Archive for the 'Festivals: Hong Kong' Category

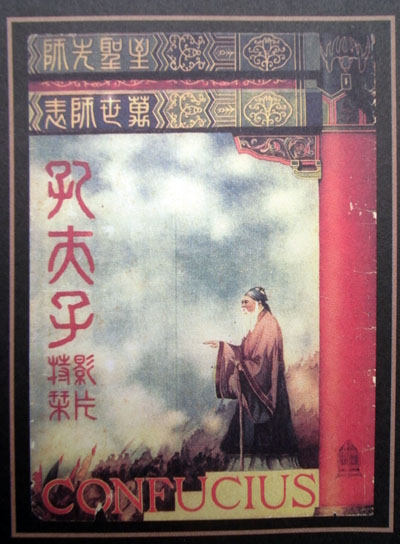

Confucius reborn

DB, in Hong Kong:

Fei Mu is a little-known name in the West, but on the evidence of even a few films, it’s clear that this mainland Chinese filmmaker was one of the finest working anywhere during the 1930s and 1940s. His best-known film, Spring in a Small Town (1948), was considered in the Maoist era an overliterary piece of sympathy for the bourgeoisie. Now things have changed. Many specialists today consider Spring in a Small Town the best Chinese film of all time. It’s an extraordinary work, anticipating Antonioni in its slow unfolding of an erotic situation, treated with a mixture of sympathy and austerity. It’s a great pity that the film isn’t available on good and subtitled DVD copies, though a digitally restored print was made in 2005.

Fei Mu is a little-known name in the West, but on the evidence of even a few films, it’s clear that this mainland Chinese filmmaker was one of the finest working anywhere during the 1930s and 1940s. His best-known film, Spring in a Small Town (1948), was considered in the Maoist era an overliterary piece of sympathy for the bourgeoisie. Now things have changed. Many specialists today consider Spring in a Small Town the best Chinese film of all time. It’s an extraordinary work, anticipating Antonioni in its slow unfolding of an erotic situation, treated with a mixture of sympathy and austerity. It’s a great pity that the film isn’t available on good and subtitled DVD copies, though a digitally restored print was made in 2005.

Two other Fei Mu films I’ve seen show the variety and flexibility of his craft. Onstage, Backstage (1936) is a drama of theatre life, and its fluid figure movement in depth recalls Renoir. Very different is the expressionistic allegory Nightmares in Spring Chamber (1937), an episode in the portmanteau film called Lianhua Symphony. Fei presents the Japanese invasion of China as the pursuit of an innocent girl through dark sets by a leering, frock-coated Japanese. Other surviving Fei works, such as Blood on Wolf Mountain (1936), are also held in high regard. After Mao’s revolution, Fei Mu moved to Hong Kong, where he died at the age of 45. He directed no films in the Crown Colony.

All this makes the discovery of a print of Confucius (1940) an event of capital importance. An anonymous individual donated a print to the Hong Kong Film Archive, which spent years restoring it in collaboration with L’Immagine Ritrovata of Bologna. In the donated print of Confucius, some portions of the soundtrack had liquefied, so some stretches are silent, and there are about nine minutes of fragments that have yet to be integrated.

At the premiere, a very useful booklet on the film’s restoration was given out, and moving introductory speeches were presented by Barbara Fei Ming-yee, the director’s daughter, and Serena Jin, daughter of the producer Jin Xinmin. The screening added electronic subtitles that not only translated the dialogue but identified each speaker—a helpful gesture for a film with many characters and a tangled intrigue.

I can’t comment on it as a representation of Confucius’ thought and life, although experts tell us that it is quite different from the elevated, almost sanctified portrayals that were known before. The plot dramatizes the ineffectuality of the sage’s ideals of civic virtue by showing how power players of his era ignored or undercut his teachings. Scenes from Confucius’ life alternate with scenes of political and military strategy, as warlords and statesmen debate tactics and, not incidentally, calculate how to eliminate Confucius. As Confucius migrates across China, he is unable to halt the continuous warfare among various factions. His disciples leave or die. Just before his death he has only his grandson to care for him. “A great educator, thinker, and philosopher,” Fei Mu writes in an essay, “Confucius was doomed a victim of the politics of his time.”

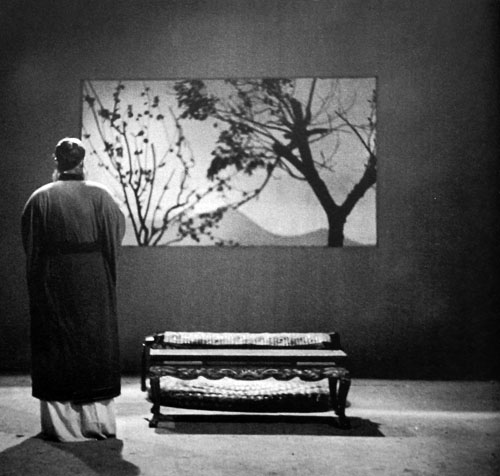

The film is slow-moving and hieratic. Some of the fragments show bits of violence, but the film as a whole relies on dialogue. Although some scenes unfold in natural exteriors, Fei Mu often employs theatrical tableaus, complete with painted landscapes; occasionally the actors cast shadows on the backdrops. The cutting is often axial, simply enlarging a chunk of space as actors declaim their dialogue. The nearly square Movietone frame enhances the symmetry of the compositions, which often feature a window or some other aperture.

Knowing the fluid style of Fei’s 1930s films, we can only regard this rigid, rather ceremonial look as a deliberate artistic choice. In this respect, the film recalls Eisenstein’s Alexander Nevsky and Mizoguchi’s Genroku Chushingura, films of that era aiming to treat a weighty historical subject with solemnity. In Confucius, Fei seems to have been rethinking the relation of cinema to theatre, a quest that preoccupied other directors of the period and that remains important today. Wong Ain-ling’s essay in the booklet aptly notes Rohmer’s Perceval le Gallois as a more recent parallel, and the film likewise has some of the feel of the Straub/ Huillet version of Von heute auf morgen (1997). As often happens, Fei Mu feels like a modern filmmaker.

Confucius was shown across China in 1940 and 1941, and a reedited version was released in 1948. Fei Mu was so upset by the new cut that he took out a newspaper ad denouncing it. Wong Ain-ling, who prepared the documentation for the festival presentation, and Sam Ho, the Archive Programmer, have concluded that this print is likely to have been the re-release version. Sam told me that the archive staff would be spending the next year researching how to integrate the fragments and supply a sense of the original’s design. The Archive is planning to screen that restoration at next year’s festival. Whatever the experts come up with, surely this is a discovery that will be discussed and enjoyed for many years.

Happy birthday, Film Workshop

Tsui Hark is the mad genius of Hong Kong cinema. The problem comes with assigning proportions. 10 % mad, 90% genius? 50-50? 99 % mad, 1 % genius?

Across a career that’s lasted more than thirty years, Tsui has had more ups and downs than the local economy. On the twenty-fifth anniversary of Film Workshop, the company he founded, the Hong Kong International Film Festival mounted a tribute. That provides an occasion to examine what he did and didn’t accomplish.

25 years old, but who’s counting?

Nansun Shi and Tsui Hark.

At this year’s Asian Film Awards, Film Workshop was given a special prize for outstanding achievement. On another evening there was a party gathering many Workshop alumi, from which the above photo comes. You can see more pictures from that party here. At the agnes b. gallery, a small show featured posters, a looped video documentary, a photocopy of the Better Tomorrow script, and some memorable props.

Nat Olsen has other pictures at his lively Hong Kong Hustle site.

The catalogue, A Tribute to Romantic Visions: 25th Anniversary of Film Workshop, is a must for all aficionados of Hong Kong film. Consisting largely of interviews, it offers many glimpses of creative choices and business strategies governing the company. Nansun Shi, Tsui’s partner and business manager, recalls how they placed films in overseas markets and won critical acclaim in Europe. She also explains matter-of-factly how frantic the midnight-show system was. In those days, Hong Kong filmmakers test-screened a movie to a midnight audience, and then reedited the film based on perceived reaction. Shi explains:

The catalogue, A Tribute to Romantic Visions: 25th Anniversary of Film Workshop, is a must for all aficionados of Hong Kong film. Consisting largely of interviews, it offers many glimpses of creative choices and business strategies governing the company. Nansun Shi, Tsui’s partner and business manager, recalls how they placed films in overseas markets and won critical acclaim in Europe. She also explains matter-of-factly how frantic the midnight-show system was. In those days, Hong Kong filmmakers test-screened a movie to a midnight audience, and then reedited the film based on perceived reaction. Shi explains:

Cinemas often wondered what could be done to a film in the eight hours between the midnight show and the day-time show the next day. I ran some calculation with the technicians: what is the least amount of time for them to do this and that, and then sent them to the cinemas to do the work. If worse comes to worst, they could do the re-editing when the show was running (80).

There isn’t much sugar-coating in the interviews. Collaborators often found Tsui a harsh taskmaster. At peak pressure, he seldom halted shooting for sleep and instead took cat naps on the set. Those who couldn’t keep up his pace, or adjust to his demands, left the company. There are also some comments on production practices. Herman Yau, for instance, notes: “Directors, in general, use most of the shots to tell the story. Tsui prefers images that look good on their own” (121).

Overall, the catalogue confirms that what started as a “workshop” designed to enable directors to realize individual creative visions became a company built around Tsui’s restless ideas about cinema. This was more or less the premise of the panel on Friday afternoon. Two critics, Keeto Lam and Longtin, discussed the Film Workshop enterprise largely as an extension of Tsui’s interests. Keeto had been a screenwriter at the company and shared information about the making of A Chinese Ghost Story 2, while Longtin speculated on Tsui’s interest in transcending polarities, particularly those between human and demon and male and female. Another scriptwriter was in the audience and contributed information as well.

One of Keeto’s points set me thinking. Having characterized Leslie Cheung as the “Golden Boy” of Film Workshop, he asked who the Golden Girl was, and he and audience members discussed candidates for the honor. (My vote, obviously, would go to Brigitte Lin.) But I began to speculate that one of Film Workshop’s main contributions was in star-making. Tsui has mentioned that his early films with gorgeous women tried to create a “comedy of pretty faces” opposed to the “comedy of ugly faces” that ruled in the 1970s and early 1980s. (Think of Michael and Ricky Hui, Karl Maka, Jackie Chan, and Sammo Hung.) By coaxing Brigitte Lin to Hong Kong and by giving Sally Yeh, Leslie Cheung, Chow Yun-fat, and other younger players big roles, Film Workshop created a new generation of glamorous stars.

A better yesterday

This celebration comes at a parlous period in Tsui’s career. Over the last dozen years Tsui directed some weak, even awful movies. Granted, even a bad Tsui movie is bad in a unique way, but that doesn’t make Tri-Star (1996), the Van Damme outings (Double Team, 1997; Knock Off, 1998), and The Legend of Zu (2001) any better. Some films he has produced, like Era of Vampires (2002) and Xanda (2003), are best forgotten. Today, after the only moderate success of Seven Swords (2008) and the disappointments Missing (2008) and All About Women (2008), many local film professionals consider him a spent force.

I’d argue that Tsui and Jackie Chan were the two most ambitious young filmmakers of 1980s Hong Kong. Tsui was the more daring and mercurial; he seemed to be trying a dozen things at once. He made some bad films, but others changed the face of local film: Shanghai Blues (1984), Peking Opera Blues (1986), A Better Tomorrow III (1989), Once Upon a Time in China I and II (1991, 1992), The East Is Red (1993), and The Chinese Feast and The Blade (both 1995). He also produced, and often co-directed, A Chinese Ghost Story and A Better Tomorrow (both 1986), The Big Heat and Gun Men (1988), The Killer (1989), the demented Wicked City (1992), and Iron Monkey (1993). These films had enormous impact locally, and they made Hong Kong film a major force in world cinema.

The problem is the mad-genius thing. Tsui is uneven, not only from film to film but within each one. Tsui can create a fairly unified tone, as The Blade and Seven Swords show. But more likely a Tsui film will contain something brilliant, something banal, something silly, and something just weird. Labored facetiousness is a virus plaguing Hong Kong film generally, but Tsui seems entirely too fond of bursts of dumb comedy. He replies: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.”

Yet the thrown-together quality of many of his movies also means that even a troublesome one is likely to have a passable sequence. More important, his best films use the lurches in tone to create a grotesque, sweeping verve. Things happen so fast you can’t protest; either go with it or walk out.

Tsui’s strategy is based upon a breathless rhythm. He chops off scenes without warning, and he bustles his actors around the set maniacally; the poor things seldom rest long. Almost never do characters simply sit down and talk to one another, as in those bland American indie films. The beginning of Triangle (2007) shows how nervous, even opaque, Tsui’s style becomes when characters have to sit still.

For Tsui, story action is a matter of physical movement, and the film frame becomes a force-field, with actors popping in and out with abandon. He carries the staccato choreography of martial-arts film down to the most straightforward dramatic scene. He’s not alone in this; you can find it in the 1980s martial-arts films too, but Tsui gives it a special force with his pitched angles, his wide-angle lenses, and his love of comic-book-rococo compositions. Try, for instance, this shot of a woman getting an injection in Missing.

Such images can seem merely cheap flash, but what saves the best ones from preciosity is their constant but disciplined rhythm. In Once Upon a Time in China, Wong Fei-hung is about to be arrested after a clash with local thugs. The shot starts with the police official pointing his pistol to Wong’s head.

Another cop comes in to tell the official that the invaders left something. Any other director would have shown the cop’s face, but why? He’s important only to get the official out of the frame, so he becomes just a red hat poking in from the lower right corner.

The official dodges out, moving rightward across the frame.

There’s a pause, then Wong, now isolated in the shot, snaps his head around to follow what’s happening.

Tsui isn’t usually considered an economical director, but it’s hard to imagine a more crisp way to handle this routine bit of action. The shot takes less than eight seconds.

The same restless energy rules Tsui’s cutting, which has a punch and recoil derived, I think, partly from New Hollywood (Spielberg especially; see the Jaws example here) and partly from the local martial arts tradition. (Some proto-Tsui cutting is on display in Lau Kar-leung’s Legendary Weapons of China, 1982.) Watching Once Upon a Time in China at the retrospective, I was reminded that Tsui not only cooks up sequences that you can’t forget (three words: fight on ladders), but he risks audacious cuts on movement that few contemporary directors could bring off. When he wants to emphasize a moment, he channels Eisenstein. During the final combat of Wong and Iron Robe Yim, the iron weight sliding down the platform gets the Potemkin treatment. Four shots stretch out the instant through overlapping movement.

As we might expect, Tsui goes beyond Eisenstein by accentuating major points of impact with swift camera movements forward.

Tsui thinks visually. True, some sound is important—he is a master at merging music and image—but words are a last resort. He has been known to change dialogue in post-production so radically that the dubbing doesn’t match the actors’ lip movements. Shooting without sound gives Tsui, like other Hong Kong directors, a freedom of camera placement that recalls the silent cinema. And like a silent director, he thinks that every story point needs to be pictured. Kenny Bee is looking for the girl he met years ago (Shanghai Blues)? So let’s have an image that dramatizes the problem.

The inclusion of Kenny’s graduation picture might seem superfluous, but it makes the frame an anticipatory wedding picture, and it gives us a sense of his pure, if naïve, romantic impulses.

Motion plus or minus emotion

Shanghai Blues.

If you disapprove of what Spielberg and Lucas did to the American cinema, you will hate Tsui’s love of remakes, sequels, and spinoffs, his frequent confusion of SPFX with imagination, and his efforts to milk franchises to a point that can be considered cynical. Yet historically, he pushed Hong Kong cinema forward.

Before the star-making efforts I’ve already mentioned, indeed before Film Workshop was created, Tsui’s Dangerous Encounters: First Kind (1980) offered a blistering attack on class disparity in Hong Kong. He updated Cantonese fantasy swordplay in Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983), and he tried his hand at a local version of low-budget exploitation in We’re Going to Eat You (1980). Keeto’s catalogue essay argues that Film Workshop pioneered six new genres in Hong Kong film, from comic-book adaptations to science-fiction and animation. And there’s more variety than we might expect. Film Workshop directors might have sometimes mimicked his style, but John Woo’s Workshop projects managed to do something quite different. Despite Tsui’s hands-on involvement, the lyrical Iron Monkey and the more hard-edged Gun Men and The Big Heat avoid the eccentricities of his signed work while maintaining his love of flamboyant set-pieces and visual creativity.

Tsui’s scripts often seem like patchwork, granted, but I tried to show in Planet Hong Kong that the episodic, additive plotline is a convention of Hong Kong cinema. Tsui—like Wong Kar-wai, though in a different key—took advantage of this formula to explore the power of the arresting image and an infectious rhythm. (You might say that Wong’s rhythm is that of cool jazz, while Tsui’s is closer to the percussiveness of Chinese opera.) Shanghai Blues and Peking Opera Blues, two of Tsui’s most ingratiating movies, jump smartly from one thrusting scene to the next, shifting emotional registers with dazzling speed. These movies can turn on a dime.

Tsui’s scripts often seem like patchwork, granted, but I tried to show in Planet Hong Kong that the episodic, additive plotline is a convention of Hong Kong cinema. Tsui—like Wong Kar-wai, though in a different key—took advantage of this formula to explore the power of the arresting image and an infectious rhythm. (You might say that Wong’s rhythm is that of cool jazz, while Tsui’s is closer to the percussiveness of Chinese opera.) Shanghai Blues and Peking Opera Blues, two of Tsui’s most ingratiating movies, jump smartly from one thrusting scene to the next, shifting emotional registers with dazzling speed. These movies can turn on a dime.

Part of what pulls us along is characters we care about—especially strong women. In the old days, we Hong Kong fans used to love the idea that John Woo, carrying on the Chang Cheh tradition, specialized in the sorrows of masculine obligation, while Tsui was much more interested in women. He gave us the comedy of pretty faces, the wide-eyed innocence of Joey Wong, and the severe beauty of Brigitte Lin who, in the final installment of the Swordsman series, becomes a sheer force of nature. (Her bi-gendered role in Ashes of Time stems from Tsui’s creation of her as such in Swordsman II and The East Is Red.) When Tsui took over the Better Tomorrow franchise, his prequel showed that Woo’s ideal hero Mark (Chow Yun-fat) learned his combat crafts from, of all people, a woman. Even the non-stop testosterone fervor of The Blade, all sweaty torsos and clanking weaponry, may be the hallucination of a madwoman.

These were rousing yarns. Yet at some point, I think, Tsui lost interest in telling a story. This tendency can be detected already in the Van Damme projects; the opening of Knock Off revels in visual effects (microscopic close-ups of the ripping fibers inside running shoes) but doesn’t dwell on what we need to know. Tsui’s task in the collaborative film Triangle was to simply to set up the premises of the action, but dialogue-driven exposition seems to bore him, and the opening scene is a frenzy of eccentric angles and barely registered plot points. His SPFX extravaganza The Legend of Zu has a fairly incomprehensible story to begin with, but by swamping it in explosions and magical transformations, Tsui makes a movie that is, like Spinal Tap’s amplifier knob, permanently set at 11.

With the lack of interest in economical storytelling comes a resistance to emotional engagement. Time and Tide has some virtuoso passages—the tenement sniping, the finale in Kowloon Station (with a woman giving birth during a gun battle)—but the film’s jittery momentum and lack of a coherent point of view sacrifice everything to momentary visceral impact. The death of a little boy caught in the crossfire is not a stab of pathos but the pretext for the visual shock of a ricocheting skateboard.

Tsui’s first films often shied away from sustained romantic scenes, a point made by Sylvia Chang in a catalogue interview. Still, he sometimes translated the awkwardness of love into gesture and motion, from the race to the train at the end of Shanghai Blues to the tender exchange of morsels of food between reconciled husband and wife in The Chinese Feast. Even Once Upon a Time in China can pause for a moment to let Aunt Yee reveal her growing affection for Wong Fei-Hong by having her shadow stroke his.

In the early FW films, emotion was translated into movements large or small. Losing her love makes a woman turn abruptly and snap out her cape, underneath a billboard advertising her lover’s song. But more recently Tsui seems to suffocate emotion in a welter of one-off effects. The lustrous HD shots of Missing make it visually striking, but the lacquered technique doesn’t seem to me to serve the story’s core drama of loss.

We can’t write Tsui off. He’s not yet sixty, and his new project, the Tang era mystery Detective Dee, sounds promising. Whatever happens next, his many admirers thank him and the FW team for some of the most radiant moments in modern cinema. Everyone who has seen Shanghai Blues needs only the stills at the top and bottom of this entry to conjure up the scene: Kenny plays his violin on the rooftop, we hear the soaring tune “Shanghai Nights,” and as we see Sally listening on another balcony, a chill goes up your spine. A little mad, but mostly genius.

Thanks to Alvin Tse for the illustration from the Film Workshop party.

Spring songs

DB here, still in HK:

One director is about as conservative, artistically speaking, as you can get. The other is the long-established wild man of Hong Kong cinema. Both are showcased in retrospectives at this year’s Hong Kong International Film Festival. In a later post, I’ll talk about the outlier; today it’s the Organization Man.

The Hong Kong Film Archive is running a series of works of Evan Yang (Yang Yi Wen). He wrote novels, scripts, song lyrics, and passionate letters to his wife and mistresses, but he’s mostly remembered as a director. Laboring for M. P. & G. I., the Hong Kong studio owned by the Cathay company, Yang established his reputation as a reliable craftsman.

Yang is best remembered for a string of 1950s Mandarin-language movies set in modern Hong Kong; many sequences offer a virtual travelogue of the energetic, sun-drenched colony. Probably Yang’s most famous film is Mambo Girl (1957), starring the effervescent Grace Chang Ge Lan, but local audiences have a fierce sentimental attachment to his two-part historical romance Sun, Moon, and Star (1961). I’ve seen some of these in other thematic retrospectives, but this series is quite thorough. It includes films Yang wrote as well as ones he directed, and it will run through mid-May.

Yang is best remembered for a string of 1950s Mandarin-language movies set in modern Hong Kong; many sequences offer a virtual travelogue of the energetic, sun-drenched colony. Probably Yang’s most famous film is Mambo Girl (1957), starring the effervescent Grace Chang Ge Lan, but local audiences have a fierce sentimental attachment to his two-part historical romance Sun, Moon, and Star (1961). I’ve seen some of these in other thematic retrospectives, but this series is quite thorough. It includes films Yang wrote as well as ones he directed, and it will run through mid-May.

It’s hard to disagree with the severity of the program notes. “His films often suffer from loose structure and sloppy direction. . . Always professional but never a perfectionist. . . . Evan Yang is not a master, nor is he a great film artist. . . .” The impression, not wrongheaded, is of a Hong Kong Charles Walters. But Yang worked hard. In the Archive’s exhibition of his personal papers, you can see his tidy, artisanal dedication. The script pages on display include elaborate notations of shots (ls, cu, diss to…) and markings for repeated setups. It’s evident that Yang took pains to create his smooth, barely noticeable style.

His effort shows on screen. His staging is clean and functional, though he is probably too fond of lining people up in rows. There’s seldom a self-consciously flashy shot or unstable composition. The emphasis is always on straightforward rendering of the melodramatic situations that drive his plots. A doctor falls in love with a patient who’s married (A Little Girl Named Cabbage, 1955). A clerk’s daughter is beautiful but mute, and the family needs money for her operation (The Beauty and the Dumb, 1954). A cat burglar trying to go straight runs afoul of his mercenary wife, who abandons their daughter and then returns to blackmail the family raising her (Blood Will Tell, 1954). Despite the all the adversity, however, things usually turn out well. In Madame Butterfly (1955), Yang updates the opera, making Pinkerton a Hong Kong businessman, and the string of pathetic coincidences swerves into a happy ending.

His effort shows on screen. His staging is clean and functional, though he is probably too fond of lining people up in rows. There’s seldom a self-consciously flashy shot or unstable composition. The emphasis is always on straightforward rendering of the melodramatic situations that drive his plots. A doctor falls in love with a patient who’s married (A Little Girl Named Cabbage, 1955). A clerk’s daughter is beautiful but mute, and the family needs money for her operation (The Beauty and the Dumb, 1954). A cat burglar trying to go straight runs afoul of his mercenary wife, who abandons their daughter and then returns to blackmail the family raising her (Blood Will Tell, 1954). Despite the all the adversity, however, things usually turn out well. In Madame Butterfly (1955), Yang updates the opera, making Pinkerton a Hong Kong businessman, and the string of pathetic coincidences swerves into a happy ending.

The musicals and comedies, although more light-hearted, still bear streaks of melodrama. What I had remembered about Mambo Girl is its fascination with that dance craze, but the plot actually has a serious basis: Grace learns that she’s adopted and sets out to find her birth mother, who turns out to be a nightclub singer. The breezier college romance Spring Song (1959) takes itself not at all seriously, but there is a persistent class antagonism between Grace and her rich rival.

Stylistically, Spring Song shows us Yang in a playful mood. There’s a visual gag during a scene in a coffee shop when our two male leads, Peter Chen Ho and Roy Chiao, wait for their girlfriends. Yang makes them mirror images, even timing the waiters’ arrival to create a funny framing.

Of course when the women arrive and see each other, comic misunderstandings ensue, also played out symmetrically.

Somewhat more subtly, Yang stages the opposition between Grace and Jeanette Lin Tsui during a meeting of classmates by putting the antagonists at extreme ends of a crowded frame.

The archive has produced a handsome book of Yang’s memoirs, in Chinese only, as well as an informative bilingual pamphlet on the retrospective. I hope to sample other items in the series before I leave next week; you know I won’t miss Yang’s take on spaghetti Westerns, Magnificent Gunfighter (1970).

Even if he weren’t such a solid craftsman, I’d respect his films’ sheer documentary value. When Hong Kong movies of the 1950s venture outside their rather creaky interior sets, they often yield up radiant images of a city on the rise. The scene in The Beauty and the Dumb showing Peter Chen Ho crossing the harbor, sitting happily in his sportscar on the Star Ferry, is enough to brighten your evening.

Spring Song, Mambo Girl, Sun, Moon, and Star, and other Yang films are available on DVD and VCD in English-subtitled, not-so-great transfers from Cathay.

Mambo Girl.

Stalking a roast duck

Lai Man-wai and Lai Buk-hoi. Photo from Hong Kong Film Archive Collection.

DB, still in HK:

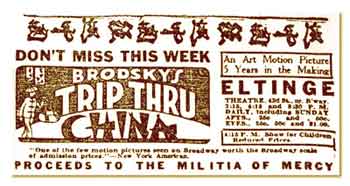

The Hong Kong Film Awards will be celebrating 2009 as the centenary of Chinese film. Why this year? It’s long been said that the first local film was Stealing a Roast Duck, shot by a Chinese director and produced by an American film entrepreneur in 1909. Following received opinion, my book Planet Hong Kong claimed it as the first as well.

Which only illustrates the maxim that history will not repeat itself, but historians will repeat each other. The Hong Kong International Film Festival mounted a panel around several questions. Is it justified to claim 1909 as the start of Hong Kong cinema? Is Stealing a Roast Duck truly the first film? More ominously, did Duck exist at all? What follows are my interpretations of what the panel, moderated by Li Cheuk-to, came up with.

Law Kar, senior historian of Hong Kong cinema, and Frank Bren, an Australian actor/writer, have diligently pursued the Roast Duck question as part of a larger inquiry into the career of Benjamin Brodsky (erroneously called Brasky or Polasky) who later Americanized his surname to Borden. You can read earlier results of their research in their 2004 book Hong Kong Cinema: A Cross-Cultural View. There they review Brodsky’s filmmaking in China and Japan, but they’re cautious about the claims about his 1909 films. Stealing a Roast Duck “has been recorded as the first commercially made ‘Hong Kong film’ by a Chinese director. . . . Unfortunately, due to the non-discovery of any reports about filmmaking in China in any contemporary newspapers from Hong Kong or Shanghai, [Brodsky’s] story remains partly ‘mythic’ . . . .’ (pp. 37, 43).

At Sunday’s panel, Law and Bren reviewed their most recent research. Law noted that Roast Duck enters film historians’ writings quite a bit after the fact. The crucial mention comes in an article in Cinema Almanac of China 1927, published in Shanghai. Even that article did not specify that Roast Duck was filmed in 1909, only that it was one of four films made by Brodsky’s company, which was founded that year. Law went on to trace how later print sources, mostly books and survey articles, elaborated on these points. By 1936, Roast Duck was said to be one of two 1909 films produced by Brodsky in Hong Kong. Later historians recast the claims again, promoting Roast Duck to the status of Hong Kong’s first story film.

The problem is that there appear to be no contemporaneous sources that can resolve the matter. Law, Bren, and other scholars have found no advertisements, announcements, catalogue listings, or other print documents in 1909 mentioning Roast Duck. Moreover, a 1916 interview with Brodsky, conducted by no less a figure than George S. Kaufman, makes no mention of the film. Brodsky mentions The Empress of Dowers (probably The Empress Dowager) and The Unfortunate Boy , two films he made in China, but gives no specific year of production. Since the piece was written to promote Brodsky’s most recent efforts, it would have been in his interest to play up any pioneering role in Chinese cinema he might have had.

Frank Bren’s presentation was a fascinating detective story. Bren has chased Brodsky through the Internet, Social Security records, city directories, and many other data sources. The efforts yielded the outlines of the remarkable story of a Russian-born American who went to Asia in hopes of setting up film businesses there. Brodsky evidently did produce a Hong Kong film, Chuang Tzu Tests His Wife (1913 or 1914), which involved local filmmakers Lai Buk-hoi, Lai Man-wai, and Lo Wing-Cheung. Chuang Tzu is sometimes considered the earliest true Hong Kong fiction film.

Brodsky was also a documentarist, making two feature-length travelogues, A Trip through China (1916) and Beautiful Japan (1917). He died in 1960 in California. Bren continues to research this colorful figure, being especially fascinated by Brodsky’s unpublished autobiography.

The upshot of this research? There is no positive or direct evidence that Stealing a Roast Duck was made in 1909 or was the first Hong Kong film.

Perhaps it was not made at all? Wong Ain-ling, Research Officer at the Hong Kong Film Archive, is not willing to go so far. She is quite convinced of the existence of the film for several reasons. Apart from the references Cinema Almanac of China 1927, she notes an article published in HK in a 1924 New Bijou Theatre Newsletter, often overlooked for some reason or other. The latter reports: “A Russian [Brodsky?] arrived in Hong Kong in 1912 and cast Mr. Leung Siu-po in Stealing a Roast Duck, one of several slapstick films. Shortly after, Lai Man-wai was cast in Chuang Tzu Tests His Wife and The Ghost of the Pot Returns.”

Wong Ain-ling also cited the testimony of veteran filmmaker Moon Kwan, in both his 1976 book Unofficial History of the Chinese Cinema and his oral records with film historian Yu Mo-wan (as recorded in Yu’s Historical Account of HK Cinema, vol 1). Moon Kwan indicated that he watched the Roast Duck alongside Chuang Tzu Tests His Wife in Hollywood in 1917 (or perhaps 1915). In some detail, he recalled the story of the film and the cast, with Leung Siu-po in the role of the thief, Wong Chong-man as the hawker of roast ducks, and Lai Buk-hoi as the policeman.

As for the year of production, Wong finds 1909 quite shaky; 1912 as cited in the New Bijou Theatre article seems a bit closer. That date is also more consistent with the biography of Brodsky. She concluded her remarks by asking whether it is so important to have a celebration or centenary.

I was asked to sit on the panel as well. All I suggested was that there are problems with determining “first films” in any national cinema tradition. There are empirical difficulties—matters of fact, we might say. Most silent films are lost, and paper records are incomplete or destroyed, so it’s quite likely that any country’s earliest productions could be undocumented. Hence we often have to rely on memories, oral history, word of mouth, and collective opinion. Such seems to have been the case with Stealing a Roast Duck.

There are conceptual difficulties about firsts too. What will count as a film? There were many documentaries and newsreel films made in Hong Kong before 1909, some by Hong Kongers. Why are these not candidates for first films? Because, I suggested, we tend to think of “real films” as telling fictional stories by staging the events. Stealing a Roast Duck would fulfill that condition.

The first volume of the Hong Kong Film Archive filmography has taken care to specify what conditions make something a first film in some respect. Chuang Tzu is called Hong Kong’s first “two-reel” film and its first “fiction” film. The Calamity of Money (1924) is described as the first Hong Kong film to be publicly shown in the colony. Rouge (1925) is labeled “Hong Kong’s first feature-length fiction film.” All of these films are, of course, currently lost.

I added that we select firsts on the basis of our assumptions and purposes. We assume that fiction films are more central instances of cinema than newsreels, or that films directed by Hong Kong people are more central instances than those directed by visitors or residents. And sometimes we want to celebrate cinema, so we create a pivotal anniversary: an example is the one hundredth anniversary of cinema (held in 1995, when we could also have done it in 1994). The effort to create a centenary, which in turn generates public interest in Hong Kong film, has settled on a story that suits that purpose.

It’s fun to imagine what a 1909 Stealing a Roast Duck might have been like. A one-reeler, maybe, built around a string of gags. Perhaps the thief makes many efforts to hitch the duck off the rack, before finally succeeding and being chased through the streets of Hong Kong by the cop. The duck becomes a football tossed from one party to another. . . .

More seriously, you have to be impressed with the care with which my fellow panelists exhumed and dissected their evidence. As usual, the closer you look, the more complicated any issue becomes. One of the pleasures of studying film history is that it can surprise us.

An excerpt from Brodsky’s Beautiful Japan is included on volume 1 of the DVD collection Treasures from American Film Archives. A Guardian interview with Law Kar about Stealing a Roast Duck is here. Thanks to Frank Bren for help with access to illustrations.

Law Kar, Wong Ain-ling, Li Cheuk-to, Frank Bren, DB.