Archive for the 'Festivals: Vancouver' Category

A last celluloid banquet from Vancouver

Detail from “Crimson Autumn” (1931) by Ural Tansykbaev (from The Desert of Forbidden Art)

Kristin here:

A Film Unfinished (Israel; dir. Yael Hersonski, 2010)

A Film Unfinished satisfies on many levels. It is based on several reels of an unfinished Nazi propaganda film labeled “The Ghetto,” discovered among an archive of thousands of cans of Nazi footage. On a simple documentary level, the scenes in the film show precious evidence of life in the Warsaw ghetto in the 1941-42 era, before most of its inhabitants were sent to death camps. As a piece of historical research on the part of the filmmakers, who found written and taped material that shed considerable light on this mysterious footage, it  comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

comes across as a tightly constructed detective story. For theorists of documentary who want to stress that no non-fiction films can reveal life as it is, without manipulation, A Film Unfinished provides a dramatic example.

The samples from the silent footage shown early in A Film Unfinished show a strange combination of subject matter. Apparently candid footage of people in the street, going about their daily lives, is mixed in with scenes of well-dressed men and women in restaurants or elegant apartments. How do these incongruous scenes fit together?

The filmmakers found extensive diaries kept by one of the officials in charge of the Ghetto, as well as taped testimony given in 1961 by one of the main cameramen who recorded the footage. Passages from these, read over additional footage from the film,gradually reveal at least part of the purpose behind the footage. The Nazis apparently wanted to show that some inhabitants of the ghetto were living a normal, even luxurious life (above left). But other scenes were shot showing these same people on sidewalks. Beggars pass by them, but the actors playing the well-off Jews were instructed to ignore them. The result would  presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

presumably have been a display of Jews not only living well but also indifferent to the fates of their less fortunate neighbors.

The filmmaking process frequently intrudes. Apart from the voiceover readings from witnesses to the filming, there are occasional glimpses of cameramen in the backgrounds of scenes (left). Moreover, one reel of the rediscovered film turned out to be unedited takes of several brief sequences, showing retakes of the same footage. Thus an apparently candid shot of two little boys looking into a shop window abundantly stocked with food turns out to have been staged; we even get a glimpse of one of the filmmakers leaning into the shot to direct the boys. A scene of police clearing a crowded street was done by assembling a large group of Jews and then having the police drive people away (the scene at left being part of that action). Urgency was added when the filmmakers fired shots into the air to frighten the crowd.

An added layer was given to A Film Unfinished by assembling a small group of men and women from the ghetto who witnessed many of the events. They are seen watching the film and adding comments. One remembers having seen the filming. Another worries that she will see someone she once knew among the faces on the screen. The presence of these witnesses emphasizes the fact that what we are watching in the rediscovered footage is both an elaborately staged series of events and a grim record of reality in the ghetto. A particularly grim sequence shows men with a handcart gathering corpses from the sidewalks (where helpless relatives, without any other recourse, dumped them overnight). These are taken to a mass grave, where they are stacked like firewood, covered with sheets of paper, and buried. Though the men working at this grisly task were clearly told what to do by the filmmakers, the fact remains that this gathering and disposing of bodies was a routine that went on daily in the late days of the ghetto.

A Film Unfinished would be very useful in a class on documentary cinema.

The Desert of Forbidden Art (Russian/USA/Uzbekistan; dir. Tchavdar Gorgiev and Amanda Pope, 2010)

Our interest in 1920s and 1930s Soviet avant-garde art led David and me to this film. It reveals the remarkable, unknown work of Igor Savitsky, a Russian Russian archaeologist who discovered the culture and art of the Karakalpakstan region of Uzbekistan. Applying for government funds to create the Karakalpak Museum of Arts, Savitsky initially stocked it with the jewelry, costumes, pottery, and other local cultural artifacts that were discouraged by the Soviet modernization policy.

He also discovered that there were many hidden paintings and drawings by artists whose avant-garde tendencies had gotten them into trouble with the central Soviet government in the Stalinist era. In 1966 he secretly–and very illegally–began using government money to buy up whole caches of these works. By the time of his death in 1984, he had acquired around 44,000 of them! Many are still in storage, awaiting restoration, but the galleries of this remote museum are full of extraordinary, hitherto unknown artworks.

The Desert of Forbidden Art is informative not only about the history of Savitsky and the museum, but it reveals something of the current culture of this isolated province, a culture which figures prominently in the artworks as well. Sons and daughters of the artists appear on camera, as does Marinika Babanarzorova, the museum’s current director. Naturally many beautiful artworks are on display as well.

The film touches only briefly on the fact that these artworks have been hidden away in a remote desert area which is also increasingly under the sway of Islamic extremism. A few documentary shots show the dynamiting of ancient rock-cut Buddha statues in adjacent Afghanistan in 2001. The head of the Nukus Museum was invited to appear with the film at the VIFF, but she was unable to get permission to leave the country. One is left wondering whether these artworks will need to be rescued anew.

The film is screening widely at film festivals and societies, mostly in the USA but in a few other countries as well. See its website for a schedule of upcoming showings. It also will be run in April or May, 2011 in the PBS series “Independent Lens.”

Certified Copy (France/Italy/Belgium; dir. Abbas Kiarostami, 2010)

This was the film I was most looking forward to at the festival, and it was the last–and best–one I saw. As usual, Kiarostami has come up with a novel approach to storytelling. (See David’s entry on Shirin.) After only one viewing, I’m not confident enough to say much about Certified Copy. Besides, almost anything I say about the plot will give away too much. This is a puzzle film that unfolds very slowly and very subtly.

It seems to work in ways almost opposite to those of the big puzzle film of the year, Inception. That film was almost all exposition, which we had to frantically note and try to piece together to get even a rough grasp of the plot. Certified Copy has almost no exposition–or none that we can recognize immediately or even trust when we do recognize it. I could gauge how slowly that recognition comes by the fact that the laughter at apparently incongruous behavior between the characters gradually faded. Different members of the audience realized at different moments that what had seemed incongruous maybe wasn’t after all, though it’s possible that the incongruity was just increasing right up to the end. Close to the end, only a lady two rows behind me was still laughing.

Essentially what happens is that a plot unfolds, and despite a lack of solid information, most of us probably infer from the conversations enough to assume we understand the two main characters and their relationship. Eventually their actions suggest that perhaps an entirely different plot and relationship has been unfolding all along. (This comes fairly late in the film, in maybe the last third or even quarter.) Perhaps the information we receive does not allow us to decide in this ambiguous situation, though I think people do tend to decide. I decided one way, David decided the other.

Interestingly, this mirrors in longer form the last sequence of Under the Olive Trees. There we are not told what the girl replies when the boy runs after her and proposes marriage one last time. In that case, too, I decided one way, David the other. Years ago we told Kiarostami this, and he laughed and said men tend to assume the girl accepts him, while women assume she rejected him. (I think there actually are some fairly clear clues earlier in the film that she will reject him, but explaining those would be a different entry.) That may be the case here, that men and women will reach opposite conclusions.

On the other hand, and this would require at least a second viewing, the film may remain utterly ambiguous about which plot is “real.” Or it may even stray into the territory of the inexplicable, à la Buñuel or David Lynch, where the difference parts of the story are each “true” but incompatible. M. Tsai suggests, “‘Certified Copy’ plays out a bit like a romantic comedy directed by David Lynch with its distinct two-halves connected by a thread.” (Not to be read until you’ve seen the film.)

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

Apart from its teasing, baffling, shifting elements, Certified Copy contains two fine lead performances and, of course, some beautiful cinematography. There’s a bit of a surprise, in that Kiarostami for the most part avoids his characteristic sweeping views of landscapes. Tuscan hilltop towns would seem to be perfect for his typical shots of vehicles struggling up bending roads, but we are largely confined inside the car during the driving scene, watching the characters and not the glimpses of trees through the windows. Those yearning to see Italy must be content with stone or painted stucco walls (as at the left).

For many links to articles and reviews, see David Hudson’s helpful wrap-up on Mubi. (Again, not until you’ve seen the film.)

Sodankylä Forever (Finland; dir. Peter von Bagh, 2010)

DB here:

Do writers write books about fanatical readers? Do composers write operas about opera lovers? Sometimes, but not to the degree that cinephiles delight in making films about their passion. Case in point: Peter von Bagh’s Sodankylä Forever. The Festival screened two films devoted to Finland’s Midnight Film Festival, which not only runs movies around the clock but hosts marathon interviews with filmmakers.

It isn’t your usual red-carpet event. The town is tiny. Guests are treated to campfire cookouts and invited to play soccer. But watching old clips, catching snatches of the Johnny Guitar theme, and hearing revered directors spin their yarns is enough to bring pleasure. There are moments of drama—Zanussi and Makavejev boycott a screening of Potemkin because of its “totalitarian” ideology—but mostly the filmmakers muse in a relaxed fashion about the good, and bad, old days.

The Yearning for the First Cinema Experience treats a core cinephile topic: What was your earliest encounter with the movies? Disney films, as you might expect, play a major role, but so too does Frankenstein (which made Victor Erice realize that people kill other people) and even the MGM lion (which startled Kiarostami in his childhood). The First Experience includes more mature epiphanies, such as Bob Rafelson’s obsessive visits to Manhattan’s Thalia. If the official classics get particular attention, it’s perhaps because, as Costa-Gavras says, “Everything was done in the silent cinema.”

So cinephiles are nostalgists, sentimentalists, even narcissists. But we aren’t oblivious to history behind the screen. The Century of Cinema episode focuses on directors’ relation to World War II (a continuing fascination of von Bagh’s). An era of purges, battlefront savagery, and prison camps, created, Szabo reflects, “a generation without fathers.” Jancsó, who served time in a Finnish POW camp, pays tribute to his hosts with a recitation, in Hungarian, of the opening of the Kalevala.

After the war, however, several Western European directors recall the advent of a new era of intelligence and creative engagement. The spirit was most apparent in the Italian Neorealist films. Erice tells of sneaking a forbidden print of Rome, Open City out of customs so that Spanish cinephiles could see it. In Eastern Europe, of course, things were different, and tales of censorship and young directors’ struggle to innovate are treated as continuations of wartime crises and constraints. Alexei German sums up the status of the artist who refuses to affirm official culture: “We are not the doctors, we are the pain.” Samuel Fuller, who has already explained that being assigned to a rear-guard unit in a retreat is a death warrant, is given the epilogue. He recalls visiting the tidiest graveyard he has ever seen and turning to watch the wind rustling the grass. Was he imagining how the scene would look on film? Naturally, arch-cinephile von Bagh shows us.

DB, Abbas Kiarostami, KT. Chicago, March 1998.

Seduced by structure

Mysteries of Lisbon.

DB here:

If you’re hungry to learn about the ways films can tell stories, a festival provides a feast. A huge array of narrative strategies is spread out for your delectation. You won’t like every movie you see, but thinking about the mechanics of each one can deepen your experience of it, as well as your appreciation for just how wide cinema’s resources can be. You also get to see how more unusual approaches to storytelling are often imaginative revisions of more traditional strategies.

We can usefully think about narrative from three angles. We can study the story world that a film conjures up: the characters, places, and actions we encounter. We can analyze plot structure, the distinct parts that are put together sequentially. They might be scenes or sequences or larger-scale parts, like the Hollywood screenwriters’ “acts.” We can also analyze narration, the patterned, moment-by-moment process of presenting the story world and the plot structure. Think of a narrative as like a building. The building’s furnishings correspond to the story world, and the architectural design of the building, plan and elevation, is like plot structure. Our real-time pathway through the building, from the front doorway into its depths, corresponds to narration.

The Vancouver International Film Festival that Kristin and I have been visiting offers a banquet of storytelling devices—some quite traditional, some fairly fresh. I’ll just survey some aspects of structure that I found intriguing.

The longest distance between points

The Chinese blockbuster Aftershock, centering on the 1976 earthquake that struck Tangshan, has earned some complaints about weepiness and jokes about “Afterschlock.” Perhaps melodrama makes many critics uncomfortable. They seem more at home with comedy and noirish crime stories, perhaps because the emotions stirred by these are bracketed by a degree of intellectual distance. But tell a story about a happy family split apart by a catastrophe; show a mother forced to choose between saving her son and saving her daughter; show that the girl miraculously escapes death; present her raised by a pair of new parents; and dwell on the fact that her mother, living elsewhere, expects never to see her again—do all this, and you court mockery.

Well, mockery from everybody except the hundreds of thousands of people who have always enjoyed these situations. Aftershock is now the biggest box-office success in Chinese film history (presumably using today’s currency standards). Whatever the film owes to Chinese traditions, it is easily understandable in a Western context. Stories based on pseudo-orphans, separated siblings, and parents forced to give up children have long been sure-fire. Les Deux orphelines, an 1874 play, is one strong prototype. This pathetic tale of two sisters torn apart in post-revolutionary Paris was adapted by many directors, including Griffith (Orphans of the Storm, 1921). Feuillade developed similar motifs in Les Deux gamines (1921), L’Orpheline (1921), and Parisette (1922). A mother’s loss of her children through accident or social oppression is another stock situation, seen in sublime form in Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff. The obligation to pick a child to save is at the core of Sophie’s Choice, a more highbrow melodrama. Likewise, the discovery of unexpected kinship forms the climax of many stories, from Oedipus Rex to Twelfth Night and beyond.

You may call these conventions hackneyed, but it would be better to call them tried and true—proven effective by centuries of deployment, counting on emotions aroused by ties of love and blood. Such situations would be good candidates for narrative universals, which can be reshaped by local cultural pressures.

The premise of a fragmented family bears chiefly on the story world. The filmmaker still must choose how to structure the plot. For Aftershock, director Feng Xiaogang and his collaborators settled on the time-honored route: parallel stories across the years, shown by means of crosscutting. After the quake, scenes of the mother and son alternate with scenes showing the girl’s rescue and her life with her adopted parents, both soldiers in the People’s Liberation Army. For about the first sixty minutes, the segments are rather long, but after that shorter scenes from each plot line are intercut. The son moves off to a separate life, but his success as an entrepreneur is given short shrift. The plot concentrates on the daughter’s college career, her sometimes stormy relation with her foster parents, and her unexpected pregnancy. In the meantime, the mother survives, turning aside a kindly suitor in order to preserve her faithfulness to the husband who saved her life.

Narrationally, the alternation between the separated characters gives us superior knowledge. We know, as the mother and brother do not, that the daughter survives; we also know that she nurses a bitter memory of hearing her mother choose the rescue of her brother. Likewise, we know that the mother has tormented herself for decades over her forced choice. Thus the recriminations that will burst out after they rediscover one another will require some healing, which is provided in the plot’s last phase. Melodrama depends on mistakes, and they must be corrected. In a telling image of two sets of schoolbooks (not previously shown to us), we and the daughter realize that over the years the mother has been thinking of her as if she were still alive.

The dual structure can also tease us with suspense. At the hour mark, we learn that both the brother and the daughter are in Hangzhou, without each other’s knowledge. The brother even encounters the foster father. It’s the sort of coincidence that leads us to expect a reunion. Coincidences, I mentioned in an earlier entry, are fascinating narrative devices, and here the fortuitous convergence doesn’t actually pay off. But it does prepare us for the genuine reunion that will take place an hour or so later, when an earthquake hits Sichuan in 2008.

There’s a lot more to be said about Aftershock; I was struck by the fact that the children are left in the collapsing apartment because the parents have sneaked off to have sex in the husband’s truck. (So is the whole arc of suffering the punishment for a little carnality?) But just sticking with structure, we find that a cluster of ancient plot devices, fed into the established technique of crosscutting, can still find purchase in a contemporary film. In films like Aftershock, as in Hollywood’s romantic comedies and horror films and historical adventures, very old narrative conventions live on. Suitably spruced up with CGI, they still provide pleasure.

Sometimes, however, you get the sense that filmmakers in other cultures are borrowing conventions of recent Western films. This seems the case in City of Life from the United Arab Emirates. Faisal is a spoiled playboy who spends his nights with his pal Khalfan, a fistfight-prone club-hopper. Natalia is a Romanian flight attendant who gets romantically involved with an advertising man. Basu is a taxidriver with an uncanny resemblance to a Bollywood star, and so he tries to supplement his earnings by appearing in a nightclub. As all of them move through Dubai, their lives intertwine.

We have, in short, what I’ve called a network narrative. Mostly the plot lines are juxtaposed through crosscutting, but sometimes the characters in one line of action encounter those in another. Faisal is at a club on the same night as Natalia is there, with her boyfriend and her roommate. Objects circulate as well. Natalia pays Basu for a cab ride, and Basu preserves her €20 note until he has hit rock bottom. At the midpoint, an ad campaign links Natalia’s boyfriend, Faisal’s father, and Basu’s job. Many of the conventions of the “small world” network format are included, with one character remarking that Dubai is a small city. Our old friend the traffic accident (shot and cut with exceptional vividness) plays a crucial role. A refuse collector threads through the plot, turning up at unexpected times and providing an ironic coda.

Director Ali F. Mostafa mobilizes a lot of contemporary techniques, including fast motion and rapid cutting (3.6 seconds average shot length). The editing sometimes extends the crosscutting principle by flipping back and forth between two successive scenes, creating little flashforwards. For instance, when the adman Guy phones Natalia to introduce himself, we cut to them talking in a bar and then back to her listening to his sweet talk.

The anticipatory cuts lead us to expect that Guy is calling to ask her out, and Natalia will accept. This sort of cross-stitching can be found in The Godfather and other films of the late 1960s and early 1970s, and it has shown up sporadically since, but it’s rare enough to still look modern.

In cinema, network narratives can occasionally be found before the 1990s, but they’ve become far more common. I count nearly 150 films of the last twenty years employing the structure. In literature, of course, such plots go back quite far, and they formed the basis of nineteenth-century novels by the likes of Balzac, Dickens, Zola, and George Eliot. Television soap operas and ensemble series like Hill Street Blues showed that modern media’s long-form formats fit well with network storytelling. So cinema has caught up, adjusting the template to feature-length plots. City of Life shows that artists from emerging filmmaking nations can use this structure to enter a festival circuit dominated by Western norms of construction. At the same time, those artists can tailor this structure to their own ends—in this case, it seems to me, presenting Dubai as a city of emigrants ruled by a feckless leisure class.

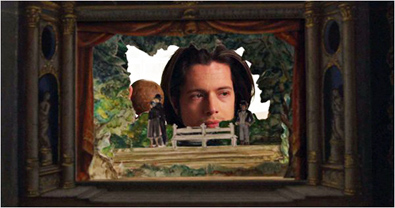

The theatre of memory

What happens, though, when conventions of sprawling nineteenth-century novels aren’t squeezed so drastically into the usual feature length? I had a chance to find out from Vancouver’s screening of Raul Ruiz’s four-and-a-half-hour Mysteries of Lisbon. Based on an 1854 novel by Camilo Castelo Branco, a fictioneer as prolific as Ruiz himself, the film doesn’t trim off the exfoliating plot lines that we enjoy in three-deckers from the period. This being a Ruiz film, there is as well a tangible pleasure in the artifice of storytelling. The film acknowledges that all the handy coincidences, buried pasts, multiple identities, and revelations of kinship are there for our delectation.

Orphans again: João is being raised in a church school, but he has no idea of his parentage. Early on, kindly Father Dimis tells him that his mother is Angela, the countess of Santa Barbara, but her brutal husband is not his father. We are soon embarked on the extended flashback that traces the doomed love affair that results in the birth of the young hero, now named Pedro. In the course of that tale, we meet two more suspicious characters, the gypsy Salino Cabra and the hired assassin Heliodoros.

This recounted history is only the first of a cascade of flashbacks, issuing from several characters, and these gradually show deep connections among persons tied to Pedro’s past. Secondary characters in one story become protagonists of another. The young hero is gradually displaced as the center of the action by war, secret romances, rivalries, duels, and infidelities. Like Pasolini in his Trilogy of Life, Ruiz is happiest when opening up a plot detour that will eventually become a new main road.

By the end, our young hero has become something of a nullity, an empty center around which aristocratic ecstasies and follies have swirled. He’s something like the Dubai of City of Hope: a point of intersection of many fates. He’s also a passive observer of scale-model dramas played out on his toy theatre stage. His voice-over narration has enwrapped the whole film, and our last glimpse of him is as merely a narrator. Pedro seems finally to realize that his entire existence has served simply to gather other people in a tangle of doomed passions.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Mysteries of Lisbon has a rich, high-thread-count look, but it’s not your usual prestige costume drama. The long takes cling to characters as they flirt their way across a ballroom, and the camera slips through walls in the manner of old-fashioned cinema. There are the usual Ruiz flourishes of hallucinatory deep focus (achieved through split-focus diopters), characters floating rather than walking, and the occasional peculiar angle. But the film remains calm and lustrous, culminating in a slow tread into pure light.

Ruiz’s appetite for narrative is almost gluttonous; he supposedly wrote over a hundred plays in six years, and he’s made about as many films. He once told me that he thought that Postmodernism was simply a revival of the Baroque in modern dress. From Mysteries of Lisbon, it’s clear that he sees in many older narrative traditions affinities with our tastes today. Network narratives? They’ve been done, and maybe better, centuries ago. Follow the lacy tendrils of classic family-origins plots, and you’ll find a pattern as intricate as anything in Short Cuts or Pulp Fiction. More story ahead: there’s a six-hour television version.

Rumination on ruination

Ruiz understands that modernist narrative techniques, including unreliable narrators and fancy time-switches, depend upon a long tradition in at least two ways. First, very often the tradition got there first; scholars like Meir Sternberg and Robert Alter have demonstrated complex plays with chronology and point of view in the Bible and the Greek classics. Secondly, unusual plot structures may ring unexpected variations on more conventional ones. Case in point: reversed plot sequence.

Again, this seems to be something of a modern trend. The locus classicus appears to be Harold Pinter’s 1978 play Betrayal, in which, scene by scene, the plot proceeds in reverse chronology. This was filmed in 1983 and gave birth to a famous Seinfeld episode. As you know, Memento, Irreversible, and other recent films have taken up reverse-chronology plotting. Actually, however, there are several earlier instances, notably the 1934 Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (turned into a musical by Stephen Sondheim) and W. R. Burnett’s 1934 novel, Goodbye to the Past. Other examples, some going back quite far, are listed here.

Rumination, a film by Xu Ruotao in the Dragons & Tigers young directors competition at Vancouver, turns the structure to political ends. Reduced to the bare bones, the film shows a teacher, his wife, and their son caught up in the Chinese Cultural Revolution. The father falls in with a gang of Red Guard youths rampaging through the countryside. The son trails the gang at a distance and occasionally interferes with their acts of violence. These story events are arranged in blocks, with each cluster of scenes associated with a specific year. The blocks proceed backward in time, from 1976 to 1966. After a prologue, the film shows scenes of the waning of the Revolution; before the epilogue, we get a stalwart young man announcing the Revolution’s birth.

The scenes are fairly episodic and independent, so I didn’t detect the backwards structure for quite a while. But my uncertainty had another source. Xu introduces each year’s scenes with a date that is, except for one instance, not the year of the actions shown. In fact, while the segments move in reverse order, the years’ designations move in chronological order.

The opening 1976 section is labeled 1966, the 1975 section is labeled 1967, and so on up to the end, with the 1966 action designated as 1976. So we see the father’s reunion with his wife, a moment of clumsy embrace, long before he decides to leave home. As you’d expect, there’s one year in which the action and the tag coincide, 1971, and that is the only one built out of photos and film clips from the period. The year is privileged, Xu explains, because that was the year of the mysterious plane-crash death of Lin Biao, a military hero and Cultural Revolution leader who was accused of plotting Mao’s assassination.

In my viewing, the misleading dates helped conceal the reverse chronology. Confronted with so many discrete episodes of unidentified characters sprinting through the countryside, beating passersby and stealing chickens, I took the default option and assumed that the segments were chronological. Moreover, the film’s scenes play out almost entirely in overcast landscapes and decrepit factories, a landscape in which I couldn’t detect any indications of change from year to year. Watching Ruination a second time, I saw the reversal more clearly, but I also thought that some segments tease us into thinking along chronological lines. An early scene shows the father getting up in the morning (a conventional way to start a plot), saluting Chairman Mao’s statue, and reading from the Little Red Book. Yet this scene is set in 1975, after the father has returned to his wife from his Red Guard period.

Moreover, there’s some evidence that the son actually matures across the film, even though the scenes show him objectively getting younger. By the end of the plot (the earliest moment in story time) he seems to have transformed himself into a strapping young Red Guard. Supporting this construal is the fact that in the Q & A after the showing, Xu mentioned that one influence on his film’s design was The Curious Case of Benjamin Button!

Xu explained that the tragedy of the Cultural Revolution could not be comprehended through normal storytelling techniques. I suspect that viewers familiar with the relevant events and the film’s slogans, iconography, and oblique citations (even to Godard) could follow the backwards sequencing. But I suspect that those viewers would need a sense of the historical chronology to grasp the 3-2-1 order of the plot. It seems to me that Xu, known until now as a painter, has shown how an innovative approach to plot structure relies on conventional responses even as it thwarts them.

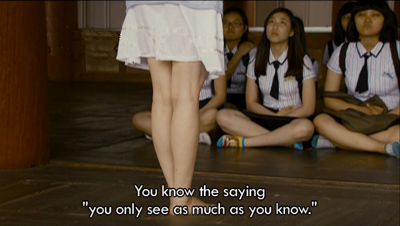

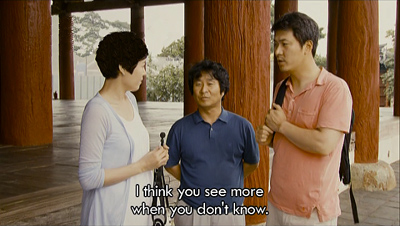

Hahaha indeed

Hong Sangsoo has been one of the leading experimenters with narrative in today’s Asian cinema. My two favorites, The Power of Kangwon Province (1998) and The Virgin Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors (2000) have engaged the viewer in playful puzzlement about how story lines can collide or slip sideways, how our memory of earlier scenes’ action can be tested and found faulty. I haven’t been deeply engaged by his recent forays into more straightforward drama/comedy, such as The Woman on the Beach (2006), but his two latest features, both from this year and both on display in Vancouver, completely satisfied my hunger for intriguing plot structures.

It’s an unspoken convention of recounted-flashback tales that even though the events are told by A, B learns everything that we do—everything, that is, that we can see or hear in the flashback. But Hahaha decouples the verbal recounting from the visual presentation. Here listener B definitely does not grasp what we witness happening onscreen in the tale as told.

Hahaha is a parallel-protagonist tale. Two pals meet for some drinking before one, Munkyung, leaves South Korea for Canada. Through a series of flashbacks, they regale each other with their recent adventures, mostly amorous. The plot is structured as two alternating streams, crosscutting one man’s tale with the other’s and usually returning to the framing situation of their drinking bout. But because we can see what each one recounts, we come to realize that both stories are populated by the same people, notably the tempting female tour guide Seongok. And those people have their own relationships, which we must piece together out of the glimpses we get in each man’s tale.

Neither Munkyung nor his pal Jungshik has a clue that they are part of a fairly tight circle. The result, as usual with Hong, is a comedy of ironic misunderstanding and the puncturing of male pretension. Hahaha can also be seen as his response to the rise of network narratives. Characters in such a film don’t usually realize the larger mosaic they’re part of; the intersecting lives in City of Life transform one another unwittingly. Normally that lack of awareness isn’t the main point of the film. Here it is, and it’s wrung for classic humor at the protagonists’ expense.

In Oki’s Movie, Hong gives us another fractured plot, but now in the form of four short films. They center on three characters: Song, a film director turned professor; his student Jingu; and Oki, the woman both men are interested in. The raggedy credits of each short suggest handmade movies, but what we see in each one is the polished style familiar from Hong himself, including his current interest in abrupt zooms.

The four-part structure is far from transparent. It might be taken as a series of episodes from the trio’s lives. The first film, “Specters of the New World,” which presents Jingu as a professor himself, would have to take place in the present, and the following three would then be presenting flashbacks to the Jingu-Oki-Song triangle. In that case, the first segment would prove that Jingu did not wind up with Oki, as he’s married to another woman.

Perhaps, though, all four films are free hypothetical variations on the central situation. I’m not sure that we can easily arrange the events in the second, third, and fourth episodes chronologically. The films could be presenting successive groups of events, or events scattered across a single time span and then selectively gathered around one of the central characters. The first episode is largely organized around Jingu’s range of knowledge; the second is confined to professor Song; and the third is explicitly presented as Oki’s own thoughts. Earlier Hong films have offered us contrasting, even incompatible plots built out of a core group of characters. Oki’s Movie may be using the framing conceit of student films (none of which is plausible as a student film) to give us a suite of variants on the love triangle.

The idea of ambiguous variation is made explicit in the final mini-film, “Oki’s Movie.” It’s a sustained exercise in—yes, again—crosscutting. This episode alternates two excursions to Mount Acha, one with each man. Shot by shot, we see different courtship styles and we hear her differing reactions to her two lovers. Was she dating both men at once? When did the two excursions take place? Which one occurred first? As these questions are juggled, we get a rapid checklist of Oki’s attitudes, in voice-over, toward both these minor-key losers.

In both Hahaha and Oki’s Movie, Hong takes what’s offered by tradition—in this case, the romantic comedy and the conventions of flashbacks, crosscutting, and restricted narration—and creates a fresh structure. The play of novelty and norm is engrossing in itself, apart from the vagaries of the drama. Our appetite for narrative will always be whetted when directors find ways to whip up something new out of familiar ingredients.

For more on the three dimensions of film narrative, as well as discussion of the principles of network construction, see my Poetics of Cinema. There’s more discussion of flashbacks in film in this entry. On early narrative structure, see Meir Sternberg’s Poetics of Biblical Narrative and Robert Alter’s Art of Biblical Narrative, as well as Sternberg’s discussion of The Odyssey in Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction. For a sharp-eyed consideration of Oki’s Movie, see Andrew Tracy’s review at Cinema Scope.

Oki’s Movie.

Another dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here:

Surviving Life (Czech Republic; dir. Jan Švankmajer, 2010)

I became a fan of Švankmajer’s work back in 1988, when I saw Alice, his first feature. David and I gradually explored his shorts and discovered that some of them were among the great classics of the animation form, perhaps most notably Jabberwocky and Dimensions of Dialogue. Švankmajer mostly concentrated on object animation, often combining found objects like tools, stuffed animals, dentures, and food in bizarre ways to create figures.

But after Alice, Švankmajer continued to make features, and they contained less and less of what he was best at: animation. Faust was all right, but I suffered through Conspirators of Pleasure and skipped Lunacy altogether. The director has claimed that Surviving Life is to be his final film, so I thought I owed him a last chance. It’s lucky I did, since it’s a real comeback for him, and a return to what he does best.

Whether Švankmajer really wanted to eschew live-action filmmaking and take up animation again is a moot point. He appears in a prologue, not exactly as himself but as a pixillated cut-out photographic figure (apart from the same typical cut-ins to real speaking mouths that became rather tedious in Alice). He describes how he intended to make a live-action feature, but with a small budget could only afford cut-out animation. He demonstrates by hopping about the frame like a figure in a child’s TV show. At the end, he checks how much time the prologue has taken up–two and a half minutes–and mutters that it’s not very long. His mordantly amusing speech doesn’t suggest whether he really had tried to make the film with live action. Indeed, the actors who are represented by the cut-out photographs obviously had to act out their movements, in costume, and to provide their voices. How much cheaper all this could be is debatable.

The story is about dreams, and specifically about a man stuck in a dull desk job who dreams of an exotic woman in red. His doctor sends him to a psychiatrist whose office contains photos of Freud and Jung, each of whom listens and reacts with applause or contempt when his own or his rival’s theory is employed. The hero is horrified when he discovers that the psychiatrist is trying to rid him of his dreams when his own desire is to live within them.

We tend not to think of cut-out animation when we think of Švankmajer, but predictably he proves a master of it. At times the technique resembles that of Terry Gilliam in the animated interludes of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, especially in scenes shot in a black-and-white cityscape with surrealist objects emerging from the windows (see above and below). The “actors” appear as smoothly animated photographs except for close shots, when the actual actors are shown. The technique works brilliantly, with the cuts between the image and the real person being smoother than most Hollywood matches on action.

If Švankmajer has chosen this as his swan song, he has gone out reminding us why we admired him in the first place.

The White Meadows (Iran; dir. Mohammad Rasoulof, 2009)

There are probably a lot of indirect comments on the political situation in Iran in films from that country. Some are obvious to all, others no doubt only to people who live that situation every day. Few, however, can be so overtly allegorical as The White Meadows. Oddly, the allegorical implications are so clear that they can be grasped immediately and do not impinge on the intriguing strangeness of the tale being told.

The central figure is a man who rows his small boat across a highly saline sea, stopping at islands and coastal villages in deserts caked with salt formations. (Yes, another Iranian journey film.) At each stop he gathers the tears of the local people, gradually accumulating a small bottleful. Each stop also yields a fable-like incident that reflects the plight of certain sectors of Iran’s population: a beautiful virgin is sent as a sacrifice to a sea god, an unconventional artist who refuses to paint naturalistically is tormented and sent into exile, and so on. The overall impression is of universal suffering, and the ending suggests that this suffering benefits only the rich and privileged.

The white and tan landscapes and pale blue sky and sea provide stunning locales for this simple tale, shot around Lake Urmia in northeastern Iran.

While watching The White Meadows, one wonders how Rasoulof could get away with such an overt criticism of religious and governmental repression in Iran. He couldn’t, quite. He was arrested alongside Jafar Panahi (who edited The White Meadows) and about a dozen others on March 2. Fortunately he was released fairly soon, on March 17. What his future as a director in Iran is remains to be seen. The government has long tolerated having one set of films for local popular consumption and another that will be confined largely to the international festival circuit. Not surprising, since these days Iran’s filmmaking is one of the few areas in which the country is seen internationally in a positive light. Still, such a bitter yet appealing film clearly stretches such tolerance.

Every year it seems more and more likely that the increasingly tenuous new Iranian cinema will finally be snuffed out, and every year–so far–we see bold and imaginative films coming from that country. We can only hope that with the arrests earlier this year, we are not seeing the long-expected end.

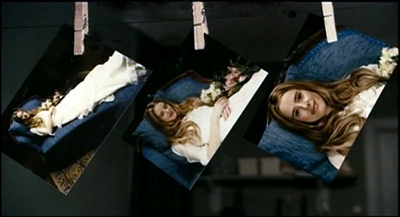

The Strange Case of Angelica (Portugal/Spain/France/Brazil; dir. Manoel de Oliveira, 2010)

The fact that Oliveira was 101 when he made this film, as well as the fact that he is still directing at least a film a year (for last year’s Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, see here), is too extraordinary not to be remarked on. Yet we shouldn’t let it dominate our view of Angelica or tempt us to treat it as an old man’s film. Slowly paced and meditative it may be, but it is also imaginative and full of humor, despite being centered around a young man’s obsessive love for a dead woman.

The protagonist, Isaac, is a photographer living in a boarding house in a town in the Duoro Valley region of Portugal. (Oliveira’s first film was a beautiful city symphony, Douro, Faina Fluvial, a poetic study of the river in the same valley made in 1931.) Called upon to photograph a beautiful woman who has died shortly after her wedding, through his viewfinder he sees the corpse open her eyes and smile at him. The same thing happens when he gazes at photos of her hung up to dry:

He falls in love with her, and her ghostly figure visits him at night, wafting him up into the air and flying over the river with him. Although he wakes from dreams several times, we are left in doubt as to whether Angelica really has been appearing to him.

The film seems to be set in contemporary times, and yet it has an old-fashioned look t it. The protagonist photographs men at work with hoes in a nearby vineyard, though his landlady remarks that no one does manual labor anymore. But most obviously, the film has the look and feel of a silent film. The shots of Angelica and the hero flying are superimposed ghostly figures straight out of Edwin S. Porter’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906). Camera movements are used sparingly, as in many silent films. Scenes often consist mostly of the hero taking his photographs or thinking of his phantom love, and his occasional cries of “Angelica!” could be rendered as intertitles. The use of solo piano music by Chopin reinforces the sense of watching a “silent” film.

(1906). Camera movements are used sparingly, as in many silent films. Scenes often consist mostly of the hero taking his photographs or thinking of his phantom love, and his occasional cries of “Angelica!” could be rendered as intertitles. The use of solo piano music by Chopin reinforces the sense of watching a “silent” film.

Yet there are occasional scenes of dialogue. The best scene in the film may be the one where over the breakfast table the other boarders discuss their concerns about Isaac’s state of mind. The scene ends amusingly with the camera holding on the landlady’s bird jumping around its cage, watched with great attention by her cat.

Oliveira will turn 102 on December 11. He is listed on Wikipedia has being in pre-production for A Missa do Galo.

Kawasaki Rose (Czech Republic; dir. Jan Hrebejk, 2009)

(Note: Many reviews and the VIFF program give the title as Kawasaki’s Rose, but the title on the film is as given above.)

This film creeps up on you. At first it seems poised to be yet another study of a failed relationship among upper-middle-class characters. A documentary is to be made about Pavel Josek, a noted professor famous for his past resistance to the Communists. The sound-man on the shoot is his son-in-law Ludek. His daughter Lucie has been told that a large tumor just removed is benign. Ludek confronts her with the fact that he has been cheating on her during her illness, and he undermines her efforts at disciplining their daughter.

But this conventional soap-opera material gradually opens out as files discovered during research for the documentary seem to reveal that Josek had in fact cooperated with the Communist regime, apparently including his participating in the torture of prisoners. From that point, Ludek recedes into the background and further political and personal revelations give the film considerable depth and complexity.

Kawasaki Rose was beautifully shot in full anamorphic widescreen, with images around the harbor in Göteborg, Sweden being particularly well composed.

While I was watching the film, I was reminded equally of Wajda’s Man of Marble and von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others. On the one hand, a film project that digs into the past of a heroic figure who turns out to be not quite so heroic, and on the other a study of the effects of interrogations into private lives under a totalitarian regime.

Kawasaki Rose (the title derives from an origami pattern and is given to a Japanese character in the film who paints flowers) is the Czech Republic’s entry for a foreign-film Oscar nomination. I wouldn’t be surprised if it gets one.

The Dragons & Tigers’ late-night roar

Thomas Mao.

DB here:

First, the news flash: Tonight was the awards ceremony for the Dragons & Tigers competition for young filmmakers here at Vancouver. A jury doesn’t get more distinguished: it consisted of (left to right) Jia Zhang-ke, Denis Côté, and Bong Joon-ho.

They awarded two special mentions, one to Phan Dang Di’s Don’t Be Afraid, Bi! (from Vietnam) and to Xu Ruotang’s Rumination (China). On the last-named, check the still at the end of this entry.

The grand prize went to the Japanese film Good Morning to the World!, by Hirohara Satoru.

More details here. Congratulations to the winners!

Beginners’ luck

My Film and My Story.

Vancouver is unusually hospitable to shorts and features by newcomers. Two of this year’s D & T offerings illustrate how talent, unlike youth, is not wasted on the young.

A cinémathèque featuring classic films is about to reopen, and the manager has hired some twentysomethings to help her get things into shape. The result a network narrative: romantic rivalries, coming-of-sexual-age crises, the race to set up the screening space, and even a ghost story are woven together as the big day approaches. The film is split into eight chapters, each given an emblematic movie title. Two petty thieves interview for a job under the aegis of “Stranger than Paradise,” and an apparent love triangle is christened “Jules and Jim.” The cinephilia shapes the plots too, as when one boy gets the courage to kiss another after watching Happy Together.

My Film and My Story was a group project of students at the Art and Design School of Konkuk University in Seoul. Their professor proposed that each student write a script about the opening of the cinematheque, and the results were integrated into a single feature-length story. There were seven student directors, one per episode; a producer contributed an extra chapter. Most directors were on the set all the time, making suggestions and trying to fit bits together. (“We fought a lot.”) The remarkable visual consistency—smooth cutting, tight framing, and well-modulated lighting—came from the single director of photography. As the title suggests, some of the tales are based on incidents in the lives of its makers.

The film, presented in Vancouver by two of the directors, Hong Youjin and Kim Taeho, is a lively charmer, with plenty of comedy and pathos. The characters are quickly introduced, and there are nice touches of movie-nut satire. One girl with big spectacles saves all her ticket stubs, takes notes on every movie (I can identify), and is annoyed when a boy drapes his leg over the seat in front of him. The episodes make tactful use of digital techniques, particularly in one shot that fuses past and present through the classic color/ black-and-white disparity.

My Film and My Story wasn’t in the official young-film competition, but Icarus Under the Sun was. For once the ragged style of handheld video justifies itself in a tale of a girl who quits school and heads for Tokyo to work in a seedy mahjong parlor. Haruo rooms with a flighty roommate and her boyfriend, but becomes more attached to the workers in the parlor and the owner, a nearly blind, taciturn man for whom she conceives an almost daughterly affection.

The plot barely rises above anecdote, but it’s continually engaging through its focus on the performance of Abe Saori, one of the two directors. Haruo explains that she is “addicted to walking,” and some of the best scenes involve conversations during late-night wanderings in the bitter cold.

Starting out fairly choppy, the narration accumulates weight and breadth as Haruo becomes engaged in her work. The shots throughout are held rather long, but about halfway through, the scenes start to be built out of exceptionally long takes. When another worker, the boy Aran, takes sick, Haruo calls on him and we get an almost suspenseful treatment of her arrival in his apartment, with him lying almost motionless in a heap in the foreground.

The shot lasts almost four minutes as she comes forward to talk with him. Their subsequent conversation is filmed in a tight, leisurely shot as they eat burgers and explain their backgrounds—virtually the only exposition we get about Haruo’s troubled past.

The dingy look of many scenes carries a documentary conviction that a more polished work would not. And the rough texture is actually the product of patient care. Abe and her codirector Takahashi Nazuki explained that they spent ten months in shooting and two to three months in editing. But it’s no mere technical exercise either, since Abe calls it both a fictional film and a documentary about her experiences. Like her protagonist she spurned conventional schooling and went to Tokyo to live on her own. Rooming with Takahashi, she decided to make the film “to know certain shadows” in her life. Icarus Under the Sun is actually the duo’s second film, and they have already finished a third, the more technically slick Soft-Boiled Egg (Hanjuku tamago.). Another thing about young directors: They have energy.

Expecting

Takashi Miike’s 13 Assassins is not what you might expect. Unlike your typical Miike item, this one throws no curves. It is an old-fashioned, butt-stomping, gut-slashing swordplay movie, with swagger to spare. Adapted from a 1963 film, it’s Seven Samurai plus six, with explosives.

True, there’s a Miike signature moment early on that shows what Lord Noritsugu has done to a woman’s body in his quest for piquant entertainment. But this horrifying scene serves a very traditional purpose: To prove to swordmaster Shinzaemon Shimada (and us) that Noritsugu has failed his duty as a leader and must be assassinated. He isn’t merely brutal. He lives an aesthetic of exquisite savagery. He has turned droit de seigneur into performance art. A massacre, he says with a fetching smile, is fun. He is a handsome monster. We can hardly wait to watch him die—preferably like a dog, in the mud, in agony.

Thereafter all that we want from a chambara flows forth in abundance. Unsurprisingly, the plot is framed by the man-out-of-time motif. Noritsugu’s depraved tastes show that the samurai tradition and the Shogunate government have become decadent. This might be a warrior’s last chance to die nobly—but for what? What deserves a man’s loyalty? Hard times have convinced Shinzaemon that the samurai class must ultimately serve the people. But his old rival Hanbei, Noritsugu’s right-hand man, clings to the notion that the samurai serves his master, unswervingly. Hanbei goes to his death committed to traditional duty. But his commitment is proved unworthy when his lord has a little fun with his severed head.

Miike faced a choice. He could have provided each warrior a vivid backstory, differentiating and humanizing each one as Kurosawa did. Instead, given a two-hour running time, he concentrates on strategy: How can a baker’s dozen of fighters defeat Noritsugu’s troops, which will eventually swell to 200? The solution is to maneuver Noritsugu’s men into a village filled with traps that will give the assassins some advantages—surprise, rooftop ambushes, and a deployment of livestock as ordnance. Things are enlivened by a feral hunter, mocking the samurai code while wielding a mean slingshot. After supplying a sketch of each of the thirteen assassins, Miike spends his energy on action. The muddy, gory battle at the climax lasts forty-plus minutes, and is worth every penny of your admission. Magnet, the genre arm of Magnolia, has picked up 13 Assassins for early 2011 release, and you should start thanking them already.

If Miike surprises by doing something normal, Zhu Wen’s Thomas Mao really does keep you guessing. It’s a pleasure to see a movie in which you can’t imagine what will come next.

At first, things seem to go by the numbers. To a remote Chinese farm comes the artist Thomas, to stay a short while and do some drawing. His wizened host Mao provides bed (after the geese are shooed out) and board (mostly corn on the cob). The trouble is that Thomas speaks no Chinese and Mao speaks no English. Every interchange is a pas de deux of misunderstanding. Thomas generously gives Mao some money. Mao refuses—not, as Thomas thinks, because he’s too proud but because Mao considers the amount insultingly small.

So we seem to have the small-scale cross-cultural comedy, making amusing points about people’s petty differences. Then the ghosts arrive.

At least, they might be ghosts. A phantom swordsman and swordswoman float around Mao’s farm and do battle, ultimately slashing off each other’s arms before disappearing, never to return.

There are aliens too, invading Mao’s cabin with pop-concert glow sticks. They’re totally unexpected, like the warriors, and their visit is even more transitory.

Eventually Thomas leaves, and the film starts over. The second part offers a sort of crazy-mirror image of what we’ve seen so far. Artist becomes model, model becomes artist, dog becomes Doggy. If you like the double-track story of Syndromes and a Century, you’ll probably like Thomas Mao, which is less rigorous but more funny. (The very title is part of the joke.) Zhu, who has reveled in comic byplay in Seafood and South of the Clouds, gives us that rare thing, a movie that is whimsical without being precious. You learn about contemporary Chinese painting in the bargain.

More whimsy, also not overbearing: When Liu Jiayin told me last spring that she was making a movie about a plastic fish, I didn’t know what to expect. The answer comes in the short film 607. Here the ballet of family hands seen in Liu’s Oxhide II becomes more playful. 607 is part of a promotional series of shorts by independent filmmakers, and it’s sponsored by a Beijing hotel, The Opposite House.

Mr. Fish, wielded by Liu’s father, swims around the tub, occasionally flirting with a mushroom provided by her mother. Eventually Mr. Fish is tempted by a hook (the curled finger of Liu herself). Will he fall for it? In all, you have to admire the coordination of three people shifting smoothly offscreen around the tub, each person’s hands sliding out of one part of the frame and popping in somewhere else—somewhere, I need hardly say, fairly unexpected.

PS 9 October: This entry has been corrected from its initial appearance. There I had written that Liu Jiayin’s 607 is one of three films she is making for the series commissioned by The Opposite House. Actually, the entire series consists of three films made by independent filmmakers. 607 is one of those and is complete in itself. Thanks to Shelly Kraicer for the correction.

Rumination.