Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

Memories are unmade by this

Romance Joe (2011).

DB here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival always provides a host of intriguing experiments with narrative form. This year the Dragons and Tigers series, devoted as usual to new films from Asia, offers such a neat pairing of a veteran director and a newcomer that I can’t resist spending some time on them. Both, it turns out, are interested in memory–not just as a theme, but rather as a process involved in how we watch movies.

Passion for pattern

When we analyze a film, we usually notice patterns—an arc of character development, repeated imagery or musical motifs, recurring framings or lines of dialogue. Filmmakers use these elements of patterning to give elements special significance.

Sometimes the patterns we pick out are noticeable on our first viewing of a movie. Indeed, the film’s effect relies on our seeing later elements as completing a pattern.

Remember “You complete me” from Jerry Maguire? The reason you do, I think, is partly because its first appearance is very salient. It occurs when Jerry and Dorothy are riding in an elevator with a mute couple. Dorothy’s explanation of the couple’s signing highlights it (while characterizing her as a sympathetic person who learned ASL to communicate with a relative). When Jerry restates it in Dorothy’s living room, we recall that it’s a simple declaration of love—a straightforward statement from a man who is habitually slick and evasive. The fact that the phrase stuck in Jerry’s mind from the elevator encounter also offers further proof that he’s not as superficial as he seems. He remembered it, and now we do too.

Sometimes, though, we may find patterns that a viewer may not have noticed on first pass. That’s one of the appeals of doing analysis. As we get to know the film more intimately, we see patterns of coherence that probably many viewers didn’t notice before. In classically made films, for instance, a scene is likely to start with a long shot, proceed to two-shots or over-the-shoulder framings, and then toward tighter close-ups. This stylistic patterning follows the rising drama of the scene’s action. Most viewers probably don’t notice these patterns, but directors, cinematographers, editors, and film students are more likely to catch them. When we analyze a film’s style, we may be surprised to find how often these “hidden” patterns emerge.

Very occasionally a filmmaker gives us something in between obvious patterns and buried ones. A film might repeat something in such a way that (a) you recognize it as a repetition on first pass but (b) you can’t recall exactly what it harks back to. In other words, the filmmaker deliberately organized the movie so that the things that come back are difficult to place in the film as a whole.

The best-known example is perhaps Last Year at Marienbad, where the drifting, dreamlike succession of scenes doesn’t supply standard plot progression. The result is that the images, music, and lines of dialogue are felt as echoes of earlier scenes, but most viewers can’t pinpoint exactly where they first appeared. Another instance would be Buñuel’s Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Here we get scenes that start more or less realistically, and then devolve into absurdity—at which point one of the people in the scene bolts awake in bed. What we’ve just seen is a dream, but we can’t be sure exactly when the dream started because Buñuel and screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière didn’t supply a scene that shows the character going to bed. One effect is that the movie seems like a daisy-chain of overlapping dreams, with no sure point at which we can declare that this or that moment is real.

Both Marienbad and Discreet Charm rely on a fact of cinema: It unrolls in time. So do novels, of course, in the act of reading anyhow. But when you’re reading a book you can stop and page back to check where you went off-track. Since the arrival of videotape viewing, we can in principle do the same thing, and we’d want to replay moments if we’re undertaking an analysis. But the normal conditions of viewing, in both theatres and at consumer command, bias us toward forward momentum. Intent on what happens next, we have a surprisingly hazy recall of what preceded the scene we’re watching now. Halfway through a movie, try to come up with an accurate scene-by-scene list of what you’ve just watched.

The diffuse memory we have of the prior action, and the difficulty of going back to check, is one reason that films need some explicit patterning, their marked repetitions, their constant restatement of the story’s premises. Redundancy of information compensates for the time-bound nature of viewing. Films that don’t supply this, as in my recent example of Sueño y silencio, demand a second viewing—and risk frustrating audiences.

In another country, at other times

Hong Sang-soo has long been a master of the half-hidden pattern. Each film, usually devoted to the comic deflation of male pretension, is built on a unique armature of repetitions. Most critical commentary simply ignores those, trying to summarize the plots straightforwardly and taking the result as comments on contemporary life—an urban milieu in which intellectuals eat, drink too much, smoke endless cigarettes, and make clumsy attempts at romance and sex. “People tell me that I make films about reality,” Hong remarks. “They’re wrong. I make films based on structures that I have thought up.” It’s the structures, I think, that engage us, and partly by asking us to test our memories of what we saw only an hour or less before.

For instance, The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) at first seems a straightforward he-said/ she-said plot. Initally, scenes showing us a love affair’s progress are organized around one character. Then the affair is replayed, but centering on another character. Many scenes show us each character apart, but when they’re together, that scene gets repeated in the second character’s story. The problem is that some significant details are different in the two versions. We’re asked to wonder whether we’re getting the same story as each character remembers it, or two alternative universes in which the stories differ slightly. Moreover, it’s not easy to recall whether this or that prop or line of dialogue was precisely the same in the first presentation. The strain on our memory is part of the film’s fascination.

Hong has been a regular in the Dragons and Tigers sidebar over the years. He’s reliably prolific: two of his best films, both made in 2010, were in that year’s program. This year brought us another Hong brain-teaser and funnybone-tickler, In Another Country. It’s a measure of Hong’s growing international reputation that Isabelle Huppert is recruited to play three roles in another mazelike plot.

Yonju, staying with her mother in a coastal hotel and beset by family problems, tries writing film scripts. In the first, Anne, a French filmmaker, is vacationing with a South Korean director and his pregnant wife. As Anne gets involved with a hunky, good-natured lifeguard, the director is also making a play for her. Cut back to Yonju, trying another draft. In this one, Anne is a rich housewife from Seoul having an affair with a married man—again a director, but played by a different actor. As she waits for him to join her at the hotel, she meets the same lifeguard and romantic complications ensue. Back to Yonju trying another draft. Now Anne is accompanied by another woman, an older professor. They meet the first director, pregnant wife again in tow, while Anne has become preoccupied with getting life advice from a monk. Once more, needless to say, the lifeguard plays a central role.

As you’d expect with a multiple-draft narrative, the changes are accompanied by some constants—an evening barbeque, the lifeguard emerging from the sea, an encounter between him and Anne in his tent. There are even repeated ellipses, bits that are skipped over in each mini-story. For instance, in all three drafts Yonju, acting as hostess, starts to take Anne on a shopping trip and promises to show her something interesting. But then we cut to Anne alone, wandering through town. Why did the women separate? Is this Anne on a different occasion?

Most to the point of memory tricks, we’ll see something in a late scene that may result from something we saw in an earlier draft. When a bottle of liquor breaks on the beach late in the film, you might remember that a previous scene showed the bottle there already broken—but which scene, in what point, in what story? It’s as if Yonju’s different versions have contaminated one another, with scenes from one draft taken for granted in a different version. In the third draft, what Yonju promised was so interesting seems to be the lighthouse. We may forget that in the earlier versions, we never knew why Anne was searching for the lighthouse. Still, we’re unlikely to forget the parallel framings.

This sort of play with our memory can bring the movie to a satisfying, if enigmatic, conclusion. An umbrella, a casual and forgettable prop in one version, provides a kind of minuscule climax in the last. And the final shot of Anne walking into the distance becomes a variant of the film’s first one.

In Another Country provides plenty of social comedy. Hong’s customary satire of Korean males’ awkward sexual aggressiveness is now accompanied by digs at westerners’ search for mystic Asian enlightenment. But the narrative structure is amusing in itself. Hong cajoles us into enjoying the surprising but inevitable recycling of situations, lines, and camera setups. Few filmmakers can make audiences laugh at the mere appearance of a shot and tease us to expect a replay of or departure from what we’ve already seen. Even if we couldn’t say precisely when we saw that image before, we recognize it and participate in a light-hearted game—the game of form.

Wristcutters share their stories

Romance Joe (2011) was made by Lee Kwangkuk, Hong Sangsoo’s assistant director on many projects. No surprise, then, that his debut relies on parallels and variants. Yet it’s much more explicitly about storytelling than In Another Country. Hong uses Yonju’s script drafts as a peg to hang his variations on, but he doesn’t suggest he’s exploring the very nature of narrating. Lee puts fiction-making at the center of his game.

It would be misleading to summarize the plot, since the film aims to put any firm sense of what really happened into question. The core, we might be tempted to say, is the story of a schoolgirl, Cho-hee, who is shunned because she has had sex with an unnamed man. A boy in her class takes pity on her, and when he finds that she has slashed her wrists in a forest glade, he rescues her. They tentatively fall in love and flee to Seoul. On their first night there, he takes fright and returns home. Left alone, she turns to prostitution, and years later, when the boy is now in Seoul in film school, she agrees to participate in a student film he’s crewing. He doesn’t recognize her. More years pass, and the boy is now a film director. He returns to the village, recalls their runaway romance, and in despair attempts suicide. Meanwhile, Cho-hee’s son, whom she has left with her grandparents, comes to the village in search of his mother.

I think it’s fair to say that even this bare-bones anatomy of Romance Joe isn’t fully registered on a first viewing. And in any case, my synopsis is misleading. Why? Because many of these actions are presented as intersecting tales told by two characters who don’t know one another. A Seoul screenwriter recounts the story of the boy’s search for his mother as a purely fictitious one, an idea he has for a script. Alongside that tale, but not precisely inside it, we see Lee, another writer who’s blocked on a story and visits a village to compose a film. There he spends a long night with a tea lady-hooker, Rei-ji, who takes over storytelling duties. Like Scheherazade, she regales him with another story (see our top still). Her tale focuses on the suicidal screenwriter she calls “Romance Joe”–who turns out to be a filmmaker who has gone missing.

So we have one character telling the story of another character who’s hearing a story presented by Rei-ji–a story about yet a third filmmaker, the despairing director, and one that includes his own memories. More confusingly, Rei-ji’s story not only overlaps with the boy’s quest; she becomes a character in the first screenwriter’s imaginary plot. To add to the intricacy, the film employs only partial framing situations, so we might get a scene establishing one tale’s telling, then the embedded tale, and then another situation of telling, as if what we’ve just seen was launched by one storyteller but picked up by another. Instead of a Chinese-box or Russian-doll structure, with one tale neatly enclosed in another, we get something like a cut-and-shuffle mix. And like In Another Country, this film doesn’t wrap things up by a return to the narrating frame; we’re left with something more ambivalent–a question about the very status of the whole assemblage of stories.

It sounds choppy, but it all flows. As one scene slips into another, with abrupt reminders that we’re seeing events told by someone or other, we’re confronted with a cascade like that in Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. We’d be unlikely to recall the precise moment when one story melted into another. Storytelling is linked to rumor and gossip, chiefly by the fact that the trigger for Lee’s initial writer’s block is the suicide of a major actress, supposedly hounded by innuendo. The chief parallel is to Cho-hee, driven to suicide by malicious classmates, but other characters sport the scars of slashed wrists. In this context, the motifs of rumor and suicide tie together the stories conjured up by each of the narrators–again, apparently operating in some predetermined harmony.

Throughout, our uncertainty is increased by some tantalizing misdirections. Might Rei-ji, not Cho-yee, actually be the boy’s mother? Has Lee, after hearing Rei-ji’s story, created the very film we have watched? Finally, the possibility that Rei-ji is no less a fictioneer than the professional writers is broached when she returns to the teahouse and tells the younger hooker that you can make more money through talk than through sex. “Everyone wants a different story. Put some thought into what clients want.” In telling one screenwriter a story about another one, she’s just suiting the service to the customer.

When we study narrative we naturally emphasize the main plot points, the twists and climaxes that claim our attention, the hints that pay off: the gun in the first act that goes off in the last. But films like In Another Country and Romance Joe remind us, as Roland Barthes put it, that “reading is forgetting.” By planting items that will become important later, filmmakers keep us focused on what’s to come and eventually mobilize memory to make all the pieces fit. But filmmakers can also seed their plots with small things that we barely register, then bring them back as half-recalled items. Films like Hong’s and Lee’s are more than puzzle movies; they induce our imaginations to grapple with the limited capacity of our memories. Those limitations in turn affect how we judge characters and the truths of the tales they bear. And in films like theirs, as often in life, our judgments have to remain in tense suspension.

I discuss problems of viewers’ memory in “Cognition and Comprehension: Viewing and Forgetting in Mildred Pierce,” in Poetics of Cinema. I consider Jerry Maguire‘s narrative organization in The Way Hollywood Tells It. For previous VIFF entries that examine complex narration and plot structure, go here and here.

P.S. 5 Oct 2012: Sean Axmaker, with whom we spent many lively hours at VIFF, has posted reviews of several Asian films, including Romance Joe, at Parallax View.

In Another Country (2012).

Around the world in a multiplex: First dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here–

My title exaggerates. There are other venues for the Vancouver International Film Festival besides the Empire Granville multiplex. There is the Pacific Cinematheque, often used for more avant-garde items; the Vancity Theatre, which screens art films and hosts industry events year-round; and the gorgeous old picture palace, the Vogue, a multiple-use venue that hosts both big screenings and gala events. But frequently we find ourselves wandering for a whole day among the Granville’s seven screens, circling the globe cinematically.

The Middle East

Four years ago we blogged about Captain Abu Raed (2007), the first Jordanian feature film in decades. This year there is The Last Friday (2011,  Yahya Alabdallah), and by now the fact of a Jordanian film appearing at festivals is no longer notable. Production has now been systematized. The Last Friday was financed (for around $100,000) by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan’s Educational Feature Film Program.

Yahya Alabdallah), and by now the fact of a Jordanian film appearing at festivals is no longer notable. Production has now been systematized. The Last Friday was financed (for around $100,000) by the Royal Film Commission of Jordan’s Educational Feature Film Program.

The basic plotline is simple, with protagonist Youssef, a handsome, hard-working middle-aged man, divorced and reduced to driving a taxi prone to breakdowns, struggling to earn money for a serious operation. The cinematography was done using a Red One camera, and the resulting images are impressive. (Alabdallah often resorts, with good effect, to what David has termed planimetric compositions, those shot directly toward a flat background.) There is little dialogue, and Youssef’s struggles are conveyed by small details, visual and aural. The fact that he has tampered with his apartment block’s switch boxes to steal electricity is established early on, but by-play with the fuses he has transferred or hidden becomes an unnecessary but entertaining motif.

Perhaps the “educational” part of the film comes from Youssef’s son, a teenage wastrel who hangs out at his father’s apartment. It eventually comes out that he has stopped going to school, and Youssef has the additional burden of confronting his ex-wife to thrash out a method for dealing with their errant son.

The Last Friday treads that risky line so many independent filmmakers on small budgets take, singling out a character with a problem and showing him or her doggedly dealing with it. It takes a sure touch and an interesting character to make this work, and Alabdallah manages both, helped by Ali Suliman’s performance in the lead role.

So far undoubtedly the biggest unexpected gem this year has been the Iranian family melodrama/thriller A Respectable Family (2012). The film is the first fiction feature by documentarist Massoud Bakhshi; it was shown in the Directors’ Fortnight series at Cannes and gained generally favorable reviews.

The plot concerns Arash, a professor who has lived in Paris for decades and, as a guest post at the university in his hometown of Shiraz winds down, seeks in vain for the return of his passport to allow him to return home. At the same time, a lawyer informs him and his mother that a sizable sum of money has been left to them by his estranged, abusive father. The family drama that plays out depends for effect on an extraordinarily complex and tight script with numerous abrupt turns and surprises that keep the audience as busy as in any recent Hollywood thriller. In particular, Bakhshi’s use of switches in point of view and flashbacks to the period of Arash’s youth are masterful.

Here I pass along the same advice I have given friends here at the festival in recommending the film: don’t read reviews or program notes about this film before seeing it. Everything I have read about the film gives away key pieces of information that should be kept secret.

The tone of the film, with its implicit but obvious criticism of the Iran-Iraq war and the regime that fostered it, plus the ending’s evident support for student demonstrators, make it amazing that the film could be made within Iran. It apparently has not been released within its home country and most likely won’t be. Yet the Iranian press reported calmly on its favorable reception at Cannes, as the press there usually does when national films gain prestige abroad. A story in the Teheran Times remarked: “It was a great surprise that non-Iranian filmgoers were able to relate to the Sacred Defense (1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war) and the concept of martyrdom, which are themes of the film, Mohammad Afarideh [the film’s producer] told the Persian service of the Mehr New Agency.” Afarideh added, “The film has an Iranian storyline, but the structure Bakhshi has chosen for the dialogue helps attract foreign audiences as well.”

Many in Iran and elsewhere were also surprised that A Separation could connect with western audiences in the way it did. It’s a pity that A Respectable Family is unlikely to gain such a widespread audience, but it is worth seeking out. It plays once more here in Vancouver, on October 3 at 6:45 pm in the Empire Granville 2.

Latin America

Una noche (2012) is listed in the program as a Cuban/UK/USA co-production. The Cuban contribution comes primarily from the setting and the cast–and the cooperation of the government. (Certainly it makes setting out to try and escape to the USA an unattractive prospect.) It was entirely shot in Havana and environs, and three young first-time actors play the principal roles. The director is Lucy Mulloy, making her feature debut. It is otherwise largely New York based, having been at least partially supported by the Independent Filmmaker project in its “Narrative Independent Filmmaker Lab,” which funds films with budgets of under a million dollars. Post-production seems mainly to have been done at the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU.

Perhaps as a result of such mixed origins, Una noche manages to create a strong, Hollywood-style plot with plenty of local color. The opening shows a blonde tourist in a car, but the heroine’s voice declares that this will not be this girl’s story but her own. Quick but effective characterization sets up the close relationship between twin brother and sister. They’re poor kids from the barrio scratching a living, with Lila working as a dance-hall girl and Elio serving as a cook. Yet we are away from Lila for long stretches, becoming aware, as she is not, that Elio is gay and has a crush a fellow cook. But Raul is an obviously straight young thug, and he has talked Elio into making an attempt to cross to the USA on a raft.

Their preparations, gathering the materials and supplies they need, take us through the poverty-stricken neighborhoods, with Elio’s shiftless friends catcalling at girls and joyriding on their bikes by clinging to buses. Raul visits a dealer to buy medicine for his AIDS-stricken mother, a gaunt former beauty still turning tricks to support herself.

The action escalates as Raul accidentally injures a tourist and Lila discovers that Elio is planning to leave her and go with Raul. Mulloy deliberately downplays the ending, flashing a dedication on the screen to give us the impression that the film is over. Almost as an afterthought mixed in with the beginning of the credits, she presents brief shots showing us of the fates of the characters, filmed from a distance and without Lila’s voiceover. The Variety reviewer found the ending abrupt and “somewhat inadequately foreshadowed,” yet it seemed appropriate to me, and indeed was one of the most original touches in the film.

The North American rights to Una Noche were picked up earlier this year by Sundance Selects after the film proved a hit at the Tribeca Film Festival, winning Best New Narrative Director, Best Cinematography, and Best Actors (shared between its two male leads). Ironically, two of the young lead actors used the Tribeca festival as an occasion to request asylum in the USA.

The Antipodes

There is something comforting about the fact that, after all the success of the Lord of the Rings trilogy and the prospect of a series of Avatar films  being made there into the indefinite future, the New Zealand Film Commission is still funding the same sorts of low-budget genre movies that were made before the country became Middle-earth and Pandora. Robert Sarkies, veteran Kiwi director, has followed up his gripping, headline-based thriller Out of the Blue (20o6) with a return to Scarfies (1999) territory, albeit on a more grotesque level.

being made there into the indefinite future, the New Zealand Film Commission is still funding the same sorts of low-budget genre movies that were made before the country became Middle-earth and Pandora. Robert Sarkies, veteran Kiwi director, has followed up his gripping, headline-based thriller Out of the Blue (20o6) with a return to Scarfies (1999) territory, albeit on a more grotesque level.

Two Little Boys (2012) is based on the old getting-rid-of-an-incriminating-corpse premise, with wimpy Nige (Bret Mackenzie, left) accidentally killing a Scandinavian sports star with his car. Despite a recent quarrel, Deano (Hamish Blake), his best friend from childhood, agrees to help him out and hatches more and more devious and grisly methods for disposing of the body–and later of Nige’s roommate, pudgy, clueless Maori roommate Gav, who adds a touch of sweetness with his persistent obliviousness to the pair’s fiendish doings.

It’s a feather-weight film, but one with many funny moments. It also shows off some parts of New Zealand seldom used in films, starting off in the southernmost and westernmost city, Invercargill, and the bleakly beautiful Catlins, on the southeast coast.

Europe

From the ridiculous to the sublime. Journal de France (2012) presents a sort of professional autobiography of the great French photographer and filmmaker Raymond Depardon. The framing situation is a journey through France that Depardon takes (supposedly alone, though there is someone there to film him), photographing landscapes and villages with his big view camera (bottom). There’s a charmingly chatty scene of him photographing four aged men who had posed for him in the same spot earlier (top).

Interspersed is footage from throughout Depardon’s career. This is presented in voiceover by co-director Claudine Nougaret, the filmmaker’s partner in private life and his long-time sound recordist. Much of this footage didn’t make it into the finished documentaries, including practice shots from when Depardon was learning the trade and amazing footage of many of the major events of the late twentieth century. Depardon travelled widely, often going into war-torn areas of Africa, such as Biafra in the late 1960s. His candid footage of people in the streets of Prague during its invasion by Russian tanks in 1968 is astonishing. Also memorable is a shot of Nelson Mandela quietly sitting in a chair. Depardon asked him to sit for a minute without speaking. Without a watch, Mandela timed it to the second. He learned the trick while in prison.

One comes away with a sense of not just a man with a keen eye and a great deal of patience. Depardon’s bravery and political conscience allowed him to leave behind a legacy of images with an immediacy that brings half-forgotten historical moments to vivid life.

Now I’m off to the Granville again, to see a Japanese film and then a South Korea one. David will blog about these in a future dispatch.

VIFFpix

The big three-oh for VIFF.

DB here:

After several entries (they start here), time for a wrapup.

It was a record-breaking year for the Vancouver International Film Festival: over 150,000 admissions, 386 films, and many awards. Go here for the stats. But linger here for glimpses of friends old and new.

Every night there’s a little, sometimes not so little, reception for filmmakers, guests, the press, et al. in the Hospitality Suite. Sort of like a college mixer, except with better food and everybody talking about movies. On the left we find critic/professor/festival scout Bérénice Reynaud and PoChu AuYeung, VIFF Program Manager and Senior Programmer. On the right, Jack Vermee, Eurocinema expert and Programming Consultant.

More VIFFers at work: Below left, Alan Franey, dynamic Festival Director, with Programming Associate Mark Peranson in the background. With his colleague Jessica Bradford, Justin Mah curates the all-important VIFF videothèque. Below right, Justin (also on the Programming Committee) gets in the holiday mood.

One of the wondrous things about the festival is the access you have to filmmakers. Here’s Kristin with Ann Hui, director of A Simple Life, and Ben Rivers, director of Two Years at Sea.

More fun with filmmakers: Raymond Phatanavirangoon, producer of Headshot, and Charliebebs Gohetia (The Natural Phenomenon of Madness); and Saul Landau (Will the Real Terrorist Please Stand Up?).

Programmers powwow over waffles: Shelly Kraicer, Dragons & Tigers Programmer, and Alissa Simon, Program Consultant for VIFF and Programmer for the Palm Springs Film Festival.

It’s not just for my camera; everybody here grins all the time. On left, Oz festival consultant Geoff Gardner poses with Bruce, while Bruce’s owner Eunhee Cha Brown, Hospitality Suite Manager and all-round organizer, looks on. On right, Tony Rayns, Dragons & Tigers Programmer, reflects on a figure in world film culture who, he reports, “insinuated himself ferretlike into the anus of every major world dictator.”

Other critics get jolly too, not to mention hungry. On the left, Sean Axmaker, proprietor of the excellent Parallax View website (which houses VIFF reports from him and his colleagues Kathleen Murphy and Richard Jameson). On the right, Peter Rist, professor at Montreal’s Concordia University and critic for another fine site, Offscreen. Although my pictures of long-time critical comrade Jim Emerson turned out lousy, you should imagine one embedded here and proceed to his magisterial Scanners site for more VIFF coverage.

Loyal readers of our VIFF missives over the years know that JPG does not stand for Jpeg but rather Japadog. (2009 and 2010 pix here and here). This enterprise is as important as any festival sidebar. Below, a nighttime glimpse of the Japadog wagon conveniently planted outside our hotel. On the right, Professor Jim Udden of Gettysburg College and author of a superlative book on Hou Hsiao-hsien, seated at Japadog Command and Control Center on Robson Street, contemplates the luscious deliciousness that awaits him.

Director Ho Yuhang, critics Chuck Stephens and Robert Koehler, after a JPG feast: From the cut of their strut you know they’re auditioning for Reservoir Japadogs. (Thanks, Chuck.)

Too many more pictures (over 450), lots more to say, many new ideas; but not enough time. (See? Not even time for subjects and verbs.) Suffice it that once more we had a splendid time at this friendly, low-pressure but high-quality festival. You should come next year.

A packed house at The Vogue, a 1941 theatre that had become a music venue in recent years. It was brought into festival service after some years off-duty. Prettier interior shots are here. To see another Granville Street mainstay in its heyday, go here.

More VIFF vitality, fancy and plain

I Wish.

DB here:

Back from Vancouver Internatonal Film Festival, we’re still assimilating. We just learned of the winners, but here are some more movies that won my admiration.

Three lives, four-plus hours

Art cinema has been attracted to mystery and intrigue plots since at least The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. Antonioni needed an enigmatic disappearance to get L’Avventura going. Before and after there were Cronaca di un amore, La Commare Secca, Blow-Up, La Guerre est finie, and the works of Robbe-Grillet. Not to mention Vagabond and Toto les héros and, venturing to Asia, Chungking Express and Fallen Angels.

True to this tradition, in Dreileben (Three Lives, 2011), conventions of festival cinema—elliptical transitions, ambiguous dream sequences, retrospectively identified point-of-view shots, anecdotal realism, de-dramatization, open endings—punctuate, and puncture, a killer-on-the-loose scenario. The genre is respected to the extent of supplying teasing clues, some conveniently recorded on video and in an old photograph. (Shades of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.)

The murder-mystery element is, I think, part of the reason that this TV installment-story has been making the festival rounds. Yes, there’s also its pedigree (three accomplished directors) and its use of the now-common strategy of network narrative. Each of the three episodes focuses on different characters whose paths cross. We get pieces of the whole story; scenes glimpsed in one episode are fleshed out in another.

The tryptych format recalls the Belgian Trilogy (Lucas Belvaux, 2002). But that exercise retold its story by centering on a core of characters, replaying events and switching point of view (and genre) from film to film. Dreileben’s first two episodes focus on characters at some remove from the crime and the criminal, a strategy that redefines what counts as the central situation. Moreover, and unlike most network narratives, these plots show few points of contact. Characters connect very rarely across episodes, so that each tale gains a weight of its own. The mad-killer element comes to seem secondary for quite a while.

The first episode, Beats Being Dead, directed by Christian Petzold, is largely organized around the perspective of Johannes, a young medical student about to embark on a prestigious fellowship. He becomes attached to a moody immigrant woman working in a nearby hotel. Over the romance hovers not only a brutish biker club but also a mental patient, accused of murdering a girl, who escapes from Johannes’ hospital and lurks around the forest. This episode is presented in a clean, almost enameled visual style sharpened by the abrupt scene shifts characteristic of modern cinema.

The second part, Don’t Follow Me Around (Dominik Graf), seemed to me the strongest. Johanna, a female police psychologist, is brought to the town, apparently to profile the criminal, but actually to conduct a rather different investigation. She stays with an old friend and her husband, and Johanna’s visit opens up a new psychodrama all its own. The rather narrow focus of the first, on a romantic triangle, here widens to consider frayed friendships, marital suspicions, and old passions. The character relationships get more complicated as things move along. The somewhat informal framings and jerky cutting (nearly three times as many shots as in the Petzold, in about the same running time) accentuate Johanna’s discomfort and her eventual moments of confronting her past.

After two films hovering around the fringes of the crime, the third installment, One Minute of Darkness, signed by Christoph Hochhausler, seems to go to the heart of things. Now we follow the escaped lunatic Molesch pursued by Markus, a cop so flagrantly unhealthy that he seems to risk a coronary every time he rises from his sagging armchair. Yet this detective story turns out to be not quite as cut-and-dried as we expect. That’s partly because of Molesch’s encounter with a little girl and partly because the first episode is revealed in retrospect to unfold in a more indeterminate time frame than we might have thought. The film doesn’t plug every gap, I think; I left thinking we needed a fourth or fifth installment. But that’s probably part of the point.

Genre conventions permeate all three episodes, which seriatim present twentysomething romance, simmering melodrama, and classic sleuthing and pursuit, all spiced by stalker-in-the-shadows atmospherics. Dennis Lim’s illuminating essay indicates that this trio of films is the product of a German debate about how filmmakers committed to “auteur cinema” can deal with matters of genre.

More broadly, works like Dreileben characterize much of today’s festival moviemaking: an effort to graft modernist narrative strategies onto a genre-driven plot premise. (We see it in The Skin I Live in too.) A cynic could argue that a serial-killer investigation serves to attract audiences who might be put off by purely formal gymnastics. But actually mystery plots, based on hiding information and misdirecting our attention, mesh well with the narrational maneuvers of international art cinema. If crossover films like this bring in more viewers, that’s a side benefit of merging two robust traditions—a storytelling mode that hides and then reveals secrets, and one that believes that even when revealed, secrets remain secretive.

POV = Perplexities of Vision

Headshot.

The barely-converging fates of Dreileben reminded me of the network knitting of Johnnie To’s Life without Principle. In a similar way, two exercises in optical point-of-view echoed the last sequence of Panahi’s This is Not a Film. In that non-film, the camera abandoned by a cameraman seems to be picked up by Panahi himself and carried beyond what we normally think of as “house arrest.” But one of the resources of the POV shot is that it can coax us to ask who’s seeing what we see. If we aren’t given an identifying shot of the looker, we can start to wonder. Played upon in countless horror movies to hint at the eyes of the stalking monster/ killer, the unspecified POV in Panahi’s hands (or perhaps not in his hands) becomes charged with political consequence.

Optical POV isn’t as fully exploited as you might expect in Pan-ek Ratanaruang’s Headshot. One of its premises is that Tul, a contract killer, is wounded in the cranium and as a result sees the world upside down. But the trauma takes place in the first few scenes, and what follows until the midpoint is a set of flashbacks explaining how he became a gun for hire. Present-time episodes showing him getting adjusted to his affliction alternate with past-tense scenes that supply him with motives for revenge.

So far, so noirish. Indeed, the iconography (crooked lawyers, not one but two femmes fatales, chiaroscuro scenes) and the plot (flashbacks, voice-overs, double- and triple-crosses) put us in familiar, quite enjoyable territory. Needless to say, like nearly all film noir heroes Tul has never seen a film noir, so he can’t sense the walls closing in as quickly as we can. He remains idealistic—“I may kill people, but I’m not a crook”—and trusting to a fault.

The upside-down POV works okay as a general pointer to the film’s Buddhist thematics, but the inverted shots are fairly few, introduced to defamiliarize a bit of action. They aren’t exploited as a thoroughgoing formal device. For a while vision scientists believed, mistakenly, that when people wore inverting spectacles, they eventually learned to see the world rightside up. Is Ratanaruang suggesting that Tul adapted in this way?Early in the film the hero pins pictures on his wall upside down, but near the film’s end I thought I saw a shot ostensibly through Tul’s eyes showing us the inverted pictures on the wall, rather than the way they’d look if he saw upside down. In real life, as if it were relevant, it seems that wearing inverted spectacles doesn’t make you see things right way round eventually. The world always looks flipped. But you can adapt to this upside-down array fairly quickly and execute normal activities like riding a bicycle and even reading. Presumably this explains why Tul’s marksmanship remains lethally good in the gunplay finale.

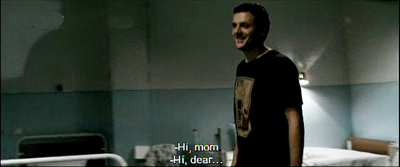

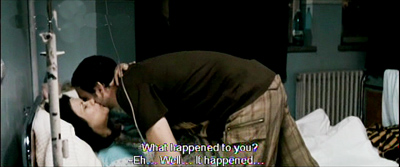

Far more consistent–obsessive, actually–is the play with optical POV in the Romanian film Best Intentions by Adrian Sitaru. When Alex’s mother has a stroke, he leaves Bucharest to visit her. She’s recovering reasonably well, but Alex becomes so anxious about her care that he makes life miserable for her, his father, his girlfriend Lia, and the doctor, an old family friend. After the first scene, when Alex gets the call about her stroke, a drastically totalizing POV system kicks in. Whenever Alex is in the presence of anyone else—major character, minor character, onlooker—we see him through that person’s eyes. If he’s alone, usually on the phone, the shots of him are unassigned and objective, but when he’s in public, he’s only shown subjectively. Moreover, we never get a POV shot from his perspective.

A narrational game emerges. When Alex is interacting with only one other person, we quickly grasp who the Unseen Seer is. For instance, we understand that he’s met at the train by his father, identified by his offscreen voice.

When Alex first visits his mother in the hospital, however, the POV floats momentarily. At first it might seem we’re seeing Alex’s entry through his mother’s eyes,when he briefly acknowledges the camera’s field of view.

But when he moves past, we realize we’re seeing him from the viewpoint of the woman in the bed beside his mother’s.

When he’s with only one other character, the scene plays out without cuts. When cuts come within a scene, they’re motivated as shifts from one character’s POV to another’s. Here we first see Alex and his mother through the eyes of the patient across the room, whom we glimpse in the background during his entrance above. When the mother’s neighbor looks at them, that motivates a closer view of them.

This tag-team POV becomes quite engaging when several characters are present. In a dazzling scene of three couples drinking around a tavern table, the dialogue is fast-moving and the cuts come quickly. I found myself trying to chart exactly whose view we’re getting. Sometimes the POV gets anchored retroactively: one of several characters we see in shot A becomes the POV vessel in shot B. For more fun, the system develops in unexpected ways as the movie proceeds.

The experiment is worthwhile, and not just as a formal game. Recall Erving Goffman’s notion that social life is a stage in which we enact the roles that put us in a good light. Best Intentions shows Alex as not only a caring son but a guy earnestly playing a caring son. In the Theatre of Everyday Life, he’s something of a drama queen. Of course he’s partly right to be concerned about the health-care system (he’s probably seen The Death of Mr. Lazarescu), but that concern also handily motivates his incessant performance of his part.

As a result of Sitaru’s rigorous formal constraints, Alex is onscreen for nearly every instant of this 101-minute movie. (The very brief exception is itself of interest.) His narcissism, his urge to control others, and his inability to really listen to his family and friends—all are perfectly captured by a stylistic strategy that constantly gives him center stage. I haven’t seen Sitaru’s previous film Hooked (2007), but that too used an enveloping POV strategy. Interestingly, there he assigned all three major characters optical POV shots. In Best Intentions, denying Alex his own POV underscores his fretful obliviousness to what anyone else thinks. He makes a scene in every scene, becoming an object of fascination and frustration, for others and for us.

Calming down

All these films, as well as others we’ve discussed in this year’s VIFF, might seem to support the idea that Form Is the New Content. It takes a film like Hirokazu Kore-eda’s I Wish to remind you of the power of less convoluted storytelling. Like Still Walking, it’s a family drama-comedy, but a little more somber and a little more comic. Devastatingly simple, too.

A family has split up. One brother, Koichi, stays with his mother and grandparents in Kagoshima, where the volcano splutters ashes into the air. The younger brother, toothily grinning Ryu, has gone off to Fukuoka with father, a scruffy rock guitarist. The boys communicate by phone, hoping to reunite the family.

They hatch a plan. They’ve convinced themselves that if they make a wish at the precise moment that two bullet trains pass one another, that wish will be granted. So Koichi and Ryu plan a pilgrimage that eventually encompasses their pals and that becomes a confrontation with the mundane realities of death and solitude, mitigated by comradeship and the hospitality of strangers.

The boys’ situation ripples outward to encompass the grandparents’ friends and the sons’ schoolmates and their parents, all of whom earn quietly incisive vignettes. Routines—classroom encounters, swimming sessions, Koichi’s run-ins with teachers, Ryu’s nights out with dad’s band—are recycled without fuss, building up a textured sense of each boy’s world. Kore-eda presents everything so unemphatically that he makes film direction look very easy.

Despite lacking the fanciness of the modern network narrative and its disjunctive time schemes and viewpoint switches, Kore-eda’s plot, like that of Ozu’s Early Summer, effortlessly creates a ramifying world in which our boys feel at once comfortable and apprehensive. Come to think of it, some of the kid comedy recalls the two brothers’ antics of I Was Born But, and the surprisingly sympathetic young teachers, reminiscent of the adults in Ohayo, become co-conspirators and, a little bit, surrogate parents. I Wish is a modest movie; it almost lowers its eyes in front of you. It’s also the closest thing to perfection that I saw in Vancouver.

For a lively roundup of ideas on Dreileben, see David Hudson’s Daily MUBI entry. An informative presskit is here. Headshot has been bought for US release by Kino Lorber. An informative interview with Adrian Sitaru is here. I discuss arthouse genre crossovers in an earlier year’s entry from VIFF. For a more thorough study of network narratives, see “Mutual Friends and Chronologies of Chance” in my Poetics of Cinema.

23 October 2011: Thanks to Christoph Huber for correcting an error in the initial post. Although there is a town called Dreileben, the film doesn’t take place there, as I had said.

I Wish.