Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

Middle-Eastern crowd-pleasers in Vancouver

The Green Wave.

Kristin here:

The Vancouver International Film Festival has offered a rich selection of Iranian and Israeli films this year. I tried to see as many as I could, and most of the screenings were packed.

Iran

The range of Iranian films, made within the country and by émigrés, reflects the paradoxes of that unhappy nation. The glory days of the Iranian cinema of the 1980s and 1990s seem irrecoverable, with leading directors Abbas Kiarostami and Mohsen Makhmalbof and his family working abroad and their younger colleagues, mostly famously Jafar Panahi, being arrested and forbidden to work. Although this national cinema has triumphed at international film festivals, forces in the regime seem determined to squelch the creative people who made that prominence possible. Yet somehow impressive films continue to be made.

Mohammad-Ali Talebi’s Wind & Fog recalls the classic Iranian films of the 1980s and early 1990s, simple stories centered around children’s quests. Talebi himself is a veteran director whose career stretches back to the mid-1980, an era when major filmmakers were skirting the censors by focusing on children and seemingly uncontroversial situations.

Wind & Fog is set in the north of Iran, during the early days of the Iran-Iraq war—a safe enough era, since the loyalty to the government during such a conflict would be unquestionable. The story concerns an eight-year-old boy who becomes mute when his mother is killed during shelling. His father takes him and his older sister to live with their grandfather in the mountains while he works elsewhere. The forested, misty hills are beautifully photographed and contrast sharply with the desert landscapes familiar from other Iranian films. The children form the core of the action as the boy struggles both with his trauma and with bullying at his new school. Both child leads gives wonderfully affecting performances, and the gradual acceptance of the strange young boy by the villagers makes for the sort of happy ending that is rare in the contemporary adult-oriented dramas reaching festivals.

One such film is Goodbye, by Mohammad Rasoulof. Although made within the Iranian industry and presumably passed by the censors, it deals remarkably directly with the efforts of its heroine, a young lawyer named Noora, to leave the country. Initially she plans to depart with her journalist husband. A black-market agency has concocted a scheme to have her become pregnant, be invited abroad to give a paper (arranged by the agency), and give birth abroad; in that way she can avoid returning to Iran.

The film stays entirely with Noora, often filming her in medium-close-up against simple, blank backgrounds. The result is an austere visual scheme of black, gray, and blue-tinged white, with an intense concentration on Noora and her increasing doubts and anxieties. The only moments of everyday life come from a motif of Noora feeding her pet turtle and coping with its tank when it begins to leak. Eventually the turtle escapes, and we never learn its fate, an obvious parallel with Noora’s situation. Possibly the authorities thought this story would be an exposé of illegal agencies fostering emigration, but our sympathies are entirely with Noora and her desire to flee.

I also caught up with A Separation, by Asghar Farhadi. David wrote about this exceptionally fine film from the Hong Kong Film Festival earlier this year. His earlier film, About Elly, is unfortunately not available on English-subtitled DVD but deserves to be released.

Maryam Keshavarz’s Circumstance is often spoken of as an Iranian film, and it gained a higher profile when it won the Audience Award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival. It actually was shot in Beirut and is a US/Iranian/French co-production. Based in part on Keshavarz’s own youth in Iran, it deals with two lesbian teenagers in love and the increasing opposition they face from the brother of one of them—a reformed drug addict who swings to the opposite extreme by becoming an informant for the police. Circumstance has impressive production values and is skillfully shot. I found it a bit sensationalistic, as if the director were flaunting the fact that her film was made far away from the repressive society it depicts. Moreover, its heroines looked more like glamorous models than suffering teenagers. I also wished a more plausible explanation had been given to explain how the brother gained so much power within the police establishment, to the point where he pops up everywhere and seems able to determine the outcome of every situation the reckless girls get themselves into. Indeed, the general stigma attached to homosexuality in Iranian culture is not explored; the girls’ troubles are largely reduced to a family melodrama of conflict between siblings.

The Green Wave is a documentary about the events of May and June, 2009 surrounding the suppression of the brief democratic movement that coalesced around the candidature of Mir-Hossein Mousavi. Made in Germany and directed by Ali Samadi Ahadi, the film stitches together talking-head interviews with activists who have fled Iran, simple animated sequences visualizing accounts culled from blog entries written during the events, and clandestine footage of the demonstrations and brutal crackdown that followed. Much of the clandestine footage was captured on cell phones and other amateur video formats, and the quality is often poor. Still, it provides a valuable record of the police and military firing on and beating peaceful protestors and bystanders in the streets

The film is skillfully laid out, initially conveying the atmosphere of hope that surrounded the campaigning for Mousavi, moving on to show the election itself and how it was rigged to return Ahmadinejad to the presidency, and then focusing on the horrendous crimes committed by the government against its own people. The series of events recalls the hope of the democratic demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in 1988 and the equally brutal attacks on the crowds gathered there. The hopeful attitudes of the crowds in the early days of these events provide a sad contrast with the more recent successful revolutions in Tunisia, Egypt, and Libya, though the Iranian government’s thorough control of its military made a similar outcome impossible. One can only trust that similar documentation of the current events in Syria are being created and will someday be assembled into an effective film like The Green Wave.

A note on This Is Not a Film

DB here:

Jafar Panahi, as you probably know and as this site noted last year, spent several weeks of 2010 in jail for “preparing an anti-government film.” While he was under house arrest in 2011, he made what has been called, for want of a better term, an “effort.” This Is Not a Film is at once funny and disturbing, playful and provocative. It takes its place in the remarkable tradition of Iranian films that oblige us to reflect on cinema–Close-Up, Salaam Cinema, Moment of Innocence, Through the Olive Trees, and Panahi’s own The Mirror. At the same time, this non-film reminds us that artistic matters are tightly intertwined with both political ideologies and the everyday lives that surround their creators.

Panahi and another distinguished director, Muhammad Rasoulof, were arrested while they were making a film in Panahi’s apartment. This Is Not a Film takes place in that space, as if to defy the government’s control over what artists may create in the privacy of their homes. While never letting us forget the political price that Panahi may have to pay—banned from filmmaking for twenty years, sentenced to prison for six—the non-film reflects more broadly on what a film is. At first Panahi seems more or less resigned to his solitude, with his family away and his big-screen TV connecting him to the world outside. He gets a call from his attorney, who suggests that his appeals may shave off some penalties, but “prison is certain.” He ponders this news, but then turns his attention to the real reason he’s recording today.

Panahi explains that he will try to read, with supplementary explanations, the script that he had intended to film. Trying to “create an image of it,” he runs yellow tape across his living-room carpet to mark out a room, a corridor, and a staircase, a skeletal spatial model recalling von Trier’s Dogville. He starts to enact the story of a girl who’s prevented from registering at a university by being locked in her room by her parents. In that reflecting-mirror fashion beloved by Iranian cinema about cinema, we’re invited to see that film, and its reenactment here, as echoing the director’s real-life situation.

The enterprise forces us to ask: Is even this partial, virtual version of an unfilmed film not itself a film? Can you shoot a script by reciting it? Up to a point, Panahi suggests yes. After a couple of tries, though, he falters and seems near tears. “If you could tell a film, then why make the film?” Rerunning a scene from Crimson Gold reminds him that during filming, a project swerves into unexpected territory: a performer’s physical being creates a texture than can’t be captured in language, let alone planned. “A film must be made before you can explain it.” This isn’t just a titillating theoretical aside. It acknowledges the Iranian cinema’s gift for discovering a spontaneous specificity in the most everyday events.

The script-reading-as-film project goes on hold, and mundane household matters intrude. It would be unfair to catalogue all of the anecdotal incidents that invade Panahi’s stronghold. (Yes, as you may have heard, an iguana and a dog named Micky are involved.) The non-film ends with Panahi’s co-director, Mojtaba Mir Tahmaseb, departing and leaving his camera behind. There follows one of those casual, piercing encounters with ordinary people that give Iranian cinema a unique glow. Without warning, the abandoned camera takes on a life of its own, suggesting that house arrest—particularly on the night of a fireworks festival—is as hard to define as a film can be.

An unhappy coda: Documentarist Mojtaba Mir Tahmaseb, the only other individual credited in This Is Not a Film, was one of six Iranian filmmakers arrested on 17 September and imprisoned. A petition on behalf of these people is online here.

Israel

Footnote.

Kristin again:

Judging by the three Israeli fiction films on offer at Vancouver, the country’s cinema is striving toward more straightforward entertainment appeal in some of its productions, though one of the three contains a strongly political subject.

Footnote is that rare comedy set in academia that actually focuses its plot around the main characters’ research. The core conflict is between a father and son, both Talmudic scholars. Eliezer Shkolnik is a stubborn, bitter old man. His lengthy, meticulous study of variant versions of the Talmud was upstaged just before its publication by a colleague, Prof. Grossmann, who made a chance discovery that proved the same conclusions. Eliezer had continued to teach, but his main scholarly claim to fame has been a single footnote in a large introductory study, acknowledging his help.

Eliezer’s son Uriel has become much more famous, based on his many popularizing books that have made him a public intellectual. Early on he is inducted into the Academy. Later, through a mistake, Eliezer receives word that he is to receive the prestigious Israel Prize, but the intended recipient is actually Uriel. Academic politics intervene when Uriel tries to decline the prize in favor of his father: it turns out that the scholar who had beaten Eliezer into print is dead set against him receiving the award. The title takes on a double meaning. In his publication on the Talmudic variants, Grossmann had not acknowledged Eliezer’s work at all, and the missing footnote in that text becomes as significant as the actual one upon which Eliezer has pinned his sense of his own accomplishment.

The film is funny and fast-paced, cleverly using voiceover and PowerPoint-style graphics to lay out the exposition about father and son. It’s apparent why Footnote won the prize for the best screenplay at Cannes. There are many droll touches, including an absurdly small conference room in which Uriel argues with university officials about denying the prize to Eliezer. There’s also a scene where a guard tries to keep Eliezer from re-entering the Israel Museum during the Academy investiture party and he adamantly refuses to provide the information that would gain him access. The whole thing has something of the air of a Coen Brothers film.

Restoration, directed by Joseph Madmony, is a somewhat more conventional family drama, though again with a father-son conflict. The main character, Yaakov Fidelman, is an expert furniture restorer in an age of disposable products. The death of his partner reveals that the business is bankrupt, and Fidelman’s son hopes to sell off the shop’s valuable premises. Fidelman’s young helper discovers that an old, seemingly worthless piano sitting in the shop is a Steinway worth a great deal—if it can be restored. The film is a slick, well-made item. It won the best-screenplay prize at Sundance this year. That surprises me a little, because it depends on an enormous coincidence. The young wastrel hired off the street as Fidelman’s assistant happens to be a promising pianist who abandoned his career path, but who could recognize the value of the old piano.

Policeman (Nadav Lapid) is the one distinctly political film, but in a novel way. It deals not with the usual threats from Palestine and from nearby countries but with masculine identity class tensions inside Israeli society. The first half concentrates on Yaron, a member of an elite anti-terrorist unit, and his bluff, muscular comradeship with his partners. A sudden switch introduces Shira, a member of a cadre of well-off Israeli terrorists determined to invade a lavish wedding and take hostage some of the country’s most wealthy industrialists. Yaron’s squad is brought in to save the situation, and he is stunned when face to face with home-grown terrorists, including a beautiful woman with a gun. It’s a fast-paced film that might do well in the U.S., though so far it apparently doesn’t have distribution there.

P.S. 17 October: Panahi’s appeal has failed and the original sentence of six years in jail and twenty years of forbidden filmmaking has been upheld. Panahi’s attorney plans to appeal to Iran’s Supreme Court. See the Variety story here.

Policeman.

Ponds and performers: two experimental documentaries

Pina 3D.

Kristin here, reporting from Vancouver:

Entertainment and arts journalists seem to have some telepathic way of agreeing upon what will be the big hooks upon which to hang their stories. This year one such hook is the notion that auteurs are finally working in 3D, and this will somehow help determine whether the technique continues to spread. In Hollywood, those auteurs primarily include Spielberg, with The Adventures of Tintin due out in December, and Scorsese with Hugo, the adaptation of a bestseller based on the last years of Georges Méliès.

Two major directors have already brought 3D into film festivals and arthouses. Herzog contributed the one film that even people who dislike 3D (including me) admit uses the technique justifiably: The Cave of Forgotten Dreams. His countryman Wim Wenders’ Pina 3D (Pina–Ein Tanzfilm in 3D) is also a documentary. It creates a portrait of the late Pina Bausch primarily through a collection of scenes where dancers from the current Tanztheater Wuppertal troupe perform excerpts from several of her choreographed pieces.

As usual, the 3D seems superfluous. The opening shot of the theater, with its surrounding stretches of paved surfaces and its rows of trees, looks almost like a model. This is partly due to the almost complete lack of movement. Only some tiny figures on a bench shifted slightly and proved that this was a real space. Within the dance scenes, the 3D effect is more pronounced, but I suspect I would have found the dancing equally dramatic and original had the print been in 2D. One thing I will say for it was that the scenes are bright enough to look good in 3D. The 3D print of Miike Takashi’s Harakiri: Death of a Samurai, which we saw immediately after Pina, displays the notorious loss of light filtered through the glasses. Lowering the glasses a few times during the screening, I got the impression that the print was actually about twice as bright as it was seen through the glasses.

I heard some complaints that Pina offers little information about the choreographer herself. Another objection was that none of the dances are shown complete. Even the lengthiest excerpts, from Bausch’s well-known staging of The Rite of Spring, present only a small portion of the whole ballet. My own reaction was that the variety of shorter scenes gives someone unacquainted with Bausch’s style a good overview of her work.

Rather than go through archival material to present a biographical portrait of Bausch, Wenders chose to highlight each of the members of her troupe with a portrait in medium close-up and a short statement by each about their relationship to the choreographer. I found this helped in keeping track of the performers, who reappear in various combinations throughout the dance scenes, sometimes in solos or pairs, sometimes as a group. Their words about Bausch, though brief, collectively suggest their devotion to her, a devotion that pushed them to collaborate with her in inventing avant-garde moves suited to themselves and yet contributing to a recognizable overall style.

Wenders begins with the dancers on the theater stage, but what differentiates Pina from standard records of dance performances is the filmmaker’s decision to stage some of the short scenes out of doors, in landscapes, city streets, and large empty buildings. One shot looks out over a vast quarry, with a young man bursting up over the edge of it and dancing wildly on the sandy space beside it. Another has a woman performing simple steps on point against the backdrop of a large, rusty factory. A pond in the midst of barren fields forms the stage for a composition juxtaposing a woman carrying a man in the foreground with one carrying a tree at the rear (see above). A few brief scenes have the dancers performing on the corners of busy city streets.

The result gives more an impression of Bausch’s approach to choreography than an overview of her life, but it surely will lure many viewers to seek to learn more about her.

Two Years at Sea

Ben Rivers’ Two Years at Sea neatly straddles the boundary between documentary and experimental film. It appears to be a portrait of an eccentric middle-aged man, Jake, living by himself in a sprawling house in a Scottish forest. The title is never explained, nor is the subject’s name ever given. This film’s natural venues are festivals and perhaps galleries, where notes can supply the information that as a young man Jake spent two years as a sailor, saving up money to live his dream of getting away from urban environments and living close to the land.

Jake makes an excellent subject, almost never glancing at the camera but simply performing his chores, relaxing, or hiking in an unself-conscious way. In the final lengthy shot, he falls asleep on camera. Yet in fact, as we can know only through the program notes or during the filmmaker’s Q&A, Jake plays a somewhat fictionalized version of himself. (The real Jake is more gregarious and welcomes guests.) Rivers suggested some things that his subject might do, and Jake agreed: taking a shower, building a raft from which to fish on a local pond, and mostly notably, raising a small trailer into a pine tree to form a sort of tree house. The framing of the shots showing the trailer rising through the branches hides just how this was accomplished, resulting in a touch of magic realism.

Jake’s home is not a small shack but a rambling building in need of some repair. It is crammed with stuff, empty cans, tools, ancient mattresses, and worn-out objects that the owner can salvage for other uses. Similarly, the yard is overrun by old vehicles, heaps of firewood, and spare parts of unknown machines. Amongst all this apparent junk, Jake has rigged a shower, a stove, an aged washing machine, and a place to sleep. His only company is a cat, although photos glimpsed at intervals—a woman’s face, some children, Jake as a young man building a wall—hint at a past that is never made explicit. Surprisingly, he has a fairly modern car, presumably his means of supplying his needs from an unseen nearby town. He also apparently has a generator, running the lights, washing machine, and a few lamps.

The irony seems to be that Jake has escaped to nature and yet seems almost overwhelmed by the sheer volume of manufactured objects around him. The placement of the trailer atop a tree suggests that now Jake is fleeing the crowded environment he has himself created. Once the trailer is secured, he drags up a small mattress to sit on, cleans the window with his sleeve and, sits contemplating the trees outside.

The techniques with which Jake’s routines are recorded are as Spartan as Jake’s chosen life. Rivers has avoided digital filmmaking, choosing to shoot on black-and-white anamorphic 16mm. He hand-processed the footage at home, creating a grainy, occasionally blotchy image. There are many lengthy takes of actions with slow rhythms. Most is one in which Jake, having built a raft out of a frame covered with an inflated mattress and held afloat by four empty plastic bottles that look like giant marshmallows, launches it, he clumsily paddles a short distance out on the pond, and we watch him fish and drift slowly across the wide screen (see below), ending up near the shore and again paddling further out. He never tells us what he is doing or why, and the filmmaker provides no voiceover. We are left with the impression of a man who does exactly what he wants to do when he wants to do it, whether the practical act of chopping wood or the simple contemplation of something in the landscape because he finds it interesting.

Ultimately, as with any film about someone who has fled to a simpler life, we are lured to contemplate our own occasional fantasies of giving up society’s complex challenges and joys and living somewhere isolated and peaceful. It’s a rare person who would ultimately decide to do so, but here the filmmaker builds a portrait of someone who has.

Two Years at Sea.

PS, October 18: Ben Rivers takes part in a conversation about artists and funding in the UK on Frieze Magazine.

Reasons for cinephile optimism

Hollywood may have largely let us down this year, but after the first few days at the Vancouver International Film Festival, we’ve seen several excellent films and a lot of originality. Here are two of the highlights so far.

Kristin here:

Every year, when festival posts its list of films, I look through it for titles I’d heard about from other festivals or seen enthusiastically reviewed or had recommended to me. One title I was delighted to see on this year’s program was Lech Majewski’s The Mill & the Cross. It’s not nearly as famous as some of the other films showing here, like The Skin I Live In or Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, but I keenly anticipated seeing it.

I learned about The Mill & the Cross through an article in American Cinematographer (posted on the film’s rich website). Majewski collaborated with art historian Michael Francis Gibson to explore Pieter Bruegel’s 1564 masterpiece, “The Way to Calvary.” In the painting, the figure of Christ carrying his cross to calvary is set in the midst of a vast landscape full of fields, cliffs, a distant town, trees, and hundreds of people, all surmounted by a windmill atop one of the rocky formations and silhouetted against a windy, cloudy sky. Majewski sought, as he said, “to enter Bruegel’s world”—to enter into the painting itself and bring it to life.

His goal reminded me of Godard’s 1982 film, Passion, where one of the main characters films actors in a studio. He appears to be trying to replicate classic paintings, with models posed in costumes and miniatures representing a cityscape. I’ve never been able to picture what the result might have looked like. I’m not sure I would have enjoyed watching it, which may be part of Godard’s point. But Majewski had the tremendous advantage of modern computer technology to create an almost seamless blend between digital elements derived from the original painting and those derived from live-action filmmaking on location and in front of blue screens. For those who complain about “effects-heavy” blockbusters, The Mill & and Cross is a powerful counter-example, a film utterly dependent on CGI yet meditative and even profound. It certainly succeeds in Majewski’s goal, creating an uncanny sense of being inside the painting (see above.)

For the film seeks to explore the qualities that Bruegel himself did, to push the crucifixion to a minor place in the composition of the whole and to explore the sacred in the everyday. The film’s story is dense. On one level, we watch Bruegel sketching his models as he explains the concept of the painting to his patron. But we also see him departing home in the morning, and we follow the everyday doings of his family. We see several other minor characters who will figure in the painting waking up and beginning to work, including the miller in his mill atop the cliff. The filmmaking team found a surviving mill of the period, and for an astonishing scene early on, the ancient works in the vast interior were set in motion for the first time in centuries.

We see details of the characters’ lives, such as a man hitching up a horse to a wagon, an innocent-appearing detail until we realize much later in the film that this cart will deliver the wood for making the crosses and will carry the two thieves condemned to die alongside Jesus to Golgotha. Finally, we are invited to contemplate the contradiction, so familiar from thousands of paintings, that an event from antiquity is seen taking place in a contemporary landscape. The result is a comment on the Spanish occupation of Flanders as well as on the Biblical story.

In an all-too-brief scene, Bruegel explains the composition of the painting to his patron, showing how the small group around Jesus forms the center, with the lines between the other main elements around the periphery intersect with it. The implicit comparison is to a charming moment in the film when the painter admires an intricate spiderweb. Apart from all the thematic material, we do learn something about Bruegel’s painting–a point that is emphasized at the end of the film, which tracks back from the actual painting in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, as if inviting us to go and contemplate it in the light of what we have just seen.

Part of what makes The Mill & the Cross so exciting is that it achieves that rarest of things, making us feel that we are seeing something very worthwhile that has never been done before.

The film has a very limited release in the U.S. Anyone who has a chance to see it on the big screen should snatch it. The images, shot on the Red One camera and projected (here, at least) on 35mm, are spectacular.

Once upon a time, and time again

DB here:

Cesare Zavattini, central screenwriter of Italian Neorealism, liked to tell this story. A Hollywood producer once told him:

“This is how we would imagine a scene with an aeroplane. The plane passes by. . . a machine gun fires . . . the plane crashes. And this is how you would imagine it. The plane passes by. . . The plane passes by again… The plane passes by once more…”

He was right. But we have still not gone far enough. It is not enough to make the aeroplane pass by three times; we must make it pass by twenty times.

And, Zavattini seems to suggest, the machine gun should never fire.

Neorealism was one of the most important influences on what we’ve come to call the postwar European “art cinema,” and particularly on filmmakers’ treatment of time. I thought of the Zavattini passage while watching the opening scenes of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once Upon a Time in Anatolia, a film which proves that you can always ring fresh changes on a well-established tradition.

Actually, “opening scenes” isn’t quite right. The very first thing we see, a sort of prologue, presents in two shots the lead-up to a crime. Then come a couple of minutes of credits. Then we get nearly fifty minutes of nighttime shots of police cars driving through the countryside, headlights appearing tiny in the landscape. Again and again the cars halt as the police ask their murder suspect if this is the place where he and his brother buried the body of the man they killed. The suspect says he was drunk and can’t remember exactly. The investigators pick over the area looking for clues before driving on.

But the sequences aren’t quite as spare as I’ve indicated. Scenes inside the car and poking around the areas that might harbor the body pick out two main characters: a brooding doctor and a careful prosecutor overseeing the operation. The secondary cops and assistants are sketched in too. So we have a sort of balancing act between daringly distant “empty” shots and more standard expository scenes. The conversations in the car and in the landscape balance moments that dwell on atmospheric detail. So the relaxed pacing spares time for what will surely be one of the film’s most famous shots, a view of an apple shaken from a tree and bouncing downhill into a stream, where it continues to roll and bob in the dark. It presages the importance of melons, and in the final shots, a yellow soccer ball.

We frequently find that an art film flaunts some arresting narrational devices at the start before taming it as things move along. (Think of 8 ½’s bold opening, initiating us into Guido’s fantasy world, in effect teaching us how to watch the film.) Similarly, Once Upon a Time in Anatolia gets more linear and psychological as it goes along. It shifts from the more unfamiliar uncertainties of the futile stops and explorations to the better-defined questions we expect in a mystery. Is the suspect really guilty, or did his brother commit the murder? What triggered the killing? What effect has the crime had on the dead man’s wife and son?

The gradual shift seems to me to match a certain rigor in Ceylan’s stylistic handling. (Warning: Stylistic spoilers ahead.) In the nighttime search, long shots and extreme long shots dominate—if not by their number, at least by their prominence and vividness.

But having given us plenty of lengthy establishing shots in the first long section, Ceylan denies them in the next two portions.Later in the evening, the search party takes refuge in the house of a village leader and shares a meal with him. Here the action is broken up into close shots, with no long shots (I think) establishing where the characters are sitting. Everything, including the arrival of their host’s beautiful daughter, is given in tight shots of each character.

When the searchers return to town the next morning, they’re greeted by an angry mob. Again, the action isn’t shown fully. Now very long telephoto shots let us glimpse the police and the wife and son of the murdered man, with the crowd visible only as surging, out-of-focus heads and shoulders blocking the foreground.

The last forty minutes or so are centered on the doctor. Attached to him, we watch some interactions that trace out his responses to what he’s witnessed. These are handled in a traditional way, with shot/ reverse-shots, some of them head-on optical point of view, and lingering shots of the doctor brooding.

To the end, Ceylan doesn’t become completely predictable. There’s a nifty bit of elliptical editing during a conversation with the prosecutor. The offscreen sounds of an autopsy, layered by the sound of children’s play, recall passages of shrewdly timed offscreen dialogue that we heard during the long night’s search. And the final few shots play with optical point-of-view in a misleading fashion that has become something of a tradition in the art cinema.

So if the plotting gradually settles down into something less disconcerting, so does the visual style. But that shouldn’t take away from the delicacy and deliberation of a film that gains real gravity through hints and elisions. Above all, certain faces, particularly the despairing one of the prisoner who has a painful secret (surmounting this section), exercise a powerful hold on us. The conclusion of Once Upon a Time in Anatolia pulses with genuine emotion, coolly contained in a mode of cinematic expression that after sixty years or so continues to harbor great power.

The Zavattini passage on flying planes is available here.

PS 9 October: Thanks to Miklós Kiss for correcting an embarrassing spelling error.

Once Upon a Time in Anatolia.

PS October 8: Jim Emerson has also written on The Mill & the Cross, linking to an interview with Majewski on BOMblog.

Vancouver: Final freeze-frames

DB here:

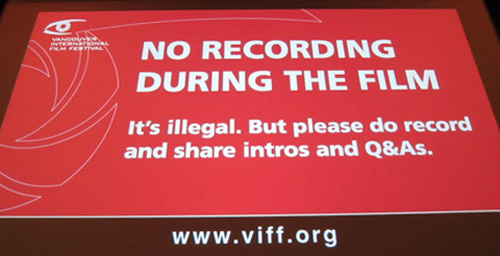

This slide, which appeared briefly before every screening at the Vancouver International Film Festival, epitomizes one of the event’s virtues: quiet sanity. Of course we must discourage people from recording the movie. But just as surely, we want people to photograph the filmmakers and record their comments and get the word out. Spreading the news benefits everybody, particularly the filmmakers.

Indeed, the whole VIFF clambake is run as efficiently as anyone can imagine. Want to get into a film? Very likely you will. A movie is getting buzz? Likely as not, extra screenings will be mounted. Annoyed by mobile devices in the throngs around you? House managers firmly ask people to shut them off. Now. Yet there’s nothing aggressive here. This is a city in which the buses preface the flashing notice “Out of Service” with an apologetic “Sorry.” A Manhattan bus would say, “You’re outta luck, pal.”

Now that Kristin and I are back, we know whom to thank: the organizers, the programmers, the office staff, and the inexhaustibly cheerful volunteers (700 strong). Below are Alan Franey, Festival Director, and PoChu AuYeung, Program Manager and Senior Programmer.

Come down for breakfast and you’re likely to run into Foreign Guest Coordinator Theresa Ho and Hospitality Suite Manager Eunhee Cha Brown. Dreyfus is usually not far away.

Then there’s the multi-talented Lillooet Fox, Food and Beverage Coordinator, waffle wrangler, and music supervisor for Amazon Falls, playing in the festival.

Ever notice how film people are always “on,” always subtly copping stances and looks from movies? Shelly Kraicer, Dragons & Tigers programmer, does his dressed-down version of Lars von Trier.

Speaking of T-shirts, nothing beats telling a story with your thorax. Consider Sean Axmaker (Parallax View) and Robert Koehler (Anaheim International Film Festival) and Raymond Phathanavirangoon (Hong Kong International Film Festival).

At happy hour, the waffles vanish and adult beverages come into their own. VIFF programmer and editor of Cinema Scope Mark Peranson hoists one with Variety critic (and University of Wisconsin alum) Rob Nelson.

Of course everyone mingles with filmmakers. Freddie Wong, director of The Drunkard, is reunited with Bérénice Reynaud, Cal Arts professor and author of a book on City of Sadness.

Tony Rayns, veteran Dragons and Tigers programmer, is flanked by Bong Joon-ho on the left, Denis Côté (Curling) across the table, and Mark Peranson on the right. Geoff Gardner and Jack Vermee are in the distance. Again, the cinephiles pay homage to a shot, in this case from Hong Sangsoo’s Oki’s Movie.

Jim Udden, another Badger and Professor at Gettysburg College (and author of a book on Hou Hsiao-hsien), talks Taiwanese film with director David Verbeek (R U There?).

Trustworthy translator Alex Fu and director Zhu Wen (Thomas Mao).

Takahashi Nazuki and Abe Saori celebrate after their screening of Icarus Under the Sun.

Meanwhile, Geoff Gardner (watch for his VIFF coverage in Urban Cinefile) finds that a rival venue has conjured up a star from another era.

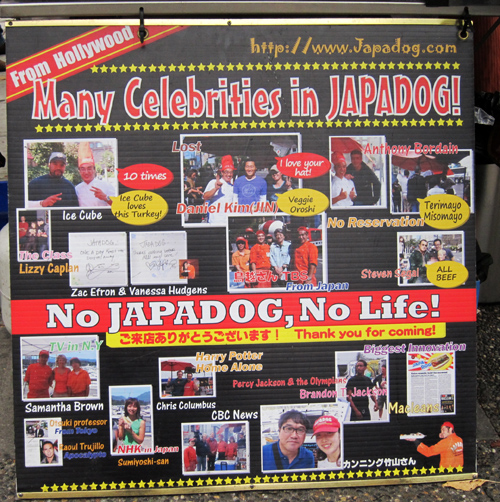

And although we left Vancouver all too soon, we’ll always have Japadog. Not everything in Vancouver is quiet sanity, but even the nuttiness is quite easygoing.

I recommend no. 4, Spicy Cheese Terimayo.