

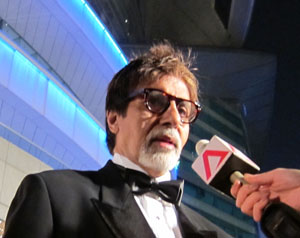

Also at the Convention Centre was the Asian Film Awards ceremony, which whizzed by in two hours. On the red carpet runway you could see some celebrities, such as Wai Ying-hung, a Shaw Brothers ingenue and kung-fu warrior from the 1980s who would win for best supporting actress in Ho Yuhang‘s At the End of Daybreak.

Among the slinky models and standard-issue teen idols on the red carpet, a note of dignity was struck by Amitabh Bachchan, who got a lifetime achievement award. He might as well officially change his name to Megastar Amitabh Bachchan.

For a complete rundown on the award winners, you can go here. We wrote about three of them in earlier blog entries: Bong Joon-ho‘s Mother (best picture, best actress, best screenplay), Ho Yuhang‘s At the End of Daybreak (best newcomer, best supporting actress) and Chris Chong‘s Karaoke (best editing). Among the nominees, we also wrote about Love Exposure, About Elly (I really wish it had won something), Cow, Air Doll, and Breathless. I was particularly struck by the cheers and whoops the audience gave Wang Xueqi of Bodyguards and Assassins, which I caught up with today. He’s an actor of gravity, who unlike most Hong Kong performers believes that less (hamming) is more (engrossing).

With the big launching events over, we can get down to the real business: Watching movies and discovering some sublimity in them. More entries, as usual, to come.

Hong Kong wrapup: Places and faces

DB here, just back:

The numbers are pretty staggering. The Hong Kong International Film Festival ran 22 days (the first four incorporating Filmart, the Asian market). In 510 screenings, 279 films from 50 countries were shown. There were 19 world premieres, 17 international premieres, and 33 Asian premieres. Attendance figures are yet to be determined, but so far things look to match the nearly 600,000 tickets sold last year. (*Correction 1 May 2009: The figure of 600,000 refers to an estimate of total attendance at all events, including free screenings, panels, seminars, etc. Total tickets are currently estimated at 100,000. Thanks to Li Cheuk-to for the correction.)

Having stayed for the whole event, I felt some festival fatigue. But the final days of the fest were full of fine movies. I left feeling that all my time was well-spent—not least in seeing old friends and visiting some of the outstanding spots in this adrenaline-fueled city.

Ken Smith and Joanna Lee are forces of nature in the cultural life of Asia. Working mostly in musical performance, they arrange for performers’ tours, consult with cultural agencies, translate, write, and do damn near everything else as well. Call them global impresarios. They helped coordinate the YouTube Symphony Orchestra, and they played central roles in the creation of the opera The Bonesetter’s Daughter, a collaboration between Amy Tan and Stewart Wallace. This resulted in a 2008 production by the San Francisco Opera. The September premiere was broadcast in Hong Kong last Easter Sunday, and will be available at the RTHK website for playback for the following 365 days. Give it a listen here.

Ken’s engrossing book, Fate! Luck! Chance!, documents the making of the opera and includes a libretto. You can read background on Ken’s book here.

Above, Ken and Joanna take in pudding at a historic hole-in-the-wall eatery. The pudding comes in two varieties, milk and eggyolk-based. Mighty sweet, and as if by chance (or fate, or luck), the stools mimic the main attractions.

Old friends Linda Lai Chiu-han and Hector Rodriguez teach in the digital media and arts program at the City University of Hong Kong.

Linda has just had a film accepted for Oberhausen. She’s on a roll: It’s her second screening in this, the major festival for short films.

The W Hotel, where the Festival was headquartered, was posh to the max. Every time I went in, I expected someone to figure out that I wasn’t well-dressed enough to be there. If you ever wondered what George Segal’s ghostly sculptures would read, you could check out these pale volumes fastened to the shelves along the elevators.

My own hotel was somewhat different. The B. P. in B. P. International House stands for Baden-Powell, and the place was teeming with Boy and Girl Scouts nearly every day. In the modern atrium hangs a reverent portrait of the man himself.

It was pleasant to stay beside Kowloon Park. Headed for the Cultural Centre or the ferry, I could avoid the crowds on Nathan Road by ambling through the park.

While I was in town, developers put the finishing touches on a neo-retro-colonialist complex at the south end of Canton Road.

You must admit that Hong Kong sorely needs another shopping mall.

Back to the faces: Gary Bettinson (University of Lancaster), Emilie Yeh (Hong Kong Baptist University), and Darrell William Davis (Lingnan University).

Gary writes on contemporary Hong Kong cinema, particularly Wong Kar-wai; most recently, he has an essay on 2046 in Warren Buckland’s anthology on puzzle films. Emilie researches Chinese film, as does her husband Darrell, who started his career working on Japan. I’ve already mentioned their book on Asian media industries in an earlier blog, but also have a look at their fine Taiwanese Film Directors: A Treasure Island. I gave a talk for Emilie and Darrell at HK Baptist, and we had a good discussion among their students and colleagues.

More intellect: This year the festival paid tribute to Ingmar Bergman. A friend of his, Marie Nyreröd, brought her enlightening documentary, Bergman’s Island. Here she’s seen with another Bergman expert, my amigo Paisley Livingston, philosopher and film critic-theorist teaching at Lingnan University.

For over forty years, Erika and Ulrich Gregor have been colossal figures in world film culture–as critics, archivists, and festival programmers. They served on two juries during their stay here.

Scan earlier years of my Hong Kong visits and you’ll find these three regulars: King Wei-Chu (FantAsia programmer), Peter Rist (Film prof at Concordia of Montreal), and Yvonne Teh, Hong Kong journalist. After a screening at the Science Museum, it’s wonderful to sit out in a cafe.

Here are Johnnie To and his right-hand man Shan Ding at To’s magnificent office in Milkyway Headquarters.

The Milkyway team is busy. To’s Vengeance, starring Johnny Hallyday, will open in Paris on 20 May. Mr. To and Shan continue to work with their collaborators on a remake of Melville’s The Red Circle, and they’re preparing a New Year’s comedy as well. Here’s Cheang Soi, one of the most ambitious of the younger HK directors (Love Battlefield, Dog Bite Dog). Soi is finishing Accident, which looks to premiere at the end of the summer.

John Shum (aka Sham) is a legendary figure–a comedian since the 1980s, a producer, and an energetic advocate for local democracy.

Wong Ain-ling has been a critic and festival administrator. Currently she works as Senior Researcher at the Hong Kong Film Archive. She played a crucial role in the restoration of Fei Mu’s Confucius.

Derek Kwok (director of The Pye-Dog) is again collaborating with legendary actor-singer Teddy Robin Kwan.

In all, another wonderful year of food (and food for thought), talk, and above all movies. You won’t find a festival anywhere more dedicated to the power of film in all its variety. So once more my tagline: See you here next year?

At the Film Workshop party: Lau Siuming, John Woo, Johnnie To, Tsui Hark, and Benny Chan. Thanks to Alvin Tse for the photo.

Passion, mortality, and everyday life

DB, flying back from Hong Kong:

Some of the most important films playing at the Hong Kong International Film Festival were already familiar to me—Still Walking, Il Divo, Gomorrah, Ashes of Time Redux—and some of my discoveries in Hong Kong have been covered in more recent entries.

What remains? Accentuating the positive, I’ll not talk about the disappointing items, some with strong reputations. I hope to blog about others in the months to come, when I’ve had a chance to study DVDs.

In the meantime, Kristin has already touched on Beaches of Agnès, a real charmer. Varda can be whimsical without turning fey; even dressed as a potato she doesn’t seem to be trying to grab attention. The film is a digressive, passionate memoir. The background on her early life is captivating, and her career as a photographer, shooting snaps of Pierre Vilar and Gerard Philippe, furnishes a stab of pathos. A montage of beautiful boys and girls: gone. Soon we get Varda’s straightforward acknowledgment of Demy’s death from AIDS. “All the dead lead me back to Jacques.”

Götz Spielmann’s Revanche, which I’d passed up at other fests, was a very solid psychological thriller. It’s built around two contrasting worlds, the sex trade of Vienna and the placid, churchgoing lifestyle of a village. From the first comes Alex, a man-of-all-work in a brothel. He falls in love with a Ukrainian hooker, and between bouts of cocaine he vows to help her escape the business. In the village live the policeman Robert and his wife Susanne, trying to have a child. Their life is secure and cozy, though Robert is wound a bit tight. The two worlds intersect during a bank robbery, and the rest of the drama plays out in the countryside, with Alex taking refuge on his grandfather’s farm. Alex and Robert become two variants of masculine anxiety, each defined by his way with a pistol, and their decisive confrontation is deftly postponed until the very last moments of the film.

I admire the way that Spielmann uses a spare long-take technique to increase suspense. Each scene usually consists of a single shot, taken from a judiciously chosen angle that unfolds the drama smoothly. There are barely 200 shots in nearly two hours, but the scenes don’t seem stiff because the framing and staging are quietly varied. Shot/ reverse-shot cutting is reserved for two turning points, one in the middle and one at the end. It’s nice to see a movie with no filler material, no passages of people driving in cars or going into the buildings, none of those time-wasting aerial shots of cities.

Some nice sound work too! No Country for Old Men has been rightly praised for its use of offscreen noise, but the Coens look rather showoffish compared to what Spielmann has accomplished here. A shot of Robert and Susanne on their patio is accompanied by the faintest rustle on the right channel: Alex, spying on domestic happiness like a character out of Highsmith or Ruth Rendell, has slipped away.

Similarly elegant in its staging and sound work is Claire Denis’ 35 Shots of Rum. The teasing exposition—a man watches commuter trains, a young woman rides one—dares us to imagine scenarios that could involve both. Our speculations turn out to be too wild, since their relationship is the most uncomplicated to be imagined. Based frankly on Ozu’s Late Spring, 35 Shots builds up its drama through daily routines, following its principals and their neighbors in everyday situations until, quite unexpectedly, a quiet crisis blossoms. Soon one scene ends: “We could be like this forever.” Next scene: everything has been overturned, and characters must change their lives. Visually the film is a marvel, with glowing scenes of semidarkness and discreetly out-of-focus details. As in her masterful Beau Travail, Denis supplies a powerful last shot, this time of an object we’ve nearly forgotten.

Two more thoughts: In my discussion of Revanche and 35 Shots, I’ve had to be coy in explaining basic plot situations and character relationships. That’s because these films work elliptically, holding back the sort of expository information that would be given in a concentrated dose early in most classical narratives. This narrational strategy poses no problem for an academic analysis, which tends to assume that the reader has seen the film. But it’s more difficult to handle when you’re writing a review. You don’t want to spoil the viewer’s surprise by explaining a core situation that the filmmaker has chosen to unfold gradually. If reviewers of Hollywood movies can’t give away the ending, the reviewer of an art film probably shouldn’t give away the beginning, or at least the information that it keeps in suspension for some time.

In other respects, though, there isn’t a clear dividing line between the “psychological” drama of international festival cinema and the more “externally driven” action of mainstream entertainment. Popular cinema relies on physical props like clues, souvenirs, messages, and gifts to help drive the plot. So, less obviously, do art films. The two photographs in Revanche deepen the character drama while triggering a major realization. The accidentally discovered letter (a convention of melodrama akin to the overheard conversation) in 35 Shots not only explains past actions but primes us to expect some conflict to come. As Aristotle knew, stories seem to need tokens to drive character revelation and plot reversals. A narrative universal?

Japanorama

Naked of Defenses.

Many of the movies I most enjoyed were Japanese. No surprise there. I know I’m prejudiced in favor, but objectively speaking the Japanese industry has long combined high output with great diversity and depth. I’m inclined to think that across film history, the three most consistently excellent filmmaking nations have been America, France, and Japan.

During Filmart, Yoshizaki Masahiro gave a swift but informative report on the current state of Japan’s “content industry.” It is the currently the world’s second-largest national film market , but it will sooner or later be replaced by China. Currently Japanese films are reclaiming the local audience, sometimes grabbing over half the annual box office. Unfortunately, that audience isn’t growing, and with a plunging birthrate, it’s unlikely to do so. Moreover, Japanese cinema has always been difficult to export, even in Asia. The great exception, of course, is anime, but even that is starting to slump. Anime is largely a television/ video format, yielding about twice in those platforms what it yields in theatrical income. But as advertising dollars have withered in the recession, anime has been cut back.

Despite all this, Japanese companies manage to release a staggering 400 or so films per year. (What counts as a release—theatrical? direct to video?—we leave for another day.) And the variety remains remarkable, judging by what I saw during my stay in Hong Kong. Put another way: Japan makes movies that are sweet, touching, funny, silly, and peculiar to the point of perversity. Not necessarily perversion, but that’s there too. And yes, schoolgirls’ panties are involved.

Not part of the festival, but playing in town was the diverting comedy Happy Flight. Like Airport and Airplane!, it weaves together various characters involved with a single flight. It concentrates almost completely on the professionals, from gate agents and mechanics to pilots and air hostesses. The one passenger depicted in detail rings true: After being allowed to bring an oversized bag into the cabin, he becomes a browbeating jerk.

Not part of the festival, but playing in town was the diverting comedy Happy Flight. Like Airport and Airplane!, it weaves together various characters involved with a single flight. It concentrates almost completely on the professionals, from gate agents and mechanics to pilots and air hostesses. The one passenger depicted in detail rings true: After being allowed to bring an oversized bag into the cabin, he becomes a browbeating jerk.

The film maintains its infectious pacing, adorning the action with minor-key gags like the airport’s “Somkin Room” for smokers. I also liked the moments of teamwork. When the stewardesses need a cake, they concoct one out of various packaged snacks. A young mechanic, constantly berated by his boss, thinks he’s dropped a wrench into the plane’s engine, and the whole ground crew searches the hangar for it. As with Airplane!, the final credits resolve several plotlines and add a few gags. If you like Waterboys and Swing Girls, also directed by Yaguchi Shinobu, you’d probably enjoy this.

Just as light, but a lot more intricate is Nakamura Yoshihiro’s Fish Story. Another network narrative, this one traces how Japan’s purported first punk song changed the course of history. The plot skips among periods from 1953 to 2012, when a comet is about to incinerate the earth. With many pop-culture in-jokes, from Beatles albums to The Karate Kid, this breezy, off-kilter item gets by on sheer adrenaline and on a cascade of puzzles. Why does the Fish Story song make no sense? Why does it contain a one-minute passage of silence? How are all these stories connected? And how can a song save the world? The narration cleverly withholds the basic relationships among the characters until a dizzying montage at the end wraps everything up.

Still further out there on the Nutsometer is Love Exposure, your basic four-hour inquiry into Christianity, cross-dressing, superheroics, and schoolgirl underwear. The story starts with a boy who promises his mother he’ll marry a woman like the Virgin Mary, but thanks to digital photography and an acrobatic approach to filming schoolgirls’ nether regions, he becomes known to his peers as King of the Perverts. Director Sion Sono satirizes cult religions, which seems to include Catholicism (“Your sin is that you can’t remember your own sin”), while devoting some attention to pornographic movies and “Candle in the Wind.” Rambling and digressive, but rapidly paced, Love Exposure proves that nobody beats the Japanese for cheerful dirty fun.

Still further out there on the Nutsometer is Love Exposure, your basic four-hour inquiry into Christianity, cross-dressing, superheroics, and schoolgirl underwear. The story starts with a boy who promises his mother he’ll marry a woman like the Virgin Mary, but thanks to digital photography and an acrobatic approach to filming schoolgirls’ nether regions, he becomes known to his peers as King of the Perverts. Director Sion Sono satirizes cult religions, which seems to include Catholicism (“Your sin is that you can’t remember your own sin”), while devoting some attention to pornographic movies and “Candle in the Wind.” Rambling and digressive, but rapidly paced, Love Exposure proves that nobody beats the Japanese for cheerful dirty fun.

A more straightforward Japanese entry in the Asian Digital competition was Ichii Masahide’s Naked of Defenses (the most awkwardly titled film I saw). Two women work at a factory making plastic parts. Ritsuko, a plain but dogged supervisor, is becoming alienated from her husband after her miscarriage. She envies the pregnant and insouciant new hire Chinatsu, whose marriage is overcoming its problems. Plain and sincere in its technique, Naked of Defenses ends with an astonishing sequence. By all the evidence onscreen, Ichii got a pregnant woman to play Chikatsu and filmed her giving birth. Balancing this powerful ending is the striking performance of Moriya Ayako as a woman sinking into depression but who may be saved by friendship and maternal love.

I took the occasion to catch Departures at a local theatre, since I had missed it at earlier festivals. And I’m happy to report that it’s distributed in the US by Regent Entertainment, run by Wisconsin graduate and old friend Steven Jarchow.

By now you’ve probably seen Departures too. At one level, it’s a good old-fashioned Shochiku movie, mixing tears and good-natured humor. Some decry it as middlebrow sentiment, but I found it a touching, fluent tale. For me, the central attraction is the repertory of gestures. Our two professionals handle the recently deceased tenderly, but that doesn’t preclude a crisp efficiency in flaring out a sleeve. I don’t think I’ll forget the way the undertaker grasps the dead person’s clasped hands and then executes a circular snap. Precise manipulation becomes a sign of respect.

And it isn’t all sunniness. Handling dead bodies is hazardous cultural territory in Japan. It is traditionally a task for the burakumin, a minority group long looked down upon. Although discrimination against the group has apparently diminished, the fact that a big star like Motoki Masahiro could play the role of a corpse-preparer could help dispel a lingering social stigma.

You could almost mount a Japanese film festival about mortality. Some musts would be Ozu’s Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family and Tokyo Story, Kurosawa’s To Live, and Kore-eda’s After Life. Another required item would be Dying at a Hospital (1993), a rarely seen Ichikawa Jun film screened as part of a tribute to the recently deceased director. It consists of staged episodes showing a few cancer patients in their last months. An elderly husband and wife both have cancer, but must separate and be treated in different hospitals. A widow laments her rotten luck. A lively young man can’t accept the fact that he won’t see his children grow up. A homeless man is brought in, filthy and disoriented, and as he becomes aware of his plight, he still apologizes for accidentally turning up his pocket radio.

These and other cases are accompanied by voice-over narration from the doctor and nurse who treat them. Interspersed with these scenes are rapid documentary montages of people enjoying life—eating, drinking, viewing cherry blossoms, celebrating festivals, just walking down the street. The intimate facial reactions we’re denied in the hospital scenes are supplied in these vérité passages.

Dying at a Hospital is gentle and sympathetic, but its manner of shooting gives it special resonance. The hospital scenes are shot in planimetric fashion, with the camera rigidly facing a row of three beds, or a pair of beds, or only a single one. Everything is played in long shot, with no close-ups or camera movements to enlarge the faces.

Patients, visitors, and hospital staff move through these blocks of space. The lighting effects are particularly subtle, accentuated by very gradual fade-ins and fade-outs, as if dawn were breaking or night were coming on. As the film goes on, Ichikawa introduces variations in scale and new cutting patterns, creating what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film a sparse version of parametric narration. For instance, the spaces become more compact as terminal patients are shifted from a shared room to a private one, which permits nuanced effects of distant depth.

Ichikawa’s dry, physically detached treatment lets the poignancy of each situation emerge without any directorial boosting. The glimpses of daily life outside the hospital, zestful and shot on the fly, generate a powerful contrast: the preciousness of ordinary pleasures, and the dignity that must be accorded everyone about to leave them behind.

For a brief but sensitive appreciation of 35 Shots, see Ryland Walker Knight’s comments here–perhaps best read, for reasons mentioned above, after you’ve seen the film.

Departures.